1. Introduction

In modern warfare, missile plays an important role in striking vital strategic target. With increasingly complex combat environment and drastic target maneuver, the missile requires to intercept the target accurately. The phase that mainly determines the interception accuracy is the terminal guidance phase (TGP). And the guidance law of the TGP has become a significantly supporting technology in guaranteeing the interception success and the performance of the interception system [1].

Generally, the objectives of the interception at the TGP are to avoid the escaping of the target and to make the minimum miss distance [2]. To achieve these objectives, many works have been reported. The proportional navigation guidance (PNG) laws for non-maneuvering targets were proposed in [3,4]. The reference [5] proposed the PNG law with the delayed line-of-sight angular rate (LOSAR) information. Recently, the parallel approaching guidance (PAG), a promising strategy that keeps the LOSAR remaining zero, receives more and more attention [6,7]. Under the PAG, the missile will possess more flat interception trajectory, and then, require less normal acceleration than that of the target. However, it still is a challenge to address the unknown maneuver of the target, and more efforts are necessary.

To address the interception issue of maneuvering targets, many methods have been reported. To ensure the low sensitivity to the target maneuver and other unknown things, the proportional-integral (PI) control based guidance law was adopted [8]. According to the robust control theory, the guidance law [9,10] was used to solve the problem of intercepting maneuvering target. In addition, the adaptive sliding mode guidance law was developed for intercepting of high speed and large maneuvering target [11,12]. However, all of the above were passive disturbance rejection methods. The robustnesses of these systems were realized at the expense of their nominal performance. Once the system requires high performance, the aforementioned methods may hardly meet the requirement.

Meanwhile, the active disturbance rejection method can estimate the bounded unknown disturbances efficiently, and compensate the observed disturbance to reduce its impact on the system [13]. Due to its advantages, the active disturbance rejection method is suitable for the system with control accuracy. Among them, the nonlinear disturbance observer (NDO) is an effective method which has been used in a lot of systems [14–17]. Furthermore, the NDO was used in guidance system to estimate the unknown target maneuver [18–21]. However, the target maneuvers were treated as the compound disturbances in the above works. With the relative distance decreases rapidly during the interception, the estimation accuracy will be affected. In light of all of these features, more efforts to design an NDO with higher estimation accuracy are necessary.

In addition, during the interception of the maneuvering targets, some constraints should be taken into consideration to ensure the system performance. It is usually required that the line-of-sight angle (LOSA) remains within a bounded area to guarantee the target remains in the seeker’s sight of view. To fulfill this requirement, some remarkable research results for the missile have been reported. The backstepping-based guidance law with the event-triggered (ET) was employed to make the LOSAR remain zero [7]. The SMC was adopted to intercept the maneuvering target with terminal LOSA constraint [19–22]. Nevertheless, the above works only consider the steady-state performance of the systems. More efforts to guarantee simultaneously the steady state and the transient performance are necessary.

As far as this is concerned, the prescribed performance control (PPC) which is proposed in [23] can make the tracking error remain zero. The maximum convergence time and the maximum overshoot does not exceed the preset values, which makes the transient performance better. Because of its feature, the PPC is employed to solve various kinds of control problems [24–27]. In particular, the PPC was used to stabilize the LOSA and its rate [28]. However, the traditional PPC guarantees that the system is stabilized as the control time goes to infinity. It is not an ideal method for solving control problem with the requirement of the convergence time such as the interception. Recently, the finite-time prescribed performance control (FPPC) was proposed to solve this problem [29–31]. But the disadvantage of the FPPC was that too larger overshoot makes the transient performance insufficient. To solve this problem, a novel FPPC which can adjust the bounds adaptively according to the positive or the negative of the initial error was proposed with small overshoot [32].

Based on the above motivation, this work proposes a PAG law to intercept the maneuvering target by using the FPPC. The target maneuver is estimated by the distance-scalar disturbance observer (DSDO) whose estimation accuracy is not affected by the relative distance. The objective is that to stabilize the LOSAR in the specified finite time and to make the minimum distance. In this study, the contributions and advantages are summarized in the following.

The FPPC is used to stabilize the LOSA to a small enough neighborhood of a given constant within a given time, so as to make the LOSAR converge to a small enough neighborhood of the origin within a given time. In this way, the time of the interception is shortened. With the help of the FPPC technique, there is a small overshoot in the convergence process.

The DSDO is employed to estimate the target’s unknown maneuver without estimating the relative distance. Consequently, the estimation accuracy of the DSDO is improved. The estimation is introduced into the control input, so as to reduce the adverse influence on interception accuracy.

The system stability is analyzed, which shows that the LOSAR and the estimation error are uniformly ultimately bounded (UUB). The effectiveness of the PAG law proposed is ensured.

The section arrangement is as follows. The relative kinematics equations in two-dimension are introduced in

Section 2. The DSDO and the FPPC-based PAG law are proposed in

Section 3. The signals of the interception system can guarantee UUB which is proved in

Section 4. To illustrate how PAG law works, the simulation results are given in

Section 5. Finally, the conclusion is given.

2. Problem Formulation and Preliminaries

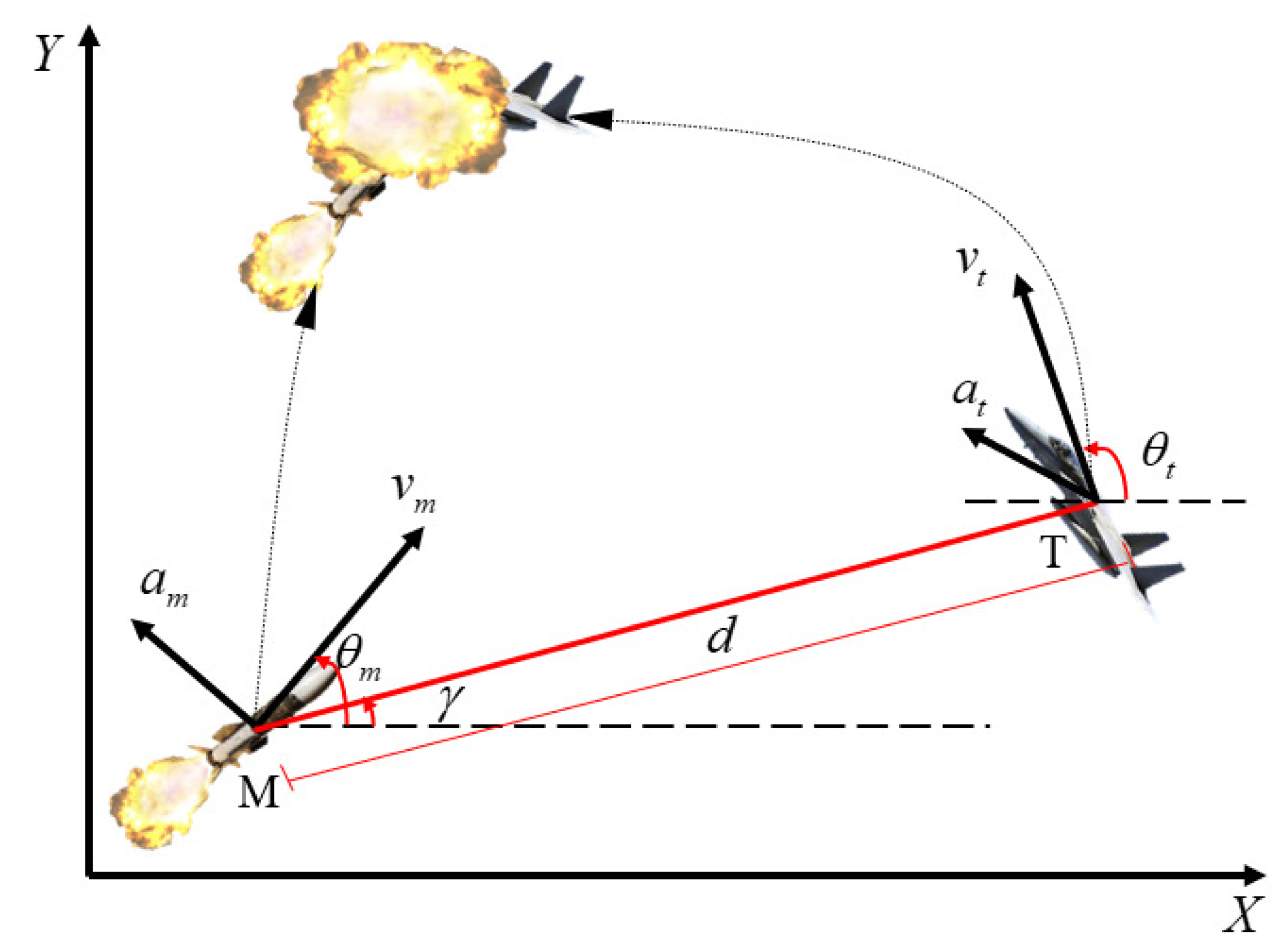

In this work, we simplify both the missile and the target to two particles which are denoted by M and T. To describe the relative motion dynamics, the relative states consist of the LOSA

, the LOSAR

, the relative distance

, and the relative velocity

.

is the missile’s flight-path angles (FPA).

is the target’s FPA. The velocities of the missile and the target are represented by

and

, respectively. Both the

and

are assumed to be constants. All of them can be measured by the seeker of the missile.

Figure 1.

Relative motion between the missile and the target in two-dimension system.

Figure 1.

Relative motion between the missile and the target in two-dimension system.

The relative kinematical equations of the missile-target are given as [33]

The kinematical equations of the missile are given as [33]

where

and

denote the

x-coordinate and

y-coordinate of the missile, respectively. The velocities along the

and

are

and

, respectively. The variable

denotes missile’s normal acceleration.

