1. Introduction

The hippocampus, a brain structure central to memory encoding, exhibits numerous neurochemical, electrophysiological, neuropathophysiological, neuropathological, structural and cognitive changes in neurodegenerative diseases such as ischemia [

1,

2] and Alzheimer's disease [

3,

4,

5,

6]. All these changes underlie the memory loss typical of advanced age, ischemia and Alzheimer's disease [

4,

5,

6]. The hippocampus is a unidirectional network with a trisynaptic pathway that originates in the entorhinal cortex, connecting the dentate gyrus with pyramidal neurons of the CA3 and CA1 areas. Area CA3 receives signals from the dentate gyrus by mossy fibers and connects to the ipsilateral CA1 region through the Schaffer collateral pathway and further connects to the contralateral CA1 area by the commissural association pathway [

4]. Additionally, the CA1 area receives signals from the entorhinal cortex by the perforant pathway and connects to the subiculum. Areas CA1 and CA3 form a continuum in the hippocampus and have parallel inputs, but these areas have different output pathways and different network architectures [

4]. Therefore, these two regions play different roles and process different information [

4]. CA1 pyramidal neurons are important for mediating associations with temporal components and have the ability to maintain short-term memory, while CA3 neurons are involved in processes related to the rapid formation of spatial or contextual memory [

4]. The hippocampal CA3 and CA1 regions, despite being linked by Schaffer collaterals and forming a continuum, have been shown to respond differently to ischemic episodes [

2,

3,

7,

8].

In this article, we focus on changes in the CA3 area as one part of a specific hippocampal pathway. Studies have shown acute and chronic changes in the CA3 area of pyramidal neurons in animals surviving after ischemia for up to 2 years [

2], which were identical to changes in Alzheimer's disease [

4,

5,

6,

9]. Elevated extracellular glutamate levels have been demonstrated by microdialysis in this structure immediately after ischemia, indicating a disorder in the neuronal or astrocytic glutamate uptake system [

10,

11]. The increase in extracellular glutamate after ischemia led to the activation of glutamate receptors and neurotoxicity with a 74% decrease in basal calcium levels in this space [

10]. In addition, persistent dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier caused extravasation of blood elements such as T lymphocytes, platelets, amyloid, tau protein, immunoglobulins, complement, fibrinogen, pro-inflammatory factors and affected the production of free radicals [

4,

12]. Fibrinogen with pro-inflammatory pathway activating properties significantly activated astrocytes and microglia in the CA3 area after ischemia in experimental studies with survival up to 2 years [

4,

13]. Experimental studies have shown that neuroinflammatory processes are supported by the activity of astrocytes and microglia even up to 2 years after cerebral ischemia [

13]. Damage to the blood-brain barrier results in impaired communication between astrocytes and vessels, which in turn leads to changes in the cytoarchitecture of the blood-brain barrier, changes in regional homeostasis and energy deficiency, which in turn leads to an energy crisis [

4]. In case of increased energy demand after ischemia as it is in CA3 area of hippocampus, damage to the blood-brain barrier affects the functionality of energy-intensive neurons [

14]. In addition, immunohistochemical studies after experimental cerebral ischemia with survival up to 1 year showed accumulation of the C-terminal of the amyloid protein precursor and amyloid in the extracellular space around the brain vessels [

15].

Recent studies of the CA3 area of the hippocampus showed significant changes in gene expression associated with the death of pyramidal neurons after cerebral ischemia with post-ischemic survival of 2 to 30 days [

16]. Studies have shown that on day 2 after ischemia, the expression of the

caspase 3 gene was below the control value. However, it was significantly expressed over the next 7–30 days [

16]. In contrast,

BECN1 gene expression remained below the control value for 2-7 days and significantly increased on the thirtieth day after ischemia [

16]. On the other hand, expression of the

BNIP3 gene was reduced below control values throughout the follow-up period after ischemia [

16]. In addition, gene expression studies in the CA3 region with survival from 2 to 30 days after ischemia related to the processing of

amyloid protein precursor and

tau protein showed significant changes in expression, too [

17]. Two and 30 days after ischemia

, amyloid protein precursor gene expression was near control values, but 7 days after ischemia,

amyloid protein precursor gene expression was significant and maximal [

17]. Throughout the observation period, expression of the

α-secretase gene in this region was below control values [

17]. The expression of the

β-secretase gene was below the control values after 2 and 7 days after ischemia, while on the 30th day after ischemia it was definitely above the control values [

17]. On the other hand, the expression of the

presenilin 1 gene after 2 and 7 days was above the control values and fluctuated around the control values on the 30th day after ischemia [

17]. On the 2nd day after ischemia, the expression of the

presenilin 2 gene oscillated around the control values, on the 7th day it fell below the control values, and on the 30th day it significantly exceeded the control values [

17].

