Submitted:

11 October 2023

Posted:

13 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

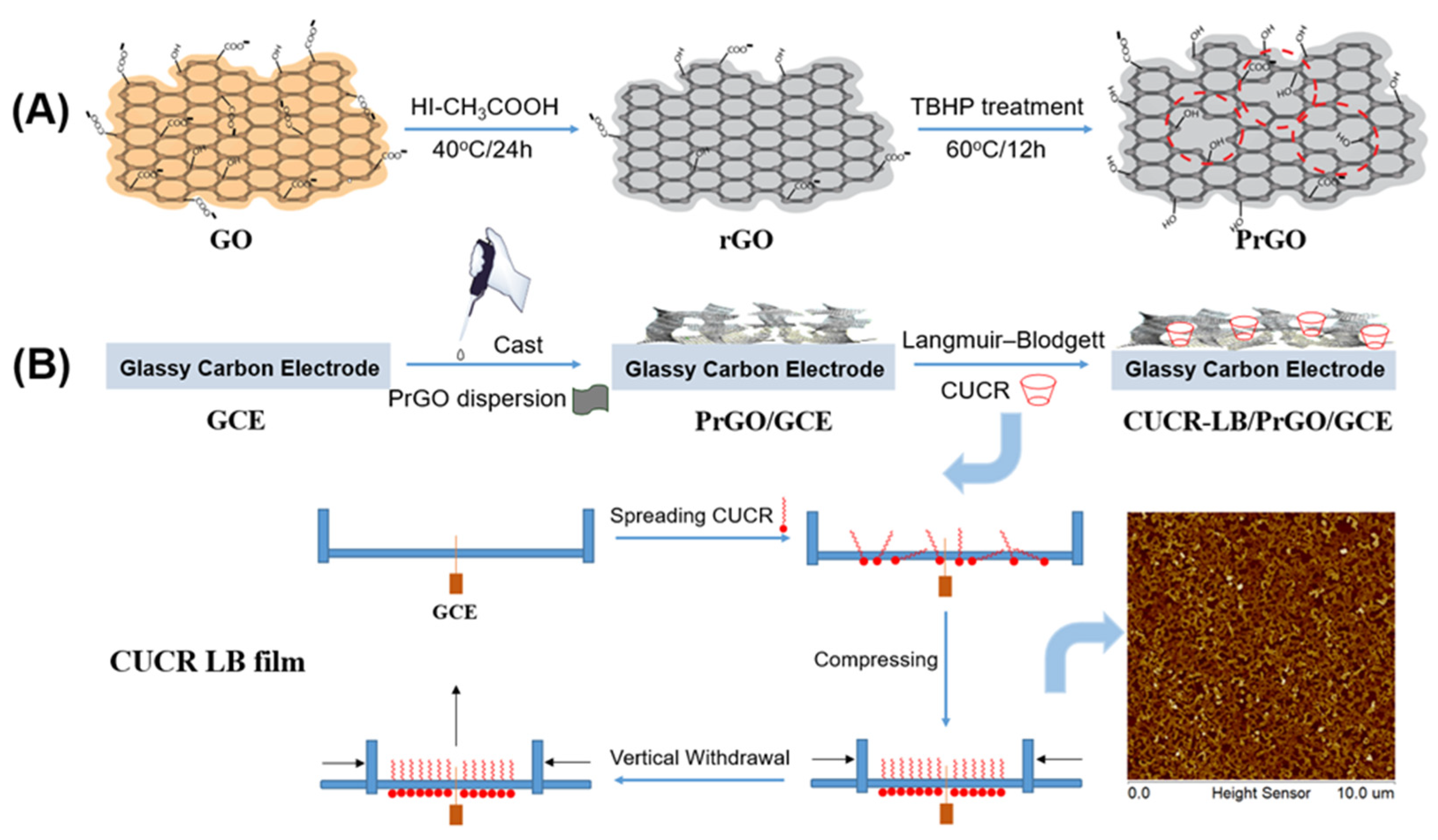

2.2. Preparation of porous reduced graphene oxide

2.3. Fabrication of the composite film modified electrode

3. Results and Discussion

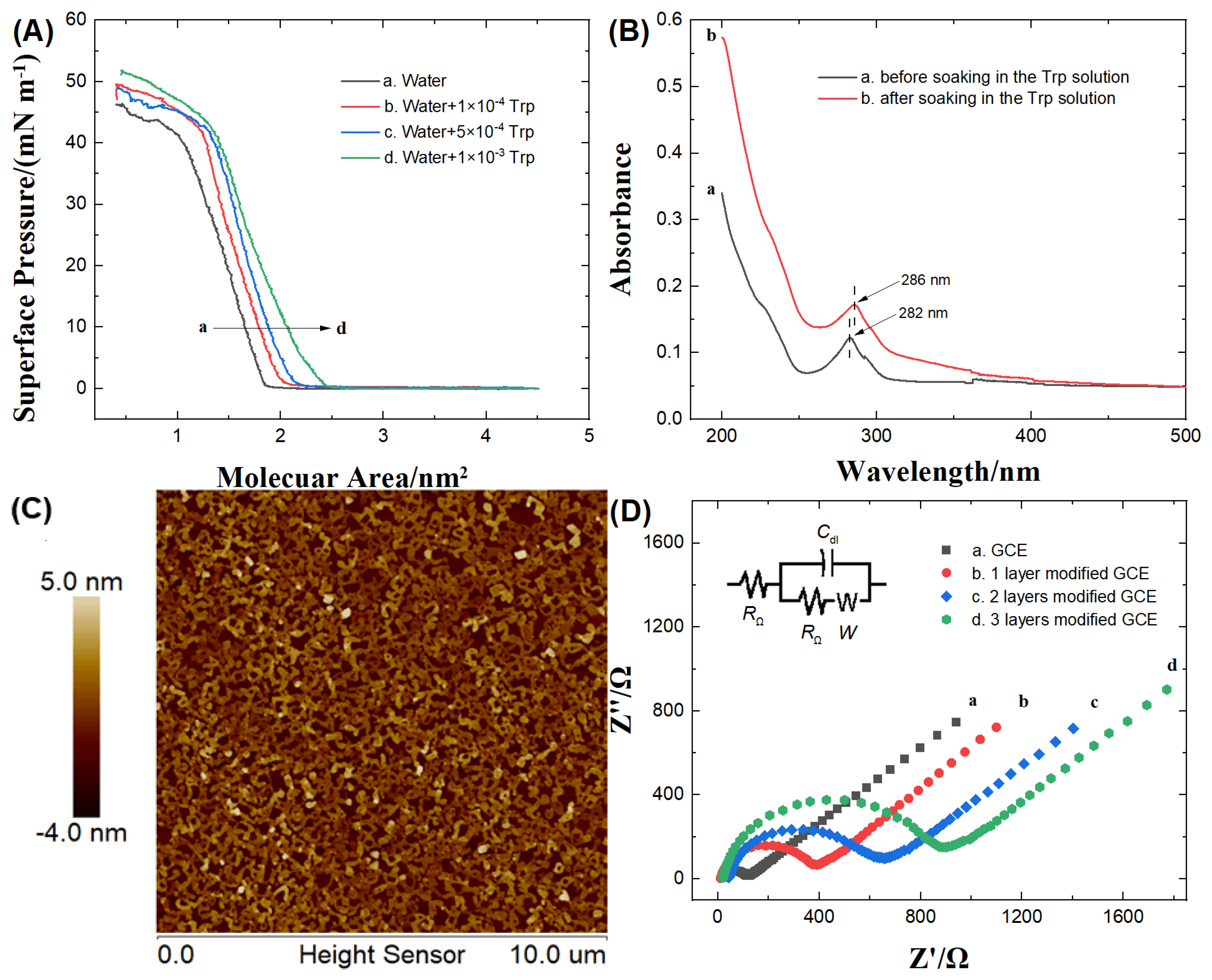

3.1. Characteristics of CUCR-LB film

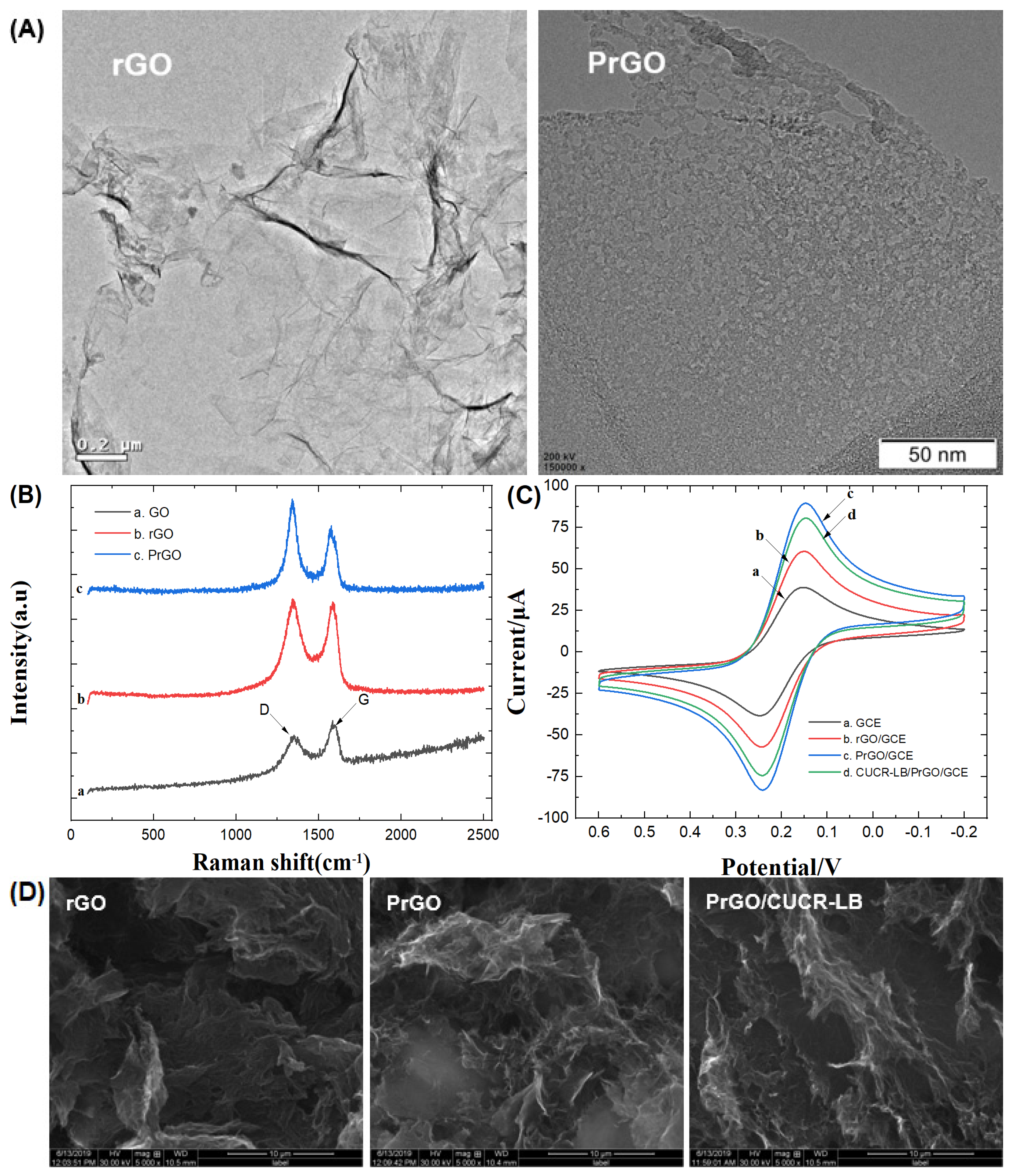

3.2. Characteristics of CUCR-LB/PrGO/GCE

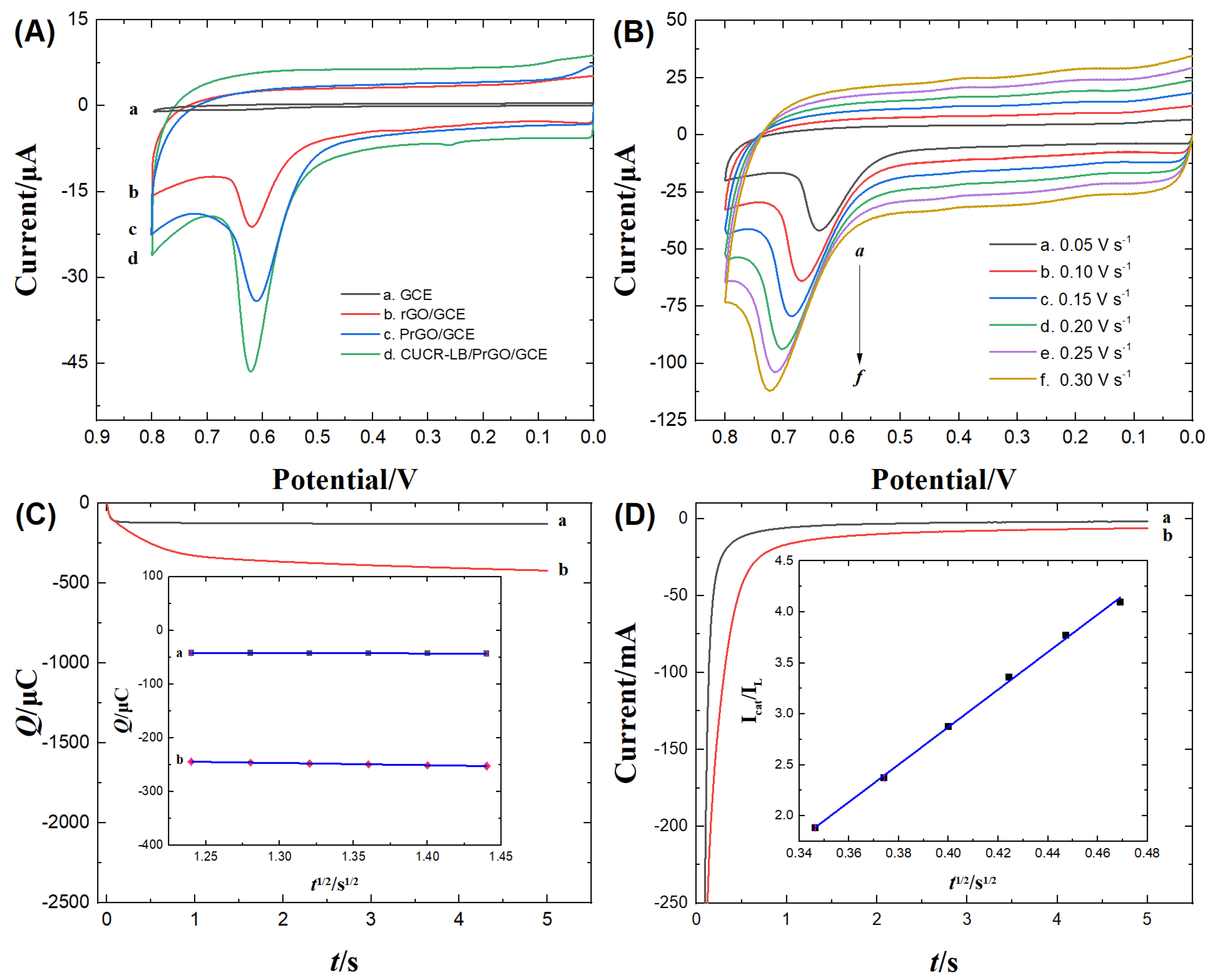

3.3. Electrochemical behavior of Trp on CUCR-LB/PrGO/GCE

3.4. Analytical method validations

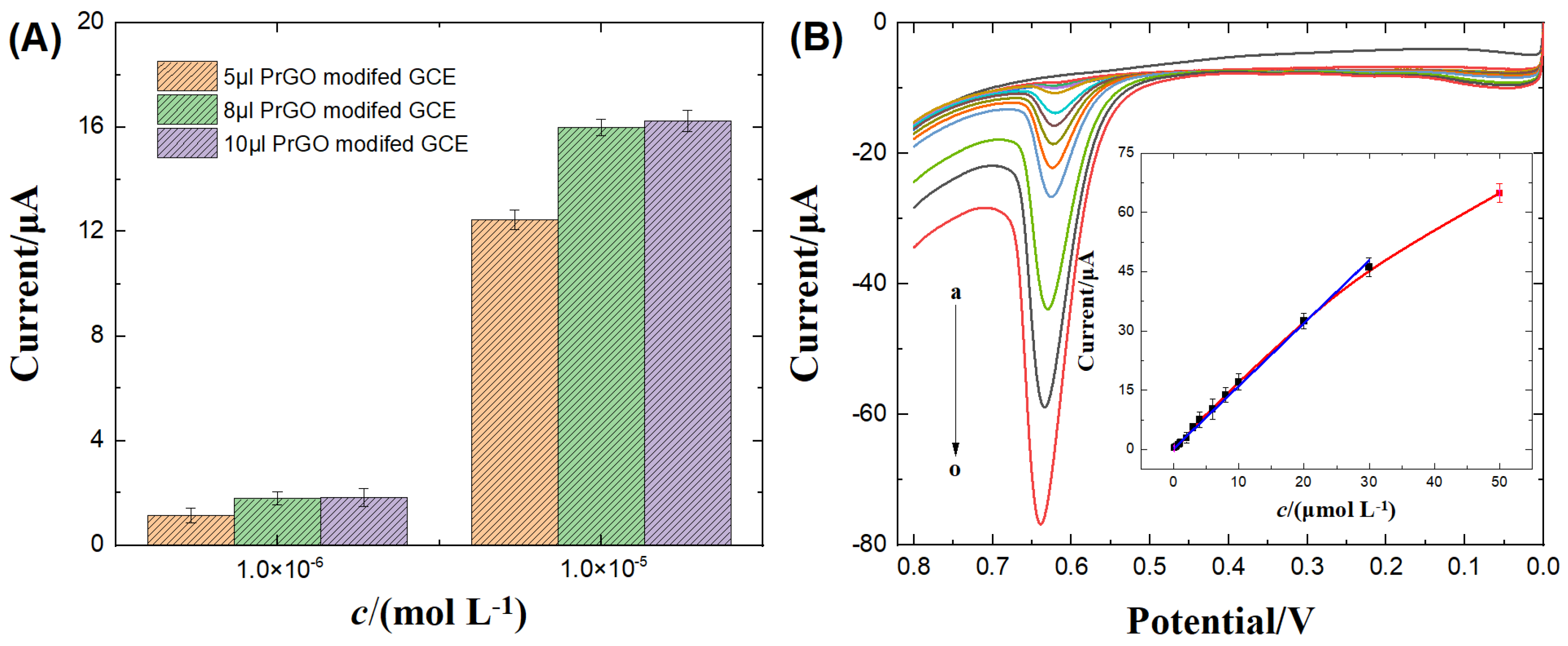

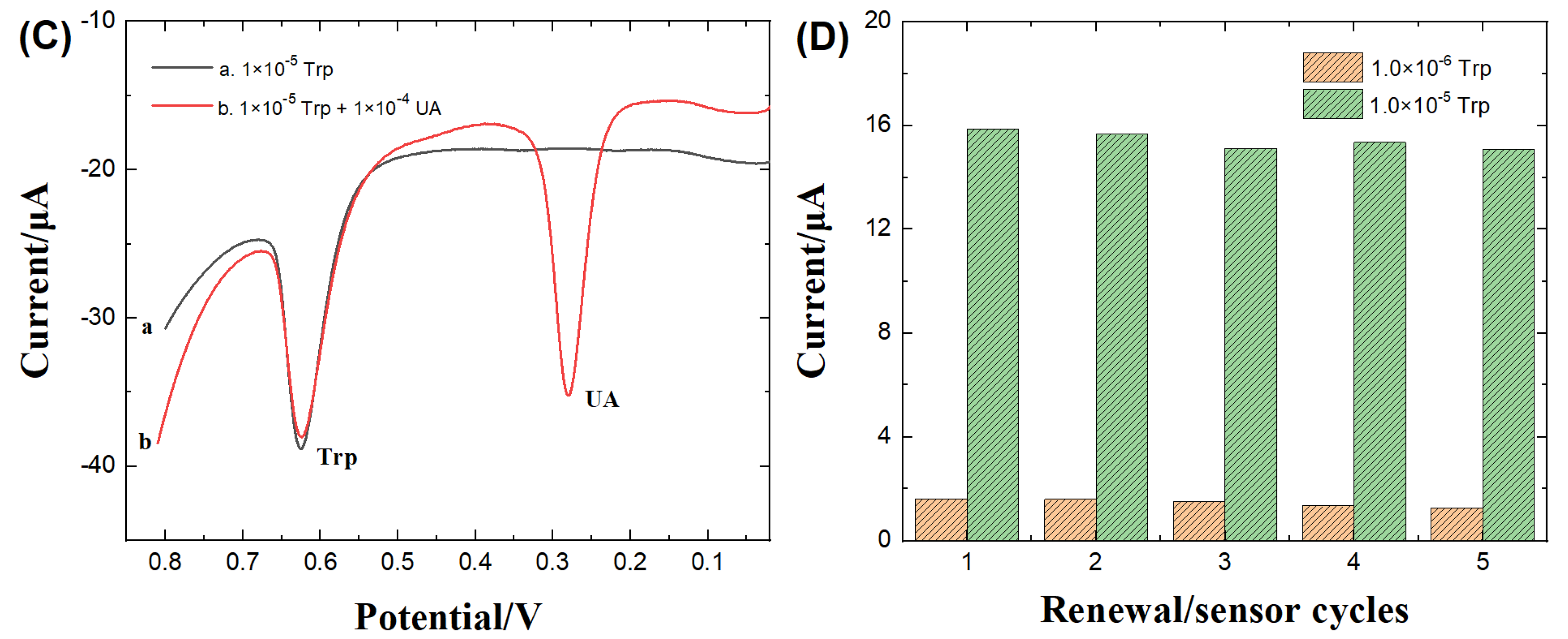

3.4.1. Optimization of Analysis and Detection Conditions

3.4.2. Analytical performances

3.4.3. Interference studies

3.4.4. Electrode renewal

