1. Introduction

Since the official declaration of Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 [

1], several studies agree that the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, its contagiousness and COVID-19 death related are largely underestimated, thus facilitating its dissemination within communities [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In Senegal, the first case was registered on 2 March 2020 [

9]. Since then, several strategies for combating and preventing COVID-19 have been implemented. These include the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system [

10,

11], the Community Event-Based Surveillance (CEBS) system [

12], the activation of Health Emergency Operation Center [

13], the formal identification of COVID-19 cases as defined by WHO including their active case-contact detection [

14] in order to identify transmission clusters [

15]. During the first wave of COVID-19 (March – November 2020), all confirmed COVID-19 cases were isolated at the Treatment Center of Epidemics (TCE), open for this purpose. The second and third waves of COVID-19 in Senegal covered the periods from December 2020 – March 2021 and July – September 2021 respectively [

16]. Except for patients with the most severe form or with high-risk conditions for severe COVID-19 requiring hospitalization, individuals who tested positive with minor or no symptoms, both diagnosed via contact tracing or screening campaign at the Blaise Diagne International Airport and other border crossings in the country, were quarantined with regular follow-up at the out of hospital TCE [

7]. In addition to non-pharmaceutical interventions (population sensitization on prevention measures, bans on large public gatherings, mandatory wearing of face mask, closing schools and universities, lockdown restrictions…) [

17], the vaccination was introduced on February 23th, 2021 and targeted the population considered at risk i.e. health personnel, the elderly and those living with comorbidities. Gradually, it was extended to the general population, however for pregnant women it was only from August 9th, 2021. Vaccination coverage at the time of the second national COVID-19 seroprevalence survey (November 2-14, 2021) was already low by 18% [

18].

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Senegal, the first laboratory strategy was to test all suspected cases of symptomatic COVID-19. All contacts of confirmed cases were also systematically tested. However, this strategy was changed due to its substantial financial cost and human resources need. A second strategy put in place tested only contacts with COVID-19 symptoms or high-risk of death contacts (i.e., contacts of advanced age and/or with comorbidities such as chronic diseases) [

15]. To overcome the constraints related to molecular tests, the lab-based detection methods for SARS-CoV-2 were later expanded to rapid diagnostic antigen tests for decentralized screening while initially exclusively done by the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) as a gold standard [

19,

20]. The serological methods could contribute substantially in monitoring the epidemic dynamics in target population and help control of the rapid global spread of SARS-CoV-2 [

20,

21].

Despite the necessity of their prenatal consultations, pregnant women have in the majority deserted health facilities for fear of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection. The conjunction of these different phenomena, particularly during the critical windows of the second and third waves of COVID-19 in Senegal [

16], that could put pregnant women more in a risky situation. The COVID-19 pandemic has so far raised questions about the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, particularly on the outcome of pregnancy, the health of the child-mother couple during and after pregnancy [

8,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Among these concerns, the high risk of mortality in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared with age-matched nonpregnant individuals [

3,

8,

23,

24,

25]. In addition, the risks of preterm deliveries, complications requiring intensive care and invasive ventilation should also be taken into account [

22,

28,

29,

30]. Unfortunately, despite these concerns related to COVID-19 in the obstetrical population, there is limited published seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 data among pregnant women in Africa [

3,

6,

8,

25]. Hence the need to study the extent of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women.

Given the health emergency, several initiatives focused on the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection emerged from the first months of the pandemic. On the laboratory component, it was diagnostic strategies that have been pursued, focusing on molecular strategies for viral genetic material, antigen tests, and serological assays, and innovations for improving the diagnostic sensitivity and capabilities [

19,

20]. In the absence of universal access to RT-PCR or qRT-PCR, and even if it is not recommended to establish the diagnosis of the COVID-19, the serological detection of present and post-exposure constitutes a major alternative in terms of public health strategies. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women attending antenatal consultation (ANC) to SARS-CoV-2 in Senegal.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and study design

This is an ancillary study of the EPIVHE (Environment and Epidemiology of the hepatitis E virus) project, a seroepidemiological survey of hepatitis E, conducted among pregnant women attending antenatal consultation (ANC) in Senegal. A non-redundant consecutive recruitment of participants was carried out over a period from March to July 2021. The sampling plan, description of the participants' recruitment sites, data collection procedure, inclusion and non-inclusion criteria, socio-demographic and other relevant information to the study were fully described in Diouara et

al. [

31]. During the sampling period, no participant presented clinical signs suggestive of a severe form of COVID-19 and no cases of hospitalization had been reported. None of participant had received a COVID-19 vaccine. Ethical and administrative authorization was obtained from the National Health Research Ethics Committee (N°000130/MSA/CNRES/Sec) and the Ministry of Public Health and Social Action of Senegal (N°00000582/MSAS/DPRS/DR).

