1. Introduction

The deposition of

α-synuclein aggregates (

α-syn) in different brain regions is a neuropathological hallmark that defines a group of a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative diseases known as the α-synucleinopathies. These include the Lewy body diseases (LBD) such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) which are characterized by the intraneuronal deposition of

α-syn in neuropathological lesions termed Lewy bodies (LB) and Lewy neurites (LN). In multiple system atrophy (MSA), a non-LBD α-synucleinopathy, the

α-syn is deposited in the oligodendrocytes as glial cytoplasmic inclusions [

1,

2,

3].

Clinical presentation of these α-synucleinopathies are believed to be preceded by the aggregation of

α-synuclein, and its occultic deposition which drives neuronal dysfunction followed by death. For instance, in PD, motor symptoms become apparent after the loss of nearly 60-80% of the dopaminergic neurons (DN) of the SNpc [

4], as well as nerve cell loss in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM), locus coereleus (LC) and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) [

5]. Thus, the early and differential diagnosis of these groups of NDDs advocate the development of in vivo imaging agents, which would not only enable an early diagnosis, but also the tracking of disease progression as well as the monitoring the efficacy of therapy.

With the aid of positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging agents with adequate affinity and pharmacokinetic properties could enable in vivo imaging of the

α-syn, when labeled with either positron or single-photon emitting radioisotopes for the respective modalities [

3].

The development of

α-syn tracers is faced with general pitfalls that characterize the development of brain tracers such as molar weight (MW). The brain uptake of ligands correlates inversely to the square root of its MW [

6]. Another factor is lipophilicity, which plays an increased role for the

α-syn tracers, since the location of

α-syn is majorly intraneuronal or intraglial. Therefore the tracers ought to be sufficiently lipophilic to partition both across the blood brain barrier (BBB) as well as the cell membrane [

7,

8]. However, the tracers should not be too lipophilic that brain clearance of the unspecifically bound brain tracers is compromised which complicates the kinetic modeling, quantification and the reproducibility [

2,

9].

Furthermore, the development of α-syn radiotracers is replete with its own unique problems. Unfortunately, α-syn usually co-localizes with other protein aggregates that are also present in other NDDs such as Aβ [

7] and tau [

10]. Hence, selectivity is a major challenge, since βeta-sheet stacking is a common pathway to the aggregation of proteins that results in similar β-pleated sheets common to the above protein aggregates. Therefore, the prospective tracer must bind to α-syn in the nanomolar range, if possible, even in the subnanomolar range. This is further complicated by the lower absolute concentration of α-syn compared to Aβ and tau [

2,

7,

8,

11].

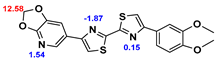

Despite the above mentioned limitations, several research groups are working at developing an ideal α-syn tracer with increasing success [

12,

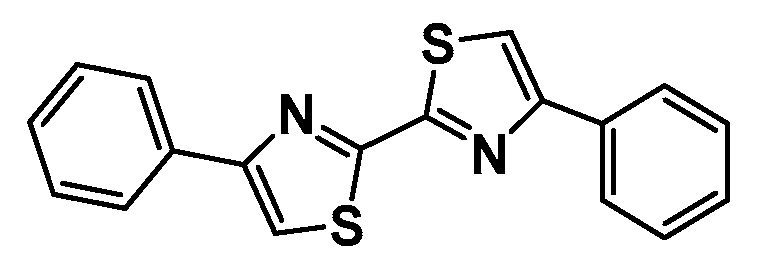

13]. Our contribution is based on a DABTA scaffold (

Figure 1). In an earlier collaboration with the theoretical coauthors of this paper, different DABTA derivatives with varied affinity to α-syn and selectivity over Aβ and tau were designed. To accomplish this multiple in silico modeling techniques were applied, such as molecular docking, MM/GBSA, free energy calculations, and metadynamics stimulation by which the interactions between the DABTAs and the fibrils (α-syn, Aβ, and tau) were studied [

1]. As a result, the advantages of some chemical moieties and functional groups were determined.

This present study focused on the lipophilicity and binding affinity of the DABTAs to α-syn, Aβ and tau as a function of their chemical moieties and functional groups.

2. Results

2.1. Chemical yields (CYs)

The CYs were moderate to high and reflected the success of the first step of the CYs in terms of semipreparative HPLC purification. The repeated synthesis also enabled the enactment of better purification strategies for a product (b) to be obtained in higher yields. The CYs of (b) obtained in the first synthesis step were provided in Supplementary information (SI).

Table 1.

Chemical yields (STEP II and Overall).

Table 1.

Chemical yields (STEP II and Overall).

