1. Introduction

Emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane (CH

4) from permafrost-affected areas in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions have received significant research attention due to their potential to increase the atmospheric methane burden as permafrost thaws [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As shown by the recent analyses, this methane source might have been overestimated without considering high-affinity (or atmospheric) methane oxidation in soils in high northern latitudes [

5,

6]. The first report of atmospheric CH

4 uptake by permafrost-affected Alaskan tundra soils was published in 1990 [

7]. Since that time, atmospheric CH

4 uptake has been reported for both cryosols of high organic carbon and polar desert mineral cryosols [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Atmospheric CH

4 uptake in these ecosystems is due to activity of aerobic methanotrophic bacteria, which utilize methane as a source of carbon and energy [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Key enzyme of the methanotrophic metabolism is particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO), which is present in most currently described methanotroph species. Accordingly, the

pmoA gene coding for the active-site polypeptide of pMMO is the most frequently used molecular marker in cultivation-independent detection of aerobic methanotrophs [

17].

Attempts to identify atmospheric CH

4-oxidizers thriving in terrestrial Arctic and sub-Arctic ecosystems have been made in a number of studies that employed a wide array of cultivation-independent molecular approaches [

9,

11,

18,

19]. Notably, nearly all of these studies reported the occurrence of “high-affinity” methanotrophic bacteria from as-yet-uncultivated group called Upland Soil Cluster

Alphaproteobacteria (USCα) after Knief et al. [

20]. The first evidence for the existence of these methanotrophs was obtained for boreal upland soils that demonstrated active atmospheric CH

4 oxidation [

21]. The

pmoA sequences retrieved in this study could not be affiliated to any of the earlier described methanotrophs and displayed only a distant relationship to

pmoA gene from

Methylocapsa acidiphila B2, an alphaproteobacterium isolated from acidic peat [

22,

23]. The

pmoA sequences of USCα methanotrophs have been recovered from many acidic and near-neutral boreal, subarctic and arctic upland soils [

9,

19,

20,

24,

25,

26].

Since methanotroph affiliation with USCα group has long been defined by the PmoA phylogeny, exact taxonomic position of these bacteria remained unknown for a long time and no 16S rRNA gene sequences were available for members of this group. Reconstruction of the first draft genome of a USCα methanotroph from a boreal acidic soil revealed its affiliation to the alphaproteobacterial family

Beijerinckiaceae and its close phylogenetic relationship with methanotrophic bacteria of the genus

Methylocapsa [

27]. The metagenomic assembly obtained in this study was classified as belonging to the new taxon, which was tentatively named

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis.

Further isolation of a pure culture of the first cultivated member of the USCα clade, strain MG08, provided valuable insights into the physiology and metabolism of these methanotrophs [

28]. Strain MG08 showed the ability of to grow at atmospheric concentrations of CH

4 and to assimilate carbon from both CH

4 and CO

2. The ability to fix N

2 and to oxidize other atmospheric trace gases, CO and H

2, were also confirmed for this methanotroph [

28]. Apparently, these bacteria thrive in arctic habitats due to the ability to scavenge atmospheric trace gases. Based on the results of comparative genome analysis, strain MG08 was classified as a member of the genus

Methylocapsa and was tentatively named ‘

Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08. Although the PmoA sequence of ‘

Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 clusters within the radiation of USCα PmoA clade, it does not correspond to the major group of PmoA sequences, which are most often retrieved from upland soils.

Several metagenome-assembled genome sequences (MAGs) of USCα-related methanotrophs have been retrieved from high Arctic ecosystems. One of them, Canadian MAG AHI, was obtained from an acidic carbon-poor cryosol, which was shown to consistently consume atmospheric methane, at Axel Heiberg Island in the Canadian high Arctic [

11]. Other two MAGs, named USC1 and USC2, were assembled from the active layer of a permafrost thaw gradient in Stordalen Mire, Abisko, Sweden [

18]. Although these MAGs were addressed as ‘closely related to USCα’ group, they did not fall within the radiation of ‘true’ USCα methanotrophs represented by

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis.

In this study, we report isolation and characterization of a Methylocapsa-like bacterium, strain D3K7, which represents this earlier uncultivated subgroup of USCα-related methanotrophs from Arctic and sub-Arctic terrestrial habitats. Strain D3K7 was isolated from a sub-arctic sandy loam soil of Northern Russia and formed a common phylogenetic clade with the above discussed MAGs retrieved the Canadian and Swedish high Arctic. This clade occupies a phylogenetic position in between characterized Methylocapsa methanotrophs (including ‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08) and as-yet-uncultivated ‘true’ representatives of the USCα group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Site

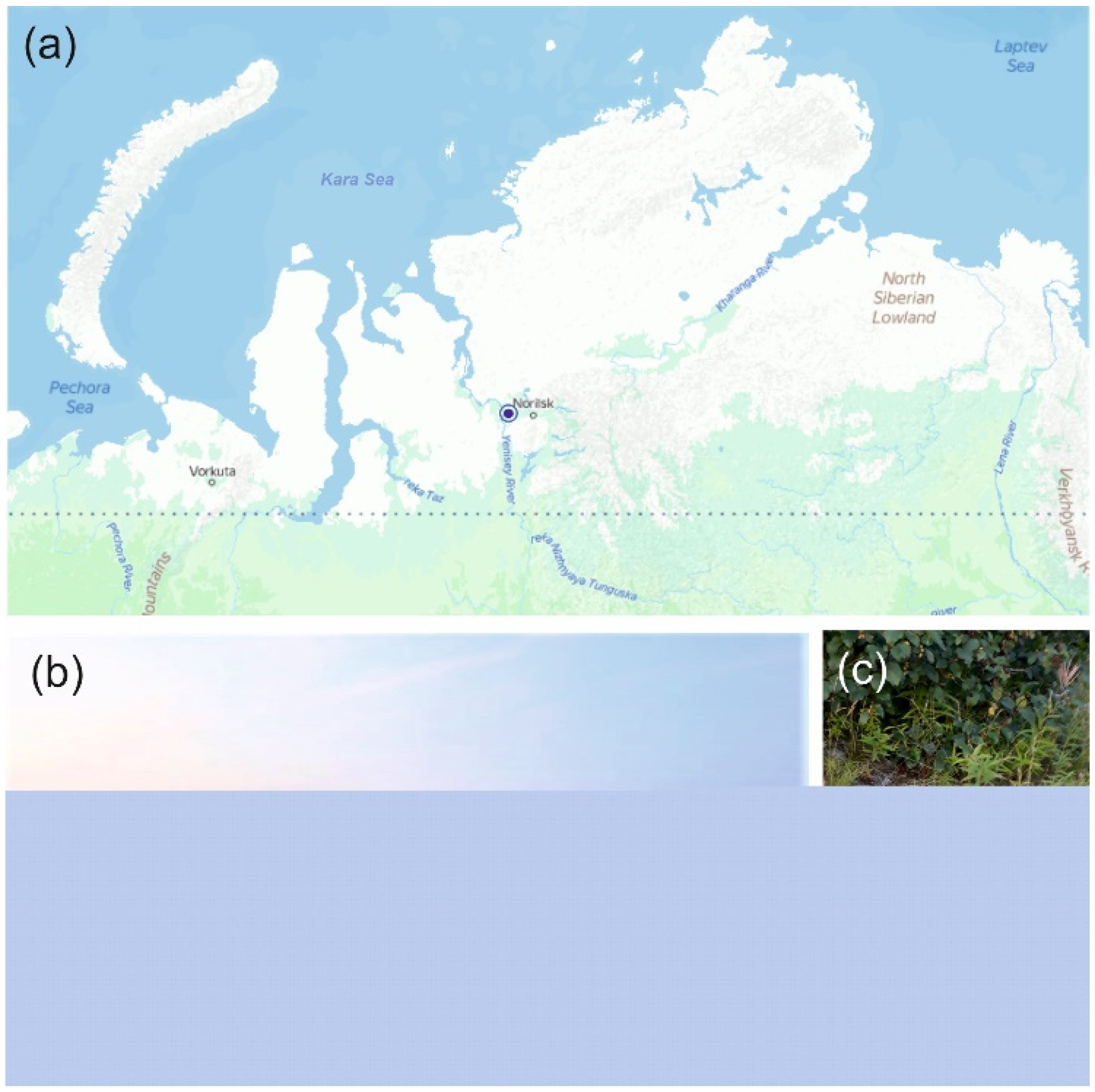

The samples of sandy loam soil used in this study were collected in July 2019 from a subarctic region of Northern Russia. The sampling site was located on the shore of the River Kosaya, a right tributary of the River Dudinka, Northwestern Russia, Krasnoyarsk Krai (69.4162 N, 86.5324 E) (

Figure 1a). The sparse vegetation cover was composed of

Equisétum,

Lycopódium,

Chamaenerion, and

Polytrichum species;

Salix arctica,

Bétula nána,

Pinus sp. and

Álnus sp. were also present (

Figure 1b). No distinctive surface organic layer was seen in the soil profile (

Figure 1c). Three individual soil samples (~500 g each) were collected from three sampling plots located on a distance of 40-50 m from each other. The samples were transported to the laboratory and used for further molecular analyses and cultivation experiments.