3.5. Determination of Trp in amino acid injection samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedman, M. Analysis, nutrition, and health benefits of tryptophan. Int. J. Tryptophan. Res. 2018, 11, 117-128. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1178646918802282]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.; Li, J. J.; Qu, L. B.; Harrington, P. D. A highly selective and sensitive electrochemical sensor for tryptophan based on the excellent surface adsorption and electrochemical properties of PSS functionalized graphene. Talanta 2019, 196, 309-316. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2018.12.058]. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. H.; Jiang, J. B.; Xu, Z. F.; Liu, M. Q.; Tang, S. P.; Yang, C. M.; Qian, D. Facile synthesis of Pd-Cu@Cu2O/N-RGO hybrid and its application for electrochemical detection of tryptophan. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 260, 526-535. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.12.125]. [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.; Ma, D. J.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y. L. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatography method for determination of tryptophan in gastric juice. J. Digest. Dis. 2012, 13, 100-106. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00559.x]. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D. M. Rapid and direct determination of tryptophan in water using synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy. Water Res. 2003, 37, 3055-3060. [https://doi.org/10.1016/s0043-1354(03)00153-2]. [CrossRef]

- Altria, K. D.; Harkin, P.; Hindson, M. G. Quantitative determination of tryptophan enantiomers by capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. B. 1996, 686, 103-110. [https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00037-0]. [CrossRef]

