1. Introduction

As a new type of biological wastewater treatment approach, algal-bacterial granular sludge technology has attracted extensive attention [

1]. It has been reported that algal-bacterial granular sludge process can effectively remove nutrients and pollutants in wastewater under simulated light and dark cycling [

2]. In contrast to traditional wastewater treatment technologies, algal-bacterial granular sludge relies on the symbiotic relationship between algae and bacteria, i.e., aerobic bacteria use the oxygen released by algal photosynthesis to convert organic carbon into carbon dioxide, while algae use inorganic nitrogen and phosphate for photosynthesis to synthesize intracellular components for their own growth and reproduction. In this process, released oxygen is used as an electronic receptor for bacteria to degrade organic matters and phosphorus [

3]. The synergistic cycle between algae and bacteria can effectively improve the removal efficiency of nutrients and reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [

4,

5].

At present, in the research focused on the application of algal-bacterial granular sludge for wastewater treatment, most of the influent water used in the laboratory scale experiment is simulated wastewater with simple and controlled compositions, i.e., the carbon source is provided by sodium acetate, glucose or sucrose, the nitrogen source is provided by ammonium chloride, and the phosphorus source is provided by phosphate. Under these conditions, the algal-bacterial granular sludge can operate stably for a long time and meet the effluent quality requirements [

6]. In reality, the composition of actual wastewater is complex, and the understanding of the impact of some toxins in wastewater on engineering feasibility of algal-bacterial granular sludge implementation is limited. As reported in our previous studies, the abundance of algae in algal-bacterial granular sludge was reduced, and the symbiotic relationship between algae and bacteria was destroyed under the stress of 1−10 mg/L of Cd(Ⅱ) [

7]. To cope with this, increased polysaccharide (PS) from 37 ± 4 mg/g VSS to 110 ± 5 mg/g VSS was secreted [

7]. Research into algal-bacterial granular sludge effectiveness in the presence of other toxic heavy metals has also been conducted (Cr(VI) and Pb (Ⅱ)) has been conducted [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], but these studies mainly focused on the adsorption and bioremediation of heavy metals.

Increased industrial activities have resulted in increased discharge of heavy metal-containing wastewater. As one of the most widely used metals in the industry, chromium, mainly as Cr(VI), deserves attention. Cr(VI) can cause various acute and chronic diseases and affects the metabolism and normal function of living cells [

13]. Due to the adverse effects of Cr(VI) on microorganisms, Cr(VI) may cause irreversible damage to wastewater biological treatment systems and can adversely influence the effluent quality. The World Health Organization (WHO) and United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) have recommended limits of 0.05 mg/L and 0.10 mg/L for Cr(VI) concentrations in drinking and surface waters [

14]. However, the concentration of Cr(VI) in wastewater are generally significantly greater than the specified threshold.

To enhance the feasibility of engineering implementation of algal-bacterial granular sludge, some questions need to be answered: (i) What is the performance of algal-bacterial granular sludge in treating wastewater containing Cr(VI)? (ii) Will the effluent water meets the standard of <0.05 mg Cr(VI)/L? (iii) How stable is the algal-bacterial granular sludge with prolonged operation? Compared to the conventional bacterial aerobic granular sludge, algal-bacterial granular sludge had been used as an adsorbent for Cr(VI) from wastewater showing advantages in both biosorption capacity and granular stability [

11]. However, there is little information concerning the performance of algal-bacterial granular sludge under Cr(VI) stress and the resulting adaptive responses. Consequently, the main purpose of this study was to explore the impact of Cr(VI) at environmentally relevant concentrations on nutrient (carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus) removal and adaptive responses, including microbial community and physiological changes of the algal-bacterial granular sludge. It is expected that this study can provide useful information for advanced research and practical application of algal-bacterial granular sludge technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater and algal-bacterial granular sludge

The stimulated wastewater was composed of NaAc (446 mg/L), NH

4Cl (115 mg/L), KH

2PO

4 (22 mg/L), FeCl

3 (10 mg/L), CaCl

2 10 (mg/L), MgSO

4·7H

2O (10 mg/L) and trace elements (1 mg/L). The stock solution of trace elements has the following components: 10 g/L of EDTA, 100 mg/L of MnSO

4·H

2O, 30 mg/L of CuSO

4·5H

2O, 120 mg/L of ZnSO

4·7H

2O, 150 mg/L of H

3BO

3, 60 mg/L of Na

2MnO

4·2H

2O, 180 mg/L of KI, and 150 mg/L of CoCl

2·6H

2O. Algal-bacterial granular sludge used in the present study was cultivated using the methods described in our previous publications [

7,

15,

16].

2.2. Batch experiments

In the batch experiments conducted, in a series of micro-reactors with diameter of 47 mm and height of 60 mm, 5 mL of fresh algal-bacterial granular sludge was added into 50 mL of stimulated wastewater, corresponding to a volatile suspended solids (VSS) concentration of 23.9 ± 0.2 g/L. The reactors were exposed to full-wavelength LED illumination of 10000 lux. The LED light was 10 cm above the reactors. The initial Cr(VI) concentrations were 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 mg/L. Cr(VI)-free culture was set as the control group. The six series of batch experiments were done in triplicates and conducted under alternate light and dark cycle of 8 h/16 h at room temperature. The initial pH was 7.0 ± 0.2. Samples were taken after 8 h of light and were filtered through a microporous membrane (0.45 μm) for further analysis. No external aeration, stirring or shaking was provided.

2.3. Analysis methods

Chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonia-N and phosphate-P were determined according to standard methods [

17]. A PHS-3E pH meter (INESA Scientific Instrument Co, China) was used to measure solution pH. The concentrations of Cr(VI) and total Cr were quantified using the diphenylcarbazide spectrophotometric method with a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (TU-1810, China) at 540 nm and a Pinaacle900F atomic absorption spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, American), respectively. Chlorophyll a and b were extracted with a mixture of acetone and ethanol (7,2) to quantify their contents in the algal-bacterial granular sludge [

18].

EPS-polysaccharides (EPS-PS) content was measured by the phenol-sulfuric acid method [

19]. EPS-proteins (EPS-PN) content was measured using C504031 Lowry Protein Assay Kits (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai) according to the instructions. EPS compositions were further analyzed using a DM4000B Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Leica, German) with 250−400 nm excitation wavelength and 280−550 nm emission wavelengths to obtain three-dimensional excitation-emission (3D-EEM) spectrograms.

The algal-bacterial granular sludge samples were collected after 90-day culture for microbial community analysis. DNA in samples was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of total DNA was checked by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and further quantified. The 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA genes were amplified using 515F/907R prokaryotic primers targeting the V4-V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene and 528F/706R eukaryotic primers targeting the V4 region of the 18S rRNA gene, respectively [

20]. The purified amplicons were collected in an equimolar manner on the Illumina MiSeq platform and sequenced by Meiji Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Fresh algal-bacterial granular sludge was pretreated according to the method described in a previous study [ang,Ji[

7] to obtain dry powders. Morphology and surface compositions were analyzed using a JSM 7200F scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL, Japan) equipped with energy disperse spectroscopy (EDS). The surface element compositions were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS. Axis-Ultra DLD) (Kratos, Britain) employing a mono-chromated K

α X-ray source.

