2.1. Equation of the Geodesic line of a Two-Sided 23-λm,n-Vacuum

The shortest distance between two infinitely close points

p1 and

p2 in a curved area of a two-sided 2

3-λm,n-vacuum is defined as an extremal of the functional

where

is a 2-helix (7), integration is performed from point

p1 to point

p2.

We find the equation of this extremal based on the condition that the first variation is equal to zero

Let’s represent expression (9) in the form

or taking into account metrics (3) and (5)

Expression (11) is equal to zero provided that both terms are equal to zero

In §2 in [

3], it was shown that in the most general case, the metric of a local area of a curved 4-dimensional space with any of the 16 possible signatures (22) in [

3], can be represented as a scalar product of two vectors given in distorted affine spaces with corresponding stignatures (see Expressions (18)—(20) in [

3])

where

is vectors defined respectively in the

a-th and

b-th curved affine space with the corresponding stignature (see §2 in [

3]);

is components of the elongation tensor of the axes of the curved region of the

a-th affine space with the corresponding stignature from matrix (2) in [

2]);

is direction cosines between the axes of the curved section of the

a-th affine space with the same stignatura;

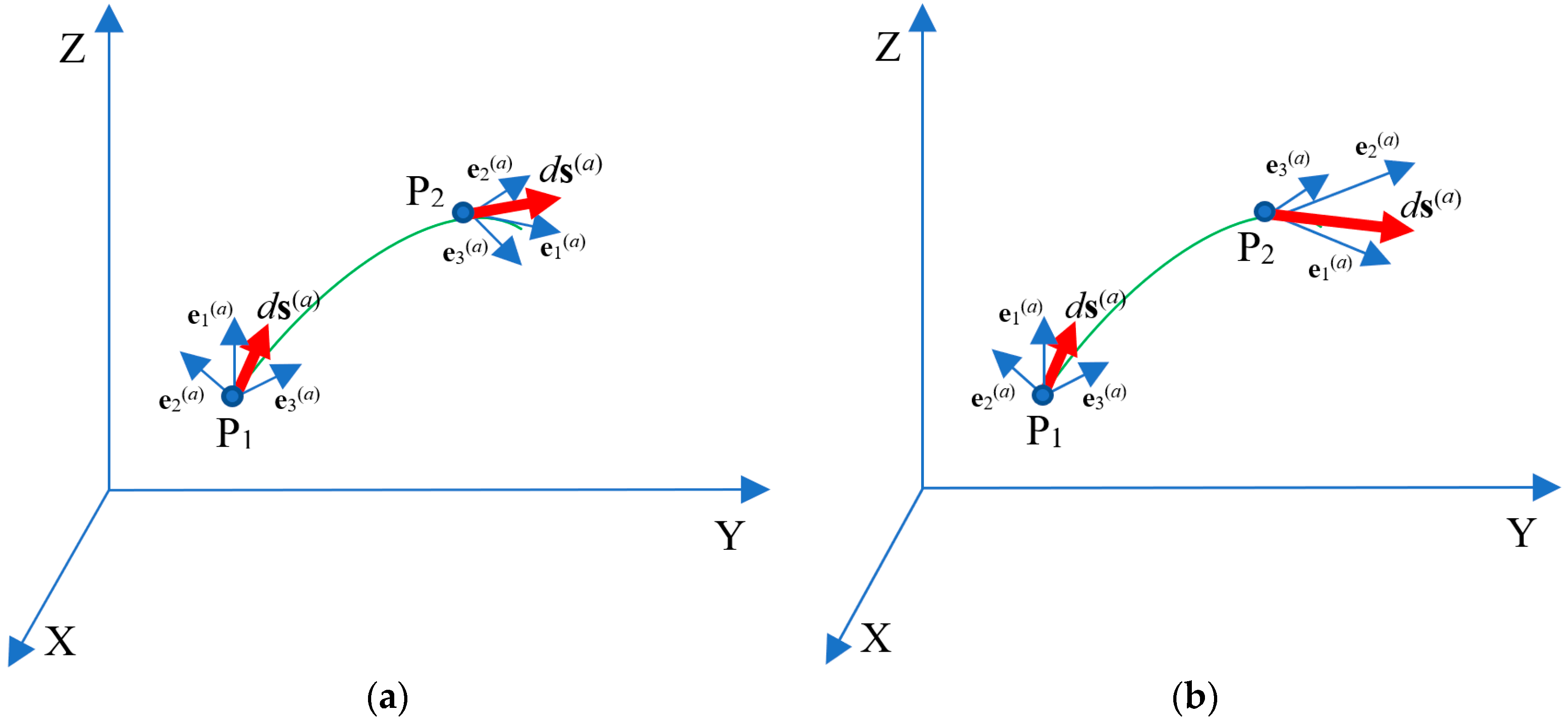

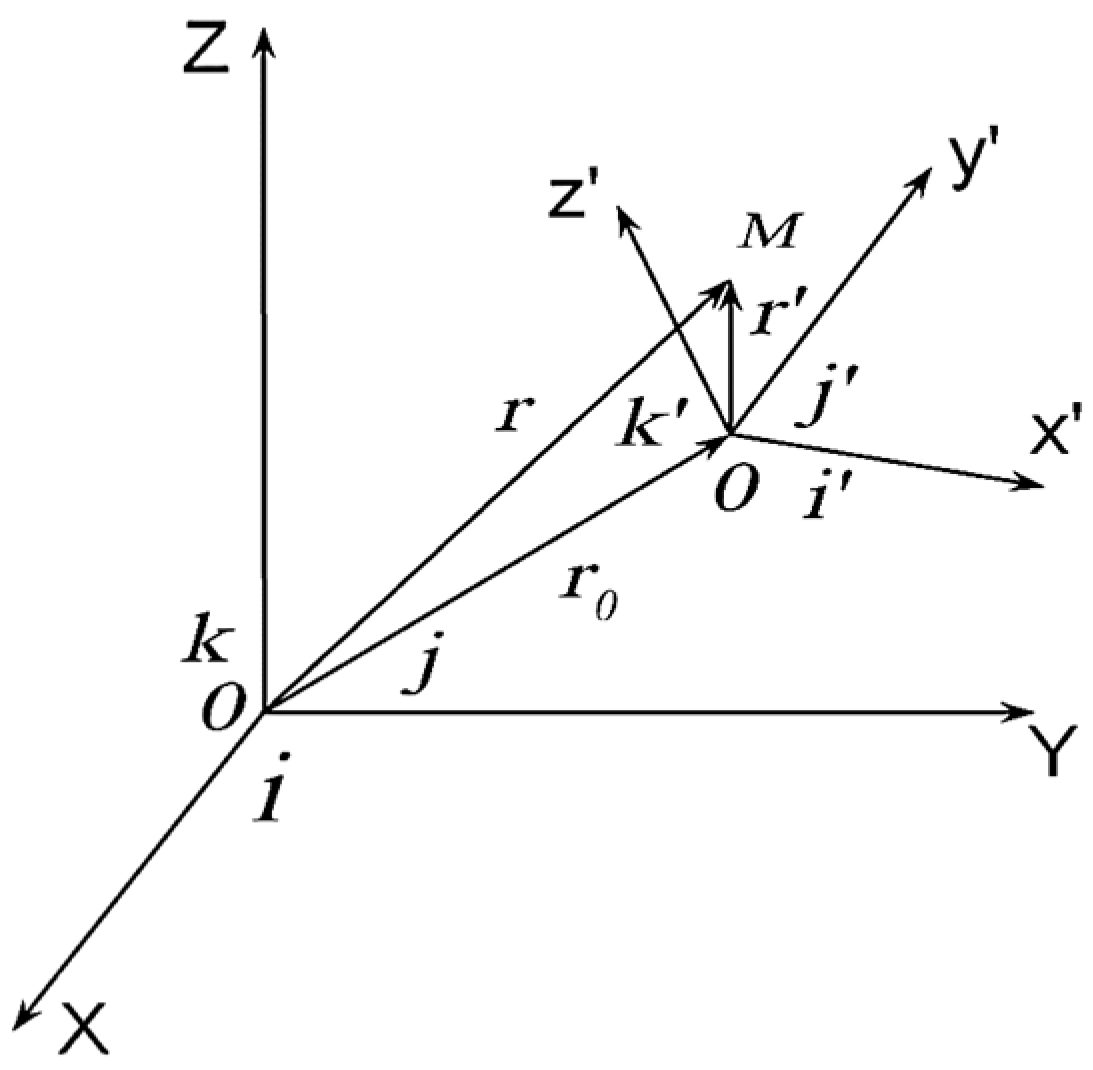

When parallel translation, for example, a vector

ds(a) (or a vector

ds(b)) in a complexly curved, twisted and displaced affine (i.e., vector) space along a geodesic line from point