- Marklova, E.; Fojtaskova, A.; Makovickova, H. HPLC methods for determination of tryptophan and its metabolites. Chem. Listy 1996, 90, 732-733.

- Widner, B.; Werner, E. R.; Schennach, H.; Wachter, H.; Fuchs, D. Simultaneous measurement of serum tryptophan and kynurenine by HPLC. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 2424-2426.

- Ozcan, A.; Sahin, Y. A novel approach for the selective determination of tryptophan in blood serum in the presence of tyrosine based on the electrochemical reduction of oxidation product of tryptophan formed in situ on graphite electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 31, 26-31. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2011.09.048]. [CrossRef]

- Karimian, N.; Hashemi, P.; Khanmohammadi, A.; Afkhami, A.; Bagheri, H. The principles and recent applications of bioelectrocatalysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. Re 2020, 7, 281-301.

- Xu, C.; Huang, K.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Can, T. Simultaneous electrochemical determination of dopamine and tryptophan using a TiO2-graphene/poly(4-aminobenzenesulfonic acid) composite film based platform. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. 2012, 32, 969-974. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2012.02.022]. [CrossRef]

- Arroquia, A.; Acosta, I.; Garcia Armada, M. P. Self-assembled gold decorated polydopamine nanospheres as electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine, uric acid and tryptophan. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. 2020, 109. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.110602]. [CrossRef]

