1. Introduction

The great advance of 3D printing systems using fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology has allowed its use in a variety of areas thanks to its ability to produce parts of great geometric complexity in a relatively fast, easy and economical way, reducing the number of processing stages. In addition, it allows the use of different thermoplastic materials, such as polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) or polyether ether ketone (PEEK), with minimal change of components and configuration.

To allow the use of this technology in certain applications with thermal requirements, a critical property is the thermal conductivity of the model, which may vary depending on: the amount of air inside the part [

1]; the material used [

1,

2,

3,

4]; the direction of heat flow with respect to the printing direction [

5,

6,

7]; sintering or post-treatment in filaments including metallic particles [

8].

The addition of copper particles can significantly increase thermal conductivity [

2], especially with contents greater than 20% by mass, going from a conductivity of 0.12 W m

-1 K

-1 with a pure PLA sample to 0.35 W m

-1 K

-1with a copper particle content of 40% by mass. In addition, it is verified that adding 20% by mass of Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) particles enhances this increase in conductivity, increasing by 43% with respect to the same material without PMMA and reaching a conductivity of 0.49 W m

-1 K

-1.

Laureto et al [

1] in turn analyzes the effect of the addition of particles of different metals and compares it with the Lichtenecker equation, which predicts the conductivity of the material as a function of the conductivity of the polymer matrix and the concentration in volume and conductivity of the metal particles. Likewise, it studies the effect of the porosity of the material, concluding that it is necessary to minimize the air content and maximize the amount of metal particles to increase thermal conductivity.

In addition, referring to additive manufacturing using fused deposition technology, articles can be found in which the inclusion of carbon fibers is used to improve thermal conductivity. Ibrahim et al [

4] analyses the variation of the conductivity of a nylon matrix sample, with different layer configurations and fiber directions, obtaining the maximum conductivity with fibers in the direction of heat flow and reaching a conductivity 11 times higher than that of the base material.

In the case of post-processing like sintering of materials with copper particles, the thermal conductivity can be strongly increased, as Ebrahimi et al [

8] analyzed. Starting with a material whose average volume content is 39.3% and its conductivity is 1.5 W/K·m, it increases the copper concentration to 42.3% and reduces the porosity by sintering, getting a conductivity of 25.5 W/K·m.

In this context, different base polymer materials have been studied for comparison about thermal conductivity and their study about how 3D printing can influence in thermal capability. In this sense, an innovative filament composed of more than 65% metal and the rest by PLA has been studied with other different base polymer materials.

For thermal conductivity measurements a commercial bench used for metal components testing was adapted to enable high-confidence measurements on polymeric material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test bench

