1. Introduction

Repeated exposure to cocaine and other drugs of abuse enhances behavioral and neurochemical responses upon successive experience [

1]. This process, termed sensitization, is often measured using locomotor activity. A single cocaine injection reliably augments locomotor activity, and multiple cocaine injections progressively facilitate that response producing an effect that can be quite enduring [

2,

3]. Sensitization is studied in animal models as a simple phenomenon thought to have predictive relevance for some aspects of addiction, including drug craving and relapse [

1]. Such repeated cocaine pre-exposure facilitates later acquisition of cocaine self-administration, but the development of locomotor sensitization is not necessarily required for the expression of a sensitized response to the rewarding effects of cocaine [

4,

5]. The reverse is also shown with rats given extended access to cocaine self-administration demonstrating a dose-dependent increase in sensitivity to the psychomotor activating effects of cocaine compared to their short access counterparts [

6].Cocaine sensitization can also augment the motivational influence of a reward predictive cue for a non-drug reward. Importantly, the occurrence of behavioral and physiological sensitization has similarly been reported in humans [

7].

Behavioral sensitization is driven by neural plasticity measured in multiple nodes of the corticostriatal circuitry including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), dorsal striatum (dStr), and nucleus accumbens (NAc) [

1]. Cocaine sensitization is associated with increased extracellular dopamine release in the NAc upon a subsequent cocaine challenge [

8,

9]. Cocaine challenge following sensitization likewise increases extracellular glutamate in the dStr and NAc [

10,

11,

12] which includes enhanced glutamatergic input from the PFC [

13]. The molecular mechanisms underlying this enhancement of neurotransmission remain incompletely understood, though numerous cellular adaptations contributing to the expression of behavioral sensitization have been identified [

14,

15]. For example, mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling is required for the expression of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization through a mechanism that involves trafficking of GluA2 AMPA receptors in the NAc [

14]. mTOR is a tyrosine protein kinase that regulates neurodevelopment, synaptic plasticity and memory [

16]. Interestingly, mTOR signaling shows bidirectional regulation with that of another fundamental cellular energy regulator, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK directly and indirectly inhibits mTORC1 activity [

17,

18], and mTORC1 negatively regulates AMPK in a regulatory feedback loop [

19]. AMPK signaling is thus emerging as an important counterbalance to mTOR worthy of additional study.

AMPK is a heterotrimeric protein consisting of beta (β1 or β2), gamma (γ1, γ2, or γ3), and catalytic alpha (α1 or α2) subunits, the latter of which when phosphorylated significantly increases enzymatic activity [

20]. AMPK is critical for maintaining cellular energy homeostasis in the periphery and central nervous system under normal physiological conditions [

20,

21]. AMPK is also an emergent therapeutic target for numerous chronic diseases including neurodegeneration and substance use disorders [

22,

23]. In rats, acute cocaine injections increased phosphorylated AMPK (pAMPK) in the PFC but decreased pAMPK in the dStr [

24]. Chronic cocaine injections producing behavioral sensitization amplified this effect [

24]. In contrast, pAMPK was reduced in the NAc core following cocaine self-administration and extinction [

25] and reduced in the NAc shell following abstinence from cocaine self-administration [

26]. Moreover, manipulation of AMPK activity in the NAc core or shell reduced cue-induced cocaine seeking and diminished cocaine reinforcement, respectively [

25,

26]. These data overall demonstrate a role for AMPK in regulating cocaine reward.

AMPK is indirectly activated by the type II diabetes drug metformin which promotes phosphorylation of a regulatory site on its alpha catalytic subunit [

27,

28]. Recent studies have shown that metformin can reduce cocaine seeking in rats. Introducing metformin to the NAc core decreased cue-induced cocaine seeking in male and female rats following self-administration and extinction [

29] in line with the prior research involving direct manipulation of AMPK with viral or other pharmacological tools [

25,

26]. Moreover, preclinical literature indicates that metformin may reduce symptoms of withdrawal for another psychostimulant drug, nicotine [

30]. Furthermore, human and animal studies suggest that metformin mitigates some of the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk associated with nicotine exposure [

31,

32]. There is increasing excitement related to repurposing metformin to address cocaine or other substance use disorders given its classification as both safe and inexpensive [

33,

34].

This study aimed to determine the impact of cocaine sensitization on total and pAMPK protein levels in synaptosomal and cytosolic protein fractions in the mPFC, dStr, and NAc of rats. We examined AMPK levels in separate functional subcellular domains given that cocaine sensitization is known to impact trafficking of other proteins involved in sensitization including AMPARs [

14]; furthermore, AMPK activation can increase AMPAR expression [

35]. Most importantly, kinase activity of AMPK in cortical tissue is enriched in both nuclear and synaptosomal fractions compared to some kinases which show preferential activity in one or the other domain [

36]. Here we present evidence of specific changes in subcellular AMPK activity in relation to acute and repeated, sensitizing cocaine injections. We further demonstrate the suppressive effect of metformin pretreatment on the acquisition of cocaine locomotor sensitization and related changes in AMPK expression. Overall, these studies add to our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying psychomotor sensitization to cocaine and provide support for metformin as an intervention to suppress this form of plasticity.