p1 to a nearby point

p2 (see

Figure 4b), it should be taken into account that the magnitude and direction of this vector may depend on changes in all four parameters

αij(a),

βpm(a),

em(a),

dxj(a). That is, when translating the vector

ds(a from point p

1 to

p2, in the most complex case the following may change (see

Figure 4b): 1) The length of the basis vectors

αij(a); 2) angles between the basis vectors

βpm(a); 3) rotation of the entire 4-basis as a whole

em(a); 4) Displacement of the 4-basis in general

dxj(a). This is due to the fact that the geodesic line between two points

p1 and

p2 of a complexly distorted space can not only be curved, but also deformed, displaced and twisted.

Figure 4.

a) In Riemannian geometry, the parallel translation of the vector ds(a) from point p1 to the nearby point p2 is carried out strictly tangent to the geodesic line connecting these points. In this case, only the direction of this vector changes, and its magnitude remains unchanged. It means that the magnitude of the basis vectors em(а) and the angles between them do not change; b) In the most complexly curved, displaced and twisted space, when transferring (i.e., translation) the vector ds(a) from point p1 to the nearby point p2, its direction, magnitude and displacement may change. When transferring the vector ds(a) in such a complexly distorted space, the magnitude of the basis vectors em(a) and the angles between them can change, and the 4-basis itself as a whole can rotate and shift. In this case, all four parameters of the 4-basis αij(a), βpm(a), em(a), dxj(a) can change, which, according to expression (14), affects the change in the vector ds(a) when it is transferred.

Figure 4.

a) In Riemannian geometry, the parallel translation of the vector ds(a) from point p1 to the nearby point p2 is carried out strictly tangent to the geodesic line connecting these points. In this case, only the direction of this vector changes, and its magnitude remains unchanged. It means that the magnitude of the basis vectors em(а) and the angles between them do not change; b) In the most complexly curved, displaced and twisted space, when transferring (i.e., translation) the vector ds(a) from point p1 to the nearby point p2, its direction, magnitude and displacement may change. When transferring the vector ds(a) in such a complexly distorted space, the magnitude of the basis vectors em(a) and the angles between them can change, and the 4-basis itself as a whole can rotate and shift. In this case, all four parameters of the 4-basis αij(a), βpm(a), em(a), dxj(a) can change, which, according to expression (14), affects the change in the vector ds(a) when it is transferred.

Depending on what distortions, displacements and rotations of the vectors

ds(a) and

ds(b) are taken into account when considering the metric-dynamic properties of curved space, various differential geometries are obtained: for example, Riemannian geometry (see

Figure 4a), Weyl geometry, affine geometry of Eddington, geometry with torsion of Cartan-Schouten, geometry of absolute parallelism of Weizenbeck-Vitali-Shipov [

4], etc.