Algal-bacterial granular sludge was frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to paste, followed with being mixed with phosphate buffer and centrifuged for 10 min to obtain the supernatant as a crude enzyme solution. The contents of malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) were respectively determined using A003-1, A001-1, and A007-1 kits (NanJing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing) according to the instructions.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Performance of algal-bacterial granular sludge process on nutrient removal under Cr(VI) stress

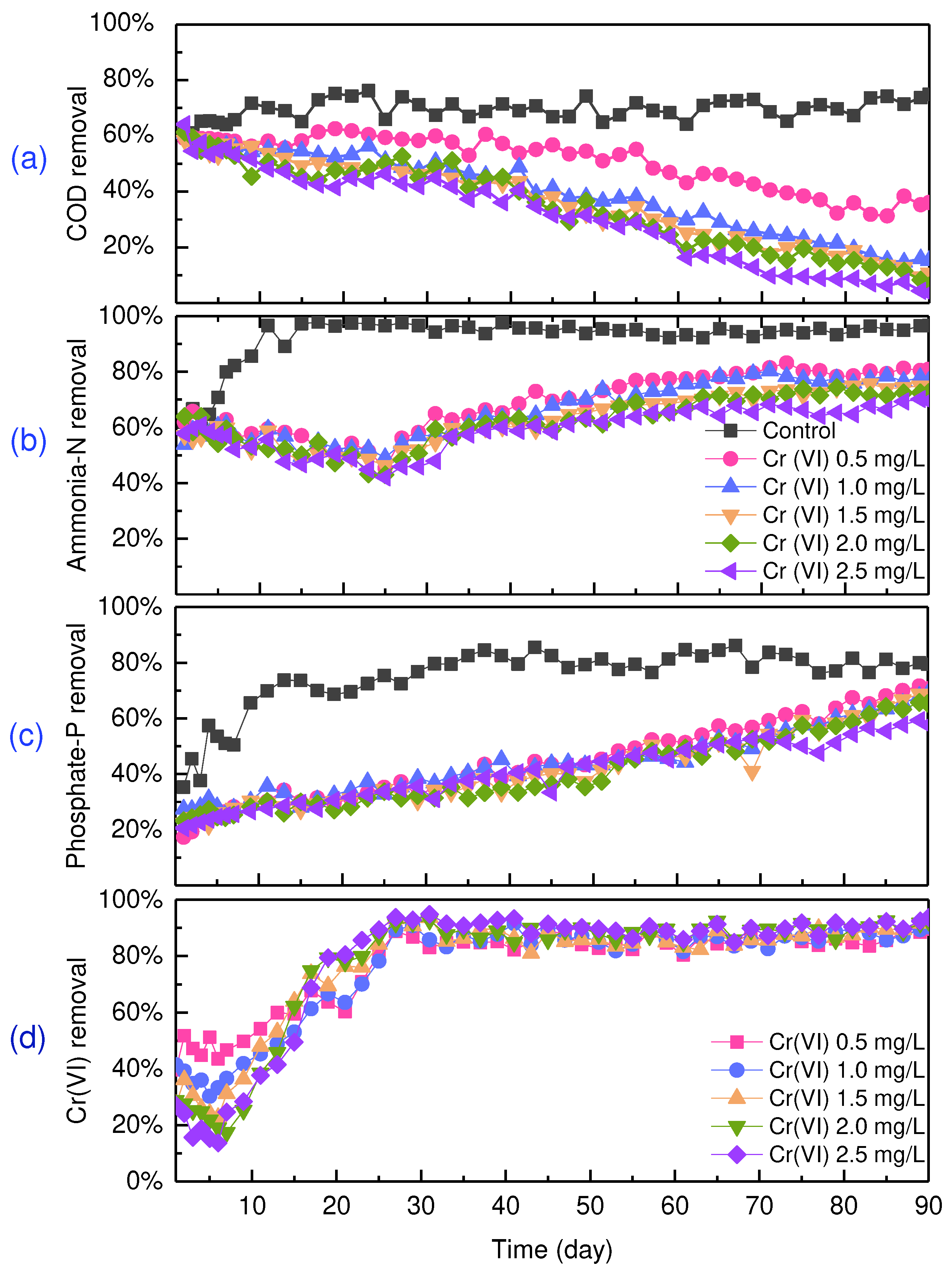

Compared to the control group, COD removal decreased with increased initial Cr(VI) concentration (

Figure 1a). After ninety days of operation, COD removal was 75%, 36%, 15%, 11%, 6% and 4% (

p < 0.05) at Cr(VI) concentrations of 02.5 mg/L, indicating that COD removal was inhibited by Cr(VI) and concentration-dependent. Compared to Cd(Ⅱ), the tolerance threshold level of algal-bacterial granular sludge to Cr(VI) was less, evidenced by the result that 1 mg/L Cd(Ⅱ) had insignificant effect on the observed COD removal [

7], while 0.5−1.0 mg/L Cr(VI) greatly inhibited COD removal. Ammonia-N removal showed different trends in the control as compared to Cr(VI)-added experiments (

Figure 1b). In the first fifteen days in the control, ammonia-N removal increased from 62% to 97%. This may be due to adaptation to experimental conditions. Thereafter ammonia-N removal was stable at about 95%. For the experimental groups, ammonia-N removal decreased in the first twenty-five days and thereafter increased. It should be noted that ammonia-N removal decreased with increasing Cr(VI) concentrations (i.e., 0.5-2.5 mg/L), indicating slightly inhibitory effect of Cr(VI) on ammonia-N removal. As for phosphate-P removal shown in

Figure 1c, a similar trend was observed in the control, that is, in the first ten days, phosphate-P removal increased from 35% to 74%, and thereafter was stable at about 80%. In the Cr(VI)-added experiments, phosphate-P removal tended to linearly increase with cultivation time with insignificant difference between different Cr(VI) concentrations.

Figure 1d showed the variations of Cr(VI) removal by algal-bacterial granular sludge across ninety days of operation. In the first seven days, Cr(VI) removal showed fluctuations, but with a general downward trend. Cr(VI) removal at 2.5-0.5 mg/L at the end of seven days was 25-47%, indicating greater concentrations of Cr(VI) inhibited, relatively, Cr(VI) removal. Subsequently, Cr(VI) removal tended to increase linearly and became stable at 80-90%. The quality of effluent water after ninety days of cultivation was shown in

Table 1. As seen, COD, ammonia-N and phosphate-P from the control were 68, 1.04 and 0.98 mg/L, respectively, meeting water quality standards for China and Europe (see

Table 1). The greater concentrations of Cr(VI) did greatly affected the performance of the algal-bacterial granular sludge. At Cr(VI) concentration of 0.5 mg/L, COD and ammonia-N concentrations in the effluent water were 222 and 5.74 mg/L, which were less than the maximum permitted concentrations. However, 1.47 mg/L of phosphate-P was above the permitted concentration. Importantly, Cr(VI) and total Cr concentrations in all groups were greater than or equal to the specified threshold. Based on these results, 00.5 mg/L of Cr (VI)-containing wastewater could be handled by algal-bacterial granular sludge process as the permitted maximum concentration of Cr(VI) was 0.05 mg/L. However, the proposed process was unable to effectively treat greater than 0.5 mg/L of Cr(VI) to meet the discharge requirements but could be considered as an alternative approach for treating low concentration of Cr(VI)-containing wastewater.

