1. Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a three-dimensional spine deformity. It is the most common type of scoliosis during rapid growth [

1]. The etiopathogenesis of AIS is still unknown, but it is considered a multi-etiologic situation [

2]. Studies on neurological etiological mechanisms among these multiple etiologies have compared patients with AIS with healthy controls or patients with progressive curvature and patients with scoliosis without progressive curvature type [

2,

3,

4]. These studies generally include electroencephalography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Asymmetries in various brain structures, brain volume differences, changes in anatomical structures and neurological anomalies have been determined. Musculoskeletal, postural, and sensory-motor asymmetries may accompany neurological asymmetries in AIS [5, 6].

In patients with AIS, cortical enlargement has been observed mainly in motor and vestibular areas, and the cortex in the right hemisphere appears thinner than in the left hemisphere [

5]. Domenech et al. stated normal cortico-cortical inhibition in coordination with transcranial magnetic stimulation on the concave side, whereas a significant decrease was observed on the concave side [

7]. Liu et al. found volumetric changes in 22 brain sections using magnetic resonance [

8]. Joly et al. reported that they encountered a right thoracic and right thoracic-left lumbar curvature pattern with a corpus callosum located at a lower level [

9]. Observing increased blood oxygenation levels due to motor activity in contra-lateral complementary motor regions in AIS supports interhemispheric asymmetry [

10]. Robb et al. reported that patients with AIS showed a difference in brain responsiveness, showing similar electroencephalography (EEG) results to the control group [

11]. At the same time, pathological abnormality in subcortical structures may be present due to increased low-frequency brain activity and proximal activity in patients with AIS [12, 13]. Pathological EEG results were found in the contralateral hemisphere in AIS patients with lumbar curvature, the ipsilateral hemisphere in patients with thoracolumbar curvature, and the bilateral hemisphere in patients with thoracic curvature [

13]. Pinchuk et al. reported increased bioelectrical activity in the left hemisphere, especially in the left thalamus [

14]. Cristancho et al. reported in systematic review that in the neurological response to idiopathic scoliosis, sensory-cortical integration of interactions may cause progression of the deformity by allowing modifications at the postural level to provide an initial compensation in the sagittal region [

15]. In an another systematic review of vestibular morphological asymmetries, Cortés-Pérez et al. pointed out that it is difficult to determine which factor is the cause and which is the result [

16]. Since the etiopathogenesis of AIS is limited, the inability to explain the cause-effect relationship may indirectly affect the effectiveness of treatment approaches.

In addition to these neuroimaging techniques, perceptional and cognitive asymmetries at the cortical level are narrowly assessed by the Dichotic Listening Paradigm (DLP). In DLP, first applied by Kimura, one of the two separate audio stimuli is presented synchronously in each ear. Sounds heard in the right ear go directly to the contralateral auditory cortex, while sounds heard in the left ear go to the contralateral auditory cortex and are indirectly transmitted to the ipsilateral auditory cortex [

17,

18,

19].

Goldberg et al., evaluating asymmetry with DLP without attention to any ear, stated that right ear advantage was higher in AIS than healthy controls [

20]. AIS with progressive scoliosis had lower left hemisphere dominance than with non-progressive scoliosis, according to Enslein and Chan [

21]. In these two studies, DLP was performed in the none-forced (NF) condition, while Akçay et al. examined auditory lateralization in the forced-right (FR) and forced-left (FL) [

22]. In FR, the typical response pattern follows a contralateral brain tract synergistically. The FL condition is more demanding and uses more expressive cognitive strategies [23, 24]. Therefore, shifting attention to one ear involves different cognitive processes and provides information about corpus callosum function and hemispheric integration [

25]. Akçay et al. demonstrated that in FL condition patients with AIS could not direct their attention to the left side and asymmetry did not differentiate according to the curvature type [

22]. In all of the studies in which AIS patients were evaluated with DLP, asymmetries in the auditory system were reported [

20,

21,

22].

Conservative approaches in AIS include exercise and brace treatment. High-level evidence [26, 27] shows that Schroth and Schroth Best Practice (SBP) exercises and Cheneau brace treatment effectively improve quality of life and reduce Cobb angle [

28,

29,

30]. Although patients with AIS have asymmetry cortical levels, there is no research on how conservative treatments affect cerebellar functional organization.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of conservative treatments on perceptual and cognitive asymmetry in the auditory system of AIS patients with thoracic major curve.

2. Materials and Methods

Study was designed as a case-control study. Individuals diagnosed with AIS who were referred to our department between January and July 2023 were included as the intervention group, and healthy participants were included as the control group. Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Committee of Bandırma Onyedi Eylül University (Number: 19.12.2022-261, Date: 19.12.2022). The participants and one of their parents signed the informed consent forms.

