3.2. Morphology of Welding Layer

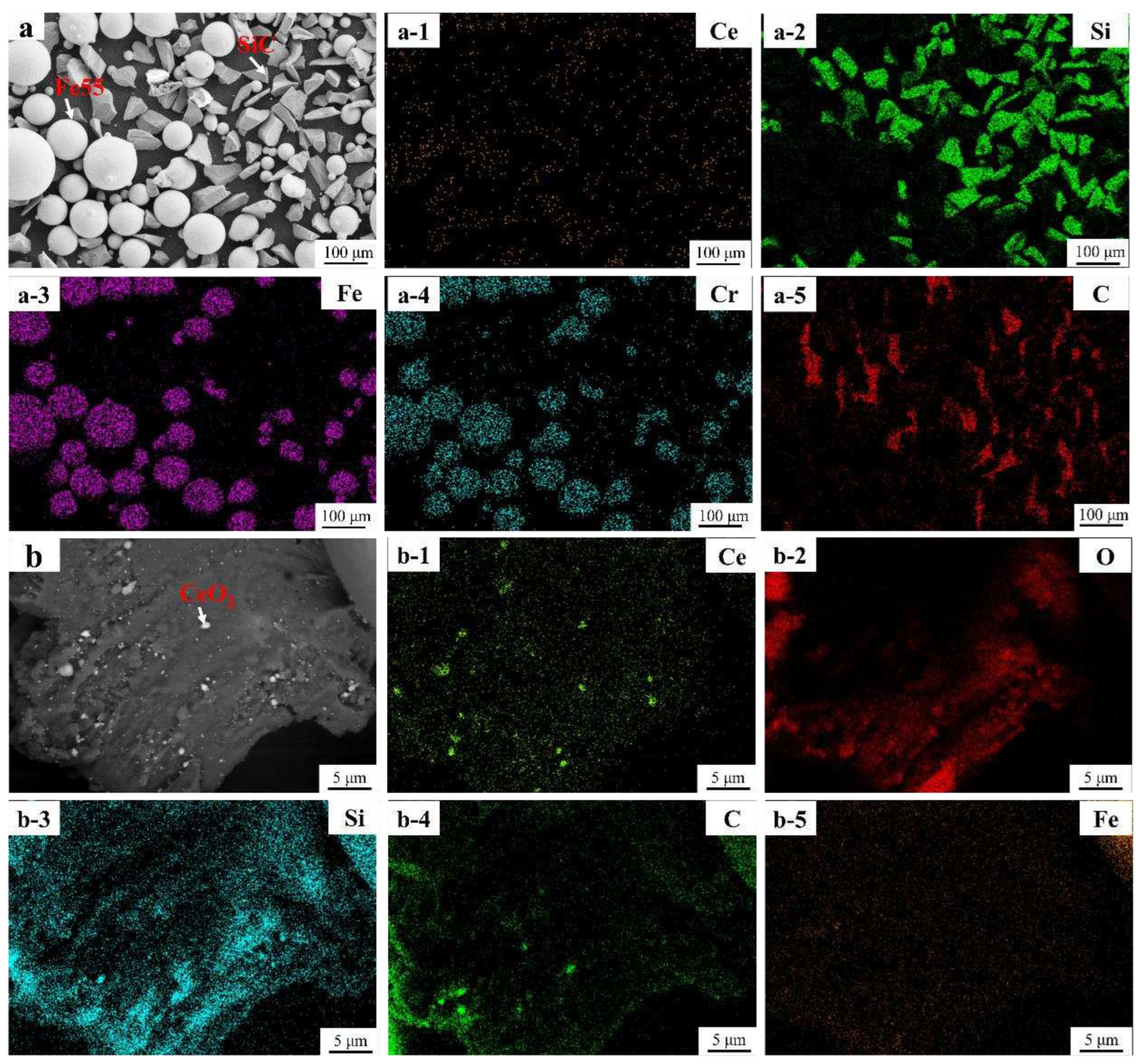

Figure 5a showed that welding path at the surface of Fe55 weld layer was no obvious. The jagged edges (red dashed line) on both sides were not obvious, indicating that it filled by molten steel. The microstructure of the Fe55 welding layer in

Figure 5a-1 and

Figure 5a-2, which taken from the yellow dashed line in

Figure 5a. The welding layer grain boundary was mainly composed of a reticular eutectic structure. The microstructure of Fe55 at the interface was mainly dendritic with differences in grain size. The γ-Fe dendrites grew directionally from 1025 steel substrate into the welding layer. During the solidification process, the substrate side absorbed a large amount of heat input from the plasma arc to maintain high temperature. The other side of the weld layer formed air convection due to shielding gas agitation and took away surface heat and maintains low temperature. A temperature gradient perpendicular to the 1025 steel substrate provided a driving force for dendrite solidification. Therefore, the dendrite exhibited a directional growth pattern perpendicular to the substrate, which was proven in Liu et al’s work[

14]. The phase and EDS mapping of Fe55 welding layer were shown in

Figure 5a-3 and 5a-4, the Cr

7C

3 hard phase was small and formed a reticular eutectic organization with γ-Fe since the welding layer was cooled faster. Although the Ar atmosphere isolated the oxygen, the [Si] reacted with [O] according to the reaction equation (1) in the molten steel to inhibit the oxidation of [Fe] and avoid the generation of (FeO) inclusions according to the reaction equation (2).

The SiO2 particles distributed along the grain boundaries with a size of 1~2 μm and agglomerated in some areas. the low melting point of SiO2 particles failed to inhibit grain growth.

Figure 5b showed the macrograph of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC. Since the molten steel flowability decreased with SiC addition [

10], the welding path and jagged edges (red dashed line) were clearer compared with Fe55. The sample was taken from the yellow dashed line in

Figure 5b. The microstructures of the welding layer were shown in

Figure 5b-1 and 5b-2. The grain boundaries consisted mainly of a reticular eutectic structure [

16]. The grains was composed of γ-Fe [

16]. The reticular eutectic structure was mainly composed of γ-Fe and Cr

2C

3 [

13]. The microstructure was dendritic and equiaxed grains. The dendrites grew directionally with the temperature gradient as driving force. In

Figure 5b-2, SiC were found on the grain boundaries and inside the grains. The number of dendrites was reduced, indicated that the dendrite growth was inhibited by the particles and form equiaxed. The SiC decomposed to [Si] and [C] at high temperatures according to the reaction equation (3).

The [Si] content in the molten steel rose and refined the grains[

15]. Moreover, the EDS mapping results of

Figure 5b-3 showed that the spherical particles were SiC. It indicated that the SiC were not completely melted and became nucleation points of γ-Fe. The SiC on the grain boundaries inhibited the grain boundary expansion. Therefore, the addition of SiC lead to the formation of equiaxed grains.

Figure 5c showed macrograph of the welding layer of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO

2. The welding path and serrated edges were clearest. The sample was taken from the yellow dashed line in

Figure 5c. The microstructures were shown in

Figure 5c-1 and 5c-2. The grain boundary was mainly composed of eutectic structure. CeO

2 increased the viscosity of the molten steel. The SiC were difficult to agglomerate after stirred and dispersed by the Ar airflow. The distribution of SiC were uniform and acted as nucleation points of γ-Fe, which promoted the formation of equiaxed grains. When the number of grains reached the limit of surface energy, the equiaxed grains fuse with each other to form petaloid grains in order to reduce the surface energy[

16]. In

Figure 5c-1, SiC were uniformly distributed inside the welding layer and were observed on the grain boundaries and inside the grains. Since the formation of rare earth compounds containing Ce and O by nano CeO

2[

17], the heterogenous nucleation of primary carbides was promoted. This resulted in larger size of Cr

7C

3 hard phases than other samples. Some SiC agglomerated in

Figure 5c-2. Although the co-addition of CeO

2 and SiC increased the viscosity of the molten steel, the collisions and agglomeration of SiC were inevitable under heating and stirring conditions in the molten steel.

