Introduction

Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment of tendon injuries in horses was first described in a report dating almost 20 years back by now [

1]. Since this pioneering case study, MSCs received tremendous attention in the equine community, and hope was raised that translation into human therapies could be facilitated based on experiences in equine medicine. In the following years, large case studies were published with highly promising outcomes [

2,

3,

4], albeit with historical controls which were not directly comparable. Furthermore, several studies were performed that focused on the treatment of experimentally induced equine tendon injuries with MSCs. Most of them reported improvements of the tendon structure and composition [

5,

6,

7,

8], but this could not be convincingly confirmed in other experimental studies [

9,

10].

The conflicting outcomes of experimental studies could be due to different models for tendon lesion induction used (collagenase injection vs. mechanical disruption), while no model can actually reflect the complex naturally occurring pathophysiology. In this context, the study in horses with naturally occurring tendinopathy performed by Smith et al. (2013) needs to be highlighted [

11]. This study confirmed the improvement of histological, biochemical and biomechanical parameters upon MSC treatment as compared to controls in a more clinically relevant context. However, the animals were sacrificed instead of being returned to full training in that study, thus no information on long-term clinical outcome was available. Furthermore, the horses were treated with autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs in bone marrow supernatant, while the controls received saline [

11], which did not allow conclusions regarding the efficacy of the MSCs alone. Eventually, another decade later, it must be acknowledged that clinical evidence of improved healing after local MSC treatment is still not sufficient.

The lack of a comprehensive clinical study in horses is owed to anticipated difficulties with the recruitment of suitable equine patients and compliant horse owners who agree to the blinded treatment and cope with the efforts associated with the follow-up. Nevertheless, this challenge has to be accepted to reach a satisfactory level of evidence for this MSC-based regenerative therapy. Consequently, the authors performed a prospective, randomized, controlled and triple blind pilot study, aiming to establish the prerequisites for the design of a larger and finally proving study with a simplified, efficient follow-up, given that the outcome of this pilot study would justify further efforts.

Materials and Methods

Aims and study design

The aims of this study were to gain first insights into the efficacy of local allogeneic adipose-derived MSC treatment for naturally occurring tendon disease, and to identify suitable outcome measures for tendon healing in this context. Equine patients were recruited at three German veterinary teaching hospitals, examined and allocated to treatment groups by stratified block randomization. Strata were defined based on the duration of symptoms before the first presentation (A: < 2 weeks; B: 2 weeks to 2 months). Treatment included the intralesional injection of MSCs in horse serum (MSC group) or horse serum only (control), as allocated by the laboratory staff. Standardized clinical examinations and diagnostic imaging were performed before treatment, and 6 weeks as well as 3, 6, 12 and 18 months after treatment. All horses were subjected to a controlled exercise program. The rate of re-injuries until 12 months after treatment was chosen as primary endpoint. Treating veterinarians, examiners as well as horse owners were blinded to the treatment group.

MSC recovery and culture

The MSCs had been isolated by enzyme-free explant culture from a healthy donor warmblood horse (gelding, aged 6 years) euthanized for unrelated reasons. The cells were isolated and expanded without xenogeneic serum supplements. The StemMACS™ MSC Expansion Media Kit XF human (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was used as culture medium and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 0.1% gentamycin were added during the explant culture. TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (Gibco™, ThermoFisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) was used for passaging. After the first passaging, CD14+ cells were depleted by magnetic cell separation as detailed previously [

12]. The MSCs were then further expanded and split into portions for cryopreservation at passage 2, using Synth-a-Freeze™ Cryopreservation Medium (Gibco™, ThermoFisher Scientific) and a Mr. Frosty freezing container (Nalgene™, ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For MSC treatments, MSCs were thawed and expanded in the same culture medium, but supplemented with 2% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) and without antibiotics. After cell harvest at passage 3, MSCs suspended in the same horse serum (5 x 10

6 MSCs per mL) and aspirated in opaque syringes for transport and cell injection. Syringes with serum only were prepared for the control group. Aliquots of MSCs before and after cryopreservation were subjected to MSC characterization, including immunophenotyping and differentiation into mesenchymal lineage cells. Differentiation [

12], monoclonal antibody staining for CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD14, CD34, CD45, CD79α and MHCII [

12] and CD44 [

13], as well as flow cytometric analysis [

12,

13] were performed as described in detail earlier. Chondrogenic differentiation was not attempted to reduce the cell numbers required for characterization. Routine quality controls regarding cell morphology and viability were performed and documented during each culture. Transport of MSCs and serum to the respective clinic was performed overnight under controlled cooled conditions.

Animals and inclusion criteria

Horses aged between 3 and 25 years and presenting with naturally occurring tendon disease were recruited. To be included, the injury had to be located within the metacarpal region of one of the forelimb superficial digital flexor tendons and the onset of symptoms had to date back no more than 2 months prior to initial presentation. Previous systemic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and local treatments with bandages and ointments were tolerated, whereas horses that had already received any intralesional or other than the mentioned treatments were excluded. Moreover, the owners had to agree to follow a standardized rehabilitation training schedule and to present their horses for the regular follow-up examinations for at least 12 months, with an optional final examination 18 months after treatment. Fifteen horses were initially included, of which one later had to be excluded and replaced due to significant incompliance with the rehabilitation training schedule. Seven horses per treatment group completed the study until the primary endpoint 12 months after treatment and were included in the data analyses (

Table 1).

Treatment procedure

The horses were treated with a local injection of either allogeneic adipose-derived MSCs suspended in GMP-grade horse serum or with this type of serum alone, as defined by the block randomization. The treatment dose was adapted to the size of the tendon lesion, as determined by B-mode ultrasonography during the initial examination (5 x 10

6 MSCs in 1 mL serum or 1 mL serum per 1 cm

3 lesion volume). For treatment, the horses were sedated using detomidine (0.01 mg per kg bwt; Cespesedan®, CP-Pharma, Burgdorf, Germany) and butorphanol (0.01 mg per kg bwt; Butorgesic®, CP-Pharma), an ulnar nerve block was performed using lidocaine 2% (Bela-pharm, Vechta, Germany) and the injection site was clipped and aseptically prepared. After intracutaneus infiltration with 1 mL of lidocaine, MSCs and / or serum were injected intralesionally using a 19 G cannula under ultrasonographic guidance. A lateral approach transverse to the longitudinal axis of the tendon was chosen while the horse was bearing weight. The maximum volume per injection site was set at 2 mL, so that lesions with a volume > 2 cm

3 were injected at two or more equidistant sites to achieve a homogeneous distribution of MSCs or serum within the lesion. The distal limbs were bandaged, the horses received phenylbutazone (2.2 mg per kg bwt; CP-Pharma) for 2 days and were returned to their owners. Two weeks after treatment, the horses started the rehabilitation training with their owners, using a previously described controlled exercise schedule [

