Submitted:

11 October 2023

Posted:

12 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

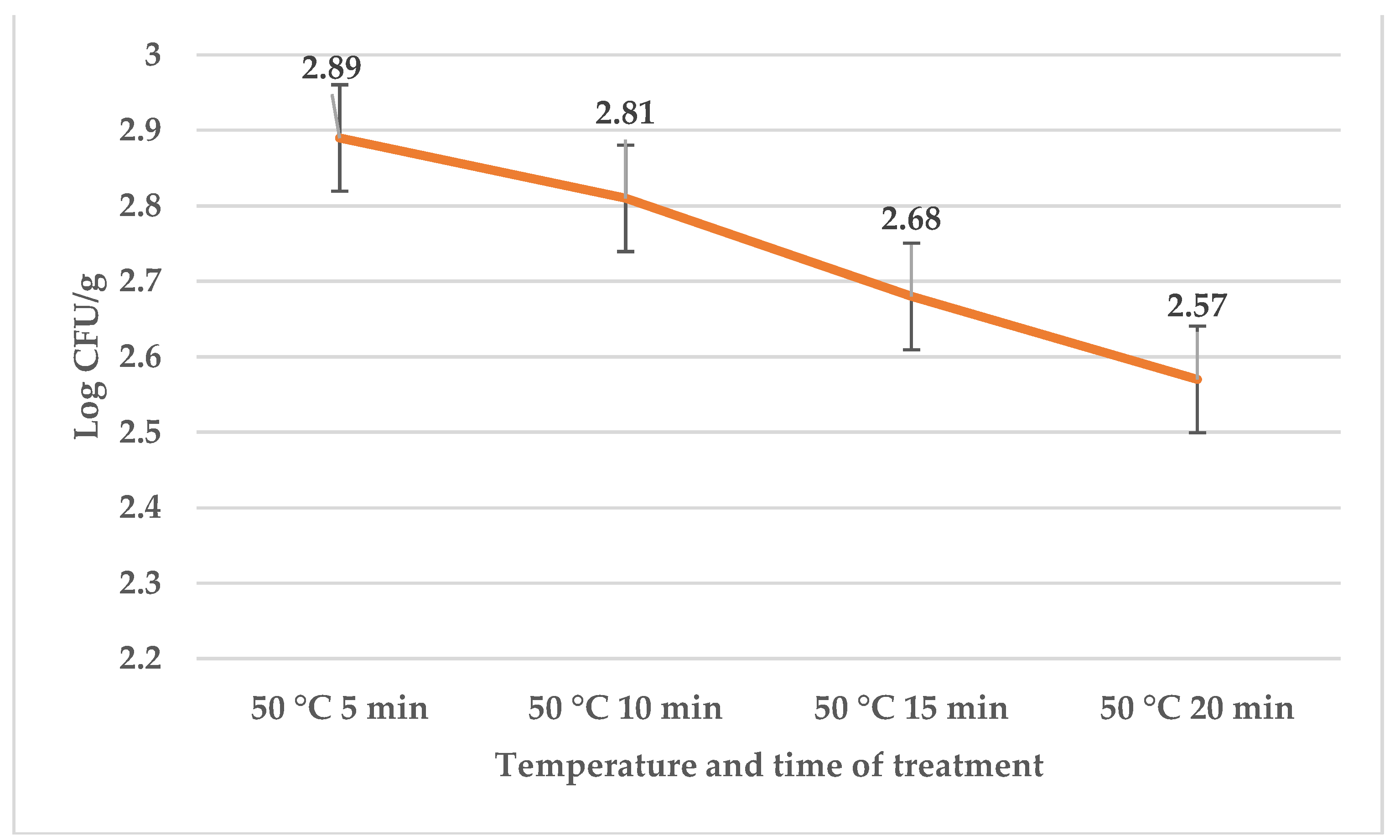

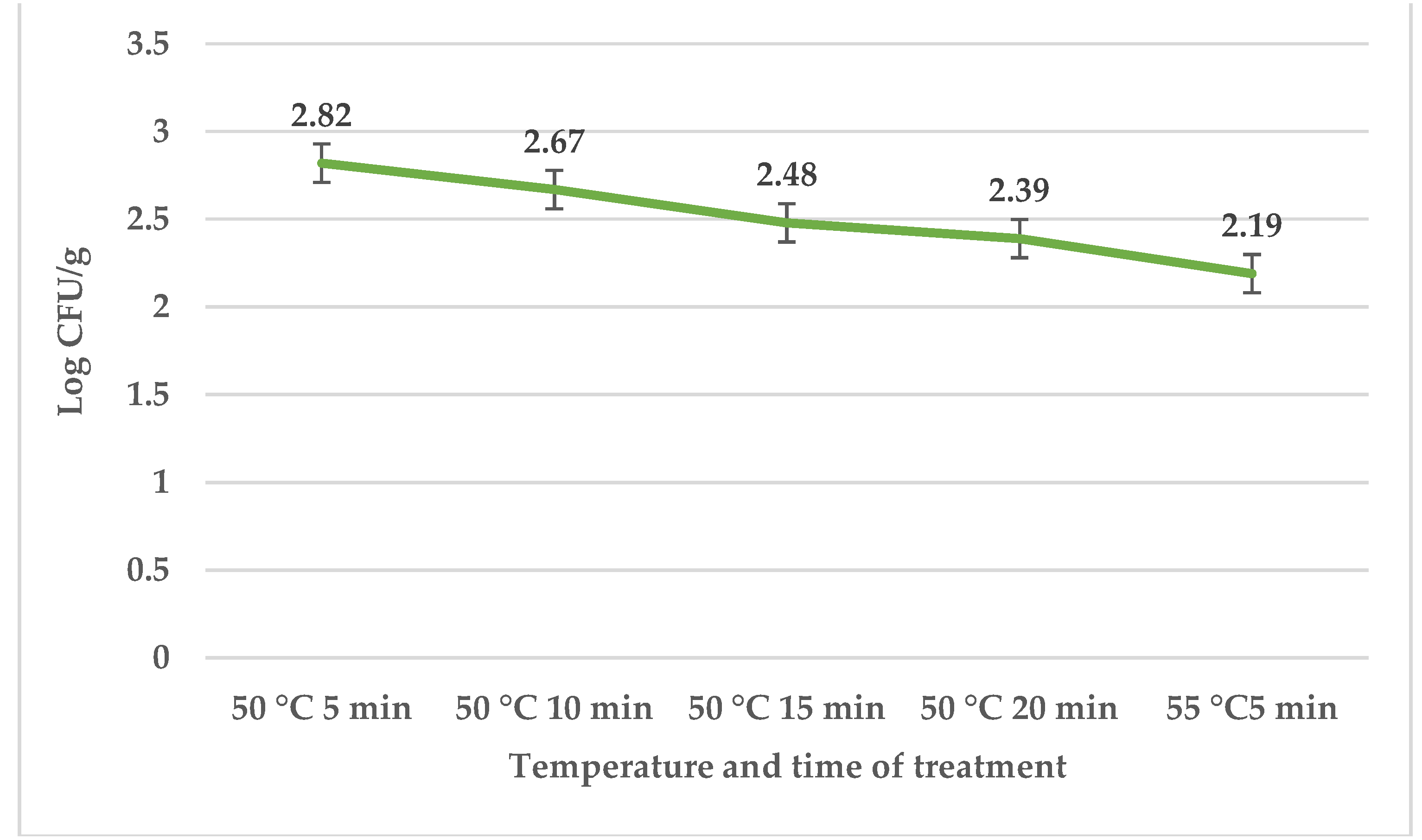

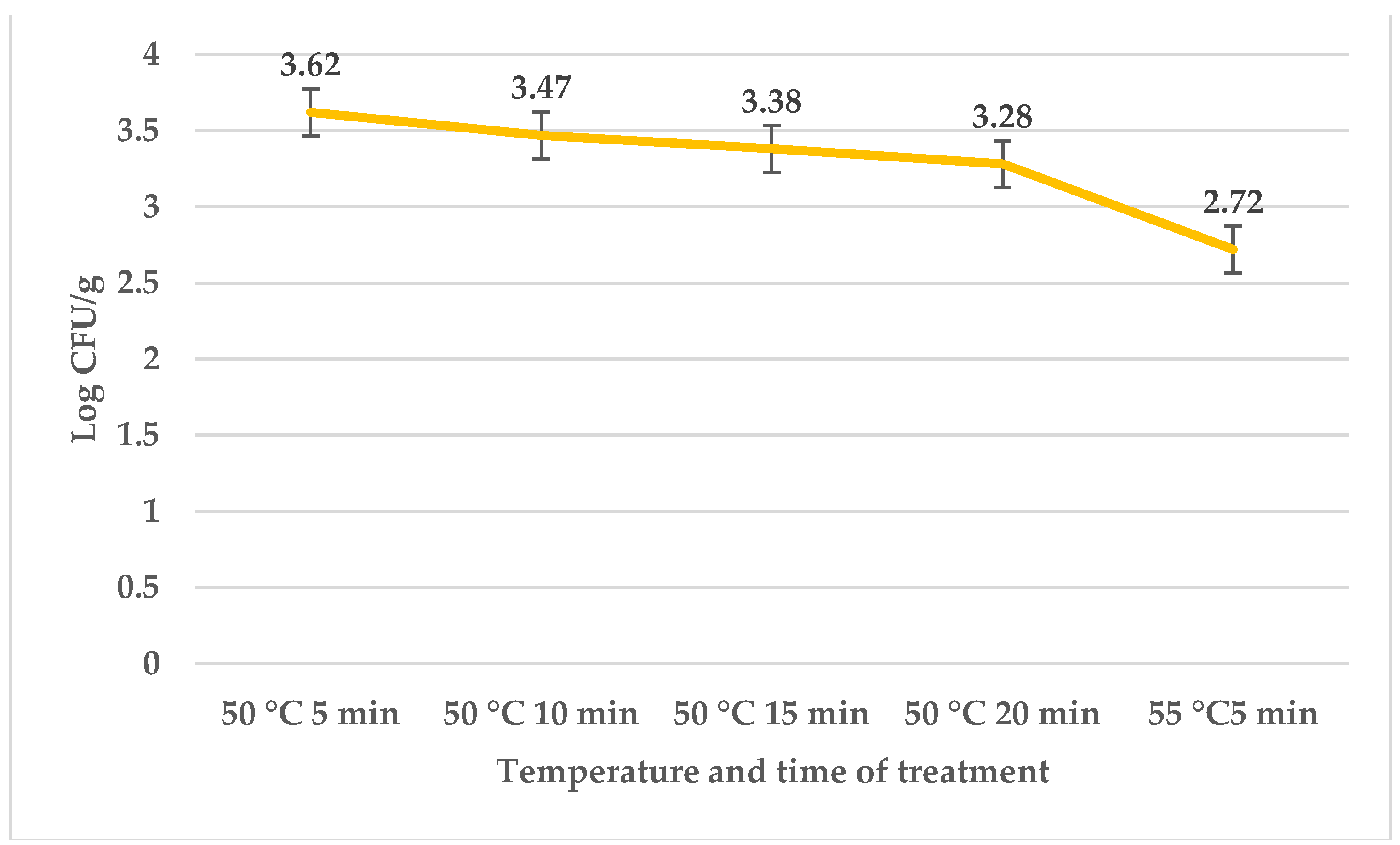

2.1. Number of Bacteria in Log CFU/g

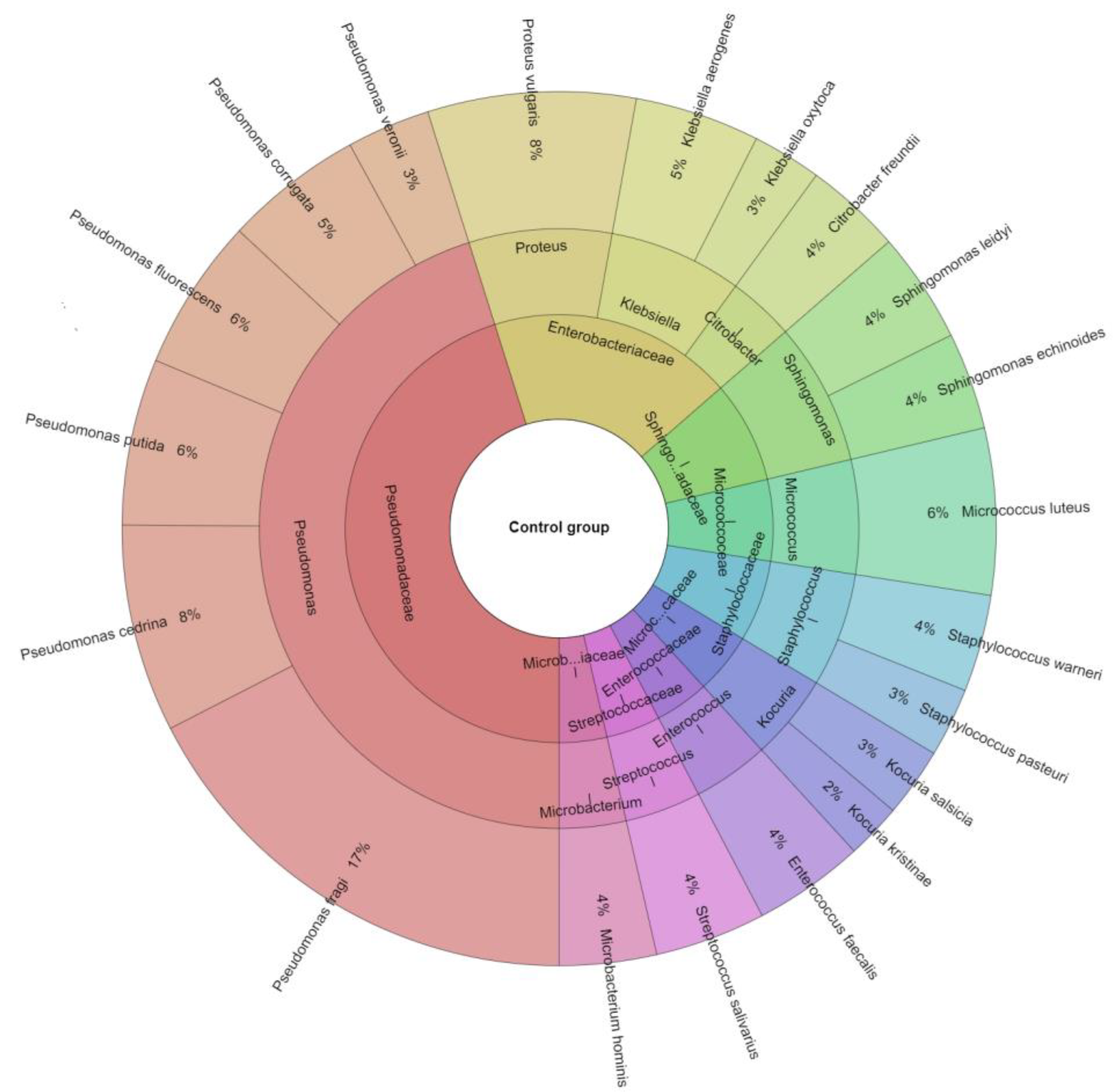

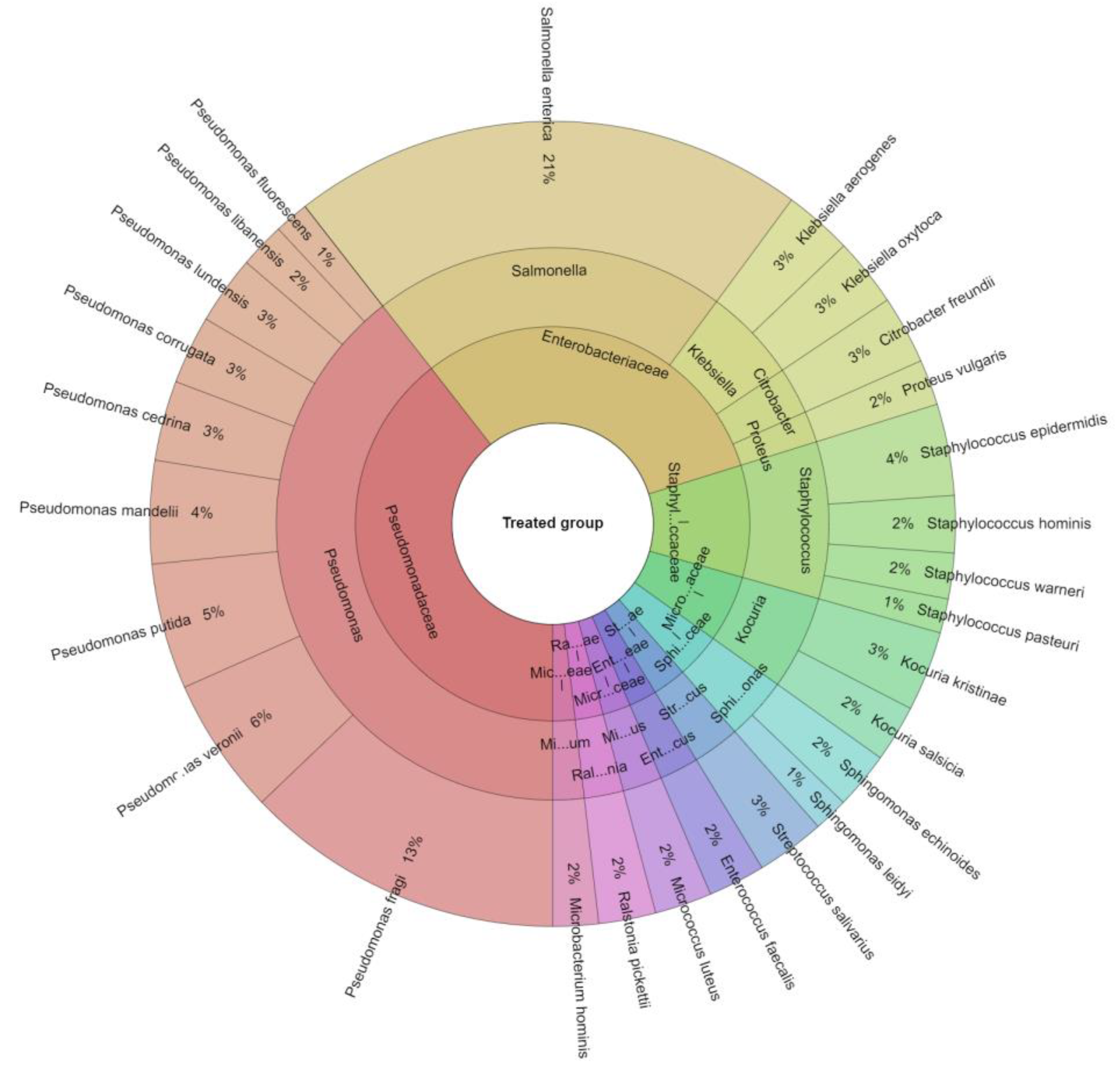

2.2. Isolated Bacteria from Beef Meat

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Inoculum Preparation

4.2. Essential Oil

4.3. Sample of Beef Meat preparation

4.4. Samples Cultivation

4.5. Identification of Bacteria with Mass Spectrometry

4.6. MALDI-TOF Matrix Solution Preparation

4.7. Identification of MICROORGANISMS

4.8. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldwin, D.E. Sous Vide Cooking: A Review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2012, 1, 15–30, doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2011.11.002. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.B.; Watson, S.C.; Chaves, B.D.; Sullivan, G.A. Inactivation of Salmonella in Nonintact Beef during Low-Temperature Sous Vide Cooking. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100010, doi:10.1016/j.jfp.2022.11.003. [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, J.R.; Duffy, G.; Koutsoumanis, K. Prevalence and Concentration of Verocytotoxigenic Escherichia Coli, Salmonella Enterica and Listeria Monocytogenes in the Beef Production Chain: A Review. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 357–376, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2008.10.012. [CrossRef]

- Kargiotou, C.; Katsanidis, E.; Rhoades, J.; Kontominas, M.; Koutsoumanis, K. Efficacies of Soy Sauce and Wine Base Marinades for Controlling Spoilage of Raw Beef. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 158–163, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2010.09.013. [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Labuza, T.P.; Diez-Gonzalez, F. Comparison of Primary Predictive Models to Study the Growth of Listeria Monocytogenes at Low Temperatures in Liquid Cultures and Selection of Fastest Growing Ribotypes in Meat and Turkey Product Slurries. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 460–470, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2008.01.009. [CrossRef]

- Berends, B.R.; Van Knapen, F.; Mossel, D.A.A.; Burt, S.A.; Snijders, J.M.A. Impact on Human Health of Salmonella Spp. on Pork in The Netherlands and the Anticipated Effects of Some Currently Proposed Control Strategies. