Blacktip reef sharks were the predominant elasmobranch observed in the study area, though other species, including whitetip reef sharks (Triaenodon obesus), nurse sharks (Nebrius concolor), pink whiprays (Himantura fai), and eagle rays (Aetobatus narinari), were also present on the back reef. Sporadic sightings of lemon sharks (Negaprion acutidens) and grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) were also recorded.

The initial feeding sessions in Section A primarily attracted the mature female blacktip reef sharks whose core ranges included the observation site. Over time, additional blacktips became aware of the weekly provisioning events. Many of them gathered in advance, presumably cued by the sound of the kayak traversing the back reef towards Site A. A few mature males occasionally joined the females, as did juveniles exceeding an estimated 70 cm in standard length.

After approximately three months, all resident individuals had been identified and were recognizable. These sharks tended to arrive at the beginning of the feeding sessions and dispersed roughly 30 minutes later. Following their departure, and often after an interval devoid of shark activity, new individuals appeared. These were found to be transients, prompting consideration of their origins. Individual identification of these transients showed that movement is a key component of C. melanopterus’ behavioural ecology.

The provisioning sessions resulted in an aggregation of reef blacktips that facilitated social interactions. Many of these occurred down-current from the food source, beyond visual range. By drifting unobtrusively down-current, the observer could approach sufficiently to observe these interactions. Socializing occasionally superseded feeding, as evidenced by instances where food remained untouched on the substrate.

Observations totalled 506 hours across 501 sessions, with 67 % of observation time (338 hours) during low-light sunset conditions, a key period for activity (Papastamatiou et al. 2009). The sessions recorded 11,514 behavioural events, including ranging, habitat shifts, agonistic displays, and social interactions, resulting in an ethogram (Porcher 2023a). A total of 475 reliably-distinguishable individual sharks were identified, culled from 581 initial records for consistent re-identification.

3.1. The Community

Female C. melanopterus exhibited pronounced site fidelity to core home ranges of an estimated 0.5 km². The lagoon’s natural features significantly influenced their spatial dynamics, with a marked preference for the outer third of the lagoon along the barrier reef, where the coral habitat was healthiest.

Table 1 presents the counts of adult blacktip reef sharks identified at each study site, detailing the numbers of residents, the average Residency Index, periodic transients, rare transients, and individuals observed either once or during a single brief period.

Certain individuals, both adults and juveniles, scored a Residency Index exceeding 0.5 for a continuous period spanning multiple months. Upon their disappearance, it was not possible to determine whether they had died or departed; neither were the reasons behind their consistent temporary presence evident. In one instance, the carcass of the individual was found, whereas in all other cases, the reason—death or departure—remained unknown.

A notable individual, designated #109, attended sessions exclusively between December and April for over three consecutive years, then disappeared in 2004 amid intensive shark finning activities. During her seasonal presence, she maintained a Residency Index above 0.6, yet she was not a year-round resident. Her case highlights the behavioural variability in the species (Porcher 2022).

Sharks with home ranges west of the study site were not only aware of the auditory cues of the approaching kayak but were also positioned to detect and follow the westward-flowing scent trail to the feeding sessions. Conversely, individuals with core ranges up-current (east) of the site were less likely to encounter these cues and scored lower Residency Indexes.

Some individuals—predominantly males—appeared at intervals of some months, suggesting a cyclical movement pattern, though their core ranges remained unidentified.

During the years of the study, all adult blacktip reef sharks residing within the lagoon were eventually identified. However, the limited number of sessions conducted at Site E and Papetoai precluded accurate determination of temporary visitors in those areas. As the majority of observation sessions occurred in Section A, most adult blacktips ranging across the western half of the lagoon were first observed and catalogued there, and are listed in

Table 1 under ‘Site A.’

Juvenile blacktip reef sharks identified during the study are detailed in

Table 2, categorized as residents, periodic transients, or individuals observed either once or for a single period. No rare transients were identified among juveniles. Sharks initially recorded as young-of-the-year matured over the course of the study, with each assigned to a category based on its status at first identification.

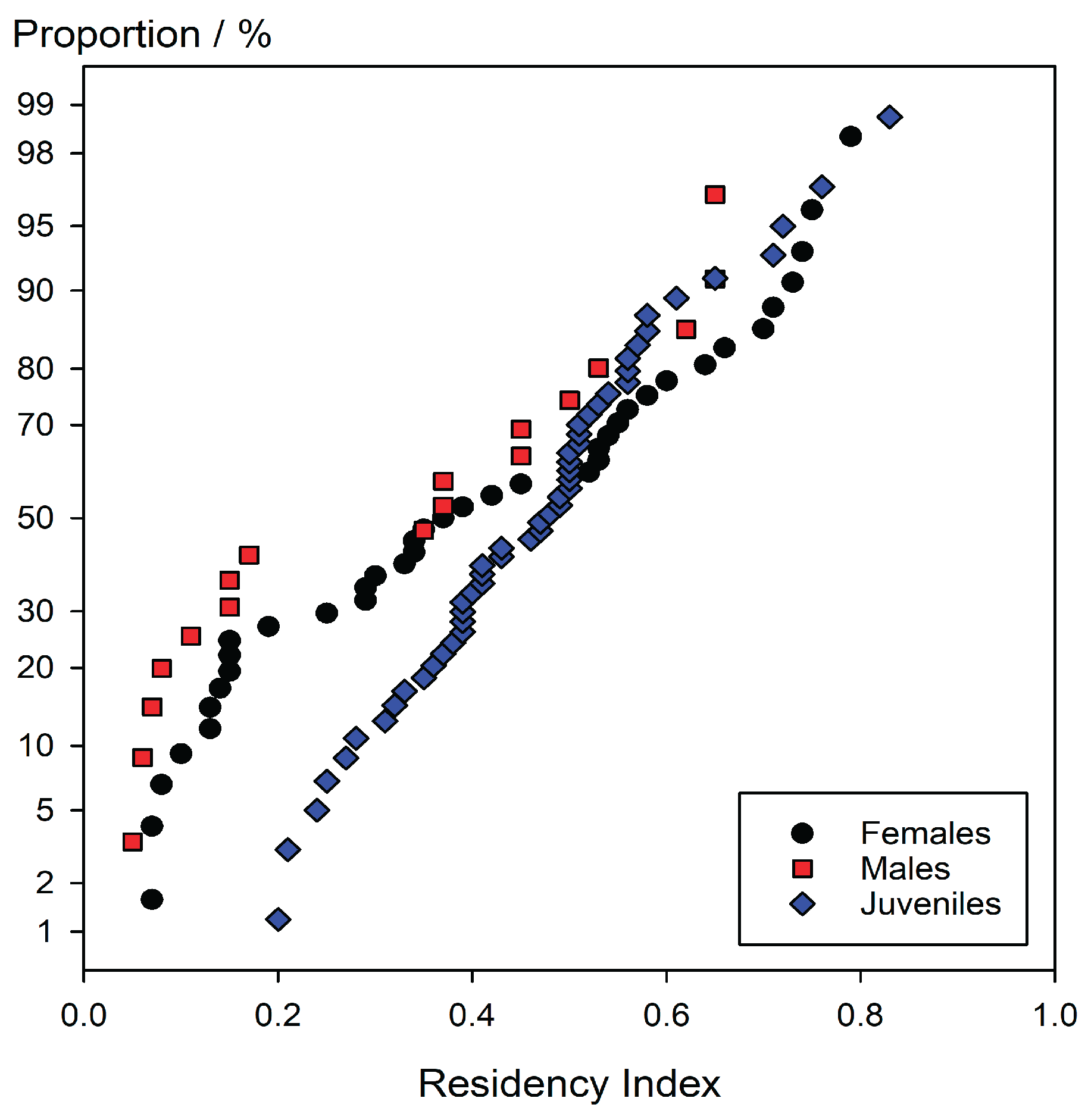

If the sightings were essentially random, and the sharks showed no site preference, then we would expect the calculated residency to be a binomial random variable centred on 0.5. With a large enough sample, the distribution would approach normal. Accordingly, the data can be plotted as cumulative proportion on a normal probability scale vs. Residency Index (R). For this, the n Residency Index values are sorted in ascending order, i.e. given a rank value, k, and the adjusted proportion, p, found from (Mandel 1964):

which gives a good approximation to linearity for truly normal data. These plots are shown in

Figure 3.

