1. Introduction

Over the years, there has been a focused and concerted research effort to increase the yield of rice to meet the energy requirement of the billions of rice consumers. The focus has always been on rice, with little attention paid to the rice farmers themselves.

In this paper, we inquire about the aspirations of Filipino rice farmers. Aspirations help people direct life trajectories toward a desired future [

1]. Aspirations are goals individuals are willing to invest time, effort, or money into to attain.

Looking at aspirations is important as aspirations provide directions that people are willing to invest their time and resources. By looking at the aspirations of Filipino rice farmers, we are able to see their dreams, which are indicative of the effort that they are willing to put on to achieve. Hence, doing this research has an instrumental aim as this will enable policymakers to align their efforts to assist farmers. Aspirations are an important element to consider success in agricultural endeavors yet they are seldom asked. For example, the level of aspirations of farmers must be asked before any moves relating to relocating and subdividing farms [

10].

There is a considerable amount of literature on farmers’ aspirations. In general, scholars have worked in-depth on the factors that influence farmers’ aspirations. For example, joining cooperatives, being educated, and owning vast resources are linked to having high aspirations [

7]. These farmers are said to think big and have ideal visions in relation to farming. On the other hand, poor access to resources, and low educational attainment are linked to having low aspirations [

6]. A number of scholars also point that farmers’ experience of shock such as climate extremes is also likely to influence their level of aspirations [

3].

In looking at the aspirations of farmers, a review covering developing countries including India, Morocco, Burkina Faso, and the Philippines reports several interesting findings. Among these findings is the fact that the aspirations of the government, in general, do not align with the aspirations of farmers [

8]. A study by [

9] reported that farmers do not always want their children to be like them. Scholars have also reported on the rather lower aspirations of women as compared to men [

8].

Within the web of literature are recommendations on how to create an environment that encourages positive and high aspirations. Among these recommendations are addressing issues relating to material barriers such as access to credit and water.

Overall, there is a good representation of both the Global North and South, more of the South, in the literature. Southeast Asia, however, is not well-represented in the sources of knowledge in the articles reviewed. Only a few studies from Indonesia and the Philippines have been retrieved. The case for Southeast Asia is being made because this region produces a significant volume of rice that is being traded in the global market. Some gaps noted in the literature are underutilization of qualitative methodologies. This is an important point considering that aspiration is a variable that can be best explored using qualitative techniques. It is also worth noting that there is a dearth of literature that scrutinizes the farmers’ aspirations vis-a-vis the organization that pledges to assist them. This line of inquiry is important as alignment in aspirations would ensure that farmers are properly assisted and that the organization tasked to provide services to farmers fulfill its mandate.

The overarching research question of this paper is: What are the aspirations of the Filipino rice farmer? The specific research question is: What are the aspirations of rice farmers for their community, family, and self?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This research is guided by the Role Theory, specifically the Role Identity Theory. Broadly, roles are a set of behavioural expectations that define a group or a person [

5]. For roles to be recognized, there has to be some following of accepted norms of behaviour [

2]. Role Identity Theory “contends that individuals act based on how they like to see themselves and how they like to be seen by others when operating in particular social positions” [

2]. For example, in the context of this research, a farmer is likely to be expected to be good at growing crops and that s/he employs sustainable agricultural practices. This means that the way individuals see themselves impacts their interaction with others. In the context of this research, if a farmer wants to be seen as a good farmer, then s/he is likely to employ practices that are generally accepted to be good such as maintaining well-leveled and weed-free paddies, or, perhaps, avoiding wasteful use of water. In this case, roles appear to shape an individual’s identity. The Role Identity Theory includes “individual’s goals, values, beliefs, norms, interaction styles and time horizons that comprise a particular role” [

2].