The inclusion criteria for the intervention group were to have been diagnosed with AIS, to be between 10-16 years of age, to have a Cobb angle between 20° and 50° and a Risser's sign between 0-3, to have right thoracic scoliosis, right-handed, no previous treatment that may affect scoliosis, and to have no chronic disease requiring the use of medication; for the control group, participants aged 10-16 years were included. In both groups, previous spinal operation, hearing loss, presence of other muscular, neurological and rheumatic diseases were excluded.

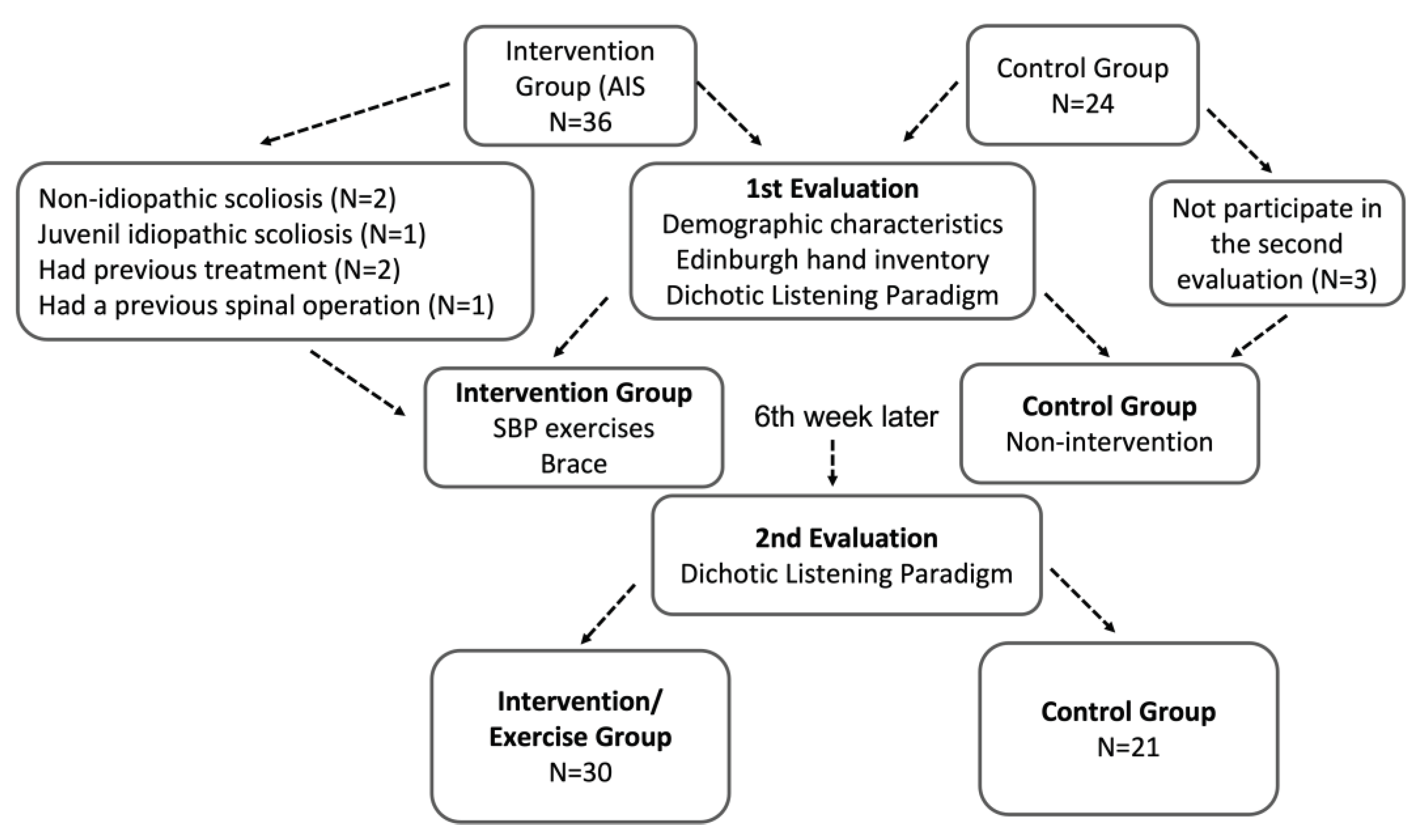

The study included 30 AIS patients and 21 healthy subjects, and the flow diagram of the study is given in

Figure 1.

2.1. Assessments:

The degree of curvature in the coronal plane was evaluated according to the

Cobb method. The Cobb, considered the gold standard, is the angle between the intersection of perpendiculars descending from the top of the curve along the upper endplate of the uppermost oblique vertebra and the intersection of lines drawn under the lower endplate of the lowermost oblique vertebra [

31]. In this study, the Cobb angle was determined by measuring it on the X-ray, which was routinely requested by the physician, and no extra x-ray was requested after the end of the 6

th week of treatment, except for the routinely requested X-ray.