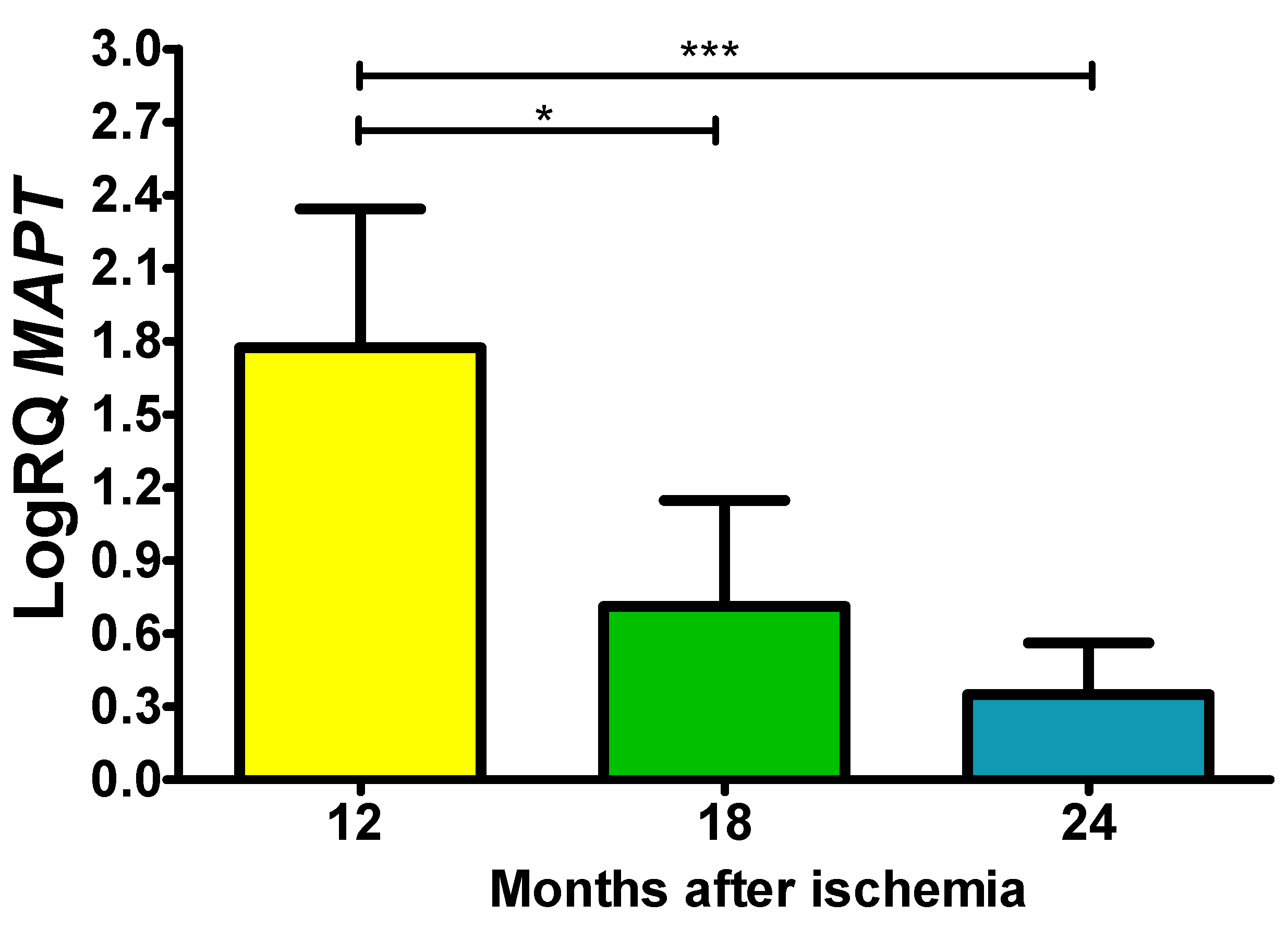

Tau protein gene expression was below the control value 2 days after ischemia, and there was a significant maximal increase in its expression after 7-30 days of survival [

17].

This work is part of an ongoing series of experimental studies focusing on the quantification of Alzheimer's disease-related genes using the RT-PCR protocol, such as α-secretase, β-secretase, presenilins 1 and 2, amyloid protein precursor and tau protein in the CA3 area of the hippocampus in rats that survived 12, 18 and 24 months after an ischemic episode.

2. Methods and materials

Female Wistar rats (n = 29, 2 months old, body weight 120-150 g) were subjected to 10-minute cerebral ischemia by cardiac arrest with survival after the ischemic episode at 12, 18 and 24 months [

18]. Rats were anesthetized with 2.0% isoflurane carried via O

2 [

17]. Anesthesia was discontinued shortly before the initiation of the cardiac arrest procedure. A hook made of an L-shaped steel needle was introduced into the chest through the right parasternal line and the third intercostal space. Next the hook was then gently moved towards the spine until slight resistance was felt. In the next stage, the hook was gently tilted 10-20° towards the tail. This meant that the hook in this position was under the bundle of heart vessels. The hook was then pulled to the sternum, which led compression and closure of the heart vessel bundle through the sternum. The end of the closing part of the hook in this position was located in the left parasternal line and in the second intercostal space. In order to prevent chest movements and ensure complete closure of the vessels, external pressure was applied to the sternum with the index and middle fingers, which resulted in complete hemostasis and subsequent cardiac arrest. After 3.5 min, the hook was removed from the chest and the rats remained in this state for next 6.5 min until resuscitation starts [

18]. Resuscitation consisted of external heart massage and artificial ventilation until cardiac function returned and breathing occurred. During this time, air was administered using a respirator through a polyethylene tube inserted into the trachea. External heart massage was performed with frequency of 150–240/min [

18].

