Submitted:

27 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

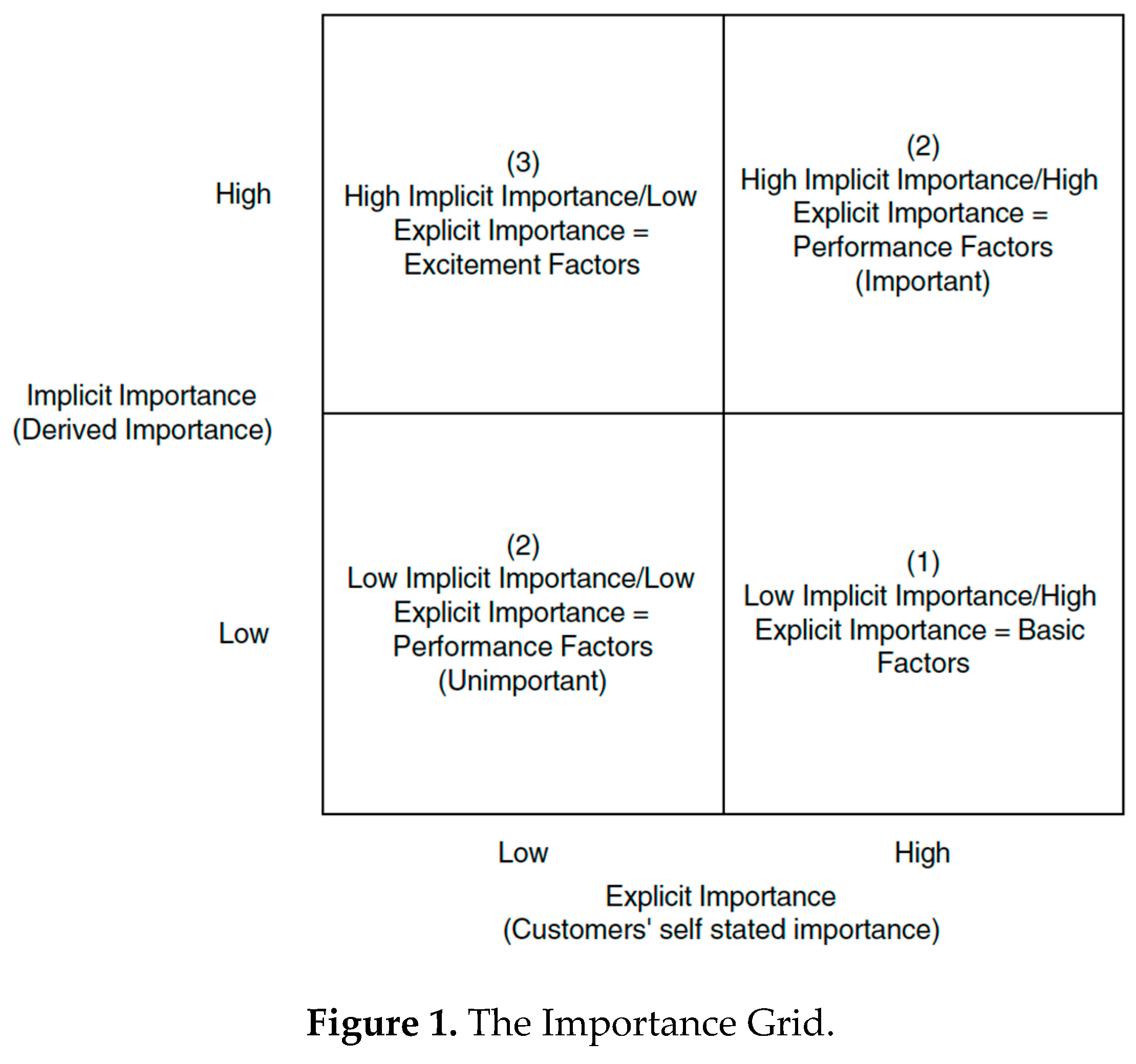

2.1. Importance Grid Analysis

- Basic factors: these are minimum requirements that cause dissatisfaction if not fulfilled but do not lead to user satisfaction if fulfilled or exceeded. That is, those factors that the user expects to find, and not finding them would generate dissatisfaction. The user regards the basic factors as prerequisites, he takes them for granted and therefore does not explicitly demand them. Therefore, these factors must always be provided.

- Performance factors: these factors lead to satisfaction if fulfilled or exceeded and lead to dissatisfaction if not fulfilled. Performance factors are characterized by a linear relationship between their presence and the user's willingness to walk. Therefore, the higher the performance of these factors on the road environment, the greater the user's willingness to walk. They are divided into important factors and irrelevant factors according to their position in the Importance grid. Governments must focus their resources on increasing these factors, especially the important ones.