An important concept under the role theory is role salience, which pertains to the “readiness to act out an identity as a consequence of the identity's properties as a cognitive structure or scheme” [

2]. In the context of this study, this pertains to the farmers’ desire to act out their identity as farmers through their aspirations on how to improve their rice cultivation venture. Farmers, however, at the end of the day, are not just farmers. They are at the same time parents, members of a family or a community. These roles have attached behavioral norms as well. Hence, it can be said that farmers carry multiple roles at the same time. With this, the concept of “role accumulation” becomes relevant. Role accumulation pertains to “obtaining and occupying certain roles at once” and the “benefits” of having multiple roles [

2]. Given that the farmers play multiple roles all at the same time, the concept of role transitions, specifically micro role transitions, becomes relevant. Micro role transitions refer to the movements in between roles that are being played at the same time [

2]. In the literature, it is said that one’s identity influences the way an individual deals with micro-role transitions. For example, if being a good farmer is more important to a farmer than being a community member, then s/he is likely to have more conflict transitioning from being a farmer to being a community member and vice-versa.

2.2. Methodology

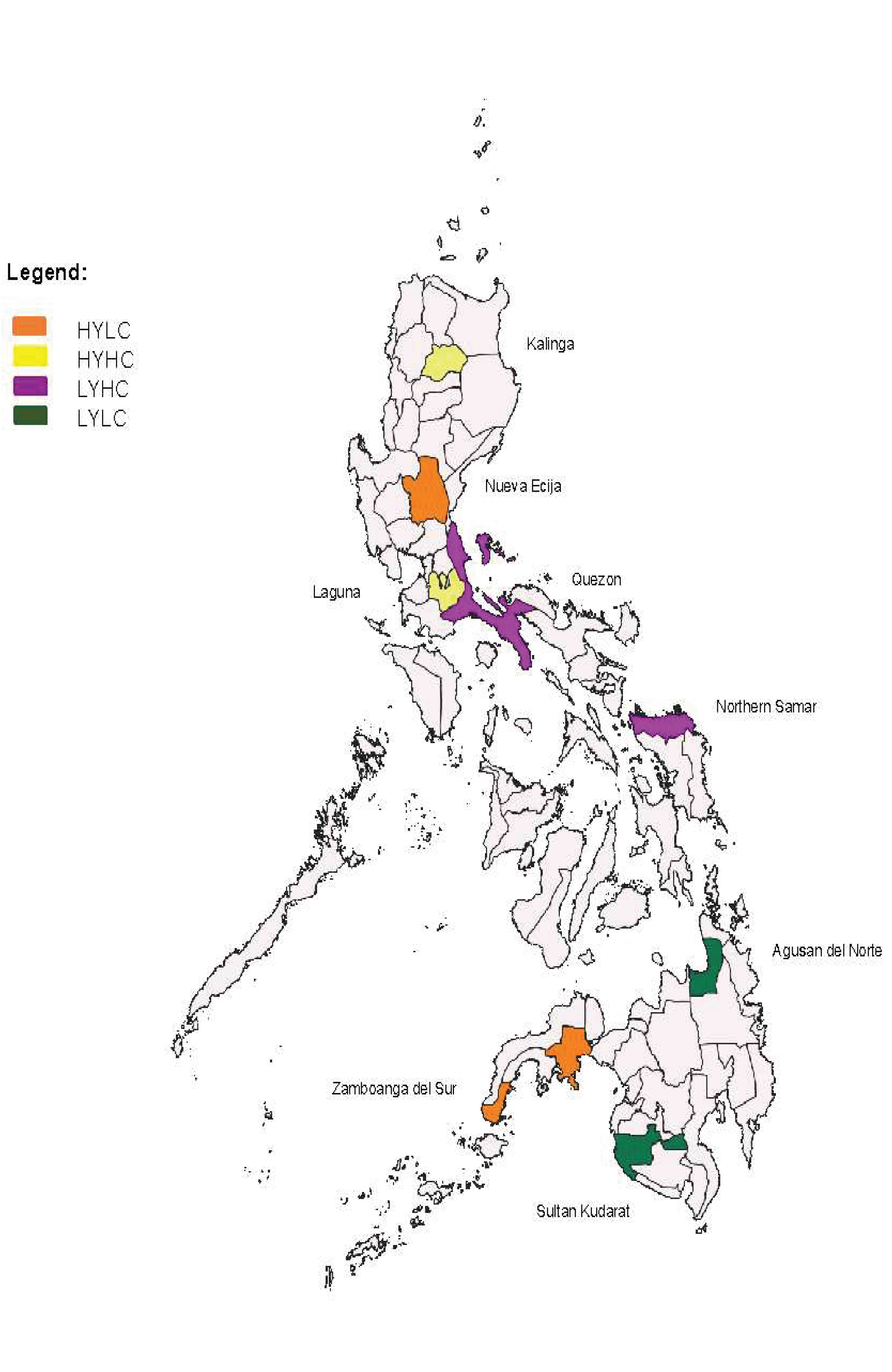

This research was predominantly qualitative using focus group discussion as the main method of data collection. We conducted 64 focus group discussions consisting of 315 farmers and 58 key informant interviews through face-to-face and virtual means (provincial agriculturist officers, municipal agriculturist officers, local government units, and rice coordinator/focal person: provincial and municipal). The interviews ranged from 1 to 2 hours and used online applications like Zoom and Google Meet and phone calls. We had the following groups for the FGD: Progressive farmers [Men only; Women only] and Resource-poor farmers [Men only; Women only] of farmers which were selected based on the recommendations of the gatekeepers. Men and women were separated so they could better share their stories as usually, women farmers do not share much information when mixed with men farmers and vice-versa. Resource-poor and progressive farmers were selected based on their annual per capita poverty threshold and poverty incidence among families (PSA, 2021): Kalinga (PhP 25,447), Nueva Ecija (PhP 29,751), Laguna (PhP 29,892), Quezon (PhP 27,151), Northern Samar (PhP 26,572), Zamboanga del Sur (PhP 24,066), Sultan Kudarat (PhP 25,295), and Agusan del Norte (PhP 27,722).

