1. Introduction

In recent years, solventogenic Clostridia have garnered significant attention in the post-genomic era, primarily owing to the comprehensive sequencing and annotation of their genomes [

1,

2]. This wealth of genomic information has provided valuable insights into the metabolism of these industrially important strains, thereby catalyzing new approaches to genetic analysis, functional genomics, and metabolic engineering for the development of industrial strains geared towards biofuel and bulk chemical production.

To facilitate these endeavors, various reverse genetic tools have been devised for solventogenic Clostridia. These tools include markerless gene inactivation systems, employing methods such as homologous recombination with non-replicative [

3,

4,

5] and replicative plasmids [

6,

7,

8,

9], as well as the insertion of group II introns [

10,

11]. For all homologous recombination-based methods involving two crossing-over, the use of a counterselection technique is imperative. This may involve employing CRISPR-Cas9 [

12,

13] or a counterselectable marker, which have been constructed using the codon-optimized

mazF toxin gene from

Escherichia coli (under the control of a lactose-inducible promoter) [

7], the

pyrE [

8] gene (encoding an orotate phosphoribosyltransferase, leading to 5-fluoroorotate (5-FOA) toxicity), the

upp gene (encoding an uracil phosphoribosyltransferase, leading to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) toxicity) [

5,

9], or the

codA gene [

4] (encoding a cytosine deaminase that converts 5-Fluorocytosine to 5-FU, which is further transformed into a toxic compound by the product of the

upp gene).

It is worth noting that while strategies relying on 5FC/5FU selection are highly effective, they should be employed cautiously. 5FU is a well-known anticancer drug recognized for its mutagenic properties in human cancers [

14]. These mutagenic attributes have been demonstrated in various organisms, including

Caenorhabditis elegans,

E. coli, or

Mycobacterium tuberculosis [

15,

16,

17].

In our study, we will demonstrate that a mutation impairs the 5FU counterselection method. Upon identification of this issue, we endeavored to enhance the 5FU counterselection method for genome editing in

C. acetobutylicum. This improvement involved the development of a corrective and preventive suicide plasmid, inspired by Foulquier et al. [

5], featuring the introduction of a synthetic codon-optimized

pyrR gene, referred to as

pyrR*. Additionally, we created a corrective replicative plasmid, building upon the work of Raynaud et al. [

18], which incorporated the native

pyrR gene. These two plasmids effectively circumvented the unanticipated 5FU resistance observed in

C. acetobutylicum, substantially improving our team's previously described method by also reducing the concentration of 5FU required by a factor of 200 (from 1 mM to 5 µM) using a synthetic define medium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are referenced in

Table 1. The oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification were synthesized and provided by Eurogentec are listed in

Table 2.

2.2. Growth Conditions

E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium.

C. acetobutylicum strains were maintained as spores in synthetic medium (SM) at - 20°C as previously described or, for non-sporulating strains, directly in degassed and sterile serum bottles at - 80°C [

21,

22,

23]. Spores were activated by heat shock at 80°C for 15 min. Strains were grown under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C in Clostridial Growth Medium (CGM) supplemented each time with 30 gL

-1 of glucose [

24] or in CGM supplemented with 20 gL

-1 MES hydrate (Sigma Aldrich) , synthetic medium (SM) or in SM supplemented with 20 gL

-1 MES hydrate or in Reinforced Clostridial Medium (RCM) (Millipore). The pH of CGM was adjusted at 6.0 or 5.2 with hydrochloric acid. The pH of RCM was adjusted at 5.8 with hydrochloric acid. The SM used for

C. acetobutylicum growth contained per liter of deionized water: Glucose, 30 g; KH

2PO

4, 0.50 g; K

2HPO

4, 0.50 g; MgSO

4.7H

2O, 0.22 g; acetic acid, 2.3 mL; FeSO

4.7H

2O 10 mg; para amino benzoic acid, 8 mg; biotin, 0.08 mg, nickel (II) chloride, 3 mg; zinc chloride, 60 mg; nitriloacetic acid, 0.2 g. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 6.0 with ammonia. For solid media preparation, 1.5 % agar was added to liquid media. The media were supplemented as needed with the appropriate antibiotic at the following concentrations: for

C. acetobutylicum, erythromycin (Ery) at 40 µg/mL, clarithromycin (Clari) at 40 µg/mL, and thiamphenicol (Tm) at 10 µg/mL; for

E. coli, carbenicillin (Cb) at 100 µg/mL and chloramphenicol (Cm) at 30 µg/mL. Stocks of 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) and uracil (Sigma Aldrich) were prepared at 0.1 M in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at - 20°C.

2.3. DNA manipulation

Genomic DNA was extracted from C. acetobutylicum strains using GenEluteTM Bacterial Genomic DNA Kits (Sigma-Aldrich). Plasmids DNA were extracted from E. coli using NucleoSpin® Plasmid or NucleoBond® Xtra Midi kits (Macherey-Nagel). Phusion DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs (NEB)) was used to generate PCR products according to the supplier's standard protocols. OneTaq® 2X Master Mix with Standard Buffer (NEB) was used to screen colonies by PCR according to the supplier's standard protocols. Restriction enzymes, antartic phosphatase, T4 DNA ligase (NEB) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gel using ZymocleanTM Large Fragment DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research). DNA PCR fragments were purified using NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up (Macherey-Nagel). Plasmid DNA and DNA PCR fragments were sequenced using sanger method (Eurofins Genomics).

2.4. Design of pyrR*

The nucleotide sequence of

pyrR gene (

CA_C2113) was codon optimized to create a synthetic

pyrR gene, named

pyrR*, with low identity to the wildtype

pyrR, in which some codons have been replaced by other codons with closed frequency in

C. acetobutylicum using

https://gcua.schoedl.de/. The synthetic gene was then synthesized (Geneart, Thermofisher Scientific).

Table 3.

Nucleotide sequence of wild-type pyrR gene and pyrR*gene.

Table 3.

