Für einen Organismus muß die Welt voraussagbar sein,

sonst kann er in ihr nicht leben.1

Irinäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1998

The theory of life is a theory for the generation of information.

Manfred Eigen, 2013

1. Introduction

Life on Earth emerged by

self-organisation. Following Eibl-Eibesfeld (1998), the ability of prediction

is a necessary condition for life; no organisms are known without this ability.

Forms of “honorary life” (Dawkins 1996) such as human apparatuses that are part

of the human culture also belong to the realm of life (Donald 2008). If we

include those, there exists no prediction outside that realm, so that

prediction is also a sufficient condition for life. From this perspective, the

self-organisation of prediction is a process equivalent to the

self-organisation of life. In contrast to the various chemical and

environmental ingredients to the beginning of life, however, prediction may be

understood as a merely physical technique, based on causality and natural laws,

independent of any specific biological or biochemical details. According to

Eigen (1971, 1976, 1994, 2013, Eigen and Schuster 1977), life is a process of

generation and accumulation of information by means of repeated trial and

error.

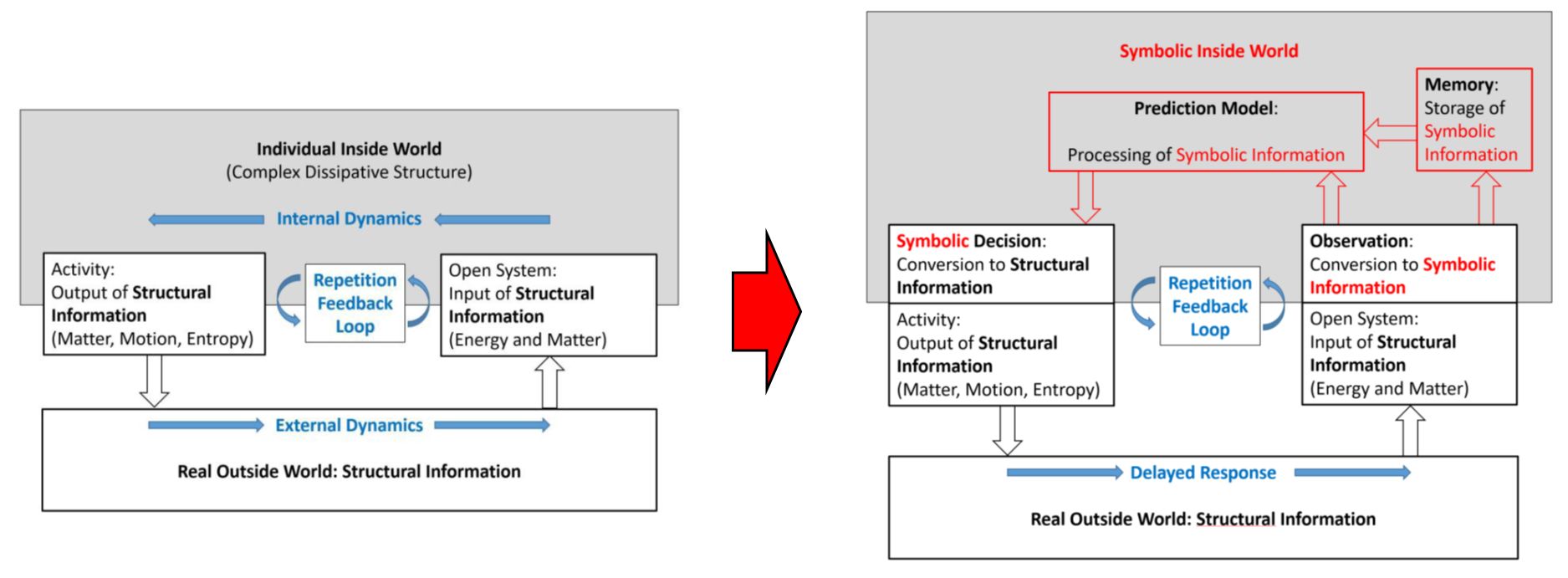

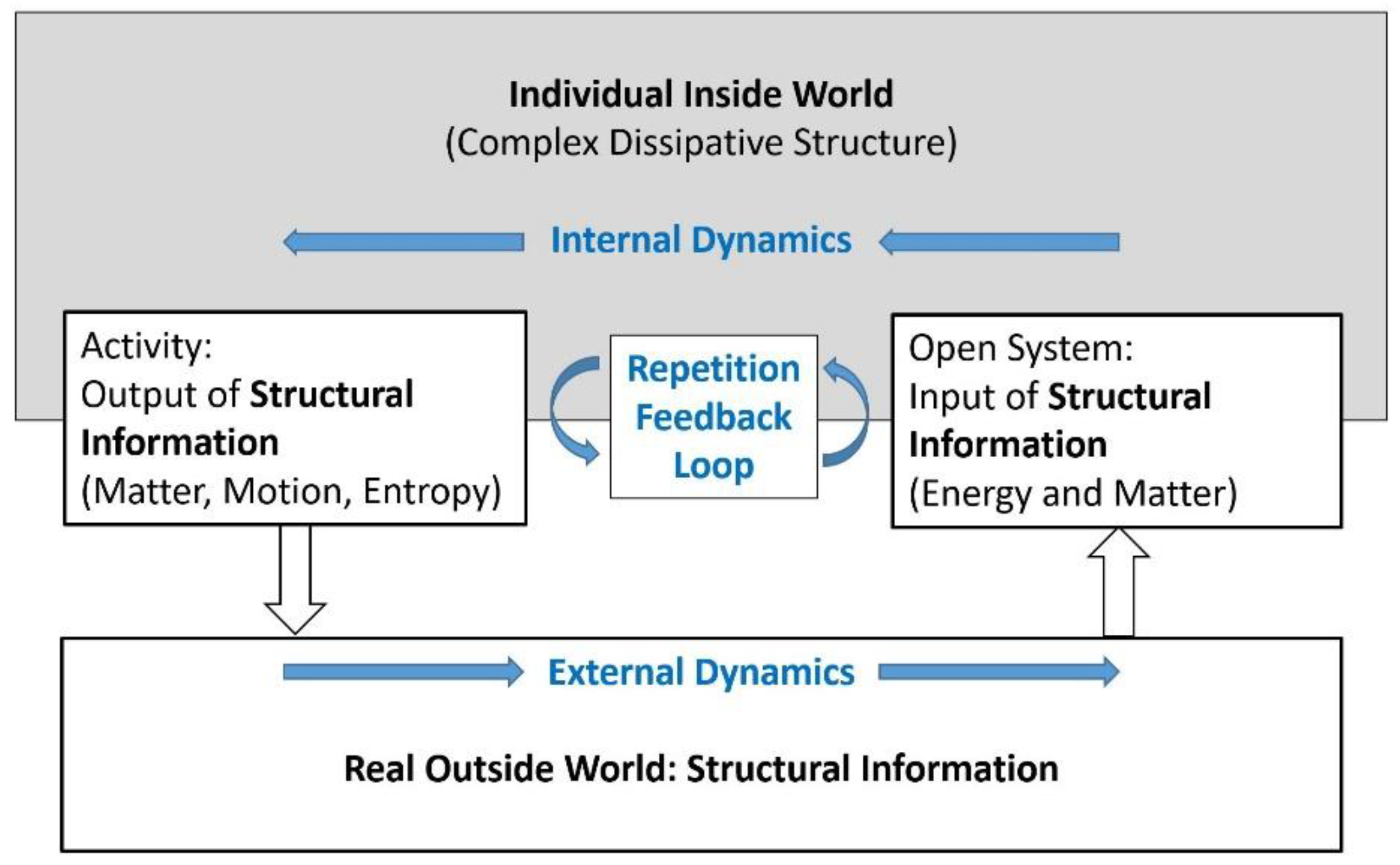

Fig. f1.1 shows schematically a simple conceptual model of a trial-and-error system

interacting with its outside world, representing this way also any arbitrary

organism from its perspective of prediction. “The ability to learn and form

memories allows animals to adapt their behavior based on previous experiences”

(Botton-Amiot et al. 2023).

Trial, in particular random trial,

is an elementary, precursory version of prediction. The self-organisation of

prediction may be understood as the transition from blind trial to sophisticated

prediction based on causal models. Conventional physical systems such as a heat

engine do not possess any prediction abilities.

Fig. f1.2 shows a conceptual

model of such an inanimate open physical system, possessing internal

non-equilibrium dissipative structures and performing related processes,

interacting across an interface with its environment.

A striking distinction between

Figure f1.1 and

Figure f1.2 is the one between

symbolic information and

structural

information (Ebeling and Feistel 1994, Feistel and Ebeling 2011, Feistel

2017a, 2023),

see Section 5 and

Section 6.

Entropy may serve as an example demonstrating the

difference. By the “negentropy principle of information” (Brillouin 2013: p.

153), entropy is often described as a quantitative measure for the amount of

information contained in a certain physical structure. Introduced empirically

by Clausius (1865, 1876) and statistically by Planck (1906, 1966), thermal

entropy is a measure of the amount of

structural information (or

physically bound information). Its value depends on the physical nature and on

the state of a given object; for example, the entropy of a mass of liquid water

is different from that of the same mass of ice, even at the same temperature

and pressure (Feistel and Wagner 2006). Entropy of Shannon and Weaver (1964),

by contrast, is a measure of the amount of

symbolic information (or

physically free information); it does not depend on the physical nature of the

particular information carriers, be those neural nerve pulses, electronic

computer bits or ink-printed letters (Brillouin 2013, Feistel 2017a, 2019).

