Introduction

Human immunity has been challenged by SARS-CoV-2 pandemic worldwide, for last three years. Diverse bouts of viral attack took numerous lives and taken toll on the public health. Through several virologically varied waves, mutative strategies of SARS-CoV-2 transformed the pathways of encountering the host body. Correspondingly, human immune response has also been altered as the viral strains evolved. The variants of concerns (VOC) in COVID-19 pandemic acknowledged by World Health Organisation (WHO) are namely alpha, beta, gamma, delta, omicron [Tan et al., 2022]. Although the evolution of these strains includes branching of several other subtypes, yet here we concentrate chiefly on the alpha, delta and omicron variant due to their heavy impact. Throughout the period of pandemic, these three strains exhibited significantly higher degrees of pathogenicity and transmissibility in comparison to other existing strains, affecting a huge population around the globe.

The characteristic or the biomarking route of invasion remains same in all of these strains. SARS-CoV-2 being a member of the coronavirus family, spreads through air and gets a chance to intrude into human respirational tract. Later onwards it gains access to various cell types by utilizing its viral spike protein and instigating severe respiratory distress and other clinical symptoms. This particular virus had much higher impact on public health than its ancestors Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-1 (SARS-CoV-1) due to its high disease spreading as well as pathogenicity, which is strictly regulated by tissue tropism in host. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor present on enterocytic, epithelial and goblet cell surfaces has been the primary gateway for coronavirus to enter the host body in SARS-CoV-2 infection [Hou et al., 2020]. As spike protein plays a key role in host evasion, hence, mutations in those areas can effectively alter the mechanism of evasion, which thus will affect the pathogen’s location and nature of infection and the degree of escape from host’s defence [Bakhshandeh et al., 2021]. As a consequence, the spreading of disease including its clinical severity modifies its pattern in the population. In this review we aim to elucidate a comparative scenario of the infection pathways in alpha, delta and omicron strain, accompanied by the epidemiological aspects of pathogenicity and transmissibility and its corresponding human immune response.

COVID-19 Infection and Pathogenicity

As mentioned earlier, COVID-19 enters human respirational tract by air and enters the host cell using the key gateway ACE-2 receptor.

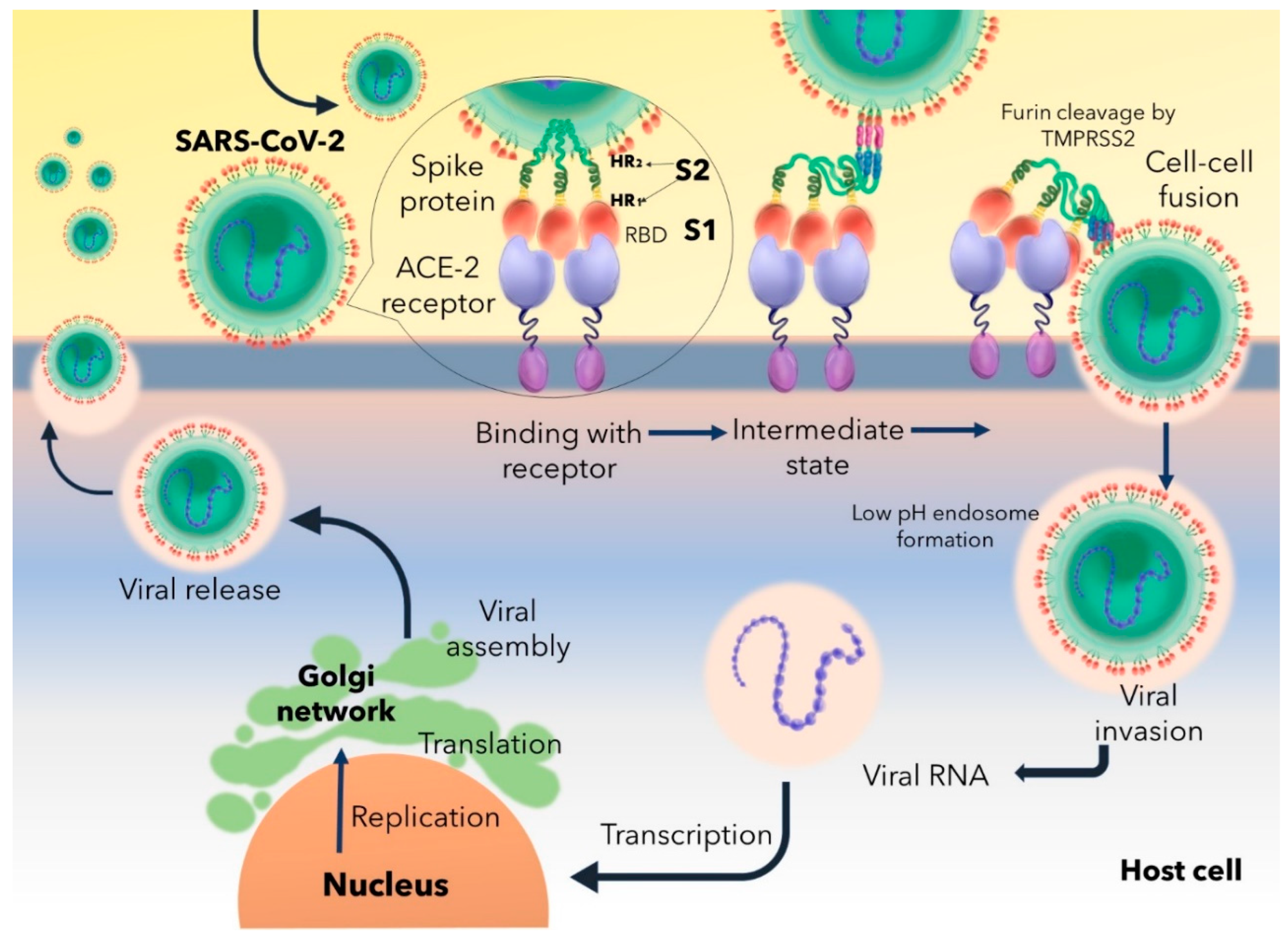

Figure 1 explains a systematic route of COVID-19 infection. The Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of S1 subunit of spike protein binds to the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor, characterizes a trimeric conformation and triggers the formation of endosome having a low pH level. ACE-2-S1 binding follows the cleavage of S1 and S2 subunits to promote viral fusion through endosome. Multiple furin cleavage sites on the spike proteins are cleaved off by host’s proteases like Transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2). Endosomal fusion is further facilitated by the extensive protein folding modifications of spike HR1 and HR2 domains of S2 by forming six helical structure which is responsible for physically reducing the host-virus distance and allows fusion of both the membranes. Endosomal fusion leads to access to the host’s cellular machineries and allows the virus to undergo proliferation and budding off of newly synthesized and packaged virions from the infected cell [

Huang et al., 2020].