3. Discussion

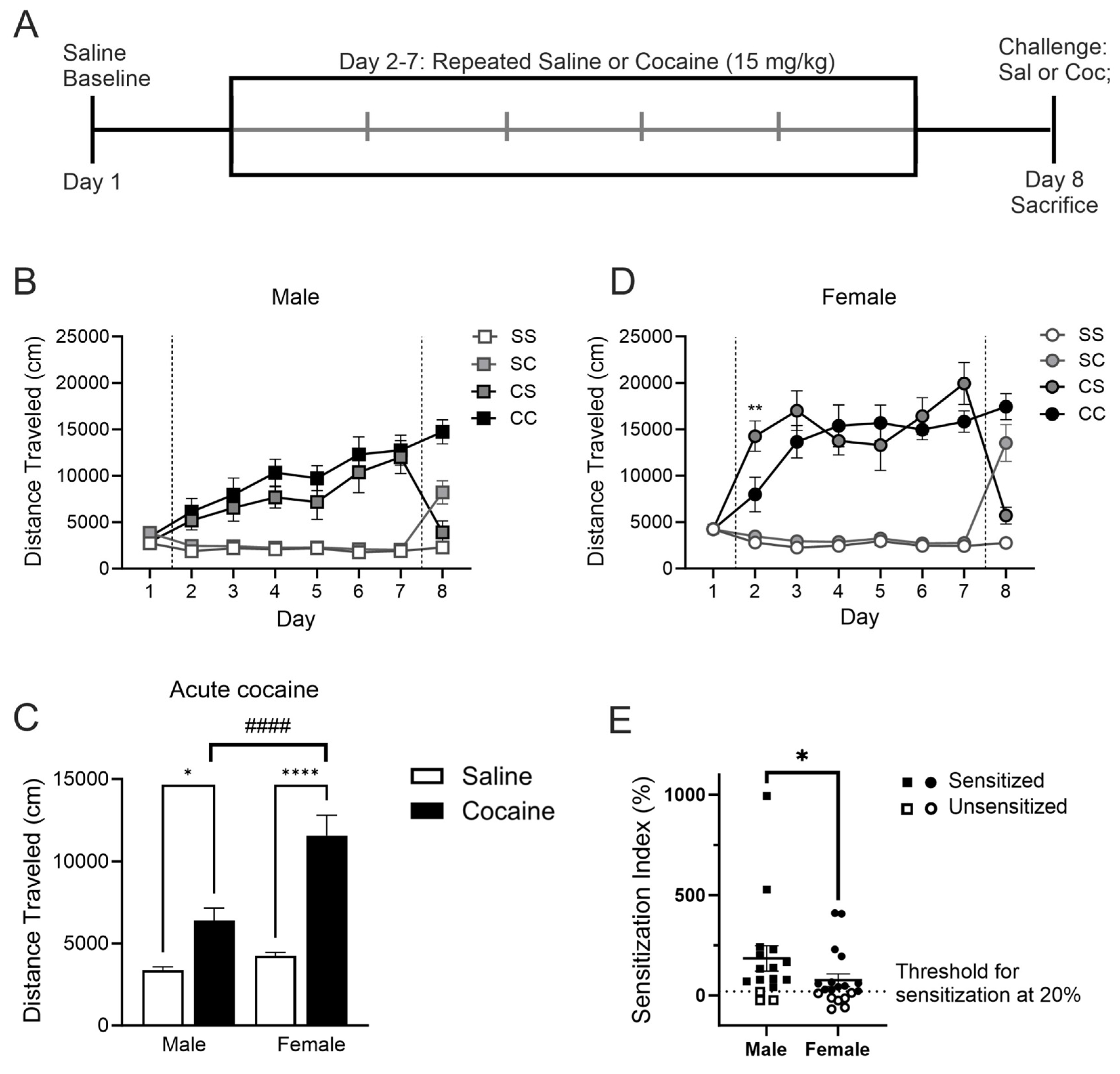

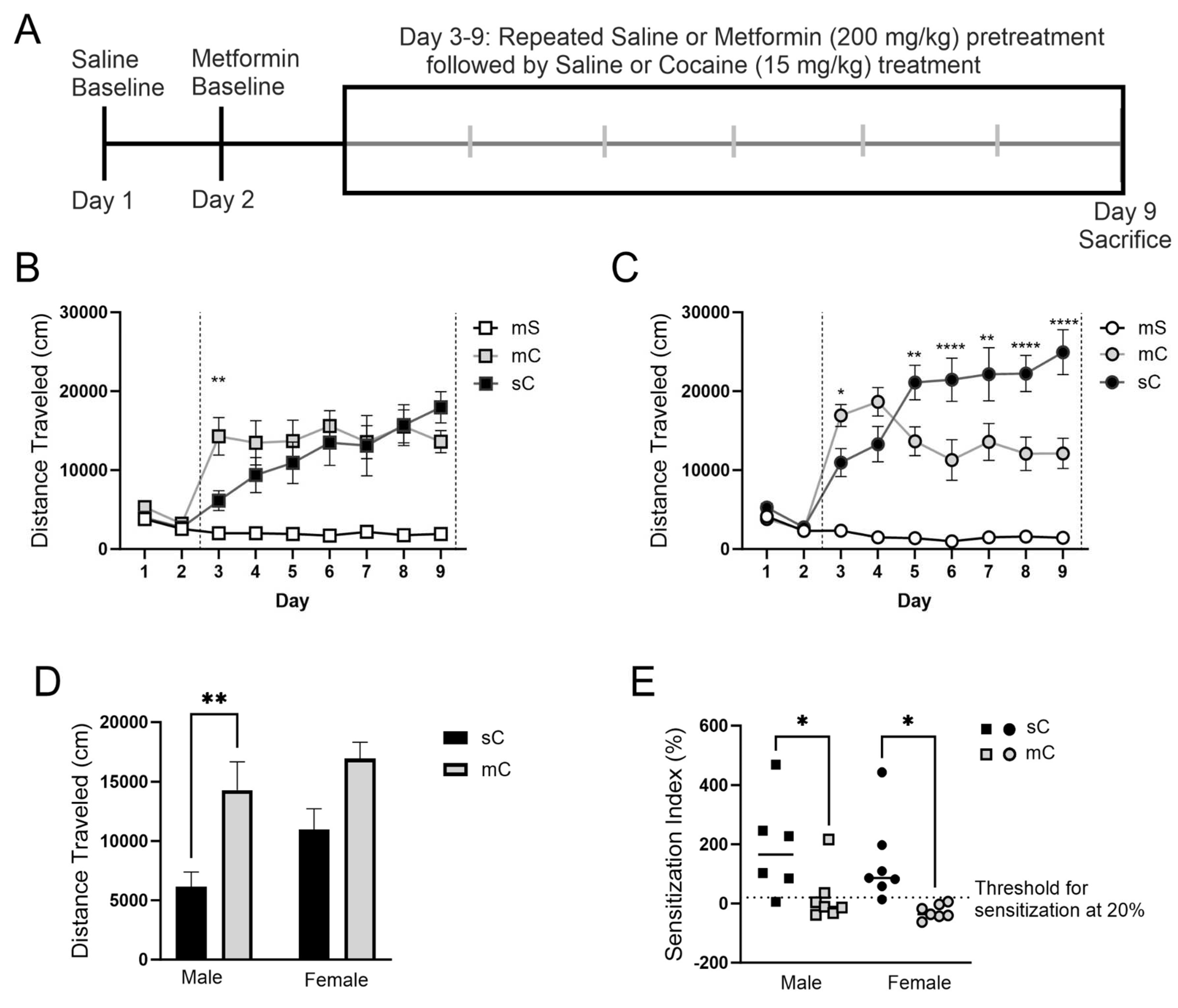

In this study, we used cocaine locomotor sensitization to understand the role of AMPK in mediating the effects of cocaine. The first experiment provided confirmatory results relating to sex differences in the locomotor response to cocaine [

37]. We found that while the acute locomotor response to cocaine was larger in female rats, repeated cocaine injections tended to produce greater psychomotor sensitization in male rats. We examined levels of phosphorylated and total AMPK in cytosolic and synaptosomal fractions of lysates from multiple brain regions in the corticostriatal circuit. Analysis occurred across four treatment groups (SS, SC, CS, CC) to probe acute and repeated cocaine effects. The most prominently observed treatment effects were associated with cocaine challenge regardless of repeated treatment with saline or cocaine. Most frequently, we detected differences post hoc between the repeated cocaine treated groups CS and CC. In the second experiment, we tested the effects of metformin, an indirect AMPK activator, on cocaine sensitization. We identified dual effects of metformin with augmentation of the acute effects of cocaine but a disruption in sensitization. Contrary to our predictions, we observed a decrease rather than an increase in pAMPK in the NAcS associated with metformin pretreatment prior to cocaine. Despite large behavioral effects, overall treatment group effects were less robust, in some cases due to sex differences or sex by treatment interactions. The lack of consistent regulation of AMPK may suggest a role for an alternative mediator of the effects of metformin.

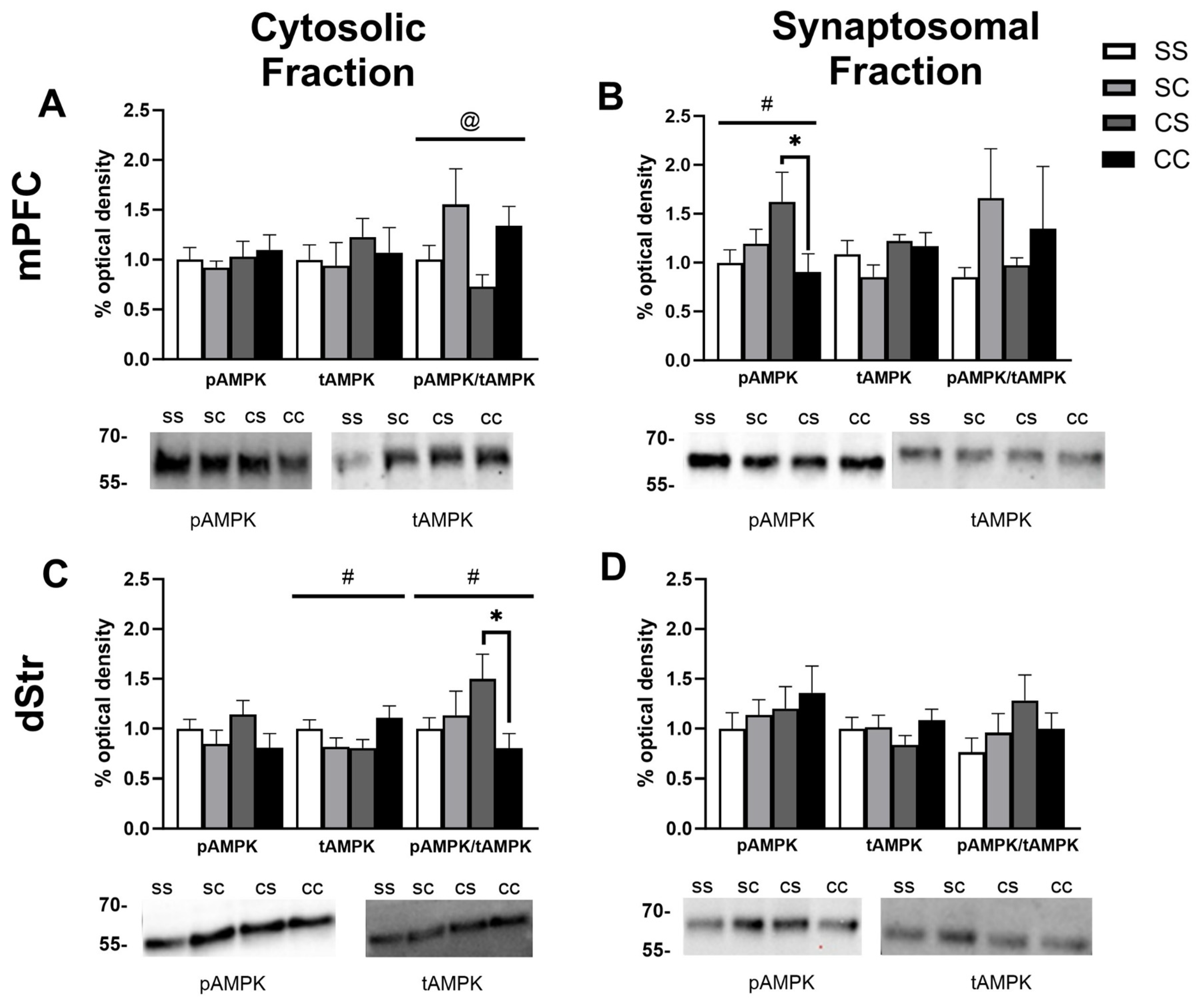

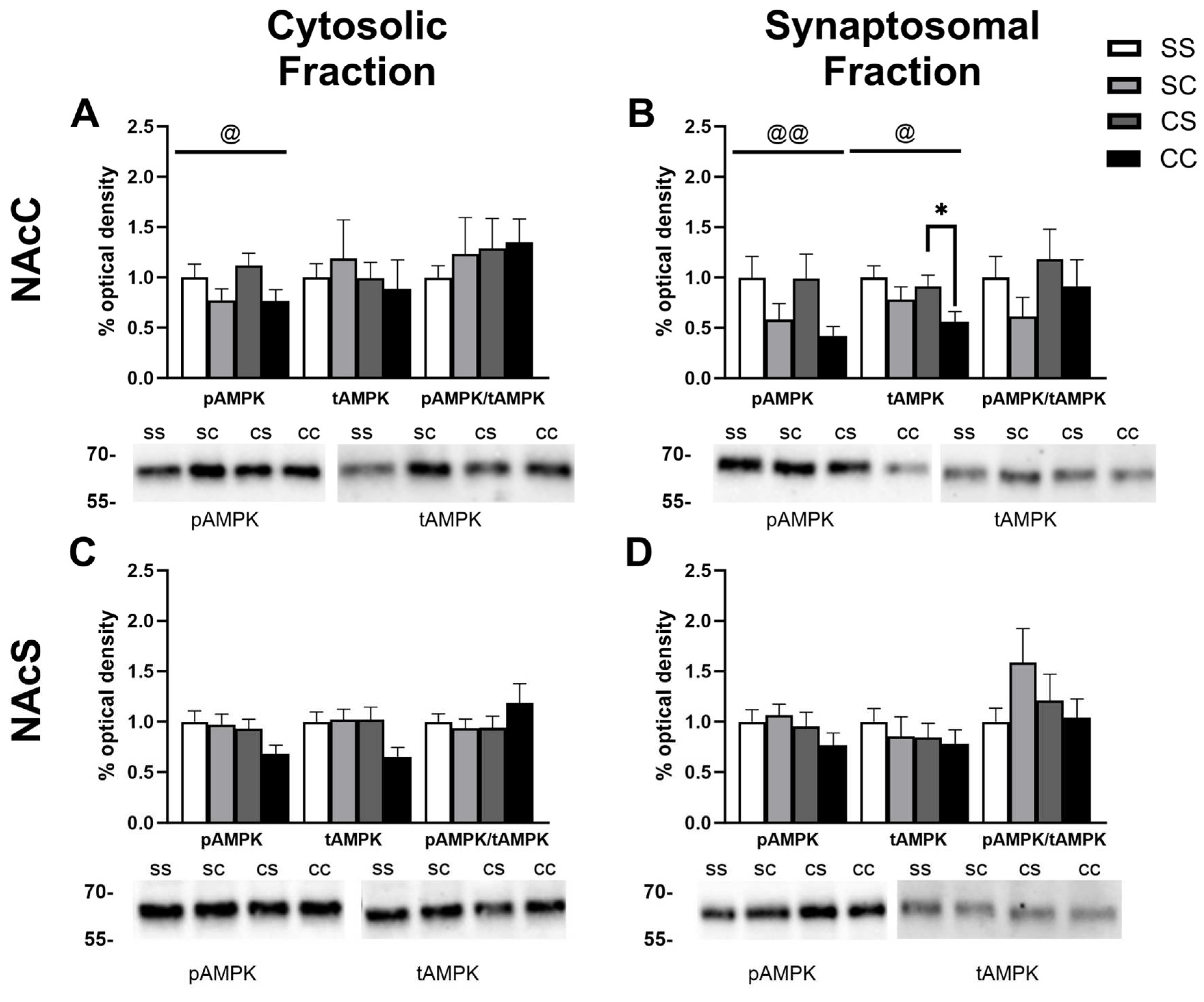

AMPK is mostly cytosolic but it can also localize to cellular membranes, and dynamic protein interactions at or near synapses are known to be important for the plasticity associated with behavioral sensitization. Cocaine sensitization had significant impacts on total protein and phosphorylation levels of AMPK in various regions of the corticostriatal reward circuit. We predicted that cocaine sensitization would be associated with increased pAMPK in the mPFC and decreased pAMPK in the dorsal and ventral striatum (dStr, NAcC, and NAcS). This prediction was based on prior studies that had examined AMPK levels in whole cell lysates and observed dose-dependent increases or decreases in pAMPK/tAMPK expression in the mPFC and dStr, respectively [

