Submitted:

20 October 2023

Posted:

25 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

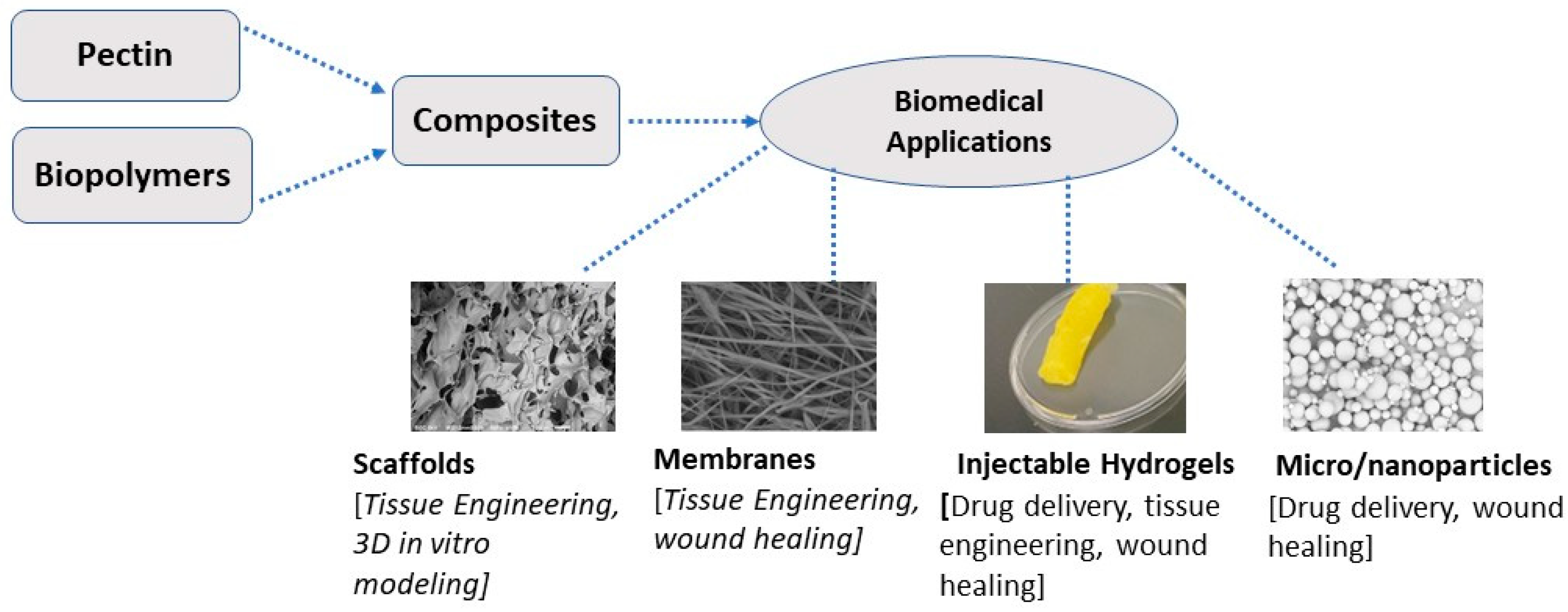

1. Introduction

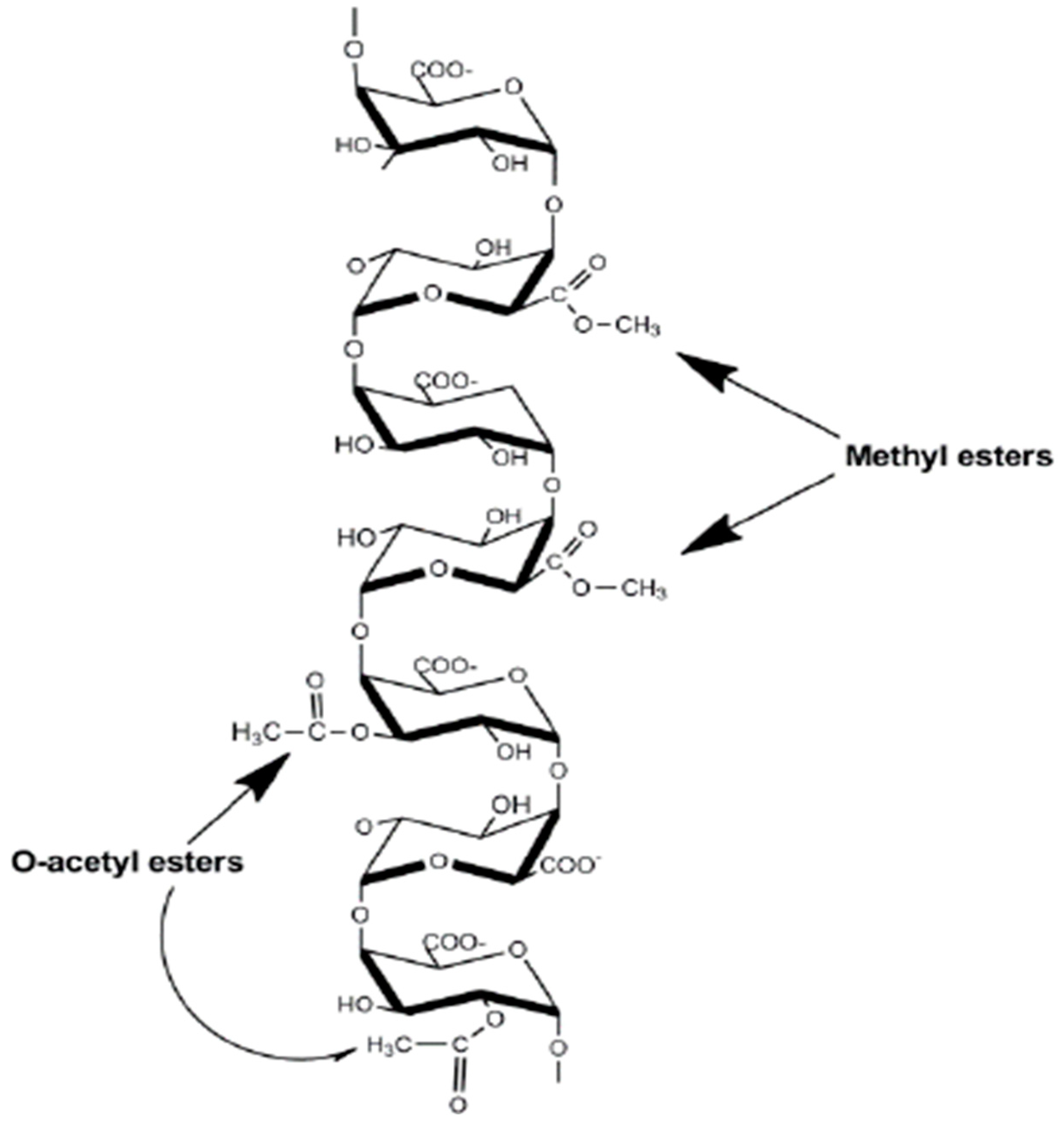

2. Properties of Pectic Polysaccharides

2.1. Immunoregulatory Activity

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.3. Antibacterial Activity

2.4. Anticancer Activity of Pectin and Pectin-Based Composites