2.2. Equation of the Geodesic Line of a Two-Sided 23-λm,n-Vacuum in the Case of Riemannian Geometry

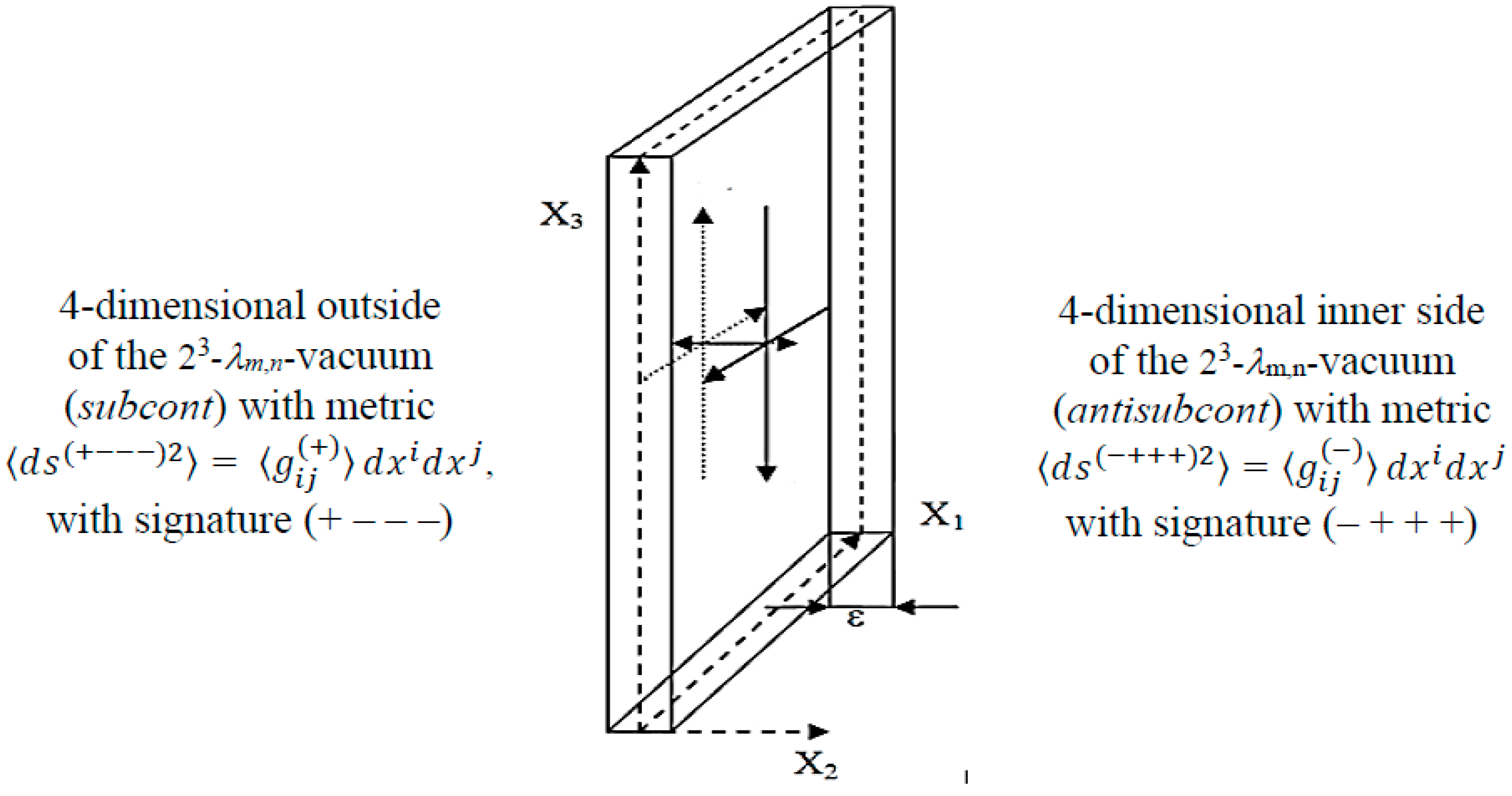

First, let’s assume that the outer and inner 4-dimensional sides of the 2

3-λm,n-vacuum (i.e.,

subcont and

antisubcont) are only curved, i.e., are described by the simplest differential Riemannian geometry (see