Figure 5c-3 and 5c-4 showed the phase and EDS mapping results of the Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO

2 welding layer. The Ce enrichment was observed on the SiC particles inside the grains where a eutectic structure of Cr

7C

3 and γ-Fe was formed, as shown in

Figure 5c-3. However, the [O] high content was due to the high activity of CeO

2 adsorbed the enrichment of inclusions.

Figure 5.

Macrograph and micrograph and EDS analysis of the welding layer. (a) macrograph shape and sampling area of Fe55 welding layer; (b) macrograph and sampling area of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC welding layer; (c) macrograph and sampling area of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO2 welding layer; (a-1,a-2) micrograph of the interface of Fe55 welding layer; (b-1,b-2) micrograph of the interface of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC welding layer; (c-1,c-2) micrograph of the interface of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO2 welding layer; (a-3,a-4) Fe55 welding layer phase and EDS mapping; (b-3,b-4) Fe55+1.5wt% SiC welding layer phase and EDS mapping; (c-3,c-4) Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% welding layer phase and EDS mapping.

Figure 5.

Macrograph and micrograph and EDS analysis of the welding layer. (a) macrograph shape and sampling area of Fe55 welding layer; (b) macrograph and sampling area of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC welding layer; (c) macrograph and sampling area of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO2 welding layer; (a-1,a-2) micrograph of the interface of Fe55 welding layer; (b-1,b-2) micrograph of the interface of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC welding layer; (c-1,c-2) micrograph of the interface of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO2 welding layer; (a-3,a-4) Fe55 welding layer phase and EDS mapping; (b-3,b-4) Fe55+1.5wt% SiC welding layer phase and EDS mapping; (c-3,c-4) Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% welding layer phase and EDS mapping.

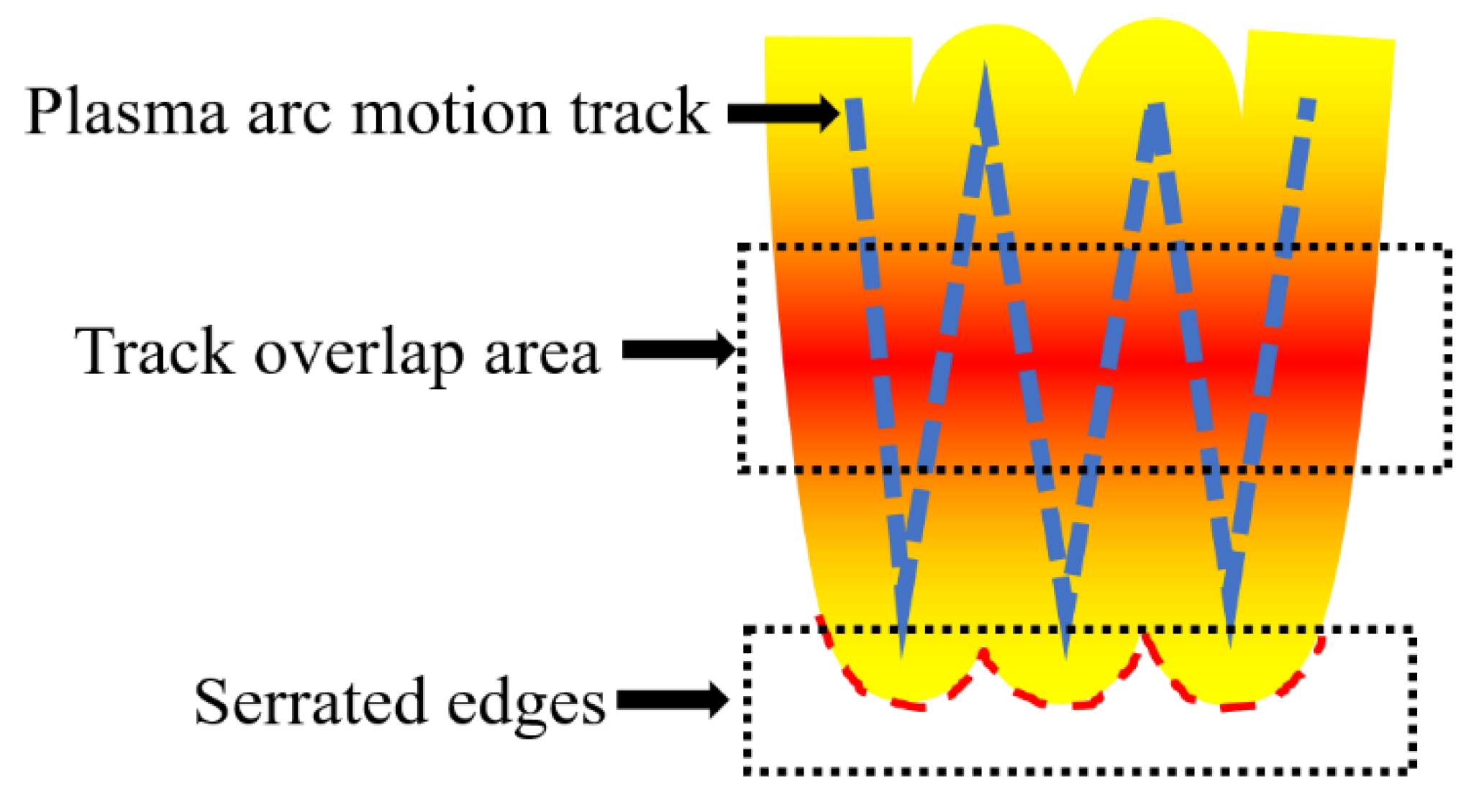

The schematic diagram of the welding layer was shown in

Figure 6. The sides of the weld layer formed a jagged edge (red dashed line). The plasma arc paths (blue dashed line) partially overlapped and formed an overlapping melt pool in the area where the paths overlapping. The overlapping melt pools had a higher temperature gradient[

18]. the molten steel in the area where the paths overlap expanded to each other and influenced by the viscosity of the molten steel. The molten steel with low viscosity expanded easily and the welding paths and jagged edges were not clearly visible. The molten steel with high viscosity was difficult to expand. Therefore, the welding paths and jagged edges were clearly visible.