- Excitement factors: these are the factors that increase user's willingness to walk if present but do not reduce user's willingness if they are not present. The excitement factors are those that the user does not expect and, when they are provided, give rise to a lot of appreciation (the relationship between fulfillment and satisfaction, in this case, is exponential). Therefore, the Governments must focus on the performance of these factors only after having guaranteed those of the performance factors.

2.2. Data collection

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Analysis

| Total | Men | Women | Age0 | Age1 | Age2 | Age3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 0.701 | 0.689 | 0.714 | 0.659 | 0.682 | 0.732 | 0.773 |

| PC2 | 0.722 | 0.712 | 0.734 | 0.675 | 0.686 | 0.750 | 0.852 |

| PC3 | 0.744 | 0.722 | 0.766 | 0.722 | 0.697 | 0.790 | 0.841 |

| PC4 | 0.513 | 0.503 | 0.524 | 0.464 | 0.485 | 0.612 | 0.534 |

| PC5 | 0.568 | 0.578 | 0.557 | 0.552 | 0.551 | 0.576 | 0.625 |

| C1 | 0.680 | 0.665 | 0.695 | 0.631 | 0.669 | 0.728 | 0.716 |

| C2 | 0.676 | 0.681 | 0.672 | 0.623 | 0.661 | 0.674 | 0.795 |

| C3 | 0.748 | 0.726 | 0.772 | 0.683 | 0.739 | 0.772 | 0.835 |

| C4 | 0.754 | 0.760 | 0.748 | 0.734 | 0.767 | 0.737 | 0.773 |

| C5 | 0.688 | 0.672 | 0.704 | 0.651 | 0.686 | 0.710 | 0.716 |

| C6 | 0.739 | 0.708 | 0.772 | 0.675 | 0.750 | 0.799 | 0.727 |

| C7 | 0.839 | 0.816 | 0.863 | 0.798 | 0.850 | 0.853 | 0.852 |

| S1 | 0.548 | 0.536 | 0.560 | 0.524 | 0.536 | 0.594 | 0.557 |

| S2 | 0.736 | 0.724 | 0.748 | 0.710 | 0.712 | 0.786 | 0.773 |

| S3 | 0.682 | 0.667 | 0.699 | 0.647 | 0.665 | 0.723 | 0.727 |

| S4 | 0.609 | 0.613 | 0.606 | 0.611 | 0.595 | 0.656 | 0.585 |

| S5 | 0.593 | 0.590 | 0.597 | 0.583 | 0.581 | 0.616 | 0.614 |

| S6 | 0.593 | 0.580 | 0.606 | 0.567 | 0.591 | 0.620 | 0.602 |

| S7 | 0.765 | 0.745 | 0.786 | 0.738 | 0.748 | 0.826 | 0.773 |

| S8 | 0.731 | 0.710 | 0.754 | 0.714 | 0.737 | 0.759 | 0.705 |

| A1 | 0.712 | 0.667 | 0.759 | 0.659 | 0.710 | 0.746 | 0.750 |

| A2 | 0.812 | 0.790 | 0.836 | 0.786 | 0.824 | 0.839 | 0.784 |

| A3 | 0.681 | 0.658 | 0.704 | 0.635 | 0.686 | 0.746 | 0.648 |

| A4 | 0.794 | 0.757 | 0.832 | 0.726 | 0.805 | 0.817 | 0.830 |

| Mean | 0.693 | 0.678 | 0.709 | 0.657 | 0.684 | 0.727 | 0.724 |

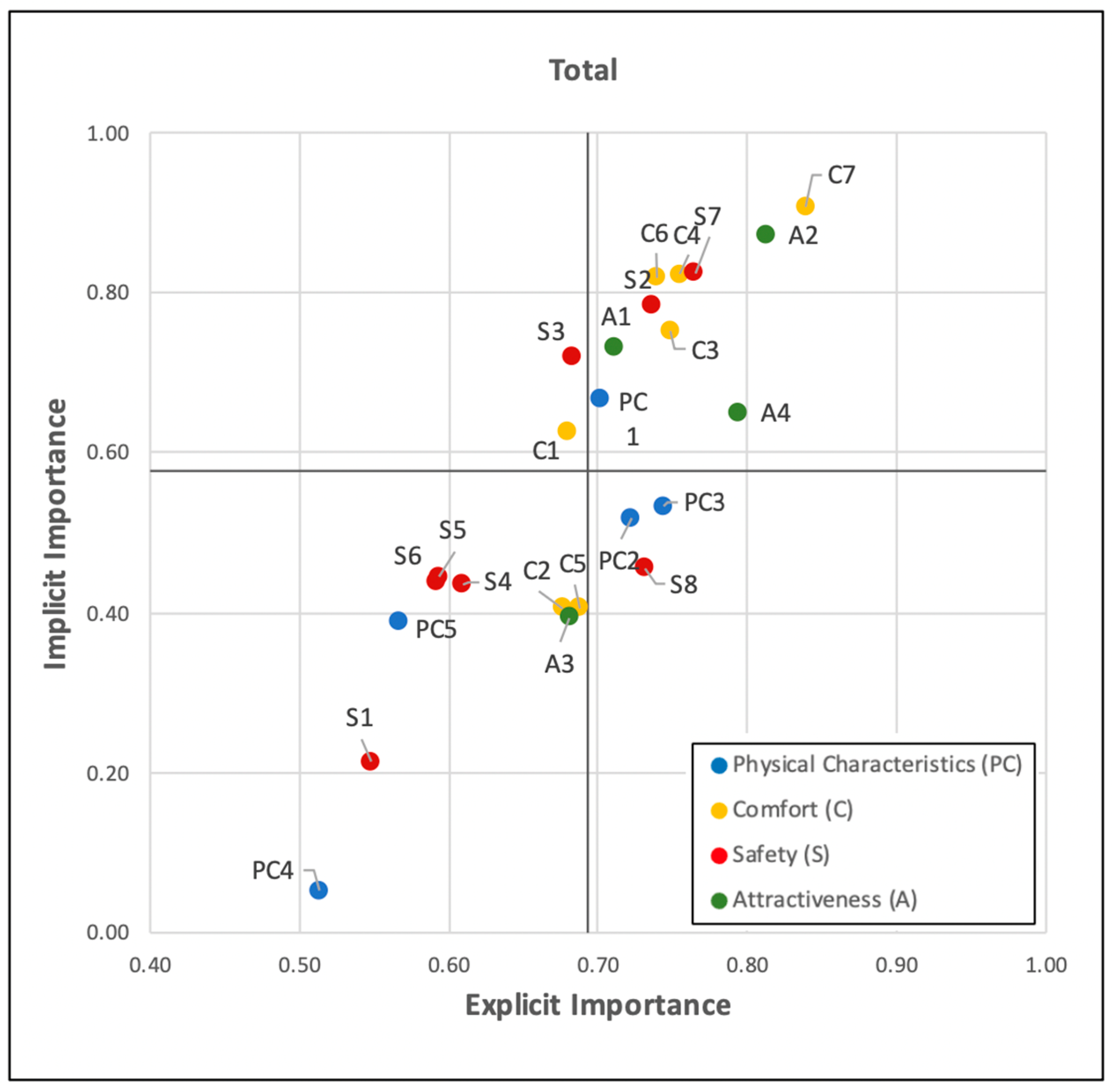

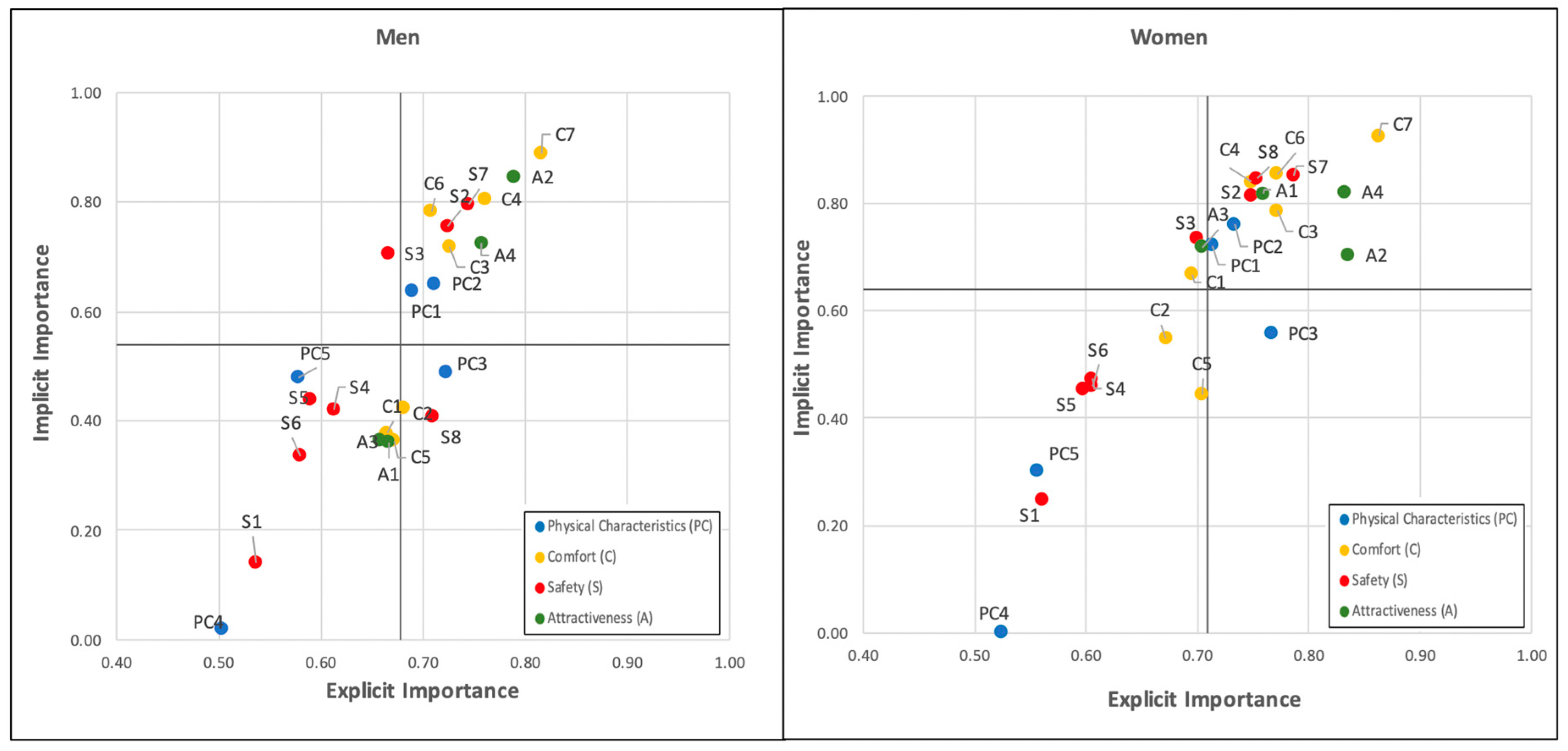

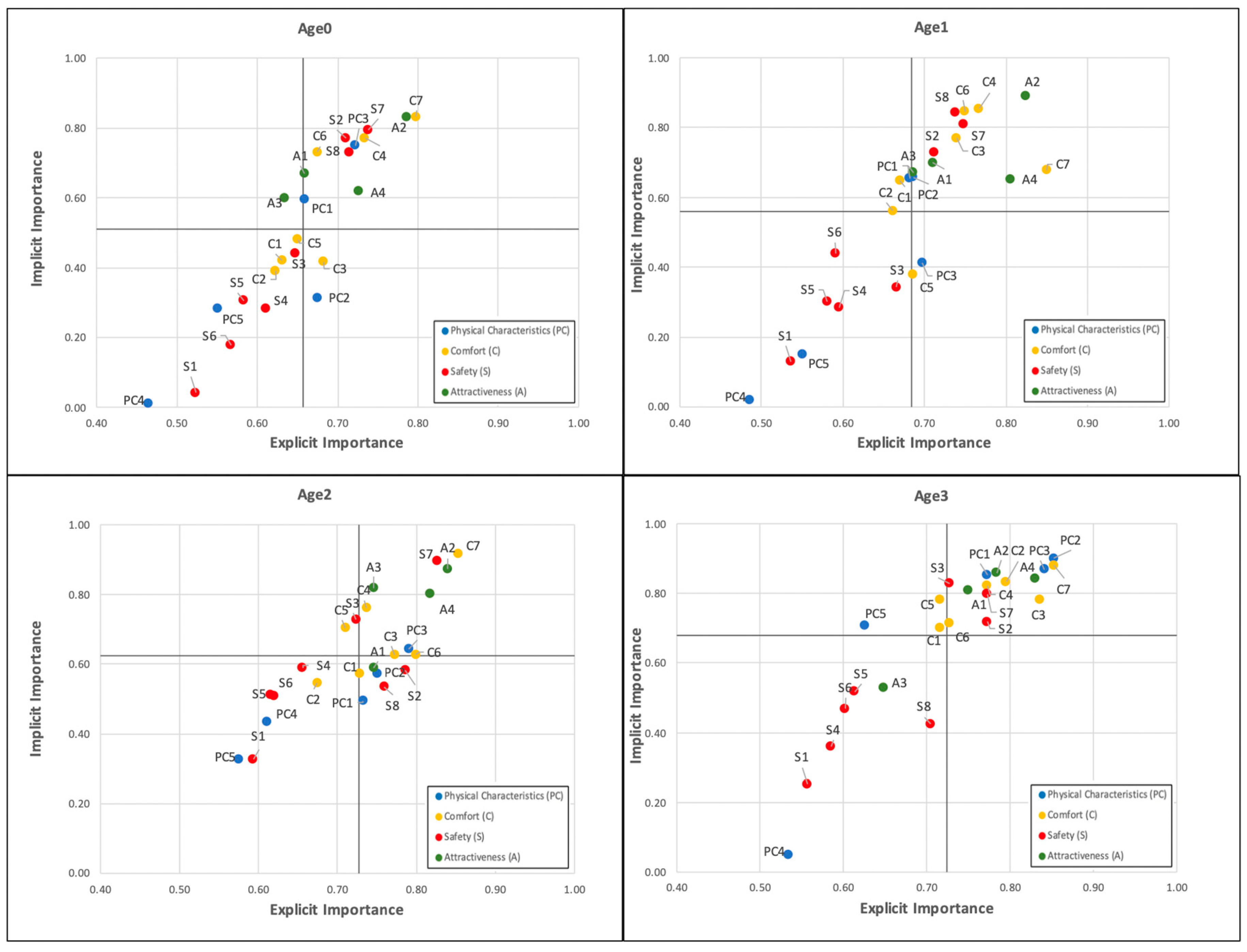

3.3. Factors classification based on IG

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Characteristics

4.2. Comfort

4.3. Safety

4.4. Attractiveness

5. Conclusions

- ➢

