1. Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease (CTEPD) with or without pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a disease caused by persistent obstruction of the pulmonary arteries by organised fibrotic thrombi and associated microvasculopathy. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is usually considered a complication of acute pulmonary embolism (PE), and it has been estimated that approximately 0.56-3% of patients with acute PE develop CTEPH [

1,

2]. This condition includes symptomatic patients with mismatched perfusion defects on pulmonary ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan and evidence of chronic, organised, fibrotic clots on computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA) after at least 3 months of therapeutic anticoagulation [

3]. The incidence of CTEPH is 3.1-6.0 per million and the prevalence is up to 25.8-38.4 per million [

4]. The number of people diagnosed with CTEPH is increasing due to a better understanding of the disease and more active screening [

3].

Pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) is the first-line treatment for patients with CTEPH and, when performed in experienced centres, is associated with in-hospital mortality of <5% as well as haemodynamic and functional improvement and long-term survival [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, in certain situations surgery cannot be performed, for example due to distal location of the disease (technically not feasible) and patient comorbidities (poor risk/benefit ratio) [

9]. As a result, approximately 40% of CTEPH patients are inoperable [

8]. In addition, up to 25% of operated patients have residual or recurrent PH [

10]. Such patients can be treated with PH-specific medical therapy, but current evidence of haemodynamic and symptomatic improvement lacks long-term data [

11,

12].

Consequently, balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) has recently emerged as a treatment option and is now recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) for patients who are technically inoperable or have residual PH after PE and distal obstructions amenable to BPA (class IB recommendation) [

3]. BPA is an interventional procedure that uses a specifically sized balloon to dilate organised thrombi and restore blood flow to the distal pulmonary arteries [

13]. Evidence shows that BPA improves pulmonary haemodynamics, 6-minute walk distance, functional class and quality of life by improving pulmonary circulation [

9,

14,

15,

16]. We aim to share our first experience on BPA procedures and to evaluate the efficacy of such therapy for inoperable CTEPH patients in a low volume PH referral centre at Vilnius University Hospital Santaros clinics.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population. The observational study was approved by the Vilnius Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 2020/1-1182-669 with amendments RL-PC-1). Only patients with inoperable CTEPH who signed an informed consent to participate in the study were enrolled. Patients were evaluated at the Vilnius Pulmonary Hypertension Referral Centre. The diagnosis of CTEPH was based on a detailed medical history, physical examination, chest radiography, chest computed tomography, transthoracic echocardiography, pulmonary ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy, right heart catheterisation (RHC) and angiographic demonstration of multiple stenoses and obstruction of the bilateral pulmonary arteries. CTEPH was diagnosed after at least 3 months of effective anticoagulation with (a) mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) ≥ 25 mmHg, (b) pulmonary artery wedge pressure ≤ 15 mmHg, and (c) elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) > 3 wood units, confirmed by right heart catheterisation according to current guidelines (37). The analysed cohort consisted of 26 consecutive patients who underwent BPA interventions at Vilnius University Hospital Santaros clinics (VUHSC) between November 2019 and December 2023. 12 patients with clinical and haemodynamic data at follow-up constituted the final cohort to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BPA in the setting of a single, low-volume centre.

Clinical evaluation. Periprocedural tests included measurements of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and transthoracic echocardiographic parameters. Right heart catheterisation (RHC) was performed to measure systolic (sPAP), diastolic (dPAP), mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) and cardiac output (CO). In addition, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in Wood units and cardiac index (CI) were calculated invasively.

Procedure. The procedures were performed by two specially trained interventional cardiologists at the centre with more than ten years' experience as interventional cardiologists, one in coronary artery disease and the other in structural heart disease.

Description of the BPA procedure. Ultrasound-guided cannulation of either the right or left femoral vein was used to reduce puncture site complications. Sequential contrast angiography of the right and left pulmonary arteries (PAs) was performed using either a 5 Fr or 6 Fr pigtail catheter to identify stenoses. The pigtail catheter was then exchanged for a guide catheter - either an RJ, LJ or multipurpose (MP) catheter, with the choice of 6Fr or 7Fr at the operator's discretion. The decision on which pulmonary artery branches to target for intervention was based on an analysis of the morphology of the PA branches and the location of the stenoses. The guiding catheter was selectively navigated into the involved branch and the stenosis was crossed with a 0.014" guidewire, with the use of a non-polymer "workhorse" wire recommended. A balloon catheter, chosen to be slightly smaller than the expected diameter of the vessel, was threaded over the wire and inflated at the site of the stenosis and held in place for 30-60 seconds. Initial dilatation was performed with a small diameter balloon of 2.0 to 2.5 mm.

To prevent reperfusion pulmonary oedema, severe lesions were treated sequentially in stages during multiple BPA sessions at a mean interval of 9.5 weeks. Typically, 4-6 stenoses were treated per session, with the specific lesions selected by the interventionalist based on their complexity. The stenoses were dilated by changing the balloon diameter - the diameter of the balloon was gradually increased to the nominal diameter of the vessel at each subsequent session. As recommended by previous studies, a radiation dose of 1000 mGy, an exposure time of 60 minutes and a contrast volume of 300 ml were not exceeded in a single session to minimise the risk of procedural complications.

A 12-hour post-procedure observation period was recommended, followed by discharge home if no complications were observed after 24 hours. This approach ensures patient safety while making efficient use of hospital resources.

On average, a patient underwent 4.2 BPA procedures before discontinuing treatment. The reasons for stopping BPA were: improvement in mean PAP, symptomatic improvement, technical difficulties or lack of patient compliance.

