1. Introduction

Reproductive-age women experience a high risk and incidence of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and its deleterious complications [

1]. It is an admixture of health complications that impact women’s physical and emotional well-being during the late luteal phase of their menstrual cycle and gradually subside with the beginning of menstruation [

2]. Substantial variations in the incidence and prevalence of PMS were reported across the globe, possibly due to differences in diagnostic approaches, including instrumentation [

1]. A systematic review revealed that about 47.8% of women were affected with PMS and the prevalence ranges from 12% in France to 98% in Iran [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) diagnostic parameters were observed and met in 3-8% of reproductive-age women with PMS [

5]. The PMS symptoms include irritability and anger that gradually aggravate and worsen six days before the initiation of the menstrual cycle [

6]. The predominant clinical manifestations of PMS include breast tenderness, abdominal bloating, social withdrawal, depression, and anxiety [

7]. The etiology of PMS is based on disturbances in the secretion and function of neurotransmitters, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin [

8,

9]. The contemporary literature provides evidence substantiating the adverse impact of PMS manifestations on the daily living activities of reproductive-age women. For instance, at least one in three women with PMS were unable to independently manage their daily living activities in the absence of caretaker support [

10]. In addition, data suggests the negative influence of PMS symptoms on the academic performance of university-level female students [

11]. Data further indicate a strong correlation between psychiatric comorbidities and PMS manifestations; these comorbid conditions majorly include somatoform disorder, anxiety, and depression [

12]. Interestingly, PMS complicates the period of puerperium and adds to the risk and incidence of depression [

13]. Such association advocates that these two conditions share similar feature of vulnerability to changes in female gonadal hormones [12, 13].

Robust evidence supports the use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as a first-line treatment of PMS [

14]. Data suggests that SSRIs are effective whether used during the luteal phase or continuously [

14]. However, side effects are frequent, with nausea and asthenia being the most commonly described [

14]. Several patient-reported surveys have revealed the non-pharmacological treatment preferences of PMS-affected women, compared to medication-based management [

15]. Despite the notion of a positive health influence of dietary approaches on PMS symptoms, the current evidence does not suffice for its inclusion in treatment prescriptions, in the absence of pharmacological therapy [

16]. Importantly, findings from a recent study revealed an increased rate of negative affect and impaired performance with the higher consumption of carbohydrates [

17]. Contrarily, evidence also indicates a statistically insignificant association between PMS symptom severity and consumption of a carbohydrate-rich diet [

18]. Few studies have demonstrated a significant change in the food consumption patterns of females before menstruation and their high risk of PMS due to the higher intake of salts, saturated fat, carbohydrates, and sugar [

19,

20]. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advised women with PMS to consume frequent small portions of complex carbohydrates and reduce the intake of sugar and salt to help with reducing symptoms of PMS, such recommendation was based on limited evidence [

21]. Based on the contemporary evidence, this study hypothesizes the possible beneficial role of a healthy, balanced diet in managing the clinical manifestations and overall health and wellness of patients with PMS. This study aimed to investigate the role of face-to-face dietary recommendation and the motivational follow-up protocol in minimizing the symptoms and improving the health-related quality of life in adolescent females with PMS.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a prospective, open label, randomized controlled trial of two parallel groups. It was conducted in two randomly selected secondary schools in Al Seeb Willayah, in Muscat region. The consecutive sampling approach was used to recruit the study participants. The candidates who qualified for the initial eligibility criteria were interviewed by the principal and co-principal investigators. Subjects who had one symptom or more of PMS in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition DSM5 [

22], were advised to fill in the daily record of severity of problems questionnaire (DRSP). As recommended by the DSM5, women were instructed to fill in the DRSP for two consecutive months [

22]. Then, those who fitted the criteria of PMS were invited to participate in our study. The study was started on 1 February 2021 and ended on 30 June 2021. The trial is registered with the WHO/Iranian

Registry of Clinical Trials # IRCT20201129049526N1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adolescents who were at grade 10 or 11, aged 16 years or above and had regular menstrual cycles were included in this study. Exclusion criteria included those who were known to have psychiatric disorder (such as depression, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychotic disorders), diabetes, and thyroid disease. In addition, those with a history of oral contraceptive use, and those who were previously administered with or adhered to dietary recommendations for PMS management or those who utilized herbal remedies were further excluded. Adolescents with a confirmed diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) were also excluded and referred to the nearest local healthcare centre for urgent management by a well-trained family physician.