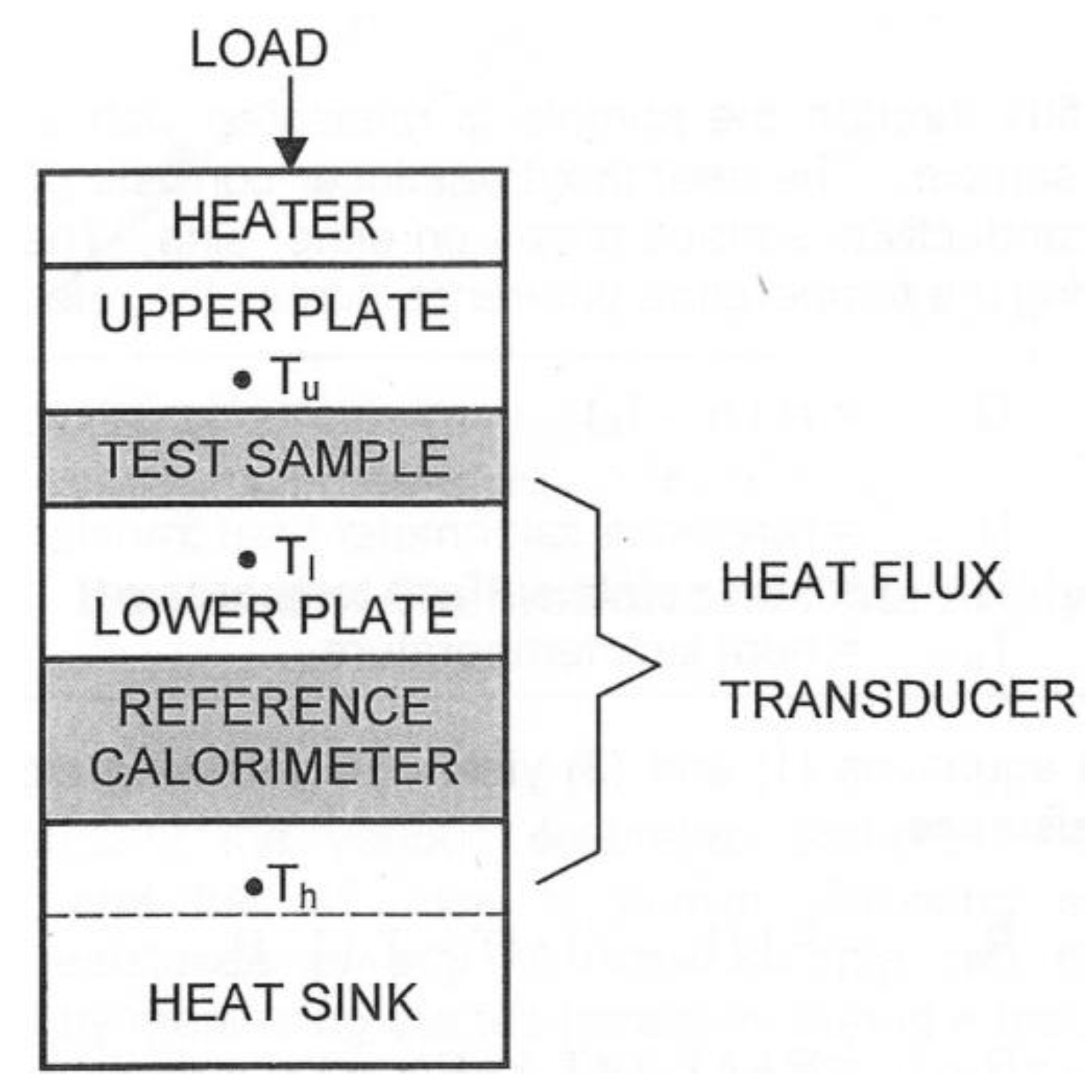

Commercial system acquired by the Public University of Navarre that consists of a thermal conductivity meter, DTC-25, as shown in

Figure 1, which, from the potential readings (V) and a post-processing allows to know the thermal resistance of the tested sample and the conductivity of the material. It is based on the protected heat flow method.

The measurement method, according to the ASTM E1530 specification [

10], consists of placing the study sample under pressure between two polished metal surfaces, where the upper one is temperature controlled and the lower one is connected to a liquid-cooled heat sink. After placing the piece, an axial temperature gradient is established through it, producing a flow of heat from the top to the heat sink, as shown in

Figure 2.

To obtain values with less uncertainty in the DTC-25, the hot focus temperature is set to 55°C and the cold focus temperature is set to 2°C. The hot focus is adjusted by means of an electrical resistance, while the cold focus temperature is controlled by means of a thermostatic bath. On the other hand, a pressurized nitrogen cylinder supplies the necessary pressure to move the actuator of the DTC-25 and exert pressure on the sample under study. A maximum pressure of 45 psi, 0.3 MPa, is exerted on the samples.

Once the test has been stabilized, the values shown on the bench display are processed by the manufacturer's own software, showing the thermal conductivity value of the sample being tested.

2.2. Samples

Seven different materials have been studied, to be classified according to the thermal conductivity obtained from the tests carried out in the DTC-25.

These are seven materials of different mechanical characteristics, of which it is necessary to know their thermal conductivity, to identify and discard utilities based on their thermal properties. One of the limitations of this measurement equipment is the pressure required to carry out the tests, on the DTC-25 test bench it is 0.3 MPa. Therefore, we have verified that all materials have higher maximum pressure limits, in the case of PEEK and PLA the maximum pressure limit is 0.45 MPa, and up to 67 MPa in the case of Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU). It is also necessary to control the temperature. As shown in

Table 1, the samples made with Filamet™ Aluminum 6061 and with a base material, PLA, limit their maximum temperature to 55ºC. These specimens cannot exceed the maximum temperature of the PLA, as the sample will lose its cohesion/integrity. In all the tests we have worked with temperatures below the limits.