It is apparent from these plots that, firstly, none shows a reasonable approach to linearity, secondly that they are not centred on 0.5, and thirdly that samples are clearly not from the same distribution: males, females and juveniles differ. Were the data simply from a distribution other than normal then simple curvature would be apparent, which is not the case. Given that and the first point means that they are each a mixed distribution. It is then appropriate to 'censor' or section the data according to the apparent more or less abrupt changes of slope and replot each portion accordingly (

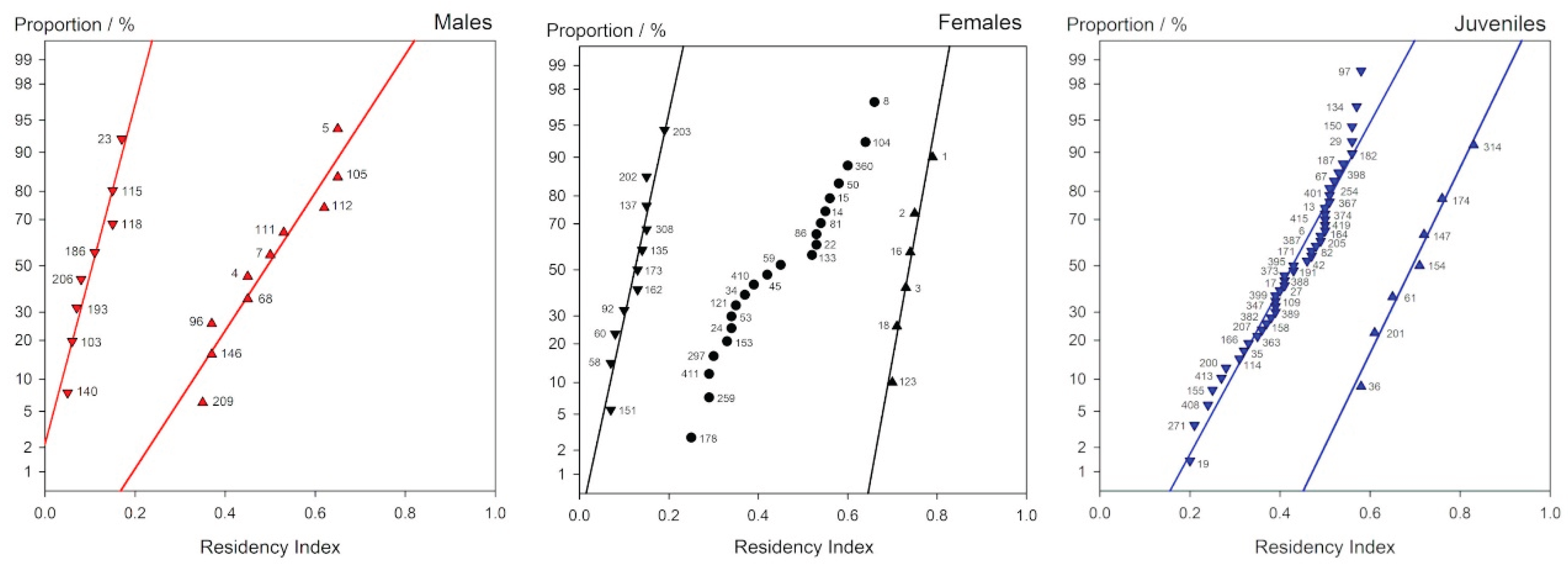

i.e. recalculating the proportion, p, for each subset). These sectioned data are shown in

Figure 4. In all except the ‘middle’ group of females the plots show a reasonable approach to a straight line, suggesting that these individual data subsets are near-normal in distribution.

Thus, for the males, there is a strong change of slope at R ~0.2. The weighted mean residencies are 0.13 and 0.52. These values would suggest that the 8 sharks of the first group were periodic transients while the other 10 show significant site fidelity to Section A.

The female plot in

Figure 4 initially suggests discontinuities at R ~0.17 and ~ 0.68. Replotting accordingly it is seen that again a group (some 11 sharks) shows a low weighted mean R

w ~0.13 and thus a low tendency to visit, while 6 have a strong bias towards the Section A region (R

