Submitted:

20 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- In the first section, we present essential concepts to understand plant meristems. We introduce the concept of stem cells and compare the stem cell niche of RAM and SAM. We emphasize the importance of plant life cycles, as this concept gives rise to SAM evolution theories.

- Then, the meristem shape is analyzed throughout phylogeny. This section offers a morphological description of SAM across plant evolution. Given the extensive literature on SAM morphology, it provides perspectives on the differences in SAM between clades.

- We provide a comprehensive review of the regulatory and maintenance mechanisms in the SAM. This section focuses on the regulatory loops described for angiosperms and the conserved elements across clades.

- Taking advantage of single-cell transcriptomics to understand SAM, this section delves into the research of single-cell transcriptomics and single-nucleus transcriptomics on SAM. We describe key studies and discuss their findings.

2. Evolutionary Origin of the Meristem

2.1. The Concept of Stem Cells

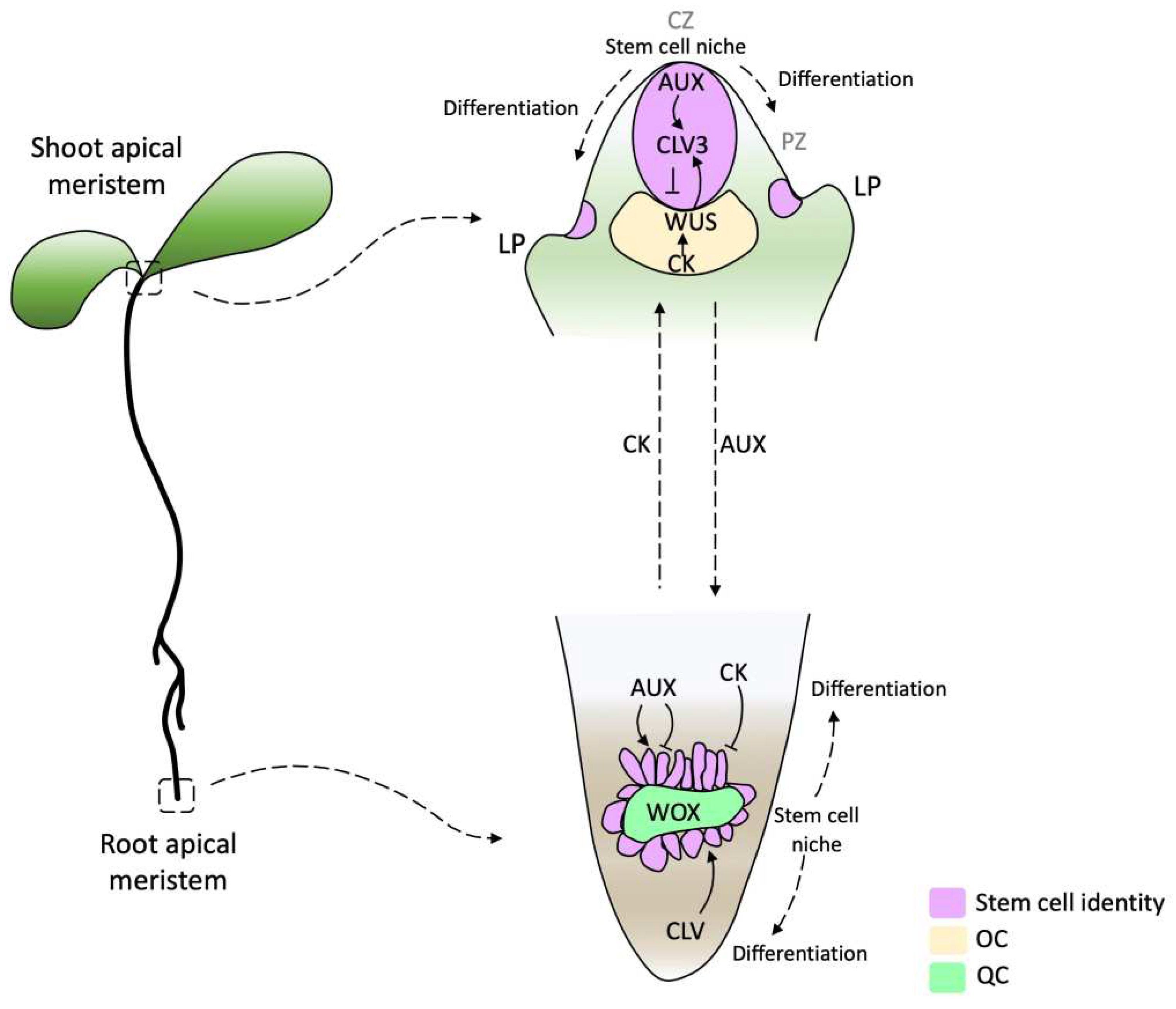

2.2. SAM and RAM

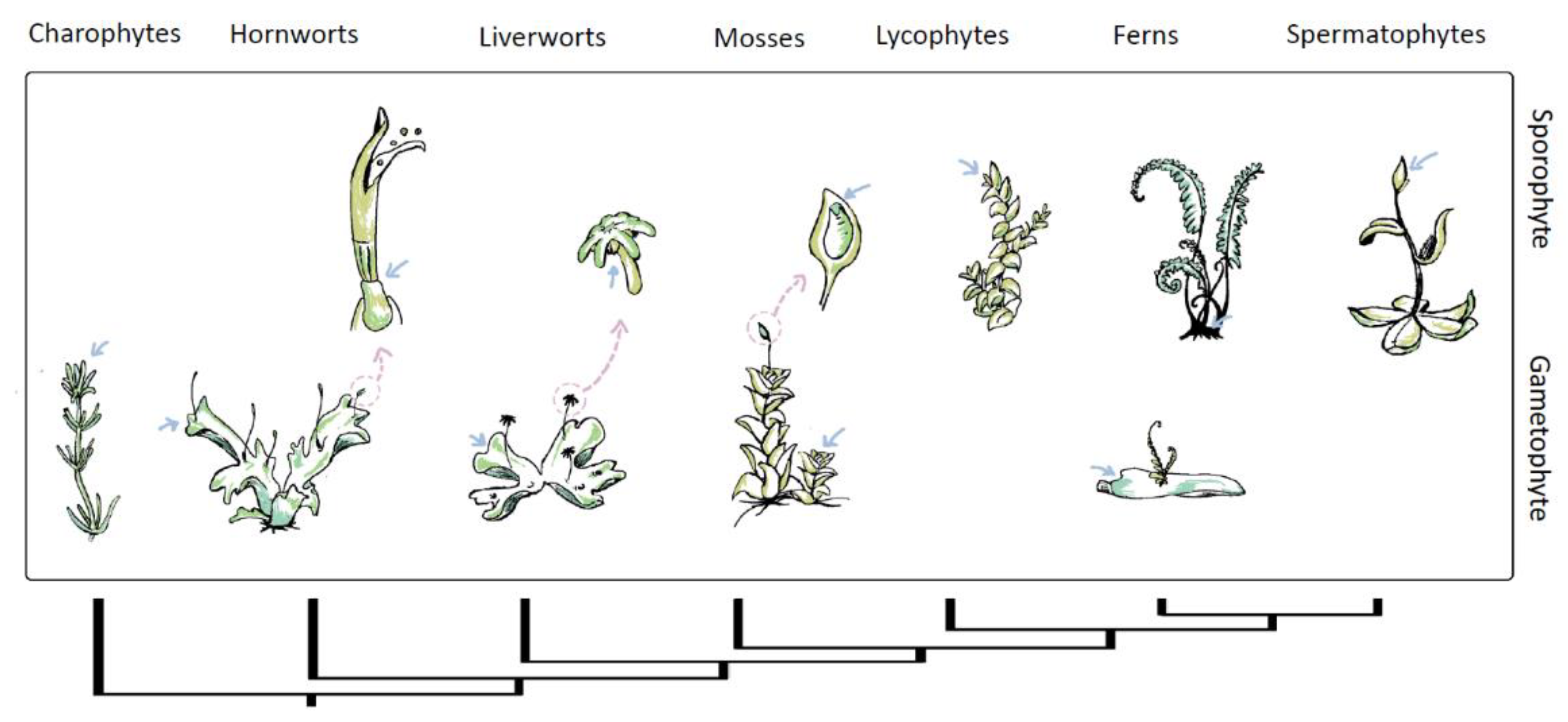

2.3. Apical Metistem of Gametophyte and Sporophyte

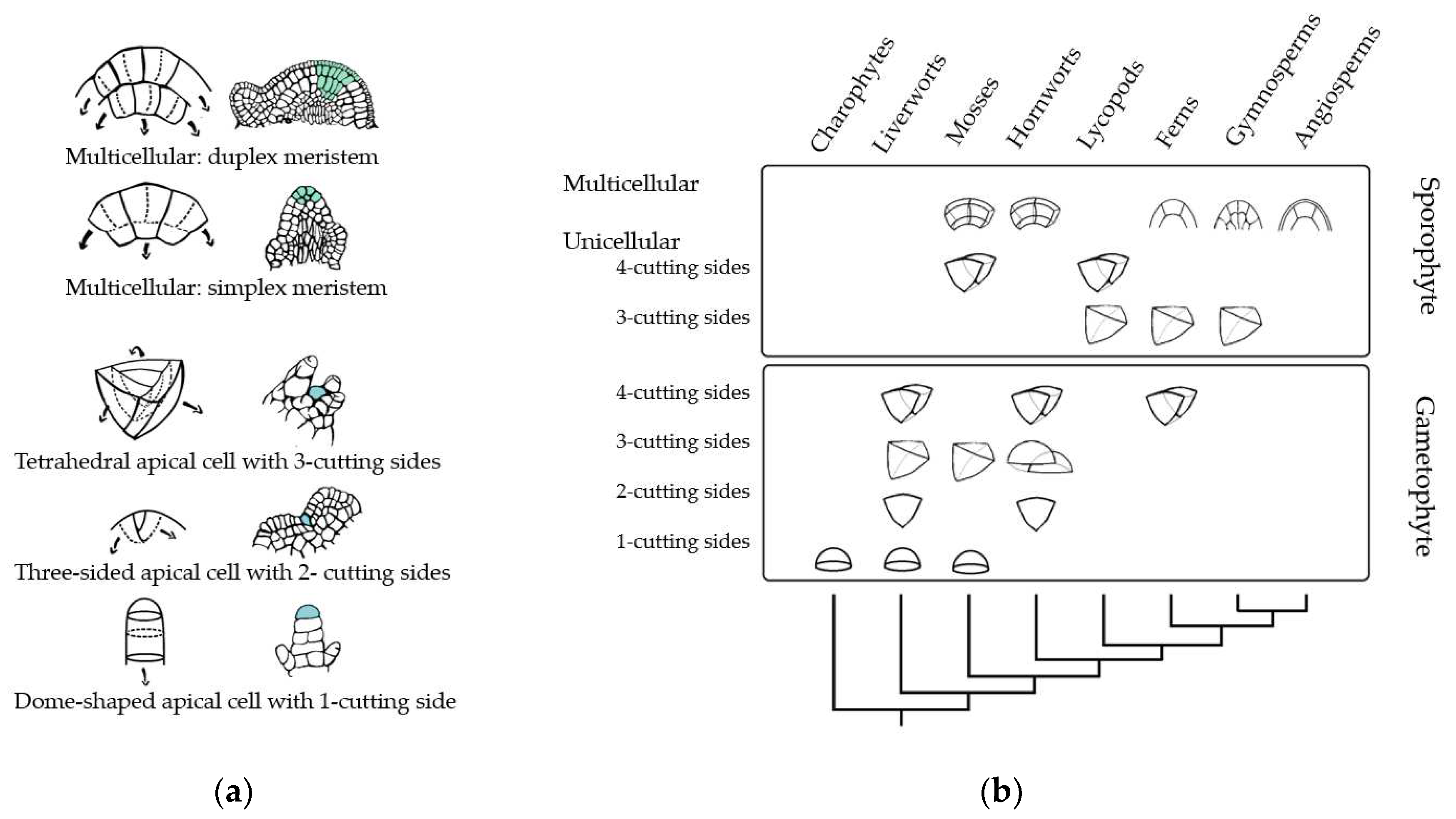

3. Meristem Shape Throughout Phylogeny

3.1. Algae

3.2. Bryophytes

3.4. Tracheophytes

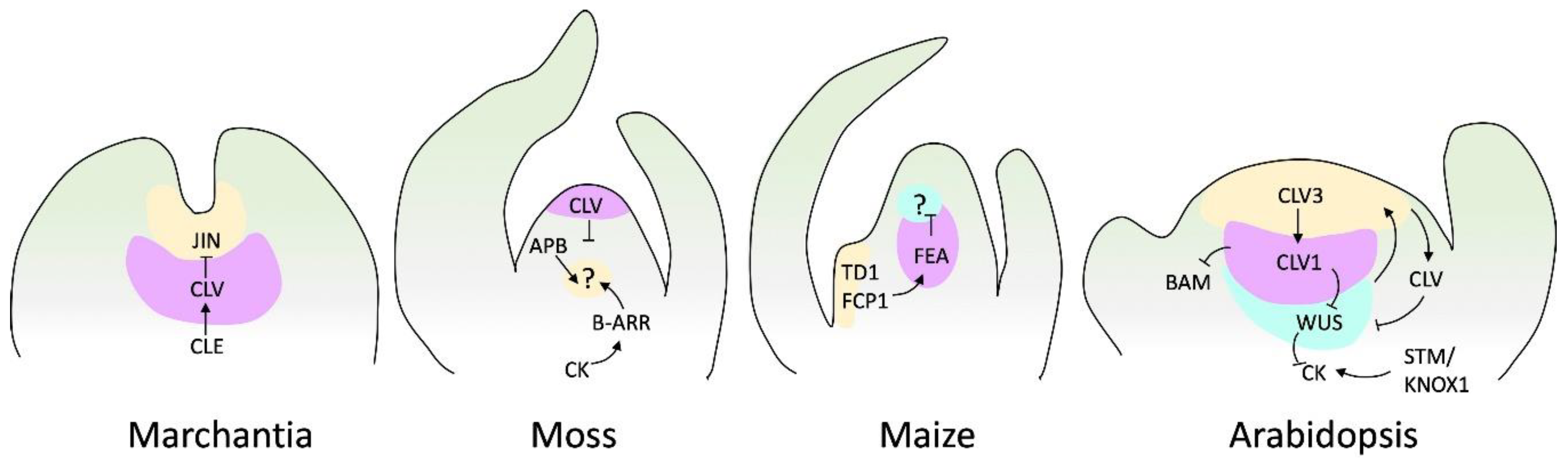

4. Shoot Apical Meristem Regulation and Maintenance

4.1. The Regulatory Model: Angiosperms

4.2. SAM TFs Conserved Throughout Evolution

KNOX TFs

MADS TFs

AP2/ERF TFs

5. Taking Advantage of Single-Cell Transcriptomics to Understand SAM

6. Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, J.A.H.; Jones, A.; Godin, C.; Traas, J. Systems Analysis of Shoot Apical Meristem Growth and Development: Integrating Hormonal and Mechanical Signaling. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3907–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jill Harrison, C. Development and Genetics in the Evolution of Land Plant Body Plans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. The Evolution of the Shoot Apical Meristem from a Gene Expression Perspective. New Phytologist 2015, 207, 486–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafi, G.; Florentin, A.; Ransbotyn, V.; Morgenstern, Y. The Stem Cell State in