“From the perspective of evolution

theory, the world of sign-likes appears as a stage of evolution that was

preceded by a world of not yet sign-likes“ (Nöth 2000: p. 135). “Semiosis is

the process in which the sign (and meaning) emerges. In other terms, semiosis

is interpretation” (Kull 2018: p. 455). The schematic transition process from

Fig. f1.2

to f1.1 is a

self-organised replacement of a structural process by a symbolic process. At

the transition point, which will be described here as a

ritualisation

transition, the two processes are actually identical. Such a transition has

occurred at the beginning of life, as will be considered in more detail in

Section 7

. A similar

transition has also happened in recent time in the technical world, such as the

transition from cybernetic systems using mechanical or electrical feedback

circuits and relays (Wiener 1948, Kämmerer 1974, 1977), functioning as in

Fig. f1.2

, to artificial

intelligence which is learning by the trial-and-error method of

Fig. f1.1

, and is much more

flexible by using of symbolic information.

Clearly, in the end, any symbolic

process is also some physical process, similar to the “naked” structural

process, but in the symbolic one the physical aspect is not the essential

contribution. If a task needs to be solved on a computer, this is performed

physically by certain mechanical or electronic switches or relays, but the kind

of (structural) hardware is not crucial for the task, while the (symbolic)

software implemented on the hardware is the significant aspect for the solution

of the problem. The arbitrariness of the particular hardware platform had been

formulated by Turing (1950) as the universality principle of digital

computers. With respect to symbolic information processing, this principle implies

the code symmetry (Feistel 1990, 2017a,b), or the semiotic arbitrariness

(Nöth 2000), or the principle of code plurality (Kull 2007), of

symbols in representing a certain meaning.

In this paper it will be assumed

that any symbolic information, in distinction to its structural counterpart,

has a purpose, and that this purpose consists in its influence on future

decisions and physical actions taken by the receiver of the symbolic

information. Purpose is something meaningless in the lifeless world. Symbolic

information in its own right is futile; it gets its relevance only after

subsequent conversion to structural information within the associated

information-processing context. In the understanding of this paper, models, and

in particular prediction models, are special symbols themselves. The

self-organisation of prediction models, suggested here as a transition between

the models of Figures F1.2 and f1.1, requires the emergence of symbols, requires

the transition from the transfer of structural information to the transfer of

symbolic information in repeated interaction with an outside world.

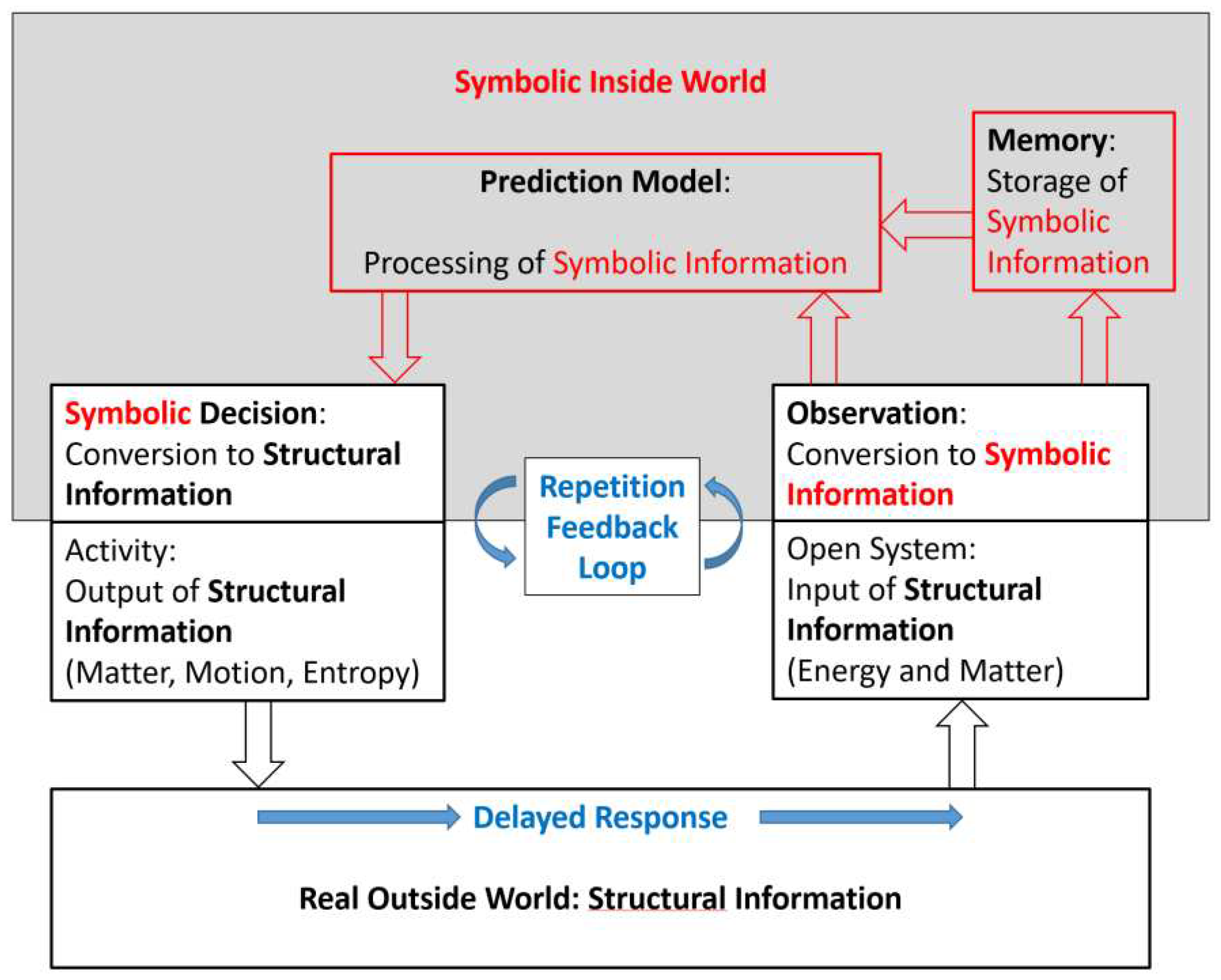

By humans or any other living

beings, decisions made now will matter only later on in the future.

Beneficial decisions require good prognoses. Causal models can exploit

past experience to predict upcoming events or circumstances. By appropriate

receptors, after suitable conversion to symbolic information, structural

information received from the environment may be filtered and stored in

suitable symbolic form. After having passed through a symbol-processing model,

the symbolic result needs to be transformed back into structural information

transmitted to the environment, such as by triggered mechanical activity,

incarnating the actual decision.

Living organisms are self-organised

dissipative structures. To stay alive and multiply, they need permanent supply

of high-valued energy to compensate the inevitable production and export of

entropy, to assemble and accumulate energy-rich molecules that make up the

body, as well as to supply internal energy stocks to be exploited for driving

active behaviour. The latter is ruled by a series of decisions of what needs to

be done when and how, being permanently made by any living being, from the

simplest singe-cell up to human life and labour. The future fate of an organism

is affected by any decision derived from experience made in the past and

triggered by suitably adjusted prediction models, estimating what is expected

to come. By trial and error, symbolically stored sensational experience is used

to evaluate the success of previous decisions and to modify the prediction

model accordingly.

The self-organisation of

prediction models requires several qualitative steps, although not necessarily

in this temporal sequence:

- (i)

Symbols need to emerge from non-symbolic, structural information processing,

- (ii)

Sensors need to emerge which convert received structural information into symbolic information,

- (iii)

Experience in the form of symbolic information needs to be stored in memory,

- (iv)

Symbols need to be combined in networks to form symbol-processing models,

- (v)

Symbols produced by models represent the evaluation result of the processed experience, and

- (vi)

Decision-making models convert symbolic values back into structural information of activity.

In natural evolution, this process

is typically rolled out from the end. Internal information processing developed

and advanced any already existing activities to become more and more diverse,

sophisticated, effective and beneficial with respect to survival. Simple organisms

perform certain mechanical or chemical activities without recognising any

environmental signals. “Lower animals often possess a richer embodiment of

their activity system as compared to a poor perception system” (von Uexküll

1973: p. 161). Subsequently, structural information from the surrounding, such

as temperature or brightness, may affect the organism’s metabolism. If this

enhances the fitness, direct physical impact may develop into specialised

reception of selected external signals. Direct physical links (structural

information) between receptor and effector may turn into more versatile

symbolic information transfer by the ritualisation transition. Chemical

symbols, such as specific indicator molecules, may be processed by logical

gates such as NOT or AND, as this is known from properties of allosteric

enzymes (Oubrahim and Boon Chock 2016), similar to information processing in

electronic computers. Networks of this kind may recognise signals of a certain

duration rather than just instantaneously happening conditions, that is, they

may build up memory devices.

The paper is organised as follows.

Prediction models emerge and work between sensual perception and decided action

of individuals, between input of structural information converted to symbolic

one, and output of structural information after conversion from symbolic one.

In

Section 2

, the

terms “symbol” and “model” are specified and compared with other common similar

words. In

Section 3

, the relation of causality and final causality to prediction models

is discussed. The role of decisions, physical as well as symbolic decisions, as

a transformer of symbolic to structural information is considered with simple

physical examples, such as homoclinic orbits, in

Section 4

. Symbolic

information is compared to structural information in greater detail in

Section 5

, and the

self-organised emergence of novel symbolic information out of existing

structural information by the ritualisation transition, as the key process for

the self-organisation of prediction models, is characterised by selected

contrasting properties in

Section 6

. The paper is discussed from a more general perspective in

Section 7

. To assist the

reading,

Appendix A

reviews selected general properties of self-organisation processes

and phase transitions. With respect to the origin of life,

Appendix B

explains briefly a

conceptional ritualisation scenario.