3. Pectin for Drug Delivery Applications

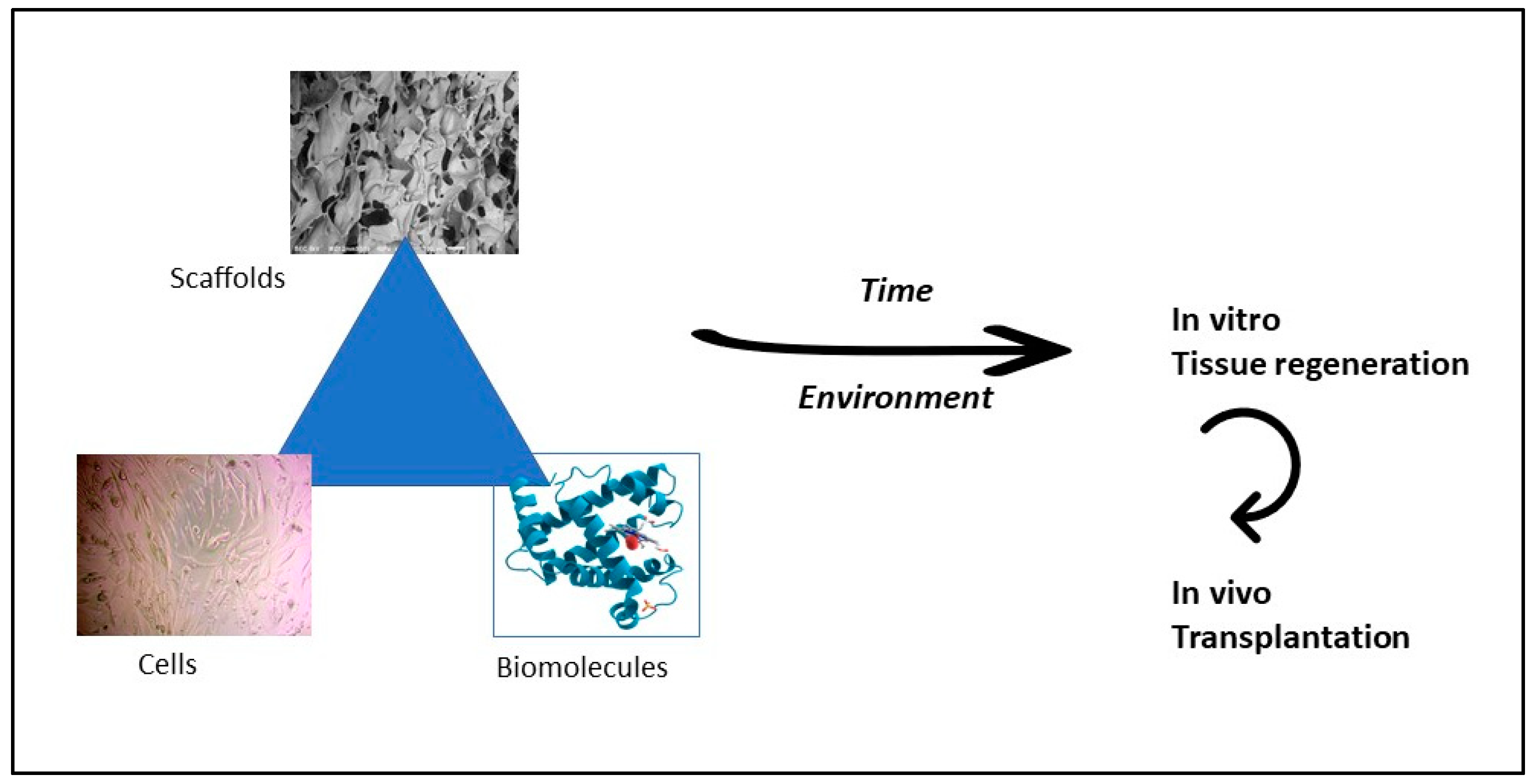

4. Pectin for Tissue Engineering Applications

5. Conclusion and Future Prospects

Acknowledgment

References

- An, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Bo, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, D.; Qin, J. Pectin-based injectable and biodegradable self-healing hydrogels for enhanced synergistic anticancer therapy. Acta Biomater. 2021, 131, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, F., J. Diao, Y. Wang, S. Sun, H. Zhang, Y. Liu, Y. Wang and J. Cao (2017). "A New Water-Soluble Nanomicelle Formed through Self-Assembly of Pectin–Curcumin Conjugates: Preparation, Characterization, and Anticancer Activity Evaluation." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 65(32): 6840-6847. [CrossRef]

