1. Introduction

The propagation of modern human society based on electronic industry has demanded stronger and cheaper energy storage systems. Among these, lithium ion batteries (LIBs) have been aggressively studied and developed because of their high endurance against electrochemistry variation and stable usage for application in various type of electronic devices including smart phone, mobile phone and EVs etc... Even though LIBs still suffer from limited capacity, high price, and safety issues including their flammable nature. Due to these reasons, it would be difficult for LIBs to fulfill the demand for upcoming new industrial applications, such as drones, EVs, military power supplies, and stationary electrical power station because they always demand higher capacity, safer and economically friendly rechargeable batteries

1-3. In this regard, lithium sulfur batteries (LSBs) could be one of alternative candidate rechargeable battery due to their high theoretical specific capacity and energy density (1,675 mAh g

-1 and 2,600 Wh Kg

-1, respectively). The corresponding values for LIBs are 240 - 280 mAh g

-1 and 350 - 400 Wh Kg

-1, respectively. Apart from the nature from LIBs, the electrochemical reaction of LSBs is different from that of LIBs due to sulfur cathode existence and can be expressed as

As a result, LSBs can offer 5 - 7 times higher energy density than that of LIBs. Combined with its other advantages, i.e., sulfur being naturally abundant, cheap, and a non-toxic element, LSBs can be considered as one of the candidate for next generation rechargeable batteries

4-7. The typical configuration of an LSB is shown in

Figure 1.

Lithium metal as being an anode and a carbon - sulfur composite is the cathode8. As ordinary battery, the separator and an electrolyte exist between the cathode and anode.

When LSB is discharged, sulfur is reduced to Li

2S by a series of electrochemical reaction while forming various types of polysulfide intermediates.

Figure 2 indicates a ordinary profile LSBs during charge – discharge electrochemical reaction

9.

During the electrochemical reaction, sulfur is reduced to Li2Sx (x = 2 - 8) by stepwise electrochemical reaction to form each lithium sulfide compounds. The lithium polysulfide (LiPS) compound with a relatively long-chain; Li2Sx (x = 4 - 8) can be highly soluble. On the other hand, the solubility of Li2Sx (x = 2 - 4) with short-chain are less soluble compared to long chained one in the electrolyte10. The lithiation of sulfur occurs stepwise. At voltage around ~2.3 V, S8 as the solid state is reduced to soluble S82- by an initial electrochemical reaction. After that, dissolved S82- is further electrochemically reduced to S42- on the cathode. During this sequential chemical process, LiPS intermediates such as S62-, S32-, and S3 are formed11,12.

As LiPS concentration increase as this electrochemical reaction proceeds, the viscosity of the electrolyte would be enhanced. Gradual voltage decrease can be seen at this stage reaction. After these events, one can observe prolonged voltage around 2.0 – 2.2 V which is the major origin of LSB capacity. During this stage, electrochemical reaction which transforms soluble low ordered LiPS to insoluble Li2S2 or Li2S, is proceeding.

At the final stage, Li2S2 would become Li2S by reduction process. However, it should be noted that since this is the solid-solid phase reaction, this kinetics are slow due to sluggish ion diffusion. Insulate characteristics of both Li2S2 and Li2S are additional cause for slow electrochemical reductive reaction13.

In spite of these advantages, LSBs still face with obstacles for practical industrial usage. For example, sulfur as cathode active material have insulation characteristic for both electron and ion. LiPS as byproducts are formed in the liquid electrolyte (shuttle effect) during discharge process which reduce the mass and utilization of cathode sulfur. In addition, dendrite formation of lithium anode may cause fire once they reach other side of electrode by a state of battery short circuit. Furthermore, volume expansion caused by the electrochemical reaction of S to Li2S would result in loosing stability in cathode structure14,15.

Tremendous amount of effort has been carried out to overcome these problematic issues by increasing the cathode materials conductivity as well as by reducing LiPS dissolution in the electrolyte16-19. For example, conductivity increase of cathode structure is trying to be achieved by applying conductive carbon, carbon nanotube, graphene, as well as conductive polymer. To prevent LiPS dissolution in the electrolyte, various kinds of oxide, sulfide, nitride and carbide and some functional materials such as quantum dot, metal organic framework have been replaced with carbon to reduce the shuttle effect20-23.

Further challenges facing the cathode and electrolyte development for LSBs have been recently accelerated due to the strong influence upon the electrochemical properties. The key function of an LSB electrolyte is to efficiently transport Li+ ions in the battery, and this requires a high level of Li+ conductivity. The composition of electrolyte also largely influence the cathode electrode reaction as well as LiPS byproducts behavior. 24-26.

In addition to designing cathodes and electrolytes, separator is also a critical LSB component to effect its performance especially in terms of suppressing LiPS problem as separators can be reservoirs or capturing materials for polysulfide intermediates. Additionally, when separator have conductivity for example, they can behave as the second current collector for electrons which would result in enhancing the LSB electrochemical performance 27. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned here that additional separator weight by its modification should be carefully regulated for battery energy density as a whole 28.

