1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is becoming the most common cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. The condition encompasses a spectrum of conditions going from nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) or simple steatosis, characterized by hepatic triglyceride accumulation in the hepatocytes without inflammation, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) which is represented by steatosis plus liver inflammation, and finally hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

1].

The incidence and prevalence of NAFLD had a rapid and significant rise in the last decades worldwide [

2,

3]. A recent meta-analysis on the prevalence of NAFLD, which considered 92 studies from 1990 to 2019 in the general adult population aged > 20 years for a total of more than 9 million subjects, estimated its average prevalence of 30.69%, with peaks around 44% in Latin America. In Western Europe an estimated prevalence of 25.1% (20.55%-30.28%), for a total of approximately 366,000 patients, is reported [

4]. This study has also documented a 50% increase in its prevalence from 1990-2006 to 2016-2019 time frames: from 25.25% in 1990-2006 to 38.2% in 2016-2019 [

4].

Regarding the incidence of NAFLD, even if the data on it are more scarce, because of the lack of methodologically correct studies on this matter, the abovementioned metanalysis reported an increase of about 58% from 1994-2006 to 2010-2014, with an estimation of 28.9 cases per 1000 person-year, with a strong correlation with older age (>50 years) and obesity, which is closely related to the increased incidence of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in the general population [

4,

5].

Recently, it has been proposed to change the nomenclature of this clinical entity: from NAFLD to Metabolic-dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease—MASLD. This new definition, expression of a Delphi consensus promoted by international hepatological Scientific Societies, is aimed at emphasize the close epidemiological, pathophysiological and clinical relationship that bidirectionally correlates hepatic steatosis with metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity and dyslipidemia (low HDL cholesterol and/or hypertriglyceridemia)[

6]. The need for the change in nomenclature was dictated by the fact that the “old” definition of NAFLD was limited by providing a diagnosis of exclusion, therefore not considering a possible and common mixed metabolic and alcoholic and/or viral etiology of the liver disease. Moreover, NAFLD also carried two terminological stigmata towards the patient and society such as “non-alcoholic” and “fatty”[

6]. Previously, also an “intermediate” proposal of “Metabolic-dysfunction Associated Fatty Liver Disease—MAFLD” was made, then changed to MASLD to overcome the “fatty” stigma. However, either MAFLD or MASLD definitions have been criticized in the recent past by other experts highlighting that the new nomenclature could be premature and confusing since the molecular basis of the disease entity is still not totally clear, and almost the entirety of the epidemiological, pathophysiological, diagnostic and therapeutical trials data on this disease are still referred to the old definition [

7]. Regarding NASH, the expert consensus agreed to retain the name “steato-hepatitis”, being it very descriptive of it pathophysiological bases [

6]. Therefore, the acronym “MASH—Metabolic-dysfunction Associated Steatohepatitis” has been proposed. Anyway, for the present review we will retain the old nomenclature of NAFLD and NASH, precisely because the aforementioned amount of literature data is referred to it.

NASH is characterized by the presence of hepatocellular injury, with lobular inflammation and hepatocellular swelling (“ballooning”) independent of the presence or absence of fibrosis. Its prevalence is expected to increase by up to 56% by 2030 in China, Europe, Japan, UK, and USA [

8]. It is a chronic liver disease that can progress to the stage of liver cirrhosis and lead to organ failure [

9]. The continuous mechanisms of tissue damage and regeneration typical of NASH chronic inflammation can determine both sustained hepatic fibrogenesis, responsible for cirrhosis, and the onset of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

10].

Liver cancer is the fifth most common diagnosed cancer and fourth-leading cause of cancer death worldwide [

11], and HCC is the most common primary liver cancer comprising of 75%–85% of cases. It accounts for the 5,4% of worldwide cancers [

12]. HCC has a male predominance (ratio male/female 3:1) with a mortality rate two to three times higher in men than women [

10,

12] Women also tend to present more often with non-cirrhotic HCC than men and have less advanced disease at presentation with greater overall survival [

13]. NAFLD-related HCC tends to occur in older individuals and to be diagnosed at a later stage [

10]. This last characteristic is also due to the fact that NAFLD-related HCC is also well known to develop in the absence of liver cirrhosis, unlike liver diseases of other etiologies such as alcohol-related and autoimmune liver disease [

14]. Therefore, the absence of HCC screening protocols in patients with NAFLD but without cirrhosis contributes to the late diagnosis and management. It is likely that the rates of NAFLD-related HCC will increase in parallel with the obesity epidemic. In the last decade, growing evidence has supported a trend toward NASH overtaking viral hepatitis as the leading cause of HCC in western countries [

15].

In this Review, we discuss the global epidemiology, trends, and projections for NAFLD-related HCC. We highlight data regarding HCC pathophysiology in patients with non-cirrhotic NAFLD and surveillance strategies in patients without cirrhosis. In addition, we review the risk factors for NAFLD-related HCC and discuss preventive and therapeutic measures.

2. Global Incidence of NAFLD-Related HCC

The annual incidence of HCC in the NASH patient cohort in Europe and the United States ranges from 0.7% to 2.6% depending on age, metabolic profile, and the presence or severity of liver decompensation; the incidence of HCC appears to be higher in men, in diabetics and in older age [

10,

13,

14].

As already mentioned, due to the pathogenetic and molecular mechanisms of NAFLD, hepatic carcinoma can also arise in a non-cirrhotic liver; the incidence of HCC in patients with non-cirrhotic NAFLD ranges from 0.1 to 1.3 per 1000 person-years [

14,

16].

2.1. HCC in Cirrhotic NASH

Liver cirrhosis is the strongest risk factor for the development of HCC in NAFLD patients; more than two-thirds of cases occur in cirrhosis patients and the incidence rate is 25-fold higher in NAFLD patients with advanced fibrosis [

17]. A systematic review of cross-sectional studies reports a prevalence of 5–7% of HCC within the NAFLD cirrhotic population [

18].

Table 1 summarizes the studies reporting the incidence of HCC in NASH-cirrhotic cohort studies.

The development of HCC results from a combination of chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, mitochondrial damage from fat accumulation, and chronic cytokine dysregulation. All together leads to the patient with NAFLD or NASH developing HCC [

27]. A retrospective study compared the incidence of HCC development in cirrhotic patients secondary to HCV or NASH. They noticed that HCV-cirrhotic patients developed HCC almost two-fold compared to NASH cirrhotic [

20]. Although the incidence of HCC development is lower in NASH patients, the overall burden of NAFLD and NASH would suggest that the absolute number of patients developing NAFLD-related HCC will increase in the future [

16].

Primary liver cancer (especially HCC) develops in 2.4%-12.8% of patients with NAFLD cirrhosis annually [

28].

2.2. HCC in Non-Cirrhotic NASH

Even if cirrhosis remains the most important cause for the development of HCC, in NAFLD patients, HCC can develop even in the absence of cirrhosis.