Figure 1.

Location and some characteristics of the study site: (a) - location of the study site on the map of northern Russia; (b) - vegetation cover at the sampling site; (c) - soil profile.

Figure 1.

Location and some characteristics of the study site: (a) - location of the study site on the map of northern Russia; (b) - vegetation cover at the sampling site; (c) - soil profile.

2.2. Soil DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing of 16S rRNA Genes

Total DNA was isolated from 0.25 g of soil samples using FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The V3-V4 variable region of the prokaryotic 16S rRNA genes was obtained by PCR with primers 341F (5’- CCTAYGGGDBGCWSCAG) and 806R (5’- GGACTACNVGGGTHTCTAAT) [

29]. PCR fragments were barcoded using Nextera XT Index Kit v2 (Illumina, USA). The PCR fragments were purified using Agencourt AMPure Beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and quantified using Qubitn dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Then all the amplicons were pooled together in equal moral amounts and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq instrument (2 x 300 nt reads). The pool of 16S rRNA gene sequences was analyzed with QIIME2 v.2019.10 (

https://qiime2.org) [

30]. Q-score and VSEARCH uchime plugin was used for sequence quality control, denoising and chimera filtering [

31,

32]. Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were clustered applying VSEARCH plugin [

32] with open-reference function using Silva v. 138 database [

33] with 97% identity and following singleton removal. Taxonomy assignment was performed using BLAST against Silva v. 138 database with 80% identity.

2.3. Enrichment and Isolation of Methane-Oxidizing Bacteria

The liquid mineral medium M2 (pH 6.0–6.3), which was used in our previous studies for isolation of

Methylocapsa species from northern terrestrial habitats [

23,

34], was employed for obtaining methane-oxidizing microbial consortia from the studied subarctic soil. In contrast to our previous studies, this medium was supplied with 10% (v/v) of the soil extract. The latter was prepared by mixing 100 g of soil with 500 ml of distilled water, shaking the resulting soil suspension for 1 hour at 120 rpm, centrifuging it at 8 rpm for 10 min, and using sediment-free water phase as a medium supplement. A set of three 500-ml serum bottles filled with 50 ml of the mineral medium with soil extract (gas phase: liquid phase ratio of 9:1) were used for these incubation experiments. 2 g of soil was used to inoculate each of these bottles, after which they were sealed with butyl rubber septa. Methane and CO

2 were injected in the bottle headspaces using syringes equipped with disposable filters (0.22 µm) up to final concentrations of 10 and 1% (v/v), respectively, and the bottles were incubated horizontally at 20 °C without shaking in the dark. The gas phase in the bottles was replaced with a freshly prepared gas mixture once in 2 months. After six months of incubation, aliquots of the culture suspensions from the bottles were sampled for microscopic examination. One bottle containing a well-developed microbial consortium dominated with small, slightly curved cells of

Methylocapsa-like morphology was selected for preparing a dilution series. Aliquots of this dilution series were streaked on polycarbonate filters (Nucleopore Track-Etch membrane with pore size 0.2 µm). Inoculated filters were placed in the wells of the 6-well plate filled with the liquid medium M2 and were incubated at 20 °C in desiccators containing approximately 30% (v/v) methane and 5% CO

2 (v/v) in the air. Similar approach was used before for isolating a pure culture of ‘

Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 [

28]. The colonies appearing on the filters were picked and restreaked on the new filters until colonies containing morphologically uniform cells were obtained. One of these colonies was transferred back to the serum bottle with the liquid medium M2 and designated strain D3K7. Culture purity of this isolate was verified by examination using phase-contrast microscopy and by plating on 10-fold diluted Luria–Bertani agar (1.0% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1.0% NaCl).

2.4. Microscopic Studies

Morphological observations and cell-size measurements were made with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope and Axiovision 4.2 software (Zeiss). The electron microscopy analysis was performed as described in our recent study [

35].

2.5. Growth Experiments

Physiological tests were carried out on cultures grown in liquid medium M2 with methane as the growth substrate. Growth of strain D3K7 was monitored by nephelometry at 600 nm using a “BioPhotometer” spectrophotometer (Eppendorf) for 2 weeks under a variety of conditions, including temperatures of 2 – 37°C, pH values of 3.8 – 8.5, and NaCl concentrations of 0 – 1.0 % (w/v). The following carbon sources (each at a concentration of 0.05% w/v) were examined to determine the range of substrates utilized by strain D3K7: methanol, ethanol, formate, formaldehyde, glucose, fructose, arabinose, lactose, sucrose, maltose, galactose, acetate, citrate, oxalate, malate, pyruvate, acetate and succinate. The capacity to utilize methanol at concentrations from 0.01 to 1% (v/v) was determined in liquid M2 medium supplemented with methanol.

Growth dynamics of strain D3K7 in the presence of two substrates, methane and acetate, was examined using 120 ml screw-cap serum bottles filled with 10 ml of M2 medium (pH 6.5) with/or without 0.05% (w/v) of sodium acetate. Methane (where necessary) was injected in the bottle headspaces using syringes equipped with disposable filters (0.22 µm) up to final concentrations of 10% (v/v). Bottles were inoculated with cells of strain D3K7 and incubated on a rotary shaker (120 r.p.m.) at 22 – 25°C for 5 days.