We relied on the recommendations of the offices of the Municipal Agriculturist in recruiting the participants for this study. The questions in the FGD revolved around the aspirations of the farmers for their community, self, and families; entities that could help them reach their aspirations; and farming-related issues; overall likelihood to pursue the agriculture track for their respective communities.

Figure 1

Data collection was conducted from 8 September 2022 to 11 November 2022. We developed a coding guide to facilitate the coding process to ensure reliability in the analysis. In developing the coding guide, we first read the transcripts to identify the themes running across the interviews. Each transcript was read and coded by at least two of the authors. A workshop was held to deliberate on coding disagreements. We did informal member-checking, which was a research validity measure. Below are the final codes that we used in this paper:

Farming-related Aspirations with definitions:

Capability building – consists of various training programs (e.g. Palaycheck, vegetable and livestock production, mind setting and values restoration, and organization building)

Fair Price - aspirations of farmers for higher paddy prices and lower production costs

Food sufficiency and food security - aspirations of farmers to produce, achieve food sufficiency and security, and export rice.

Government support and good governance - aspirations of farmers for the government to continuously, increasingly, and strategically provide all the support that they need (e.g. fertilizer, seeds, programs with a sustainability plan)

Infrastructure development - aspirations of farmers for access/ improvement of irrigation facilities and establishment/improvement of drainage facilities, farm-to-market roads to their farms so that more traders can reach their areas and also decrease their hauling and transportation costs.

Legacy - aspirations of farmers to fellow farmers for them to leave their own legacy.

Love, passion, peace and order, and unity - aspirations for every farmer and leader of associations and cooperatives in farming and to realize peace and order in their communities.

Progress - aspirations of farmers to achieve progress through farming.

Farm Assets - aspirations of farmers to own or have access to farm equipment, animal power, and postharvest facilities via their associations, to acquire property including car, house, and land through farming.