About 20% of HCCs are not preceded by cirrhosis (NCHCC); generally, liver cancer not preceded by cirrhosis is discovered at a later stage and characterized by a larger mass, the presence of extra-hepatic metastases and the possible occurrence of symptoms such as weight loss, asthenia, fatigue, abdominal pain and bleeding; it is usually associated with a poorer prognosis since the therapeutic option of a large surgical resection would require an early diagnosis. The M/F ratio is also more tending towards parity contrary to the predilection for the male sex present in the form of HCC preceded by cirrhosis [

29]. In

Table 2 are summarized the studies reporting the incidence of HCC in NASH-non cirrhotic cohort studies.

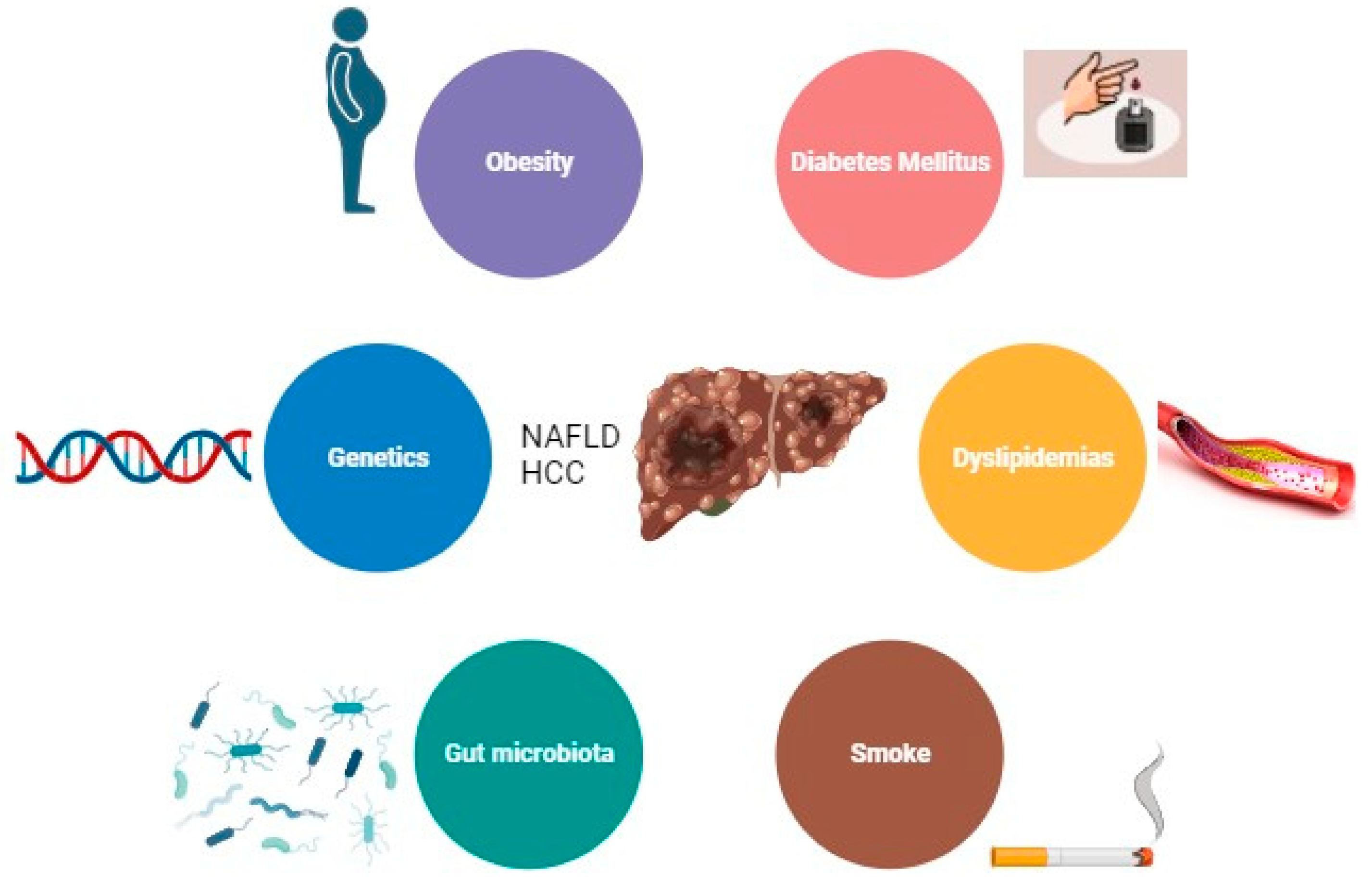

3. Risk Factors for NAFLD-Related HCC

The main risk factor for the development of HCC is the presence of liver cirrhosis [

17]. Other major risk factors among patients with NAFLD, are obesity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia [

32]. Emerging data also implicate gut dysbiosis and inflammation as additional key risk factors for HCC development in patients with NAFLD. However, there are other demographic, metabolic, genetic, and environmental factors that have been associated with the development of NAFLD [

2] (

Figure 1).

3.1. Obesity

Obesity and NAFLD/NASH are becoming the leading contributing factors to the rising incidence of HCC [

33]. Obesity is a major driver of NAFLD and NASH, [

2] and it is associated with a 2-3 fold increased risk of HCC [

34]. Notably, obesity itself is an independent risk factor for the onset and development of HCC.

In a retrospective cohort study of 271906 patients with diagnosed NAFLD, it has been shown that 8.38% subjects developed cirrhosis and 253 were diagnosed with HCC (0.09% of patients with NAFLD and 1.11% of with cirrhosis, respectively) [

33].

In another analysis, which analyzed 25,337 HCC patients from a total of 26 prospective studies, overweight and obesity increased the risk of HCC by 18% and 83%, respectively, regardless of gender and geographical location. The incidence was found to be higher in men than in women, but this could be derived from the different distribution of adipose tissue with a higher percentage of visceral obesity in men [

35].

The exact biological mechanisms linking weight gain and HCC have not yet been fully elucidated; however, it can be assumed that the development of NAFLD and NASH represent milestones. In fact, obesity and the resulting insulin resistance favor the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6, responsible for the development of hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and the onset of HCC [

36].

Considering only abdominal obesity, rather than the BMI index, an even closer relationship emerges between obesity, NAFLD and HCC; in fact, in a detailed analysis of the risk of developing HCC, waist and hip circumference, waist-to-hip (WHR) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) have been described positively associated with risk of HCC. In particular, WHtR showed the strongest association with HCC [

37].

These parameters appear to be more predictive and worthy of greater attention as they identify more precisely the visceral fat, responsible for the basic metabolic and inflammatory activity and effector of the damage.

3.2. Diabetes Mellitus

The association between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and NAFLD is strongly supported by several studies [

19,

38,

39].

