Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Fraction of T. vaginalis cytoskeleton

2.3. Immunofluorescence microscopy

2.4. High-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HR-SEM)

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

2.6. Cluster formation

2.7. Ruthenium Red

2.8. Thiéry technique [12]

2.9. Immunolabeling

2.10. Electron microscopy tomography

2.11. Dye Transfer (or Dye Injection)

3. Results

3.1. The monolayer formation

Extrusion of extracellular vesicles

3.2. Proteins of junctional areas

3.3. Communication between parasites

4. Cluster formation

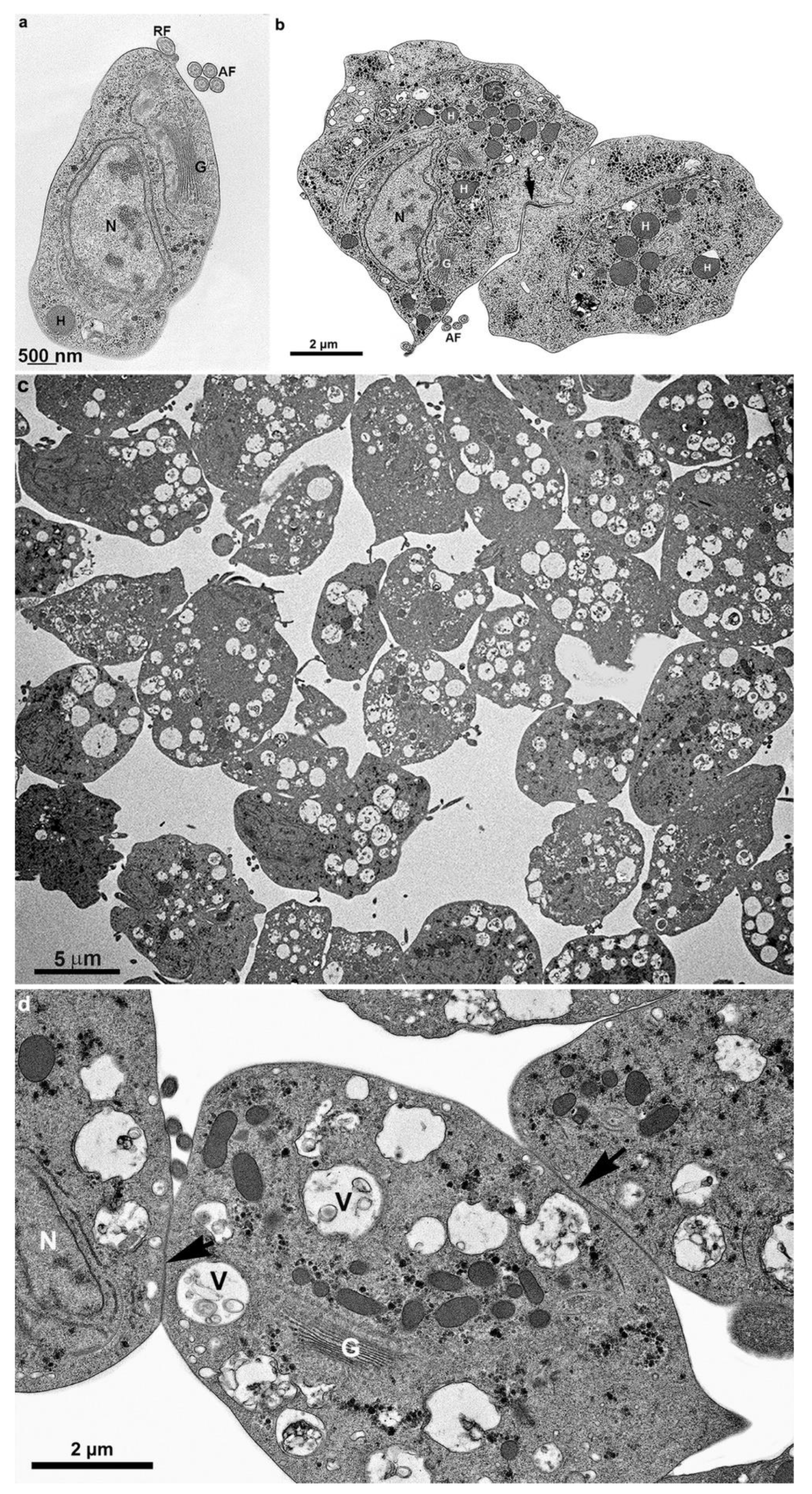

4.1. Transmission electron microscopy- First steps of clumping

Discussion

5.1. Monolayer formation by T. vaginalis

5.2. Clumping

5.3. E-cadherin

5.4. Interdigitations

5.5. Extracellular vesicles

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petrin, D.; Delgaty, K.; Bhatt, R.; Garber, G. Clinical and microbiological aspects of Trichomonas vaginalis. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998, 11, 300-317. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, S.; Giovannucci, E.; Alderete, J.F.; Chang, T.H.; Gaydos, C.A.; Zenilman, J.M.; De Marzo, A.M.; Willett, W.C.; Platz, E.A. Plasma antibodies against Trichomonas vaginalis and subsequent risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006, 15, 939-945. [CrossRef]

- Maritz, J.M.; Land, KM; Carlton, J.M.; Hirt, R.P. What is the importance of zoonotic trichomonads for human health? Trends Parasitol 2014, 30, 333-341. [CrossRef]

- McLaren, L.C.; Davis, L.E.; Healy, G.R.; James, C.G. Isolation of Trichomonas vaginalis from the respiratory tract of infants with respiratory disease. Pediatrics 1983, 71, 888-890.

- Van Der Pol, B.; Kwok, C.; Pierre-Louis, B.; Rinaldi, A.; Salata, R.A.; Chen, P.-L.; van de Wijgert, J.; Mmiro, F.; Mugerwa, R.; Chipato, T.; et al. Trichomonas vaginalis Infection and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Acquisition in African Women. J. Infect Dis 2008, 197, 548-554. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.S. The establishment of various trichomonads of animals and man in axenic cultures. J Parasitol 1957, 43, 488-490.

