Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparing the microporous β-TCP ceramics

2.2. Characterization of the microporous β-TCP ceramics

2.3. Preparation and Characterization of the ADA-gelatin hydrogels

2.3.1. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC)

2.3.2. Rheology

2.4. Loading the microporous β-TCP ceramics

2.5. Release experiments

2.6. Determination of the release kinetics of daptomycin and BMP-2

2.6.1. HPLC

2.6.2. ELISA

2.7. Biocompatibility

2.8. Anti-microbial activity

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

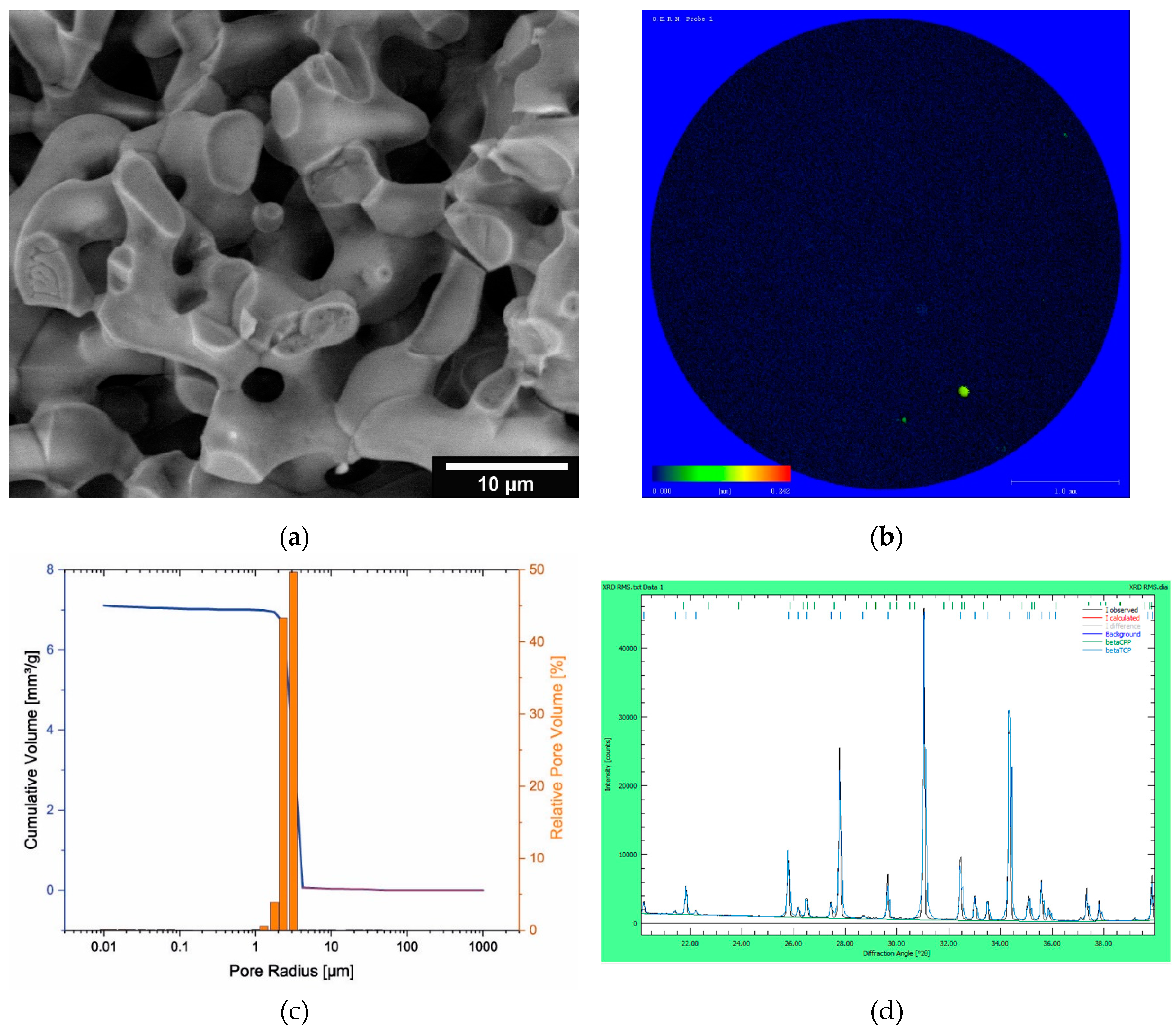

3.1. Characterization of the microporous β-TCP

3.2. Characterization of the ADA-gelatin gel

3.3. Release kinetics of dual release of daptomycin and BMP-2

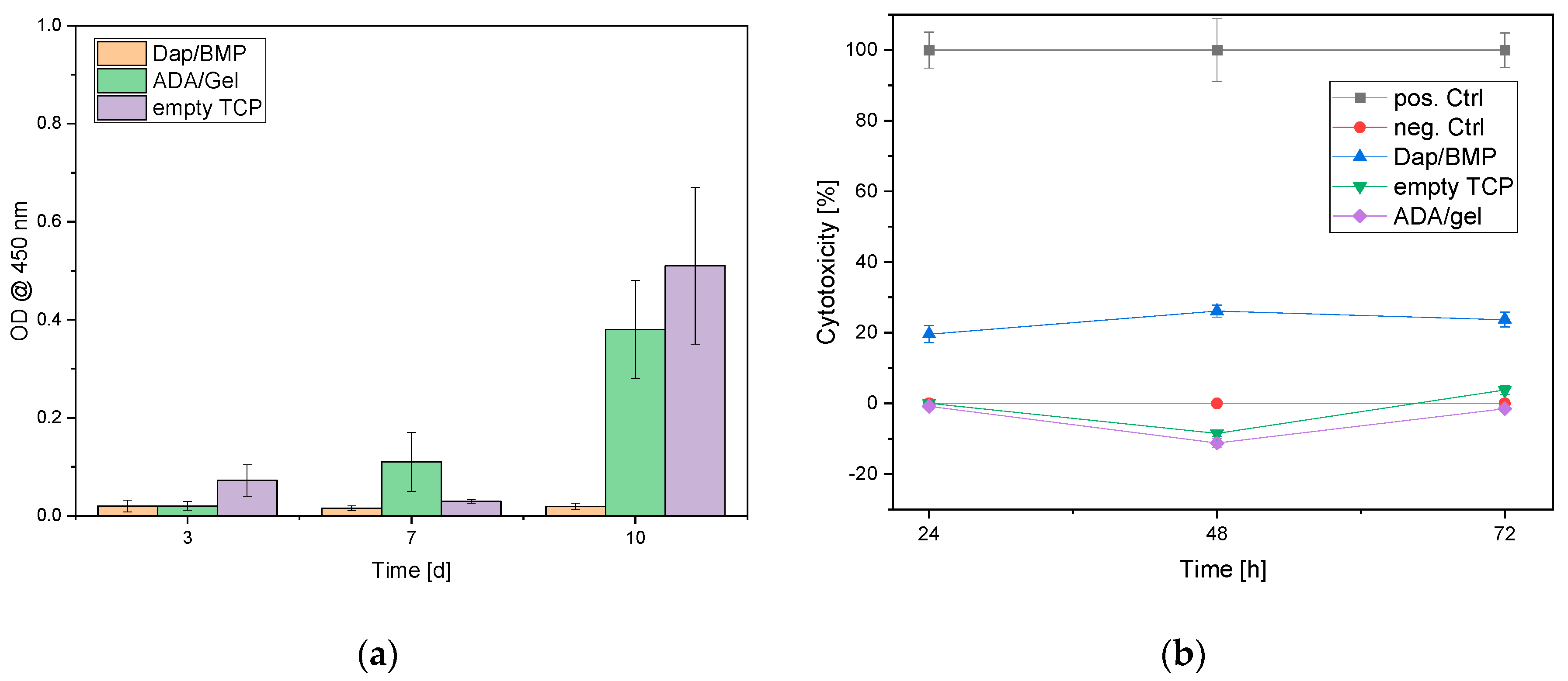

3.4. Biocompatibility

3.5. Antimicrobial activity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, Y.J.; Sadigh, S.; Mankad, K.; Kapse, N.; Rajeswaran, G.J.Q.I.i.M.; Surgery. The imaging of osteomyelitis. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 2016, 6, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, T.C.; Gomes, M.S.; Gomes, A.C. The crossroads between infection and bone loss. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, W. Clinical presentation and treatment of orthopaedic implant-associated infection. Journal of Internal Medicine 2014, 276, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, J.; Pulling, T.J. Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 84, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Sia, I.G.; Berbari, E.F. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Osteomyelitis. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology 2006, 20, 1065–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, B.H.; Berg, R.A.; Daley, J.A.; Fritz, J.; Bhave, A.; Mont, M.A. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet 2016, 387, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, D.P.; Waldvogel, F.A. Osteomyelitis. Lancet 2004, 364, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, S.K. Osteomyelitis. Infectious disease clinics of North America 2017, 31, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraimow, H.S. Systemic antimicrobial therapy in osteomyelitis. Seminars in Plastic Surgery 2009, 23, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, J.S.; Meehan, J.P.; Di Cesare, P.E.; Jamali, A.A. Local antibiotic therapy in osteomyelitis. Semin Plast Surg 2009, 23, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaha, J.D.; Calhoun, J.H.; Nelson, C.L.; Henry, S.L.; Seligson, D.; Esterhai, J.L.J.; Heppenstall, R.B.; Mader, J.; Evans, R.P.; Wilkins, J.; et