- Boehler, R.M.; Graham, J.G.; Shea, L.D. Tissue engineering tools for modulation of the immune response. BioTechniques 2011, 51, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, F.C.B.; de Souza, R.F.B.; Drouin, B.; Mantovani, D.; Moraes. M. Comparative study on complexes formed by chitosan and different polyanions: Potential of chitosan-pectin biomaterials as scaffolds in tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 132, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coimbra, P.; Ferreira, P.; de Sousa, H.; Batista, P.; Rodrigues, M.; Correia, I.; Gil, M. Preparation and chemical and biological characterization of a pectin/chitosan polyelectrolyte complex scaffold for possible bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandel, V., D. Biswas, S. Roy, D. Vaidya, A. Verma and A. Gupta (2022). "Current Advancements in Pectin: Extraction, Properties and Multifunctional Applications." Foods 11(17): 2683. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mei, M.-S.; Xu, Y.; Shi, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Versatile functionalization of pectic conjugate: From design to biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 306, 120605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Gou, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Hu, F.; Cheng, W. Activation of Intrinsic Apoptotic Signaling Pathway in A549 Cell by a Pectin Polysaccharide Isolated from Codonopsis pilosula and Its Selenized Derivative. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2015, 34, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Leng, J.; Liu, D.; Hao, M.; Gao, X.; Tai, G.; Zhou, Y. The inhibitory effects and mechanisms of rhamnogalacturonan I pectin from potato on HT-29 colon cancer cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 64, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, P.; Ferreira, P.; de Sousa, H.; Batista, P.; Rodrigues, M.; Correia, I.; Gil, M. Preparation and chemical and biological characterization of a pectin/chitosan polyelectrolyte complex scaffold for possible bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, V.M.; Walboomers, X.F.; Jansen, J.A. Scanning Electron Microscopy Stereoimaging for Three-Dimensional Visualization and Analysis of Cells in Tissue-Engineered Constructs: Technical Note. Tissue Eng. Part C: Methods 2011, 17, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daguet, D.; Pinheiro, I.; Verhelst, A.; Possemiers, S.; Marzorati, M. Arabinogalactan and fructooligosaccharides improve the gut barrier function in distinct areas of the colon in the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delphi, L.; Sepehri, H. Apple pectin: A natural source for cancer suppression in 4T1 breast cancer cells in vitro and express p53 in mouse bearing 4T1 cancer tumors, in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.E.D.; Winnischofer, S.M.B.; Ramirez, M.I.; Iacomini, M.; Cordeiro, L.M.C. The influence of sweet pepper pectin structural characteristics on cytokine secretion by THP-1 macrophages. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadio, J.L.S.; Prado, S.B.R.D.; Rogero, M.M.; Fabi, J.P. Effects of pectins on colorectal cancer: targeting hallmarks as a support for future clinical trials. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11438–11454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziadek, M.; Dziadek, K.; Salagierski, S.; Drozdowska, M.; Serafim, A.; Stancu, I.-C.; Szatkowski, P.; Kopec, A.; Rajzer, I.; Douglas, T.E.; et al. Newly crosslinked chitosan- and chitosan-pectin-based hydrogels with high antioxidant and potential anticancer activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 290, 119486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Batal, A.I.; Mosalam, F.M.; Ghorab, M.; Hanora, A.; Elbarbary, A.M. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of zinc nanoparticles prepared by natural polysaccharides and gamma radiation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 2298–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswaramma, S.; Reddy, N.S.; Rao, K.S.V.K. Phosphate crosslinked pectin based dual responsive hydrogel networks and nanocomposites: Development, swelling dynamics and drug release characteristics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, D.; Shewale, R.; Patil, V.; Mali, D.; Gaikwad, U.; Jadhav, N. Enhancement in in vitro anti-angiogenesis activity and cytotoxicity in lung cancer cell by pectin-PVP based curcumin particulates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Rosas, M.; Morales-Castro, J.; Cubero-Márquez, M.; Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Martín-Belloso, O. Antimicrobial activity of nanoemulsions containing essential oils and high methoxyl pectin during long-term storage. Food Control. 2017, 77, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Pathania, D.; Asif, M.; Sharma, G. Liquid phase synthesis of pectin–cadmium sulfide nanocomposite and its photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2014, 196, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Chávez, M.L.; Claudio-Rizo, J.A.; Caldera-Villalobos, M.; Cabrera-Munguía, D.A.; Becerra-Rodríguez, J.J.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, N. Novel bioactive collagen-polyurethane-pectin scaffolds for potential application in bone regenerative medicine. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.A.; Elseoud, W.S.A.; Abo-Elfadl, M.T.; Hassan, M.L. New pectin derivatives with antimicrobial and emulsification properties via complexation with metal-terpyridines. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 268, 118230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.T.T.; Zou, Y.-F.; Aslaksen, T.H.; Wangensteen, H.; Barsett, H. Structural characterization of bioactive pectic polysaccharides from elderflowers ( Sambuci flos ). Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 135, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Xu, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, J.; Low, Z.W.K.; Chee, P.L.; Lu, Z.; Zheng, L.; Kai, D. PVA/pectin composite hydrogels inducing osteogenesis for bone regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 16, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Dharmesh, S.M. Pectic Oligosaccharide from tomato exhibiting anticancer potential on a gastric cancer cell line: Structure-function relationship. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 160, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotimchenko, Y.; Khozhaenko, E.; Kovalev, V.; Khotimchenko, M. Cerium Binding Activity of Pectins Isolated from the Seagrasses Zostera marina and Phyllospadix iwatensis. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.S.; Ramya, C.; Jayakumar, R.; Nair, S.K.V.; Lakshmanan, V.-K. Drug delivery and tissue engineering applications of biocompatible pectin–chitin/nano CaCO3 composite scaffolds. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2013, 106, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapomarda, A.; De Acutis, A.; Chiesa, I.; Fortunato, G.M.; Montemurro, F.; De Maria, C.; Belmonte, M.M.; Gottardi, R.; Vozzi, G. Pectin-GPTMS-Based Biomaterial: toward a Sustainable Bioprinting of 3D scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Application. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclere, L.; Fransolet, M.; Cote, F.; Cambier, P.; Arnould, T.; Van Cutsem, P.; Michiels, C. Heat-Modified Citrus Pectin Induces Apoptosis-Like Cell Death and Autophagy in HepG2 and A549 Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0115831–e0115831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivas, C.L.; Nascimento, L.F.; Barros, W.M.; Santos, A.R.; Iacomini, M.; Cordeiro, L.M. Substituted galacturonan from starfruit: Chemical structure and antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 84, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Dang, J.; Wang, Q.; Yu, M.; Jiang, L.; Mei, L.; Shao, Y.; Tao, Y. Optimization of polysaccharides from Lycium ruthenicum fruit using RSM and its anti-oxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 61, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F.; Peng, L.; Lei, Z.; Jia, X.; Zou, J.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Zeng, N. Traditional Uses, Phytochemical Constituents and Pharmacological Properties of Averrhoa carambola L.: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, E.G.; Colquhoun, I.J.; Chau, H.K.; Hotchkiss, A.T.; Waldron, K.W.; Morris, V.J.; Belshaw, N.J. Modified sugar beet pectin induces apoptosis of colon cancer cells via an interaction with the neutral sugar side-chains. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minzanova, S.T.; Mironov, V.F.; Arkhipova, D.M.; Khabibullina, A.V.; Mironova, L.G.; Zakirova, Y.M.; Milyukov, V.A. Biological Activity and Pharmacological Application of Pectic Polysaccharides: A Review. Polymers 2018, 10, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarok, W.; Elvitigala, K.C.M.L.; Kotani, T.; Sakai, S. Visible light photocrosslinking of sugar beet pectin for 3D bioprinting applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 316, 121026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munarin, F.; Guerreiro, S.G.; Grellier, M.A.; Tanzi, M.C.; Barbosa, M.A.; Petrini, P.; Granja, P.L. Pectin-Based Injectable Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munarin, F.; Tanzi, M.C.; Petrini, P. Advances in biomedical applications of pectin gels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzoughi, Z., A. Abdelhamid, C. Rihouey, D. Le Cerf, A. Bouraoui and H. Majdoub (2018). "Optimized extraction of pectin-like polysaccharide from Suaeda fruticosa leaves Characterization, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities." Carbohydr Polym 185: 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, L.; Bianco-Peled, H. Pectin–chitosan physical hydrogels as potential drug delivery vehicles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, T.; Yang, X.; Alim, A.; Iqbal, M.; Wang, Z.-C.; Guo, Y. Physicochemical responses and microbiological changes of bream (Megalobrama ambycephala) to pectin based coatings enriched with clove essential oil during refrigeration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 124, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, F.J. Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Villarreal, M.; Aispuro-Hernández, E.; Vargas-Arispuro, I.; Ngel, M. Plant Cell Wall Polymers: Function, Structure and Biological Activity of Their Derivatives. In Polymerization; InTech: 2012; pp. 63–86.