24]. Our work expands upon that study by examining additional brain regions, separately querying the cytosolic and synaptosomal fractions, and including both male and female rats. Moreover, we also examined levels of total and phosphorylated AMPK separately given that intracellular trafficking could impact both independently. In our studies, cocaine challenge was associated with an increase in pAMPK/tAMPK in the cytosol of the mPFC. In the synaptosome, there was an interaction between acute and repeated treatment effects for pAMPK such that the largest difference emerged between the CC and CS groups. This overall result is only somewhat consistent with the prior study demonstrating increased pAMPK/tAMPK in whole cell lysates from mPFC following acute and repeated cocaine treatment in male rats [

24]. In the dStr our results in cytosolic and synaptosomal fractions were not consistent with a dose-dependent decrease in pAMPK/tAMPK associated with cocaine treatment as found by Xu and Kang. In the NAcC, cocaine challenge was associated with decreased pAMPK in the cytosol and synaptosome and decreased tAMPK in the synaptosome. No changes were observed in the NAcS. There could be a number of explanations for the disparate findings between these studies including differences in dissections, the inclusion of female rats, and of course, the examination of subcellular fractions compared to whole cell lysates. Unfortunately, our ability to make more direct comparisons are limited because we do not have total protein fractions from our experimental animals.

Spatially and temporally dynamic AMPK activity allows for distinct signaling in subcellular compartments for precise control of cellular functions [

38]. We observed differences in pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in cytosolic and synaptosomal subcellular compartments of different brain regions. AMPK also shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm with AMPK ɑ2 containing both a nuclear localization signal sequence (NLS) and a nuclear export signal sequence (NES) [

39], although in this study we did not examine protein changes in the nuclear fraction. A number of stimuli are known to impact AMPK nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling including starvation, heat shock, oxidant stress, and circadian signals, but it is less well-established what regulates the localization of AMPK to the synaptosome [

36]. It has been shown that, at least in cortical tissues, kinase activity of AMPK shows enrichment in both nuclear and synaptosomal fractions. The detection of significant differences in tAMPK in our experiments suggests that we are capturing some level of AMPK trafficking associated with cocaine treatment. This dynamic trafficking may also contribute to why we failed to replicate the dose-dependent effects on pAMPK previously observed with whole cell lysates.

The most intriguing result of this study was the finding that metformin pretreatment 30 minutes prior to each cocaine injection prevented the induction of cocaine sensitization. While their overall locomotion levels were still high compared to rats that had only received metformin+saline, the increase in locomotion across days that would indicate sensitization was absent. In female rats, there was a trend of locomotion even decreasing after the first few exposures to cocaine. Metformin on its own did not seem to have an impact on activity in line with previous studies [

40], although metformin treatment can improve locomotor coordination and balance in control mice and in the context of spinal cord injury or neurodegeneration [

41,

42,

43]. Surprisingly, metformin pretreatment increased the acute locomotor response to cocaine. We are conducting studies to determine if there are any differences in the impact of acute and prolonged metformin and cocaine exposure on the expression of AMPK or other molecular markers associated with cocaine-induced plasticity. It is worth noting that all rats had prior exposure to metformin due to their day 2 baseline injection. However, based on the subsequent observed behavior, we have no reason to believe that this acute metformin injection had any long-term impact on any of the treatment groups.

Protein analysis revealed few differences between treatment groups in the metformin experiment with none in the mPFC and dStr. This may partially be explained due to the absence of a short-term withdrawal group in this experiment given that many of the observed differences in experiment one were between CS and CC groups. Future studies will further interrogate the impact of acute or protracted withdrawal on AMPK activation and trafficking following cocaine sensitization and in conjunction with metformin treatment. Another reason for the lack of overall treatment group effects in this experiment were apparent sex differences, especially for tAMPK levels, between rats receiving daily metformin treatment (mS). Metformin is expected to increase AMPK activity (i.e., increase pAMPK), but it may also differentially impact the trafficking of tAMPK between the cytosol and the synapse in male and female rats. Indeed, we were surprised to observe minimal changes in pAMPK levels between the saline+cocaine and metformin+cocaine groups with only an unexpected decrease in pAMPK noted in the cytosol of the NAc shell associated with metformin pretreatment. As in the first experiment, a potential explanation could be related to our examination of cellular subcompartments instead of whole cell lysates. Alternatively, it may be possible that the observed effect of metformin on cocaine sensitization is mediated through a protein other than AMPK. There are numerous studies in multiple contexts highlighting effects of metformin that may not be solely mediated by AMPK [

27]. For example, metformin can inhibit mTOR through an AMPK-independent mechanism by increasing REDD1 expression regulated by p53 with implications for cancer therapy [

44]. Likewise, metformin mediated regulation of NF-κB inflammatory signaling in primary hepatocytes was unaffected by AMPKɑ knockout [

45]. Future work will parse theAMPK-dependent versus AMPK-independent effects of metformin on cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization.

In conclusion, this study explored the interplay between cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization and AMPK activation and trafficking in corticostriatal reward circuitry. Our results provide insights into the complex responses associated with repeated cocaine exposure and metformin pretreatment. Notably, metformin produced an unexpected increase in acute locomotor response to cocaine, but importantly still prevented the development of cocaine sensitization. Our protein analysis revealed the nuanced dynamics of AMPK in distinct brain regions and subcellular compartments. Furthermore, the observed sex differences, especially in tAMPK levels, underscore the importance of considering sex-related variations in future investigations. As we continue to elucidate the metformin-cocaine interaction, we must acknowledge that metformin’s effects may extend beyond the traditional AMPK pathway examined here presenting an exciting avenue for future research.

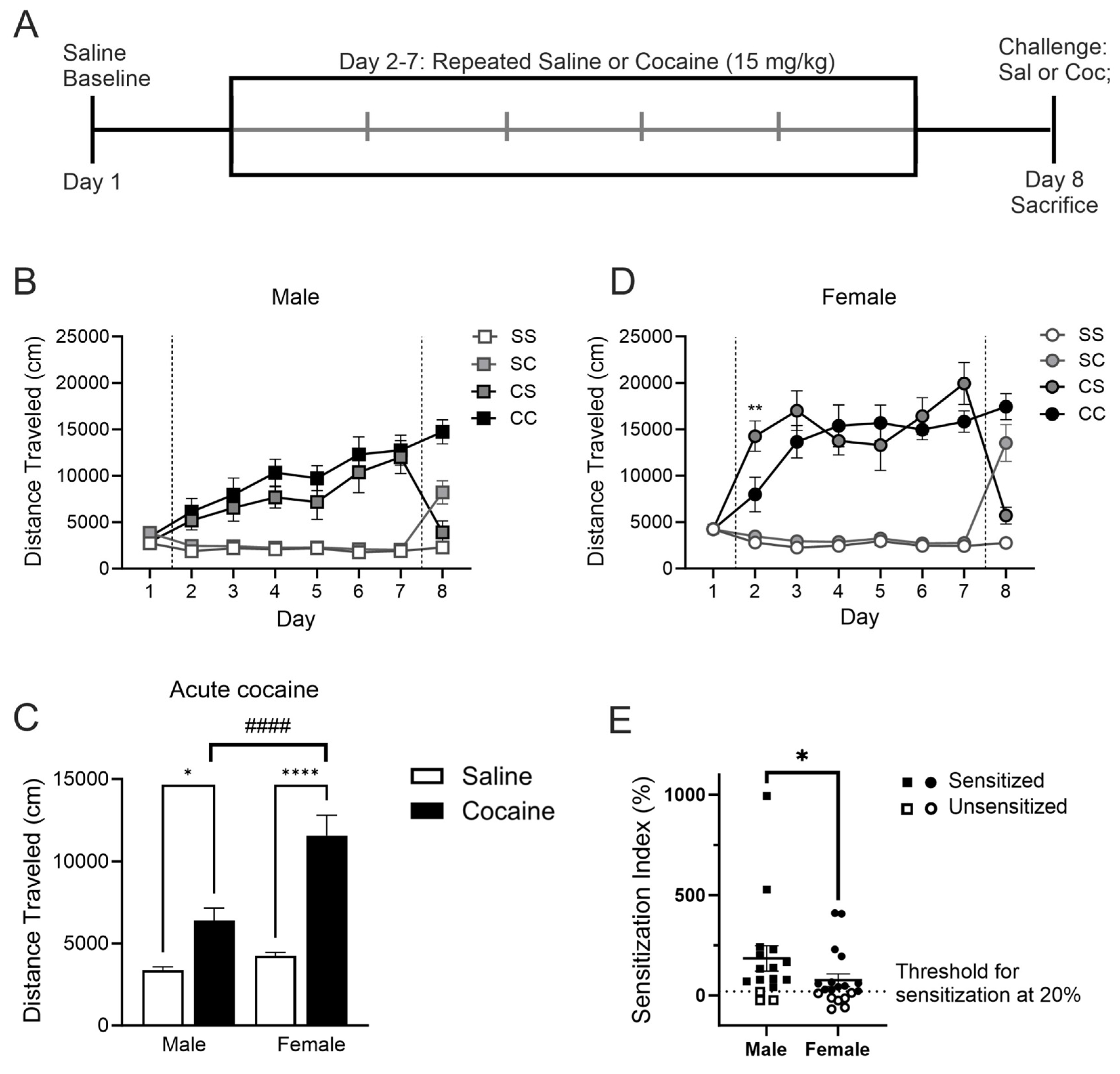

Figure 1.

