1. Introduction

The notion that quantum mechanics operates as a probabilistic process can be traced back to the research of Nelson [

1] and has endured over time. However, Nelson's hypotheses ultimately fell short due to the imposition of a particular stochastic derivative with time-inversion symmetry, which limited its generality. Furthermore, the results of Nelson's theory do not entirely align with those of quantum mechanics, as demonstrated by Von Neumann's proof [

2] of the impossibility of reproducing quantum mechanics with theories based on underlying classical probabilistic variables.

The definitive resolution to this question was provided by Kleinert [

3] (refer to Appendix A), who utilized the path integral approach to establish that quantum mechanics can be conceptualized as an imaginary-time probabilistic process. These imaginary-time quantum fluctuations differ from the more commonly understood real-time fluctuations. They result in a "reversible" pseudodiffusion behavior, which is elucidated by the Madelung quantum hydrodynamic model through the action of the quantum potential.

The distinguishing characteristic of quantum pseudodiffusion is the impossibility of defining a positive diffusion coefficient. This leads to a significant implication: the quantum evolution within a spatially distributed system may exhibit local entropy reduction over certain spatial domains and reversible deterministic evolution with recurrence time and overall null entropy variation [

4].

In this study, the author investigates the quantum imaginary-time stochastic process in scenarios where real-time random fluctuations are concurrently in play, leading to irreversible quantum evolution and possibly to decoherence and classical behavior in large-scale systems. The goal of this work is accomplished by extending the Madelung hydrodynamic description of quantum mechanics to its stochastic counterpart.

The primary topics are as follows:

i. Elucidating the formulation of the stochastic quantum hydrodynamic equation of motion as a consequence of fluctuations in spacetime curvature originating from the noisy background of gravitational waves (dark energy).

ii. Exploring the path integral approach to comprehend quantum-stochastic dynamics, which describes the progression of quantum superposition states and potentially their transition to stable configurations.

iii. Describing stationary quantum state configurations in the presence of noise and establishing their correspondence with standard quantum mechanical states.

iv. Defining the circumstances under which the zero-noise “deterministic” limit of the stochastic theory aligns with conventional quantum mechanics.

v. Identifying the criteria that lead to the emergence of classical behavior within extensive-scale systems.

vi. Generalizing the uncertainty principles within the context of fluctuating quantum systems.

vii. Investigating quantum entanglement, wave function decay and measurement process.

viii. Comparing the measurement process as defined by the stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model with the perspectives of decoherence theory and the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics.

ix Supply predictions for Stochastic Quantum Hydrodynamics in a controversial physical case where Quantum Mechanics fails to provide an adequate description such as for deuterium in nuclear mechanics.

x. Examining experiments involving entangled photons within the context of finite time-decay kinetics of wave functions.

xi. Extension of quantum coherence to macroscopic distances to build a system with a large number of Q-bits

2. The quantum potential fluctuations induced by the background of stochastic gravitational waves

With the emergence of evidence for dark energy in the form of a gravitational background, whether of relic origin or due to the dynamics of general relativity bodies, the quantum-hydrodynamic representation offers the possibility of describing the dynamic fluctuations in a system without the need to introduce an external environment. This approach does not introduce divergent results that contradict established theories such as the decoherence theory or the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics; instead, it enhances and complements our understanding of these theories. The noise arising from spacetime curvature ripples can be incorporated into Madelung's quantum hydrodynamic description by leveraging the foundational assumption of relativity, which allows us to consider the energy associated with spacetime curvature as virtual mass.

The Madelung quantum hydrodynamic representation transforms the Schrodinger equation [

5,

6,

7]

for the complex wave function

, into two equations of real variable: the conservation equation for the mass density

and the motion equation for the momentum

,

where

and where

To introduce the presence of the fluctuating virtual mass density due to the spacetime background, we assume the following:

The virtual mass density fluctuations are described by the wave function with density ;

The associated energy density (of the spacetime background fluctuations) is proportional to ;

The virtual mass is defined by the identity

The virtual mass is approximately assumed to not interact with the mass of the physical system (since the gravitational interaction is sufficiently weak to be disregarded).

In this case, the wave function of the overall system

reads

Moreover, by assuming that the virtual mass

of the is much smaller than the mass of the system (i.e.,

), the overall quantum potential (2.4) reads

Moreover, given the vacuum mass density noise of wavelength

associated with the virtual mass fluctuation wave function

it follows that the quantum potential energy fluctuations read

Following the procedure described in reference [

8] the energy fluctuation reads

that for the three-dimensional case, leads to

The result (2.11) shows that the energy, due to the mass density fluctuations of the vacuum, increases as the inverse squared of . Therefore, quantum potential fluctuations of very short wavelengths (i.e., ) can lead to unlimited large energy fluctuations even for vanishing noise amplitudes . This fact could prevent the realization of the deterministic, zero noise, limit (2.2-4) representing quantum mechanics.

On the other hand, the convergence to the deterministic limit (2.2-4) of quantum mechanics for is warranted by the fact that uncorrelated fluctuations on shorter and shorter distances are energetically unlikely. Therefore, the requirement of convergence to conventional quantum mechanics for implies a supplemental condition on the spatial correlation function of the noise as .

The derivation of the shape of the spatial correlation function of noise, which we name

, is a heavy stochastic calculation [

9]. A simpler and more straightforward way to calculate

is obtained by considering the spectrum of the fluctuations.

As shown in ref. [

8] the spectrum

of the spatial frequency reads

showing that the spectrum is not white, and the components with wave-length

smaller than

go quickly to zero. From (2.12), the spatial shape

reads

where

is the De Broglie length.

The expression (2.13) shows that uncorrelated mass density fluctuations on shorter and shorter distances are progressively suppressed by the quantum potential, allowing the realization of the conventional “deterministic” quantum mechanics for systems whose physical length is much smaller than the De Broglie one .

For the sufficiently general case to be of practical interest, where the mass density noise correlation function can be assumed to be Gaussian with null correlation time, isotropic into the space and independent among different coordinates, it can be assumed of the form

that, for a system whose physical length

is much smaller than that of De Broglie (i.e.,

), reads

On this ansatz, equation (2.3) assumes the stochastic form [

10] (see appendix B)

where [8, 10]

where

is a pure not zero number [

10].

It is worth noting that the probability mass density (PMD) function is now defined by the Smolukowski conservation equation stemming from (2.17) and obeys the condition since by (2.13-14), convergence to quantum mechanics is warranted.

The gravitational dark energy introduces the concept of a self-fluctuating system where the noise is an intrinsic property that does not require the presence of an environment.

3. The Langevin-Schrodinger equation from stochastic Madelung quantum hydrodynamics

Langevin equations, typically employed to describe underlying dynamics, can be derived using various techniques, including the Poisson transformation [

11] and the Fock space formalism [

12]. Exact formulations occasionally exist for nonlinear reaction kinetics and a few other problems. Alternatively, a Langevin equation can be adopted from a phenomenological perspective, where the approximated dynamics are determined a priori. In this context, achieving a rigorous Langevin description can be quite challenging.

In our current study, we have the advantage of employing an exact microscopic quantum mechanical model.

Generally, assuming for the stochastic case, the complex field

where

obeys the Smolukowski conservation equation [8, 13] that, close to the deterministic limit of the Madelung (i.e., quantum mechanics) representation for

and

, reads

where the diffusional dissipation

is detailed in ref [

8]. Moreover, for

of quantum mechanics,; it follows that the quantum-hydrodynamic equations (2.2-4) reads

leading to the partial stochastic differential equation

that with the help of (3.2) rearranged in the form

leads to the generalized Langevin-Schrodinger equation (GLSE) that for time-independent systems reads

Although within the frame of the stochastic quantum hydrodynamic description, quantum mechanics serves as the deterministic limit of the theory with no dissipation, it is interesting to analyze the case when, approaching the zero noise limit, dissipation is still present.