- Ogbonna, C. and D. Kavaz (2022). "Development of novel silver-apple pectin nanocomposite beads for antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer studies." Biologia 77(3): 879-891.

- Ogutu, F.O.; Mu, T.-H.; Sun, H.; Zhang, M. Ultrasonic Modified Sweet Potato Pectin Induces Apoptosis like Cell Death in Colon Cancer (HT-29) Cell Line. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, M.A.; Ishii, T.; Albersheim, P.; Darvill, A.G. RHAMNOGALACTURONAN II: Structure and Function of a Borate Cross-Linked Cell Wall Pectic Polysaccharide. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, S.; Ksouri, R.; Falleh, H.; Pichette, A.; Abdelly, C.; Legault, J. Phenolic content, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of the edible halophyte Suaeda fruticosa Forssk. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, D., G. Sharma and R. Thakur (2015). "Pectin @ zirconium (IV) silicophosphate nanocomposite ion exchanger: Photo catalysis, heavy metal separation and antibacterial activity." Chemical Engineering Journal 267: 235-244. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, L. F., A. Raz and J. P. Fabi (2022). "The Complex Biological Effects of Pectin: Galectin-3 Targeting as Potential Human Health Improvement?" Biomolecules 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Xu, Q.; Yin, H.; Huang, L.; Du, Y. Characterization of an immunologically active pectin from the fruits of Lycium ruthenicum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 64, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.F.; Barrias, C.C.; Bártolo, P.J.; Granja, P.L. Cell-instructive pectin hydrogels crosslinked via thiol-norbornene photo-click chemistry for skin tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2018, 66, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Mazeau, K.; du Penhoat, C.H. The three-dimensional structures of the pectic polysaccharides. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2000, 38, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, S.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, M.; Doco, T. A complex plant cell wall polysaccharide: rhamnogalacturonan II. A structure in quest of a function. Biochimie 2003, 85, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, S.V.; Markov, P.A.; Popova, G.Y.; Nikitina, I.R.; Efimova, L.; Ovodov, Y.S. Anti-inflammatory activity of low and high methoxylated citrus pectins. Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2013, 3, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, S.V.; Ovodov, Y.S. Polypotency of the immunomodulatory effect of pectins. Biochem. (Moscow) 2013, 78, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, S.B.R.D.; Ferreira, G.F.; Harazono, Y.; Shiga, T.M.; Raz, A.; Carpita, N.C.; Fabi, J.P. Ripening-induced chemical modifications of papaya pectin inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambhia, K.J.; Ma, P.X. Controlled drug release for tissue engineering. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, H.; Bergman, M.; Djaldetti, M.; Orlin, J.; Bessler, H. Citrus pectin affects cytokine production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008, 62, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, C. L., S. S. Kim, R. N. Dilger, L. L. Bauer, M. L. Moon, R. I. Tapping, G. C. Fahey, K. A. Tappenden and G. G. Freund (2010). "Sickness behavior induced by endotoxin can be mitigated by the dietary soluble fiber, pectin, through up-regulation of IL-4 and Th2 polarization." Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 24(4): 631-640. [CrossRef]

- Sriamornsak, P.; Sungthongjeen, S.; Puttipipatkhachorn, S. Use of pectin as a carrier for intragastric floating drug delivery: Carbonate salt contained beads. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 67, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, K.U.; Govindaraju, K.; Kumar, V.G.; Karthick, V.; Parthasarathy, K. Pectin mediated gold nanoparticles induces apoptosis in mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, S.; Mieszkowska, A.; Folkert, J.; Rana, N.; Mohamed-Ahmed, S.; Fuoco, T.; Finne-Wistrand, A.; Dirscherl, K.; Jørgensen, B.; Mustafa, K.; et al. Immune-instructive copolymer scaffolds using plant-derived nanoparticles to promote bone regeneration. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supreetha, R., S. Bindya, P. Deepika, H. M. Vinusha and B. P. Hema (2021). "Characterization and biological activities of synthesized citrus pectin-MgO nanocomposite." Results in Chemistry 3. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, L.M.; Sahasrabudhe, N.M.; Ramasamy, U.; Meyer, D.; Pullens, G.; Faas, M.M.; Venema, K.; Schols, H.A.; de Vos, P. The impact of lemon pectin characteristics on TLR activation and T84 intestinal epithelial cell barrier function. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 22, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. , Wang, H., Zhu X. H., Hou Y. C., Liu W. W., Yang, G. M., Jiang, A. (2015) Pectin-chitosan complex: Preparation and application in colon-specific capsule. Int J Agric & Biol Eng, 8(4), 151-160. [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, O.; Khudyakov, A.; Sergushkina, M.; Solomina, O.; Polezhaeva, T. Pectins as a universal medicine. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, P.; Zhan, Y.; Shi, X.; Lin, J.; Du, Y.; Li, X.; Deng, H. Pectin/lysozyme bilayers layer-by-layer deposited cellulose nanofibrous mats for antibacterial application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Citrus pectin derived silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2017, 47, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Liang, L.; Fan, X.; Yu, Z.; Hotchkiss, A.; Wilk, B.J.; Eliaz, I. The role of modified citrus pectin as an effective chelator of lead in children hospitalized with toxic lead levels. . 2008, 14, 34–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Pectin source | Uses and mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| i. Lemon Pectin | The physical-chemical characteristics of lemon pectin, for example, the degree of methyl esterification and the extent of polymerization, influence the immunostimulatory properties and are significantly essential to utilize pectins to improve immune response. | (Daguet et al. 2016, Vogt et al. 2016) |

