1. Evolution of TRNA

A number of models have been advanced to describe tRNA evolution. We have advanced the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem [

1,

2,

3]. To support minihelix replication in pre-life, 3 31 nt minihelices were joined by ligation. The D loop 31 nt minihelix had the sequence GCGGCGG_UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA_CCGCCGC (the _ separates distinct sequence features). The D loop minihelix is a 7 nt GCG repeat (5’-acceptor stem) linked to a 17 nt UAGCC repeat (D loop minihelix core) linked to a 7 nt CGC repeat (3’-acceptor stem). The anticodon loop and the T loop 31 nt minihelices were probably initially identical, with the sequence GCGGCGG_CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG_CCGCCGC (/ indicates a U-turn; ? indicates A, G, C or U (the pre-life base remains unknown)). This is a 7 nt GCG repeat (5’-acceptor stem) linked to a 17 nt stem-loop-stem (CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG) linked to a 7 nt CGC repeat (3’-acceptor stem). The only pre-life sequence ambiguities are in the 7 nt CU/???AA loops, not in the stems. After LUCA (the last universal common (cellular) ancestor), the dominant anticodon loop sequence was CU/BNNAA or CU/BNNGA (B indicates G, C or U, not A; N indicates A, G, C or U), and the dominant T loop sequence was UU/CAAAU. 7 nt loop sequences for the anticodon loop and the T loop were separately selected in evolution because of their different placements within tRNA. The anticodon loops were selected to generate the distinct anticodons required for coding. The T loop sequence was selected to form the tRNA elbow at which the D loop and the T loop interact to form the L-shaped tRNA molecule [

4]. T loop C3 (tRNA-56) forms a bent Watson-Crick pair to a D loop G (G19 in standard tRNA numbering; for historical reasons, standard tRNA numbering breaks down in the D loop and V loop). D loop G18 intercalates between T loop A4 (tRNA-57) and A5 (tRNA-58), lifting T loop A6 (tRNA-59) and U7 (tRNA-60) out of the loop. G18 was initially an A, as part of the third UAGCC repeat, but was mutated to G to support D loop-T loop interactions at the elbow (see

Figure 6 below). This G to A transition in the D loop is one of very few systematic sequence changes to support the tRNA fold versus the parental 31 nt minihelix folds. In summary, tRNA evolved in pre-life from ligation of 3 31 nt minihelices followed by internal RNA processing (described below). The 31 nt minihelices that were utilized were of 2 distinct sequences (D loop and anticodon/T loop). Pre-life tRNA sequences were comprised of RNA repeats and inverted repeats. Post-LUCA, the dominant tRNA anticodon and T loop sequences are known because these sequences have been conserved for ~4 billion years in living organisms. Post-LUCA tRNA sequences can be recovered as typical tRNA sequences from a tRNA database [

5]. The 3 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem, therefore, can readily be confirmed from typical tRNA diagrams of ancient Archaea (i.e., Pyrococcus furiosis, Sulfolobus solfataricus, Aeropyrum pernix, Staphylothermus marinus).

Alternate models for tRNA evolution are of the following types: 1) convergent models [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]; 2) accretion models [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]; 3) 2 minihelix models [

6,

11,

12,

14,

16,

17]; and 4) highly theoretical models [

7,

8,

10,

19,

20]. First of all, no convergent model can rationally apply to tRNA evolution. To evolve tRNA, by contrast, requires a divergent evolution model, in which tRNAomes (all of the tRNAs of an organism) diverged from pre-life type I and type II tRNAs by repeated duplications and re-purposing events. In a convergent model, multiple small tRNA fragments must converge on the same homologous sequence, conformation and form. For tRNA, such a convergent evolution model is untenable, and all convergent models are accretion models, because bases must be added and/or subtracted to gain the final tRNA form. Because pre-life tRNAs were generated from completely ordered sequences (RNA repeats and inverted repeats), no accretion or convergent model can be descriptive [

2,

3,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Accretion models have reasonably been applied to describe later stages of rRNA evolution [

26,

27,

28]. For tRNA, by contrast to rRNA, accretion models are convergent models that demand convergence of multiple pre-tRNAs (tRNA fragments) to similarly structured and ordered RNA sequences. For initial tRNA evolution, no accretion model is reasonable.

Multiple 2 minihelix models have been advanced for tRNA evolution. All of these models are convergent and accretion models. One disqualifying objection is that 2 minihelix models are inconsistent with homology of the anticodon stem-loop-stem and the T stem-loop-stem [

3]. Because the 17 nt anticodon and the 17 nt T stem-loop-stems are clearly homologous (i.e., by inspection), no 2 minihelix model can possibly be correct. In a 2 minihelix model, the anticodon and T stem-loop-stems would be required to converge on a homologous conformation (i.e., compact 7 nt U-turn loop) and homologous sequence. The uroboros (hoop snake with mouth grasping tail) model for tRNA evolution was computer-generated and remains highly theoretical [

9,

10]. In the uroborous vision, numerous 22 nt covalently closed tRNA rings converged and accreted to homologous and ordered tRNA forms. The uroboros model cannot be correct for tRNA evolution. Some authors employ convergent and accretion tRNA evolution models without realizing their obvious mistake [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

2. The evolutionary history of life on Earth

Top-down strategies to describe pre-life evolution have the potential advantage of identifying dominant successful pathways because only routes that survived can be detected [

1,

2]. The 3 31 nt minihelix theorem relates a top-down, sequence-based argument for two stages of pre-life evolution: 1) polymer world; and 2) 31 nt minihelix world. The central focus of the top-down argument is that highly ordered tRNA sequences have been conserved from pre-life to life and maintained since LUCA. Bottom-up strategies would be attempts to create life or a potential pre-life chemical state in vitro [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Bottom-up strategies result in novel chemistry but may represent evolutionary dead-ends. When top-down and bottom-up descriptions can be linked, understanding of the pre-life to life transition is significantly enriched. The 3 31 nt tRNA evolution theorem probably describes hundreds of millions of years of pre-life.

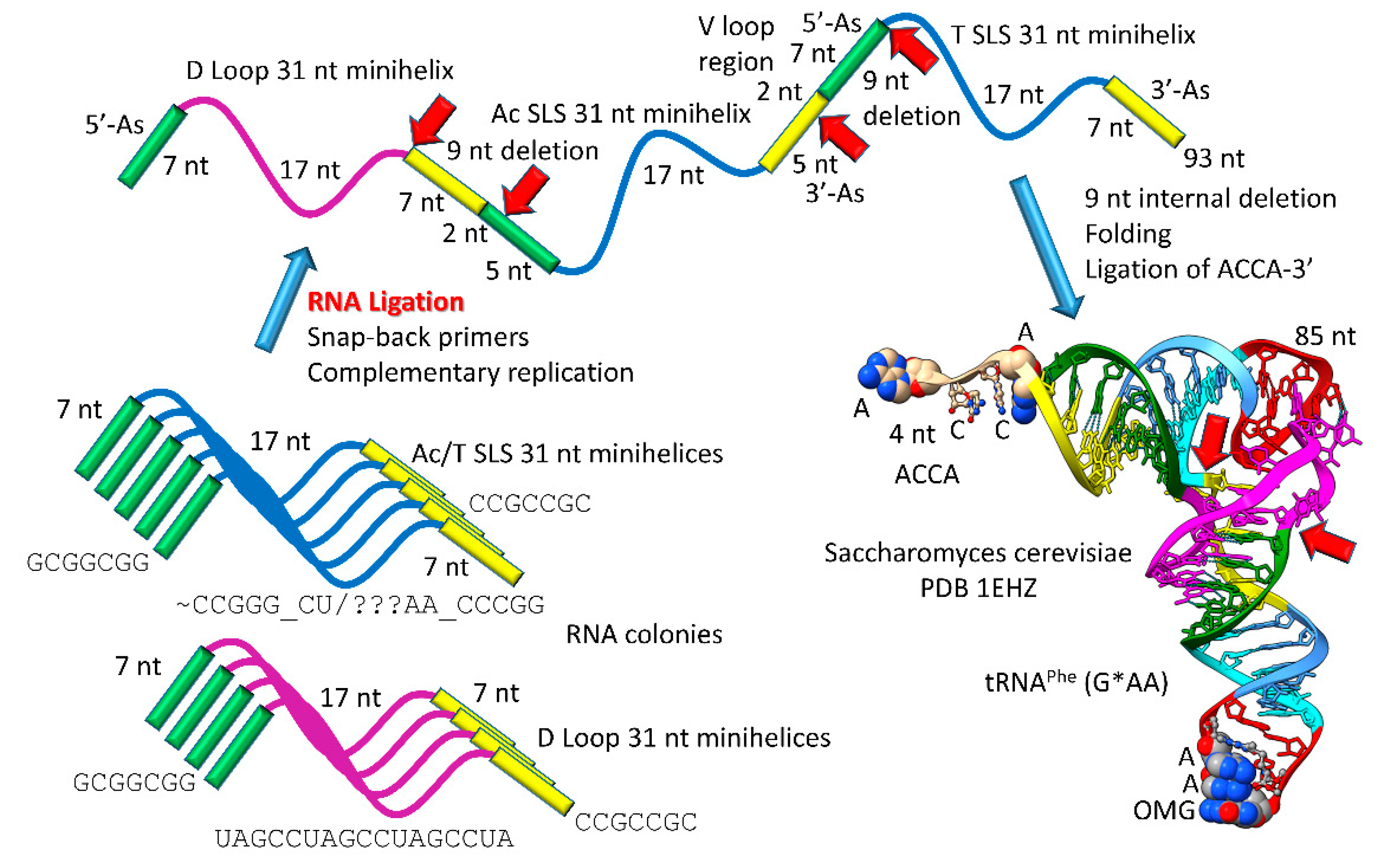

The history for evolution of life on Earth embedded in tRNA sequence is shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Remarkably, tRNA evolution reduces to a simple sequence puzzle that anyone who can read a 4 letter code can solve or verify.