Close to the zero-noise condition, it is possible to characterize the ability of the system to dissipate by the semiempirical parameter

defined by the relation [

10]

. On this ansatz, (3.6) reads

from which we can see that the realization of quantum mechanics is warranted (see Equation (2.17)) by the condition . In this case, it can be readily seen that the GLSE (3.6) reduces to the Schrodinger equation.

When physical dissipation is significant at the quantum level, the parameter

remains quite high close to the quantum limit, such as

In this case, it is straightforward to see that equation (3.6) converges to quantum Brownian motion. In fact, under condition (3.8) and by utilizing dimensional considerations, the following identities apply:

Thus, by (3.10-11) being

, the term

can be disregarded in (3.6), and close to the deterministic limit (i.e.,

), it follows the conventional Langevin equation for quantum Brownian motion

The derivation of the Schrödinger-Langevin equation from the stochastic generalization of the quantum hydrodynamic model is noteworthy as it demonstrates a correct correspondence with conventional quantum mechanical physics.

4. The quantum path integral motion equation in the presence of stochastic noise

The Markov process (2.17) obeys the Smolukowski integro-differential equation for the Markov probability transition function (PTF) [

13]

where the PTF

represents the probability that a quantity of the probability mass density (PMD)

at instant t in time interval τ at point z is transferred to point q [

13].

The conservation of the PMD

in integral form shows that the PTF generates the displacement of a vector (q,t) – (z,0) according to the rule [

13]

Generally, for the quantum case, equation (4.1) cannot be reduced to a Fokker-Planck equation (FPE) since the quantum potential

has a functional dependence on

and the PTF

is non-Gaussian (see

Appendix C).

Nonetheless, if the initial distribution

is stationary (e.g., quantum eigenstate) and is close to the long-term final stationary distribution

of the stochastic case, it is possible to assume that the quantum potential is constant in time as a Hamilton potential following the approximation

In this case, the quantum potential is fixed and independent of the wave function, the PMD

the stationary long-time solution is given by the Fokker-Plank equation

leading to the final equilibrium of the stationary quantum configuration

In

Appendix D , the stationary states of harmonic oscillator obeying (4.6) are shown. The results show that the quantum egenstates are stable and maintain their shape (with a small change in their variance) when subject to fluctuations.

4.1. Evolution of quantum superposition of states submitted to stochastic noise

To determine the evolution of quantum superposition of states that are not stationary (not considering fast kinetics and jumps), we have to integrate the stochastic differential equation (2.17) that eliminates fast variables reads

As shown below, this can be done by using the discrete approach with the help of both the Smolukowski integro-differential equation (4.1) and the associated conservation equation (4.2) for the PMD .

We integrate the SDE (4.7) by using its 2nd-order discrete expansion

where

where

has a Gaussian zero mean and unitary variance whose probability function

, for

, reads

where the midpoint approximation has been introduced

and where

and

are the solutions of the deterministic problem:

As shown in ref. [

8], the PTF

can be achieved after successive “u” steps of approximation and reads

and the PMD at the

-th instant reads

leading to the velocity field

Moreover, the continuous PTF reads

where.

The general solution, given in the recursive formula (4.20), has the advantage that can be also applied to a nonlinear system that cannot be treated by standard approaches [14-17].

4.2. General features of relaxation of quantum superposition of states

In the classical case, the Brownian process described by the FPE admits the stationary long-time solution

where

leading to the canonical expression [

3]

Generally, in the quantum case (4.20), cannot be given in a closed form (4.21) since it depends on the specific relaxation path of the system toward the steady state, which significantly depends on the initial conditions , and, therefore, on the initial time when the quantum superposition of states is submitted to fluctuations.

In addition, from (4.8), we can see that depends on the exact sequence of inputs of stochastic noise since, in classically chaotic systems, very small differences can lead to relevant divergences of the trajectories in a short time. Thus, in principle, different long-period stationary configurations (i.e., eigenstates) can be reached whenever starting from identical superposition of states. Therefore, in classically chaotic systems, Born’s rule can also be applied to the measurement of a single quantum state.

Even if , it is worth noting that to have finite quantum lengths and (necessary to have the quantum-stochastic dynamics of Equation (4.7) and the quantum decoupled (classical) environment or measuring apparatus), the nonlinearity of the system-environment interaction is necessary: Quantum decoherence, leading to the decay of superposition states, is significantly promoted by the widespread classical chaotic behavior observed in real systems

On the other hand, a perfect linear universal system would maintain quantum correlations on a global scale and would never allow the quantum decoupling between the system and the measuring apparatus necessary for the measurement process (see § 4.8). It should be noted that even the quantum decoupling of the system from the environment would be impossible, as quantum systems function as a unified whole. Merely assuming the existence of separate systems and environments subtly introduces a classical condition into the nature of the overall supersystem.

Furthermore, since the connection (B.11) between the PMD and the MDD holds only at the leading order of approximation of (i.e., slow relaxation process and small amplitude of fluctuations), in the case of a large fluctuation (that can occur on a time scale much longer than the relaxation one), can make transitions not described by (4.20), even from a stationary eigenstate to a generic superposition of states. In this case, a new relaxation toward different stationary eigenstates will follow: The PMD (4.18) describes the relaxation process occurring in the time interval between two large fluctuations, rather than the entire evolution of the system toward a statistical mixture. Because of the long time scale of these jumping processes, a system composed of a large number of particles (or independent subsystems) gradually relaxes towards a statistical mixture, with its distribution determined by the temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient.

5. Emerging classical mechanics on large size systems

If the quantum potential is canceled by hand in the quantum hydrodynamic equations of motion (2.1-3), the classical equation of motion emerges [

7]. Even if this is true, this operation is not mathematically correct since it changes the characteristics of the quantum hydrodynamic equations. In fact, doing so, the stationary configurations (i.e., eigenstates) are wiped out because we cancel the balancing force of the quantum potential against the Hamiltonian one [

18] that establishes the stationary condition. Therefore, an even small quantum potential cannot be neglected in the deterministic quantum hydrodynamic model (2.2-2.4).

Conversely, in the stochastic generalization, it is possible to correctly neglect the quantum potential in (2.17, 4.7) when its force is much smaller than the force noise

such as

that by (4.7) leads to

and hence, in a coarse-grained description with elemental cell side

, to

where is the physical system length.

In addition, even if the noise

has a zero mean, the mean of the quantum potential fluctuations

is not null, so the dissipative force

in (6.22) appears. Therefore, the stochastic sequence of inputs of noise alters the coherent evolution of the quantum superposition of state. Moreover, by observing that the stochastic noise

grows with the size of the system, for macroscopic systems (i.e.,

), condition (5.01) is satisfied if

Actually, to have a large-scale description, completely free from quantum correlations, we can more strictly require

Thus, by observing that for linear systems

it straight follows that they cannot lead to the macroscopic classical phase.

Generally, the stronger the Hamiltonian potential is, the higher the wave function localization and the larger the quantum potential behavior at infinity. This can be easily proven by observing that given the MDD

where is a polynomial of order k. To have a finite quantum potential range of interaction, it must result in . Therefore, linear systems, with , have an infinite range of action of quantum potential.

A physical example comes from solids owning a quantum lattice. If we look at phenomena on intermolecular distance where the interaction is linear, the behavior is quantum (e.g., the X-ray diffraction), but if we look at macroscopic properties since the Lennard-Jones potential goes to zero to infinity and the quantum range of interaction is finite (see § 5.1), the classical behavior can emerge since (e.g., low-frequency acoustic wave whose wavelength is much larger than the linear range of interatomic distance).

For instance, for gas phases with particles that interact by the Lennard-Jones potential, whose long-distance wave function reads [

19]

the quantum potential reads

leading to the quantum force

so that by (5.01, 5.05), the large-scale classical behavior can appear [20-21] in a sufficiently rarefied phase.