- Hashkavayi, A. B.; Raoof, J. B.; Ojani, R. Construction of a highly sensitive signal-on aptasensor based on gold nanoparticles/functionalized silica nanoparticles for selective detection of tryptophan. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 6429-6438. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-017-0588-z]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Waterhouse, G. I. N.; Xiang, Z. P.; Che, J.; Chen, C.; Sun, W. Z. A highly sensitive electrochemical sensor containing nitrogen-doped ordered mesoporous carbon (NOMC) for voltammetric determination of L-tryptophan. Food Chem. 2020, 326. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126976]. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, J.; Raj, M.; Goyal, R. N. Determination of tryptophan at carbon nanomaterials modified glassy carbon sensors: A comparison. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167. [https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ab7e88]. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X. H.; Yang, X.; Mo, Z. L.; Guo, R. B.; Liu, N. J.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Z. Y.; Ouyang, M. X. Voltammetric enantiomeric differentiation of tryptophan by using multiwalled carbon nanotubes functionalized with ferrocene and beta-cyclodextrin. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 297, 650-659. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.12.041]. [CrossRef]

- Ratautaite, V.; Brazys, E.; Ramanaviciene, A.; Ramanavicius, A. Electrochemical sensors based on L-tryptophan molecularly imprinted polypyrrole and polyaniline. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 917. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2022.116389]. [CrossRef]

- Prinith, N. S.; Manjunatha, J. G. Electrochemical analysis of L-Tryptophan at highly sensitive poly(Glycine) modified carbon nanotube paste sensor. Mater. Res. Innovations 2022, 26, 134-143. [https://doi.org/10.1080/14328917.2021.1906560]. [CrossRef]

- Karabozhikova, V.; Tsakova, V.; Lete, C.; Marin, M.; Lupu, S. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-modified electrodes for tryptophan voltammetric sensing. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 848, 113309-113316. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2019.113309]. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, K.; Nallal, M.; Ganesan, M.; Shanmugasundaram, M.; Hira, S. A.; Gopalakrishnan, G.; Murugan, S.; Aharon, G.; Park, K. H. Fabrication of dual functional 3D-CeVO4/MWNT hybrid nanocomposite as a high-performance electrode material for supercapacitor and L-Tryptophan detection. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 445, 142020-142031. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2023.142020]. [CrossRef]

- Fazl, F.; Gholivand, M. B. High performance electrochemical method for simultaneous determination dopamine, serotonin, and tryptophan by ZrO2-CuO co-doped CeO2 modified carbon paste electrode. Talanta 2022, 239, 122982-122992. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122982]. [CrossRef]

- Nasimi, H.; Madsen, J. S.; Zedan, A. H.; Malmendal, A.; Osther, P. J. S.; Alatraktchi, F. A. a. Electrochemical sensors for screening of tyrosine and tryptophan as biomarkers for diseases: A narrative review. Microchem. J. 2023, 190. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2023.108737]. [CrossRef]

- Walcarius, A. Electrocatalysis, sensors and biosensors in analytical chemistry based on ordered mesoporous and macroporous carbon-modified electrodes. Trac-Trend. Anal. Chem. 2012, 38, 79-97. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2012.05.003]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Feng, H. B.; Li, J. H. Graphene oxide: Preparation, functionalization, and electrochemical applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6027-6053. [https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300115g]. [CrossRef]

- Demon, S. Z. N.; Kamisan, A. I.; Abdullah, N.; Noor, S. A. M.; Khim, O. K.; Kasim, N. A. M.; Yahya, M. Z. A.; Manaf, N. A. A.; Azmi, A. F. M.; Halim, N. A. Graphene-based materials in gas sensor applications: A review. Sensor. Mater. 2020, 32, 759-777. [https://doi.org/10.18494/sam.2020.2492]. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. X.; He, Q. Y.; Tan, C. L.; Wang, Y. D.; Zhang, H. Graphene-based electrochemical sensors. Small 2013, 9, 1160-1172. [https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201202896]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N. Three-dimensional porous reduced graphene oxide modified electrode for highly sensitive detection of trace rifampicin in milk. Anal. Methods 2022, 14, 2304-2310. [https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ay00517d]. [CrossRef]

- Chekin, F.; Singh, S. K.; Vasilescu, A.; Dhavale, V. M.; Kurungot, S.; Boukherroub, R.; Szunerits, S. Reduced graphene oxide modified electrodes for sensitive sensing of gliadin in food samples. ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 1462-1470. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.6b00608]. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, A.; Shinkai, S. Novel cavity design using calix[n]arene skeletons: Toward molecular recognition and metal binding. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1713-1734. [https://doi.org/10.1021/cr960385x]. [CrossRef]

- Gissawong, N.; Srijaranai, S.; Nanan, S.; Mukdasai, K.; Uppachai, P.; Teshima, N.; Mukdasai, S. Electrochemical detection of methyl parathion using calix[6]arene/bismuth ferrite/multiwall carbon nanotube-modified fluorine-doped tin oxide electrode. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 461-472. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-022-05562-5]. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. J.; Hao, Q. L.; Mandler, D. Electrochemical detection of dopamine by a calixarene-cellulose acetate mixed Langmuir-Blodgett monolayer. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1042, 29-36. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2018.08.019]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chi, C. L.; Yu, B.; Ye, B. X. Simultaneous voltammetric determination of dopamine and uric acid based on Langmuir-Blodgett film of calixarene modified glassy carbon electrode. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 2015, 221, 1586-1593. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2015.06.155]. [CrossRef]