3.2. Fate of Cr(VI) in algal-bacterial granular sludge

The algal-bacterial granular sludge cultured for 90 days was examined using EDS to explore the distribution of Cr (

Figure S1). It was found that the accumulated Cr content increased from 0.35% to 2.98% for the initial Cr(VI) concentrations of 0.5-2.5 mg/L. SEM images and elemental mapping further revealed the distribution of Cr(VI) in algal-bacterial granular sludge (

Figure S2). An XPS survey scan of the algal-bacterial granular sludge cultivated for 90 days with 2.5 mg/L of Cr (VI) showed the algal-bacterial granular sludge to be composed of C, N, O, and Cr (

Figure S3a). In the high resolution XPS spectrum of Cr 2

p (

Figure S3b), two strong peaks centered at 586.9 eV and 576.6 eV can be attributed to the binding energy of Cr 2

p1/2 and Cr 2

p3/2, respectively suggesting that the aqueous Cr(VI) had been converted into Cr(III). As reported previously, algal-bacterial granular sludge could be used as a new type of biosorption material to remove Cr(VI) through biosorption, biochemical reduction and intracellular accumulation [

8,

10,

11,

12].

Algal-bacterial granular sludge has significant potential in the treatment of Cr containing wastewater due to its abundant surface adsorption sites and high tolerance to toxic substances [

23]. [ang,Zhao[

11] reported that the maximum biosorption capacity could reach as much as 51.0 mg Cr(VI)/ g MLSS at pH 2. Secreted extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), polysaccharides, proteins and lipids in algal cell wall, and peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls can all provide many functional groups contributing to the biosorption of Cr(VI) [

24]. Algal biomass can supply different functional groups (e.g., carbonyl, carboxyl and hydroxyls) capable of binding Cr(VI) [

25]. Cr(VI) adsorption on the surface of algal-bacterial granular sludge occurs through different paths, e.g., covalent bond formation between functional groups of EPS and cell walls and ionic exchange of Cr(VI) with light metal ions (e.g., Ca (Ⅱ) and Mg (Ⅱ)) [

11].

Rapid biosorption, considered to be the first stage for Cr(VI) removal, occurs extracellularly and is a passive process. The second stage is bioaccumulation, which is a positive and intracellular process [

26]. Considering trace concentrations of free Cr(VI) detected during 30−90 days of cultivation in this study (

Figure 1d), it can be assumed that Cr(VI) adsorbed on the surface of algal-bacterial granular sludge is transformed to Cr(III). The addition of reducible carbon compounds (e.g., acetate) in the stimulated wastewater was responsible for this transformation. Cr(VI) is adsorbed on the surface of algal-bacterial granular sludge, can be actively transported across the cell membranes, and be reduced by reductase to form organic-Cr(III) complex [

10]. Compared to Cr(VI), Cr(III) is less soluble and hardly permeates cell membranes [

27]. Therefore, Cr(III) aggregates on the outside of the cell membranes and changes the cell surface morphology [

27].

3.3. Changes in microbial communities under Cr(VI) stress

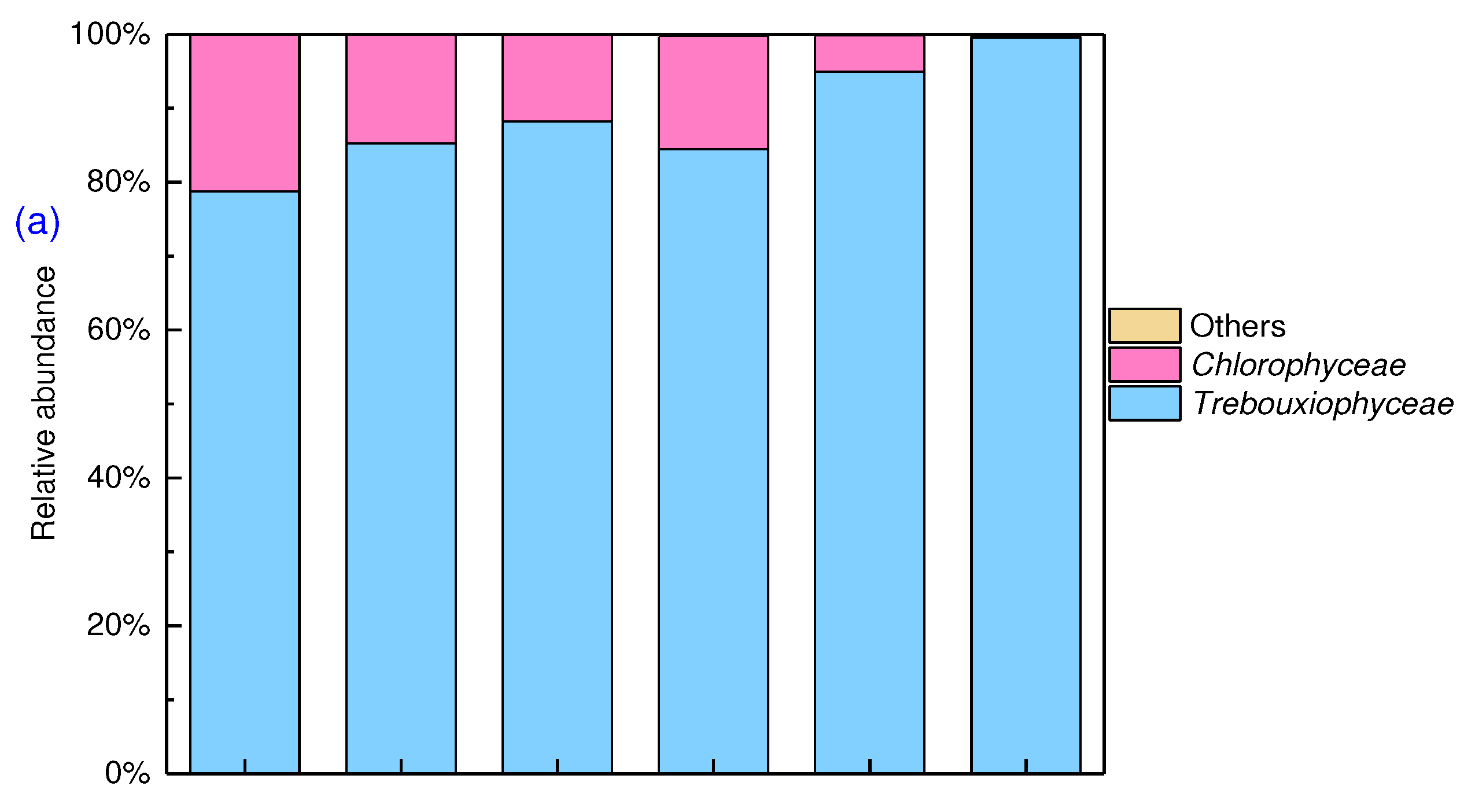

Figure 2 showed the relative abundance of eukaryotic diversity at species level and prokaryotic diversity at phylum level in algal-bacterial granular sludge after 90 days of cultivation.

Trebouxiophyceae and

Chlorophyceae were the main eukaryotic algae. In the control their relative abundances were 78.7% and 21.2%, respectively. With increased Cr(VI) from 0.5 mg/L to 2.5 mg/L, the relative abundance of

Trebouxiophyceae increased from 85.2% to 99.6%, while

Chlorophyceae decreased from 21.2% to 0.2%, indicating that Cr(VI) affected the composition of eukaryotic algae.

