1. Introduction

Oxidative stress is caused by excess of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by an imbalance between ROS levels and antioxidant defense system [

1]. Excessive oxidative stress is associated with the development of various chronic inflammatory diseases, including prostate cancer, atherosclerosis, and vascular disease [

2]. Furthermore, chronic inflammation stimulates the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and the production of ROS, which triggers oxidative stress [

3]. Also, to treat chronic inflammatory diseases, it is important to reduce the level of free radical expression by increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and suppress inflammation by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines [

4]. Therefore, intervening with antioxidants to reduce free radicals and oxidative stress is beneficial in preventing and treating chronic inflammation [

5].

Natural antioxidants present in medicinal plants are responsible for their powerful redox ability to scavenge free radicals [

6]. In particular, the bark parts contained in medicinal plant-based antioxidant compounds play a defensive role by preventing the generation of free radicals, which contribute to alleviating oxidative stress-related diseases [

7]. Also, the bark of medicinal plants is known to be rich in phenolic polymers such as phenolic acid, lignin, stilbene, and tannins, which provide potent antioxidant properties [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Recent studies have highlighted that phenolic compounds derived from woody vascular plants, especially bark, are attractive biological sources for inhibiting oxidative stress [

8,

12]. Furthermore, phenolic compounds in the bark of medicinal plants are known to have antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, immune system enhancing, and anti-aging properties. Therefore, polyphenol compounds contained in the bark of medicinal plants are potential candidates for pharmaceutical and medical applications in treating diseases related to oxidative stress [

13].

Bangladesh is well known for its wide range of medicinal plants and herbal medicines among South Asian countries. Furthermore, it is estimated that more than 500 species of medicinal plants grow in Bangladesh, of which approximately 250 are utilized in traditional medicine preparations [

14]. Bangladesh medicinal plants have traditionally been used for therapeutic purposes including diarrhea, stomachache, dysentery, wounds, and diabetes. However, no studies have been conducted to compare the overall antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of bark parts of medicinal plants in Bangladesh. Therefore, this study aims to provide wide applicability to new sources by demonstrating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects using bark extracts of medicinal plants used in Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical reagents

Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent, gallic acid, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH), 2,4,6-tri[2-pyridyl]-s-triazine (TPTZ) phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), citric acid, sodium acetate, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), FeSO4·7H2O, and FeCl2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 2,2'-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). For cells experiments, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium-high glucose (DMEM), 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O26:B6 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) was purchased from WelGENE (Daegu, South Korea). Penicillin-streptomycin solution (P/S) was purchased from Cytiva-Hyclone Laboratories, Inc. (Logan, UT, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.2. Sample preparation

Fifteen bark methanol extract powders from medicinal plant in Bangladesh were obtained from International Biological Material Research Center (IBMRC) in the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB). The medicinal plants were collected from various regions of Bangladesh between March and October 2015 and identified by Md. Salah Uddin, a taxonomist at the Ethnobotanical Database of Bangladesh (

Table 1). A voucher specimen of the plant was deposited in the herbarium of KRIBB. The bark extract stock solutions were prepared to 1000 mg/mL with methanol. For analysis, the working solution was diluted to the indicated concentration using methanol.

2.3. Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content (TPC) of methanol extracts from the bark of 15 medicinal plants of Bangladesh was measured using the Folin-Ciocalteu method [

15]. Briefly, 10 µL of bark extract were mixed with 10 μL of Folin & Ciocalteu’s reagent and 130 µL of distilled water in a 96-well plate. After incubating for 6 min at room temperature, 100 μL of 7% Na

2CO

3 solution was added into mixture and incubated for 90 min at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 750 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). TPC of each sample was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/g dry weight.

2.4. ABTS radical scavenging activity

ABTS radical scavenging assay was investigated using a little modified method [

16]. To make ABTS radical reagent, 1.0 mM AAPH, and 2.5 mM ABTS were dissolved in PBS and reacted at 80℃ water bath for 40 min in the dark. The ABTS radical solution was filtered using a 0.45 μM PVDF syringe filter and diluted with PBS to adjust the absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.020 at 734 nm. A total 10 µL of bark extract was mixed with 240 µL of ABTS radical solution in a 96-well plate, followed by incubation at 37℃ for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm by a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The inhibition percent of ABTS

+ was calculated according to the following equation: scavenging effect (%) = (1-(

/

)

.