14], which consisted of 16 weeks of walking exercise (gradually increasing intervals from 5 to 40 minutes), followed by 16 weeks with additional training at a trot (increasing intervals from 5 to 20 minutes) while intervals of walking exercise were decreased (from 40 to 25 minutes). During the final 16 weeks horse were exercised 45 minutes daily including gradually increasing gallop training. The exercise schedule was adapted if necessary, depending on the cumulative clinical inflammation and lameness score. The two possible scenarios necessitating schedule adjustment were as follows:

If a horse was lame at a trot (score 1 or 2/5) during a scheduled examination or showed an increase in clinical signs of inflammation (increase in heat, pain or swelling) compared to the previous examination, the exercise level was not further increased. If the horse had already been scheduled to trot or gallop, exercise was reduced to hand walking. In these cases, a clinical revaluation was performed three weeks later, and the level of exercise determined depending on the respective clinical findings.

If a horse was lame at a walk (score ≥ 3/5) on the day of examination the horse received box-rest and was re-evaluated 7 days later. If lameness at walk was detected at the day of re-evaluation the standard exercise schedule was re-started from the beginning.

Furthermore, the exercise schedule was adjusted in accordance with the owner if deemed necessary due other pathologies (e.g., colic, lameness on another leg etc.).

Clinical follow-up

At each examination, a cumulative clinical inflammation score of the injury site was recorded, which included the parameters swelling, pain to palpation and skin surface temperature, with each parameter ranging from 0 score points (normal) to 3 score points (highly abnormal) [

15]. Furthermore, weight bearing and gait were evaluated during walk and trot, using a lameness score ranging from 0 (normal) to 5 (highly abnormal) [

9]. This was performed on hard and soft ground and the score points for each were added up to a total lameness score. Finally, possible adverse reactions, the progress of the rehabilitation training and the occurrence of re-injuries were documented. Adverse reactions and re-injuries were confirmed by the examining veterinarian after being reported by the owner.

Diagnostic imaging

All clinical examinations were complemented by diagnostic imaging. B-mode ultrasonography, using Logiq E9 or Logiq P2 (GE-Healthcare, Solingen, Germany) or Aplio MX (Toshiba, Zoetermeer, Netherlands) machines, was performed in all horses. Seven transverse and four longitudinal images were acquired from the metacarpal tendon region at defined levels [

16]. The findings were documented using a previously described score [

17], at which the tendon was evaluated regarding echogenicity and fibre alignment, with score points ranging from 0 (normal) to 3 (highly abnormal) for each parameter. Both scores for all images per examination were added up for further analysis. Furthermore, the tendon cross-sectional area (TCSA) was measured at each transverse level. The mean TCSA of the whole metacarpal tendon segment was calculated, and these data were normalized to the equivalent contralateral TCSA value to account for the differences in body height.

Moreover, most patients (n = 6 per group) additionally underwent color Doppler ultrasonography (CDU) using the ultrasound machines specified above and ultrasonographic tissue characterization (UTC; UTC scan unit, configuration 2011, UTC Imaging B.V., Stein, Netherlands). For both, again the whole metacarpal tendon segment was included in the assessment. In CDU, the mean percentage of vascularized area within the tendon was calculated from five images per examination as previously described [

19]. In UTC, the percentage of altered and non-mature tendon tissue, as displayed by black (echo type IV), red (echo type III) and blue (echo type II) pixels, was calculated and normalized to the contralateral tendon. Exemplary patients (n = 1 per group) were subject to 0.27 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging instead of CDU and UTC, using the Hallmarq Standing Equine MRI system (Hallmarq, Surrey, UK) as described previously [

19].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM, Ehningen, Germany). As data were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used. To compare the outcome over time with the status before treatment, Friedman and subsequent post hoc tests for paired samples were used within each group and p-values were Bonferroni-corrected for the number of relevant comparisons per analysis. To compare the two groups directly, the differences in the respective parameters over time were calculated for each time point (value at month x – value before treatment (month 0)), so that higher values reflect a worsening and lower values an improvement. With these data, Mann-Whitney-U-tests for unpaired samples were computed for the group comparisons in a hypothesis-based approach. Differences were considered as significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