Risser sign was evaluated as closure of the growth plates of the iliac crest on X-ray. The epiphyseal plate starts at the lateral edge of the spina illicia anterior superior, progresses medially, and is completed at the spina illicia posterior superior. The degree of completion is expressed as a percentage: Grade 1≤ 25%, Grade 2 26-50%, Grade 3 51-75%, and Grade 4 75-100%. When the epiphysis merges with the ilium, it is defined as Grade 5 [

32].

The topographic classification was widely used for classifying curvature patterns in AIS for conservative treatment according to 2016 SOSORT guideline. The topographic classification is based on the spinal segment where the curve's apex is located and is classified as cervical, cervicothoracic, thoracic, lumbar and lumbosacral. [

33]. This study included individuals with a thoracic curvature pattern in which the curve's apex was between thoracic vertebrae 1 and 12. Although Akçay et al. reported that perceptional asymmetry might not depend on the type of curvature [

22], only patients with AIS with right thoracic major curve patterns were included in this study to make the group more homogeneous.

The Edinburgh hand preference questionnaire was used to determine participants' hand dominance. The preferred hand was questioned in writing, drawing, throwing objects, using scissors, brushing teeth, using a knife, using a spoon, using a broom, lighting matches and opening boxes [

34].

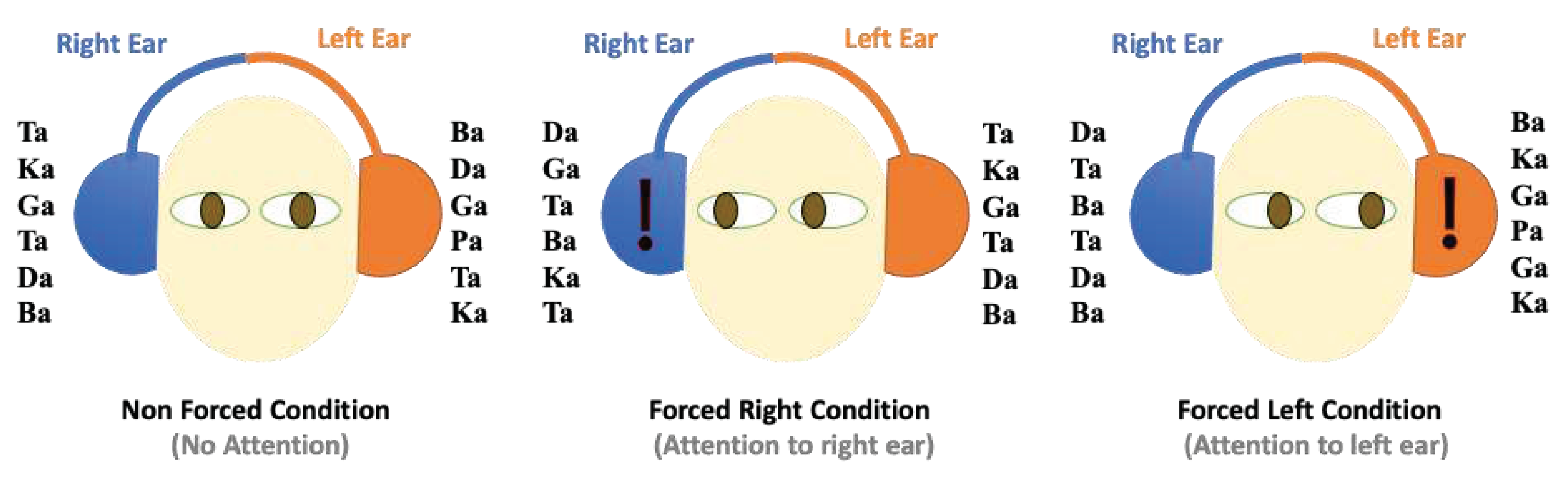

The Dichotic Listening Paradigm is a method that provides behavioral information to determine auditory system asymmetry and is reliable for use with adolescents [

35]. The DLP was implemented in both groups at baseline and the end of week 6 in a seated position with eyes open in a quiet room. In this paradigm, syllable of ba, da, ga, pa, ta, and ka were utilized, which were standardized by Dokuz Eylül University Music Sciences Voice Studio for Turkish society [

36].

Thirty heteronyms and six homogeneous combinations were used, and stimuli were applied randomly in the 3-6 s band. Using Sony CDR50 headphones, 36 pairs of binary syllables were obtained. The duration of session was 7.5 min, approximately 25-30 min. There were three different conditions in the standard DL paradigm. In the NF condition, participants were requested to declare their best hearing. In the FR, participants listened with their right ear; they listened with their left ear in the FL condition (

Figure 2).

