Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

02 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review

2.1. Methodologies

2.1.1. Human-Robot Collaborative Method

2.1.2. Task Allocation

2.1.3. Reinforcement Learning

2.1.4. CPS-based Robotic Assembly Sequence Planning Approach

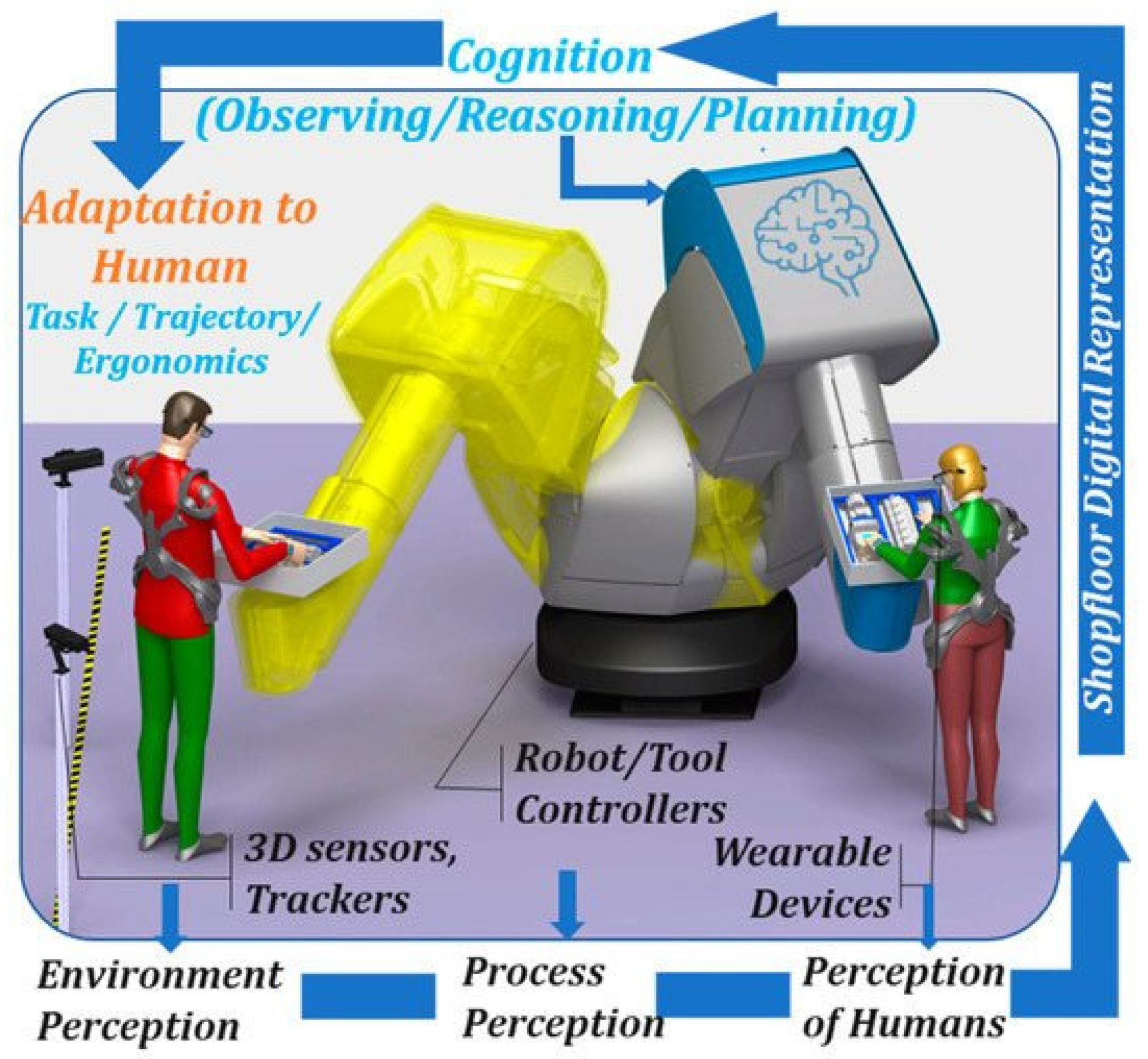

2.1.5. HRC Assembly using Artificial Intelligence and Wearable Devices

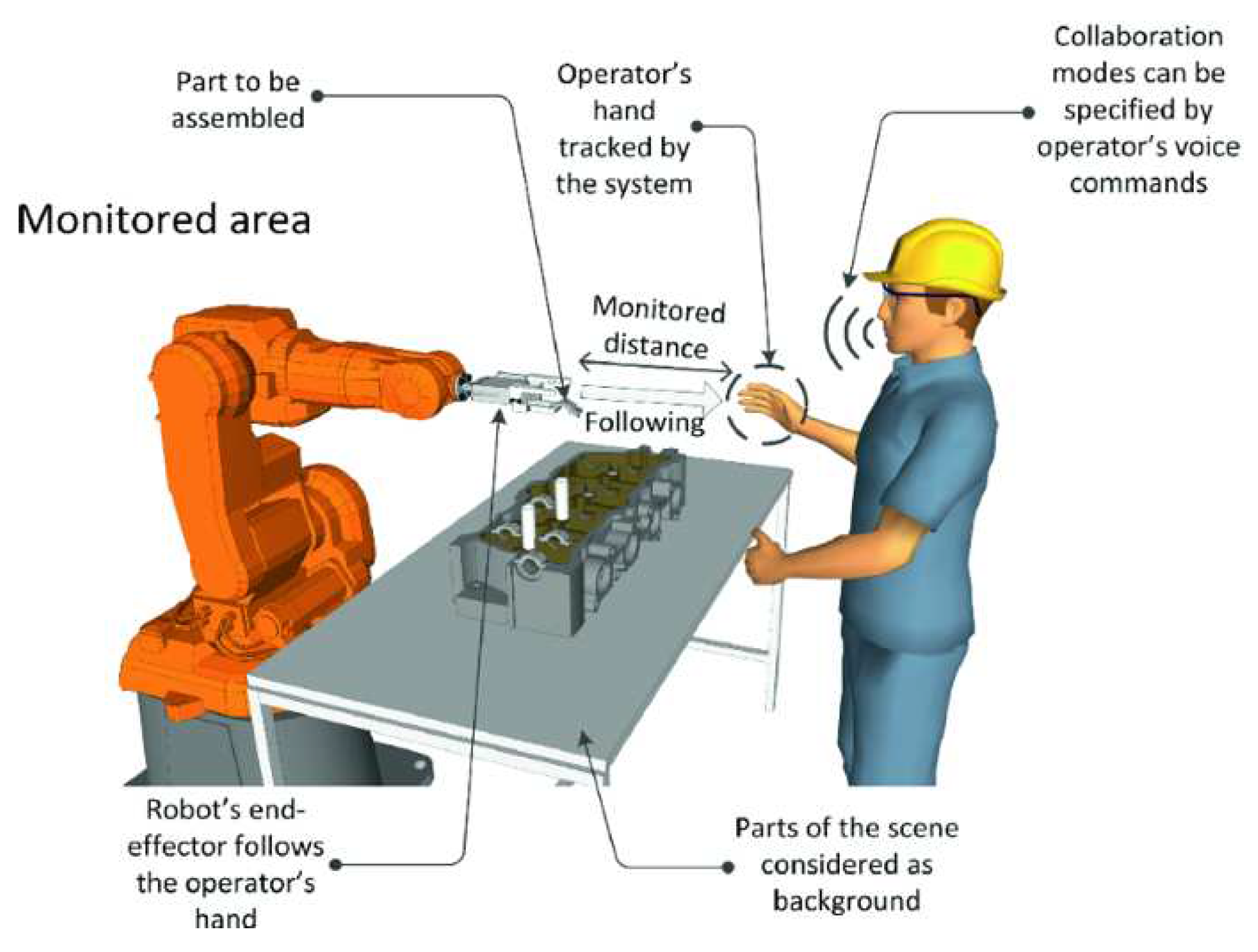

2.1.6. Programming-Free Approaches for HRC Assembly Tasks

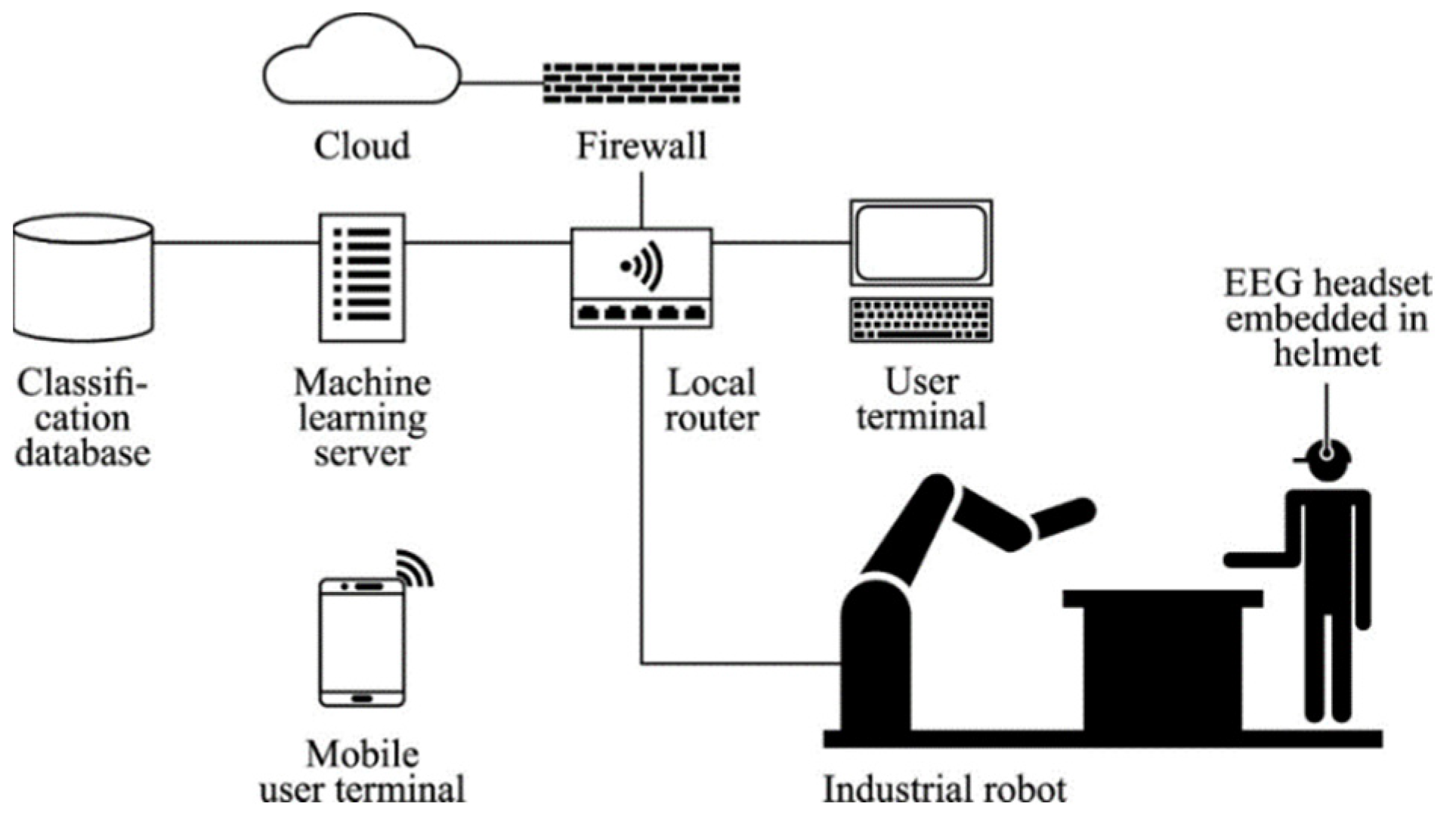

2.1.7. Intelligent Assembly enabled by Brain EEG

2.1.8. Human-Robot Collaboration for Disassembly (HRCD)

2.1.9. Human Activity Pattern Prediction for HRC Assembly Tasks

2.1.10. Intuitive and Robust Multimodal Robot Control

2.2. Experiments

3. Future Trends

4. Conclusion

References

- Xu, W.; Tang, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Pham, D.T. Disassembly sequence planning using discrete Bees algorithm for human-robot collaboration in remanufacturing. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2020, 62, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, J.E.C.; Aghezzaf, E.