| № |

DABTA |

Step I/II (overall), [%] |

Step III, [%] |

Overall yield, [%] |

| 1. |

d1 |

57.4 ± 0.91, (n = 2) |

- |

57.4 ± 0.91, (n = 2) |

| 2. |

d2 |

47.7 (n = 1) |

- |

47.7 (n = 1) |

| 3. |

d3 |

47.7 ± 3.23, (n = 3) |

- |

47.7 ± 3.23, (n = 3) |

| 4. |

d4 |

43.4, (n = 1) |

- |

43.4, (n = 1) |

| 5. |

d6 |

57.0, (n = 1) |

- |

57.0, (n = 1) |

| 6. |

d8 |

70.9 ± 1.63, (n = 3) |

- |

70.9 ± 1.63, (n = 3) |

| 7. |

d10 |

15.6, (n = 1) |

- |

15.6, (n = 1) |

| 8. |

d11 |

47.3 ± 3.11, (n = 2) |

- |

47.3 ± 2.28, (n = 2) |

| 9. |

d12 |

59.5 ± 2.28, (n = 8) |

- |

59.5 ± 2.28, (n = 8) |

| 10. |

d13 |

55.5, (n = 1) |

- |

55.5, (n = 1) |

| 11. |

d14 |

44.0, (n = 1) |

- |

44.0, (n = 1) |

| 12. |

d15 |

30.5, (n = 1) |

- |

30.5, (n = 1) |

| 13. |

d22 |

63.5, (n = 1) |

- |

63.5, (n = 1) |

| 14. |

f1 |

57.4 ± 0.91, (n = 2) |

58.0, (n = 1) |

33.3, (n = 1) |

| 15. |

f3 |

47.7 ± 3.23, (n = 3) |

58.0, (n = 1) |

27.7, (n = 1) |

| 16. |

f4 |

47.3 ± 2.28, (n = 2) |

85.9 ± 15.56, (n = 2) |

40.6 ± 7.37, (n = 2) |

| 17. |

f5 |

59.5 ± 2.28, (n = 8) |

89.3, (n = 1) |

53.1, (n = 1) |

| 18. |

f6 |

59.5 ± 2.28, (n = 8) |

77.5 ± 24.81, (n = 2) |

46.7 ± 14.98, (n = 2) |

| 17. |

f7 |

59.5 ± 2.28, (n = 8) |

84.9 ± 0.71, (n = 2) |

51.2 ± 0.43, (n = 2) |

| 18. |

f8 |

47.3 ± 2.28, (n = 2) |

82.0, (n = 1) |

38.8, (n = 1) |

| 19. |

f9 |

47.7 ± 3.23, (n = 3) |

54.3 ± 1.03, (n = 2) |

25.9 ± 0.49, (n = 2) |

| 20. |

f10 |

55.2, (n = 1) |

66.3 ± 4.94, (n = 2) |

36.6 ± 2.72, (n = 2) |

| 21. |

f11 |

42.0, (n = 1) |

91.1, (n = 1) |

38.3, (n = 1) |

| 22. |

f12 |

30.5, (n = 1) |

80.0, (n = 1) |

24.5, (n = 1) |

| 23. |

f13 |

47.3 ± 2.28, (n = 2) |

57.0, (n = 1) |

27.0, (n = 1) |

| 24. |

f14 |

57.4 ± 0.91, (n = 2) |

91.2, (n = 1) |

52.3, (n = 1) |

| 25. |

f15 |

59.5 ± 2.28, (n = 8) |

85.5, (n = 1) |

50.9, (n = 1) |

| 26. |

f16 |

57.4 ± 0.91, (n = 2) |

77.2, (n = 1) |

44.3, (n = 1) |

| 27. |

f17 |

30.5, (n = 1) |

96.4, (n = 1) |

29.4, (n = 1) |

| 28. |

f18 |

47.7 ± 3.23, (n = 3) |

87.0, (n = 1) |

41.4, (n = 1) |

| 29. |

f19 |

63.5, (n = 1) |

98.3, (n = 1) |

62.4, (n = 1) |

| 30. |

f20 |

63.5, (n = 1) |

95.2, (n = 1) |

60.1, (n = 1) |

| 31. |

h13 |

47.3 ± 2.28, (n = 2) |

80.7, (n = 1) |

38.2, (n = 1) |

| n: number of repetitions |

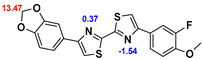

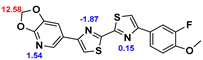

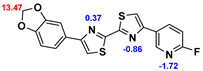

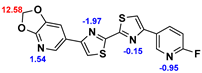

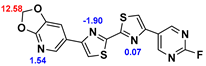

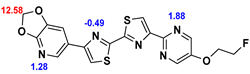

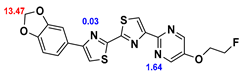

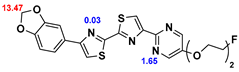

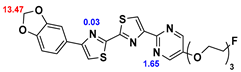

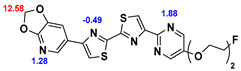

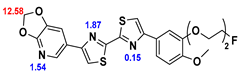

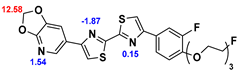

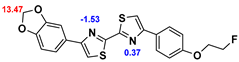

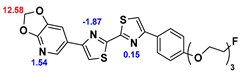

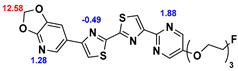

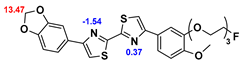

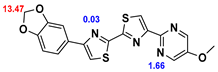

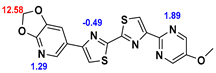

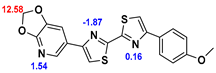

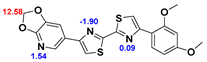

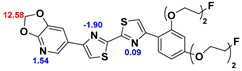

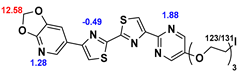

2.2. Competitive binding assays and clogP

All the reported DABTAs were sufficiently lipophilic with clogP between 2.5 and 5.7. As expected the DABTAs bearing the benzodioxole ring were more lipophilic than their [

1,

3]dioxolo[4,5-b]pyridine ring-containing analogues: d

4/d

2, d

8/d

6, d

21/d

19, f

4/f

5, f

8/f

6, f

13/f

7, and f

15/f

16.