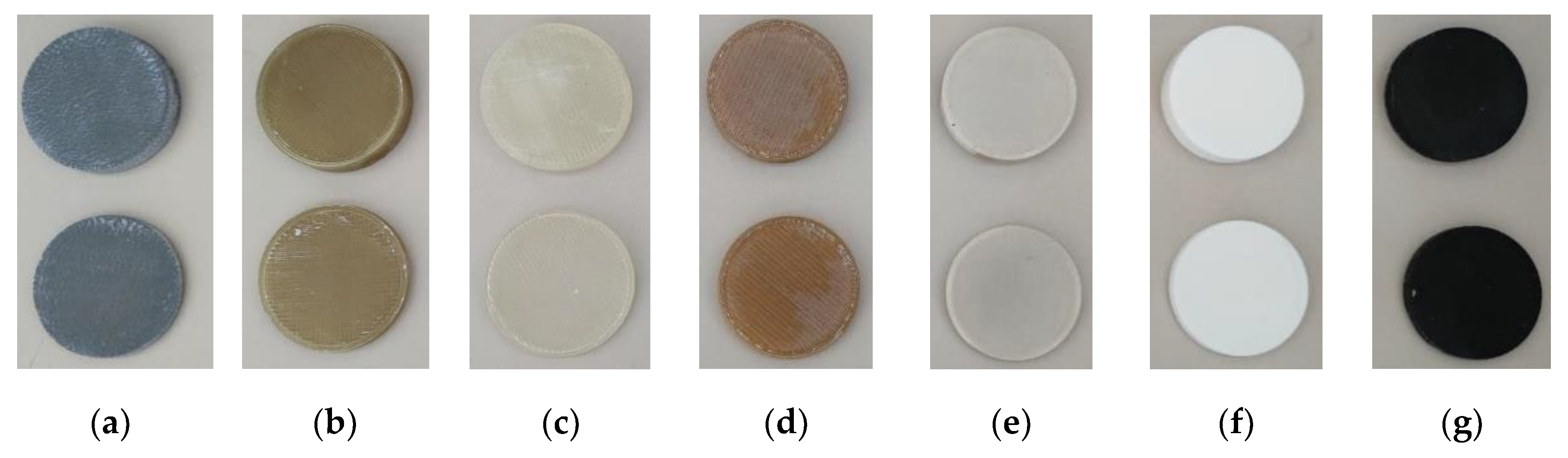

2.2.1. Geometry

Circular samples, shown in

Figure 3, were manufactured with a FDM printing with a standard diameter of 50 mm, and two different thicknesses, a first thickness of 5 mm and a second of 10 mm. Both diameter and thickness were accurately measured, as can see in

Table 2.

Different densities and fill patterns were produced using the different materials to get suitable mechanical [

18] and thermal capabilities. However, finally, a density of 100% and rectilinear fill pattern with an 45º angle offset was selected as the lowest porosity and the best mechanical behavior of them. Rest of the main parameters of the printing were: 0.8 nozzle diameter, 3.000 mm/min printing speed. 0.3 mm layer height, 1.75 mm filament diameter and between 210 and 270ºC printing temperature depending on the material. In addition, the surface finish of the samples was established between 1 to 10 microns depending on the material. It was necessary because together with the use of thermal contact paste, it allows the samples to be within the uncertainty of the bench, minimizing the influence of the thermal contact resistance between sample and equipment [

19].