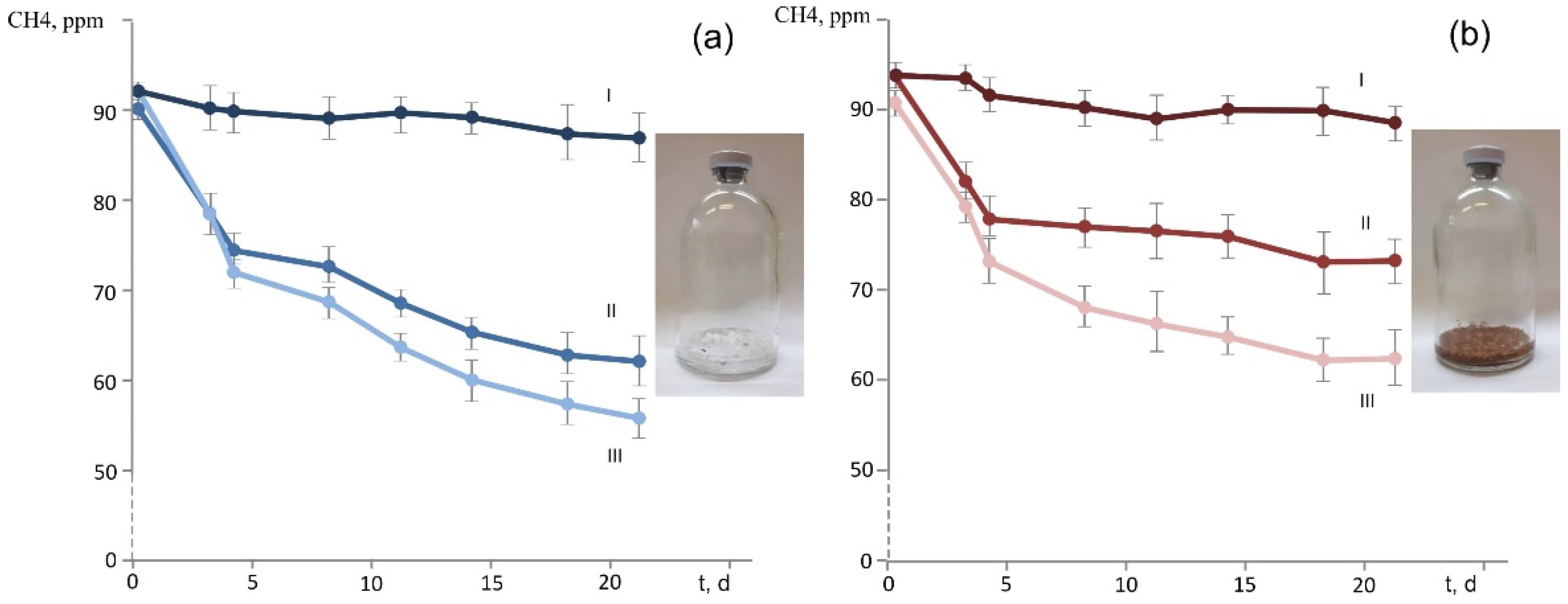

The ability of strain D3K7 to oxidize methane when the latter is present in low concentrations (below 100 p.p.m.v) was assessed using two types of experimental incubations: (1) conventional liquid cultures of strain D3K7 and (2) bottles with adsorbent materials (perlite or vermiculite) inoculated with cells of strain D3K7. In the first case, 120 ml flasks were filled with 4 ml of grown culture of strain D3K7 (OD600 0.8) and 1 ml of fresh M2 medium (pH 6.5) with or without 0.05% (w/v) sodium acetate. Methane (where necessary) was injected in the flasks up to the concentrations of ~100 p.p.m.v. Flasks were incubated under static conditions at 22°C for 3 weeks.

In the second case, 3 ml of cell suspensions (see above) were added to 120 ml screw-cap flasks containing 300 mg sterilized perlite or vermiculite granules. Methane was injected in the headspace up to the final concentration of ~100 p.p.m.v. Control incubations were prepared in the same way but were not inoculated with cells of strain D3K7. The flasks were incubated at 22°C for 3 weeks. Gas samples were taken from experimental flasks at regular time intervals for determination of CH4 concentrations using a Crystal 5000.1 gas chromatograph (Chromatek, Russia).

2.6. Genome Sequencing and Annotation

Culture of strain D3K7 was grown in the liquid M2 as described above. The cells were harvested after incubation at 20 °C for 14 days. Genomic DNA extraction was done using the standard acetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) and phenol-chloroform protocol [

36]. The genomic paired-end (2×300) library was prepared with a NEBNext ultra II DNA Library kit (New England Biolabs) and sequenced using a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Primer sequences were removed from the Illumina reads using Cutadapt v.1.17 [

37] with the default settings, and low quality read ends were trimmed using Sickle v.1.33 (option q=30) (

https://github.com/najoshi/sickle). Nanopore sequencing library was prepared using the 1D ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK108, Oxford Nanopore, UK). Sequencing was performed on an R9.4 flow cell (FLO-MIN106) using MinION device. Hybrid assembly of short and long reads was performed using Unicycler v.0.4.8 [

38] and refined using Pilon v1.24 [

39]. Assemblies were evaluated with Quast 5.0 [

39] and Busco 5.1.2 [

40]. Annotation was performed using the Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [

41].

2.7. Phylogenomic Analysis and Genome-Encoded Features

The genome-based phylogeny of strain D3K7 was determined based on the comparative analysis of 120 ubiquitous single-copy proteins using the Genome Taxonomy Database [

42] and GTDB-Toolkit v. 2.0. [

43]. The maximum likelihood genome-based tree was constructed using MegaX software [

44]. Genes of key metabolic pathways were manually verified using blastp searches [

45]. Pangenomic comparison of currently described

Methylocapsa species and

Methylocapsa-related MAGs was performed using the Roary package [

46]. The pool of examined genomes included those from strain D3K7,

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis USCa_MF, ‘

Methylocapsa gorogona’ MG08,

Methylocapsa aurea KYG

T,

Methylocapsa acidiphila B2

T,

Methylocapsa palsarum NE2

T, and the Canadian MAG AHI, which was phylogenetically most closely related to our new isolate. As a criterion for genes orthology, a threshold of 50% amino acid sequence identity was used.

2.8. Global Distribution Analysis

In order to assess the occurrence of strain D3K7-like bacteria in various environments, the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG/M) database of the Joint Genome Institute and the GeneBank database were screened for

pmoA sequences similar to that in strain D3K7 (sequence similarity ≥85%, 250 bp subject length match). The full-length 16S rRNA gene sequence from strain D3K7 was used to screen Short Read Archive (SRA) datasets with IMNGS platform [

47] using a minimum threshold of 99% identity and a minimum size of 200 nucleotides. The longitude, latitude and habitat descriptions of resulted hits were extracted and locations mapped in R with mollweide projection (packages: maps, mapdata, maptools, mapproj).

2.9. Sequence Accession Numbers

The raw data generated from 16S rRNA gene sequencing were deposited in Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number BioProject PRJNA1026465. The genome sequence of strain D3K7 has been deposited in NCBI GenBank under the accession number CP123229.1.

3. Results

3.1. Prokaryote Diversity and Methanotrophic Bacteria Identified in a Subarctic Soil

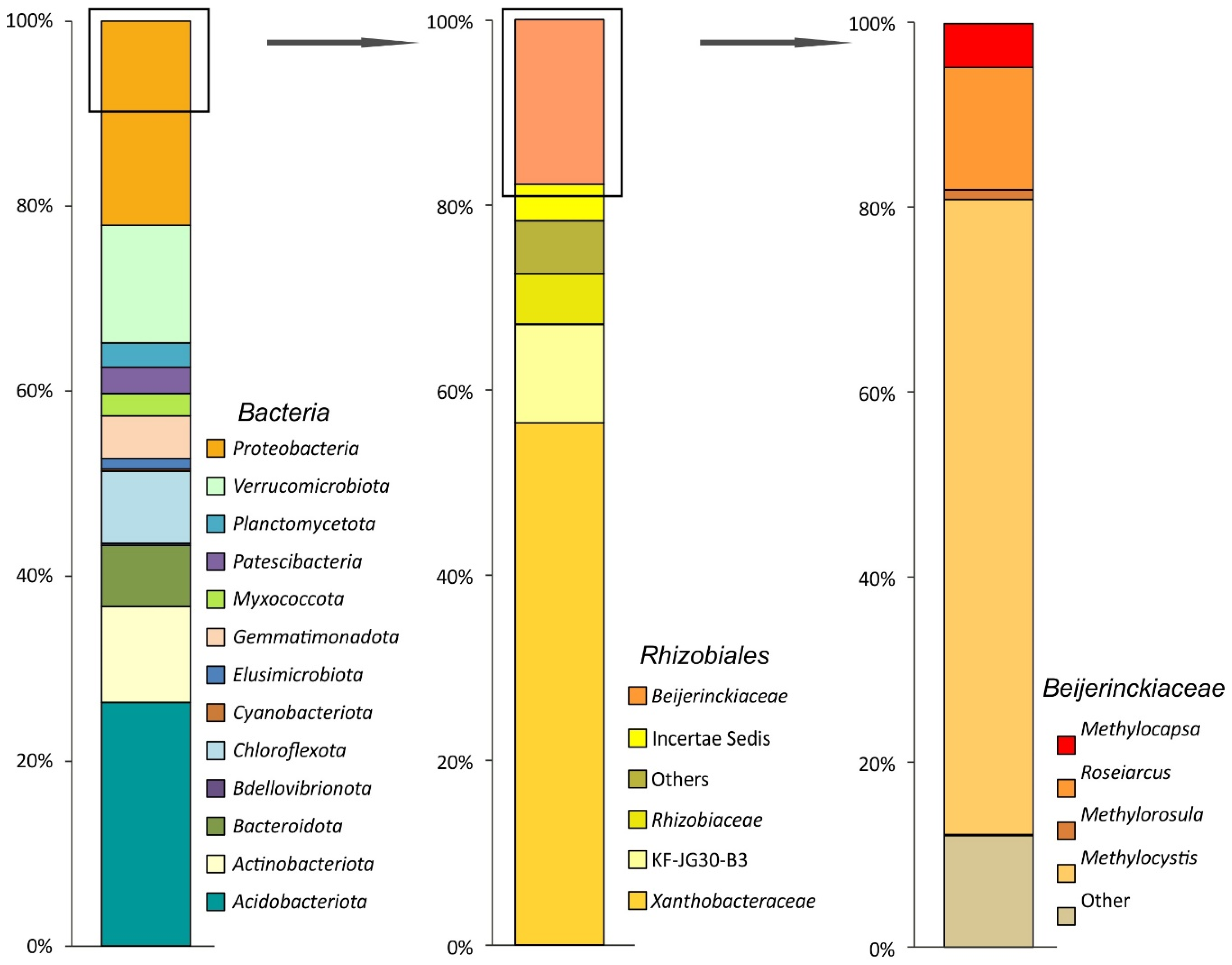

A total of 166,098 partial 16S rRNA gene sequences (mean amplicon length 253 bp) were retrieved from the examined subarctic tundra soil. Of these, 124,821 reads were retained after quality filtering, denoising, and removing chimeras. The relative abundance of