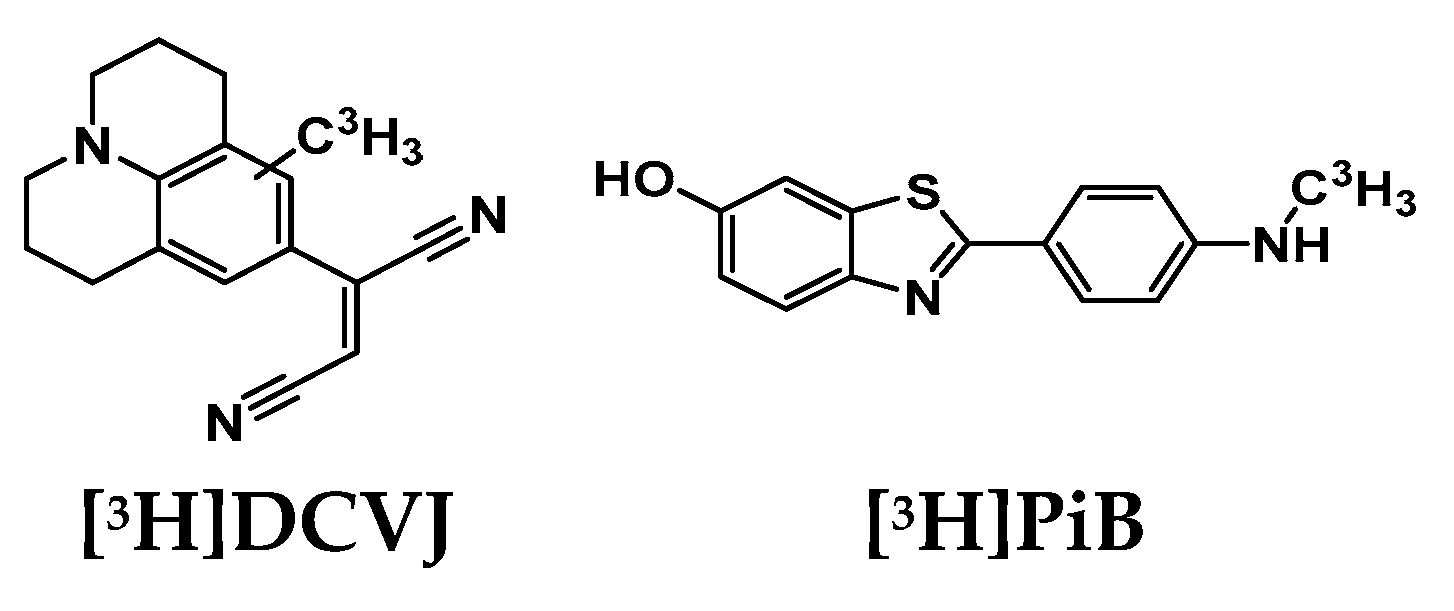

Although a high affinity to α-syn was maintained, the ligands showed varied affinity to protein aggregates depending on the ligand against which they were competing, which in this case were [

3H]DCVJ and [

3H]PiB. Using [

3H]DCVJ an interesting tendency was observed, namely that DABTAs that bear the [

1,

3]dioxolo[4,5-b]pyridine moiety showed higher affinity to α-syn than their benzodioxole-ring-bearing counterparts (

Table 2) except in the case of f

6. Although it contains no [

1,

3]dioxolo[4,5-b]pyridine ring it still showed subnanomolar affinity to α-syn. A property that could be attributed to the fluoroethylethoxy functional group it bears. In the case of [

3H]PiB, this tendency was also fairly consistent but there was reduced affinity and selectivity.

Due to the low solubility of f

8, f

16, f

18 and h

13 in the incubation solution, it was difficult to perform the binding assays with them: it was impossible with f

16 at any concentration; for f

8, f

18 and h

13, it was only possible at the low concentration of the ligands used for the α-syn binding assay (

Table 2).

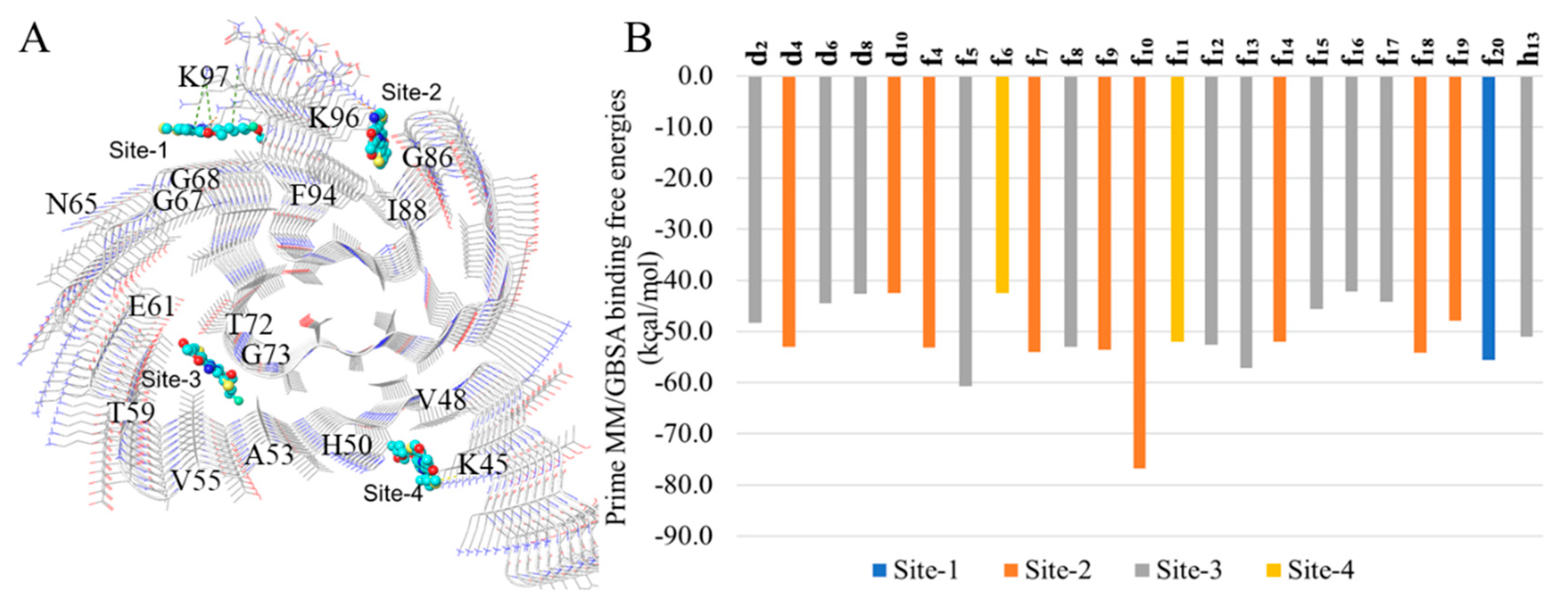

2.3. In-silico modeling of the binding of DABTAs to α-syn

We docked ligands

f4 to

f20 and

h13 to the binding sites (sites 1 - 4,

Figure 2A) identified from a previous study [

14], followed by prime MM/GBSA binding free energy calculations. The sites with the lowest binding free energies for each DABTA are reported in

Figure 2B, which shows that the DABTAs depending on the functional groups borne show varied preferences for the identified sites.

