1. Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive condition that affects pulmonary vessels, leading to the worsening of the right ventricular (RV) function[

1], which is the main prognostic factor[

2]. It is defined as an elevation of mean pulmonary arterial pressure above 20 mmHg at rest[

3]. There are 5 major types of PH, based on clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management[

3]. Group 1 PH is also called pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), and it is less common than PH groups 2 and 3[

3]. Most (50-60%) of PAH cases are idiopathic[

3]. The other most common associated conditions are connective tissue disease, congenital heart disease and portal hypertension[

3]. Treatment of underlying condition is possible for patients with PH group 2 (PH associated with left heart disease), group 3 (PH associated with lung diseases/hypoxia) and group 4 (PH associated with pulmonary obstructions)[

3], unlike for most patients with PAH.

Many small animal models are used for research in the field of PH: from older, “classical” models – chronic hypoxia (CH) and monocrotaline (MCT) – to newer models – such as Sugen5416/hypoxia (SuHx) and pulmonary artery banding (PAB)[

4]. “Classical” models induce a milder phenotype[

4]. MCT model is induced by a single injection of MCT, which leads to PH, RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling – as in human PH – but it also affects the liver, the myocardium, and the kidney, unlike human disease[

5]. CH animals are exposed to a hypoxic (generally with 10% oxygen) environment for 3-4 weeks[

5]. This causes pulmonary vascular remodelling, which improves with normoxia[

5]. Therefore, they are mostly used to investigate milder forms of PH, like group 3 PH[

6]. SuHx animals receive an injection of a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) antagonist (semaxinib or Sugen5416) and then are exposed to hypoxia, like CH animals[

5]. SuHx rats have the advantage of showing pulmonary plexiform lesions – like human PAH – as well as vascular remodelling[

5]. PAB rats or mice undergo surgery to permanently constrict the pulmonary trunk, which leads to RV remodelling, without PH

6]. They are used to evaluate the direct effects of drugs on the RV[

6].

Many drugs which improve PAH in small animals fail in clinical trials[

7]. In fact, in a recent meta-analysis, only 41 out of 522 interventions in animal models (8%) were ineffective[

8]. Only drugs targeting 3 pathways are currently approved for PAH treatment – nitric oxide, endothelin, and prostacyclin pathways – and they are all related to benefits in pulmonary vasculature[

7]. However, no approved therapy targets the RV[

9]. This difficult translation from animal models to human has multiple explanations. Most importantly, no existing animal model replicates all features of PAH in humans[

5]. Some problems are: milder phenotype (CH), damage in other organs (MCT) and absence of pulmonary vessels remodelling (PAB)[

6]. Also, depending on the model and on the methodology – type of rat/mouse, induction duration, anaesthetic used for hemodynamic evaluation – the phenotype can greatly vary[

4,

9].

The current PH animal models have similarities and differences to human PAH. Therefore, it is advantageous to use models which combine more than one hit (like SuHx), or to compare the effect of pre-clinical drugs on multiple models[

10]. Furthermore, as the main prognostic factor of PAH is the RV function[

2], direct cardioprotection – assessed by PAB – is an interesting novel option[

6], and recent studies have concomitantly evaluated potential PAH drugs in PAB plus at least one PH model. This review summarizes and analyses these studies. We aim to show the effects of multiple drugs on different animal models, with a special focus on PAB.

2. Results

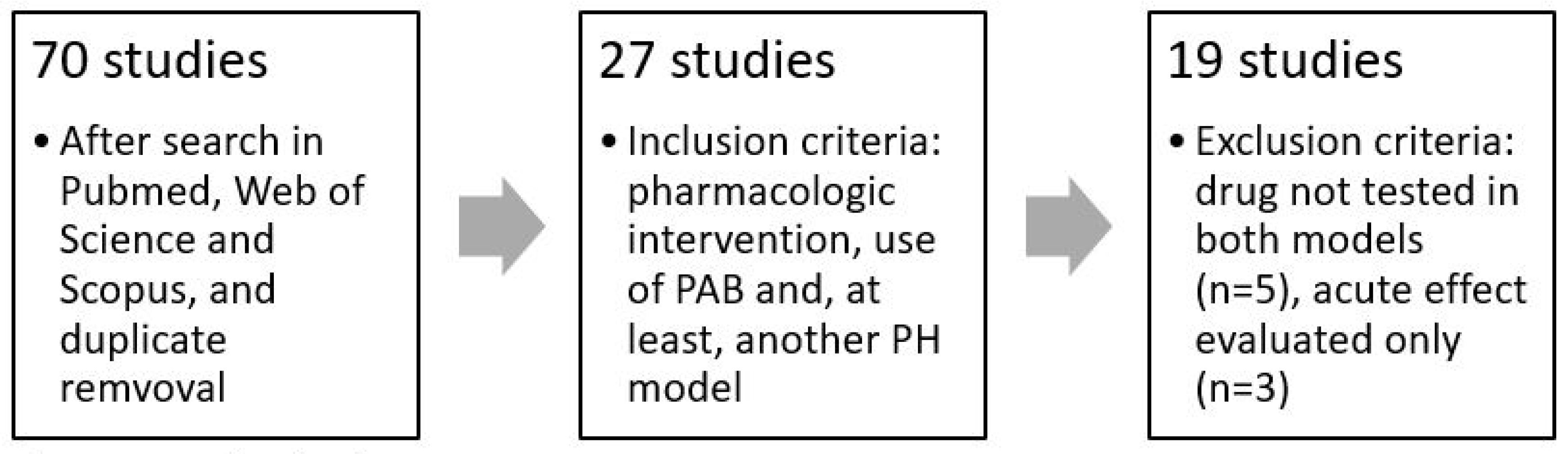

Nineteen studies were selected after applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria (

Figure 1) [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. They were published between 2009 and 2022, providing data of 20 drugs and two combinations of two drugs, with a great variety of mechanisms of action (

Table 1). Some drugs are being clinically used for PAH – such as sildenafil, tadalafil and macitentan –, and others are important in other diseases – as sacubitril/valsartan, dapagliflozin and ivabradine.