Sample size

The sample size for the primary outcome was calculated based on difference in mean DRSP scores for a two-group parallel clinical trial with equal allocation. The acceptable effect at which superiority could be declared if there were a decrease in the summary DRSP score of six on the DRSP tool in the intervention group compared to the control group was used. The true difference is thought to be seven and the conservative estimate of expected standard deviation in the population in which the trial is considered to be 1.5 resulting in effect at the size of 0.67. For a power of 80% and α of 5%, the required sample size in each group is 28 subjects. Anticipating a dropout of 25%, the expected sample size is 35 PMS subjects in each group. nMaster software was used for calculating the sample size [

23].

Recruitment and randomization

Consecutive sampling was used for the recruitment stage. Cluster randomization of schools was carried to minimize contamination anticipated from recruiting subjects from the same school. Notably, the study was conducted in two randomly selected secondary schools in Al Seeb Wilayat in Muscat region. The participants in the intervention group (school A) and those in the control group (school B) were recruited from two separate schools, which were located in different areas and were maintained at an adequate distance from each other within Al Seeb Wilayat.

Treatment protocol

Participants in the intervention group received an individual face-to-face dietary consultation by a well-experienced dietician, who educated the participants about the importance of healthy diet, evaluated the baseline dietary habits of each participant and gave advice on how to modify them. The food-based dietary guidelines (FBDs), customized for Omani adolescents, were used to generate the healthy balanced diet recommendations for the participants [

24]. These recommendations included carbohydrates (330-450g), proteins (48-60g), fibres (19-48g), energy (2400Kcal), calcium (600-960 mg), and salt (<5gm/day) [

24]. Subjects were specifically advised to limit extra salt, caffeine and sugar intake. Special weighted scoops were provided to each participant in order to estimate the amount of specific food intake at certain meals (e.g., rice, pasta, etc.). Then, all the participants were instructed to fill in an online form of their type and amount of food intake twice per week. The dietician assessed the compliance to healthy diet and gave more advice where necessary. A motivational phone consultation for each participant in the intervention group was carried out by the principal and co-principal investigators once every two weeks throughout the study period. It basically included motivating the participants to comply with the dietary advice given and explore any challenges that they may have encountered which may impede their adherence. Moreover, one parent was instructed by phone every two weeks to ensure the compliance of his/her daughter to dietary advice. Subjects in the control group did not receive any dietary advice at baseline. However, dietary counselling for each subject in the control group was provided at the end of the study by the same dietician. Similar recommendations, regarding physical exercise, were provided to both intervention and control groups at baseline.

Assessment approach

At baseline, the sociodemographic questionnaire was administered to both study groups, which included basic sociodemographic features such as age, marital status, chronic conditions such as thyroid disease, medications use, smoking, alcohol status and substance use. In addition, at baseline and by the end of the study, the DRSP (Arabic version) was disseminated across participants of the control and intervention groups. The DRSP tool is known for its high sensitivity, specificity, and validity in calculating the PMS and PMDD incidence rates [

25]. Moreover, it is a highly reliable instrument based on its capacity to track PMS symptoms and their alterations during menstruation. It is also known to evaluate treatment responses in PMS-affected patients [

25]. A 24-item DRSP tool collects data regarding overall impairment as well as physical and emotional symptoms. Each DRSP item needs to be rated by the participants per day and is guided by a six-point scale to determine the symptom severity. DRSP also collects data concerning the dates and duration of menstrual bleeding [

25].

PMDD is diagnosed if the women meet all of the following criteria: i) scores at least four in one of more symptoms of depression (items 2–4), anxiety (item 5) , liability (item 6) and anger (items 7 and 8) for two days or more before menses; ii) scores at least four in at least five of the symptoms listed in items 9–22 for two days or more before menses; iii) scores at least four in at least one of the three impairment items (items 23–25). If the woman does not meet one or more of the above criteria, then she will be diagnosed as having PMS. Neither PMS nor PMDD will be diagnosed if the woman denies any symptoms. The Arabic version of DRSP has been already validated and considered as a sensitive and reliable tool [

11]

. Notably, as women will be diagnosed to have PMS based on their response to DRSP over a two-month period, the second month’s response will be considered as the baseline response. Difference in the mean value of DRSP during the one week before menses between the two groups at the end of the study is considered as a primary outcome for this study.

Moreover, a PSS was filled by the participants at baseline and by the end of the study. It is a self-reporting instrument that assesses the degree to which the individual perceives his/her situation as stressful [

26]. It consists of 14 items related to the thoughts and feelings a person had during the last month. The Arabic version has already been validated [

27] and the differences in mean score between the two groups at the end of the study will be considered as the secondary outcome of this study.