2. Symbols and Models

Computer bits, feather colours or

printed letters are symbols. Words like “energy”, “entropy”, “information” or

“symbol” are also symbols. In the literature, in particular in semiotics,

symbols may also be regarded as “signs”, “icons”, “displays” or “signals”

(Oehler 1995, Deacon 1997, Nöth 2000, Pattee 2001, Feistel 2023). Within some

external context,

symbols are physical structures that represent

something else than themselves, namely, the symbol’s

meaning. The

relation between the symbol’s structure and its meaning is arbitrary and

assigned by convention (Nöth 2000, Lacková et al. 2017). Arbitrariness, that

is, neutral stability with respect to fluctuations among any arbitrary suitable

carriers, is a specific functional symmetry of symbol-processing systems

(Feistel 1990, 2017a,b, Feistel and Ebeling 2016). Accordingly, the

self-organised emergence of arbitrariness has properties of a kinetic phase

transition of the 2

nd kind, see

Appendix A

. The corresponding

fundamental character of this arbitrariness, of the purely conventional

character of the relation between the physical structure of a symbol and its

meaning, was proposed to be termed the

central dogma of semiotics by

Deacon (2021).

Models do exist for the climate, for a steam engine or for sailing

vessels. Construction plans, cooking recipes or genetic strands are also models

for the physical structures that appear by execution of those symbolic

instruction sets. Some authors understand models as opposed to theories; not so

here. Following Stachowiak (1973: p. 56), “a model is likewise … the most

elementary item of perception as well as the most complex, most comprehensive

theory.” “The word ‘model’ … is used … to mean an approximate description of an

aspect of reality, with this description being developed for a specific

purpose“ (Willink 2013: p. 16).

Models represent something else than they

physically constitute in their own right. This property specifies models to be

a special class of symbols. Typically, models are complex, consisting of

structured sets of simpler, more elementary symbols. Similar to symbols, which

may also represent other symbols rather than directly any physical reality,

models may also represent other symbols or models. The text of this paragraph,

for example, is a model of a model, similar to any other scientific article

which consists of ordered sets of symbols (letters, words, numbers, figures)

representing the research object, be that an observed or measured physical

structure or another model (theory, hypothesis, simulation). Similarly, the

notion of entropy is a model for certain fundamental properties of a

macroscopic physical object, rather than being any kind of real physical

“substance” itself. Sets of mutually consistent models are not necessarily

pairwise reducible to one another, as if they were forming this way a connected

group or semigroup of models. Irreducible such models are often described as emergent

models, quantities or properties (Butterfield 2012, Fuentes 2014, Feistel and Ebeling 2016).

A particularly important group of models is that of

mental models (Craik 1943) implemented in brains of higher animals,

especially of humans. Mental models result from the combination of phylogenetic

(inherited) experience and ontogenetic (individually undergone) experience.

Highly relevant for physicists and philosophers is the human model of naïve

realism (Born 1965a, b). “The reality of a simple, untaught human is what

he/she [immediately] feels and recognises. … The reality of those things which

surround him/her is self-evident to him/her. … This attitude is termed naïve

realism. The large majority of humans remains with that” (Born 1965a: p. 53,

54). “Naïve realism is a natural attitude expressing the biological situation

of humans and all animals” (Born 1965b: p. 106). Naïve realism is a

self-organised mental model as the result of successful Darwinian survival of

all ancestors in the past (Hoffman 2020, Feistel 2021, 2022, 2023), rather than

an a-priori principle of human understanding (Kant 1956), possibly of divine

origin.

Most models serve as prediction models, directly or

indirectly. In symbolic form, they provide estimates for expected future

observations, derived from similar experience already stored symbolically in

memory, in combination with recent input, such as sensation suitably converted

to symbols (

Fig. f1.1). In turn,

observationally successful predictions serve as criteria for the reliability of

the responsible model, to be used again in the future upon repetition of

similar sensations. By repetition, models accumulate information about

properties of the represented object, such as the real outside world.

Causality, as a hypothetically lawful link between repeatedly observed

correlated events, is an established construction principle for empirical

prediction models. “Only after an activity has been performed and therefore

belongs to the past, are we entitled to an attempt of understanding it from the

perspective of causality”

2

(Planck 1937: p. 29).

Causal models are the most successful prediction

tools. “The validity of the causal law is connected with the

possibility of making correct predictions for the future” (Planck 1948b: p. 3).

“If it is the task of science to look for lawful relations in all what happens

in Nature and in human life, an inevitable prerequisite for that is … that such

a relation in fact exists, and may be described in clear words. In this sense

we tend to talk about the validity of a general causal law and about the determination

of all processes in the natural and the mental world by this law. However, what

does it mean that a process, an event, an activity occurs with lawful

necessity, is causally determined, and how can the lawful necessity of a

process be detected? I have no better idea to provide a clearer and more

convincing proof for the necessity of a process than by the possibility of

predicting the occurrence of the particular process”

3(Planck 1937: p.5).

Sudden deadly risks cannot be learned by individual

ontogenetic experience because the killed organism cannot store this

information in its memory for later. Organisms, however, which due to randomly

modified prediction models instinctively avoid related risky situations, can

inherit their survival strategy as phylogenetic experience. Such warnings may

appear emotionally as a diffuse “fear” without causal justification. This

indirect feedback mechanism is related to the psychological phenomenon of

biased recognition known as silent evidence (Taleb 2008). When

after an earthquake a few survivors praise their god for saving their lives,

while the many killed victims fail to oppose, than the earthquake finally

appears as a convincing reason to trust in god. Winners write history.

Prediction models may exploit information about never-experienced events.

Symbols and especially models have two conjugate

aspects, on the one hand the way they emerge by self-organisation, and on the

other hand the way they are used in systems processing symbolic information

(Feistel 2023). The first aspect may be denoted as the design time of a

symbol; this process is described here as the ritualisation transition.

The second aspect may be denoted as run time of a symbol which is

denoted as a symbolisation process that takes place, e.g., during an

observation or a measurement that extracts symbols such as nerve pulses or

measured numbers from structural information of the given external object or

measurand. “Measurement is a form of symbolisation. It consists in assigning

numerals to objects or quantities” (Craik 1943: p. 75).

3. Causality and Finality

Although causality cannot be

perceived in nature (Hume 1758, Russel 1919), it is an extremely useful concept

for the construction of prediction models, especially of human mental models

(Kant 1956, Planck 1948b, Feistel 2023). The physical concept of causality is a

strictly irreversible one (Prigogine 2000, Riek 2020): a cause always precedes

its effect in time. In the literature of philosophy, biology and semiotics,

however, also a final causality, or finality, or retrocausation

is extensively discussed as the phenomenon by which the final result of a

process is actually assumed to be its “cause” (Sapper 1928, Nöth 2000, Nomura

et al. 2019, Pink 2021, Deichmann 2023). Actually, prediction models may

provide a logical link between the two disjunct causalities.

Why at all are there symbols?

Darwinian selection demands the use of prediction models by the competitors in

order to gain selective advantage. In turn, causal prediction models require

the prior emergence of symbols. In this sense, the “purpose” or “final cause”

for the existence of symbols and for the self-organisation of the ritualisation

phenomenon is the need for prediction that arose from the possibility of

prediction by gradually modifying random trial activities. Symbol processing

makes prediction faster, energetically cheaper, more effective, more reliable

and more flexible, similar to digital technology as compared to its analogue

forerunner. Concerning systems that are equipped with an appropriate prediction

model, finality is consistent with causality. However, not the system’s future

state is controlling and “causing” the system’s development but rather the

inherited prediction model which is attempting to repeat the previous success

of its predecessor’s mature structure and processing. This successful

repetition is possible under the requirement of environmental continuity, of

persistent boundary conditions. If, otherwise, the system’s external conditions

change so quickly and dramatically beyond some critical tolerance limit, the

system will fail to achieve the expected mature state because the prediction

model becomes unable to properly predict the result of the development under

the altered boundary conditions.

Darwinian evolution relies on such

a continuity principle (Feistel 2023): “the world must be predictable for an

organism to live therein” (Eibl-Eibesfeldt 1998). “For any form of life, from

unicellular organisms to large-brained mammals, living in a predictable

environment is essential for increasing its chances for survival” (Nomura et

al. 2019: p. 267). If the parental genetic survival recipe suddenly turns

inappropriate to also ensure offspring survival because of environmental

discontinuity, evolution cannot take place by trial and error and by gradual

accumulation of symbolic information in successively improving prediction

models. While, say, cyanobacteria have a wide tolerance range to survive under

strongly varying conditions, highly specialised species such as dinosaurs or

humans run a higher risk of extinction. The pace by which the global human

population is currently overturning the terrestrial ecosystem has become

intolerably fast for numerous other recent species; they can no longer adapt

their genetic prediction model by the traditional mutation-and-selection

mechanism. Final causality as fitness for purpose may not function in those

cases.

Evolution established deliberation

as a prediction method of mammals which permits quick reactions and decisions

about their immediate activity under circumstances never experienced before

(LeDoux 2021). Evolution established sex (Smith 1988, Margulis 2017) as

the most successful method to survive unpredictable situations, especially

during population bottlenecks, by keeping available a variety of alternative

genetic prediction models. Sexual reproduction and selection gave rise to the

evolution of a spectacular wealth of new symbols used in mating activities

(Darwin 1859, Prum 2017). The price to pay for the benefits of sex, however, is

the individual death (Margulis 2017).

Physical causality is an

asymmetric binary relation between certain pairs of events. For a network of

events, causality represents a mathematical semigroup rather than a group as

not necessarily each pair of events is mutually linked. If events are

represented by nodes and their causal links by arrows, a causal network may be

described by a directed graph or a non-negative adjacency matrix (Frobenius

1912, Lancaster 1969, Gantmacher 1971, Feistel and Ebeling 1978b, Feistel 1979,

Ebeling and Feistel 1982, Bornholdt and Schuster 2003). Final causality, if

understood as a cause appearing later than its effect, violates the semigroup

model of physical causality. Similarly, in science-fiction films and novels,

fictitious time travel, the heroes carry their mental prediction models along

with their stored experience back to the past, so that the memory can

symbolically “remember the future”. This is inconsistent with the causality

semigroup properties and implies logical contradictions.