A study of Mayo Clinic and UNOS on 6984 patients demonstrated that diabetes is involved not only in the onset of NASH (as part of the metabolic syndrome), but also in the progression of liver disease and in the onset of cirrhosis following NAFLD [

39]. Diabetes promotes hepatocarcinogenesis by constituting a chronic inflammatory state that favors the release of proinflammatory cytokines (leptin and TNF-α) and the formation of oxygen free radicals (ROS). ROS cause genomic instability, promote cell differentiation and inhibit apoptosis. In addition, diabetes is associated with hyperinsulinemia and IGF-1-activated growth factors. Insulin and IGF-1 act on the PI3K/AKT and MAPK molecular pathways. The activation of PI3K/AKT leads to inhibition of apoptosis and the increase of growth and cell survival by signaling on cyclin D1, p53 and Mtor; the activation of MAPK stimulates the transcription of protooncogenes explaining the high incidence of HCC in diabetic patients [

30].

A retrospective analysis on patients with and without DM, demonstrating that diabetics were older, predominantly female, had metabolic syndrome, and had NAFLD as the underlying etiology. Moreover, in a median follow-up period of 6 months among 156 patients without cirrhosis, a higher proportion (43% vs 27%) of diabetics than non-diabetics developed cirrhosis. Similarly, over a median follow-up of 3 years, among 359 patients with cirrhosis at or during follow-up, a higher proportion of diabetics (22% vs 5%) developed HCC. Interestingly, oral antidiabetic drugs (e.g., Metformin or Thiazolidinedones) because of their intrinsic mechanism of action which counteracts insulin resistance have been demonstrated to be more effective in controlling the progression of liver damage when compared with insulin therapy [

38].

3.3. Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemias is one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, closely related to the metabolic syndrome and the condition of obesity [

40].

Liver cells are primarily affected by ectopic accumulation of lipids as the liver is the major regulator of systemic accumulation of lipids and glucose. Fatty liver is associated with dyslipidemia and dysglycemia independently of visceral fat [

41]. Consequently, NAFLD and NASH are the most common liver disorders in dyslipidemia, strongly associated with insulin resistance, increased risk of progression to liver cirrhosis and possible onset of HCC [

42].

Adipocytes play a crucial role in the tumor microenvironment through the secretion of several molecular mediators. In fact, adipose tissue secretes adipokines such as leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and inflammatory mediators, such as ANGPTL2, which modulate insulin sensitivity and trigger chronic low-grade inflammation. A dysregulated secretion of adipokines by adipocytes contributes to the development of obesity-related metabolic disorders [

43].

The importance of dyslipidemia in the onset of NAFLD and the correlated HCC-NAFLD is explained by the suggestion of the use of statins as anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and anti-proliferative drugs [

16]. These effects are not directly referable to the action of the drug, but to the preventive action on lipotoxicity [

42].

3.4. Smoke

Smoking has been associated with an increased risk for the development of HCC [

25,

44], although no studies have specifically examined the association between smoking and NAFLD-related HCC.

Tobacco carcinogens are metabolized in the liver and the formation of DNA adducts could constitute the important initiator of hepatocarcinogenesis [

45].

3.5. Gut Microbiota

Alterations of the intestinal microbiota, namely dysbiosis, have been associated with the spectrum of NAFLD [

46,

47]. Moreover, in fecal samples of cirrhotic patients with HCC it has been reported an overall decrease in microbial diversity with an increase in Gram negative bacteria, predominantly Escherichia coli [

48,

49]. The disruption of intestinal enterocyte intercellular tight junctions contributes to the onset of NAFLD, increasing gut permeability and translocation of gut bacteria (mainly Gram-negative bacteria) and lipopolysaccharides; this stimulates TLR4 at the hepatic level leading to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis [

48,

50]

The gut microbiota is involved in the choline metabolism, whose reduced levels are reflected in the liver, where they cause abnormal phospholipid synthesis and VLDL secretion. At least eight microbial species present in the intestine promote the metabolization of choline to TMA (trimethyllamine). From a clinical point of view, in addition to the hepatic consequences resulting from the very low secretion of VLDL, there is an increased risk of cardiovascular and renal diseases due to the hepatic metabolization of TMA into TMAO (trimethyllamine-N-oxide) [

48].

On regards of NAFLD-HCC specifically, a recent work by Ponziani et al., demonstrated as those NAFLD subjects with HCC and cirrhosis have a peculiar gut-microbiota profile with a lack of protective species compared to cirrhotic patients without HCC. This finding was associated with an enhanced intestinal inflammation that may have favored hepatocarcinogenesis through the expression of several inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, also opening the discussion on a possible therapeutical role of gut-microbiota modulating agents (i.e., probiotics) or fecal transplantation in preventing HCC in NAFLD patients [

51].

The intestinal microbiota has also a role in controlling the composition of bile acids [

46,

52]. Bile acids have a metabolic effect on NAFLD predominantly through two nuclear receptors: FXR (Farnesoid X Receptor) for primary bile acids and TGR5 for secondary. FXR activation is due to either bile acids themselves or FGF19, a gut hormone released in response to FXR activation. This pathway also affects glucose homeostasis and lipogenesis, reducing de novo synthesis and promoting β-oxidation of fatty acids, maintaining blood glucose and lipid levels in a normal range. TGR5 affects glucose homeostasis, energy expenditure by activation of thyroid hormones, and inflammation, which is negatively regulated [

53,

54].

Finally, patients with NAFLD have an alteration in the ratio of secondary to primary bile acids with loss of the beneficial antisteatotic and anti-inflammatory effects, and a higher concentrations of bile acids in the hepatic circulation. High levels of bile acids are able to activate inflammatory- and oxidative stress-mediated cell death pathways, suggesting that bile acids may be involved in the pathogenesis of liver injury and potentially initiation of cancerous activity, particularly in the colon or the liver where the secondary bile acids concentrate [

55,

56].

3.6. Genetics

Genetic factors are thought to contribute to 30-50% of diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerotic disease, and cirrhosis. Genetic polymorphisms (SNPs) in a number of genes have been associated with the presence of NAFLD and risk of disease progression to advanced fibrosis and HCC [

57].

Two genes are considered most involved in the predisposition and development of NAFLD: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) and transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2).

The PNPLA3 mutation rs738409, encoding an I148M mutation, is independently associated with NAFLD, fibrosis progression, and an increased risk of HCC development [

58]. This SNP has been reported to impair mobilization of triglycerides from hepatic lipid droplet, leading to an increase in hepatic fat content but not with alterations in glucose homeostasis and lipoprotein metabolism [

59].

In a multivariate analysis that also included the presence of diabetes, BMI, age and gender, the presence of the PNPLA3 mutation was shown to increase the risk of HCC by 2.3 times in heterozygotes and by 5 times in homozygotes [

59].

The rs58542926 variant in the TM6SF2 gene, encoding an E167K mutation, is associated both to hepatic steatosis and an increased risk of liver fibrosis, however its role in HCC development remains uncertain. The accumulation of triglycerides in the liver is due to the loss of function of this transporter with the inability to secrete lipoproteins rich in triglycerides and apolipoprotein. However, the inability to secrete VLDL reduces the incidence of cardiovascular disease in carriers of this polymorphism [

60].

In a further study on individuals of European origin, the SNP rs641738 in the locus near MBOAT7/TMC4 gene has been demonstrated associated with the severity of NAFLD [

61]. This association is mediated by a decreased protein expression of MBOAT7 with consequent changes in the remodeling of the hepatic phosphatidylinositol acyl chain [

62].