- Midlej, V.; Benchimol, M. Trichomonas vaginalis kills and eats--evidence for phagocytic activity as a cytopathic effect. Parasitology 2010, 137, 65-76. [CrossRef]

- González-Robles, A.; Lázaro-Haller, A.; Espinosa-Cantellano, M.; Anaya-Velázquez, F.; Martínez-Palomo, A. Trichomonas vaginalis: ultrastructural bases of the cytopathic effect. J Eukaryot Microbiol 1995, 42, 641-651. [CrossRef]

- Pachano, T.; Nievas, YR; Lizarraga, A.; Johnson, P.J.; Strobl-Mazzulla, P.H.; de Miguel, N. Epigenetics regulates transcription and pathogenesis in the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. Cell Microbiol 2017, 19. [CrossRef]

- Coceres, V.M.; Alonso, A.M.; Nievas, Y.R.; Midlej, V.; Frontera, L.; Benchimol, M.; Johnson, P.J.; de Miguel, N. The C-terminal tail of tetraspanin proteins regulates their intracellular distribution in the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. Cell Microbiol 2015, 17, 1217-1229. [CrossRef]

- Molgora, B.M.; Rai, A.K.; Sweredoski, M.J.; Moradian, A.; Hess, S.; Johnson, P.J. A Novel Trichomonas vaginalis Surface Protein Modulates Parasite Attachment via Protein:Host Cell Proteoglycan Interaction. mBio 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.P. Mise en evidence des polysaccharides sur coupes fines en microscopie electronique. J Microsc 1967, 6, 987–1018.

- Srinivas, M.; Costa, M.; Gao, Y.; Fort, A.; Fishman, G.I.; Spray, DC Voltage dependence of macroscopic and unitary currents of gap junction channels formed by mouse connexin50 expressed in rat neuroblastoma cells. J Physiol 1999, 517, 673-689. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Riestra, A.M.; Rai, A.K.; Johnson, P.J. A Novel Cadherin-like Protein Mediates Adherence to and Killing of Host Cells by the Parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. mBio 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.M.; de Miguel, N.; Johnson, P.J. Trichomonas vaginalis: current understanding of host-parasite interactions. Essays Biochem 2011, 51, 161-175. [CrossRef]