2.2. Sample preparation and anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies detection

The plasma samples stored at -80°C were subjected to a qualitative assay based on the immunoenzymatic method. The test used was the WANTAI SARS-CoV-2 Ab ELISA (Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise, Beijing) and in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. It should be noted that this test allows the qualitative detection of total antibodies (including IgM and IgG), markers of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in patient suspected of previous infection, or for the detection of seroconversion in patients following know recent infection. The WANTAI SARS-CoV-2 Ab ELISA is a two-step incubation antigen “sandwich” enzyme immunoassay kit, which uses polystyrene microwell strips pre-coated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain (S1/RBD) antigen.

The reported sensitivity and specificity of the test are 94.36% and 100% respectively according to the manufactured [

32]. Optical density was read using the MICRO READ 1000 ELISA Plate Analyser (Global Diagnostics B, Belgium). The results are calculated by relating each specimen absorbance (A) value to the plate’s cut-off value (C.O.). For the calculation of the cut-off value (C.O.), it was C. O= Nc + 0.16. Nc= the mean of absorbance value for three negative controls. A ratio of signal to Cut-off values was calculated for each sample and a sample was declared to be negative if index < 1, positive if the index was ≥ 1, and borderline if the index was range 0.9 to 1.1. All samples declared positive in the first tests were re-tested by WANTAI SARS-CoV-2 Ab in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence was calculated as the number of individuals with specific SARS-CoV-2 antibodies divided by the total number of individuals in the sample and the confidence level was set at 0.95. The selected general factors examined were, participant’s age, residential locality, recruitment period, level of education, marital and professional status. These were selected due to their potential association to SARS-CoV-2 infection as observed in other studies [

3,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

28,

29,

30,

33]. To assess factors associated with seropositivity, bivariate analyzes were performed with JMP® Pro Version 15.0.0 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2021). For frequencies below 5, chi2 or Fischer tests were performed. In all cases, the confidence interval was set at 0.95 and the

p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and socio-economical characteristics