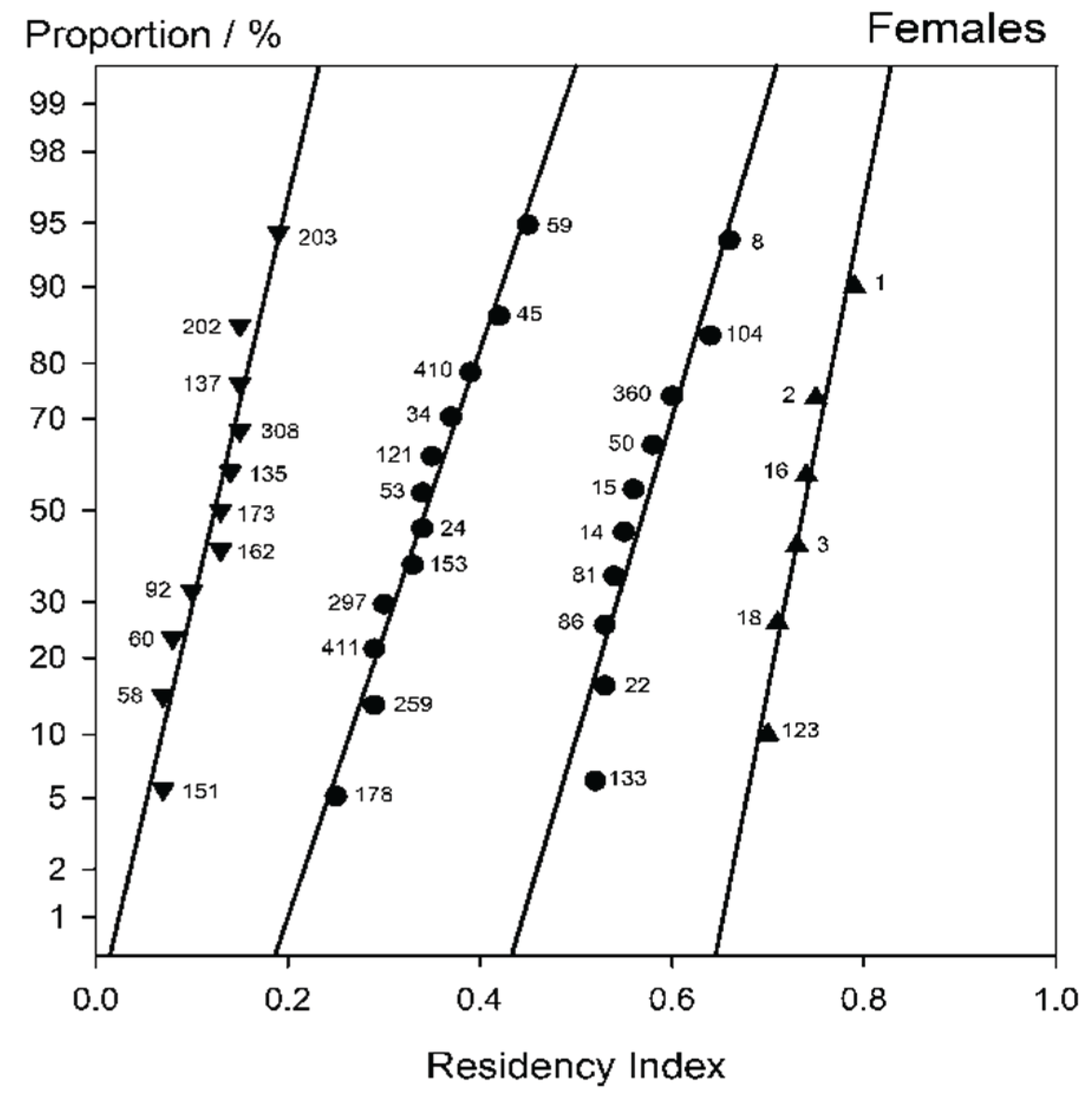

w ~0.74). The remainder however, albeit with a mean close to 0.51, in fact do not yield an acceptable approach to a straight line plot, again strongly implying a mixed distribution. The break here appears to be at R ~0.5. Making the further section at this point yields

Figure 5. Here now all four plots show an acceptable approach to linearity, with similar slopes (equivalent to standard deviation). The two middle groups have R

w ~0.37 and ~0.58.

Treating the juveniles similarly, the slope change appears at about R ~ 0.6 as seen in

Figure 4. The weighted mean residencies are ~0.47 and ~0.67. This suggests that a small group (7 sharks) strongly preferred the study areas, while the rest visited less often (this also looks like a mixed distribution, but any break point is not clear). Given that juveniles were observed to prefer the thick coral labyrinths of western Section B, up current from Site A, this is not surprising.

It must be borne in mind that censoring is an absolute cut, while it can be expected that for mixed distributions the tails overlap. That is, say in

Figure 4 for males, and more clearly so for juveniles, the lower subset could include members of the lower tail of the upper set, and

vice versa. Full identification of the members of each set is not possible. The same applies in similar fashion to the four sets of

Figure 5, and indicates the danger involved in sectioning in this fashion. In these circumstances, statistics for the various sets are necessarily biased by that censorship, and care is required to avoid strong implications. A further caution is necessary: absence of observation does not mean absence from the larger area – sampling is necessarily biased, and the R values biased downwards as a result: even a fully-resident shark would not be expected to be observed on every occasion.

Overall, then, avoiding over-interpretation, there would simply appear to be evidence that there are behavioural differences between groups within and between males, females and juveniles, the sources of which variations are yet to be identified. Even so, one possibility that could be explored is the effect of core ranges with (as might be expected) diffuse boundaries (

Figure 6).

Suppose the observation site study area was in the overlap between two such ranges, closer to the centre of one than the other. The frequency of observation would be greater for the one, yet both sharks would in fact be fully resident in their core range. If now each such range had several occupants, the effect would be as observed in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, where the Residency Index is now in part a measure of relative location of the observation study site to the barycentre of each. Of course, ranges vary in size and shape depending on the habitat, while sharks roam widely in as yet unknown ways. Individual variation in terms of distances travelled and roaming tendencies result in transient observations at different frequencies. The subsets of those sectioned residency plots therefore may represent distinct roaming patterns used by sharks coming from distant ranges, possibly some on the same island, others on different islands. Distinguishing and mapping their ranges would require multiple study sites with data density similar to that for Site A.

3.1.1. The Nurseries and Juveniles

A prominent blacktip reef shark nursery was identified along the curvature of the barrier reef adjacent to Cook’s Bay (Section E), where an annual influx of 100–200 neonates was consistently documented. In contrast, smaller nurseries at the western extremity of the reef and the eastern end of the Papetoai lagoon hosted the offspring of only one or two females.

Approximately 6 weeks to 2 months post-parturition, neonates (measuring an estimated 50 cm) began dispersing along the reef in small groups. They exhibited heightened vigilance, repeatedly circling outward before regrouping, always poised to retreat to their shallow refuges.

Young-of-the-year occupied shallow zones characterized by dense coral formations which were scattered throughout the lagoon (Galvin and Pointer, 1985). Between the ages of one and two years they reached an estimated length of about 70 cm, and began to roam freely in the lagoon, mingling with adult conspecifics without displaying avoidant behaviour. However, they were not seen in the deeper regions of the lagoon, including the area around Site C, and parts of the barren area separating Sections A and B.

Juvenile male sharks exhibited reduced growth rates compared with their female counterparts, with some individuals only marginally larger than neonates upon initial observation at feeding sessions. Clasper development commenced approximately two years later, during the third to fourth year of life, with claspers initially appearing as small buds. Fully-proportional clasper development was typically achieved within one year, corresponding to an age of approximately four to five years.

The onset of clasper development displayed inter-individual variability in timing, possibly attributable to differences in birth dates—the earliest in September, and the latest in February. In some males, clasper maturation occurred sufficiently early to enable mating the same year. However, in others, clasper development initiated later in the year, resulting in immature claspers at the onset of the mating season. Consequently, while some males were capable of mating in their fourth to fifth year, others did not reach reproductive maturity until their fifth to sixth year, likely due to the misalignment of the timing of clasper development with the reproductive season.

By the year preceding maturity, males measured approximately 80 cm to 1 m (estimated) and initiated a transition to the fore reef, a shift corroborated by visual assessment of clasper length (Mourier et al., 2013). Juveniles were never seen on the fore reef.

One male individual, #19, was first identified on August 4, 1999 presumably in his second year. He was periodically observed at Site A during his maturation. Subsequent sightings when he was in his fourth year occurred at the fore reef site during a two year period in which he was not seen in the lagoon—from May 11, 2002, to April 26, 2004. In 2008, he was identified and re-sighted multiple times by Mourier

et al. (2012) at their Opunohu observation site on the fore reef opposite Section A, as shown in

Figure 7.

It was also during the subadult phase, between approximately 4 and 5 years of age, that female sharks established their home ranges. They were notably larger than the males, approaching full size at an estimated 1.5 m. Although mating was evident in subadult females, as indicated by the presence of extensive mating wounds, pregnancy was not observed, with the exception of one individual (Shark #29). In contrast, mature females consistently achieved pregnancy annually following mating, with no exceptions recorded. Only two instances were documented where mature females failed to carry pregnancies to term. In one such case, the pregnancy terminated within three days of a spear or knife wound into the lateral body surface.

Unlike mature females, subadults retained a slender physique and displayed frequent rapid acceleration and enhanced velocity. Their behavioural profile included a pronounced inclination for exploration and a tendency towards bolder actions. By the subsequent year, these individuals had developed a more robust build, accompanied by a relative reduction in agility as pregnancy progressed, and often the loss of their earlier boldness (see Porcher, 2022, for an anecdotal account of this transformation).

3.2. Movements

Figure 8 compares the percentage of identified adults and juveniles in each of the categories specified in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.2.1. Inter-Site Movements

Figure 9 shows blacktip reef shark movements observed between sites during the 6.5 years of the study.

Despite approximately 300 m of deep water (Opunohu Bay) separating the study area from the Papetoai lagoon, distinct communities of blacktip reef sharks were observed in each region. These communities consisted of females, juveniles, and occasional males, with minimal evidence of inter-bay movement. Only one female, #179, consistently identified and re-sighted in the Papetoai lagoon, was recorded at Site A, appearing there twice in two different years. No individuals from the study lagoon were observed in the Papetoai lagoon.

