1. Introduction

Surface effects are important for characterization of the surface properties that are essentially different from those observed in the bulk of the material, and are significant since the materials interact with the environments through their surfaces. In strongly anisotropic systems, the surface effects behave quite differently and are more complex than in isotropic systems. For example, the layered organic materials are characterized with a strong anisotropy due to their reduced dimensionality which makes them interesting for studying the surface phenomena, especially in tilted magnetic fields, since their properties strongly depend on the plane of field rotation. The interest in investigation of rather complex surfaces of such materials is increasing mostly due to their importance for various scientific and industrial applications. The investigation of the surface influence in anisotropic layered materials will allow not only for more accurate determination of characteristic parameters necessary for more precise Fermi surface reconstruction in such materials but also for determining some of the quantities typical for surface electrons. This refers to a wide class of materials such as organic conductors, high-Tc cuprates, dichalcogenides of transition metals and other similar materials with a layered structure. The surface electrons are moving along so called skipping trajectories positioned very closely to the surface itself in the skin layer of the conductor. Their velocity is essentially parallel to the surface thus having an important contribution to the surface currents.

Organic layered conductors, based on charge transfers salts and known for its rich physics and multi-functionalities,[

1] represent a large class of materials utilized for building organic electronic devices. Their interest for applications is increasing significantly due to their importance as an active layer in fabrication of the organic bilayer films used for development of flexible electronic sensors. These films are simple and low-cost to fabricate, and are characterized with a high-performing multi-functionality at room temperatures. By far, several charge transfer salts have been confirmed to act as active materials including but not limited to those based on BEDT-TTF[

2,

3], BEDO-TTF[

4,

5], MDF-TSF[

6] donor molecules with various possible acceptors such as

[

2,

3],

[

7],

[

8]. As the size of the devices developed nowadays reduces, the surface-environment interactions become crucial for the device performance. As in that case the surface effects become more prominent, this emphasizes even more the need for studying these effects. Some of them can be beneficial for applying in organic electronic devices which can pave the way for realization of new applications that will create opportunities for development of new technology based on the organic layered compounds. In order to understand and properly exploit the surface transport phenomena in organic bilayer films for achieving better device performance, the behaviour of these effects in the organic material itself which is used as an active layer in fabrication of the bilayer films must be understood well. Indeed, the experimental investigation of photoemission spectra of quasi-1D organic conductors has shown that electronic correlations in the valence band spectra are strongly affected by surface effects and may even be completely obscured [

9].

The surface impedance of the material is the proper quantity to measure in order to describe the material’s response to an external electromagnetic microwave/millimeter field. For molecular conductors, such measurements might give further insights in the understanding of the rapid oscillations of the magnetoresistance as well as additional information on the dynamical properties of various ordered states occurring in these materials. For example, some previous works on microwave surface impedance measurements performed in the quasi-1D organic conductor

at 16.5 GHz show that the transition from the metallic to the field-induced spin-density-wave state is not as sharp as previously observed in the dc regime (see Ref. [

10] and references therein).