Statistical analysis. Data were analysed using repeated measures ANOVAs for 6 MWD, BNP, sPAP, mPAP, CO and PVR. Analyses were performed using JASP software (version 0.18.2) (JASP Team, 2024;

https://jasp-stats.org/). The within-subject factor was the time of measurement: before treatment, after treatment and follow-up. The Bonferroni correction was used as a post-hoc test to see the specific differences between the measurement times. The expectations according to the hypotheses were as follows: (1) The Bonferroni comparisons between before BPA and after BPA as well as before BPA and follow-up in terms of 6 MWD and CO scores will show a significant difference and positive relationship; (2) Bonferroni comparisons between before BPA and after BPA as well as before BPA and follow-up for BNP, sPAP, mPAP and PVR scores were expected to show a significant difference and negative relationship; (3) 6 MWD, BNP, sPAP, mPAP, PVR and CO scores are expected to see no significant diference between the time of after treatment and follow-up. Sphericity assumptions were checked before the main analysis. Mauchly's sphericity test was used to check for violations. The test did yield a significant effect that signified violation of the assumption of sphericity, hence, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. All following analyses have been interpreted using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction.

3. Results

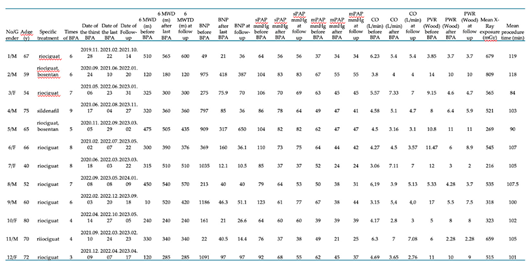

Baseline characteristics of the study population. Twenty-six patients were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 61.68 years (range, 40-80) and 16 (61.5%) were male. All patients were receiving anticoagulant therapy and 24 (92%) were receiving riociguat (21 patients) or another anti-PH therapy. Twenty-one patients were treated with monotherapy, 3 with a PH drug combination. Two patients received targeted PH treatment after a single BPA procedure and were not scheduled for further procedures due to lesions in very small vessels. The main characteristics of the study population are shown in

Table 1.

BPA Efficacy assessment. A total of 100 procedures were performed during the study period. 7 patients underwent only one procedure. No further procedures were planned for various reasons: mostly because the lesions were in very small vessels, at their distal end where BPA is technically impossible, or the vessels were very tortuous, kinked and there was no stenosis at maximum inspiration, or there were occlusions of small vessels where BPA could cause significant bleeding complications.

14 patients have completed the full course of treatment and 12 of these have had long-term follow-up since their last BPA procedure. For these 12 patients, the mean duration of treatment from the first to the last procedure was 355.5 days (119-624). The mean interval between treatments was 67 days (9.5 weeks) (28-364). The mean follow-up from the last treatment was 258.4 days (129-364 days) or 8.6 months. The total follow-up time from the first treatment to the last treatment was 613.9 days (324-867) or 1.7 years. The mean number of sessions for patients who completed treatment was 5.78 (range, 3-9). The longer-than-planned treatment duration may have been caused by the temporary suspension of treatments due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 5 patients, BPA treatment is still ongoing, with two or three sessions completed so far.