Likely, prediction models are

physical systems that causally combine and connect symbols of events as

semigroups in a similar way as those had been observed of real, structural

events. It may be assumed that the expected sequence of symbolic events in the model

is represented also by an irreversible structural process, percussing previous

experience in a simplified form.

4. Physical and Symbolic Decisions

A popular example for a decision

is the millennium-old parable of “Buridan’s Ass”, named after the French

philosopher Jean Buridan: a donkey placed exactly amid two equal stacks of hay

is unable to decide for one and will eventually die of hunger. Mathematically,

the donkey is located at a saddle point of a fictitious “surface of happiness”

with two equal maxima to the left and right. Tiny fluctuations may suffice to

break this symmetry at the initial unstable steady state and to trigger a

decision toward one of the heaps.

Decisions

play a key role in human personal and social life. Back to Adam

Smith (1776), disciplines such as “decision theory” or “best-choice theory”

typically investigate problems related to reasons for, and consequences of,

individual decisions in the society. In the case of human decisions, those are

often regarded as “free will” (Planck 1937) and are widely and controversially

disputed in the literature (Pauen and Roth 2008, Pink 2009, Maldonato 2012).

However, decisions, in the particular sense as specified below, are more

fundamental acts for biology in general than just those of humans. “Decision

theory provides a means to find the optimum response given uncertain

information by weighing appropriately the costs and benefits of each potential

response” (Perkins and Swain 2009: p.1). Prediction models are built to deliver

symbolic information which leads to decisions by evaluating and comparing the

expected benefits; asking for the physical roots of the self-organisation of

such models implies the question for physical roots of the self-organisation of

decisions. Here, we shall discuss certain aspects of

physical decisions

and of

symbolic decisions, assuming that those represent a physical

basis of biological behaviour from the very beginnings up to human interests

and related activities. The importance of decision (or choice) for symbolic

information processing (or semiotics) in combination with prediction,

experience and memory has already been emphasised previously by Kull (2018),

who quoted Viktor von Weizsäcker’s (1940: p. 126) statement that “the process

of life is a decision rather than a succession of cause and effect“

4. “By ‘semiosis’ we mean the process of choice-making between

simultaneously alternative options” (Kull 2018: p. 454).

“There is a large number of new

phenomena which are associated to irreversibility, and appear only in systems

far from equilibrium. … In front of a bifurcation, you have many possibilities,

many branches. The system ‘chooses’ one branch” (Prigogine 2000: p. 5). When a

straight elastic column is put under pressure, beyond a critical load it will

suddenly bend, a phenomenon known as Euler buckling (Zeeman 1976). In

the simplest case, the column has two options, to bend to the left or to the

right. The decision to which side to bend depends on small fluctuations,

asymmetric structures or boundary conditions. Typically, the physical process

initiating the decision occurs at an energy level much lower than that of the

amplified processes that “explode” due to feedback processes in accelerated

manner after the decision was made. In this sense, a physical decision is a

macroscopic amplification of a chosen option out of a microscopic manifold of

those.

Let a physical decision be

a macroscopic process triggered by a microscopic event, such as an avalanche

released by a tiny tremor, a bomb exploding after a slide touch of its

detonator, or the sudden freezing-over of a supercooled liquid after a local

thermal fluctuation. The fertilisation of an egg cell to form a zygote is a

physical decision to start pregnancy. A physical decision is an apple that

suddenly falls from a tree, or a spark igniting a wildfire. Physical decisions

occur at unstable or metastable states (Summers 2023); they are irreversible

and produce entropy.

An instructive dynamical model for

a system capable of physical decisions is a homoclinic orbit (Shilnikov

1969, Gaspard et al. 1984, Drysdale 1994).

"Shilnikov homoclinic orbits are

trajectories that depart from a fixed saddle-focus point … and return to it

after an infinity time" (Medrano et al. 2005: p.1).

If several different homoclinic orbits start from the same

stationary point, a system may, by microscopic fluctuations, “decide” which

orbit to follow, performing the orbit’s macroscopic dynamics as an “activity”,

before returning asymptotically to the initial waiting state. The simplest model

for such a decision is a saddle-type homoclinic orbit (Drysdale 1994) with two

leaves representing alternative decisions and performed activities.

A simple saddle-type homoclinic

orbit is shown in

Fig. f4.1

. A related possible system of canonical-dissipative equations

(Graham 1973, 1981, Feistel and Ebeling 1989) is,

with the functions

and

. The dissipation inequality

implied,

shows that the system possesses a

homoclinic orbit (

Fig. f4.1) of the shape of a lemniscate,

. The steady state at (0, 0) is a

saddle point. Fluctuations in its stable directions let the system immediately

return to the origin. Fluctuations in either of the unstable directions trigger

macroscopic excursions after which the system finally returns to the original

state. Such a model may conceptionally reflect decisions such as those being

made by an animal confronted with an enemy. The animal may either hide and do

nothing, or decide to take the flight, or to attack.

Let a symbolic decision be

a physical decision in the form of structural information that is triggered by

symbolic information, see the following section. For example, for humans, the

consequences of speech acts which are “doing things with words” (Austin

1962, Bühler 1965) are typical symbolic decisions. When at her wedding the

bride declares “yes, I will”, then this symbolic message of just three words

given to the audience will dramatically change her future social and personal

life. When on a market some bargain ends with “deal”, then the offered goods

will instantaneously exchange their owners and will face an altered fate. Such

a deal is usually the result of a cost-benefit analysis performed by mental

prediction models of the participants. As an aside, the German word for “to

exchange” is “tauschen”, a word that has common roots with “täuschen”, meaning

“to deceive”, to mislead the opponent’s prediction model.

Mechanical switches used to start

or stop engines are devices for making physical decisions, releasing

significant amounts of energy upon a minor energetic effort such as pushing a

button. Those become symbolic decisions as soon as the switch is operated

electronically by symbolic computer bits rather than mechanically by human

fingers. By virtue of its effect, a symbolic decision assigns a

structural

meaning to a symbol. While observation translates external structural

information into internal symbolic information,

Fig. f1.1

, decision is the

counterpart that translates symbolic information into structural information of

action, physically affecting the external world. Symbolic information in its

own right is useless; it gains its relevance only in connection with associated

structural information that ultimately appears as a result of a symbolic

decision. Such a “magic power” of symbols is marvelled in numerous legends and

fairy tales.

5. Structural and Symbolic Information

Prediction models are used to

transform available information about the past and present into yet unavailable

information about the future. However, the meaning of the term information

varies widely in the scientific and other literature. Here, information

is a term used for special physical processes or structures, or for certain

properties of those. Information carriers are structures requisite for

any transfer, storage and processing of information. There is no information

without a physical carrier, quite in contrast to the understanding of some

authors who assume information to be the substance of which the world

ultimately consists. With respect to the physical carrier structures,

information itself is an emergent quantity, something assigned to those

structures by an external context or agent. Occasionally, information itself is

regarded as some physical quantity similar to entropy, as it may obey

conservation and dissipation laws, and it may possess an amount and a value.

When receiving the honorary

citizenship of Pescara in Italy, Ilya Prigogine (2000) said in his inauguration

speech with respect to certain physical information theories that “the pleasure

of being invited to this beautiful ceremony, and my friendship with Professor

Ruffini, would have been included in the information at the big bang. But that

seems very strange, and I could never accept this view.” In this quotation, by

“information”, physical structural information is meant that may (or

rather, may not) had been preformed already at the big bang, in absence of any

symbols, and has nonetheless been perfectly conserved from then on to the

present day, and to any future yet to come. Such a putative conservation of

structural quantum information, known as »Hawking’s information paradox«, is

subject to recent gravity research (Almheiri et al. 2020). It is well known,

however, that the macroscopic loss of information as a consequence of Clausius’

law of irreversibly increasing entropy is inconsistent with the microscopic

reversibility of classical mechanics (Feistel and Ebeling 2016), and a similar

inconsistency can neither be excluded for quantum effects. All these physical

laws apply to structural information.

In this paper, structural

information is distinguished from symbolic information. It is

understood that any physical structure carries structural information just by

its very existence. Symbols, the way they are introduced here, are

physical structures which additionally carry symbolic information. The latter

is assigned to the structure in the context of an external

information-processing system by convention, not reducible to the

symbol’s intrinsic structural information. For example, a printed word carries

a certain meaning as its conventional symbolic information which is independent

of the word’s structural information such as the kind of ink or paper used for

printing. Symbols represent something else than themselves. Physically, the conventionality

or arbitrariness of the symbol’s meaning corresponds to a Goldstone

mode, expressed by a vanishing Lyapunov coefficient of the system’s

dynamical equations with respect to fluctuations that replace the given

structure by a different one with the same meaning. For example, if a text is

typed in “Sans-serif” letter font and is replaced by the same text in “Arial”,

the meaning of the text remains unaffected, and there is no physical

restauration or relaxation force that tends to return the text to “Sans-serif”.

The discovery of planet Neptune

may serve as an example for the relation between structural and symbolic

information. Observational data of planet Uranus published by Bouvard in 1821

deviated significantly from values predicted by Kepler’s mathematical model. Le

Verrier could explain the discrepancies mathematically by the existence of a

yet unknown planet, Neptune, which could indeed be observed near the suggested

position by Galle in 1846. This famous history can be understood in a way that

the perturbation of Uranus’ orbit represents structural information that was

transferred from Neptune to Uranus by gravity interaction. The existence and

certain properties of Neptune are physically present in Uranus’ trajectory. By

measuring Uranus’ motion, this information was converted to symbolic

information in the form of numerical tables. By exploiting this experience, a

mathematical prediction model then provided the hypothetical position of

Neptune in the sky. By the decision of pointing a telescope to that spot, the

symbolic model result was converted back to structural information. The light

observed from that star, again as structural information, could be observed and

converted again into symbolic information in the form of scientific

communication about the new discovery, as a validation of the prediction.