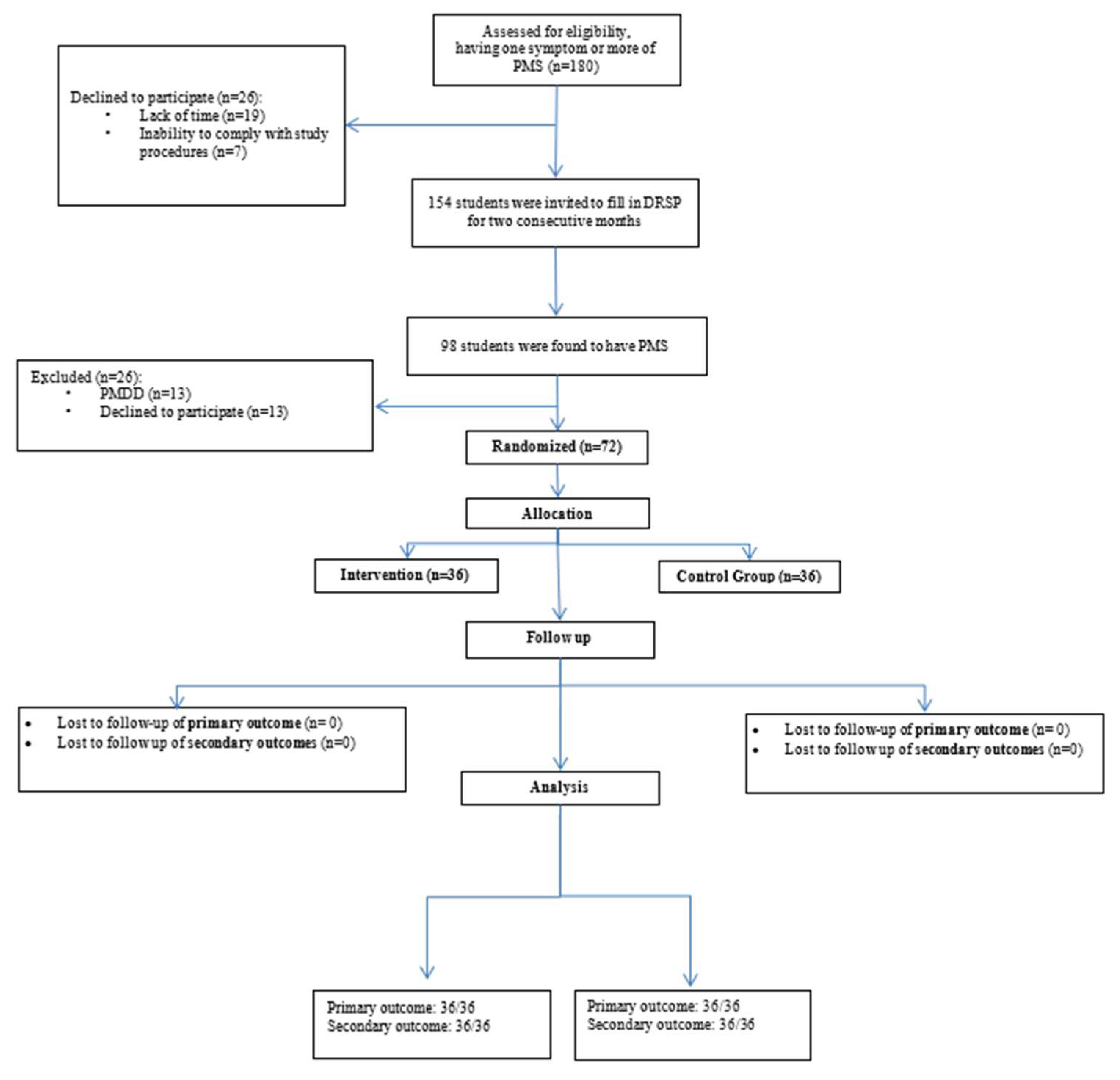

Supplementary figure S1 presents the screening and the randomization processes, while

supplementary figure S2 illustrates the study procedures and equipment.

Statistical analysis:

The trial was reported using the intention-to-treat analysis method. The difference in the DRSP scores (primary outcome) and PSS scores (secondary outcomes) from baseline to the end of intervention was compared between randomized groups using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and differences in scores reported as adjusted mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (i.e., adjusted for the baseline score as the covariate). Categorical outcomes were compared between groups using Chi-square tests. All tests were two-tailed and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The screening process was initiated after the initial interviews of candidates by the principal and co-principal investigators (

Figure 1).