Before and after ischemia, rats were housed in the animal house under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All studies were done within the day, and rats were handled in accordance with the NIH recommendations for the Care and Use of experimental animals and the Directive of the Council of the European Community. In addition, the IV Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments (31.12.2017, Nr 339/2017) approved all planned experimental procedures. After brain ischemia, animals survived for 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9) and 24 (n = 10) months. Sham-operated animals (n = 29) with survival times of 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9) and 24 months (n = 10) were subjected to the same experimental procedures without induction of complete brain ischemia and were served as appropriate controls. Every effort has been made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of rats used.

Immediately before collecting hippocampal samples from the CA3 area, brains were perfused through the left ventricle with cold 0.9% NaCl to flush blood from blood vessels. The brains were then removed from the skulls and transferred on ice-cooled Petri dishes. Samples with a volume of approximately 1 mm3 were collected from the CA3 area of the hippocampus after ischemia and from controls with a narrow scalpel from both sides and immediately placed in RNA later solution (Life Technologies, USA) [

17].

The method described by Chomczyński and Sacchi was used to isolate cellular RNA [

19]. Assessment of RNA quantity and quality was performed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) [

16,

17]. The isolated RNA was stored in 80% ethanol at – 20°C for further analyses [

16,

17]. In further studies, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA. cDNA synthesis was performed on Veriti Dx (Applied Biosystems, USA) using the manufacturer's SDS software [

16,

17]. The cDNA obtained was amplified by real-time gene expression analysis (qPCR) using the manufacturer's SDS software [

16,

17]. The tested gene was assessed in relation to the control gene (Rpl13a), and the relative amount (RQ) of the tested gene expression was presented using ΔCT, and the final value was presented as RQ = 2

−ΔΔCT [

17,

20]. The final result is presented after logarithmic conversion of the RQ values (LogRQ) [

17]. LogRQ = 0 means that the expression of the tested gene after ischemia and in the control did not change. LogRQ < 0 meant that the expression of the tested gene was decreased after ischemia, and LogRQ > 0 indicated increased gene expression after ischemia compared to the control.

Statistica v. 12 was used to statistically evaluate the data using the Kruskal-Wallis test with the “z” test. Data in graphs are means ± SD. P ≤ 0.05 means significant statistical changes in genes expression.

4. Discussion

In this work, we continue studies to investigate temporal changes in the expression of amyloid protein precursor processing and tau protein genes in an ischemic model of Alzheimer's disease with survival up to 2 years. Our data provide for the first time, changes of genes expression in: ADAM10 and BACE1, PSEN1 and PSEN2, APP and tau protein connected with Alzheimer's disease in the CA3 subfield following 10-min ischemic brain injury in animals with 1, 1.5 and 2 years of survival. First of all, we observed post-ischemic, non-amyloidogenic processing of amyloid protein precursor in the CA3 area. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that recirculation with brain ischemia activates neuronal changes and death in the CA3 region of the hippocampus in a tau protein-dependent manner, thus identifying a novel and important way of regulating the survival and/or death of ischemic neurons at very late stages after ischemia.

In the present study,

α-secretase gene expression was above control values at all observation times. However, the maximum expression of the

β-secretase gene was found after 12 months, but after 18 months it was below control values, and another increase in its expression was observed 2 years after ischemia.