Immune Response against COVID-19 Variants

Immune Response in Alpha Wave

The variant of concern “alpha” or the B.1.1.7 initially got recorded in Kent (UK) in September 2020, after the invasion of the original Wuhan strain worldwide, in March 2020 [Williams et al., 2021]. This particular strain follows the general pathway of invasion as discussed earlier [Huang et al., 2020; Acharya et al., 2020]. Infection of the B.1.1.7 strain severely undermines the translational machinery of host by a non-structural protein, NSP14 [Hsu et al., 2021]. Hijacking of this process disrupts host’s cellular translation, while the virus amplifies its own genome in the host body. Inhibition of host’s translation in turn switches off the synthesis of antiviral compounds by host. The first line of defence, innate immunity is severely interrupted by this phenomenon. Interferon-1 (INF-1) has been established as a key factor in producing effective reaction against viral attack, which induces certain subsets of Interferon-stimulated Gene (ISG) to stop viral replication [Schoggins and Rice, 2011]. Upregulation of ISG potentiates the functionality of the immune effector cells like B and T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells [Murira and Lamarre, 2016]. NSP14 targets and abolishes antiviral response forming NSP14-NSP10 complex as a translation inhibitor. This leads to the failure innate immunity function against SARS CoV-2 [Hsu et al., 2021]. Undermining of innate immunity also affects the adaptive immune response.

Adaptive defence against viral attack is taken into action by immune cell mediated and humoral immunity, namely antibodies. But the contagion exhibits a carefully designed the pathway of escape from antibody mediated neutralization especially using mutations of the spike protein. Neutralizing antibodies are highly specific towards the viral epitope of the spike’s RBD. Mutations in this area notably modifies the affinity of antibodies towards its viral epitope and reduction in epitope-binding affinity helps the virus to escape from antibody mediated neutralization. N501Y mutation in the alpha strain has been detected to be culprit behind moderately increased neutralizing antibody escape in comparison to the ancestral strain [Supasa et al., 2021; Torbati et al., 2021].

Humoral immunity is extensively intertwined with cell-mediated immunity. After 3-6 days of pathogen incursion, heavy production of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG occurs from B cells in response to antigen presentation. IgM is recognised as the primary antibody response against viral invasion whereas high affinity IgG is entitled as the secondary response crucial for long term immunological memory [Low et al., 2021]. Release of these immunoglobulins eventually upsurges release of inflammatory cytokine levels to ward off the pathogen. Secretion of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, Interleukin (IL) 1 and 6 trigger T cells. Thus, cell mediated immunity controlled by helper (CD4+) and killer T (CD8+) cells comes into act. Cascade of stimulations by the helper T cells further activate and synchronize the function of other immune effector cells like macrophages, including B cells too [Low et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2017]. However, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines can on the contrary be accountable for T cell exhaustion. Interaction of Tumour Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) with Tumour Necrosis Factor receptor1 (TNFR1) receptor on T cells can direct T cells to undergo apoptosis. While dysregulated secretion of IL 10 and 6 can also be responsible for significant reduction of T cells [Diao et al., 2020]. A study reveals that over secretion of TNF-α is also associated with the substantial inhibition of Bcl-6+TFH (follicular helper T lymphocytes) differentiation. This phenomenon can make the outcomes of T cell mediated B cell activation largely ineffective, due to huge loss of germinal centre B cell formation. However, non-germinal B cells can thrive in this condition, yet those are not efficient in providing long term immunological memory as well as high-affinity B cells [Kaneko et al., 2020]. Thus, COVID-19 potentially crumples down cell mediated immunity, along with the humoral immunity which also unsurprisingly dilapidates competent IgG production [Low et al., 2021].

Immune Response in Delta Wave

The VOC B.1.617.2, which got discovered for the first time in India around the ending of year 2020, was named “Delta” variant. Delta claimed a huge number of lives by 2021 [Kumar et al., 2022]. This strain was far more contagious than its predecessor strain (around 40-60%) and risked the lives of population having partial or no vaccination [Bian et al., 2021]. Statistics revealed the number of cases to be around 400,000 and 4000 mortalities within the first weeks of May 2021 in India, which later onwards invaded more than 40 countries throughout different continents [Biswas et al., 2022].

The major mutation in the spike protein playing behind higher transmissibility than prevalent strains and successful dodging of antibody-neutralization was D614G. In contrast to Delta, alpha and beta strains had a N501Y substitution [Lee et al., 2022].

In previous variants mutations gathered in the NTD (N-terminal domain) were a quite sensitive target for the human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). These mAbs were considered ultrapotent in neutralizing virus, inhibiting the cell-cell fusion method of infection and igniting the effector functions of the host, therefore, becoming a target for therapeutic approaches [McCallum et al., 2021]. However, a critical study elucidates the incompetence of monoclonal antibodies against delta strain. Classes of Anti-NTD and Anti-RBD mAbs failed to bind to the delta spike protein capably and were proven unsuccessful in neutralizing this variant of concern. Serum antibodies from convalescent individuals (recovered from previous COVID-19 infection) were also found futile and four-fold less effective against delta than the alpha variant. Along with the D614G and D950N mutation regulating S protein dynamics, L452R mutation on RBD also plays a vital part in antibody escape. The precise location of this mutation being on the peripheral surface of ACE-2 binding area, favours the contagion to escape from antibodies in bonus being strongly attached to the ACE-2 receptor. This strategy of accumulating mutations at peripheral region has made this variant much avoidant towards host’s immunity [Planas et al., 2021].