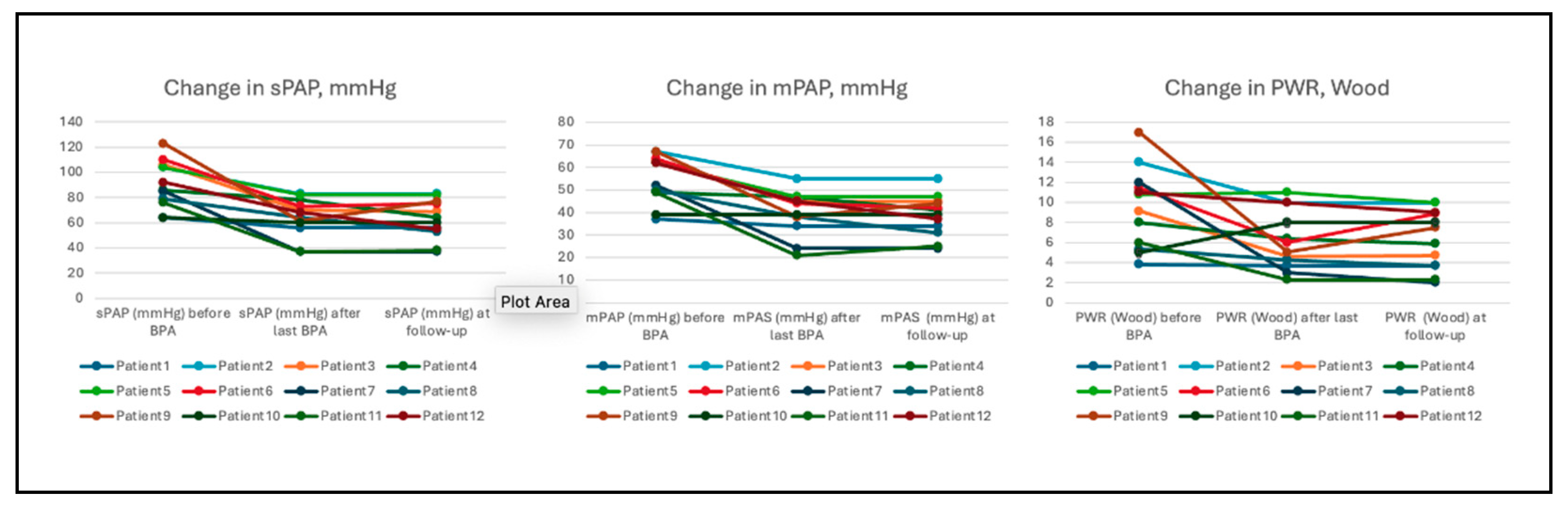

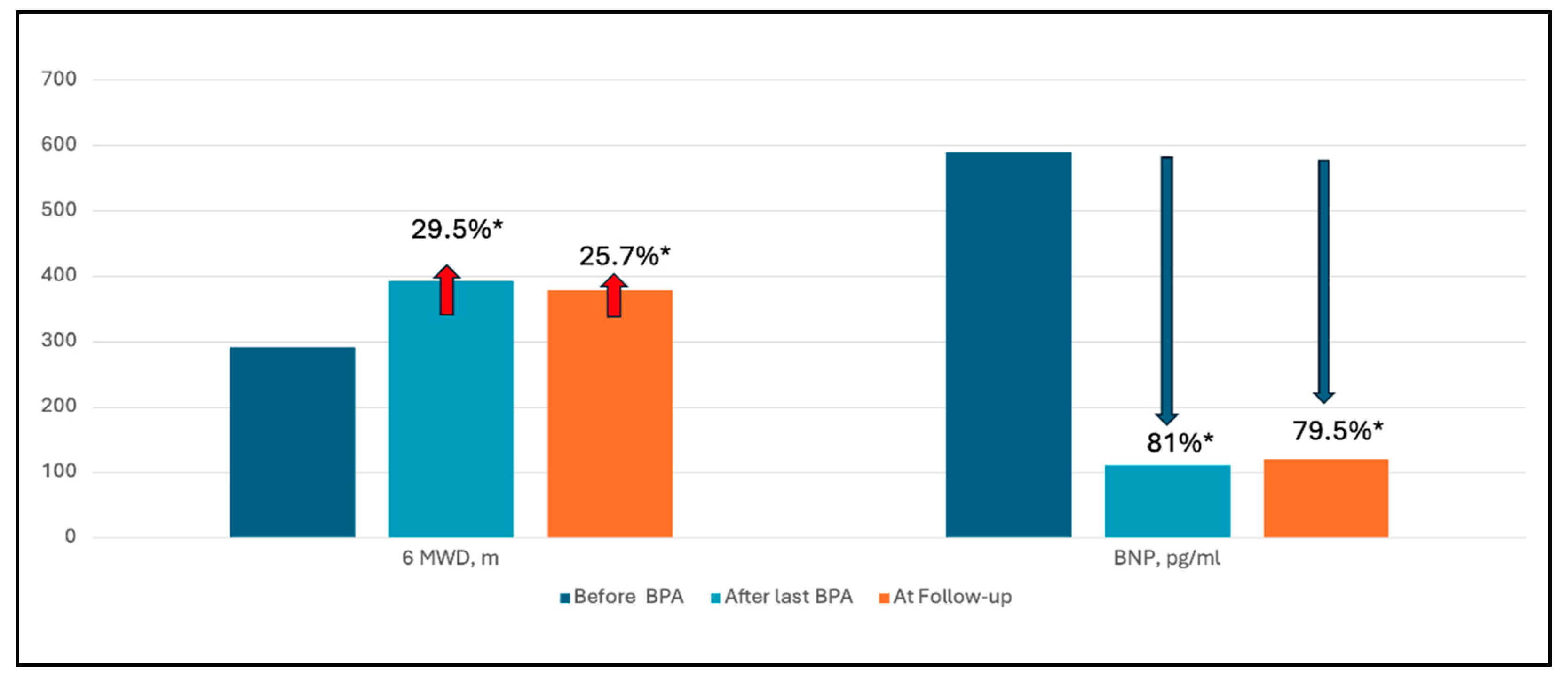

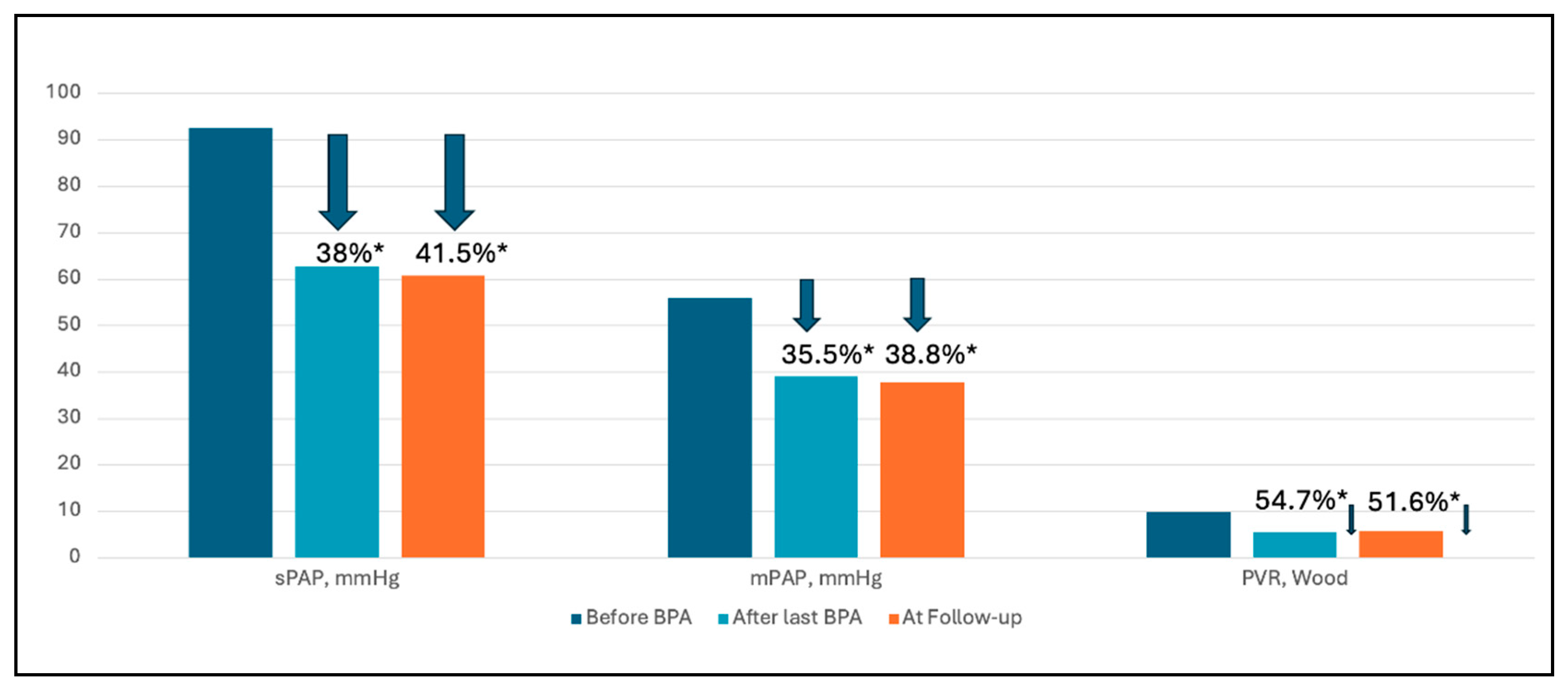

In 12 patients with a mean follow-up of 8.6 months, both 6MWD and BNP improved. The 6MWD increased from a mean of 292.9 to 394.5 metres (p=0.015) after the last BPA and to 379.6 metres at follow-up (p=0.043, compared to baseline); and BNP levels decreased from a mean of 590 to 111 pg/ml (p<0.001) after the last BPA and to 121 pg/ml at follow-up (p<0.001). In terms of haemodynamic parameters, there was a statistically significant improvement in sPAP, mPAP and PVR. Mean PAP decreased from a mean of 56±10 to 39±10 mmHg (p<0.001) after the last BPA and 37.8 9.6 at follow-up (p<0.001). PVR decreased from a mean of 9.7±4 to 5.5±2.6 Wood Units (p<0.001) after the last BPA and 5.7 2.9 at follow-up (p=0.001) (

Figure 1). Systolic pulmonary artery pressure decreased by 41.5%, mean pulmonary artery pressure by 38.8% and pulmonary vascular resistance by 51.6% at follow-up (

Figure 2). There was also a significant 79.5% reduction in brain natriuretic peptide levels and a 25.7% increase in 6-minute walk distance (

Figure 3). Full list of patients with demographic, clinical and hemodynamic parameters are presented in

Table A1, (

Appendix A). The efficacy of BPA on haemodynamic parameters, functional capacity and BNP levels is shown in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Changes in haemodynamic and clinical data before and after treatment with BPA.

Table 2.

Changes in haemodynamic and clinical data before and after treatment with BPA.

| N=12 |

Before BPA |

After last BPA |

P*

|

Follow-up |

P#

|

| 6 MWD, m |

|

394.5±130 |

0.015 |

379.6±138 |

0.043 |

| BNP, pg/ml |

590 ± 445 |

111.1±128 |

<0.001 |