Figure 4a). In this case, the extremals of functionals (12) are defined identically, so we introduce a generalized metric

We consider the general case

provided that at the ends of the desired geodesic line

ds (i.e., at points

p1 and

p2) the variations are zero

Let’s use the expression

whence it follows [

5]

where the commutativity of the operations of variation and differentiation

is used.

Let’s substitute Ex. (20) under the integral (17), and divide and multiply this expression by

ds, as a result we obtain [

5]

We integrate the expression in parentheses by parts [

5]:

The first term in this expression, due to conditions (18), becomes zero. Let’s substitute the remaining part of expression (22) into equation (21) and perform differentiation, as a result we obtain [

5]:

From the fact that integral (23) vanishes for any variations of

δхμ, it follows that the expression enclosed in curly brackets is equal to zero. From where, taking into account the relation

, after simple calculations we obtain the equation of the geodesic line [

5]:

where

(

s) is coordinates of the curved line.

Equation (24) is intended to determine the extremal of functional (17) with simplifications related to Riemannian geometry (

Figure 4a). This equation determines the most optimal (geodesic) line connecting two close points

p1 and

p2 in a curved 4-dimensional space. That is, this is a line that, under the above conditions, allows you to get from point

p1 to the nearby point

p2 in the shortest time and with the least energy costs.

At the same time, Equation (24) can be represented in the form

this equation defines the 4-acceleration field

, which can be interpreted as a massless force field

where

is the mass of a body that is carried away by a continuous “medium”, which moving with acceleration

.

At this stage of research, it is difficult to explain what is meant by a force field in vacuum physics. However, it is possible to compare the acceleration of a local section of the vacuum layer with the accelerated movement of a small volume of liquid in the general flow of the river. Such an accelerated flow carries with it everything that comes in its way and makes it move with the same acceleration. From the point of view of post-Newtonian physics, if a body moves with acceleration, then a force acts on it. Therefore, the accelerated movement of the local volume of a 3-dimensional medium (in this case, subcont, or antisubcont) can be interpreted as a local force effect.

Performing separately similar operations (17) – (24) for variations (12), we obtain two equations

where respectively

is Christoffel symbols of a

subcont;

is Christoffel symbols of a

antisubcont;

When considering variation (11), taking into account the Christoffel symbols (29) and (30), we find that the sought-for extremal of the functional (8), with simplifications related to Riemannian geometry, is determined by the following equation of a geodesic line in a curved two-sided 2