- In the realm of Physical Characteristics, factors such as sidewalk width and surface condition are considered "Basic Factors." They are expected and don't significantly boost willingness to walk. However, sidewalk continuity, though not a dominant influence, does affect willingness. Gender-based differences in judgments are notably absent in this regard.

- ➢

- Comfort factors, on the other hand, assume significance. Among them, the absence of obstacles on pedestrian paths stands out as an excitement factor. This is especially pronounced among older pedestrians, highlighting their higher mobility needs.

- ➢

- When it comes to Safety, it's intriguing to note that half of the factors in this category are perceived as factors of irrelevant importance by both the total sample and gender-based subgroups. Yet, ease of intersection crossing and low vehicular traffic flow are positively linked to willingness to walk. The significance of pedestrian safety varies, influenced by the walking culture and road safety attitudes prevalent in the survey location.

- ➢

- The Attractiveness of pedestrian paths, in general, amplifies willingness to walk. For women and younger individuals, the presence of other pedestrians contributes positively, as it's associated with heightened security. Contrarily, this factor is deemed unimportant by men and older pedestrians, who emphasize the relevance of other attractiveness factors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anciaes, P.; Jones, P. Transport policy for liveability – Valuing the impacts on movement, place, and society. Transp. Res. A: Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, R.; Croft, J. Evaluating active travel and health economic impacts of small streetscape schemes: An exploratory study in London. J. Transp. Health. 2019, 12, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrañaga, A. M.; Rizzi, L. I.; Arellana, J.; Strambi, O.; Cybis, H. B. B. The influence of built environment and travel attitudes on walking: A case study of Porto Alegre, Brazil. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2016, 10, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L. D.; Sallis, J. F.; Saelens, B. E.; Leary, L.; Cain, K.; Conway, T. L.; Hess, P. M. The development of a walkability index: application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar Miranda, A.; Fan, Z.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C. Desirable streets: Using deviations in pedestrian trajectories to measure the value of the built environment. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 86, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, A.; Chiaradonna, S.; Mihiel, A. C. d. S.; Lovegrove, G.; Nunziante, P.; Rella Riccardi, M. Sustainable Complete Streets Design Criteria and Case Study in Naples, Italy. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 14, 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, N.; Pulvirenti, G.; Leonardi, S. Neighbourhood walkability: Elderly's priorities. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, R.; Blakely, T.; Kavanagh, A.; Aitken, Z.; King, T.; McElwee, P.; Giles-Corti, B.; Turrell, G. A Longitudinal Study Examining Changes in Street Connectivity, Land Use, and Density of Dwellings and Walking for Transport in Brisbane, Australia. Environ. Health Persp. 2018, 126, 057003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosal Hoy, K.; Puławska-Obiedowska, S. The Travel Behaviour of Polish Women and Adaptation of Transport Systems to Their Needs. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 13, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Robledo, V.; Escovar-Álvarez, G. Domestic workers’ commutes in Bogotá: Transportation, gender and social exclusion. Transp. Res. A: Policy Pract. 2020, 139, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillnhütter, H. Stimulating urban walking environments – Can we measure the effect? Environ. Plan. B: Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A. I.; Hoffimann, E. Development of a Neighbourhood Walkability Index for Porto Metropolitan Area. How Strongly Is Walkability Associated with Walking for Transport? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018, 15, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wey, W.; Huang, J. Urban sustainable transportation planning strategies for livable City's quality of life. Habitat Int. 2018, 82, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatar, K. M. Towards sustainable green mobility in the future of Saudi Arabia cities: Implication for reducing carbon emissions and increasing renewable energy capacity. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Neighbourhood walkability: A review and bibliometric analysis. Cities 2019, 93, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Veitch, J.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Thornton, L.; Ball, K. Environmental perceptions as mediators of the relationship between the objective built environment and walking among socio-economically disadvantaged women. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisiopiku, V. P.; Akin, D. Pedestrian behaviors at and perceptions towards various pedestrian facilities: an examination based on observation and survey data. Transp. Res. F: Traffic Psychol. 2003, 6, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julio, R.; Monzon, A.; Susilo, Y. O. Identifying key elements for user satisfaction of bike-sharing systems: a combination of direct and indirect evaluations. Transportation (Dordrecht) 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echaniz Beneitez, E.; Ho, C. Q.; Dell´Olio, L.; Rodríguez Gutiérrez, A. ; Universidad de Cantabria Comparing best-worst and ordered logit approaches for user satisfaction in transit services. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Xue, Y.; Cao, J.; Sun, S. Exploring satisfaction of choice and captive bus riders: An impact asymmetry analysis. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2021, 93, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J. A.; James, J. C. Importance-Performance Analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive Quality and Must-Be Quality. Qual. Eng. J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control. 1984, 14, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danioni, F.; Coen, S.; Rosnati, R.; Barni, D. The relationship between direct and indirect measures of values: Is social desirability a significant moderator? Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2020, 70, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Huting, J. Using three-factor theory to identify improvement priorities for express and local bus services: An application of regression with dummy variables in the Twin Cities. Transp. Res. Part A Policy. Pract. 2018, 113, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cao, X.; Nagpure, A.; Agarwal, S. Exploring rider satisfaction with transit service in Indore, India: an application of the three-factor theory. Transp. Lett. 2019, 11, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Cao, X. Comparing importance-performance analysis and three-factor theory in assessing rider satisfaction with transit. J. Transp. Land Use 2017, 10, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Biosca, S. A. Choice of transport in urban and periurban zones in metropolitan area. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 100, 103331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatum, K.; Parnell, K.; Cekic, T. I.; Knieling, J. Driving factors of sustainable transportation: Satisfaction with mode choices and mobility challenges in oxfordshire and hamburg. Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr. 2019, 3, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, S. E.; Showalter, M. J. The Performance-Importance Response Function: Observations and Implications. Serv. Ind. J. 1999, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavra, T. G. Improving Your Measurement of Customer Satisfaction; ASQ Quality Press: La Vergne, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonzo, M. A. To Walk or Not to Walk? The Hierarchy of Walking Needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, K.; Abdelmonem, M. G.; Selim, G. Understanding Walkability in the Libyan Urban Space: Policies, Perceptions and Smart Design for Sustainable Tripoli. 2016.