During the EPIVHE seroepidemiological survey [

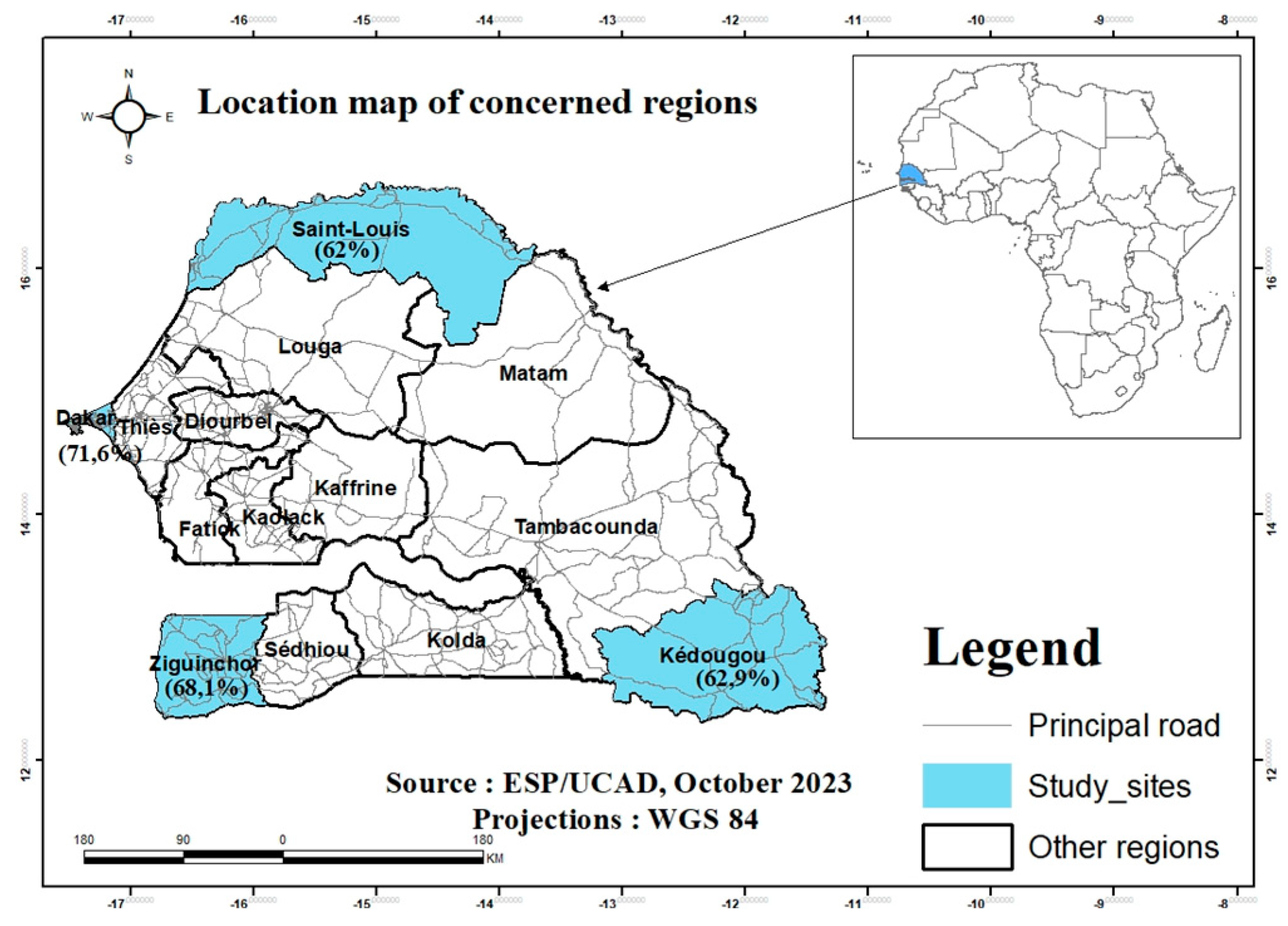

31], we recruited 1227 pregnant women in five health facilities including two in Dakar (gynecological clinic of CHUN Aristide le DANTEC (n=50) and the Gaspard Kamara Health Center (n=116)). The other sites were the Regional Hospital Center (RHC) of Saint-Louis, the Health District of Kédougou and the Health Center of Néma de Ziguinchor, with respectively 400, 397 and 264 participants (

Figure 1). The distribution by age group was 43%, 29.1% and 18.2%, respectively for [18-23], [24-29] and [30-35 years old]. Only 9.7% of participant were aged 36 years or over; among them, 3.6% (n=45) were over 40 years old. The median age was 25 years [18 – 50 years].

Regarding the level of education, only 9% of participants had reached a higher level of education. The overall uneducated rate was 31.7% with higher proportion recorded in Kédougou (58.7%). Contrary to other localities, 25.9% of women in Dakar had completed higher education. Only 18.7% of participants had regular income (salaried or self-employed). Among them, 45.8% were residents in Dakar, while 11.8% in Saint-Louis. In addition to the aforementioned socio-demographic and economic characteristics by locality, the marital status and the results of the survey relating to hand hygiene, in particular systematic hand washing, are also presented in

Table 1.

3.2. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence, variability and potential associated factors

In the current study, the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence based on total anti-SARS-COV-2 Ab measurement was 64.9% (797/1227) with higher exposure rates in Dakar 71.6% (119/166) and Ziguinchor 68.1% (180/264). Kédougou and Saint-Louis recorded 62.9% (250/397) and 62% (248/400) respectively (

Figure 1, Table 2). The highest seroprevalences were observed in Dakar, the capital, and in Ziguinchor. Although no statistically significant difference was observed according to age and localities, the highest seroprevalences (67.2%) were reported in the ≥36 years group and in Dakar (71,6%) with

p-value egal to 0.9275 and 0.7024, respectively (

Table 2). In addition, we found no association between factors such as age, level of education, marital and professional status (

Table 3).

Figure 1.

Map of Senegal, with indication of the geographical sites of the study and SARS-CoV-2 anti-bodies seroprevalence.

Figure 1.

Map of Senegal, with indication of the geographical sites of the study and SARS-CoV-2 anti-bodies seroprevalence.

Table 1.