2.1. Methodology

Drugs were tested in 5 different PH/RV remodelling models: chronic hypoxia (CH), SU5416/hypoxia (SuHx), monocrotaline (MCT), monocrotaline + shunt (MCT+S), and pulmonary artery banding (PAB).

All MCT animals were rats (

Table 2) and a single MCT dose of 60 mg/Kg was administered, except in one study (30 mg/Kg)[

14], to induce PH. In two studies, rats further underwent aortocaval shunt surgery (MCT+S)[

17,

29]. Other models underwent hypoxia periods: CH and SuHx (

Table 3). Almost all these animals were exposed to air with 10% O2 for 3/4 weeks. In the start of the hypoxia period, SuHx rats were additionally injected with a VEGFR inhibitor – Sugen 5416 (semaxinib) – at a 20 or 25mg/Kg dose. PAB animals were submitted to a surgery for pulmonary artery constriction, whose grade of constriction is defined by the needle/clip size. Even for the same strains of mice/rats, the sizes greatly varied: for example, in Sprague-Dawley banded rats, the needle size ranged from 22G to 16G, and one study used a 0,9 mm diameter clip[

16].

Treatment regimens also had important variances (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Some studies adopted a preventive strategy, starting the treatment immediately after induction, while others waited some (maximum 4) weeks to start it – therapeutic strategy. Treatment duration ranged from 1 to 7 weeks, and its duration was the same for PH and PAB models in about half the studies.

Finally, an important variable for the final outcomes is the choice of the anaesthetic for hemodynamic measurements. In this regard, most (at least 10 in 19) of the experiments used isoflurane (

Table 1).

2.2. Differences of effects across different models

Overall, 63.0% of PH models results are in line with the PAB results (40.3% both improve and 22.7% both have no significant effect). This percentage is bigger for structure parameters (results of

Table 3, plus RV weight measures, TIMP-1, and RV wall thickness) for MCT rats (75.8%) than SuHx animals. The already approved therapies for PAH – macitentan, tadalafil and sildenafil – account for nearly half of the discordances (43.9%). Considering all other drugs, overall concordance raises to 73.1%, and for structure parameters in MCT rats to 92.6%.

Most used models, besides PAB, were MCT and SuHx. Concordance of MCT (65.9%) and SuHx (61.9%) with PAB results was similar.

2.3. RV structure

Fulton index and RV fibrosis were the most assessed RV structure parameters (

Table 4). Other parameters include cross-section cardiomyocyte area/diameter (CSA/CSD) and serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Most drugs showed beneficial effects in PH models, and nearly half improved RV structure parameters in both PH and PAB models.

Sildenafil, macitentan, tadalafil and the combination of the previous two had no effect on the PAB animals, except for macitentan, which ameliorated Fulton index. Sildenafil even significantly increased RV cardiomyocytes cross-sectional area from PAB group, despite decreasing it in the MCT model.

Other drugs had positive effects in PH models and PAB, and some improved no parameters (

Table 4). Urocortin-2, ivabradine, sunitinib, sorafenib, neuregulin-1 and dantrolene ameliorated multiple parameters in both types of models. Sacubitril/valsartan, dapagliflozin and RVX208 had no significant effect on these parameters, except RVX208, which further increased Fulton index in PAB rats[

29].

2.4. RV systolic function and blood pressure

RVSP and TAPSE were the most assessed RV systolic function parameters (

Table 5). Other parameters include: RV ejection fraction (RVEF), cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI) and mean arterial pressure (MAP). Most drugs ameliorated RVSP in the PH models. However, out of 18 drugs/combination of drugs, only one drug (dichloroacetate) improved RVSP in PAB animals[

24]. Dichloroacetate also attenuated pulmonary artery gradient in banded rats[

24].

Like RV structure results, sildenafil, macitentan, tadalafil and the combination of the previous two improved no RV systolic function parameters in PAB animals, except macitentan, which also ameliorated TAPSE[

20].

Urocortin-2 (MCT and PAB), GS-444217 (MCT) and neuregulin-1 (MCT) improved RVEF. Sacubitril/valsartan did not improve RVEF. Other studies lacked data for this parameter. Gallein improved CO only in the MCT group, and CI only in the PAB group (25). Sacubitril/valsartan decreased mean arterial pressure[

12] and sorafenib increased it in MCT rats[

16]. Of all drugs with data for both parameters (16 drugs), only dapagliflozin had no significant effect on neither RVSP nor TAPSE[

19].

2.5. RV diastolic function and pulmonary vascular remodelling

In most (14 out of 19) studies, researchers measured RVEDD and/or RVEDP (

Table 6). In two studies, PH induction with MCT injection did not increase RVEDD and RVEDP[

14,

15]. PAB surgery did not increase RVEDP in one study[

11]. Four studies also measured RV tau.

As a highlight, GapmeR H19 improved RVEDD and RVEDP in both MCT and PAB groups[

22]. Urocortin-2 and neuregulin-1 ameliorated RVEDD, RVEDP and tau in MCT rats[

11,

21], improving also RV end-diastolic volume and stiffness.

Most studies also provided data on pulmonary vascular remodelling (including intimal/wall thickness) and/or hemodynamics (including pulmonary artery acceleration time - PAAT, pulmonary vascular resistance - PVR and total pulmonary resistance -TPR) (

Table 7). Data from total, medial and intimal thickness resulted from analysis of many different arteriole size ranges. Most (12 out of 14) drugs improved PAAT, PVR or TPR.