The three surface sites which are sites-1, -2 and -4 bear at least one basic amino acid residue. Interestingly, the DABTAs exhibit a very competitive preference for site-2 (7 compounds,

f4,

f7,

f9,

f10,

f14,

f18 and

f19) of all the surface sites compared to the inner cavity site-3 (8 compounds, see

Figure 2B), which is more similar to a conventional ligand binding pocket. Of the two DABTAs that bear two fluorine atoms, the more lipophilic (

Table 2)

f10 bound to site-2 with the highest binding free energy (-76.8 kcal/mol) observed in the DABTAs, while the more hydrophilic

f20 bound to site-1, actually the only DABTA that bound to this site, with 21.8 kcal/mol less energy. This was also demonstrated in the binding assays (

Table 2), in which, the K

i of

f10 to α-syn was roughly the same with both [

3H]DCVJ and [

3H]PiB. Notwithstanding, some of the evaluated DABTAs also showed a preference to the cavity site-3 over the other three (surface) sites.

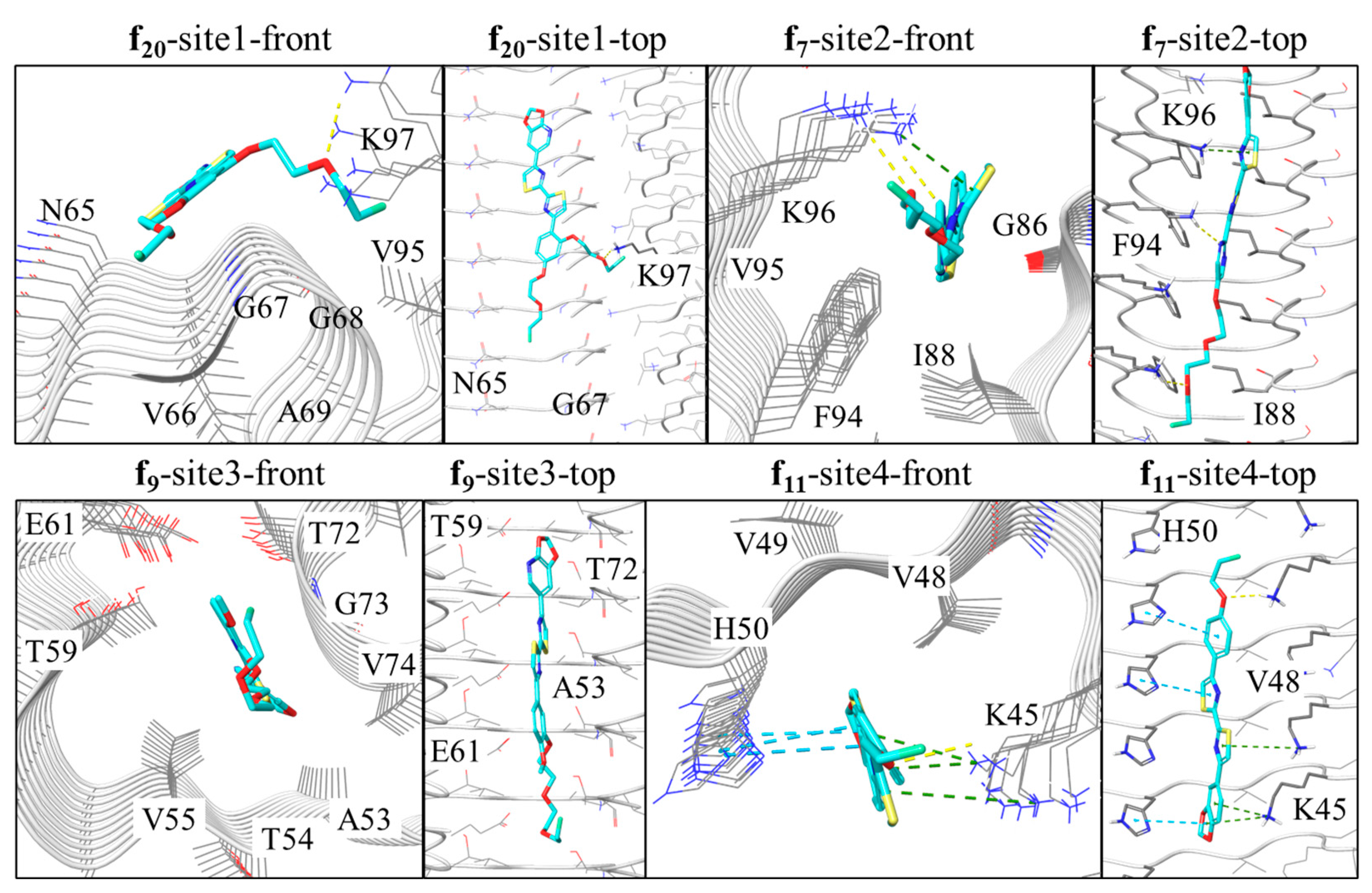

Analysis of the binding modes of the DABTAs as revealed by the docking experiments, it was seen that all the DABTAs adopted stretched modes with their axes parallel to that of the protofibril upon binding (

Figure 3). Such docking interaction mode has also been observed in other in silico studies carried out with ligands that bind to protofibrils from neurodegenerative diseases.