Nucleotide sequence of wild-type pyrR gene and pyrR*gene.

| Gene name |

Nucleotide sequence |

wild-type pyrR

synthetic pyrR (pyrR*) |

ATGAATTTAAAAGCAAAGATTTTAGATGATAAGGCTATGCAAAGGACTTTGACCAGAATAGCACATGAAATTATAGAAAAGAATAAAGGTATAGATGATATAGTACTAGTAGGAATAAAGAGAAGAGGAGTTCCAATAGCCGATAGAATAGCGGATATAATTGAAGAAATAGAAGGAAGTAAGGTTAAGCTAGGAAAAGTAGATATAACCTTATATAGAGACGATTTGTCTACGGTAAGTTCTCAACCAATAGTAAAAGATGAGGAAGTATATGAAGATGTAAAGGATAAGGTAGTAATACTTGTTGATGACGTTTTATATACAGGAAGAACATGCAGAGCAGCCATAGAAGCTATTATGCATAGAGGAAGACCAAAGATGATACAGCTTGCAGTTTTGATAGATAGGGGACATAGAGAACTTCCTATAAGGGCAGATTATGTTGGAAAAAATGTACCTACATCAAAAAGTGAATTGATATCGGTAAATGTTAAAGGAATAGATGAAGAGGATTCAGTAAACATTTATGAGTTGTAG

ATGAATCTTAAAGCTAAGATTCTTGATGATAAGGCAATGCAAAGGACACTAACCAGAATAGCTCATGAAATAATAGAAAAGAATAAAGGAATAGATGATATAGTTTTGGTTGGAATAAAGAGAAGAGGAGTACCTATAGCGGATAGAATAGCCGATATAATAGAAGAAATAGAAGGATCAAAGGTAAAGTTGGGAAAAGTTGATATAACCCTTTATAGAGACGATCTATCAACCGTTTCAAGTCAACCTATAGTTAAAGATGAGGAAGTTTATGAAGATGTTAAGGATAAGGTTGTTATATTAGTTGATGACGTACTTTATACTGGAAGAACTTGCAGAGCTGCGATAGAAGCAATAATGCATAGAGGAAGACCTAAGATGATACAGTTAGCTGTACTAATAGATAGGGGACATAGAGAACTACCAATAAGGGCTGATTATGTAGGAAAAAATGTTCCAACTAGTAAATCAGAATTGATATCCGTAAATGTAAAAGGAATAGATGAAGAGGATAGTGTTAACATATATGAGCTATAG |

2.5. Construction of pCat-upp-pyrRmut

This plasmid was constructed, based on the pCat-

upp described by Foulquier

et al. [

5] by introducing the

pyrRmut gene containing the mutation

g.344C>T encoding the PyrR A115V protein found in our mutant strain. The mutant

pyrR gene was PCR amplified from total DNA from

CAB1060 as template using the PSC 75 and PSC 76 primers containing

BamHI restriction sites. The PCR fragment and the pCat-

upp were digested by

BamHI. The plasmid was dephosphorylated with antarctic phosphatase and the PCR fragment and the plasmid were purified. The PCR fragment was cloned by ligation into the plasmid to obtain pCat-

upp-pyrRmut.

2.6. Construction of pCat-upp-pyrR*

This plasmid was constructed from the pCat-

upp described by Foulquier

et al. [

5] by introducing the synthetic

pyrR* gene under the control of the thiolase promoter. The entire pCat-

upp plasmid was amplified with PSC 51 and PSC 52 for linearization. The

pyrR* gene was PCR amplified primers using synthetic

pyrR gene (from Geneart) as template. A first PCR was performed with PSC 61 and PSC 62 primers to amplify the

pyrR gene with its native RBS and downstream homology arms. The first PCR fragment was then purified. A second PCR was performed on the first PCR product with PSC 72 and PSC 62 to introduce upstream homology arm. The final PCR fragment of

pyrR* was cloned into linearized pCat-

upp plasmid by recombination using the GeneArt

TM Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (Thermofisher Scientific).

2.7. Construction of pCat-upp-pyrR*- Δldh

This plasmid was constructed based on the

pCat-upp-pyrR* (this study) and the pCat-

upp-Δ

ldh described by Soucaille

et al. in the patent WO 2016/042160 A1 [

20]. The

pCat-upp-pyrR* plasmid was linearized by digestion with

BamHI restriction enzyme and dephosphorylated with antartic phosphatase. Then the pCat-

upp-Δ

ldh plasmid was digested with

BamHI and the fragment containing the

ldh homology arms was purified from agarose gel. The two fragments were then ligated using T4 DNA Ligase.

2.8. Construction of pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh::sadh-hydG

This plasmid was constructed based on the pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh plasmid (this study) by introducing an operon composed of sadh and hydG genes (GenBank: AF157307.2), with their own RBS, under the control of the ldh promoter. The pCat-upp-Δldh was digested by StuI, dephosphorylated and purified. sadh and hydG were amplified from a synthesized sadh_hydG genes (Genart, Thermofisher) as template. A first PCR was performed with PSC 104 and PSC 105 to amplify sadh_hydG genes and introduce the ldh promoter region upstream of sadh and the ldh terminator downstream of hydG. After purification, the first PCR product was then amplified with PSC 106 and PSC 107 to introduce upstream and downstream homology arms to recombine with the pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh plasmid. The final PCR fragment was cloned into the pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh by recombination using the GeneArtTM Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (Thermofisher Scientific).

2.9. Construction of pSOS95-pyrR

This plasmid was constructed based on the pSOS95 plasmid described by Raynaud

et al. [

18] by introducing the native

pyrR gene under the control of the thiolase promoter. The pSOS95 plasmid was digested with

BamHI and

SfoI and purified from agarose gel. The

pyrR gene was amplified using total DNA from the strain

Δcac1502 as template. The PSC 58 and PSC 46 used for this amplification introduced the

BamHI restriction site upstream of the

pyrR gene RBS and the

SfoI restriction site downstream of the

pyrR gene. The PCR fragment was digested with

BamHI and

SfoI, purified. And cloned in the pSOS95 plasmid by ligation using T4 DNA Ligase.

2.10. Transformation protocol

Transformation of C. acetobutylicum was performed by electroporation according to the following protocol. From a culture of C. acetobutylicum in CGM at A620 between 1 and 2, a new serum bottle with 50 ml of CGM was inoculated at A620 of 0.1. When the culture reached A620 between 0.6 and 0.8, the culture has been placed on ice for 30 minutes and transferred under an anaerobic chamber (Jacomex) where all the following manipulations were performed. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 7000g for 15 minutes and washed in 10 mL of ice-cold electroporation buffer (EB) composed of 270 mM sucrose, 10 mM MES hydrate at pH 6.0. Then the pellet was resuspended in 500 µL of EB and cells were transferred into a sterile electrotransformation vessel (0.40 cm electrode gap x 1.00 cm) with 5-100 µg plasmid DNA. A 1.8 kV discharge was applied to the suspension from a 25 µF capacitor and a 400 Ω resistance in parallel using the Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). Cells were transferred directly to 10 mL of warm CGM and incubated for 6 hours at 37°C before plating on RCM supplemented with the required antibiotics.

2.11. Microbiological enumeration on solid media

C. acetobutylicum was cultivated in CGM until reaching an A620 of 0.55. Subsequently, the culture was transferred to an anaerobic chamber, and 100 µL of various dilutions (10-1 to 10-6) of the culture were plated onto CGM MES or SM MES agar supplemented with the necessary antibiotics, ranging from 0 µM to 200 µM for 5FU and from 0 µM to 50 µM for uracil. Following incubation at 37 °C for a period of 1 to 4 days, the resulting colonies were counted.