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 44, 219–229, doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(98)00121-4. [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.L.; Nicol, C.; Cook, R.; Macdiarmid, S. Salmonella in Uncooked Retail Meats in New Zealand. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 1360–1365, doi:10.4315/0362-028X-70.6.1360. [CrossRef]

- Botteldoorn, N.; Heyndrickx, M.; Rijpens, N.; Grijspeerdt, K.; Herman, L. Salmonella on Pig Carcasses: Positive Pigs and Cross Contamination in the Slaughterhouse. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 891–903, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02042.x. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Thiel, S.; Ullrich And, U.; Stolle, A. Salmonella in Raw Meat and By-Products from Pork and Beef. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 1780–1784, doi:10.4315/0362-028X-73.10.1780. [CrossRef]

- Lebelo, K.; Malebo, N.; Mochane, M.J.; Masinde, M. Chemical Contamination Pathways and the Food Safety Implications along the Various Stages of Food Production: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 5795, doi:10.3390/ijerph18115795. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M.; Taylor, T.M.; Schmidt, S.E. Chemical Preservatives and Natural Antimicrobial Compounds. In Food Microbiology; Doyle, M.P., Buchanan, R.L., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 765–801 ISBN 978-1-68367-058-2.

- Himanshu; Lanjouw, P.; Stern, N. How Lives Change; Oxford University Press, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-880650-9.