As Trebouxiophyceae is a Cr-tolerant strain [

28],

Chlorophyceae accounted for a small proportion (0.2%) while

Trebouxiophyceae was the predominant eukaryotic microalgae at Cr(VI) concentration of 2.5 mg/L.

The dominant bacteria in the prokaryotic microbial community were

Proteobacteria, cyanobacteria and

Bacteroidota, accounting for 46.5%, 31.0% and 9.2%, respectively, in the control. The relative abundance of

Proteobacteria increased with Cr(VI) concentration from 0.5 mg/L to 2.5 mg/L. Several bacteria have been identified as being able to reduce very toxic Cr(VI) to less toxic Cr(III) under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, which is considered an alternative approach to removal of Cr(VI).

Proteobacteria can be isolated from activated sludge containing Cr(VI) and are regarded as a strain with both Cr(VI) resistance and reducing ability [

29]. Therefore, the presence of Cr(VI) does not have an adverse effect on the viability of

Proteobacteria, which are known to be electroactive bacteria involved in extracellular electron transfer [

30]. Despite toxic stress due to Cr(VI),

Proteobacteria that tolerate toxic stress conditions can rapidly decompose nutrients and pollutants and tenaciously survive. In addition,

Firmicutes, which play an important role in converting refractory substrates into simple organic compounds [

30], increased at Cr(VI) concentration of 2.5 mg/L. Conversely, the relative abundance of

Bacteroidota decreased from 9.2% in the control to 1.4% at Cr(VI) concentration of 2.5 mg/L after 90 days of cultivation.