Plant Development and in Response to Stress. Front Plant Sci 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, I.; Labib, G.; Melchers, G. Regeneration of Whole Plants from Isolated Mesophyll Protoplasts of Tobacco. Naturwissenschaften 1971, 58, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehér, A. Callus, Dedifferentiation, Totipotency, Somatic Embryogenesis: What These Terms Mean in the Era of Molecular Plant Biology? Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 442509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, K.; Offringa, R.; Sharma, V.K.; Kieft, H.; Ouellet, T.; Zhang, L.; Hattori, J.; Liu, C.M.; Van Lammeren, A.A.M.; Miki, B.L.A.; et al. Ectopic Expression of BABY BOOM Triggers a Conversion from Vegetative to Embryonic Growth. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Du, Q.; Tian, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, Y. Stochastic Gene Expression Drives Mesophyll Protoplast Regeneration. Sci Adv 2021, 7, 8466–8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.; Kim, H.K.; Bae, S.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, Y.J.; Seo, P.J. Transcriptome Comparison between Pluripotent and Non-Pluripotent Calli Derived from Mature Rice Seeds. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.A.; Moan, E.I.; Medford, J.I.; Barton, M.K. A Member of the KNOTTED Class of Homeodomain Proteins Encoded by the STM Gene of Arabidopsis. Nature 1996, 379, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, Y.; Simon, R. Plant Primary Meristems: Shared Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2010, 13, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seago, J.L.; Fernando, D.D. Anatomical Aspects of Angiosperm Root Evolution. Ann Bot 2013, 112, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haecker, A.; Groß-Hardt, R.; Geiges, B.; Sarkar, A.; Breuninger, H.; Herrmann, M.; Laux, T. Expression Dynamics of WOX Genes Mark Cell Fate Decisions during Early Embryonic Patterning in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Development 2004, 131, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, T.; Scheres, B. Root Development-Two Meristems for the Price of One? Curr Top Dev Biol 2010, 91, 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.K.; Luijten, M.; Miyashima, S.; Lenhard, M.; Hashimoto, T.; Nakajima, K.; Scheres, B.; Heidstra, R.; Laux, T. Conserved