Demographic and socio-economical characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic and socio-economical characteristics.

| Variable |

Study sites |

|

| Saint-Louis |

Dakar |

Kédougou |

Ziguinchor |

All sites |

| (n = 400) |

(n = 166) |

(n = 397) |

(n = 264) |

(n = 1227) |

| Frequency (%) |

Median |

Frequency (%) |

Median |

Frequency (%) |

Median |

Frequency (%) |

Median |

Frequency (%) |

Median |

| Range of age |

| 18 - 23 |

112 (28) |

20 |

49 (29.5) |

21 |

256 (64.5) |

19 |

111 (42) |

20 |

528 (43) |

20 |

| 24 - 29 |

136 (34) |

26 |

44 (26.5) |

27 |

90 (22.7) |

26 |

87 (33) |

26 |

357 (29.1) |

26 |

| 30 - 35 |

101 (25.3) |

32 |

48 (28.9) |

32.5 |

29 (7.3) |

30 |

45 |

32 |

223 (18.2) |

32 |

| 36 and above |

51 (12.8) |

36 |

25 (15.1) |

37 |

22 (5.5) |

38 |

21 |

39 |

119 (9.7) |

38 |

| Educational level |

| None |

62 (15.5) |

. |

25 (15.1) |

. |

233 (58.7) |

. |

69 (26.1) |

. |

389 (31.7) |

. |

| Primary |

170 (42.5) |

. |

46 (27.7) |

. |

82 (20.7) |

. |

77 (29.2) |

. |

375 (30.6) |

. |

| Secondary |

122 (30.5) |

. |

52 (31.3) |

. |

75 (18.9) |

. |

104 (39.4) |

. |

353 (28.8) |

. |

| Higher |

46 (11.5) |

. |

43 (25.9) |

. |

7 (1.8) |

. |

14 (5.3) |

. |

110 |

. |

| Marital status |

| unspecified |

11 (2.8) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

16 (4.0) |

. |

4 (1.5) |

. |

31 (2.5) |

. |

| Single |

8 (2) |

. |

6 (3.6) |

. |

12 (3) |

. |

39 (14.8) |

. |

65 (5.2) |

. |

| Married |

381 (95.3) |

. |

160 (96.4) |

. |

369 (93) |

. |

220 (83.3) |

. |

1130 (92) |

. |

| Divorced or widowed |

0 (0) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

1 (0.4) |

. |

1 (0.08) |

. |

| Regular income (paid work) |

| unspecified |

6 (1.5) |

. |

1 (0.6) |

. |

36 (9.1) |

. |

4 (1.5) |

. |

47 (3.8) |

. |

| Yes |

47 (11.8) |

. |

76 (45.8) |

. |

63 (15.9) |

. |

43 (16.3) |

. |

229 (18.7) |

. |

| No |

347 (86.8) |

. |

89 (53.6) |

. |

298 (75.1) |

. |

217 (82.2) |

. |

951 (77.5) |

. |

| Systematic hand washing |

| unspecified |

0 (0) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

16 (4) |

. |

4 (1.5) |

. |

20 (1.6) |

. |

| Occasionally |

0 (0) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

6 (2.3) |

. |

6 (0.5) |

. |

| Yes |

392 (98) |

. |

166 (100) |

. |

350 (88.2) |

. |

206 (78) |

. |

1114 (90.8) |

. |

| No |

8 (2) |

. |

0 (0) |

. |

31 (7.8) |

. |

48 (18.2) |

. |

87 (7.1) |

. |

| SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence |

| SARS-CoV-2 Ab Positive |

248 (62) |

. |

119 (71.6) |

. |

250 (62.9) |

. |

180 (68.1) |

. |

797 (64.9) |

. |

Table 2.

Variability in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence according to age groups and localities.

Table 2.

Variability in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence according to age groups and localities.

| |

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies |

| [Age groups] (%) |

n (%) |

p-value |

| [18–23], n = 528 (43) |

331 (62.6) |

0.9275 |

| [24–29], n = 357 (29.1) |

238 (66.6) |

| [30–35], n = 223 (18.2) |

148 (63.5) |

| ≥36 years, n = 119 (9.7) |

80 (67.2) |

| Total (n=1227) |

797 (64.9) |

| Location (Number of participant) |

| Saint-Louis (n = 400) |

248 (62) |

0.7024 |

| Dakar (n = 166) |

119 (71.6) |

| Ziguinchor (n = 264) |

180 (68.1) |

| Kédougou (n = 397) |

250 (62.9) |

| Total (n = 1227) |

797 (64.9) |

Table 3.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and potential associated factors.