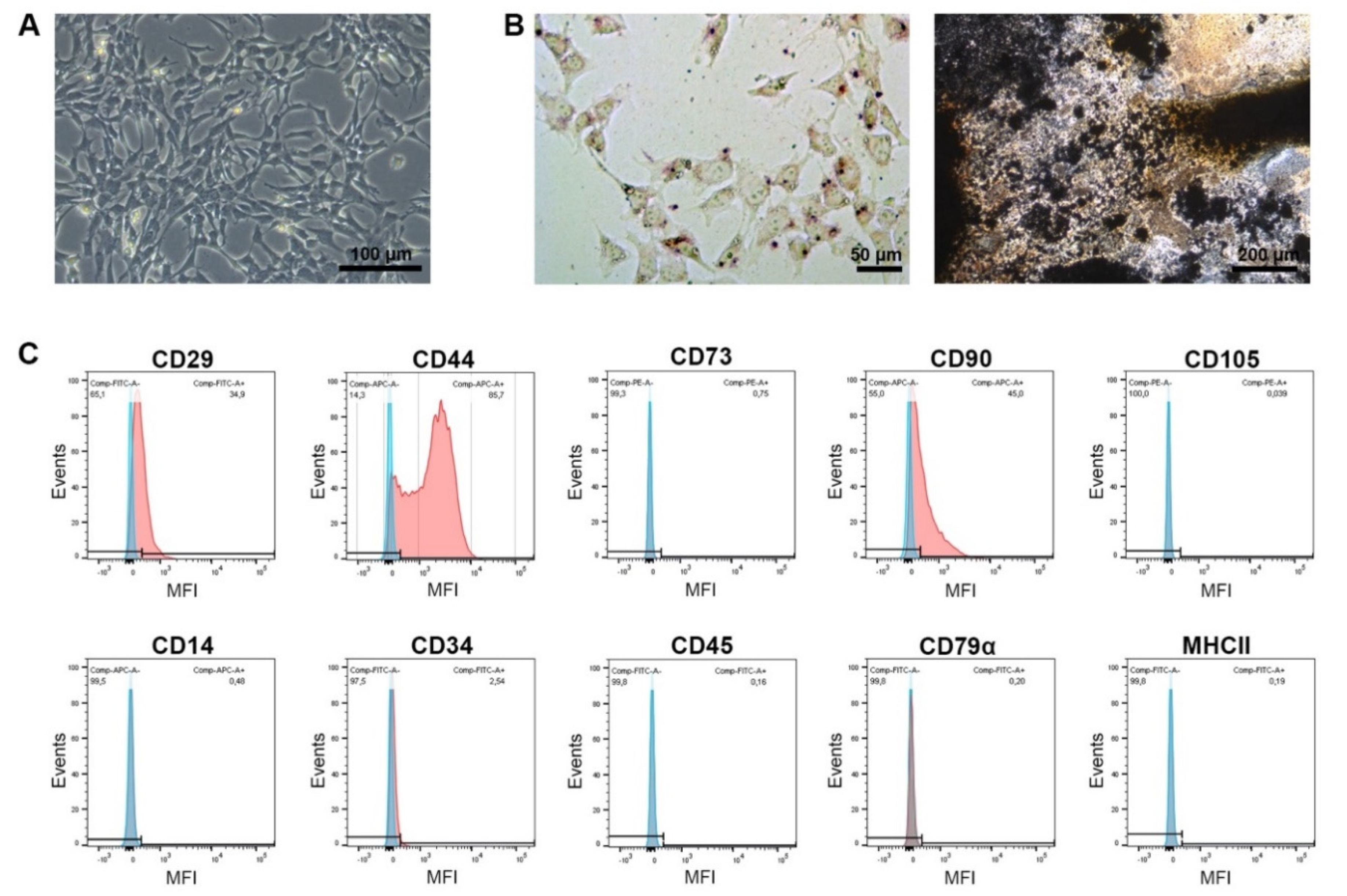

MSC characterization

The MSCs were spindle-shaped in plastic-adherent culture and capable of differentiation into adipocytes and osteoblasts, as shown by lipid vacuole accumulation and deposition of mineralized matrix, respectively. This was confirmed after cell isolation and sorting as well as for exemplary MSC portions that had been thawed, expanded and used for treatment. After isolation and sorting, the MSCs were positive for the inclusion markers CD29, CD44 and CD90 (87%, 99% and 75% positive cells, respectively), but widely negative for CD73 and CD105 (1% and 6%, respectively). They also showed very low expression of the exclusion marker antigens CD14, CD34, CD45, CD79α and MHCII (2%, 4%, 5%, 0% and 3%, respectively). The immunophenotype remained similar after thawing and further expansion, albeit with overall decreased percentages of positive cells. An exemplary analysis of the MSCs used for treatment (i.e., after thawing and expansion) is shown in

Figure 1.

Animals and tendon lesions included

Fourteen equine patients, n = 7 per group reached the defined primary endpoint 12 months after treatment and were used for data analysis. Two horses in the control group did not present for the last examination 18 months after treatment, as decided by their owners. Out of the total 14 analyzed horses, two per group presented with acute lesions (onset of symptoms < 2 weeks) and five per group with early lesions (onset of symptoms between 2 weeks and 2 months). The duration of symptoms tended to be longer and lesions tended to be larger in the MSC group. Furthermore, the patients in the MSC group tended to be younger. However, these differences were small and none of them was significant (

Table 1).