Factors Regulate Signalling in Arabidopsis Thaliana Shoot and Root Stem Cell Organizers. Nature 2007, 446, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skylar, A.; Wu, X. Regulation of Meristem Size by Cytokinin SignalingF. J Integr Plant Biol 2011, 53, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greb, T.; Lohmann, J.U. Plant Stem Cells. Curr Biol 2016, 26, R816–R821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mähönen, A.P.; Ten Tusscher, K.; Siligato, R.; Smetana, O.; Díaz-Triviño, S.; Salojärvi, J.; Wachsman, G.; Prasad, K.; Heidstra, R.; Scheres, B. PLETHORA Gradient Formation Mechanism Separates Auxin Responses. Nature 2014, 515, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Ioio, R.; Galinha, C.; Fletcher, A.G.; Grigg, S.P.; Molnar, A.; Willemsen, V.; Scheres, B.; Sabatini, S.; Baulcombe, D.; Maini, P.K.; et al. A PHABULOSA/Cytokinin Feedback Loop Controls Root Growth in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 2012, 22, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, G.E.; Bishopp, A.; Kieber, J.J. The Yin-Yang of Hormones: Cytokinin and Auxin Interactions in Plant Development. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, W.E.; Moore, R.C.; Purugganan, M.D. The Evolution of Plant Development. Am J Bot 2004, 91, 1726–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, A.J.; Dolan, L. Stepwise and Independent Origins of Roots among Land Plants. Nature 2018, 561, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Xu, L. Recruitment of IC-WOX Genes in Root Evolution. Trends Plant Sci 2018, 23, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinami, R.; Yamada, T.; Imaichi, R. Root Apical Meristem Diversity and the Origin of Roots: Insights from Extant Lycophytes. J Plant Res 2020, 133, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Schiefelbein, J. Conserved Gene Expression Programs in Developing Roots from Diverse Plants. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2119–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augstein, F.; Carlsbecker, A. Getting to the Roots: A Developmental Genetic View of Root Anatomy and Function from Arabidopsis to Lycophytes. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 411407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leebens-Mack, J.H.; Barker, M.S.; Carpenter, E.J.; Deyholos, M.K.