The mayhem of host immunity was caused due to multiple factors. Translational shutdown of antiviral proteins is accomplished by viral Nsp1 and Nsp14 (Non-Structural Protein). Sec61 regulated pathway to enter the endoplasmic reticulum gets distracted by NSP8 and 9 and barriers the whole process of host’s translation for survival [Biswas et al., 2021]. Virus associated proteins also impede IFN-I and IFN-III secretion. M protein, ORF3b, ORF6, NSP13 by withdraws the RIG-I/MDA-5–MAVS pathway of cytosolic ds-RNA sensing, which directly antagonizes interferon secretion [Zheng et al., 2020].

One of the key attributes of COVID-19 infection evolved to be the cytokine storm, which is described by severe malfunctioning of cytokine response. It has been associated with elevated degree of pathogenicity in patients and grew as a serious challenge for the clinicians and researchers to combat. Release of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-2, -6, -10, TNF-α, IFN-γ and Granulocyte Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) are generally factors observed in this scenario.

According to studies, discord in the time of adequate immune action roots cytokine storm in a patient. In the early phases of infection, host body loses its power of producing potent interferons (I and III) to fight back the pathogen and simultaneously keeps secreting IL-6 and other chemokines. This leaves a cue for pro-inflammatory response [Blanco-Melo et al., 2020]. Role of IL-6 becomes relevant in delta wave too, as reports describe elevated amount of IL-6 marks disease severity [Hong et al., 2022]. This phenomenon facilitates viral replication and growth of infection. In later stages, by the time body regains its power to defend, load of infection heightens and to counteract it body starts mounting exaggerated and uncontrolled immune response [Zanza et al., 2022].

A balanced response of the Th1 and Th2 cytokines is desirable. Immune exaggeration is a consequence of Th2 activity upliftment, while polarization towards Th1 activity can tactfully perform viral clearance [Gil-Etayo et al., 2021; Neidleman et al., 2020; Roncati et al., 2020]. Th2 cytokine IL10 potentially impedes the functionality of Th1 subset and results in poor convalescence of patients [Biswas et al., 2022; Gil-Etayo et al., 2021]. However, some studies found that being an anti-inflammatory cytokine, deficiency of IL10 led to increased disease severity in patients. Thus, the role of IL10 in the orchestration of cytokine storm remains fuzzy due to contradictory reports and comprehensive quantification of other cytokines involved could help clinicians to map the disease better [Elbadawy et al., 2023]. Both the IL10 and IL4 allows degranulation and aggregation of eosinophils and basophils in the lungs causing severe impairment of alveoli [Biswas et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2020; Weiskopf et al., 2020; Roncati et al., 2020]. The final outcome of alveolar congestion and capillary haemorrhage becomes consolidation of lungs [Geng et al., 2021].

Focusing on the damage of cell mediated immunity it is crucial to throw light on antigen presentation and immune surveillance. Viral infection is signalled or presented to cytotoxic T cell (CD8+) by MHC-I molecules. In recognition of the antigenic peptides the infected host cell is killed using perforins, granzymes, Fas Ligand (FasL), which are released by the cytotoxic T lymphocytes [Berke., 1995]. As this pathway is vital for precise viral eradication, downregulation of antigen presentation remains a lucrative catch for SARS-CoV-2. Studies discovered that fighting against COVID-19 became even tougher in dampened MHC-I regulation which occurs under the effect of Open Reading Frame 8 (ORF8) viral protein by means of autophagic pathways. Cell which were exposed to ORF8 became more resistant to cytotoxic lysis and similarly ORF8 knocked down cells were sensitive to cytotoxicity. ORF8 selectively targets Major Histocompatibility Complex-I (MHC-I) for lysosomal degradation in an autophagy-mediated pathway where ORF8 gets rightly attached to MHC-I molecule and allows it to get channelised towards autophagosome or lysosome [Zhang et al., 2021]. However, a report has been published stating the failure of ORF8 in downregulating MHC-I in case of delta variant. It shows that deletion mutations like Asp119 and Phe120 in delta variant had impaired ORF8 dimer formation and structural unsteadiness led to poor affinity towards MHC-I molecules, thus, indicating better host adaptation in case of presenting the SARS-CoV-2 antigen [Chaudhari et al., 2022]. In silico studies also support this phenomenon by surmising the impact of delta on allele specific of HLA-peptide-binding affinity which has occurred in quite diminished manner due to heavy load of mutation [Augusto and Hollenbach, 2022].

Immune Response in Omicron Wave

Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) became a reason for global concern at a later stage of the pandemic. Though having five sub-lineages (BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, BA.5) circulating in the population, in general omicron variant is associated with highest degree of neutralizing antibody escape due to heavy load of mutation on its spike protein [Dhawan et al., 2022 (A); Tan et al., 2022]. Omicron was first recorded in Botswana, South Africa and showed 32 amino acid mutation in the spike protein. Reports observed that BA.1 and BA.2 had highest escape from neutralization of host antibodies in comparison to any other sarbecovirus and mutations which contributed to this attribute are found to be G339D, S371L/F, S373P, S375F, R408S, D406N [Tan et al., 2022].

The immunological scenario of the pandemic takes a turn in emergence of this variant. Changes in the genome of this variant are deeply related to an evolutionary circumstance and manifestation of those alterations became accountable for the outcome of significant host-virus paradigm. Taking note on the evolutionary point, bats act as the reservoir host for many sarbecovirus. Being a reservoir, bats develop appropriate interferon rich environment to defend themselves against sarbecovirus infection. This makes sarbecovirus already prepared for interferon attack. As human beings do not possess such constitutive immune environment, upon infection of bat sarbecovirus, human host IFN response gets overawed [Schountz et al., 2017]. Such environment in human host aided in evolution of omicron in different manner under immune selection than its ancestral sarbecovirus, acquiring a great degree of nAb escape [Tan et al., 2022].