- Xin, C. Z.; Gao, S. S.; Din, Y. X.; Wu, Y. J.; Wang, F. Direct electrodeposition to fabricate 3D graphene network modified glassy carbon electrode for sensitive determination of tadalafil. Nano 2019, 14, 93-102. [https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793292019500097]. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; An, J.; Potts, J. R.; Velamakanni, A.; Murali, S.; Ruoff, R. S. Hydrazine-reduction of graphite- and graphene oxide. Carbon 2011, 49, 3019-3023. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2011.02.071]. [CrossRef]

- Van der Heyden, A.; Regnouf-de-Vains, J. B.; Warszyński, P.; Dalbavie, J. O.; Żywociński, A.; Rogalska, E. Probing inter- and intramolecular interactions of six new p-tert-butylcalix[4]arene-based bipyridyl podands with langmuir monolayers. Langmuir 2002, 18, 8854-8861. [https://doi.org/10.1021/la025575j]. [CrossRef]

- Kämmerer, H.; Happel, G.; Mathiasch, B. Schrittweise synthesen und eigenschaften einiger cyclopentamerer aus methylenverbrückten (5-alkyl-2-hydroxy-1,3-phenylen)-bausteinen. Makromol. Chem. 1981, 182, 1685-1694. [https://doi.org/10.1002/macp.1981.021820609]. [CrossRef]

- Pei, R. J.; Cheng, Z. L.; Wang, E. K.; Yang, X. R. Amplification of antigen-antibody interactions based on biotin labeled protein-streptavidin network complex using impedance spectroscopy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2001, 16, 355-361. [https://doi.org/10.1016/s0956-5663(01)00150-6]. [CrossRef]

- Yim, J. H.; Kim, J.; Gidley, D. W.; Vallery, R. S.; Peng, H. G.; An, D. K.; Choi, B. K.; Park, Y. K.; Jeon, J. K. Calixarene derivatives as novel nanopore generators for templates of nanoporous thin films. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2006, 291, 369-376. [https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.200500370]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Robinson, J. T.; Li, X. L.; Dai, H. J. Solvothermal reduction of chemically exfoliated graphene sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9910-+. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja904251p]. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ganesan, K.; Polaki, S. R.; Ravindran, T. R.; Krishna, N. G.; Kamruddin, M.; Tyagi, A. K. Evolution and defect analysis of vertical graphene nanosheets. J. Raman. Spectrosc. 2014, 45, 642-649. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.4530]. [CrossRef]

- Bard, A. J.; Faulkner, L. R. Electrochemical methods, fundamentals and applications. 2nd ed ed.; Wiley: New York, 2001.

- Gosser, D. K. Cyclic voltammetry: simulation and analysis of reaction mechanisms. VCH: New York, 1993; p 154.

- Anson, F. C. Application of potentiostatic current integration to the study of the adsorption of cobalt(iii)-(ethylenedinitrilo(tetraacetate) on mercury electrodes. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 932-934. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60210a068]. [CrossRef]

- Pournaghi-Azar, M. H.; Sabzi, R. Electrochemical characteristics of a cobalt pentacyanonitrosylferrate film on a modified glassy carbon electrode and its catalytic effect on the electrooxidation of hydrazine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2003, 543, 115-125. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0728(02)01480-8]. [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, X. Direct electrochemical reduction of graphene oxide and its application to determination of L-tryptophan and L-tyrosine. Colloid. Surface. B 2013, 101, 183-188. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.06.007]. [CrossRef]

- Tig, G. A. Development of electrochemical sensor for detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine, uric acid and L-tryptophan based on Ag nanoparticles and poly(L-arginine)-graphene oxide composite. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 807, 19-28. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.11.008]. [CrossRef]

- Beitollahi, H.; Safaei, M.; Shishehbore, M. R.; Tajik, S. Application of Fe3O4@SiO2/GO nanocomposite for sensitive and selective electrochemical sensing of tryptophan. J. Electrochem. Sci. En. 2019, 9, 45-53. [https://doi.org/10.5599/jese.576]. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Deng, Z.; Wu, Z.; Xie, M.; Tian, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, G.; He, Q. Ta2O5/rGO nanocomposite modified electrodes for detection of tryptophan through electrochemical route. Nanomaterials 2019, 9. [https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9060811]. [CrossRef]

- Murugan, E.; Kumar, K. Fabrication of SnS/TiO2@GO composite coated glassy carbon electrode for concomitant determination of paracetamol, tryptophan, and caffeine in pharmaceutical formulations. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 5667-5676. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05531]. [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, A. A.; Elseman, A. M.; Alotaibi, N. F.; Nassar, A. M. Simultaneous voltammetric determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine, acetaminophen and tryptophan based on hybrid trimetallic nanoparticles-capped electropretreated graphene. Microchem. J. 2020, 156. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2020.104927]. [CrossRef]

- Nazarpour, S.; Hajian, R.; Sabzvari, M. H. A novel nanocomposite electrochemical sensor based on green synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/gold nanoparticles modified screen printed electrode for determination of tryptophan using response surface methodology approach. Microchem. J. 2020, 154. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2020.104634]. [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zhang, R.; Tang, Z.; Wang, H.; Deng, P.; Tang, Y. Sensitive and selective determination of tryptophan using a glassy carbon electrode modified with nano-CeO2/reduced graphene oxide composite. Microchem. J. 2020, 159. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2020.105367]. [CrossRef]