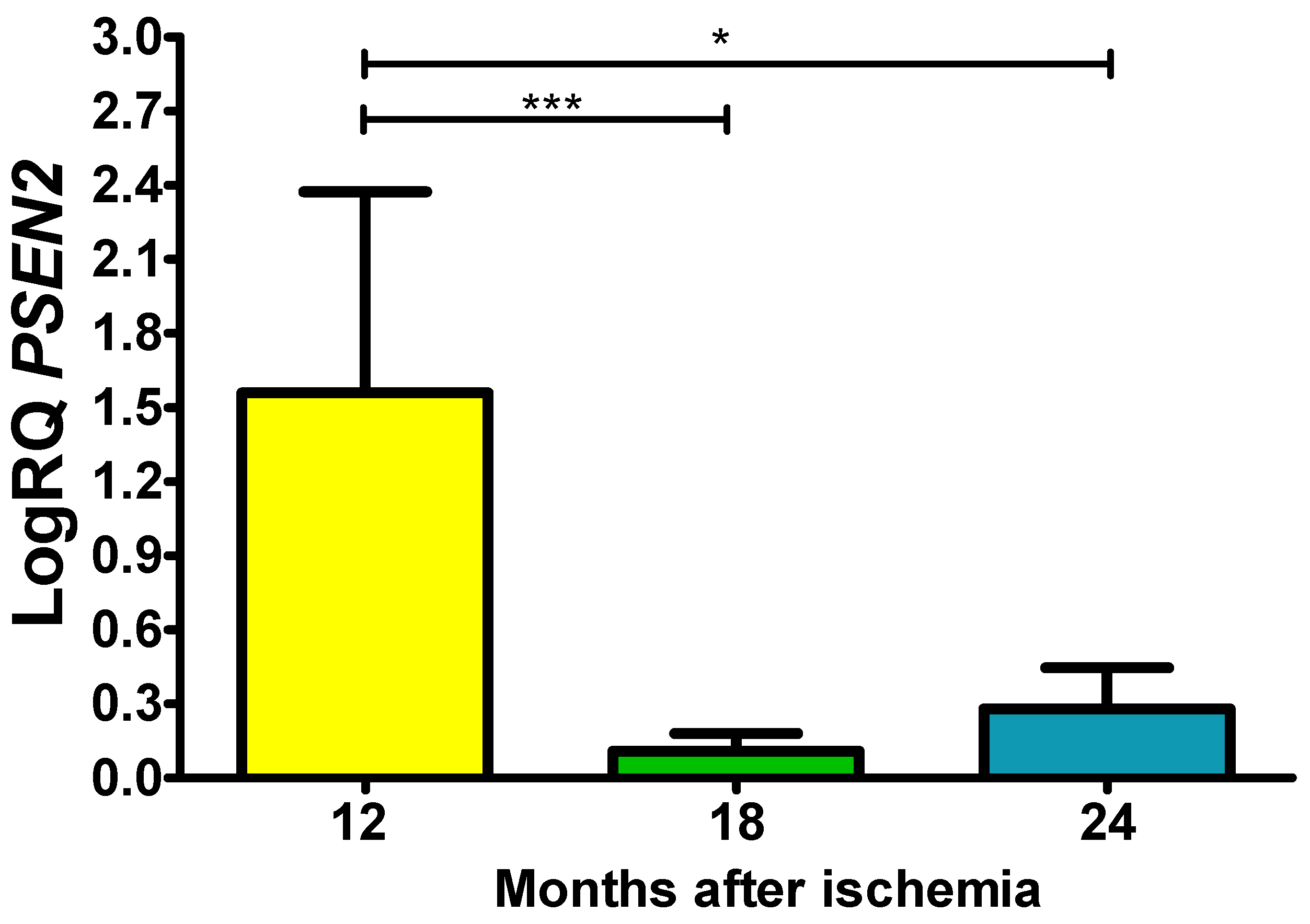

Presenilin 1 gene expression was significantly increased above control values through 2 years of recirculation.

Presenilin 2 gene expression showed the same trend as

presenilin 1 gene expression. Expression of the

amyloid protein precursor gene was consistently above control values after ischemia, with massive, significant overexpression at 12 and 18 months. Additionally,

tau protein gene expression was above control values throughout the postischemic follow-up period, with a maximum value after 1 year of recirculation. These data suggest non-amyloidogenic processing of amyloid protein precursor in the CA3 area of the hippocampus after long-term postischemia, and this observation contrasts markedly with amyloid production in this region during 30 days after ischemia [

17]. This phenomenon correlated with the appearance of acute and chronic neuronal changes in the CA3 area 1-2 years after ischemia [

2]. Overall, the response of hippocampal CA3 genes such as

amyloid protein precursor,

α-secretase, β-secretase,

presenilin 1 and

2 found in this study was different from the response of these genes in animals that survived after ischemia for up to 30 days [

17]. The current data may help, at least in part, to elucidate the molecular mechanism(s) for the slower and later occurrence of neuronal damage and death in the ischemic hippocampal area CA3 than in CA1 [

2].

Data indicate that 2 years after ischemia in our ischemic model of Alzheimer's disease, neurodegenerative damage is less severe in CA3 compared to CA1 [

2]. Progressive damage to the CA3 region is associated with the development of irreversible memory impairment [

21,

22]. Memory impairment is an early symptom of Alzheimer's disease, our data indicate that neuronal loss in the early stages in the CA3 region after ischemia contributes to memory impairment in an amyloid- and tau-dependent manner [

17], and in the late stages postischemia only through modification of tau protein [

23].

Another study found an increase in phosphorylated tau protein in the CA3 areas of the hippocampus after bilateral common carotid artery ligation [

24]. Excessively phosphorylated tau protein has a reduced ability to bind to microtubules, leading to microtubule depolymerization [

24]. Previous studies have shown that tau protein and glycogen synthase kinase-3 β (GSK-3β) are also promoters of secondary brain damage after ischemia [

25,

26] as in the case of Alzheimer's disease [

23]. Additionally, transgenic mice overexpressing GSK-3β exhibited tau protein hyperphosphorylation and neuronal death in the hippocampus [

27]. Consistent with the above reports, a significant increase in the level of tau protein phosphorylation (S404) and interaction with GSK-3β was observed after transient local cerebral ischemia [

28]. This suggests that tau protein S404 phosphorylation is an indicator of neuronal damage after ischemia [

28]. The increase in the level of total tau protein, which was assessed by brain microdialysis after ischemia, has to be also mentioned [

29], and this increase correlated with immunostaining [

30] and with our study of

tau protein gene expression. Numerous studies have shown that after ischemia, tau protein is hyperphosphorylated in neurons and is closely related to the development of their death through the mechanism of apoptosis [

31,

32]. Finally, hyperphosphorylation causes the formation of paired helical filaments after cerebral ischemia [

33], neurofibrillary tangles-like [

34], and neurofibrillary tangles [

35,

36] characteristic of Alzheimer's disease.