Experiment 1 timeline and behavioral data. A) Timeline of injections followed throughout experiment 1.B) Sensitization index of male and female rats exposed to chronic cocaine revealed a significant difference between all male and female rats (*p=0.034).C) Acute cocaine increased locomotor activity measured as distance traveled in male and female rats. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 comparing acute saline to acute cocaine. ####p<0.0001 comparing cocaine-treated males to cocaine-treated females. D) Distance traveled (cm) by male rats in groups saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), cocaine cocaine (CC) from day 1-9. A Two-way RM-ANOVA showed main effect of treatment F3,20=22.81, p<0.0001, main effect of day F3.72,74.49=9.419, p<0.0001, and treatment x day interaction F21,140=6.809, p<0.0001. E) Distance traveled (cm) by female rats in groups SS, SC, CS, CC from day 1-9. A two-way RM-ANOVA showed main effect of treatment F3,21=56.70, p<0.0001, main effect of day F3.67,77.22=13.35, p<0.0001, and a treatment x day interaction F21,147=14.56, p<0.0001. **p<0.01 comparing rats in group CC and CS on day 2 by Dunnet’s post hoc testing.

Figure 1.

Experiment 1 timeline and behavioral data. A) Timeline of injections followed throughout experiment 1.B) Sensitization index of male and female rats exposed to chronic cocaine revealed a significant difference between all male and female rats (*p=0.034).C) Acute cocaine increased locomotor activity measured as distance traveled in male and female rats. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 comparing acute saline to acute cocaine. ####p<0.0001 comparing cocaine-treated males to cocaine-treated females. D) Distance traveled (cm) by male rats in groups saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), cocaine cocaine (CC) from day 1-9. A Two-way RM-ANOVA showed main effect of treatment F3,20=22.81, p<0.0001, main effect of day F3.72,74.49=9.419, p<0.0001, and treatment x day interaction F21,140=6.809, p<0.0001. E) Distance traveled (cm) by female rats in groups SS, SC, CS, CC from day 1-9. A two-way RM-ANOVA showed main effect of treatment F3,21=56.70, p<0.0001, main effect of day F3.67,77.22=13.35, p<0.0001, and a treatment x day interaction F21,147=14.56, p<0.0001. **p<0.01 comparing rats in group CC and CS on day 2 by Dunnet’s post hoc testing.

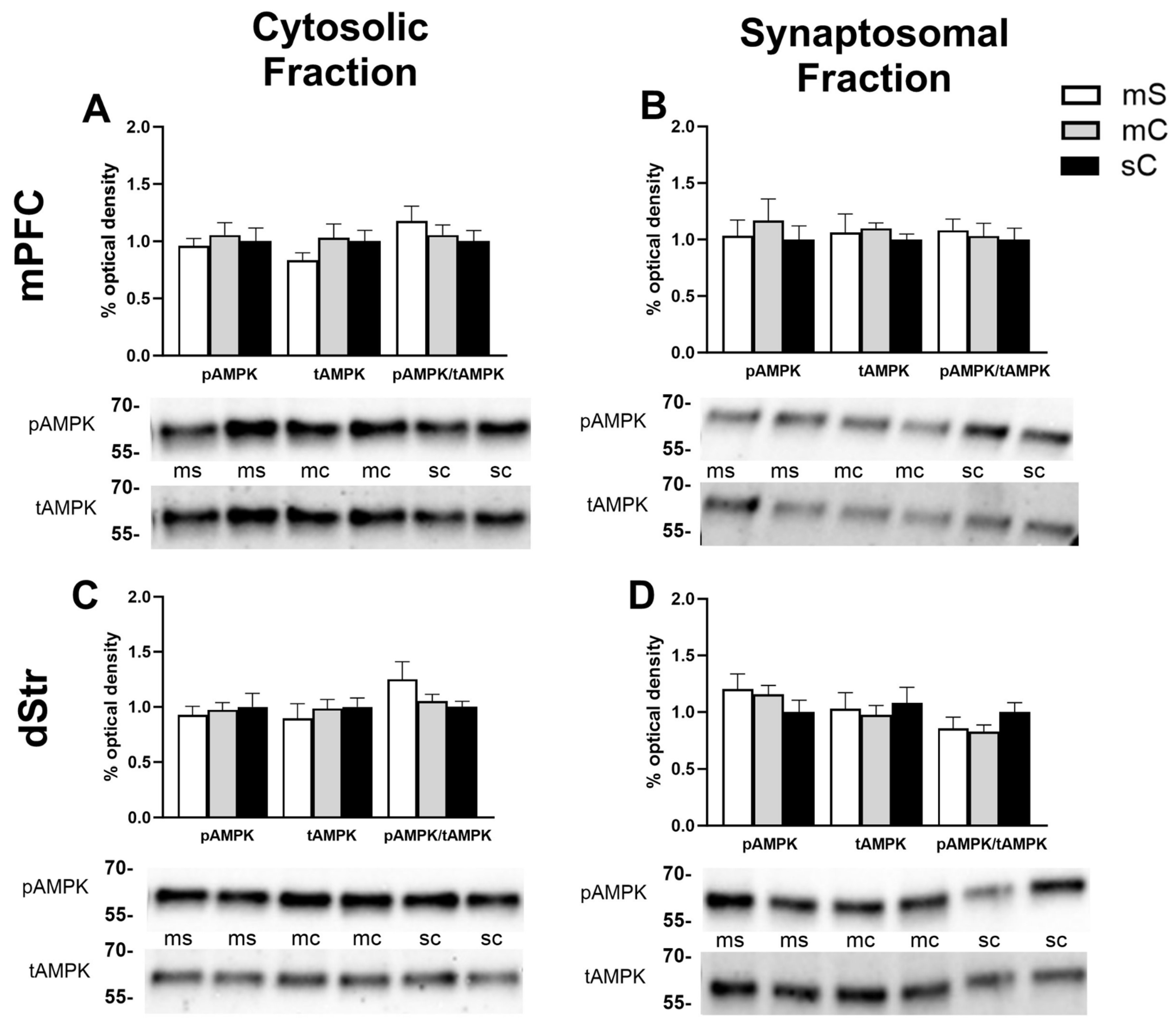

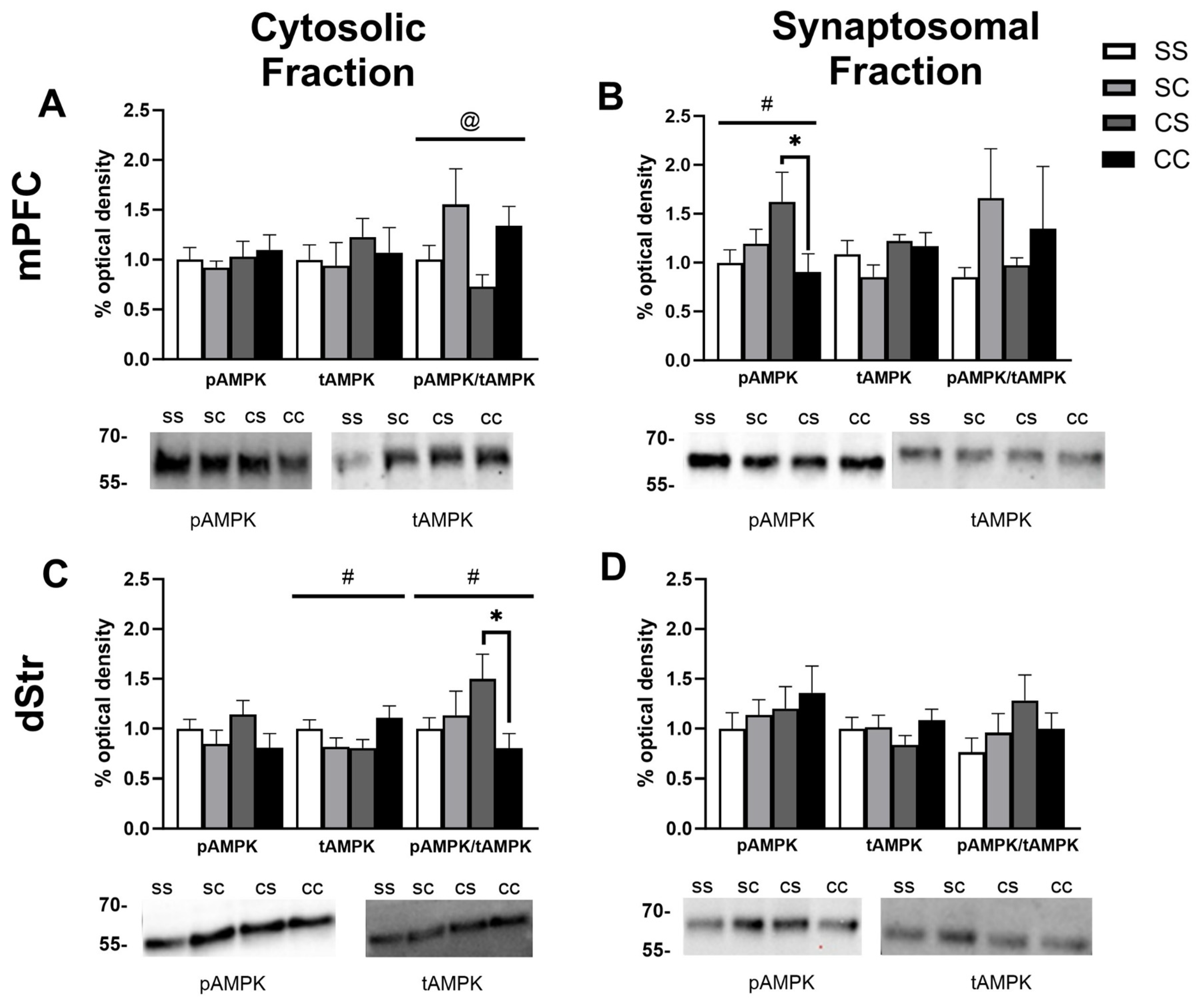

Figure 2.