121.2±195.2 |

<0.001 |

| sPAP, mmHg |

92.5 ± 18 |

62.7±15.6 |

<0.001 |

60.7±15.7 |

<0.001 |

| mPAP, mmHg |

56 ± 10 |

39±10 |

<0.001 |

37.8±9.6 |

<0.001 |

| CO (L/min) |

4.7 ± 1.2 |

5.3±1.3 |

0.749 |

5.0±1.55 |

1 |

| PVR, Wood units |

9.7 ± 4 |

5.5±2.6 |

<0.001 |

5.7±2.9 |

0.001 |

BPA Safety assessment. A total of 17 procedure-related complications occurred in 100 procedures (17% of all procedures). There were no serious or fatal complications. The most common complication was vessel dissection (10%), another was pulmonary vascular injury and contrast extravasation and leakage into the bronchi, followed by haemoptysis, which occurred in 3 procedures (3%). All of these events were mild and successfully managed with a balloon. One case of hyperperfusion pulmonary oedema was observed and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was successful and the procedure was stopped early. Complication rates decreased as the number of procedures performed increased. Complications and main procedural characteristics are listed in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Procedural characteristics and procedure-related complications.

Table 3.

Procedural characteristics and procedure-related complications.

| Procedures, n |

100 |

| Number of procedures range, mean per patient |

1-9, 4.2 |

| Mean duration of procedure, hours |

1:43±0:23 |

| Mean radiation exposure, mGy |

496±180 |

| Complications, n (%) |

17 (17 %) |

| • Contrast extravasation and leakage into bronchi, n (%) |

3 (3 %) |

| • Haemoptysis, n (%) |

3 (3 %) |

| • Vessel dissection, n (%) |

10 (10%) |

| • Hyperperfusion pulmonary oedema, n (%) |

1 (1 %) |

Table 2.

Changes in haemodynamic and clinical data before and after treatment with BPA.