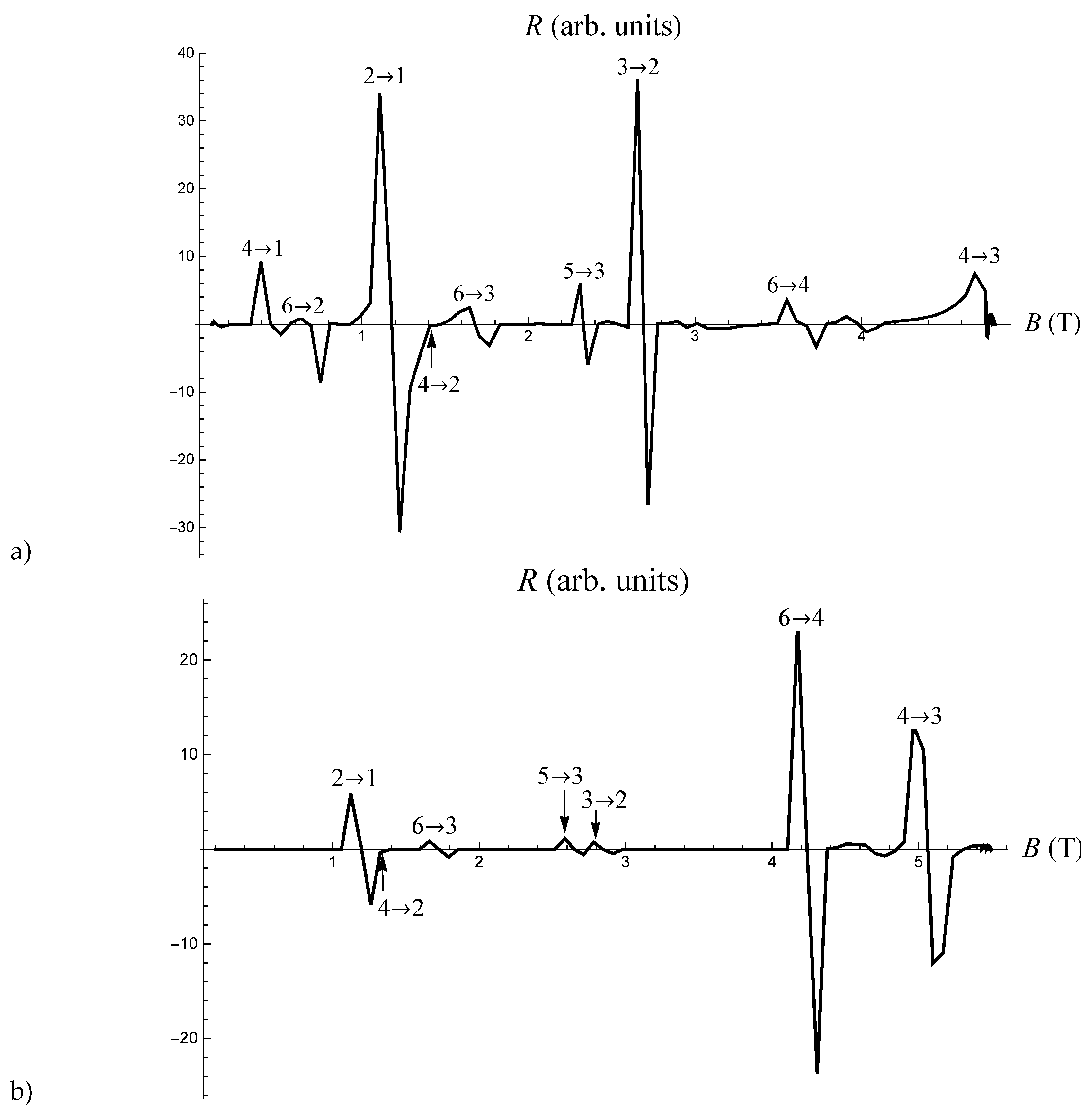

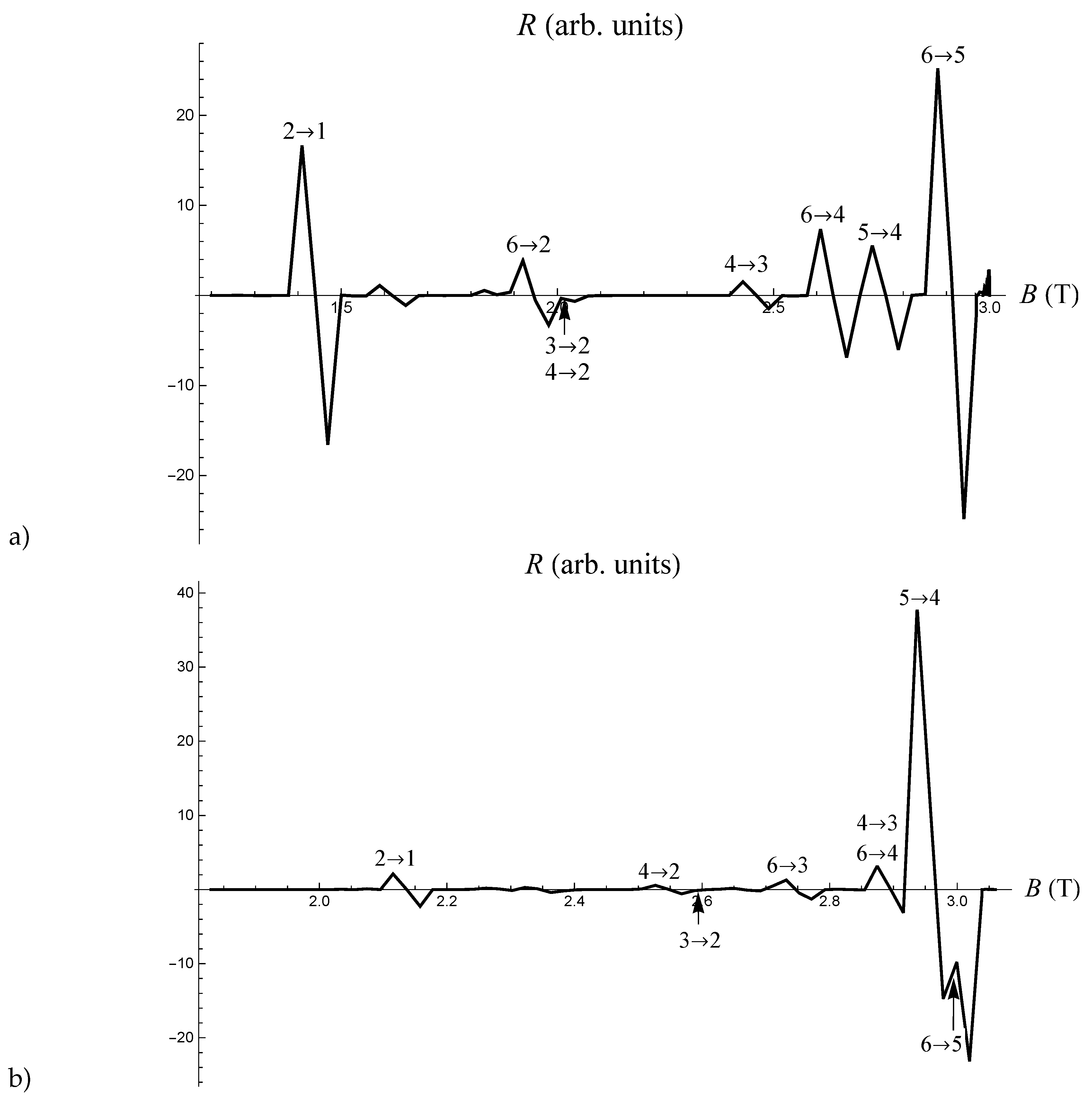

In this letter, we investigate the microwave properties of layered organic conductors through the numerical analysis of the surface resistance derivative for both out-of plane and in-plane magnetic field. The differences in surface properties in these materials in correlation to the different planes of rotation of the magnetic field are discussed through the changes in resonance spectra of surface resistance derivative.

2. Theoretical aspects of the surface impedance derivative calculation

The magnetic oscillation spectrum of surface resistance derivative in a non-tilted in-plane magnetic field has been recently studied in detail in Ref. [

11]. Here we extend the calculations to the case of a tilted magnetic field in order to examine how the change of the surface-state energies and geometric characteristics of the skipping trajectory affect the appearance of the resonances in the spectrum. The expressions for the surface resistance derivative for two magnetic field geometries, out-of-plane and in-plane field rotations, will be given. The corresponding surface-state energies and wave functions necessary to numerically calculate the oscillation spectrum are taken from Ref. [

12,

13]. We will first calculate the surface resistance derivative for an out-of-plane magnetic field as this configuration involves more steps to determine the matrix elements of the electric field due to their dependence on the electron momentum projection on the magnetic field

.[

12] This dependence significantly affects both the shape and amplitude of the resonances in the spectrum. The corresponding expression in case of a tilted in-plane magnetic field is similar to that obtained for a non-tilted in-plane field[

11] due to negligibly small dependence of matrix elements on

. The angular dependence of matrix elements is determined only by the angular dependence of the surface wave functions at a given plane of rotation of the magnetic field [

12,

13].