100-ns simulations were performed for each ligand bound to each docking-derived site (surface sites-1, -2 and -4 and the interior cavity site 3). From the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values, the mobility of ligands on the surface site was observed to be significantly larger than those in the cavity site (SI

Figure 4).

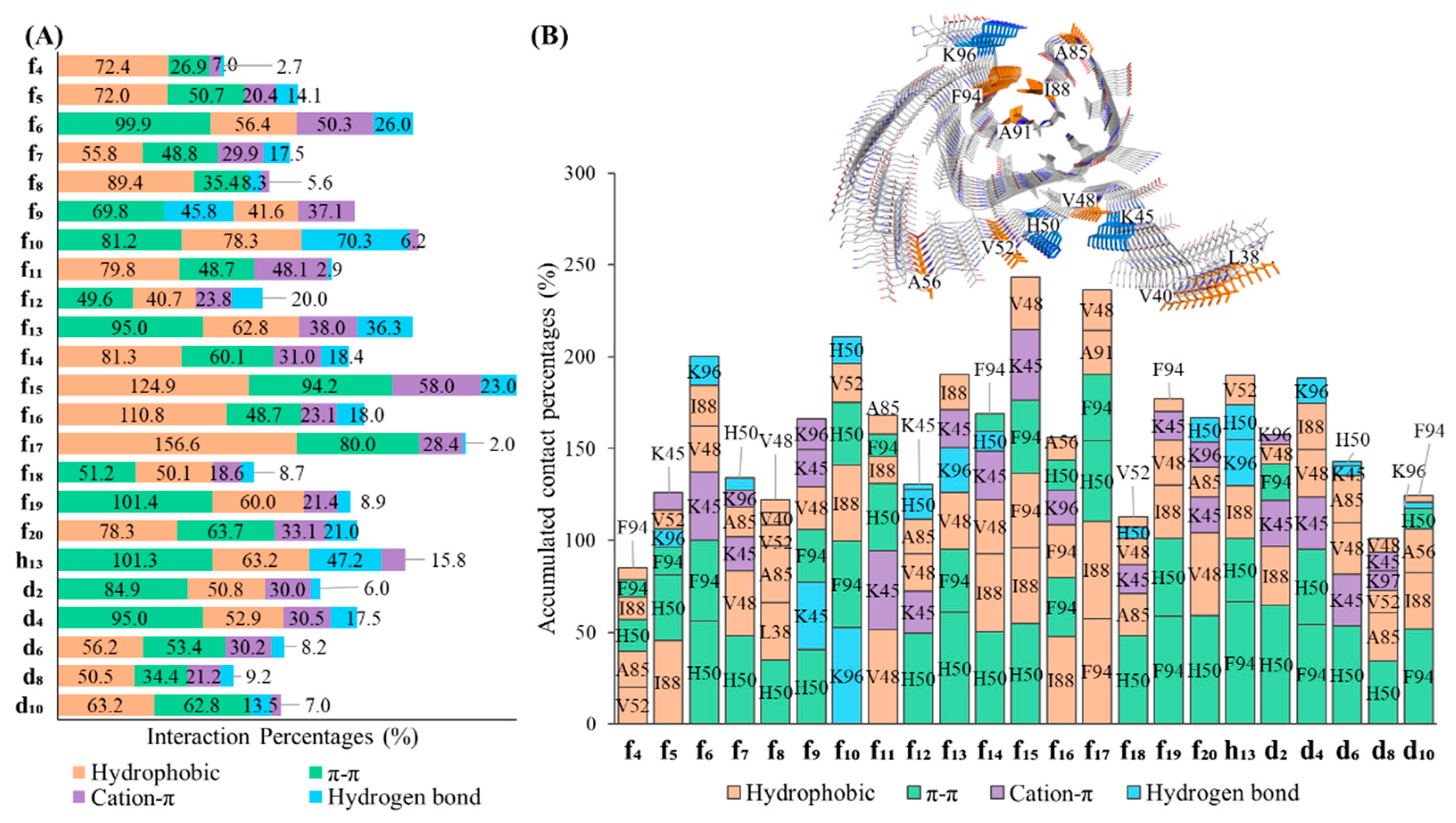

To determine the kind of interaction preferred by the DABTAs in their interactions with the surface sites of α-syn a simulation interaction analysis was carried out, in which it was discovered, that although all the DABTAs bear four aromatic rings, π-π interaction is not the main interaction in ten of the eighteen evaluated ligands (

Figure 4A). The overall accumulated percentages of interactions follow the order – hydrophobic interaction, π-π interaction, cation-π interaction, and hydrogen bonding from the trajectories of most ligands starting from the three surface sites.

In the MD simulations, where the interactions between the DABTAs and α-syn were narrowed down to the residues in the surface sites, it was clearly seen π-π interactions played an important role in the interaction of most of the DABTAs with the histidine (H50) and phenylalanine (F94) residues (

Figure 4B), which is hardly surprising since they are all bear aromatic and heteroaromatic rings. Hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues of hydrophobic such amino acids as I88, V48, V52, F94, and A85 were observed in the DABTAs (

f4,

f5,

f8, f10, f11,

f14,

f15,

f16,

f17, and

f20) with overall accumulated percentage over 70% (

Figure 4A)

.Unexpectedly,

f10 surpassed all the DABTAs with respect to hydrogen bond interactions with lysine residues (K96) in the surface sites (sites-1, -2, and -4) of α-syn (

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B), while the DABTAs with a relatively high tPSA

f13 and

h13 performed poorly in this aspect.