Although resident females from Section A exhibited reluctance to cross the bay, they were sighted during daylight hours on the fore reef opposite their core ranges, occasionally displaying behaviours suggestive of hunting as they moved parallel to the reef beneath breaking waves. Blacktip reef sharks were frequently observed entering the back reef from the fore reef with incoming waves, indicating that hunting fish beneath the waves breaking along the fore reef might constitute a component of their predatory repertoire.

During observational sessions in Section E, only two unidentified female blacktips were recorded; the remainder had been previously identified at Site C, with 67 % of individuals identified at Site E also frequenting Site C. However, no females identified at Site A were observed at Site C. Of the 37 females documented at Site C, only 7 (19 %) were ever sighted in Section A, typically on a single occasion. Adult individuals observed at Site C appeared to be transients, with different individuals present at each session and no residents identified. Juveniles largely avoided this location, with only one recorded sighting of two older juveniles travelling together. Logistical constraints precluded additional sessions at Site C and in Sections D and E, which might have further elucidated these patterns.

A notable female, designated #351, was initially identified at Site C and subsequently re-sighted there on five separate occasions. She was also observed at Site A sessions on 22 occasions and at Site B sessions on 13 occasions. Despite this extensive sighting record across the western side of the lagoon, her exact core range could not be determined. Due to long periods of absence, it is likely that her home range was not in the study lagoon.

3.2.2. Males

The male blacktip reef sharks that roamed the back reef displayed reduced site fidelity to specific core ranges compared with females, attending feeding sessions irregularly throughout the year, with some appearing infrequently. Their Residency Indexes were generally lower than those of the females.

In 1999, three adult males and one maturing juvenile were regularly observed; subsequently, one succumbed to a wasting disease and was later succeeded by a maturing male juvenile. Between three and six additional males, presumed to inhabit the back reef rather than the fore reef, were sporadically sighted at Sites B and C. In contrast, males ranging the fore reef typically appeared on the back reef solely during the mating season (November to March; Porcher, 2005), arriving in pairs or small groups (<6) and not associating with lagoon-ranging males.

Males ranging Section A were occasionally observed traversing both Sections A and B within a single morning, though, with one exception, they were not observed at Site C. Long term observation suggests that males used larger core ranges and exhibited greater daily mobility than females. During the reproductive season, they were frequently absent, sometimes for periods as long as five months.

Only one male identified at the fore reef site was recorded at Site A (on a single occasion), and another had originally been identified—seen only once—at Site C. At the fore reef site, water depth was approximately 7 m, and since male blacktips moved near the seafloor, their identification required diving to the bottom to sketch dorsal fin markings on both sides while maintaining continuous visual contact, without resurfacing for air. Consequently, most males encountered on the fore reef remained unidentified, limiting their representation in the dataset. Nonetheless, it was determined that these unidentified individuals were distinct from those previously identified on the back reef.

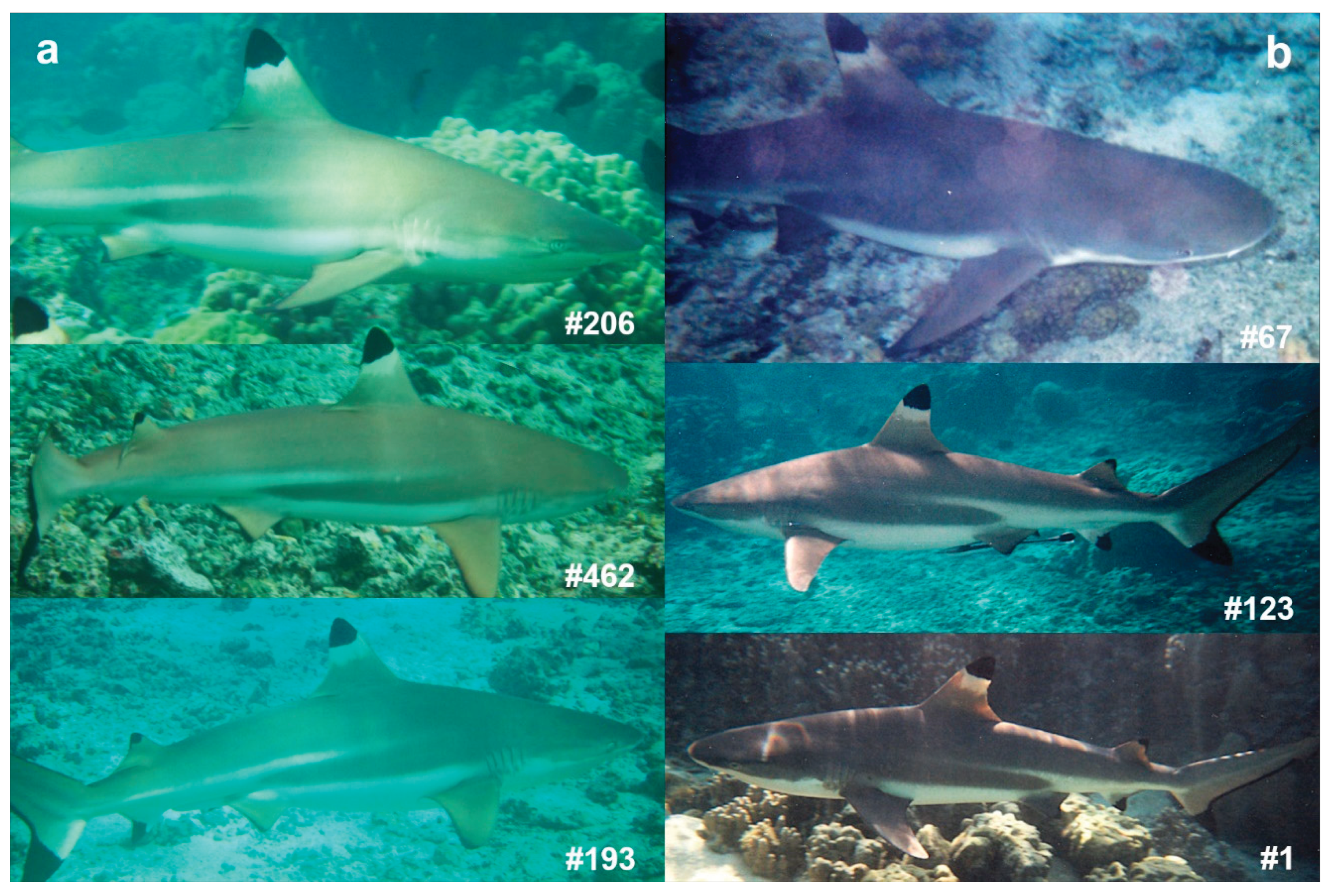

A distinction in coloration was seen in blacktips ranging the fore reef, as opposed to the back reef, which reflected their respective habitats. Those residing on the fore reef, and remaining near the seafloor where they were shielded from solar radiation, exhibited light brown or yellow-ochre hues. In contrast the sharks residing in the lagoon were subjected to prolonged sunlight exposure in shallow waters, and displayed dark brown or grey pigmentation. This difference is shown in

Figure 10.

Such chromatic variation provided a reliable indicator of an individual’s primary habitat. Similar sun-induced colour changes in shallow-water environments have been documented in other shark species, including nurse sharks (Johnson, 1978) and hammerheads (Lowe and Goodman-Lowe, 1996). However, colour also has a genetic basis, for neonates varied from pale yellow-ochre, to bronze, brown, and grey; most were variations thereof. In addition, mating and birthing were observed at times to result in a sudden, and at times extreme, colour change.