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Graham, S.W.; Grosse, I.; Li, Z.; Melkonian, M.; Mirarab, S.; et al. One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes and the Phylogenomics of Green Plants. Nature 2019, 574, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Shivhare, D.; Hansen, B.O.; Pasha, A.; Esteban, E.; Provart, N.J.; Kragler, F.; Fernie, A.; Tohge, T.; Mutwil, M. Expression Atlas of Selaginella Moellendorffii Provides Insights into the Evolution of Vasculature, Secondary Metabolism, and Roots. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.H.; Liu, Y.B.; Zhang, X.S. Auxin-Cytokinin Interaction Regulates Meristem Development. Mol Plant 2011, 4, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zeng, J.; Wu, H.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z. A Molecular Framework for Auxin-Controlled Homeostasis of Shoot Stem Cells in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 2018, 11, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.E. Am Erican Naturalist The American Society Of Naturalists Haploid And Diploid Generations’; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, V.A. Shoot Apical Meristems and Floral Patterning: An Evolutionary Perspective. Trends Plant Sci 1999, 4, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligrone, R.; Duckett, J.G.; Renzaglia, K.S. The Origin of the Sporophyte Shoot in Land Plants: A Bryological Perspective. Ann Bot 2012, 110, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, Y.; Kyozuka, J. Fundamental Mechanisms of the Stem Cell Regulation in Land Plants: Lesson from Shoot Apical Cells in Bryophytes. Plant Mol Biol 2021, 107, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yan, A.; McAdam, S.A.M.; Banks, J.A.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y. Timing of Meristem Initiation and Maintenance Determines the Morphology of Fern Gametophytes. J Exp Bot 2021, 72, 6990–7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haig, D. Homologous Versus Antithetic Alternation of Generations and the Origin of Sporophytes. The Botanical Review 2008, 74, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, K.J.; Kutschera, U. The Evolution of the Land Plant Life Cycle. New Phytologist 2010, 185, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennici, A. Origin and Early Evolution of Land Plants Problems and Considerations; Volume 1.