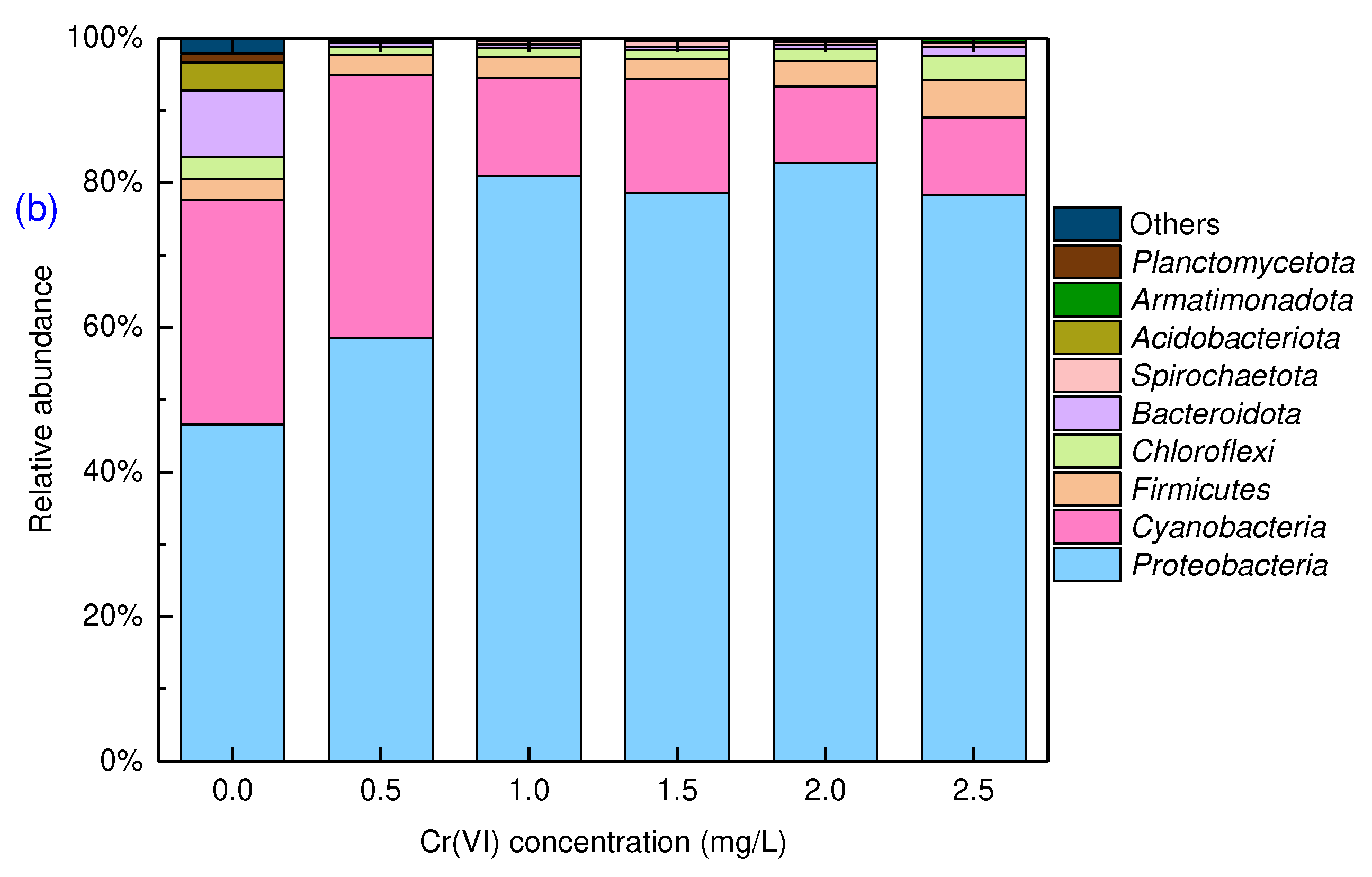

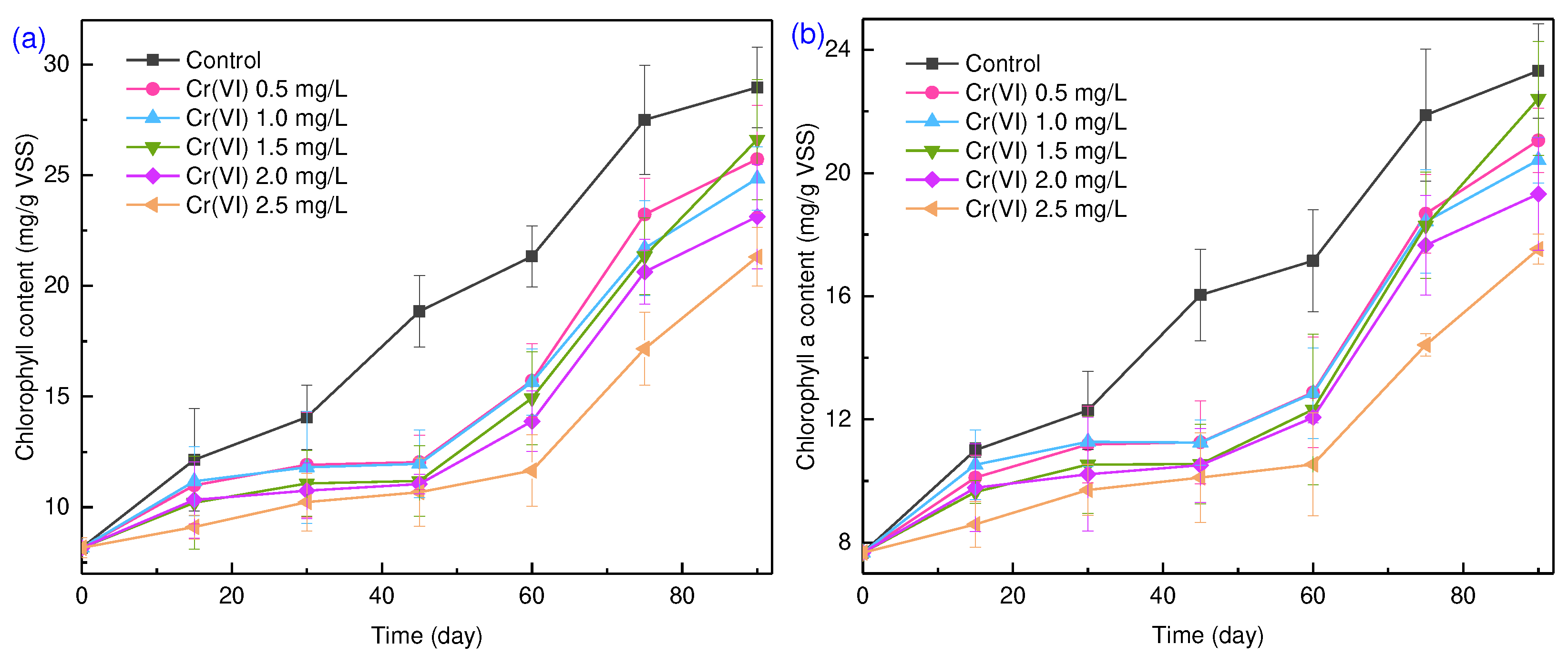

Photosynthetic pigments are usually used to quantify microalgae species. Generally, chlorophyll a exists in all phototrophic microorganisms, including green algae, diatoms and cyanobacteria, and chlorophyll b only exists in green algae [

31]. As shown in

Figure 3a, the total chlorophyll content decreased from 28.9 mg/g VSS in the control to 21.3 mg/g VSS at 2.5 mg/L of Cr(VI), indicating reduced algal biomass due to Cr(VI) interference with electron transport in respiration and photosynthesis. As for cyanobacteria, they decreased under Cr (VI) stress, evidenced by reduced relative abundance (31.0% to 10.8% with increased Cr(VI) concentration (

Figure 2b). Chlorophyll a decreased, while the ratio of chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b showed increasing trend with Cr(VI) concentration (

Figure S4b), indicating that the reduction of green algae was less than that of cyanobacteria.

Photosynthetic pigment is one of the physiological indicators of microalgae under stress, and can directly reflect the damage degree [

32]. Therefore, under Cr(VI) stress, green algae are more robust than cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria are commonly used to adsorb and reduce Cr(VI) to Cr(III), and have been considered as a alterative bioremediation treatment due to their environmental-friendliness and cost-efficiency [

33]. However, it should be noted that it is a suicidal approach to treat Cr (VI), i.e., the relative abundance of cyanobacteria decreased with the increased Cr (VI) concentration (

Figure 3b). A similar phenomenon has been observed in the presence of cadmium [

7], indicating cyanobacteria are more susceptible to heavy metal stress than eukaryotes.

3.4. Defensive responses of algal-bacterial granular sludge under Cr (VI) stress

3.4.1. EPS variations

EPS are complex polymers existing in pure bacteria, activated sludge, granular sludge and microalgae, and are mainly composed of protein (EPS-PN) and polysaccharide (EPS-PS). Biosorption of Cr(VI) onto EPS has been reported as the major mechanism contributing to Cr bioremediation [

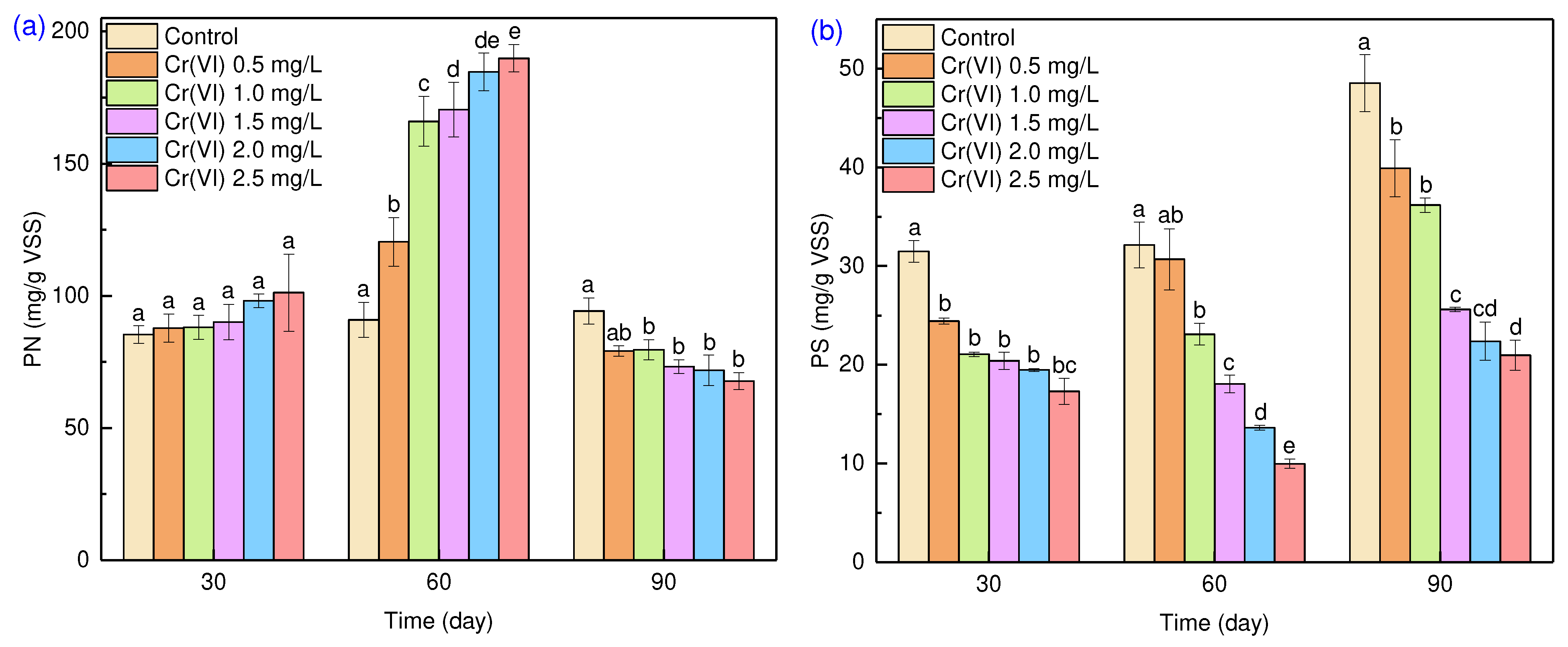

34]. As shown in

Figure 4, EPS-PN content in the control experimental did not change significantly across 90 days of cultivation. The observed variations in the EPS-PN content at Cr(VI) concentrations of 0.5-2.5 mg/L were significant. EPS-PN content increased to 120.4-189.8 mg/g VSS with increased Cr(VI) concentration from 0.5-2.5 mg/L after 60 days of cultivation, indicating that the over-production of EPS-PN was a protective mechanism to eliminate or reduce adverse effects. In contrast, EPS-PN then decreased to 79.1-67.8 mg/g VSS after 90 days of cultivation. In contrast, EPS-PS content decreased with increased C (VI) concentration during the whole cultivation duration. This which might be due to EPS-PS being an energy source that was largely consumed for the over-production of EPS-PN due to Cr(VI) stress [

35].