Archaea-affiliated 16S rRNA gene fragments was low (≤ 0.3% of total reads). Predominant bacterial phyla identified in the examined soil samples were the

Acidobacteriota (25.8 ± 1.2% of the total number of 16S rRNA gene fragments, mean ± SE),

Proteobacteria (21.7 ± 2.1%),

Verrucomicrobiota (12.5 ± 1.3%),

Actinobacteriota (10.2 ± 3.0%),

Chloroflexota (7.6 ± 1.2%),

Bacteroidota (6.5 ± 1.2%), and

Gemmatimonadota (4.5 ± 0.8%) (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bacteria community composition in a subarctic soil according to the results of Illumina-based sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. The composition is displayed at the following taxonomic levels (from left to right): the phylum level, the alphaproteobacterial order Rhizobiales, and the family Beijerinckiaceae. The relative abundance values represent averages of three replicate data sets.

Figure 2.

Bacteria community composition in a subarctic soil according to the results of Illumina-based sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. The composition is displayed at the following taxonomic levels (from left to right): the phylum level, the alphaproteobacterial order Rhizobiales, and the family Beijerinckiaceae. The relative abundance values represent averages of three replicate data sets.

Minor bacterial groups (with relative abundance below 3%) included

Patescibacteria,

Planctomycetota,

Myxococcota,

Elusimicrobiota,

Cyanobacteriota, and

Bdellovibrionota. The pool of

Proteobacteria-affiliated 16S rRNA gene fragments was examined for the presence of sequences belonging to gammaproteobacterial (order

Methylococcales) and alphaproteobacterial (order

Rhizobiales) methanotrophs. No

Methylococcales-affiliated reads were retrieved from the examined soil. By contrast,

Rhizobiales-affiliated 16S rRNA gene fragments comprised nearly half of all proteobacterial reads (

Figure 2). The second largest family within the

Rhizobiales was

Beijerinckiaceae (21.3 ± 11.9% of all

Rhizobiales-related sequences). The latter was represented by methanotrophs of the genera

Methylocystis and

Methylocapsa, methylotrophs of the genus

Methylorosula, and phototrophs of the genus

Roseiarcus. The most abundant OTU among

Beijerinckiaceae was classified as representing moss-associated methanotroph

Methylocystis bryophila (67% of all

Beijerinckiaceae-affiliated reads) [

48].

Methylocapsa-related reads comprised 4.8% of all

Beijerinckiaceae-affiliated sequences.

3.2. Isolation and Identification of Strain D3K7

After 6 months of incubation under static conditions, the bottles with methane-oxidizing enrichment cultures inoculated with studied soil samples were subjected to microscopic examination. Microbial consortia that developed in all bottles were dominated by

Methylocystis- and

Methylocapsa-like cells, which were rod-like to reniform in shape and formed large cell aggregates. These cells varied in size from very small (0.8-1 µm) to those reported for most described

Methylocystis and

Methylocapsa species (1.5-3 µm). One enrichment culture, which was dominated with very small cells of

Methylocapsa-like morphology, was selected for further isolation efforts. Plating cell suspensions onto the surface of polycarbonate filters resulted in formation of several micro-colonies after 2 months of incubation with methane (

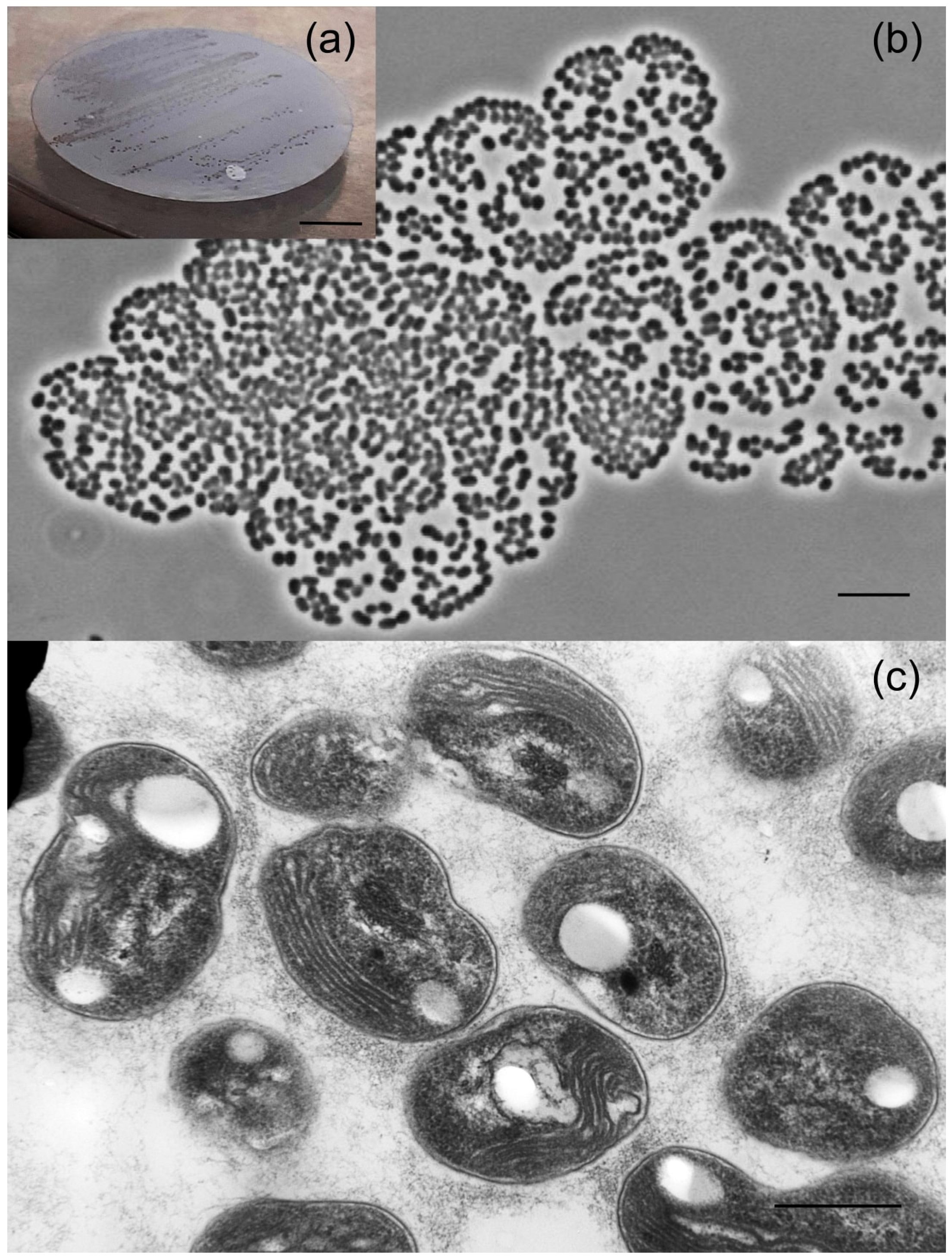

Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Colony formation and (b) cell morphology of strain D3K7 after 14 days of cultivation on polycarbonate filters in liquid medium M2 with ~30% (v/v) methane. Marker, 5 μm; (c) Electron micrograph of an ultrathin section of methane-grown cells of strain D3K7. Marker, 200 nm.