It is interesting to note that in (5.09), the quantum potential is at the basis of the hard sphere potential of the “pseudo potential Hamiltonian model” of the Gross-Pitaevskii equation [22-23],

where is the boson-boson s-wave scattering length.

By observing that, to fulfill condition (5.05), we can sufficiently require that

so that it is possible to define the quantum potential range of interaction

as [20-21]

which gives a measure of the physical length of the quantum non-local interactions.

For L-J potentials, the convergence of the integral (5.11) for

is warranted since, at short distances, the L-J interaction is linear (i.e.,

) and

5.1. Lindemann Constant for Quantum Lattice-to-Classical Fluid Transition

For a system of Lennard-Jones interacting particles, the quantum potential range of interaction

reads

where is the distance up to which the interatomic force is approximately linear () and where is the atomic equilibrium distance.

An experimental confirmation of the physical relevance of the quantum potential length of interaction comes from the quantum to classical transition in a crystalline solid at the melting point when the system passes from a quantum lattice to a fluid amorphous classical phase.

Assuming that, in the quantum lattice, the atomic wave function (around the equilibrium distance ) spans itself less than the quantum coherence distance, it follows that at the melting point, its variance equals .

On these assumptions, the Lindemann constant

[

24] reads

, and it can be theoretically calculated since

that, being typically

and

, leads to

A more accurate evaluation, making use of the potential well approximation for the molecular interaction [20-21], leads to

and to the value of

for the Lindemann constant that agrees well with the measured values, ranging between 0,2 and 0,25 [

24].

5.2. Fluid-superfluid transition

Since the De Broglie distance

is a function of temperature, its influence on the fluid-superfluid transition in monomolecular liquids at very low temperature, such as for

, can be detected. The treatment of this case is detailed in ref. [20-21], where, for the

-

interaction, the potential well is assumed to be

where

is the Lennard-Jones potential depth, where

and where

is the mean

-

atomic distance.

By posing that at superfluid transition, the de Broglie length reaches the

-

atomic distance and reads

We have, for

, that the ratio of superfluid/normal

density is approximately null, while for

we have almost 100% superfluid

. Therefore, at the condition

When the superfluid/normal

density ratio is 50%, it follows that the temperature

, for the

mass of

, reads

which agrees well with the experimental data in ref. [

25] of approximately

.

On the other hand, since by (5.20) for

all the couples of

fall into the quantum state, the superfluid ratio of 100% is reached at the temperature

well agreeing with the experimental data in ref. [

25] of approximately

.

Moreover, by utilizing the superfluid ratio of 38% at the

-point of

, the transition temperature

reads

in good agreement with the measured

superfluid transition temperature of

.

As a final remark, it is worth noting that there are two ways to establish quantum macroscopic behavior. One approach involves lowering the temperature, which effectively increases the de Broglie length. The second approach is to enhance the strength of the Hamiltonian interaction among the particles within the system.

As far as it concerns the latter, it is important to note that the limited strength of the Hamiltonian interaction over long distances is the key factor that allows classical behavior to manifest. When we examine systems governed by a quadratic or stronger Hamiltonian potential, the range of interaction associated with the quantum potential becomes infinite, as illustrated in equation (5.44); consequently, achieving a classical phase becomes unattainable, regardless of the system's size being .

In this particular scenario, we exclusively observe the complete manifestation of classical behavior on a macroscopic scale within systems featuring interactions that are sufficiently weak, weaker even than linear interactions, which are classically chaotic. In this case, the quantum potential lacks the ability to exert its nonlocal influence over extensive distances.

Therefore, classical mechanics emerges as a decoherent outcome of quantum mechanics when there is fluctuating spacetime at play.

5.3. The coarse-grained approach

Given the PMD current

, that reads

The macroscopic behavior can be obtained by the discrete coarse-grained spatial description of (5.25), with the local cell of side

, which as a function of the j-th cell reads [

26]

where

where is the spatial correlation length of the noise, where the terms, , and are matrices of coefficients corresponding to the discrete approximation of the derivatives at the j-th point.

Generally, the quantum potential interaction stemming by the k-th cell depends on the strength of the Hamiltonian potential .

By setting, in a system of a huge number of particles, the side length equal to the mean intermolecular distance, we can have the classical rarefied phase if is much larger than the quantum potential length of interaction(that by (5.12)) is also a function of the De Broglie length).

Typically, the Lennard-Jones potential (5.10) leads to

so that the interaction of the quantum potential (stemming by the k-th cell) into the adjacent cells is null and

is diagonal. Thus, the quantum effects are confined to each single-molecule cell domain.

Furthermore, for classical systems it follows that the spatial correlation length of the noise reads and the fluctuations appear spatially uncorrelated in the macroscopic systems

Conversely, given that for stronger than linearly interacting systems and the quantum potential of each cell extends its interaction to the other ones, the quantum character appears on the coarse-grained description.

As shown in §5.2, by using the stochastic hydrodynamic model (SQHM), it is possible to derive descriptions for dense phases where quantum effects appear on the macroscopic scale.

5.4. Measurement process and the finite range of nonlocal quantum potential interactions

Throughout the process of measurement, consisting of a “deterministic” conventional quantum interaction between the sensing component of the experimental setup and the system being measured, the interaction ceases when the measuring apparatus is moved to a significant distance away from the system, well beyond the distances and .

The interpretation and handling of the "interaction output" are subsequently managed by the measuring apparatus, typically involving a classical, irreversible procedure characterized by a clear arrow of time. This procedure ultimately yields the macroscopic measurement result.

Nonetheless, the phenomenon of decoherence plays a pivotal role in the measurement process. It allows for the emergence of a large-scale classical framework that ensures genuine quantum isolation between the measuring apparatus and the system, both before and after the measurement event.

This quantum-isolated state, both initially and finally, is essential for determining the conclusion of the measurement and for gathering statistical data from a set of independent repeated measurements.

It is worth emphasizing that within the framework of the stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model (SQHM), the standard condition of moving the measured system to an infinite distance before and after the measurement is not sufficient to guarantee the independence of the system and the measuring apparatus if either or.

5.5. Minimum measurement uncertainty of quantum systems in fluctuating spacetime background

Any quantum theory that is capable of describing the evolution of a physical system at any order of magnitude of its size must necessarily explain how the properties of quantum mechanics transform into the emergent classical behavior at larger scales.

The most distinctive laws of the two descriptions are the minimum uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics and the finite speed of propagation of interactions and information in local classical relativistic mechanics.

If at a certain distance

, which is smaller than

, a system fully conforms to the "deterministic" conventional quantum mechanical evolution such that its subparts do not have a distinct identity, then in order for the observer to obtain information about the system, it must be at least as far apart from the observed system (both before and after the process) as the distance

(see

Appendix E). Thus, due to the finite speed of propagation of interactions and information, the process cannot be performed in a time shorter than

Moreover, given the Gaussian noise (2.18) (with the diffusion coefficient proportional to

), we have that the mean value of the energy fluctuation is

for the degree of freedom. Therefore, a nonrelativistic (

) scalar structureless particle of mass m has an energy variance

from which it follows that

It is worth noting that the product is constant since the growth of the energy variance with the square root of exactly compensates for the equal decrease in the minimum acquisition time.

The same result is achieved if we derive the uncertainty relations between the position and momentum of a particle of mass m. If we acquire information about the spatial position of a particle with a precision

the variance

of its relativistic momentum

due to the fluctuations reads

and the uncertainty relation reads

Equating (5.38) to the uncertainty value, such as

it follows that , which represents the physical length below which the quantum entanglement is fully effective and the minimum (initial and final) distance between the system and the measuring apparatus.

As far as it concerns the theoretical minimum uncertainty of quantum mechanics, obtainable from the minimum uncertainty (5.35, 5.38) in the limit of zero noise, we observe that the quantum deterministic behavior (with

) in the low velocity limit (i.e.,

) leads to the equalities

remain finite and constitutes the minimum uncertainty of the quantum deterministic limit.