A study carried out in the UK found two mutations responsible for insulin resistance: the mutation (rs1044498, K121Q) of the ENPP1 gene and the mutation (rs1801278, Q972R) in the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1); both mutations, by reducing insulin sensitivity, were, independently of other factors, involved in NAFLD with a higher risk of progression to fibrosis [

57].

Glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR) regulates glucokinase activity and has been associated with NAFLD in the presence of the P446L mutation which reduces the ability of GCKR to inhibit glucokinase in response to fructose-6-phosphate, thereby increasing the activity of the glucokinase and hepatic glucose absorption. The resulting uncontrolled hepatic glycolysis reduces glucose and insulin levels and increases the production of malonyl-CoA, promoting hepatic lipid accumulation. GCKR variants have been associated with fibrosis following NASH [

63].

Considering the genes involved in oxidative stress, individuals carrying the variant SNP rs4880 of SOD2, have a 1.56-fold increased risk of developing advanced fibrosis [

57].

An important role in the progression of fatty liver disease is also played by epigenetic regulation. Methylation of genes generally leads to a reduction in the expression of the gene product. Hypermethylation of the 99 CpG island in the regulatory region of PNPLA3 affects its expression and has been associated with advanced liver fibrosis. Furthermore, CpG99 methylation levels and PNPLA3 mRNA are affected by PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype [

64].

More recently, genetic variants have been combined into “polygenic risk scores”. These genetic variants are associated with HCC risk in individuals with multiple underlying liver diseases [

65,

66].

4. NAFLD Clinical Aspects and Complications

NAFLD is often asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed during medical evaluations (especially during liver ultrasonography) for other reasons or identified based on clinical features of the metabolic syndrome [

67,

68]. As already mentioned, NAFLD is considered the hepatic expression of the “metabolic syndrome”; therefore it is easy to comprehend how the main cause of mortality and morbidity in NAFLD subjects is represented by cardiovascular complications, driven mainly by atherosclerosis, valvular calcifications and increased intimal arterial thickness [

69,

70,

71]. Moreover, compared to individuals without NAFLD, patients with fatty liver disease already show an elevated risk of CV events independently of the presence of other metabolic syndrome components, a risk that is further increased in the presence of liver fibrosis, making it a independent cardiovascular risk factor [

72,

73].

On the other hand, the main liver-related complications of NAFLD and NASH are cirrhosis and HCC [

74]. In case of cirrhosis, the presence of connective and fibrotic tissue in place of the liver parenchyma prevents the organ from functioning correctly; however, a patient with compensated cirrhosis is usually asymptomatic and diagnosed when incidental tests, such as liver transaminases (which, in turn, are not considered to be as good as in other etiologies in predicting NAFLD onset and evolution, being very frequently within the range of normality even in the presence of an evolutive form of steatotic liver disease), or radiologic findings suggest liver disease and patients undergo further. Every year about 10% of patients with “compensated” cirrhosis progress towards the “decompensated” form. The initial clinical presentation of patients with decompensated cirrhosis is the presence of dramatic and life-threatening complications, such as variceal hemorrhage, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy [

75].

The subversion of the hepatic architecture is responsible for the onset of portal hypertension (hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) ≥5 mmHg). When it becomes clinically relevant (HVPG≥10 mmHg), it becomes detectable by clinical and ultrasonographical signs (i.e., spleen enlargement, hypersplenism etc) and it is responsible of the formation of porto-systemic shunts such as congestive gastropathy and esophageal varices [

76]. With its further worsening (when HVPG≥12 mmHg), portal hypertension can manifest with its complications: ruptured esophageal varices with hematemesis and melena, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy [

77].

5. Prevention and treatment

Treatment of NAFLD can be divided into specific treatment of NAFLD-related liver disease, treatment of NAFLD-associated comorbidities, and treatment of complications of advanced NAFLD [

78].

5.1. Prevention and Treatment of Comorbidities Associated with NAFLD

To date, there are no specific pharmacological therapies for NAFLD, so the major treatment for NAFLD remains lifestyle changes including weight reduction and performing regular physical activity. In fact, a 7-10% weight loss allows the reduction of cardiovascular risk factors and the improvement of liver histology [

79]. A Cuban study on 261 patients with NAFLD biopsied shows that subjects who achieved a 10% reduction in body weight, observed NASH resolution in 90% of cases and regression of fibrosis in 45% [

80]. The Mediterranean diet can reduce hepatic steatosis, improves plasma lipid levels and fatty acid oxidation by reducing their accumulation, and has a synergistic effect in reducing cardiovascular risk [

81,

82]. Importantly, physical activity, independently of weight reduction, improves liver histological status and potentially prevents the onset of HCC by improving mitochondrial functions such as biogenesis, autophagy, and modulation of cancer signaling pathways [

80].

The adoption of a correct lifestyle is usually sufficient to avoid the onset of steatosis although NAFLD is also based on a genetic substrate and foresees a role played by alterations of the intestinal microbiota; the adoption of a correct lifestyle, associated with the use of probiotics or symbiotics to modulate the gut microbiome could represent a promising new therapeutic strategy in NAFLD [

83].

Patients with NAFLD and BMI ≥35 kg/m

2 could be considered for bariatric surgery. A meta-analysis showed improvement in steatosis, steatohepatitis, and fibrosis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery [

84]. These results were recently confirmed in a multicenter randomized open label trial in which bariatric surgery showed an higher efficacy in NASH resolution in respect to lifestyle intervention in patients with obesity and biopsy-proven NASH [

85].

5.2. Pharmacological Treatment of NAFLD-Related Liver Disease

When lifestyle changes are not sufficient, a pharmacological therapy should be indicated. Several drugs have been proposed, targeting directly or indirectly, the major components of the pathophysiology of inflammation and fibrosis in NAFLD[

86]. A comprehensive report on these molecules is beyond the scopes of the present review, for this reason only the most recent and/or promising and/or discussed treatments are here reported.

Statins, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, are the major lipid-lowering drugs prescribed; their act by reducing the endogenous production of cholesterol with partial resolution of the liver histology, but also by their effects anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic [

87]. A recent metanalysis showed that statins have significant therapeutic effects, significantly reducing liver biochemical indicators in patients with NAFLD [

88]. Moreover, they could reduce the risk of HCC in NAFLD patients younger than 65 years of age [

89]. Therefore, further studies, prospectively analyzing these aspects in NAFLD patients are advisable.

Among antidiabetic drugs, thiazolidinediones, and Pioglitazione in particular, showed good results in terms of liver histology of diabetic patients with NAFLD [

90]. They act by promoting the differentiation of adipocytes into smaller cells, more sensitive to insulin, and by inducing lipoprotein lipase, promoting the synthesis and uptake of fats in adipose tissue and the reduction of storage in the liver and muscles [

91]. However, even if there are some evidence that it could exert some beneficial effects in non-diabetic patients with NAFLD, its use is, at the moment, suggested only in type 2 diabetic patients with NAFLD [

79,

92].