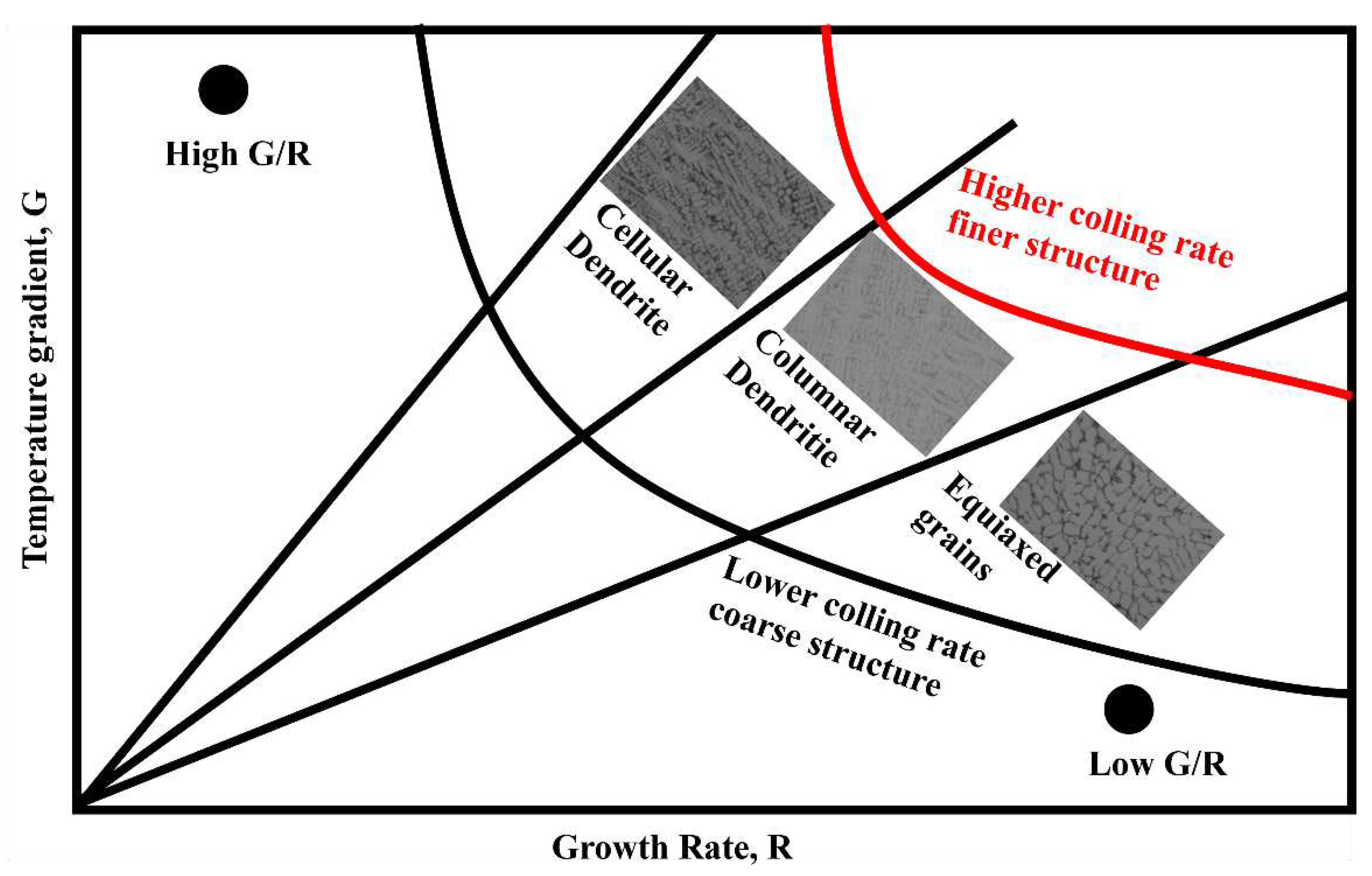

The changed in the solidification microstructure can be explained by

Figure 7 and equation (4). Where the liquid temperature gradient was

GL, solidification rate was

R, and undercooling

ΔTS were assumed to be constant due to the high temperature of the plasma arc with 3000 ℃. The addition of SiC or CeO

2 affected the flowability of molten steel at macro level. This leaded to a reduction in the liquid phase diffusion coefficient

DL of Cr and C and resulted in a decrease in the

G/R ratio as shown in

Figure 7. The Fe55 had a higher

G/R ratio and no SiC or CeO

2 to inhibit growth of dendritic. Resulting the microstructure was mainly composed of dendrites. The diffusion coefficient

DL of Cr and C elements in molten Fe55, Fe55+1.5%wt SiC and Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO

2 decreased with increase of SiC or CeO

2. Since Cr and C atoms were components of eutectic structure, the decrease in diffusion coefficient led to uniform distribution of Cr and C atoms. This provided rapid replenishment of atoms for grain boundary formation during the equiaxed crystallization process, which explained the differences in microstructures observed in different samples.

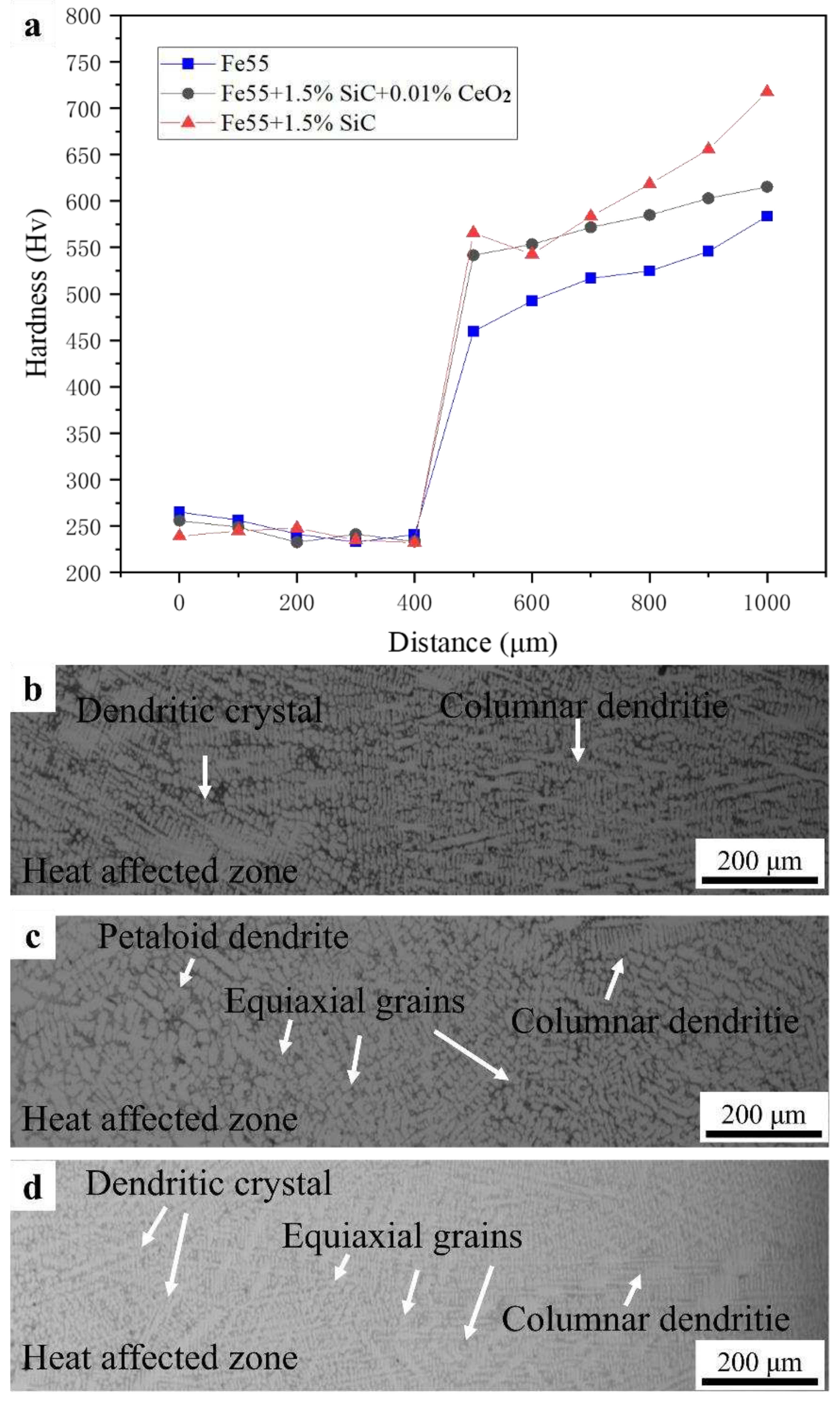

The γ-Fe was mainly strengthened by (Cr, Fe)

7C

3 carbides. Due to the relatively low density of some (Cr, Fe)

7C

3 near the fusion line in Fe55, there was a fluctuation in microhardness in

Figure 8a. The coarse grains were observed in the heat affected zone in

Figure 8b and the microstructure was mainly composed by dendrites. In Fe55+1.5wt% SiC, although the non-uniform distribution of SiC particles resulted in uneven distribution of (Cr,Fe)

7C

3. The grains of γ-Fe were refined with increasing content of nucleation sites and [Si, C] in

Figure 8d. The addition of CeO

2 caused the enhance phase be uniformly distributed in γ-Fe, which lead to the transitional states of microstructure in

Figure 8c.