Moreover, it was also interesting to observe that the majority of the pyridine-bearing DABTAs, which are expected to form stronger hydrogen bonds or did not live up to the expectation, but counterintuitively partook more in hydrophobic interactions in the simulations. Cation-π interaction was seen not only in the DABTAs bearing electron-rich aromatic rings with protonated lysine residues (K45), but also in those with only heteroaromatic rings such as f4, f13, and f16. The combination of high π-π/Cation-π interactions observed for these only-heteroaromatic-rings bearing DABTAs might have reduced their tendency to form hydrogen bonds or broken formed hydrogen bonds, since π-π/Cation-π interactions require specific angle between aromatic/heteroaromatic rings of the DABTAs and the corresponding amino acid residues.

3. Discussion

The strategies employed in the CY of the DABTAs were discussed in detail in a previous publication [

1]. Nevertheless, care was taken to obtain the intermediates, that is, the 4-aryl/heteroarylthiazole-2-carbothioamides in high HPLC purity. This facilitated an easier purification of the more difficult-to-dissolve downstream products (d) and (f) (SI schemes 2 and 3).

The lipophilic profile of the ligands is reminiscent of that of some of the already reported ligands such as d

6 and d

8, which showed excellent brain uptake and washout [

1]. Even the ligands with relatively higher clogP made up for this by their high tPSA which might lower unspecific binding both on the periphery and in the brain. Also, replacing the left-side benzene ring with pyridine can reduce the lipophilicity as in the case of f

9/f

14. Although PEGylation helped in the reduction of lipophilicity (d

4/f

10), a more significant reduction was observed by replacing the benzene ring with a pyrimidine ring as was the cases of f

5/f

11 and f

12/f

13. The pyrimidine ring in the fluoroethyl/PEGylated DABTAs were placed in such a way that minimizes the formation of hydrogen bonds with its aqueous environment thus facilitating brain permeability of the tracers. At an overall level, the hydrophilicity of the DABTAs are relatively high, leading to the observation of hydrophobic and π-π interactions dominating the interactions between tracers and the solvent exposed surface sites (

Figure 4).

As already mentioned [

1], in preliminary binding assays it was established that the methylenedioxy group is essential for a high affinity to α-syn and selectivity over Aβ and tau. For this reason, this functional group is present in all the DABTAs. Furthermore, the ligands showed a functional group dependent affinity to α-syn and selectivity over Aβ and tau in the competitive binding assays especially with [

3H]DCVJ, in that, the more heterocyclic aromatic rings there are in the structure the higher the affinity to α-syn - good examples are d

2 and d

4; d

6 and d

8; f

4 and f

5; f

7 and f

13. This could be attributed to π–π interactions [

15,

16]. This tendency was slightly diminished using [

3H]PiB which might be partly explained by the contents of the incubation buffer used in this case, with which the ligands might have interacted. Moreover, the difference in binding sites on the protein aggregates might be another factor, which is reflected in the binding free energy calculations for different sites. The difficulty in matching the calculated free energies with the experimental K

i values can be related to different experimental and theoretical conditions. The low solubility of some of the DABTAs might have played a role in their ability to interact with the protein aggregates. The most interesting of these poorly soluble DABTAs is f

16, which in spite of its hydrophilic functional groups could not be dissolved in the incubation buffer for the binding experiments.

Computer simulation is a powerful tool which compensates for the insufficient experimental knowledge of the dynamic and atomic details of the binding of PET tracers to pathologically aggregated protein filaments. Although the binding of small molecules in the cavity site of lipidic α-syn can be observed by NMR spectroscopy [

17], the surface site in the fibril may still be more accessible to the ligands in-vivo, since the fibrils may twist themselves around each other, thus blocking the entrance to the cavity sites.

In this study, the surface site-2, which contains more than two aggregated residues, was found to be more preferred by the DABTAs compared to the cavity site 3 (

Figure 3B). Notably this was not observed in a current study of the interaction of some tau PET tracers with the surface sites of 4R tau protofibrils [

18]. The mobility of the DABTAs on the surface sites of α-syn are also less significant than other PET tracers on tau protofibrils [

18].

PEGylation can either lengthen the molecule, when it is added to the para-position of the benzene/pyrimidine ring or partially bifurcate the molecule when it is located on the meta- or ortho- position. From the interaction analysis, it was seen that the 2-3 repeat PEGylation at the para-position is beneficial for π–π interactions with H50 at site-4 or F94 at site-2 (f

6, f

13 and h

13 in

Figure 5). For instance, the three-repeat PEGylation at the para-position in f

13 seems to greatly enhance its affinity to α-syn (K

i 0.38 nM).

For the branched PEGylation with 3 repeats, the portion of hydrophobic interaction increased significantly (f

14 and f

20 in

Figure 4). The branched PEG moiety could hook some “pop-out” backbones area with the direction perpendicular to the axis of protofibril. For example, the PEG moiety at the meta-position was found to hook the “pop-out” area, which comprised G67, G68, and A69 (

Figure 4) and thereby increase the hydrophobic interactions during the MD simulations. However, the 2-repeat PEGylation at the meta-position increases hydrogen bonding with K45 for ligand f

9 (

Figure 4). Contact analysis based solely on the distances between any of the non-hydrogen atoms of the ligand and the protein for the surface sites 1, 2 and 4, showed that the best contact residue is N65 for all the ligands except f

6, f

7, f

13, f

15, f

19 and f

20, which mostly contacted with H50 (Figure 6. Although site-2 exhibits comparable binding free energies to the ligands with the cavity site-3, N65 makes more contacts, which correlated with smaller RMSD values for more ligands in site-1 than in site-2 (

Figure 3).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical synthesis

The synthesis of the DABTAs and the synthesis schemes are described in the supplementary information (SI).