It is interesting to note that in the relativistic limit, due to the finite light speed, the minimum acquisition time of information in the quantum limit reads

The output (5.47) shows that it is not possible to carry out any measurement in the deterministic fully quantum mechanical global system since its duration is infinite.

Moreover, if we localize the system in a domain of physical length , we can satisfy the choice (5.36) by increasing the temperature, and since the minimum uncertainty is independent of the temperature, it follows that the minimum uncertainty relation (5.46) generally holds.

Since non-locality is confined in domains of physical length of order of and information about a quantum system cannot be transferred faster than the light speed (otherwise, the uncertainty principle is violated), the local realism is established on the coarse-grained macroscopic physics (where the domains of order of reduces to a point), while the paradox of the “spooky action at a distance” is limited on microscopic distance (smaller than ) where the quantum mechanics fully realize itself.

It must be noted that for the low-velocity limit of quantum mechanics, the conditions and are implicitly assumed into the theory and lead to (apparent) instantaneous transmission of interaction at a distance.

It is also noteworthy that in the presence of noise, the measure indeterminacy has a relativistic correction since

leading to the minimum uncertainty in a quantum system submitted to gravitational background noise (

)

that can become important for light particles (with ) but that for the conventional quantum mechanics for leaves the uncertainty relations unchanged.

5.6. The stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model and the decoherence theory

In the context of the SQHM, to perform statistically reproducible measurement processes and to warrant that the measuring apparatus is fully independent of the measured system (free of quantum potential coupling before and after the measurement), it is necessary to have a global system with a finite length of quantum potential interaction.

In such a case, the SQHM indicates that due to the finite speed of transmission of light and information, it is possible to carry out the measurement within a finite time interval. Therefore, a finite length of quantum potential interaction and the resulting decoherence are necessary preconditions for carrying out the measurement process.

The decoherence theory [27-32] does not attempt to explain the problem of measurement and the collapse of the wave function. Instead, it provides an explanation for the transition of the system to the statistical mixture of states generated by quantum entanglement leakage with the environment. Moreover, while the decoherence process may take a long time for a microscopic system, the decoherence time for macroscopic systems, consisting of n microscopic quantum elements, can be very short. However, in the context of decoherence theory, the superposition of states of the global universal wave function still exists (and remains globally coherent).

This conundrum can be logically resolved using the solution proposed by Poincaré, which has recently been extended to quantum systems [

33]. This solution demonstrates that irreversible phenomena can occur in a globally reversible system since recurrence occurs over a very long time interval (much longer than the lifetime of the universe). The global quantum system locally mimics the classical behavior in a way that is indistinguishable from that of the large-scale classic universe. This is because the recurrence time is much larger than the lifetime of the universe. For example, the recurrence time provided by Boltzmann for a single cubic centimeter of gas to return to its initial state has the order of many trillions of digits, while the universe time has thirteen digits.

In the context of Madelung's approach, the Wigner distribution and the quantum hydrodynamic theory are closely connected and do not contradict each other [

7]. However, the interpretation of the global system as classical or quantum in nature is ultimately a matter of interpretation. Essentially, we cannot determine whether the noise from the environment is truly random or pseudorandom. In computer simulations, it is widely accepted that any algorithm generating noise will actually produce pseudo-random outputs, but this distinction is not critical when describing irreversible phenomena.

The theory of decoherence can explain macroscopic behavior as a result of dissipative quantum dynamics, but it cannot determine the conditions that allow for a truly classical global system. On the other hand, the SQHM approach provides a criterion for the transition from quantum dynamics to classical dynamics at an appropriate macroscopic scale without the need for an external environment. In addition, the possibility is shown by the SQHM of having a classical global system in a self-fluctuating space-time whose background curvature fluctuations are compatible with the quantum-gravitational description of the universe, where gravity is considered a source of global decoherence [34-35].

From a conceptual standpoint, the SQHM theory addresses the problematic issue of spontaneous entropy reduction in the global quantum reversible system, which is necessary for the system to return to its initial state as required by the recurrence theorem. Furthermore, since quantum pseudo-diffusion evolution [

36] shows that entropic and anti-entropic processes occur simultaneously in different regions of a quantum system, the question of why spontaneous anti-entropic processes are not observed anywhere and at any time in the universe remains unsolved in the context of decoherence theory.

In relation to this aspect, it is important to clarify that when the size of the environment is increased to infinity, the recurrence time is pushed beyond infinity. This can be easily demonstrated by examining what are known as free Gaussian coherent states. These states are obtained as the limit of eigenstates of harmonic oscillators when the quadratic coefficient of the potential approaches zero, which is equivalent to increasing the size of the system to infinity.

While we can observe the emergence of antientropic behavior in the harmonic Gaussian states after half of the oscillating period time has passed, this behavior is never observed in the coherent states because their period of oscillation extends to infinity. Consequently, the expansion of the environment to infinity is a tricky mathematical procedure that eliminates the unavoidable antientropic behavior of conventional (deterministic) quantum mechanics, which contradicts physical evidence.

5.7. The stochastic quantum hydrodynamic theory and the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics

The path-integral solution of the SQHM (4.33-35) is not general but holds in the small noise limit before a large fluctuation occurs. It describes the “microscopic stage” of the decoherence process at the De Broglie physical length scale.

Moreover, the SQHM parametrizes the quantum to classical transition by using two physical lengths, and , addressing quantum mechanics as the asymptotic behavior for . Therefore, it furnishes additional insight into the measurement process.

Even if the measurement process can be asymptotically treated as a quantum interaction between the system and the measurement apparatus, marginal decoherence effects exist for its realization due to:

real decoupling at the initial and final state of the measure between the system and the measuring apparatus,

utilization of classical equipment for experimental management, collection and treatment of the information.

The marginal decoherence is ignored or disregarded because the classical equipment is mistakenly assumed to be decoupled at infinity, while the assumption of perfect global quantum interaction (which extends itself at infinity, such as and ) does not allow the realization of such conditions.

To describe the decoherence during the external interaction

, the SQHM reads

In principle, the marginal decoherence, with characteristic time , may affect the measurement if is comparable with the measure duration time (the absence of marginal effects is included in the treatment as the particular case of sufficiently fast measurement with ).

From the general point of view, the SQHM shows that the steady state after relaxation depends on its initial configuration.

at moment , allowing the system to possibly reach any eigenstate of the superposition.

Given that the quantum superposition of energy eigenstates possesses a cyclic evolution, with recurrence time

, the probability of relaxation to the i-th energy eigenstate for the SQHM model can read

where is the number of time intervals centered around the time instants (with and ) in which the system is initially submitted to fluctuations, and is the number of times the i-th energy eigenstate is reached in the final steady state.

Moreover, since the eigenstates are stable and stationary, it also follows that the transition probability between the k-th and the i-th eigenstates reads

Since the finite quantum lengths and , allowing quantum decoupling between the system and the measuring apparatus, necessarily implies “marginal decoherence”, it follows that the output of the measure is produced in a finite time lapse (larger than of (5.33)) due to the wave function decay time.

As far as it concerns the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, the measurement is a process that produces the wave function collapse, and the outcome (e.g., the energy value

for the state (5.52)) is described by the transition probability that reads

that for the i-th eigenstate reads

To analyze the interconnection between the wavefunction decay and the wavefunction collapse, we assume, as a starting point, that they are different phenomena and have independent realization.

In the first instance, we can assume that the wavefunction decay (with characteristic time

) occurs first and then the wavefunction collapses (with characteristic time

) during the measurement process. Without loss of generality, we can assume

, and therefore, in this case, it follows that

On the other hand, for the Copenhagen interpretation, the measure on a quantum state with

, by (5.55-7) it follows that

The outputs (5.57-8) show that the wavefunction collapse beyond the duration of the wavefunction decay is ineffective for the output of the measure. Furthermore, we can infer that, since after the wavefunction decays, the system has already reached its final steady eigenstate, the wavefunction collapse does not occur at all since it does not affect the eigenstates.