The surface impedance derivative for an electric field polarized in the

x direction and propagating along the normal to the plane of the layers in an organic conductor,

, is calculated using the formula[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]

Here

is the non-resonant part of surface impedance where

,

are the electric field strength and its derivative at the surface,

is the vacuum permeability.

is the Fermi momentum. The term

takes into account the effect of finite lifetime on the surface states due to phonon scattering.[

18] In that regard,

is the mean-free time between successive phonon scattering events.

and

are the frequency of the incident electric field and the difference frequency of two surface states with quantum numbers

m and

n. The sum over

m and

n takes into account the contribution from all pairs of surface states involved in the formation of the resonance spectrum.

are the matrix elements of the electric field

that depend on the form of the electric field and surface wave functions

which are in general functions of the distance from the surface

z, the magnetic field magnitude

B and the tilt angle between the magnetic field and conductor’s surface

,

,

In addition to the above equations, the complete system of equations necessary to obtain the expression for the surface resistance derivative consists of the equation for the electric field, the Boltzmann’s transport equation[

19] and the equation for the current density

where

is a coordinate in momentum space, which indicates the position of a charge on its trajectory in a magnetic field in accordance with the equations of motion

and

is the non-equilibrium correction to the equilibrium Fermi distribution function

[

19].

We consider an electric field propagating along the normal to the surface of a conductor in the half-space

. Using the Fourier method, we continue the electric field

evenly to the region of negative values of

z and obtain the following relation for the Fourier component

The Fourier component of the in-plane electrical conductivity

can be obtained by using the Fourier component of the transport equation solution (Eq.

4)

where

.

The corresponding expression that determines the in-plane electrical conductivity is then written as

To further proceed with the calculations, it is convenient to transfer to new variables, i.e., from

and

to those that describe electron’s motion in the presence of an external magnetic field such as the energy

, electron momentum projection on the magnetic field direction

and time

t. This is correlated with the specific form of the energy spectrum of quasi-two dimensional organic conductors in the form

as obtained by using the tight-binding approximation [

1]. The introduction of the new variables is indeed convenient, as in a tilted magnetic field the closed orbits on Fermi surface are obtained as cross-sections on the Fermi surface by the plane

,

const. In the above equation,

and

are the electron momenta components in the plane of the layers, and

is the momentum component along the least conductive axis of the conductor that is normal to the plane of the layers.

is the electron effective mass in the plane of the layers,

is the hopping transfer integral in the interlayer direction,

c is the interlayer distance and

ℏ is the Planck constant divided by

.

The change of variables yields the term

in the expression for

thus transforming Eq.

8 into the following one

where

is the electron cyclotron frequency and

. The integration over

yields -1 since

where

is the chemical potential. In addition, since

,

,

and

one can calculate the integrals over

and

t and arrive to the following relation for

where

and

Here

,

where

is the Fermi velocity.

In order to calculate the matrix elements

, the form of the electric field

appropriate for the moderate anomalous skin-effect regime (

) is required. This is because, in organic conductors, the electronic surface states are in general confined in the thin layer of a width

near the surface. Their wave functions are attenuated at a distance smaller than

[

12,

13,

20] signifying that the condition

is satisfied, in general, but constrained only to the small region close to the surface. This allows to keep only the term

in the square root and the terms up to

in the power series expansion of the function

in

. Considering a specular reflection of the electrons from the surface, the expression for the Fourier component of electrical conductivity,

, is obtained as follows

where

.

Using Eqs. (

2), (

14) and (

15) and making the corresponding substitution into Eq. (

1), the following relation for the surface impedance derivative in the case of an out-of-plane magnetic field is obtained

where

,

,

and

.

A similar procedure is also applied to obtain the formula for the surface impedance derivative in case of an in-plane magnetic field rotation at angle

,

. The difference is that, in this case the corresponding matrix elements

, do not depended on the momentum projection on the magnetic field

(since

). The corresponding formula is simpler for numerical calculations, it is similar to the one obtained for a non-tilted in-plane magnetic field[

11] and reads as