The degree of neuronal loss, especially in the hippocampus, is thought to influence the development and clinical manifestations of Alzheimer's disease [

37]. In Alzheimer's disease, the number of pyramidal neurons is reduced by as much as 45%, which correlates with the density of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques [

37]. In recent years, the tau protein and amyloid hypotheses have become the dominant hypotheses explaining the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease [

37]. However, a growing body of literature supports the view that ischemia plays a major role in driving tau protein and amyloid in the neuropathophysiology and neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease [

31,

38,

39,

40].

Thus, our model depicts the progressive, time- and region-specific development of CA3 neuropathology with genes

amyloid protein precursor processing and

tau protein and cognitive and behavioral symptoms, such as those found in patients with Alzheimer's disease [

2,

13,

15,

17,

21,

22]. However, further research is necessary to determine whether the damage and death of pyramidal neurons in the CA3 region are causative events or independent consequences of ischemia occurring in parallel and leading to the development of post-ischemic dementia. Finally, the rat model used in this study appears to be a useful experimental approach to determine the role of Alzheimer's disease-related genes. Through in-depth research into the common genetic mechanism associated with these two neurological entities, our findings may accelerate the current understanding of the neurobiology in Alzheimer's disease and cerebral ischemia, as well as lead future research on Alzheimer's disease or cerebral ischemia in new directions. Thus, characterization of an ischemic animal model may help us better understand the mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease and its neuropathogenesis. In our model, a life expectancy of up to 2 years provides a chronic scenario for the study and long-term monitoring of factors potentially involved in the modulation of Alzheimer's disease at the genomic, proteomic, neuropathological, structural, functional, and behavioral levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P. and S.J.C.; methodology, J.K.; A.B-K. and B.M.; software, A.B-K. and J.B.; validation, R.P., S.J.C. and J.K.; formal analysis, R.P.; investigation, R.P.; J.K.; A.B-K. and S.J.C.; resources, J.B. and B.M.; data curation, A.B-K.; R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.; writing—review and editing, R.P.; S.J.C. and B.M.; visualization, J.B.; B.M.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, S.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