Ninety participants from each school were notified and invited to register and participate in the screening process (n=180). However, 26 students (12 from school A and 14 from school B) did not provide their consent for the screening process, due to time constraints and unwillingness to adhere to the study protocols. These were subsequently excluded. In addition, PMS was confirmed in 48 school A and 50 school B students, following their DRSP inputs for two consecutive months. Six students from school A and seven from school B were diagnosed with PMDD and were referred to the nearest local health centre. Finally, 42 and 43 students from school A and school B, respectively, were found to be eligible to participate in this randomized controlled study. Furthermore, six students from school A and seven from school B could not participate in the study due to a time deficit. Eventually, 36 students from school A and equal numbers from school B were categorized into the control and intervention groups, respectively. No loss to follow-up was reported within the study tenure.

Table 1 presents the baseline attributes of both intervention and control groups (n=36, each); their comparative analysis revealed no statistically significant differences (all p>0.05). Additionally, no statistically significant differences between the study groups were reported for menstrual cycle length (p=0.493), bleeding amount (p=0.326), dysmenorrhea (p=0.54), and absenteeism from school (p=0.430). No statistically significant differences between the study groups were reported for the dietary intake variables, including fish, legumes, vegetables, fruits, refined carbohydrate-rich diet, sugar, caffeine, carbonated drinks, chocolate and related food items, and fat-rich diets (all p>0.05). Differences in other variables, including mother’s education, father’s education, and exercise also lacked statistical significance (all p>0.5).

The Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) of subsections (depressive symptoms; physical symptoms and anger and irritability) and also the total scores of Daily Record of Severity of Problems questionnaire (DRSP) in the two groups (

Table 2) revealed no significant differences at the end of the first and second month’s follow-ups, as compared to the baseline scores (all p >0.05) (

Table 2).

With regards to the PSS outcomes at baseline and after two months between the control and intervention groups; the findings were also devoid of any statistically significant change (p=0.216) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Our study revealed no significant association between healthy and well-balanced dietary intake and symptoms of premenstrual syndrome based on the daily record of severity of problems questionnaire (DRSP). Additionally, no significant association was found between a healthy diet in adolescents with premenstrual syndrome, and quality of life as measured by the PSS.

Our results support the outcomes of several studies that demonstrate an insignificant relationship between PMS symptoms and carbohydrate intake [

18,

28]. Furthermore, evidence refuted any significant association between PMS and fat intake, including trans/polyunsaturated/monounsaturated fats [

29]. However, findings from some studies predicted the possible role of saturated fat in minimizing PMS predisposition in women [

29,

30]. Outcomes from some other studies further negate any significant relationship between PMS risk and total protein/amino acid intake in females [

31]. Besides, few studies demonstrate an inverse relationship between PMS symptoms and high coffee consumption or increased carbohydrate intake [

32,

33].

Findings from a UAE-based study by Hashim et al. advocated the detrimental effects of salt-based diets, high sugar intake, fat-based food intake, high-calorie diets, and smoking on physical symptoms of PMS [

19]. Alternatively, they revealed a statistically significant inverse relationship between PMS-related behavioural symptoms and fruit consumption. Another Korea-based cross-sectional study revealed no significant relationship between PMS risk and consumption of alcohol, meat, or traditional diets [

34]. A recent review paper by Simini and Turcanu provided substantial evidence indicating no statistically significant association between PMS and the intake of macronutrients, including fibres, carbohydrates, fat, and proteins [

30]. Contrarily, the outcomes indicate the impact of micronutrients on PMS symptoms; these micronutrients include herbal supplements, vitamin B complex, vitamin D, magnesium, and calcium [

30]. Another qualitative study by Quaglia et al. indicated a strong association between PMS symptom burden and total energy intake, based on food items, including micro/macronutrients [

35]. Overall, most studies in the literature supported our findings concerning the absence of a statistically significant relationship between PMS symptoms and a healthy, balanced diet.