In the same way, the kinematical equations of the target are given as [33]

where

and

denote the

x-coordinate and

y-coordinate of the target, respectively. The velocities along the

and

are

and

, respectively.

represents the target’s normal acceleration. One thing is required to point out, all the states mentioned above except the target’s acceleration

can be measured by the seeker of the missile.

Considering (1), (3) and (5), the derivative of

is given as [33]

Thus, the relative kinematics equations are rewritten as [33]

where

is the target’s acceleration normal to the LOSAR. Because the

is unmeasurable,

is treated as the disturbance of the system.

The mention of this paper is to design the missile’s acceleration as the control input which can guarantee remain a sufficiently small neighborhood of zero. In other word, converge to a neighborhood of a suitable constant rapidly under the condition of the LOSA constraint, and simultaneously satisfy the performance indexes of state and control input. Then if the relative velocity is negative and the LOSAR is stabilized, the missile will finally intercept the target. Thus, to realize the PAG, we require to define the tracking error as .

The derivative of tracking error

respect to time is given as

In order to carry out follow-up work and take into account the actual situation, we have assumptions as follows:

Assumption 1: The target’s normal acceleration is continuous, bounded and differentiable. And satisfies , where is a constant.

Assumption 2 [35]: For the system (5), the LOSAR is controllable when

,

. So in the guidance process, the LOSA

, the FGA of target

and the FGA of the missile

remain in the feasible region

defined by

Remark 1 [34]: The guidance system (5) is unavailable when the relative distance . At the TGP, considering the limitations of physical factors such as the missile seeker and the receiver overload, there is a minimum distance , when , the guidance can be considered to end, then the missile and the target rely on their own inertia to complete the final guidance task.

Remark 2: Considering the field of view of the missile’s seeker and the performance of the interception, the LOSA is required to be always in the suitable region , where and are the lower and upper bounds of the region. In this feasible domain, the seeker can measure the system states informations at all times. If the LOSA does not belong to this region, it could cause the escaping of the target, and thus cause the failure of the interception mission.

3. Finit-Time Prescribed Performance and DSDO-based Guidance

In this section, the PAG is realized by using the DSDO and the FPPC. The unmeasured target-maneuver is estimated by the DSDO and the estimation is fed forward into the system. To improve the interception accuracy, an DSDO is designed whose estimation accuracy is regardless of the relative distance. The PAG law is proposed by using the FPPC, so that the LOSAR converges to the neighborhood of zero in the specified finite time. The rapidity performance and transient performance of the guidance system are ensured.

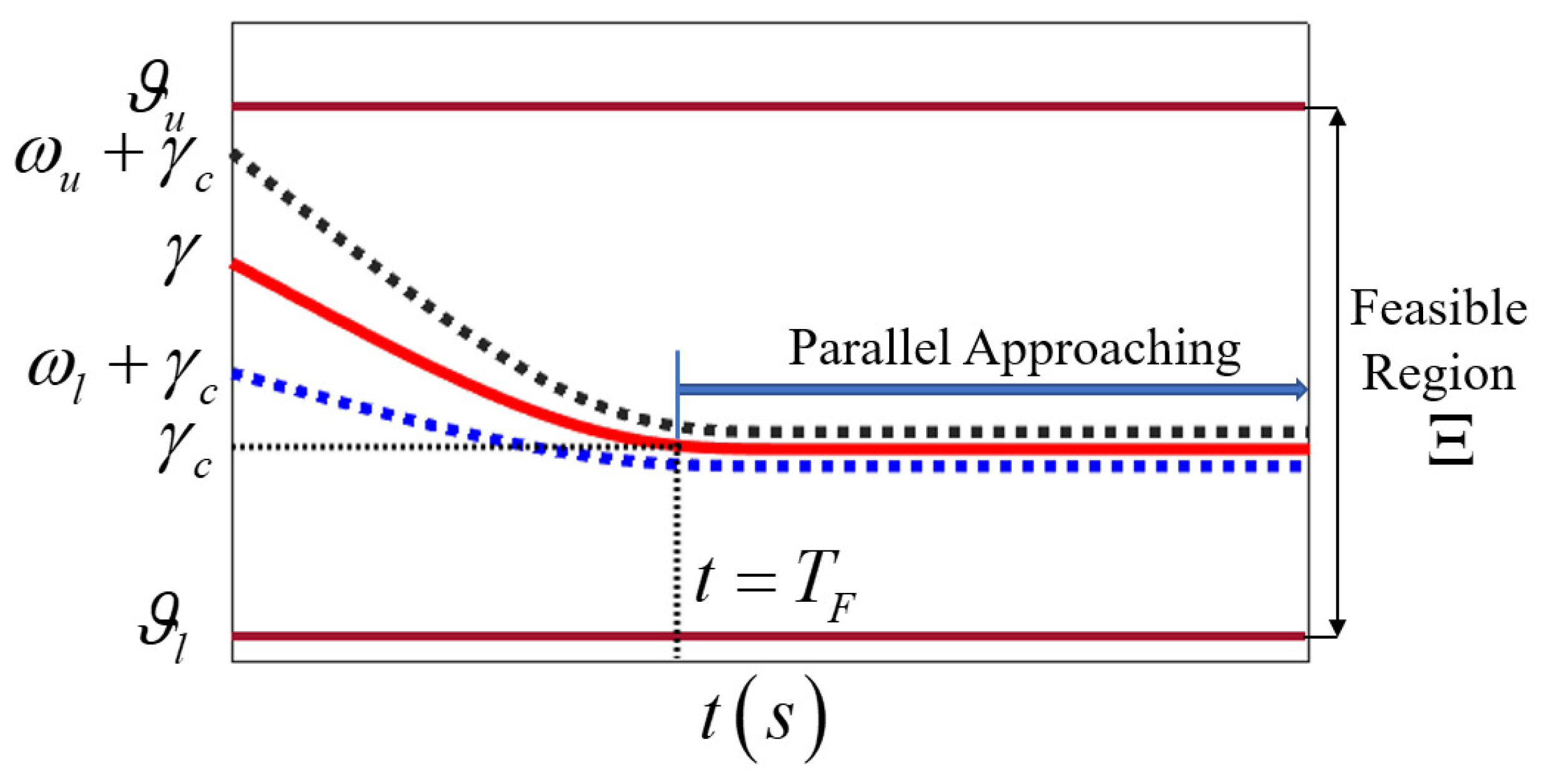

3.1. Finite-time Prescribed Performance

The faster the LOSAR converges, the better the rapidity of the guidance system. So FPPC is a suitable method in designing PAG law. In view of the disadvantage of large overshoot will affect the performance, a finite-time performance function (FTPF) is employed. Considering the seeker’s measurement area and the quality of the PAG, The LOSA error

converges to a bound region, constrained as follows:

where

and

are the FTPFs. Considering the issues mentioned above such as the seeker’s field of view, the choice of the FTPFs should satisfy the inequality which is given as

According to the advantages of the PPC, the LOSA is maintained in the region during the guidance process. The escaping of the target is avoided.

So the FTPFs

and

are choosen as [32]

where

,

,

,

,

,

and

are constants to be designed,

is the initial value of the LOSA error.

and

.The choice of all above parameters is required to ensure that the inequality (8) is valid.

Remark 3: The parameter determines the convergence speed of FTPFs. The specified finite time determines the convergence time of the LOSAR. In this way, the rapidity of the guidance system is ensured.

Due to the requirement to ensure that the LOSA error can converge before the end of guidance, attention should be paid to the selection of

. The time-to-go of PAG is given as

where

is the minimum distance.

To make the LOSA error converge at the suitable time, the value of

is approximately chosen as

where

is the initial value of the time-to-go,

is a suitable constant.

Remark 4: Since the signs of the FTPFs are related to the initial LOSA error, the sign of the LOSA error remains unchanged in the process of realizing the PAG. It will not only make the system have smaller overshoot, but also facilitate the seeker to measure the informations during the interception process. The improvement of measurement quality plays a pivotal role in the improvement of the interception accuracy.

To proceed further, the derivatives of

and

respect to time are given as

The second-order derivatives of FTPFs are given as

Based on the design flow of the prescribed performance, we convert

into the unconstraint error

which is expressed as [32]

where

satisfies

,

. Considering that the

is a monotonically increasing function of the LOSA error, any LOSA error

uniquely corresponds to an unconstraint error

. The task of controlling constrained error can be transformed into the task of controlling unconstraint error. In this regard, controlling an unconstrained error greatly reduces the difficulty of control. There is no need to worry about interception failure due to excessive absolute value of LOSA.

The derivative of

respect to time is given as

with

.

Now, the objective which is to converge the constrained one to the neighborhood of zero is transformed to stabilizing the unconstrained error .

3.2. Distance Scalar Disturbance Observer

Generally speaking, the unknown target maneuver is usually treated as the compound disturbance . However, when the missile nears the target, due to the extremely small relative distance, the derivative of the compound disturbance will approach infinity. Obviously, the estimation accuracy is seriously affected. Therefore, we project the target acceleration into the LOS coordinate frame and estimate the target’s acceleration normal to the LOSAR by designing an DSDO. The estimation accuracy is better which is regardless of the relative distance.

The DSDO is designed as

where

is a constant,

z is an intermediate variable, and

.

The derivative of

z is given as

Substituting (5) into (18) yields

The derivative of the disturbance

is given as

and then, substituting (1) and (3) into (20) yields

Recalling both

and

are constant and

, it is obtained that

Since the right side of the inequality sign consists of constant terms, the derivative of the disturbance is bounded.