Therefore, we can shorten the measure duration

up to the wavefunction decay time

without changing the result (5.57) for the measure, leading to the relation

On the other hand, by considering in the second instance that the wavefunction collapse

is much shorter than the wavefunction decoherence, such as

(i.e.,

), the final output reads

showing that the wave function decay, due to the marginal quantum decoherence, does not affect the measure even if it might proceed beyond the wave function collapse. More precisely, we can affirm that since the wavefunction decay does not affect the eigenstates, it does not occur at all after the wavefunction collapse.

Therefore, both the wavefunction collapse and the wavefunction decoherence occur together only during the time of the measure

. In the case of (5.60), we might shorten the measure duration time

to

so that, as the wavefunctin decay finished at the end of the measure, identity (5.53,5.60) also leads to

The proof of (5.61) can be validated by the numerical output of the motion equation (4.7).

The SQHM through identity (5.61) furnishes the linkage between the wave function collapse and the wave function decay generated by the marginal decoherence, possibly showing that they are the same phenomenon.

6. Stochastic Quantum Hydrodynamics corrections to wrong Quantum Mechanics outputs in the Nuclear Mechanics of Deuterium

In the preceding discussion, the Stochastic Quantum Hydrodynamic Model (SQHM) has been demonstrated to largely align with the outcomes of quantum mechanics, specifically encompassing the realms of decoherence theory and the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. Furthermore, the SQHM presents a holistic perspective in which quantum mechanics and classical mechanics can coexist simultaneously. Notably, the SQHM constructs a comprehensive theoretical framework in which intrinsic system fluctuations are self-contained and do not necessitate the presence of an external environment.

However, an intriguing avenue of inquiry is whether the SQHM offers substantive advancements in resolving issues that conventional quantum mechanics struggles with or reveals certain limitations. This is exemplified in the context of deuterium states observed in nuclear dynamics, where the empirical physical state deviates from the predictions of standard quantum mechanics. This experimental anomaly introduces profound conceptual challenges, often attributed to the ambiguous notion of the existence of hidden variables within quantum mechanics. In reality, this situation engenders more complexity than it provides a definitive solution.

In fact, one of the unresolved facets of quantum theory pertains to the hidden variable approach. On the one hand, the hidden variable approach proposed by Bohm [

37] falls within the realm of theoretical frameworks, akin to that of Nelson [

1], where an attempt is made to replicate the outcomes of quantum mechanics by introducing a form of indeterminacy or hidden variable into classical theory; on the other hand, Von Neumann's proof [

2] and Bell's theorem [

38] unequivocally assert the impossibility of hidden variables replicating quantum mechanics, effectively forbidding the validity of such an approach. However, complicating the situation, Santilli has recently revitalized interest in and the potential validity of the hidden variable hypothesis with his IsoRedShift Mechanics theory [

39], which is predicated on introducing a hidden variable to elucidate deviations in nuclear quantum mechanics in the deuterium state. It is worth noting, for precision's sake, that Santilli's hidden variable is integrated into quantum theory but not into classical theory; as such, it can be more accurately regarded as a semiempirical perturbative parameter rather than a traditional hidden variable. Regarding this matter, the author has recently demonstrated in a paper [

40] that the perturbations in quantum mechanical behavior described by the semiempirical parameter introduced by Santilli IsoRedShift Mechanics can actually be attributed to perturbations in quantum mechanics stemming from stochastic fluctuations, a phenomenon well elucidated within the framework of the SQHM.

6.1. The stochastic quantum hydrodynamic equation for charged particles with spin

For charged particles with spin, the Schrodinger equation [

7] leads to Pauli’s equation

where

where the probability density of the magnetic moment is identified by the vector

leading to the quantum hydrodynamic equations [

7]

For the stochastic problem, the deterministic variables transform into the corresponding probabilistic distributions following the association

and

In the deterministic limit, when

, since the noise correlation function (2.15-2.16) warrants convergence to quantum mechanics, we have

and for the stationary eigenstates (i.e.,

and

),

where

stands for the mean value.

Therefore, the difference between the pseudo potential of the deterministic spin motion equation (6.8),

and its stochastic counterpart

, at first order as a function of

and

(close to the deterministic limit and near stationary condition (6.12)), can be developed in series expansion as

Moreover, by generally posing

since from (6.12)

so that

the stochastic spin motion equation (6.8) reads

Furthermore, if we consider the more simplified situation of stationary mass density distribution with only spin wave noisy oscillations, equation (6.18) reduces to

6.2. The quantum hydrodynamic equation with iso-spin matrices

By utilizing the iso-matrices [

39] in the form

where

the iso-spin versor

of the Madelung quantum hydrodynamic description reads

and the spin motion equation (6.8, 6.14) reads

By comparing (6.18) with (6.25)

This describes how the iso-spin matrices are linked to the stochastic perturbation of the gravitational background.

Moreover, since the fluctuations

due to the gravitational background are quite small with respect to the drag term

(that is, we experience, or measure, a sort of mean value of the hidden variables), it follows that

that for

with

, leads to

From (6.31), it is worth noting that in the deterministic limit of standard quantum mechanics, for , we have that .

In the context of stochastic quantum hydrodynamic theory, standard quantum mechanics is regarded as a specific scenario that occurs within a static space-time devoid of the fluctuating backdrop of gravitational dark energy.

In the evolving quantum mechanical densities, situated within spacetime featuring a fluctuating gravitational background, the presence of gravitational dark energy originated by the fluctuations metric tensor of the spacetime is perceived as a field responsible for inducing a drag force on the oscillations of spin waves and the movement of mass density. This phenomenon exhibits similarities to the effect of the Higgs Boson, where its field imparts inertia to elementary particles as they traverse through it.

As a closing observation, it is noteworthy to emphasize the adaptability of the SQHM theory in complementing the broader quantum framework.

7. Measurement of photon entanglement on large distances

Once we establish a unified theory where quantum mechanics governs at the microscopic level, classical physics prevails at the macroscopic scale, and fluctuations seamlessly coexist, we bear the foundational responsibility of validating the theoretical predictions, particularly in the context of photon quantum entanglement at macroscopic level.

Since the time of wave function decay is an important factor in the measuring process, the output of quantum entanglement experiments is necessarily influenced by it. While it is challenging to precisely measure the time it takes for information to transfer itself via entangled photons in a laboratory, this parameter can be more accurately controlled in experiments conducted over planetary distances.

SQHM theory aligns with the idea that relativistic causality and quantum nonlocality are compatible, a concept that is already supported by relativistic quantum field theory. To check this, we analyze the output of two entangled photon experiments traveling in opposite directions in the state