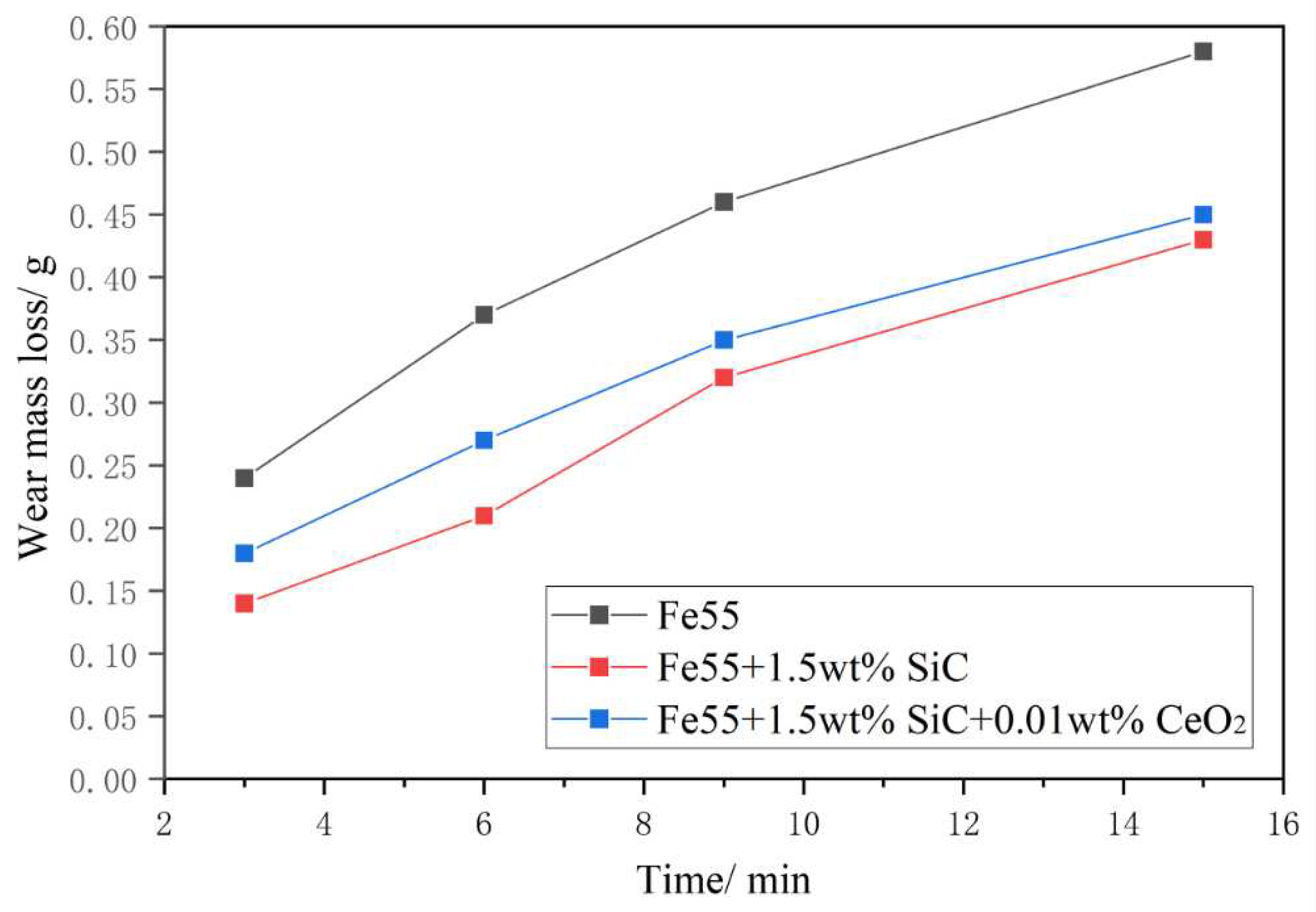

3.3. Wear Morphology

Figure 9 presented the test results of the wear mass loss of the sample after a 15 min test under a load of 20N. The change in wear mass loss exhibited a similar trend, with the slope initially increasing and then decreasing as the wear time was prolonged. The wear mass loss of Fe55 was significantly higher than that of other samples. The sample with SiC addition exhibited lowest mass loss. This was because SiC floated to the surface of the solder layer during the spraying process and aggregated, resulting in an increase in surface hardness and enhanced wear resistance. As the wear progressed, the contact area increased, leading to a decrease in the wear rate at 9 minutes. However, at a wear time of 6 minutes, there was a slight increase in the wear rate. The wear mass loss of the Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO2 sample remained stable, but due to its lower surface hardness compared to the sample with only SiC added, the wear mass loss of this sample was higher.