3D-EEM was used to further analyze the EPS produced, with the results shown in

Figure S4 and

Table S1. Two distinct peaks A and B at the Ex/Em of 290 nm/352 nm and Ex/Em 360 nm/444 nm were observed. Peak A was corresponds to the tryptophan protein-like substances and peak B is identified as being due to humic acid-like substances [

36]. Compared to the control, no obvious wavelength shift was observed in these two peaks, indicating the chemical similarity of EPS-PN produced at different Cr(VI) concentrations. However, the intensities of both peaks A and B increased with Cr(VI) concentrations of 0-2.5 mg/L, implying more adsorption sites in the presence of greater Cr(VI). It should be noted that the fluorescence intensity of peak B was reduced at 2.5 mg/L of Cr (VI)-exposed concentration. Cyanobacteria had been reported to release humic acid-like substances to defend against environmental stress [

37], which further proved the decreased abundance of cyanobacteria (

Figure 2b).

3.4.2. Antioxidant enzyme activity

Generally, algal cells produce a large amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under Cr(VI) stress, which changes the content of photosynthetic pigments in algal cells and damages them [

38]. In a study by [ang,Zhao[

11] a large amount of ROS was found to cause and aggravate the oxidative decomposition of membrane lipids and proteins. During this process, small molecular organic compound MDA was produced which is generally used to evaluate the oxidative stress [

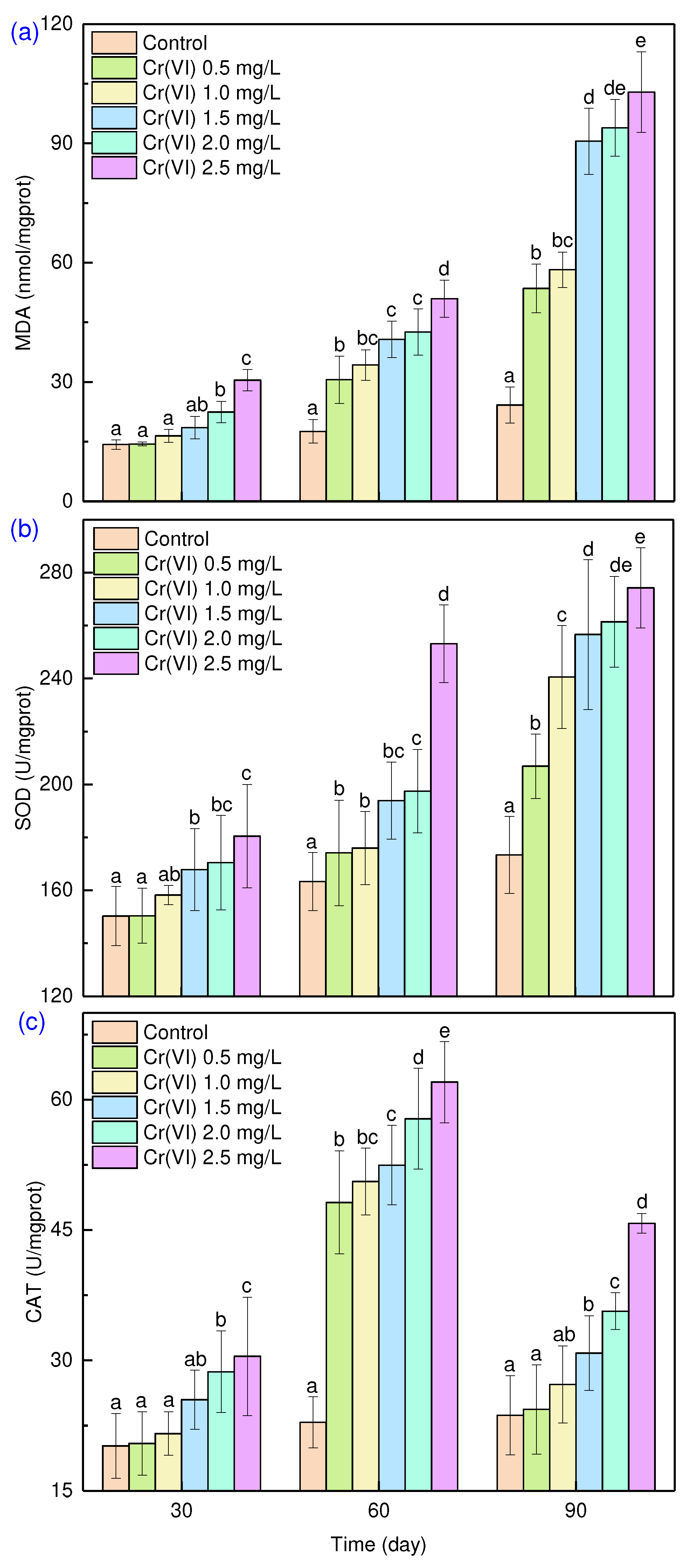

39]. The MDA content in the control changed insignificantly during the 90 days of cultivation (

Figure 5a) but did increase with Cr(VI) concentrations across 0.5-2.5 mg/L. When the Cr(VI) concentration was 2.5 mg/L, the MDA content was 102.9 nmol/mg protein after 90 days of cultivation, suggesting serious oxidative stress and damaged cell membranes caused by Cr(VI).

It should be noted that ammonia-N and phosphate-P removal recovered with time as shown in

Figure 1, indicating effective adaptive strategies. Microalgae synthesize antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD and CAT) and non-enzymatic antioxidants to counteract ROS released by heavy metals during adsorption [

40]. SOD acts as the first line of defense against the superoxide anion by breaking it down into oxygen molecules and hydrogen peroxide [

41]. The hydrogen peroxide is further degraded by CAT into water and oxygen molecules [

42,

43]. In this study, SOD content increased with Cr(VI) concentration in contrast to the control experiment (

Figure 5b). At Cr(VI) concentration of 2.5 mg/L, SOD content reached 274.3 U/mg protein after 90 days of cultivation, demonstrating significant defensive responses to Cr(VI) oxidative stress. A similar trend is apparent for CAT content with Cr(VI) concentration up to 60 days (

Figure 5c). However, CAT content was decreased at 90 days of cultivation, showing a unique self-protection strategy against over-produced ROS. This observation was in consistent with the literature [

43].

3.5. Engineering implications and perspectives

Biological treatment using activated sludge method as its core strategy is generally adopted for wastewater treatment in China. The conventional activated sludge (CAS) process is often accompanied by a large amount of GHG emissions, including carbon dioxide, generated by the oxidation of organic substances in the wastewater, nitrous oxide produced as the intermediate product of biological denitrification, and dissolved methane generated during anaerobic digestion. Additionally, the CAS process requires high energy input to achieve the removal of organic and nutrient substances from wastewater [

44]. GHG emissions generated from wastewater treatment have a negative impact on the global climate. Faced with these challenges and driven by widespread concern for public health and ecological sustainability, wastewater discharge standards have been continuously improved. To date, evidence suggests that effluent water from the proposed algal-bacterial granular sludge process used in bench-scale experiments was able to meet the stringent discharge standards in many countries [

45]. However, the removal rate of pollutants and nutrients may be slowed under nonideal conditions. For example, ammonia nitrogen removal was reduced by nearly 15% by the algal-bacterial granular sludge process after 30 day-cultivation in the presence of 1 mg/L of Cd(Ⅱ) [

7]. A similar inhibitory effect was observed in the presence of sulfamethoxazole [

46]. In this study, 0.5-2.5 mg/L of Cr(VI) resulted in greater COD to differing extents, such that effluent discharge standards were not met. Cr(VI), a Class I pollutant, in the effluent met the discharge standards with Cr(VI) being reduced to relatively innocuous Cr(III). Therefore, when algal-bacterial granular sludge is used to treat Cr(VI)-containing wastewater, further processes need to be superimposed to solve the problem of effluent COD not meeting the discharge standard.