3-λm,n-vacuum

or

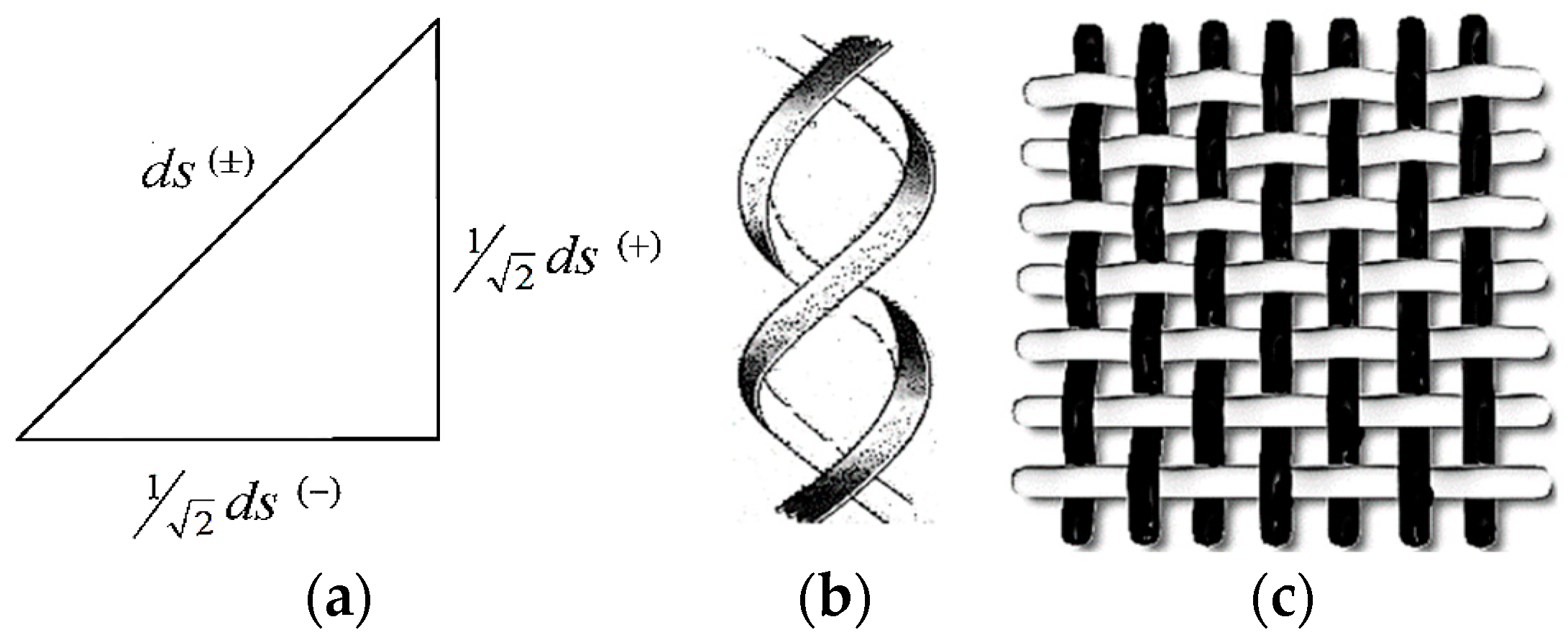

Ex. (31) shows that the geodesic lines of the

subcont and

antisubcont, i.e., two mutually opposite sides of the local section of the two-sided 2

3-λm,n-vacuum is twisted into a 2-spiral. This is similar to how rivulets twist in a freely falling jet of liquid (see

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Many streams in a freely falling stream of liquid twist into a spiral.

Figure 5.

Many streams in a freely falling stream of liquid twist into a spiral.

Continuing the analogy with liquid, it should be noted that within the framework of the Algebra of Signature, a two-sided 2

3-λm,n-vacuum can be represented as an interweaving (mixing) of two liquids (

subcont and

antisubcomt), which can be conditionally “colored” in white and black colors (see

Figure 6). These two conjugate “liquids” cannot separately move in a straight line; they are interconnected and can move in one direction only by twisting into a 2-helix.

Figure 6.

Illustrations of mixing of white and black “liquids”.

Figure 6.

Illustrations of mixing of white and black “liquids”.

2.3. Equation of the Geodesic Line of a 16-sided 26-λm,n-Vacuum in the Case of Riemannian Geometry

In the previous paragraph, we considered the most simplified model representation of the interweaving of geodesic lines of a two-sided 23-λm,n-vacuum which can be interpreted as mixing and interweaving of flows of two liquids: conventionally “white” and “black”). With a more detailed examination of such conjugate “multi-colored” liquids there should be 16. With an even more detailed examination of these liquids there are already 256 and so on ad infinitum.