Great apes can learn to use some

words. They never did that themselves, but were always taught by humans. By

contrast, nobody had ever taught early humans to use words to speak or write.

The human use of language is definitely self-organised. In the course of the

natural evolution of life, including humans, symbols emerged by

self-organisation in a ritualization process. Similarly, the emergence of the

genetic code and the symbolic information it represents can be assumed to have

occurred by self-organisation. A simple conceptional model for the origin of

life understood as a ritualisation transition is briefly presented in

Appendix B

.

6. Properties of the Ritualisation Transition

Prediction models are special symbols; the self-organisation of prediction models became possible only along with the self-organisation of symbols. This relation makes ritualisation, as the key process for the emergence of symbols, a crucial event also for the evolution of prediction models. Ritualisation had previously been defined to be (Feistel 2017b)

- -

“the gradual change of a useful action into a symbol and then into a ritual; or in other words, the change by which the same act which first subserved a definite purpose directly comes later to subserve it only indirectly (symbolically) and then not at all” (Huxley 1914),

- -

a process by which behavioural or physical forms, or both, that had originally developed to serve certain different purposes for communication within a population (Lorenz 1970),

- -

the modification of an animal behavioural pattern to a pure symbolic activity (Eibl-Eibesfeldt 1970),

- -

the development of signal-activity from use-activity (Tembrock 1977), or as

- -

the self-organised emergence of systems capable of processing symbolic information (Feistel and Ebeling 2011).

Typically, in the course of

evolution, three stages of a ritualisation transition are observed: before,

during and after the transition (Feistel 1990, Feistel and Ebeling 2011). Initially,

the existing structure is only slightly variable in order to maintain the

system’s essential functionality. Successively, involved structures may

gradually reduce to some rudimentary, simplified version of themselves, to

“icons” or “pictograms”, which represent the minimum complexity requisite for

the actual task (Klix 1980). As a kind of caricature this may be a modified, a

skeleton representation of the original structure in a way that emphasises some

relevant characteristics and simplifies or omits others, irrelevant ones.

Redundant partial structures are no longer supported by restoring forces, and

related fluctuations may increase substantially. At the transition point, the

“icons” turn into mere symbols that may be modified arbitrarily, thus expressing

the emerging code symmetry, and permit divergent, macroscopic fluctuations, see

Appendix A

. As a

result, the kind and pool of symbols may quickly enlarge and adjust to new

external requirements or functions. Later, in a maturation phase, the code becomes

standardised to maintain intrinsic consistency and compatibility of the newly

established information-processing system. Fluctuations are increasingly

suppressed, the code becomes frozen-in and preserves in its remaining arbitrary

structural details a record of its own evolution history. For example, in the

ritualisation of spoken and written language, of numbers or of gestures, all

these stages appear in similar, more or less pronounced form (Feistel 2017a,b,

2023). “In all aboriginal languages, vestiges of these sounds of nature are

still to be heard; though, to be sure, they are not the principal fibres of

human speech” (von Herder 1772).

Symbolic information has some

general properties (Feistel and Ebeling 2011):

- (i)

Symbolic information systems possess a new symmetry, the carrier invariance. Information may loss-free be copied to other carriers or multiplied in the form of an unlimited number of physical instances. The information content is independent of the physical carrier system used.

- (ii)

Symbolic information systems possess a new symmetry, the coding invariance. The functionality of the processing system is unaffected by substitution of symbols by other symbols as long as unambiguous bidirectional conversion remains possible. In particular, the stock of symbols can be extended by the addition of new symbols or the differentiation of existing symbols. At higher functional levels, code invariance applies similarly also to the substitution of groups of symbols, synonymous words or of equivalent languages.

- (iii)

Within the physical relaxation time of the carrier structure, discrete symbols represent quanta of information that do not degrade and can be refreshed unlimitedly.

- (iv)

Redundant copies of symbolic information may be carried along for error correction in cases of loss or damage of the original.

- (v)

Imperfect functioning or external interference may destroy symbolic information but only biological processing systems can generate new or recover lost information.

- (vi)

Symbolic information systems consist of complementary physical components that are capable of producing the structures of each of the symbols in an arbitrary sequence upon writing, of keeping the structures intact over the duration of transmission or storage, and of detecting each of those structures upon reading the message. If the stock of symbols is subject to evolutionary change, a consistent co-evolution of all components is required.

- (vii)

Symbolic information is an emergent property; its governing laws are beyond the framework of physics, even though the supporting structures and processes do not violate physical laws.

- (viii)

Symbolic information is extracted from structural information by observation or measurement processes.

- (ix)

Symbolic information has a meaning or purpose beyond the scope of physics which becomes revealed by conversion to structural information, such as by symbolic decisions.

- (x)

In their structural information, the constituents of the symbolic information system preserve a frozen history (“fossils”) of their evolutionary pathway.

- (xi)

Symbolic information processing is an irreversible, non-equilibrium processes that produces entropy and requires free-energy supply.

- (xii)

Symbolic information is encoded in the form of structural information of its carrier system. Source, transmitter and destination represent and transform physical structures.

- (xiii)

Symbolic information exists only in the realm of life.

Structural information has a number of different general properties (Feistel and Ebeling 2011):

- (i)

Structural information is inherent to its carrier substance or process. Information cannot loss-free be copied to any other carrier or identically multiplied in the form of additional physical instances. The physical carrier is an integral constituent of the information, meaning and structure cannot be separated from one another. The state of the physical context of the system is an integral part of the information.

- (ii)

There is no invariance of structural information with respect to structure transformations. Different structures represent different structural information.

- (iii)

Structural information emerges and exists on its own, without being produced or supported by any kind of separate information source. No coding rules are involved when the structure is formed by natural processes.

- (iv)

Over the relaxation time of the carrier structure, structural information degrades systematically as a consequence of the Second Law, and disappears when the equilibrium state is approached.

- (v)

Internal physical processes or external interference may destroy structural information; it cannot be regenerated or recovered. Periodic processes can rebuild similar structures but never exactly the same, in particular because the surrounding world will never be exactly the same again at any later point of time.

- (vi)

Structural information is not represented in the form of codes. No particular coding rule or language is required or distinguished to decipher a structure.

- (vii)

Structural information is a physical property; it is represented by the spatial and temporal configuration of matter, its governing laws are the laws of physics.

- (viii)

Structural information is of physical nature and is independent of life.

7. Discussion

Key aspects of seemingly unrelated

scientific topics such as Leibniz’ (1765) “Final Cause”, Hume’s (1758)

“Scepticism”, Darwin’s (1859) “Natural Selection”, Peirce’s “Semiotics” (Nöth

2000), Huxley’s (1914) “Ritualisation”, Born’s (1965a,b) “Naïve Realism”,

Prigogine’s (1969) “Dissipative Structures”, Gilbert’s (1986) “RNA World”,

Pattee’s (2001) “Physics of Symbols” or Hoffman’s (2020) “Relative Reality” may

jointly be considered from a common perspective of self-organised prediction

models. Active decisions governed by prediction models may be regarded as a

universal property of life, independent of specific biochemical details or

terrestrial conditions, and also including non-Darwinian forms of “honorary

life” such as market economy, scientific or technological artefacts such as

computers or artificial intelligence. First prediction models emerged by

self-organisation in the course of coevolution of sensual reception, symbol

processing and memory, and decisions on activities. Typically,

self-organisation is characterised by a spontaneous formation of novel,

“dissipative” structures or functions induced by symmetry-breaking kinetic

phase transitions far from thermodynamic equilibrium, such as oscillations of a

hydrothermal geyser. Symbols may emerge in a similar manner by a universal

kinetic transition that had been termed “ritualisation” in ethology,

introducing arbitrariness as a new additional symmetry into information

processing. Ain

Appendix B

, a conceptual model for the origin of life is painting a simplified

picture of the primordial ritualisation transition to the very first symbols

and models. A similarly fundamental success of the self-organised emergence of

symbols such as language and numbers, and of causal mental prediction models is

characteristic also for the historical ascent of humans.

Here are some widely known but

rather different examples, related to selected features of prediction models:

- -

Phylogenetic experience: When Darwin (1859) wrote his famous book “On the Origin of Species”, he mentioned in his Chapter 1 various examples for the variability of phenotypic properties between parents and offspring: “When among individuals … any very rare deviation … appears in the parent … and it reappears in the child, the mere doctrine of chances almost compels us to attribute its reappearance to inheritance. … Perhaps the correct way of viewing … would be, to look at the inheritance … as a rule, and non-inheritance as the anomaly. The laws governing inheritance are for the most part unknown”. Despite that, only a few years later, Mendel’s (1866) empirical inheritance rules went largely unnoticed by the scientific community. It took another century until Watson and Crick (1953) as well as Nirenberg and Matthaei (1961) revealed the molecular symbolic memory behind biological inheritance, known today as the “genetic code”. In this paper, the genetic information is considered as an inherited prediction model, self-organised previously in the course of Darwinian selection by the long and unbroken track of successful ancestors, this way keeping their accumulated phylogenetic experience available for the offspring as a predicted instruction set for the offspring’s subsequent survival and multiplication. This process may be regarded as Darwinian evolution of prediction models in the sense of Dawkins’ (1976) “selfish genes”.

- -

Ontogenetic experience: When Pavlov in 1905 measured the salivation of a dog in the lab, he noticed that already the sound of the walking technician started watering the dog’s mouth in expectation of the food the same person had always been providing. This classical conditioning (Denny-Brown 1928) is controlled by a mental prediction model that had been established before by repeated recognition of correlated events during the individual ontogenetic experience in the past. To make this happen, sensual impressions must be recorded symbolically in memory. Triggered by a repeated event, this information must be recalled and processed by the model in order to predict and await the yet missing events of the formerly observed scenario. “Brains are … essentially prediction machines” (Clark 2013: p. 181). The concept of mental models was developed by Craik (1943).