3. Results

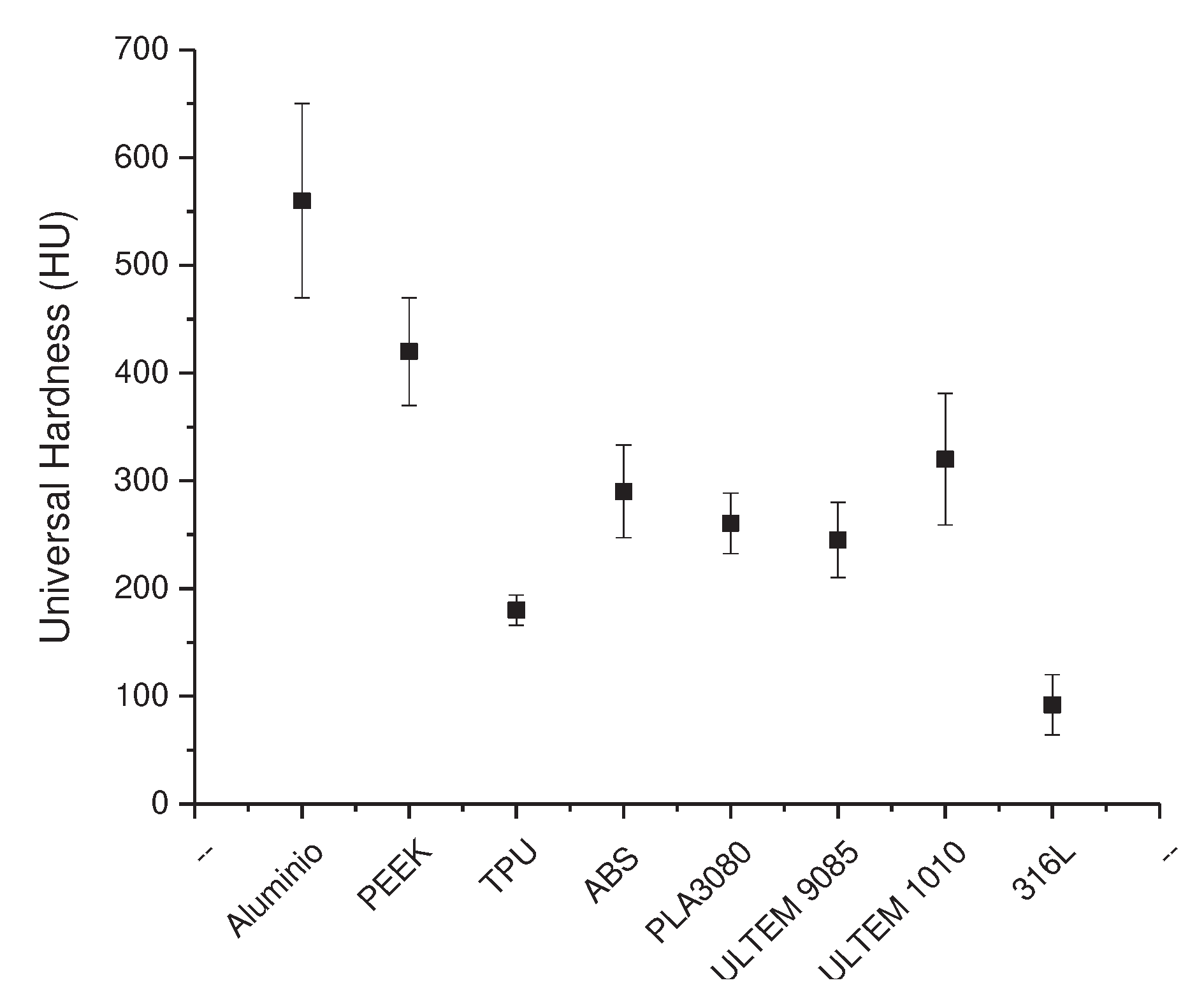

3.1. Hardness tests

An approximation of mechanical properties was studied by hardness tests [

20]. A universal hardness test was used for comparison between all samples in study. A maximum load of 1 N was applied. At least ten upload and download curves were studied for each material considering plastic and elastic deformation in the samples.

Figure 4 shows an average on universal hardness at maximum load.

The mechanical properties evaluated by universal hardness measurements showed values between 200 to 300 HU (Universal Hardness). Only PEEK was around 400 HU and aluminum showed values up to 550 HU.