- Abou-Senna, H.; Radwan, E.; Mohamed, A. Investigating the correlation between sidewalks and pedestrian safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 166, 106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaabbasi, M.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M.; Asadi-Shekari, Z. A new assessment model to evaluate the microscale sidewalk design factors at the neighbourhood level. J. Transp. Health. 2017, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Mannering, F. L. Statistical analysis of pedestrian perceptions of sidewalk level of service in the presence of bicycles. Transp. Res. A: Policy Pract. 2013, 53, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M. A pedestrian level of service method for evaluating and promoting walking facilities on campus streets. Land use policy 2014, 38, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellana, J.; Saltarín, M.; Larrañaga, A. M.; Alvarez, V.; Henao, C. A. Urban walkability considering pedestrians' perceptions of the built environment: a 10-year review and a case study in a medium-sized city in Latin America. Transp. Rev. 2020, 40, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tondelli, S.; Ribeiro, P.; Conticelli, E.; Jabbari, M.; Ramos, R. Perceived Walkability and Respective Urban Determinants: Insights from Bologna and Porto. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 14, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, S.; Ruiz, T.; Mars, L. A qualitative study on the role of the built environment for short walking trips. Transp. Res. F: Traffic Psychol. 2015, 33, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Sze, N. N.; Newnam, S. Effect of urban street trees on pedestrian safety: A micro-level pedestrian casualty model using multivariate Bayesian spatial approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 176, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troped, P. J.; Cromley, E. K.; Fragala, M. S.; Melly, S. J.; Hasbrouck, H. H.; Gortmaker, S. L.; Brownson, R. C. Development and Reliability and Validity Testing of an Audit Tool for Trail/Path Characteristics: The Path Environment Audit Tool (PEAT). J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S158–S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eggermond, M. A. B.; Erath, A. Pedestrian and transit accessibility on a micro level. J. Transp. Land Use 2016, 9, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barón, L.; Otila da Costa, J.; Soares, F.; Faria, S.; Prudêncio Jacques, M. A.; Fraga de Freitas, E. Effect of Built Environment Factors on Pedestrian Safety in Portuguese Urban Areas. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2021, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, A.; Botzoris, G.; Eliou, N. Pedestrian road safety in relation to urban road type and traffic flow. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, N.; Leonardi, S. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Traffic Calming Measures by SPEIR Methodology: Framework and Case Studies. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 14, 7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; Martín, B. ; De Isidro, Á; Cuevas-Wizner, R. Street walking quality of the 'Centro' district, Madrid. J. Maps 2020, 16, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, S.; Distefano, N.; Leonardi, S. Comparative analysis of pedestrian accidents risk at unsignalized intersections. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2015, 10, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, E.; Lassarre, S.; Yannis, G. Human factors of pedestrian walking and crossing behaviour. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 2002–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Santi, P.; Courtney, T. K.; Verma, S. K.; Ratti, C. Investigating the association between streetscapes and human walking activities using Google Street View and human trajectory data. Trans. GIS 2018, 22, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M. A.; Frank, L. D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Chapman, J.; Christiansen, L. B.; Coffee, N.; Salvo, D.; du Toit, L.; Dygrýn, J.; Hino, A. A. F.; Lai, P.; Mavoa, S.; Pinzón, J. D.; Van de Weghe, N.; Cerin, E.; Davey, R.; Macfarlane, D.; Owen, N.; Sallis, J. F. International variation in neighborhood walkability, transit, and recreation environments using geographic information systems: the IPEN adult study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, D.; Khalifa, S. I.; Tarek, S. Using Landscape Qualities to Enhance Walkability in Two Types of Egyptian Urban Communities. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 1798–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleai, M.; Taheri Amiri, E. Spatial multi-criteria and multi-scale evaluation of walkability potential at street segment level: A case study of tehran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 31, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizárraga, C.; Martín-Blanco, C.; Castillo-Pérez, I.; Chica-Olmo, J. Do University Students’ Security Perceptions Influence Their Walking Preferences and Their Walking Activity? A Case Study of Granada (Spain). Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 14, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, S. T.; Larranaga, A. M.; Ochoa, J. A. A.; Samios, A. A. B.; Cybis, H. B. B. The role of security and walkability in subjective wellbeing: A multigroup analysis among different age cohorts. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, T. M.; Wagnild, J. M. Gender differences in walking (for leisure, transport and in total) across adult life: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonatto, D. d. A. M.; Alves, F. B. Application of Walkability Index for Older Adults' Health in the Brazilian Context: The Case of Vitória-ES, Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Bibeka, A.; Sun, X.; Zhou, H.; Jalayer, M. Elderly Pedestrian Fatal Crash-Related Contributing Factors: Applying Empirical Bayes Geometric Mean Method. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 254–263. [CrossRef]