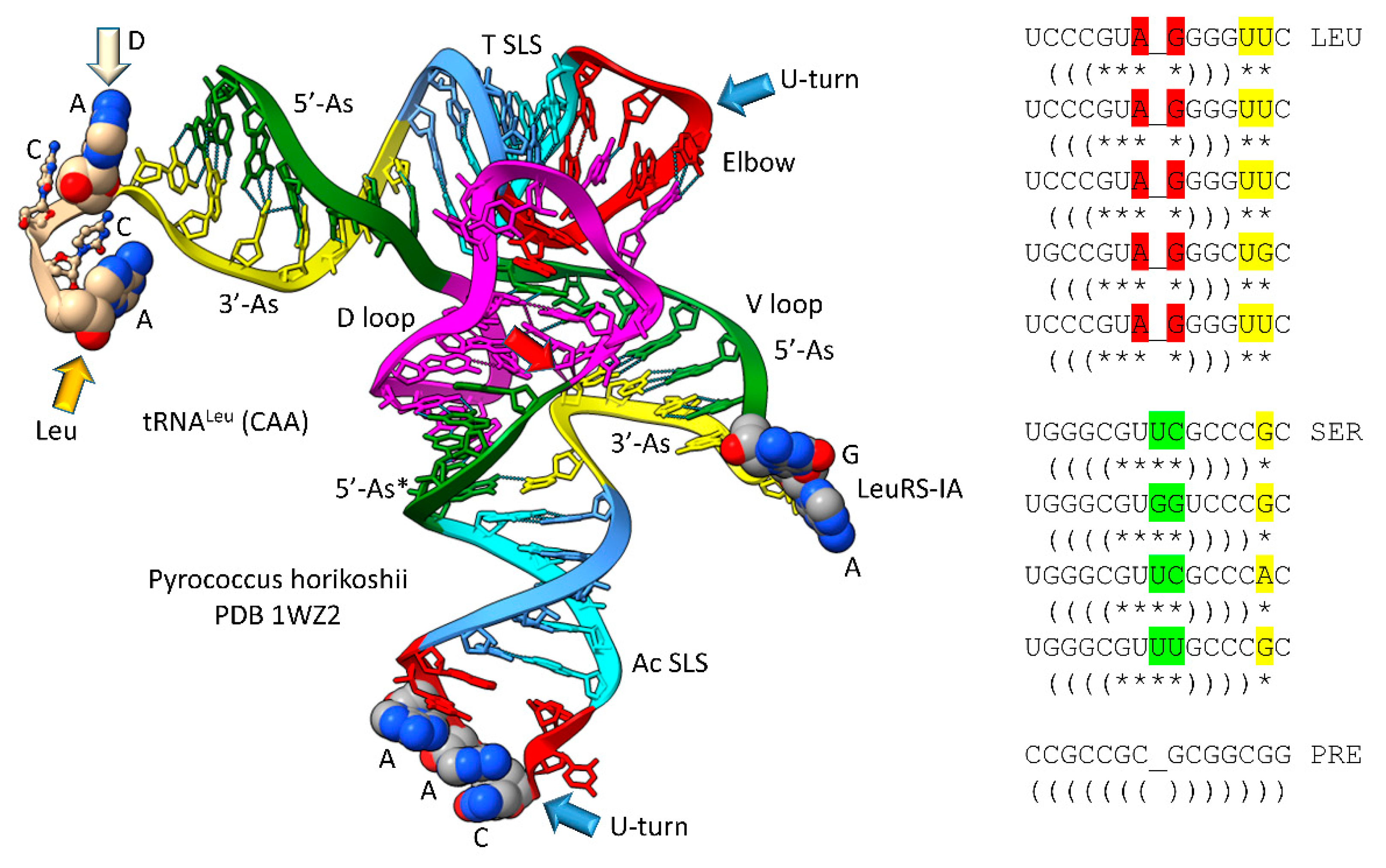

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 explain type II tRNA evolution [

39].

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 explain type I tRNA evolution, which is a very similar process [

3,

21,

23,

24,

25]. Both type II and type I tRNAs evolved from the same 93 nt tRNA precursor. Type II tRNA evolution converted the 93 nt precursor, which was formed by ligation of 3 31 nt minihelices with two distinct 17 nt core sequences, into type II tRNA through a single internal 9 nt deletion (

Figure 1). Generation of a pre-life type II tRNA required only a single internal 9 nt deletion within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems, as shown (red arrows). In

Figure 1, 7 nt of a 3’-acceptor stem (yellow) and 2 nt of a 5’-acceptor stem (green) were deleted, leaving a 5 nt fragment of a 5’-acceptor stem (GGCGG; green). The internal deletion fused a magenta segment (a 17 nt UAGCC repeat) to a green segment (a 5’-acceptor stem fragment; 5 nt).

Figure 1.

Type II tRNA evolved via RNA ligation and a 9 nt internal deletion within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems [

39]. 3 31 nt minihelices (one D loop minihelix (magenta 17 nt core) and two anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelices (blue 17 nt core)) were fused by ligation, for minihelix replication. The 93 nt tRNA precursor was processed by an internal 9 nt deletion (see below) within fused 3’-acceptor (yellow) and 5’-acceptor (green) stems. In the type II tRNA structure, the red arrow indicates fusion of the magenta segment (17 nt D loop minihelix core; UAGCC repeat) and the green segment (5’-acceptor stem fragment; initially GGCGG). Abbreviations: SLS) stem-loop-stem; Ac) anticodon.

Figure 1.

Type II tRNA evolved via RNA ligation and a 9 nt internal deletion within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems [

39]. 3 31 nt minihelices (one D loop minihelix (magenta 17 nt core) and two anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelices (blue 17 nt core)) were fused by ligation, for minihelix replication. The 93 nt tRNA precursor was processed by an internal 9 nt deletion (see below) within fused 3’-acceptor (yellow) and 5’-acceptor (green) stems. In the type II tRNA structure, the red arrow indicates fusion of the magenta segment (17 nt D loop minihelix core; UAGCC repeat) and the green segment (5’-acceptor stem fragment; initially GGCGG). Abbreviations: SLS) stem-loop-stem; Ac) anticodon.

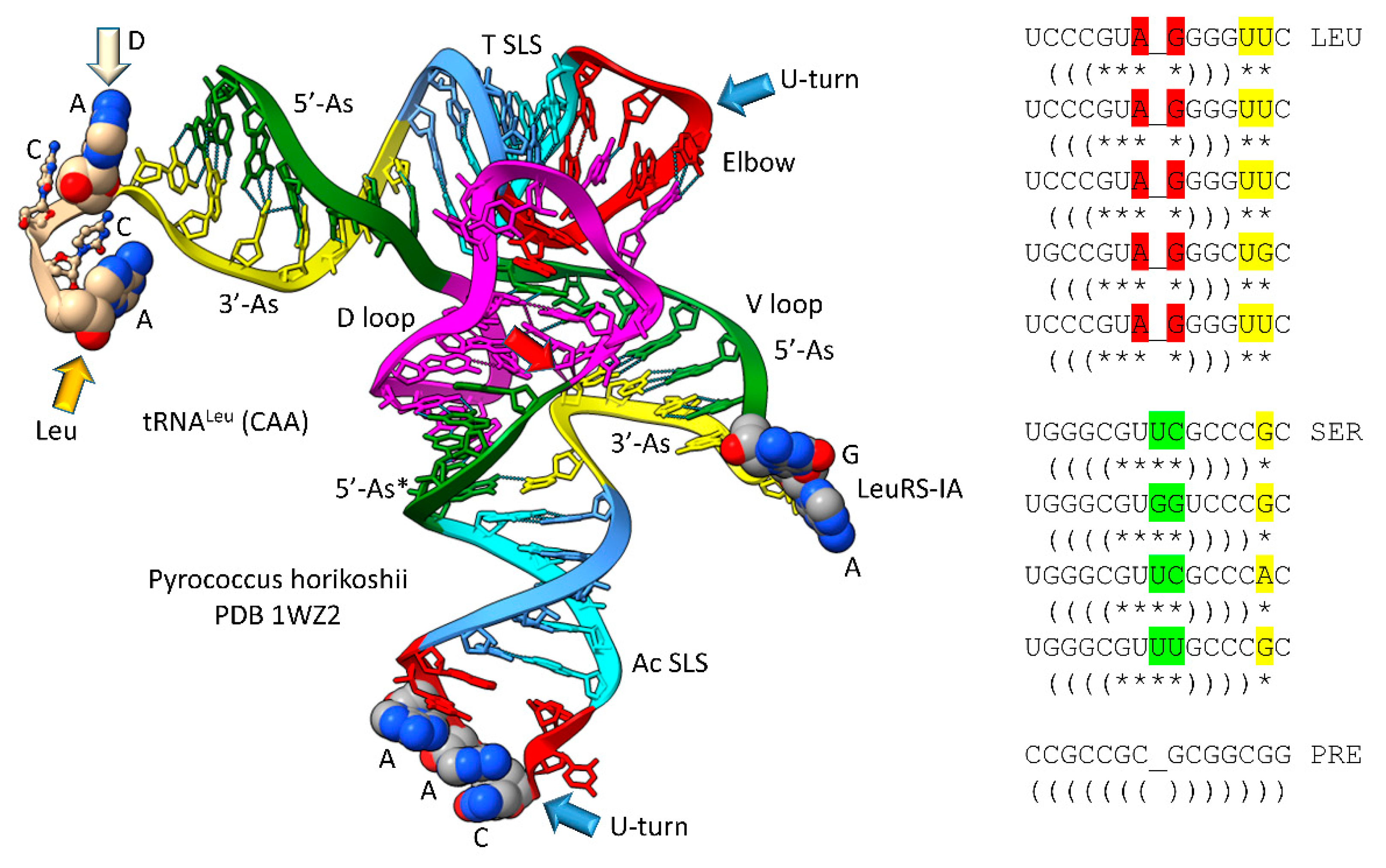

Figure 2.

Type II tRNA resulted from failure to process a 14 nt V loop (initially a 7 nt 3’-acceptor stem ligated to a 7 nt 5’-acceptor stem) rather than by accretion. Colors: green) 5’-acceptor stem and 5’-acceptor stem fragment; magenta) 17 nt D loop core; cyan) 5’-anticodon and T stem; red) anticodon and T loops; cornflower blue) 3’-anticodon and T stem; and yellow) 3’-acceptor stem. Arrow colors: blue) U-turns; red) processing site in evolution; light yellow) discriminator base (D); and gold) site of amino acid placement. The structure is of an unmodified Pyrococcus horikoshii tRNA

Leu in complex with LeuRS-IA (not shown in the image). At the right of the figure are tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser V loops from Pyrococcus furiosis, an ancient Archaeon. Colors: red) V loop AG that binds LeuRS-IA in tRNA

Leu recognition in P. furiosis [

40]; yellow) unpaired bases just 5’ of the Levitt base; and green) tRNA

Ser bases at the 3’-end of the V loop. PRE indicates an initial pre-life sequence. Parentheses indicate stems; * indicates unpaired bases.

Figure 2.

Type II tRNA resulted from failure to process a 14 nt V loop (initially a 7 nt 3’-acceptor stem ligated to a 7 nt 5’-acceptor stem) rather than by accretion. Colors: green) 5’-acceptor stem and 5’-acceptor stem fragment; magenta) 17 nt D loop core; cyan) 5’-anticodon and T stem; red) anticodon and T loops; cornflower blue) 3’-anticodon and T stem; and yellow) 3’-acceptor stem. Arrow colors: blue) U-turns; red) processing site in evolution; light yellow) discriminator base (D); and gold) site of amino acid placement. The structure is of an unmodified Pyrococcus horikoshii tRNA

Leu in complex with LeuRS-IA (not shown in the image). At the right of the figure are tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser V loops from Pyrococcus furiosis, an ancient Archaeon. Colors: red) V loop AG that binds LeuRS-IA in tRNA

Leu recognition in P. furiosis [

40]; yellow) unpaired bases just 5’ of the Levitt base; and green) tRNA

Ser bases at the 3’-end of the V loop. PRE indicates an initial pre-life sequence. Parentheses indicate stems; * indicates unpaired bases.