-H.; Claeys, D.; Limère, V.; Cottyn, J. Method for transition from manual assembly to human-robot collaborative assembly. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lv, Q.; Li, J.; Bao, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, S. A reinforcement learning method for human-robot collaboration in assembly tasks. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2022, 73, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvady, D.; Nazari, A.; Elmi, A. An Ant Colony Optimisation Based Heuristic for Mixed-model Assembly Line Balancing with Setups. Proceedings of 2020 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Gualtieri, L.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R.; Matt, D.T. Safety, ergonomics and efficiency in human-robot collaborative assembly: design guidelines and requirements. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, Q.; Xu, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, H. Sequence planning considering human fatigue for human-robot collaboration in disassembly. Procedia CIRP 2019, 83, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.V.; Kemény, Z.; Váncza, J.; Wang, L. Human–robot collaborative assembly in cyber-physical production: Classification framework and implementation. CIRP annals 2017, 66, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Huang, J.; Chang, Q. Mastering the working sequence in human-robot collaborative assembly based on reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 163868–163877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Wang, Y. Mutual trust-based subtask allocation for human–robot collaboration in flexible lightweight assembly in manufacturing. Mechatronics 2018, 54, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchettin, A.M.; Casalino, A.; Piroddi, L.; Rocco, P. Prediction of human activity patterns for human–robot collaborative assembly tasks. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 15, 3934–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Chang, S. Human-Robot Collaboration by Intention Recognition using Deep LSTM Neural Network. Proceedings of 2019 IEEE 8th International Conference on Fluid Power and Mechatronics (FPM), 2019; pp. 1390–1396.