Considering the stability of the DSDO, the error of estimation is defined as

The derivative of

developed as

where

is bounded and

. Thus, the estimation error will converge to a bounded region, the DSDO designed can track the unknown disturbance.

Remark 5: This paper provides a design idea of target maneuver estimation, which is not limited to the two-dimensional coordinate system. When considering the interception problem of maneuvering target in three-dimensional coordinate system, the target acceleration can still be projected to two components perpendicular to the line-ofsight (LOS) under the LOS frame. In this way, the decoupling of the disturbance and relative distance is realized, and the decline of the estimation accuracy is avoided when the missile is near the target.

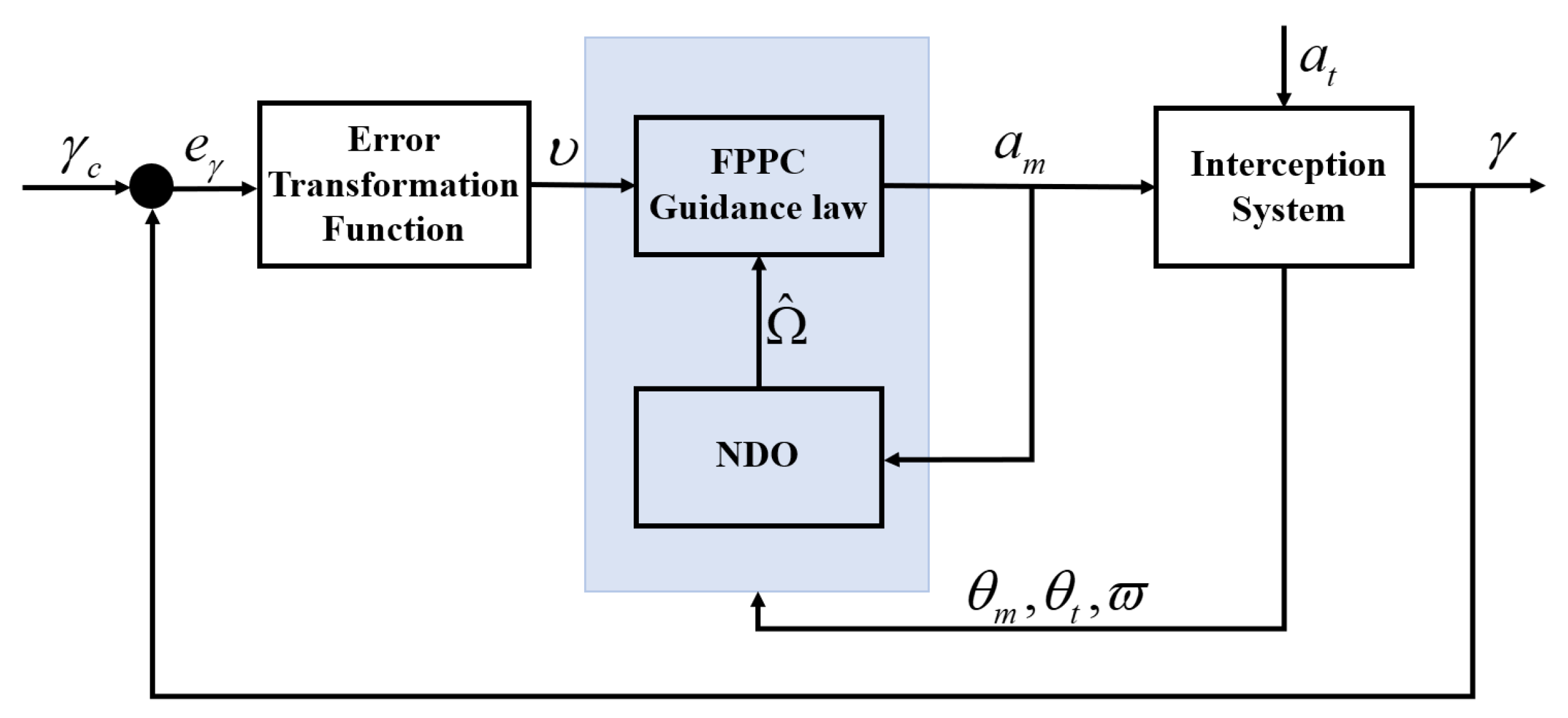

3.3. Parallel Approaching Guidance Design

Hereinbefore, the LOSA error

is converted to the unconstrained one

by the error transformation function, and the projected target acceleration is estimated by the DSDO using the system states. In order to achieve PAG, we use the system states and the estimation

to design PAG law which can stabilize

and input the PAG law into the interception system. The structure of the interception system of this paper is shown in the

Figure 2. Considering the principle of the PAG is making the LOSAR remain zero, the PAG law is obtained by using the method of backstepping. To proceed further, we define

,

, where

is a virtual law to be designed. To stabilize the transformed error, just like the common stability analysis process, we define

, and its derivative is given as

Design the stabilizing function

as

where

is a constant. In fact,

can be understood as the desired LOSAR, which can stabilize

.

Inserting (26) into (25) yields

We define the stability function as

To proceed further, the derivative of

is given as

The derivative of the variable

is given as

where

.

To stabilize the transformed error and the LOSAR, we design the PAG law as

where

is the stability term which will be mentioned below, and

is a regulation factor.

In this way, the LOSAR will stabilized within the given time

and remain a small enough neighborhood of zero until the end of guidance. The implementation mechanism of the PAG is shown in

Figure 3.

4. Stability Analysis

According to the principle of PAG, if the LOSA error and the estimation error can guarantee UUB, the feasibility of the guidance law can be verified. In this section, the stabilities of the LOSA error and the estimation error are analyzed. The analysis leads to the theorem as follows.

Theorem 1.

For the system (5), in presence of the DSDO (17) and the PAG law (30) based on the FPPC, the signal , and the estimation error are UUB and the PAG is realized when the constants , and n satisfy the conditions as

where which will be introduced in (33) is a regulation factor.

The text continues here. Proofs must be formatted as follows:

Proof (Proof of Theorem 1).

Considering the estimation error of the DSDO, we define the stability function of the guidance system (5) as

To discuss the role of the PAG law in stabilizing the signals

and

, we substitute (30) into (29), the derivative of

is rewritten as

Zooming the inequality (33) one has

As long as we can prove the boundedness of

, we can guarantee that

and

will be stabilized. Taking the derivative of (32) and substituting (24) into it, we can obtain

Similarly to (34), zooming the inequality (35) one has

Taking into account the above proof of the boundedness of

, we substitute the proof result (22) into (36). The derivative of the stability function

V is rewritten as

where

and

C is given as

If , and n satisfy the consition (31), , the signals , and are uniformly untimately bounded. That means the system (5) will finally be stabilized with the guidance law. This completes the proof. □

5. Simulation Results

To prove the feasibility of the PAG law, three Scenarios are considered in this section. The selections of the initial system states and the controller parameters are given in Tables 1 and 2. The simulation results of three Scenarios are as follows.

Table 1.

The initial values of the guidance system states.

Table 1.

The initial values of the guidance system states.

| System states |

Initial value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

Table 2.

The values of the controller parameters.

Table 2.

The values of the controller parameters.