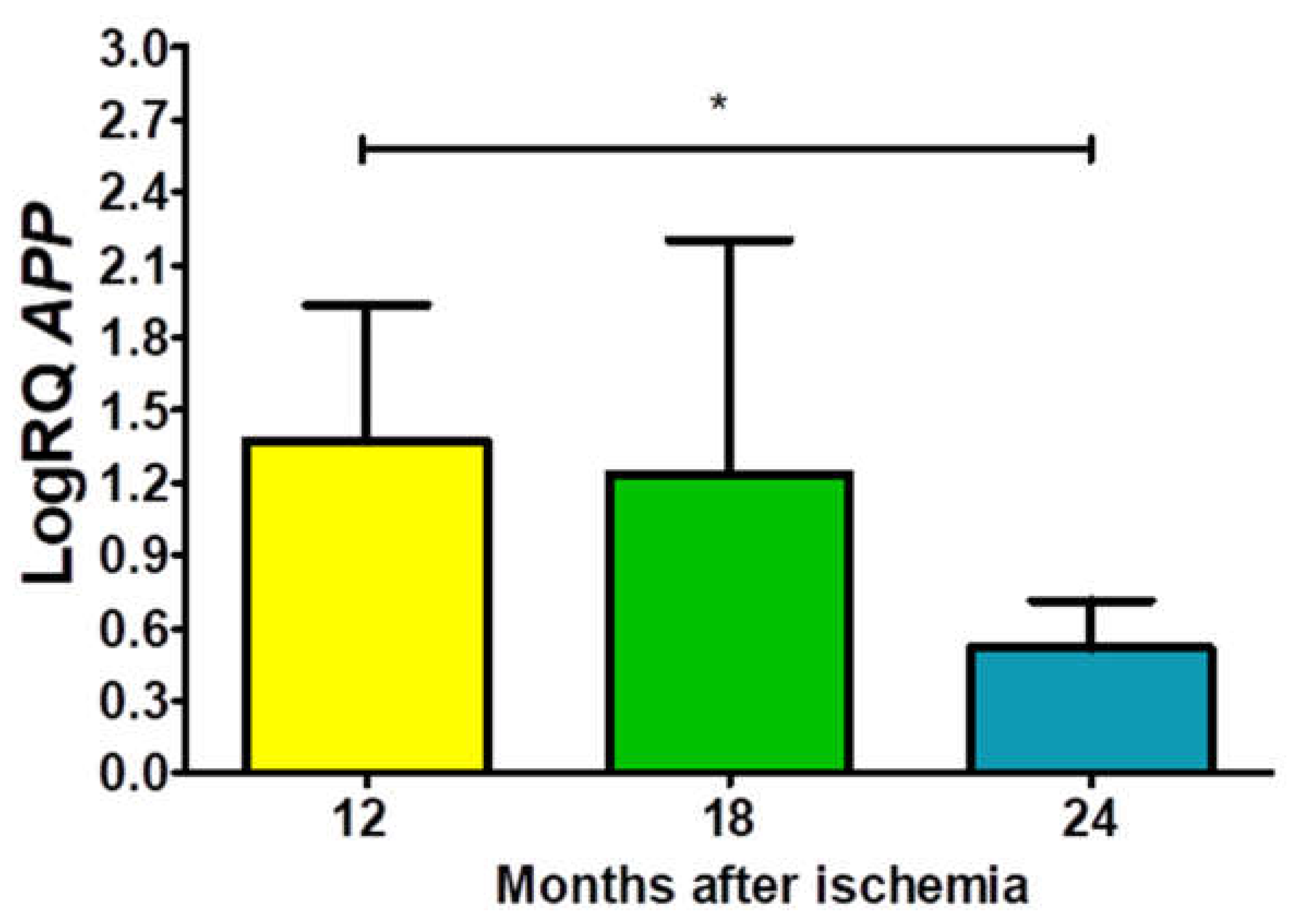

Figure 1.

The mean gene expression levels of amyloid protein precursor (APP) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 24 (z = 2.469, p = 0.04) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.04.

Figure 1.

The mean gene expression levels of amyloid protein precursor (APP) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 24 (z = 2.469, p = 0.04) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.04.

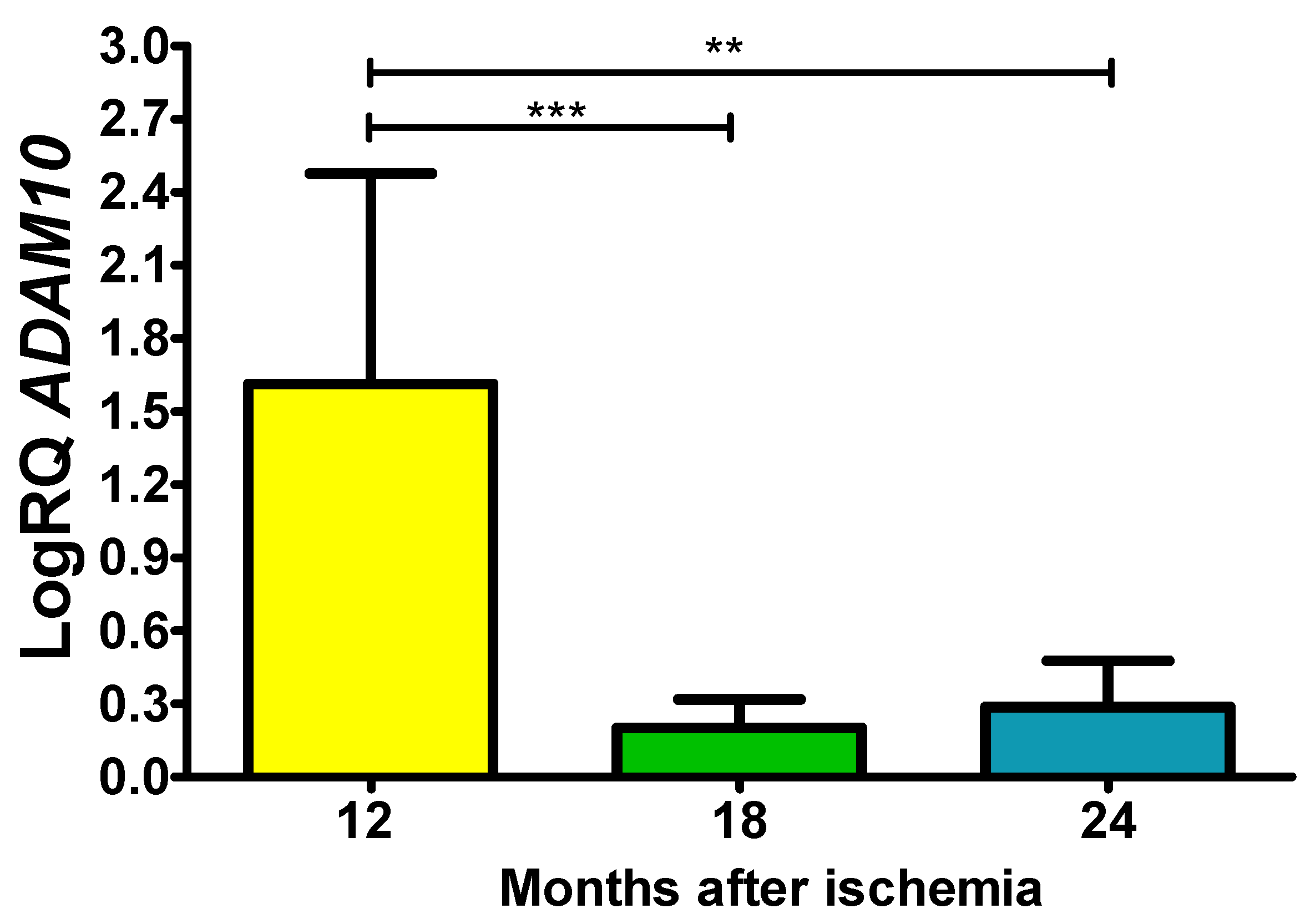

Figure 2.