Calculating the proportion of correct responses in the right to correct answers in the left was used to measure right-left asymmetry. The resulting score was understood as an increase in asymmetry as it moved away from 1 (or a decrease in asymmetry as it approached 1).

The IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for Windows version 20.0 was used to analyze the study's data. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values, were analyzed for demographics, including age, height, weight, BMI, and Cobb angle values.

To ascertain whether the data had a normal distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was applied.

As a result, a parametric independent samples t-test was used to compare group differences for baseline values.

By using differences were analyzed between groups at baseline and 6th week.

Intra-group comparisons at baseline and 6th week were analyzed with Paired Sample T-tests.

Inter-group comparisons were performed with Independent Samples T-test

The threshold for p-significance was set at less than 0.05 in each statistical analysis.

2.2. Intervention:

The intervention group used braces and engaged in Schroth Best Practice exercises under the guidance of the same physiotherapist.

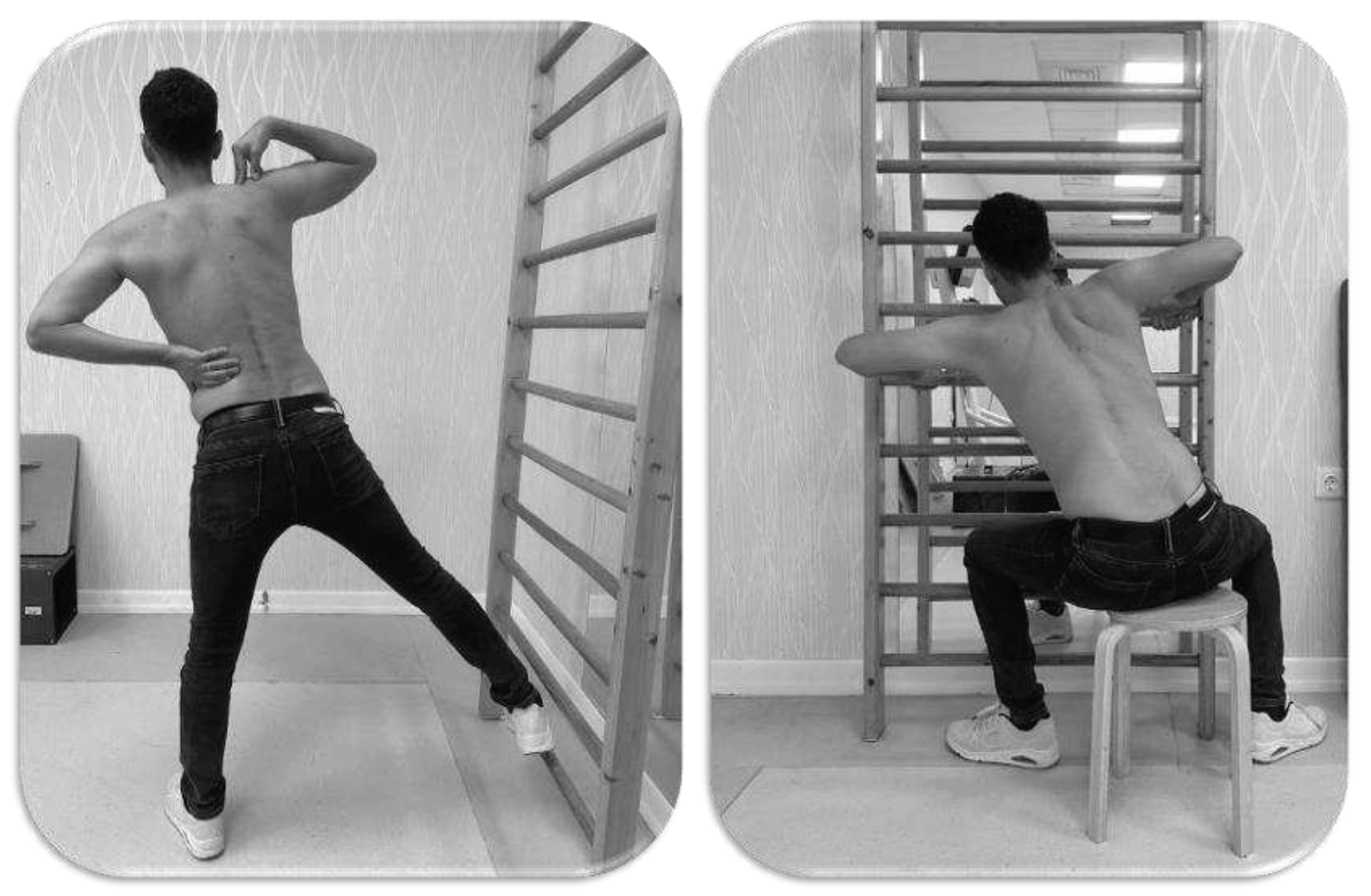

The

Schroth Best Practice exercise is the most recent iteration of the Schroth method, which was developed by Dr. Weiss, in light of current scientific knowledge. Dr. Weiss modified the original technique to make the exercise patterns applicable to smaller curves and added sagittal plane corrections, activities of daily living, and bracing to create a comprehensive treatment plan. The Schroth Best Practice consists of seven modules, including the physio-logic® program for correction of the sagittal profile, training in activities of daily living, the "3D-made easy" program, the new "Power Schroth" program, gait rehabilitation and neuromobilisation. Physiologic exercises to correct the sagittal plane are essential to the program. Daily living activities training aims to internalize the corrective posture by using it daily. In Power Schroth exercise, active corrections are made after teaching the starting position, followed by rotational breathing technique and stabilization (

Figure 3). Gait rehabilitation was made specific to the curve pattern, and its maintenance in daily life was required [

37]. All modules of the SBP program were implemented for the participants. There were 18 sessions, each lasting 90 minutes, for the exercise training.

Specially designed rigid, asymmetric Cheneau braces were used in accordance with the curvature characteristics of each AIS patient. The brace treatment protocol consisted of wearing the brace for 23 hours daily and removing it for 1 hour for personal care. The duration of brace wearing was checked by asking patients and families.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the distribution the of the demographic traits among the groups. Age, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) did not differ (p> 0.05) (

Table 1). There were 24 girls and 6 boys in the AIS patients and 16 girls and 5 boys in the control. In addition, the mean Cobb angles of the patients with AIS at the time of presentation to the department were 34.00° ± 5.44°. After completing 6 weeks of exercise therapy, the mean Cobb angles on routine X-rays were 28.93° ± 9.50°. A decrease in Cobb angle was detected after Schroth Best Practice exercises (p:0.000).