Where is the absorbance of control reaction and is the absorbance of the sample with ABTS+. The antioxidant capacity in samples was expressed as half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)that indicates the concentration of the sample required to scavenge 50% of radicals.

2.5. DPPH radical scavenging assay

DPPH radical scavenging activity of bark extracts was measured according to the slightly modified method [

16]. DPPH radical solution (0.1 mM) was prepared by mixing DPPH and 80% methanol. The solution was diluted with 80% methanol to adjust the absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.020 at 517 nm using a Shimadzu spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). A total of 5 μL of bark extract were mixed with 245 μL of DPPH solution and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The antioxidant capacity is expressed as percentage inhibition, calculated using the following formula: scavenging effect (%) = (1-(

/

)

. Where,

is the absorbance of the control and

is the absorbance of the sample at 517 nm. The DPPH radical scavenging capacity of bark extracts was calculated as IC

50.

2.6. Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of bark extracts was measured according to a slightly modified method [

17]. FRAP reagent was prepared by mixing 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ, and 20 mM ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl

3·6H

2O) solution at ratio of 10:1:1 (v/v), respectively. After mixing FRAP solution, it was kept at 37℃ until use. Six μL of each bark extract was mixed with 200 μL of FRAP solution and incubated at 37°C for 4 min in a 96-well microplate. The absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The standard curve linear range was between 0 and 1.0 mM FeSO

4. FRAP of bark extract was expressed as mM FeSO

4 equivalent (FSE)/g dry weight.

2.7. Cell culture

Murine RAW 264.7 macrophages (Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB), Seoul, South Korea) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S in a humidified incubator at 37℃ with 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.8. Cell viability

Cell viability was measured using MTT assay. RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with various concentration (0-100 µg/mL) of bark extracts for 24 hr. MTT solution (500 μg/mL) was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. After discarding culture media, the formazan crystals were dissolved by dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured using BioTek Cytation 5 Image reader (Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability revealed no significant toxicity at various concentration (0-5 µg/mL) of bark extracts (data not shown). Further experiments were conducted at bark extract concentration under at µg/mL.

2.9. Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR)

To The mRNA expression levels of specific genes were evaluated by qRT-PCR. RAW 264.7 macrophages were pre-treated with 1.25, 2.5, and 5 µg/mL of bark extract or vehicle for 6 hr, and then stimulated with or without 100 ng/mL of LPS for 3 hr. Total RNA extract from macrophages, synthesis of cDNA, and qRT-PCR were performed as previously described [

18]. The primers for RT-PCR were manufactured by Macrogen Co., (Seoul, South Korea), and the sequences are listed in

Table 2.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All analyses were repeated in triplicate. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test were performed using GraphPad 9.0 (GraphPad Software La Jolla, CA, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statically significant. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Total phenolic content

Phenolic compounds from medicinal plants are characterized by a benzene ring substituted with hydroxyl groups and exhibit a variety of biological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative and antibacterial activities [

16,

19]. TPC was first performed to investigate which bark extract from 15 Bangladeshi medicinal plants had the highest phenolic content (

Table 3). TPC result for 15 bark extracts ranged from 17.05 to 369.18 mg GAE/g dry weight. Among 15 types of bark extracts from Bangladesh medicinal plants,

Albizia odoratissima (369.18 ± 26.47),

Engelhardia spicata (309.50 ± 70.70),

Xylocarpus moluccensis (357.78 ± 41.41), and

Shorea robusta (243.08 ± 93.64) showed the highest TPC. On the other hand,

Wrightia arborea (17.05 ± 2.44) and

Vitex peduncularis (22.20 ± 0.37) exhibited the lowest TPC.

3.2. Total antioxidant capacity

The total antioxidant capacity of 15 bark extracts was investigated through ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP analysis. ABTS and DPPH are expressed as IC