3.2. Data acquisition

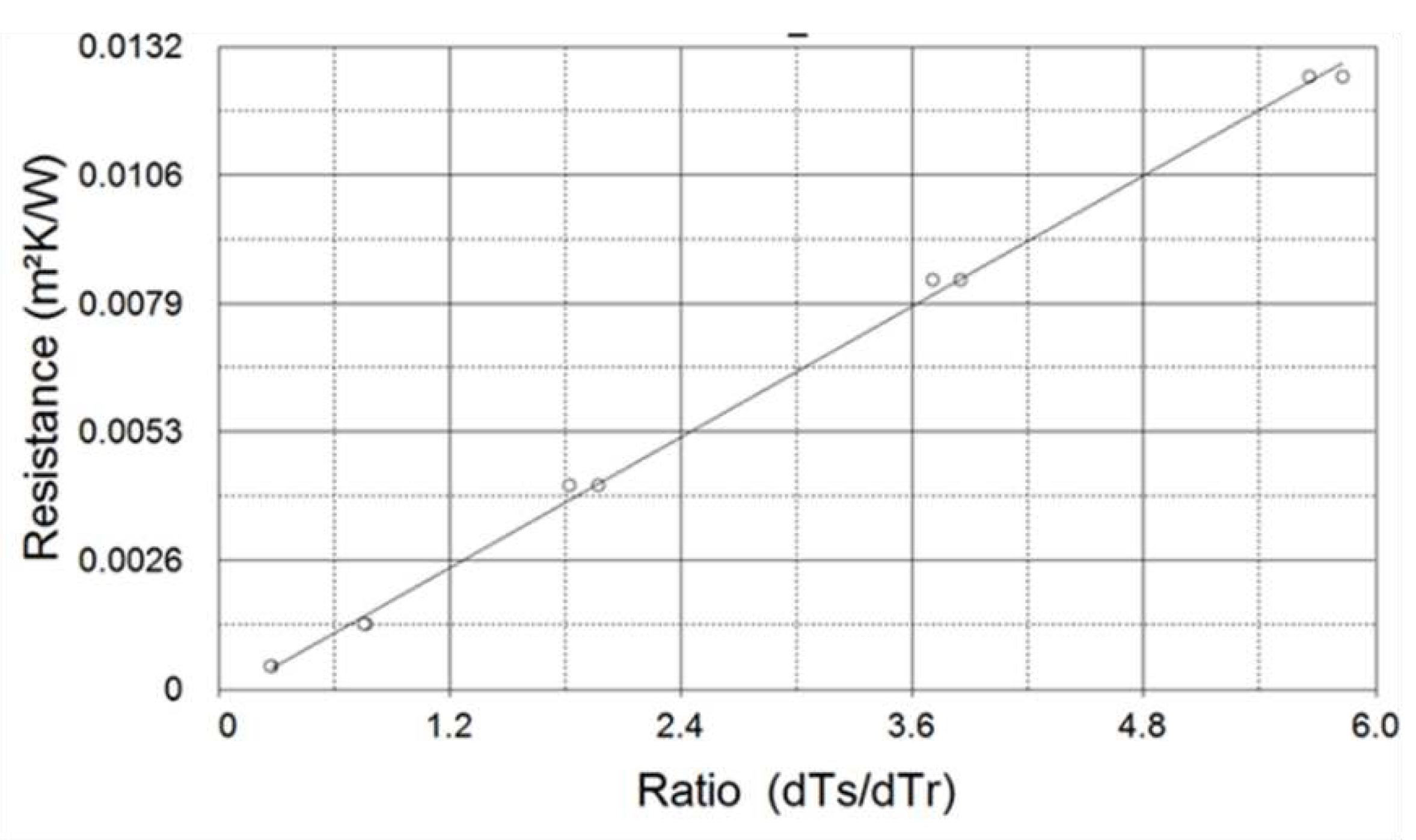

To obtain results faithful to the measurement of the piece, a calibration of the system must be carried out (

Figure 5). To do this, the five standards provided by the manufacturer are tested, and the calibration line is carried out using the system software with the potential measurements taken for each standard after its study once stabilized. The temperature values measured by the respective probes are shown in voltage values, it is these values that will be entered into the system software for the calculation of the thermal conductivity value of the sample.

In order to obtain more points on the calibration line, two studies are carried out on each pattern. In this way different calibration measurements are obtained because despite being the same piece tested, the results may differ slightly affected by the system itself, by the thermal paste used for the contact, the environment (measurement deviation).

3.2.1. Stability criterion

The stabilization in the DTC-25 conductivity meter is carried out according to experience, it is related to the thickness of the study specimen, because for greater thicknesses, since they have been tested materials of high thermal resistance, a longer study time will be required (

Table 3).

3.2.2. Uncertainty

The measurements have been made within the limits set by the manufacturer, so that it is within the reproducibility and uncertainty values provided, for this purpose, work is carried out within the ranges of thickness, size and minimum conductivity of the sample indicated in the technical data sheet. DTC-25: 50 mm diameter, sample thickness greater than 0.1 mm and theoretical conductivity between 0.1 and 20 W/m K.

To obtain an uncertainty value, we consider the randomness in the thermal conductivity measurements, performing N=6 tests for each material studied. The mean value

of these samples are obtained by equation 1.

And the standard uncertainty u (k) of the thermal conductivity k shown in equation 2 is calculated in a similar way to the one shown in [

21].