Table 3.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and potential associated factors.

| |

|

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies |

| Educational level |

Frequency (%) |

n |

Prevalence (%) |

p-value |

| None |

389 (31.7) |

247 |

63.4 |

0.9175 |

| Primary |

375 (30.6) |

254 |

67.7 |

| Secondary |

353 (28.8) |

229 |

64.8 |

| Higher |

110 (8.9 ) |

67 |

60.9 |

| Marital status |

| unspecified |

31 (2.5) |

17 |

54.8 |

0.7564 |

| Single |

65 (5.2) |

49 |

75.3 |

| Married |

1130 (92) |

730 |

64.6 |

| Divorced or widowed |

1 (0.08) |

1 |

100 |

| Regular income (paid work) |

| unspecified |

47 (3.8) |

26 |

55.3 |

0.7661 |

| Yes |

229 (18.7) |

154 |

67.2 |

| No |

951 (77.5) |

617 |

64.8 |

| Systematic hand washing |

| unspecified |

20 (1.6) |

13 |

65 |

0.9949 |

| Occasionally |

6 (0.5) |

4 |

66.6 |

| Yes |

1114 (90.8) |

726 |

65.1 |

| No |

87 (7.1) |

54 |

62 |

4. Discussion

This is the first large study conducted aiming to document the seroprevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women in Senegal. The retrospective analysis of sera collected during the second and third waves of COVID-19 showed a high seroprevalence in pregnant women attending the ANC (64.9%) compared to those obtained during the first (28.4% in November - December 2020) [

34] and second national population-based cross-sectional survey (72,2% in November 2021) [

18]. In this study, seroprevalence observed among participants in Dakar was higher compared to other localities. Previous studies in Senegal reported this variability in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence [

34,

35,

36]. This difference, even statistically not significant (

p-value =0.7024), could be explained by the fact that Dakar, the capital city of Senegal, remains the epicenter of the epidemic [

15]. It should be noted that Dakar is one of the West African capitals which is strongly connected to other regions of the world. The city has the highest population density and also concentrates most of the economic activities of the country [

37]. Furthermore, our results show that the number of participants was low in Dakar (less than 2 times compared to Saint-Louis and Kédougou and 1.5 times for Ziguinchor). At recruitment period, the magnitude of the COVID-19 crisis in Dakar compared to other localities could be the cause of a low attendance antenatal care as it has been reported elsewhere [

8,

27].

Our findings showed that Ziguinchor was the second locality with the highest SARS-CoV-2 total Ab seroprevalence (68.1%). The seroprevalence founded in the bordering after the first 3 transmission waves were also high, among pregnant women in Gambia (90%), among adults involved in health care and health research (18%) [

38], in unvaccinated people living with HIV (27.7%) [

39] in Guinea-Bissau, and in general population in Guinea Conakry (42.4%) [

40,

41]. Ultimately, the high seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 total Ab observed in this unvaccinated subpopulation could also be explained by the circulation of the highly transmissible omicron and delta variants during the second and third waves of the COVID-19 epidemic in Senegal [

42,

43].

The heterogeneity of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences observed here is similar to that reported elsewhere. In their review, Lewis et

al. report a strong heterogeneity both within countries – urban versus rural settings, children versus adults – and between countries and African subregion, that highlights the need for targeted serosurvey and interventions at population level [

6]. In Senegal, a national population-based cross-sectional survey [

34] and the others studies conducted in healthcare settings [

35] and among hemodialysis patients [

36] also report this variability in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence depending on the locality with high rates observed in Dakar and Ziguinchor in particular.