2.12. 5FU selection protocol

C. acetobutylicum was cultivated in CGM until reaching an A620 of 0.55. The spreading protocol was the same as described in subsection 2.11. After isolation, 50 colonies were picked and plated on a fresh plate with the same concentration of 5FU. The plates were incubated at 37 °C from 1 to 2 days. The colonies were then picked and patched onto plates with and without thiamphenicol to determine the percentage of double crossing-over. Colonies showing a double crossover phenotype were screened by PCR to verify that genome editing occurred.

2.13. Locus verification in C.acetobutylicum after metabolic engineering

After the genome edition of

C. acetobuylicum, the different loci were checked by PCR amplification. In order to check for the insertion of point mutations, the genome was amplified by PCR and the PCR fragment obtained was sent for sequencing.

| Primers name |

Function |

| PSC 39 – PSC 40 |

pyrR gene sequencing |

| PSB 384 – PSB 385 |

ldh locus verification |

2.14. Analytical procedures

Culture growth was monitored by measuring optical density over time using a spectrophotometer at A620. Glucose, acetate, butyrate, acetone, isopropanol, ethanol and butanol concentrations were measured using High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis (Agilent 1200 series, Massy, France). The separations were performed on a Biorad Aminex HPX-87H column (300 mm x 7.8 mm), and detection was achieved using either a refractive index measurement or a UV absorbance measurement (210 nm). The operating conditions were as follows: temperature, 14 °C; mobile phase, H2SO4 (0.5 mM); and flow rate, 0.5 ml/min.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we have shown that overexposure of

C. acetobutyicum to 5FU can make it resistant to this drug. Spontaneous mutations are induced in the bacterial chromosome, notably in the

pyrR gene. As described in other publications, the

pyrR gene encodes for PyrR, the repressor of the pyrimidine operon [

16,

17,

25]. The presence of a mutation in this protein can lead to the cessation of its function, resulting in an overproduction of UMP. This overproduction of UMP can protect against the harmful effects of 5FUMP, a molecule that is toxic to bacteria. We observed the appearance of a mutation in the PyrR protein of

C. acetobutylicum that completely avoids selection of the double crossing-over step when using the pCat

upp/5FU system. The principle of the

upp/5FU system was based on the use of a strain in which the

upp gene has been deleted and the use of 5FU as a counter selection agent. The

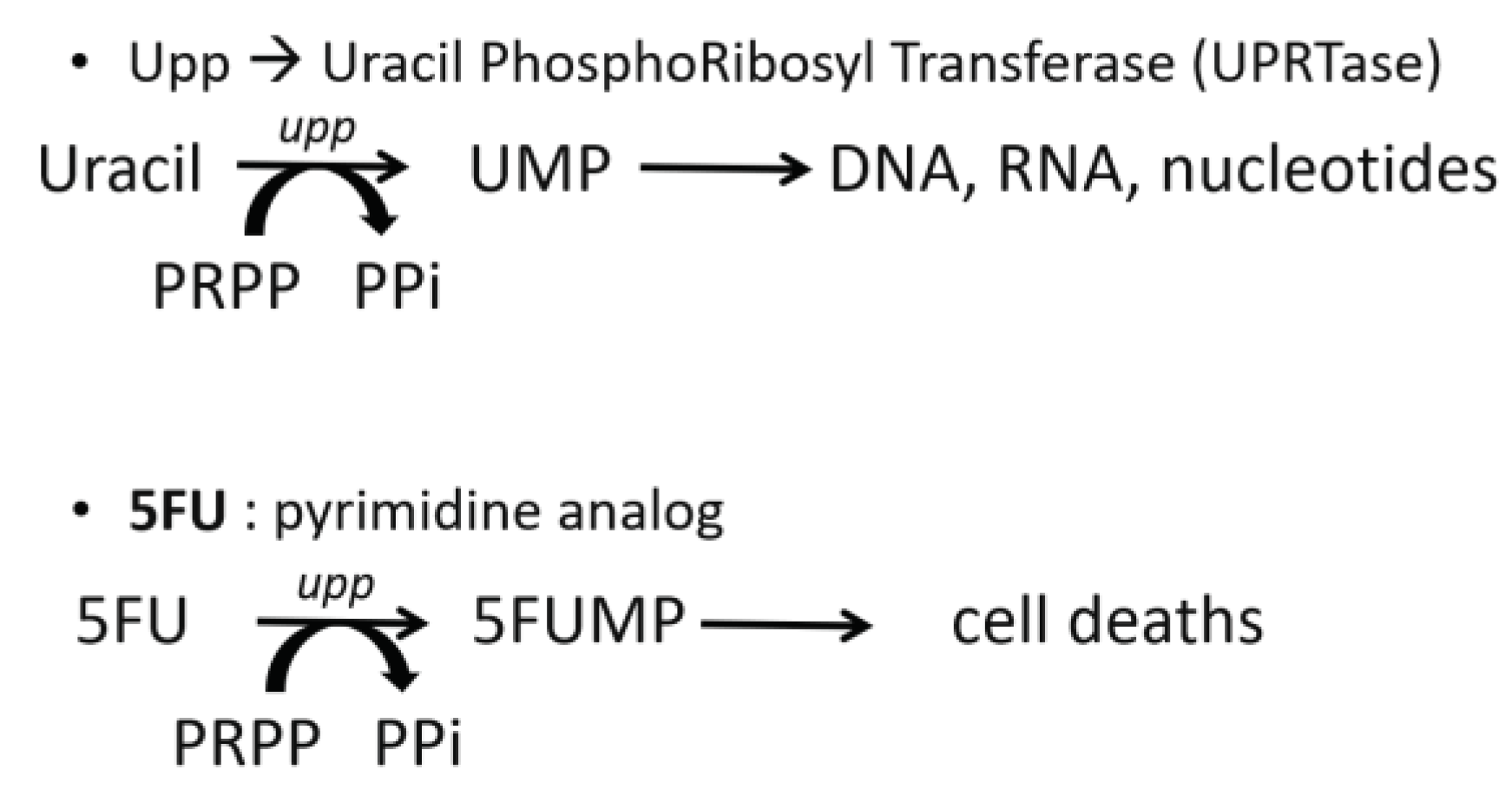

upp gene encoding for an uracil phosphoribosyl transferase (UPRTase) that could convert uracil to UMP and 5FU to 5FUMP. 5FUMP is a molecule that prevents cells from producing intermediates needed for DNA synthesis, thereby causing cell death (

Figure 5) [

17].