3.2.3. Females

Female blacktip reef sharks identified as residents exhibited pronounced fidelity to their core ranges, to the extent that it was frequently possible to find a particular individual by going to her range and submerging. Each individual pursued her own roaming pattern. Some, exemplified by #3, were absent for approximately two weeks during mating and another two weeks for parturition, while another, exemplified by #15, displayed absences of up to three months during the period of reproduction between September and April (Porcher 2005). Other females exhibited absences along a continuum within this range, with most departures aligning with the reproductive season. Nonetheless, additional absences occurred outside this period, as well as sightings of rarely seen female blacktips, alone, in dyads, or groups of up to six individuals, traversing the study area. No consistent behavioural ‘type’ (Jacoby et al., 2014) emerged since each female followed her own movement pattern.

Their daily behavioural routines also displayed substantial variability. Some individuals, for example, repeatedly navigated the same coral formations at nearly identical times on successive evenings for multiple nights, before remaining absent from the area for an extended period, as much as a year. There were days when all resident females were absent from their ranges, contrasted with occasions when they assembled to interact with groups of infrequent transients. On most days at midday the resident females were resting in the barren region between Sections A and B (Porcher 2023a) while, occasionally, no reef blacktips were found there at midday.

3.2.4. Juveniles

Small juvenile blacktips were frequently observed at both Sites A and B, a pattern not observed among adults. Juveniles that encountered the feeding sessions in Section A and attended regularly, soon became attuned to the sessions when they were held at Site B, presumably due to the scent plume from Site B dispersing through the dense coral region of Section B, where they predominantly resided.

Across all categories, the greatest proportion of individuals consisted of those sighted only once. Unexpectedly, among juveniles, it was the smallest, the pups, who exhibited the highest percentage of individuals sighted once, or for a short period only. Throughout the study, a consistent stream of the smallest juveniles was observed traversing the area, with no subsequent re-sightings. Whether these individuals died or settled elsewhere—and the extent of their dispersal—remained unknown. Only two (#29 and #36), initially identified as juveniles passing through, were later re-sighted as subadults, at which time they established residency in the region.

Given the research emphasis on identifying adults, coupled with the pups’ tendency to remain beyond visual range due to their elevated vigilance, the definitively-identified pups represent merely a small subset of their true numbers. Initially, 581 blacktip reef sharks were identified; however, individuals insufficiently documented for reliable future recognition and never re-sighted were excluded from the dataset, reducing the confirmed number of uniquely identifiable sharks to 475. A large fraction of the excluded individuals consisted of pups observed only once within the study area, indicating that their actual abundance significantly exceeded the recorded figures.

3.2.5. Periodic and Rare Transients

While many transients were solitary, they also arrived in dyads or small groups of up to six individuals. As a rule, there was much high-velocity interaction on their arrival. Residents and transients would accelerate through the coral habitat surrounding the feeding site, following each other and moving nose-to-tail or in parallel (Porcher, 2023a).

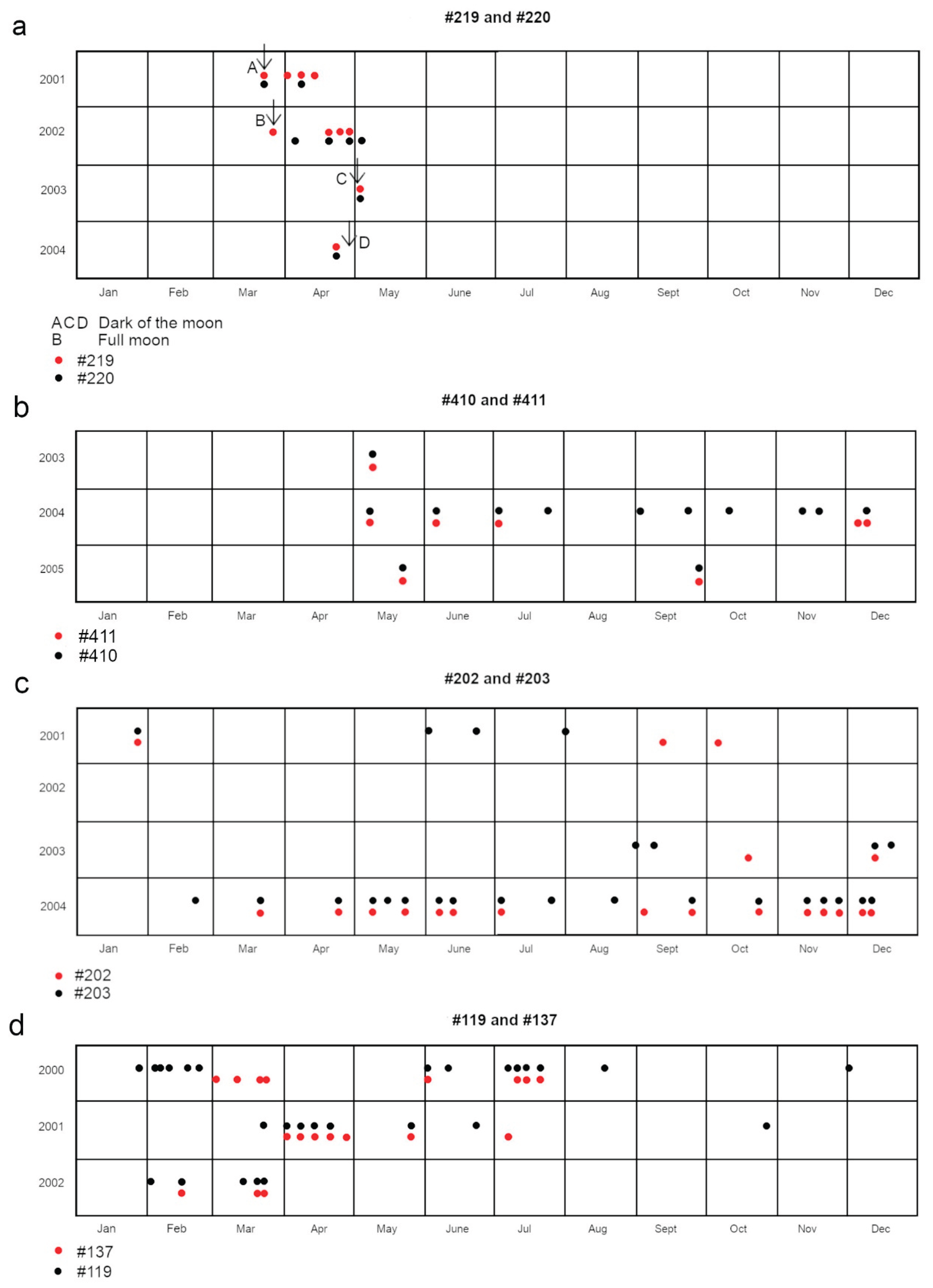

The arrival of these transient groups frequently aligned with the light and dark phases of the lunar cycle, with groups typically lingering in the area until the next lunar phase transition—approximately two weeks—before leaving. On several occasions, certain female residents temporarily departed their core ranges to accompany these departing groups of conspecifics along the back reef. Their behaviour underscored the species’ inclination toward socialization (Mourier et al. 2012) and affinity for interactions with many of the female transients.

Some of the transient groups of females were consistently accompanied by a single male, the same one each time, who invariably entered the observation site one to two minutes ahead of the females.

Rare female transients moving through for parturition often displayed a pattern of annual return within a few days of the previous year’s date.

Since resident females were not systematically observed together because of their circling movement patterns (Porcher, 2023a) the movements of consistent travelling companions were most discernible among rare transients who maintained the same associates across multiple years.

3.3. Influences on Blacktip Reef Shark Movements

The primary influences on the blacktip reef sharks’ movements were the reproductive season and the lunar cycle.

3.3.1. The Reproductive SEASON

The reproductive period commenced in September, marked by previously unidentified and infrequently observed gravid female blacktip reef sharks traversing the study area. New unidentified females passing through at this time were documented throughout the study. Concurrently, resident females approached parturition, subsequently returning after an absence in an emaciated state.