Contrary to what is usually or even systematically done in northern countries, where RT-PCR tests from nasopharyngeal samples are offered to pregnant women admitted for labour and delivery [

20,

33]; in Senegal access to molecular diagnostics was still limited. During the sampling period, the use of rapid diagnostic tests including ELISA tests was not authorized for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection by local authorities. Only RT-PCR tests are mandatory and intended to establish active infection of SARS-CoV-2 in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals [

15]. Therefore, those with resolved infections or ongoing infections who are no longer testing positive by RT-PCR may be missing. This constitutes a limit for measuring the extent of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 during a pandemic period. In such situation and retrospectively, the use of serological tests based on the detection of antigen, IgM and IgG or IgG antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 [

20] would make it possible to examine the extent of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. However, diagnostic performance would be influenced by the timing and duration of seroconversion including the IgM and IgG antibodies generation (which varies depending on the patient and disease severity) [

20]. Some studies also reported rapid decay of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies over the time [

44,

45] while others suggest IgG stability for at least 5 months after infection [

41]. In this present study, we used the Wantai SARS-CoV-2 Total Ab ELISA, for which satisfactory anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies detection performances from samples collected 14 days post-onset of symptoms in both hospitalized patients and those with mild or asymptomatic infections were reported [

21,

32,

46,

47]. Moreover, this test has been widely used in other studies conducted in Africa to measure seroprevalence [

6,

21,

34,

46,

48,

49]. Considering the variability of the persistence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in serum mentioned above [

20,

41,

44,

45] and the possibility of premature sample collection for antibody detection after positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR [

20,

21,

46], we cannot exclude an underestimation of the seroprevalences observed in this study.

Strengths and limitations

The major limitations of this study were absence of information on maternal and perinatal outcomes. Unlike several similar studies, our study does not provide information on gestational age, pre-pregnancy diabetes, pre-pregnancy hypertension, pregnancy outcomes (preterm birth, delivery with or without complications, maternal and neonatal mortality), vertical or horizontal transmission [

3,

22,

24,

28,

29,

30]. However, besides the heterogeneity of seroprevalences observed between the different localities; this study fills a relative gap in the level of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 of pregnant women, previously unknown at the national level. All of this information demonstrates the relevance and added value of the implementation of SARS-CoV-2 serological-based diagnostics routinely in addition to molecular tests.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted a high seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (64.9%) in pregnant women attending an antenatal consultation (ANC). These findings showed also that SARS-CoV2 has spread massively in Senegal, despite the few reported cases, as in other African countries. This SARS-CoV-2 exposure rate could be linked to the enrollment period, which overlaps with the second and third waves of COVID-19 in Senegal. These results could help in decision-making regarding of care for pregnant women in a pandemic context.

Author Contributions

Conceived, obtaining funding: A.A.M.D., A.A.; coordinated the work, drafted the manuscript: A.A.M.D., A.A.; performed the work: A.A.M.D., F.T., S.C., A.S., S.D.T., S.S., B.K.; curation: A.A.M.D.; formal analysis: A.A.M.D., A.A.; investigation: A.A.M.D., A.A., S.L., N.M.M., F.D., M.E.F.D., H.D.N., B.B.; supervision: A.A.M.D. validation: A.A.M.D., C.T.K., M.P., AA; reviewed the manuscript: A.A.M.D., F.T., S.C., N.M.M., H.D.N., A.S., S.D.T., S.S., B.K., H.S., Y.D., S.L., F.D., M.E.F.D., B.B., C.M.N., C.T.K., M.P., A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The EPIVHE project was funded by Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) through its program of young team associated with IRD (JEAI). This ancillary study benefited from additional funds through the SEN’RT-BIOBANKING – 2022-23 project of the École Supérieure Polytechnique (ESP) of UCAD, which enabled the purchase of reagents and consumables.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Senegalese National Ethics Committee for Health Research (N°000130/MSA/CNRES/Sec, protocol code SEN20/31, date of approval: 5 July 2020) and the Ministry of Public Health and Social Action (N°00000582/MSAS/DPRS/DR, protocol code SEN20/31, date of approval: 8 July 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in this study as well as the administrative and technical staff of all the health structures that facilitated the implementation of this work. We are grateful to the top management of the Ecole Supérieure Polytechnique (ESP) for their support to the GRBA-BE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., et al., Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Science, 2020. 368(6490): p. 489-493. [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.M., et al., The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic scenario in Africa: What should be done to address the needs of pregnant women? Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2020. 151(3): p. 468-470. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S., M.J. Ponsford, and D. Gill, Are we underestimating seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2? BMJ, 2020. 370: p. m3364. [CrossRef]