- Skandamis, P.; Tsigarida, E.; Nychas, G.-J.E. The Effect of Oregano Essential Oil on Survival/Death of Salmonella Typhimurium in Meat Stored at 5°C under Aerobic, VP/MAP Conditions. Food Microbiol. 2002, 19, 97–103, doi:10.1006/fmic.2001.0447. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Zucca, P.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Pezzani, R.; Rajabi, S.; Setzer, W.N.; Varoni, E.M.; Iriti, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Phytotherapeutics in Cancer Invasion and Metastasis: Phytotherapeutics in Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1425–1449, doi:10.1002/ptr.6087. [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N. Ethnobotanical and Ethnopharmacological Study of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Used in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders in the Moroccan Rif. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 8, doi:10.30564/jim.v8i1.571. [CrossRef]

- Snow Setzer, M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Setzer, W. The Search for Herbal Antibiotics: An In-Silico Investigation of Antibacterial Phytochemicals. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 30, doi:10.3390/antibiotics5030030. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, G.; Mirzaei, M.; Mehrabi, R.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activities of Alstonia Scholaris, Alstonia Venenata and Moringa Oleifera Plants From India. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2016, 11, doi:10.17795/jjnpp-31129. [CrossRef]

- Nikoli, B.; Miti-ulafi, D.; Vukovi-Gai, B.; Kneevi-Vukevi, J. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Antimutagens from Sage (Salvia Officinalis) and Basil (Ocimum Basilicum). In Mutagenesis; Mishra, R., Ed.; InTech, 2012 ISBN 978-953-51-0707-1.

- Marino, M.; Bersani, C.; Comi, G. Impedance Measurements to Study the Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils from Lamiaceae and Compositae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 67, 187–195, doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00447-0. [CrossRef]

- Hayouni, E.A.; Chraief, I.; Abedrabba, M.; Bouix, M.; Leveau, J.-Y.; Mohammed, H.; Hamdi, M. Tunisian Salvia Officinalis L. and Schinus Molle L. Essential Oils: Their Chemical Compositions and Their Preservative Effects against Salmonella Inoculated in Minced Beef Meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 242–251, doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.04.005. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.F. Emergence, Spread, and Environmental Effect of Antimicrobial Resistance: How Use of an Antimicrobial Anywhere Can Increase Resistance to Any Antimicrobial Anywhere Else. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, S78–S84, doi:10.1086/340244. [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, A.J. Cultivation and Breeding. In: Kintzios, S.E. (Ed.), The Cultivation of Sage. Sage; 14th ed.; Taylor & Francis e-Library: Amsterdam, 2000.

- Sensoy, N.D. Obtaining of Natural Antioxidant from Sage Leaves (Salvia Officinalis) with Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction (M. Sc. Thesis).; Gazi University, Institute of Science and Technology: Ankara, 2007.

- Mohammad, S.M. A Study on Sage (Salvia Officinalis). J. Appl. Sci Res. 2011, 7, 1261–1262.

- Karyotis, D.; Skandamis, P.N.; Juneja, V.K. Thermal Inactivation of Listeria Monocytogenes and Salmonella Spp. in Sous-Vide Processed Marinated Chicken Breast. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 894–898, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.078. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Bari, M.L.; Inatsu, Y.; Kawamoto, S.; Friedman, M. Thermal Destruction of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in Sous-Vide Cooked Ground Beef as Affected by Tea Leaf and Apple Skin Powders. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 860–865, doi:10.4315/0362-028X-72.4.860. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Osoria, M.; Tiwari, U.; Xu, X.; Golden, C.E.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Mishra, A. The Effect of Lauric Arginate on the Thermal Inactivation of Starved Listeria Monocytogenes in Sous-Vide Cooked Ground Beef. Food Res. Int. 2020, 134, 109280, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109280. [CrossRef]

- Kačániová, M.; Galovičová, L.; Valková, V.; Ďuranová, H.; Borotová, P.; Štefániková, J.; Vukovic, N.L.; Vukic, M.; Kunová, S.; Felsöciová, S.; et al. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Salvia Officinalis Essential Oil. Acta Hortic. Regiotect. 2021, 24, 81–88, doi:10.2478/ahr-2021-0028. [CrossRef]

- Abel, T.; Boulaaba, A.; Lis, K.; Abdulmawjood, A.; Plötz, M.; Becker, A. Inactivation of Listeria Monocytogenes in Game Meat Applying Sous Vide Cooking Conditions. Meat Sci. 2020, 167, 108164, doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108164. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Olszewska, M.A.; Diez-Gonzalez, F. Selection and Application of Natural Antimicrobials to Control Clostridium Perfringens in Sous-Vide Chicken Breasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 347, 109193, doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109193. [CrossRef]

- Nissen, H.; Rosnes, J.T.; Brendehaug, J.; Kleiberg, G.H. Safety Evaluation of Sous Vide-Processed Ready Meals. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 35, 433–438, doi:10.1046/j.1472-765X.2002.01218.x. [CrossRef]