AMPK levels in the mPFC and dStr of rats in experiment 1. Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), and cocaine cocaine (CC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the mPFC (top; A,B) and dStr (right; B,C). Two-way ANOVAs were performed to assess the impact of initial treatment and challenge injections on protein levels. Main effects of challenge (@), and the interaction between chronic and challenge injection (#) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine differences in treatment groups. A) In the cytosol of the mPFC, there was a main effect of the challenge injection on pAMPK/tAMPK (F1,37=6.580, p=0.0145). B) In the synaptosome of the mPFC, there was a significant interaction between the repeated treatment and the challenge injection when looking at pAMPK (F1,41=5.07, p=0.0298). *p<0.05 when comparing CS and CC. C) In the cytosol of the dStr, there were significant interactions between treatment and challenge injections for tAMPK (F1,40=5.947, p=0.0193) and pAMPK/tAMPK (F1,40=5.106, p=0.0294). *p<0.05 when comparing pAMPK/tAMPK between CS and CC. D) No main effects were found in the synaptosome of the dStr.

Figure 2.

AMPK levels in the mPFC and dStr of rats in experiment 1. Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), and cocaine cocaine (CC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the mPFC (top; A,B) and dStr (right; B,C). Two-way ANOVAs were performed to assess the impact of initial treatment and challenge injections on protein levels. Main effects of challenge (@), and the interaction between chronic and challenge injection (#) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine differences in treatment groups. A) In the cytosol of the mPFC, there was a main effect of the challenge injection on pAMPK/tAMPK (F1,37=6.580, p=0.0145). B) In the synaptosome of the mPFC, there was a significant interaction between the repeated treatment and the challenge injection when looking at pAMPK (F1,41=5.07, p=0.0298). *p<0.05 when comparing CS and CC. C) In the cytosol of the dStr, there were significant interactions between treatment and challenge injections for tAMPK (F1,40=5.947, p=0.0193) and pAMPK/tAMPK (F1,40=5.106, p=0.0294). *p<0.05 when comparing pAMPK/tAMPK between CS and CC. D) No main effects were found in the synaptosome of the dStr.

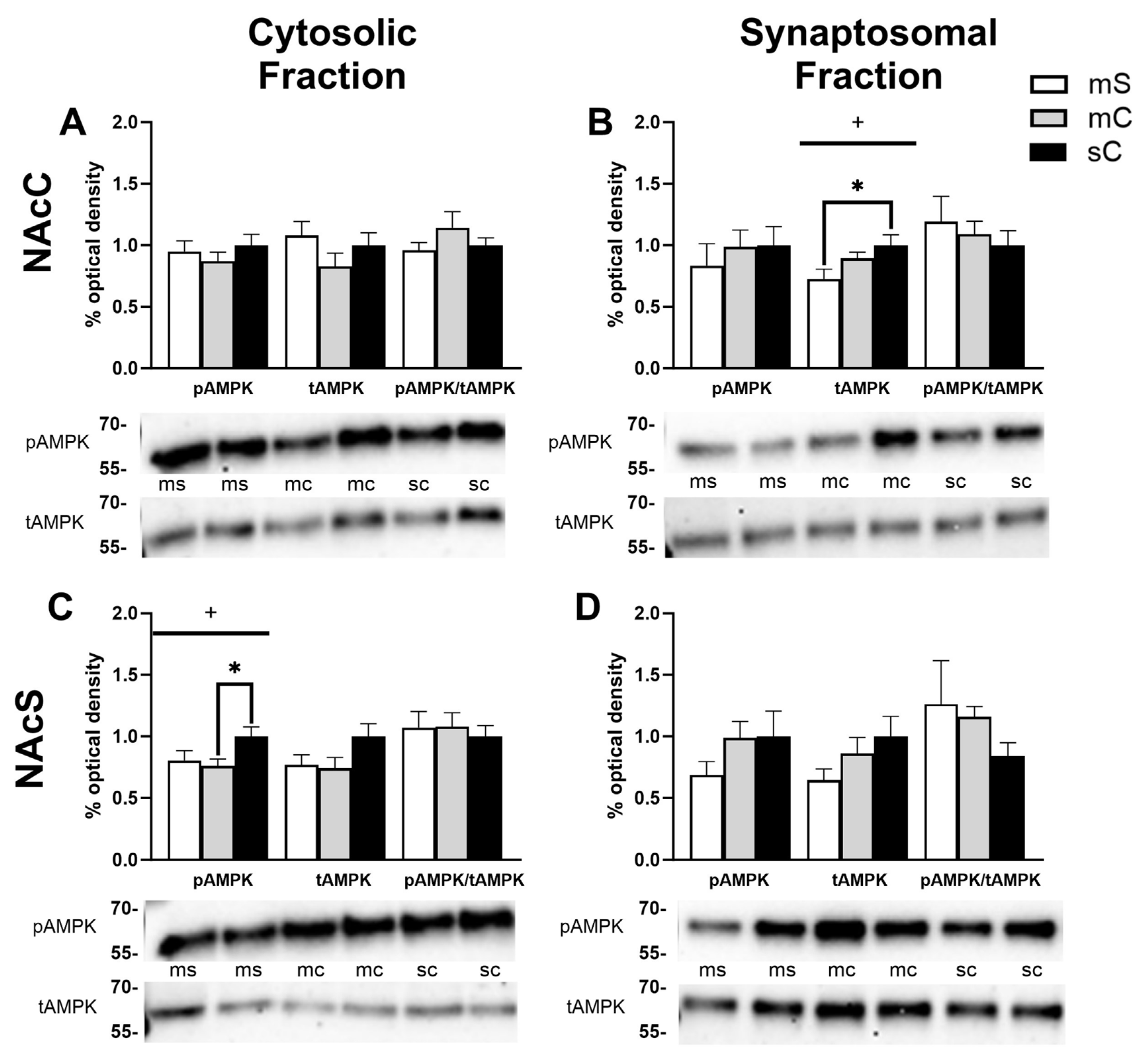

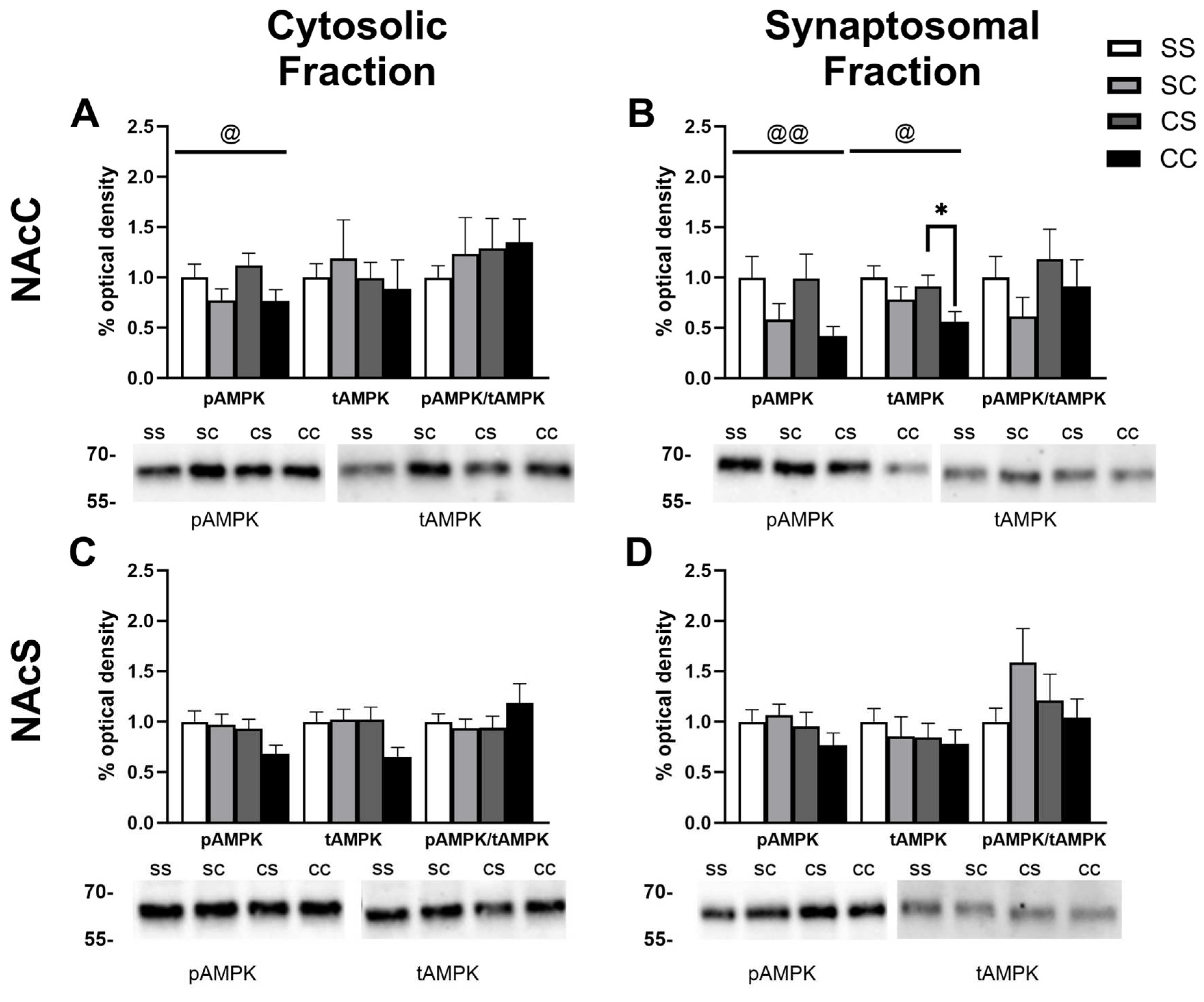

Figure 3.

AMPK levels in the NAcC and NAcS of rats in experiment 1. Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), and cocaine cocaine (CC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the NAcC (top; A,B) and NAcS (right; B,D). Two-way ANOVAs were performed to assess the impact of initial treatment and challenge injections on protein levels. Main effects of challenge (@), and the interaction between treatment and challenge injection (#) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine differences in treatment groups. A) In the cytosol of the NAcC, there was a main effect of challenge injections on pAMPK (F1,42=5.780, p=0.0207). B) In the synaptosome of the NACC, there was a main effect of challenge on pAMPK (F1,42=7.678, p=0.0083) and tAMPK (F1,35=6.252, p=0.0172).**p<0.01 was found when comparing tAMPK levels in group CC and CS. C, D) No main effects were found in the cytosol and synaptosome of the NAcS.