Table 2.

Changes in haemodynamic and clinical data before and after treatment with BPA.

| N=12 |

Before BPA |

After last BPA |

P*

|

Follow-up |

P#

|

| 6 MWD, m |

|

394.5±130 |

0.015 |

379.6±138 |

0.043 |

| BNP, pg/ml |

590 ± 445 |

111.1±128 |

<0.001 |

121.2±195.2 |

<0.001 |

| sPAP, mmHg |

92.5±18 |

62.7±15.6 |

<0.001 |

60.7±15.7 |

<0.001 |

| mPAP, mmHg |

56±10 |

39±10 |

<0.001 |

37.8±9.6 |

<0.001 |

| CO (L/min) |

4.7±1.2 |

5.3±1.3 |

0.749 |

5.0±1.55 |

1 |

| PVR, Wood units |

9.7±4 |

5.5±2.6 |

<0.001 |

5.7±2.9 |

0.001 |

4. Discussion

In the present study, we report a series of patients with inoperable CTEPH treated with BPA from November 2019. The initial results from a single tertiary centre in a small country (with a population of less than 3 million) confirm that BPA is an effective treatment for patients with inoperable CTEPH. The study shows that BPA treatment statistically significantly reduced BNP levels, improved exercise capacity and haemodynamic parameters in patients with inoperable CTEPH. Procedure-related complications were observed in 17% of all sessions, the most common being vascular dissection (10% of all sessions). There were no serious or fatal complications.

Although not all patients achieved the optimal outcome (i.e. reduction of pulmonary artery pressure to normal), subjective clinical improvement was observed in the majority of patients treated, and one woman in her 40s was able to reduce her pulmonary artery pressure to near normal. Changes in their haemodynamic parameters, BNP and 6MWD are shown in

Table A2,

Appendix A.

Compared with other available studies (

Table A3,

Appendix A), the average improvement in pulmonary haemodynamics in our study was less pronounced than in the Japanese registry study, with a 52% and 58% decrease in PVR after final BPA, respectively [

17]. However, the improvement in PVR was more pronounced in our study than in the study by Olsson et al (51% and 26%, respectively) [

18]. The improvement in exercise capacity was more significant in our study than in the study by Brenot et al (26%, mean change +100 metres and 12%, mean change +51 metres, respectively) [

19]. However, the mean baseline 6MWD was lower in our study. The reduction in BNP levels was comparable to the Japanese results (80% and 82% reduction, respectively) [

17].

Despite its efficacy, BPA is an interventional procedure and is associated with serious complications. Peri-procedural complications include vascular injury due to wire perforation and lung injury [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Comparing the mean baseline 6MWD (292.9±151 and 318.1±122.1), BNP levels (590 ± 445 and 239.5±334.2) and mPAP (56±10 and 43.2±11.0) between our study population and the Japanese study population, it is clear that our study population had more severe disease prior to treatment initiation [

17]. Brenot et al. showed that higher baseline mPAP was associated with lung injury (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.039-1.130; p<0.001), as well as higher baseline PVR and poorer exercise capacity [

19]. Lung injury is characterised by lung opacities on chest radiograph or CT scan, with or without hypoxaemia, and may or may not be associated with haemoptysis [

21]. Lang et al. also state that patients with severely compromised haemodynamics (mPAP >40 mmHg and/or PVR >7 Wood Units) have an established risk of hyperperfusion pulmonary oedema (9). Nevertheless, the rate of complications related to lung injury was comparatively low, occurring in 1% of all sessions, compared with 17.8% complications in the Japanese registry and 9.1% in the French registry [

17,

19]. These differences may be due to the lower number of procedures in our study and the avoidance of complex lesion types such as tortuous lesions and chronic total occlusions. The rate of vessel injury in our study (3% of all procedures) can be compared with the results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies by Kennedy et al, which showed a 5% rate of vessel injury [

23].

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty versus medical therapy. Patients with inoperable or recurrent CTEPH can be treated with riociguat or PAH-specific drugs. The ESC/ERS recommends the use of riociguat in symptomatic patients with inoperable CTEPH or persistent/recurrent PH after PEA (class I B recommendation) (3). Other medical therapies may also be considered, but there is less evidence on their safety and efficacy in patients with CTEPH. The results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 observational studies including 1454 patients by Wang et al. comparing BPA and riociguat in patients with inoperable CTEPH showed a greater improvement in pulmonary haemodynamics, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and 6MWD in patients treated with BPA compared to riociguat. Pulmonary vascular resistance was reduced with BPA by a mean difference of -1.3 Wood units (95% CI -1.57 to -1.08, P=.000) versus -0.7 Wood units (95% CI -0.79 to -0.50, P=.000) in the riociguat group. However, the increase in cardiac output (CO) was greater in the riociguat group and there was no significant difference in cardiac index (CI) between groups (29). RACE, a French multicentre randomised controlled trial, has recently published data from CTEPH patients randomised to BPA or riociguat. At week 26, mean pulmonary artery resistance decreased to 39.9% (95% CI 36.2-44.0) of baseline in the BPA group and 66.7% (95% CI 60.5-73.5) of baseline in the riociguat group (30). However, the rate of complications was higher with BPA. In the ancillary follow-up study, eligible patients on first-line BPA received add-on riociguat and patients on first-line riociguat received add-on BPA. At week 52, a similar reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance was observed in patients treated with first-line riociguat or first-line BPA (ratio of geometric means 0.91, 95% CI 0.79-1.04) (30). A Japanese multicentre randomised controlled trial (MR BPA) compared BPA with riociguat. At 12 months, mean pulmonary arterial pressure had improved by -16.3 (SE 1.6) mmHg in the BPA group and -7.0 (1.5) mmHg in the riociguat group (group difference -9.3 mmHg, 95% CI -12.7 to -5.9, p<0.0001) (31). However, more complications were also observed in the BPA group.