More in-depth and accurate is the sixteen-sided consideration of the local area of the 2

6-λm,n-vacuum (see §3 and §5.3 in [

3]). In this case, the curved state of the 2

6-λm,n-vacuum is described by a superposition (averaging) not of two, as in the previous paragraph, but of sixteen 4-metrics (see Ex. (25) in [

3]).

where

is components of the metric tensor of the

q-th metric space with a signature from the matrix (22) in [

3]:

In the framework of the Algebra of Signature, Ex. (33) is called a 16-braid, which is formed by the additive superposition of sixteen 4-dimensional metric spaces (see §5.3 in [

3]). In this case, a section of a 16-braid is formed from sixteen intertwined “colored” lines (spiral threads)

ds(q), and is described by Ex. (69) in [

3]

where

ηm (

m = 1,2,3,…,16) is an orthonormal basis of objects (similar to the imaginary unit

i) satisfying the anticommutative Clifford algebra relation (68) in [

3]

where

δnm is the unit 16×16 matrix.

For example, let‘s imagine a segment of a 16-helix (36) as a sum of two complex conjugated 8-helices (octonions) with signatures {+ – – –} and {– + + +}

where

,

where the objects

ζr (where

r = 1, 2, 3, … ,8), as well as the objects ηm, satisfy the anticommutative relations of the Clifford algebra:

where

δkm is the Kronecker symbol (

δkm = 0 for

m ≠

k and

δkm = 1 for

m =

k).

These requirements are satisfied, for example, by a set of 8×8 matrices of type (65) in [

1]:

In this case,

δkm is a unit 8×8-matrix:

Similarly, the objects ηm can be represented by sixteen 16x16 matrices.

Let’s look at the functional

where

ds(16) is a segment of the 16-helix (36).

Let’s equate the first variation of this functional to zero

With each term

ηqδfrom Ex. (45) we perform operations like (17) – (24), as a result we obtain the extremal equation for a geodesic line in a curved 16-sided 2

6-λm,n-vacuum

or

where

is Christoffel symbols of the

q-th metric space with components of the metric tensor

with the corresponding signature from matrix (35).

Ex. (46) shows that at this level of consideration, the curved area of the 2

6-λm,n-vacuum is a complex interweaving of the 16-“colored” geodesic lines (see

Figure 7). In this case, the 16-strains of the same section of the 2

6-λm,n-vacuum are described by the strain tensor (63) in [

3].

At the same time, the equation of geodesic lines (46) can be represented in the form.

which defines the field of 4-accelerations

, i.e., total massless force field (see

Figure 7)

where

is the mass of the body that is carried away by the total (more precisely averaged) accelerated flow.