Clinical findings

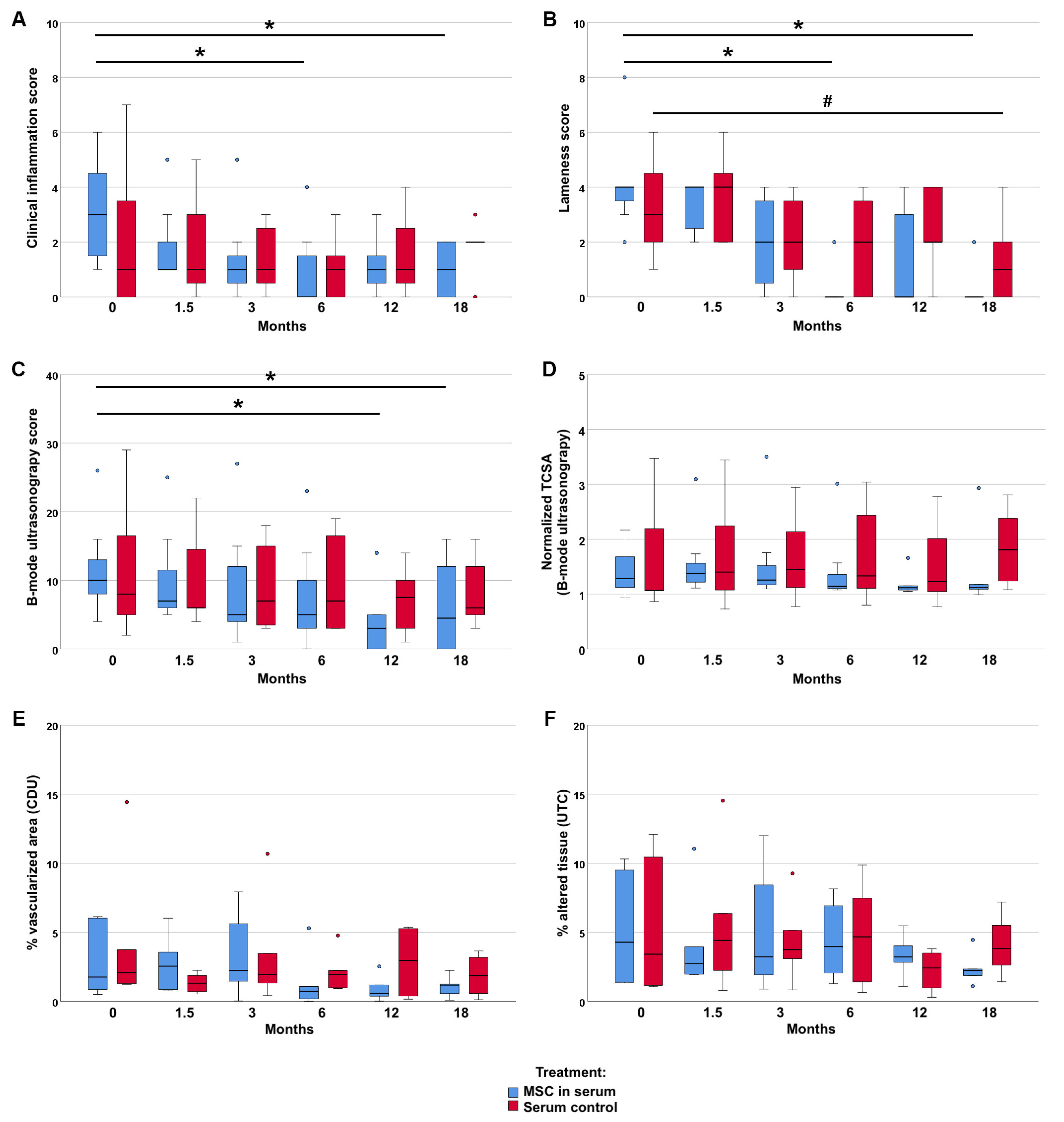

No severe adverse reactions to the treatment were reported. A transient increase of the lesion was observed in one horse in the MSC group, which still showed good tendon healing during the course of the study. The exercise schedule was adjusted in 9 cases due to lack of improvement or worsening in the clinical inflammation- and lameness scores. In one additional case, the level of exercise was reduced because the horse needed a ventral midline laparotomy (colic surgery) during the study period and could only be hand walked for the following 6 weeks.The clinical inflammation score showed a decrease over time only in the MSC group (p < 0.05 at 6 and 18 months, compared to the first examination). In contrast, no improvement of clinical signs of inflammation was observed in the control group. Similarly, gait disorder and weight bearing showed more improvement in the MSC group than in the control group: In the MSC group, the lameness score had significantly decreased by 6 and 18 months after treatment compared to the first examination (p < 0.05). In the control group, the decrease in lameness score was only significant after 18 months (p < 0.05) (

Figure 2). The lameness score difference between 6 months after treatment and before treatment revealed a significant improvement in the MSC group as compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (

Figure S1).

Diagnostic imaging findings

Imaging findings consistently supported the clinical findings. In B-mode ultrasonography, the improvement of the echogenicity and fibre alignment score was more evident in the MSC group (p < 0.05 at 12 and 18 months) than in the control group. B-mode ultrasonography also revealed that the mean TCSA remained widely constant in the MSC group, with a slight decrease over time, while it showed an increasing trend over time in the control group. Vascularization of the tendon, assessed by CDU, tended to be lower in the MSC group at the examinations after 6 months and later, but was transiently higher at the examination 6 weeks after treatment. The normalized percentage of altered tendon tissue, assessed by UTC, tended to decrease in the MSC group but not in the control group. However, differences in CDU and UTC were not significant. Data are presented in

Figure 2 and

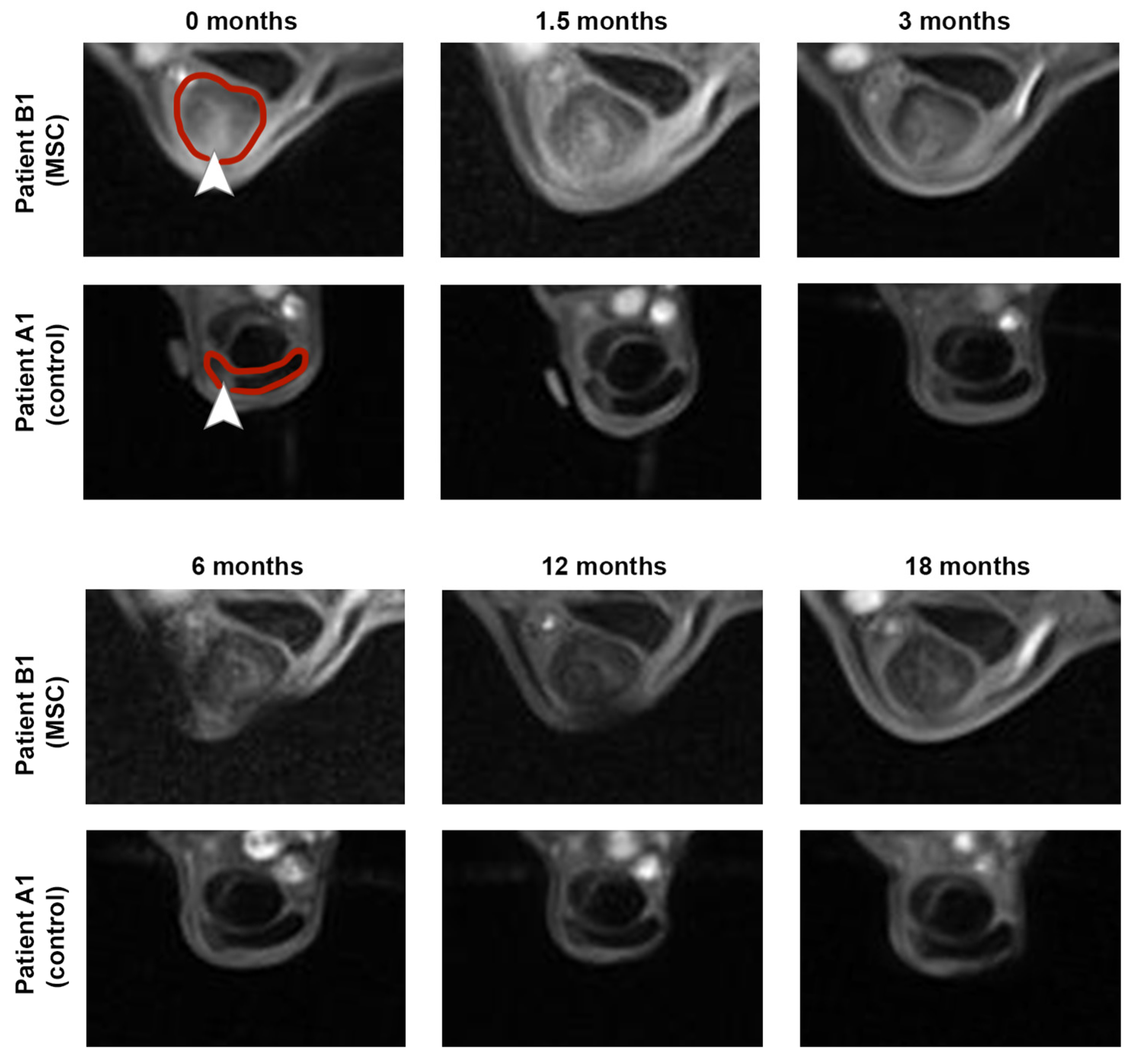

Figure S1. Exemplary MRI images documenting the long-term healing process in two non-re-injured patients are shown in

Figure 3.