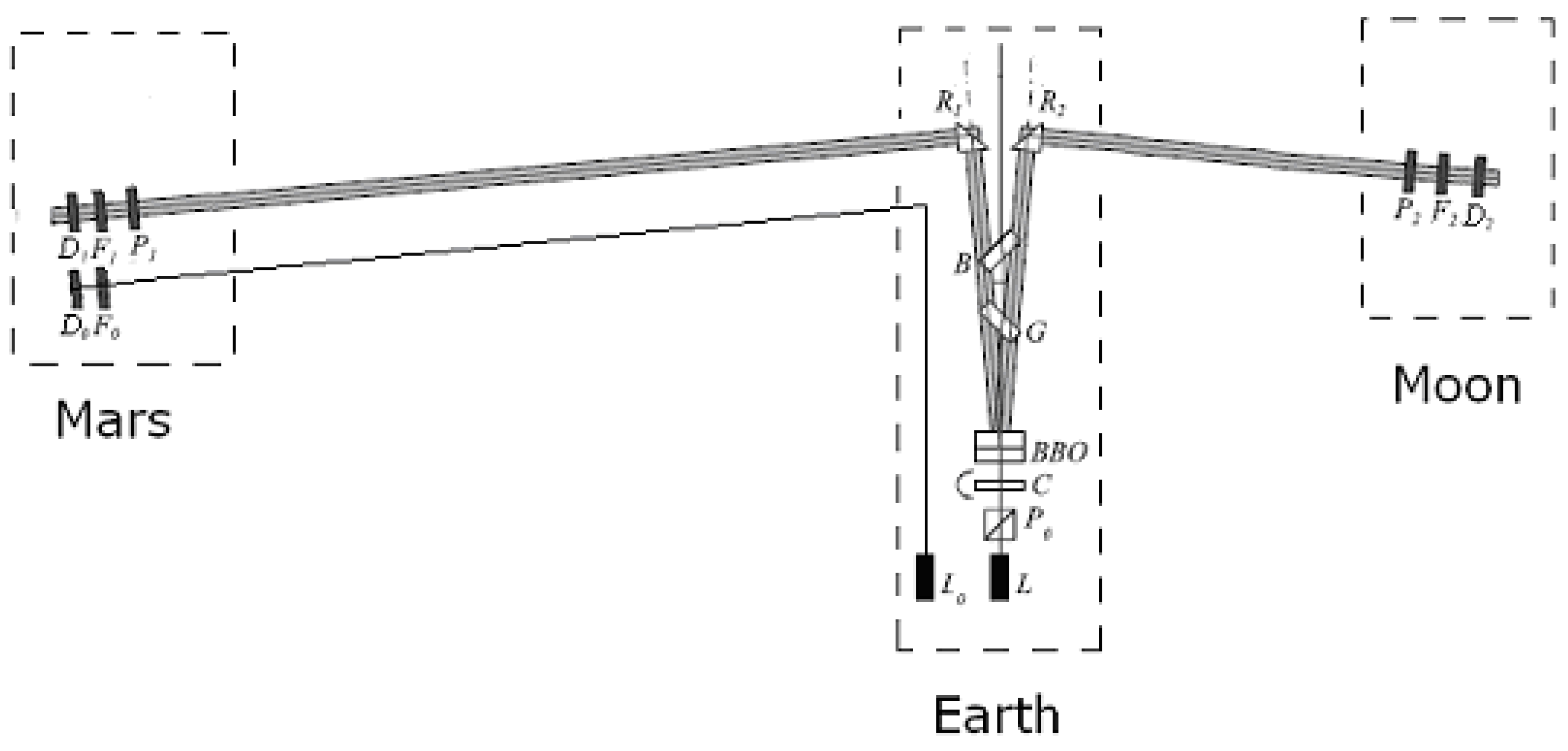

that cross polarizers oriented in the same direction following the scheme in

Figure 1, where

and

are orthogonal directions of polarization.

The assumption that the state of the photon is defined only after the measurement leads to acceptance that the photon superposition state, interacting with the polarizer, is still not fully collapsed neither to nor to until it is adsorbed or goes through the polarizer.

Given that in the SQHM approach, the wave function collapse is not instantaneous but takes a finite time interval, we name them and for the two photons, respectively.

Moreover, we assume that the measurement time starts at the detection of the first entangled photon by the polarizer-photon counter system (at time ) and ends when the other entangled photon is detected at the second polarizer-photon counter system (at time ). We also assume that the detection of each photon immediately occurs at the end of its wavefunction collapse.

The better way to perform the experiment is to increase as much as possible the distance between the two polarizer-photon counter systems. To comply with this requirement, we can consider the photon source on the Earth, the first polarizer-photon counter system on the Moon and the second one on Mars.

For instance, we can suppose that the Moon, the Earth and Mars are aligned with each other. In this case, it follows that the distance between the two polarizer-photon counter systems reads and that , , where and are the Earth-Moon and the Earth-Mars distances, respectively.

Here, we assume that the detection measurement follows the quantum mechanical probability. To determine the modality by which the quantum potential brings the information about the first photon detection to the second photon, we assume that

The quantum potential interaction propagates itself at the speed of light;

The quantum potential has a spatial extension equal to the physical length .

At the time

the first photon arrives and interacts at the moon polarizer, at time

its wavefunction decays at the final measured state, the second photon arrives on Mars at

, and the quantum potential signal generated by the first photon interaction (at

) reaches the second polarizer on Mars at the time

The second photon on Mars decayed to its final state and was measured.

Thus, assuming no superluminal transmission of information, it must result

and therefore,

where

must be measured by utilizing parallel nonentangled photons.

Moreover, in order for the two photons to be quantum entangled, it must also hold that

The value in (7.6) can be obtained by knowing the spectral composition of the photon (see Appendix F). In this case, when photon “one” interacts with the polarizer on the moon, it is still entangled with photon “two” traveling toward Mars.

In this scenario, photons "one" and "two" form a single quantum system that interacts with the polarizer on the moon when photon "one" reaches it. After interacting with the polarizer on the moon, photon "two" travels to Mars carrying in its quantum potential the information about the polarization of photon "one". At this point, we essentially have an "entangled interaction" of the two photons with the first polarizer.

Equation (7.5) has been derived by assuming that the decay of photon "two" to the final measured state begins upon its arrival at the polarizer on Mars and that the quantum potential effect, resulting from the decay of photon "one" on the moon, starts to affect photon "two" after its arrival at the polarizer on Mars (but not during its travel).

This means that the decay of the photon wave function on Mars into the polarizer-photon counter occurs before the arrival of the quantum potential interaction (information) from the first photon detection on the Moon. If the output of the measurement follows the quantum correlation law, this violates the relativistic local causality.

Furthermore, to detect the entangled interaction of photons with the moon polarizer, a counter-experiment can be conducted by enclosing the Moon polarizer-detector in a Faraday cage (approximately 300 meters long), with a diaphragm that closes as soon as the photon enters the cage and before it reaches the Moon polarizer. The closure of the diaphragm forces the two-photon system to interact with the macroscopic environment before interacting with the Moon polarizer. As a result, the photons should decay into decoherent states before their detection and show stochastic polarization states.

7.1. The quantum potential range of photon interactions

Given the photon wavefunction

with Gaussian spectrum

, the quantum correlation length

The same result is obtained if we use the superposition of the two photon fields in calculating the quantum coherence length .

This output allows the possibility that the two entangled photons undergo an “entangled interaction” when interacting with the first polarizer on the moon, generating the “synchronized decay” at the second polarizer on Mars.

7.2. Discussion

The SQHM theory is in line with the concept that relativistic causality and quantum non-locality can coexist, a notion already substantiated by relativistic quantum field theory. It elucidates the synchronization of photon polarization separated by a large distance without necessitating faster-than-light arguments. This is accomplished by leveraging the infinite length of interaction provided by the quantum potential, which effectively binds the two photons into a unique quantum system.

The quantum potential, with its extensive range of interaction, establishes a connection between both photons, one situated on the Moon and the other travelling towards Mars. At the first photon interaction with polarizer the quantum potential changes and will influence the evolution of the other photon and its interaction at the second polarizer. This connection allows for the synchronization of both final states. There is no concealed mechanism at play that involves the two entangled photons, even when they are separated by a distance greater than the characteristic de Broglie length.

In the SQHM, there exists a pre-existing reality before the measurement is conducted by the polarizers. This reality comprises two entangled photons, giving rise to a aggregate quantum potential. Subsequently, when the measurement occurs, the polarizers alter this pre-existing reality, resulting in the production of the polarized state as an output.

If, for any reason, the polarizers at both ends become desynchronized for a duration longer than the decay of the wave function of the photon upon which the initial polarizer is applied, the SQHM theory anticipates that the measurement of the first photon will influence the second photon, regardless of the temporary desynchronization of the polarizers. According to SQHM, this correlation will endure, as it is inherently embedded in the quantum potential, even if the polarizers remain unsynchronized for a period surpassing the collapse of the wave function of the initial photon.