The original pre-life type II tRNA V loop (V for variable) was a 7 nt 3’-acceptor stem (yellow) ligated to a 7 nt 5’-acceptor stem (green) (initially, CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG) [

39]. Because the pre-life V loop sequence was self-complementary along its entire length, the V stem-loop-stem evolved to sequences such as those found in archaeal tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser. V loops for tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser from Pyrococcus furiosis were selected to be distinct (i.e., for separate discrimination by LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA) and are shown in the right panel of

Figure 2, compared to the initial pre-life V loop [

5]. V loops for tRNA

Leu are numbered V1 to V14 (14 nt was the primordial length). V1U forms a wobble pair with G26 (standard tRNA numbering). V14C forms a reverse Watson-Crick pair to G15 (the Levitt base pair; see below). Two unpaired bases are found at V12 and V13 (UU or UG). The number of unpaired bases just 5’ to the Levitt base pair determines the trajectory of the V stem-loop-stem from the tRNA body. V7-AG-V8 binds the tRNA

Leu charging enzyme LeuRS-IA (leucine aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase; structural class and subclass IA) [

40]. None of the corresponding tRNA

Ser V loop sequences are sufficiently similar to AG (UC, GG, UU; green shading), so LeuRS-IA will not bind to a tRNA

Ser V loop, even if the loop could be accessed by LeuRS-IA. For P. furiosis, the length of the tRNA

Ser V loop expanded from 14 to 15 nt. In tRNA

Ser, only 1 nt is unpaired just 5’ of the Levitt base pair. The tRNA

Ser V stem-loop-stem, therefore, has a different trajectory from the tRNA

Ser body compared to tRNA

Leu. SerRS-IIA binds the V stem [

41], not the V loop, so SerRS-IIA is dependent on the trajectory of the V stem-loop-stem from the tRNA

Ser body compared to the distinct trajectory of the V stem-loop-stem of tRNA

Leu. In summary, type II tRNA evolution is described to the last nucleotide by the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem. The longer V loop in type II tRNAs was initially generated by a failure to process ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems, rather than by insertion of bases (accretion) (see also:

https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202209.0189/v1 ).

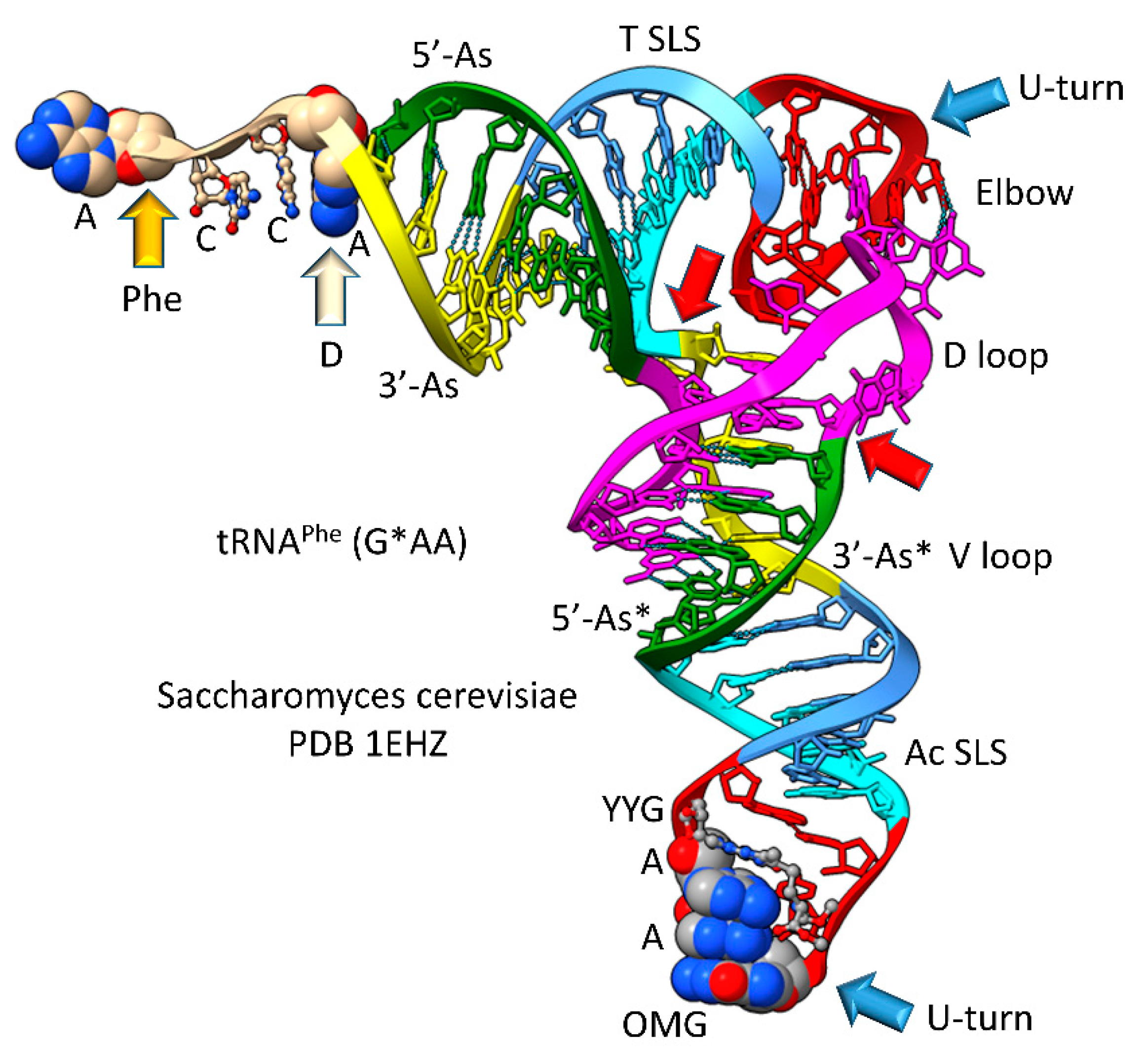

Most tRNAs are type I, with a shorter V loop (i.e., 5 nt) compared to type II tRNAs (initially 14 nt). Notably, the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem describes type I tRNA evolution to the last nucleotide (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In

Figure 3, type I tRNA evolution is shown from the same 93 nt tRNA precursor. In this case, two closely related 9 nt deletions occurred within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems. The more 5’ internal 9 nt deletion was identical to the processing event that generated type II tRNAs (

Figure 1). The more 3’ 9 nt deletion removed 7 nt of the 5’-acceptor stem (green) and 2 nt of the 3’-acceptor stem (yellow) leaving 5 nt of the 3’-acceptor stem (initially CCGCC; yellow). Thus, in type I tRNA evolution, CCGCC (yellow) was linked to CCGGG (cyan). In type I tRNA, the more 5’ and 3’ 9 nt deletions within ligated acceptor stems are closely related. If the deletions occurred on complementary RNA strands, the more 3’ 9 nt deletion was identical to the more 5’ 9 nt deletion. Below, we suggest a ribozyme/primitive catalyst processing mechanism to describe the internal 9 nt deletions. In summary, type II and type I tRNAs were evolved by a common mechanism that involved ligation of the same 3 31 nt minihelices to form the same 93 nt tRNA precursor and then internal processing and deletion of complementary 9 nt segments. It is likely that the first tRNAs were mixtures of type II and type I tRNAs.

Figure 3.

Evolution of type I tRNA via RNA ligation and two related, internal 9 nt deletions. Colors and arrow colors are as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. G* (OMG) is 2’-O-methyl-G. 9 nt internal deletions generate a magenta-green fusion and a yellow-cyan fusion (red arrows).

Figure 3.

Evolution of type I tRNA via RNA ligation and two related, internal 9 nt deletions. Colors and arrow colors are as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. G* (OMG) is 2’-O-methyl-G. 9 nt internal deletions generate a magenta-green fusion and a yellow-cyan fusion (red arrows).

Figure 4.

Type I tRNA. Colors and arrow colors are as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. G* (OMG) is 2’-O-methyl-G. YYG is Wy-butosine [

42]. The V loop (3’-As*; yellow) is fused to the cyan (5’-T stem), in slight contrast to type II tRNA processing (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Type I tRNA. Colors and arrow colors are as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. G* (OMG) is 2’-O-methyl-G. YYG is Wy-butosine [

42]. The V loop (3’-As*; yellow) is fused to the cyan (5’-T stem), in slight contrast to type II tRNA processing (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

3. The 3 31 nt minihelix theorem and evolution of the genetic code

The 3 31 nt minihelix theorem is shown in

Figure 5, as linear sequence. The inset in the figure shows a mechanism to generate the 5’- (type I and type II tRNAs) and 3’- (type I tRNA only) acceptor stem fragments found in tRNAs. The proposed mechanism involved a ribozyme/primitive catalyst endonuclease to cleave RNAs at stem-loop boundaries followed by RNA ligation. RNA stem-loop-stems cannot maintain a 2 nt loop, because a 2 nt loop is too constrained, so 4 nt loops were the expected substrates for processing (as shown).

Figure 5.

3 31 nt minihelix theorem. Evolution of tRNA world from polymer world and 31 nt minihelix world. The inset describes the 9 nt deletions to generate tRNAs: the more 5’ processing event involves deletion between the blue arrows; the more 3’ processing event (type I tRNA only) involves deletion between the red arrows. Internal deletions were at stem-loop junctions. Colors and arrows are consistent with previous figures. Yellow arrows indicate the cornflower blue-yellow junction, indicating the degree of order in tRNA assembly.

Figure 5.

3 31 nt minihelix theorem. Evolution of tRNA world from polymer world and 31 nt minihelix world. The inset describes the 9 nt deletions to generate tRNAs: the more 5’ processing event involves deletion between the blue arrows; the more 3’ processing event (type I tRNA only) involves deletion between the red arrows. Internal deletions were at stem-loop junctions. Colors and arrows are consistent with previous figures. Yellow arrows indicate the cornflower blue-yellow junction, indicating the degree of order in tRNA assembly.

Embedded in tRNA sequences is evidence for minihelix world and, before that, polymer world [

1,

2,

21]. Surprisingly, precursor tRNA sequences from pre-life were highly ordered: RNA repeats and inverted repeats [

3,

24,

25,

39]. Initially, this was a shock to us because we thought tRNA was generated by a chaotic process. Inspection of tRNA sequences, however, shows that pre-life tRNA precursors were ordered. Because tRNAs were generated from ordered sequences, pre-life tRNA precursors were arranged as RNA repeats and inverted repeats, as shown. Analysis of tRNA sequences, therefore, reveals a history of pre-life worlds on Earth. It is not reasonable to consider that ordered tRNA precursors were generated by any chaotic process. We stress that these recovered sequences from living organisms are fossils from the pre-life to life transition on Earth ~4 billion years ago.