| System states |

Initial value |

|

3 |

|

10 |

| n |

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

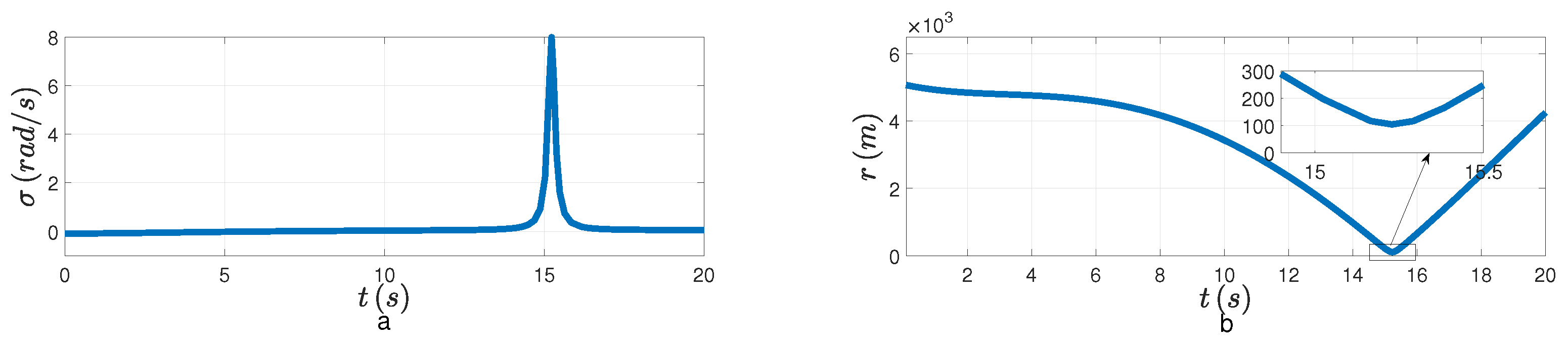

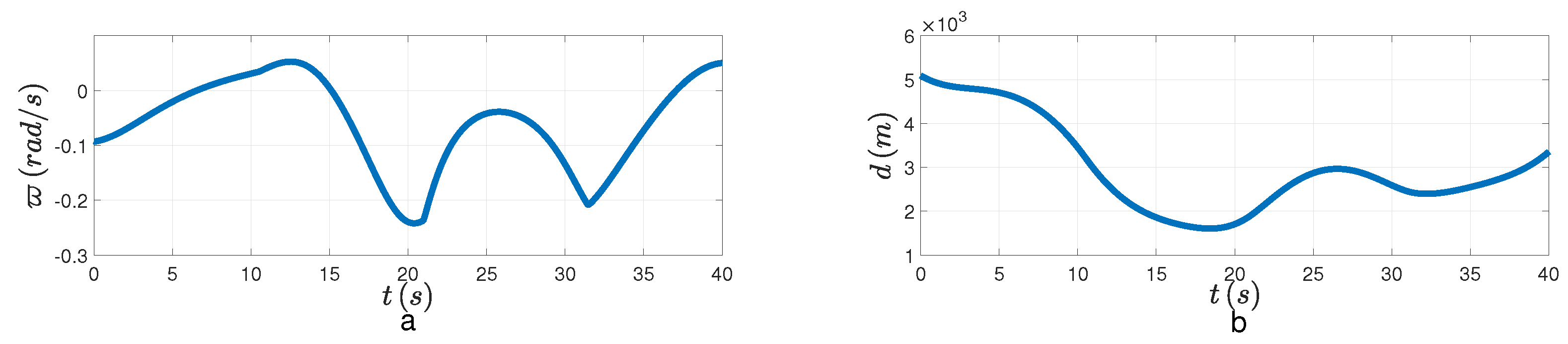

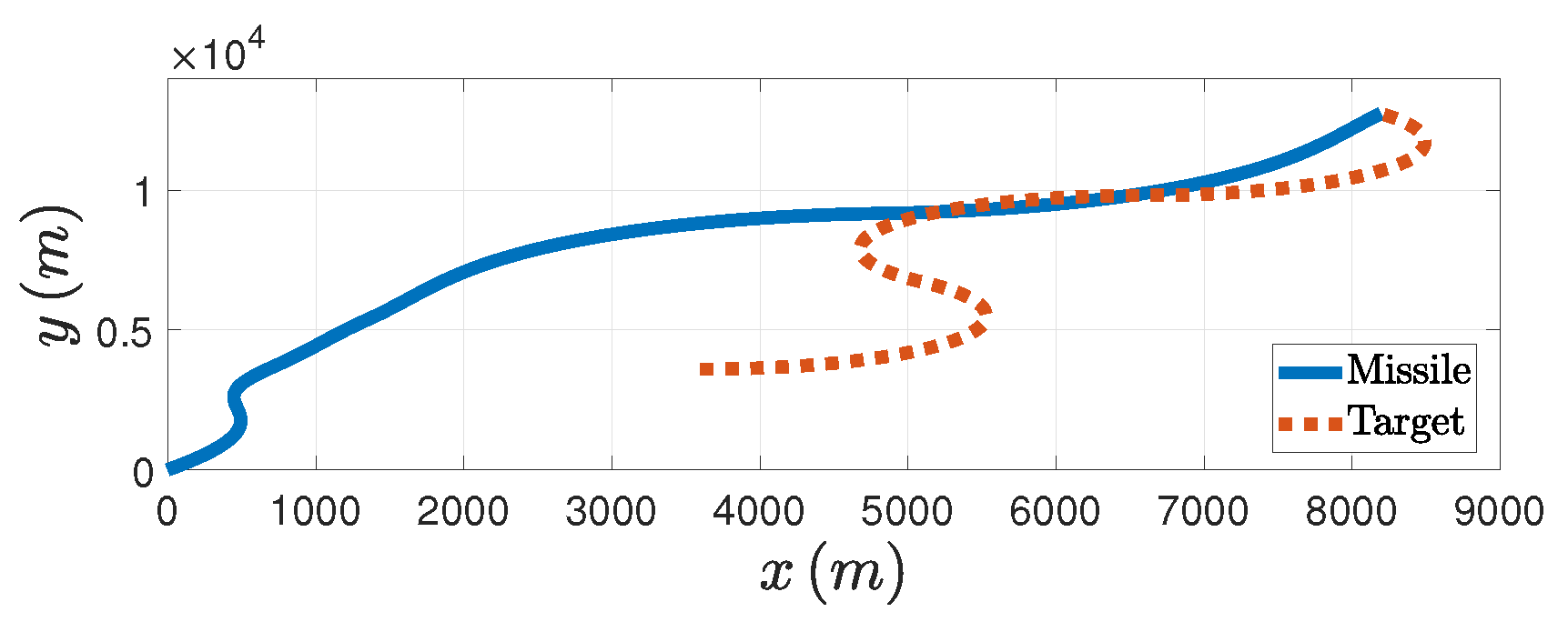

Scenario 1 (

Constant Acceleration): The acceleration of the target is given by

. Considering the target for a circular maneuver,

, when

. It’s apparent that the LOSAR is not stabilized, and the minimum distance cannot be reached in