The polarization detection of two quantum entangled photons is a specific measurement process conducted at two separate moments in time. During the first measurement, only a portion of the quantum system is affected (and destroyed), and not the entire system. However, during this initial measurement, the "two photon system" transitions into the measured state as it interacts with the polarizer. Subsequently, when the second photon is detected on Mars, its quantum state is found to be coherent with that one measured at the first photon.

The underlying challenge lies in understanding how the information, which may also be encoded within the quantum potential, can effectively transmit from the first photon to the second photon, as the second photon travels towards Mars. If information cannot propagate faster than the speed of light, it becomes difficult to explain how the second photon's wave function collapses before the quantum potential energy manages to reach the second polarizer. Therefore, in this case, the second photon's wavefunction decay-time will result in a detection delay-time relative to a non-entangled photon that was simultaneously launched from Earth. In this context, the time of application of the first polarizer is possibly defined by another non-entangled photon simultaneously launched from Earth to the Moon.

8. Extending quantum coherence to obtain a large number of entangled Q-bits

If we examine the two quantum coherence lengths, denoted as and , we can develop methodologies to extend quantum coherence over macroscopic distances and achieve a system composed of a large number of Q-bits. The first proposed approach, advocated by , involves lowering the temperature, a method already in use but one that imposes significant constraints on the maintenance of quantum computers. A more intriguing possibility arises from analyzing , where an expansion of the range of interaction of the quantum potential can be leveraged to increase the physical dimensions of the Q-bit system.

One initial insight gleaned from this analysis is that extending the linear range of interparticle interactions can enhance the system size at which quantum behavior remains observable. Furthermore, given that the Hamiltonian interparticle interaction becomes more robust as it strengthens, we can extend the range of quantum potential interactions by reducing the spatial dimensions of intermolecular interactions. This can be achieved through materials composed of two-dimensional structures, such as graphene, or linear one-dimensional molecules, as found in polymers. Notably, the superconducting phase of polymers may endure even at relatively high temperatures. In light of stochastic quantum hydrodynamic theory, superconducting polymer research appears to be more promising in achieving room-temperature quantum computers. The use of linear systems for Q-bits can also gain advantage by the utilization of photon fields since is infinite among entangled photons.

It is worth highlighting that the SQHM itself can serve as a potential source for rapid Q-bits simulations capable of obviating the necessity for the physical instantiation of Q-bit systems.

9. Conclusion

The stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model proposes a way to describe the behavior of quantum systems in the presence of fluctuations in the physical vacuum with a fluctuating metric. The model suggests that the spatial spectrum of noise is not white and has a correlation function with a well-defined physical length determined by the De Broglie characteristic length. This leads to effective quantum entanglement that cannot be removed in systems whose physical length is much smaller than this length.

The non-local quantum interactions may extend beyond the De Broglie length up to a distance that may be finite in non-linear weakly bonded systems.

The Langevin-Schrodinger equation can describe the dynamics of these systems, departing from the deterministic limit of quantum mechanics.

However, as the physical length of the system increases, classical physics may be achieved when the scale of the problem is much larger than the range of interaction of the quantum potential. This is because the long-distance characteristics of the quantum potential and its range of interaction determine the existence of a coarse-grained classical large-scale description.

The SQHM also shows that the minimum uncertainty during the process of measurement asymptotically converges to the quantum uncertainty relations in the limit of zero noise. The principle of minimum uncertainty holds only if interactions and information do not travel faster than the speed of light, which is compatible with the relativistic macroscopic locality and the nonlocal quantum interactions at the microscale.

The stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model (SQHM), which suggests that the interaction of a quantum system with the gravitational background leads to a gradual loss of coherence and the emergence of classical-like behavior, leading to outputs practically equal to those of the decoherence approach. The important difference is that in the SQHM the fluctuations are self-generated (being an intrinsic property due to the characteristics of the spacetime coming from the big-bang) without the need of the envitronment. In the SQHM, weak quantum potentials are not able to maintain coherence in the presence of fluctuations due to the emergence of a drag force leading to a relaxation process known as decoherence.

This effect can be observed in macroscopic systems, such as those made up of molecules and atoms interacting by long-range weak potentials, as in the Lennard-Jones gas phase. In such systems, the effects of decoherence become more pronounced, and the quantum behavior of the system becomes increasingly difficult to observe as the system size and complexity increase. The SQHM provides a useful framework for understanding the interplay between quantum mechanics and classical behavior in such systems.

The stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model suggests that classical mechanics can arise in a quantum system when the physical length of the system is very much larger than the the quantum potential range of interaction.

When quantum system's eigenstates are subjected to fluctuations, their stationary configurations are slightly perturbed but remain stationary and close to those of quantum mechanics. However, when the system evolves in a superposition of states, the fluctuations cause the superposition to relax to the stationary configuration of one of the eigenstates that make up the superposition. This leads to the emergence of classical mechanics on a large scale driven both by temperature dependence the De Broglie length , as for the fluid-superfluid transition of, and for the extension of the quantum potential range of interaction , as for the soli-fluid transition at the melting point of the crystal lattice. The model provides a general path-integral solution that can be obtained in recursive form. It also contains conventional quantum mechanics as the deterministic limit of the theory.

According to the stochastic quantum hydrodynamic model, decoherence is necessary for a quantum measurement to occur in finite time laps, and it also contributes to the execution, data collection, and management of the measuring apparatus. The model suggests that the phenomenon of wavefunction collapse in the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics may align with the concept of wavefunction decay. This decay process has its own distinct kinetics and a finite timespan.

With the premise that wavefunction decay occurs within a finite timeframe during the measurement process, a thought experiment is conducted to scrutinize the measurement of photon entanglement. The SQHM posits the existence of an underlying reality prior to the polarizer measurements. This pre-existing reality consists of two entangled photons, which give rise to an aggregate quantum potential. When a measurement takes place, the polarizers modify this pre-existing reality, resulting in the emergence of polarized states as the outcome. According to the SQHM framework, the process of polarization detection for two quantum-entangled photons occurs over two distinct steps. During the first one, only a portion of the quantum system is affected. However, during the first part of the measurement, the "two photon system" transitions into the measured state as it interacts with the polarizer. Consequently, when the second photon is detected on Mars, its quantum state is found to be coherent with the state measured for the first photon. The quantum hydrodynamic approach posits that the information encoded within the quantum potential can effectively transfer from the first photon to the second one, resulting in a delay of the second photon's detection due to its prolonged wavefunction decay-time.

Furthermore, by extending the Madelung hydrodynamic representation of the Pauli equation to its stochastic counterpart, it becomes feasible to establish the theoretical basis for the so-called hidden variable of the IsoRedShift Mechanics model.

The model reveals that canonical quantum mechanics is applicable only in a perfectly static universal spacetime. In real-world scenarios, due to fluctuations in the spacetime background caused by the Big Bang and other cosmological sources, the quantum evolution of mass densities and spin waves encounters a resistance force while traveling through spacetime with oscillating metrics. This phenomenon shows some analogy to the effect observed with the Higgs Boson, where its field imparts inertia to elementary particles as they move through it.

The theory demonstrates that the hidden variable parameter, needed for the accurate description of nuclear mechanics, represents the stochastic-induced correction to the conventional quantum mechanics representing the deterministic limit of the stochastic quantum theory.

The experimental measurements of the hidden variable in nuclear mechanics provide empirical evidence of the presence of dark energy of the fluctuating gravitational background that perturbs the deterministic expression of quantum mechanics.

The portrayal provided by the stochastic quantum hydrodynamic theory presents a scenario in which classical mechanics emerges on a macroscopic scale within a space-time filled with fluctuations in curvature. This depiction seamlessly corresponds with the quantum-gravitational representation of the cosmos, where gravity functions as the trigger for universal decoherence.

The model shows that if reversible quantum mechanics are realized in a static vacuum, the measurement process cannot take a finite time to occur.