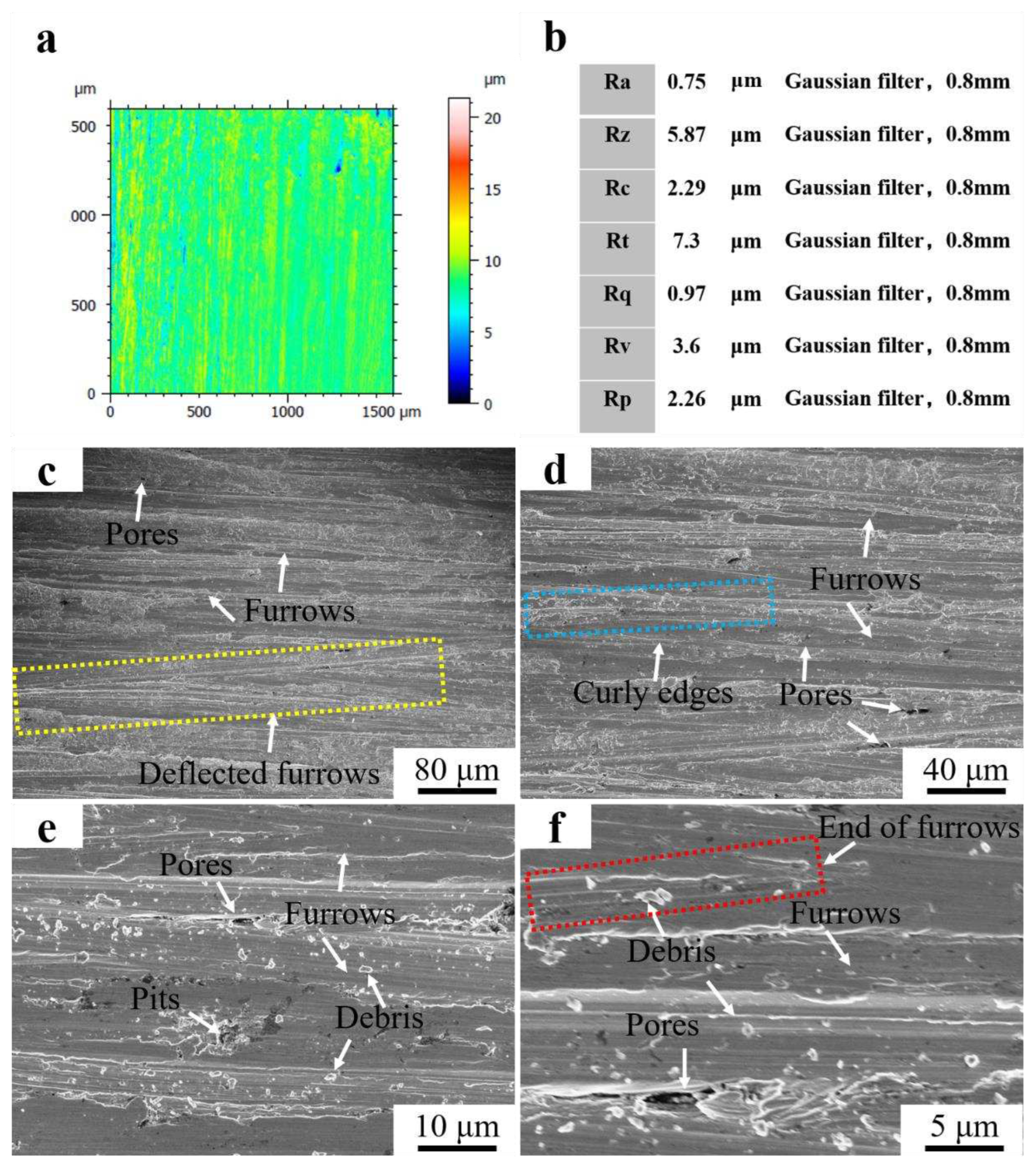

Figure 10a showed the 3D morphology of the surface of Fe55 after wet friction test. The depth of the furrows on the friction surface was marked by color with a not uniform distribution. The blue area indicated deep furrows as well as holes. The yellow and red areas indicated light furrows. The structure of the blue area was mainly γ-Fe with low density of Cr

7C

3 enhancement, which was easy to be worn. Defects such as inclusions or porosity existed in these areas, which occurred fatigue wear and formation of spalling pits. The Cr

7C

3 agglomerated in the red region and increased the hardness. Therefore, the furrows were shallow. According to ISO4287 standard, the Ra was 0.75 μm and Rz was 5.87 μm at a Gaussian filter of 0.8 mm. The abrasion roughness is between N5 and N6 as shown in

Figure 10b.

Figure 10(c-f) showed the worn surface micrograph of Fe55 after wet friction test. Furrows and holes were observed in

Figure 10c. However, the furrows were deflected (yellow dashed line), which was a result of the movement of abrasive SiC was blocked by the Cr

7C

3 hard phase. In the case of abrasive wear, the particle hardness was higher than γ-Fe. Then the abrasive SiC is deflected toward the γ-Fe region with low density of Cr

7C

3. The edges of the furrows were clearly curled and demonstrated a cut characteristic (blue dashed line). This was formed by the abrasive SiC during the cutting of the low hardness γ-Fe. In

Figure 10e, the hidden porosity was exposed during the friction process since the existence of casting defects such as hidden porosity. The fatigue wear on the friction surface resulted in spalling pits. In addition, there were a large number of abrasive debris on the surface, which were hard three-body embedded in soft γ-Fe during movement and could not be washed away. Levy at el examined that when the particles were strong enough not to break up on impacting, the erosion rate became constant[

19]. It explains the reason of abrasive SiC embedded in soft γ-Fe. The size of the abrasive debris had a significant difference. Part of the abrasive debris were newly generated, which indicated that not only abrasive wear but also three-body wear had occurred during wet friction[

20]. The end point of partial furrows was visible (the red dashed line) in

Figure 10f, which was the result of the abrasive SiC be blocked by the Cr

7C

3 hard phase and unable to deflect to the nearby area.

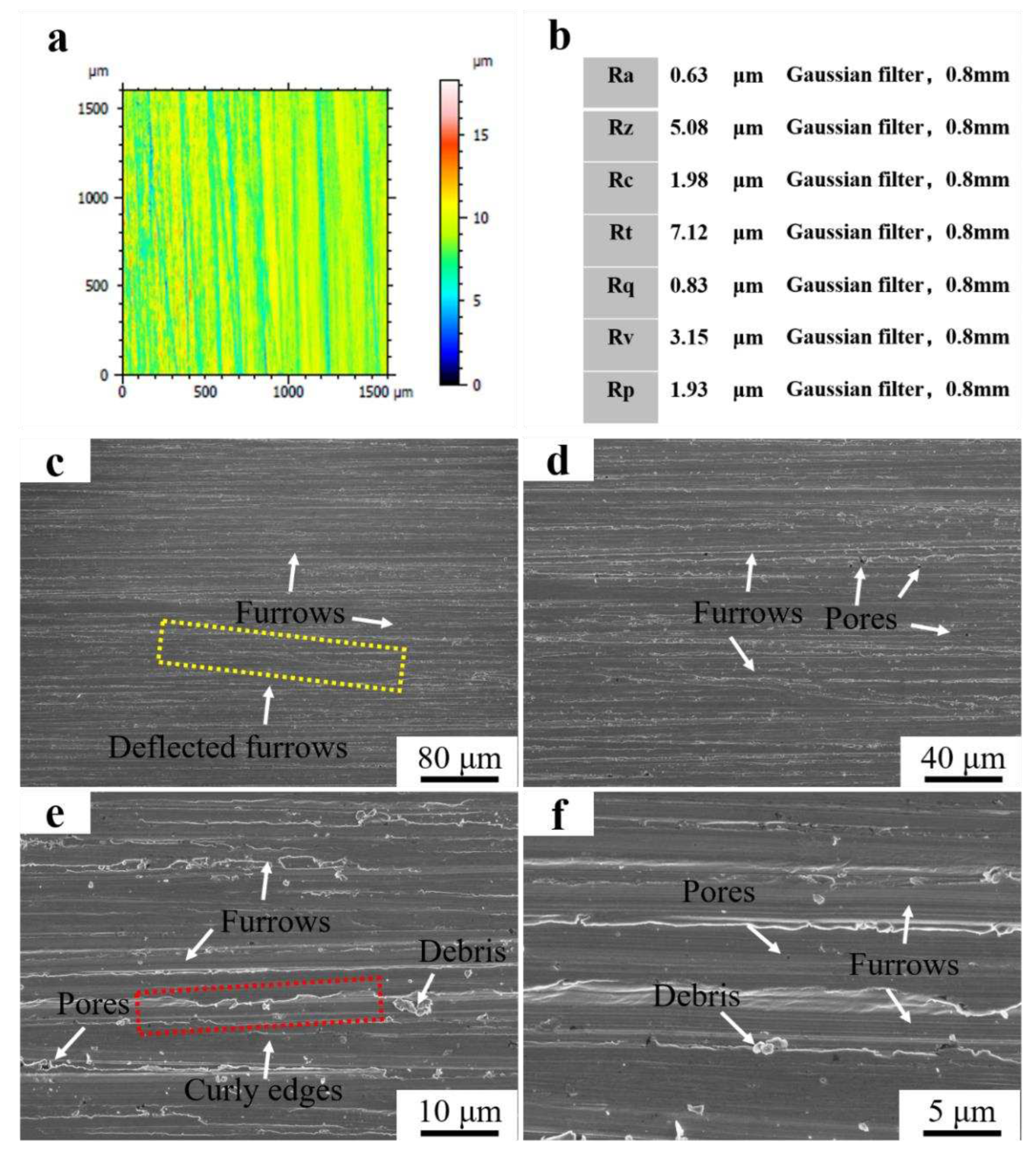

Figure 11a showed 3D micrograph of Fe55+1.5 wt% SiC after wet friction test. The color distribution of the worn surface was more uniform after the SiC addition. The blue area represented the deep furrows and the microstructure was mainly γ-Fe with low density of Cr

7C

3. The yellow and red areas represented the lighter furrows with Cr

7C

3 and SiC. The SiC float up to the surface and agglomerated. [C] generated by decomposition of SiC promotes the growth of Cr

7C

3 and increased the surface hardness. According to ISO4287 standard, Ra was 0.63 μm and Rz was 5.08 μm at a Gaussian filter of 0.8 mm. Therefore, the roughness was between N5 and N6 as shown in

Figure 11b.