4.2. In vitro binding assays

4.2.1. Preparation of the amyloid protein aggregates

4.2.1.1. Preparation of recombinant α-syn fibrils

The incubation of purified recombinant α-synuclein monomer (10 mg/mL) obtained as described by Uzuegbunam [

1,

19] was carried out in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C. The solution was left shaking at 900 r.p.m in an Eppendorf Thermomixer for up to 84 hours. Determination of the concentration of the formed fibrils (α-syn), was carried out following the centrifugation of the reaction vial at 12 000 g for 5 min. The pellet obtained was washed thrice with 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. The supernatants from the three centrifugation steps were combined and the concentration of the monomer in the resulting supernatant was determined in a BCA assay (with a BSA standard curve). Determination of the concentration of α-syn was carried out by subtracting the amount of α-synuclein monomer in the supernatant from the initial amount used for fibrillation.

4.2.1.2. Preparation of recombinant β-amyloid fibrils

After the dissolution of 1 mg β-amyloid1−42 peptide (Abcam, United Kingdom) (50 μL DMSO, 925 μL of Milli-Q® water was added to it and the mixture was stirred. Finally, 25 μL of 1M Tris HCl, pH 7.4 was added to bring the final peptide concentration to 1 mg/mL. The mixture was then left to incubate at 37°C for 30 h with shaking at 900 r.p.m. To separate the non-aggregated monomers from the formed fibrils, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 12 000 g for 5 min and the resulting pellet was washed three times with 500 μL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. The supernatants from the three centrifugation steps were combined and the concentration of the monomer in the resulting supernatant was determined in a BCA assay (with a BSA standard curve). Determination of the concentration of fibrils formed was carried out by subtracting the amount of β-amyloid1−42 peptide monomer in the supernatant from the initial amount used for fibrillation.

4.2.1.3. Preparation of recombinant tau fibrils

Recombinant tau monomer (R&D systems, U.S.A) was dissolved in 20 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 25 μM low MW heparin, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol to a final concentration of 300 µg/mL. The mixture was incubated with shaking 900 r.p.m at 37°C for 48 h. To separate the non-aggregated monomers from the formed fibrils, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 12 000 g for 5 min and the resulting pellet was washed three times with 500 μL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. The supernatants from the three centrifugation steps were combined and the concentration of the monomer in the resulting supernatant was determined in a BCA assay (with a BSA standard curve). Determination of the concentration of fibrils formed was carried out by subtracting the amount of tau peptide monomer in the supernatant from the initial amount used for fibrillation.

4.2.2. Preparation of α-synuclein, β-amyloid1−42, and tau fibrils for competition binding assays

The pellets of the fibrils obtained above (4.2.1) were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 and diluted as needed for the binding assays.

4.2.3. Competition binding assays

The binding assays were carried out with both tritiated DCVJ ([

3H]DCVJ) and tritiated PiB ([

3H]PiB) (

Figure 2). [

3H]DCVJ binds to all the protein aggregates with high affinity: K

d for α-syn 4.4 nM, Aβ 8.9 nM, tau 15.6 nM. [

3H]PiB with also relatively high affinity to the fibrils [

20,

21,

22]: K

d for α-syn 4.9 nM, Aβ 3.7 nM, tau 117.5 nM.

4.2.3.1. Competition binding assays with the α-syn fibrils

A fixed concentration of [3H]DCVJ (10 nM) and α-synuclein aggregates (125 nM) prepared as described above (4.2.3) was used with different final concentrations of the DABTAs from 0.01 - 100 nM. The experiment was carried out in quintuplicates for each concentration. The mixture was incubated for 2 h in a final volume of 200 μL per well after dilution with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. The incubated mixtures were filtered through a Perkin Elmer GF/B glass filter via a TOMTEC cell harvester and immediately washed thrice with 1 mL of deionized water. The filters containing the bound ligands were dried and afterwards mixed with 3 mL of BetaPlate Scint solution (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and left there for 2 h before counting in a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta TriLux Liquid Scintillation Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). For the determination of the inhibition constants, data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0) to obtain IC50 values by fitting the data to the equation Y = bottom + (top − bottom)/(1 + 10(x – log IC50)). Ki values were calculated from IC50 values using the equation Ki = IC50/(1 + [radioligand]/Kd). For assays with [3H]PiB, a fixed concentration of [3H]PiB (10 nM) and a 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% BSA (for incubation and washing) were used instead. Further protocol was carried out as for [3H]DCVJ.

4.2.3.2. Competition binding assays for Aβ1−42 and tau fibrils

Fixed concentrations (125 nM) of Aβ1−42, tau aggregates, and [3H]DCVJ (10 nM and 20 nM for the Aβ1−42 and Tau competition experiments respectively) were used with different concentrations of cold versions of the tracers from 1 - 1000 nM. The experiment was performed in quadruplicates for each concentration. Further procedures followed the same already described in 4.2.3.1.

For assays with [3H]PiB, fixed concentrations (125 nM) of Aβ1−42, tau aggregates, and [3H]PiB (10 nM and 200 nM for the Aβ1−42 and tau competition experiments respectively) with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) that contained 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% BSA (for incubation and washing) were used instead. Further procedures followed the same already described in 2.2.4.1.1.

5. Conclusions

The reported DABTAs showed impressive binding affinity to recombinant α-syn and selectivity over recombinant Aβ and tau in vitro. The binding details of these ligands to α-syn have been evaluated in detail with structure-activity relationships established in this paper. The introduction of 2-3 repeated PEGylation on the para-position of the benzene/pyrimidine ring was found to increase the binding affinities to α-syn as they facilitate increased π-π interactions. The lipophilicity of the newly reported ligands holds the promise of good brain pharmacokinetics. In order to further evaluate the efficacy of these ligands, they will be radiolabeled with either fluorine-18 or carbon-11 for further in vitro and in vivo studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