Figure 3.

(a) Colony formation and (b) cell morphology of strain D3K7 after 14 days of cultivation on polycarbonate filters in liquid medium M2 with ~30% (v/v) methane. Marker, 5 μm; (c) Electron micrograph of an ultrathin section of methane-grown cells of strain D3K7. Marker, 200 nm.

These colonies were composed of short thick rods or coccoids of irregular shape, which were assembled in large cell clusters containing up to several hundred cells (

Figure 3b). One of these micro-colonies was picked and used to inoculate 60-ml vial containing 10 ml of the liquid medium M2 and 10% methane in the headspace. The resulting culture was serially diluted in tenfold steps until the target bacterium was obtained in a pure culture and designated strain D3K7. Cells of strain D3K7 were Gram-negative, non-motile, encapsulated short rods or coccoids, 1.4±0.04 μm in length and 0.9±0.02 μm in width. Analysis of ultrathin cell sections revealed the presence of intracytoplasmic membranes located on one side of a cell (

Figure 3c) as characteristic for methanotrophs of the genus

Methylocapsa.

Comparative analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain D3K7 confirmed affiliation of this isolate with the genus Methylocapsa. The closest taxonomically characterized phylogenetic relatives of strain D3K7 were M. aurea KYGT and M. palsarum NE2T (98.6 and 98.4% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity, respectively). Strain D3K7 displayed 96.8% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to that of ‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 and 96.1% similarity to that of as-yet-uncultivated Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis.

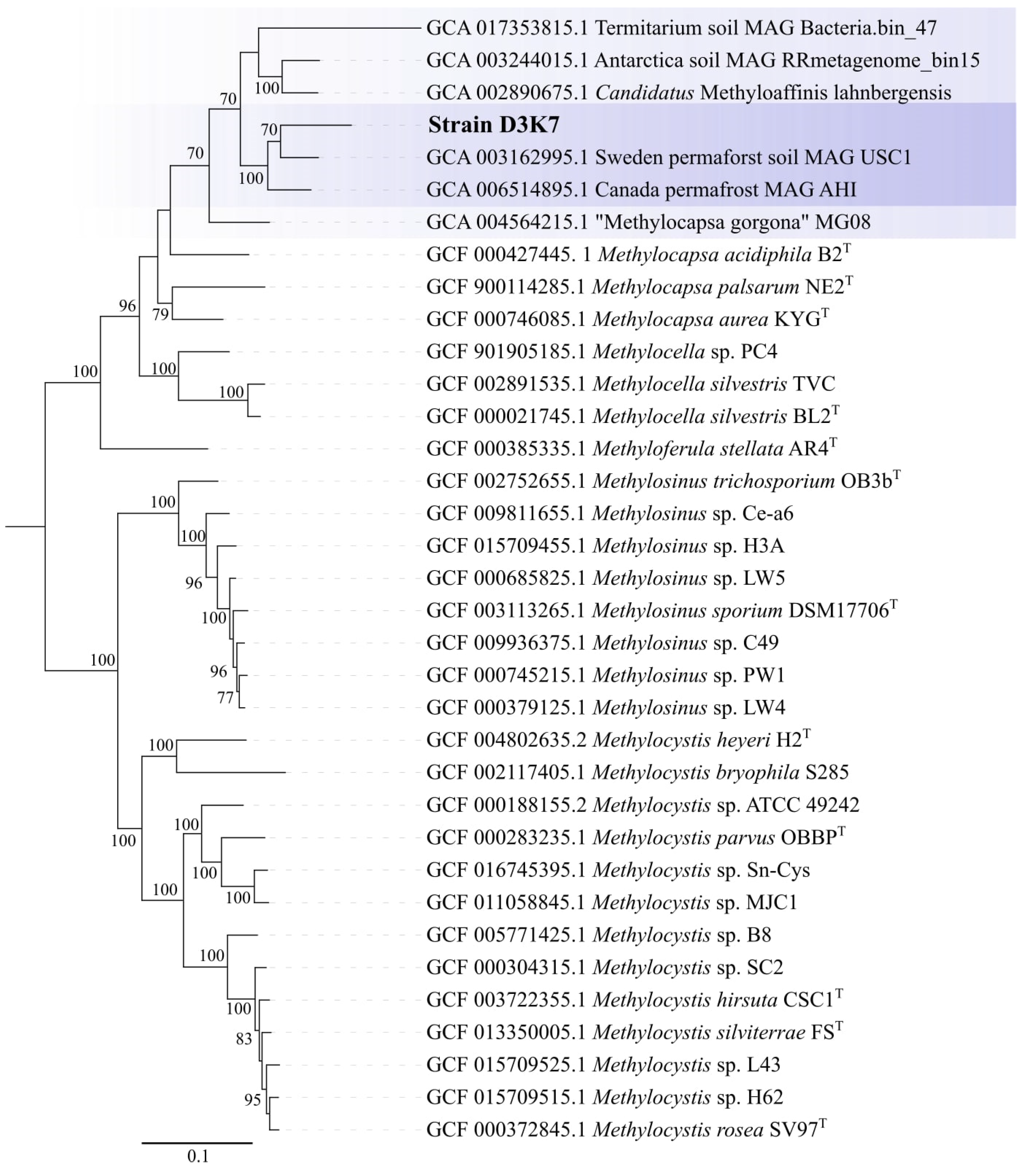

Since methanotroph affiliation with USCα group has long been defined by the PmoA phylogeny, the corresponding comparative analysis of PmoA sequence from strain D3K7 was performed as well (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic dendrogram constructed based on the results of the comparative analysis of

pmoA gene sequences from strain D3K7, other described species of the genus

Methylocapsa and some USCα representative

pmoA gene sequences. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura- Nei model [

51]. There were a total of 449 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X [

36]. Bootstrap values of > 50% are shown. The root (not shown) was composed of

pmoA gene sequences from five gammapteobacterial methanotrophs:

Methylohalobius crimeensis 10Ki

T (AJ581836),

Methylomonas methanica S1

T (U31653),

Methylomonas paludis MG30

T (HE801217),

Methylosoma difficile LC2

T (DQ119047), and

Methylovulum miyakonense HT12

T (AB501285). Bar, 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic dendrogram constructed based on the results of the comparative analysis of

pmoA gene sequences from strain D3K7, other described species of the genus

Methylocapsa and some USCα representative

pmoA gene sequences. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura- Nei model [

51]. There were a total of 449 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X [

36]. Bootstrap values of > 50% are shown. The root (not shown) was composed of

pmoA gene sequences from five gammapteobacterial methanotrophs:

Methylohalobius crimeensis 10Ki

T (AJ581836),

Methylomonas methanica S1

T (U31653),

Methylomonas paludis MG30

T (HE801217),

Methylosoma difficile LC2

T (DQ119047), and

Methylovulum miyakonense HT12

T (AB501285). Bar, 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position.

The latter revealed 69 – 71% identity to PmoA sequences from described Methylocapsa representatives with validly published names, i.e. M. acidiphila, M. palsarum, and M. aurea, while the sequence identity to PmoA from ‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 was 80%. The highest sequence identity of PmoA from strain D3K7, however, was observed with the corresponding protein sequences encoded in metagenomes obtained from subarctic and Antarctic ecosystems (up to 98%). The sequence identity with PmoA from Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis was 79%.

3.3. Growth characteristics

Like other members of the genus

Methylocapsa, strain D3K7 grew on methane as the sole carbon and energy source. Growth occurred in a relatively narrow pH range of 5.5 – 7.8 with the optimum at pH 6.6 – 7.0. The temperature range for growth was 5 – 30°C with the optimum at 20 – 25°C. The specific growth rate of strain D3K7 in a liquid culture under methane (10%, v/v) at 20 – 22 °C was 0.015 h

–1 (equivalent to a doubling time of 46.2 h). Maximal OD

600 of methane-grown cultures of strain D3K7, which was reached after 8 – 10 days of cultivation, was about 0.9. These growth characteristics are somewhat lower than those reported for earlier described

Methylocapsa species [

23,

34,

49]. Very poor, nearly undetectable growth was observed on methanol, which supported growth only when used at concentrations below 0.2% (v/v). Similar to

Methylocapsa acidiphila B2

T, strain D3K7 was able to fix dinitrogen and grew in nitrogen-free medium under fully aerobic conditions.