Macitentan and tadalafil, alone or combined, improved TPR – but only when combined significantly decreased arteriole muscularization[

20]. Dapagliflozin and GapmeR H19 had no effect on pulmonary hemodynamics and these drugs also did not decrease mean medial thickness.

3. Discussion

We found that multiple drugs both improved pulmonary vascular hemodynamics on PH models and ameliorated RV structure and function after PAB, in rats and mice. With drugs other than ERA and PDE5i, PH models and PAB frequently exhibited similar results (73.1% concordance), particularly in the case of MCT rats for structure-related parameters (92.6%).

RVSP accounted for most differences between PH models and PAB. Only dichloroacetate improved it in banded animals, whereas 14 out of 19 drugs/combination of drugs improved RVSP in PH models. Results on RV fibrosis, on the other hand, all agreed (12 drugs). ERA and PDE5i – macitentan, sildenafil and tadalafil – improved most parameters in PH models, but almost none in PAB animals: only macitentan ameliorated two – Fulton index and TAPSE. Combination of macitentan and tadalafil improved pulmonary remodelling (arteriole muscularization), unlike both drugs on monotherapy. Unexpectedly, dapagliflozin was the only drug that improved no parameters.

3.1. Recent studies show multiple drugs with cardioprotective potential

PAB is a model used in PH research. Rats or mice undergo surgery to mechanically constrict the pulmonary trunk, developing RV dysfunction, without affecting pulmonary vessels[

30]. Therefore, if a drug improves RV function of a PAB animal, that drug likely has a direct cardioprotective action[

6]. In PH models, an improvement of RV function can also result of indirect action, through afterload reduction due to pulmonary effects, therefore the PAB model is useful to distinguish these effects[

6].

As RV function is the main determinant of prognosis in PH[

2], cardioprotection is seen as a key to improve PH treatment[

6]. Therefore, researchers search more and more for drugs with direct benefits on the RV. As the studies in this review are recent (more than half were published after 2018) and they use the PAB model, it is comprehensible that most drugs seem to directly protect the RV. Some documented cardioprotective mechanisms include pathways related to fibrosis (GS-444217, sorafenib, sunitinib), mitochondrial dysfunction (dichloroacetate), oxidative stress (MitoQ), and epigenetic alterations (GapmeR H19, RVW208, sodium valproate)[

31].

3.2. RVSP accounted for most discordances, RV fibrosis for most concordances

In the absence of RV outflow obstruction, RVSP estimates pulmonary artery systolic pressure, which can be used to calculate mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP)[

32]. PH models, like in PH in humans, present an elevated mPAP[

4]. This explains why, in all studies included in this review, PH models also exhibit an increased RVSP. Treatment with most drugs decreased RVSP, so these drugs also ameliorated mPAP.

In the PAB model, there is an obstruction to RV outflow, leading to RV pressure overload[

6], which causes RVSP elevation. All drugs but one had no effect on RVSP. Only dichloroacetate decreased RVSP in the PAB model[

24]. Dichloroacetate also reduced the pulmonary artery pressure gradient[

24]. This suggests that RVSP decrease was caused by a reduction of the pressure gradient. As PAB causes a fixed constriction on the pulmonary artery, pressure gradient should also be constant. This finding requires further research.

PH and PAB models exhibited similar RV fibrosis improvements, which suggests that these models may share common fibrotic pathways. Furthermore, 92.6% of MCT results agreed with PAB for the structure parameters, excluding ERA and PDE5i. This disagrees with a recent review on RV fibrosis due to PH, which points some differences in fibrosis location and mechanisms, although its current understanding is incomplete[

33].

3.3. Results from individual studies should be interpreted with caution

Other studies tested these drugs on the same animal models and results lacked consistency. In Schafer et al study[

26], sildenafil treatment for 3 weeks, immediately after PAB surgery in rats, had no effect in the RV function and structure, except an increase in the cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area. Rai et al[

34] found similar results after 4 weeks of treatment. Borgdorff et al[

35,

36] obtained different results, depending on the treatment regimen. Preventive strategy, with 4 weeks of sildenafil from PAB surgery day 1, resulted in RV systolic function improvement, no effect on RV diastolic function, and RV fibrosis worsening[

35]. Therapeutical strategy, based on sildenafil treatment starting 4 weeks after surgery, for 4 weeks, resulted in RV systolic and diastolic improvement, and RV fibrosis reduction[

36]. Studies on MCT rats showed improvements on RV systolic and diastolic function, and structure[

37,

38,

39].

Sildenafil, as tadalafil, is a PDE5 inhibitor. PDE5 is an abundant enzyme in the lung vasculature that degrades cGMP[

40]. Its inhibition leads to vasodilation, improving pulmonary hemodynamics[

40]. There is also evidence of direct cardioprotective effects[

41]. However, these effects may be of a lesser importance in PAH, as studies with PH models show benefits, but many with PAB reveal absence of improvements, of even worsening of RV fibrosis.

In other papers, contrary to Li et al study[

19], dapagliflozin improved RV function, RV hypertrophy, and pulmonary vascular remodelling in MCT rats[

42,

43]. Tang et al attributed the difference to the lower mortality of MCT rats and to the longer duration of treatment: 3 instead of 2 weeks[

42]. Wu et al treated rats for even longer: 5 weeks from MCT injection[

43].

Andersen et al reported that sacubitril/valsartan improved some parameters only in SuHx rats and mean arterial pressure also in PAB[

12]. In other studies, sacubitril/valsartan also improved Fulton index, RV wall thickness, fibrosis and RVEDP, in MCT and SuHx animals[

44,

45]. A study found a RVSP and RV hypertrophy reduction in PAB animals[

46].