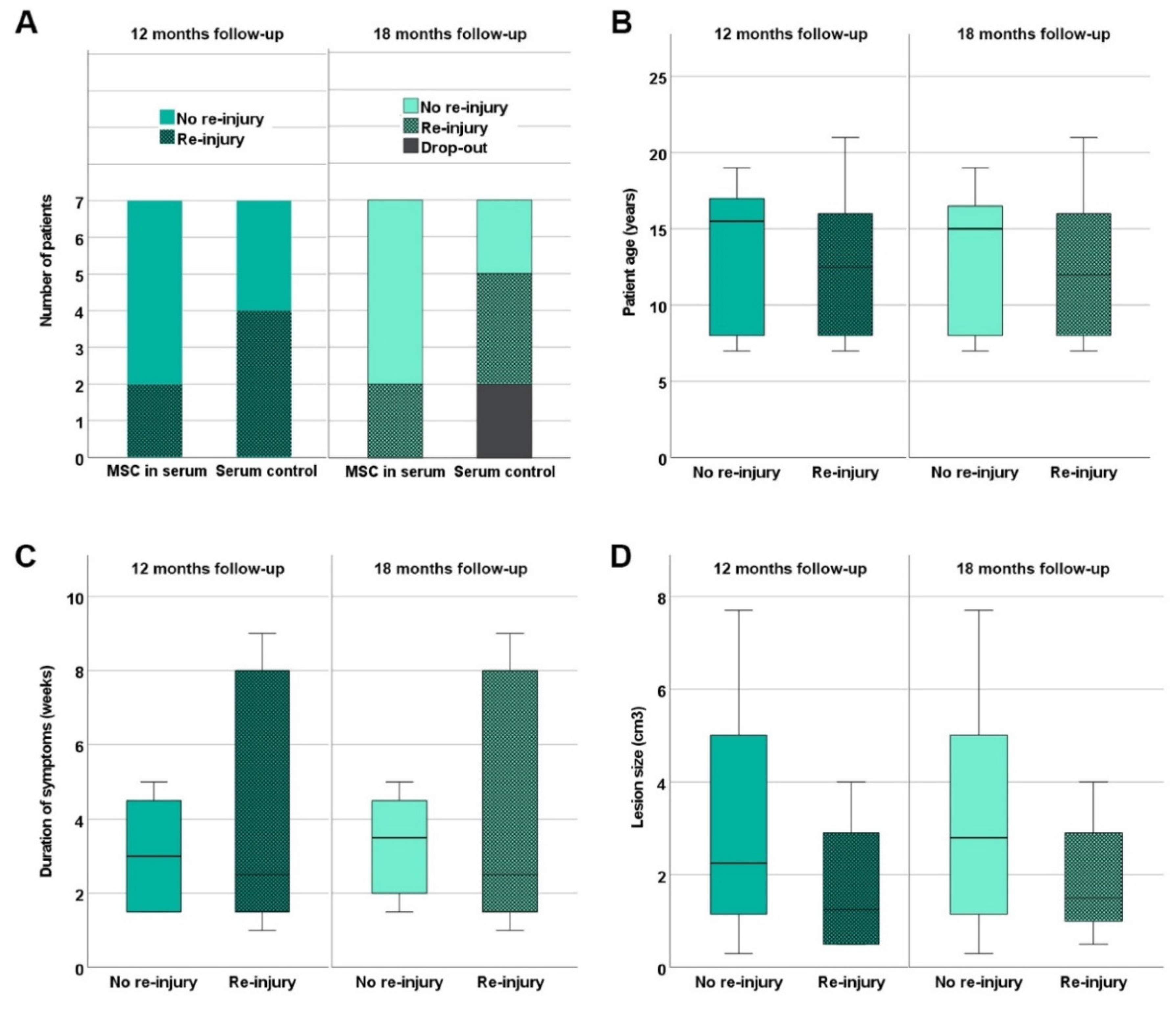

Re-injury rates and return to training

Five out of the 7 horses in the MSC group were back in training including gallop after 12 months of follow-up, without having suffered a re-injury. Moreover, these horses remained free of recurrence until the end of the follow-up at 18 months (

Figure 4). The two remaining horses in the MSC group, which included one horse that had already presented with a re-injury (animal B3), had suffered a re-injury (or recurrent re-injury, respectively) before the examination 12 months after treatment and the rehabilitation training had been reduced.

Re-injuries occurring until 12 and 18 months after treatment of early naturally occurring equine tendon lesions with either allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in serum or serum alone were documented. Panel A shows the numbers of patients without and with re-injury in the MSC and control groups. In the boxplot panels B – C, patients without and with re-injury are summarized irrespective of the treatment group, and their age (B), the duration of symptoms before inclusion in the study (C) and the tendon lesion size as determined by B-mode ultrasonography (D) are displayed. The differences observed between patients without and with re-injury were not significant (Mann-Whitney-U-test).

In the control group, 3 out of the 7 horses were back in training including gallop without having suffered a re-injury until 12 months after treatment. Two of them were still free of re-injuries 18 months after treatment; the third was not available for follow-up anymore. The remaining four horses in the control group had suffered a re-injury during the period of 12 months after treatment. Out of these, one horse presented with a second re-injury 18 months after treatment and one was not available for the 18 months examination anymore (

Figure 4).

Comparing the re-injured patients to the non-re-injured patients 12 or 18 months after treatment, no significant differences existed regarding patient age, duration of symptoms at presentation or lesion size (

Figure 4).

Discussion

Here, the results of a randomized, controlled, triple-blind pilot study on MSC treatment of equine tendon disease are presented. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first controlled study investigating the efficacy of allogeneic MSCs in naturally occurring tendon disease objectively and with long-term follow-up during rehabilitation training. Despite a relatively small number of cases included, our findings point to an improved clinical outcome after MSC treatment compared to serum treatment alone.

The MSCs used in the current study were obtained from the adipose tissue of a single healthy donor animal. Adipose tissue was chosen as MSC source based on the previous experimental studies of our groups [

9,

10,

12]. Allogeneic equine MSCs have repeatedly been reported to be clinically safe [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Nevertheless, their immunogenicity has been demonstrated and is receiving growing attention [

23,

25,

26,

27,

28], and repeated injections should be avoided based on the current data [

29]. Still, for single injections, the advantages of allogeneic MSC therapy are obvious, as a constant quality level of the cellular therapeutic agent can be ensured and off-the-shelf delivery shortens the time interval between first presentation and regenerative treatment. For MSC isolation and culture procedures, we integrated the advances made in the past years to obtain a safe and potent therapeutic agent. Firstly, xenogeneic substances were omitted as far as possible. Specifically, we completely avoided the use of fetal bovine serum, the remnants of which have by now been shown to induce immune targeting of the MSCs by the recipient, due to existing vaccination-induced anti-bovine titers [

30]. However, the components of the human xeno-free StemMACS™ MSC expansion medium supplement remain undisclosed and may contain human recombinant growth factors. An equivalent for the equine species is not available on the market and equine platelet-based alternatives [

31,

32] were still in their infancy when the current study was started [

33,

34]. Therefore, we considered the use of a human xeno-free medium, supplemented with equine serum, as the most reasonable choice in terms of MSC quality and safety. The cell isolation and culture procedures further involved the enzyme-free isolation of the cells by explant technique to avoid unnecessary manipulation [

35], and a depletion of CD14+ cells at first passaging. The latter was performed preventively as in past preliminary experiments, we had sometimes observed higher percentages of CD14+ cells than allowed [

36] after equine MSC culture in the StemMACS™ MSC expansion medium [

12]. Finally, as we had already performed in-depth in vivo studies on the MSC fate in equine tendon lesions in the past [

9,

22,

37] we avoided any cell labeling here in order to not manipulate the cells unnecessarily.