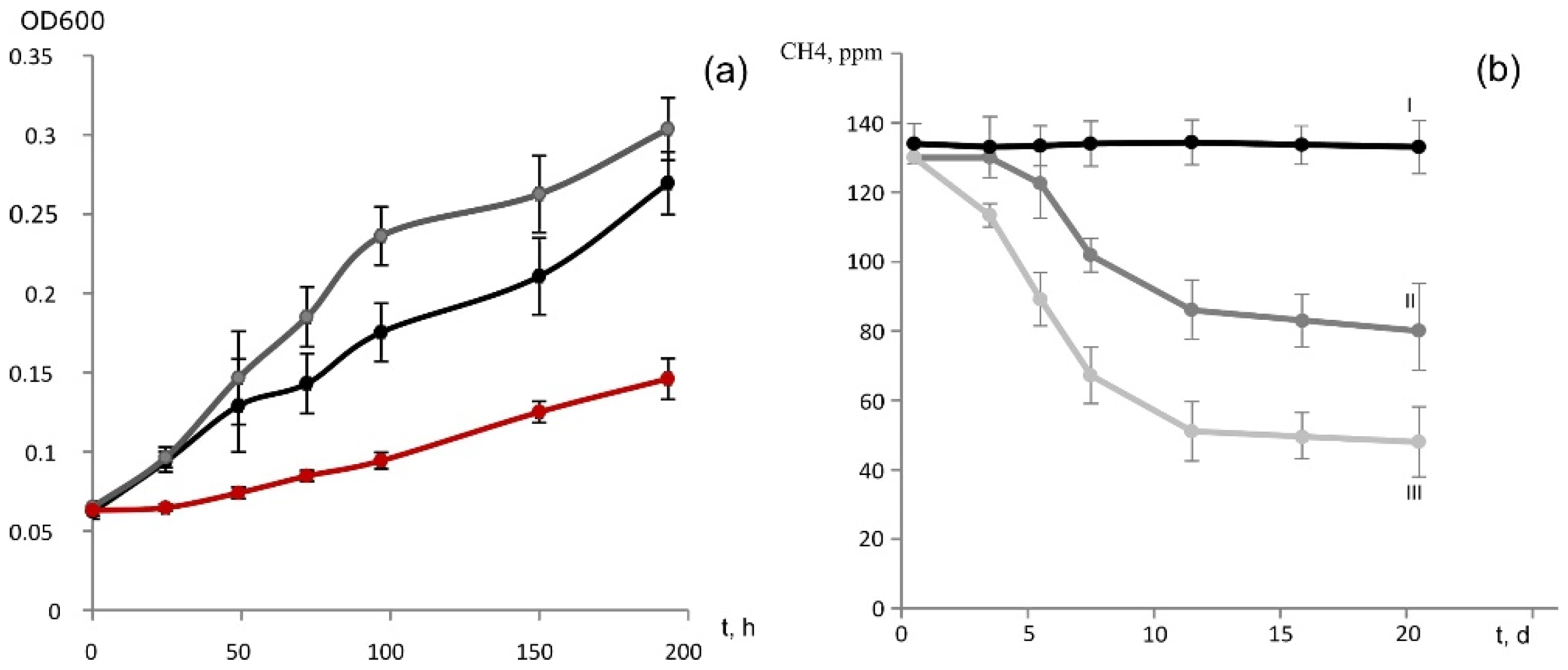

In addition to methane and methanol, strain D3K7 was capable of slow growth (specific growth rate 0.005 h

–1) on acetate (

Figure 5a). Maximal OD

600 of acetate-grown cultures of strain D3K7 was around 0.2. In the presence of two substrates, methane and acetate, the specific growth rate of this methanotroph increased to 0.017 h

–1.

Figure 5.

(a) Growth dynamics of strain D3K7 on methane (black), acetate (red) or in the presence of both methane and acetate (grey). (b) Dynamics of methane concentration in experimental flasks with liquid cultures of strain D3K7 supplied with methane (II) or both methane and acetate (III). Control vials (I) contain sterile liquid mineral medium. All data are means of triplicates.

Figure 5.

(a) Growth dynamics of strain D3K7 on methane (black), acetate (red) or in the presence of both methane and acetate (grey). (b) Dynamics of methane concentration in experimental flasks with liquid cultures of strain D3K7 supplied with methane (II) or both methane and acetate (III). Control vials (I) contain sterile liquid mineral medium. All data are means of triplicates.

No growth was observed on other tested carbon substrates (see Methods). Strain D3K7 was sensitive to NaCl: 0.3% (w/v) NaCl inhibited growth by 90% and 0.5% (w/v) NaCl inhibited growth completely.

3.4. Oxidation of CH4 provided in low concentrations

Strain D3K7 was examined for the ability to oxidize methane when the latter is present in low concentrations (below 100 p.p.m.v.). Two types of experimental incubations were used: (1) conventional liquid cultures of strain D3K7 and (2) bottles with adsorbent materials (perlite or vermiculite), which were inoculated with cell suspensions of strain D3K7. As seen in

Figure 5b, CH

4 concentration in experimental flasks declined faster if acetate was supplied to strain D3K7 in addition to methane.

Similar effect was observed for experimental bottles containing perlite or vermiculite, which were used to simulate mineral particles in a well-aerated soil. CH

4 consumption was faster when acetate was supplied as a second available substrate (

Figure 6). No decline of CH

4 concentration occurred in control bottles, which were not inoculated with cell suspensions of strain D3K7.

Figure 6.

Dynamics of methane concentration in experimental bottles with adsorbent materials perlite (a) or vermiculite (b), which were used to simulate mineral particles in a well-aerated soil. Incubations were supplied with methane (II) or both methane and acetate (III). Control bottles (I) were supplied with methane but were not inoculated with cells of strain D3K7. All data are means of triplicates.

Figure 6.

Dynamics of methane concentration in experimental bottles with adsorbent materials perlite (a) or vermiculite (b), which were used to simulate mineral particles in a well-aerated soil. Incubations were supplied with methane (II) or both methane and acetate (III). Control bottles (I) were supplied with methane but were not inoculated with cells of strain D3K7. All data are means of triplicates.

3.5. Genome Sequencing and Phylogenomic Placement

The final hybrid genome assembly for strain D3K7 consisted of one circular chromosome with a total length of 4,607,683 bp. No plasmids were detected. The genome contained one rrn operon copy (16S-23S-5S rRNA), 49 tRNA genes, and 3,701 predicted protein-coding sequences. DNA G+C content in strain D3K7 was 58.0%, which was close to that in ‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 (58.9%) and lower than that in described Methylocapsa species with validly published names (61.3 – 61.8%).

The genome-based phylogeny of strain D3K7 was inferred using the comparative sequence analysis of 120 ubiquitous single-copy proteins (

Figure 7). According to the results of this analysis, our isolate formed a common lineage (bootstrap support of 100%) with metagenome-assembled genomes obtained from the active layer of a permafrost thaw gradient in Stordalen Mire, Abisco, Sweeden [

18] and the mineral cryosol at Axel Heiberg Island in the Canadian high Arctic [

11,

50]. This lineage belongs to a broad phylogenetic clade defined by

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis, a ‘true’ USCα methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest soil in Germany [

27] and an USCα-like methanotroph, ‘

Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 [

28]. Other two sequences in this clade were represented by the MAG from an Antarctic desert surface soil [

51] and the MAG obtained from termitarium soil in Australia (GenBank bioproject: PRJNA663662). Notably, strain D3K7 occupied a phylogenetic position in between

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnber- gensis and all currently characterized

Methylocapsa methanotrophs, including

‘M. gorgona’ MG08.

Figure 7.

Genome-based phylogeny of strain D3K7. The clade of phylogenetically related USCα and USCα-like methanotrophs. The tree was constructed using the Genome Taxonomy Database Toolkit v2.0.0 [

43]. The significance levels of interior branch points obtained in maximum-likelihood analysis were determined by bootstrap analysis (100 data re-samplings). Bootstrap values of > 70% are shown. The root is composed of the family

Methylocystaceae genomes (type II methanotrophs). Bar, 0.1 substitutions per amino acid position.