Appendix A. Quantum mechanics as imaginary-time stochastic process

in the quantum integral path representation, is equivalent to the FPE [76] that in the unidimensional case reads

where the solution

with

and

leads to the imaginary time

evolution amplitude

By comparing (A.6) with (A.2), we can see that the quantum particle subject to the potential

is equivalent to the Brownian particle of mass

subject to friction with coefficient

obeying the stochastic motion equation

where

and where .

The pseudo-diffusional evolution of the quantum mass density

described by the imaginary-time stochastic process (A.8) [76] in the zero-noise (i.e., deterministic) quantum hydrodynamic formalism is described by the motion of a particle density

with velocity

governed by the following equations [17,19, 27]:

where, for a nonrelativistic particle in an external potential,

and

where

is the quantum pseudopotential that reads

Expression (A.14) leads to the motion equation

and to the stationary equilibrium condition (i.e.,

)

that, by using (A.14), reads

By comparing the expansive term

in (A.17), for example, with the chemical diffusion described by the Fick equation, we can observe that the quantum imaginary stochastic process (A.8) gives rise a “pseudo-diffusional” process propelled by the quantum potential

whereas irreversible chemical diffusion is driven by the potential . The fundamental distinction between the two lies in the fact that in the latter case the diffusion coefficient can be defined positive, whereas for the former case, it cannot.

Both the (real time) thermal stochastic process and the quantum (imaginary time) stochastic process show that stationary states (i.e., ) occur when the force of the driving potential, which accounts for the effect of the fluctuations, exactly counterbalances, point by point, that one given by the Hamiltonian potential .

The further basic difference between the two is that, in the quantum case, more than one stationary state (i.e., the quantum eigenstates) can possibly exist [

27].

Therefore, beyond the analogy, the two processes have fundamental differences.

For instance, the quantum “imaginary-time” diffusion, concerning the mass distribution of Gaussian state, leads to the “ballistic” expansion with the variance

following the time law

while the spreading of the same initial mass distribution, submitted to thermal fluctuations, follows the thermal expansion with the law

Notably, the “real-time” stochastic dynamics are dissipative, while the “imaginary-time” stochastic dynamics of quantum mechanics are reversible and “deterministic”. The ballistic behavior of Gaussian wavefunction (A.19) can be obtained from the limit of a particle in a harmonic potential in the limit of zero amplitude [

26].

This dissipative-to-conservative switching of characteristics from the real to the imaginary-time stochastic process is analogous to the rheology of elastic solids, where the real elastic constants describe conservative elastic dynamics, while the imaginary elastic constants account for the viscous dissipative behavior.

In the quantum deterministic evolution, there is no loss of information with reversible dynamics: the superposition of states (with their complex configuration) is maintained during time and never relaxes to a simpler (higher entropy) stationary configuration.

Appendix B. Stochastic Generalization of the Madelung Quantum Hydrodynamic Model

In the presence of curvature fluctuations, the mass distribution density (MDD)

becomes a stochastic function that we can ideally pose

, where

is the fluctuating part and

is the regular part that obeys the limit condition

The characteristics of the Madelung quantum potential that, in the presence of stochastic noise, fluctuates can be derived by generally posing that is composed of the regular part

(to be defined) plus the fluctuating part

, such as

where the stochastic part of the quantum potential

leads to the force noise

where the noise correlation function reads

with

In addition, the regular part

for microscopic systems (

), without loss of generality, can be rearranged as

where

is the probability mass density function (PMD) associated with the stochastic process we will define that in the deterministic limit obeys the condition

.

Given the quantum hydrodynamic equation of motion (3) for the fluctuating

MDD

,

we can rearrange it as

that in the deterministic case is null since

generates an additional acceleration in the motion equation (B.8), which is close to the stationary condition (i.e.,

), can be developed in the series approximation and reads

Moreover, since near the limiting condition (B.10), we can pose

with

and where

is smooth with

finite (since

), it follows that

Moreover, given that at the stationary condition (i.e.,

), it holds

and thus

the mean

, by (B.13) reads

Therefore, the general form of the stochastic term

as the zero-mean noise, with null correlation time (see (B.4)), reads

Therefore, at the leading order in

, sufficiently close to the deterministic limit of quantum mechanics (

), for the isotropic case

, we obtain that

The first-order approximation (B.18) allows us to write (B.7) as the Marcovian process

where

where

where

is the probability transition function of the Smolukowski conservation equation [

20]

of the Marcovian process (B.19).

Moreover, by comparing (B.7) in the form

with (B.19), it follows that

and that

Generally, it must be observed that the validity of (B.19) is not general since, as shown in ref. [79, 88-90], the friction coefficient is never constant but only in the case of a linear harmonic oscillator. In addition, since to have quantum decoupling with the environment, nonlinear interaction is necessary (see relations (5.05-06)), actually, the linear case with the constant cannot be rigorously assumed except for the case that corresponds to the deterministic limit of the theory, namely, conventional quantum mechanics.

Appendix C. The Marcovian noise approximation in the presence of the quantum potential

Once the infinitesimal dark matter fluctuations have broken the quantum coherence on cosmological scale (e.g., for baryonic particles with mass , it is enough to have ), it follows that the resulting universe can acquire the classical behavior and can be divided into quantum decoupled sub-parts (in weak gravity regions with low curvature since the Newtonian gravity is sufficiently feeble for satisfying condition (5.02)). In this context, we can postulate the existence of the classical environment.

Thus, for a mesoscale quantum system in contact with a classical environment, it is possible to consider the Markovian process (6.28, B.23-4)

In the presence of the quantum potential, the evolution of the MDD from the initial configuration, determined by (4.8), depends on the exact random sequence of the force inputs of the Marcovian noise.

The probabilistic phase space mass density

of the Smolukowski equation

for the Marcovian process (C.2) [77] is somehow indefinite since the quantum potential, being nonlocal, also depends on at the subsequent instants (see (4.20-23) in § 4).

Even if the connection (B.11)

between the stochastic function

and the distribution

cannot be generally warranted, in the small noise approximation, introduces the linkage between

and

(i.e., information about

can be obtained by knowing

and

) and leads to the motion equation

where

in (C.5) is a function of the PMD

instead of the MDD

as in (C.2).

It is worth mentioning that the applicability of (C.5) is not general, but it is strictly subjected to the condition of being applied to small-scale systems with that, being close to the quantum deterministic condition, admit stationary states (the fluctuating homology of the quantum eigenstates with). In this case, for sufficiently slow kinetics (i.e., close to the stationary condition ), it is possible to assume that the collection of all possible MDDs approximately reproduces the PMD .

The Smolukowski (conservation) equation and the non-Gaussian character induced by the quantum potential

By using the method of Pontryagin [77], the Smolukowski equation leads to the differential conservation equation for the PTF

In the stochastic case, (C.13) substitutes (2.2) as a conservation equation.

Moreover, in the classical case (i.e.,

), the Gaussian character of the PTF is warranted by the property that the cumulants are higher than two [77]

This condition is satisfied in classical problems since the continuity of the Hamiltonian potential leads to velocities that remain finite as , leading to a nonzero contribution just for the first term .

In the quantum case, since the quantum potential depends on the derivatives of and since in macroscopic systems the spatial correlation function of noise (6.5) converges to the delta-function (i.e., white noise spectrum (see (6.7)), very high spikes of quantum force are possible on very close points as . This behavior can give finite nonzero contributions even in the limit of infinitesimal time intervals. In this case, in the limit of , cumulants higher than two contribute to the probability transition function .

Such spiking quantum potential contributions grow as a function of . leads to a jumping process that appears in the high-order term in (B.11).

The motion equation for the spatial densities

Given the conservation equation (C.6) for the phase space density

by integrating it over the momenta, we obtain

that, with the condition

and by posing

leads to

where

so that (C.17) can be rearranged as

where

describes the compressibility of the mass density distribution as a consequence of dissipation.

Appendix D. Harmonic Oscillator Eigenstates in fluctuating spacetime

In the case of linear systems

the equilibrium condition, referring to the stationary configuration of the eigenstates, leads to