Along with master skills in escaping immune action omicron variant has a very high transmissibility which is also being considered as manifestation of a vital evolutionary event during the pandemic [Dhawan et al., 2022 (B)]. The evasion pathway of omicron significantly differs from delta and alpha, which hints a possibility of host jumping occurred amidst the pandemic. At first it was hypothesized that omicron either spread cryptically in human population or might have evolved in patients with immune-compromised environment. However, a study by Wei et al rules out other hypotheses and reveals that the nature of mutations gathered in the omicron’s progenitor has been much likely to be taken place in a cell of a mouse rather than humans. This phenomenon suggests a trail of infection by omicron progenitor into mouse body which acquired significant mutations and jumped back to human hosts, evolving as omicron variant. Thus, the interspecific course of evolution has affected the mode of human host cell invasion route [Wei et al., 2021]. In prevalent strains, the virus targeted the ACE-2 receptor as a key to access host cell, while omicron made it to an endosomal manner of entry, neglecting the function of TMPRSS2 protease. The pathway of endosomal fusion most probably gets facilitated by a geometric re-structuring of the S1-S2 protein cleavage site of the viral spike protein. In addition to the infective nature of the omicron strain, modification of this route of infection further reduced the pathogenicity of the contagion [Fantini et al., 2022].

Briefing all the evolutionary changes it is of no qualm that antibody mediated immune response under omicron variant infection is rendered ineffective [Mukherjee et al., 2022]. However, cell mediated immune response responsibly fights omicron infection and T cells are considered as the prime warriors of this wing of immunity. Disease severity is detected to be notably reduced when T cells are activated as most of the mutations are in the spike, which are expected to be unable of disrupting cell-mediated immunity [May et al., 2021]. In exposure to prior infection of coronavirus, 70-80% T cells were found to be highly cross-reactive to omicron, in spite of having a great escape from antibody neutralization. SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell epitopes are distributed throughout the spike region which hints its response to be extensively directed towards the conserved regions, which may limit viral evasion from T cell [Keeton et al., 2022]. Though, it must not be overlooked that there are additional 20 mutations in other proteins associated with omicron variant which can surpass T cell immunity [Grifoni et al., 2021]. Nevertheless, the role of CD8+ is quite promising yet, Naranbhai et al exposes the abolishment of CD8+ recognition under omicron infection in 15% of the test population, which may also indicate elevated clinical severity in some patients [Naranbhai et al., 2022]. HLA binding and antigen presentation has been predicted to be altered by omicron’s 29 protein mutations, in which affinity of 143 peptide-HLA class I along with 85 peptide-HLA of class II pairs gets changed. Strikingly, in comparison to delta, omicron has much higher brunt on this HLA-peptide binding [Augusto and Hollenbach, 2022]. Other supporting reports also provide data that elucidates significant reduction of both CD4+ and CD8+ cell responses, in which former has shown a reduction of 14-30%, whereas similarly latter showed 17-25% median reduction [Keeton et al., 2022].

Omicron is a variant of B cell immunity escape [Barros-Martins et al., 2023]. However, some roles of B cells are yet to be exposed, which are capable of obstructing the contagion. Far before the pandemic occurred, sequential seasonal attacks of coronavirus were quite frequent in human population. Exposure of seasonal coronavirus infection gave rise to two sets of compartments of cross-reactive, resting switched memory B cells (CD27- and CD27+) which pre-existed even before omicron infection. These memory B cells were cross reactive to non-RBD regions of both the omicron and wild type SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan strain). As greater homology lies in spike of seasonal coronavirus with the non-RBD region of omicron and Wuhan strain, these compartments get abundant anti-spike B cells due to a pre-pandemic involvement [Perugino et al., 2022].

Comparison of Invasion Mechanisms and Corresponding Pathological Outcomes in Variants

The trends of immune response have changed over the course of the pandemic in harmony with the rapid evolutionary waves of new variants. Critical parameters of utmost concern for global health were pathogenicity and transmissibility of the virus. As, pathogenicity correlates to rate of hospitalization, the trend of clinical severity was epidemiologically monitored by keeping track on the rate of hospitalization and increase in pathogenicity exhibits higher rates of hospitalization in a population. As discussed, mutations on the spike protein effectively manipulates the state of the pathogenicity and the transmissibility of a variant and correspondingly amino acid substitutions on the S protein have caused highest degree of pathogenicity in the delta strain and lowest in the omicron variant.

Epidemiological studies evidently illustrate (a study conducted in Spain) a detailed comparative statistical scenario of COVID-19 waves. As delta peaked in clinical severity due to mutations like L452R, T478K, K417N, alpha showed a 43% decrease in the probability of hospitalization, whereas Omicron exhibited a 72% decrease, when compared to delta. [Varea-Jiménez et al, 2022; Dhawan et al, 2022 [C]].

As per the virological perspectives are concerned, comparison among the structures of spike protein of each variant requires greater focus for better understanding of pathological outcomes. Both the spike proteins of alpha and delta variants are shown in ribbon diagram in RBD-up conformation [Meng et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021]. Figure [2] also represents a structural map of mutations of the ectodomain of the omicron variant [Ye et al., 2022]. In the alpha strain 23 mutations were noted in the viral genome, among which seven mutations were considered crucial for the variant [Sanches et al, 2021; Lubinski et al, 2022]. Delta strain had around 13 mutations in the spike genes [Gupta et al., 2020]. While the omicron variant possessed unusually high amount of mutational load (approximately 32 mutations) on its spike protein [Vitiello et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022]. These alterations are also responsible for impacting the transmissibility of the variants. Reports elucidate that, mutations such as D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, E484A, T951, G142D has caused heightened transmissibility in the omicron variant, by cumulatively altering its route of evasion and enhancing the ability to escape antibody neutralization much more efficiently than its ancestors [Dhawan et al., 2022[B]; Dhawan et al., 2022 [C]].