YBH and UBC: research project conception and chemistry. UBC: organization, execution, and analysis—design and execution. UBC, YBH, LJ, and ÅH: manuscript preparation—writing of the first draft. LJ and ÅH: in silico study. PW, SP, and UBC: binding experiments. UBC, YBH, JL, HÅ, WW, WP, and PS: review and critique. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Parkinsonfonds Deutschland (Grant Number: 1884). This study was also financially supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation, MJFF-019728, the Rainwater Charitable Foundation for the Tau consortium project: In silico development and in vitro characterization of PET tracers for 4R-tau. The computations were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Super-computing in Sweden (NAISS) at the National Supercomputer Centre at Linköping University (Sweden), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through Grant Agreement 2022-3-34.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the excellent support and assistance at the nuclear medicine department, TUM.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Uzuegbunam, B.C.; Li, J.; Paslawski, W.; Weber, W.; Svenningsson, P.; Ågren, H.; Yousefi, B.H. Toward Novel 18F-Fluorine-Labeled Radiotracers for the Imaging of α-Synuclein Fibrils. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 830704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdurand, M.; Levigoureux, E.; Lancelot, S.; Zeinyeh, W.; Billard, T.; Quadrio, I.; Perret-Liaudet, A.; Zimmer, L.; Chauveau, F. Amyloid-Beta Radiotracer 18F-BF-227 Does Not Bind to Cytoplasmic Glial Inclusions of Postmortem Multiple System Atrophy Brain Tissue. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2018, 2018, 9165458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdurand, M.; Levigoureux, E.; Zeinyeh, W.; Berthier, L.; Mendjel-Herda, M.; Cadarossanesaib, F.; Bouillot, C.; Iecker, T.; Terreux, R.; Lancelot, S.; et al. In Silico, in Vitro, and in Vivo Evaluation of New Candidates for α-Synuclein PET Imaging. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 3153–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Disease: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1831191-overview?icd=login_success_email_match_norm#a4 (accessed on 8 June 2023.891Z).

- Forno, L.S. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1996, 55, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, C.A.; Lopresti, B.J.; Ikonomovic, M.D.; Klunk, W.E. Small-molecule PET Tracers for Imaging Proteinopathies. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 2017, 47, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberling, J.L.; Dave, K.D.; Frasier, M.A. α-synuclein imaging: a critical need for Parkinson's disease research. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2013, 3, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïeb, D.; Hicks, R.J.; Hindié, E.; Guillet, B.A.; Avram, A.; Ghedini, P.; Timmers, H.J.; Scott, A.T.; Elojeimy, S.; Rubello, D.; et al. European Association of Nuclear Medicine Practice Guideline/Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Procedure Standard 2019 for radionuclide imaging of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 2112–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, D.J.; Grossman, M.; Weintraub, D.; Hurtig, H.I.; Duda, J.E.; Xie, S.X.; Lee, E.B.; van Deerlin, V.M.; Lopez, O.L.; Kofler, J.K.; et al. Neuropathological and genetic correlates of survival and dementia onset in synucleinopathies: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, D.P.; Yu, L.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Xu, J.; Mach, R.H.; Tu, Z.; Kotzbauer, P.T. Binding of the radioligand SIL23 to α-synuclein fibrils in Parkinson disease brain tissue establishes feasibility and screening approaches for developing a Parkinson disease imaging agent. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korat, Š.; Bidesi, N.S.R.; Bonanno, F.; Di Nanni, A.; Hoàng, A.N.N.; Herfert, K.; Maurer, A.; Battisti, U.M.; Bowden, G.D.; Thonon, D.; et al. Alpha-Synuclein PET Tracer Development-An Overview about Current Efforts. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Capotosti, F.; Schain, M.; Ohlsson, T.; Touilloux, T.; Hliva, V.; Vokali, E.; Luthi-Carter, R.; Molette, J.; Dimitrakopoulos, I.K.; et al. Initial clinical scans using [ 18 F]ACI-12589, a novel α-synuclein PET-tracer. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, G.; Murugan, N.A.; Ågren, H. Mechanistic Insight into the Binding Profile of DCVJ and α-Synuclein Fibril Revealed by Multiscale Simulations. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.G.; Margreiter, M.A.; Fuchs, J.E.; Grafenstein, S. von; Tautermann, C.S.; Liedl, K.R.; Fox, T. Heteroaromatic π-stacking energy landscapes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavasi, H.R.; Mir Mohammad Sadegh, B. Influence of N-heteroaromatic π-π stacking on supramolecular assembly and coordination geometry; effect of a single-atom change in the ligand. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 5488–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonschmidt, L.; Matthes, D.; Dervişoğlu, R.; Frieg, B.; Dienemann, C.; Leonov, A.; Nimerovsky, E.; Sant, V.; Ryazanov, S.; Giese, A.; et al. The clinical drug candidate anle138b binds in a cavity of lipidic α-synuclein fibrils. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kumar, A.; Långström, B.; Nordberg, A.; Ågren, H. Insight into the Binding of First- and Second-Generation PET Tracers to 4R and 3R/4R Tau Protofibrils. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paslawski, W.; Lorenzen, N.; Otzen, D.E. Formation and Characterization of α-Synuclein Oligomers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1345, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klunk, W.E.; Wang, Y.; Huang, G.-F.; Debnath, M.L.; Holt, D.P.; Shao, L.; Hamilton, R.L.; Ikonomovic, M.D.; DeKosky, S.T.; Mathis, C.A. The Binding of 2-(4′-Methylaminophenyl)Benzothiazole to Postmortem Brain Homogenates Is Dominated by the Amyloid Component. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 2086–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzuegbunam, B.C.; Librizzi, D.; Hooshyar Yousefi, B. PET Radiopharmaceuticals for Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis, the Current and Future Landscape. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Velasco, A.; Fraser, G.; Beach, T.G.; Sue, L.; Osredkar, T.; Libri, V.; Spillantini, M.G.; Goedert, M.; Lockhart, A. In vitro high affinity alpha-synuclein binding sites for the amyloid imaging agent PIB are not matched by binding to Lewy bodies in postmortem human brain. J. Neurochem. 2008, 105, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).