Figure 11 (c-f) showed the surface micrograph of Fe55+1.5 wt% SiC after wet friction test. The dense furrows were observed in

Figure 11c, indicating uniformly wear was promoted on the worn surface. However, there were still deflected furrows on the sample surface. The abrasive SiC was blocked by the Cr

7C

3 or SiC in γ-Fe and deflected toward the low hardness region. In

Figure 11d, porosity was observed, as Ar gas agitation led to the agglomeration of bubbles on the molten steel surface. Partially agglomerated SiC prevented the bubbles from breaking and lead to casting defects. In

Figure 11e, significant curly edges on furrows were consistent with the cause of curly edges formation in the Fe55 sample. The number of debris was significantly reduced compared to the sample without the SiC addition in

Figure 10e. The abrasive could not embed in γ-Fe and reduced the occurrence of three-body wear for the addition of SiC increased surface hardness. Babu et al. indicated the erosion mechanism changes depending upon the erodent type [

21]. As the SiC addition increased the surface hardness, the three-body wear was reduced. The uniform size of the debris was visible in

Figure 11f, indicating the SiC addition contributed to the wear uniformity.

Figure 12a showed the 3D morphology of the surface after the friction test of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO

2. The depth of farrows on the wear surface was marked by color. The color distribution of the wear surface was the most uniform among all samples with the co-addition of SiC and CeO

2. The hardness of the red area is higher where SiC or Cr

7C

3 aggregation. There were no deep farrows on the surface of the samples. CeO

2 addition promoted the diffuse distribution of SiC and Cr

7C

3 which bear the friction load uniformly. According to ISO4287 standard, Ra was 0.28 μm and Rz was 2.03 μm at a Gaussian filter of 0.8 mm. The abrasion roughness was between N4 and N5, as shown in

Figure 12b.

Figure 12 (c-f) showed the surface morphology of Fe55+1.5 wt%SiC+0.01wt%CeO

2 after wet friction test. In

Figure 12c, dense furrows on the surface indicated that the samples were worn uniformly. In

Figure 12d, number of holes was less than other samples in

Figure 10d and

Figure 12d. It was difficult for the stirring effect of Ar gas to form bubbles on the surface of the welding layer since the viscosity of the molten steel increased by CeO

2, which reduced the generation of defects. The furrows showed obvious curled edges in

Figure 12e. The uniform size of debris embedded in the surface were found. Therefore, the wear mechanism was abrasive wear and three-body wear[

22].