In pre-life, polymer world, minihelix world and tRNA world were overlapping and more complex than can now be described just from tRNA sequence. The surviving history was limited to that which was conserved in tRNA sequence. This is a limitation of top-down and sequence-based analyses of pre-life. Polymer world included GCG repeats, CGC repeats and UAGCC repeats, which are sequences found in tRNAs. We posit that polymer world included ACCA, as the most primitive RNA-amino acid adapter. Attaching glycine at the 3’-end, ACCA becomes ACCA-Gly, which can be used for polyglycine synthesis. A GCG repeat includes multiple CGGC sequences, which can anneal with ACCA-Gly for polyglycine synthesis. Hydration-dehydration cycles may have supported polyglycine synthesis with multiple ACCA-Gly immobilized in proximity [

38,

43]. In pre-life, the stem-loop-stem sequence CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG indicates that some form of complementary replication was present in polymer world. Also, the anticodon stem-loop-stem derived from this sequence is the most central intellectual property in pre-life on Earth. The 7 nt loop sequence (CU/???AA) allowed tRNA to learn to code.

Minihelix world evolved and was selected alongside polymer world as an improved means to generate polyglycine [

37,

44]. Judging from tRNA sequence, minihelix world was the clear precursor of tRNA world, because tRNA was evolved by ligation of 3 31 nt minihelices of almost completely known sequence (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). To generate minihelix world from polymer world required a small number of ribozymes/primitive catalysts most or all of which have been generated by scientists in vitro. Similarly, a small set of ribozymes/primitive catalysts would be sufficient to convert minihelix world into tRNA world. Most likely, these conversions could be reproduced in vitro.

Organisms have lived in tRNA world for about 4 billion years. The advantage of tRNA world over polymer and minihelix world was, initially, that tRNA evolved and was selected as an improved means to synthesize polyglycine as a component of protocells [

1,

2]. From tRNA-polyglycine world, tRNA-GADV world emerged [

36,

45,

46,

47,

48]. From an 8 amino acid stage (i.e., GADVLSER), the genetic code and sequence-dependent proteins emerged [

1,

2,

21]. Thus, no chicken and egg problem need be invoked in evolution of the genetic code, because the system need not have had foresight that it would eventually encode sequence-dependent proteins. Polyglycine and GADV polypeptides were selected for coacervate functions (i.e., supporting membraneless organelles in protocells) [

1,

2,

49]. With added complexity, the genetic code and sequence-dependent proteins evolved and were selected and coevolved with tRNAomes [

21,

23]. Once the genetic code evolved, living systems began.

4. Arguments for and against the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem

For reasons that we do not understand, the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem has not gained universal acceptance. The 3 31 nt minihelix theorem is important because it relates the history of the pre-life to life transition on Earth. We understand that there are competing tRNA evolution models, but alternate models are falsified. The competing models are all chaotic, convergent, accretion and 2 minihelix models. None of these models can possibly be reasonable.

Statistics strongly favor the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem (

Table 1) [

24]. Remarkably, every feature of the theorem was predicted and is supported by statistical analysis. As the analysis was done, a p-value of 0.001 indicates a similar sequence with a 1 in 1000 chance of being due to random chance. So a p-value of 0.001 indicates homology. A p-value approaching 1 indicates sequences are not homologous. A p-value of <0.05 would indicate similarity and probable homology. First of all, as expected, the 5’-acceptor stem is apparently homologous to the complement of the 3’-acceptor stem with which it pairs. Also, as expected, the 3’-acceptor stem is homologous to the complement of the 5’-acceptor stem. The demonstrated complementarity of the 5’- and 3’-acceptor stems appears to partly verify the statistical test. The 5’-acceptor stem fragment tests as homologous to the 5’-acceptor stem, positions 3-7. The 3’-acceptor stem fragment (type I V loop) tests as homologous to the 3’-acceptor stem, positions 66-70, as expected from the theorem. The anticodon stem-loop-stem tests as homologous to the T stem-loop-stem, as anticipated from the theorem. As expected, neither the 17 nt anticodon stem-loop-stem nor the 17 nt T stem-loop-stem test as homologous to the 17 nt D loop core (initially, a UAGCC repeat). Both the type II tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser V loops test as homologous to a 3’-acceptor stem ligated to a 5’-acceptor stem [

39]. In summary, every aspect and prediction of the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem is reinforced by statistical tests. The theorem completely describes evolution of type II and type I tRNAs to the last nucleotide.

Table 1.

Internal homologies within archaeal tRNAs. C indicates a sequence complement. In type II V loops, n indicates the total length of the V loop. In type II tRNAs, V1 was selected to be U to form a G26~UV1 wobble pair. Vn was selected to be C to form the G15-CVn Levitt base pair. Similar statistics were obtained for Bacterial tRNAs [

24,

39].

Table 1.

Internal homologies within archaeal tRNAs. C indicates a sequence complement. In type II V loops, n indicates the total length of the V loop. In type II tRNAs, V1 was selected to be U to form a G26~UV1 wobble pair. Vn was selected to be C to form the G15-CVn Levitt base pair. Similar statistics were obtained for Bacterial tRNAs [

24,

39].

| Sequence #1 |

Sequence #2 |

length (nt) |

p-value |

| 5'-As |

3'-As-C |

7 |

0.001 |

| 3'-As |

5'-As-C |

7 |

0.001 |

| 5'-As* |

5'-As (3-7) |

5 |

0.001 |

| 3'-As* (V loop) |

3'-As (66-70) |

5 |

0.001 |

| Ac SLS |

T SLS |

17 |

0.001 |

| D loop |

Ac loop |

17 |

0.979 |

| D loop |

T loop |

17 |

~1 |

| 3'-As+5'-As (66-71+2-7) |

V-loop Leu V2-V7+Vn-7-Vn-1

|

12 |

0.001 |

| 3'-As+5'-As (66-71+2-7) |

V-loop Ser V2-V7+Vn-7-Vn-1

|

12 |

0.001 |

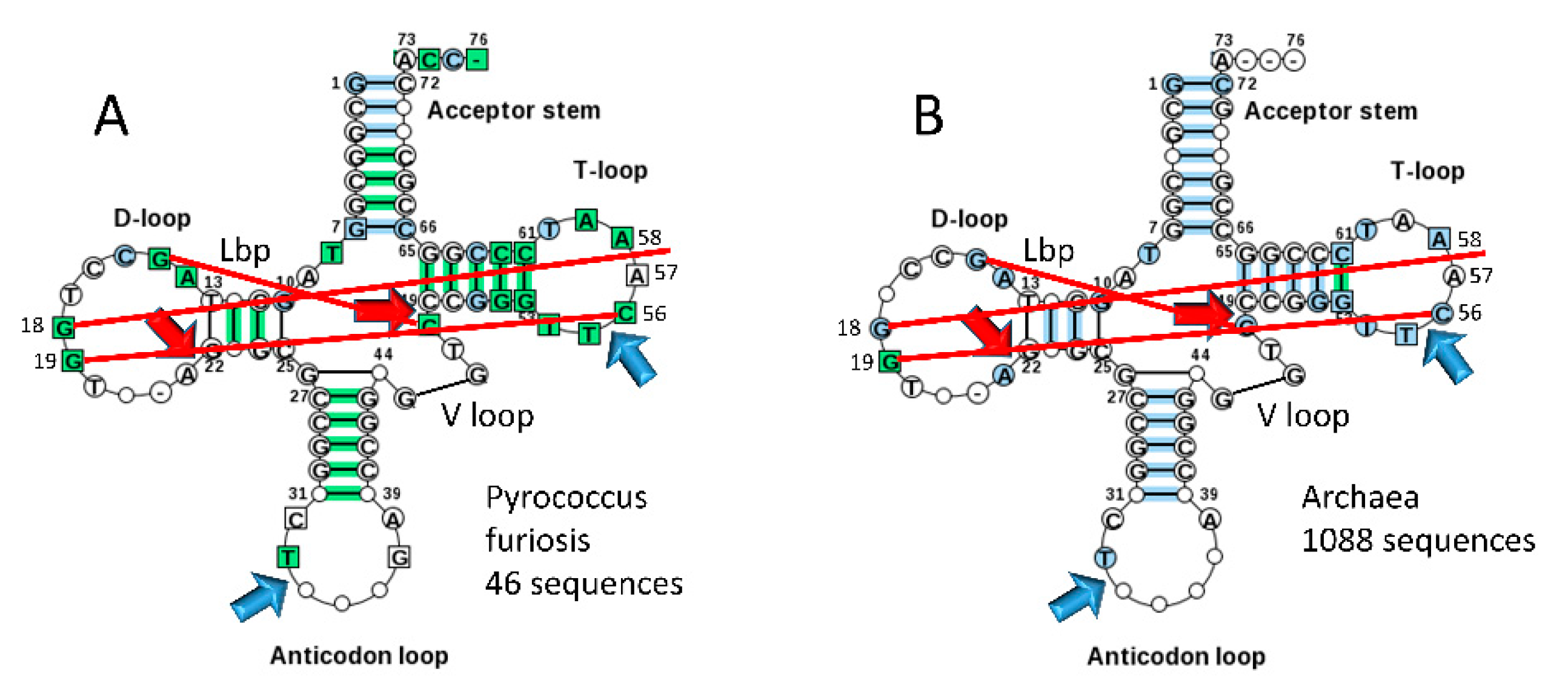

Typical tDNA sequences from the tRNA database are shown in

Figure 6 for Pyrococcus furiosis (A) and a large collection of Archaea (B) [

5]. The greener image in

Figure 6A indicates a stronger consensus, indicating that some Archaea are more derived from LUCA compared to P. furiosis. We consider the ancient Archaeon P. furiosis as a reasonable model organism for LUCA. Strangely, Di Giulio has argued that the 17 nt anticodon and 17 nt T stem-loop-stems, each with a compact 7 nt U-turn loop, with the U-turn positioned between loop positions 2 and 3, are not homologs [

11]. Di Giulio’s assertion is not credible. The anticodon stem-loop-stem and the T stem-loop-stem are homologous by inspection and by statistical test (

Figure 6;

Table 1). According to Di Giulio’s tRNA evolution model, the 17 nt anticodon stem-loop-stem and the 17 nt T stem-loop-stem must take on apparent homologous sequence and common structures by convergent evolution [

12,

14,

50].

One might argue that acceptor stems are not based on a GCG (5’-acceptor stem) and complementary CGC (3’-acceptor stem) repeat, although inspection and statistical analyses support the sequence repeats [

24]. The typical P. furiosis tRNA sequence gives the 5’-acceptor stem sequence as GCGGCGG (a perfect GCG repeat) and the 3’-acceptor stem sequence as CCGCNNC (G pairs with both C and U) (

Figure 6A). For a larger collection of Archaea in the tRNA database, the typical 5’-acceptor stem sequence is GCNGCGG and the typical 3’-acceptor stem sequence is CCGNNGC (

Figure 6B). Acceptor stems diverge from a perfect GCG repeat for distinct recognition by cognate AARS enzymes. In P. furiosis, the tRNA

Ser D loop core begins with two perfect UAGCC repeats UAGCCUAGCC (not shown). A tRNA

Gly 17 nt D loop core sequence is UAGUCUAGCCUGGUCUA, which is a very close match to a UAGCC repeat [

5]. The P. furiosis tRNA

Gly sequence is the closest to tRNA

Pri (the pre-life, primordial tRNA sequence;

Figure 5). Closest homology of tRNA

Pri and tRNA

Gly is consistent with life evolving from a tRNA-polyglycine world [

23]. Because acceptor stems and their fragments in tRNA evolved from GCG and CGC repeats and the 17 nt D loop core evolved from a UAGCC repeat, the pre-life world generated RNA repeats, and, at least in some cases, their complement (GCG and CGC repeats are complementary). Anticodon and T stem-loop-stems are snap-back primers and self-complementary at the stems. One might try to argue that the RNA repeats and homologous inverted repeats conserved in tRNAs for ~4 billion years were all caused by convergent evolution, but such an argument would be untenable. For the highly skeptical, at the very least, the 3 31 nt minihelix theorem is a remarkably good model for tRNA evolution from ~4 billion years ago. Our position is that tRNA sequences embed an unambiguous history of the most central process in the pre-life to life transition on Earth.