The equine patients were enrolled in the study at three different university hospitals, to increase the chance of recruiting a sufficient number of suitable cases within a reasonable time frame. Treatment and follow-up were always performed according to standardized procedures and by veterinarians specifically trained for the study, to minimize variation between locations. However, despite defined inclusion criteria, the horses recruited and their tendon lesions were a source of variation and heterogeneity. While differences in duration of symptoms and lesion size could be acknowledged by block randomization and by adapting the dosage, not all factors with potential impact on tendon healing could be leveled out actively. These include breed and intended use of the horse as well as the localization and extent of the tendon lesion within the metacarpal region. Furthermore, the compliance with the rehabilitation training schedule was subject of the interrogations during the follow-up examinations, but not specifically traceable. While these factors make the current study setting representative for clinical reality, they still represent a limitation of this study and likely contributed to the observed variation of the data.

As in previous experimental trials [

9,

10], the horses were either treated with adipose-derived MSCs suspended in horse serum or with horse serum alone, the latter serving as control group. This decision was made because we aimed to dissect the effect of the presence of MSCs alone and not the possible additional effects of the serum used as vehicle. Saline was not used as delivery vehicle or control, as it was previously shown that MSCs suspended in phosphate buffered saline had a lower viability as compared to MSCs suspended in bone marrow supernatant or plasma after the storage time necessary for transportation [

38]. Furthermore, blood products such as autologous conditioned serum display beneficial effects on tendon healing [

39], and we aimed to increase owner compliance by not including a fully untreated group.

The clinical follow-up demonstrated that signs of inflammation were significantly decreased and weight bearing, i.e. the lameness score, improved 6 and 18 months after the injection of MSCs, whereas little to no improvement was observed in the control group. The imaging findings showed similar tendencies, with a significant improvement of the B-mode ultrasonography score. Moreover, fewer re-injuries occurred in the MSC group. However, when comparing the two groups based on the difference in the respective parameters over time, differences were only significant for the lameness score 6 months after treatment, which is likely due to the variation within the data and the limited number of patients included in the current pilot study.

The improvement observed in tendon structure using B-mode ultrasonography corresponds to findings of previous experimental MSC studies with treatment of collagenase-induced or naturally occurring tendon lesions [

5,

6,

11]. In contrast, no superior effects of MSC treatment versus serum treatment alone had been observed in a previous experimental equine trial using autologous MSCs from adipose tissue in mechanically induced tendon lesions [

9]. This underlines the remarkable differences between different experimental models and clinical trials with regard to timing of treatment and the local lesion environment the MSCs are exposed to.

In this respect, it is important to attempt a comparison of the overall outcome, i.e. the re-injury rates, in the current study to previous clinical studies in larger cohorts but with historical controls instead of a randomized design [

2,

3]. In contrast to the aforementioned experimental studies, these investigations and the current study have in common that the included equine patients were returned to training and their intended use. In that context, the re-injury rates are a central parameter to evaluate the outcome. When attempting to calculate the re-injury rates despite the small numbers of cases included here, these amount to 29% (2 out of 7) in the MSC group and 57% (4 out of 7) in the control group. This corresponds well to the previous findings after MSC treatment of equine patients [

2,

3]. Thereby, the current- albeit preliminary- findings confirm the results of previous case studies with historical controls in a controlled clinical study design for the first time.

Considering the possible mode of action of MSC treatment of early tendon disease, the current findings, which include the reduction of clinical signs of inflammation, can be interpreted as long term signs of an effective immunomodulatory action [

40]. In tendons, this effect was shown to be mediated by macrophages [

41] and also appears to be associated with a transient increase in vascularization and perfusion. Increased blood perfusion for a limited period of time is a vital criterion of an effective inflammatory and early proliferative phase of wound healing, but a persistent increase in perfusion is considered as a sign of impaired tendon healing [

42,

43,

44]. While MSCs and especially those derived from adipose tissue are known to enhance vascularization per se [

45], it is critical for tendon healing that this effect is self-limiting. Indeed, in the current study, CDU signal had increased in the MSC group by 6 weeks after treatment, but then decreased to lower values than observed before treatment by 6 months and later. In the control group, a contrary trend was observed. This current finding correlates well with experimental results in horses showing an increased CDU signal within the first weeks after injection of autologous adipose derived MSCs [

18].

The early, transient increase in blood perfusion and the long-term decrease in inflammation could provide the basis for improved tissue regeneration. In tendons, the latter strongly depends on the restoration of the extracellular matrix composition and architecture, which is required for the biomechanical strength [

46] and thus for preventing re-injuries upon mechanical loading during training. To evaluate tissue regeneration, UTC belongs to the most objective modalities for longitudinal assessment of tendon lesions in horses [

47]. However, in the current study, UTC did not yield significant differences between groups or over time. This could be due to the high sensitivity of the UTC technique, which strongly reflected the variation between individual lesions already at the time before treatment. Focusing on selected imaging modalities and reducing the number of examinations would reduce the efforts for the follow-up of single patients and thereby facilitate recruitment and follow-up of larger cohorts.