Recent studies are evaluating the effects of GLP-1 agonists on liver. Liraglutide appears to be able to inhibit de novo lipogenesis in the liver and to improve the sensitivity of cells to insulin [

93,

94]. Similarly, Semaglutide, a second-generation GLP-1-RA, which is available in both oral (daily administration) and subcutaneous (weekly administration) formulations, has demonstrated to have favorable effects on NAFLD patients. In fact, Treatment with 24 weeks of Semaglutide could significantly improve liver enzymes, reduce liver stiffness, and improve metabolic parameters in patients with NAFLD/NASH. The major concern with these type of drugs are the gastrointestinal adverse events [

95].

Other studies have demonstrated a reduction in necroinflammation and ballooning degeneration, with resolution of NASH in a proportion of cases after the intake of high doses (800 IU/day) of vitamin E, which has an antioxidant action [

96,

97]. However, its use in NAFLD is, at least, controversial because of existing concerns about its long-term safety, in terms of the reported increase in all-cause mortality [

98], increased risk of haemorrhagic stroke [

99] and prostate cancer in men over 50 years of age [

100], therefore the Italian Guidelines for NAFLD management suggest to discuss its use with every single patient [

92] and EASL suggest only a short-term treatment for non-diabetic adults with biopsy-proven NASH, and to avoid it in diabetic patients, NAFLD without liver biopsy, NASH cirrhosis, or cryptogenic cirrhosis [

101,

102].

Finally, very recently, other studies have reported on a new class of drugs which is the “dual agonist drugs”, such as Efinopegdutide and Tirzepatide, in patients with NAFLD, obesity and/or type 2 diabetes [

103,

104]. This new class of drugs is composed by a GLP-1 agonist associated with a Glucagon-receptor agonist and has been initially proposed (and, for Tirzepatide only, approved) for the treatment of obesity and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus [

105,

106,

107,

108]. Tirzepatide has shown, in a post-hoc analysis of a phase 2 trial carried out on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, significantly decreased NASH-related biomarkers and increased adiponectin [

104]. Efinopegdutide has been recently reported to have a higher efficacy in reducing liver fat content in respect to Semaglutide alone in a phase 2a-active comparator-controlled study on NAFLD patients [

103]. Further studies are necessary to confirm these preliminary results.

5.3. Drug Treatment for NAFLD Complications: Fibrosis, Cirrhosis and HCC

Obeticholic acid, a farnesoid X receptor agonist, is the only drug shown to improve fibrosis without worsening NASH; however, it is necessary to point out that its use has been related also to the side effect of LDL hypercholesterolemia which further increases the cardiovascular risk of these patients [

80]. However, Food and Drug Administration, following the presentation of the interim results of the REGENERATE trial of its use in pre-cirrhotic patients with NASH, did not approve the drug for use in NASH, because, even if it demonstrated the improvement of fibrosis without worsening of NASH, it failed to achieve the primary endpoint of resolution of NASH and no worsening of fibrosis [

109,

110,

111].

Cenicriviroc, a dual antagonist of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5, localized on stellate and Kuppfer’s cells, has been tested in NASH subjects. The pathophysiological basis was that the antagonization of these receptors blocks hyperinflammation and fibrogenesis [

112]. According to the phase 2b CENTAUR study, an improvement in NASH was found without worsening of fibrosis one year after treatment, with the only side effect, clinically asymptomatic, of an increase in lipases. However, unfortunately, the drug did not pass the phase 3 trial, because of similar proportion of patients receiving the drug or the placebo achieved the primary endpoint [

113,

114].

In conclusion, at the time of this review, no pharmacological therapy has been approved precisely for the cure of NAFLD/NASH, and, whereas several molecules are a various levels of experimental development, just as many promising therapies have failed at the interim analyses of the phase 3 studies by not achieving the primary endpoints proposed by FDA and EMA for considering them efficacious in NAFLD/NASH: i) resolution of NASH by histology without worsening of fibrosis and/or ii) improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH. The causes of these failures are complex and multifaceted and are related to the complexity of the pathophysiology of NAFLD itself, together with the uncertainties on the assessment of its diagnosis and progression/regression. These aspects make difficult to identify the right therapy for the right patients, thus dooming potentially promising drugs to failure [

115].

6. Prevention and Treatment of NAFLD-HCC

Treatment options for HCC can be classified into surgical resection and non-surgical therapies [

11]. As described above, physical activity, reduces HCC risk beyond the confounding effects of weight loss. The EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort) study demonstrated an inverse association between physical activity and risk of HCC, independently of body weight and other common risk factors for HCC [

116].

6.1. Pharmacological Treatment of NAFLD-Related HCC

Metformin, the drug used in the first line in the pharmacological therapy of TD2M, has not demonstrated benefits on liver histology; however, this drug would potentially be able to reduce the incidence of HCC in patients with NASH as, through AMP, it activates the protein kinase that downregulates c-Myc as demonstrated in a mouse model [

16]. Even if there are no clinical trials to date which have demonstrated such protective effect in humans, there are some epidemiological evidences that seem to confirm a decrease in incidence of NAFLD-related HCC in patients treated with Metformin[

117]. However, further studies, in form of clinical trials, are advisable to confirm these preliminary results.

Recent findings suggest that immunotherapy is promising to reduce the recurrence of HCC and provides treatment options for advanced HCC that is not suitable for surgical resection. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the last years has approved several drugs for systemic HCC treatment, such as Sorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor [

118], Lenvatinib [

119], atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab [

120,

121]. However, these clinical trials testified the efficacy of immunotherapy only in patients with unresectable or advanced HCC.

7. General Management Strategies for NAFLD Complications: Fibrosis, Cirrhosis, and HCC

To date, the main management strategy in the case of cirrhosis and fibrosis is identical to the chronic liver diseases of other etiologies. In particular, it is aimed at controlling the underlying condition and secondary prevention of complications. Patients with cirrhosis will have to undergo periodic control esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS) to evaluate esophageal varices and to eventually proceed with their ligation; in these subjects the use of non-selective β-blockers to prevent their enlargement is also indicated [

122]. In the case of ascites, a low sodium diet and the combined use of aldosterone antagonists and furosemide should be implemented [

123]. In case of portal hypertension, which is unresponsive to standard treatments, thus causing repeated complications such as variceal bleeding and/or refractory ascites, the ultimate therapy represented by TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Porto-systemic Shunt), an interventional radiology procedure in which a connection is made between the portal vein and the hepatic vein [

124].

International guidelines suggest that, in the presence of liver cirrhosis of any etiology, which is considered the major driver of hepatocarcinogenesis, an active surveillance ultrasound is indicated every 4-6 months, aimed at the early identification of potentially neoplastic nodules. Nodule smaller than 1cm, should be followed with a closer ultrasound check (every 3 months) to monitor the growth more accurately. If the nodule is larger than 1cm, more in-depth examinations such as Contrast enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) or CT/MRI with contrast are indicated. For a definitive diagnosis, liver biopsy is indicated [

125,

126]. However, in NAFLD patients, on this point there is a controversy related to the already mentioned eventuality of HCC occurrence in absence of a clinically/histologically demonstrated cirrhosis, thus raising a discussion on what type of patient with NAFLD and without cirrhosis should undergo a more intensive surveillance for HCC [

127,

128].