A variety of defense mechanisms including reduced intracellular glycogen content, promote chlorophyll production and increased EPS was found under stimulated conditions [

7,

46]. However, little attention has been paid to the effects of long-term operation. The microbiome of algal-bacterial granular sludge is dynamic and determined by wastewater characteristics and operating conditions. Due to the uneven microbial growth cycle, the role of algae and bacteria in their defense mechanisms against stress is unclear. Although the proposed algal-bacterial granular sludge process is resistant to Cr(VI) in this study, further work is required to explore the specific mechanisms. In addition, Cr(VI) tolerance tests could be helpful for understanding engineering feasibility.

As a single-cell prokaryote, cyanobacteria have obvious competitive advantages in adapting to environmental factors (e.g., light, temperature, and nutrient intake). Therefore, in some situations, cyanobacteria may eventually evolve into the dominant photosynthetic species in algal-bacterial granular sludge [

47]. Since cyanobacteria are mainly distributed in the outer layer of algal-bacterial granular sludge, they are more vulnerable to the impact of the external environment. Algal growth and metabolite production are affected by light, temperature, carbon dioxide concentration, and components in wastewater. So far, the succession of cyanobacteria in algal-bacterial granular sludge is confusing. When the cultivation medium is rich in nutrients and harmful substances, cyanobacteria tend to over propagate, and may release cyanotoxins and adversely affecting water quality. Among the cyanotoxins, microcystins (MCs) are the prevalent class and have a number of variants. Microcystin-LR (MC-LR) is resistant to extreme conditions [

48]. In Chinese hygienic standards for drinking water (GB 5749-2022) the upper limit of 1.0 μg L for MC-LR is strictly specified. Therefore, for the safe practical application of algal-bacterial granular sludge process serious concern about cyanotoxins should be raised.

4. Conclusions

The current study has shown the ability of algal-bacterial granular sludge to remove nutrients and pollutants from wastewater. In this study, new insight into the performance and self-defensive responses of algal-bacterial granular sludge under Cr(VI) stress for a long-term operation was shown for the first time. It was found that the symbiotic relationship between microalgae and bacteria was destroyed in the presence of Cr(VI), evidenced by decreased COD and changed microbial population. Although the ammonia-N and phosphate removal rates were affected at the initial cultivation stage, they did recover gradually. To cope with the stress of Cr(VI), algal-bacterial granular sludge secreted more EPS-PN to provide more adsorption sites for the biological adsorption of Cr(VI) and transfer Cr(VI) to low-toxic form of Cr(III). The activities of SOD and CAT enzymes increased to maintain the stability of microalgal cells and negated the oxidative damage caused by Cr(VI) stress. For the stable operation and engineering feasibility of algal-bacterial granular sludge wastewater processing, further research on how to maintain and restore the removal performance of nutrients and pollutants is necessary. It is hope that this study can provide a useful reference.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1, Energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) of algal-bacterial granular sludge; Figure S2, SEM images of algal-bacterial granular sludge at the initial Cr(VI) concentration of 0 (a), 0.5 (b), 1.0 (c), 1.5 (d), 2.0(e) and 2.5 mg/L (f); Figure S3, Full spectrometric surveying (a) and Cr 2p XPS spectra of algal-bacterial granular sludge cultivated with 2.5 mg/L of Cr (VI) for 90 days (b); Figure S4, Chlorophyll b content (a) and the ratio of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b (b) of the algal-bacterial granular sludge; Figure S5, 3D-EEM fluorescence spectra of EPS after 90 day-operation at Cr(VI) concentrations of 0 (a), 0.5 (b), 1.0 (c), 1.5 (d), 2.0 (e) and 2.5 mg/L (f); Table S1, Fluorescence spectra parameters of EPS in algal-bacterial granular sludge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yu Zhang and Shulian Wang; methodology, Kewu Pi; validation, Kewu Pi; investigation, Shulian Wang and Kewu Pi; data curation, Yu Zhang and Shulian Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Yu Zhang; writing—review and editing, Andrea R. Gerson. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang B, Li W, Guo Y, Zhang Z, Shi W, Cui F, Lens P N L, Tay J H. Microalgal-bacterial consortia: From interspecies interactions to biotechnological applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2020, 118, 109563. [CrossRef]

- Ji B, Wang S, Silva M R U, Zhang M, Liu Y. Microalgal-bacterial granular sludge for municipal wastewater treatment under simulated natural diel cycles: Performances-metabolic pathways-microbial community nexus. Algal Research, 2021, 54, 102198. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Lei Z, Wei Y, Wang Q, Tian C, Shimizu K, Zhang Z, Adachi Y, Lee D J. Behavior of algal-bacterial granular sludge in a novel closed photo-sequencing batch reactor under no external O2 supply. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 318, 124190. [CrossRef]

- Ji B and Liu, C. CO2 improves the microalgal-bacterial granular sludge towards carbonnegative wastewater treatment. Water Research, 2022, 208, 117865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Ji B, Liu Y. Microalgal-bacterial granular sludge process: A game changer of future municipal wastewater treatment? Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 752, 141957. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Fan H, Liu Y, Liu C, Huang X. Development of algae-bacteria granular consortia in photo-sequencing batch reactor. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 232, 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Ji B, Cui B, Ma Y, Guo D, Liu Y. Cadmium-effect on performance and symbiotic relationship of microalgal-bacterial granules. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, 282, 125383. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Nguyen V B, Zhao Z, Wu Y, Lei Z, Zhang Z, Le X S, Lu H. Changes of distribution and chemical speciation of metals in hexavalent chromium loaded algal-bacterial aerobic granular sludge before and after hydrothermal treatment. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 355, 127229. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Wang H, Nie Q, Ding Y, Lei Z, Zhang Z, Shimizu K, Yuan T. Pb(II) bioremediation using fresh algal-bacterial aerobic granular sludge and its underlying mechanisms highlighting the role of extracellular polymeric substances. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023, 444, 130452. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhao Z, Zhang G, Hirayama S, Nguyen B V, Lei Z, Shimizu K, Zhang Z. Insight into Cr(VI) biosorption onto algal-bacterial granular sludge: Cr(VI) bioreduction and its intracellular accumulation in addition to the effects of environmental factors. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 414, 125479. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhao Z, Yu Y, Shimizu K, Zhang Z, Lei Z, Lee D-J. Enhanced biosorption of Cr(VI) from synthetic wastewater using algal-bacterial aerobic granular sludge: Batch experiments, kinetics and mechanisms. Separation and Purification Technology, 2020, 251, 117323. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhao Z, Nguyen B V, Hirayama S, Tian C, Lei Z, Shimizu K, Zhang Z. Cr(VI) bioremediation by active algal-bacterial aerobic granular sludge: Importance of microbial viability, contribution of microalgae and fractionation of loaded Cr. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 418, 126342. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Chen X M, Wang C, Ruan C, Liu X L, Song S. Optimization of immobilized microorganisms technology to Cr (VI) in wastewater. Advanced Materials Research, 2015, 1092-1093, 886-891. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1092-1093.