50 of each antioxidant activity (

Table 3). Among 15 bark extracts, the highest IC

50 values for ABTS radical scavenging activity were observed from

Engelhardia spicata (60.80 ± 4.31 µg/mL) followed by

Dipterocarpus turbinatus (63.42 ± 1.59),

Shorea robusta (63.78 ± 1.49), and

Albizia odoratissima (68.84 ± 4.79). For DPPH radical scavenging activity,

Albizia odoratissima showed the lowest IC

50 values among 15 bark extracts as 181.39 ± 1.91 µg/mL, followed by

Engelhardia spicata (192.59 ± 2.42),

Shorea robusta (211.87 ± 1.59),

Bruguiera sexangula (231.28 ± 5.89), and

Saraca declinate (240.12 ± 1.52). In the case of FRAP assay,

Albizia odoratissima and

Engelhardia spicata also showed the highest reducing power as 5.62 ± 1.03 and 5.50 ± 0.73 mM FSE/g dry weight, respectively. Therefore, three bark extracts of

Albizia odoratissima,

Shorea robusta, and

Engelhardia spicata showed the highest total antioxidant activity among 15 bark extracts in both ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP assays.

3.3. Correlation between TPC and total antioxidant capacity

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to characterize the relationship between TPC and three antioxidant assays such as ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP assay (

Table 4). TPC assay had a significantly positive correlation with FRAP assay (

r=0.872,

P<0.01). Also, ABTS assay showed the highest significant correlation with DPPH assay (

r=0.972,

P< 0.01) compared to other assays correlation. However, ABTS and DPPH assay had a negative correlation with TPC and FRAP assays (ABTS&TPC;

r= - 0.664,

P<0.05, ABTS&FRAP;

r= - 0.599,

P<0.050, DPPH&TPC;

r= - 0.604,

P<0.05, DPPH &FRAP;

r= - 0.549,

P<0.05).

3.4. Comparison of antioxidant capacities by heatmap analysis

To compare TPC and total antioxidant capacity of bark extracts of 15 medicinal plants in Bangladesh, heat map analysis was performed (

Table 5). The heat map replaced the different levels of TPC and antioxidant capacities with red color for the highest level, light red for lower levels toward average level in white. Among 15 bark extracts,

Albizia odoratissima,

Engelhardia spicata, and

Shorea robusta showed the highest of TPC and antioxidant capacities. Among the rest,

Bruguiera sexangular,

Dipterocarpus turbinatus,

Sonneratia apetala, and

Xylocarpus moluccensis exhibited significantly outstanding TPC and antioxidant capacities. On the other hand,

Vitex peduncularis and

Wrightia arborea revealed the lowest levels of TPC and total antioxidant capacity among 15 bark extracts.