The pathology of PMS and the diversity of its symptoms appear to impact these results, which require further evaluation via prospective studies. To date, no clinical study can explain and elaborate on the multifactorial symptomatology of PMS [

36]. Rare evidence is available on the possible impact of psychosocial complications and hormonal imbalances on PMS symptoms, including their severity, risk, and incidence. The pathophysiology of PMS is based on the activity of catecholamine, serotonin, opioids, GABA, and progesterone [

37]. Importantly, increased progesterone sensitivity with a preexisting serotonin deficiency is also considered responsible for PMS symptom severity [

37]. Other potential PMS-triggering factors include genetic factors, electrolyte deficiency, insulin resistance, improper hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity, abnormal glucose metabolism, and elevated prolactin. The sympathetic activity, amplified by the stress levels potentiates uterine contraction, which eventually increases the severity and frequency of menstrual pain [

37]. Several comorbid conditions, including hyperprolactinemia and Cushing syndrome, disturb the normal levels of cortisol, thyroid stimulating hormone, estradiol, and follicular stimulating hormone in women, thereby predisposing them to PMS [

38].

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the small sample size impacts the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the lack of blinding despite its randomized controlled design increases the risk of selection bias. Moreover, the use of self-reported questionnaires might have further impacted the reliability of results. Lastly, the lack of an objective scale to measure the adherence to dietary advice might have a negative impact on the final results.

Recommendations

Despite that a variety of cross-sectional studies to date have evaluated the relationships between PMS and dietary patterns, the paucity of evidence substantiated the need to conduct prospective randomized studies with larger sample sizes to understand the potential factors impacting the PMS manifestations. These randomized studies should also explore the possible role of geographical variations and culture-based diets on PMS progression and its clinical manifestations in adolescent and adult females. Clinical trials should further explore the interactions between diets and medications and their possible influence on PMS development in females of various age groups.

5. Conclusions

The overall findings from this study revealed a nonsignificant association between healthy balanced diet, motivational follow-ups, and PMS symptom improvements. Although our research did not find statistically significant results supporting the effectiveness of dietary modifications and motivational support as treatments for PMS, it is crucial to recognize the study’s limitations, including the small sample size. Future prospective studies with larger and more diverse sample sizes are needed to allow for a more robust analysis of the relationships between dietary habits, motivational interventions, and PMS symptomatology.

6. Patents

Not applicable.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1,

Figure S1: Screening and Randomization. Figure S2: Study Procedures and Equipment.

Author Contributions

MHK contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—original draft, project administration, funding acquisition, and supervision. ZB contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—original draft, project administration, funding acquisition. AA, RM, FR, AS, & AM: contributed to investigation and project administration. SJ contributed to methodology, formal analysis and writing—original draft.

Funding

This study was supported by Sultan Qaboos University (Deanship of Research Fund RF/MED/FMCO/21/02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Directorate General of Planning and Studies, Ministry of Health, Oman (MoH/CSR/20/23884). Additionally, The trial is registered with the WHO/Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials # IRCT20201129049526N1.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

data supporting the reported results can be provided by the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

authors would like to thank all participants and the school nurses from the Directorate General of Primary Care in Muscat region.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sattar, K. Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2014, 8, 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Ismaili, E.; Walsh, S.; O’Brien, P.M.S.; Bäckström, T.; Brown, C.; Dennerstein, L.; Eriksson, E.; Freeman, E.W.; Ismail, K.M.K.; Panay, N.; et al. Fourth Consensus of the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders (ISPMD): Auditable Standards for Diagnosis and Management of Premenstrual Disorder. Arch. Womens. Ment. Health 2016, 19, 953–958. [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Bouyer, J.; Trussell, J.; Moreau, C. Premenstrual Syndrome Prevalence and Fluctuation over Time: Results from a French Population-Based Survey. J. Women’s Heal. 2009, 18, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshani, N.M.; Mousavi, M.N.; Khodabandeh, G. Prevalence and Severity of Premenstrual Symptoms among Iranian Female University Students. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2009, 59, 205–208.

- Halbreich, U.; Borenstein, J.; Pearlstein, T.; Kahn, L.S. The Prevalence, Impairment, Impact, and Burden of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, T.; Yonkers, K.A.; Fayyad, R.; Gillespie, J.A. Pretreatment Pattern of Symptom Expression in Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister,S.; Bodden,S. Premenstural Syndrome and Premenstural Dysphoric Disorder. Am Fam Physician 2016, 94, 236-240.

- Eriksson, O.; Wall, A.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Ågren, H.; Hartvig, P.; Blomqvist, G.; Långström, B.; Naessén, T. Mood Changes Correlate to Changes in Brain Serotonin Precursor Trapping in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoria. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2006, 146, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.W. Recognizing and Treating Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder in the Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Primary Care Practices. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61, 9–16.