- Hyytiä-Trees, E.; Skyttä, E.; Mokkila, M.; Kinnunen, A.; Lindström, M.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Ahvenainen, R.; Korkeala, H. Safety Evaluation of Sous Vide-Processed Products with Respect to Nonproteolytic Clostridium Botulinum by Use of Challenge Studies and Predictive Microbiological Models. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 223–229, doi:10.1128/AEM.66.1.223-229.2000. [CrossRef]

- Cosansu, S.; Juneja, V.K. Growth of Clostridium Perfringens in Sous Vide Cooked Ground Beef with Added Grape Seed Extract. Meat Sci. 2018, 143, 252–256, doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.05.013. [CrossRef]

- Lindström, M.; Mokkila, M.; Skyttä, E.; Hyytiä-Trees, E.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Hielm, S.; Ahvenainen, R.; Korkeala, H. Inhibition of Growth of Nonproteolytic Clostridium Botulinum Type B in Sous Vide Cooked Meat Products Is Achieved by Using Thermal Processing but Not Nisin. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64, 838–844, doi:10.4315/0362-028X-64.6.838. [CrossRef]

- Šojić, B.; Pavlić, B.; Zeković, Z.; Tomović, V.; Ikonić, P.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Džinić, N. The Effect of Essential Oil and Extract from Sage (Salvia Officinalis L.) Herbal Dust (Food Industry by-Product) on the Oxidative and Microbiological Stability of Fresh Pork Sausages. LWT 2018, 89, 749–755, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2017.11.055. [CrossRef]

- Bor, T.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Gyawali, R.; Ibrahim, S.A. Antimicrobials from Herbs, Spices, and Plants. In Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 551–578 ISBN 978-0-12-802972-5.

- Gyawali, R.; Ibrahim, S.A. Natural Products as Antimicrobial Agents. Food Control 2014, 46, 412–429, doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.05.047. [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, R.; Hayek, S.A.; Ibrahim, S.A. Plant Extracts as Antimicrobials in Food Products. In Handbook of Natural Antimicrobials for Food Safety and Quality; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 31–47 ISBN 978-1-78242-034-7.

- Raeisi, S.; Ojagh, S.M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Quek, S.Y. Evaluation of Allium Paradoxum (M.B.) G. Don. and Eryngium Caucasicum Trauve. Extracts on the Shelf-Life and Quality of Silver Carp ( Hypophthalmichthys Molitrix ) Fillets during Refrigerated Storage: RAEISI et Al. J. Food Saf. 2017, 37, e12321, doi:10.1111/jfs.12321. [CrossRef]

- Raeisi, S.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Quek, S.Y.; Shabanpour, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Shallot (Allium Ascalonicum L.) Fruit and Ajwain (Trachyspermum Ammi (L.) Sprague) Seed Extracts in Semi-Fried Coated Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) Fillets for Shelf-Life Extension. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 112–121, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2015.07.064. [CrossRef]

- Longaray Delamare, A.P.; Moschen-Pistorello, I.T.; Artico, L.; Atti-Serafini, L.; Echeverrigaray, S. Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oils of Salvia Officinalis L. and Salvia Triloba L. Cultivated in South Brazil. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 603–608, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.09.078. [CrossRef]

- Dorman, H.J.D.; Deans, S.G. Antimicrobial Agents from Plants: Antibacterial Activity of Plant Volatile Oils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 308–316, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00969.x. [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, M.; Ahcen, B.; Rachid, D.; Hakim, H. Phytochemical Study and Biological Activity of Sage (Salvia Officinalis L.). Int. J. biol. Life Agric. Sci. 2015, 7.0, doi:10.5281/zenodo.1326832. [CrossRef]

- Miladinovic, D.; Lj, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil of Sage from Serbia. Facta Univ. - Ser. Phys. Chem. Technol. 2000, 2, 97–100, doi:.

- Gál, R.; Čmiková, N.; Prokopová, A.; Kačániová, M. Antilisterial and Antimicrobial Effect of Salvia Officinalis Essential Oil in Beef Sous-Vide Meat during Storage. Foods 2023, 12, 2201, doi:10.3390/foods12112201. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.K.; Gill, C.O.; Yang, X. Storage Life at 2 °C or −1.5 °C of Vacuum-Packaged Boneless and Bone-in Cuts from Decontaminated Beef Carcasses: Storage Life of Vacuum-Packaged Beef Primals from Decontaminated Carcasses. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 3118–3124, doi:10.1002/jsfa.6659. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.K.; Gill, C.O.; Tran, F.; Yang, X. Unusual Compositions of Microflora of Vacuum-Packaged Beef Primal Cuts of Very Long Storage Life. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 2161–2167, doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-190. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tran, F.; Wolters, T. Microbial Ecology of Decontaminated and Not Decontaminated Beef Carcasses. J. Food Res. 2017, 6, 85, doi:10.5539/jfr.v6n5p85. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, A.; Yang, X. Dynamics of Microflora on Conveyor Belts in a Beef Fabrication Facility during Sanitation. Food Control 2018, 85, 42–47, doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.09.017. [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Average | SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 50 | 5 | 3.76 | 0.08 | 4.114x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 5 | 3.27 | 0.12 | |