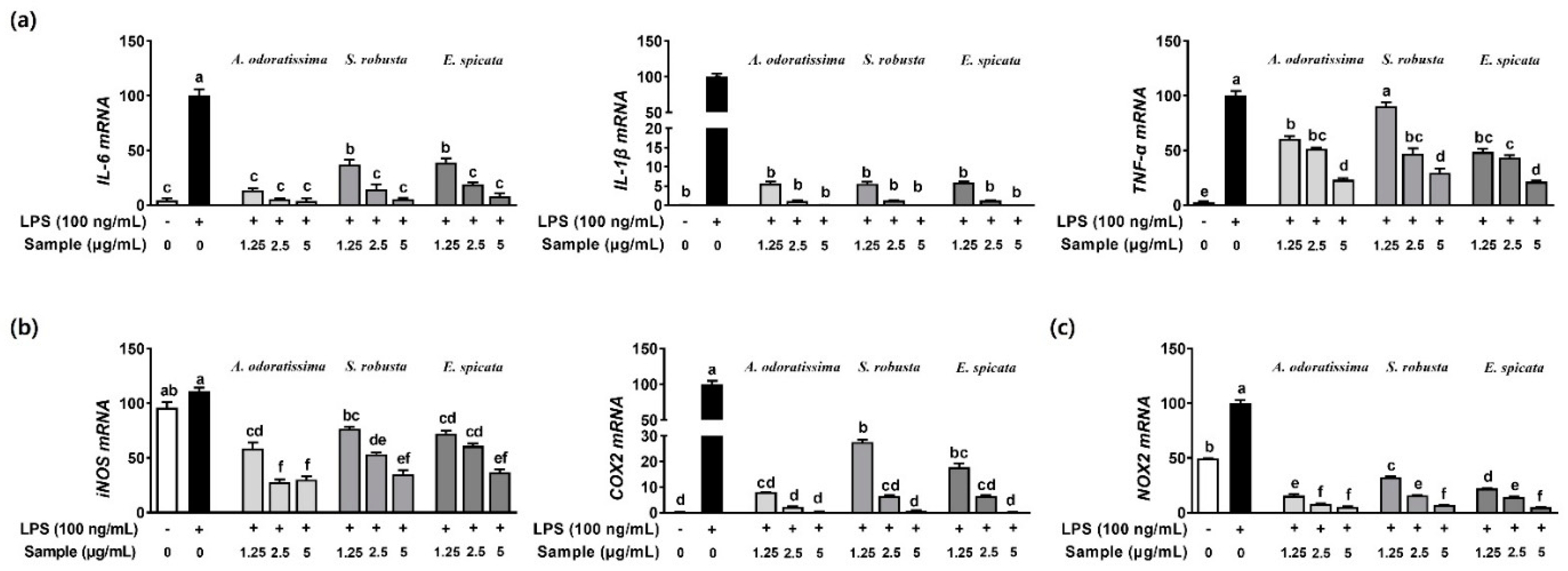

3.5. Effect of anti-inflammatory on three bark extracts in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages

Compounds with antioxidant properties are known to have anti-inflammatory abilities [

5]. Since three bark extracts of medicinal plants such as

Albizia odoratissima,

Engelhardia spicata, and

Shorea robusta showed higher TPC and total antioxidant capacity than the other bark extracts, we further investigated the anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. LPS significantly increased the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which were significantly abolished by all three bark extracts (

Figure 1a). Also, the three bark extracts significantly reduced the mRNA expression of inflammation-inducible enzymes such as inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) was significantly reduced in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages (

Figure 1b). Furthermore, the mRNA expression of NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), an enzyme that generates ROS, was significantly increased by LPS in RAW 264.7 macrophages while three bark extracts significantly suppressed the LPS-induced NOX2 mRNA expression (

Figure 1c).

4. Discussion

Phenolic compounds in medicinal plants have the ability to provide antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which help to alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation at the cellular level [

20]. Studies have demonstrated that Bangladeshi medicinal plants exert antioxidant capacity and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion [

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, the effects of bark extract of Bangladeshi medicinal plant on antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions have not been confirmed. In this study, we found that extracts derived from the bark of three medicinal plants in Bangladesh, namely

Albizia odoratissima,

Engelhardia spicata, and

Shorea robusta, exhibited the highest total antioxidant capacity compared to 15 different types of bark extracts. Also, these three bark extracts showed anti-inflammatory properties by reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammation-inducing enzymes in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages.

Phenolic compounds are known to have superior antioxidant ability due to particular chemical structures, which contain conjugated double bonds and hydroxyl groups [

25]. In the present study, three bark extracts,

Albizia odoratissima,

Engelhardia spicata, and

Shorea robusta exhibited the highest TPC among 15 types of bark extracts of Bangladesh medicinal plants, which was considered to have the highest phenolic compounds content formed by conjugated double bonds and hydroxyl groups. Also, three bark extracts showed the highest DPPH and ABTS radicals scavenging activity and FRAP activity among 15 types of bark extracts. The strong antioxidant properties of three bark extracts are partly due to their high phenolic compound content, which exerts a scavenging effect on ROS and interface with oxidative free radicals [

26]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that high abundance of phenolic compounds and strong antioxidant capacity of three bark extracts are closely related to traditional uses to improve body's immune system against ROS. The bark extract of

Albizia odoratissima, which has been traditionally used in Bangladesh to treat diseases such as coughing, bronchitis, and diabetes, has been reported to contain flavonoids and terpenoids [

27]. Similarly, the bark extract of

Shorea robusta, which is known for medicinal use in treating scabies and skin diseases in Bangladesh, contains major components such as flavonoids and tannin. [

28,

29]. Also, phenolic derivatives such as flavonoids, triterpenes, diarylheptanoids, and aromatic acid/esters were isolated from the genus

Engelhardia [

30].