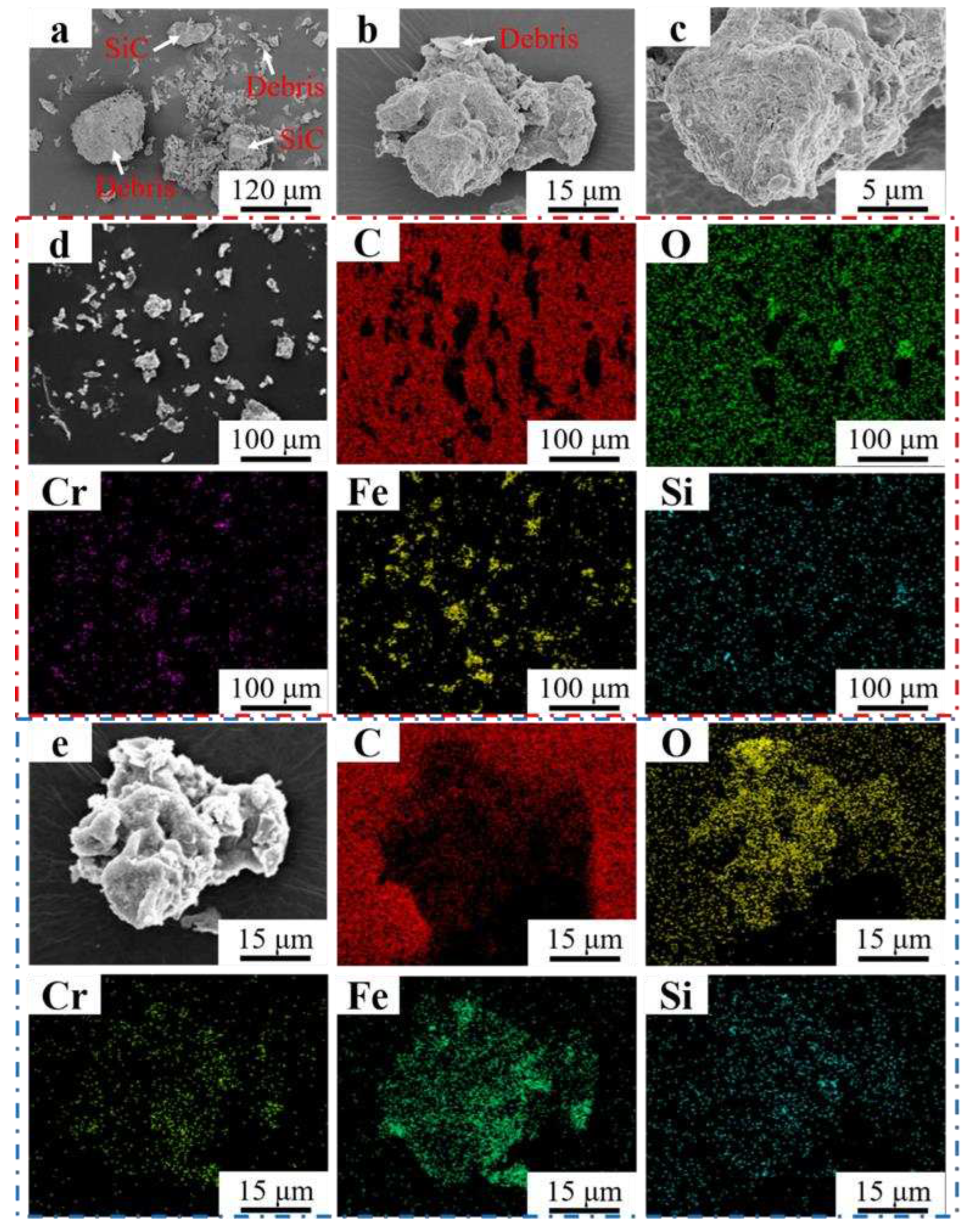

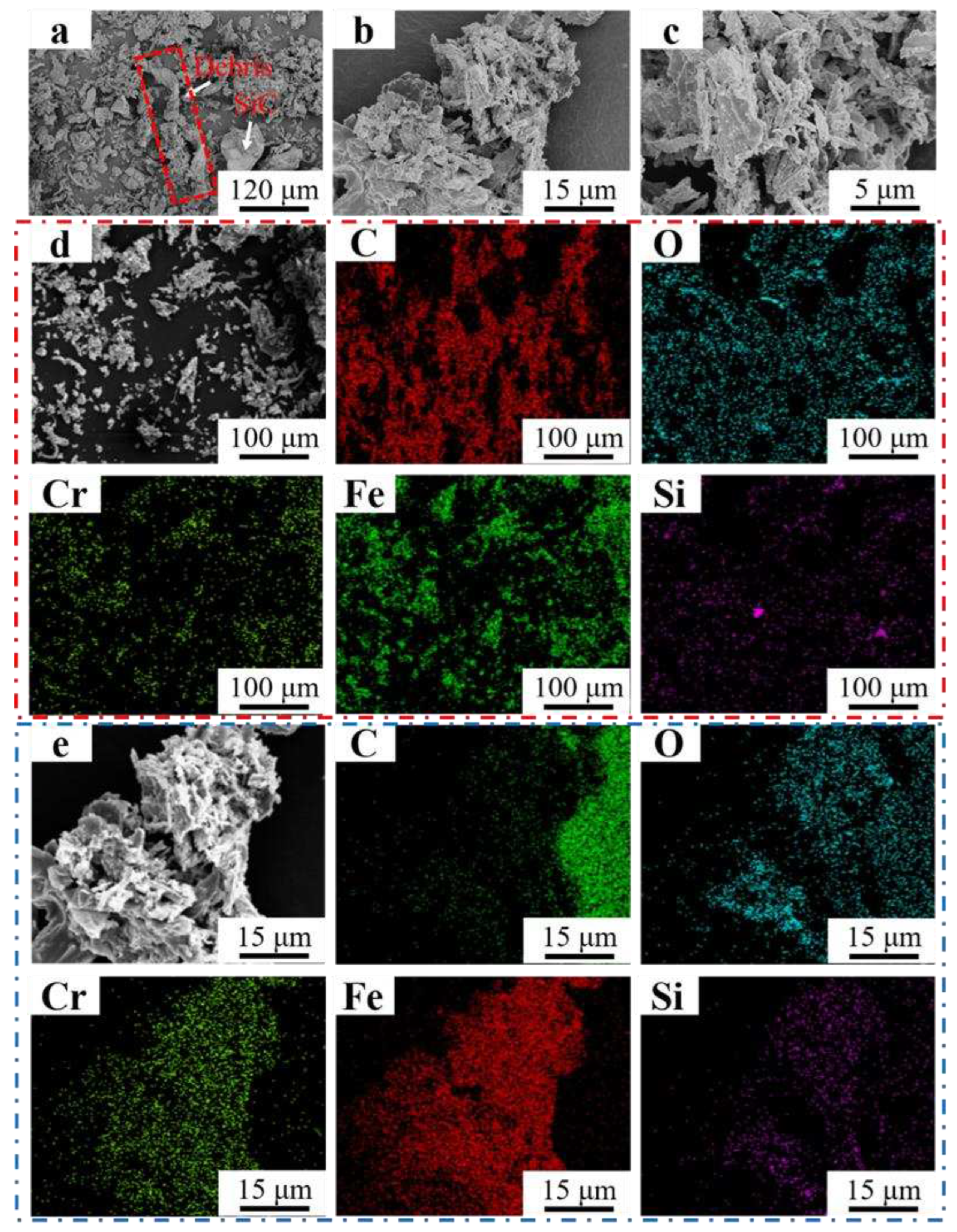

Figure 13 (a-c) showed the morphology of the abrasive debris of Fe55 in different magnification. Different sizes of the abrasive debris were found in

Figure 13a. The big debris was formed by the agglomeration of small debris. Meanwhile, the rest of debris was lamellar structure, indicating that the abrasive debris was stripped from the worn surface by microcutting. The unbroken abrasive SiC can be observed. The big debris were formed by the lamellar debris and small abrasive debris agglomeration in

Figure 13b. The EDS mapping of

Figure 13b were shown in

Figure 13e. The results indicated that the main component of big debris was Fe

2O

3. The Fe element reacted with O element in the water to form fluffy Fe

2O

3 and adsorbed small debris to form big debris. In

Figure 13d, the main components of debris were Fe and Cr. Due to the small size of the debris which can be easily oxidized. Therefore, the O, Fe and Cr elements enrichment areas overlapped. The SiO

2 in the welding layer was stripped off resulted in Si enrichment was observed on the debris surface. The C and Cr enrichment areas overlapped in

Figure 13e, indicating Cr

7C

3 was also worn and formed small debris, which explained the occurrence of three-body wear.

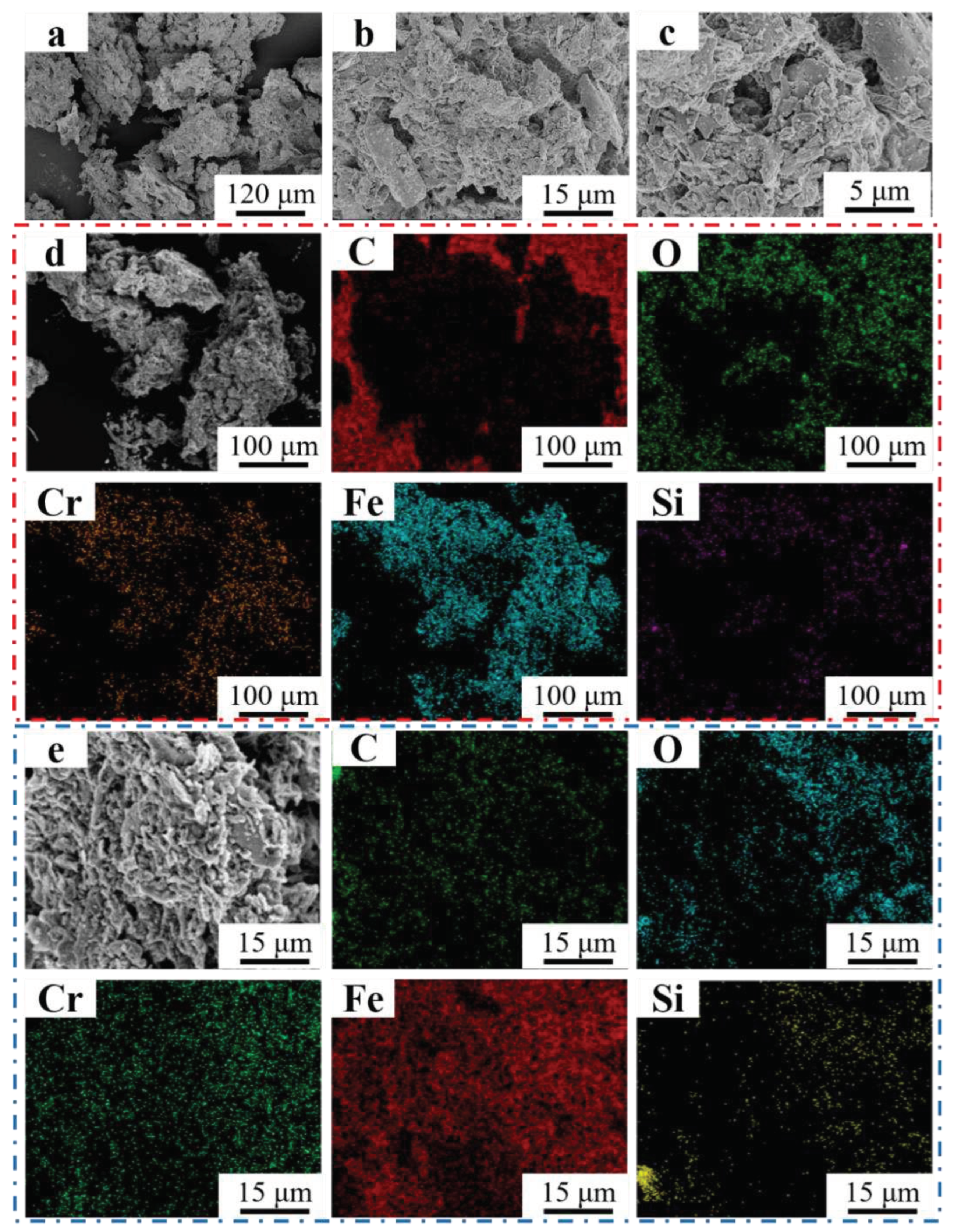

Figure 14 (a-c) showed the morphology of debris of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC in different magnification. Strip-shaped debris with length of 250~300 μm marked by the red dashed line showed obvious chipping feature in

Figure 14a, which suggested that abrasive wear was the main mechanism. SiC with size of 20~30 μm were also observed, which were produced from the collision and fragmentation between SiC abrasives and hard phases. Due to their small size and high surface energy, agglomeration of debris was observed in

Figure 14 (b, c). EDS mapping in

Figure 14d indicated the Si enrichment areas correspond to the fragmented SiC particles. Strip-shaped debris mainly consist of Fe and Cr. The region enriched with Cr overlapped with C, indicating that Cr

7C

3 was peeled off from welding layer.