- -

Scientific prediction laws: When Clausius (1876) studied cyclic thermal processes of heat engines, he mutually compared numerous measured values of heat supply,

, at temperatures,

. He found that cycles with

are technically impossible: „Die

algebraische Summe aller in einem Kreisprocesse vorkommenden Verwandlungen kann

nur positiv oder als Grenzfall Null sein“

5.

As a fundamental theorem, he concluded that “ein Wärmeübergang aus einem

kälteren in einen wärmeren Körper kann nicht ohne Compensation stattfinden“

6. This

natural

law is a prediction model for, say, the maximum efficiency of any modern

heat pump. Clausius (1865: p. 390, 1876: p. 94, 111) proposed a new

thermodynamic state quantity,

,

termed “entropy” (“Verwandlung”, transformation, greek “τροπή”) by him (Feistel

and Ebeling 2011, 2016). His most famous prediction was: “Die Energie der Welt

ist constant. Die

Entropie der Welt strebt einem Maximum zu”

7. Physical “natural” laws are

symbolically formulated human models (Feistel 2023), derived from past

observations in order to predict results of future observations or

measurements.

- -

Observation-prediction-action cycle: Brahe’s meticulous observation of stars between 1586 and 1597 enabled Kepler to discover his pioneering laws of planetary motion, published in the books Astronomia nova of 1609 and Harmonices mundi of 1619. In 1687, Newton could demonstrate that his fundamental physical laws of bodily motion and of universal gravity were sufficient to correctly derive Kepler’s findings mathematically. Kepler’s laws allowed successful predictions of the solar transits of Mercury in 1631 and of Venus in 1639, and later even the discovery of Neptune in 1846. In remote space regions never directly experienced by humans before, predictions by those laws gave rise to the first successful flight of an artificial celestial body, “Sputnik”, in 1957, confirming the merely symbolic predictions of astronomers in the form of structural information. Newton’s dynamical differential equations offer more comprehensive predictions than Kepler’s conservation laws of energy and angular momentum provide. “The ultimate goal of celestial mechanics [was] to resolve the great problem of determining if Newton’s law alone explains all astronomical phenomena” (Poincaré and Goroff 1993: p. I17).

- -

Causal prediction models: “Mathematically, the law of causality is expressed by the fact that physical quantities obey differential equations of a certain kind. The causal law of classical physics implies that the knowledge of the state of a closed system at some point of time determines its behaviour for all of its future” (Born 1966: p.7). Causality is a key element of the human mental model of naïve realism. Causality does not exist in reality (Russell 1919: p. 180) nor can it be observed: “Through its sensational properties, no object may ever reveal the causes that produced it nor the effects that will result from it” (Hume 1758: p. 44). However, causality is an unrivalled human mental prediction tool (Orcutt 1952). The historical success of causal mental models made humans addicted to causal explanations for their personal observations, such as by superstition, religion or science (Planck 1948a: p. 23, Feistel 2023). “The human brain is the most advanced tool ever devised for managing causes and effects. … Causal explanations, not dry facts, make up the bulk of our knowledge” (Pearl and Mackenzie 2019: p. 2, 24). „We struggle for attributing cause and effect. Seeing events causally connected is an outstanding strategy to master our daily life“ (Mast 2020: p. 32).

- -

Mental prediction models: The neuronally implemented, inherited prediction model of naïve realism emerged by self-organisation in the course of Darwinian evolution (Hoffman 2020, Feistel 2023). By introspection, Kant (1956) painted a detailed picture of human naïve realism. Eighty years before Darwin (1859), lacking a better explanation, Kant described causality as an a-priori principle of reason rather than an empirical conclusion from phylogenetic experience. The alternative advantages either of exploiting intergenerational, phylogenetic experience stored in genetic information, or of fast and flexible individual, ontogenetic experience stored in brain memory, became combined by socially distributed prediction models of science and technology of humans, permitted by the self-organisation of spoken and written language (Logan 1986, Pinker 1994, Deacon 1997). Sagan (1978: p. 39) regarded this kind of accumulated symbolic information as an “extrasomatic-cultural” one.

- -

Non-causal prediction models: Scientific prediction models are not necessarily causal ones. For the description of technical or natural processes, for example, the quantitative knowledge of certain properties of physical objects may be required. Typically, a finite set of such properties is carefully measured and symbolically tabulated, similar to Brahe’s star-gazing, and subsequently represented mathematically by a continuous function, similar to Kepler’s and Newton’s laws, which predicts the properties under any other, not yet measured conditions. This way, as a special case, properties of water, seawater, ice and humid air are described in the form of empirical thermodynamic potentials by the international standard TEOS-10, the “Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater - 2010”, for use in numerical models for climate, oceanography or desalination (IOC et al. 2010, Feistel 2018, Harvey et al. 2023). Such predicted property values should always be associated with estimated uncertainties (GUM 2008, Willink 2013, Feistel et al. 2016). The method of mathematical inter- and extrapolation, generalising locally observed situations to previously unexplored ones, is a powerful non-causal mental prediction tool that likely evolved from first geometric measurements in agriculture (Hilbert 1903) and is still successfully applied in latest science.

Appendix A. Self-Organisation and Phase Transitions

The term self-organisation

describes a macroscopic phenomenon by which the system’s uniform elements

spontaneously exhibit some cooperative behaviour. “We use the term

cooperative in the physico-chemical sense as referring to systems with

correlated molecular motions. Order-disorder processes and phase

transformations are familiar examples of cooperative phenomena” (Kirkaldy 1965:

p. 966). As a special case, at certain conditions, thermodynamic equilibrium

systems may start separating into different phases or de-mixing of its

constituents, such as an ice cover forming on a lake. Equilibrium phase

transitions are traditionally classified into ones of the 1st kind,

such as liquid water at the freezing point, and of the 2nd kind,

such as the loss of ferromagnetism at the Curie point (Landau and Lifschitz

1966).

Phase transitions of the 1st

kind

are characterised by the possible coexistence

of the two phases which are well distinguished from one another (such as liquid

and vapour) and may or may not possess different symmetries (such as liquid and

ice). In case of equal symmetries, the transition jump may be bypassed smoothly

(such as fluid water above the critical point). The actual transition process

is typically passing an intermediate metastable state by developing nucleation

and hysteresis phenomena (Schmelzer 2005, 2019, Hellmuth et al. 2020). Phase

transitions of the 2nd kind are continuous and characterised by

the identity of the two phases at the transition point, by the impossibility of

their coexistence and a necessary difference in their symmetries away from the

transition. Because of the latter, transitions of the 2nd kind can

never be circumvented. Infinitely large systems exhibit a sharp transition

point while small, finite systems possess a narrow transition region within

which the microscopic fluctuations between the two phases increase toward the

critical point, where fluctuations become mesoscopic or macroscopically large

or may even diverge mathematically (Hill 1962, Stanley 1971).

Note that the distinction between

those two kinds is not necessarily axiomatically rigorous. The transformation

of homogeneous liquid water into homogeneous ice is a transition of the 1st

kind. But, during the transition from one single phase to the other, a

two-phase composite state may appear, such as ice on a lake. The transition

from a homogeneous single-phase state to an inhomogeneous two-phase state is

breaking the system’s spatial symmetry and may itself be considered as a

transition of the 2nd kind.

In non-equilibrium systems,

transition phenomena qualitatively similar to those at equilibrium may be

observed which are then often termed kinetic phase transitions, bifurcations

or catastrophes. However, there exist various additional new phenomena

such as self-organised criticality (Bak and Chen 1991), multistability

(Ebeling and Schimansky-Geier 1979), strange attractors (Schuster 1984,

Ruelle 1994, Anishchenko et al. 2009) or homoclinic orbits (Shilnikov

1969, Gaspard et al. 1984, Drysdale 1994). From the thermodynamic point of

view, self-organisation may spontaneously create dissipative structures

(Prigogine 1969, Glansdorff and Prigogine 1971, Ebeling 1976, Prigogine and

Stengers 1981, Nicolis and Prigogine 1987), while from the kinetic perspective,

self-organisation is seen as a cooperative phenomenon of synergetics

(Haken 1977, Haken et al. 2016). The numerous degrees of freedom of a

macroscopic system may be classified with respect to their characteristic time

scales. Model parameters that vary on the time scale of interest are order

parameters, those which vary much slower or are externally imposed

constitute control parameters, and finally, the fastest degrees of

freedom may be replaced by their statistically averaged values as functions of

the slower modes, a method known as the quasi-steady-state hypothesis

(Hahn 1974, Haken 1977). Self-organisation is typically indicated by a

qualitative change in the properties of order parameters where the control

parameters pass critical threshold values of a kinetic phase transition.

The transition between whispering

and speaking may serve as just one simple example for a kinetic phase transition

of the 2

nd kind, namely, a so-called

Hopf bifurcation.