General-related Aspirations with definitions:

Education - aspirations of farmers for their children to finish tertiary education in their chosen career track.

Fair Price - aspirations of farmers for lower prices of commodities such as medicines, meat products, and poultry.

Government support and good governance - aspirations of farmers for their local leaders to be more proactive in building public-private partnerships benefitting agriculture, business, retirement programs, and other sectors.

Infrastructure development - aspirations of farmers to have access to state-of-the-art public infrastructure such as clinics, pharmacies, senior centers, schools, and roads.

Wellness and long life - aspirations of farmers to have good health and long life to witness their family and children progress and succeed.

Love, passion, peace and order, and unity - aspirations of farmers for their communities, leaders, and families to stay united and be motivated by love, passion, and peace rather than political or financial interests.

Progress - Aspirations of farmers to improve their lives in terms of their economic and social status.

Property and other Assets - Aspirations of farmers to acquire property including cars, houses, and land through other means than farming.

3. Results

3.1. Aspirations for the community

Community aspirations are ambitions that they want to see in their neighborhood, barangay (village), municipality/city, or society. As regards farming-related aspirations, property, fair price, infrastructure, government support, and good governance were the top aspirations of farmers. As regards fair prices, farmers basically want to have control in setting the prices. They see that most of their issues gravitate around unjust prices for their produce. This theme was seen in different FGD groups:

“For us to have control over the price of paddy”- Zamboanga del Sur, women only

“Better price of paddy because the price of basic commodities are also on the rise”- Northern Samar, men only

“We hope that the price of gasoline will go down. When farmers harvest, the price is really low. Yet, there’s a price hike of all basic commodities”- Sultan Kudarat, men only.

As regards government support and governance, the participants mentioned several areas where they want the government to be more visible. They want more subsidies for seeds and fertilizers and farm inputs in general. For them, more subsidies mean they would be able to continue with their farming ventures:

“We need seeds and fertilizer support”-Agusan del Norte, men only

“We need more jobs for agriculture graduates. It is usually difficult to find jobs for agriculture graduates”- Kalinga, women only.

This research also captured the general aspirations of farmers or those aspirations that do not necessarily relate to agriculture. The top aspirations relate to infrastructure development, progress, and government support and governance. Farmers dream of having well-built social development infrastructure such as cemented roads; accessible schools, pharmacies, markets, and clinics. This is captured in the quotes below:

“It would be nice if there would more public infrastructure such as gyms, schools, and health centers” –Kalinga, men only

“Paved roads because now, they are not!” –Sultan Kudarat, women only

“We need to pave and properly maintain our roads to prevent accidents. We also need a farm-to-market road.” –Sultan Kudarat, women only.

Perhaps, similar to most of humanity, farmers dream of progress, which largely relates to improving their overall socioeconomic status. They reported a range of aspirations such as having a clean environment, being financially stable, expanding their farm, and acquiring machines.

“Farmers are rich! Their living condition is significantly improved. The whole town is very progressive.” – Agusan del Norte, women only

“We need our town to develop. Now, we have cleanliness and water issues.”- Kalinga, men only.

Looking to the future, farmers aspire to receive retirement assistance, and overall assistance to people even those who are not into agriculture. They dream of a more efficient implementation of government programs.

3.2. Aspirations for the family

Farmers have aspirations for their families. The farming-related aspirations include education, government support, and farm mechanization. Just like most parents, farmers aspire for their children to have access to quality education, good schools, competent teachers, and modern teaching methods and practical skills. This observation emerged in Kalinga, Zamboanga del Sur, Northern Samar, and Sultan Kudarat. Farmers in Quezon were quite explicit in saying that they needed educational scholarships for their children. Farmers also aspire to receive more support for their children. They see their children as their way out of poverty due to years of farming. If their children are educated, then it increases their life chances, i.e., to achieve long-term success, not just in farming but in life in general. The quote below sums up this observation:

“We want our children to have jobs so they could help in paying our debts.” -Sultan Kudarat, men only.