In general, polypropylene: PP and polyethylene: PE are used as separators. Although it would be difficult for theses nonpolar and hydrophobic materials to suppress LiPS shuttle effect because lithium polysulfide has more polar nature29. As preparation procedure, direct coating, slurry coating, or filtration of functional materials onto commercial separator would be enough to make such separators in order to prevent LiPS shuttle effect. Besides LiPS suppression, such functional separators are also expected to possess catalytic activity and good mechanical strength for LSBs30.

Fortunately, this kind of process such as direct coating of functional materials ink or slurry onto separator, can be applied to industrial manufacturing process easily. Especially, important parameters including thickness, weight, size and the kind of functional materials on separator can be readily controlled and can be applied to real practical industrial process. Since commercial separators possess hydrophobic nature in general as explained above, it is more ideal to use hydrophilic materials to capture LiPS and prevent shuttle effect. Thickness, weight as well as porosity of functional layers on separator also needs to be take into consideration because they directly influence the rate of electron and lithium ion as well as liquid electrolyte uptake31.

One has to also consider the modified separators whether they are either facing anode or cathode sides. This is because the separator role will influence largely depending upon whether they are placed toward the anode or the cathode direction. Although the main issue with LSBs is the shuttle effect induced by LiPS, lithium dendrites growth during electrochemical process is another problematic issue. Lithium metal dendrites are formed by side chemical process between polysulfide and lithium metal. Thus, functional interlayers on anode side could be one of possible solution to prevent dendrite growth by placing internal layer at extra space on anode side. This kind of interlayer may act as second barrier layer against leaked LiPS from cathode side, as well as preventing dendrite physical puncture to the separator. In addition, functional interlayer or separator could decrease the interfacial resistance of metallic lithium anode by introducing lithium compatible material. Anode facing functional separator may also act as the scaffold for lithium ion in order to suppress the lithium dendrite growth32.

Compared with cathode-facing separators, anode-facing separators should have a somewhat lithiophilic nature, endowing them with a high compatibility with lithium metal, in addition to their ability to functionally suppress the shuttle effect. This will control the spatial distribution of lithium deposition during redox reactions. When these properties are optimized, they can be expected to more efficiently hinder dendritic growth of the lithium metal33.

In the following content, whether functional layers or separators are facing anode or cathode side, and material classifications of separators, their working mechanisms, resulting corresponding assembled LSB electrochemical properties, will be explained.

2. Separators Classified by Materials

2.1. Separator Material: Metal

Nanoparticle- or nanolayer-based materials can inhibit dendritic Li growth by controlling lithium nucleation34. The nanoparticles in anode-facing separators behave as nucleation sites for lithium metal during electrochemical reactions as they decrease the Gibbs free energy of lithium metal electrodeposition. Initially, lithium crystal seeds would gradually grow until they cover the entire surface of the separator surface. As process proceeds, dense lithium metal layer without dendrites are formed on the separator. Liu et al. has demonstrated this phenomenon by applying lithiophilic Mg nanoparticles to an anode, LSB prepared with this unique functional separator, exhibited high capacity retention (>80% after 400 cycles)35. Furthermore, nanoparticles morphology can confer the cathode structure with appropriate pores and voids which could be favorable lithium ion transportation channel to enhance LSB electrochemical performance. It should be noted here that Mg, Ag, and Au are also known to lower the Gibbs free energy of lithium electrodeposition.

Zuo et al. investigated the Li metal deposition phenomenon with a symmetric cell at a current density of 2.5 mA cm

-2. As a result, lithium dendrites were observed on the surface of the pristine Li metal anode after electrochemical discharge process as confirmed on

Figure 3a. When Ag was co-deposited, Li dendrites had tendency to fill the interspace among the Ag particles which resulting in the lateral growth (

Figure 3b). When one take a look at cross-sectional SEM image, without Ag introduction, clear Li dendrites with a thickness of ∼66.3 µm were seen after 50 cycles of electrochemical charge-discharge process (

Figure 3c). When Ag was introduced to Li metal, in contrast, the electrode surface with dense Ag-Li alloy layer without any Li dendrites were observed (

Figure 3d). This surprising Li dendrites suppression effect of Ag introduction to Li metal anode was suggested to be due to the strong affinity of Li with Ag metal. We would like to look at one example of LIB apart from LSB. With this interesting mechanism, Li ions were deposited uniformly during electrochemical charge-discharge process. As a result, when LiFePO

4|Li full cell was prepared with Ag introduced Li metal as anode, it exhibited a high cycling performance with a high specific capacity of 131 mAh g

-1 after 300 cycles at 0.5 C

36.