- Hemsley, A.R. The origin of the land plant sporophyte: An interpolational scenario. Biological Reviews 1994, 69, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenrick, P. Alternation of generations in land plants: New phylogenetic and palaeobotanical evidence. Biological Reviews 1994, 69, 293–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.J. Auxin Transport in the Evolution of Branching Forms. New Phytologist 2017, 215, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.H.; Scanlon, M.J. Transcriptomic Evidence for the Evolution of Shoot Meristem Function in Sporophyte-Dominant Land Plants through Concerted Selection of Ancestral Gametophytic and Sporophytic Genetic Programs. Mol Biol Evol 2015, 32, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngstrom, C.E.; Geadelmann, L.F.; Irish, E.E.; Cheng, C.L. A Fern WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX Gene Functions in Both Gametophyte and Sporophyte Generations. BMC Plant Biol 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popham, R.A. principal types of vegetative shoot apex organization in vascular plants 1. Ohio J Sci 1951, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Renzaglia, K.S. A Comparative Developmental Investigation of the Gametophyte Generation in the Metzgeriales (Hepatophyta). 1982, 253. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, R.W. Apical Cells As Meristems; KluwerAcademic Publishers, 1993; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama, R.; Naramoto, S. Apical Stem Cells Sustaining Prosperous Evolution of Land Plants. J Plant Res 2020, 133, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Renzaglia, K. Phylogeny and Diversification of Bryophytes. Am J Bot 2004, 91, 1557–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, K.J.; Wayne, R.; Benítez, M.; Newman, S.A. Polarity, Planes of Cell Division, and the Evolution of Plant Multicellularity. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.D.; Mattox, K.R. Some Aspects of Mitosis in Primitive Green Algae: Phylogeny and Function. Biosystems 1975, 7, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.E.; Cook, M.E.; Busse, J.S. The Origin of Plants: Body Plan Changes Contributing to a Major Evolutionary Radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 4535–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umen, J.G. Green Algae and the Origins of Multicellularity in the Plant Kingdom. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.E.; Cook, M.E.; Busse, J.S. The Origin of Plants: Body Plan Changes Contributing to a Major Evolutionary Radiation; 2000; Volume 97. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, L.A. Unravelling 3D Growth in the Moss Physcomitrium Patens. Essays Biochem 2022, 66, 769–779. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L.E. Coleochaete And The Origin Of Land Plants. Am J Bot 1984, 71, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttick, M.N.; Morris, J.L.; Williams, T.A.; Cox, C.J.; Edwards, D.; Kenrick, P.; Pressel, S.; Wellman, C.H.; Schneider, H.; Pisani, D.; et al. The Interrelationships of Land Plants and the Nature of the Ancestral Embryophyte. Current Biology 2018, 28, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, T.; Wolf, P.G.; Kugita, M.; Sinclair, R.B.; Sugita, M.; Sugiura, C.; Wakasugi, T.; Yamada, K.; Yoshinaga, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; et al. Chloroplast Phylogeny Indicates That Bryophytes Are Monophyletic. Mol Biol Evol 2004, 21, 1813–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzaglia, K.S.; Garbary, D.J. Motile Gametes of Land Plants: Diversity, Development, and Evolution. Critical reviews in plant sciences 2010, 20, 107–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.H. The Structure & Development of the Mosses & Ferns (Archegoniatae); Macmillan, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Tomescu, A.M.F.; Wyatt, S.E.; Hasebe, M.; Rothwell, G.W. Early Evolution of the Vascular Plant Body Plan — the Missing Mechanisms. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2014, 17, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligrone, R.; Duckett, J.G.; Renzaglia, K.S. Conducting Tissues and Phyletic Relationships of Bryophytes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2000, 355, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, K.; Nishiyama, T.; Deguchi, H.; Hasebe, M. Class 1 KNOX Genes Are Not Involved in Shoot Development in the Moss Physcomitrella Patens but Do Function in Sporophyte Development. Evol Dev 2008, 10, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Akiyama, H. Interpolation Hypothesis for Origin of the Vegetative Sporophyte of Land Plants; 2005; Volume 54. [Google Scholar]

- Renzaglia, K.S.; Schuette, S.; Duff, R.J.; Ligrone, R.; Shaw, A.J.; Mishler, B.D.; Duckett, J.G. Bryophyte Phylogeny: Advancing the Molecular and Morphological Frontiers; 2007; Volume 110. [Google Scholar]