Figure 6.

Typical tDNA diagrams for Pyrococcus furiosis (A) and Archaea (B) [

5]. Arrow colors: red) processing positions for evolution of type I tRNAs; and blue) U-turns. Red lines indicate: 1) the Levitt reverse Watson-Crick base pair (G15-CV5) (Lbp for Levitt base pair); 2) intercalation of G18 between A57 and A58 (“elbow” contact); and 3) Watson-Crick interaction of G19 and C56 (“elbow” contact) [

4].

Figure 6.

Typical tDNA diagrams for Pyrococcus furiosis (A) and Archaea (B) [

5]. Arrow colors: red) processing positions for evolution of type I tRNAs; and blue) U-turns. Red lines indicate: 1) the Levitt reverse Watson-Crick base pair (G15-CV5) (Lbp for Levitt base pair); 2) intercalation of G18 between A57 and A58 (“elbow” contact); and 3) Watson-Crick interaction of G19 and C56 (“elbow” contact) [

4].

5. Evolution of the genetic code

An appreciation of tRNA evolution appears to demand an anticodon-centric view of genetic code evolution [

1,

2,

21]. We posit that the genetic code evolved around the tRNA anticodon according to how the anticodon was read on the coevolving ribosome. Wobbling at tRNA-34 evolved as the ribosome “learned” to read the anticodon. We posit that tRNA-34 and tRNA-36 were originally both wobble positions, but that, as the code and ribosome coevolved, wobbling was suppressed at tRNA-36 by modifications at tRNA-37 and by closing of the ribosome 16S rRNA in order to tighten recognition of the tRNA-mRNA anticodon-codon interaction [

51,

52,

53]. A comprehensive model for genetic code evolution has been published in which the placements of all amino acids in the code are rationalized [

1,

2,

21]. Consistent with a polyglycine-tRNA world [

37,

44], glycine occupies the most favored anticodon (BCC). Consistent with a GADV-tRNA world [

36,

45,

46,

47,

48,

54], GADV occupy the most favored row of the code, row 4 (BNC). The model explains evolution of related amino acids within code columns (i.e., column 1 (BAN) encodes closely related amino acids Val, Ile, Met and Leu, and ValRS-IA, IleRS-IA, MetRS-IA and LeuRS-IA are closely related AARS enzymes). Features of the genetic code model include explanations for coevolution of amino acid metabolism, amino acid chemistry, homologous AARS enzymes, tRNAomes and stop codons.

During code evolution, previously encoded amino acids initially occupied larger segments of the code. To accommodate entry of newly encoded amino acids, previously encoded amino acids retreated retaining the most favored available anticodon positions. Favored positions in the code relate to favored anticodons according to clear preference rules. For tRNA-34 wobble, A is not utilized in Archaea [

5]. Wobble tRNA-34G is favored. Also, at the base of code evolution, wobble tRNA-34C and tRNA-34U are approximately equivalent. For tRNA-35 and tRNA-36, the preference rules are C>G>U>>A. So, glycine occupies the most favored anticodon (BCC). GADV occupy the most favored row 4 (BNC). Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan occupy disfavored row 1 (BNA) and are late additions to the code. Stop codons occupy disfavored row 1. The model explains why unmodified A is not utilized at a wobble position (i.e., unmodified tRNA-34A is not utilized). The model provides a rational model for serine jumping from column 2 to column 4 of the genetic code (see also [

55]). Essentially, all aspects of genetic code evolution are potentially explained.

Other views of genetic code evolution have been reported [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. We object to codon-centric models with a complexity of 64 codons to describe the initial establishment of the code. The genetic code evolved around the tRNA anticodon and its reading on the coevolving ribosome. Wobbling at tRNA-34 limits the wobble position to purine-pyrimidine discrimination, limiting the complexity of the genetic code to 2x4x4=32 assignments. The standard genetic code gained closure at 20 amino acids plus stops (21 assignments). Late in the process of code evolution, translational fidelity limited further expansions of the code.

6. History of the pre-life to life transition

Sequences of tRNAs relate a history of the pre-life to life transition (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). To replicate RNAs and minihelices in the pre-life world required ligation of RNAs. The emergence of tRNAs shows that minihelices were ligated together (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). The importance of RNA ligation in establishing pre-life genetic innovation and complexity cannot be overstated. Ligation of related and unrelated RNAs led to pre-life chemical and combinatorial complexity, which led to life. Ligation explains how tRNA evolved from 3 31 nt minihelices (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). In order to replicate 31 nt minihelices, RNAs were ligated together, replicated and then processed to generate new minihelices. Because of side reactions of ribozymes/primitive catalysts, in the process of replicating existing RNAs, novel and more complex RNAs such as tRNAs were generated (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). The ribozymes/primitive catalysts required for these processes include: RNA ligases [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]; RNA helicases/chaparones [

68]; complementary RNA template-dependent RNA replicase [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]; and RNA endonucleases [

76,

77]. Very clearly, to support polymer world required a ribozyme/primitive catalyst to generate and replicate RNA repeats.

Scientists have encountered some difficulties generating a ribozyme RNA template-dependent RNA replicase [

75,

78]. Also, to our knowledge, no one has generated a ribozyme/primitive catalyst to generate RNA repeats. These issues may be related. We suggest that the search for ribozymes/primitive catalysts to generate RNA repeats and complementary RNA covalent assemblies be broadened to determine alternate routes to support these activities. Experiments must now be done to reproduce polymer and minihelix world. The RNA reactants and products are known with reasonable certainty (

Figure 5). Only specific ribozymes/primitive catalysts to support the transitions are lacking. Most of these ribozymes have been generated or approximated in vitro.

We posit that complementary stems of 5 nt and 7 nt, which are found in minihelices and tRNAs, were selected because shorter stems were unstable and longer RNA duplexes, generally, were more difficult and slower to unwind using ribozyme/primitive catalyst helicases/chaparones. We posit that the tRNA U-turn loop (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) was selected because it is a tight loop that resists attack by ribozyme nucleases. If a 7 nt anticodon U-turn loop has loop position 1C and 7A (

Figure 6), a Hoogsteen H-bond forms that supports U-turn geometry and loop stability [

42]. Once tRNA evolved, a genetic code became inevitable. Given the pre-life chemical milieu, tRNA was a molecule that could “teach” itself (“learn”) to code [

1,

2,

21].

Carell and colleagues have indicated that modification of the 2’-O of RNA (i.e., 2’-O-methyl) may have stabilized RNA to OH

- hydrolysis and also may have modified ribozyme activities [

38]. RNA modified at the 2’ position is expected to be a precursor to DNA. We posit that many RNA modifications existed in the pre-life world, and RNA modification enzymes coevolved with the code [

79]. For instance, evolution of the genetic code probably required modifications of tRNA-34U, tRNA-37A and tRNA-37G, at a minimum. Probably tRNA-34U methylation-based modifications were necessary to suppress “superwobbling” or 4-way wobbling in which tRNA wobble U reads mRNA wobble A, G, C and U [

79,

80,

81]. Therefore, tRNA-34U methylation-based modifications were necessary to generate 2 codon sectors in the genetic code (i.e., column 3 of the genetic code). It appears that tRNA-37A and tRNA-37G modifications were necessary to read tRNA-36U and tRNA-36A anticodons, respectively.

7. RNA ligation, protein folding and protein pseudosymmetry

The process by which tRNA was generated in pre-life (described above) was critically dependent on RNA ligation. To replicate minihelices, RNA ligation and endonuclease processing was necessary. To generate tRNAs, RNA ligation and then processing to novel products occurred. We posit that RNA ligation was a primary mechanism to generate chemical complexity and genetic innovation in the pre-life world. Type II and type I tRNAs were clearly generated by a process in which RNA ligation played a critical role.

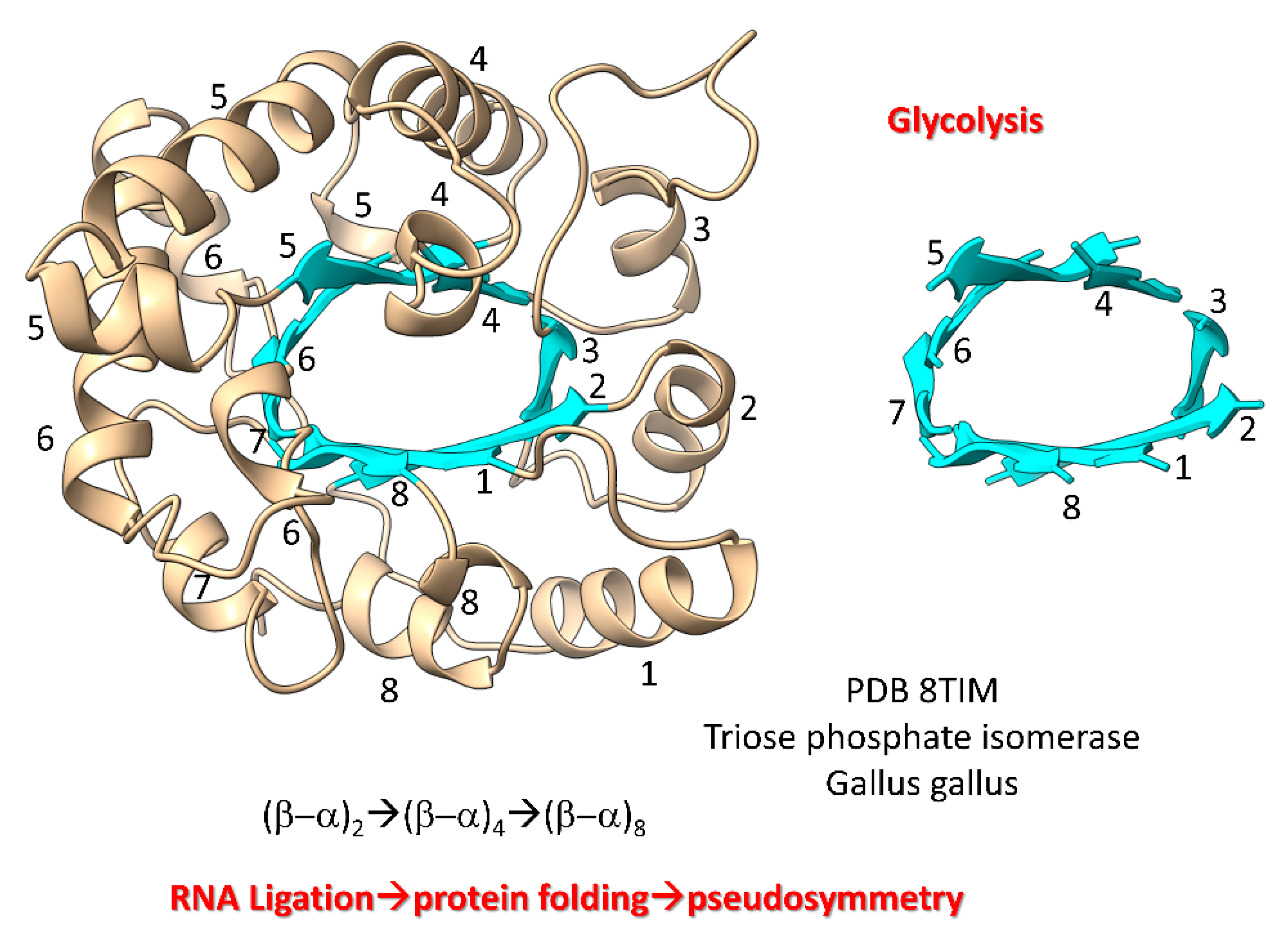

The first proteins (i.e., ribosomal proteins, AARS enzymes, (β–α)