The mean gene expression levels of α-secretase (ADAM10) in the hippocampus CA3 area 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.113, p = 0.0001) and 12 and 24 (z = 3.204, p = 0.01) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

Figure 2.

The mean gene expression levels of α-secretase (ADAM10) in the hippocampus CA3 area 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.113, p = 0.0001) and 12 and 24 (z = 3.204, p = 0.01) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

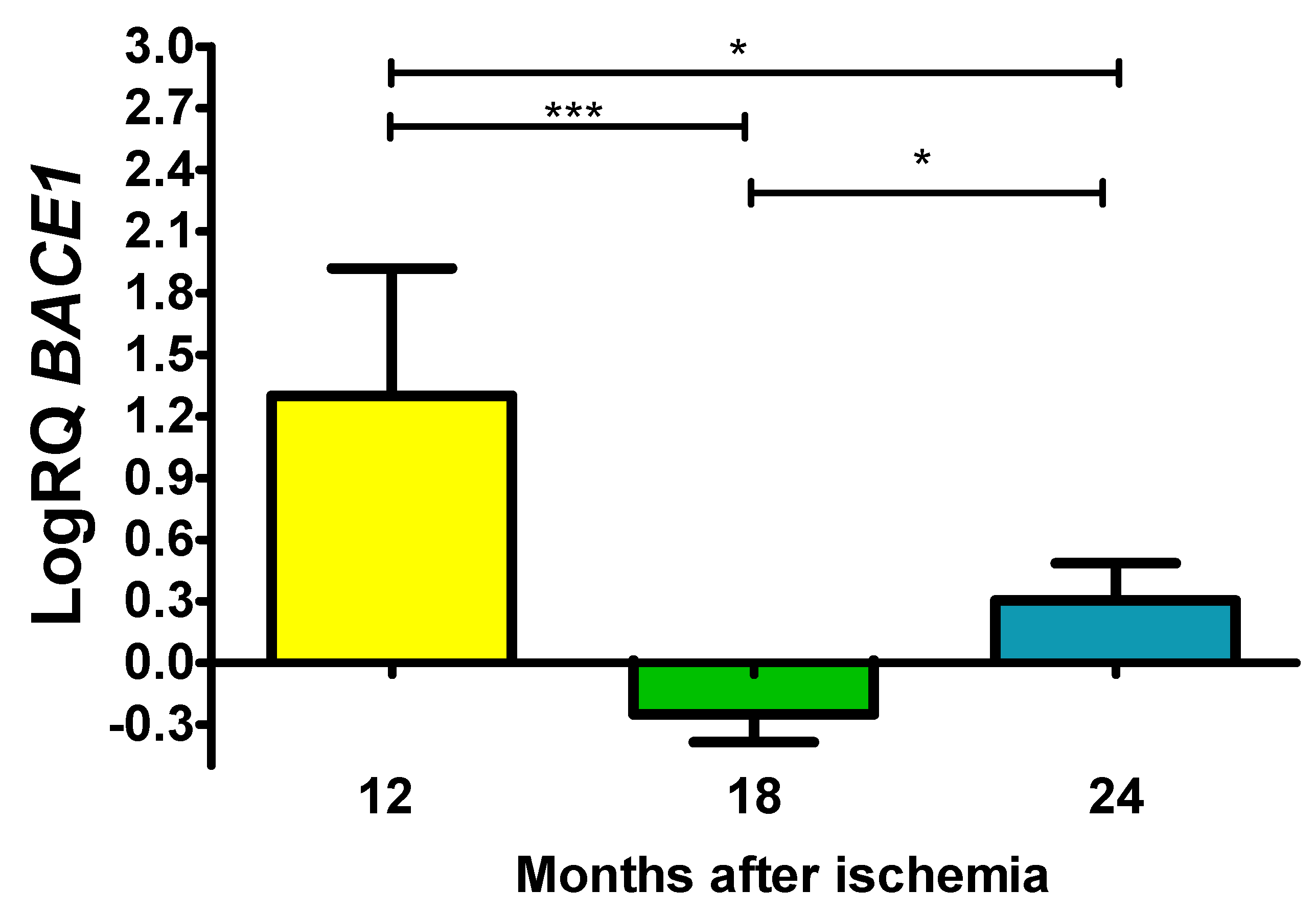

Figure 3.

The mean gene expression levels of β-secretase (BACE1) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.908, p = 0.00001) and 12 and 24 (z = 2.469, p = 0.04) and 18 and 24 (z = 2.505, p = 0.04) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.04, ***p≤0.00001.

Figure 3.

The mean gene expression levels of β-secretase (BACE1) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.908, p = 0.00001) and 12 and 24 (z = 2.469, p = 0.04) and 18 and 24 (z = 2.505, p = 0.04) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.04, ***p≤0.00001.