- Solly, J.E.; Cunniffe, N.J.; Harrison, C.J. Regional Growth Rate Differences Specified by Apical Notch Activities Regulate Liverwort Thallus Shape. Curr Biol 2017, 27, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzaglia, A.; Wehman, P.; Schutz, R.; Karan, O. Use of Cue Redundancy and Positive Reinforcement to Accelerate Production in Two Profoundly Retarded Workers. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 1978, 17, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esau, K. Plant Anatomy. Plant Anatomy 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, E.M.; Corson, G.E. The Shoot Apex in Seed Plants. The Botanical Review 1971, 37, 143–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, I.V. Pattern in the Meristems of Vascular Plants: III. Pursuing the Patterns in the Apical Meristem Where No Cell Is a Permanent Cell*. Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Botany 1965, 59, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaichi, R.; Hiratsuka, R. Evolution of Shoot Apical Meristem Structures in Vascular Plants with Respect to Plasmodesmatal Network. Am J Bot 2007, 94, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouracre, J.P.; Harrison, C.J. How Was Apical Growth Regulated in the Ancestral Land Plant? Insights from the Development of Non-Seed Plants. Plant Physiol 2022, 190, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, V.; Nemec Venza, Z.; Harrison, C.J. What Can Lycophytes Teach Us about Plant Evolution and Development? Modern Perspectives on an Ancient Lineage. Evol Dev 2021, 23, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.J.; Rezvani, M.; Langdale, J.A. Growth from Two Transient Apical Initials in the Meristem of Selaginella Kraussiana. Development 2007, 134, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.S.; Drinnan, A.N. The Developmental Pattern of Shoot Apices in Selaginella Kraussiana (Kunze) a. Braun. Int J Plant Sci 2009, 170, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, B.A.; Vasco, A. Bringing the Multicellular Fern Meristem into Focus. New Phytologist 2016, 210, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.A.; Turner, M.D. Anatomy and Development of the Fern Sporophyte. The Botanical Review 1995, 61, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, E.M. The Structure and Development of the Shoot Apex in Certain Woody Ranales; 1950; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, S.; Townsley, B.; Sinha, N. L1 Division and Differentiation Patterns Influence Shoot Apical Meristem Maintenance. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, N.; Hake, S. Mutant Characters of Knotted Maize Leaves Are Determined in the Innermost Tissue Layers. Dev Biol 1990, 141, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, E.M.; Wetmore, R.H. APICAL MERISTEMS OF VEGETATIVE SHOOTS AND STROBILI IN CERTAIN GYMNOSPERMS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1957, 43, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.K. Twenty Years on: The Inner Workings of the Shoot Apical Meristem, a Developmental Dynamo. Dev Biol 2010, 341, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebrom, T.H. A Growing Stem Inhibits Bud Outgrowth – The Overlooked Theory of Apical Dominance. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 309506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimann, K.V. Auxins And The Inhibition Of Plant Growth.