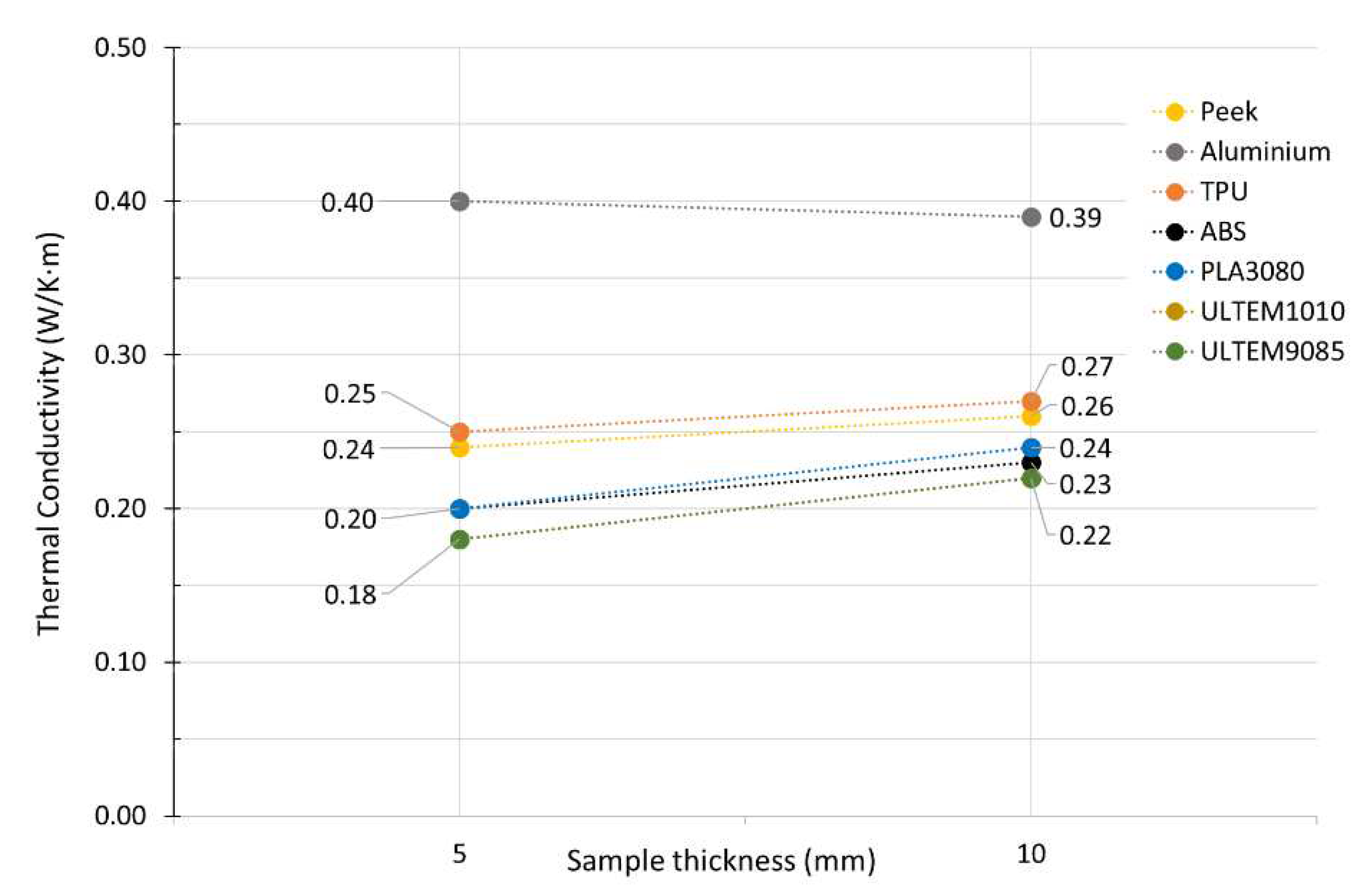

3.3. Thermal conductivity tests

The thermal conductivity values obtained for each thickness and material are shown in Figure 6, based on the results calculated by the DTC-25 bench software after entering the voltage readings (V) of each test.

Figure 5.

Calibration line. DTC-25. Two measurements per standard.

Figure 5.

Calibration line. DTC-25. Two measurements per standard.

In

Table 4, we can see the results obtained of average thermal conductivity with its measurement uncertainty. The material with the highest value is the Filamet™ of Aluminum 6061 of The Virtual Foundry (TVF), an innovative filament composed of more than 65% metal and the rest by PLA, with a conductivity of 0.40 W/m·K. It is followed by the TPU, a thermoplastic polyurethane that combines hardness, elasticity and mechanical resistance, so it maintains all the advantages of this elastomer to be able to manufacture completely rigid parts, with a conductivity of 0.26 W/m·K.

This aluminum alloy, whose conductivity stands out among the rest of the materials used in FDM, arouses interest, above all, with what may happen with its conductivity after sintering (elimination of PLA from the alloy). The rest of the materials are within the thermal conductivity standard of thermoplastics as it is shown in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

By comparing the results obtained in this study with the research conducted by M. C. Vu et al [

2], which examined the thermal conductivity of polylactic acid (PLA) composites with different copper (Cu) concentrations, we can draw several findings regarding the impact of metal inclusions on thermal performance. The study by Vu et al. [

2] demonstrated that for materials containing 100% PLA, the thermal conductivity was 0.12 W/m-K. As the mass percentage of Cu surpassed 20%, a notable enhancement in thermal conductivity to 0.35 W/m-K was achieved. This enhancement is ascribed to copper's intrinsically high thermal conductivity. The outcomes of this research align with those of Vu et al [

2], wherein the same effect was observed when materials comprising more than 65% Al were examined in combination with PLA. A noteworthy advancement in thermal conductivity was achieved, exhibiting a value of 0.40 W/m-K. Notably, aluminum is acknowledged to have a slightly inferior thermal conductivity in comparison to copper despite being an excellent heat conductor. Hence, the observation that metallic composites with a considerable mass fraction of aluminum exceeded those with higher copper proportion accentuates the significance of optimizing the metallic inclusions' mass percentages.

It is important to consider that thermal conductivity is influenced by factors beyond the presence of metallic inclusions, including the material's porosity. This point was emphasized in the study by Laureto et al [

1], which highlights the importance of reducing air content and increasing metal particle content to enhance thermal conductivity. The significance of design and precise material control during the FDM process is further emphasized to prevent porosity from adversely impacting the final product's heat transfer capabilities.