In fact, medical therapy may add value to BPA therapy while treating different pathogenetic mechanisms of the disease. PAH-specific drugs target distal and inaccessible pulmonary vasculopathy and remodelling, and BPA restores distal pulmonary flow at subsegmental levels (26). Wiedenroth et al investigated the effects of sequential treatment with riociguat and BPA. The results showed that riociguat improved haemodynamics and BPA led to further improvements (32). The majority of patients in the study were also receiving medical therapy, which may have confounded the results.

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty versus pulmonary endarterectomy. Although some patients are only eligible for PEA and others for BPA, both techniques can treat subsegmental and segmental disease (1). However, evidence comparing the two techniques is limited. Zhang et al. compared the safety and efficacy of BPA and PEA in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 54 studies and found that BPA may have a higher perioperative and 3-year survival rate, fewer types of complications and a greater improvement in exercise capacity compared to PEA. However, the improvement in haemodynamic parameters was more pronounced in the PEA group compared with the BPA group (at <1 month, 1-6 months and >12 months follow-up) (33). There are no RCTs comparing the two techniques, but Ravnestad et al. compared the two techniques in a single-centre observational cohort study of 82 patients. Both PEA and BPA significantly reduced mPAP and pulmonary vascular resistance, with significantly lower reductions for both parameters in the former group. However, there was no significant difference in exercise capacity between the groups (34). The results of another retrospective cohort study showed that the efficacy and safety of BPA in non-operable cases was similar to that of PEA in operable cases (35). However, a true comparison can only be made with large, multi-centre, controlled clinical trials. Long-term survival outcomes after PEA (averaging 90% at 3 years) are excellent (36), whereas long-term outcomes after BPA are lacking. However, results from a retrospective single-centre study from Japan show that long-term favourable outcomes after BPA can be expected, as haemodynamic data on mPAP and PVR were maintained long term (>3.5 years) (28). Post-operative PH is observed in approximately one quarter of patients undergoing PEA (10). While there is limited published experience with BPA in the post-PEA setting, data from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 studies suggest that improvements in clinical and haemodynamic parameters are possible with BPA in appropriately selected patients (23). This finding is consistent with recent guidelines and the stated recommendation of BPA treatment for residual PH after PEA (3). Therefore, future management of CTEPH may consist of both strategies and specific medical therapy, combined or sequential, adapted to the characteristics of the individual patient.

Study limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, this was a single-centre study with a small sample size and a relatively short follow-up period. Therefore, long-term results on the efficacy of BPA are lacking. Secondly, almost all study participants received PH-specific medication and there was no control group. Therefore, the effect of medication on post-procedure outcomes cannot be excluded. Thirdly, complete follow-up records were not available in all cases. Therefore, the analyses may have been confounded by missing variables. Finally, neither investigators nor patients were blinded to treatment.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study represents the first experience of treating unresectable CTPH using the BPA procedure in a single tertiary centre with a limited patient cohort. The BPA procedure was safe and effective in the setting of a low-volume centre. Further prospective multicentre studies are needed to establish the efficacy of BPA in addition to specific medical treatment and to assess the long-term efficacy of the procedure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.I..; methodology, T.I. and S.C.; statistical analysis, K.I..; formal analysis, T.I., S.G.; investigation, T.I.; resources, T.I..; data curation, T.I.; writing—original draft preparation, T.I. and A.D..; writing—review and editing, S.G., L.G., E.G., S.C.; visualization, T.I..; supervision, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Vilnius Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 2020/1-1182-669 with amendments RL-PC-1).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

data are available in Vilnius University hospital Santaros clinics data base.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full list of patients with demographic, clinical and hemodynamic parameters.

Table A1.

Full list of patients with demographic, clinical and hemodynamic parameters.

Table A2.

The variations of one patient hemodynamic parameters, BNP and 6 MWD during treatment period and at follow up.

Table A2.

The variations of one patient hemodynamic parameters, BNP and 6 MWD during treatment period and at follow up.

| Visit |

I BPA |

VIII BPA |

Follow-up (11 month after last BPA) |

| Date |

2020.06.18 |

2022.04.21 |

2023.03.23 |

| BNP, pg/ml |

1035.8 |

12.1 |

10.5 |

| PAP (s/d/m), mmHg |

85/30/52 |

37/14/24 |

37/14/24 |

| PWP, mmHg |

8 |

8 |

10 |

| CO (L/min) |

3.06 |

4.18 |

7.11 |

| PVR, Wood units |

12 |

3.1 |

2 |

| 6MWD, meters |

315 |

510 |

510 |

For a 40-year-old woman receiving PH-specific treatment with riociguat, the BPA procedures started on 8 June 2020. During the entire treatment period, 8 sessions of BPA treatments were performed, with a treatment duration of 22 months. Follow-up was performed 11 months after the last BPA (i.e. 23 March 2023). |

Table A3.

Summary of studies which analysed patients with inoperable CTEPH undergoing BPA.

Table A3.