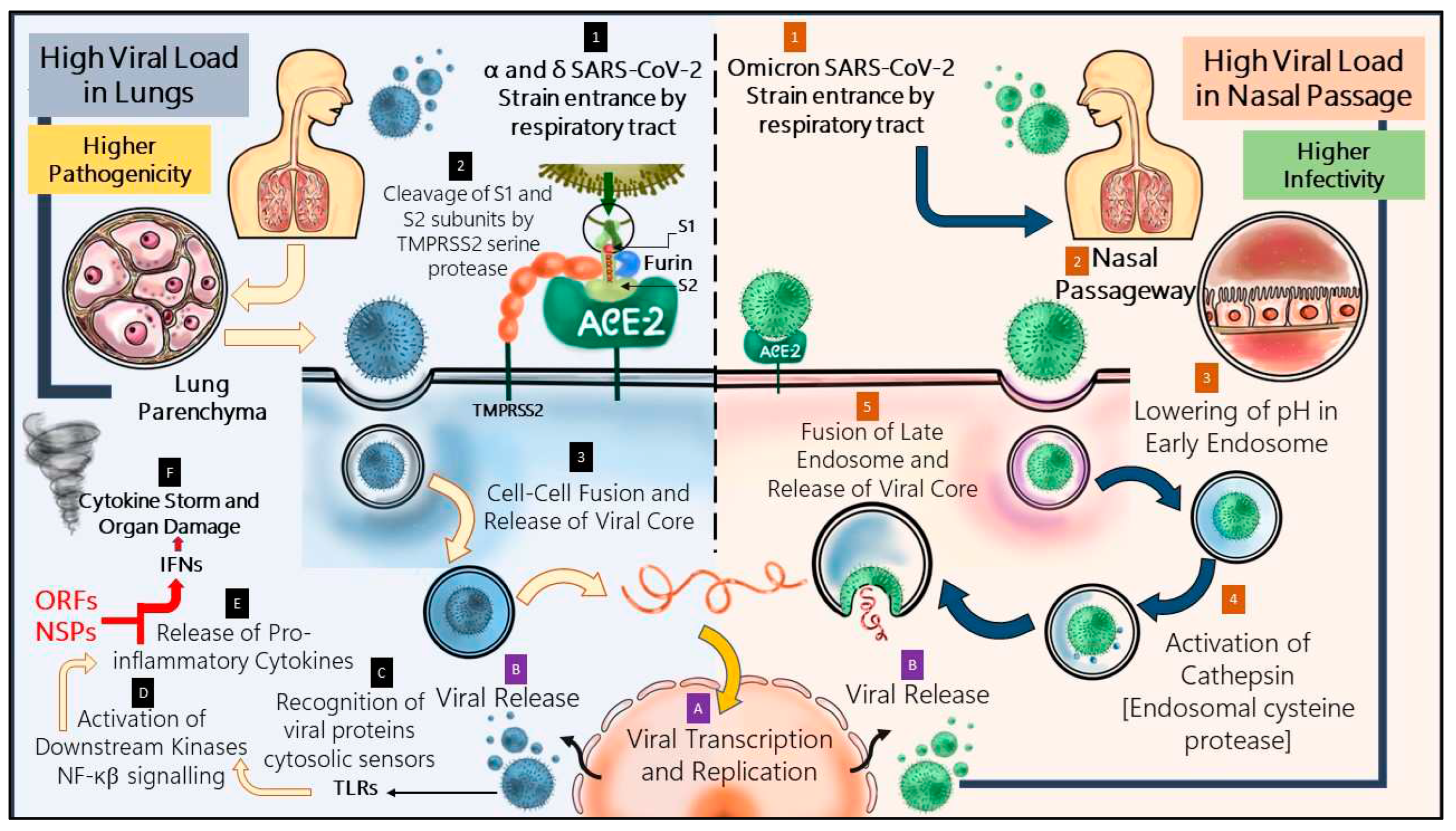

The mechanistic pathway of evasion of omicron is described in the

Figure 3 and has been compared with the pathway followed by its prevalent strains. A shift from ACE-2-TMPRSS2 mediated pathway to endosomal entrance pathway has significantly affected the pathogen’s nature of infection.

In case of the former strains, the virus could access the lung parenchyma by means of ACE-2 receptor which is also widely present in different vital human organs [Li et al., 2020]. Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection is often associated with syncytial pneumocyte formation. Whenever a COVID-affected cell presents spike protein on its surface, which starts interacting with the ACE-2 of adjacent cells, it gives rise to cellular syncytia. Formation of these lets the virus to start a new life cycle and reproduce more, which directly indicate heavier pathogenicity. The alpha variant led to larger sized syncytia formation in greater number than the ancestral strain and delta showed augmented fusogenicity, causing severe COVID-19 infection [Rajah et al., 2021]. However, in case of omicron, S1-S2 cleavage by TMPRSS2 is heavily impaired and entrance occurs majorly through cellular endosomal pathway, depending more upon cathepsins [Meng et al., 2022; Hui et al., 2022]. Furthermore, formation of cellular syncytia gets compromised in inactivity of TMPRSS2 and pathogenicity of the virion is therefore lessened to a great extent [Meng et al., 2022].

The location of infection also plays an interesting role in changing the course of COVID-19’s pathogenicity. Research indicates that omicron replicates more effectively in bronchi than lung parenchyma tissue. Nasal epithelium cultures from humans have also been reported to have surged omicron replication than prevalent strains [Hui et al., 2022]. The upper respiratory tract has lower temperature, which is quite essential to maintain optimal acidic endolysosomal pH. This phenomenon makes the endosomal entry of omicron a temperature sensitive pathway which functions efficiently in upper respiratory tract than lung parenchyma, unlike TMPRSS2 pathway which is not sensitive to temperature [AbdelMassih et al., 2022]. Thus, omicron infection localization focuses primarily on the upper respiratory tract, allowing less viral passage into other vital organs, decreasing the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 at this stage of the pandemic.

Nonetheless, omicron has diminished virulence, yet it has been detected as highly transmissible [Willette et al., 2022]. According to Hui et al, a 70-fold increase has been observed in omicron replication competence in bronchi in comparison to delta. It is suspected that higher load of viral replication in conducting airways may lead to higher amount of viral release through nasal and oral passageway while speaking or breathing. This contributes significantly in transmission through the airborne path of SARS-CoV-2 infection [Hui et al., 2022].

Conclusion

Evolutionary interplay of viral variants extensively modified the development of corresponding immune response of the human beings since the pandemic. Accumulating mutation and hypervariability at spike proteins during initial waves were being associated with increased virulence and infectivity. However, in later stages increased mutations rather aided in decreasing the pathogenicity, yet compensating with significantly high transmissibility. This has enabled the human population to cope up with severe clinical manifestations due to SARS-CoV-2 in great extent along with normalization of social protocols throughout the globe, which was disrupted by pandemic. Hence, a deep-rooted understanding of evolutionary paradigms of both the systems of host and parasite is much appreciable in order to design effective clinical measures, that takes a good care of global health perspectives.