Mathematically, the process may be modelled as a friction oscillator (Ebeling

1976). Let

as a control parameter describe

the air flow rate, so that

is the critical value for the

onset of voicing, and

, as the order parameter, be the

amplitude of the vocal cord oscillation, which may build up following the

differential equation

At subcritical conditions,

, the state

is stable and the only steady

state. This state becomes unstable at

, and the new stable state

corresponds to a finite

oscillation amplitude. At the critical point,

, the two regimes coincide at

. The two regimes have different

symmetries as

is time-independent while

represents periodic behaviour of

the vocal cord. A related stochastic model for chemical oscillations (Feistel

and Ebeling 1978a, 1989) demonstrates the significant fluctuation growth near

the transition at

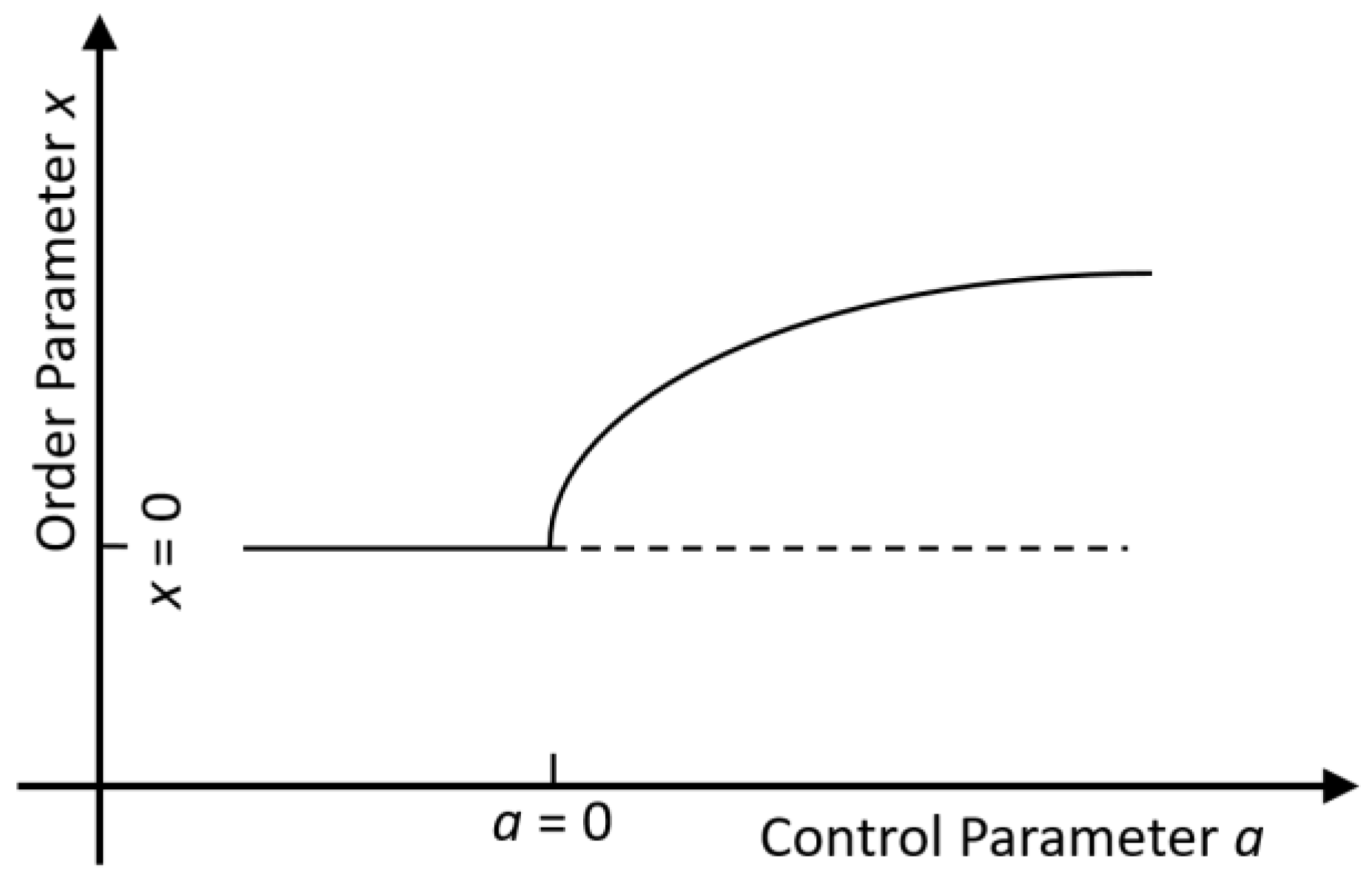

. A bifurcation diagram (

Fig. fA.1) shows the

stationary value of

as a function of

.

Fig. fA.1.

Bifurcation diagram of the model (A.1) for a kinetic phase transition of 2nd kind.

Fig. fA.1.

Bifurcation diagram of the model (A.1) for a kinetic phase transition of 2nd kind.

Prigogine and Wiaume (1946) were

the first to draw attention to the role of irreversible thermodynamics in the

self-organised emergence of macroscopic structures. They found that stable

stationary non-equilibrium states are characterised by least production of

entropy per mass unit and suspected this principle to hold also for living

organisms. It turned out later (Glansdorff and Prigogine 1971, Prigogine et al.

1972, Ebeling 1976), however, that Prigogine’s law of minimum entropy

production is rigorously valid only for linear irreversible thermodynamics

below a critical distance from equilibrium, such as Fourier heat conduction of

a fluid at rest, while the self-organisation of dissipative structures requires

super-critical conditions far from equilibrium, such as thermal convection or

turbulence of a fluid. This thermodynamic theory of dissipative structures

eventually resolved the century-long lingering apparent contradiction between

Clausius’ law of growing entropy and Darwin’s law of improving fitness. This

insight inspired a wealth of further studies regarding self-organisation in

biology and related fields (Eigen 1971, 2013, Romanovsky et al. 1975, Ebeling

and Feistel 1979, 1982, 1994, 2018b, Ebeling and Ulbricht 1986, Ebeling et al.

1990, Feistel and Ebeling 1989, 2011, Haken et al. 2016).

Here, self-organised structures

are certain non-equilibrium attractor states which possess lower entropies than

the associated equilibrium state with the same values of total mass, energy and

volume. According to Clausius’ law, after isolation from the surrounding any

such system will relax spontaneously to equilibrium by producing additional

entropy. Note, however, that entropy of non-equilibrium states is not always

uniformly defined (Gibbs 1902, Planck 1906, 1948a, Shannon and Weaver 1964,

Subarev 1976, Alberti and Uhlmann 1981, Klimontovich 1982, Ebeling 1992, 2017,

Volkenstein 2009, Feistel 2019).

Appendix B. A Model for the Ritualisation Transition to Early Life

The conceptual model very briefly

presented here had originally been developed in 1979 at the Lomonosov Moscow

State University in cooperation with Yuri M. Romanovsky and Vladimir A.

Vasiliev (Feistel et al. 1980), and became first published by Ebeling and

Feistel (1982). The model considers qualitative properties of catalytic networks

rather than biochemical details of certain molecules or reactions. It aims at a

plausible stepwise evolution scenario of minimum complexity from random

catalysis to the emergence of first molecular symbols (Deacon 2021) by the

ritualisation transition. This symmetry-breaking transition may be considered

as the beginning of life (Ebeling and Feistel 1992, 1994, Matsuno 2008, Feistel

and Ebeling 2011, Pattee and Rączaszek-Leonardi 2012).

By definition, symbols do not need

to express their meaning by their own physical structure. For the mutual

connection between structure and meaning, an arbitrary convention must be

implemented physically which is capable of identifying the symbol on the one

hand, and, on the other hand, of expressing the symbol’s meaning by some

physical structure or activity. In real life, t-RNA molecules take this

interpreter role (Rich 1962, Eigen and Winkler-Oswatitsch 1981). All parts of

this complicated machinery need to emerge subsequently within a

self-reproducing catalytic cycle of minimum complexity to represent the very

first life form. Hardly, this may occur in just a few simple steps.

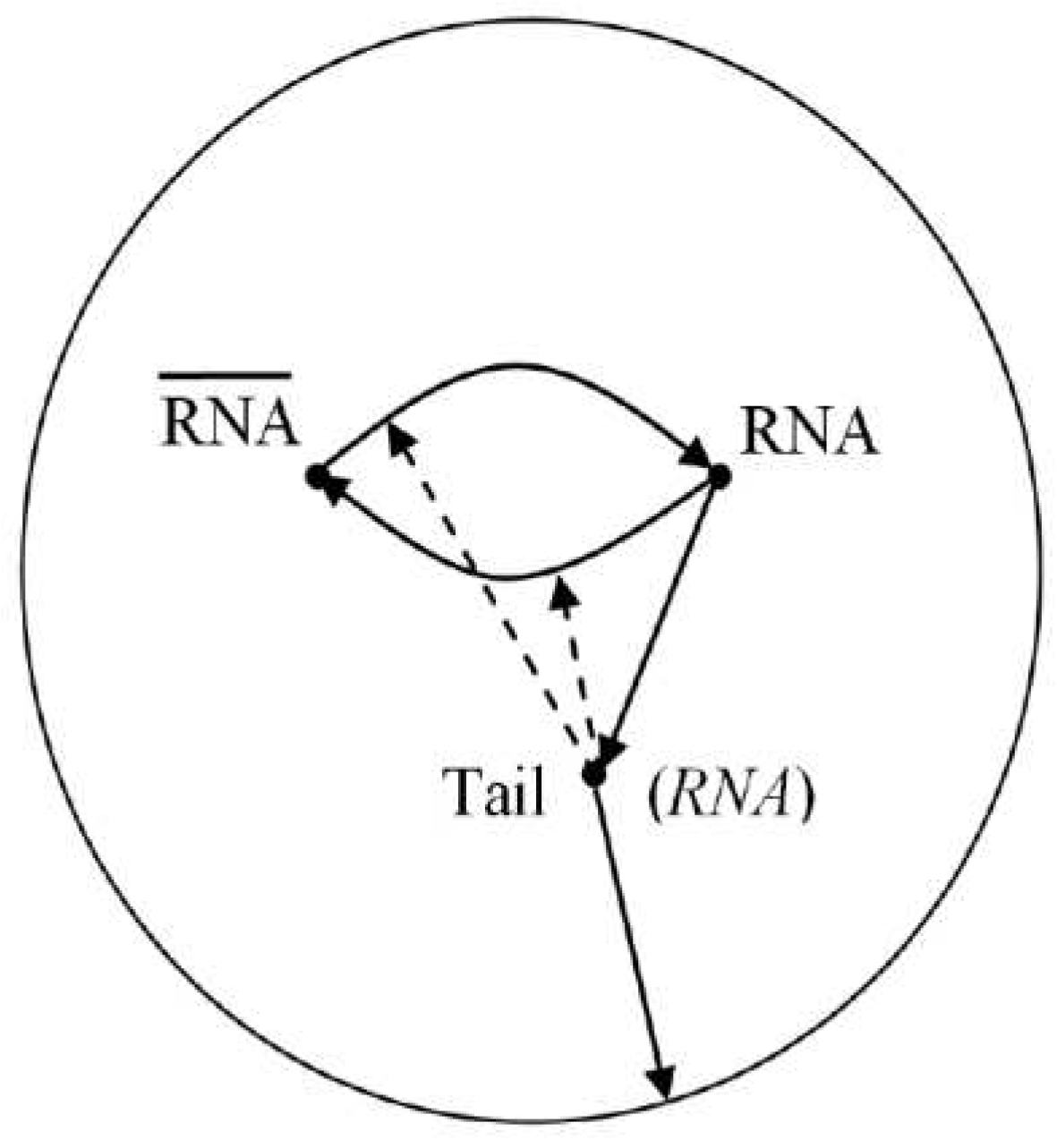

Step 1: Catalytic networks

. The chemical process of catalysis is a non-equilibrium process

accompanied by permanent entropy production. There is no catalysis at

thermodynamic equilibrium. Complex molecules, in particular specific catalysts,

may appear under non-equilibrium conditions in low concentrations. Submarine

hydrothermal vents are preferred candidates as relatively stable sources providing