Summary of studies which analysed patients with inoperable CTEPH undergoing BPA.

| |

Our study |

Ogawa et al. [17] (Japanese) |

Brenot et al. [19] (French) |

Darocha et al. [24] (Polish) |

Olsson et al. [18] (German) |

van Thor et al. [25] Netherlands |

Hoole et al [26] (UK) |

Atas et al. [27] (Turkey) |

Centre/

Centres, n |

Single centre N=12 |

7 centers in Japan N=308 |

Single centre

N=184 |

8 centres in Poland N=156 |

2 centres in Germany

N=56 |

2 centres in Netherlands N=38 |

Single centre N=30 |

Single centre N=26 |

| Cohort |

Inoperable CTEPH |

Inoperable CTEPH 76%

Post PEA 4.5%

Refusal of PEA 13.6%

Unfavorable risk/benefit ratio 5.8% |

Inoperable CTEPH 81%

Post PEA 8%

Refusal of PEA 11%

|

Inoperable CTEPH 54.3%

Post PEA 12.7%

Refusal of PEA 11%

Unfavorable risk/benefit ratio 22%

|

Inoperable CTEPH 87%

Post PEA 13%

Refusal of PEA 11%

|

Inoperable CTEPH 69%

Refusal of PEA 13%

Unfavorable risk/benefit ratio 18%

|

Inoperable CTEPH |

Inoperable CTEPH 57.6%

Post PEA 42.4%

|

| Mean number of sessions per patient |

4.2 (1-9) |

4 (1-24) |

5.2±2.4

and

5.7±2.1 |

4.5 (2-7) |

5 (3-8) |

4.5±1.3

|

3 (1-6) |

No data |

| Mean time from the first to final procedure |

355.5 (119-624) days

|

366.6±394.1 days |

6.1 (4.5–7.5) months from first BPA to re-evaluation |

7.7 (3.4-13.9) month |

7.8 month |

No data

|

2 (1-5) month |

No data |

| Follow-up time interval since last procedure |

258.4 (129 – 364) days |

425±280.9 days |

3-6 month |

5.9 (3.0-8.0) month |

6 month |

6 month |

3 month |

3 month |

| Patents with PH therapy, percentage |

88% |

72.1% |

62% |

69.4% |

93% |

82% |

93.3% |

80% |

| 6MWD before BPA, meters |

278 ±149 |

318.1±122.1 |

383±137 |

341±129 |

358±108 |

374 ± 124 |

366±107 |

315±129 |

| 6MWD Follow-up, meters |

378 ±127 |

401.3±104.8 |

434±119 |

423±136 |

391±108 |

422 ± 125 |

440±94 |

411±140 |

| BNP before, BPA pg/ml |

624 ±450 |

239.5±334.2 |

No data |

NT pro-BNP

2275 (385-2675)

628 (85-533) |

No data |

NT pro-BNP

195 (96-18120

154 (71-387)

|

NT pro-BNP 442 (168-1607)

202 (105-447)