References

- Dhawan, M., Saied, A.A., Emran, T.B. and Choudhary, O.P., 2022. Emergence of omicron variant's sublineages BA. 4 and BA. 5: risks assessment and possible countermeasures. New Microbes and New Infections, 48, p.100997. [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, M., Saied, A.A., Mitra, S., Alhumaydhi, F.A., Emran, T.B. and Wilairatana, P., 2022. Omicron variant (B. 1.1. 529) and its sublineages: What do we know so far amid the emergence of recombinant variants of SARS-CoV-2?. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, p.113522.

- Dhawan, M., Sharma, A., Priyanka, N., Thakur, N., Rajkhowa, T.K. and Choudhary, O.P., 2022. Delta variant (B. 1.617. 2) of SARS-CoV-2: Mutations, impact, challenges and possible solutions. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(5), p.2068883.

- AbdelMassih, A., Sedky, A., Shalaby, A., Shalaby, A.F., Yasser, A., Mohyeldin, A., Amin, B., Saleheen, B., Osman, D., Samuel, E. and Abdelfatah, E., 2022. From HIV to COVID-19, Molecular mechanisms of pathogens’ trade-off and persistence in the community, potential targets for new drug development. Bulletin of the National Research Centre, 46(1), pp.1-10.

- Acharya, D., Liu, G. and Gack, M.U., 2020. Dysregulation of type I interferon responses in COVID-19. Nature Reviews Immunology, 20(7), pp.397-398. [CrossRef]

- Augusto, D.G. and Hollenbach, J.A., 2022. HLA variation and antigen presentation in COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Current opinion in immunology, p.102178.

- Bakhshandeh, B., Jahanafrooz, Z., Abbasi, A., Goli, M.B., Sadeghi, M., Mottaqi, M.S. and Zamani, M., 2021. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2; Consequences in structure, function, and pathogenicity of the virus. Microbial Pathogenesis, 154, p.104831.

- Barros-Martins, J., Hammerschmidt, S.I., Morillas Ramos, G., Cossmann, A., Hetzel, L., Odak, I., Köhler, M., Stankov, M.V., Ritter, C., Friedrichsen, M. and Ravens, I., 2023. Omicron infection-associated T-and B-cell immunity in antigen-naive and triple-COVID-19-vaccinated individuals. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, p.1166589. [CrossRef]

- Berke, G., 1995. The CTL's kiss of death. Cell, 81(1), pp.9-12.

- Bian, L., Gao, Q., Gao, F., Wang, Q., He, Q., Wu, X., Mao, Q., Xu, M. and Liang, Z., 2021. Impact of the Delta variant on vaccine efficacy and response strategies. Expert review of vaccines, 20(10), pp.1201-1209. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B., Chattopadhyay, S., Hazra, S., Hansda, A.K. and Goswami, R., 2022. COVID-19 pandemic: the delta variant, T-cell responses, and the efficacy of developing vaccines. Inflammation Research, pp.1-20. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B., Chattopadhyay, S., Hazra, S., Hansda, A.K. and Goswami, R., 2022. COVID-19 pandemic: the delta variant, T-cell responses, and the efficacy of developing vaccines. Inflammation Research, 71(4), pp.377-396. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Melo, D., Nilsson-Payant, B.E., Liu, W.C., Uhl, S., Hoagland, D., Møller, R., Jordan, T.X., Oishi, K., Panis, M., Sachs, D. and Wang, T.T., 2020. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell, 181(5), pp.1036-1045.

- Chaudhari, A.M., Singh, I., Joshi, M., Patel, A. and Joshi, C., 2023. Defective ORF8 dimerization in SARS-CoV-2 delta variant leads to a better adaptive immune response due to abrogation of ORF8-MHC1 interaction. Molecular Diversity, 27(1), pp.45-57.

- Diao, B., Wang, C., Tan, Y., Chen, X., Liu, Y., Ning, L., Chen, L., Li, M., Liu, Y., Wang, G. and Yuan, Z., 2020. Reduction and functional exhaustion of T cells in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Frontiers in immunology, p.827. [CrossRef]

- Elbadawy, H.M., Khattab, A., El-Agamy, D.S., Eltahir, H.M., Alhaddad, A., Aljohani, F.D., Almuzaini, T.M., Abouzied, M.M. and Aldhafiri, A., 2023. IL-6 at the center of cytokine storm: Circulating inflammation mediators as biomarkers in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, p.e24881. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, J., Yahi, N., Colson, P., Chahinian, H., La Scola, B. and Raoult, D., 2022. The puzzling mutational landscape of the SARS-2-variant Omicron. Journal of medical virology, 94(5), pp.2019-2025.

- Geng, J., Chen, L., Yuan, Y., Wang, K., Wang, Y., Qin, C., Wu, G., Chen, R., Zhang, Z., Wei, D. and Du, P., 2021. CD147 antibody specifically and effectively inhibits infection and cytokine storm of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants delta, alpha, beta, and gamma. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 6(1), p.347.

- Gil-Etayo, F.J., Suàrez-Fernández, P., Cabrera-Marante, O., Arroyo, D., Garcinuño, S., Naranjo, L., Pleguezuelo, D.E., Allende, L.M., Mancebo, E., Lalueza, A. and Díaz-Simón, R., 2021. T-helper cell subset response is a determining factor in COVID-19 progression. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 11, p.624483.

- Gomes, C.P., Fernandes, D.E., Casimiro, F., Da Mata, G.F., Passos, M.T., Varela, P., Mastroianni-Kirsztajn, G. and Pesquero, J.B., 2020. Cathepsin L in COVID-19: from pharmacological evidences to genetics. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 10, p.589505. [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A., Sidney, J., Vita, R., Peters, B., Crotty, S., Weiskopf, D. and Sette, A., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 human T cell epitopes: Adaptive immune response against COVID-19. Cell host & microbe, 29(7), pp.1076-1092.

- Gupta, A.M., Chakrabarti, J. and Mandal, S., 2020. Non-synonymous mutations of SARS-CoV-2 leads epitope loss and segregates its variants. Microbes and infection, 22(10), pp.598-607.