- Maisel, J. L. Impact of Older Adults’ Neighborhood Perceptions on Walking Behavior. J Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 24, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoh, K.; Khaimook, S.; Doi, K.; Yamamoto, T. Study on influence of walking experience on traffic safety attitudes and values among foreign residents in Japan. IATSS Res. 2022, 46, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, N.; Haque, M. M.; King, M.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. The unequal gender effects of the suburban built environment on perceptions of security. J. Transp. Health 2021, 23, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Kamani-Fard, A.; Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R. Perceived security of women in relation to their path choice toward sustainable neighborhood in Santiago, Chile. Cities 2017, 60, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, S.; Distefano, N.; Pulvirenti, G. Identification of road safety measures for elderly pedestrians based on K-means clustering and hierarchical cluster analysis. Arch. Transp. 2020, 56, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Reference Literature | |

|---|---|---|

| Pedestrian infrastructure items relating to the Physical Characteristics (PC) | ||

| PC1 | Continuity of the sidewalk | [34] |

| PC2 | Sidewalk width | [35] |

| PC3 | Good condition of the sidewalk surface | [36] |

| PC4 | Reduced slope of the path | [35,37] |

| PC5 | Absence of driveways | [35,37] |

| Pedestrian infrastructure items relating to the Comfort (C) | ||

| C1 | Absence of fixed obstacles (trees, poles, etc.) | [38,39] |

| C2 | Absence of obstacles or obstructions (parked vehicles, merchandise from shops, etc.) | [38,40] |

| C3 | Cleaning of the pedestrian path | [35] |

| C4 | Presence of protection from atmospheric agents (trees, porches, etc.) | [35,41] |