| ii. Sumbuci floss or elderflower | Used to heal various diseases linked with the immune system, for example, influenza, chill, or pyrexia. Extracts from S. nigra flowers have stimulation effects on macrophages. In vitro studies reported that the biological activity of rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-1) comprising polysaccharides of elderflowers contributes to higher immunomodulation activity and enhanced macrophage-stimulating effects. | (Ho et al. 2016, Minzanova et al. 2018) |

| iii. Tomato Pectin | Pectic oligosaccharides in sour raw tomatoes demonstrated potential as an anticancer on a gastric cancer cell line in vitro. | (Kapoor and Dharmesh 2017) |

| iv. Lycium ruthenium | Polysaccharides in L. ruthenium suppressed the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages and exhibited antifatigue, antioxidation, and hypoglycemic activity. | (Liu et al. 2013, Peng et al. 2014) |

| Pectin source | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| i. Star fruit (Averrhoa carambola L.) | In vivo, the study reported that the polysaccharides from starfruit exhibited antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties and were beneficial for controlling inflammatory pain. | (Leivas et al. 2016, Luan et al. 2021) |

| ii. Suaeda fruiticosa (L.) Forssk | Polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and bioactive flavonoids from S. fruticose, comprising free radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation, function as an anti-inflammatory agent and analgesic or antioxidant. | (Oueslati et al. 2012, Mzoughi et al. 2018) |

| iii. Citrus pectin | An in vivo study demonstrated that low methyl-esterified pectin from citrus fruits inhibited systemic and local inflammation, whereas a high degree of esterification inhibited intestinal inflammation. | (Sherry et al. 2010, Popov et al. 2013) |

| iv. Sweet Pepper fruits | Both native and modified pectin possessed the inherent activity to control THP-1 macrophages. Due to the availability of lipopolysaccharides, anti-inflammatory properties occur by inhibiting pro-inflammatory and promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines. | (do Nascimento et al. 2017, Pedrosa et al. 2022) |

| Pectin-based system | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| i. Citrus Pectin-coated Ag nanoparticles (NPs) | Citrus pectin-coated Ag NPs exhibited great antibacterial activities toward Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive S. Aureus. | (Zhang et al. 2017) |

| ii. Pectin-cadmium sulfide nanocomposite (Pc/CSNC); Pectin-zirconium (IV) silicophosphate nanocomposite (Pc/ZSPNC) | Pc/CSNC exhibited a significant effect of antibacterial activity against E. coli. PC/ZSPNC showed substantial antibacterial activity towards E. coli and S. aureus. | (Gupta et al. 2014, Pathania et al. 2015, Hassan et al. 2021) |

| iii. Citrus pectin-MgO Nanocomposites | Pectin-MgO showed significant antibacterial activity against clinical pathogens lactobacillus and Bacillus subtills. | (Supreetha et al. 2021) |

| iv. Pectin/lysozymes layer by layer nanofibrous mats | Pectin/lysosome nanofibrous mats exhibited significant antibacterial effects against E. coli and S. aureus. | (Zhang et al. 2015) |

| v. Essential oils (EOs)/Pectin nanoemulsion | EOs/Pectin nanoemulsion exhibited antibacterial activity towards E. coli and L. innocua populations. | (Guerra-Rosas et al. 2017, Nisar et al. 2019) |

| Pectin source or pectin-based system | Target cancer cell line | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pectin from potato | Human colon cancer HT-29 cells | Rhamnogalacturonan (RG)-I domain-rich potato pectin showed the inhibitory effect of HT-29 cell proliferation in vitro. | (Cheng et al. 2013, Donadio et al. 2022) |

| Pectin from sugar beet | Human colon cancer cell lines (HT-29 and DLD-1) | An in vitro study reported that the pectin from sugar beet exhibited anti-proliferative activity toward colon cancer cells—alkali-treated sugar beet pectin extract induced apoptosis. | (Maxwell et al. 2016) |

| Pectin from sweet potato | Human colon cancer HT-29 cells | Sweet potato pectin modified by ultrasonication inhibited HT-29 cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in vitro. | (Ogutu et al. 2018) |