The BCLC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer) system used for staging liver cancer, takes into account the number and size of the tumor, the stage of the underlying liver disease (portal hypertension and Child-Pugh class) and the patient’s condition, dividing them into 5 stages: stages 0 and A, B, C and D [

129].

In stages 0 and A, it is possible to do therapy with curative intent by resection and ablation. Liver transplantation is the best option for patients who meet the Milan criteria: single tumor <5cm or less than three tumors each <3cm. In stage B, transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) is indicated; it blocks the hepatic artery to deliver massive doses of chemotherapy with minimal systemic toxicity; it is not applicable in the presence of cirrhosis and portal hypertension due to the vascular consequences induced by these stages. In the advanced stage (BCLC C), systemic therapy with VEGF inhibitors and, recently, with immune checkpoint inhibitors is indicated. However, there are several concerns regarding the literature data that seem to indicate that precisely NAFLD related HCC is less chemosensitive to these new treatments in respect to those related to viral etiologies[

130]. Terminally ill patients are placed in stage D and, to date, are only eligible for supportive care [

125].

8. Conclusion

In conclusion, the fat accumulation in the hepatocytes (namely liver steatosis) associated with lipids and sugars metabolism derangements, a condition which went under the name of Non-Alcoholic Fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and now has been categorized as Metabolic Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD), represents a continuously increasing challenge for the physicians and researcher who are facing (and more and more in future they will) several issues related to its increasing epidemiology and diffusion, diagnostic and management issues, therapeutical problems and, finally, the problematic HCC surveillance, diagnosis and management.

Author Contributions

Ideation, B.M.M. and M.P.; literature search, B.M.M., M.M., P.T..; writing—original draft preparation, B.M.M. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, B.M.M., M.M. and M.P.; supervision, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, L.A., et al., The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology, 2005. 129(1): p. 113-21. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M., et al., Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology, 2016. 64(1): p. 73-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28431. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019. 4(5): p. 389-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30039-1. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M., et al., The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology, 2023. 77(4): p. 1335-1347. https://doi.org/10.1097/hep.0000000000000004. [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M., G. Targher, and C.P. Day, Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013. 10(6): p. 330-44. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.41. [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E., et al., A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/hep.0000000000000696. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M., et al., From NAFLD to MAFLD: Implications of a Premature Change in Terminology. Hepatology, 2021. 73(3): p. 1194-1198. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31420. [CrossRef]

- Estes, C., et al., Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol, 2018. 69(4): p. 896-904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S., et al., Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018. 15(6): p. 349-364. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-018-0009-6. [CrossRef]

- Piscaglia, F., et al., Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multicenter prospective study. Hepatology, 2016. 63(3): p. 827-38. doi:10.1002/hep.28368. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D., et al., A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019. 16(10): p. 589-604. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F., et al., Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018. 68(6): p. 394-424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492. [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M., et al., Gender Matters: Characteristics of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Women From a Large, Multicenter Study in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol, 2020. 115(9): p. 1486-1495. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000643. [CrossRef]

- Desai, A., et al., Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: A comprehensive review. World J Hepatol, 2019. 11(1): p. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.1. [CrossRef]

- Hester, D., et al., Among Medicare Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease is the Most Common Etiology and Cause of Mortality. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2020. 54(5): p. 459-467. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001172. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Q., H.B. El-Serag, and R. Loomba, Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021. 18(4): p. 223-238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y., et al., Large-scale long-term follow-up study of Japanese patients with non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease for the onset of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012. 107(2): p. 253-61. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.327. [CrossRef]

- White, D.L., F. Kanwal, and H.B. El-Serag, Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk for hepatocellular cancer, based on systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012. 10(12): p. 1342-1359.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.001. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M., et al., Risks and clinical predictors of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma diagnoses in adults with diagnosed NAFLD: real-world study of 18 million patients in four European cohorts. BMC Med, 2019. 17(1): p. 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1321-x. [CrossRef]

- Ascha, M.S., et al., The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology, 2010. 51(6): p. 1972-8. doi:10.1002/hep.23527. [CrossRef]

- Bhala, N., et al., The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis: an international collaborative study. Hepatology, 2011. 54(4): p. 1208-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24491. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, E., et al., Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol, 2009. 44 Suppl 19: p. 89-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00099-5. [CrossRef]

- Kodama, K., et al., Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in cirrhosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2013. 37 Suppl 1: p. E247-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01900.x. [CrossRef]

- Marot, A., et al., Alcoholic liver disease confers a worse prognosis than HCV infection and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among patients with cirrhosis: An observational study. PLoS One, 2017. 12(10): p. e0186715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186715. [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez, E., et al., Fibrosis Severity as a Determinant of Cause-Specific Mortality in Patients With Advanced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Multi-National Cohort Study. Gastroenterology, 2018. 155(2): p. 443-457.e17. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.034. [CrossRef]

- Yatsuji, S., et al., Clinical features and outcomes of cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis compared with cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009. 24(2): p. 248-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05640.x. [CrossRef]

- Geh, D., D.M. Manas, and H.L. Reeves, Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-a review of an emerging challenge facing clinicians. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2021. 10(1): p. 59-75. https://doi.org/10.21037/hbsn.2019.08.08. [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M., et al., From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019. 16(7): p. 411-428. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-019-0145-7. [CrossRef]

- Stine, J.G., et al., Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis compared to other liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2018. 48(7): p. 696-703. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14937. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F., et al., Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology, 2018. 155(6): p. 1828-1837.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.024. [CrossRef]

- Orci, L.A., et al., Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022. 20(2): p. 283-292.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.002. [CrossRef]

- Cotter, T.G. and M. Rinella, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease 2020: The State of the Disease. Gastroenterology, 2020. 158(7): p. 1851-1864. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.052. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F., et al., Effect of Metabolic Traits on the Risk of Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Cancer in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology, 2020. 71(3): p. 808-819. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31014. [CrossRef]

- Hagström, H., P. Tynelius, and F. Rasmussen, High BMI in late adolescence predicts future severe liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a national, population-based cohort study in 1.2 million men. Gut, 2018. 67(8): p. 1536-1542. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313622. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., Excess body weight and the risk of primary liver cancer: an updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Cancer, 2012. 48(14): p. 2137-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.063. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., et al., Obesity contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development via immunosuppressive microenvironment remodeling. Front Immunol, 2023. 14: p. 1166440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1166440. [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, S., et al., Abdominal obesity, weight gain during adulthood and risk of liver and biliary tract cancer in a European cohort. Int J Cancer, 2013. 132(3): p. 645-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27645. [CrossRef]