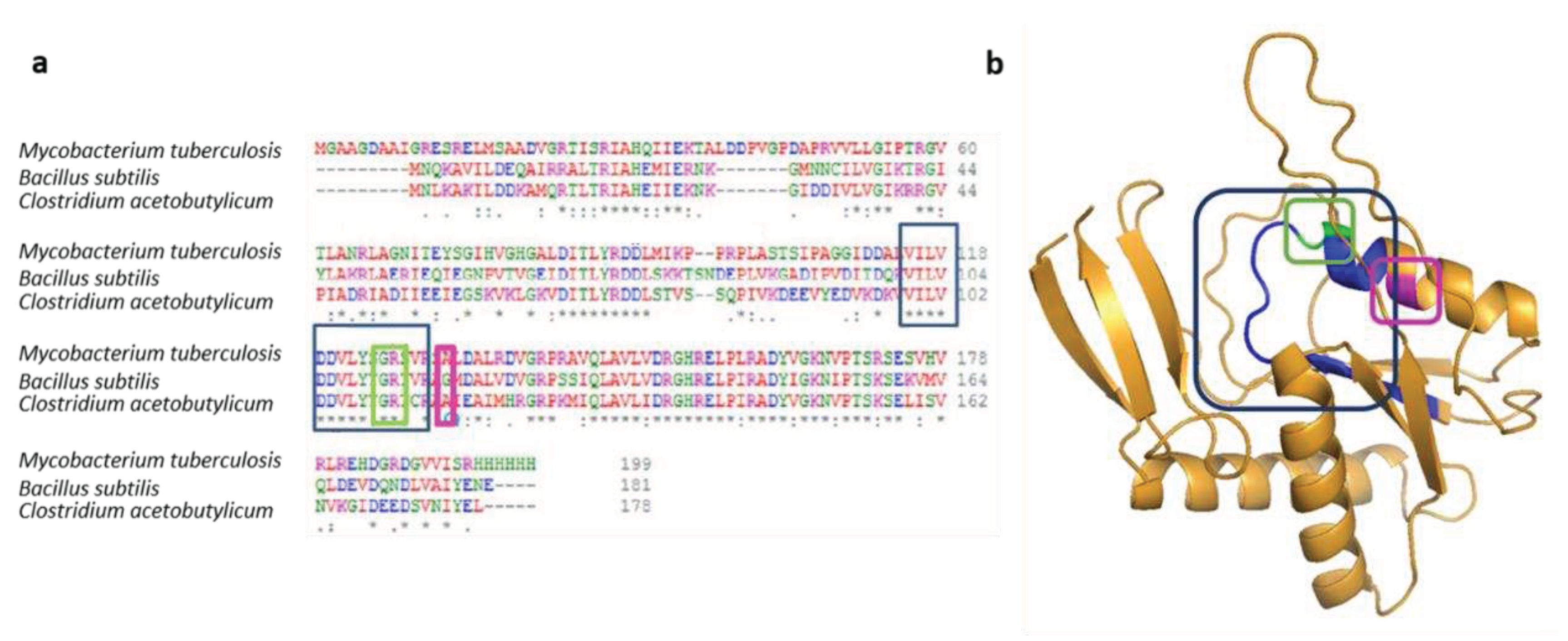

When the A115V PyrR mutation was discovered in

C. acetobutylicum, we compared it with other mutations in homologous proteins already described in the literature. A conserved protein sequence required in PRPP binding can be found in many species. Ghode and Singh described the G125V and R126C mutations

in M. tuberculosis as being in this conserved zone [

16,

17]. According to Ghode, a mutation in this region could block the production of 5FUMP. As A115V PyrR mutation is situated close to this site, it could be one of the reasons why our strain is resistant to 5FU (

Figure 6). In addition,

pyrR encodes the regulatory protein of the pyrimidine operon. According to Ghode and Fields [

16,

29], mutations in PyrR of

M. tuberculosis or

M. smegmatis, or when PyrR is completely deleted in

B. subtilis the protein no longer performs its regulatory function and the pyrimidine operon is overexpressed [

25]. This results in overproduction of UMP, which protects the bacteria from the toxic effects of 5FUMP.

To overcome this problem, we had to revise the protocol previously described by our team. First, we realized that the composition of the medium plays an important role in the resistance of the strain to 5FU. It is preferable to use a synthetic medium that is not supplemented with uracil. In fact, the yeast extract present in CGM brings uracil into the medium and thus protects against the toxic effect of 5FUMP. This hypothesis was tested by adding low concentrations of uracil to the synthetic medium. Bacterial growth was no longer affected by the presence of 5FU in the medium. After optimizing the medium for 5FU selection, we constructed two plasmids to restore the sensitivity of the strain to 5FU. The first plasmid is a replicative plasmid overexpressing a native version of

pyrR. It is used to overcome the problems of 5FU selection when a strain mutated in the

pyrR gene has already integrated a pCat-

upp. The second plasmid is a pCat-

upp containing a codon optimised version of the

pyrR gene, called

pyrR*. The 5FU selection problem for genome editing is directly bypassed by this method. With both of these strategies, the concentration of 5FU could be reduced from 1 mM to 5 µM, thus minimizing the risk of spontaneous mutation. Both the use of

pyrR* and the use of the SM medium will be beneficial for all the counterselection methods involving

upp and 5FU, as well as those utilizing

codA and 5FC [

4] .

