Submitted:

26 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

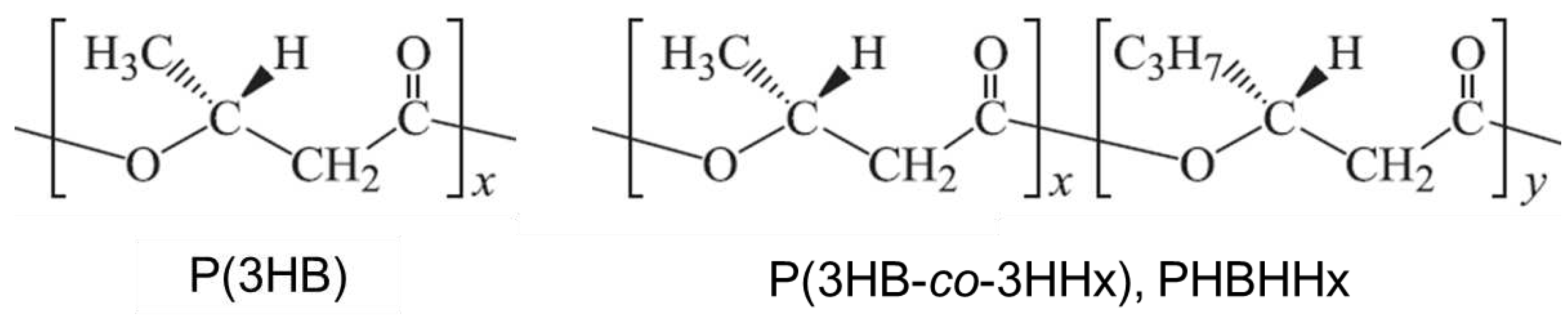

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. Culture Medium

2.3. Subculture and Preculture

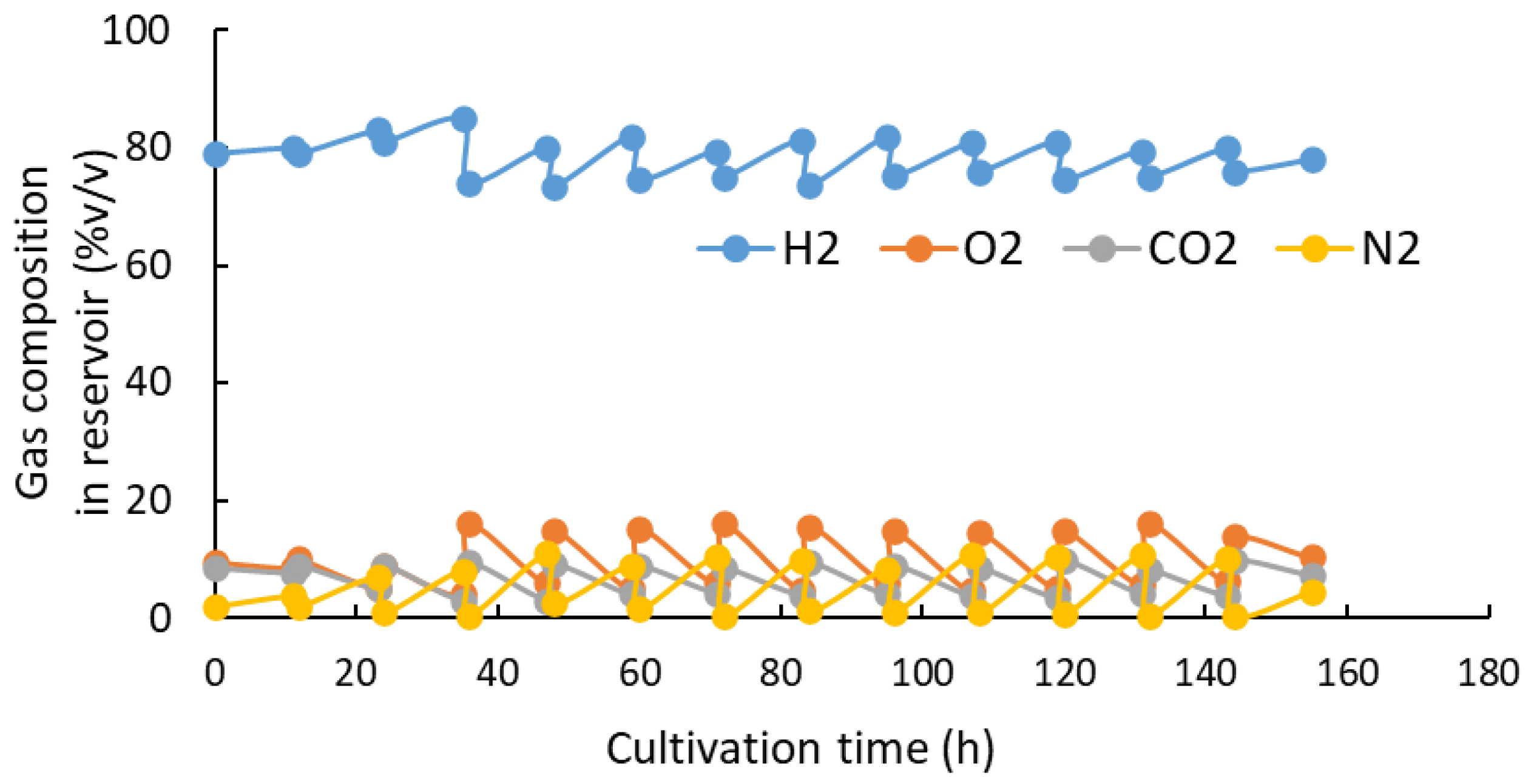

2.4. Recycled-Gas Closed-Circuit Culture System (RGCC Culture System)

2.5. Condition for Main Culture

2.6. Analyses

3. Results

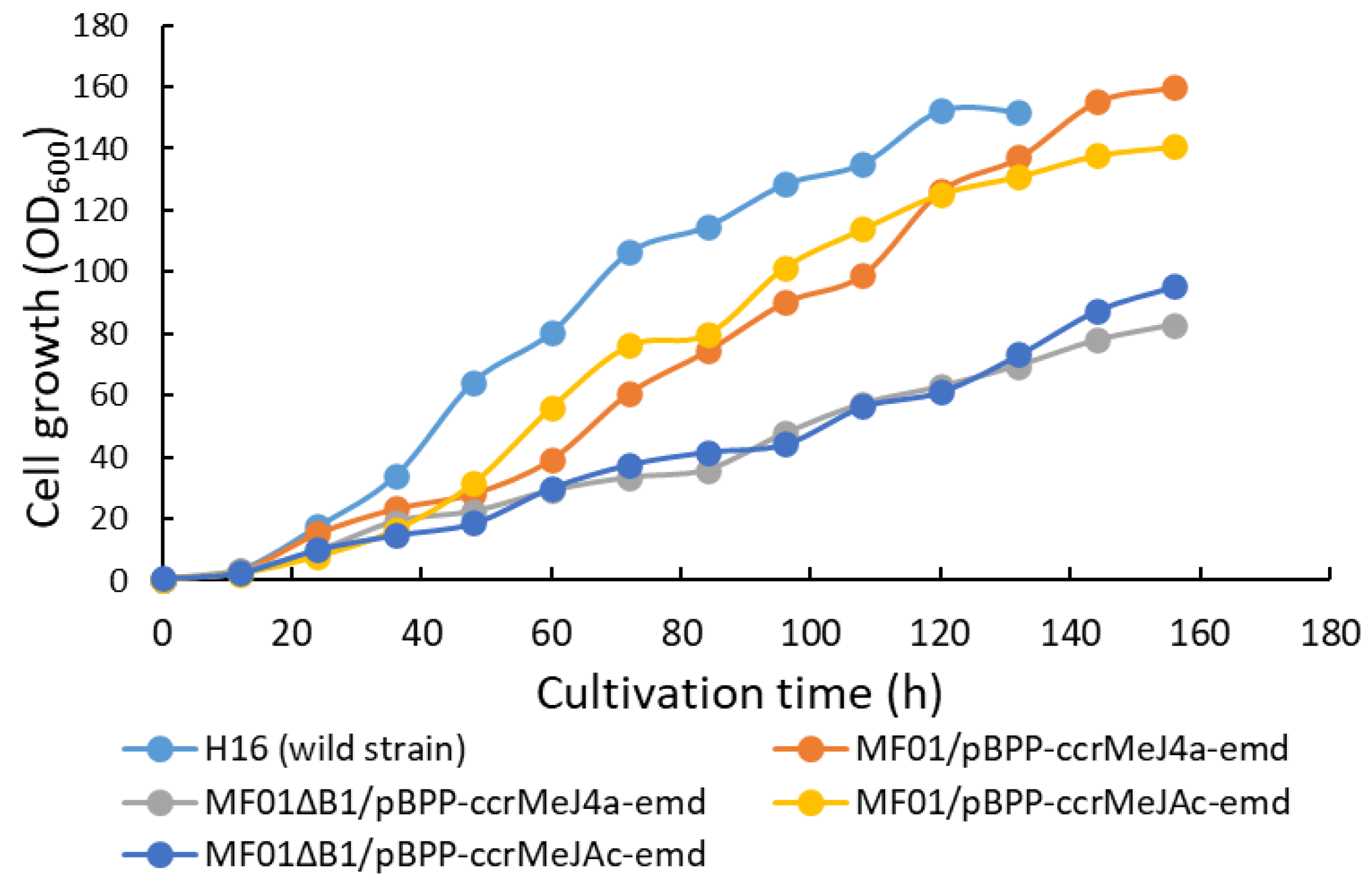

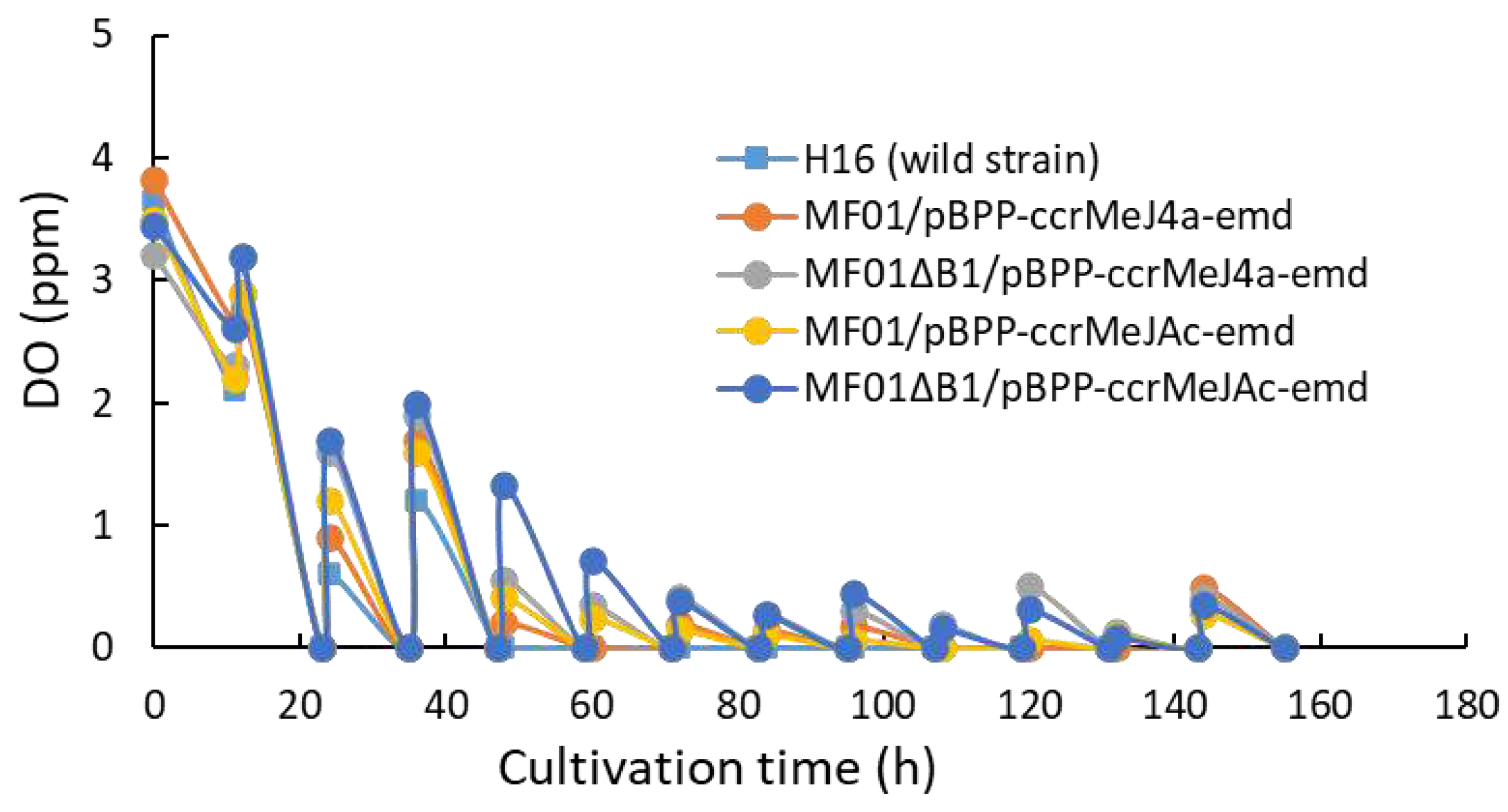

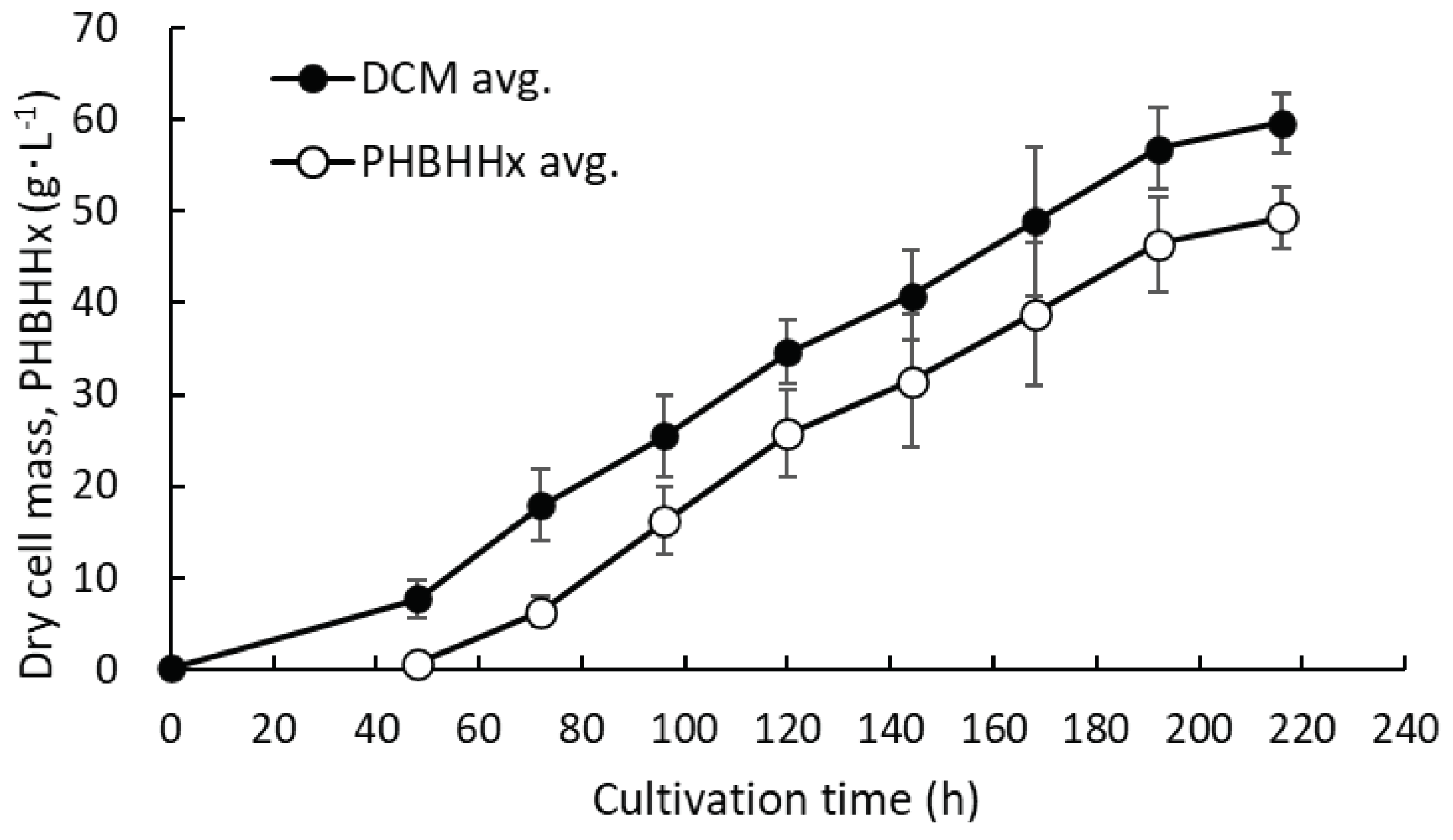

3.1. pH-Stat Batch Culture of Recombinant Strains

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Lu, J.; Tappel, R.C.; Nomura, C.T. Mini-review: Biosynthesis of