- Raff, E.J., et al., Diabetes Mellitus Predicts Occurrence of Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Cancer in Alcoholic Liver and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases. J Clin Transl Hepatol, 2015. 3(1): p. 9-16. https://doi.org/10.14218/jcth.2015.00001. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D., et al., Diabetes Is Associated With Increased Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis From Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology, 2020. 71(3): p. 907-916. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30858. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.M., J. Tuomilehto, and L. Ryden, The metabolic syndrome—What is it and how should it be managed? Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2019. 26(2_suppl): p. 33-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319886404. [CrossRef]

- Speliotes, E.K., et al., Fatty liver is associated with dyslipidemia and dysglycemia independent of visceral fat: the Framingham Heart Study. Hepatology, 2010. 51(6): p. 1979-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23593. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, Y. and D. Sarkar, Association of Adipose Tissue and Adipokines with Development of Obesity-Induced Liver Cancer. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22042163. [CrossRef]

- Unamuno, X., et al., Adipokine dysregulation and adipose tissue inflammation in human obesity. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2018. 48(9). https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12997. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, O., et al., Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for the development of and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: An updated systematic review of 81 epidemiological studies. J Evid Based Med, 2017. 10(4): p. 245-254. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12270. [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.L., et al., Tobacco, alcohol use and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: The Liver Cancer Pooling Project. Br J Cancer, 2018. 118(7): p. 1005-1012. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0007-z. [CrossRef]

- Mouzaki, M. and R. Loomba, Insights into the evolving role of the gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: rationale and prospects for therapeutic intervention. Therap Adv Gastroenterol, 2019. 12: p. 1756284819858470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756284819858470. [CrossRef]

- Boursier, J., et al., The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology, 2016. 63(3): p. 764-75. doi:10.1002/hep.28356. [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, S.R., V. Ajmera, and R. Loomba, Emerging Role of the Gut Microbiome in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Composition to Function. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019. 17(2): p. 296-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.065. [CrossRef]

- Grat, M., et al., Profile of Gut Microbiota Associated With the Presence of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Transplant Proc, 2016. 48(5): p. 1687-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.01.077. [CrossRef]

- Miele, L., et al., Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology, 2009. 49(6): p. 1877-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22848. [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.R., et al., Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Associated With Gut Microbiota Profile and Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology, 2019. 69(1): p. 107-120. doi:10.1002/hep.30036. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Talavera, O., et al., Bile Acid Control of Metabolism and Inflammation in Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Dyslipidemia, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology, 2017. 152(7): p. 1679-1694.e3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.055. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y.L. and J.M. Ferrell, Bile acid receptors FXR and TGR5 signaling in fatty liver diseases and therapy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2020. 318(3): p. G554-G573. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00223.2019. [CrossRef]

- Cariello, M., E. Piccinin, and A. Moschetta, Transcriptional Regulation of Metabolic Pathways via Lipid-Sensing Nuclear Receptors PPARs, FXR, and LXR in NASH. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021. 11(5): p. 1519-1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.01.012. [CrossRef]

- Ferslew, B.C., et al., Altered Bile Acid Metabolome in Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Dig Dis Sci, 2015. 60(11): p. 3318-28. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-3776-8. [CrossRef]

- Jia, W., G. Xie, and W. Jia, Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018. 15(2): p. 111-128. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.119. [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M., D. Seth, and C.P. Day, Genetic Factors That Affect Risk of Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology, 2016. 150(8): p. 1728-1744.e7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.037. [CrossRef]

- Stender, S. and R. Loomba, PNPLA3 Genotype and Risk of Liver and All-Cause Mortality. Hepatology, 2020. 71(3): p. 777-779. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31113. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, S., et al., Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet, 2008. 40(12): p. 1461-5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.257. [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni, P., et al., Transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 gene variant disentangles nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from cardiovascular disease. Hepatology, 2015. 61(2): p. 506-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27490. [CrossRef]

- Mancina, R.M., et al., The MBOAT7-TMC4 Variant rs641738 Increases Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Individuals of European Descent. Gastroenterology, 2016. 150(5): p. 1219-1230.e6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.032. [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, P.K., et al., The MBOAT7 variant rs641738 alters hepatic phosphatidylinositols and increases severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in humans. J Hepatol, 2016. 65(6): p. 1263-1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.045. [CrossRef]

- Beer, N.L., et al., The P446L variant in GCKR associated with fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels exerts its effect through increased glucokinase activity in liver. Hum Mol Genet, 2009. 18(21): p. 4081-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddp357. [CrossRef]

- Kitamoto, T., et al., Targeted-bisulfite sequence analysis of the methylation of CpG islands in genes encoding PNPLA3, SAMM50, and PARVB of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol, 2015. 63(2): p. 494-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.049. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, C., et al., Non-invasive stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma risk in non-alcoholic fatty liver using polygenic risk scores. J Hepatol, 2021. 74(4): p. 775-782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.024. [CrossRef]

- Gellert-Kristensen, H., et al., Combined Effect of PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and HSD17B13 Variants on Risk of Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the General Population. Hepatology, 2020. 72(3): p. 845-856. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31238. [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.D., et al., Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology, 2011. 140(1): p. 124-31. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.038. [CrossRef]

- Leite, N.C., et al., Prevalence and associated factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Liver Int, 2009. 29(1): p. 113-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01718.x. [CrossRef]

- Sookoian, S. and C.J. Pirola, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is strongly associated with carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol, 2008. 49(4): p. 600-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.012. [CrossRef]

- Targher, G., C.P. Day, and E. Bonora, Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med, 2010. 363(14): p. 1341-50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912063. [CrossRef]

- Targher, G., C.D. Byrne, and H. Tilg, NAFLD and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: clinical associations, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacological implications. Gut, 2020. 69(9): p. 1691-1705. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320622. [CrossRef]

- Deprince, A., J.T. Haas, and B. Staels, Dysregulated lipid metabolism links NAFLD to cardiovascular disease. Mol Metab, 2020. 42: p. 101092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101092. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, N., et al., Liver fibrosis and fatty liver as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2021. 36(10): p. 2960-2966. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15589. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.A., R. Patil, and S.A. Harrison, NAFLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma: The growing challenge. Hepatology, 2023. 77(1): p. 323-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32542. [CrossRef]

- Schuppan, D. and N.H. Afdhal, Liver cirrhosis. Lancet, 2008. 371(9615): p. 838-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [CrossRef]

- Turco, L. and G. Garcia-Tsao, Portal Hypertension. Clinics in Liver Disease, 2019. 23(4): p. 573-587.

- Mendes, F.D., et al., Prevalence and indicators of portal hypertension in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012. 10(9): p. 1028-33.e2.

- Mantovani, A. and A. Dalbeni, Treatments for NAFLD: State of Art. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052350. [CrossRef]

- (EASL), E.A.f.t.S.o.t.L., E.A.f.t.S.o.D. (EASD), and E.A.f.t.S.o.O. (EASO), EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol, 2016. 64(6): p. 1388-402.

- Lange, N.F., P. Radu, and J.F. Dufour, Prevention of NAFLD-associated HCC: Role of lifestyle and chemoprevention. J Hepatol, 2021. 75(5): p. 1217-1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.025. [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L., et al., Diet and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Mediterranean Way. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019. 16(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173011. [CrossRef]

- Anania, C., et al., Mediterranean diet and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol, 2018. 24(19): p. 2083-2094. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i19.2083. [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, S.R., et al., Gut microbiome-targeted therapies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Am J Clin Nutr, 2019. 110(1): p. 139-149.