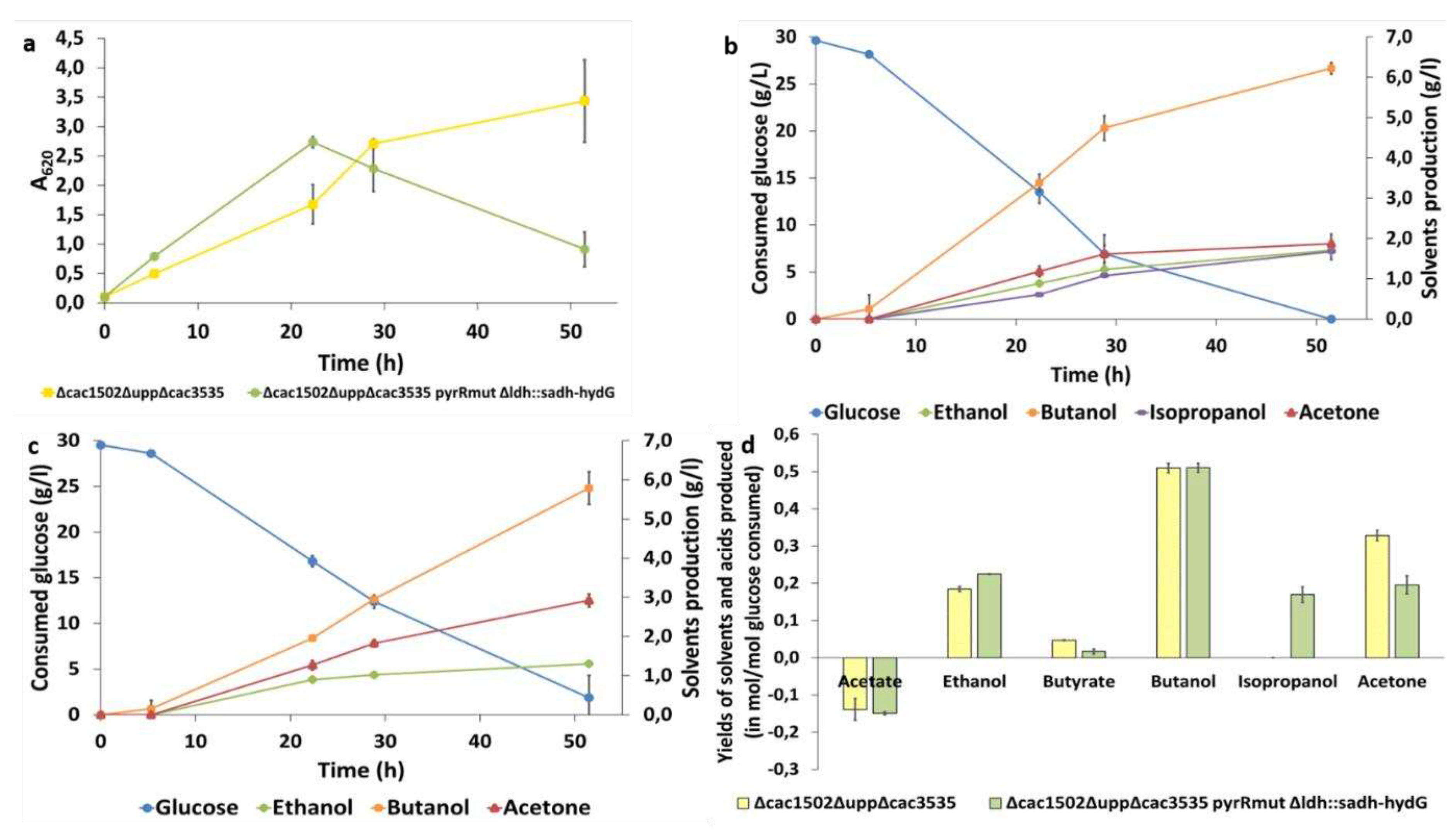

Once the new protocol was established, we demonstrated that it was possible to both delete and insert genes of interest in

C. acetobutylicum ∆cac1502∆upp∆cac3535 pyrRmut strain in a single step using the pCat-

upp-pyrR*/5FU system. An isopropanol production pathway from

C. beijerinckii was inserted at the

ldh of

C. acetobutylicum ∆cac1502∆upp∆cac3535 pyrRmut∆ldh::sadh-hydG strain using this technique. We decided to insert the

sadh and

hydG genes from

C. beijerinckii NRRL 593 following a publication by Dusséaux et al. [

27]. SADH is an NADPH-dependent primary-secondary alcohol dehydrogenase that catalyzes acetone reduction and HydG is a putative electron transfer protein [

28,

32].

hydG was introduced into the

C. acetobutylicum ∆cac1502∆upp∆cac3535 pyrRmut strain genome at the same time as

sadh, since these two genes are located in the same operon in

C. beijerinkcii NRRL 593. It was assumed that the HydG activity would have a positive effect on the SADH activity, allowing the strain to obtain a better isopropanol production [

28]. The final production of our

C. acetobutylium ∆cac1502∆upp∆cac3535 pyrRmut ∆ldh::sadh-hydG strain is lower than the one obtained by Dusséaux (up to 4.7 g.L

-1 of isopropanol produced in a culture of 30 h) with a lower molar ratio of isopropanol/acetone [

27]. This can be explained by the fact that in this strain both gene were overexpressed in a multi copy replicative plasmid and under the control of the

ptb promoter, which is a stronger promoter than the

ldh promoter [

33]. The strain had also been grown in pH-regulated batch cultures, whereas we grew our strain in serum bottles without pH regulation. Better results would probably be obtained if the “isopropanol operon” was introduced at the

ptb buk locus and if the pH of the culture was controlled.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F. and P.S.; methodology, E.B.; validation, C.F. and P.S.; resources, P.S.; data curation, C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B and C.F.; writing—review and editing, C.F. and P.S.; supervision, P.S and C.F.; project administration, P.S.; funding acquisition, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