- Went, F.W. Auxin, the Plant Growth-Hormone. Review 1935, 1, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussex, I.M.; Kerk, N.M. The Evolution of Plant Architecture. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2001, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, M.G. Execution of the Auxin Replacement Apical Dominance Experiment in Temperate Woody Species. Am J Bot 2000, 87, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norstog, K.; Nicholls, T.J. The Biology of the Cycads. The Biology of the Cycads 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.A.; Beveridge, C.A.; Snowden, K.C. 5 Reevaluating Concepts of Apical Dominance and the Control of Axillary Bud Outgrowth. Curr Top Dev Biol 1998, 44, 127–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Auxin Biosynthesis and Its Role in Plant Development. Annual review of plant biology 2010, 61, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, P.; Rafii, M.Y.; Maziah, M.; Abdullah, S.N.A.; Hanafi, M.M.; Latif, M.A.; Rashid, A.A.; Sahebi, M. Understanding the Shoot Apical Meristem Regulation: A Study of the Phytohormones, Auxin and Cytokinin, in Rice. Mech Dev 2015, 135, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoof, H.; Lenhard, M.; Haecker, A.; Mayer, K.F.X.; Jürgens, G.; Laux, T. The Stem Cell Population of Arabidopsis Shoot Meristems Is Maintained by a Regulatory Loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL Genes. Cell 2000, 100, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laux, T.; Mayer, K.F.X.; Berger, J.; Jürgens, G. The WUSCHEL Gene Is Required for Shoot and Floral Meristem Integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 1996, 122, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrizzi, K.; Moussian, B.; Haecker, A.; Levin, J.Z.; Laux, T. The SHOOT MERISTEMLESS Gene Is Required for Maintenance of Undifferentiated Cells in Arabidopsis Shoot and Floral Meristems and Acts at a Different Regulatory Level than the Meristem Genes WUSCHEL and ZWILLE. The Plant Journal 1996, 10, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, P.; Sun, M.X. Comparative Analysis of WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox Genes Revealed Their Parent-of-Origin and Cell Type-Specific Expression Pattern during Early Embryogenesis in Tobacco. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 337885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aida, M.; Tasaka, M. Genetic Control of Shoot Organ Boundaries. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2006, 9, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Putting Genes on the Map: Spatial Transcriptomics of the Maize Shoot Apical Meristem. Plant Physiol 2022, 188, 1931–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimotohno, A.; Scheres, B. Topology of Regulatory Networks That Guide Plant Meristem Activity: Similarities and Differences. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2019, 51, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, S.K.; Bowman, J.L. The Ancestral Developmental Tool Kit of Land Plants. Int J Plant Sci 2007, 168, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierschke, T.; Flores-Sandoval, E.; Rast-Somssich, M.I.; Althoff, F.; Zachgo, S.; Bowman, J.L. Gamete Expression of Tale Class Hd Genes Activates the Diploid Sporophyte Program in Marchantia Polymorpha. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisanaga, T.; Fujimoto, S.; Cui, Y.; Sato, K.; Sano, R.; Yamaoka, S.; Kohchi, T.; Berger, F.; Nakajima, K. Deep Evolutionary Origin of Gamete-Directed Zygote Activation by KNOX/ BELL Transcription Factors in Green Plants. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lin, H.; Joo, S.; Goodenough, U. Early Sexual Origins of Homeoprotein Heterodimerization and Evolution of the Plant KNOX/BELL Family. Cell 2008, 133, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, C.J.; Coriey, S.B.; Moylan, E.C.; Alexander, D.L.; Scotland, R.W.; Langdale, J.A. Independent Recruitment of a Conserved Developmental Mechanism during Leaf Evolution. Nature 2005, 434, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, J.; Tanabe, Y.; Soma, S.; Ito, M. Class 1 KNOX Gene Expression Supports the Selaginella Rhizophore Concept. Journal of Plant Biology 2010, 53, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Buylla, E.R.; Liljegren, S.J.; Pelaz, S.; Gold, S.E.; Burgeff, C.; Ditta, G.S.; Vergara-Silva, F.; Yanofsky, M.F. MADS-Box Gene Evolution beyond Flowers: Expression in Pollen, Endosperm, Guard Cells, Roots and Trichomes. The Plant Journal 2000, 24, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschel, K.; Kofuji, R.; Hasebe, M.; Saedler, H.; Münster, T.; Theißen, G. Two Ancient Classes of MIKC-Type MADS-Box Genes Are Present in the Moss Physcomitrella Patens. Mol Biol Evol 2002, 19, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, Y.; Hasebe, M.; Sekimoto, H.; Nishiyama, T.; Kitani, M.; Henschel, K.; Mü nster, T.; nter Theissen, G.; Nozaki, H.; Ito, M. Characterization of MADS-Box Genes in Charophycean Green Algae and Its Implication for the Evolution of MADS-Box Genes; 2005.