- Hong, M.Z., Qiu, R., Chen, W., Lin, H., Xing, Q.Q., Dong, X., Pan, J.S. and Li, Q., 2022. Different clinical features of children and adults in regional outbreak of Delta COVID-19. BMC Infectious Diseases, 22(1), pp.1-7. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., Zhao, J., Martin, W., Kallianpur, A., Chung, M.K., Jehi, L., Sharifi, N., Erzurum, S., Eng, C. and Cheng, F., 2020. New insights into genetic susceptibility of COVID-19: an ACE2 and TMPRSS2 polymorphism analysis. BMC medicine, 18, pp.1-8. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., Zhang, L., Fan, G., Xu, J., Gu, X. and Cheng, Z., 2020. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The lancet, 395(10223), pp.497-506.

- Huang, Y., Yang, C., Xu, X.F., Xu, W. and Liu, S.W., 2020. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 41(9), pp.1141-1149.

- Hui, K.P., Ho, J.C., Cheung, M.C., Ng, K.C., Ching, R.H., Lai, K.L., Kam, T.T., Gu, H., Sit, K.Y., Hsin, M.K. and Au, T.W., 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature, 603(7902), pp.715-720.

- Kaneko, N., Kuo, H.H., Boucau, J., Farmer, J.R., Allard-Chamard, H., Mahajan, V.S., Piechocka-Trocha, A., Lefteri, K., Osborn, M., Bals, J. and Bartsch, Y.C., 2020. Loss of Bcl-6-expressing T follicular helper cells and germinal centers in COVID-19. Cell, 183(1), pp.143-157. [CrossRef]

- Keeton, R., Tincho, M.B., Ngomti, A., Baguma, R., Benede, N., Suzuki, A., Khan, K., Cele, S., Bernstein, M., Karim, F. and Madzorera, S.V., 2022. T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike cross-recognize Omicron. Nature, 603(7901), pp.488-492.

- Kim, J.E., Heo, J.H., Kim, H.O., Song, S.H., Park, S.S., Park, T.H., Ahn, J.Y., Kim, M.K. and Choi, J.P., 2017. Neurological complications during treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea), 13(3), pp.227-233. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, Y., Hayashi, H., Matsuyama, T., Sato, H. and Yamamoto, N., 2012. Retrovirus entry by endocytosis and cathepsin proteases. Advances in virology, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Thambiraja, T.S., Karuppanan, K. and Subramaniam, G., 2022. Omicron and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2: a comparative computational study of spike protein. Journal of medical virology, 94(4), pp.1641-1649.

- Lee, K.S., Wong, T.Y., Russ, B.P., Horspool, A.M., Miller, O.A., Rader, N.A., Givi, J.P., Winters, M.T., Wong, Z.Y., Cyphert, H.A. and Denvir, J., 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant induces enhanced pathology and inflammatory responses in K18-hACE2 mice. Plos one, 17(8), p.e0273430.

- Li, M.Y., Li, L., Zhang, Y. and Wang, X.S., 2020. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infectious diseases of poverty, 9(02), pp.23-29.

- Low, Z.Y., Yip, A.J.W., Sharma, A. and Lal, S.K., 2021. SARS coronavirus outbreaks past and present—a comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and its predecessors. Virus genes, 57(4), pp.307-317.

- Lubinski, B., Fernandes, M.H., Frazier, L., Tang, T., Daniel, S., Diel, D.G., Jaimes, J.A. and Whittaker, G.R., 2022. Functional evaluation of the P681H mutation on the proteolytic activation of the SARS-CoV-2 variant B. 1.1. 7 (Alpha) spike. Iscience, 25(1), p.103589.

- May, D.H., Rubin, B.E., Dalai, S.C., Patel, K., Shafiani, S., Elyanow, R., Noakes, M.T., Snyder, T.M. and Robins, H.S., 2021. Immunosequencing and epitope mapping reveal substantial preservation of the T cell immune response to Omicron generated by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. medRxiv, pp.2021-12.

- McCallum, M., De Marco, A., Lempp, F.A., Tortorici, M.A., Pinto, D., Walls, A.C., Beltramello, M., Chen, A., Liu, Z., Zatta, F. and Zepeda, S., 2021. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell, 184(9), pp.2332-2347.

- Meng, B., Abdullahi, A., Ferreira, I.A., Goonawardane, N., Saito, A., Kimura, I., Yamasoba, D., Gerber, P.P., Fatihi, S., Rathore, S. and Zepeda, S.K., 2022. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature, 603(7902), pp.706-714.

- Meng, B., Kemp, S.A., Papa, G., Datir, R., Ferreira, I.A., Marelli, S., Harvey, W.T., Lytras, S., Mohamed, A., Gallo, G. and Thakur, N., 2021. Recurrent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 spike deletion H69/V70 and its role in the Alpha variant B. 1.1. 7. Cell reports, 35(13), p.109292.

- Mukherjee, A.G., Wanjari, U.R., Murali, R., Chaudhary, U., Renu, K., Madhyastha, H., Iyer, M., Vellingiri, B. and Gopalakrishnan, A.V., 2022. Omicron variant infection and the associated immunological scenario. Immunobiology, p.152222. [CrossRef]

- Murira, A. and Lamarre, A., 2016. Type-I interferon responses: from friend to foe in the battle against chronic viral infection. Frontiers in immunology, 7, p.609. [CrossRef]

- Naranbhai, V., Nathan, A., Kaseke, C., Berrios, C., Khatri, A., Choi, S., Getz, M., Tano-Menka, R., Ofoman, O., Gayton, A. and Senjobe, F., 2022. T cell reactivity to the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is preserved in most but not all prior infected and vaccinated individuals (preprint).

- Neidleman, J., Luo, X., Frouard, J., Xie, G., Gill, G., Stein, E.S., McGregor, M., Ma, T., George, A.F., Kosters, A. and Greene, W.C., 2020. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells exhibit phenotypic features of helper function, lack of terminal differentiation, and high proliferation potential. Cell Reports Medicine, 1(6), p.100081.

- Perugino, C.A., Liu, H., Feldman, J., Hauser, B.M., Jacob-Dolan, C., Nathan, A., Zhou, Z., Kaseke, C., Tano-Menka, R., Getz, M.A. and Senjobe, F., 2022. Preferential expansion upon boosting of cross-reactive “pre-existing” switched memory B cells that recognize the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant Spike protein. medRxiv, pp.2021-12.