| C5 | Presence of benches or seats | [37,42] |

| C6 | Ease of getting to a public transport stop | [43] |

| C7 | Good artificial lighting system of the path | [37,40] |

| Pedestrian infrastructure items relating to the Safety (S) | ||

| S1 | Not excessive width of the carriageway | [44] |

| S2 | Low flows of vehicular traffic | [40,45] |

| S3 | Presence of speed limits for vehicular flows | [45] |

| S4 | Presence of traffic calming measures on the carriageway | [46] |

| S5 | Presence of a parking lane adjacent to the pedestrian path | [36,44] |

| S6 | Absence of large parking areas | [47] |

| S7 | Ease of crossing at intersections | [48] |

| S8 | Ease of crossing out of intersections | [48,49] |

| Pedestrian infrastructure items relating to Attractiveness (A) | ||

| A1 | Presence of commercial activities (bars, shops, etc.) | [50,51] |

| A2 | High artistic / landscape value of the streetscape | [50,52] |

| A3 | Presence of other pedestrians | [40,53] |

| A4 | High perception of security | [54,55] |

| Variable | Items | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0: Male | 288 | 51.25 |

| 1: Female | 274 | 48.75 | |

| Age | 0: <20 years | 126 | 22.42 |

| 1: 21-35 years | 236 | 41.99 | |

| 2: 36-65 years | 112 | 19.93 | |

| 3: >65 years | 88 | 15.66 | |

| Place of Residence (Number of inhabitants) |

0: Less than 20,000 | 200 | 35.59 |

| 1: Between 20,000 and 50,000 | 206 | 36.65 | |

| 2: Greater than 50,000 | 156 | 27.76 |

| Mean Square | F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8.333 | 67.316 | 0.000 |

| Men | 4.548 | 31.517 | 0.000 |

| Women | 4.313 | 38.890 | 0.000 |

| Age0 | 1.732 | 8.735 | <0.001 |

| Age1 | 3.957 | 49.169 | 0.000 |

| Age2 | 1.694 | 8.316 | <0.001 |

| Age3 | 1.977 | 6.412 | <0.001 |

| Total | Men | Women | Age0 | Age1 | Age2 | Age3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 0.668 | 0.638 | 0.721 | 0.596 | 0.654 | 0.494 | 0.853 |

| PC2 | 0.518 | 0.649 | 0.762 | 0.314 | 0.657 | 0.571 | 0.901 |

| PC3 | 0.533 | 0.489 | 0.558 | 0.749 | 0.413 | 0.643 | 0.868 |

| PC4 | 0.053 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.435 | 0.049 |

| PC5 | 0.389 | 0.479 | 0.303 | 0.283 | 0.15 | 0.325 | 0.707 |

| C1 | 0.627 | 0.378 | 0.668 | 0.42 | 0.649 | 0.571 | 0.701 |

| C2 | 0.405 | 0.422 | 0.548 | 0.391 | 0.562 | 0.546 | 0.833 |

| C3 | 0.752 | 0.719 | 0.787 | 0.416 | 0.771 | 0.626 | 0.780 |

| C4 | 0.823 | 0.806 | 0.841 | 0.771 | 0.854 | 0.76 | 0.822 |

| C5 | 0.405 | 0.363 | 0.444 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.703 | 0.782 |

| C6 | 0.818 | 0.782 | 0.854 | 0.731 | 0.845 | 0.627 | 0.714 |

| C7 | 0.907 | 0.889 | 0.926 | 0.832 | 0.677 | 0.917 | 0.881 |

| S1 | 0.214 | 0.141 | 0.247 | 0.042 | 0.13 | 0.327 | 0.253 |

| S2 | 0.784 | 0.756 | 0.814 | 0.771 | 0.73 | 0.582 | 0.719 |

| S3 | 0.72 | 0.707 | 0.734 | 0.442 | 0.344 | 0.728 | 0.828 |

| S4 | 0.435 | 0.42 | 0.474 | 0.282 | 0.285 | 0.589 | 0.360 |

| S5 | 0.445 | 0.439 | 0.455 | 0.305 | 0.302 | 0.511 | 0.517 |

| S6 | 0.437 | 0.336 | 0.459 | 0.178 | 0.44 | 0.509 | 0.469 |

| S7 | 0.824 | 0.796 | 0.852 | 0.794 | 0.81 | 0.896 | 0.797 |

| S8 | 0.455 | 0.409 | 0.847 | 0.729 | 0.844 | 0.534 | 0.425 |

| A1 | 0.731 | 0.36 | 0.818 | 0.669 | 0.7 | 0.589 | 0.810 |

| A2 | 0.873 | 0.847 | 0.705 | 0.831 | 0.891 | 0.873 | 0.858 |

| A3 | 0.393 | 0.363 | 0.718 | 0.597 | 0.671 | 0.818 | 0.530 |

| A4 | 0.65 | 0.725 | 0.82 | 0.617 | 0.653 | 0.801 | 0.842 |

| Mean | 0.577 | 0.539 | 0.640 | 0.510 | 0.560 | 0.624 | 0.679 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).