Figure 3.

AMPK levels in the NAcC and NAcS of rats in experiment 1. Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), and cocaine cocaine (CC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the NAcC (top; A,B) and NAcS (right; B,D). Two-way ANOVAs were performed to assess the impact of initial treatment and challenge injections on protein levels. Main effects of challenge (@), and the interaction between treatment and challenge injection (#) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine differences in treatment groups. A) In the cytosol of the NAcC, there was a main effect of challenge injections on pAMPK (F1,42=5.780, p=0.0207). B) In the synaptosome of the NACC, there was a main effect of challenge on pAMPK (F1,42=7.678, p=0.0083) and tAMPK (F1,35=6.252, p=0.0172).**p<0.01 was found when comparing tAMPK levels in group CC and CS. C, D) No main effects were found in the cytosol and synaptosome of the NAcS.

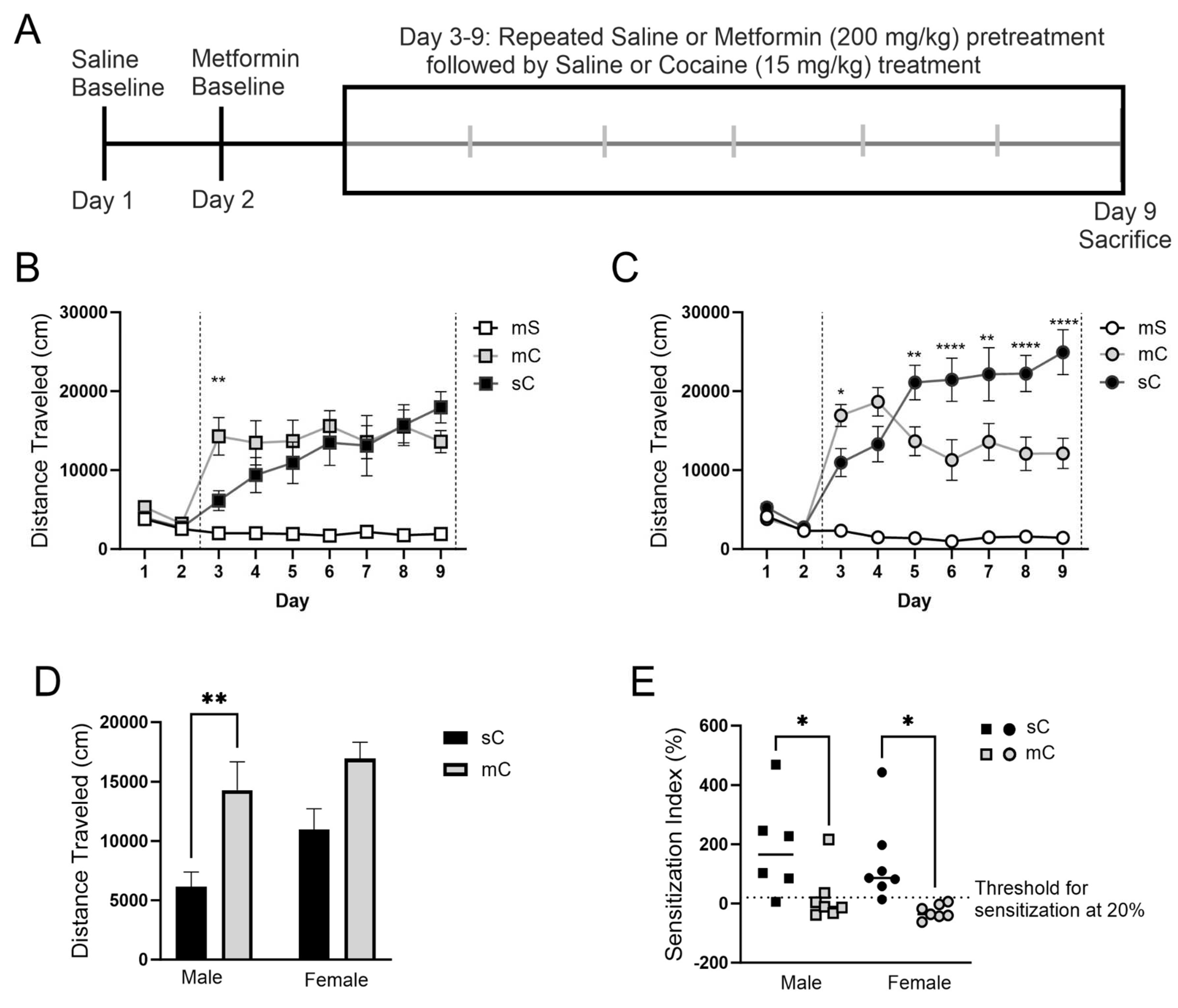

Figure 4.

Experiment 2 timeline and behavioral data. A) Timeline of injections administered in experiment 2. B) Distance traveled (cm) by male rats in groups metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), saline+cocaine (sC) from day 1-9. A two way ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment F2,16=13.50, p=0.0004, day F3.26,51.80=19.92, p<0.0001), and treatment x day interaction (F16,127=8.989, p<0.0001). *p<0.05, **p<0.001 C) Distance traveled (cm) by female rats in groups mS, mC, and sC from day 1-9. A main effect of treatment F2,16=33.26, p<0.0001, main effect of day F3.25,51.11=27.88, p<0.0001, and a treatment x day interaction F16,126=17.34, p<0.0001 was reported. ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. D) Distance traveled by males and females in group sC and mC on day 3. A two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment group F1,22=15.52, p=0.0007 and sex F1,22=4.346, p=0.0489. E) Sensitization Index of male and female rats in group sC and mC. A main effect of treatment was revealed (F1,23=14.03, p=0.0011).

Figure 4.

Experiment 2 timeline and behavioral data. A) Timeline of injections administered in experiment 2. B) Distance traveled (cm) by male rats in groups metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), saline+cocaine (sC) from day 1-9. A two way ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment F2,16=13.50, p=0.0004, day F3.26,51.80=19.92, p<0.0001), and treatment x day interaction (F16,127=8.989, p<0.0001). *p<0.05, **p<0.001 C) Distance traveled (cm) by female rats in groups mS, mC, and sC from day 1-9. A main effect of treatment F2,16=33.26, p<0.0001, main effect of day F3.25,51.11=27.88, p<0.0001, and a treatment x day interaction F16,126=17.34, p<0.0001 was reported. ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. D) Distance traveled by males and females in group sC and mC on day 3. A two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment group F1,22=15.52, p=0.0007 and sex F1,22=4.346, p=0.0489. E) Sensitization Index of male and female rats in group sC and mC. A main effect of treatment was revealed (F1,23=14.03, p=0.0011).

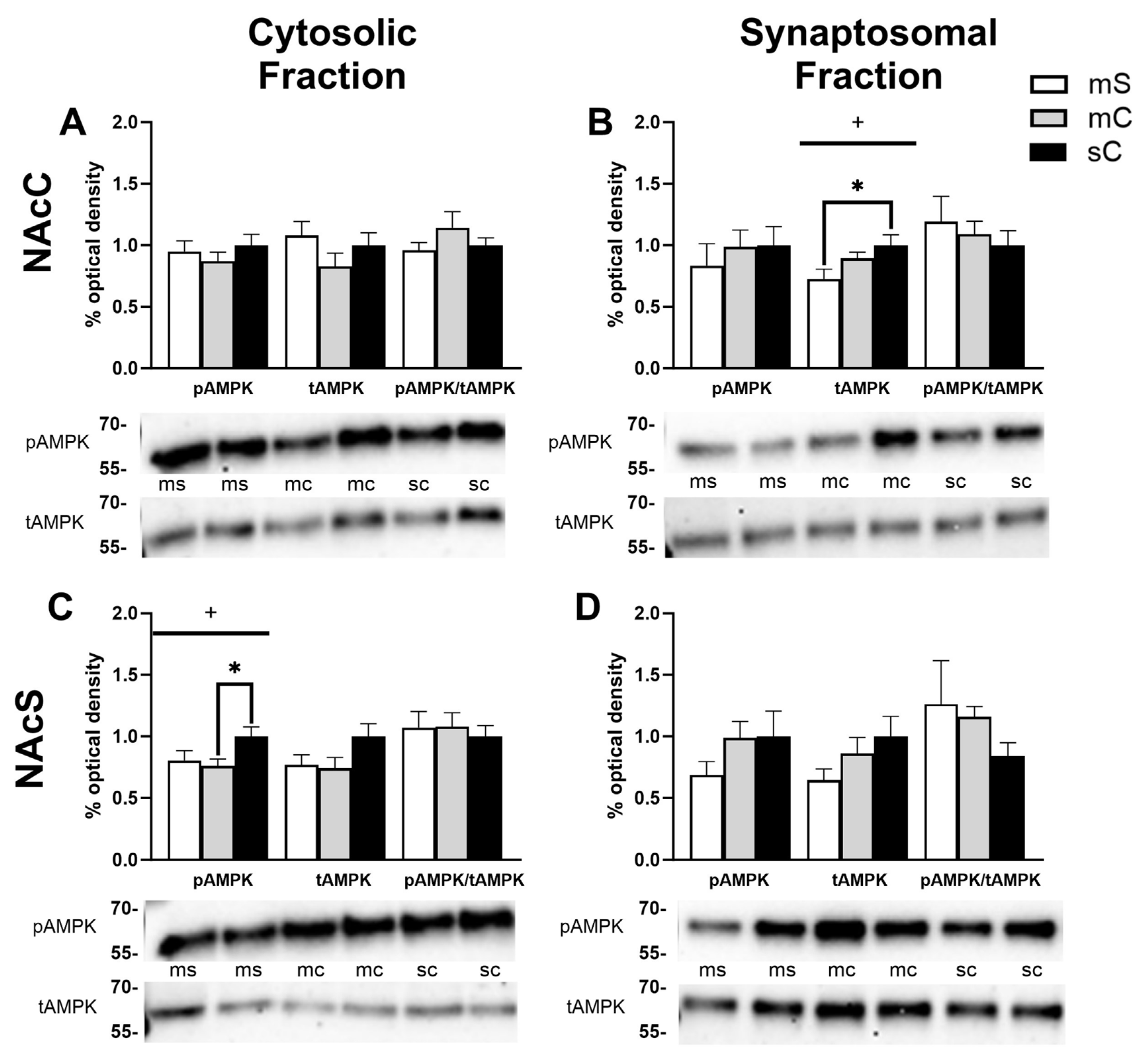

Figure 5.