Figure 4. That means the interception is unsuccessful when

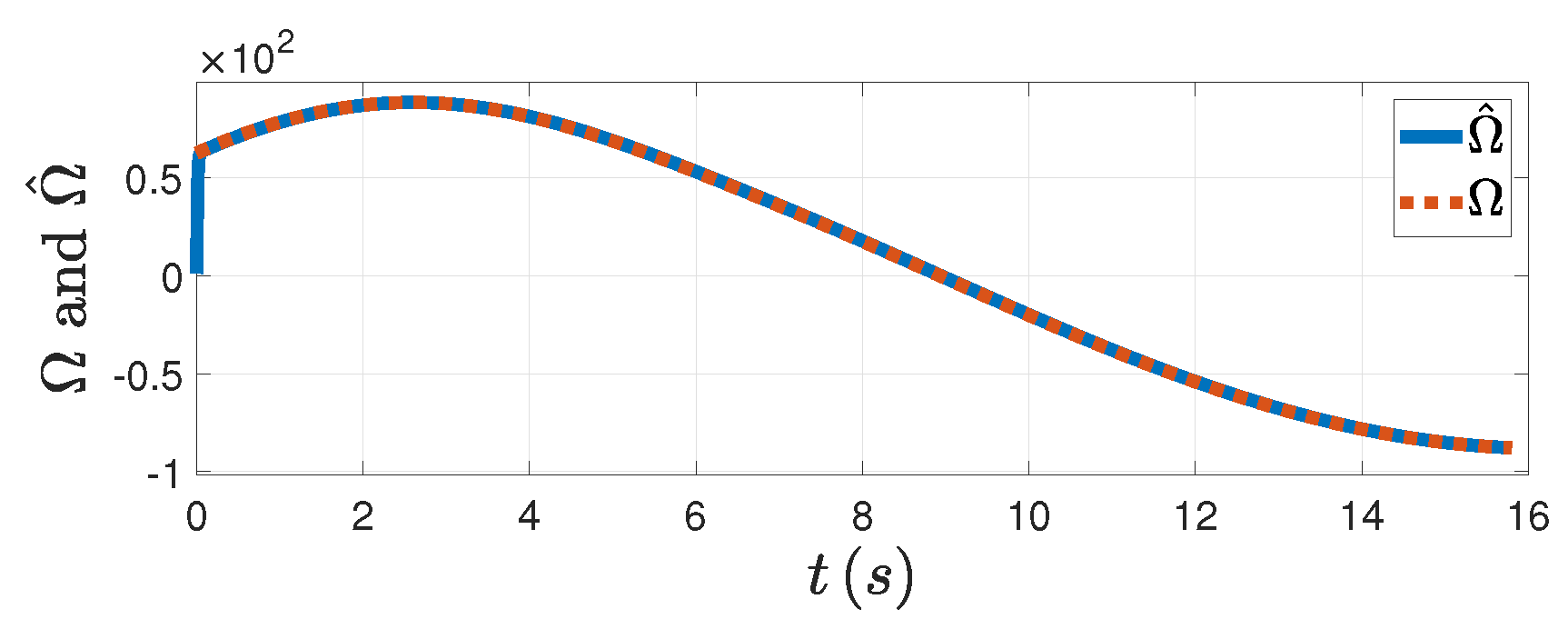

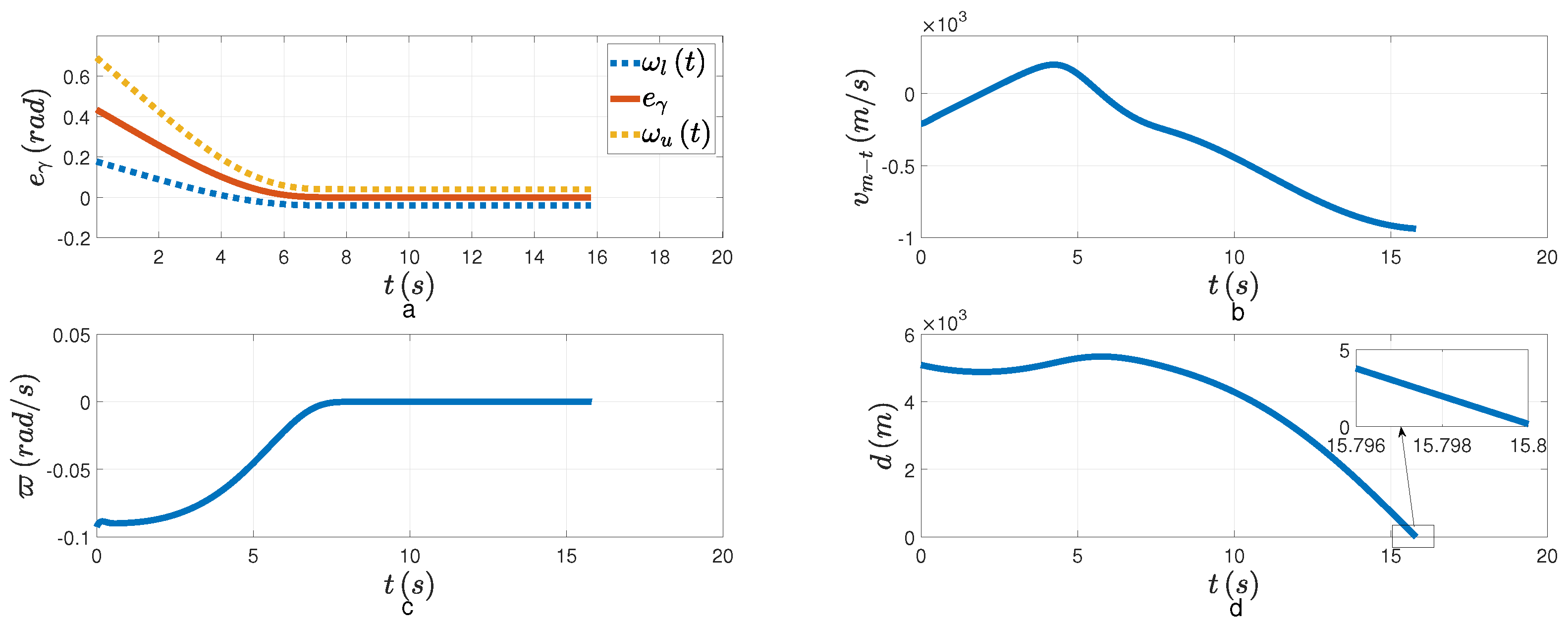

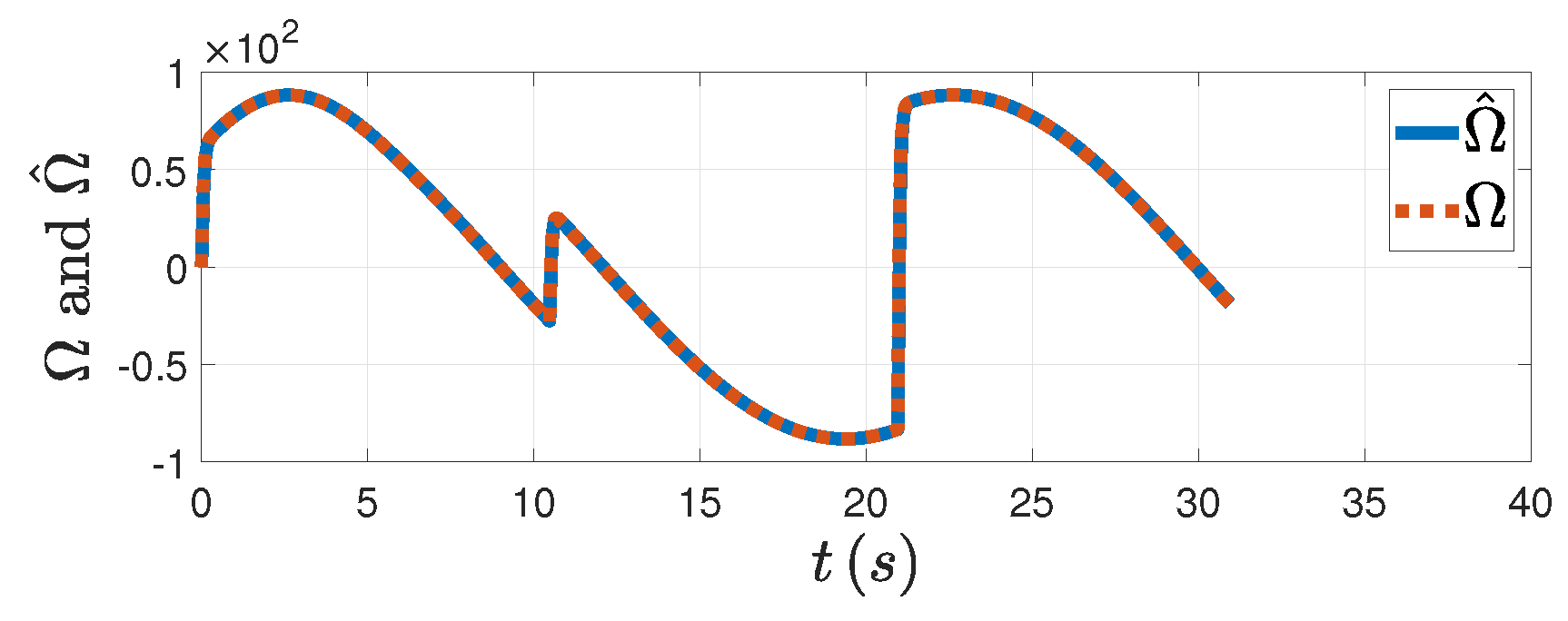

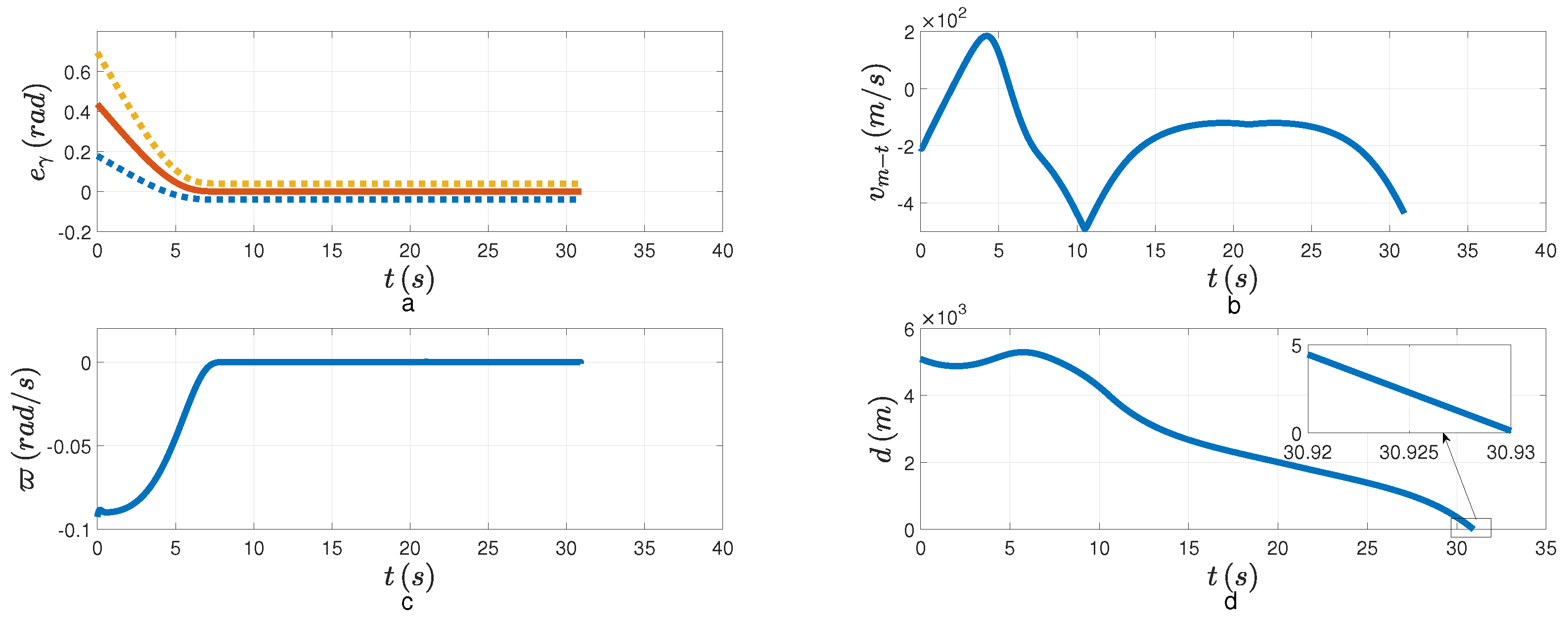

. Then we feed the FPPC-based guidance law into the system. From

Figure 5, the DSDO can track the target’s maneuver well with the PAG law designed. From

Figure 6a,c, both the tracking error and the LOSAR are stabilized with the FPPC in the specified finite time

. The overshoot of tracking error is small. If the relative velocity is negative, that is,

, when the LOSAR remains a small enough neighborhood of origin, the PAG will be realized. From