The comparison of Filamet™ Aluminum 6061 filament with other materials, including TPU, ABS, PEEK, PLA3080, ULTEM1010, and ULTEM9085, provides valuable insights into these materials' thermal properties. Filamet™ Aluminum 6061 demonstrates remarkable thermal conductivity of 0.40 ± 0.05 W/m-K. This innovative filament, which comprises more than 65% metal and PLA, exhibits excellent potential for achieving superior thermal performance using high-metal materials, as previously mentioned.

Conversely, TPU, a thermoplastic polyurethane, exhibits an acceptable thermal conductivity of 0.26 ± 0.05 W/m-K. This thermoplastic material exemplifies its aptness in situations calling for a combination of mechanical strength and thermal properties due to its elasticity and mechanical robustness.

The thermal conductivity of the remaining materials, ABS, PEEK, PLA3080, ULTEM1010 and ULTEM9085, were all within the expected range for thermoplastics. These materials can now be used as a benchmark for the thermal behavior of FDM materials.

This study's findings are of great importance to research on additive manufacturing, particularly to those involved with FDM-based 3D printing. This research significantly contributes to our understanding of the impact of various factors such as metal inclusions and material choices, on the thermal conductivity of FDM printed components.

This study could provide a valuable foundation for further research. Specifically, it would be worthwhile to investigate the impact of sintering, as explored by Ebrahimi et al [

8], on materials that contain metallic particles, like Filamet™ 6061 aluminium. This could offer insights into how post-processing techniques may enhance the thermal properties of FDM printed materials. Additionally, this research has implications beyond the materials under examination. Applications of FDM 3D printing in various fields, such as aerospace, automotive, and electronics, may benefit from using materials with customized thermal properties. Thus, investigating the integration of these materials in specific applications could enlighten their potential for thermal management.

5. Conclusions

The rapid expansion and cost-effectiveness of additive manufacturing technologies, particularly fused deposition modelling (FDM), have significantly altered materials development for various applications, including the automotive industry. FDM enables the production of intricate parts with fewer processing steps, providing a versatile and economical solution for numerous industries. The thermal conductivity of materials used in additive manufacturing is critical for applications with thermal requirements. Several factors have been documented to influence thermal conductivity, including air presence within parts, material type, heat flow direction, and post-treatments that impact metal particles. Controlling thermal conductivity is crucial in optimizing the performance of these materials.

In this study, the thermal conductivity of seven materials with varying mechanical and thermal properties was analyzed. It should be highlighted that Filamet™ Aluminum 6061 exhibited superior performance for high-temperature applications. The findings of this research can be used as a reference for selecting suitable materials in additive manufacturing techniques. Highly precise measurements were obtained utilizing a commercially available DTC-25 thermal conductivity measurement bench, adapted particularly for polymeric materials. The system's stability, uncertainty and calibration procedures were meticulously considered, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of the results.

It can additionally be concluded that the inclusion of metallic particles in thermoplastic materials leads to a significant improvement of their thermal conductivity. Our research findings demonstrate that materials like Filamet™ 6061 Aluminum, which contain over 65% metal and the rest PLA, exhibit high thermal conductivity, boasting a value of 0.40 ± 0.05 W/m-K. Compared to other materials, such as TPU, which is renowned for its mechanical and thermal resistance, with a thermal conductivity of 0.26 ± 0.05 W/m-K, Filamet™ 6061 Aluminum proves to be a more thermally efficient option. Consequently, the outcomes of this investigation highlight the potential benefits of integrating metallic inclusions to enhance thermal performance.

It is important to note that the type and concentration of metallic particles have a substantial impact on thermal conductivity. Our research agrees with previous studies, highlighting that elevated concentrations of metallic particles result in increased thermal conductivity. For instance, it has been demonstrated that copper particles with a concentration exceeding 20% resulted in a significant enhancement of thermal conductivity. It has been observed that reducing the air content within the material also enhances thermal conductivity. To minimize porosity, sintering processes or post-processing can be executed, similar to the copper particle-containing materials studied.

Additionally, the inclusion of carbon fibers can further enhance thermal conductivity, although it is crucial to consider the fibers’ orientation and configuration. It has been determined that orientating fibers in the direction of heat flow leads to a noteworthy enhancement in thermal performance.