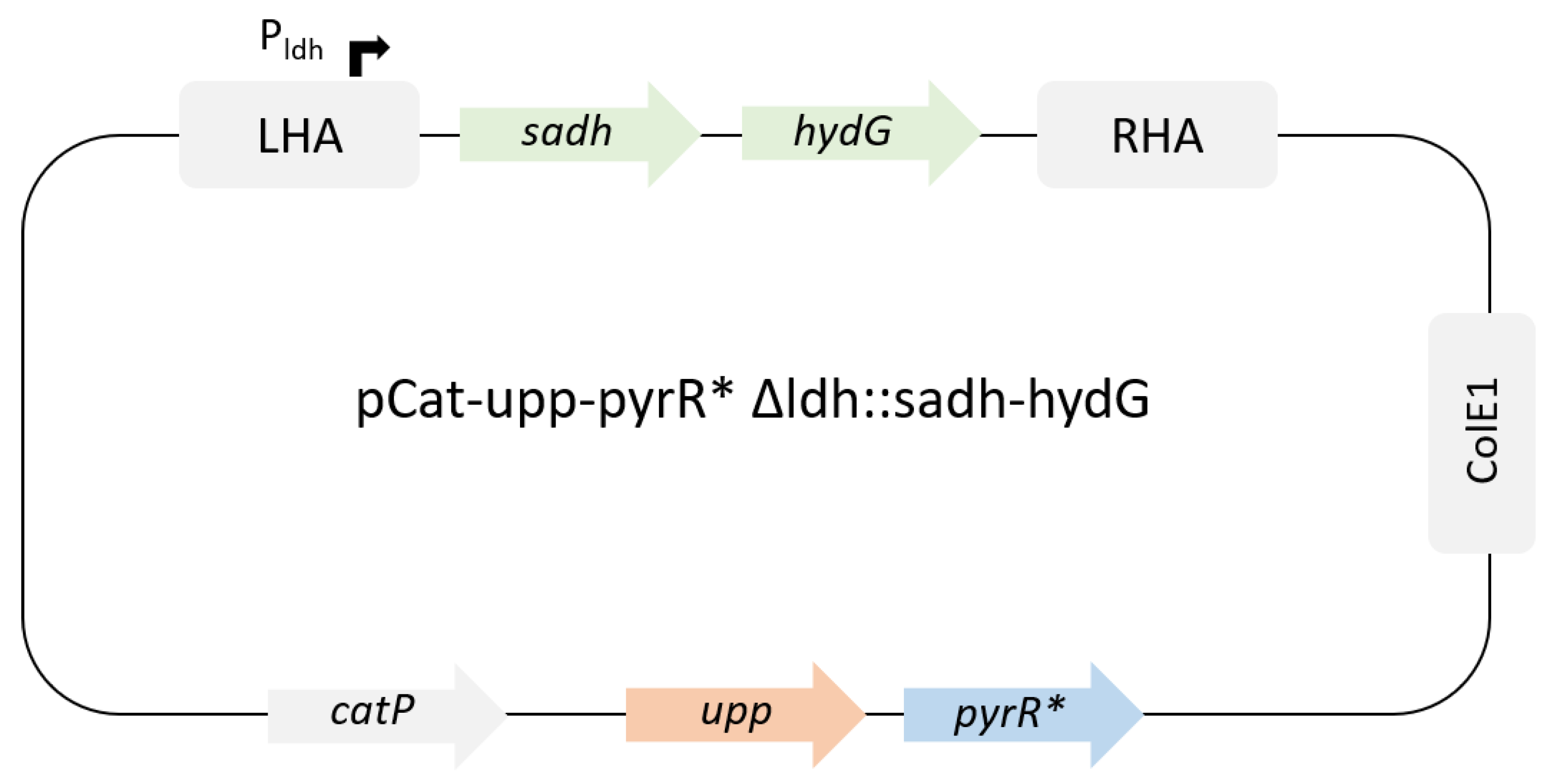

Figure 1.

Suicide plasmid for ldh replacement by sadh and hydG from C.beijerinckii

Figure 1.

Suicide plasmid for ldh replacement by sadh and hydG from C.beijerinckii

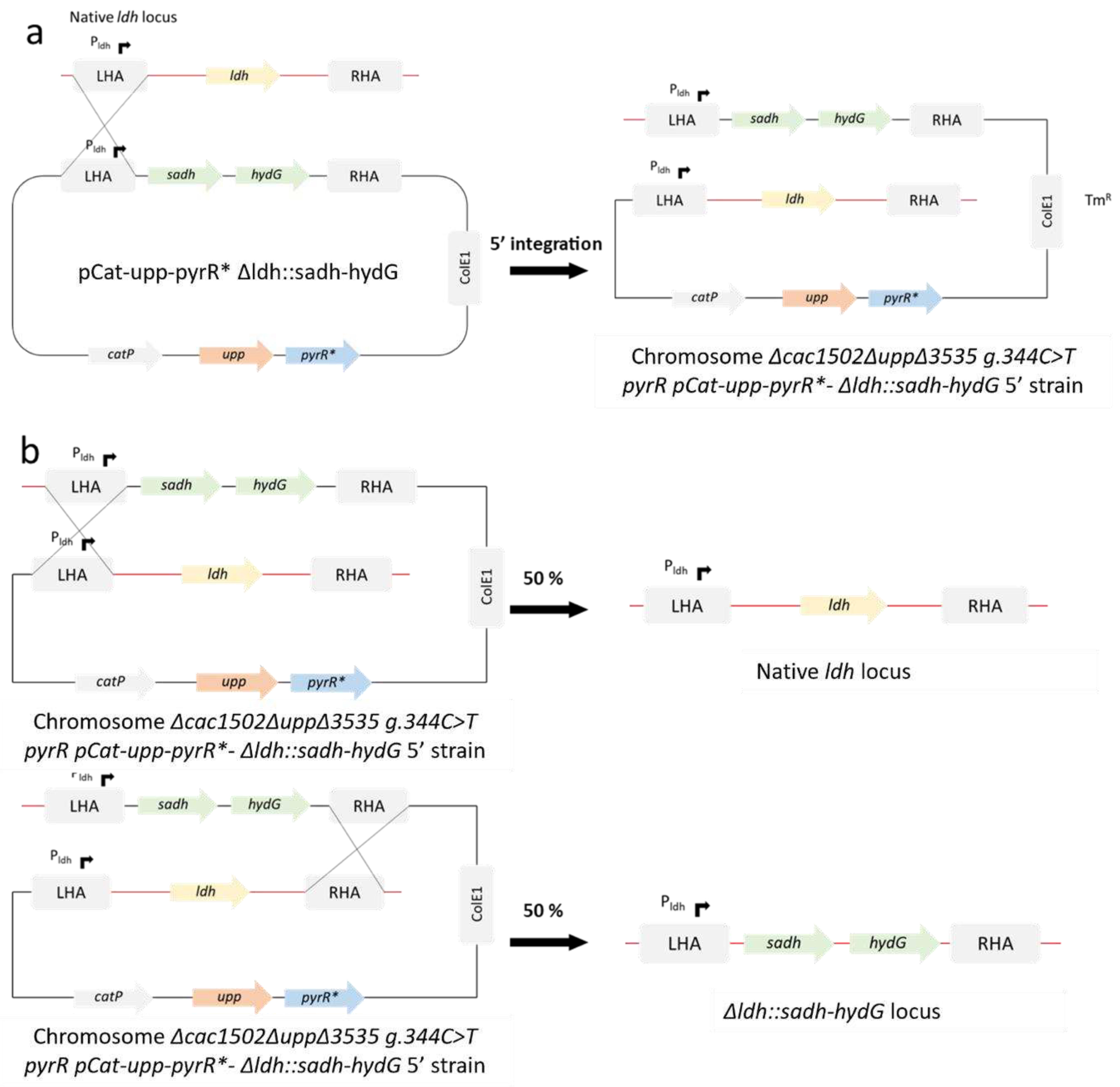

Figure 2.

Diagram representing the replacement of ldh by sadh and hydG from C. beijerinckii by allelic ex-change in Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535 pyrRmut. LHA: left homology arm; RHA: right homology arm. a 5’ integration of the suicide plasmid. The integrants are selected on thiamphenicol. b Double crossing-over induced by 5FU that cause the excision of the suicide plasmid.

Figure 2.

Diagram representing the replacement of ldh by sadh and hydG from C. beijerinckii by allelic ex-change in Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535 pyrRmut. LHA: left homology arm; RHA: right homology arm. a 5’ integration of the suicide plasmid. The integrants are selected on thiamphenicol. b Double crossing-over induced by 5FU that cause the excision of the suicide plasmid.