8 barrels (i.e., TIM barrels), (β–α)

8 sheets (Rossmann folds), RNA modification enzymes, RNA and DNA polymerases) coevolved with the genetic code [

82]. We posit that from about the 8 amino acid stage of genetic code evolution, sequence-dependent proteins began to coevolve with the emerging code. We posit that RNA ligation was a central feature in evolution of the first proteins. As examples, we show

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

Figure 7 shows a (β–α)

8 barrel protein (i.e., a TIM barrel protein; TIM for triose phosphate isomerase). Because β-sheets require a partner β-sheet, we posit that (β–α)

8 barrels were generated by ligation of two (β–α)

2 RNAs to form a (β–α)

4 RNA. Ligation of two (β–α)

4 RNAs created a (β–α)

8 RNA that was translated and folded into a (β–α)

8 barrel [

83]. In pre-life, folding proteins into pseudosymmetrical barrels may have resulted from RNA ligations combining multiple identical RNAs. Translation of RNA repeats generated protein repeats that could fold into barrels. Glycolytic enzymes include (β–α)

8 barrels, so we have described evolution of glycolysis in pre-life.

Figure 7.

Evolution of (β–α)8 barrels by RNA ligation, translation and pseudosymmetrical folding.

Figure 7.

Evolution of (β–α)8 barrels by RNA ligation, translation and pseudosymmetrical folding.

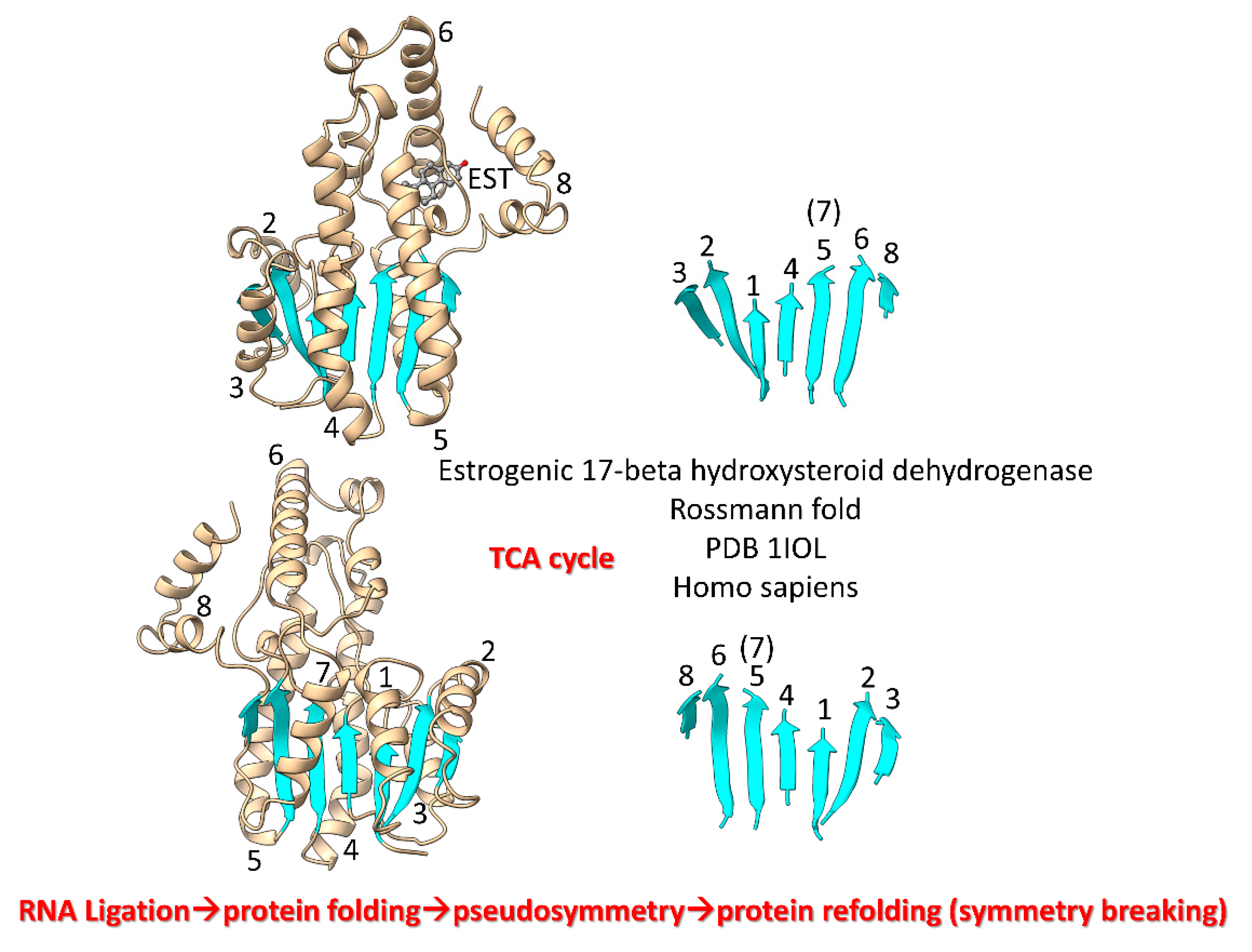

We posit that during pre-life (β–α)

8 barrels were rearranged into (β–α)

8 sheets (Rossmann folds) by protein refolding (

Figure 8) [

84]. TCA cycle enzymes include Rossmann folds. Thus, significant metabolic capacity coevolved with the genetic code in pre-life via RNA ligations, much as described for evolution of type II and type I tRNAs.

Figure 8.

Refolding of a (β–α)8 barrel generated a (β–α)8 sheet. β7 lost its β-sheet partners in the refolding. Two views are shown. EST is estradiol. Helices are numbered in the left images. β-sheets are numbered in the right images. .

Figure 8.

Refolding of a (β–α)8 barrel generated a (β–α)8 sheet. β7 lost its β-sheet partners in the refolding. Two views are shown. EST is estradiol. Helices are numbered in the left images. β-sheets are numbered in the right images. .

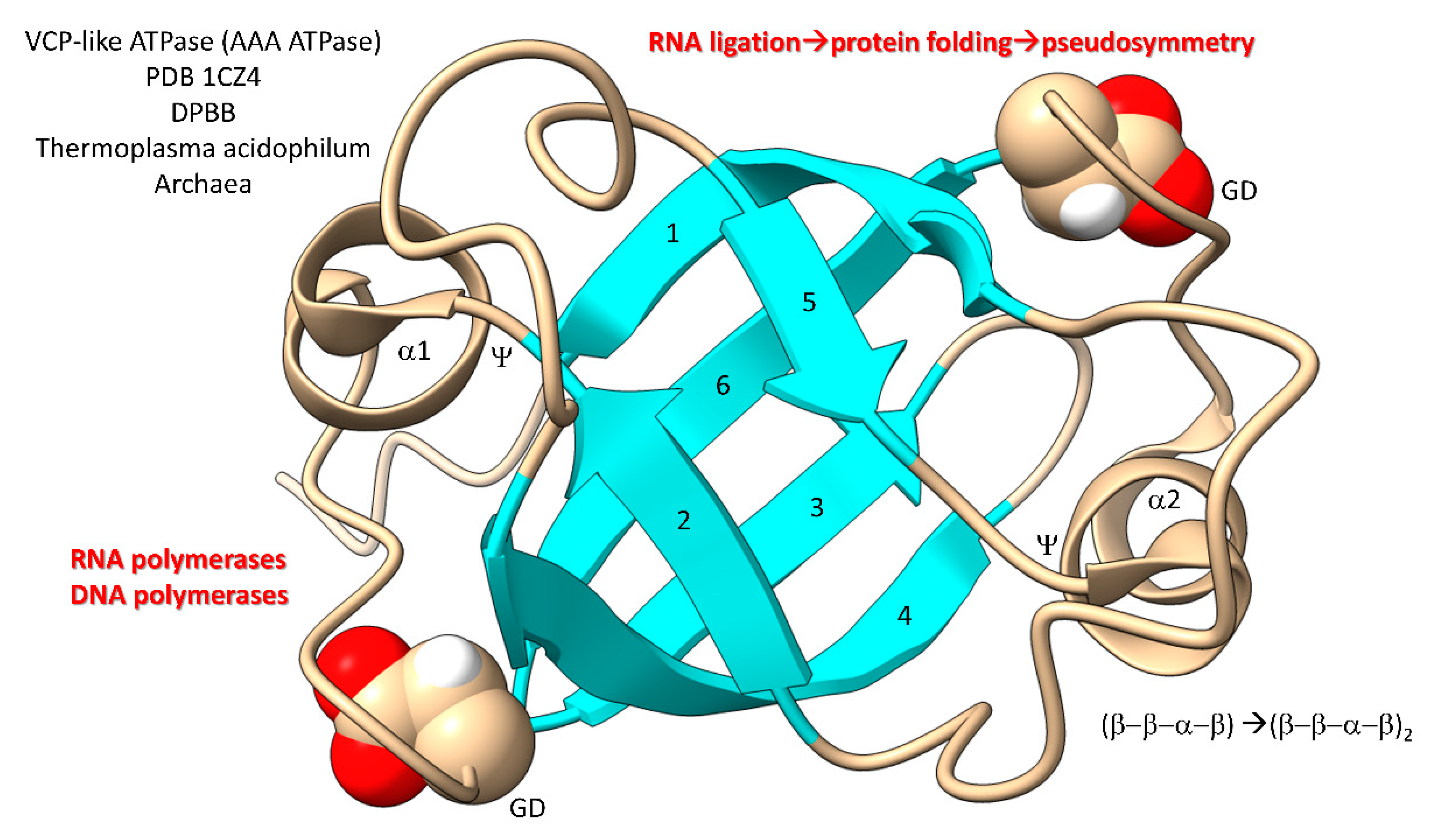

In

Figure 9, a domain of a AAA-ATPase is shown [

85,

86,

87]. This pseudosymmetrical barrel is a double-Ψ–β-barrel (β–β–α–β)

2. We posit that the double-Ψ–β-barrel was formed from ligation of two (β–β–α–β) RNAs followed by translation and pseudosymmetrical folding. PolD (an archaeal DNA polymerase) and multi-subunit RNA polymerases are 2 double-Ψ–β-barrel polymerases. The GD motif in the loop separating β5 and β6 was the precursor to the NADFDGD motif that is highly conserved in multi-subunit RNA polymerases [

88,

89]. We posit that these core life functions were generated in pre-life via RNA ligation, translation and pseudosymmetrical folding. Thus, based on the apparent RNA ligation mechanism for tRNA evolution, glycolysis, the TCA cycle, AAA-ATPases, DNA polymerases and RNA polymerases may have been generated during pre-life [

90].