Intra-group comparisons at baseline and 6th week showed no significant differences in any DLP results in the control (p>0,05). In contrast, in the AIS group, there was a significant statistical increase only left ear responses in the FL condition (p<0,05) (

Table 2).

Inter-group DLP results at baseline, only left ear responses were significantly lower in the AIS group for all DLP conditions (p<0.05). The 6th week results were similar in all conditions (p>0.05). The ratio of right and left responses was statistically significantly higher in the AIS at baseline only in the NF condition (p<0.01), but this significant difference was not observed in the 6th-week results (p>0.05).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of SBP exercises and brace treatment on cognitive asymmetry in AIS patients. Results of this study demonstrated that 18 sessions of SBP exercises and brace treatment might improve the perception of left ear stimuli in AIS patients. Furthermore, it was concluded that while left ear responses were less than healthy individuals in all DLP conditions before the treatment, they were similar to the responses of healthy individuals after the treatment.

The framework of the DLP is perceptual and cognitive lateralization in the auditory system, where each hemisphere of the brain competes at particular cognitive tasks. When stimuli are presented to both ears, participants in the NF condition report more information coming from the right, demonstrating left hemisphere dominance for processing. In the FR condition, right ear advantage increased as a result of attention to the right ear, which followed a bottom-up bias towards the right ear stimulus. A bottom-up asymmetry in language processing is observed in the FR when attention to the left ear synergistically follows the brain's contralateral pathway. As a result, every situation involves a unique set of cognitive processes [23, 24]. Despite the insufficiency of studies on auditory asymmetry assessed using DLP in AIS patients, all of the available studies' findings supported the existence of asymmetry [

20,

21,

22]. Enslein & Chan stated that progressive AIS patients had worse left hemisphere superiority, and Goldberg et al. stated that auditory asymmetry in AIS patients was caused by the presence of more right ear advantage [20, 21]. In these studies, only the NF condition was examined. In contrast to these studies, our study found that the number of right ear was comparable to that of the control subjects, while the number of left ear was lower. On the other hand, Akçay et al. declared that there was an asymmetry between AIS patients and healthy controls, particularly in the NF and FL conditions, and that this was managed to bring on by the lower left ear score. Even though the left ear in this study was smaller than the control group in all conditions, the asymmetry value was only found to be statistically significant in the NF condition. Despite the fact that Akçay et al. [

22] assumed that this asymmetry was unaffected by the type of curvature, the current study only included AIS patients with major thoracic curvature. Future research may be required to look into how different types of curvature affect auditory perceptual and cognitive asymmetry.