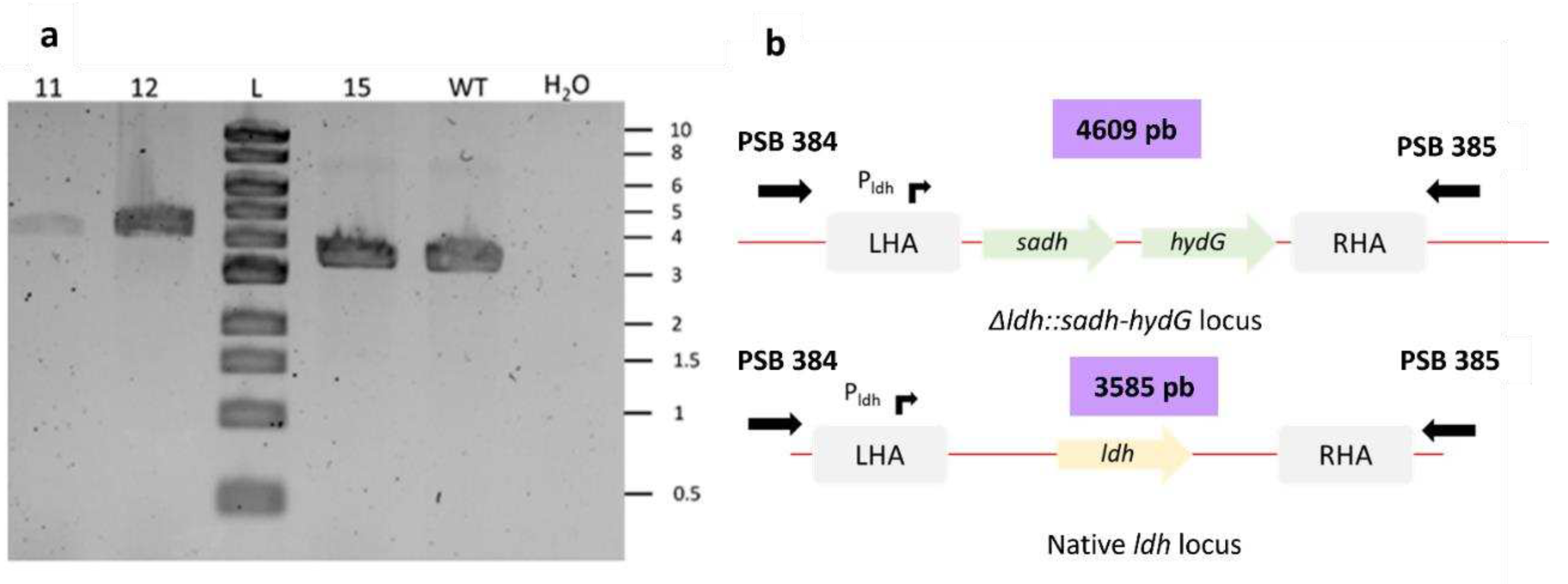

Figure 3.

Figure 3. a Screening of Δldh::sadh hydG mutant. The colonies were screened using PSB 384 and PSB 385 primers. Ladder: 1kb DNA ladder provided by New England Biolabs. b Schematic representation of Δldh::sadh hydG locus and native ldh locus.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. a Screening of Δldh::sadh hydG mutant. The colonies were screened using PSB 384 and PSB 385 primers. Ladder: 1kb DNA ladder provided by New England Biolabs. b Schematic representation of Δldh::sadh hydG locus and native ldh locus.

Figure 5.

Metabolism of 5FU. PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphatase; PPi, pyrophosphatse; UMP, uridine monophosphate; 5FU, 5-fluorouracile; 5FUMP, 5-fluorouridine monophosphate.

Figure 5.

Metabolism of 5FU. PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphatase; PPi, pyrophosphatse; UMP, uridine monophosphate; 5FU, 5-fluorouracile; 5FUMP, 5-fluorouridine monophosphate.

Figure 6.

a Multiple sequences alignment of PyrR.

b Cartoon diagram of PyrR protein of

C.acetobutylicum predicted by Alpha-fold [

30,

31]. The blue boxes show the amino acids implied in PRPP binding. The green boxes highlight G125 and R126 sites described by Ghod and Singh [

16,

17]. The pink boxes represent the A115 position, where

C.acetobutylicum was mutated.

Figure 6.

a Multiple sequences alignment of PyrR.

b Cartoon diagram of PyrR protein of

C.acetobutylicum predicted by Alpha-fold [

30,

31]. The blue boxes show the amino acids implied in PRPP binding. The green boxes highlight G125 and R126 sites described by Ghod and Singh [

16,

17]. The pink boxes represent the A115 position, where

C.acetobutylicum was mutated.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid |

Relevant characteristics |

Source or reference |

Bacterial strains

E. coli

TOP10 |

|

Invitrogen |

C. acetobutylicum

CAB1060

Δcac1502

Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535

Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535 pyrRmut

Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535 pyrRmut Δldh::sadh hydG

|

ΔCAC1502ΔuppΔptbΔbukΔctfABΔldhAΔrexA ΔthlA::atoB Δhbd::hbd1

ΔCA_C1502

ΔCA_C1502 ΔCA_C2879 ΔCA_3535

ΔCA_C1502 ΔCA_C2879 ΔCA_3535 CA_C2113 g.344C>T

ΔCA_C1502 ΔCA_C2879 ΔCA_3535 CA_C2113 g.344C>T ΔCA_C0227:: CIBE_3470 HydG (Accession: P25981.3)

|

[19]

[9]

[9]

This study

This study

|

Plasmid

pCat-upp

pCat-upp- pyrRmut

pCat-upp-Δldh

pCat-upp-pyrR*

pCat-upp-pyrR*- Δldh

pCat-upp-pyrR*-∆ldh::sadh-hydG

pSOS95

pSOS95-pyrR

|

CmR, upp, colE1 origin

CmR, upp, pyrR edition cassette for C. acetobutylicum

CmR, upp, ldh deletion cassette for C. acetobutylicum

CmR upp pyrR*

CmR, upp pyrR*, ldh deletion cassette for C. acetobutylicum

CmR, upp pyrR*, ldh substitution cassette for sadh hydG for C. acetobutylicum

ApR,MLSR , acetone operon, repL gene, colE1 origin

ApR, MLSR, pyrR, repL gene, colE1 origin

|

[5]

This study

[20]

This study

This study

This study

[18]

This study |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification.