|

NT pro-BNP

456

189 |

| BNP follow-up, pg/ml |

120 ±122 |

43.3±76.4 |

| mPAP before BPA, mmHg |

55 ±10 |

43.2±11.0 |

44.3±9.8 |

45.1±10.7 |

40±12 |

39.5 ± 11.6 |

44.7±11.0 |

47.5±13.4 |

| mPAP Follow-up, mmHg |

40 ±9 |

24.3±6.4 |

33.8±9.8 |

30.1±10.2 |

33±11 |

30.6 ± 8.2 |

34.4±8.3 |

38±10.9 |

| PVR before BPA, dyn/s/cm−5 |

784 ±312 |

853.7±450.7 |

607±218 |

642±341 |

591±286 |

488 ± 376 |

663±281 |

744±376 |

| PVR follow-up, dyn/s/cm−5 |

520 ±232 |

359.5±222.6 |

371±188 |

324±183 |

440±279 |

264 ± 160 |

436±196 |

464±224 |

References

- Delcroix, M.; Torbicki, A.; Gopalan, D.; Sitbon, O.; Klok, F.A.; Lang, I.; et al. ERS statement on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2021, 57, 2002828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ende-Verhaar, Y.M.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Vonk Noordegraaf, A.; Delcroix, M.; Pruszczyk, P.; Mairuhu, A.T.A.; et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism: A contemporary view of the published literature. Eur Respir J. 2017, 49, 1601792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Endorsed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) and the European Reference Network on rare respiratory diseases (ERN-LUNG). European Heart Journal. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leber, L.; Beaudet, A.; Muller, A. Epidemiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Identification of the most accurate estimates from a systematic literature review. Pulm Circ. 2021, 11, 2045894020977300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D. Pulmonary endarterectomy: The potentially curative treatment for patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. European Respiratory Review. 2015, 24, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.; Madani, M.; Fadel, E.; D’Armini, A.M.; Mayer, E. Pulmonary endarterectomy in the management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2017, 26, 160111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.; Jenkins, D.; Lindner, J.; D’Armini, A.; Kloek, J.; Meyns, B.; et al. Surgical management and outcome of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Results from an international prospective registry. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011, 141, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, J.E.; Su, L.; Kiely, D.G.; Page, K.; Toshner, M.; Swietlik, E.; et al. Dynamic Risk Stratification of Patient Long-Term Outcome After Pulmonary Endarterectomy: Results From the United Kingdom National Cohort. Circulation. 2016, 133, 1761–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, I.; Meyer, B.C.; Ogo, T.; Matsubara, H.; Kurzyna, M.; Ghofrani, H.A.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2017, 26, 160119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.C.; Jansa, P.; Huang, W.C.; Nižnanský, M.; Omara, M.; Lindner, J. Residual pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary endarterectomy: A meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018, 156, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, H.A.; Simonneau, G.; D’Armini, A.M.; Fedullo, P.; Howard, L.S.; Jaïs, X.; et al. Macitentan for the treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (MERIT-1): Results from the multicentre, phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017, 5, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; D’Armini, A.M.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Grimminger, F.; Jansa, P.; Kim, N.H.; et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in patients treated with riociguat for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Data from the CHEST-2 open-label, randomised, long-term extension trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016, 4, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, N. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2020, 35, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darocha, S.; Pietura, R.; Pietrasik, A.; Norwa, J.; Dobosiewicz, A.; Piłka, M.; et al. Improvement in Quality of Life and Hemodynamics in Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension Treated With Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty. Circ J. 2017, 81, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogo, T. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015, 21, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoppellaro, G.; Badawy, M.R.; Squizzato, A.; Denas, G.; Tarantini, G.; Pengo, V. Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty in Patients With Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ J. 2019, 83, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, A.; Satoh, T.; Fukuda, T.; Sugimura, K.; Fukumoto, Y.; Emoto, N.; et al. Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty for Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension: Results of a Multicenter Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017, 10, e004029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, K.M.; Wiedenroth, C.B.; Kamp, J.C.; Breithecker, A.; Fuge, J.; Krombach, G.A.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: The initial German experience. Eur Respir J. 2017, 49, 1602409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenot, P.; Jaïs, X.; Taniguchi, Y.; Garcia Alonso, C.; Gerardin, B.; Mussot, S.; et al. French experience of balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019, 53, 1802095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejiri, K.; Ogawa, A.; Fujii, S.; Ito, H.; Matsubara, H. Vascular Injury Is a Major Cause of Lung Injury After Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty in Patients With Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018, 11, e005884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Delcroix, M.; Jais, X.; Madani, M.M.; Matsubara, H.; Mayer, E.; et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019, 53, 1801915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawahara, H.; Ogawa, A.; Mizoguchi, H.; Yagi, H.; Ikemiyagi, H.; Matsubara, H. Vessel Stretching Is a Cause of Lumen Enlargement Immediately After Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty: Intravascular Ultrasound Analysis in Patients With Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018, 11, e006010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.K.; Kennedy, S.A.; Tan, K.T.; de Perrot, M.; Bassett, P.; McInnis, M.C.; et al. Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty for Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2023, 46, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darocha, S.; Roik, M.; Kopeć, G.; Araszkiewicz, A.; Furdal, M.; Lewandowski, M.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A multicentre registry. EuroIntervention. 2022, 17, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Thor, M.C.J.; Lely, R.J.; Braams, N.J.; ten Klooster, L.; Beijk, M.A.M.; Heijmen, R.H.; et al. Safety and efficacy of balloon pulmonary angioplasty in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in the Netherlands. Neth Heart J. 2020, 28, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoole, S.P.; Coghlan, J.G.; Cannon, J.E.; Taboada, D.; Toshner, M.; Sheares, K.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: The UK experience. Open Heart. 2020, 7, e001144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atas, H.; Mutlu, B.; Akaslan, D.; Kocakaya, D.; Kanar, B.; Inanc, N.; et al. Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty in Patients With Inoperable or Recurrent/Residual Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension: A Single-Centre Initial Experience. Heart Lung Circ. 2022, 31, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inami, T.; Kataoka, M.; Yanagisawa, R.; Ishiguro, H.; Shimura, N.; Fukuda, K.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Percutaneous Transluminal Pulmonary Angioplasty for Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation. 2016, 134, 2030–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wen, L.; Song, Z.; Shi, W.; Wang, K.; Huang, W. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty vs riociguat in patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2019, 42, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaïs, X.; Brenot, P.; Bouvaist, H.; Jevnikar, M.; Canuet, M.; Chabanne, C.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty versus riociguat for the treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (RACE): A multicentre, phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial and ancillary follow-up study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, 10, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, T.; Matsubara, H.; Shinke, T.; Abe, K.; Kohsaka, S.; Hosokawa, K.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty versus riociguat in inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (MR BPA): An open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, 10, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenroth, C.B.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Adameit, M.S.D.; Breithecker, A.; Haas, M.; Kriechbaum, S.; et al. Sequential treatment with riociguat and balloon pulmonary angioplasty for patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2018, 8, 2045894018783996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.; Yan, P.; He, T.; Liu, B.; Wu, S.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty vs. pulmonary endarterectomy in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2021, 26, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravnestad, H.; Andersen, R.; Birkeland, S.; Svalebjørg, M.; Lingaas, P.S.; Gude, E.; et al. Pulmonary endarterectomy and balloon pulmonary angioplasty in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Comparison of changes in hemodynamics and functional capacity. Pulm Circ. 2023, 13, e12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Miyagawa, K.; Nakayama, K.; Kinutani, H.; Shinke, T.; Okada, K.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty: An additional treatment option to improve the prognosis of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. EuroIntervention. 2014, 10, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcroix, M.; Lang, I.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; Jansa, P.; D’Armini, A.M.; Snijder, R.; et al. Long-Term Outcome of Patients With Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension: Results From an International Prospective Registry. Circulation. 2016, 133, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiery, J.L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Vonk Noordegraaf Beghetti, M.; Ghofrani, A.; Gomez Sanchez Hansmann, G.; Klepetko, W.; Lancellotti, P.; Matucci, M.; McDonagh, T.; Pierard, L.A.; Trindade, P.T.; Zompatori, M.; Hoeper, M. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J. 2015, 46, 903–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).