Figure 14e shows the EDS mapping results of

Figure 14b where overlapping areas of Si and C enrichment were observed. The SiC had not been fully decomposed and still bear the load. However, the increase in Si content reduced the toughness of welding layer, which explained the reason for strip-shaped debris crack observed in

Figure 14a.

Figure 15 showed the morphology of debris of Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO

2 in different magnification. Small debris with a flaky shape can be observed to agglomerate into larger debris and showed chipping characteristics in

Figure 15a. The flaky shape debris with a uniform size of 0.5~3 μm in

Figure 15(b-c) were chipped uniformly by abrasives. In

Figure 15d, the flaky shape debris is mainly composed of Cr, Fe, Si, and O elements. However, Ce element was not detected due to low content. As the microstructure was significantly improved resulting in uniformly wear sealing surfaces by co-addition of CeO

2 and SiC particles.

3.4. wear Mechanism

The analysis of the SEM microstructure results in Fig. 10-15 indicated that the wear mechanism of the friction system was microcutting and micoploughing. During microcutting, SiC abrasives first formed furrows on the contact surface, causing hard Cr

7C

3 and soft γ-Fe to peel off from the contact surface and form debris. The amount of debris increased with test time. Although water served as the boundary lubricant for the contact surface, the debris inevitably embedded into the contact surface or escape from the real contact areas by the gaps provided by the topographies of the worn surfaces within the contact zone[

23]. This proved that all samples experienced three-body wear.

It is worth noting that, due to the high toughness of γ-Fe, micoploughing can dissipate frictional energy into microplastic deformation. Since water served as the boundary lubricant for the contact surface, some less sharp abrasives were not enough to form microcutting on the contact surface. Instead, they lost their kinetic energy through micoploughing, which dissipated the frictional energy into microplastic deformation and caused curly edges of furrows, as observed in

Figure 10d,e, and

Figure 12e. The region where micoploughing occurred underwent microplastic deformation in γ-Fe, but excessive microplastic deformation was inhibited by Cr

7C

3, so these γ-Fe did not peel off from the contact surface. However, literature suggests that microplastic deformation caused by micoploughing leads to plastic fatigue wear [

24], resulting in spalling pits caused by plastic fatigue wear in all samples.

When wear began, surface hardness played a key role, with higher hardness indicating stronger wear resistance. Increasing the duration of wear resulted in microplastic deformation. However, when the hardness of the contact surface was excessively high and the toughness was too low, micro-cracks would form and propagate. Costin et al. indicated that the hardness and toughness of wear-resistant materials should be matched[

25].

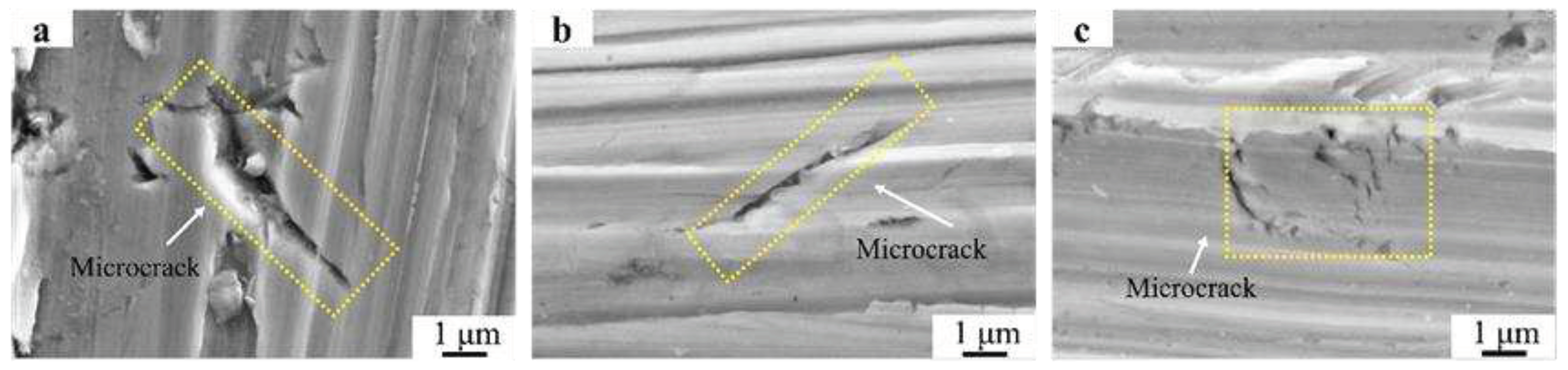

Due to the predominance of dendritic microstructure and coarse grain size in the Fe55 welding layer, its hardness and toughness were the lowest among all the samples. Once microcracks formed, their propagation could not be inhibited.

Figure 16a showed the microcrack generated after the friction test on Fe55, with a length of 10 μm, and no evidence of microcrack termination was observed. This indicated that Cr

7C

3 did not inhibit the microplastic deformation occurring in γ-Fe. The microcracks expanded with increasing of friction time and eventually led to spalling, which explained why the wear mass loss of Fe55 was the highest among all the samples.

When SiC was added to the welding layer, due to its lower density compared to the molten steel, SiC floated to the surface of the molten steel during the melting process. SiC decomposed into Si and C, increasing the number of interstitial solute atoms in the surface of welding layer and enhancing the hardness of γ-Fe. The high hardness prevented the embedding of abrasive particles but could potentially lead to a decrease in toughness. Since hardness determined the wear mass loss in the early stage of friction, the Fe55+1.5wt%SiC sample with the highest surface hardness exhibited the lowest wear loss initially.

However, the results in

Figure 5b-2 indicated that the distribution of SiC was non-uniform. This resulted in regions with SiC agglomeration having higher microhardness, while areas without SiC had lower microhardness. The uneven hardness distribution made it easier for microcracks to propagate in the SiC agglomeration regions, with a length of 7 μm in

Figure 16b. However, the regions without SiC experienced deep plowing grooves. Therefore, when the friction time reached 15 minutes, the wear mass loss of the Fe55+SiC sample was already approaching that the Fe55+1.5wt% SiC+0.01wt% CeO

2 sample with lower surface hardness.

After co-added of SiC and CeO

2, CeO

2 decomposed into Ce and O during the spraying process. Ce hindered the agglomeration of SiC particles and the diffusion of C and Cr atoms. Resulting in uniform distribution of C and Si in the molten pool. As a result, the microstructure and hardness uniformity were improved, thereby enhancing resistance to microcutting and plastic fatigue wear. During microcutting, the uniformly distributed Cr

7C

3 hard phase prevented excessive cutting of γ-Fe by abrasive particles, reduced the microcutting volume and prevented the generation of more abrasive particles. In

Figure 12f, no significant embedding of abrasive particles as observed in

Figure 10f.

Figure 8c demonstrated that the microstructure and hardness of the welding layer only varied with temperature gradients. After the high-hardness region on the surface was worn, other regions could still maintain their hardness and toughness, avoiding excessive wear losses. While micoploughing happened, the increased toughness reduced fatigue wear caused by microplastic deformation, and the uniformly distributed Cr

7C

3 hard phase prevented excessive microplastic deformation. The microcrack shown in

Figure 16c with length of 3 μm and exhibit a distinct characteristic of being inhibited.