| Primer name |

5’-3’ Oligonucleotide Sequence |

PSC 39

PSC 40

PSC 46

PSC 51

PSC 52

PSC 58

PSC 61

PSC 62

PSC 72

PSC 75

PSC 76

PSC 104

PSC 105

PSC 106

PSC 107

PSB 384

PSB 385 |

GCATGCTCTTGTAGGTGATCCTT

TGTTTACTGAATCCTCTTCATCTATTCC

AAAAAAGGCGCCCTACAACTCATAAATGTTTACTGAATCCTC

CAGAGTATTTAAGCAAAAACATCGTAGAAAT

TTATTTTGTACCGAATAATCTATCTCCAGC

AAAAAAGGATCCTTATACTGGAGGTGAGTGTATGAATTTAAAAG

CCATGGTTATACTGGAGGTGAGTGTATGAATCTTAAAGCTAAGATTCTTGATGATAAGGC

AAACACCGTATTTCTACGATGTTTTTGCTTAAATACTCTGCCATGGCTATAGCTCATATATGTTAACACTATCCTCTTC

TCTTGGAGATGCTGGAGATAGATTATTCGGTACAAAATAACCATGGTTATACTGGAGGTGAGTG

TTAATAGGATCCGAACCCATCAAATAAGAGTGCATATGG

TATTAAGGATCCAGTCCTGCCCAACC

AAATATAAATGAGCACGTTAATCATTTAACATAGATAATTAAATAGTAAAAGGAGGAACATATTTTATGAAAGGTTTTGC

GGCAAAAGTTTTATAAACATGGGTACTGGTTATATTATATTATTTATGACTTTATTATTTATCACCTCTGCAACCACAGC

TAGAGAAATTTTTAAAGATTTCTAAAGGCCTTTAACTTCATGTGAAAAGTTTGTTAAAATATAAATGAGCACGTTAATCATTTAA

TCCACCCTTGGAGTTTAGGTCTTTTACCAGGCCTGAATACCCATGTTTATAGGGCAAAAGTTTTATAAACATGGGTACT

GGGAAAGGTTTTAAGAGCGGCG

CAACAATTGTCTCCGGTTTCAAGGG |

Table 4.

Bactericidal effect of 5FU on cac1502 on CGM MES and SM MES

Table 4.

Bactericidal effect of 5FU on cac1502 on CGM MES and SM MES

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

CGM MES (UFC/mL) |

SM MES (UFC/mL) |

| 0 |

2.06 ± 0.41E7 |

1.75 + 0.25E7 |

| 5 |

1.65 ± 0.34E7 |

0 |

| 25 |

3.02 ± 0.52 E6 |

0 |

| 50 |

1.45 ± 0.28E6 |

0 |

| 100 |

0 |

0 |

| 200 |

0 |

0 |

Table 5.

Protective effect of uracil against 5FU in C. acetobutylicum ∆cac1502 strain. 0.1 ml of a 10-1 dilution of a CGM culture were spread on the different SM MES plates.

Table 5.

Protective effect of uracil against 5FU in C. acetobutylicum ∆cac1502 strain. 0.1 ml of a 10-1 dilution of a CGM culture were spread on the different SM MES plates.

| Uracil concentration (µM) |

Number of colonies (5 µM 5FU) |

| 0 |

0 |

| 5 |

Layer |

| 12.5 |

Layer |

| 25 |

Layer |

| 50 |

Layer |

Table 6.

Spontaneous mutations founded in PyrR after 5FU exposition

Table 6.

Spontaneous mutations founded in PyrR after 5FU exposition

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

Amino acid change |

Nucleotide change |

| 25 |

R124G |

g.370A>G |

| 25 |

A47D |

g.140C>A |

| 50 |

R136X |

T addition in aa 132 |

| 50 |

P45L |

g.134C>T |

| 50 |

V85X |

G deletion in aa 85 |

| 50 |

E23K |

g.67G>T |

Table 7.

Mutated pyrR strain viability on 5FU while maintaining a pCat-upp

Table 7.

Mutated pyrR strain viability on 5FU while maintaining a pCat-upp

| |

pCat-upp-Δldh

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

0 |

25 |

50 |

| SM MES + Tm (UFC/mL) |

9.52E7 |

9.14E7 |

8.46E7 |

Table 8.

Viability of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with a pCat-upp plasmid and a replicative pSOS95-pyrR plasmid

Table 8.

Viability of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with a pCat-upp plasmid and a replicative pSOS95-pyrR plasmid

| |

pCat-upp-Δldh + pSOS95-pyrR

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

0 |

5 |

10 |

25 |

| SM MES + Ery (UFC/mL) |

1.20E7 |

3.80E4 |

2.84E4 |

2.10E4 |

| SM MES + Ery + Tm (UFC/mL) |

6.28E6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 9.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with a pCat-upp plasmid and a replicative pSOS95-pyrR plasmid after 5FU selection

Table 9.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with a pCat-upp plasmid and a replicative pSOS95-pyrR plasmid after 5FU selection

| |

pCat-upp-Δldh + pSOS95-pyrR

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

5 |

10 |

25 |

| Picked colonies viability (%) |

86 |

90 |

84 |

| Picked colonies Tm sensitivity (%) |

86 |

96 |

98 |

Table 10.

Viability of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh plasmids

Table 10.

Viability of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh plasmids

| |

pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

0 |

25 |

50 |

| SM MES (UFC/mL) |

8.80E7 |

4.24E4 |

3.88E4 |

| SM MES + Tm (UFC/mL) |

7.60E7 |

0 |

0 |

Table 11.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with pCat-upp and a pCat-upp-pyrR* plasmids after 5 FU selection

Table 11.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with pCat-upp and a pCat-upp-pyrR* plasmids after 5 FU selection

| |

pCat-upp-Δldh

|

pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

5 |

10 |

25 |

50 |

5 |

10 |

25 |

50 |

| Picked colonies viability (%) |

100 |

98 |

98 |

76 |

88 |

96 |

60 |

52 |

| Picked colonies Thiamphenicol sensitivity (%) |

0 |

6 |

75 |

89 |

90 |

98 |

100 |

100 |

Table 12.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535 strain with the pCat-upp-pyrR*/ 5 FU counter selection system

Table 12.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535 strain with the pCat-upp-pyrR*/ 5 FU counter selection system

| |

pCat-upp-pyrR*-Δldh

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

5 |

10 |

| Picked colonies viability (%) |

98 |

100 |

| Picked colonies Thiamphenicol sensitivity (%) |

100 |

100 |

Table 13.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with pCat--pyrR*-Δldh::sadh-hydG after 5FU selection.

Table 13.

Viability and frequency of double crossing-over of Δcac1502ΔuppΔcac3535pyrRmut strain with pCat--pyrR*-Δldh::sadh-hydG after 5FU selection.

| |

pCat-pyrR*-Δldh::sadh-hydG

|

| 5FU concentration (µM) |

5 |

| Picked colonies viability (%) |

92 |

| Picked colonies Thiamphenicol sensitivity (%) |

100 |