- Bergeri, I., et al., Global SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence from January 2020 to April 2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis of standardized population-based studies. PLoS Med, 2022. 19(11): p. e1004107. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H.C., et al., SARS-CoV-2 infection in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of standardised seroprevalence studies, from January 2020 to December 2021. BMJ Glob Health, 2022. 7(8). [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.-D.; Dieng, M.; Faye, F.; Diaw, P.; Kempf, C.; Berthe, A.; Diop, M.; Martinot, M.; Diop, S. Demographics and outcomes of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases during the first epidemic wave in Senegal. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 52, 44–46. [CrossRef]

- Senkyire, E.K.; Ewetan, O.; Azuh, D.; Asiedua, E.; White, R.; Dunlea, M.; Barger, M.; Ohaja, M. An integrative literature review on the impact of COVID-19 on maternal and child health in Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Dia, N., et al., COVID-19 Outbreak, Senegal, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis, 2020. 26(11): p. 2772-2774. [CrossRef]

- Kasolo, F.; Yoti, Z.; Bakyaita, N.; Gaturuku, P.; Katz, R.; Fischer, J.E.; Perry, H.N. IDSR as a Platform for Implementing IHR in African Countries. Biosecurity Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strat. Pr. Sci. 2013, 11, 163–169. [CrossRef]

- Action, S.M.o.H.a.S., Week1-Week52, prevention, editor. Ministry of Health, in Surveillance Weekly Bulletin. 2020.

- Seck, O., et al., SARS-CoV-2 case detection using community event-based surveillance system-February-September 2020: lessons learned from Senegal. BMJ Glob Health, 2023. 8(6). [CrossRef]

- Health Emergency Operation Center., Standard Operation Procedures manual for COVID-19 outbreak response. 2020, Ministry of Health and Social Action.

- World Health Organization., Global Surveillance for human infection with coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2020.

- Diarra, M., et al., Analysis of contact tracing data showed contribution of asymptomatic and non-severe infections to the maintenance of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in Senegal. Sci Rep, 2023. 13(1): p. 9121. [CrossRef]

- Ahouidi, A.D., et al., Emergence of novel combinations of SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain variants in Senegal. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 23644. [CrossRef]

- Diarra, M.; Kebir, A.; Talla, C.; Barry, A.; Faye, J.; Louati, D.; Opatowski, L.; Diop, M.; White, L.J.; Loucoubar, C.; et al. Non-pharmaceutical interventions and COVID-19 vaccination strategies in Senegal: a modelling study. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2022, 7, e007236. [CrossRef]

- Senegalese Ministry of Health and Social Action., [Final report of the 2nd seroprevalence survey of Covid-19 in Senegal]. 2023.

- Afzal, A. Molecular diagnostic technologies for COVID-19: Limitations and challenges. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 26, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Hristov, D.R., et al., SARS-CoV-2 and approaches for a testing and diagnostic strategy. J Mater Chem B, 2021. 9(39): p. 8157-8173. [CrossRef]

- van den Beld, M.J.C., et al., Increasing the Efficiency of a National Laboratory Response to COVID-19: a Nationwide Multicenter Evaluation of 47 Commercial SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassays by 41 Laboratories. J Clin Microbiol, 2021. 59(9): p. e0076721. [CrossRef]

- Wapm Working Group on COVID., Maternal and perinatal outcomes of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2021. 57(2): p. 232-241. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, L.D., et al., Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(44): p. 1641-1647. [CrossRef]

- Allotey, J.; Stallings, E.; Bonet, M.; Yap, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Kew, T.; Debenham, L.; Llavall, A.C.; Dixit, A.; Zhou, D.; et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: Living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 370, m3320. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khalil, A., et al., SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical features and pregnancy outcomes. EClinicalMedicine, 2020. 25: p. 100446. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Makvandi, S.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of COVID-19 on Mortality of Pregnant and Postpartum Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pregnancy 2021, 2021, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Augusto, O.; Roberton, T.; Fernandes, Q.; Chicumbe, S.; Manhiça, I.; Tembe, S.; Wagenaar, B.H.; Anselmi, L.; Wakefield, J.; Sherr, K. Early effects of COVID-19 on maternal and child health service disruption in Mozambique. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1075691. [CrossRef]

- DeBolt, C.A.; Bianco, A.; Limaye, M.A.; Silverstein, J.; Penfield, C.A.; Roman, A.S.; Rosenberg, H.M.; Ferrara, L.; Lambert, C.; Khoury, R.; et al. Pregnant women with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 have increased composite morbidity compared with nonpregnant matched controls. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 510.e1–510.e12. [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, D., et al., Risk factors associated with adverse fetal outcomes in pregnancies affected by Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a secondary analysis of the WAPM study on COVID-19. J Perinat Med, 2020. 48(9): p. 950-958. [CrossRef]