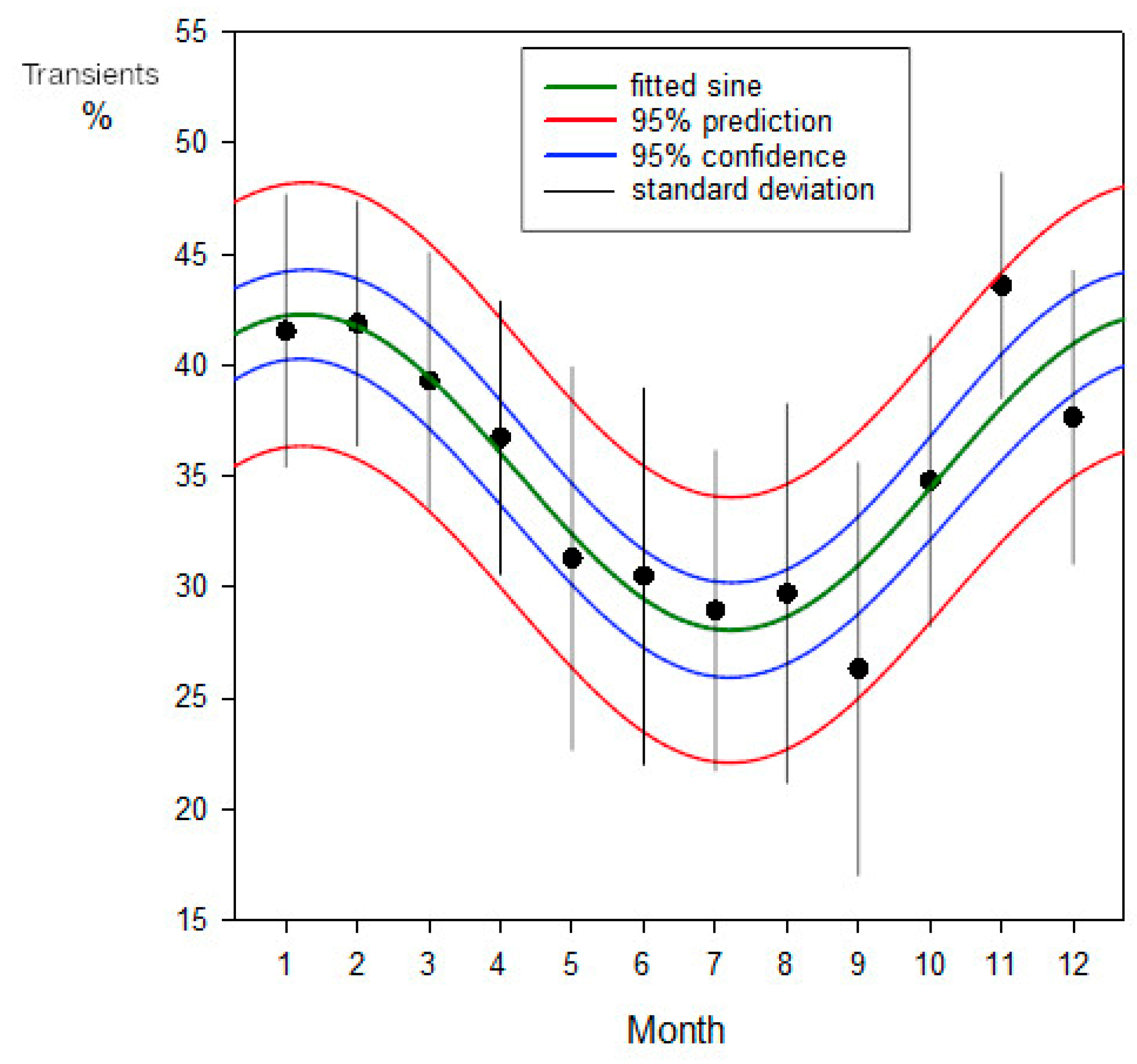

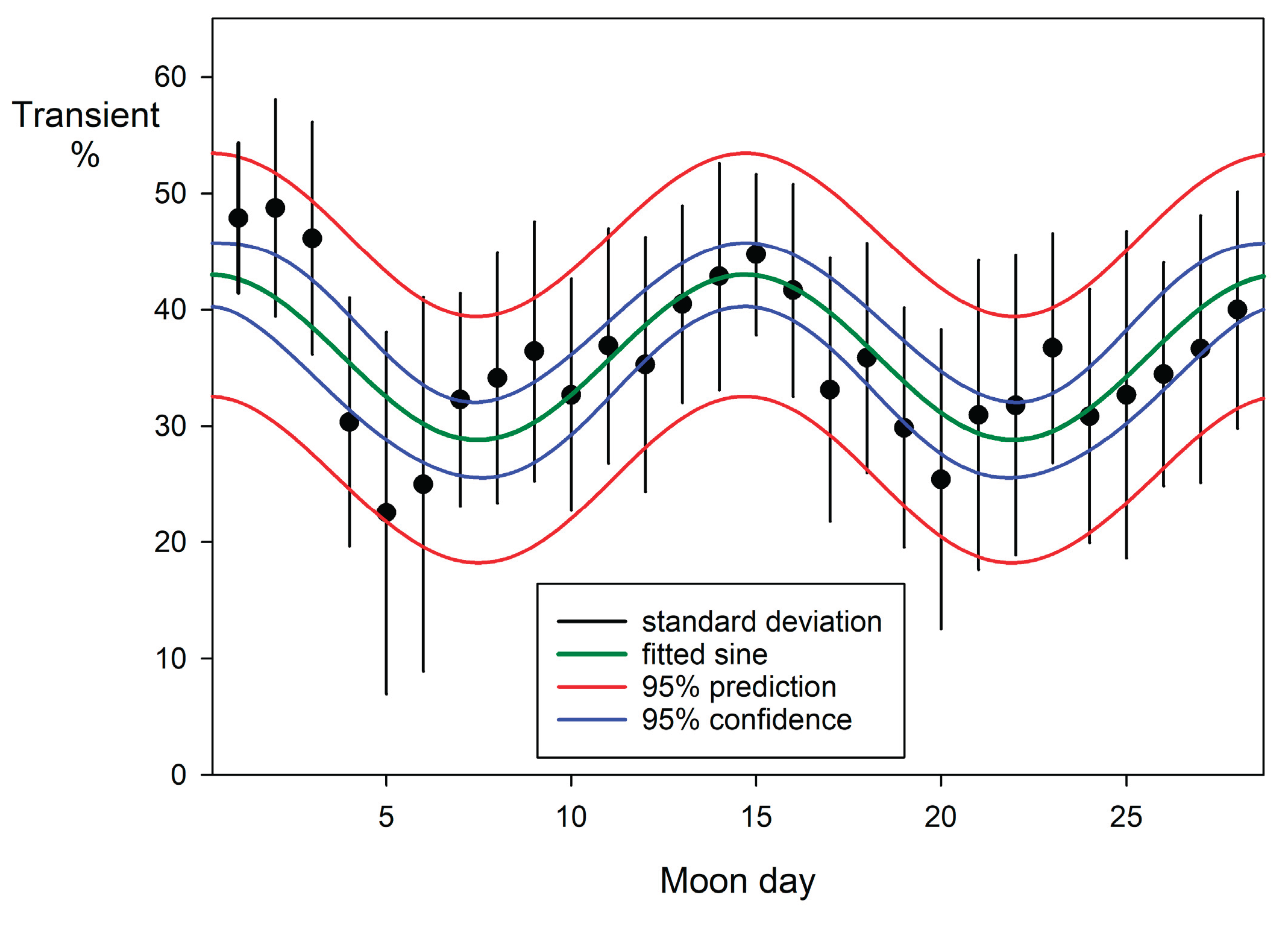

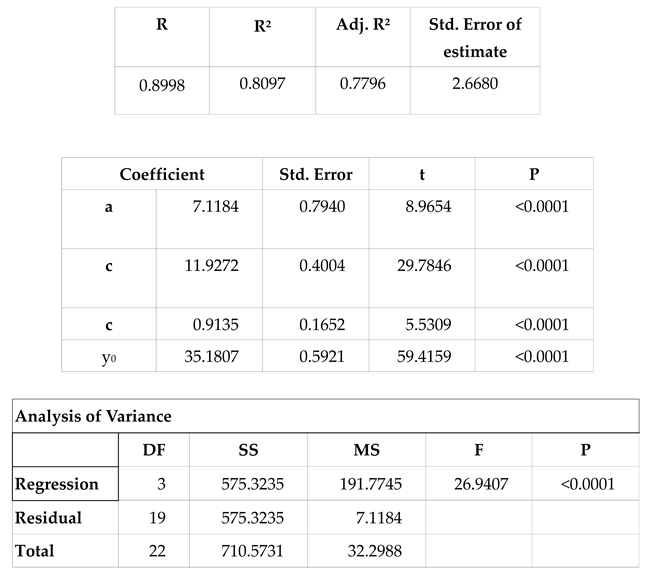

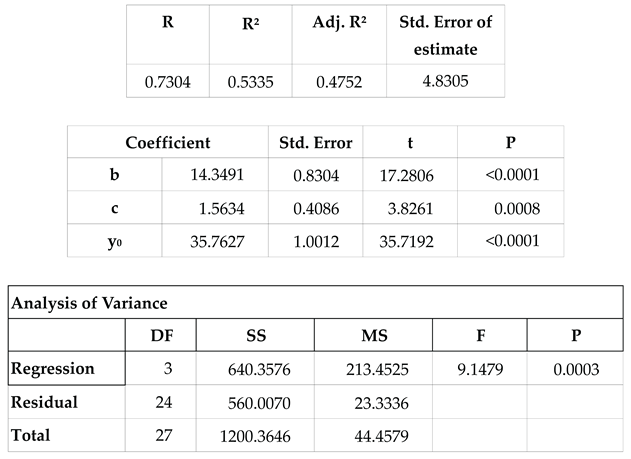

After a resting period of 1.5 to 2 months, each resident female began to appear with mating wounds, while groups of males were observed arriving in the lagoon after sunset. These males, observed exclusively during the mating season, were presumed to inhabit the fore reef, consistent with the majority of male conspecifics. Consequently, the reproductive season emerged as a period of heightened mobility for the species. An analysis of the percentage of adult blacktip transients present at the observation sessions during the period of regular sessions between 1999-04-11 and 2002-05-11 in Section A (247 sessions) is shown in

Figure 12. This used unweighted non-linear regression, treating the frequencies as binomial (SigmaPlot v16; Grafiti, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The calculation is shown in

Table 3.

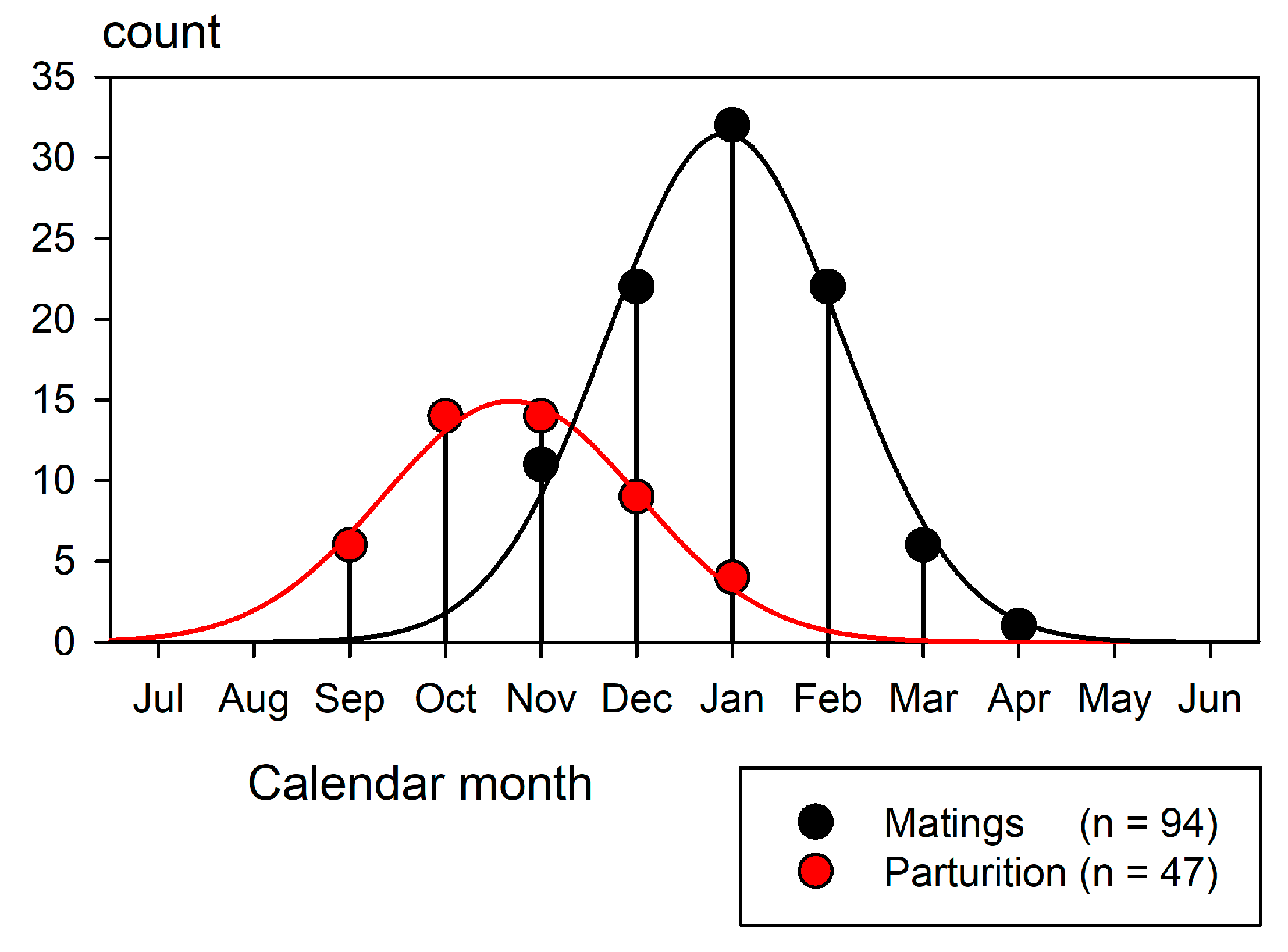

Mating begins in November and continues until the end of March as each female follows her own temporal cycle (Porcher 2005). Parturition begins in September and continues until January. Each female again mates 1.5 to 2.5 months after parturition, thus completing an annual reproductive cycle. All resident sharks under observation followed this pattern. Evidence of reproductive events presented by transient females conformed with the pattern of the residents.

Figure 13 shows mating and parturition recorded in each month (Porcher, 2005).

A comparison with

Figure 12 illustrates the impact of the reproductive season on the blacktips’ movement patterns. A substantial portion of their travels were driven by this powerful instinctual imperative.

3.3.2. The Lunar Phase

The movement patterns of blacktip reef sharks with respect to the lunar day were analysed in similar fashion to the monthly data above. A notable correlation with lunar phase (

Table 4,

Figure 14) was exhibited, as evidenced by the numbers of transients recorded at feeding sessions across each lunar day. Peaks occurred at both new and full moon.