AMPK levels in the mPFC and dStr of rats in experiment 2. Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), saline+cocaine (sC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the mPFC (top; A,B) and dStr (right; B,D). One way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment on protein levels. No effects of treatment were found in the cytosol and synaptosome of the mPFC and dStr.

Figure 5.

AMPK levels in the mPFC and dStr of rats in experiment 2. Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), saline+cocaine (sC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the mPFC (top; A,B) and dStr (right; B,D). One way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment on protein levels. No effects of treatment were found in the cytosol and synaptosome of the mPFC and dStr.

Figure 6.

AMPK levels in the NAcC and NAcS of rats in experiment 2.Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), saline+cocaine (sC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the NAcC (top; A,B) and NAcS (right; B,D). One way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment on protein levels. Dunnett’s post hoc tests were performed to determine differences in treatment groups. A) Treatment had no effect in the cytosol of the NAcC. B) In the synaptosome of the NAcC, treatment had an effect on tAMPK levels (F2,33=3.373, p=0.0465).*p<0.05 was seen when comparing tAMPK in the mS and sC groups. C) In the cytosol of the NAcS, treatment had an effect on pAMPK levels (F2,31=3.353, p=0.0481). *p<0.05 was seen when comparing pAMPK in the mC and sC groups. D) No effect of treatment was seen in the synaptosome of the NAcS.

Figure 6.

AMPK levels in the NAcC and NAcS of rats in experiment 2.Representative bands and optical density of pAMPK, tAMPK, and pAMPK/tAMPK in treatment groups metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), saline+cocaine (sC). This order is maintained in the graphs and the order of the bands presented in the representative images. Western bands cutouts are from 75 kDa - 55 kDa to display pAMPK and tAMPK levels. Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the NAcC (top; A,B) and NAcS (right; B,D). One way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment on protein levels. Dunnett’s post hoc tests were performed to determine differences in treatment groups. A) Treatment had no effect in the cytosol of the NAcC. B) In the synaptosome of the NAcC, treatment had an effect on tAMPK levels (F2,33=3.373, p=0.0465).*p<0.05 was seen when comparing tAMPK in the mS and sC groups. C) In the cytosol of the NAcS, treatment had an effect on pAMPK levels (F2,31=3.353, p=0.0481). *p<0.05 was seen when comparing pAMPK in the mC and sC groups. D) No effect of treatment was seen in the synaptosome of the NAcS.

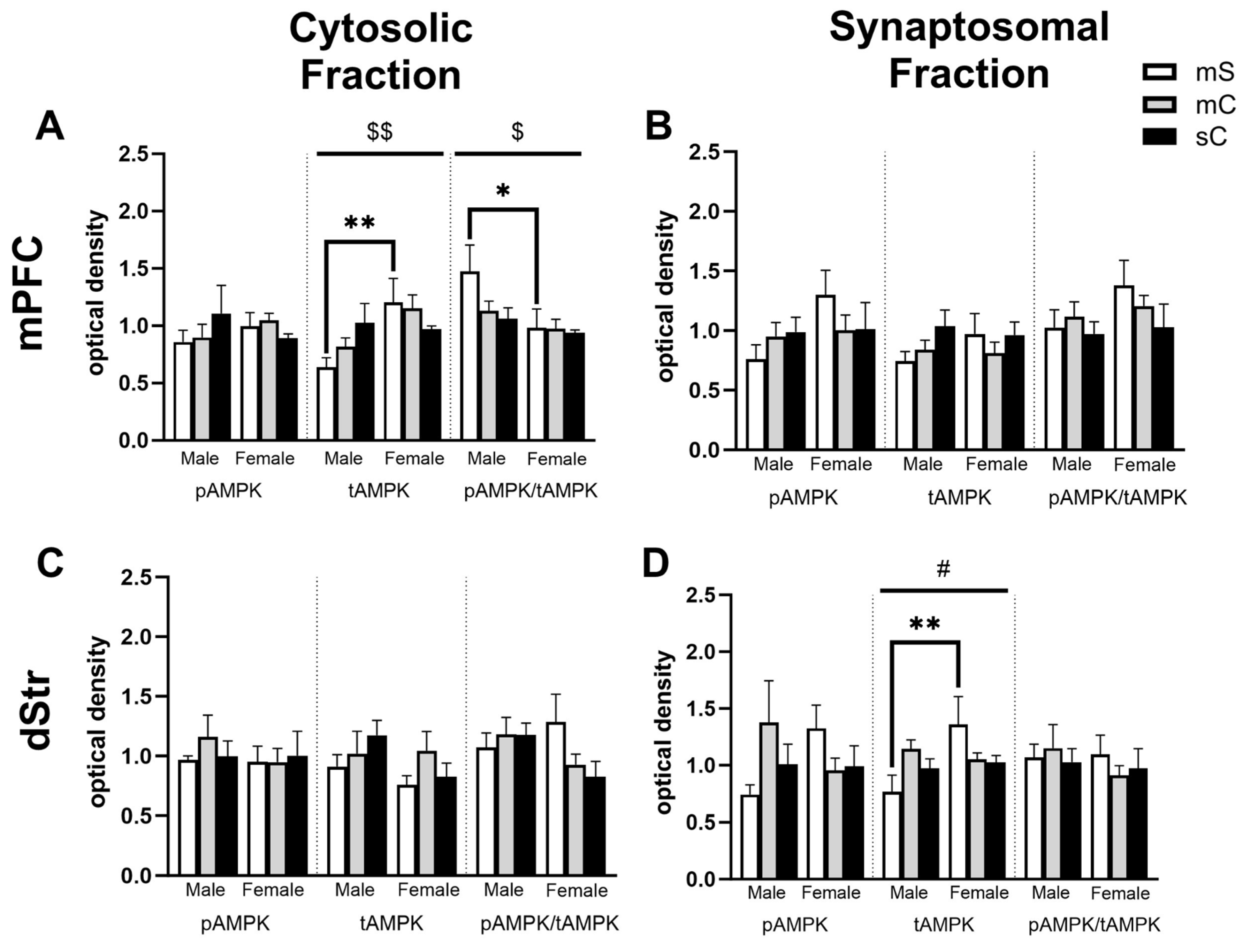

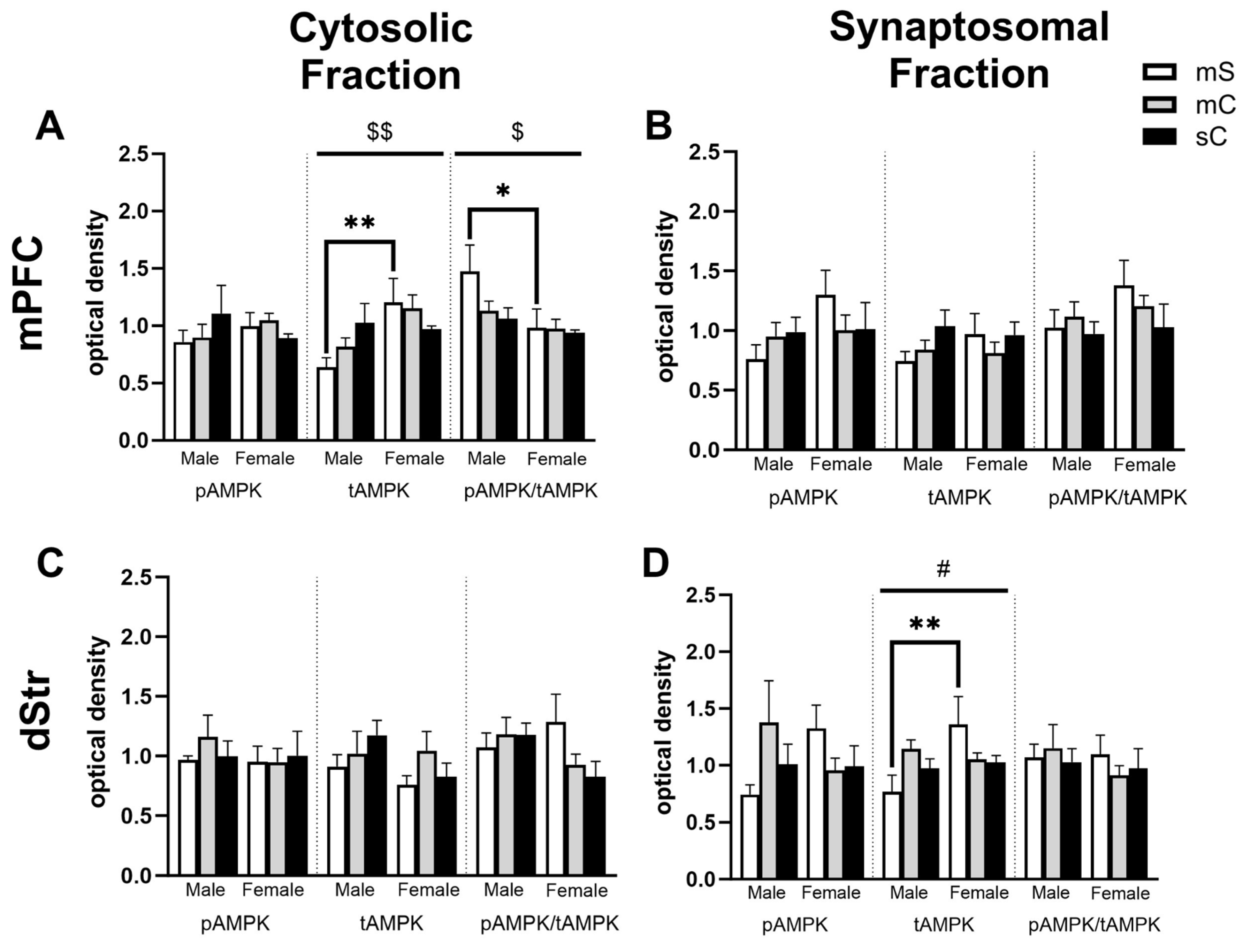

Figure 7.

Sex differences in the mPFC and dStr of rats in experiment 2. Treatment groups included metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), and saline+cocaine (sC). Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the mPFC (top; A,B) and dStr (right; B,D). Two way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment and sex on protein levels. There were no main effects of chronic treatment found. Main effects of sex ($), and the interaction between chronic and challenge injection (#) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine specific sex differences in treatment groups, with *p<0.05, **p<0.01. A) A main effect of sex was seen in tAMPK (F1,31=8.214, p=0.0074) and pAMPK/tAMPK (F1,30=5.389, p=0.0272) levels in the mPFC’s cytosol. B,C) No main effects of sex were seen. D) In the synaptosome of the dStr, a main effect of sex was seen in tAMPK levels (F1,27=4.874, p=0.0359).