The preference for the right ear in humans in general is explained by various theories. Kimura's theory is that neural connections from the cochlea to the cortex are associated with right ear preference. Kimura argues that right ear input can easily reach the left hemisphere, which specializes in language. In contrast, left ear input is suppressed in the brainstem. After getting the right hemisphere, left ear input is weakened while being transported to the left hemisphere via the corpus callosum. Therefore, right ear preference is higher [

38]. Westerhausen stated that right ear preference is due to the functional integration of the corpus callosum as a structural and behavioral model [

39]. Morphologic corpus callosum anomalies, responsible for interhemispheric communication, have also been reported in patients with AIS [9, 40, 41]. In the present study, the standard deviation values of individuals with AIS DLP results were higher. The fact that the DLP responses of patients with AIS were more variable may be a remarkable situation, although it does not have statistical significance. This may be due to asymmetries in the brain structures of patients with AIS or morphologic changes in the corpus callosum, which plays an important role in right ear preference.

Evidence-based conservative treatment of scoliosis, including Schroth exercises and brace treatment, has been shown to improve the quality of life, vertebral rotation degree, Cobb angle, pain, body image, and vital capacity, and reduce the prevalence of surgery in AIS patients [26, 27, 42–45]. In this study, improvement in Cobb angle was achieved with SBP exercises and brace treatment, similar to the literature [

26]. However, no previous study examined the changes of SBP exercises and brace treatment on perceptual and cognitive asymmetry in the auditory system. Although there was an increase in left ear in all conditions after conservative treatment, a significant increase was observed only in the FL in the present study. However, it is noteworthy that while the number of left ear was lower in AIS compared to the control group in all conditions before the intervention, this phenomenon disappeared and was similar to the healthy controls after the intervention. The increase in left ear due to the treatment and its similarity to that of healthy controls might indicate a potential relationship between scoliosis and altered auditory processing, which may be related to neuroplastic changes in the brain. Scoliosis-related changes in spinal and postural control could lead to adaptations in sensory and motor networks that affect auditory perception. In addition, the observed differences may be due to disrupted connectivity between brain regions involved in motor control and auditory processing.

In a study by Hughdal et al. 15000 healthy subjects aged 5-89 years were assessed, and the authors reported that right ear increased significantly in the FR; in contrast, in the FL, right ear advantage decreased and generally shifted to left ear [

24]. This shift of attention was found to be greater in adults and less in children and adolescents. It has been concluded that the right ear advantage effect in DLP is subordinated to developmental effects, and attentional effects on laterality also develop with age [

46]. In current study, the participants of AIS and control group were at similar ages. Also conservative treatment results may alter auditory perception with the intervention since stimulus-focused laterality is dynamically altered by allocating attentional resources to the right or left side of the auditory field, as Hughdal et al. [

46]. However, studies with brain imaging methods are needed to determine where the perceptual and cognitive processes in the auditory system change with conservative treatment and where and in which plasticity may have occurred.

Although there are various limitations of the study, the main one is the limitedness of the study in which the results of the study can be discussed. The other is that the DLP data was taken only behaviorally. The combination of DLP and neuroimaging methods, such as electroencephalography, would have enabled us to reveal the source of the results of this study more clearly.

One of the study's strengths is that it only included patients with AIS and a curvature pattern of the right major thoracic scoliosis, thereby excluding any potential changes brought on by the curvature type. Reassessing the healthy control group after 6 weeks to take the learning effect into account is another strength of the present study.

Moreover, the literature focuses on the etiological factors of AIS and/or the curative orthopedic effects of conservative treatment on curvature. This study targeted to demonstrate the effects of the current conservative approach at the cortical level.

It is the first study to demonstrate that improving scoliosis - related deformity brought on by scoliosis may alter cortical asymmetry in perception and cognition.

Understanding the link between scoliosis and auditory processing may have important implications for conservative treatment approaches. If differences in auditory processing are consistently observed in individuals with scoliosis, rehabilitation strategies and interventions may be influenced. The investigation of the potential link between scoliosis and DLP in this study underlines the complexity of the condition and emphasizes the need for interdisciplinary approaches. As research in this area progresses, it is crucial to decipher the underlying mechanisms and clinical significance of auditory processing differences in individuals with scoliosis and improve understanding of cognitive function and spinal deformities.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that SBP exercises and brace treatment in AIS patients with thoracic major curvature may improve perceptual and cognitive asymmetry in the auditory system. The potential association between scoliosis and altered auditory processing can be attributed to neuroplastic changes in the brain. Scoliosis-related changes in the spine and postural control may affect auditory perception by causing adaptations in sensory and motor networks. Future studies are needed to examine the connectivity in brain regions related to motor control and auditory processing after conservative treatment with brain imaging systems. Thus, a new perspective can be brought to the conservative treatment strategies for AIS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A., G.İ; methodology, B.A., G.İ.; investigation, B.A., G.İ.; data curation, B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A., G.İ.; writing—review and editing, B.A., G.İ.; supervision, B.A., G.İ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no financial support granted for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Bandırma Onyedi Eylül University (19.12.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical devices.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to data collection is ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Murat Özgören, Prof. Dr. Adile Öniz and Assoc. Prof. Tuğba Kuru Çolak for providing support.