- Chowdhury, H.; Islam, M.T. Multiple Charger with Adjustable Voltage Using Solar Panel. In Proceedings of International Conference on Mechanical Engineering and Renewable Energy 2015 (ICMERE 2015), 2015.

- Nian, R.; Liu, J.; Huang, B. A review on reinforcement learning: Introduction and applications in industrial process control. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2020, 139, 106886. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.V. Overview of human-robot collaboration in manufacturing. Proceedings of 5th international conference on the industry 4.0 model for advanced manufacturing; 2020; pp. 15–58. [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas, N.; Constantinescu, C.; Mourtzis, D. Novel Industry 4.0 Technologies and Applications. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: 2020.

- Matheson, E.; Minto, R.; Zampieri, E.G.; Faccio, M.; Rosati, G. Human–robot collaboration in manufacturing applications: a review. Robotics 2019, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, N.; Michalos, G.; Makris, S. An outlook on future hybrid assembly systems-the Sherlock approach. Procedia Cirp 2021, 97, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, N.; Togias, T.; Zacharaki, N.; Michalos, G.; Makris, S. Seamless Human–Robot Collaborative Assembly Using Artificial Intelligence and Wearable Devices. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B.S.; Lind, R.F.; Lloyd, P.D.; Noakes, M.W.; Love, L.J.; Post, B.K. The design of an additive manufactured dual arm manipulator system. Additive Manufacturing 2018, 24, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, L.; Uddin, M.; Chowdhury, H.; Martinez, J.; Sporn, I.; Dudek, B.; Tate, J. Induction Initiated Curing of Additively Manufactured Thermoset Composites. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, 2022.

- Whitney, D.; Rosen, E.; Phillips, E.; Konidaris, G.; Tellex, S. Comparing robot grasping teleoperation across desktop and virtual reality with ROS reality. In Robotics Research; Springer: 2020; pp. 335–350.