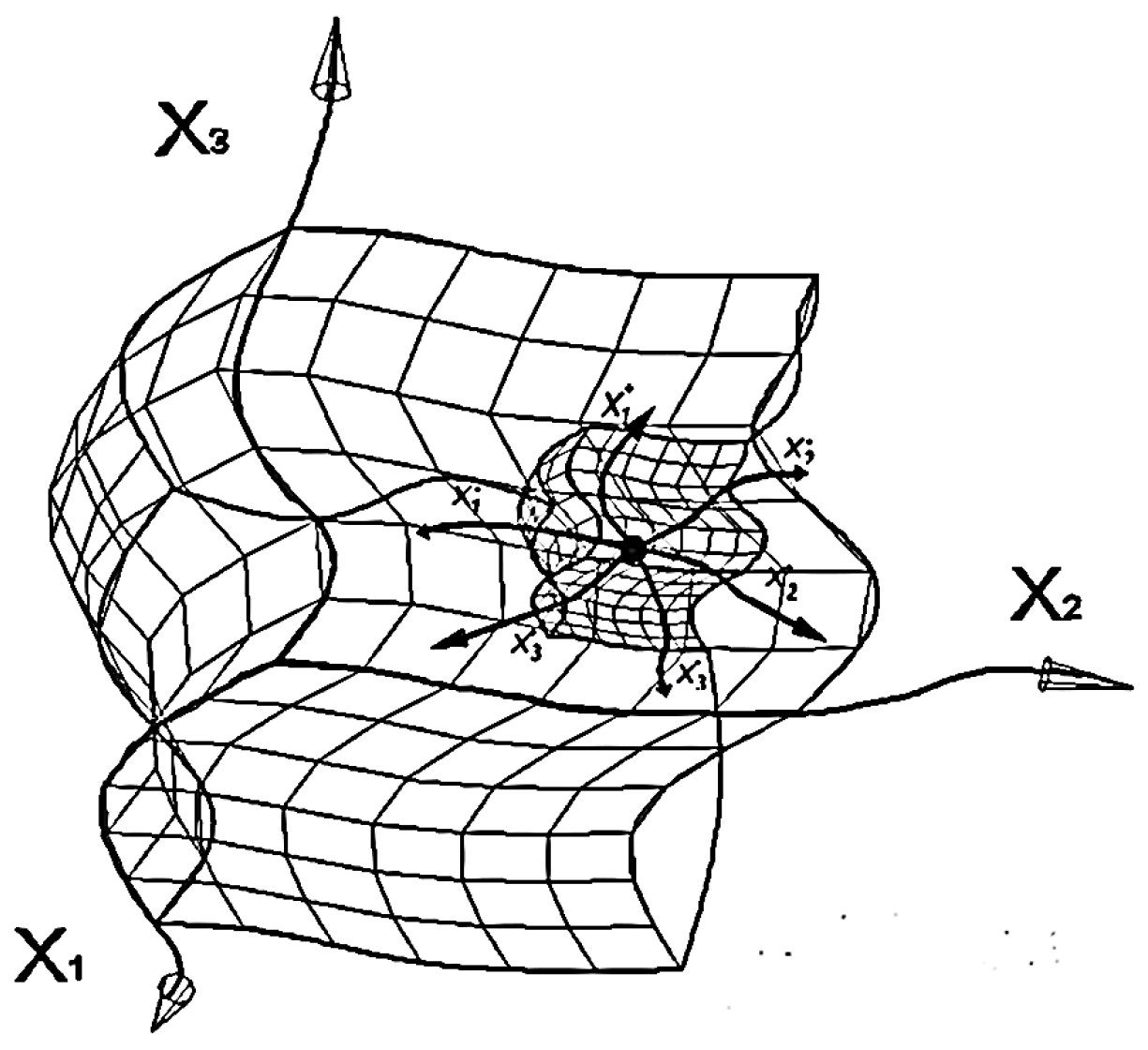

Figure 7.

Fractal illustration of the interweaving of 16-“colored” geodesic lines, (i.e., accelerated streams or currents) forming the fabric of the 26-λm,n-vacuum.

Figure 7.

Fractal illustration of the interweaving of 16-“colored” geodesic lines, (i.e., accelerated streams or currents) forming the fabric of the 26-λm,n-vacuum.

The next level of consideration is the 2

10-λm,n-vacuum, which is considered as the result of the interweaving of not 16, but 256 metric intra-vacuum layers (see §2.9 in [

2] and § 5.3 in [

3]). In this case, the curved area of 2

6-λm,n-vacuum is the result of averaging 265-deformations of the curved area of the 2

10-λm,n-vacuum, just as the curved area of the 2

3-λm,n-vacuum is the result of averaging 16-deformations of the curved area 2

6-λm,n-vacuum.

A more sophisticated consideration of the curvature of the

λm,n-vacuum area can be continued to infinity by a multiple of 2

k (see § 2.9 in [

2]). In this case, each time the metric-dynamics of the subsequent transverse level of consideration of the 2

k-λm,n-vacuum is the result of averaging (i.e., in fact, coarsening) of the metric-dynamics of the previous, much more finely and elegantly arranged level 2

k+l-λm,n-vacuum.