As the study included in this review[

14] – which tested sodium valproate in MCT and PAB rats – other studies showed beneficial effects of valproic acid on CH and MCT plus CH animals[

47,

48]. A study reported multiple detrimental effects of trichostatin A[

49], another histone deacetylase inhibitor, in PAB rats: it worsened fibrosis, RV dilation, CO, TAPSE, and more parameters.

These different findings can be related to the methodology, particularly in the induction of the models. The most important factor for hemodynamic, structural and vascular worsening is the induction period, the longer, the more severe the phenotype[

4]. Additionally, older models – CH and MCT – cause milder phenotypes, some anaesthetics influence RVSP and mPAP values (greater pressure values are obtained with isoflurane), and preventive strategies lead to better outcomes than therapeutic ones[

4]. In the PAB model, a tighter constriction of the pulmonary artery causes a more severe phenotype, ranging from RV adaptative dysfunction to RV failure[

50].

3.4. Some drugs are already approved and other are being evaluated in clinical trials

Some of the drugs considered in this review are already approved for PAH. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for PH[

3] recommend the use of PDE5 inhibitors and/or ERA in some patients, depending on cardiopulmonary comorbidities and mortality risk, due to many favourable effects on clinical trials. PDE5 inhibitors improve hemodynamics, functional class and 6-minute walk distance[

51]. They also reduce mortality[

51]. In the REPAIR clinical trial, macitentan (ERA) improved pulmonary hemodynamics, RV function and structure[

52], like in SuHx rats (20). AMBITION clinical trial compared combination and monotherapy of ambrisentan – another ERA – and tadalafil[

53]. Combination therapy further reduced morbidity and improved 6-minute distance[

53].

Other drugs have been already tested in smaller clinical trials and observational studies, with positive outcomes. Dichloroacetate improved mPAP and PVR in genetically susceptible patients[

54]. Sacubitril/valsartan also reduced mPAP, in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)[

55] and preserved ejection fraction (HRpEF)[

56]. A positive effect on RV function, assessed by TAPSE, was only present in HFrEF[

55]. Ivabradine led to functional improvements in 10 PAH patients with high heart rates[

57]. Sorafenib showed improvements in patients with refractory PAH[

58]. However, in other study, without placebo group, sorafenib led to a decrease in the cardiac index and a non-significant increase in systemic blood pressure[

59].

3.5. Small findings can be important

In one article[

25], cardiac output (in mL/min) and cardiac index (mL/min/g) were assessed. Gallein treatment improved cardiac output only in MCT rats, and cardiac index only in PAB animals: the bodyweight indexing affected the results. Other studies show significant differences between the control and MCT groups (neuregulin), MCT and MCT + treatment (neuregulin), sham and PAB (ivabradine), and PAB and PAB + treatment (ivabradine). Borderline cardiac output improvements can become significant with or without indexing.

Also, unlike their monotherapy, macitentan plus tadalafil improved pulmonary vascular remodelling in MCT rats[

20]. This was the only advantage of the combination. Accordingly, in ABMITION clinical trial, combination of ERA and PDE5i had benefits compared to both monotherapies[

53].

3.6. Limitations

One limitation of this review is the absence of statistic tests. Many studies did not present the absolute values, and considering the high heterogeneity in the methods, statistic comparisons would be hard to interpret. Also, this study does not include all drugs tested on PAB model, and some research groups may have published the effects of a given drug on different models in different papers. Although it would be interesting to have a picture of all potentially cardioprotective drugs, analysing only studies which test two or more models allows to understand, for each molecule, which seem to have direct, indirect, or mixed cardioprotective effects. Furthermore, as the same research group performs the experiments on both models, heterogeneity is lower. One more limitation is the absence of drugs which are known to lack benefits on PAH. They would be useful for comparison purposes. In this study, only dapagliflozin completely lacked benefits, but even this drug showed improvements in animal models and in some patients. Finally, this review does not include all results of studies: some important outcomes may have been missed and the proportion of similarities/differences between models can be unrepresentative of the full results.

4. Materials and Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature search using online databases, including Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed/MEDLINE, without time or language limitation.

The query used was: (pulmonary hypertension OR pulmonary arterial hypertension) AND (SUGEN OR SU5416 OR (chronic hypoxia) OR monocrotaline OR MCT OR Schistosomiasis OR Schistosoma OR (Endothelin receptor-B) OR ET-B OR Angiopoeitin-1 OR Serotonin OR 5-HTT) AND (PAB OR pulmonary artery banding or PTB or pulmonary trunk banding).

4.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted in pharmacological interventions to prevent/reverse PH, tested both on a PAB group and in a PH animal model.

Studies were excluded due to acute interventions (only one treatment administration) and lack of data for PAB group and, at least, one other PH model.

4.2. Data extraction

All selected studies were carefully reviewed. We extracted data from the most assessed and important outcomes related to RV. Outcomes were divided on model induction, RV structure, RV systolic function, RV diastolic function and pulmonary vascular hemodynamics and remodelling, in order to facilitate their presentation, although some outcomes are related to more than one domain (e.g.: BNP is related to RV structure and diastolic function).