- Villalain, C., et al., Seroprevalence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women along the first pandemic outbreak and perinatal outcome. PLoS One, 2020. 15(11): p. e0243029. [CrossRef]

- Diouara, A.A.M.; Lo, S.; Nguer, C.M.; Senghor, A.; Ndiaye, H.D.; Manga, N.M.; Danfakha, F.; Diallo, S.; Dieme, M.E.F.; Thiam, O.; et al. Hepatitis E Virus Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Consultations in Senegal. Viruses 2022, 14, 1742. [CrossRef]

- Wantai, WANTAI SARS-CoV-2 Ab ELISA: ELISA for Total Antibody to SARS-CoV-2.

- Molenaar, N.M., et al., SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy and associated outcomes: Results from an ongoing prospective cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2022. 36(4): p. 466-475. [CrossRef]

- Talla, C., et al., Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Senegal: a national population-based cross-sectional survey, between October and November 2020. IJID Reg, 2022. 3: p. 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Ahouidi, A.D., et al., Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in a healthcare setting during the first pandemic wave in Senegal. IJID Reg, 2022. 2: p. 96-98. [CrossRef]

- Seck, S.M., et al., Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in hemodialysis patients in Senegal: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol, 2021. 22(1): p. 384. [CrossRef]

- ANSD, [Senegal : Continuous Demographic and Health Survey (DHS-continue 2019)]. Rockville, Maryland, USA : ANSD et ICF., 2019.

- Benn, C.S., et al., SARS-CoV-2 serosurvey among adults involved in healthcare and health research in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Public Health, 2022. 203: p. 19-22. [CrossRef]

- Dutschke, A., et al., SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among people living with HIV in Guinea-Bissau. Public Health, 2022. 209: p. 36-38. [CrossRef]

- Soumah, A.A.; Diallo, M.S.K.; Guichet, E.; Maman, D.; Thaurignac, G.; Keita, A.K.; Bouillin, J.; Diallo, H.; Pelloquin, R.; Ayouba, A.; et al. High and Rapid Increase in Seroprevalence for SARS-CoV-2 in Conakry, Guinea: Results From 3 Successive Cross-Sectional Surveys (ANRS COV16-ARIACOV). Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac152. [CrossRef]

- Wajnberg, A., et al., Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science, 2020. 370(6521): p. 1227-1230. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A.J.S., et al., COVID-19 in 16 West African Countries: An Assessment of the Epidemiology and Genetic Diversity of SARS-CoV-2 after Four Epidemic Waves. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bassene, H.; Sambou, M.; Bedetto, M.; Colson, P.; Mediannikov, O.; Goumballa, N.; Diatta, G.; Gautret, P.; Fenollar, F.; Sokhna, C. Contribution of point-of-care laboratories in the molecular diagnosis and monitoring of COVID-19 in Niakhar, Dielmo and Ndiop rural areas in Senegal. New Microbes New Infect. 2023, 53, 101115. [CrossRef]

- Self, W.H., et al., Decline in SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies After Mild Infection Among Frontline Health Care Personnel in a Multistate Hospital Network - 12 States, April-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(47): p. 1762-1766. [CrossRef]

- Selvavinayagam, S.T., et al., Factors Associated With the Decay of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgG Antibodies Among Recipients of an Adenoviral Vector-Based AZD1222 and a Whole-Virion Inactivated BBV152 Vaccine. Front Med (Lausanne), 2022. 9: p. 887974. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S., et al., Evaluation of 6 Commercial SARS-CoV-2 Serology Assays Detecting Different Antibodies for Clinical Testing and Serosurveillance. Open Forum Infect Dis, 2021. 8(7): p. ofab239. [CrossRef]

- Herroelen, P.H., et al., Humoral Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2. Am J Clin Pathol, 2020. 154(5): p. 610-619. [CrossRef]

- Janha, R.E., et al., SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in pregnant women during the first three COVID-19 waves in The Gambia. Int J Infect Dis, 2023. 135: p. 109-117. [CrossRef]

- Herroelen, P.H., et al., Humoral Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2. Am J Clin Pathol, 2020. 154(5): p. 610-619. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).