Farmers have diverse aspirations when it comes to ownership and expansion of land and prioritization of mechanized farming systems. Owning land provides a sense of stability, long-term investment, and the ability to pass down the land to future generations.

“We hope that rice fields will be bigger and that our harvest will increase! –Nueva Ecija, men only

“We hope that someday the land we till will be ours.”- Nueva Ecija, women only.

Those who prioritize mechanization, seek to invest in machines that can increase efficiency and productivity, such as harvesters, tractors, rotavators, and irrigation systems. Advanced mechanization, may help farmers reduce labor costs and expand their farming operations, which can lead to increased profitability and improved socioeconomic status. Outside the farming realm, farmers report aspirations relating to love, passion, peace, and unity; wellness and long life, and education. Farmers, like everyone else, desire love, passion, peace, and unity within their families. By prioritizing these aspirations and taking intentional steps to achieve them, farmers see them as a way to create a loving, passionate, peaceful, and unified family environment that supports their personal and professional goals.

“No relatives or family members who are at odds with each other.” -Nueva Ecija, women only

“We hope that we would always understand each other and that no one will get sick in the family.” –Kalinga, men only

Living a long and full life is on top of farmers’ aspirations for their families. For them, it is important that they are fine mentally and physically so they can better manage their farms. Rest is also very important for them. This point is well captured in the “Buo ang pamilya at malakas na pangangatawan” point of the men and women farmers in Zamboanga del Norte and Northern Samar.

Farmers have big dreams for their children’s education. They aspire for them to be successful in their chosen field. If they own land that they till, they would want at least one of their children to study agriculture. Otherwise, they sometimes wish for their children to get into fields other than agriculture so that they would not have to endure the hardships they had with farming.

”I hope that my grandchildren will finish college.”-Agusan del Norte, women only

“I hope that I can provide a good education to my children. I hope that they will get courses like engineering, criminology, nursing, midwifery, and law” -Kalinga, men only

3.3. Aspirations for self

Farmers report various aspirations for themselves. These aspirations relate to having farm assets, improving their overall socioeconomic status, and achieving a life filled with love, peace, passion, and unity. Similar to their aspirations for their families, farmers dream of acquiring farm assets their farming operations. Women farmers from Agusan del Norte reported their dream of acquiring tractors and an elf.

From the interviews, farmers reported of their dream of securing themselves and their livelihood. Lastly, farmers aspire to live their lives filled with love, peace and order, and to be in the position to help others with the fruits of their labor from farming, be it their relatives, workers, or other people in general.

“We hope that we could continue supporting our families, especially our grandchildren.” – Northern Samar, men only

“I hope that I could help our caretaker in maintaining the rice field.” – Agusan del Norte, women only

“Give more service to humanity.” – Kalinga, women only

As for their aspirations that may or may not be directly related to farming, they reported of their desire to be rich. It is worth noting that farmers aspire to be rich and that they see the government as central to them achieving it.

“I hope that I could be rich someday because the government has prioritized agriculture.” -Nothern Samar, women only

“I want to be a billionaire!” –Kalinga, men only.

3.4. Aspirations based on yield and cost categories

Below, the provinces are sorted into four categories of yield and cost of production per kilogram, which are benchmarked according to the Rice-Based Farm Household Survey (RBFHS) results in 2017 where the national average yield was noted at 4.12 t/ha and the average cost of production at PhP 13.04/kg. Yield-cost categories were created based on whether the provincial statistics went above or below these figures. The following yield-cost categories (

Table 1) are high yield, high cost (HYHC) which includes Kalinga and Laguna; high yield, low cost (HYLC) which includes Nueva Ecija and Zamboanga del Sur; low yield, high cost (LYHC) covering Northern Samar and Quezon; and low yield, low cost (LYLC) covering Agusan del Norte and Sultan Kudarat. The aspirations mentioned above are analyzed accordingly, and it shows that the aspirations at the levels of community, family, and self are shared aspirations across all yield-cost categories.