- Sangili, A.; Vinothkumar, V.; Chen, S.-M.; Veerakumar, P.; Chang, C.-W.; Muthuselvam, I. P.; Lin, K.-C. Highly selective voltammetric sensor for l-tryptophan using composite-modified electrode composed of CuSn(OH)6 microsphere decorated on reduced graphene oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 25821-25834. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c07197]. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Wang, G.; Long, Y.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Yang, B. Polydopamine/graphene/MnO2 composite-based electrochemical sensor for in situ determination of free tryptophan in plants. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1145, 103-113. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2020.11.008]. [CrossRef]

- Faridan, A.; Bahmaei, M.; Sharif, A. M. Simultaneous determination of trace amounts ascorbic acid, melatonin and tryptophan using modified glassy carbon electrode based on Cuo-CeO2-rGO-MWCNTS nanocomposites. Anal. Bioanal. Electro. 2022, 14, 201-215.

- Zhang, S.; Ling, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, C. 2D/2D porous Co3O4/rGO nanosheets act as an electrochemical sensor for voltammetric tryptophan detection. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2023, 135. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2023.109811]. [CrossRef]

| N | Cdl (F) | W (Ω cm-2) | RΩ(Ω) | Rct (Ω) | d (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.967 × 10-8 | 0.003273 | 22.99 | 336.5 | 4.4 |

| 2 | 9.726 × 10-9 | 0.002009 | 32.32 | 540.6 | 9.0 |

| 3 | 4.388 × 10-9 | 0.001972 | 40.23 | 778.4 | 13.3 |

| Electrode | CV | CC and CA | ||

| Epa (V) | ipa (μA) |

Γ*×109 (mol cm-2) |

kcat×10-3 (mol L-1 s-1) |

|

| bare GCE | 0.755 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.39 |

| rGO/GCE | 0.635 | 9.97 | 3.78 | 6.09 |

| PrGO/GCE | 0.621 | 17.89 | 9.17 | 10.9 |

| CUCR-LB/PrGO/GCE | 0.619 | 29.54 | 11.7 | 20.7 |

| Electrode | Methods | Linear range (mol L-1) |

Detection limit (mol L-1) | Reference |

| TiO2-GR/4-ABSA/GCE | DPV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 3.0×10-5 | 3.0 × 10-7 | [11] |

| ErGO/GCE | DPV | 2.0×10-7 ~ 4.0×10-5 | 1.0×10-7 | [45] |

| AgNPs/P(Arg)-GO/GCE | DPV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 1.5×10-4 | 1.22×10-7 | [46] |

| Fe3O4@SiO2/GO/SPE | DPV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 4.0×10-4 | 2.0×10-7 | [47] |

| Ta2O5-rGO/GCE | LSV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 8.0×10-6 8.0×10-6 ~ 8.0×10-5 8.0×10-5 ~ 8.0×10-4 |

8.4×10-7 | [48] |

| SnS/TiO2@GO/GCE | DPV | 1.33×10-8 ~ 1.57×10-4 | 7.8×10-9 | [49] |

| (Au/Ag/Pd)NPs/EPGrO/GCE | DPV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 6.0×10-4 | 3.0 × 10-8 | [50] |

| rGO/AuNPs/SPE | DPV | 5.0×10-7 ~ 5.0×10-4 | 3.9 × 10-7 | [51] |

| nano-CeO2/RGO/GCE | LSV | 1.0×10-8 ~ 1.0×10-5 | 6.0×10-9 | [52] |

| CSOH/rGO/GCE | DPV | 5.0×10-8 ~ 1.758×10-5 | 2.0×10-9 | [53] |

| PDA/rGO-MnO2/GCE | DPV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 3.0×10-4 | 2.2×10-7 | [54] |

| CuO-CeO2-rGO-MWCNTs/GCE | DPV | 1.0×10-8 ~ 1.35×10-5 | 7.3×10-9 | [55] |

| Co3O4/rGO/GCE | LSV | 1.0×10-6 ~ 8.0×10-4 | 2.6×10-7 | [56] |

| CUCR-LB/PrGO/GCE | LSV | 1.0×10-7 ~ 3.0×10-5 | 3.0×10-8 | This work |

| Sample | LSV | HPLC | |||||

| Labeled (μmol L-1) |

Detected (μmol L-1) |

Added (μmol L-1) |

Total Detected (μmol L-1) |

RSD (%) |

Recovery (%) |

Detected (μmol L-1) |

|

| 1a | 5.00 | 5.10(±0.14) | 2.0 | 7.18(±0.21) | 2.9 | 104.0 | 5.08(±0.05) |

| 20.0 | 24.83(±0.30) | 3.8 | 98.7 | ||||

| 2b | 2.50 | 2.56(±0.09) | 2.0 | 4.61(±0.13) | 3.1 | 102.5 | 2.54(±0.08) |

| 20.0 | 22.47(±0.24) | 3.9 | 99.6 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).