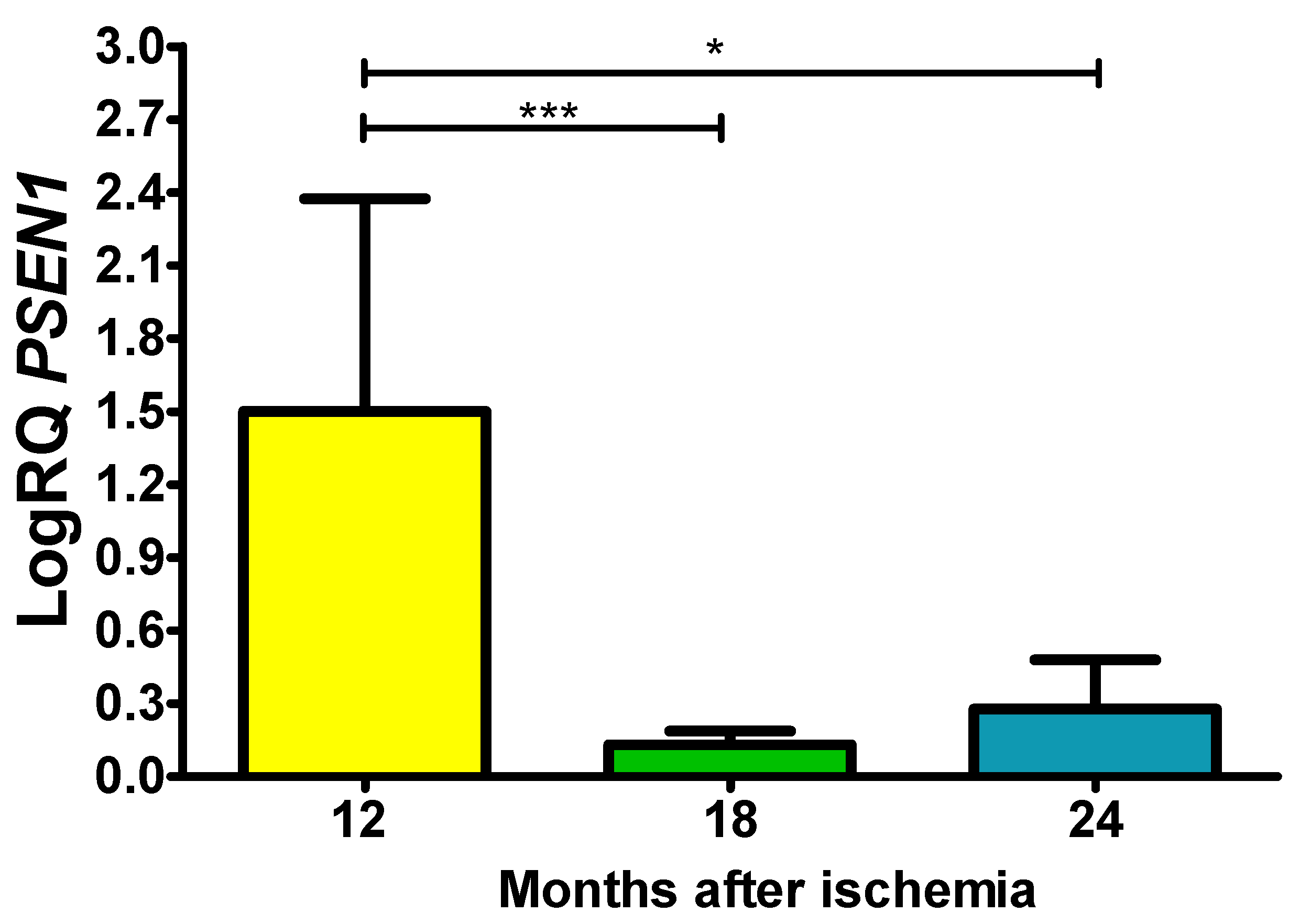

Figure 4.

The mean gene expression levels of presenilin 1 (PSEN1) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.042, p = 0.0001) and between 12 and 24 (z = 2.889, p = 0.01) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

Figure 4.

The mean gene expression levels of presenilin 1 (PSEN1) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.042, p = 0.0001) and between 12 and 24 (z = 2.889, p = 0.01) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

Figure 5.

The mean gene expression levels of presenilin 2 (PSEN2) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.482, p = 0.0001) and between 12 and 24 (z = 2.863, p = 0.01) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

Figure 5.

The mean gene expression levels of presenilin 2 (PSEN2) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 4.482, p = 0.0001) and between 12 and 24 (z = 2.863, p = 0.01) months after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

Figure 6.

The mean gene expression levels of tau protein (MAPT) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 2.823, p = 0.01) and between 12 and 24 months (z = 4.320, p = 0.0001) after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.01, ***p≤0.0001.

Figure 6.

The mean gene expression levels of tau protein (MAPT) in the hippocampus CA3 area in rats 12 (n = 10), 18 (n = 9), and 24 (n = 10) months after 10-min brain ischemia. Marked SD, standard deviation. Indicated statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression between 12 and 18 (z = 2.823, p = 0.01) and between 12 and 24 months (z = 4.320, p = 0.0001) after ischemia (Kruskal-Wallis test). *p ≤ 0.01, ***p≤0.0001.