5. Conclusions

This review showed that many drugs currently under research for PAH have a cardioprotective effect on animals that may translate to humans, as well as pulmonary vascular hemodynamics and remodelling benefits. However, results of isolated studies should be interpreted with caution, as small differences in the methodology can lead to noticeable changes in the results. To improve the translational potential of drugs in this field, researchers should test them in multiple models, including PAB, while optimizing induction methods for human disease translation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., R.A. and C.B-S.; data curation, A.B..; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, R.A. and C.B-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the auspices of the Cardiovascular R&D Center–UnIC (UIDB/00051/2020 and UIDP/00051/2020) and projects RELAX-2-PAH (2022.08921.PTDC) and IMPAcT (PTDC/MED-FSL/31719/2017; POCI-01-0145-FEDER-031719).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Humbert, M., C. Guignabert, S. Bonnet, P. Dorfmuller, J. R. Klinger, M. R. Nicolls, A. J. Olschewski, S. S. Pullamsetti, R. T. Schermuly, K. R. Stenmark, and M. Rabinovitch. "Pathology and Pathobiology of Pulmonary Hypertension: State of the Art and Research Perspectives." Eur Respir J 53, no. 1 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Howard, L. S. "Prognostic Factors in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Assessing the Course of the Disease." Eur Respir Rev 20, no. 122 (2011): 236-42. [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M., G. Kovacs, M. M. Hoeper, R. Badagliacca, R. M. F. Berger, M. Brida, J. Carlsen, A. J. S. Coats, P. Escribano-Subias, P. Ferrari, D. S. Ferreira, H. A. Ghofrani, G. Giannakoulas, D. G. Kiely, E. Mayer, G. Meszaros, B. Nagavci, K. M. Olsson, J. Pepke-Zaba, J. K. Quint, G. Radegran, G. Simonneau, O. Sitbon, T. Tonia, M. Toshner, J. L. Vachiery, A. Vonk Noordegraaf, M. Delcroix, S. Rosenkranz, and Esc Ers Scientific Document Group. "2022 Esc/Ers Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension." Eur Heart J 43, no. 38 (2022): 3618-731. [CrossRef]

- Sztuka, K., and M. Jasinska-Stroschein. "Animal Models of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Data from 6126 Animals." Pharmacol Res 125, no. Pt B (2017): 201-14. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. H., J. L. Ma, D. Ding, Y. J. Ma, Y. P. Wei, and Z. C. Jing. "Experimental Animal Models of Pulmonary Hypertension: Development and Challenges." Animal Model Exp Med 5, no. 3 (2022): 207-16. [CrossRef]

- Dignam, J. P., T. E. Scott, B. K. Kemp-Harper, and A. J. Hobbs. "Animal Models of Pulmonary Hypertension: Getting to the Heart of the Problem." Br J Pharmacol 179, no. 5 (2022): 811-37. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., F. Lin, Z. Xiao, B. Sun, Z. Wei, B. Liu, L. Xue, and C. Xiong. "Investigational Pharmacotherapy and Immunotherapy of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: An Update." Biomed Pharmacother 129 (2020): 110355. [CrossRef]

- Sztuka, K., D. Orszulak-Michalak, and M. Jasinska-Stroschein. "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventions Tested in Animal Models of Pulmonary Hypertension." Vascul Pharmacol 110 (2018): 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Prisco, S. Z., T. Thenappan, and K. W. Prins. "Treatment Targets for Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." JACC Basic Transl Sci 5, no. 12 (2020): 1244-60. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, N., H. A. Ghofrani, O. Pak, S. Bonnet, S. Provencher, O. Sitbon, S. Rosenkranz, M. M. Hoeper, and D. G. Kiely. "Current and Future Treatments of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Br J Pharmacol 178, no. 1 (2021): 6-30. [CrossRef]

- Adao, R., P. Mendes-Ferreira, D. Santos-Ribeiro, C. Maia-Rocha, L. D. Pimentel, C. Monteiro-Pinto, E. P. Mulvaney, H. M. Reid, B. T. Kinsella, F. Potus, S. Breuils-Bonnet, M. T. Rademaker, S. Provencher, S. Bonnet, A. F. Leite-Moreira, and C. Bras-Silva. "Urocortin-2 Improves Right Ventricular Function and Attenuates Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Cardiovascular Research 114, no. 8 (2018): 1165-77. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S., J. B. Axelsen, S. Ringgaard, J. R. Nyengaard, J. A. Hyldebrandt, H. J. Bogaard, F. S. de Man, J. E. Nielsen-Kudsk, and A. Andersen. "Effects of Combined Angiotensin Ii Receptor Antagonism and Neprilysin Inhibition in Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure." International Journal of Cardiology 293 (2019): 203-10. [CrossRef]

- Budas, G. R., M. Boehm, B. Kojonazarov, G. Viswanathan, X. Tian, S. Veeroju, T. Novoyatleva, F. Grimminger, F. Hinojosa-Kirschenbaum, H. A. Ghofrani, N. Weissmann, W. Seeger, J. T. Liles, and R. T. Schermuly. "Ask1 Inhibition Halts Disease Progression in Preclinical Models of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 197, no. 3 (2018): 373-85. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. K., G. H. Eom, H. J. Kee, H. S. Kim, W. Y. Choi, K. I. Nam, J. S. Ma, and H. Kook. "Sodium Valproate, a Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, but Not Captopril, Prevents Right Ventricular Hypertrophy in Rats." Circulation Journal 74, no. 4 (2010): 760-70. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, R., K. Okumura, Y. Akazawa, M. Malhi, R. Ebata, M. Sun, T. Fujioka, H. Kato, O. Honjo, G. Kabir, W. M. Kuebler, K. Connelly, J. T. Maynes, and M. K. Friedberg. "Heart Rate Reduction Improves Right Ventricular Function and Fibrosis in Pulmonary Hypertension." American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 63, no. 6 (2020): 843-55. [CrossRef]