Conclusions

The current pilot study consistently points to an improved tendon healing after MSC treatment, while using a randomized, controlled and triple-blind study design for the first time in this context. The findings strongly encourage a further advanced study, while providing ideal prerequisites for such future work.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Clinical and imaging parameters displayed as differences over time. Follow-up data obtained over a time period of 18 months after treatment of early naturally occurring equine tendon lesions with either allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in serum or serum alone. Clinical inflammation scores (A) and lameness scores (B) were obtained by blinded clinical examinations. The B-mode ultrasonography score (C), the normalized TSCA (tendon cross sectional area) (D), the % vascularized area (E) and the normalized % altered tissue (F) were obtained by blinded (semi)quantitative analysis of ultrasound-based imaging (CDU: Color Doppler ultrasonography; UTC: ultrasound tissue characterization). To compare the two treatment groups directly, the differences in the respective parameters over time were calculated for each time point (value at month x – value before treatment (month 0)), so that higher values reflect a worsening and lower values an improvement. The circles and rhombs mark the median values, the error bars the 95% confidence intervals (A – F). The difference in lameness score at 6 months (B) revealed a significant improvement in the MSC group as compared to the serum control group, as marked by the asterisk (p < 0.05; Mann-Whitney-U-test).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.B., J.B., FG; Methodology, J.B., W.B., FG; Software, J.B., L.W.V.; Validation, J.B., L.W.V., F.G.; Formal Analysis, J.B., L.W.V., F.G.; Investigation, L.W.V., S.S., C.H., J.B., F.G., Resources, J.B., W.B., F.G., Data Curation, J.B., L.W.V., Writing – Original Draft preparation, J.B., L.W.V., Writing – Review & Editing, J.B., L.W.V., S.S., C.H., W.B., F.G., Visualization, J.B., L.W.V., W.B., F.G., Supervision, J.B., W.B., F.G., Project Administration, J.B., F.G., Fund Acquisition, W.B., J.B., F.G.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; BR 3756/4-1, BU 3110/2-1, GE 2601/4-1)). The funding agency played no role in the design, analysis and reporting of the study. This Open Access publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) - 491094227 "Open Access Publication Funding" and the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the responsible animal welfare officers of the participating universities and the ethics committee of the responsible German federal state authority in accordance with the German Animal Welfare Law (Landesdirektion Leipzig, TV 34/13 and TV 28/18; Regierungspraesidium Giessen, Az. V54-19c 2015 h 01 GI 18/13GI 18/13 Nr. G 57/2017; Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety, Az. 33.19-42502-04-17/2673).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all owners of the included animals.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Christoph Engel, University of Leipzig, Germany, for his support with randomization and data analysis. The authors also thank Michaela Melzer and Carla Doll, Justus-Liebig-University Giessen, Germany, for their help with cell culture and image files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CDU |

color Doppler ultrasonography |

| MRI |

magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSC |

multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell |

| TCSA |

total cross-sectional area |

| UTC |

ultrasound tissue characterization |

References

- Smith RK, Korda M, Blunn GW, Goodship AE. Isolation and implantation of autologous equine mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow into the superficial digital flexor tendon as a potential novel treatment. Equine Vet J. 2003;35:99-102. [CrossRef]

- Burk J, Brehm W. Stem cell therapy of tendon injuries – clinical outcome in 98 cases. Pferdeheilkunde 2011;27:153-161. [CrossRef]

- Godwin EE, Young NJ, Dudhia J, Beamish IC, Smith RK. Implantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells demonstrates improved outcome in horses with overstrain injury of the superficial digital flexor tendon. Equine Vet J. 2012 Jan;44:25-32. [CrossRef]

- Beerts C, Suls M, Broeckx SY, Seys B, Vandenberghe A, Declercq J, Duchateau L, Vidal MA, Spaas JH. Tenogenically Induced Allogeneic Peripheral Blood Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Allogeneic Platelet-Rich Plasma: 2-Year Follow-up after Tendon or Ligament Treatment in Horses. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:158. [CrossRef]

- Schnabel LV, Lynch ME, van der Meulen MC, Yeager AE, Kornatowski MA, Nixon AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and insulin-like growth factor-I gene-enhanced mesenchymal stem cells improve structural aspects of healing in equine flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1392-8. [CrossRef]

- Crovace A, Lacitignola L, Rossi G, Francioso E. Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of autologous cultured bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and bone marrow mononucleated cells in collagenase-induced tendinitis of equine superficial digital flexor tendon. Vet Med Int. 2010;2010:250978. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Ade M, Badial PR, Álvarez LE, Yamada AL, Borges AS, Deffune E, Hussni CA, Garcia Alves AL. Equine tendonitis therapy using mesenchymal stem cells and platelet concentrates: a randomized controlled trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:85. [CrossRef]

- Depuydt E, Broeckx SY, Van Hecke L, Chiers K, Van Brantegem L, van Schie H, Beerts C, Spaas JH, Pille F, Martens A. The Evaluation of Equine Allogeneic Tenogenic Primed Mesenchymal Stem Cells in a Surgically Induced Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon Lesion Model. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:641441. [CrossRef]

- Geburek F, Roggel F, van Schie HTM, Beineke A, Estrada R, Weber K, Hellige M, Rohn K, Jagodzinski M, Welke B, Hurschler C, Conrad S, Skutella T, van de Lest C, van Weeren R, Stadler PM. Effect of single intralesional treatment of surgically induced equine superficial digital flexor tendon core lesions with adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: a controlled experimental trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:129. [CrossRef]

- Ahrberg AB, Horstmeier C, Berner D, Brehm W, Gittel C, Hillmann A, Josten C, Rossi G, Schubert S, Winter K, Burk J. Effects of mesenchymal stromal cells versus serum on tendon healing in a controlled experimental trial in an equine model. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:230. [CrossRef]

- Smith RK, Werling NJ, Dakin SG, Alam R, Goodship AE, Dudhia J. Beneficial effects of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in naturally occurring tendinopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75697.

- Schubert S, Brehm W, Hillmann A, Burk J. Serum-free human MSC medium supports consistency in human but not in equine adipose-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell culture. Cytometry A. 2018;93:60-72. [CrossRef]

- Paebst F, Piehler D, Brehm W, Heller S, Schroeck C, Tárnok A, Burk J. Comparative immunophenotyping of equine multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: an approach toward a standardized definition. Cytometry A. 2014;85:678-87. [CrossRef]

- Smith RK, McIlwraith CW. Consensus on equine tendon disease: building on the 2007 Havemeyer symposium. Equine Vet J. 2012;44:2-6. [CrossRef]

- Geburek F, Gaus M, van Schie HT, Rohn K, Stadler PM. Effect of intralesional platelet-rich plasma (PRP) treatment on clinical and ultrasonographic parameters in equine naturally occurring superficial digital flexor tendinopathies - a randomized prospective controlled clinical trial. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12:191. [CrossRef]

- Genovese RL, Rantanen NW, Hauser ML, Simpson BS. Diagnostic ultrasonography of equine limbs. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 1986;2:145-226. [CrossRef]

- Rantanen NW, Jorgensen JS, Genovese RL. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the equine limb: technique. In: Ross MW, Dyson SJ, editors. Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in the Horse. 1st ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2003. p. 166–88.