poly(hydroxyalkanoates). Polym. Rev. 2009, 49, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, R.; Santagata, G.; Corrado, I.; Pezzella, C.; Serio, M.D. In vivo and post-synthesis strategies to enhance the properties of PHB-based materials: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 619266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eraslan, k.; Aversa, C.; Nofar, M.; Barletta, M.; Gisario, A.; Salehiyan, R.; Goksu, Y.A. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH): Synthesis, properties, and applications – review. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 167, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashiwa, H.; Fukuda, R.; Okura, T.; Sato, S.; Nakayama, A. Microbial degradation behavior in seawater of polyester blends containing poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx). Mar. Drugs. 2018, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, A.; Taylor, D.S. Commercial marine-degradable polymers for flexible packaging. iScience. 2020, 23, 8–101353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, E.; Kasuya, K.; Kobayashi, G.; Shiotani, T.; Shima, Y.; Doi, Y. Physical properties and biodegradability of microbial poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate). Macromolecules. 1994, 27, 878–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Kitamura, S.; Abe, H. Microbial synthesis and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate). Macromolecules. 1995, 28, 4822–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneka Corporation News Release. Completion of KANEKA Biodegradable Polymer PHBH™ plant with annual production of 5,000 tons. 19 December 2019. https://www.kaneka.co.jp/en/topics/news/nr20191219/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Kaneka Corporation News Release. Kaneka to significantly increase its production capacity for KANEKA Biodegradable Polymer Green Planet™ in Japan. February 7, 2022. https://www.kaneka.co.jp/en/topics/news/2022/ennr2202071.html (accessed 1 October 2023).