al. Comparison of the clinical efficacy and tolerance of gentamicin pmma beads on surgical wire versus combined and systemic therapy for osteomyelitis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 1993, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Peña, E.; Frutos, G.; Frutos, P.; Barrales-Rienda, J.M. Gentamicin sulphate release from a modified commercial acrylic surgical radiopaque bone cement. I. Influence of the gentamicin concentration on the release process mechanism. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2002, 50, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar Giri, T.; Thakur, D.; Alexander, A.; Ajazuddin; Badwaik, H.; Krishna Tripathi, D. Alginate based hydrogel as a potential biopolymeric carrier for drug delivery and cell delivery systems: Present status and applications. Curr. Drug Del. 2012, 9, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidenstuecker, M.; Kissling, S.; Ruehe, J.; Suedkamp, N.; Mayr, H.; Bernstein, A. Novel method for loading microporous ceramics bone grafts by using a directional flow. J Funct Biomater 2015, 6, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, S.; Seidenstuecker, M.; Pilz, I.H.; Suedkamp, N.P.; Mayr, H.O.; Bernstein, A. Sustained release of rhbmp-2 from microporous tricalciumphosphate using hydrogels as a carrier. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidenstuecker, M.; Ruehe, J.; Suedkamp, N.P.; Serr, A.; Wittmer, A.; Bohner, M.; Bernstein, A.; Mayr, H.O. Composite material consisting of microporous β-tcp ceramic and alginate for delayed release of antibiotics. Acta Biomater. 2017, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrade, S.; Ritschl, L.; Süss, R.; Schilling, P.; Seidenstuecker, M. Gelatin nanoparticles for targeted dual drug release out of alginate-di-aldehyde-gelatin gels. Gels 2022, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidenstuecker, M.; Schmeichel, T.; Ritschl, L.; Vinke, J.; Schilling, P.; Schmal, H.; Bernstein, A. Mechanical properties of the composite material consisting of β-tcp and alginate-di-aldehyde-gelatin hydrogel and its degradation behavior. Materials 2021, 14, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Jayakrishnan, A.; Kumar, S.S.P.; Nandkumar, A.M. Anti-bacterial properties of an in situ forming hydrogel based on oxidized alginate and gelatin loaded with gentamycin. Trends Biomater Artificial Organs 2012, 26, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, H.O.; Klehm, J.; Schwan, S.; Hube, R.; Sudkamp, N.P.; Niemeyer, P.; Salzmann, G.; von Eisenhardt-Rothe, R.; Heilmann, A.; Bohner, M. , et al. Microporous calcium phosphate ceramics as tissue engineering scaffolds for the repair of osteochondral defects: Biomechanical results. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 4845–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschl, L.; Schilling, P.; Wittmer, A.; Bohner, M.; Bernstein, A.; Schmal, H.; Seidenstuecker, M. Composite material consisting of microporous beta-tcp ceramic and alginate-dialdehyde-gelatin for controlled dual release of clindamycin and bone morphogenetic protein 2. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2023, 34, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUCAST. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of mics and zone diameters. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing - EUCAST: Växjö, 2023. V: The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing - EUCAST, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diederen, B.M.; van Duijn, I.; Willemse, P.; Kluytmans, J.A. In vitro activity of daptomycin against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, including heterogeneously glycopeptide-resistant strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 3189–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehling, T.; Schilling, P.; Bernstein, A.; Mayr, H.O.; Serr, A.; Wittmer, A.; Bohner, M.; Seidenstuecker, M. A human bone infection organ model for biomaterial research. Acta Biomater. 2022, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, B.; Rompf, J.; Silva, R.; Lang, N.; Detsch, R.; Kaschta, J.; Fabry, B.; Boccaccini, A.R. Alginate-based hydrogels with improved adhesive properties for cell encapsulation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2015, 78, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, B.; Papageorgiou, D.G.; Silva, R.; Zehnder, T.; Gul-E-Noor, F.; Bertmer, M.; Kaschta, J.; Chrissafis, K.; Detsch, R.; Boccaccini, A.R. Fabrication of alginate-gelatin crosslinked hydrogel microcapsules and evaluation of the microstructure and physico-chemical properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2014, 2, 1470–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenburg, J.; Vinke, J.; Riedel, B.; Zankovic, S.; Schmal, H.; Seidenstuecker, M. Alternative geometries for 3d bioprinting of calcium phosphate cement as bone substitute. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Mn [kDa] | Mw [kDa] | Mz [kDa] | PDI (= Mw/Mn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate before plasma sterilization | 198 | 729 | 1440 | 3.68 |