- Schoep, M.E.; Nieboer, T.E.; van der Zanden, M.; Braat, D.D.M.; Nap, A.W. The Impact of Menstrual Symptoms on Everyday Life: A Survey among 42,879 Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 569.e1-569.e7. [CrossRef]

- Hussein Shehadeh, J.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M. Prevalence and Association of Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder with Academic Performance among Female University Students. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 176–184. [CrossRef]

- Wittchen, H.U.; Becker, E.; Lieb, R.; Krause, P. Prevalence, Incidence and Stability of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder in the Community. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Amiel Castro, R.T.; Pataky, E.A.; Ehlert, U. Associations between Premenstrual Syndrome and Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Literature Review. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 147, 107612. [CrossRef]

- Marjoribanks, J.; Brown, J.; O’Brien, P.M.S.; Wyatt, K. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Premenstrual Syndrome. Cochrane database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD001396. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M. Cognitive Behavioural Interventions for Premenstrual and Menopausal Symptoms. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2003, 21, 183–193. [CrossRef]

- Appleton, S.M. Premenstrual Syndrome: Evidence-Based Evaluation and Treatment. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 52–61. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.G.; Carr-Nangle, R.E.; Bergeron, K.C. Macronutrient Intake, Eating Habits, and Exercise as Moderators of Menstrual Distress in Healthy Women. Psychosom. Med. 1995, 57, 324–330. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.C.; Manson, J.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Troy, L.M.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Carbohydrate and Fiber Intake and the Risk of Premenstrual Syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 861–870. [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.S.; Obaideen, A.A.; Jahrami, H.A.; Radwan, H.; Hamad, H.J.; Owais, A.A.; Alardah, L.G.; Qiblawi, S.; Al-Yateem, N.; Faris, “Mo’ez Al-Islam” E. Premenstrual Syndrome Is Associated with Dietary and Lifestyle Behaviors among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study from Sharjah, UAE. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1939. [CrossRef]

- Cross, G.B.; Marley, J.; Miles, H.; Willson, K. Changes in Nutrient Intake during the Menstrual Cycle of Overweight Women with Premenstrual Syndrome. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 85, 475–482. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Premenstual Syndrome (PMS) Available online: https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/premenstrual-syndrome (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders : DSM-5-TR; 2022; ISBN 9780890425756.

- CMC NMaster Sample Size Calculation Software 2.0 2012.

- Ministry of Health; Oman. The Omani Guide to Healthy Eating. In; 2009; pp. 1–45.

- Endicott, J.; Nee, J.; Harrison, W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): Reliability and Validity. Arch. Womens. Ment. Health 2006, 9, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385. [CrossRef]

- Almadi, T.; Cathers, I.; Hamdan Mansour, A.M.; Chow, C.M. An Arabic Version of the Perceived Stress Scale: Translation and Validation Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 84–89. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.; Hirokawa, K.; Shimizu, N.; Shimizu, H. Soy, Fat and Other Dietary Factors in Relation to Premenstrual Symptoms in Japanese Women. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2004, 111, 594–599. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.C.; Manson, J.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Troy, L.M.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Intake of Dietary Fat and Fat Subtypes and Risk of Premenstrual Syndrome in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 849–857. [CrossRef]

- Siminiuc, R.; Ţurcanu, D. Impact of Nutritional Diet Therapy on Premenstrual Syndrome. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1079417. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.C.; Manson, J.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Troy, L.M.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Protein Intake and the Risk of Premenstrual Syndrome. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1762–1769. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, P.; Al-Sowielem, L.S. Prevalence and Predictors of Premenstrual Syndrome Among College–Aged Women in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2003, 23, 381–387. [CrossRef]

- Seedhom, A.E.; Mohammed, E.S.; Mahfouz, E.M. Life Style Factors Associated with Premenstrual Syndrome among El-Minia University Students, Egypt. ISRN Public Health 2013, 2013, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-J.; Sung, D.-I.; Lee, J.-W. Association among Premenstrual Syndrome, Dietary Patterns, and Adherence to Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2460. [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, C.; Nettore, I.C.; Palatucci, G.; Franchini, F.; Ungaro, P.; Colao, A.; Macchia, P.E. Association between Dietary Habits and Severity of Symptoms in Premenstrual Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1717. [CrossRef]

- A, D. M., K, S., A, D., & Sattar, K. (2014). Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR, 8(2), 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Gudipally,P,R.; Sharma,G,K. Premenstrual Syndrome. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2023.

- Huan, C.; Lu, C.; Xu, G.; Qu, X.; Qu, Y. Retrospective Analysis of Cushing’s Disease with or without Hyperprolactinemia. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).