Figure 7.

Sex differences in the mPFC and dStr of rats in experiment 2. Treatment groups included metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), and saline+cocaine (sC). Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the mPFC (top; A,B) and dStr (right; B,D). Two way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment and sex on protein levels. There were no main effects of chronic treatment found. Main effects of sex ($), and the interaction between chronic and challenge injection (#) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine specific sex differences in treatment groups, with *p<0.05, **p<0.01. A) A main effect of sex was seen in tAMPK (F1,31=8.214, p=0.0074) and pAMPK/tAMPK (F1,30=5.389, p=0.0272) levels in the mPFC’s cytosol. B,C) No main effects of sex were seen. D) In the synaptosome of the dStr, a main effect of sex was seen in tAMPK levels (F1,27=4.874, p=0.0359).

Figure 8.

Sex differences in the NAcC and NAcS of rats in experiment 2. Treatment groups were metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), and saline+cocaine (sC). Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the NAcC (top; A,B) and NAcS (right; B,D). Two way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment and sex on protein levels. There were no main effects of chronic treatment found. Main effects of sex ($) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine specific sex differences in treatment groups, with *p<0.05, **p<0.01. A) In the cytosol of the NAcC, there was a main effect of sex on tAMPK levels (F1,27=4.874, p=0.0359). B,C,D) No main effects of sex were observed.

Figure 8.

Sex differences in the NAcC and NAcS of rats in experiment 2. Treatment groups were metformin+saline (mS), metformin+cocaine (mC), and saline+cocaine (sC). Protein levels were measured in the cytosolic (left; A,C) and synaptosomal (right; B,D) fractions of the NAcC (top; A,B) and NAcS (right; B,D). Two way ANOVA’s were performed to assess the impact of treatment and sex on protein levels. There were no main effects of chronic treatment found. Main effects of sex ($) are denoted in each brain region and subfraction. Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed to determine specific sex differences in treatment groups, with *p<0.05, **p<0.01. A) In the cytosol of the NAcC, there was a main effect of sex on tAMPK levels (F1,27=4.874, p=0.0359). B,C,D) No main effects of sex were observed.

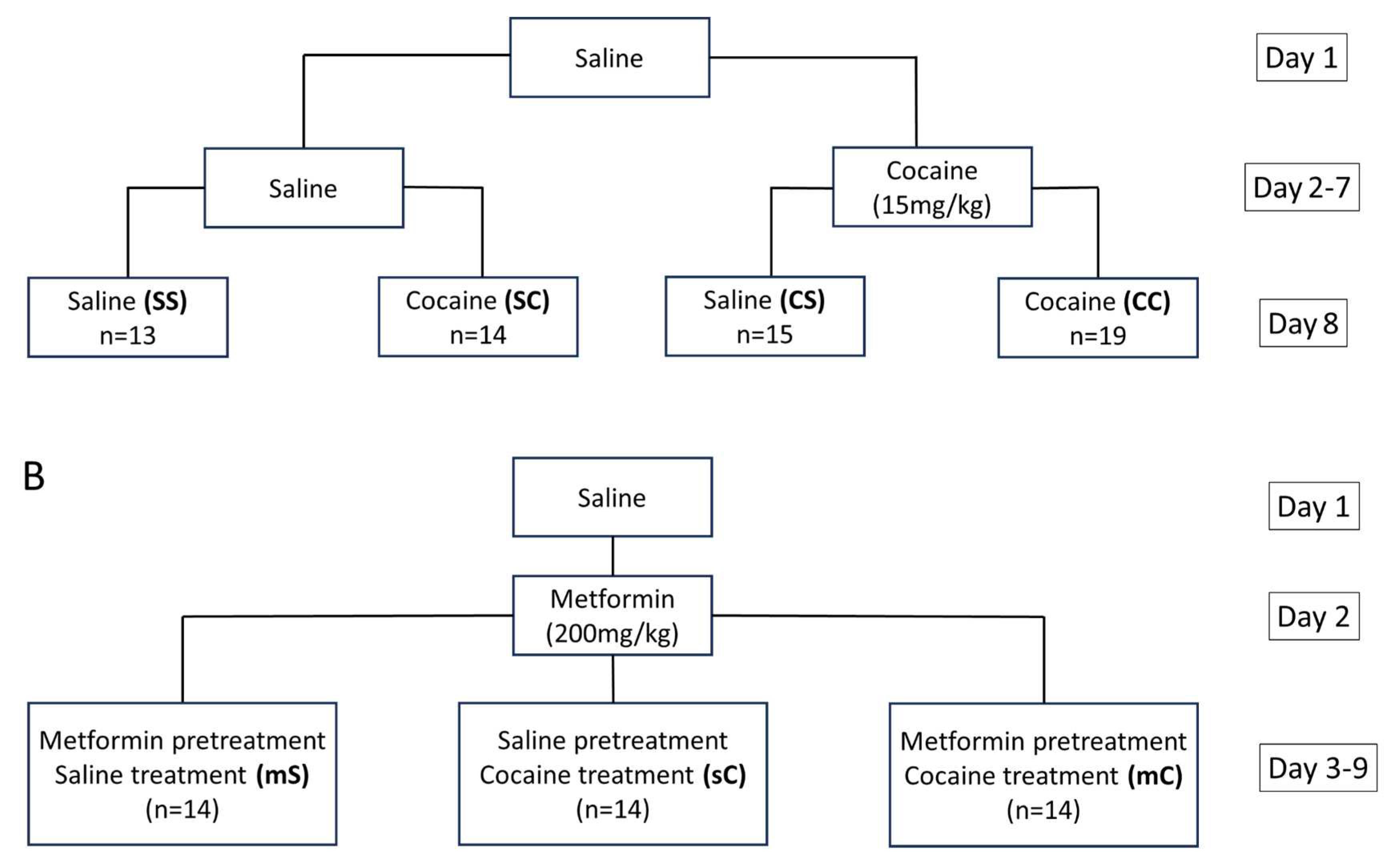

Figure 9.

Experimental groups in experiment 1 and 2. A) Baseline, initial, and challenge injections administered to groups in experiment one. The treatment groups are as follows: saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), cocaine-cocaine (CC). B) Baseline, pretreatment, and treatment injections administered to groups in experiment two. Treatment groups are as follows: metformin-saline (mS), metformin-cocaine (mC), saline-cocaine (sC).

Figure 9.

Experimental groups in experiment 1 and 2. A) Baseline, initial, and challenge injections administered to groups in experiment one. The treatment groups are as follows: saline-saline (SS), saline-cocaine (SC), cocaine-saline (CS), cocaine-cocaine (CC). B) Baseline, pretreatment, and treatment injections administered to groups in experiment two. Treatment groups are as follows: metformin-saline (mS), metformin-cocaine (mC), saline-cocaine (sC).

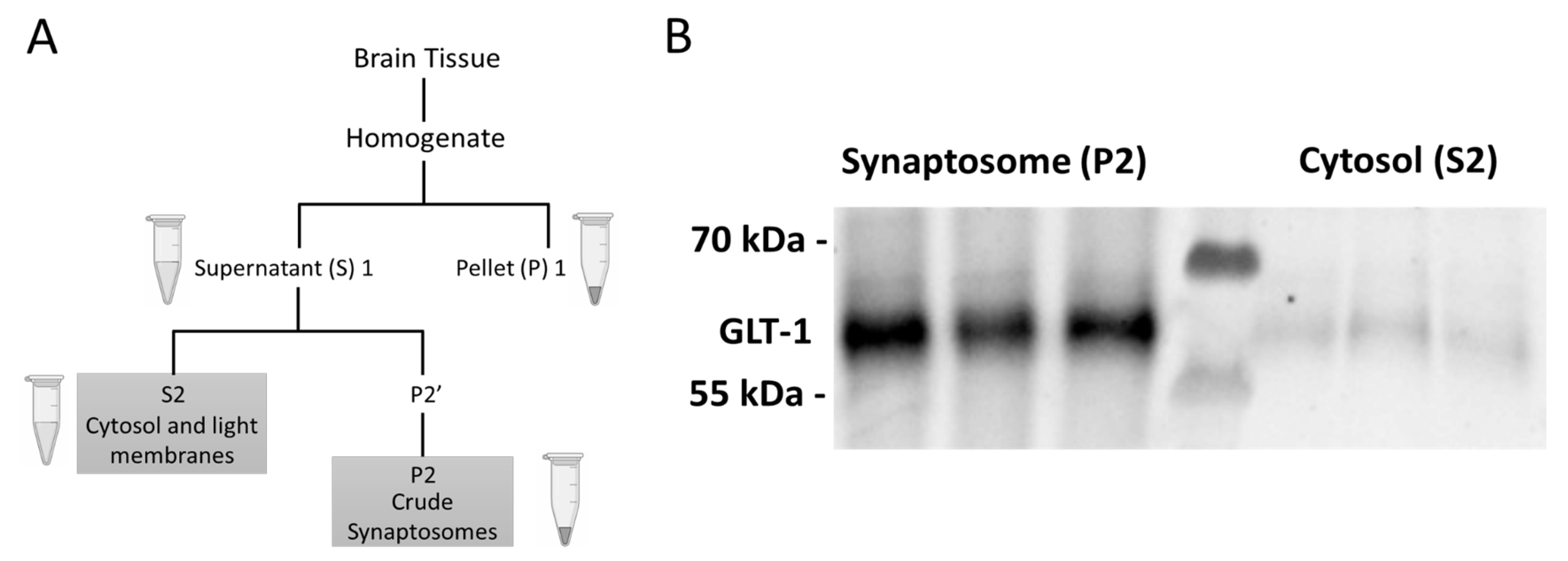

Figure 10.

Process and verification of crude fractionation. A) Supernatant (S) and Pellet (P) subfractions obtained from brain tissue through crude fractionation protocol. B) Western blot image of Glutamate Transporter 1 imaged in the cytosolic and synaptosomal fractions of the dStr.

Figure 10.

Process and verification of crude fractionation. A) Supernatant (S) and Pellet (P) subfractions obtained from brain tissue through crude fractionation protocol. B) Western blot image of Glutamate Transporter 1 imaged in the cytosolic and synaptosomal fractions of the dStr.