| Alginate after plasma sterilization | 201 | 767 | 1530 | 3.81 |

| ADA unsterile | 52.4 | 316 | 1280 | 6.03 |

| ADA out of plasma-sterile alginate | 55.3 | 298 | 1160 | 5.38 |

| ADA out of unsterile alginate, plasma sterilized after manufacturing | 6.91 | 17.8 | 39.8 | 2.57 |

| ADA out of plasma-sterile alginate and plasma sterilized again after manufacturing | 13.1 | 41 | 116 | 3.13 |

| Gelatin before plasma sterilization | 16.3 | 114 | 254 | 6.99 |

| Gelatine after plasma sterilization | 15.9 | 105 | 231 | 6.61 |

| Release period [d] | Daptomycin-Release [µg/ml] | BMP-2 Release [ng/ml] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1026.05 ± 84.28 | 59.80 ± 90.0 |

| 2 | 318.01 ± 34.85 | 101.86 ± 92.04 |

| 3 | 72.43 ± 48.64 | 669.00 ± 148.40 |

| 6 | 8.62 ± 2.65 | 208.96 ± 43.20 |

| 9 | 2.76 ± 0.18 | 71.54 ± 47.63 |

| 14 | 1.45 ± 1.30 | 148.31 ± 100.86 |

| 21 | 0.37 ± 0.98 | 1.75 ± 6.14 |

| 28 | 0.18 ± 0.67 | 2.63 ± 9.15 |

| Recovery [%]: | 105.13 ± 9.14 | 0.72 ± 0.16 |

| Sample | Relative cell count [%] | ||

| Alive | Intermediate | Dead | |

| Day3 | |||

| Dap/BMP-2 | 74.85 ± 48.16 | 5.56 ± 2.82 | 19.59 ± 9.08 |

| Control (empty ceramics) | 95.93 ± 14.21 | 0 ± 0 | 4.07 ± 1.20 |

| Control 2 (ADA/Gel no drugs) | 96.48 ± 31,22 | 0 ± 0 | 3.52 ± 1.93 |

| Day 7 | |||

| Dap/BMP-2 | 65.83 ± 27.14 | 0 ± 0 | 34.17 ± 23.41 |

| Control (empty ceramics) | 93.53 ± 11.33 | 0 ± 0 | 6.47 ± 1.48 |

| Control 2 (ADA/Gel no drugs) | 82.95 ± 31.48 | 0 ± 0 | 17.05 ± 4.80 |

| Day 10 | |||

| Dap/BMP-2 | 77.41 ± 63.13 | 0 ± 0 | 22.59 ± 22.97 |

| Control (empty ceramics) | 89.07 ± 53.61 | 0 ± 0 | 10.93 ± 3.84 |

| Control 2 (ADA/Gel no drugs) | 82.79 ± 27.79 | 0 ± 0 | 17.21 ± 10.67 |

| Sample | Dilution levels of the original concentration [mg/l] | ||||||||||||

| 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| Control | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | 0.5 |

| 1291 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D1P1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | 0.5 |

| 308 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D2P1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | 0.5 |

| 110.5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| DT3P1 | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | 1 |

| 18.59 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D6P1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | 0.5 |

| - | 0.95 | 0.475 | 0.238 | 0.119 | 0.059 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.004 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D9P1 | / | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | 0.475 |

| - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D14P1 | / | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | > 0 |

| - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D21P1 | / | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | > 0 |

| - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | GC | EW | MIC | |

| D28P1 | / | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | > 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).