- Singer, S.D.; Krogan, N.T.; Ashton, N.W. Clues about the Ancestral Roles of Plant MADS-Box Genes from a Functional Analysis of Moss Homologues. Plant Cell Rep 2007, 26, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimizu, S.; Kofuji, R.; Sasaki-Sekimoto, Y.; Kikkawa, M.; Shimojima, M.; Ohta, H.; Shigenobu, S.; Kabeya, Y.; Hiwatashi, Y.; Tamada, Y.; et al. Physcomitrella MADS-Box Genes Regulate Water Supply and Sperm Movement for Fertilization. Nature Plants 2018, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, G.; Nayar, S. A Survey of MIKC Type MADS-Box Genes in Non-Seed Plants: Algae, Bryophytes, Lycophytes and Ferns. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 342764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Theißen, G. The Major Clades of MADS-Box Genes and Their Role in the Development and Evolution of Flowering Plants. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2003, 29, 464–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, S.; Shchennikova, A.V.; Franken, J.; Immink, R.G.H.; Angenent, G.C. Control of Floral Meristem Determinacy in Petunia by MADS-Box Transcription Factors. Plant Physiol 2006, 140, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobell, O.; Faigl, W.; Saedler, H.; Münster, T. MIKC* MADS-Box Proteins: Conserved Regulators of the Gametophytic Generation of Land Plants. Mol Biol Evol 2010, 27, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, B.A.; Smalls, T.L.; Zumajo-Cardona, C. All Type II Classic MADS-Box Genes in the Lycophyte Selaginella Moellendorffii Are Broadly yet Discretely Expressed in Vegetative and Reproductive Tissues. Evol Dev 2021, 23, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechmann, J.L.; Meyerowitz, E.M. The AP2/EREBP Family of Plant Transcription Factors. Biol Chem 1998, 379, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutterson, N.; Reuber, T.L. Regulation of Disease Resistance Pathways by AP2/ERF Transcription Factors. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2004, 7, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, R.; Xu, D.; Bi, H.; Xia, Z.; Peng, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the AP2 Transcription Factor Gene Family in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 486684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Soltis, P.S.; Wall, K.; Soltis, D.E. Phylogeny and Domain Evolution in the APETALA2-like Gene Family. Mol Biol Evol 2006, 23, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumajo-Cardona, C.; Vasco, A.; Ambrose, B.A. The Evolution of the KANADI Gene Family and Leaf Development in Lycophytes and Ferns. Plants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipp-álvarez, M.; Cruz-Ramírez, A. A Phylogenetic Study of the ANT Family Points to a PreANT Gene as the Ancestor of Basal and EuANT Transcription Factors in Land Plants. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutterson, N.; Reuber, T.L. Regulation of Disease Resistance Pathways by AP2/ERF Transcription Factors. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2004, 7, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, L.T.; Pandzic, D.; Youngstrom, C.E.; Wallace, S.; Irish, E.E.; Szövényi, P.; Cheng, C.L. A Fern AINTEGUMENTA Gene Mirrors BABY BOOM in Promoting Apogamy in Ceratopteris Richardii. The Plant Journal 2017, 90, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizek, B.A.; Bantle, A.T.; Heflin, J.M.; Han, H.; Freese, N.H.; Loraine, A.E. AINTEGUMENTA and AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6 Directly Regulate Floral Homeotic, Growth, and Vascular Development Genes in Young Arabidopsis Flowers. J Exp Bot 2021, 72, 5478–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, S.; Wang, Y.; Ward, J.M.; Dudek, S.M. Optimized Method for Robust Transcriptome Profiling of Minute Tissues Using Laser Capture Microdissection and Low-Input RNA-Seq. Front Mol Neurosci 2017, 10, 272672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakszewska, A.; Tel, J.; Chokkalingam, V.; Huck, W.T.S. One Drop at a Time: Toward Droplet Microfluidics as a Versatile Tool for Single-Cell Analysis. NPG Asia Materials 2014, 6, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialdone, A.; Natarajan, K.N.; Saraiva, L.R.; Proserpio, V.; Teichmann, S.A.; Stegle, O.; Marioni, J.C.; Buettner, F. Computational Assignment of Cell-Cycle Stage from Single-Cell Transcriptome Data. Methods 2015, 85, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendall, S.C.; Davis, K.L.; Amir, E.A.D.; Tadmor, M.D.; Simonds, E.F.; Chen, T.J.; Shenfeld, D.K.; Nolan, G.P.; Pe’Er, D. Single-Cell Trajectory Detection Uncovers Progression and Regulatory Coordination in Human B Cell Development. Cell 2014, 157, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.W. A Single-Cell Analysis of the Arabidopsis Vegetative Shoot Apex. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 1056–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterlee, J.W.; Strable, J.; Scanlon, M.J. Plant Stem-Cell Organization and Differentiation at Single-Cell Resolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ru, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Nakazono, M.; Shabala, S.; Smith, S.M.; Yu, M. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Pea Shoot Development and Cell-Type-Specific Responses to Boron Deficiency. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Du, Q.; Xu, M.; Du, F.; Jiao, Y. Single-Nucleus RNA-Seq Resolves Spatiotemporal Developmental Trajectories in the Tomato Shoot Apex. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, D.; Triozzi, P.M.; Pereira, W.J.; Schmidt, H.W.; Balmant, K.M.; Knaack, S.A.; Redondo-López, A.; Roy, S.; Dervinis, C.; Kirst, M. Single-Nuclei Transcriptome Analysis of the Shoot Apex Vascular System Differentiation in Populus. Development (Cambridge) 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommert, P.; Lunde, C.; Nardmann, J.; Vollbrecht, E.; Running, M.; Jackson, D.; Hake, S.; Werr, W. Thick Tassel Dwarf1 Encodes a Putative Maize Ortholog of the Arabidopsis CLAVATA1 Leucine-Rich Repeat Receptor-like Kinase. Development 2005, 132, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, F.; Jackson, D. All Together Now, a Magical Mystery Tour of the Maize Shoot Meristem. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2018, 45, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somssich, M.; Je, B.I.; Simon, R.; Jackson, D. CLAVATA-WUSCHEL Signaling in the Shoot Meristem. Development 2016, 143, 3238–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardmann, J.; Werr, W. The Invention of WUS-like Stem Cell-Promoting Functions in Plants Predates Leptosporangiate Ferns. Plant Mol Biol 2012, 78, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureyns, R.; Joossens, J.; Herwegh, D.; Pevernagie, J.; Pavie, B.; Demuynck, K.; Debray, K.; Coussens, G.; Pauwels, L.; van Hautegem, T.; et al. An in Situ Sequencing Approach Maps PLASTOCHRON1 at the Boundary between Indeterminate and Determinate Cells. Plant Physiol 2022, 188, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhl, P.L.; Salmén, F.; Vickovic, S.; Lundmark, A.; Navarro, J.F.; Magnusson, J.; Giacomello, S.; Asp, M.; Westholm, J.O.; Huss, M.; et al. Visualization and Analysis of Gene Expression in Tissue Sections by Spatial Transcriptomics. Science (1979) 2016, 353, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomello, S.; Lundeberg, J. Preparation of Plant Tissue to Enable Spatial Transcriptomics Profiling Using Barcoded Microarrays. Nat Protoc 2018, 13, 2425–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomello, S.; Salmén, F.; Terebieniec, B.K.; Vickovic, S.; Navarro, J.F.; Alexeyenko, A.; Reimegård, J.; McKee, L.S.; Mannapperuma, C.; Bulone, V.; et al. Spatially Resolved Transcriptome Profiling in Model Plant Species. Nat Plants 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, V.; Natarajan, K.N.; Ly, L.H.; Miragaia, R.J.; Labalette, C.; Macaulay, I.C.; Cvejic, A.; Teichmann, S.A. Power Analysis of Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing Experiments. Nature Methods 2017, 14, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).