- Kojonazarov, B., A. Sydykov, S. S. Pullamsetti, H. Luitel, B. K. Dahal, D. Kosanovic, X. Tian, M. Majewski, C. Baumann, S. Evans, P. Phillips, D. Fairman, N. Davie, C. Wayman, I. Kilty, N. Weissmann, F. Grimminger, W. Seeger, H. A. Ghofrani, and R. T. Schermuly. "Effects of Multikinase Inhibitors on Pressure Overload-Induced Right Ventricular Remodeling." International Journal of Cardiology 167, no. 6 (2013): 2630-37. [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, K., Q. A. J. Hagdorn, D. E. van der Feen, A. V. Noordegraaf, P. ten Dijke, R. A. de Boer, H. J. Bogaard, M. J. Goumans, and R. M. F. Berger. "Inhibition of the Prolyl Isomerase Pin1 Improves Endothelial Function and Attenuates Vascular Remodelling in Pulmonary Hypertension by Inhibiting Tgf-Beta Signalling." Angiogenesis 25, no. 1 (2022): 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, R., K. Satoh, T. Nakata, T. Shindo, N. Kikuchi, T. Satoh, M. A. H. Siddique, J. Omura, S. Sunamura, M. Nogi, Y. Takeuchi, S. Miyata, and H. Shimokawa. "Identification of Celastrol as a Novel Therapeutic Agent for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure through Suppression of Bsg (Basigin)/Cypa (Cyclophilin a)." Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology 41, no. 3 (2021): 1205-17. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Y. Zhang, S. Wang, Y. Yue, Q. Liu, S. Huang, H. Peng, Y. Zhang, W. Zeng, and Z. Wu. "Dapagliflozin Has No Protective Effect on Experimental Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Pulmonary Trunk Banding Rat Models." Front Pharmacol 12 (2021): 756226. [CrossRef]

- Mamazhakypov, A., A. Weiß, S. Zukunft, A. Sydykov, B. Kojonazarov, J. Wilhelm, C. Vroom, A. Petrovic, D. Kosanovic, N. Weissmann, W. Seeger, I. Fleming, M. Iglarz, F. Grimminger, H. A. Ghofrani, S. S. Pullamsetti, and R. T. Schermuly. "Effects of Macitentan and Tadalafil Monotherapy or Their Combination on the Right Ventricle and Plasma Metabolites in Pulmonary Hypertensive Rats." Pulm Circ 10, no. 4 (2020): 2045894020947283. [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Ferreira, P., C. Maia-Rocha, R. Adao, M. J. Mendes, D. Santos-Ribeiro, B. S. Alves, R. J. Cerqueira, P. Castro-Chaves, A. P. Lourenco, G. W. De Keulenaer, A. F. Leite-Moreira, and C. Bras-Silva. "Neuregulin-1 Improves Right Ventricular Function and Attenuates Experimental Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Cardiovascular Research 109, no. 1 (2016): 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Omura, J., K. Habbout, T. Shimauchi, W. H. Wu, S. Breuils-Bonnet, E. Tremblay, S. Martineau, V. Nadeau, K. Gagnon, F. Mazoyer, J. Perron, F. Potus, J. H. Lin, H. Zafar, D. G. Kiely, A. Lawrie, S. L. Archer, R. Paulin, S. Provencher, O. Boucherat, and S. Bonnet. "Identification of Long Noncoding Rna H19 as a New Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Right Ventricular Failure in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Circulation 142, no. 15 (2020): 1464-84. [CrossRef]

- Pak, O., S. Scheibe, A. Esfandiary, M. Gierhardt, A. Sydykov, A. Logan, A. Fysikopoulos, F. Veit, M. Hecker, F. Kroschel, K. Quanz, A. Erb, K. Schafer, M. Fassbinder, N. Alebrahimdehkordi, H. A. Ghofrani, R. T. Schermuly, R. P. Brandes, W. Seeger, M. P. Murphy, N. Weissmann, and N. Sommer. "Impact of the Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Mitoq on Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension." European Respiratory Journal 51, no. 3 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Piao, L., Y. H. Fang, V. J. Cadete, C. Wietholt, D. Urboniene, P. T. Toth, G. Marsboom, H. J. Zhang, I. Haber, J. Rehman, G. D. Lopaschuk, and S. L. Archer. "The Inhibition of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase Improves Impaired Cardiac Function and Electrical Remodeling in Two Models of Right Ventricular Hypertrophy: Resuscitating the Hibernating Right Ventricle." J Mol Med (Berl) 88, no. 1 (2010): 47-60. [CrossRef]

- Piao, L., Y. H. Fang, K. S. Parikh, J. J. Ryan, K. M. D'Souza, T. Theccanat, P. T. Toth, J. Pogoriler, J. Paul, B. C. Blaxall, S. A. Akhter, and S. L. Archer. "Grk2-Mediated Inhibition of Adrenergic and Dopaminergic Signaling in Right Ventricular Hypertrophy Therapeutic Implications in Pulmonary Hypertension." Circulation 126, no. 24 (2012): 2859-+. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, S., P. Ellinghaus, W. Janssen, F. Kramer, K. Lustig, H. Milting, R. Kast, and M. Klein. "Chronic Inhibition of Phosphodiesterase 5 Does Not Prevent Pressure-Overload-Induced Right-Ventricular Remodelling." Cardiovascular Research 82, no. 1 (2009): 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Q., E. L. Peters, I. Schalij, J. B. Axelsen, S. Andersen, K. Kurakula, M. C. Gomez-Puerto, R. Szulcek, X. Pan, D. da Silva Goncalves Bos, R. E. J. Schiepers, A. Andersen, M. J. Goumans, A. Vonk Noordegraaf, W. J. van der Laarse, F. S. de Man, and H. J. Bogaard. "Increased Mao-a Activity Promotes Progression of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 64, no. 3 (2021): 331-43. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S., T. Yamamoto, M. Mikawa, J. Nawata, S. Fujii, Y. Nakamura, T. Kato, M. Fukuda, T. Suetomi, H. Uchinoumi, T. Oda, S. Okuda, T. Okamura, S. Kobayashi, and M. Yano. "Stabilization of Ryr2 Maintains Right Ventricular Function, Reduces the Development of Ventricular Arrhythmias, and Improves Prognosis in Pulmonary Hypertension." Heart Rhythm 19, no. 6 (2022): 986-97. [CrossRef]