the required energy over large scales of time and space (Van Dover 2019). Let

be the coordination number of a

directed random graph, expressing the ratio of the number of molecule pairs

with a catalytic link between them, to the total number of molecules regardless

of their mutual interaction. If this network is sparsely occupied (Kaplan

1978), , then the probability for the

occurrence of random cycles of length is proportional to (Austin et al. 1959). Pure

autocatalysis () excluded, binary cycles may have

the highest realistic chance for spontaneous emergence in a “primary soup”

(Feistel 1979, Ebeling and Feistel 1979, 1982, Sonntag et al. 1981, Eigen

2013). Such a hypothetical, initial self-replicating catalytic cluster may be

termed an “RNA-Replicase Cycle” (Ebeling and Feistel 1979), where “RNA” stands

for some chain molecule and “replicase” for a suitable catalyst, self-assembled

under support of the 3D configuration of the same or a complementary RNA

(Gilbert 1986).

Step 2: Spatial compartments

: Due to their nonlinear kinetics, catalytic cycles in homogeneous

solution exhibit once-forever selection (Eigen and Schuster 1977) and cannot

gradually compete and improve in chemical selection processes. The latter may

happen, however, as soon as the central cycle develops “parasitic side chains”

which form certain lipid-like membranes, individual droplets or coacervates

(Ebeling and Feistel 1979, 2018a, Feistel et al. 1980, Feistel 1983, Feistel

and Ebeling 2011). For each such droplet a reproduction rate and a selective

value may be calculated from its internal reaction network. A droplet contains

multiple copies of each molecular species. If the molecules are densely packed,

their stoichiometry will adjust in such way that all species reproduce at the

same rate so that the composition of a growing droplet remains fixed. Large

droplets may split up randomly into equally composed “daughter droplets”.

Darwinian chemical selection may eliminate ineffective individuals. Side chains

do not affect the primary cycle catalytically but enhance its reproduction

indirectly by providing a supporting local environment.

Fig. A.1.

Conceptual model of an RNA-replicase cycle enclosed in a self-assembled coacervate, formed from a “parasitic” tail of the central catalytic loop (Ebeling and Feistel 2018b). (RNA) denotes a catalytically active configuration of the chain molecule RNA. This doplet is imagined as the simplest self-replicating individual entity being subject to molecular Darwinian evolution (Feistel et al. 1980). However, lacking yet any symbolic information processing, this coacervate is still considered as a physico-chemical precursor of the first life form.

Fig. A.1.

Conceptual model of an RNA-replicase cycle enclosed in a self-assembled coacervate, formed from a “parasitic” tail of the central catalytic loop (Ebeling and Feistel 2018b). (RNA) denotes a catalytically active configuration of the chain molecule RNA. This doplet is imagined as the simplest self-replicating individual entity being subject to molecular Darwinian evolution (Feistel et al. 1980). However, lacking yet any symbolic information processing, this coacervate is still considered as a physico-chemical precursor of the first life form.

Step 3: Stoichiometric

diversification

: Error copies occurring in the

reproduction of the central cycle may coexist within the same droplet if the

new cycle is catalytically coupled to the primary cycle, forming a special side

chain. Coexisting cycles offer the possibility of specialising the encoded

catalysts, for example into one supporting the reproduction of the chain (RNA

“transcription”) and a different one supporting the reading of the chain

(“translation” to form the replicase).

Step 4: Building-block assembly

lines

: Different small catalysts present in the

same droplet may self-assembly to larger, more effective catalysts. As an

example, the modern highly effective porphyrine molecule may be imagined as a

composite of four simpler proline amino acids. Such a composed catalyst is

initially translated from separate pieces of chain molecules, but the correct

mounting of pieces may become more precise and effective by concatenating the

responsible chain molecules in the required sequence of mounting. This

procedure demands additional auxiliary catalysts. To produce n final

catalysts, each from m different parts, catalytic support of all immediate

steps would require auxiliary catalysts. This way,

the need for different catalysts would grow faster that the possibilities to

assemble those within the given droplet. A way out is standardisation –

different catalysts may be assembled from a small set of elementary building

blocks but in varying sequences. Accordingly, few elementary, coding chain

molecules (say, “segments”) need to be assembled to longer chain sequences

(say, “strands”), each such sequence responsible for assembling a particular

composite catalyst. Up to this point, we still talk about self-organising

chemical networks, yet at the threshold to proper life.

Step 5: Ritualisation

transition

: Strands with many repeated identical

segments are highly redundant, error-prone and ineffective in the execution of

their catalytic activity. A segment catalysing the assembly of a particular

building block needs to exist only once, and if the same block is required

again, reference to its segment is sufficient rather than full repetition of the

segment. In other words, the production of building blocks may be separated

from mounting them together in a certain sequence. Repeated segments in a

strand may then by reduced to shorter “stenographic” identifiers, to mere

symbols prescribing the way of mounting the blocks. The initial symbol for a

segment is the segment itself, but the symbol may then become arbitrary, and

subsequently, become simplified and diversified. This is a new symmetry,

distinguishing first life, native “biology”, from previous catalytic clusters,

from mere “chemistry”.

Step 6: Code evolution

: Because of their arbitrariness, symbols emerged by ritualisation

are neutral, so-called Goldstone modes with vanishing Lyapunov coefficients, so

that random fluctuations may modify the symbol’s physical structure without

affecting its meaning, and without back-driving forces trying to return to a

previous structure. This property permits neutral drift or “weathering” of the

code. On the other hand, this neutrality after the ritualization transition

preserves details of the evolution history in the physical structure of the

symbols (Feistel 1990, 2017a,b, 2023, Feistel and Ebeling 2011). Analysing its

physical structure, the modern genetic code offers various opportunities for

studies of its likely original form and later development (Woese 1965, Crick

1968, Ebeling and Feistel 1982, Jiménez-Montaño et al. 1996, Béland and Allen

1994, Carter 2008, Jiménez-Montaño 2009, José et al. 2017, Xie 2021, Wills

2023).

Symbolically stored genetic

information constitutes a prediction model

to be

exploited by an organism to ensure its survival and reproduction, provided that

similar external conditions prevail under which this information had been

gathered and stored by surviving and reproducing precursors in the past.

References

- Alberti, P.M., Uhlmann, A. (1981): Dissipative Motion in State Spaces. Teubner, Leipzig.

- Almheiri, A.; Hartman, T.; Maldacena, J.; Shaghoulian, E.; Tajdini, A. Replica wormholes and the entropy of Hawking radiation. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 2020, 1–42,. [CrossRef]

- Anishchenko, V.S., Astakhov, V., Neiman, A., Vadivasova, T., Schimansky-Geier, L. (2009): Nonlinear Dynamics of Chaotic and Stochastic Systems. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Austin, J.L. (1962): How to Do Things with Words. Analysis 23, 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Austin, T.L.; Fagen, R.E.; Penney, W.F.; Riordan, J. The Number of Components in Random Linear Graphs. Ann. Math. Stat. 1959, 30, 747–754,. [CrossRef]

- Bak, P., Chen, K. (1991): Self-Organized Criticality. Scientific American 264, No. 1, 46-53. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24936753.

- Béland, P.; Allen, T. The Origin and Evolution of the Genetic Code. J. Theor. Biol. 1994, 170, 359–365. [CrossRef]

- Born, M. Symbol und Wirklichkeit I: Ein Versuch, auf naturwissenschaftliche Weise zu philosophieren — nicht eine Philosophie der Naturwissenschaften. Phys. J. 1965, 21, 53–63,. [CrossRef]

- Born, M. Symbol und Wirklichkeit II. Phys. J. 1965, 21, 106–108,. [CrossRef]

- Born, M. (1966): Physik im Wandel meiner Zeit. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig.

- Bornholdt, S., Schuster, H.G. (2003): Handbook of Graphs and Networks. Wiley VCH, Weinheim.

- Botton-Amiot, G.; Martinez, P.; Sprecher, S.G. Associative learning in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2220685120. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brillouin, L. (2013): Science and Information Theory. Dover Publications, Mineola, New York.

- Bühler, K. (1965): Sprachtheorie. Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart.

- Butterfield, J. Laws, causation and dynamics at different levels. 2012, 2, 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W. Whence the genetic code?: Thawing the ‘Frozen Accident’. Heredity 2008, 100, 339–340. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav. Brain Sci. 2013, 36, 181–204. [CrossRef]

- Clausius, R. Ueber verschiedene für die Anwendung bequeme Formen der Hauptgleichungen der mechanischen Wärmetheorie.

-