Table 1

Based on the data, there is evidence that while some farmers aspire to continue farming, some farmers desire to disengage from rice farming. This is generally observed in all yield-cost categories but HYLC. A favorable interpretation of this is it is possible that experiencing the most ideal yield-cost combination, the gains are enough motivation to keep pursuing rice cultivation. In Nueva Ecija, access to services was not reflected as a priority aspiration. This may be attributed to the abundance of these in the province owing to being the rice granary of the country and the central base of several agricultural research agencies such as PhilRice, PhilMech, and the Central Luzon State University.

Among the high-yield provinces, the aspiration for further research and technological advancement is palpable. This behavior is likely a result of having good yield outcomes. On the flip side, this could also be interpreted as not having well enough in terms of prioritizing farmers’ needs for economic and social security. In the ultimate goal of achieving high yields, those with large farms should not be set aside and should also be given assistance such as cash aids.

“Kaming malalaki hindi nakakatanggap ng mga ayuda tulad ng mga cash aid samantalang kami yung maraming naaambag sa production. - Nueva Ecija, progressive women only

Low-yield provinces, on the other hand, are identified with agro-enterprise and organic farming-related aspirations. This is made evident by their aspiration to have an integrated farm as a sustainable option for food supply at the level of family and self.

3.5. Aspirations based on sociodemographic factors

In general, the aspirations remain shared by the farmers regardless of resource capacity and gender, i.e., being progressive (P) or resource-poor (RP), and man (M) or woman (W), respectively. Notable comparisons are observed when the two identified sexes are contrasted by resource capacity, i.e., PM vs RPM, instead of by gender alone or by resource capacity alone, e.g. P vs RP, or M vs W. This suggests that farmers generally have the same aspirations but their differences in economic capacities influence their ability to attain these.

3.6. Figures and Tables

Figure 1.

Eight provinces in the Philippines denoting different yield and cost levels.

Figure 1.

Eight provinces in the Philippines denoting different yield and cost levels.

Table 1.

Overall Aspirations of Farmers and Key Informants disaggregated by yield and cost categories.

Table 1.

Overall Aspirations of Farmers and Key Informants disaggregated by yield and cost categories.

| List of Aspirations |

HYHC |

HYLC |

LYHC |

LYLC |

| Capability building |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Education |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Fair Price |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Food sufficiency and food security |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Government support and good governance |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Infrastructure development |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Legacy, wellness and long life |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Love, passion, peace and order, and unity |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Progress |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Farm assets |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Reach higher social status |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

4. Discussion

Access to services and higher income from rice farming were observed to be more palpable among RPW than among the PW and equally professed by RPM and PM. During the data collection, particularly in Sultan Kudarat, the RPW was noticed to be more burdened with working multiple agricultural labors than the PW when it is difficult to make ends meet; in part due to the terrain of their farms being located nearer the mountains. In addition, they engaged in small entrepreneurial endeavors, such as cooking local delicacies to be sold as snacks in schools, and aspired for sari-sari stores, which they perceived would be able to get them by daily. Conversely, the aspiration of passing a farming legacy is observed among the PW rather than among the RPW. The recent findings of [

4], in behavioural sciences suggest that individuals may engage more in pro-social behaviour if they are prompted to reflect on how they will be remembered. Related to this, there is another form of legacy that the farmers aspire to see fulfilled – the legacy of values. In our interviews, this sentiment was strongest among the RPM.

Among the men, the PM was noted to have more propensity towards aspiring diversified farming and leisure travel as opposed to the RPM. This finding relates to the concept of aspirations failure where it is said that those who have more resources have higher and varied dreams as opposed to those who do not [

9]. On the aspect of diversified farming, in general, during the data collection, the women were found to be keener on investing in planting other crops while the men were found to be more explorative of livestock options, unless the crop options were high-value crops requiring more physical labor, such as the management of palm tree groves.