- Boey, J.Y.; Mohamad, L.; Khok, Y.S.; Tay, G.S.; Baidurah, S. A Review of the applications and biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates and poly(lactic acid) and its composites. Polymers. 2021, 13, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insomphun, C.; Xie, H.; Mifune, J.; Kawashima, Y.; Orita, I.; Nakamura, S.; Fukui, T. Improved artificial pathway for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) with high C6-monomer composition from fructose in Ralstonia eutropha. Metab. Eng. 2015, 27, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kurita, S.; Orita, I.; Nakamura, S.; Fukui, T. Modification of acetoacetyl-CoA reduction step in Ralstonia eutropha for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from structurally unrelated compounds. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, A.; Tanaka, K.; Taga, N. Microbial production of poly-D-3-hydroxybutyrate from CO2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 57, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Kazumasa Yoshida, K.; Orita, I.; Fukui, T. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from CO2 by a recombinant Cupriavidus necator. Bioengineering, 2021, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaki, A.; Tanaka, K. Batch culture of Alcaligenes eutrophus ATCC 17697T using recycled gas closed circuit culture system. J. Ferment. Bioeng 1990, 69, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, A.; Tanaka, K. Production of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid from carbon dioxide by Alcaligenes eutrophus ATCC 17697T. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1991, 71, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, T.; Tanaka, K.; Ishizaki, A.; Stanbury, P.F. Development of a dissolved hydrogen sensor and its application to evaluation of hydrogen mass transfer. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1993, 76, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Ishizaki, A.; Kanamaru, T.; Kawano, T. Production of poly(D-3-hydroxybutyrate) from CO2, H2, and CO2 by high cell density autotrophic cultivation of Alcaligenes eutrophus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1995, 45, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taga, N.; Tanaka, K.; Ishizaki, A. Effects of rheological change by addition of carboxymethylcellulose in culture media of an air-lift fermentor on poly-D-3-hydroxybutyric acid productivity in autotrophic culture of hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Alcaligenes eutrophus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997, 53, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Tsuge, T.; Tanaka, K.; Ishizaki, A. Control of acetic acid concentration by pH-stat continuous substrate feeding in heterotrophic culture phase of two-stage cultivation of Alcaligenes eutrophus for production of P(3HB) from CO2, H2 and O2 under non-explosive condition. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1999, 62, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Miyawaki, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Matsusaki, H. Cell growth and P(3HB) accumulation from CO2 of a carbon monoxide-tolerant hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Ideonella sp. O-1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, H.G.; Lafferty, R.M. Novel energy and carbon sources. The production of biomass from hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Adv. Biochem. Eng. 1971, 143, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, T.; Igarashi, Y.; Minoda, Y. Isolation and culture conditions of a bacterium grown on hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Agr. Biol. Chem. 1975, 39, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volova, T.G.; Kiselev, E.G.; Shishatskaya, E.I.; Zhila, E.I.; Boyandin, A.N.; Syrvacheva, D.A.; Vinogradova, O.N.; Kalacheva, G.S.; Vasiliev, A.D.; Peterson, I.V. Cell growth and accumulation of polyhydroxyalkanoates from CO2 and H2 of a hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Cupriavidus eutrophus B-10646. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 146, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Bao, H.J.; Kang, C.-K.; Fukui, T.; Doi, Y. Production of a novel copolyester of 3-hydroxybutyric acid and medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids by Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 from sugars. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 45, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, L.; Mozumder, M.S.; Dubreuil, M.; Volcke, E.; Wever, H. Sustainable autotrophic production of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) from CO2 using a two-stage cultivation system. Catal.Today. 2015, 257 Pt 2, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyahara, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Thorbecke, R.; Mizuno, S.; Tsuge, T. Autotrophic biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate by Ralstonia eutropha from non-combustible gas mixture with low hydrogen content. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambauer, V.; Kratzer, R. Lab-scale cultivation of Cupriavidus necator on explosive gas mixtures: Carbon dioxide fixation into polyhydroxybutyrate. Bioengineering. 2022, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambauer, V.; Permann, A.; Petrášek, Z.; Subotić, V.; Hochenauer, C.; Kratzer, R.; Reichhartinger, M. Automatic control of chemolithotrophic cultivation of Cupriavidus necator: Optimization of oxygen supply for enhanced bioplastic production. Fermentation. 2023, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, M.S.; Garcia-Gonzalez, L.; Wever, H.; Volcke, E. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) production from CO2: Model development and process optimization. Biochem. Eng. J. 2015, 98, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lu, Y. Carbon dioxide fixation by a hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium: Biomass yield, reversal respiratory quotient, stoichiometric equations and bioenergetics. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 152, 15–107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Munasinghe, P. Gas fermentation enhancement for chemolithotrophic growth of Cupriavidus necator on carbon dioxide. Fermentation. 2018, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inseon Park, I.; Jho, E.h.; Nam, K. Optimization of carbon dioxide and valeric acid utilization for polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis by Cupriavidus necator. J. Polym. Environ. 2014, 22, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghysels, S.; Mozumder, M.S.; Wever, H.; Volcke, E. .; Garcia-Gonzalez, L. Targeted poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) bioplastic production from carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangle, S.N.; Ziesack, M. : Buckley, S.; Trivedi, D.; Loh, D.M.; Nocera, D.G.; Silvera, P.A. Valorization of CO2 through lithoautotrophic production of sustainable chemicals in Cupriavidus necator. Metab. Eng. 2020, 62, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Yamane, T.; Shimizu, S. ; Mass production of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid by fed-batch culture with controlled carbon/nitrogen feeding. Appl. Microbiolo. Biotechnol. 1986, 24, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.W.; Hahn, S.K.; Chang, Y.K.; Chang, H.N. Production of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) by high cell density fed-batch culture of Alcaligenes eutrophus with phosphate limitation, Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997, 55, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Used strains | Relevant marker |

|---|---|

| C. necator H16 C. necator MF01 C. necator MF01ΔB1 |

Wild type H16 derivative; ΔphaC::phaCNSDG , ΔphaA::bktB MF01 derivative; ΔphaB1 |

| Used plasmids | |

| pBPP pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd |

pBBR1-MCS2 derivative; PphaP1, TrrnB, pBPP derivative; ccrMe, phaJ4a, emdMm pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd derivative; ΔphaJ4a::phaJAc |

| Strains/Plasmid | Dry cell mass (g・L-1) |

PHBHHx content in cells (w/w%) | Monomer composition (mol%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HB | 3HHx | |||

| H16 (wild strain) | 44.05 | 78.5 | 100.0 | 0 |

| MF01/pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd | 45.42 | 57.7 | 92.9 | 7.1 |

| MF01ΔB1/pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd | 23.06 | 66.8 | 78.8 | 21.2 |

| MF01/pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd | 40.12 | 83.9 | 89.1 | 10.9 |

| MF01ΔB1/pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd | 26.70 | 75.5 | 90.9 | 9.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).