- Van der Feen, D. E., K. Kurakula, E. Tremblay, O. Boucherat, G. P. L. Bossers, R. Szulcek, A. Bourgeois, M. C. Lampron, K. Habbout, S. Martineau, R. Paulin, E. Kulikowski, R. Jahagirdar, I. Schalij, H. J. Bogaard, B. Barteld, S. Provencher, R. M. F. Berger, S. Bonnet, and M. J. Goumans. "Multicenter Preclinical Validation of Bet Inhibition for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 200, no. 7 (2019): 910-20. [CrossRef]

- Guihaire, J., H. J. Bogaard, E. Flecher, P. E. Noly, O. Mercier, F. Haddad, and E. Fadel. "Experimental Models of Right Heart Failure: A Window for Translational Research in Pulmonary Hypertension." Semin Respir Crit Care Med 34, no. 5 (2013): 689-99. [CrossRef]

- Mamazhakypov, A., N. Sommer, B. Assmus, K. Tello, R. T. Schermuly, D. Kosanovic, A. S. Sarybaev, N. Weissmann, and O. Pak. "Novel Therapeutic Targets for the Treatment of Right Ventricular Remodeling: Insights from the Pulmonary Artery Banding Model." Int J Environ Res Public Health 18, no. 16 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jang, A. Y., and M. S. Shin. "Echocardiographic Screening Methods for Pulmonary Hypertension: A Practical Review." J Cardiovasc Imaging 28, no. 1 (2020): 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Egemnazarov, B., S. Crnkovic, B. M. Nagy, H. Olschewski, and G. Kwapiszewska. "Right Ventricular Fibrosis and Dysfunction: Actual Concepts and Common Misconceptions." Matrix Biol 68-69 (2018): 507-21. [CrossRef]

- Rai, N., S. Veeroju, Y. Schymura, W. Janssen, A. Wietelmann, B. Kojonazarov, N. Weissmann, J. P. Stasch, H. A. Ghofrani, W. Seeger, R. T. Schermuly, and T. Novoyatleva. "Effect of Riociguat and Sildenafil on Right Heart Remodeling and Function in Pressure Overload Induced Model of Pulmonary Arterial Banding." Biomed Res Int 2018 (2018): 3293584. [CrossRef]

- Borgdorff, M. A., B. Bartelds, M. G. Dickinson, B. Boersma, M. Weij, A. Zandvoort, H. H. Sillje, P. Steendijk, M. de Vroomen, and R. M. Berger. "Sildenafil Enhances Systolic Adaptation, but Does Not Prevent Diastolic Dysfunction, in the Pressure-Loaded Right Ventricle." Eur J Heart Fail 14, no. 9 (2012): 1067-74. [CrossRef]

- Borgdorff, M. A., B. Bartelds, M. G. Dickinson, M. P. van Wiechen, P. Steendijk, M. de Vroomen, and R. M. Berger. "Sildenafil Treatment in Established Right Ventricular Dysfunction Improves Diastolic Function and Attenuates Interstitial Fibrosis Independent from Afterload." Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307, no. 3 (2014): H361-9. [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, R. T., K. P. Kreisselmeier, H. A. Ghofrani, H. Yilmaz, G. Butrous, L. Ermert, M. Ermert, N. Weissmann, F. Rose, A. Guenther, D. Walmrath, W. Seeger, and F. Grimminger. "Chronic Sildenafil Treatment Inhibits Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats." Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169, no. 1 (2004): 39-45. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Z. Y. Liu, and Q. Guan. "Oral Sildenafil Prevents and Reverses the Development of Pulmonary Hypertension in Monocrotaline-Treated Rats." Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 6, no. 5 (2007): 608-13. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiyuki, R., R. Tanaka, R. Fukushima, and N. Machida. "Preventive Effect of Sildenafil on Right Ventricular Function in Rats with Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Exp Anim 65, no. 3 (2016): 215-22. [CrossRef]

- Triposkiadis, F., A. Xanthopoulos, J. Skoularigis, and R. C. Starling. "Therapeutic Augmentation of No-Sgc-Cgmp Signalling: Lessons Learned from Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Heart Failure." Heart Fail Rev 27, no. 6 (2022): 1991-2003. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, D. C., S. G. Anderson, J. L. Caldwell, and A. W. Trafford. "Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors and the Heart: Compound Cardioprotection?" Heart 104, no. 15 (2018): 1244-50. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., S. Tan, M. Li, Y. Tang, X. Xu, Q. Zhang, Q. Fu, M. Tang, J. He, Y. Zhang, Z. Zheng, J. Peng, T. Zhu, and W. Xie. "Dapagliflozin, Sildenafil and Their Combination in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." BMC Pulm Med 22, no. 1 (2022): 142. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., T. Liu, S. Shi, Z. Fan, R. Hiram, F. Xiong, B. Cui, X. Su, R. Chang, W. Zhang, M. Yan, Y. Tang, H. Huang, G. Wu, and C. Huang. "Dapagliflozin Reduces the Vulnerability of Rats with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension-Induced Right Heart Failure to Ventricular Arrhythmia by Restoring Calcium Handling." Cardiovasc Diabetol 21, no. 1 (2022): 197. [CrossRef]

- Chaumais, M. C., M. R. A. Djessas, R. Thuillet, A. Cumont, L. Tu, G. Hebert, P. Gaignard, A. Huertas, L. Savale, M. Humbert, and C. Guignabert. "Additive Protective Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan and Bosentan on Vascular Remodelling in Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension." Cardiovasc Res 117, no. 5 (2021): 1391-401. [CrossRef]