What the findings above mean is that it lends support to the view in the literature that aspirations are indeed gendered and resource-dependent if seen from the individual level.

This overall observation, however, changes when seen from the level of the community and family. Based on the identified sociodemographic indicators with the results analyzed at the levels of community and family, it can be noticed that resource capacity and gender are almost negligible when in the farmers’ aspirations for the community. This finding at some point disagrees with the finding of [

9] saying that women have lower aspirations than men. This is a welcome contribution to the literature. It shows that if the aspiration discourse reaches the community level, gender, based on this study, becomes an insignificant concern.

Farm assets, fair prices, government support, capability building, infrastructure development, and progress are the aspirations of farmers, regardless of socioeconomic standing, also at the community level. Similar to gender, this finding also does not sit well with the concept of aspirations failure, which speaks that those who have fewer resources tend to have lesser aspirations. Our findings show that this is not the case. Additionally, this, too, is an important contribution to the aspirations literature, which tends to dichotomize the haves and have-nots. Our findings show that at the community level, the capacity to dream is not limited by level of resources a community has.

The general aspirations for the family are also neither gendered nor based on the abundance of resources. However, the farming-related aspirations for families, which are identified as education, progress, government support and good governance, and farm assets, tend to be more, expectedly, independently accomplished by progressive farmers than resource-poor farmers.

It was found that there are more accountabilities among resource-poor farmers, regardless of gender, in sending their children and grandchildren to school compared to progressive farmers. Based on their narratives, it is perceived that the children of resource-poor farmers tend to have less security in employment, although there were also many success stories. Because of this, the farmers feel obliged to share in their children’s accountability to send their children, the farmers’ grandchildren, to school. Moving on to government support and good governance, the level of support aspired by the resource-poor farmers tends to move towards the sustainability of aid, whereas the aspirations of the progressive farmers are more of cash aid programs however, smallholder farmers are only qualified. On the noted farming-related aspirations for self, these are assessed to be generally gender-neutral because men and women both aspired to those aspirations.

When it comes to how aspirations are understood at the level of definition, according to [

9], aspirations are goals individuals are willing to invest time, effort, or money into to attain. Based on our analysis of the farming-related aspirations of the farmers across population levels (community, family, and self), yield-cost categories, and sociodemographic lenses, the aspirations we found may not be something that farmers themselves could sort out on their own. These are aspirations that require third-party intervention. For example, capability-building is dependent mostly on agricultural extension efforts with attendance and technology adoption as the commonly required counterparts from the farmers. The fair price is dependent on globally-linked economies and how market systems are set up. The loudest farming-related aspirations based on the data and as observed during the data collection are different ways of expressing one aspiration: for the government to invest more in the farmers. The definition of Nandi and Nedumaran is more applicable to the farmers’ general aspirations, especially at the level of family and self, which include love, passion, peace, and unity; wellness and long life; education; and food security.

Going back to the Role Identity Theory, the findings described above are completely understandable, especially if one were to talk about the roles of a good farmer. Their aspirations relating to fair price, government support on inputs and mechanization will all help them better express their identities as farmers. Similarly, the general aspirations of farmers either for themselves, family, or community, all speak of how they could better perform the roles attached to each. This speak of the “theater metaphor” in the role theory. It says that society becomes easily observable owing to the defined roles of every individual. For example, as part of their general aspirations to have better roads, improved infrastructure in general. These aspirations are expressions of their desire to improve their social context. In most of the focus groups, despite many unfavorable exchanges relating to their experiences in accessing government services, farmer-participants remained to have vibrant aspirations, both for farming and in general, and across levels, i.e. self, family, and in general. In the framework, this refers to the concept of role accumulation, which pertains to the benefits of having multiple roles. It was evident that farmers happily perform those roles—as a farmer, a parent, a son, a daughter, and as a member of their community. Hence, despite the various challenges that they experience, they maintain a strong disposition for the present and for the future.