- Michniewicz, J.; Reinhart, G. Cyber-Physical-Robotics–Modelling of modular robot cells for automated planning and execution of assembly tasks. Mechatronics 2016, 34, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repta, D.; Stanescu, A.M.; Moisescu, M.A.; Sacala, I.S.; Benea, M. A cyber-physical systems approach to develop a generic enterprise architecture. Proceedings of 2014 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE), 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Napoleone, A.; Macchi, M.; Pozzetti, A. A review on the characteristics of cyber-physical systems for the future smart factories. Journal of manufacturing systems 2020, 54, 305–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, X. Resource virtualization: a core technology for developing cyber-physical production systems. Journal of manufacturing systems 2018, 47, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michniewicz, J.; Reinhart, G. Cyber-physical robotics–automated analysis, programming and configuration of robot cells based on Cyber-Physical-Systems. Procedia Technology 2014, 15, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, K.-C.; Pourhejazy, P.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-H. Cyber-physical assembly system-based optimization for robotic assembly sequence planning. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 58, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjeldum, N.; Aljinovic, A.; Crnjac Zizic, M.; Mladineo, M. Collaborative robot task allocation on an assembly line using the decision support system. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaladevi, S.C.; Propst, M.; Hofmann, M.; Hiesmair, L.; Ikeda, M.; Chitturi, N.C.; Pichler, A. Programming-free approaches for human–robot collaboration in assembly tasks. Advanced Human-Robot Collaboration in Manufacturing 2021, 283–317. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.; Wang, L. Intelligent human–robot assembly enabled by brain EEG. In Advanced Human-Robot Collaboration in Manufacturing; Springer, 2021; pp. 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri, L.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R.; Matt, D.T. An evaluation methodology for the conversion of manual assembly systems into human-robot collaborative workcells. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 38, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L. Gesture recognition for human-robot collaboration: A review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 2018, 68, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, P.; Syberfeldt, A.; Brewster, R.; Wang, L. Human-robot collaboration demonstrator combining speech recognition and haptic control. Procedia CIRP 2017, 63, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Xi, B.; Zheng, N.; Fan, J. Training more discriminative multi-class classifiers for hand detection. Pattern Recognition 2015, 48, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Wang, J.; Xie, R.; Zhou, S.; Huang, W.; Zheng, N. Semi-supervised person re-identification using multi-view clustering. Pattern Recognition 2019, 88, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fang, T.; Zhou, T.; Wang, L. Towards robust human-robot collaborative manufacturing: Multimodal fusion. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 74762–74771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L. An AR-based worker support system for human-robot collaboration. Procedia Manufacturing 2017, 11, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L. Human motion prediction for human-robot collaboration. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2017, 44, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Gao, R.X. Deep learning-based human motion recognition for predictive context-aware human-robot collaboration. CIRP annals 2018, 67, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Chang, Q.; Wang, L.; Gao, R.X. Recurrent neural network for motion trajectory prediction in human-robot collaborative assembly. CIRP annals 2020, 69, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Wang, L. Brainwaves driven human-robot collaborative assembly. CIRP annals 2018, 67, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Wang, L. Advanced Human-Robot Collaborative Assembly Using Electroencephalogram Signals of Human Brains. Procedia CIRP 2020, 93, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Cui, R.; Kang, Y.; Sun, F.; Song, R. Brain–machine interfacing-based teleoperation of multiple coordinated mobile robots. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2016, 64, 5161–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L. Collision-free human-robot collaboration based on context awareness. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2021, 67, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Giorgio, A.; Lundgren, M.; Wang, L. Procedural knowledge and function blocks for smart process planning. Procedia Manufacturing 2020, 48, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Z.; Shu, T.; Gong, R.; Wang, S.; Wei, P.; Zhu, S.-C.; Zheng, N. Learning to infer human attention in daily activities. Pattern Recognition 2020, 103, 107314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilberg, A.; Malik, A.A. Digital twin driven human–robot collaborative assembly. CIRP Annals 2019, 68, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Brem, A. Digital twins for collaborative robots: A case study in human-robot interaction. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2021, 68, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Bilberg, A. Collaborative robots in assembly: A practical approach for tasks distribution. Procedia Cirp 2019, 81, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sekiyama, K.; Huang, J.; Sun, B.; Sasaki, H.; Fukuda, T. An assembly strategy scheduling method for human and robot coordinated cell manufacturing. International Journal of Intelligent Computing and Cybernetics 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouchi, P.; Matthaiakis, A.-S.; Makris, S.; Chryssolouris, G. On a human-robot collaboration in an assembly cell. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing 2017, 30, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bänziger, T.; Kunz, A.; Wegener, K. Optimizing human–robot task allocation using a simulation tool based on standardized work descriptions. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2020, 31, 1635–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle Mura, M.; Dini, G. Designing assembly lines with humans and collaborative robots: A genetic approach. CIRP Annals 2019, 68, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Gupta, J.K.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Sadigh, D.; Bohg, J. Dynamic multi-robot task allocation under uncertainty and temporal constraints. Autonomous Robots 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Arana-Arexolaleiba, N.; Urrestilla-Anguiozar, N.; Chrysostomou, D.; Bøgh, S. Transferring Human Manipulation Knowledge to Industrial Robots Using Reinforcement Learning. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 38, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaladevi, S.C.; Plasch, M.; Pichler, A.; Ikeda, M. Towards reinforcement based learning of an assembly process for human robot collaboration. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 38, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, O.; Gupta, A.; Creus-Costa, J.; Savarese, S.; Fei-Fei, L. Surreal: Open-source reinforcement learning framework and robot manipulation benchmark. Proceedings of Conference on Robot Learning; 2018; pp. 767–782. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, A.; Wong, J.; Mandlekar, A.; Martín-Martín, R.; Zhu, Y.; Fei-Fei, L.; Savarese, S. Learning multi-arm manipulation through collaborative teleoperation. Proceedings of 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2021; pp. 9212–9219. [Google Scholar]

- Oliff, H.; Liu, Y.; Kumar, M.; Williams, M.; Ryan, M. Reinforcement learning for facilitating human-robot-interaction in manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2020, 56, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, H.; Asiabanpour, B. A Smart Circular Economy for Integrated Organic Hydroponic-Aquaponic Farming. 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).