The research demonstrates the significance of thermal conductivity in additive manufacturing. It provides valuable insights into the impact of metal inclusions, particle types, and concentrations on thermal performance. Filamet™ Aluminium 6061 exhibits exceptional thermal conductivity, which merits investigation for high thermal requirement industrial applications. This paper adds to the continual progression of materials employed in additive manufacturing by promoting the selection of materials to meet specific thermal requirements.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the Department of Economic and Business Development of Navarre Government, for economic support to this work, included in R&D projects in 2020 under research project acronym FORM3D (file codes: 0011-1365-2020-000084 and 0011-1365-2020-000127).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Laureto, J.; Tomasi, J.; King, J.A.; Pearce, J.M. Thermal properties of 3-D printed polylactic acid-metal composites. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 2 (1–2), 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.C.; Jeong, T.H.; Kim, J.B.; Choi, W.K.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.R. 3D printing of copper particles and poly (methyl methacrylate) beads containing poly (lactic acid) composites for enhancing thermomechanical properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138(5), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmeskal, O.; Marackova, L.; Lapcikova, T.; Mencik, P.; Prikryl, R. Thermal properties of samples prepared from polylactic acid by 3D printing. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2305. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Elkholy, A.; Schofield, J.S.; Melenka, G.W.; Kempers, R. Effective thermal conductivity of 3D-printed continuous fiber polymer composites. Adv. Manuf. Polym. Compos. Sci. 2020, 6(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemelya, C.; De La Rosa, A.; Torrado, A.R.; Yu, K.; Domanowski, J.; Bonacuse, P.J.; Martin, R.E.; Juhasz, M.; Hurwitz, F.; Wicker, Brett, R.B. Anisotropy of thermal conductivity in 3D printed polymer matrix composites for space based cube satellites. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 16, pp. 186–196, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Smith M.; Kim, S.; Lambert, A.; Walde, Bougher, T. Hasser A.A.; M.; Lindahl J.; Mungale, K.; Kunc, V. Maximizing the Performance of a 3D Printed Heat Sink by Accounting for Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity During Filament Deposition. 18th IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2019.

- Prajapati, H.; Ravoori, D.; Woods, R.L.; Jain, A. Measurement of anisotropic thermal conductivity and inter-layer thermal contact resistance in polymer fused deposition modeling (FDM). Addit. Manuf. 2018, 21, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, N.D.; Ju, Y.S. Thermal conductivity of sintered copper samples prepared using 3D printing-compatible polymer composite filaments. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 24, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heat, G.; Test, F. Dtc-300 Thermal Conductivity Meter. 2011.

- ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Resistance to Thermal Transmission by the Guarded Heat Flow Meter Technique. (ASTM E1530-19), 2019.

- Filament2Print: Filament aluminio 6061. Available online: https://filament2print.com/es/metalicos/1030-filamet-aluminio-6061.html (accessed on 20 oct. 2023).

- 3DXTECH Advanced Materialsxtech.com: ThermaXTM PEEK 3D Printing Filament Physical. Available online: https://www.3dxtech.com/product/thermax-peek/?attribute_pa_diameter=1-75mm&attribute_pa_weight=250g&attribute_pa_color=natural (accessed on 20 oct. 2023).

- S. M. 3D Innovatefil: TPU Hardness. Available online: https://www.smartmaterials3d.com/innovatefil-tpu-hardness#/2-tamano-m_750g/11-color-true_black/26-diametro-175_mm (accessed Oct. 20, 2023).

- Fillamentum Manufacturing Czech s.r.o.: ABS Extrafill. Available online: https://fillamentum.com/collections/abs-extrafill-filament/ (accessed 20 oct. 2023).

- Fillamentum Manufacturing Czech s.r.o.: PLA Extrafill. Available online: https://fillamentum.com/collections/pla-extrafill-filament/ (accessed 20 oct. 2023).

- Stratasys: ULTEM 1010 Resin. Available online: https://www.stratasys.com/en/stratasysdirect/materials/thermoplastics/ultem/ultem-1010-resin/ (accessed on 20 oct. 2023).

- Stratasys: UltemTM 9085. Available online: https://www.stratasys.com/en/materials/materials-catalog/fdm-materials/ultem-9085/ (accessed on 20 oct. 2023).

- Böğrekci, İ.; Demircioğlu, P.; Sucuoğlu, H.S.; Turhanlar, O. The Effect of the Infill Type and Density on Hardness of 3d Printed Parts. International Journal of 3d Printing Technologies and Digital Industry. 2019, 3(3), 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chaidas, D.; Kitsakis, K.; Kechagias, J.; Maropoulos, S. The impact of temperature changing on surface roughness of FFF process. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Volume 161, 20th Innovative Manufacturing Engineering and Energy Conference (IManEE 2016) Kozani, Greece, (23–25 September 2016).

- Hanon, M. M.; Dobos, J.; Zsidai, L. The influence of 3D printing process parameters on the mechanical performance of PLA polymer and its correlation with hardness. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 54, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H. , Yang, P. Uncertainty analysis of linear vertical bending moment in model tests and numerical prediction. Mech. Syst. Sygnal Process. 2022, 178, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).