| BM | 50 | 10 | 3.63 | 0.17 | 2.110x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 10 | 2.90 | 0.06 | |

| BM | 50 | 15 | 3.35 | 0.09 | 3.302x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 15 | 2.72 | 0.04 | |

| BM | 50 | 20 | 3.35 | 0.05 | 3.219x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 20 | 2.58 | 0.05 | |

| BM | 55 | 5 | 3.28 | 0.05 | 1.814x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 5 | 2.47 | 0.05 | |

| BM | 55 | 10 | 3.16 | 0.02 | 1.315x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 10 | 2.22 | 0.05 | |

| BM | 55 | 15 | 3.08 | 0.04 | 1.230x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 15 | 2.15 | 0.03 | |

| BM | 55 | 20 | 2.94 | 0.05 | 8.874x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 20 | 1.94 | 0.05 | |

| BM | 60 | 5 | 2.68 | 0.07 | 5.179x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 60 | 5 | 1.68 | 0.07 | |

| BM | 60 | 10 | 2.62 | 0.04 | 2.366x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 60 | 10 | 1.62 | 0.04 | |

| BM | 60 | 15 | 2.35 | 0.06 | 1.631x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 60 | 15 | 1.35 | 0.06 | |

| BM | 60 | 20 | 2.17 | 0.03 | 7.026x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 60 | 20 | 1.17 | 0.03 | |

| BM | 65 | 10 | 2.03 | 0.006 | 1.527x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 65 | 10 | 1.02 | 0.02 |

| Treatment | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Average | SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 50 | 5 | 4.41 | 0.14 | 3.003x10-1* |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 5 | 4.52 | 0.06 | |

| BM | 50 | 10 | 4.36 | 0.05 | 4.214x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 10 | 4.45 | 0.03 | |

| BM | 50 | 15 | 4.28 | 0.04 | 3.377x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 15 | 4.40 | 0.06 | |

| BM | 50 | 20 | 4.17 | 0.04 | 2.279x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 20 | 4.44 | 0.12 | |

| BM | 55 | 5 | 4.08 | 0.03 | 5.406x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 5 | 4.31 | 0.02 | |

| BM | 55 | 10 | 3.95 | 0.03 | 1.253x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 10 | 2.50 | 0.17 | |

| BM | 55 | 15 | 3.79 | 0.12 | 1.413x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 15 | 2.16 | 0.01 | |

| BM | 55 | 20 | 3.63 | 0.06 | 7.191x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 20 | 2.08 | 0.03 |

| Treatment | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Average | SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 50 | 5 | 2.81 | 0.05 | 5.500x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 5 | 3.35 | 0.03 | |

| BM | 50 | 10 | 2.49 | 0.06 | 2.833x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 10 | 3.23 | 0.02 |

| Treatment | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Average | SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 50 | 5 | 5.20 | 0.04 | 2.519x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 5 | 4.70 | 0.06 | |

| BM | 50 | 10 | 5.08 | 0.01 | 1.213x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 10 | 4.59 | 0.06 | |

| BM | 50 | 15 | 4.93 | 0.06 | 5.822x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 15 | 4.57 | 0.03 | |

| BM | 50 | 20 | 4.83 | 0.04 | 1.144x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 20 | 4.54 | 0.11 | |

| BM | 55 | 5 | 4.72 | 0.04 | 3.776x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 5 | 4.42 | 0.03 | |

| BM | 55 | 10 | 4.52 | 0.06 | 1.357x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 10 | 3.55 | 0.10 | |

| BM | 55 | 15 | 4.36 | 0.04 | 1.004x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 15 | 3.25 | 0.12 | |

| BM | 55 | 20 | 4.24 | 0.06 | 5.148x10-3 |

| BMSEEO | 55 | 20 | 2.66 | 0.03 |

| Treatment | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Average | SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 50 | 5 | 2.90 | 0.07 | 4.896x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 5 | 3.47 | 0.07 | |

| BM | 50 | 10 | 2.67 | 0.10 | 3.394x10-4 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 10 | 3.37 | 0.05 | |

| BM | 50 | 15 | 2.37 | 0.05 | 1.369x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 15 | 3.28 | 0.04 | |

| BM | 50 | 20 | 2.19 | 0.02 | 1.707x10-2 |

| BMSEEO | 50 | 20 | 3.22 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).