- Nievas, YR; Lizarraga, A.; Salas, N.; Cóceres, V.M.; de Miguel, N. Extracellular vesicles released by anaerobic protozoan parasites: Current situation. Cell Microbiol 2020, 22, e13257. [CrossRef]

- Gold, D.; Ofek, I. Adhesion of Trichomonas vaginalis to plastic surfaces: requirement for energy and serum constituents. Parasitology 1992, 105, 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, FC; Elias, C.A.; De Souza, W. Role of divalent cations, pH, cytoskeleton components and surface charge on the adhesion of Trichomonas vaginalis to a polystyrene substrate. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1987, 82, 379-384. [CrossRef]

- Brugerolle, G.; Bricheux, G.; Coffe, G. Actin cytoskeleton demonstration in Trichomonas vaginalis and in other trichomonads. Biol Cell 1996, 88, 29-36. [CrossRef]

- Bastida-Corcuera, F.D.; Okumura, C.Y.; Colocoussi, A.; Johnson, P.J. Trichomonas vaginalis lipophosphoglycan mutants have reduced adherence and cytotoxicity to human ectocervical cells. Eukaryot Cell 2005, 4, 1951-1958. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.M.; Yang, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Chu, C.H.; Tu, T.J.; Wu, Y.T.; Chiang, C.J.; Yang, S.B.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T.; et al. Distinct features of the host-parasite interactions between nonadherent and adherent Trichomonas vaginalis isolates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2023, 17, e0011016. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, O.; Rigo, G.V.; Macedo, A.J.; Tasca, T. Trichomonas vaginalis clinical isolates: cytoadherence and adherence to polystyrene, intrauterine device, and vaginal ring. Parasitol Res 2017, 116, 3275-3284. [CrossRef]

- Salas, N.; Blasco Pedreros, M.; Dos Santos Melo, T.; Maguire, V.G.; Sha, J.; Wohlschlegel, JA; Pereira-Neves, A.; de Miguel, N. Role of cytoneme structures and extracellular vesicles in Trichomonas vaginalis parasite-parasite communication. Elife 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nievas, Y.R.; Vashisht, A.A.; Corvi, M.M.; Metz, S.; Johnson, P.J.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; de Miguel, N. Protein Palmitoylation Plays an Important Role in Trichomonas vaginalis Adherence. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 2229-2241. [CrossRef]

- Aquino, M.F.K.; Hinderfeld, A.S.; Simoes-Barbosa, A. Trichomonas vaginalis. Trends Parasitol 2020, 36, 646-647. [CrossRef]

- Kusdian, G.; Woehle, C.; Martin, W.F.; Gould, S.B. The actin-based machinery of Trichomonas vaginalis mediates flagellate-amoeboid transition and migration across host tissue. Cell Microbiol 2013, 15, 1707-1721. [CrossRef]

- Okumura, C.Y.; Baum, L.G.; Johnson, P.J. Galectin-1 on cervical epithelial cells is a receptor for the sexually transmitted human parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. Cell Microbiol 2008, 10, 2078-2090. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, V.; Baines, A.J. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 1353-1392. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S.R.; Mohler, P.J. Ankyrin protein networks in membrane formation and stabilization. J Cell Mol Med 2009, 13, 4364-4376. [CrossRef]

- Twu, O.; de Miguel, N.; Lustig, G.; Stevens, G.C.; Vashisht, A.A.; Wohlschlegel, JA; Johnson, P.J. Trichomonas vaginalis exosomes deliver cargo to host cells and mediate host∶parasite interactions. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003482. [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Ortiz, L.M.; Barajas-Mendiola, M.A.; Barrios-Rodiles, M.; Castellano, L.E.; Arias-Negrete, S.; Avila, E.E.; Cuéllar-Mata, P. Trichomonas vaginalis exosome-like vesicles modify the cytokine profile and reduce inflammation in parasite-infected mice. Parasite Immunol 2017, 39. [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Johnson, P.J. Trichomonas vaginalis extracellular vesicles are internalized by host cells using proteoglycans and caveolin-dependent endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 21354-21360. [CrossRef]

- Abels, E.R.; Breakefield, X.O. Introduction to Extracellular Vesicles: Biogenesis, RNA Cargo Selection, Content, Release, and Uptake. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2016, 36, 301-312. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).