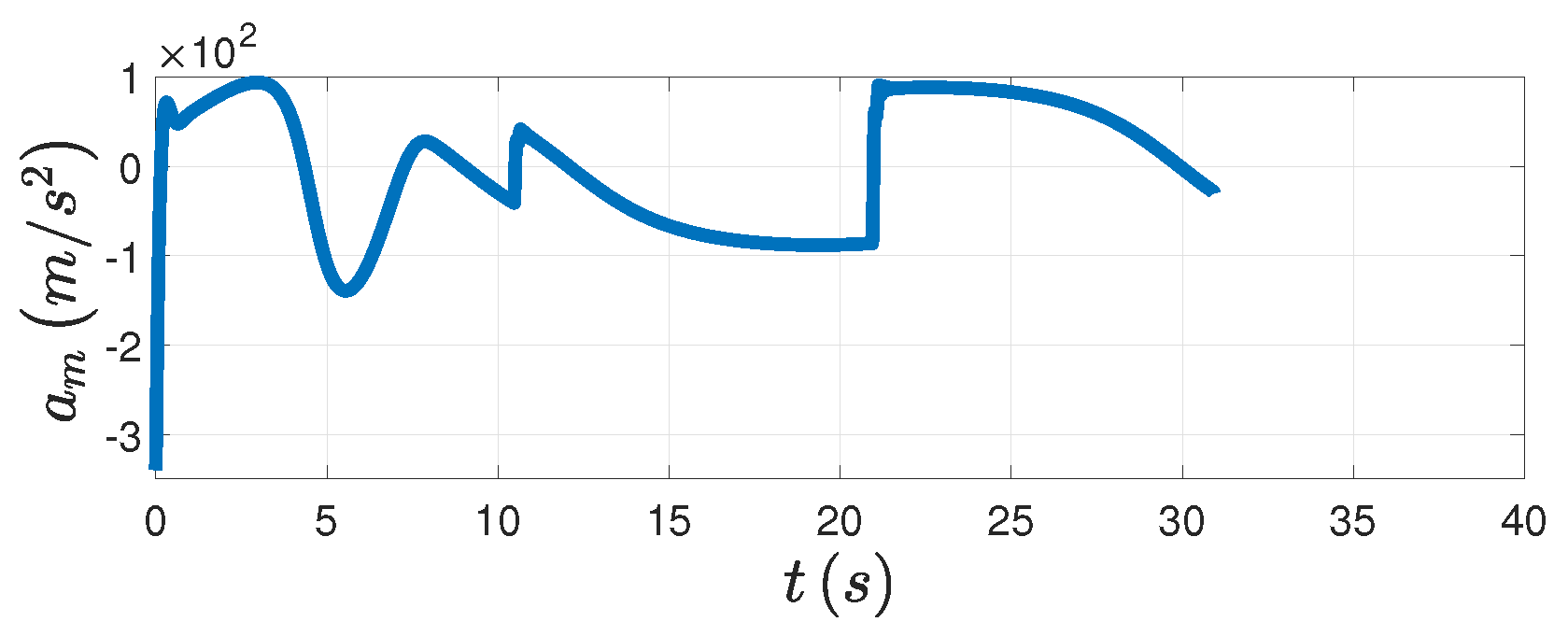

Figure 6b, the relative velocity is negative when the LOSAR is stabilized. In

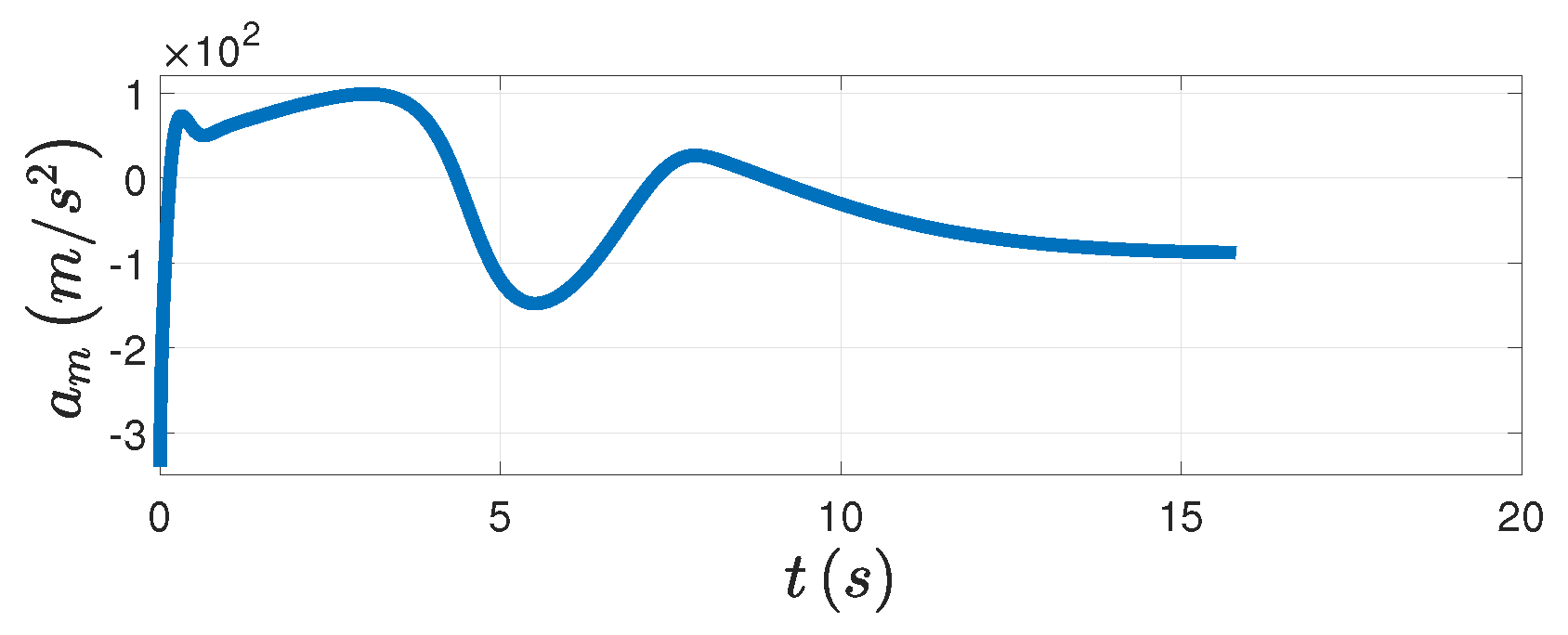

Figure 6d, the relative distance finally converges to the minimum distance. The PAG law is presented in

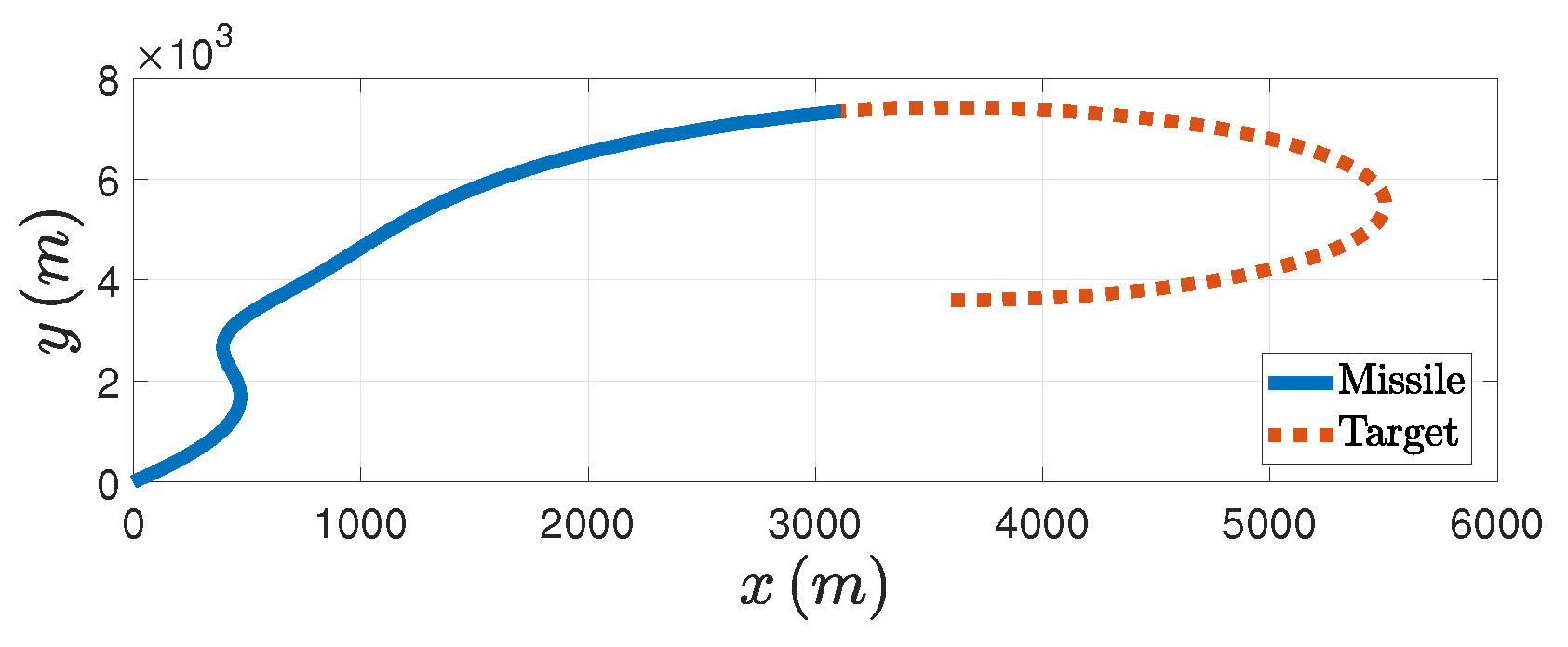

Figure 7. In addition, from the

Figure 8 we can see the trajectories of both the missile and the target. Therefore, the effectiveness of the PAG law is illustrated when the target does the circular maneuver.