- Pišlar, A., Mitrović, A., Sabotič, J., Pečar Fonović, U., Perišić Nanut, M., Jakoš, T., Senjor, E. and Kos, J., 2020. The role of cysteine peptidases in coronavirus cell entry and replication: The therapeutic potential of cathepsin inhibitors. PLoS pathogens, 16(11), p.e1009013.

- Planas, D., Veyer, D., Baidaliuk, A., Staropoli, I., Guivel-Benhassine, F., Rajah, M.M., Planchais, C., Porrot, F., Robillard, N., Puech, J. and Prot, M., 2021. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature, 596(7871), pp.276-280.

- Rajah, M.M., Hubert, M., Bishop, E., Saunders, N., Robinot, R., Grzelak, L., Planas, D., Dufloo, J., Gellenoncourt, S., Bongers, A. and Zivaljic, M., 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants display enhanced Spike-mediated syncytia formation. The EMBO journal, 40(24), p.e108944.

- Roncati, L., Nasillo, V., Lusenti, B. and Riva, G., 2020. Signals of T h 2 immune response from COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care. Annals of hematology, 99, pp.1419-1420.

- Sanches, P.R., Charlie-Silva, I., Braz, H.L., Bittar, C., Calmon, M.F., Rahal, P. and Cilli, E.M., 2021. Recent advances in SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and RBD mutations comparison between new variants Alpha (B. 1.1. 7, United Kingdom), Beta (B. 1.351, South Africa), Gamma (P. 1, Brazil) and Delta (B. 1.617. 2, India). Journal of virus eradication, 7(3), p.100054.

- Schoggins, J.W. and Rice, C.M., 2011. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Current opinion in virology, 1(6), pp.519-525. [CrossRef]

- Schountz, T., Baker, M.L., Butler, J. and Munster, V., 2017. Immunological control of viral infections in bats and the emergence of viruses highly pathogenic to humans. Frontiers in immunology, 8, p.1098. [CrossRef]

- Supasa, P., Zhou, D., Dejnirattisai, W., Liu, C., Mentzer, A.J., Ginn, H.M., Zhao, Y., Duyvesteyn, H.M., Nutalai, R., Tuekprakhon, A. and Wang, B., 2021. Reduced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.1. 7 variant by convalescent and vaccine sera. Cell, 184(8), pp.2201-2211. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.W., Chia, W.N., Zhu, F., Young, B.E., Chantasrisawad, N., Hwa, S.H., Yeoh, A.Y.Y., Lim, B.L., Yap, W.C., Pada, S.K.M. and Tan, S.Y., 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant emerged under immune selection. Nature Microbiology, 7(11), pp.1756-1761.

- Tan, C.W., Chia, W.N., Zhu, F., Young, B.E., Chantasrisawad, N., Hwa, S.H., Yeoh, A.Y.Y., Lim, B.L., Yap, W.C., Pada, S.K.M. and Tan, S.Y., 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant emerged under immune selection. Nature Microbiology, 7(11), pp.1756-1761.

- Torbati, E., Krause, K.L. and Ussher, J.E., 2021. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Viruses, 13(10), p.1911.

- Varea-Jiménez, E., Cano, E.A., Vega-Piris, L., Sánchez, E.V.M., Mazagatos, C., Rodríguez-Alarcón, L.G.S.M., Casas, I., Moros, M.J.S., Iglesias-Caballero, M., Vazquez-Morón, S. and Larrauri, A., 2022. Comparative severity of COVID-19 cases caused by Alpha, Delta or Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants and its association with vaccination. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica.

- Vitiello, A., Ferrara, F., Auti, A.M., Di Domenico, M. and Boccellino, M., 2022. Advances in the Omicron variant development. Journal of internal medicine, 292(1), pp.81-90. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C., Shan, K.J., Wang, W., Zhang, S., Huan, Q. and Qian, W., 2021. Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Journal of genetics and genomics, 48(12), pp.1111-1121.

- Weiskopf, D., Schmitz, K.S., Raadsen, M.P., Grifoni, A., Okba, N.M., Endeman, H., van den Akker, J.P., Molenkamp, R., Koopmans, M.P., van Gorp, E.C. and Haagmans, B.L., 2020. Phenotype and kinetics of SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Science immunology, 5(48), p.eabd2071.

- Willett, B.J., Grove, J., MacLean, O.A., Wilkie, C., De Lorenzo, G., Furnon, W., Cantoni, D., Scott, S., Logan, N., Ashraf, S. and Manali, M., 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nature microbiology, 7(8), pp.1161-1179.

- Williams, H., Hutchinson, D. and Stone, H., 2021. Watching Brief: The evolution and impact of COVID-19 variants B. 1.1. 7, B. 1.351, P. 1 and B. 1.617. Global Biosecurity, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Ye, G., Liu, B. and Li, F., 2022. Cryo-EM structure of a SARS-CoV-2 omicron spike protein ectodomain. Nature communications, 13(1), p.1214.

- Zanza, C., Romenskaya, T., Manetti, A.C., Franceschi, F., La Russa, R., Bertozzi, G., Maiese, A., Savioli, G., Volonnino, G. and Longhitano, Y., 2022. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: immunopathogenesis and therapy. Medicina, 58(2), p.144. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Xiao, T., Cai, Y., Lavine, C.L., Peng, H., Zhu, H., Anand, K., Tong, P., Gautam, A., Mayer, M.L. and Walsh Jr, R.M., 2021. Membrane fusion and immune evasion by the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. Science, 374(6573), pp.1353-1360.

- Zhang, Y., Chen, Y., Li, Y., Huang, F., Luo, B., Yuan, Y., Xia, B., Ma, X., Yang, T., Yu, F. and Liu, J., 2021. The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-Ι. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(23), p.e2024202118.

- Zheng, Y., Zhuang, M.W., Han, L., Zhang, J., Nan, M.L., Zhan, P., Kang, D., Liu, X., Gao, C. and Wang, P.H., 2020. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) membrane (M) protein inhibits type I and III interferon production by targeting RIG-I/MDA-5 signaling. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 5(1), pp.1-13.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).