Figure 7.

Genome-based phylogeny of strain D3K7. The clade of phylogenetically related USCα and USCα-like methanotrophs. The tree was constructed using the Genome Taxonomy Database Toolkit v2.0.0 [

43]. The significance levels of interior branch points obtained in maximum-likelihood analysis were determined by bootstrap analysis (100 data re-samplings). Bootstrap values of > 70% are shown. The root is composed of the family

Methylocystaceae genomes (type II methanotrophs). Bar, 0.1 substitutions per amino acid position.

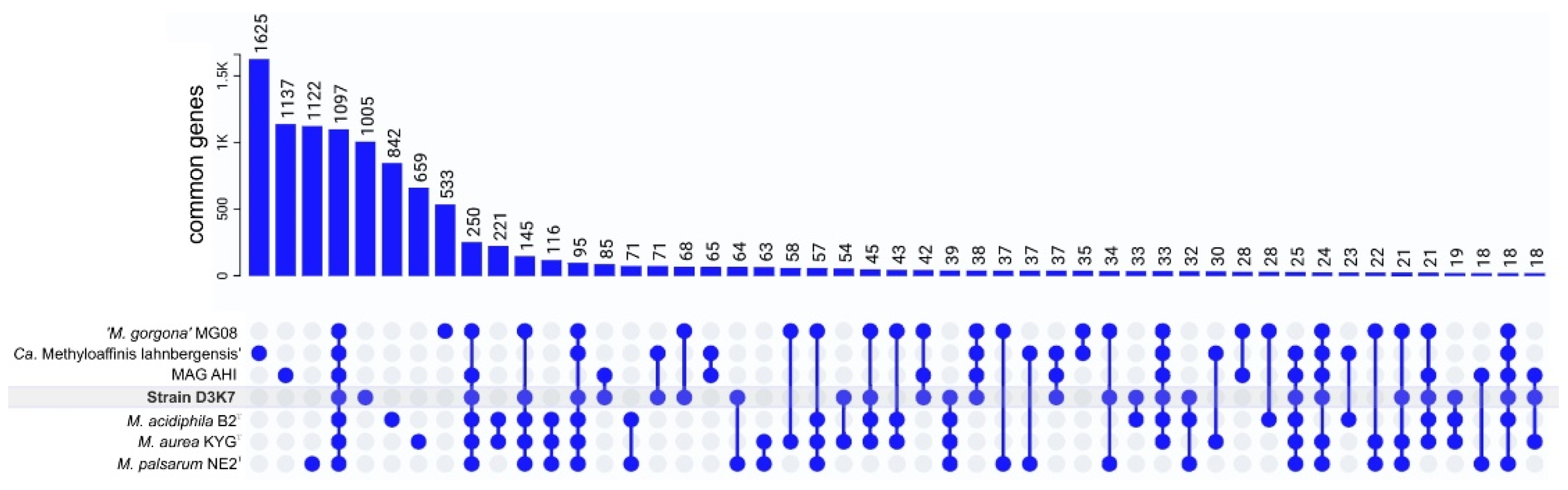

3.6. Pangenome Analysis, Shared and Unique Functional Characteristics

The genomes from strain D3K7,

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis USCa_MF,

‘Methylocapsa gorogona’ MG08,

Methylocapsa aurea KYG

T,

Methylocapsa acidiphila B2

T,

Methylocapsa palsarum NE2

T, and the Canadian MAG AHI were used for the pangenome analysis. The Roary-based approach clustered protein-coding sequences into core, shell, and cloud genomes. Of 10,779 gene clusters,

Methylocapsa-like methanotrophs pan-genome core comprised 1,097 genes (10.2% of total gene clusters), with the accessory genome containing 2,759 gene clusters (25.6% of total gene clusters) in the shell and 6,923 in the cloud (64.2% of total gene clusters) (

Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Distribution diagram of orthologous genes. Groups > 15 genes are shown. The level of amino acid sequence similarity >50% was used as a criterion for gene orthology.

Figure 8.

Distribution diagram of orthologous genes. Groups > 15 genes are shown. The level of amino acid sequence similarity >50% was used as a criterion for gene orthology.

All examined genomes contained a single

pmoCAB operon and from one to three orphan

pmoC genes. Soluble MMO was not encoded in the genomes of these methanotrophs. With the only exception of MAG USCa AHI, all examined genomes of

Methylocapsa-like methanotrophs contained a single

mxa operon encoding the classical methanol dehydrogenase and one-two copies of

xox gene clusters encoding the alternative lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenase. The absence of methanol dehydrogenase-encoding genes in MAG USCa AHI, most likely, is explained by its incompleteness. The

hpnD,

hpnC and

hpnE genes necessary for the synthesis of hopanoids were found in all examined genomes. Also, the fatty acid desaturase and sterol desaturase-encoding genes were found in all genomes of

Methylocapsa-like methanotrophs. As demonstrated in a recent study [

52], the cold-tolerant methanotroph

Methylovulum psychrotolerans increases synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids and hopanoids with a decrease in temperature. These results demonstrate that fatty acid and hopanoid composition can be remodeled to maintain bacterial membrane homeostasis upon cold adaptation. With the only exception of

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis USCa_MF, the genomes of all studied methanotrophs contained a complete set of

fli-genes necessary for the synthesis of flagella. Clusters of

nif genes encoding the Mo-Fe-nitrogenase complex were found in the genomes of all studied methanotrophs except

Candidatus Methyloaffinis lahnbergensis USCa_MF and MAG USCa AHI.

The genome of strain D3K7 was also inspected for the presence of genes that allow scavenging of trace gases, such as H

2 and CO. However, no high-affinity hydrogenases were revealed in strain D3K7. The only hydrogenase identified was the hydrogenase-4, which was shown to be responsible for H

2 production at low pH upon formate supplementation [

53]. Similarly, no gene candidates for carbon monoxide dehydrogenases were found in the genome of strain D3K7. The Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle was incomplete since no genes encoding forms I, II, and III of RuBisCo, which catalyzes the incorporation of inorganic carbon into 3-phosphoglyceric acid [

54], was revealed in the genome of strain D3K7. Instead, the genome contained gene for the RuBisCo-like protein (form IV RuBisCo) that does not catalyze CO

2 fixation [

55]. This protein was demonstrated to use 5-methylthioribulose-1-phosphate as a substrate, resulting in the formation of two products, i.e., 1-thiomethyl-D-xylulose-5-phosphate and 1-thiomethyl-D-ribulose-5-phosphate [

56]. The reaction catalyzed by this RLP was suggested to be involved in a new pathway for sulfur salvage. Notably, the genomes of other earlier described

Methylocapsa species, i.e.

M. acidiphila,

M. aurea, and

M. palsarum, encode form Ic RuBisCo as well as form IV RuBisCo. The presence of solely form IV RuBisCo is a distinctive characteristic found only in strain D3K7 and

‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08.

Similar to

‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 [

28], strain D3K7 harbors the complete set of genes for reductive glycine pathway (rGlyP), enabling the conversion of CO

2 and formate into glycine. Thus, genome-encoded traits related to metabolism of trace gases in strain D3K7 were limited to methane oxidation via pMMO and CO

2 fixation via rGlyP.