Scenario 2 (

Sine Acceleration): The acceleration of the target is set as

. For follow-up comparison, we consider the situation that

. It’s apparent that the LOSAR is not stabilized, and the minimum distance cannot be reached in

Figure 9. That means the interception is unsuccessful when

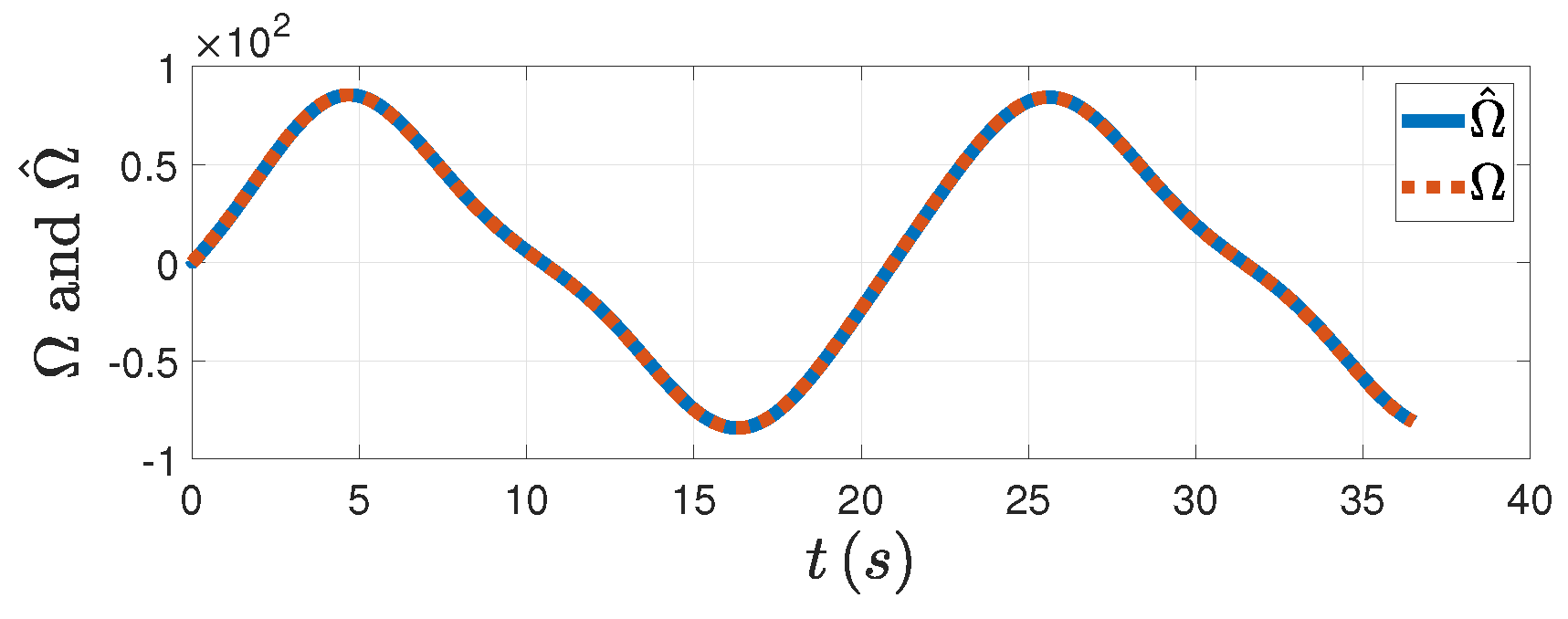

. From

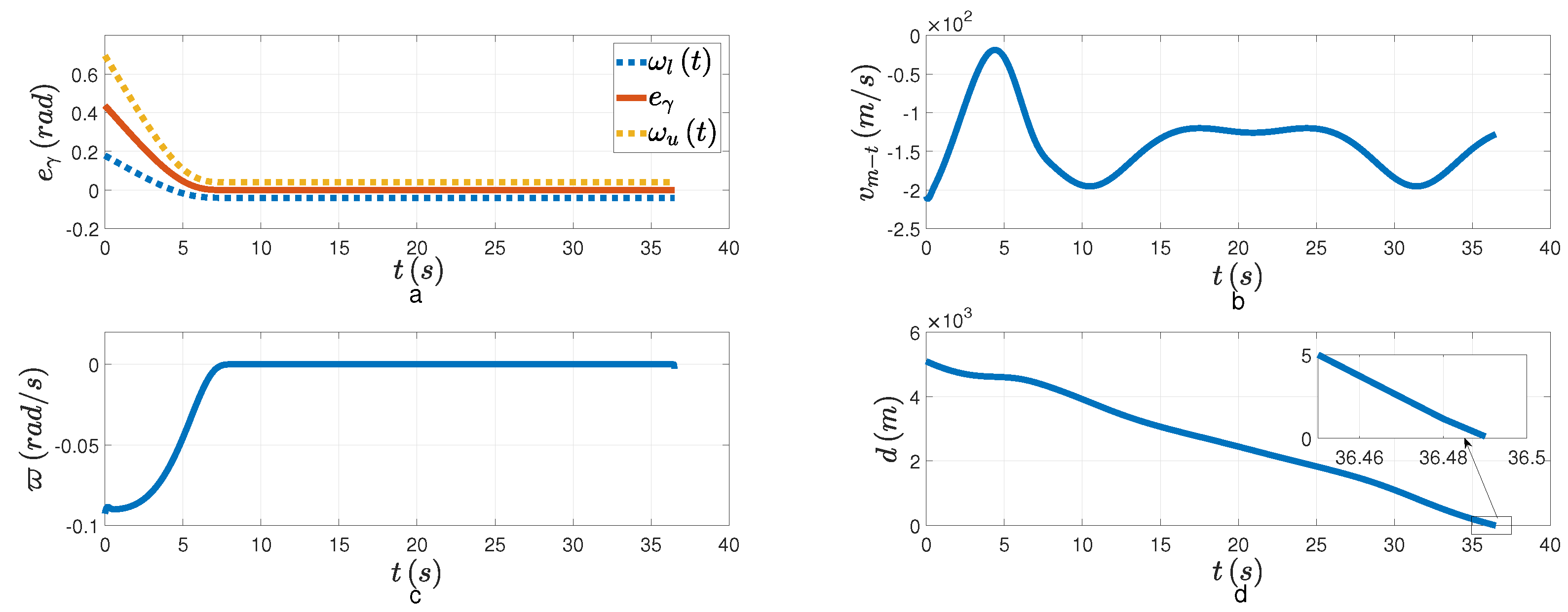

Figure 10, the DSDO can track the target’s maneuver well with the PAG law. From

Figure 11a,c, both the tracking error and the LOSAR are stabilized with the FPPC in the specified finite time

. The overshoot of tracking error is small. From

Figure 11b, the relative velocity is negative when the LOSAR remains the neighborhood of zero. In

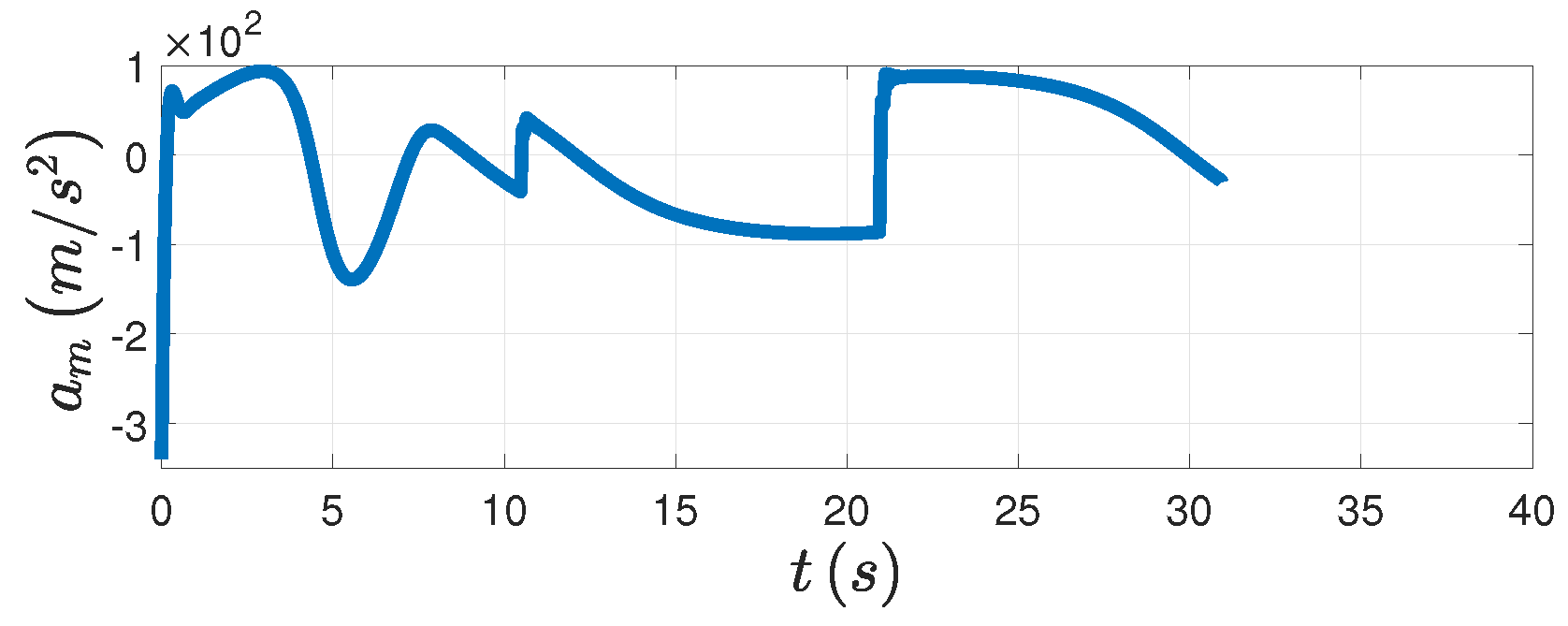

Figure 11d, the relative distance finally converges to the minimum distance. The PAG law is shown in