- WHO (Ed.) World Health Organization Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality, 1, Recommendations (second ed.). ed. WHO. 1993.

- Wang S, Ji B, Zhang M, Gu J, Ma Y, Liu Y. Tetracycline-induced decoupling of symbiosis in microalgal-bacterial granular sludge. Environmental Research, 2021, 197, 111095. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Ji B, Zhang M, Ma Y, Gu J, Liu Y. Defensive responses of microalgal-bacterial granules to tetracycline in municipal wastewater treatment. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 312, 123605. [CrossRef]

- APHA (Ed.) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 21 ed. American Public Health Association, ed. APHA. 2005.

- Ritchie R, J. Measurement of chlorophylls a and b and bacteriochlorophyll a in organisms from hypereutrophic auxinic waters. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2018, 30(6): 3075-3087. [CrossRef]

- Herbert D, Phipps P, Strange R, Chapter III chemical analysis of microbial cells, in Methods in microbiology. 1971, Elsevier. p. 209-344.

- Shulian Wang, Huiqin Zhang, Yu Zhang H G, Pi K. Cultivation of algal-bacterial granular sludge and degradation characteristics of tetracycline. Water Environment Research, 2023, 95, e10846. [CrossRef]

- Ministry. Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants (GB 18918-2002). China Environment Press Beijing, China, 2002.

- Council O E C. Directive concerning urban wastewater treatment (91/271/EEC)

. ed. O.E.C. Council. 1991.

- Wang L, Liu X, Lee D J, Tay J H, Zhang Y, Wan C L, Chen X F. Recent advances on biosorption by aerobic granular sludge. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2018, 357, 253–270. [CrossRef]

- Priatni S, Ratnaningrum D, Warya S, Audina E. Phycobiliproteins production and heavy metals reduction ability of Porphyridium sp. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2018, 160, 012006. 10.1088/1755–1315/160/1/012006.

- Pradhan D, Sukla L B, Mishra B B, Devi N. Biosorption for removal of hexavalent chromium using microalgae Scenedesmus sp. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 209, 617–629. [CrossRef]

- Leong Y K and Chang J, S. Bioremediation of heavy metals using microalgae: Recent advances and mechanisms. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 303, 122886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Yang F, Dai M, Ali I, Shen X, Hou X, Alhewairini S S, Peng C, Naz I. Application of microbial immobilization technology for remediation of Cr(VI) contamination: A review. Chemosphere, 2022, 286, 131721. [CrossRef]

- Kafil M, Berninger F, Koutra E, Kornaros M. Utilization of the microalga Scenedesmus quadricauda for hexavalent chromium bioremediation and biodiesel production. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 346, 126665. [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia L, Cerdeira S B, Vullo D L. Chromium (VI) biotransformation by β- and γ-Proteobacteria from natural polluted environments: A combined biological and chemical treatment for industrial wastes. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2010, 175(1-3): 104-110. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Liu B, Meng S, Wang Y, Yan L, Zhang X, Wei D. Microbial fuel cell enhanced pollutants removal in a solid-phase biological denitrification reactor: System performance, bioelectricity generation and microbial community analysis. Bioresource Technology, 2021, 341, 125909. [CrossRef]

- Abouhend A S, Milferstedt K, Hamelin J, Ansari A A, Butler C, Carbajal-González B I, Park C. Growth progression of oxygenic photogranules and its impact on bioactivity for aeration-free wastewater treatment. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(1): 486-496. [CrossRef]

- Sytar O, Kumar A, Latowski D, Kuczynska P, Strzałka K, Prasad M N V. Heavy metal-induced oxidative damage, defense reactions, and detoxification mechanisms in plants. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, 2013, 35(4): 985-999. [CrossRef]

- Colica G, Mecarozzi P C, De Philippis R. Treatment of Cr(VI)-containing wastewaters with exopolysaccharide-producing cyanobacteria in pilot flow through and batch systems. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2010, 87(5): 1953-61. [CrossRef]

- Hedayatkhah A, Cretoiu M S, Emtiazi G, Stal L J, Bolhuis H. Bioremediation of chromium contaminated water by diatoms with concomitant lipid accumulation for biofuel production. Journal of Environmental Management, 2018, 227, 313–320. [CrossRef]

- Pandey L K and Bergey E, A. Metal toxicity and recovery response of riverine periphytic algae. Science of The Total Environment, 2018, 642, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen C, Paul W, A. L J, Karl B. Fluorescence excitation−emission matrix regional integration to quantify spectra for dissolved organic matter. Environmental Science & Technology, 2003, 37, 5701–5710 101021/es034354c.

- Jiao Y, Zhu Y, Chen M, Wan L, Zhao Y, Gao J, Liao M, Tian X. The humic acid-like substances released from Microcystis aeruginosa contribute to defending against smaller-sized microplastics. Chemosphere, 2022, 303, 135034. [CrossRef]

- Rezayian M, Niknam V, Ebrahimzadeh H. Oxidative damage and antioxidative system in algae. Toxicology Reports, 2019, 6, 1309–1313. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Su L, Yin X, Pei Y. Responses of Chlorella vulgaris exposed to boron: Mechanisms of toxicity assessed by multiple endpoints. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2019, 70, 103208. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay A K, Mandotra S K, Kumar N, Singh N K, Singh L, Rai U N. Augmentation of arsenic enhances lipid yield and defense responses in alga Nannochloropsis sp. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 221, 430–437. [CrossRef]

- Hong Y, Liu S, Lin X, Li J, Yi Z, Al-Rasheid K A. Recognizing the importance of exposure-dose-response dynamics for ecotoxicity assessment: nitrofurazone-induced antioxidase activity and mRNA expression in model protozoan Euplotes vannus. Environmental Science And Pollution Research, 2015, 22(12): 9544-9553. [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro O M and Akinloye O, A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 2018, 54(4): 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Pandey L K, Kumar D, Yadav A, Rai J, Gaur J P. Morphological abnormalities in periphytic diatoms as a tool for biomonitoring of heavy metal pollution in a river. Ecological Indicators, 2014, 36, 272–279. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhang M, Liu Y. One step further to closed water loop: Reclamation of municipal wastewater to high-grade product water. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2020, 65(14): 1358-1367. 10. 1360.

- Ji B, Zhang M, Gu J, Ma Y, Liu Y. A self-sustaining synergetic microalgal-bacterial granular sludge process towards energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable municipal wastewater treatment. Water Research, 2020, 179, 115884. [CrossRef]

- Hu G, Fan S, Wang H, Ji B. Adaptation responses of microalgal-bacterial granular sludge to sulfamethoxazole. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 128090. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Lei Z, Liu Y. Microalgal-bacterial granular sludge for municipal wastewater treatment: From concept to practice. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 354, 127201. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Jiao Y, Rao Z. Selective removal of common cyanotoxins: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021, 28(23): 28865-28875. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).