Figure 9.

Generation of double-Ψ–β-barrels in pre-life.

Figure 9.

Generation of double-Ψ–β-barrels in pre-life.

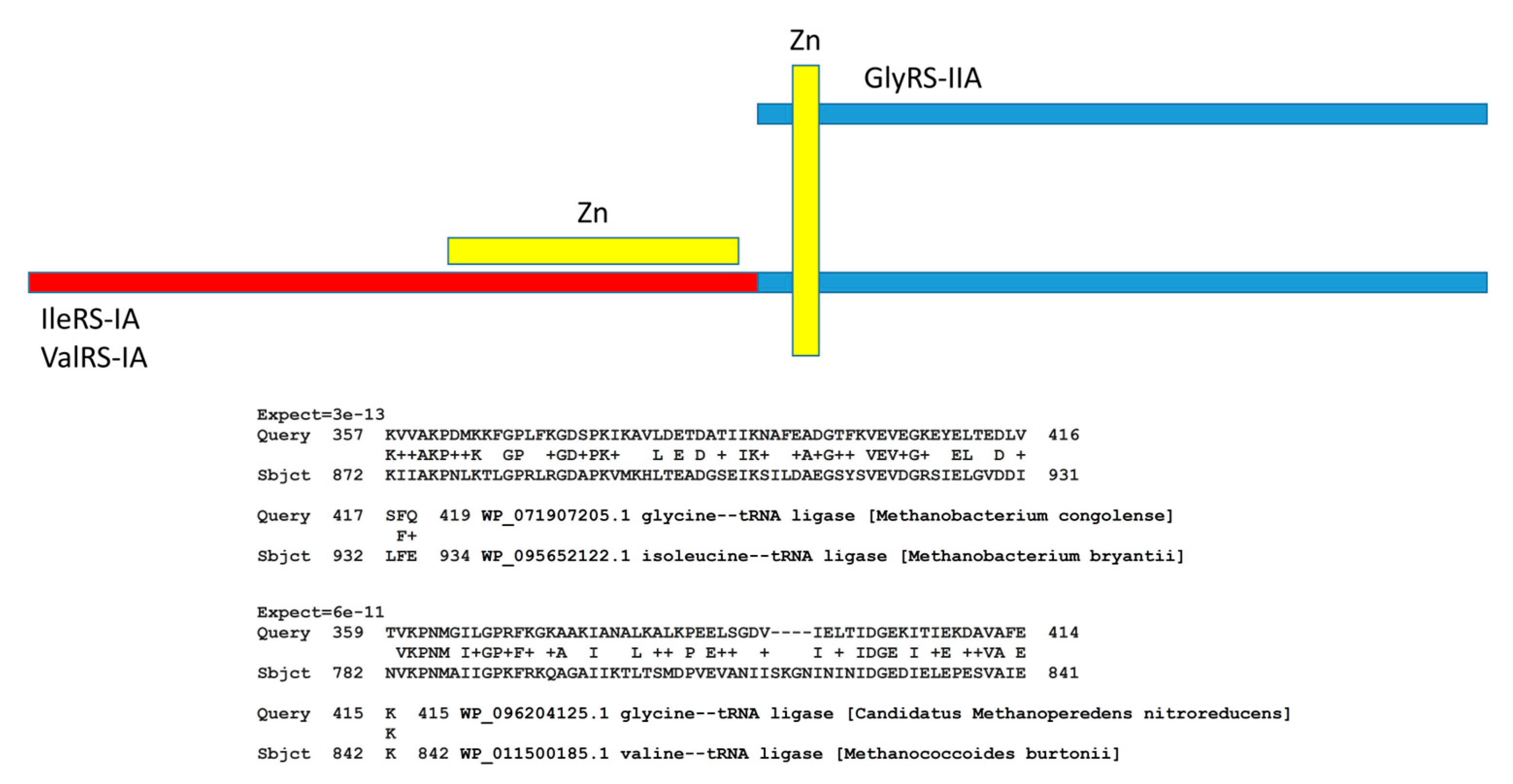

AARS enzymes coevolved with tRNAomes and the genetic code. The evolution of AARS enzymes, however, has been improperly understood [

1,

2,

22]. We have attempted to clarify how AARS enzymes evolved. Despite their different folds, class II and class I AARS enzymes are simple homologs (

Figure 10). Notably, GlyRS-IIA is a homolog of IleRS-IA and ValRS-IA. In ancient Archaea, these enzymes often share a Zn finger and significant homology. At the bottom of the figure, we show local alignments of the same segment of GlyRS-IIA with homologous segments of IleRS-IA and ValRS-IA. Initially, class II and class I AARS were not thought to be homologous because these enzymes have distinct folds. We posit that, in pre-life, a primitive ValRS-IA was derived from a primitive GlyRS-IIA by ligation of a distinct RNA encoding the ValRS-IA N-terminal segment, followed by translation and folding. Addition of the N-terminal ValRS-IA extension determined the distinct class I AARS fold, as we have described.

Figure 10.

Evolution of AARS enzymes. Class II AARS are simple homologs of class I AARS. The blue segments include homologous sequences including a Zn finger. The red segment is unique to class I AARS and directs the distinct class I AARS fold. At the bottom of the figure are two alignments demonstrating homology of GlyRS-IIA (class II), IleRS-IA (class I) and ValRS-IA (class I). + indicates amino acid similarity. Expect values indicate homology of sequences.

Figure 10.

Evolution of AARS enzymes. Class II AARS are simple homologs of class I AARS. The blue segments include homologous sequences including a Zn finger. The red segment is unique to class I AARS and directs the distinct class I AARS fold. At the bottom of the figure are two alignments demonstrating homology of GlyRS-IIA (class II), IleRS-IA (class I) and ValRS-IA (class I). + indicates amino acid similarity. Expect values indicate homology of sequences.

8. Conclusions

In the context of pre-life, tRNA was a molecule that could teach itself to code. Because tRNAPri sequences were highly patterned and their order conserved, evolution of type II and type I tRNAs is a solved problem. The tRNAomes of LUCA and organisms diverged from type I and type II tRNAs by duplications, mutations and repurposing. For obvious reasons (see above), no convergent or accretion model can be reasonable to describe earliest tRNA evolution. To build the genetic code, evolution of mRNA codons conformed to the evolution of tRNAome anticodons.

The genetic code coevolved with amino acid metabolism, polypeptides, tRNAomes, mRNA, AARS enzymes, first proteins and enzymes, tRNA modification enzymes (some of which depend on relics of (β–α)

8 barrels) [

91] and protocells. The patterns of relatedness within tRNAomes and AARS in ancient Archaea relate a history of evolution of the genetic code. We posit that RNA ligation was a major driving force for evolution of the complexity of the first RNAs and folding, complexity and pseudosymmetry of first proteins.

To teach the biological sciences, integrate and emphasize genetic coding, evolution, sequence analysis, translation, structure and the central functions of RNA in biology. The history of tRNA chemical evolution, as written into and conserved in living genetic code, relates these fundamental lessons and describes the pre-life to life transition from about 4 billion years ago. Evolution of tRNA combines aspects of evolution, the birth of biology on Earth, origin of life, chemical evolution, sequence pattern recognition, coding and decoding, tRNA modifications, learning and genetic memory and evolution of the patterning of the genetic code. Because tRNA evolution was first solved by inspection and as a puzzle, tRNA evolution should be of interest to gamers. Because tRNA evolution is a problem in biological coding, learning and problem-solving, tRNA evolution is a subject for programmers and psychologists. Sentient humans on Earth must know this content.