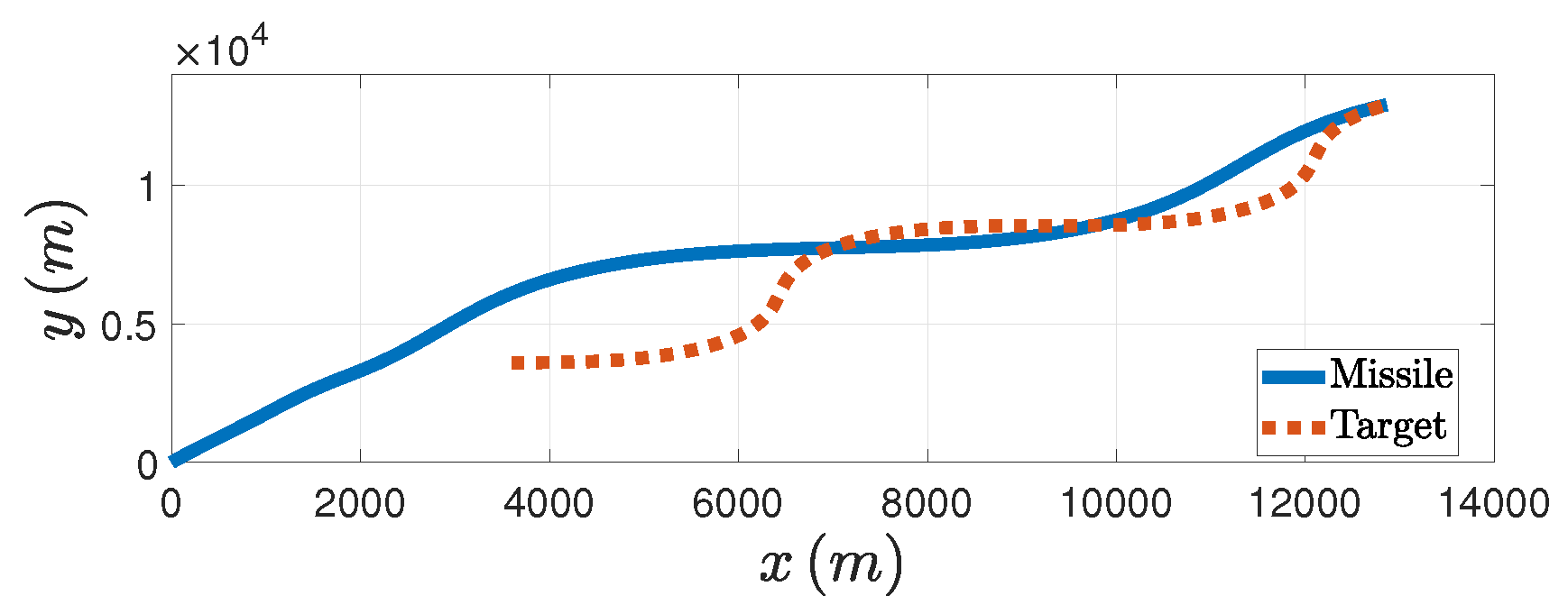

Figure 12. In addition, from the

Figure 13 we can see the trajectories of both the missile and the target. Therefore, the effectiveness of the PAG law is illustrated.

Scenario 3 (

Square-Like Acceleration): The acceleration of the target

is given by a square-like signal, the amplitude of the signal is

, and the frequency is

. Considering the target for a square like maneuver when

, the LOSAR and the relative distance are shown in

Figure 14. The interception is unsuccessful when

. From

Figure 15, the DSDO can track the target’s maneuver well with the PAG law. From

Figure 16a,c, both the tracking error and the LOSAR are stabilized with the FPPC in the specified finite time

. By the way, the overshoot of tracking error is small. From

Figure 16b, the relative velocity is negative when the LOSAR remains a small enough neighborhood of zero. In

Figure 16d, the relative distance finally converges to the minimum distance. The PAG law is shown in

Figure 17. In addition, from the

Figure 18 we can see the trajectories of both the missile and the target. Therefore, the effectiveness of the guidance law is illustrated when the target does the square like maneuver.

5.1. Conclusions

In this study, the PAG for missile by using the FPPC is proposed. To eliminate the uncertainty of unknown maneuvering target acceleration, the DSDO has been developed. Specifically, the estimation accuracy of the DSDO is regardless of the relative distance. Then in order to realize the PAG, the FPPC is used to ensure the LOSAR converges to neighborhood of zero in the specified finite time and to make it remain zero during the interception. In this way, the rapidity of interception system is also improved. All signals of the interception system can guarantee UUB and the feasibility of the PAG law is illustrated by simulation results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and K.Y.; methodology, H.S.; software, H.S.; validation, H.S.; formal analysis, H.S.; investigation, H.S.; resources, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, K.Y. and Y.S.; supervision, k.y.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TGP |

Terminal guidance phase |

| PNG |

Proportional navigation guidance |

| LOSAR |

Line-of-sight angular rate |

| PAG |

Parallel approaching guidance |

| PI |

Proportional-integral |

| NDO |

Nonlinear disturbance observer |

| LOSA |

Line-of-sight angle |

| ET |

Event-triggered |

| PPC |

Prescribed performance control |

| FPPC |

Finite-time prescribed performance control |

| UUB |

Uniformly ultimately bounded |

| FPA |

Flight-path angle |

| DSDO |

Distance-scalar disturbance observer |

| FTPF |

Finit-time performance function |

References

- Yang, B.; Jing, W.; Gao, C. Three-dimensional cooperative guidance law for multiple missiles with impact angle constraint. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2020, 31, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Pokiya, J.; Sharma, P.; Padhi, R. High-precision computational guidance in terminal phase with impact angle, lead angle and lateral acceleration constraints. J Franklin Inst 2022, 359, 10392–10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ghose, D.; Raha, S. Capturability analysis of a 3-D retro-PN guidance law for higher speed nonmaneuvering targets. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2014, 22, 1864–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, G. State estimation with a destination constraint imposed by proportional navigation guidance law. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst 2022, 58, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhananjay, N.; Lum, K.-Y.; Xu, J.-X. Proportional navigation with delayed line-of-sight rate. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2013, 21, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Event-triggered-backstepping-based parallel approaching guidance method for maneuvering target interception. Technical Committee Guidance Navigation and Control 2022, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Liu, C. Event-based optimal guidance laws design for missile-target interception systems using fuzzy dynamic programming approach. ISA Trans 2022, 128, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Lee, C.-H. Optimal proportional-integral guidance with reduced sensitivity to target maneuvers. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst 2018, 54, 2568–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-D.; Chen, H.-Y.; Padhi, R. Three-dimensional nonlinear H∞ guidance law. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control. 2001, 11, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-S.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Lin, C.-L. Nonlinear fuzzy H∞ guidance law with saturation of actuators against maneuvering targets. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2002, 10, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Mu, C.; Xu, W. Adaptive sliding-mode guidance of a homing missile. J Guid Control Dyn 1999, 22, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, D.; Zhang, X.; He, K.; et al. A new three-dimensional adaptive sliding mode guidance law for maneuvering target with actuator fault and terminal angle constraints. Aerosp Sci Technol 2022, 131, 107974. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Liu, C.; Feng, X.; et al. Visual servoing of flying robot based on fuzzy adaptive linear active disturbance rejection control. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2021, 68, 2558–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; He, F.; Yao, Y. Estimation of target maneuver acceleration and guidance law implementation in homing terminal guidance. J. Aeronaut. 2009, 30, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Ri, S.; Liu, L.; et al. Nonlinear disturbance observer-based dynamic surface control of mobile wheeled inverted pendulum. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2015, 23, 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; et al. A novel assorted nonlinear stabilizer for DC–DC multilevel boost converter with constant power load in DC microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 11181–11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shi, P.; Lim, C.-C. Adaptive neural fault-tolerant control of a 3-DOF model helicopter system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2016, 46, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J. Qualitative indicator-based guidance scheme for bank-to-turn missiles against couplings and maneuvering targets. Aerosp Sci Technol 2020, 106, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Luo, S. Terminal guidance laws of missile based on ISMC and NDOB with impact angle constraint. Aerosp Sci Technol 2013, 31, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; et al. Output feedback continuous terminal sliding mode guidance law for missile-target interception with autopilot dynamics. Aerosp Sci Technol 2019, 86, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harl, N.; Balakrishnan, S.N. Impact time and angle guidance with sliding mode control. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2012, 20, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Ghose, D. Terminal impact angle constrained guidance laws using variable structure systems theory. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2013, 21, 2350–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechlioulis, C.P.; Rovithakis, G.A. Prescribed performance adaptive control of SISO feedback linearizable systems with disturbances. 2008 16th Mediterranean Conf. Control Automat., Ajaccio, France, June 2008; pp. 1035–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Celler, B.G.; et al. Neural adaptive backstepping control of a robotic manipulator with prescribed performance constraint. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2019, 30, 3572–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.; Hu, Q.; Shi, Y.; et al. Fault-tolerant prescribed performance attitude tracking control for spacecraft under input saturation. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 2020, 28, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, G. Event-triggered prescribed performance control for a class of unknown nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 6576–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimanidis, I.S.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Rovithakis, G.A. Output feedback approximation-free prescribed performance tracking control for uncertain MIMO nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2020, 65, 5058–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.; Chen, M.; Wu, Q. Noncertainty-equivalent observer-based noncooperative target tracking control for unmanned aerial vehicles. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2022, 65, (5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Jing, Y.; et al. A novel finite-time adaptive fuzzy tracking control scheme for nonstrict feedback systems. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst 2019, 27, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Chen, C.L.P.; Tong, S. A novel adaptive NN prescribed performance control for stochastic nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2021, 32, 3196–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, X.; Jing, Y. A novel finite-time prescribed performance control scheme for spacecraft attitude tracking. Aerosp Sci Technol 2021, 118, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Qi, Q.; Jiang, B. A simplified finite-time fuzzy neural controller with prescribed performance applied to waverider aircraft. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst 2022, 30, 2529–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, C. Backstepping-based adaptive dynamic programming for missile-target guidance systems with state and input constraints. J Franklin Inst, 2018, 355, 8412–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, C. Backstepping-based adaptive predictive optimal control of nonlinear systems with application to missile–target engagement. ISA Trans 2018, 83, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; et al. Guidance law against maneuvering targets with intercept angle constraint. ISA Trans 2014, 53, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).