Conflicts of Interest

We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on me or on any organization with which we are associated.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheng, J. C.; Castelein, R. M.; Chu, W. C.; Danielsson, A. J.; Dobbs, M. B.; Grivas, T. B.; Gurnett, C. A.; Luk, K. D.; Moreau, A.; Newton, P. O.; Stokes, I. A.; Weinstein, S. L.; Burwell, R. G. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. J.; Yeung, H. Y.; Chu, W. C.; Tang, N. L.; Lee, K. M.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Top theories for the etiopathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of pediatric orthopedics 2011, 31(1 Suppl), 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.G; Edgar, M.; Margulies, J.Y.; Miller, N.H.; Raso, V.J.; Reinker, K.A.; et al. Etiology of idiopathic scoliosis: current trends in research. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000, 82, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provencher, M.; Wester, D.; Gillingham, B.; Gottshall, K.; Hoffer, M. (Eds.) Vestibular dysfunction in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Western Orthopaedic Association 67th Annual Meeting, San Antonio; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Shi, L.; Chu, W.C.; Burwell, R.G.; Cheng, J.C.; Ahuja, A.T. Abnormal cerebral cortical thinning pattern in adolescent girls with idiopathic scoliosis. Neuroimage 2012, 59, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlösser, T.P.; van der Heijden, G.J.; Versteeg, A.L.; Castelein, R.M. How ‘idiopathic’is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? A systematic review on associated abnormalities. PloS one 2014, 9, e97461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doménech, J.; Tormos, J.M.; Barrios, C.; Pascual-Leone, A. Motor cortical hyperexcitability in idiopathic scoliosis: could focal dystonia be a subclinical etiological factor? Eur Spine J 2010, 19, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chu, W.C.; Young, G.; Li, K.; Yeung, B.H.; Guo, L.; Man, G.C.; Lam, W.W.; Wong, S.T.; Cheng, J.C. MR analysis of regional brain volume in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: neurological manifestation of a systemic disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008, 27, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, O.; Rousié, D.; Jissendi, P.; Rousié, M.; Frankó, E. A new approach to corpus callosum anomalies in idiopathic scoliosis using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Spine J 2014, 23(12), 2643–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domenech, J.; García-Martí, G.; Martí-Bonmatí, L.; Barrios, C.; Tormos, J.M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Abnormal activation of the motor cortical network in idiopathic scoliosis demonstrated by functional MRI. Eur Spine J 2011, 20, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, J.E.; Conner, A.N.; Stephenson, J.B. Normal electroencephalograms in idiopathic scoliosis. Acta Orthop Scand 1986, 57, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukeschitsch, G.; Meznik, F.; Feldner-Bustin, H. Zerebrale Dysfunktion bei Patienten mit idiopathischer Skoliose [Cerebral dysfunction in patients with idiopathic scoliosis]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 1980, 118, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dretakis, E.K.; Paraskevaidis, C.H.; Zarkadoulas, V.; Christodoulou, N. Electroencephalographic study of schoolchildren with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988, 13, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinchuk, D.; Dudin, M.; Bekshayev, S.; Pinchuk, O. Peculiarities of brain functioning in children with adolescence idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) according to EEG studies. Stud Health Technol Inform 2012, 176, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gómez Cristancho, D.C.; Jovel Trujillo, G.; Manrique, I.F.; Pérez Rodríguez, J.C.; Díaz Orduz, R.C.; Berbeo Calderón, M.E. Neurological mechanisms involved in idiopathic scoliosis. Systematic review of the literature. Neurocirugia (Astur : Engl Ed) 2023, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Pérez, I.; Salamanca-Montilla, L.; Gámiz-Bermúdez, F.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Ibáñez-Vera, A.J.; Lomas-Vega, R. Vestibular Morphological Alterations in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Children 2023, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, D. Some effects of temporal-lobe damage on auditory perception. Can J Psychol 1961, 15, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, D. Functional asymmetry of the brain in dichotic listening. Cortex 1967, 3, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, D. From ear to brain. Brain and Cognition, 2011; 76, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, C.J.; Dowling, F.E.; Fogarty, E.E.; Moore, D.P. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis and Cerebral Asymmetry: An Examination of a Nonspinal Perceptual System. Spine 1995, 20, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enslein, K.; Chan, D.P. Multiparameter pilot study of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 1987, 12, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, B.; İnanç, G.; Elvan, A.; Selmani, M.; Çakiroğlu, M.A.; Akçali, Ö.; Satoğlu, İ.S.; Oniz, A.; Şimşek, İ.E.; Ozgoren, M. Investigation of the perceptual and cognitive asymmetry in the auditory system in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. S Afr J Physiother 2021, 77, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bless, J.J.; Westerhausen, R.; von Koss Torkildsen, J.; Gudmundsen, M.; Kompus, K.; Hugdahl, K. Laterality across languages: Results from a global dichotic listening study using a smartphone application. Laterality 2015, 20, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugdahl, K.; Westerhausen, R.; Alho, K.; Medvedev, S.; Laine, M.; Hämäläinen, H. Attention and cognitive control: unfolding the dichotic listening story. Scand J Psychol 2009, 50, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowell, P.; Hugdahl, K. Individual differences in neurobehavioral measures of laterality and interhemispheric function as measured by dichotic listening. Dev Neuropsychol 2000, 18, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuru Çolak, T.; Akçay, B.; Apti, A.; Çolak, İ. The Effectiveness of the Schroth Best Practice Program and Chêneau-Type Brace Treatment in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Long-Term Follow-Up Evaluation Results. Children (Basel) 2023, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, M.; Coetzee, W.; du Plessis, L.Z.; Geldenhuys, L.; Joubert, F.; Myburgh, E.; van Rooyen, C.; Vermeulen, N. The effectiveness of Schroth exercises in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. S Afr J Physiothery 2019, 75, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Aulisa, A.G.; Czaprowski, D.; Schreiber, S.; de Mauroy, J.C.; Diers, H.; Grivas, T.B.; Knott, P.; Kotwicki, T.; et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord 2018, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.; Turnbull, D.; Tournavitis, N.; Borysov, M. Treatment of Scoliosis-Evidence and Management (Review of the Literature). Middle East J Rehabil Health Stud 2016, 3, e35377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, HR. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) - an indication for surgery? A systematic review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil 2008, 30, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, J. R. Outline for the study of scoliosis. Instructional course lectures 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Reem, J.; Carney, J.; Stanley, M.; Cassidy, J. Risser sign inter-rater and intra-rater agreement: is the Risser sign reliable? Skeletal Radiol 2009, 38, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Aulisa, A.G.; Czaprowski, D.; Schreiber, S.; de Mauroy, J.C.; Diers, H.; Grivas, T.B.; Knott, P.; Kotwicki, T.; et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis and spinal disorders 2018, 13, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldfield, R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, K.S.; Littenberg. B. Dichotic Listening Test-Retest Reliability in Children. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2019, 62, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozgoren, M.; Erdogan, U.; Bayazit, O.; Taslica, S.; Oniz, A. Brain asymmetry measurement using EMISU (embedded interactive stimulation unit) in applied brain biophysics. Comput Biol Med 2009, 39(10), 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.R.; Lehnert-Schroth, C.; Moramarco, M. Schroth Therapy: Advances in Conservative Scoliosis Treatment; LAP Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbruecken, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, D. Cerebral dominance and the perception of verbal stimuli. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie 1961, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhausen, R.; Hugdahl, K. The corpus callosum in dichotic listening studies of hemispheric asymmetry: a review of clinical and experimental evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2008, 32, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Wang, D.; Chu, W.C.; Burwell, R.G.; Freeman, B.J.; Heng, P.A.; Cheng, J.C. Volume-based morphometry of brain MR images in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and healthy control subjects. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009, 30, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, L.; Chu, W.C.; Paus, T.; Cheng, J.C.; Heng, P.A. A comparison of morphometric techniques for studying the shape of the corpus callosum in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Neuroimage 2009, 15, 45–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuru, T.; Yeldan, İ.; Dereli, E.E.; Özdinçler, A.R.; Dikici, F.; Çolak, İ. The efficacy of three-dimensional Schroth exercises in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Clin Rehabil 2016, 30, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, M.C. The use of exercises in the treatment of scoliosis: an evidence-based critical review of the literature. Pediatr Rehab 2003, 6, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.R. The Effect of an Exercise Program on Vital Capacity and Rib Mobility in Patients with Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 1991, 1, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivett, L.; Stewart, A.; Potterton, J. The effect of compliance to a Rigo System Cheneau brace and a specific exercise programme on idiopathic scoliosis curvature: a comparative study: SOSORT 2014 award winner. Scoliosis 2014, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugdahl, K.; Carlsson, G.; Eichele, T. Age effects in dichotic listening to consonant-vowel syllables: interactions with attention. Dev Neuropsychol 2001, 20, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).