3.3.3. Unusual Sessions

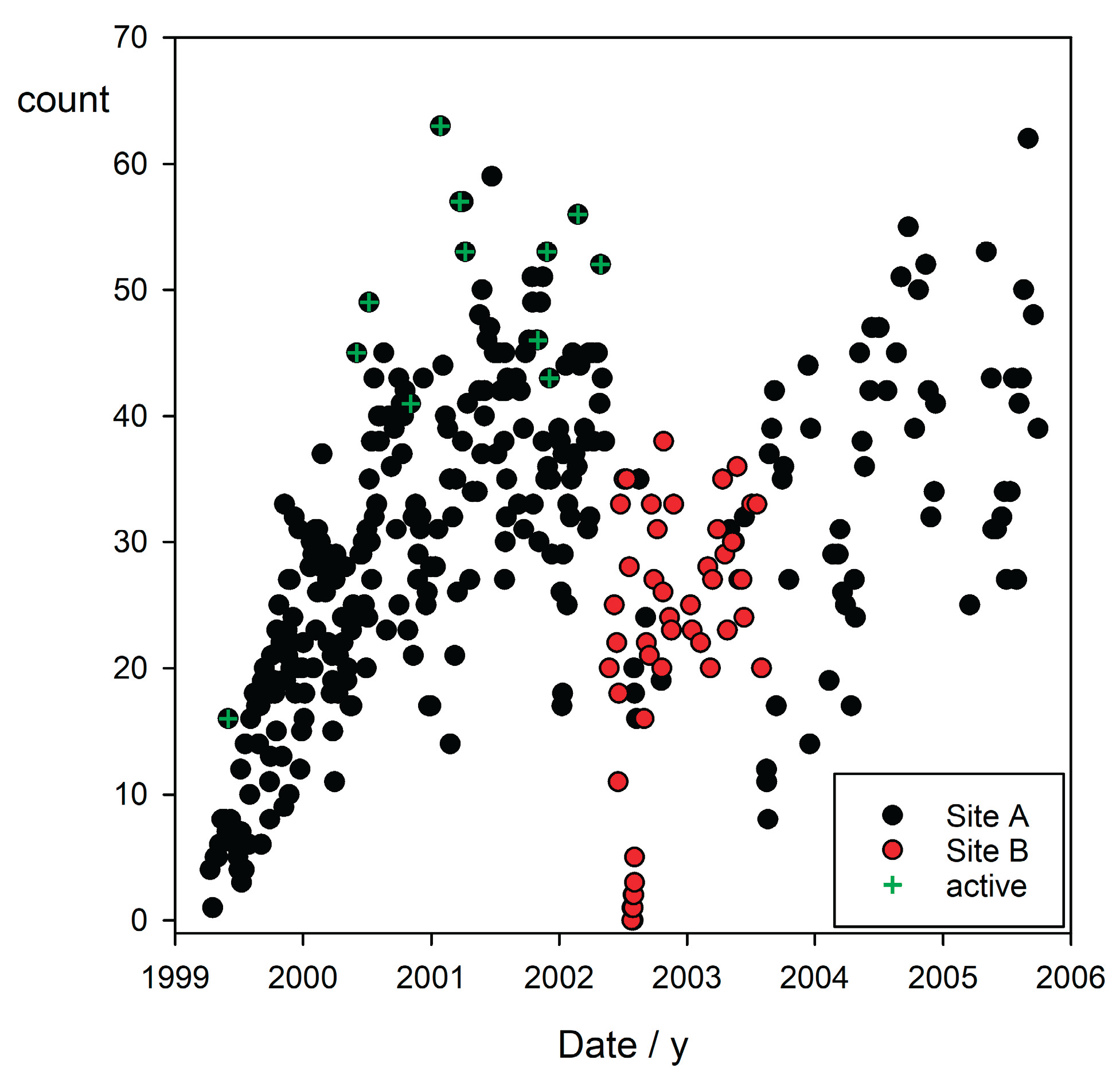

A distinct pattern emerged from sessions that deviated from the usual. These occurred sporadically with intervals of many months. Only 12 such sessions were documented during the 6.5-year study (

Figure 2), with nearly all correlating with the full moon and the dark lunar phase. These sessions attracted up to twice the usual number of blacktip reef sharks, and were distinguished by a high proportion of infrequent transients. They were characterized by social interactions featuring high-velocity, synchronized movements throughout the area (Porcher, 2023a). Conversely, during certain full moon phases, an opposing trend occasionally emerged, marked by the absence of the resident females. Only juveniles and one or two lagoon-dwelling males attended.

Of these unusual sessions, six (50 % of the total 12) coincided with the full moon. One such session saw the arrival of two groups of rare transients, including individuals #219 and #220, as well as #119 and #137 (

Figure 11). Four sessions (33 %) occurred during the dark lunar phase, while the remaining two (17 %) took place when the moon was 42 % illuminated (lunar day 7), on 00/07/07/ and 00/11/03. The latter session was notable for the appearance of the Papetoai resident female (#179), marking one of her two recorded visits to Section A. A rare periodic male transient (#103), present in the area solely during November and December, was also observed at this session and during #179’s second documented appearance in Section A.

An intriguing associated observation involved the presence of a lemon shark (Negaprion acutidens) at six sessions over the 6.5-year study period. Four of these occurrences aligned with the full moon, while the remaining two coincided with the dark lunar phase (new moon). This species infrequently entered the back reef; juvenile blacktips use those shallow waters as a refuge from such large predators.

3.3.4. Other Influences

During storm events, increased oceanic swell transformed the lagoon into a dynamic, riverine environment. Gravid female blacktips, particularly larger individuals, exhibited reduced manoeuvrability in strong currents, necessitating substantial energy expenditure to navigate the complex coral reef environment under turbulent conditions. Consequently, a significant proportion of these females vacated the lagoon during such events, possibly seeking refuge in the deeper waters adjacent to the fore reef. In contrast, the smallest juvenile sharks, characterized by a streamlined morphology and the highest surface-to-volume ratio, demonstrated greater ease in navigating turbulent conditions. Despite their much smaller body size, their caudal fins were comparable in size to those of the heavy-set females, facilitating efficient propulsion through the environment during periods of high turbulence. These juveniles also possessed a stronger tendency to remain within the protective shallows.

Under calm conditions, the average attendance of adult sharks across 149 sessions was ~24. In contrast, during 41 sessions marked by adverse conditions, the average adult attendance dropped to ~18. Notably, in more extreme conditions, adult female attendance was nearly absent, with only a few juveniles present.

In August 2003, when a Singapore-based company began finning the reef sharks, those not immediately killed fled the area. Though some returned within ten days, most took more than two weeks to return, and some did not reappear in their core ranges until the same period of the following lunar cycle. As a result of this tendency and the ongoing slaughter that removed all the elderly females, and nearly every mature blacktip under observation, the shark communities originally observed never returned to their former state. By the time international pressure won their protection in 2006, the population of the back reef consisted of juveniles. (The adults were believed to leave the back reef and roam the ocean at night [Richard Johnson, pers. comm.] where they were vulnerable to fishing vessels but evidently the juveniles did not, for they alone survived). The reef sharks inhabiting the waters on some of the islands in Polynesia were completely fished out, while observers in the wilder parts of the island nation reported countless vessels laden with drying shark fins.

A further unidentified influence resulted in the evacuation of all the blacktips under human observation on Mo’orea Island between July 23 and August 5, 2002 (Porcher, 2023b), including the smallest pups from their shallow coral refuges. In spite of extensive investigation, no reason for their disappearance was found.