- Fakhry, T.K., et al., Bariatric surgery improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 2019. 15(3): p. 502-511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2018.12.002. [CrossRef]

- Verrastro, O., et al., Bariatric–metabolic surgery versus lifestyle intervention plus best medical care in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (BRAVES): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. The Lancet, 2023. 401(10390): p. 1786-1797. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00634-7. [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F., et al., An integrated view of anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic targets for the treatment of NASH. Journal of Hepatology, 2023. 79(2): p. 552-566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.038. [CrossRef]

- Ayada, I., et al., Dissecting the multifaceted impact of statin use on fatty liver disease: a multidimensional study. EBioMedicine, 2023. 87: p. 104392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104392. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., et al., Statins on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 RCTs. Medicine (Baltimore), 2023. 102(26): p. e33981. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000033981. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., et al., Statin can reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023. 35(4): p. 353-358. https://doi.org/10.1097/meg.0000000000002517. [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.J., et al., Pioglitazone, Vitamin E, or Placebo for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010. 362(18): p. 1675-1685. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa0907929. [CrossRef]

- Mahady, S.E., et al., The role of thiazolidinediones in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis – A systematic review and meta analysis. Journal of Hepatology, 2011. 55(6): p. 1383-1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.016. [CrossRef]

- Associazione Italiana per lo Studio del Fegato, S.I.d.D., et al., Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults 2021: A clinical practice guideline of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF), the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and the Italian Society of Obesity (SIO). Dig Liver Dis, 2022. 54(2): p. 170-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2021.04.029. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J., et al., Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet, 2016. 387(10019): p. 679-690. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00803-x. [CrossRef]

- Newsome, P.N., et al., A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 2021. 384(12): p. 1113-1124. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2028395. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S., et al., Role of semaglutide in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 2023. 17(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2023.102849. [CrossRef]

- Sumida, Y., et al., Role of vitamin E in the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Free Radic Biol Med, 2021. 177: p. 391-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.10.017. [CrossRef]

- Pacana, T. and A.J. Sanyal, Vitamin E and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2012. 15(6): p. 641-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0b013e328357f747. [CrossRef]

- Bjelakovic, G., et al., Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 2007. 297(8): p. 842-57. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [CrossRef]

- Schurks, M., et al., Effects of vitamin E on stroke subtypes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 2010. 341: p. c5702. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5702. [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.A., et al., Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA, 2011. 306(14): p. 1549-56. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.30.5_suppl.7. [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the, L., D. European Association for the Study of, and O. European Association for the Study of, EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol, 2016. 64(6): p. 1388-402. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443344. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H., R. Vettor, and M. Rossato, Vitamin E as a Treatment for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Reality or Myth? Antioxidants, 2018. 7(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7010012. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M., et al., A phase IIa active-comparator-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of efinopegdutide in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Hepatology, 2023. 79(4): p. 888-897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.05.013. [CrossRef]

- Hartman, M.L., et al., Effects of Novel Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide on Biomarkers of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2020. 43(6): p. 1352-1355. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-1892. [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, M.M. and M.B. Christensen, Emerging glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs, 2021. 26(3): p. 231-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728214.2021.1947240. [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M., et al., Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med, 2022. 387(3): p. 205-216. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2206038. [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P., et al., Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2021. 385(6): p. 503-515. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2107519. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, T., et al., Management of type 2 diabetes with the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia, 2022. 65(8): p. 1251-1261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05715-4. [CrossRef]

-

Intercept announces outcome of FDA advisory committee meeting for obeticholic acid as a treatment for pre-cirrhotic fibrosis due to NASH. May 19, 2023: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2023/05/19/2672820/23024/en/Intercept-Announces-Outcome-of-FDA-Advisory-Committee-Meeting-for-Obeticholic-Acid-as-a-Treatment-for-Pre-Cirrhotic-Fibrosis-due-to-NASH.html.

-

Food and Drug Administration. Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting. Briefing document. May 19, 2023: https://www.fda.gov/media/168215/download.

- Rinella, M.E., et al., Non-invasive evaluation of response to obeticholic acid in patients with NASH: Results from the REGENERATE study. J Hepatol, 2022. 76(3): p. 536-548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.10.029. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, E., et al., Antifibrotic Effects of the Dual CCR2/CCR5 Antagonist Cenicriviroc in Animal Models of Liver and Kidney Fibrosis. PLoS One, 2016. 11(6): p. e0158156. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158156. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L., et al., A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cenicriviroc for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with fibrosis. Hepatology, 2018. 67(5): p. 1754-1767. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29477. [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M., et al., Cenicriviroc Lacked Efficacy to Treat Liver Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: AURORA Phase III Randomized Study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.003. [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V. and S.L. Friedman, Why Do So Many Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Trials Fail? Gastroenterology, 2023. 165(1): p. 5-10.

- Baumeister, S.E., et al., Association between physical activity and risk of hepatobiliary cancers: A multinational cohort study. J Hepatol, 2019. 70(5): p. 885-892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., H. Wang, and H. Xiao, Metformin Actions on the Liver: Protection Mechanisms Emerging in Hepatocytes and Immune Cells against NASH-Related HCC. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22095016. [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.C., et al., Sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist, 2009. 14(1): p. 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0185. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M., et al., Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet, 2018. 391(10126): p. 1163-1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30207-1. [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S., et al., Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382(20): p. 1894-1905. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1915745. [CrossRef]

- Casak, S.J., et al., FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2021. 27(7): p. 1836-1841. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-3407. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Tsao, G., et al., Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol, 2007. 102(9): p. 2086-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01481.x. [CrossRef]

- Biecker, E., Diagnosis and therapy of ascites in liver cirrhosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2011. 17(10). https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1237. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D., et al., Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut, 2020. 69(7): p. 1173-1192. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320221. [CrossRef]

- easloffice@easloffice.eu, E.A.f.t.S.o.t.L.E.a. and E.A.f.t.S.o.t. Liver, EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol, 2018. 69(1): p. 182-236.

- Song, D.S. and S.H. Bae, Changes of guidelines diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma during the last ten-year period. Clin Mol Hepatol, 2012. 18(3): p. 258-67. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2012.18.3.258. [CrossRef]

- Salaheldin, M., et al., Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Next Threat after Viral Hepatitis. Diagnostics, 2023. 13(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13162631. [CrossRef]

- Taru, M.-G. and M. Lupsor-Platon, Exploring Opportunities to Enhance the Screening and Surveillance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) through Risk Stratification Algorithms Incorporating Ultrasound Elastography. Cancers, 2023. 15(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164097. [CrossRef]

- Reig, M., et al., BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol, 2022. 76(3): p. 681-693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E., et al., Efficacy of immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Does liver disease etiology have a role? Digestive and Liver Disease, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2023.08.062. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).