- Clements, R. T., A. Vang, A. Fernandez-Nicolas, N. R. Kue, T. J. Mancini, A. R. Morrison, K. Mallem, D. J. McCullough, and G. Choudhary. "Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension with Angiotensin Ii Receptor Blocker and Neprilysin Inhibitor Sacubitril/Valsartan." Circ Heart Fail 12, no. 11 (2019): e005819. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi Kia, D., E. Benza, T. N. Bachman, C. Tushak, K. Kim, and M. A. Simon. "Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition Attenuates Right Ventricular Remodeling in Pulmonary Hypertension." J Am Heart Assoc 9, no. 13 (2020): e015708. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., C. N. Chen, N. Hajji, E. Oliver, E. Cotroneo, J. Wharton, D. Wang, M. Li, T. A. McKinsey, K. R. Stenmark, and M. R. Wilkins. "Histone Deacetylation Inhibition in Pulmonary Hypertension: Therapeutic Potential of Valproic Acid and Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid." Circulation 126, no. 4 (2012): 455-67. [CrossRef]

- Lan, B., E. Hayama, N. Kawaguchi, Y. Furutani, and T. Nakanishi. "Therapeutic Efficacy of Valproic Acid in a Combined Monocrotaline and Chronic Hypoxia Rat Model of Severe Pulmonary Hypertension." Plos One 10, no. 1 (2015): e0117211. [CrossRef]

- Bogaard, H. J., S. Mizuno, A. A. Hussaini, S. Toldo, A. Abbate, D. Kraskauskas, M. Kasper, R. Natarajan, and N. F. Voelkel. "Suppression of Histone Deacetylases Worsens Right Ventricular Dysfunction after Pulmonary Artery Banding in Rats." Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183, no. 10 (2011): 1402-10. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S., J. G. Schultz, S. Holmboe, J. B. Axelsen, M. S. Hansen, M. D. Lyhne, J. E. Nielsen-Kudsk, and A. Andersen. "A Pulmonary Trunk Banding Model of Pressure Overload Induced Right Ventricular Hypertrophy and Failure." J Vis Exp, no. 141 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H., Z. Brown, A. Burns, and T. Williams. "Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors for Pulmonary Hypertension." Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1, no. 1 (2019): CD012621. [CrossRef]

- Vonk Noordegraaf, A., R. Channick, E. Cottreel, D. G. Kiely, J. T. Marcus, N. Martin, O. Moiseeva, A. Peacock, A. J. Swift, A. Tawakol, A. Torbicki, S. Rosenkranz, and N. Galie. "The Repair Study: Effects of Macitentan on Rv Structure and Function in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 15, no. 2 (2022): 240-53. [CrossRef]

- Galie, N., J. A. Barbera, A. E. Frost, H. A. Ghofrani, M. M. Hoeper, V. V. McLaughlin, A. J. Peacock, G. Simonneau, J. L. Vachiery, E. Grunig, R. J. Oudiz, A. Vonk-Noordegraaf, R. J. White, C. Blair, H. Gillies, K. L. Miller, J. H. Harris, J. Langley, L. J. Rubin, and Ambition Investigators. "Initial Use of Ambrisentan Plus Tadalafil in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." N Engl J Med 373, no. 9 (2015): 834-44. [CrossRef]

- Michelakis, E. D., V. Gurtu, L. Webster, G. Barnes, G. Watson, L. Howard, J. Cupitt, I. Paterson, R. B. Thompson, K. Chow, D. P. O'Regan, L. Zhao, J. Wharton, D. G. Kiely, A. Kinnaird, A. E. Boukouris, C. White, J. Nagendran, D. H. Freed, S. J. Wort, J. S. R. Gibbs, and M. R. Wilkins. "Inhibition of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase Improves Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Genetically Susceptible Patients." Sci Transl Med 9, no. 413 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., L. Du, X. Qin, and X. Guo. "Effect of Sacubitril/Valsartan on the Right Ventricular Function and Pulmonary Hypertension in Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies." J Am Heart Assoc 11, no. 9 (2022): e024449. [CrossRef]

- Codina, P., M. Domingo, E. Barcelo, P. Gastelurrutia, D. Casquete, J. Vila, O. Abdul-Jawad Altisent, G. Spitaleri, G. Cediel, E. Santiago-Vacas, E. Zamora, M. Ruiz-Cueto, J. Santesmases, R. de la Espriella, D. A. Pascual-Figal, J. Nunez, J. Lupon, and A. Bayes-Genis. "Sacubitril/Valsartan Affects Pulmonary Arterial Pressure in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Pulmonary Hypertension." ESC Heart Fail 9, no. 4 (2022): 2170-80. [CrossRef]

- Correale, M., N. D. Brunetti, D. Montrone, A. Totaro, A. Ferraretti, R. Ieva, and M. di Biase. "Functional Improvement in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients Treated with Ivabradine." J Card Fail 20, no. 5 (2014): 373-5. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, G., M. Kataoka, T. Inami, K. Fukuda, H. Yoshino, and T. Satoh. "Sorafenib as a Potential Strategy for Refractory Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Pulm Pharmacol Ther 44 (2017): 46-49. [CrossRef]

- Gomberg-Maitland, M., M. L. Maitland, R. J. Barst, L. Sugeng, S. Coslet, T. J. Perrino, L. Bond, M. E. Lacouture, S. L. Archer, and M. J. Ratain. "A Dosing/Cross-Development Study of the Multikinase Inhibitor Sorafenib in Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension." Clin Pharmacol Ther 87, no. 3 (2010): 303-10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).