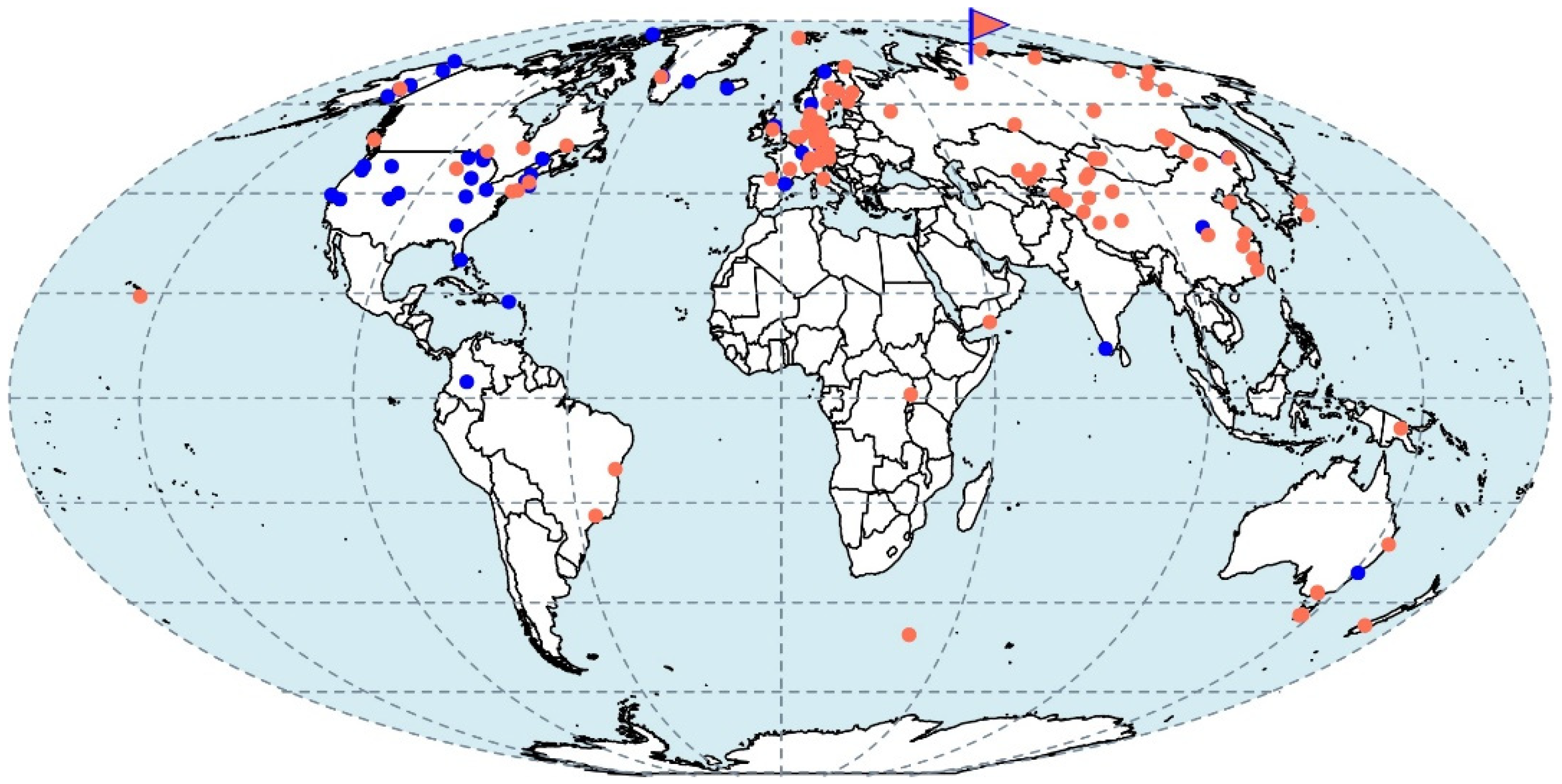

3.7. Biogeography of Strain D3K7-like Methanotrophs

IMG database searches for

pmoA gene sequences related to that of strain D3K7 yielded 1040 matches with >85% identity which corresponds to 42 locations (

Figure 9). These sequences originated from broad range of terrestrial habitats, including various types of peats and soils (forest, grassland, floodplain, bulk). Genbank database added 8 hits for the same search parameters set for

pmoA genes. These matches also affiliated with wetland and glacier soils (

Figure 7). SRA database searches for 16S rRNA genes related to strain D3K7 generated 561 hits with >99% identity threshold. These correspond to 95 locations (

Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Global distribution of the D3K7-related lineage. The map indicates sampling locations of IMG and Genbank databases hits for pmoA genes with >85% identity (blue dots) and Genbank SRA database hits for 16S rRNA genes with >98% identity (coral dots). Strain D3K7 sampling location is indicated with a flag.

Figure 9.

Global distribution of the D3K7-related lineage. The map indicates sampling locations of IMG and Genbank databases hits for pmoA genes with >85% identity (blue dots) and Genbank SRA database hits for 16S rRNA genes with >98% identity (coral dots). Strain D3K7 sampling location is indicated with a flag.

4. Discussion

According to the PmoA-based phylogeny and to the results of comparative genome analysis, our new isolate from a subarctic soil, strain D3K7, occupies an intermediate position between all so far described representatives of the genus

Methylocapsa and members of the USCα group, which elude all cultivation efforts. Isolation of this bacterium, therefore, takes us one step closer to the enigmatic methanotroph group. Notably, strain D3K7 forms a common clade with metagenome-assembled genomes obtained from the active layer of a permafrost thaw gradient in Stordalen Mire, Abisco, Sweeden [

18], and the mineral cryosol at Axel Heiberg Island in the Canadian high Arctic [

11], which were earlier addressed as belonging to USCα methanotrophs. As we see now, this is not fully correct. This phylogenetic clade should rather be addressed as a group of USCα-related methanotrophs that appear to be common in polar terrestrial ecosystems. Our biogeography analysis, however, suggests that these bacteria are not restricted to polar habitats but inhabit peatlands and soils of various climatic zones (see

Figure 9).

Apparently, patience was the main secret behind our success in isolating this novel methanotroph. The enrichment procedure continued for six months, gas phase: liquid phase ratio in cultivation bottles was extended to 9:1, and the bottles were incubated horizontally, under static conditions. The fact that soil extract was added in the cultivation medium, most likely, did not play a role since the isolate did not require any specific growth factors and was able to grow in a common mineral medium used for

Methylocapsa-like methanotrophs. Cells of strain D3K7 were smaller and the specific growth rate was lower than those in earlier described

Methylocapsa species. Yet, this novel isolate displayed many

Methylocapsa-specific traits, such as psychrotolerance, sensitivity to NaCl, localization of ICM on one side of a cell only, absence of soluble MMO, ability to fix dinitrogen, and to develop at low CH

4 concentrations. The ability to utilize acetate in the presence and in the absence of methane is one of the key adaptations of strain D3K7 for survival in a habitat where only trace amounts of CH

4 are available. Notably, the ability to utilize acetate varies among described

Methylocapsa species. Thus,

M. acidiphila B2

T,

M. palsarum NE2

T and

‘M. gorgona’ MG08 do not grow on acetate, while

M. aurea KYG

T and strain D3K7 possess this ability. The latter was experimentally confirmed for environmental populations of USCα methanotrophs in an acidic forest soil by using stable-isotope probing of RNA and DNA to investigate the assimilation

13C-acetate [

57]. That study revealed incorporation of

13C-acetate into USCα

pmoA mRNA suggesting that the contribution of alternative carbon sources, such as acetate, to the metabolism of the atmospheric methane oxidizers might be substantial [

57]. Additional energy required for growth may be supplied from acetate utilization. As shown in our incubation experiments, oxidation of CH

4 provided in low concentrations (below 100 p.p.m.v.) by strain D3K7 was more intense in the presence of acetate.

The fact strain D3K7 is not capable of fixing CO2 via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle was somewhat surprising given that all cultivated representatives of the genus Methylocapsa (with the only exception of ‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08) possess form Ic RuBisCo. The functional role of RuBisCo-like enzyme (or form IV RuBisCo) in ‘Methylocapsa gorgona’ MG08 and strain D3K7, therefore, remains to be elucidated. The reductive glycine pathway appears to be the only metabolic route for CO2 fixation by these methanotrophs.

Although the reason behind “nonculturability” of USCα methanotrophs remains unclear, some hints for obtaining these bacteria in cultures are now available. Apparently, these methanotrophs can be enriched under static incubation conditions only. As follows from the study of Tveit and co-authors [

28] and this work, the use of membrane filters for obtaining target isolates from enrichment cultures is also the only so far reported successful approach. This suggests that cells of USCα methanotrophs should be exposed to air in order to develop in a normal way. The use of various adsorbent materials to simulate mineral particles in a well-aerated soil may also be considered as a potentially suitable approach. The latter, however, needs to be verified in a specialized, long-term study given the specific nature of these slow-growing atmospheric methane oxidizers.