Multiple inflammatory triggers, such as overproduction of ROS during oxidative metabolism, have been documented to initiate the inflammatory cascade, leading to the production and release of proinflammatory cytokines [

31]. Furthermore, elevated production of ROS resulting from oxidative stress can induce the oxidation of amino acids, lipid peroxidation, and oxidative damage to DNA, thereby triggering an inflammatory response [

32]. In this study, the three bark extracts, including

Albizia odoratissima,

Engelhardia spicata, and

Shorea robusta significantly suppressed the mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines and inflammation-inducible enzymes in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Also, three bark extract exhibited the highest phenolic content with total antioxidant capacity by reducing ABTS and DPPH free radicals scavenging activity and FRAP capacity. The high antioxidant capacity of phenolic compounds can reduce oxidative stress-mediated inflammation through the inhibition of nuclear factor (NF)-κB-mediated proinflammatory cytokines [

31]. Therefore, the strong antioxidant capacity and high phenolic content of the three bark extracts likely contribute to suppressing LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages by reducing oxidative stress. In particular, three bark extracts completely suppressed LPS-induced the mRNA expression of NOX2 in macrophages. NOX2 is known to regulate the production of ROS within macrophages, which stimulates the inflammatory process by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines [

28]. Although this study did not evaluate the effect of three bark extracts on ROS production in macrophages, three bark extracts were observed to potentially reduce the elevated ROS production by inhibiting NOX2 gene expression in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. Finally, since the three bark extracts exhibited strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory abilities, it is necessary to find phenolic compounds in the three bark extracts that scavenge free radical activity and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides that three bark extracts including Albizia odoratissima, Engelhardia spicata, and Shorea robusta among the 15 bark extracts of medicinal plants from Bangladesh have the strongest antioxidant abilities and anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. The three bark extracts of Albizia odoratissima, Engelhardia spicata, and Shorea robusta exhibited the strong total antioxidant capacity with high amount of phenolic compounds contents, which contribute to suppress the LPS-stimulated inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Constantly, three bark extracts significantly reduced LPS-induced the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammation-inducible enzymes. However, further studies are required to investigate phenolic compounds of three bark extract from medicinal plant in Bangladesh that potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, our findings suggest that the three bark extracts from medicinal plants in Bangladesh have great potential as valuable nutraceutical resources for both the prevention and treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.L.; methodology, J.W.L., S.J., H.L. and S.H.B.; software, J.W.L., M.-B.K., and H.L.; validation, J.W.L., M.-B.K., H.L. and S.H.B.; formal analysis, J.W.L., S.J., H.L. and S.H.B.; investigation, J.W.L., S.J., H.L. and S.H.B.; resources, M.S.U., S.W.L. and S.G.L.; data curation, J.W.L., M.-B.K., H.L. and S.G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.L., M.-B.K., H.J.L, and S.G.L.; writing—review and editing, J.W.L., M.-B.K., H.L., and S.G.L.; visualization, J.W.L., M.-B.K, S.J. and H.L.; supervision, S.G.L.; project administration, S.G.L.; funding acquisition, S.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Research Grant of Pukyong National University (2023)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the medicinal plant extracts in Bangladesh provided from the Ethnobotanical Database of Bangladesh, and International Biological Material Research Center (IBMRC) in the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lushchak, V.I. Free radicals, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and its classification. Chemico-biological interactions 2014, 224, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative stress. Annual review of biochemistry 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feghali, C.A.; Wright, T.M. Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci 1997, 2, d12–d26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.H.; Ma, J.N.; Park, J.H.; Jung, H.W.; Park, Y.K. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of MOK, a polyherbal extract, on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. International journal of molecular medicine 2019, 43, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.K. Does the interdependence between oxidative stress and inflammation explain the antioxidant paradox? Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramawat, K.; Dass, S.; Mathur, M. The chemical diversity of bioactive molecules and therapeutic potential of medicinal plants. Herbal drugs: ethnomedicine to modern medicine 2009, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abeyrathne, E.D.N.S.; Nam, K.; Huang, X.; Ahn, D.U. Plant-and animal-based antioxidants’ structure, efficacy, mechanisms, and applications: A review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, C.; Coșarcă, S.; Muntean, D.-L. A critical review of phenolic compounds extracted from the bark of woody vascular plants and their potential biological activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Cheng, S.; Yuan, Z.; Leitch, M.; Xu, C.C. Valorization of bark for chemicals and materials: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 26, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, M.; Chadni, M.; Barba, F.J.; Grimi, N.; Bals, O.; Vorobiev, E. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of polyphenols from Quercus bark. Industrial Crops and Products 2015, 77, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinisalo, M.; Kårlund, A.; Koskela, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Karjalainen, R.O. Polyphenol stilbenes: molecular mechanisms of defence against oxidative stress and aging-related diseases. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, T.; Choi, Y.-W.; Kim, Y.-K. Impact of different extraction solvents on phenolic content and antioxidant potential of Pinus densiflora bark extract. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, S.B.; Roy, S.; Das, S.; Dhangadamajhi, G. Phytochemicals screening, phenolic estimation and evaluation for anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial activities of sequentially Soxhlet extracted coconut testa. Food and Nutrition Sciences 2019, 10, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.J.; Grice, I.D.; Tiralongo, E. Cytotoxic effects of Bangladeshi medicinal plant extracts. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, C.; An, H.W.; Han, W.; Lee, J.W.; Shrestha, K.K.; Jung, W.-K.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, S.G. Screening of antioxidant capacity of Nepali medicinal plants with a novel singlet oxygen scavenging assay. Food Science and Biotechnology 2023, 32, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.H.; Cao, L.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, H.-R.; Nam, T.J.; Lee, S.G. The comparison of total phenolics, total antioxidant, and anti-tyrosinase activities of Korean Sargassum species. Journal of Food Quality 2021, 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Analytical biochemistry 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Han, W.; Lee, S.G.; Shin, J.H. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Chlorogenic Acid on Macrophages: A Simplified Simulation of Pharmacokinetics Following Ingestion Using a Windup Syringe Pump. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, B.R.; Heleno, S.A.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Phenolic compounds: Current industrial applications, limitations and future challenges. Food & function 2021, 12, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tungmunnithum, D.; Thongboonyou, A.; Pholboon, A.; Yangsabai, A. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: An overview. Medicines 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.E.; Islam, K.M.D.; Billah, M.M.; Biswas, R.; Sohrab, M.H.; Rahman, S.M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of Heritiera fomes (Buch.-Ham), a mangrove plant of the Sundarbans. Advances in Traditional Medicine 2020, 20, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesmin, R.; Das, P.K.; Belal, H.; Aktar, S.; Ayesha, M.; Rakib, M.A.; Islam, F.; Khanam, J.A. In vitro antioxidant and antidiabetic assessment of extracts from the bark of Michelia champaca, a medicinal plant in Bangladesh. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2019, 8, 1505–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, P.; Debnath, S.L.; Devnath, H.S.; Saha, L.; Sadhu, S.K. Analgesic, Anti-Inflammatory, Antipyretic, and in Silico Measurements of Sonneratia caseolaris (L.) Fruits from Sundarbans, Bangladesh. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, S.J.; Shilpi, J.A.; Delazar, A.; Nahar, L.; Sarker, S.D. Free radical scavenging activity of some Bangladeshi plant extracts. Advances in Traditional Medicine 2004, 4, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Singla, R.K.; Dubey, A.K.; Garg, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Fiorino, M.; Ameen, S.M.; Haddad, M.A.; Al-Hiary, M. Natural polyphenols: Chemical classification, definition of classes, subcategories, and structures. 2019, 102, 1397–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Shah, M.D.; Gnanaraj, C.; Iqbal, M. In vitro total phenolics, flavonoids contents and antioxidant activity of essential oil, various organic extracts from the leaves of tropical medicinal plant Tetrastigma from Sabah. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine 2011, 4, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powar, N.S.; Kasarkar, A.R.; More, V.N. Preliminary phytochemical analysis of different plant parts of Albizia odoratissima (LF) benth. Journal of Medicinal Plants 2020, 8, 144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.A.; Brindavanam, N.B.; Kimothi, G.P.; Aeri, V. Evaluation of in vivo anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Dillenia indica f. elongata (Miq.) Miq. and Shorea robusta stem bark extracts. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease 2016, 6, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainsal, N.; Goyal, P.; Singh, J. Shorea Robusta Gaertn. F: A Multi-therapeutic Potential Indigenous Drug. Plant Archives 2020, 20, 3313–3322. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.-M.; Shan, Q.; Zhou, F.-J.; Hua, J.; Hou, W.-B. Chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of genus Engelhardia. Chinese Herbal Medicines 2018, 10, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M.C.; Rahu, N. Oxidative stress and inflammation: what polyphenols can do for us? Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, L.F.; Barreto, F.; da Silva, E.G.; Andrades, M.E.; Guimarães, E.L.M.; Behr, G.A.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Bernard, E.A. Regulation of LPS stimulated ROS production in peritoneal macrophages from alloxan-induced diabetic rats: Involvement of high glucose and PPARγ. Life sciences 2007, 81, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).