Author Contributions

LL and ZB wrote the paper and crafted the figures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of the genetic code. Transcription 2021, 12, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of Life on Earth: tRNA, Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases and the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Z.F. The 3-Minihelix tRNA Evolution Theorem. J Mol Evol 2020, 88, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ferre-D'Amare, A.R. The tRNA Elbow in Structure, Recognition and Evolution. Life (Basel) 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhling, F.; Morl, M.; Hartmann, R.K.; Sprinzl, M.; Stadler, P.F.; Putz, J. tRNAdb 2009: compilation of tRNA sequences and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaswamy, U.; Fox, G.E. RNA ligation and the origin of tRNA. Orig Life Evol Biosph 2003, 33, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. RNA Rings Strengthen Hairpin Accretion Hypotheses for tRNA Evolution: A Reply to Commentaries by Z.F. Burton and M. Di Giulio. J Mol Evol 2020, 88, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. The primordial tRNA acceptor stem code from theoretical minimal RNA ring clusters. BMC Genet 2020, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. An RNA Ring was Not the Progenitor of the tRNA Molecule. J Mol Evol 2020, 88, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. The Uroboros Theory of Life's Origin: 22-Nucleotide Theoretical Minimal RNA Rings Reflect Evolution of Genetic Code and tRNA-rRNA Translation Machineries. Acta Biotheor 2019, 67, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. A comparison between two models for understanding the origin of the tRNA molecule. J Theor Biol 2019, 480, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The origin of the tRNA molecule: Independent data favor a specific model of its evolution. Biochimie 2012, 94, 1464–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. Formal proof that the split genes of tRNAs of Nanoarchaeum equitans are an ancestral character. J Mol Evol 2009, 69, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. A comparison among the models proposed to explain the origin of the tRNA molecule: A synthesis. J Mol Evol 2009, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. Permuted tRNA genes of Cyanidioschyzon merolae, the origin of the tRNA molecule and the root of the Eukarya domain. J Theor Biol 2008, 253, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The non-monophyletic origin of the tRNA molecule and the origin of genes only after the evolutionary stage of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). J Theor Biol 2006, 240, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The origin of the tRNA molecule: implications for the origin of protein synthesis. J Theor Biol 2004, 226, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.J.; Caetano-Anolles, G. The origin and evolution of tRNA inferred from phylogenetic analysis of structure. J Mol Evol 2008, 66, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Spontaneous evolution of circular codes in theoretical minimal RNA rings. Gene 2019, 705, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Glade, N.; Moreira, A.; Vial, L. RNA relics and origin of life. Int J Mol Sci 2009, 10, 3420–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. A tRNA- and Anticodon-Centric View of the Evolution of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases, tRNAomes, and the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Kim, Y.; Burton, Z.F. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase evolution and sectoring of the genetic code. Transcription 2018, 9, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Du, N.; Kim, Y.; Sun, Y.; Burton, Z.F. Rooted tRNAomes and evolution of the genetic code. Transcription 2018, 9, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Root-Bernstein, R.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA structure and evolution and standardization to the three nucleotide genetic code. Transcription 2017, 8, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, R.; Kim, Y.; Sanjay, A.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA evolution from the proto-tRNA minihelix world. Transcription 2016, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.S.; Gulen, B.; Norris, A.M.; Kovacs, N.A.; Bernier, C.R.; Lanier, K.A.; Fox, G.E.; Harvey, S.C.; Wartell, R.M.; Hud, N.V. , et al. History of the ribosome and the origin of translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 15396–15401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.S.; Bernier, C.R.; Hsiao, C.; Norris, A.M.; Kovacs, N.A.; Waterbury, C.C.; Stepanov, V.G.; Harvey, S.C.; Fox, G.E.; Wartell, R.M. , et al. Evolution of the ribosome at atomic resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 10251–10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.S.; Bernier, C.R.; Gulen, B.; Waterbury, C.C.; Hershkovits, E.; Hsiao, C.; Harvey, S.C.; Hud, N.V.; Fox, G.E.; Wartell, R.M. , et al. Secondary structures of rRNAs from all three domains of life. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T.; Rego, T.G.; Jose, M.V. Origin of the 16S Ribosomal Molecule from Ancestor tRNAs. J Mol Evol 2021, 89, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T.; Jose, M.V. Transfer RNA: The molecular demiurge in the origin of biological systems. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2020, 153, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T.; Rego, T.G.; Jose, M.V. tRNA Core Hypothesis for the Transition from the RNA World to the Ribonucleoprotein World. Life (Basel) 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, S.T.; Rego, T.G.; Jose, M.V. Origin and evolution of the Peptidyl Transferase Center from proto-tRNAs. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T.; do Rego, T.G.; Jose, M.V. Evolution of transfer RNA and the origin of the translation system. Front Genet 2014, 5, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T. Suggested phylogeny of tRNAs based on the construction of ancestral sequences. J Theor Biol 2013, 335, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, J.; Kwiatkowski, W.; Riek, R. Peptide Amyloids in the Origin of Life. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 3735–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Evolutionary Steps in the Emergence of Life Deduced from the Bottom-Up Approach and GADV Hypothesis (Top-Down Approach). Life (Basel) 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, H.S.; Patrick, W.M. Genetic code evolution started with the incorporation of glycine, followed by other small hydrophilic amino acids. J Mol Evol 2014, 78, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, F.; Escobar, L.; Xu, F.; Wegrzyn, E.; Nainyte, M.; Amatov, T.; Chan, C.Y.; Pichler, A.; Carell, T. A prebiotically plausible scenario of an RNA-peptide world. Nature 2022, 605, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kowiatek, B.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. Type-II tRNAs and Evolution of Translation Systems and the Genetic Code. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, R.; Yokoyama, S. Crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase from the archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii reveals a novel editing domain orientation. J Mol Biol 2005, 346, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biou, V.; Yaremchuk, A.; Tukalo, M.; Cusack, S. The 2.9 A crystal structure of T. thermophilus seryl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNA(Ser). Science 1994, 263, 1404–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Moore, P.B. The crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 1.93 A resolution: a classic structure revisited. RNA 2000, 6, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, M.; Surman, A.J.; Cooper, G.J.T.; Suarez-Marina, I.; Hosni, Z.; Lee, M.P.; Cronin, L. Formation of oligopeptides in high yield under simple programmable conditions. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, H.S.; Tate, W.P. Evidence from glycine transfer RNA of a frozen accident at the dawn of the genetic code. Biol Direct 2008, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. [GADV]-protein world hypothesis on the origin of life. Orig Life Evol Biosph 2014, 44, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Pseudo-replication of [GADV]-proteins and origin of life. Int J Mol Sci 2009, 10, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, T.; Fukushima, J.; Maruyama, M.; Iwamoto, R.; Ikehara, K. Catalytic activities of [GADV]-peptides. Formation and establishment of [GADV]-protein world for the emergence of life. Orig Life Evol Biosph 2005, 35, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Possible steps to the emergence of life: the [GADV]-protein world hypothesis. Chem Rec 2005, 5, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansma, H.G. Better than Membranes at the Origin of Life? Life (Basel) 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciamore, S.; Di Giulio, M. The presence in tRNA molecule sequences of the double hairpin, an evolutionary stage through which the origin of this molecule is thought to have passed. J Mol Evol 2011, 72, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djumagulov, M.; Demeshkina, N.; Jenner, L.; Rozov, A.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. Accuracy mechanism of eukaryotic ribosome translocation. Nature 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Wolff, P.; Grosjean, H.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G.; Westhof, E. Tautomeric G*U pairs within the molecular ribosomal grip and fidelity of decoding in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 7425–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Demeshkina, N.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. New Structural Insights into Translational Miscoding. Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Why Were [GADV]-amino Acids and GNC Codons Selected and How Was GNC Primeval Genetic Code Established? Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, M.; Takino, R.; Ishida, Y.; Inouye, K. Evolution of the genetic code; Evidence from serine codon use disparity in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 28572–28575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and Evolution of the Universal Genetic Code. Annu Rev Genet 2017, 51, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and evolution of the genetic code: the universal enigma. IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. Fitting the standard genetic code into its triplet table. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. Evolution of the Standard Genetic Code. J Mol Evol 2021, 89, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. Optimal Evolution of the Standard Genetic Code. J Mol Evol 2021, 89, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. Crick Wobble and Superwobble in Standard Genetic Code Evolution. J Mol Evol 2021, 89, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wills, P.R. The Roots of Genetic Coding in Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Duality. Annu Rev Biochem 2021, 90, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasGupta, S.; Zhang, S.; Szostak, J.W. Molecular Crowding Facilitates Ribozyme-Catalyzed RNA Assembly. ACS Cent Sci 2023, 9, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, M.; Mutsuro-Aoki, H.; Ando, T.; Tamura, K. Molecular Anatomy of the Class I Ligase Ribozyme for Elucidation of the Activity-Generating Unit. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Yokobayashi, Y. RNA ligase ribozymes with a small catalytic core. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 8584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasGupta, S.; Zhang, S.J.; Smela, M.P.; Szostak, J.W. RNA-Catalyzed RNA Ligation within Prebiotically Plausible Model Protocells. Chemistry 2023, 29, e202301376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, T.; DasGupta, S.; Duzdevich, D.; Oh, S.S.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of ribozyme ligases that use prebiotically plausible 2-aminoimidazole-activated substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 5741–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.-C.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Ke, G.; Cao, X.; Fan, C.; Yang, C.J.; Liang, H.; Tian, Z.-Q. RNA can function as molecular chaperone for RNA folding. Giant 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjhung, K.F.; Sczepanski, J.T.; Murtfeldt, E.R.; Joyce, G.F. RNA-Catalyzed Cross-Chiral Polymerization of RNA. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 15331–15339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjhung, K.F.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Horning, D.P.; Joyce, G.F. An RNA polymerase ribozyme that synthesizes its own ancestor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 2906–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, D.P.; Bala, S.; Chaput, J.C.; Joyce, G.F. RNA-Catalyzed Polymerization of Deoxyribose, Threose, and Arabinose Nucleic Acids. ACS Synth Biol 2019, 8, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, B.; Horning, D.P.; Joyce, G.F. 3'-End labeling of nucleic acids by a polymerase ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, B.; Joyce, G.F. A reverse transcriptase ribozyme. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, D.P.; Joyce, G.F. Amplification of RNA by an RNA polymerase ribozyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 9786–9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinness, K.E.; Joyce, G.F. In search of an RNA replicase ribozyme. Chem Biol 2003, 10, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.N.; Liu, Y.Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Zou, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, C.Y. Construction of Multiple DNAzymes Driven by Single Base Elongation and Ligation for Single-Molecule Monitoring of FTO in Cancer Tissues. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 12974–12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Sun, C.; Du, J.; Xing, X.; Wang, F.; Dong, H. RNA-Cleaving DNAzyme-Based Amplification Strategies for Biosensing and Therapy. Adv Healthc Mater 2023, 12, e2300367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlinova, P.; Lambert, C.N.; Malaterre, C.; Nghe, P. Abiogenesis through gradual evolution of autocatalysis into template-based replication. FEBS Lett 2023, 597, 344–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. "Superwobbling" and tRNA-34 Wobble and tRNA-37 Anticodon Loop Modifications in Evolution and Devolution of the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkatib, S.; Scharff, L.B.; Rogalski, M.; Fleischmann, T.T.; Matthes, A.; Seeger, S.; Schottler, M.A.; Ruf, S.; Bock, R. The contributions of wobbling and superwobbling to the reading of the genetic code. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1003076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalski, M.; Karcher, D.; Bock, R. Superwobbling facilitates translation with reduced tRNA sets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008, 15, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.C.; Preiner, M.; Xavier, J.C.; Zimorski, V.; Martin, W.F. The last universal common ancestor between ancient Earth chemistry and the onset of genetics. PLoS Genet 2018, 14, e1007518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Romero, S.; Kordes, S.; Michel, F.; Hocker, B. Evolution, folding, and design of TIM barrels and related proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2021, 68, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, K.E.; Kinch, L.N.; Dustin Schaeffer, R.; Pei, J.; Grishin, N.V. A Fifth of the Protein World: Rossmann-like Proteins as an Evolutionarily Successful Structural unit. J Mol Biol 2021, 433, 166788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, V.; Dunin-Horkawicz, S.; Habeck, M.; Coles, M.; Lupas, A.N. The GD box: a widespread noncontiguous supersecondary structural element. Protein Sci 2009, 18, 1961–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, V.; Koretke, K.K.; Coles, M.; Lupas, A.N. Cradle-loop barrels and the concept of metafolds in protein classification by natural descent. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2008, 18, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, M.; Hulko, M.; Djuranovic, S.; Truffault, V.; Koretke, K.; Martin, J.; Lupas, A.N. Common evolutionary origin of swapped-hairpin and double-psi beta barrels. Structure 2006, 14, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Early Evolution of Transcription Systems and Divergence of Archaea and Bacteria Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8. 2021; 8. [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Krupovic, M.; Ishino, S.; Ishino, Y. The replication machinery of LUCA: common origin of DNA replication and transcription. BMC Biol 2020, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.C.; Sousa, F.L.; Mrnjavac, N.; Neukirchen, S.; Roettger, M.; Nelson-Sathi, S.; Martin, W.F. The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 16116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalm, E.L.; Grove, T.L.; Booker, S.J.; Boal, A.K. Crystallographic capture of a radical S-adenosylmethionine enzyme in the act of modifying tRNA. Science 2016, 352, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).