- Conze P, van Schie HT, van Weeren R, Staszyk C, Conrad S, Skutella T, Hopster K, Rohn K, Stadler P, Geburek F. Effect of autologous adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells on neovascularization of artificial equine tendon lesions. Regen Med. 2014;9:743-57. [CrossRef]

- Berner D, Brehm W, Gerlach K, Offhaus J, Scharner D, Burk J. Variation in the MRI signal intensity of naturally occurring equine superficial digital flexor tendinopathies over a 12-month period. Vet Rec. 2020;187:e53. [CrossRef]

- Carrade DD, Affolter VK, Outerbridge CA, Watson JL, Galuppo LD, Buerchler S, Kumar V, Walker NJ, Borjesson DL. Intradermal injections of equine allogeneic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells are well tolerated and do not elicit immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:1180-92. [CrossRef]

- Kol A, Wood JA, Carrade Holt DD, Gillette JA, Bohannon-Worsley LK, Puchalski SM, Walker NJ, Clark KC, Watson JL, Borjesson DL. Multiple intravenous injections of allogeneic equine mesenchymal stem cells do not induce a systemic inflammatory response but do alter lymphocyte subsets in healthy horses. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:73. [CrossRef]

- Berner D, Brehm W, Gerlach K, Gittel C, Offhaus J, Paebst F, Scharner D, Burk J. Longitudinal Cell Tracking and Simultaneous Monitoring of Tissue Regeneration after Cell Treatment of Natural Tendon Disease by Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:1207190. [CrossRef]

- Williams LB, Co C, Koenig JB, Tse C, Lindsay E, Koch TG. Response to Intravenous Allogeneic Equine Cord Blood-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Administered from Chilled or Frozen State in Serum and Protein-Free Media. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:56. [CrossRef]

- Brandão JS, Alvarenga ML, Pfeifer JPH, Dos Santos VH, Fonseca-Alves CE, Rodrigues M, Laufer-Amorim R, Castillo JAL, Alves ALG. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in healthy equine superficial digital flexor tendon: A study of the local inflammatory response. Res Vet Sci. 2018;118:423-430. [CrossRef]

- Pezzanite LM, Fortier LA, Antczak DF, Cassano JM, Brosnahan MM, Miller D, Schnabel LV. Equine allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells elicit antibody responses in vivo. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:54. [CrossRef]

- Owens SD, Kol A, Walker NJ, Borjesson DL. Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cell Treatment Induces Specific Alloantibodies in Horses. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:5830103. [CrossRef]

- Berglund AK, Schnabel LV. Allogeneic major histocompatibility complex-mismatched equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells are targeted for death by cytotoxic anti-major histocompatibility complex antibodies. Equine Vet J. 2017;49:539-544. [CrossRef]

- Barrachina L, Cequier A, Romero A, Vitoria A, Zaragoza P, Vázquez FJ, Rodellar C. Allo-antibody production after intraarticular administration of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in an equine osteoarthritis model: effect of repeated administration, MSC inflammatory stimulation, and equine leukocyte antigen (ELA) compatibility. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:52. [CrossRef]

- Joswig AJ, Mitchell A, Cummings KJ, Levine GJ, Gregory CA, Smith R 3rd, Watts AE. Repeated intra-articular injection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells causes an adverse response compared to autologous cells in the equine model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:42.

- Rowland AL, Burns ME, Levine GJ, Watts AE. Preparation Technique Affects Recipient Immune Targeting of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:724041. [CrossRef]

- Naskou MC, Sumner SM, Chocallo A, Kemelmakher H, Thoresen M, Copland I, Galipeau J, Peroni JF. Platelet lysate as a novel serum-free media supplement for the culture of equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:75. [CrossRef]

- Hagen A, Lehmann H, Aurich S, Bauer N, Melzer M, Moellerberndt J, Patané V, Schnabel CL, Burk J. Scalable Production of Equine Platelet Lysate for Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Culture. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;8:613621. [CrossRef]

- Seo JP, Tsuzuki N, Haneda S, Yamada K, Furuoka H, Tabata Y, Sasaki N. Comparison of allogeneic platelet lysate and fetal bovine serum for in vitro expansion of equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Res Vet Sci. 2013;95:693-8. [CrossRef]

- Russell KA, Koch TG. Equine platelet lysate as an alternative to fetal bovine serum in equine mesenchymal stromal cell culture - too much of a good thing? Equine Vet J. 2016;48:261-4.

- Explant culture: An advantageous method for isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from human tissues. Hendijani F. Cell Prolif. 2017;50:e12334.

- Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop Dj, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315-7.

- Burk J, Berner D, Brehm W, Hillmann A, Horstmeier C, Josten C, Paebst F, Rossi G, Schubert S, Ahrberg AB. Long-Term Cell Tracking Following Local Injection of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in the Equine Model of Induced Tendon Disease. Cell Transplant. 2016 Dec 13;25(12):2199-2211. [CrossRef]

- Espina M, Jülke H, Brehm W, Ribitsch I, Winter K, Delling U. Evaluation of transport conditions for autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for therapeutic application in horses. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1773. [CrossRef]

- Geburek F, Lietzau M, Beineke A, Rohn K, Stadler PM. Effect of a single injection of autologous conditioned serum (ACS) on tendon healing in equine naturally occurring tendinopathies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:126. [CrossRef]

- Peroni JF, Borjesson DL. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of stem cells. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2011;27:351–62. [CrossRef]

- Shen H, Kormpakis I, Havlioglu N, Linderman SW, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Erickson IE, Zarembinski T, Silva MJ, Gelberman RH, Thomopoulos S. The effect of mesenchymal stromal cell sheets on the inflammatory stage of flexor tendon healing. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:144. [CrossRef]

- Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Ultrasound guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic Achilles tendinosis: pilot study of a new treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:173-7. [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen M, Ohberg L, Johnston C, Alfredson H. Neovascularisation in chronic tendon injuries detected with colour Doppler ultrasound in horse and man: implications for research and treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:505-8. [CrossRef]

- Hatazoe T, Endo Y, Iwamoto Y, Korosue K, Kuroda T, Inoue S, Murata D, Hobo S, Misumi K. A study of the distribution of color Doppler flows in the superficial digital flexor tendon of young Thoroughbreds during their training periods. J Equine Sci. 2015;26:99-104. [CrossRef]

- Ceserani V, Ferri A, Berenzi A, Benetti A, Ciusani E, Pascucci L, Bazzucchi C, Coccè V, Bonomi A, Pessina A, Ghezzi E, Zeira O, Ceccarelli P, Versari S, Tremolada C, Alessandri G. Angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties of micro-fragmented fat tissue and its derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Vasc Cell. 2016;8:3. [CrossRef]

- Hammer N, Huster D, Fritsch S, Hädrich C, Koch H, Schmidt P, Sichting F, Wagner MF, Boldt A. Do cells contribute to tendon and ligament biomechanics? PLoS One. 2014;9:e105037.

- Ehrle A, Lilge S, Clegg PD, Maddox TW. Equine flexor tendon imaging part 1: Recent developments in ultrasonography, with focus on the superficial digital flexor tendon. Vet J. 2021;278:105764. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).