| Pectin from apple | Breast cancer cells 4T1 | Pectic acid from apple pectin inhibited 4T1 breast cancer cell growth, reduced cell attachment, and induced apoptosis in vitro. In vivo, results exhibited that pectic acid inhibited tumor progression and increased apoptosis cell number. | (Delphi and Sepehri 2016) |

| Citrus pectin | Liver hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG2 and Adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells A549 | Citrus pectin (heat-modified) induced classical apoptosis and indicated the activation of autophagy in both HepG2 and A549 cancer cell lines. | (Leclere et al. 2015) |

| Pectin from papaya | Colon cancer cell, prostate cancer cell | Papaya pectin extracted from intermediate ripening phases significantly decreased cell viability and induced necroptosis in cancer cell lines in vitro. | (Prado et al. 2017) |

| Pectin-Curcumin | Breast and hepatic cervical cancer cells | The pectin-curcumin complex had better inhibitory activity against cancer cells than only curcumin due to the increased stability and solubility of the composites. | (Bai et al. 2017, Chen et al. 2023) |

| Pectic polysaccharide/Selenium | Adenocarcinomas human alveolar basal epithelial cells | Pectic polysaccharide/Selenium showed a higher inhibiting capacity for cell migration and initiated cell apoptosis than the original pectin polysaccharides. | (Chen et al. 2015) |

| Pectin-polyvinyl pyrrolidone-curcumin | Lung cancer cells A549 | Pectin-polyvinyl pyrrolidone-curcumin particulates showed increased anti-tumor effects than curcumin alone. | (Gaikwad et al. 2017) |

| Pectin/silver (Ag) nanocomposites | Epithelial human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 | Pectin/Ag nanocomposites showed a significantly high inhibitory effect on breast cancer cell proliferation. | (Ogbonna and Kavaz 2022) |

| Pectin/gold nanoparticles | Mammary adenocarcinoma | Pectin/gold nanoparticles induced apoptosis and decreased the viability of the cancer cells. | (Suganya et al. 2016) |

| Citrus pectin/Znnanoparticles | Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma and human colon adenocarcinoma | The citrus pectin/Zn nanoparticles showed anticancer properties by influencing cancer cell cytotoxicity. | (El-Batal et al. 2018) |

| Pectin/Chitosan | Human colon cancer HT-29 cells | Pectin/chitosan composites exhibited anti-proliferative effects on cancer cells but no cytotoxic effects on normal cells. | (Dziadek et al. 2022) |

| Pectin aldehyde/poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide-stat-acyl hydrazide) P(NIPAM-stat-AH) | Colon carcinoma cells CT26 | In vivo, the study revealed that the self-healing and injectable composites had the potential for anticancer therapy. | (An et al. 2021) |

| Pectin systems | Method | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low methoxyl citrus pectin | UV photocrosslinking with peptide crosslinkers (cell-degradable) and adhesive ligands (integrin-specific); Lyophilization | Skin tissue engineering | (Pereira et al. 2018) |

| Sugar beet pectin (SBP) crosslinked by visible light | Applying 405 nm visible light in the presence of tris(bipyridine)ruthenium (II) chloride hexahydrate and sodium persulfate, rapid hydrogenation of SBP was obtained. 3D hydrogel constructs were obtained using 3D bioprinting. | Promising for liver and other soft tissue engineering | (Mubarok et al. 2023) |

| Citrus peel's pectin crosslinked with (3glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPTMS) | Freeze drying or 3D bioprinting | Various tissue regeneration | (Lapomarda et al. 2020) |

| Pectin/ chitin/nano CaCO3 | Lyophilization | Bone regeneration | (Kumar et al. 2013) |

| Pectin/chitosan | Freeze drying | Bone tissue engineering | (Coimbra et al. 2011) |

| Pectin/Strontium/Hydroxyapatite | Solution-based chemical technique | Bone regeneration | (Akshata et al. 2023) |

| Collagen/polyurethane/pectin | Semi-interpenetration process | Bone regeneration | (Guzmán-Chávez et al. 2022) |

| Pectin/PVA | Freezing-thawing | Bone regeneration | (Hu et al. 2022) |

| Poly(L-lactide-co-ɛ-caprolactone) (PLCA) /pectin | Scaffolds functionalized with pectin. | In vitro and in vivo bone regeneration | (Suliman et al. 2022) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).