At the outset, this current study has three major theoretical contributions. First, it puts in question the findings in past studies that aspirations are gendered, that men have higher aspirations than women. In this current study, aspirations are gender-neutral, especially at the community level. Second, it puts in question the concept of aspirations failure at the community level, which generally says that those who have more resources and are in an advantageous position tend to have higher aspirations. This, clearly, is not the case in this paper. We have shown that aspirations are not affected by the level of resources, and that dichotomizing is irrelevant when looking at aspirations. Third, this current study challenges the conceptualization of aspirations, from one which speaks of aspirations as goals, plans that one is interested to invest in for them to be achieved. What we have shown is that aspirations take different forms, and among them are those that relate to a third party for it to be realized.

5. Conclusions

Aspirations are gendered and/or resource-dependent at the individual level. This study supports the concept of aspiration failure, also at the individual level. The story, however, changes if aspirations are analyzed at the level of family and community where we found that aspirations are neither gendered nor resource-dependent.

Moving on, what our findings say is that we should pay attention to the aspirations of farmers, farming-related or general, as this will result in far more successful engagement. We have shown that contrary to how the literature understands aspirations, farmers have aspirations that need a third party for them to be realized. While there are many aspirations noted, we wish to highlight the solid aspirations of farmers on mechanization. This is supported at all levels, self, family, and community. Farm mechanization has been a perennial vision in the Philippines that should have been realized yesterday. It is never too early for this to come to fruition. We should also pay attention to the general aspirations of farmers, which go beyond being farmers, and more as productive members of their respective communities. This means that addressing these aspirations goes beyond the domains of agriculture. This requires operating beyond organizational silos, and more on inter-organizational collaborations in addressing farmers’ concerns.

Author Contributions

All authors are responsible for data collection, literature review, analysis, verification, and drafting of the manuscripts. J.M. and CD are responsible for writing the final paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Philippine Rice Research Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution.

Informed Consent Statement

The participants were asked to sign an informed consent sheet, which details their rights as research participants as well as information relating to anonymity and how the information from this research will be used. Pseudonyms are used throughout this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request from the corresponding author, the data presented in the present paper are available.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the eight provinces’ farmers and key informants with whom they have had the pleasure to work during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. Aspiration. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/aspirations (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Anglin, A.H.; Kincaid, P.A.; Short, J.C.; Allen, D.G. Role Theory Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future Applications of Role Theories in Management Research. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 1469–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, M.; Jerneck, A.; Dejen, A. Food insecurity experience during climate shock periods and farmers’ aspiration in Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. 2023, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, G. , Mzoughi, N., Napoléone, C., & Pellegrin, C. Does activating legacy concerns make farmers more likely to support conservation programmes? J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2021, 10(2), 115-129. [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, G.; Liu, Y.; Shalley, C.E. Working with creative leaders: Exploring the relationship between supervisors' and subordinates' creativity. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, D.A.; Gerber, N. Aspirations and food security in rural Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojo, D.; Fischer, C.; Degefa, T. COLLECTIVE ACTION AND ASPIRATIONS: THE IMPACT OF COOPERATIVES ON ETHIOPIAN COFFEE FARMERS’ ASPIRATIONS. Ann. Public Cooperative Econ. 2015, 87, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R. , Nedumaran, S. Understanding the Aspirations of Farming Communities in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review of the Literature. EJDR 2021. [CrossRef]

- Palis, F. Aging Filipino Rice Farmers and Their Aspirations for Their Children. Philipp. J. Sci. 2020, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippine Statistics Association. 2021 Full Year Official Poverty Statistics Tables. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2021%20Full%20Year%20Official%20Poverty%20Statistics%20Tables_f.xlsx (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Zantsi, S. Zantsi, S., Mack, G., and Vink, N. Towards a Viable Farm Size – Determining a Viable Household Income for Emerging Farmers in South Africa's Land Redistribution Programme: An Income Aspiration Approach. Agrekon 2021, 60, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).