2.2. Separator Material: Ceramic

Boron nitride was applied to optimize the commercial separators owing to its intrinsic high levels of insulation and high thermal conductivity

37. Boron nitride (BN) / carbon modified composite separator was prepared with coating method on separator.

Figure 4a shows a schematic figure and the functions of the BN/carbon separator in an LSB. During discharge, LiPS are spreads out from the sulfur cathode towards the lithium anode metal. The carbon layer physically hinders the diffusion of the LiPS acting as the first blocking layer, and any LiPS that diffuses through the carbon layer is subsequently trapped by the BN layer acting as the second blocking layer. This BN/carbon separator was prepared by direct ink casting (ink composed of carbon nanopowder and BN nanopowder) onto a polypropylene separator via the slurry coating method. Owing to this simple procedure, large-scale separator fabrication (dimensions 150 mm long and 60 mm wide) could be achieved (

Figure 4b). The prepared separator had sufficient mechanical strength and was able to resist physical twisting due to the strong level of adhesion between the separator, carbon, and BN nanopowders, having been bonded using a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) binder (

Figure 4c).

Figure 4d shows the surface of a pristine commercial polypropylene separator, on which some distributed pores can be observed. After coating the separator with BN (particle size ~ 100 nm;

Figure 4e) and carbon (particle size ~ 50 nm;

Figure 4f) nanopowders, the pores were fully covered. The thicknesses of the BN layer and the carbon layer were ~7 and ~6 μm, respectively (

Figure 4g). Some of the electrochemical properties of the prepared LSBs were measured. After the surface modification, lithium dendrite formation was suppressed by forming Li surface by ideal Li plating/striping process (

Figure 4h). Fortunately, LiPS diffusion was mitigated by additional BN layer on separator thus results in obtaining higher LSB electrochemical performance (

Figure 4i)

37.

In addition to controlling the lithium metal growth and nucleation, oxide functional interlayer also could be ideal in suppressing LiPS effect. Silica (SiO2) is one such material effective for preventing the LiPS shuttle effect and improving LSB performance. One of its advantages is its abundance. Thermal stability of SiO2 is also a good feature in order to confer the separator with high thermal stability38. However, its direct contact with the cathode should be prevented as SiO2 is known to react with lithium metal39. However, it should be noted one of SiO2 coated separator example will be presented in a later section. In addition, SiO2 has high affinity with LiPS, making it suitable for suppressing the LiPS shuttle effect40. Therefore, SiO2 utilization as functional LBS separators could be one of good method. Li et al. attempted SiO2 coating of a polypropylene (PP) separator using the tetraethoxysilane (TEOS)-based sol-gel method. They have elucidated that by applying PP–SiO2 separator, electrolyte wettability and thermal stability was properly improved. As a result, rate and cyclic voltammetry performance was improved owing to suppressed LiPS shuttle effect as well as promoting lithium ion transport inside LSBs41.

Chemical stability and LiPS adsorption ability of Alumina (Al2O3) is relatively high. Hou et al. elucidated that the oxygen atom with a lone electron pair of oxide materials such as Al2O3 and SiO2, has strong dipole - dipole interactions with LiPS42. Wang et al. prepared a purely inorganic separator with Al2O3 nanowires. In general, a purely inorganic separator without any base organic polymer would have a brittleness problem compared to conventional organic PP separators. Although, the advantages of ceramic separator are higher uptake of liquid electrolyte and higher porosity. They often also exhibit improved thermal stability and enhanced conductivity compared to organic one. This mechanism can be applied for not only LSB but also LIB. For example, when alumina separator was applied for Li|LiFePO4 (LFP), the battery electrochemical characteristics were better than conventional PP separator based battery43.

Regarding LSB, He et al. prepared an Al2O3 thin film on a commercial separator on anode-facing side in order to examine the lithium dendrite formation prevention effect. It was found that the Al2O3 layer successfully mitigated the chemical reactions between LiPS and the lithium anode. They also discovered that prepared Al2O3 porous structure accelerate uniform lithium nucleation which resulted in preventing lithium dendrite growth to form smooth and dense lithium anode44.

Li6.4La3Zr1.4Ta0.6O12 (LLZTO) is the lithium ion conductive solid electrolyte and it was coated on PP separator on anode side. Smooth lithium deposition was achieved due to uniformly dispersed transportation path for lithium ion in the three dimensional structure in LLZTO. It was also clarified that lithium ion deposition was further enhanced by adding higher content of LLZTO by localizing higher content of anions. Owing to these improvements, prepared LSB presented improved electrochemical performance with better safety due to solid electrolyte stability45.

2.4. Other Functional Separator Materials

As we have seen above, a modified anode-facing separator could act as a simple barrier to push back LiPS immigration from the cathode to the anode, and this would also be expected to impede Li dendrite formation. For example, there is a kind of conducting polymer that is known to capture LiPS, promoting Li ion flux and electron transportation. Li et al. prepared a conductive polypyrrole (PPy) film for a commercial anode-facing separator and succeeded in improving LSB electrochemical properties

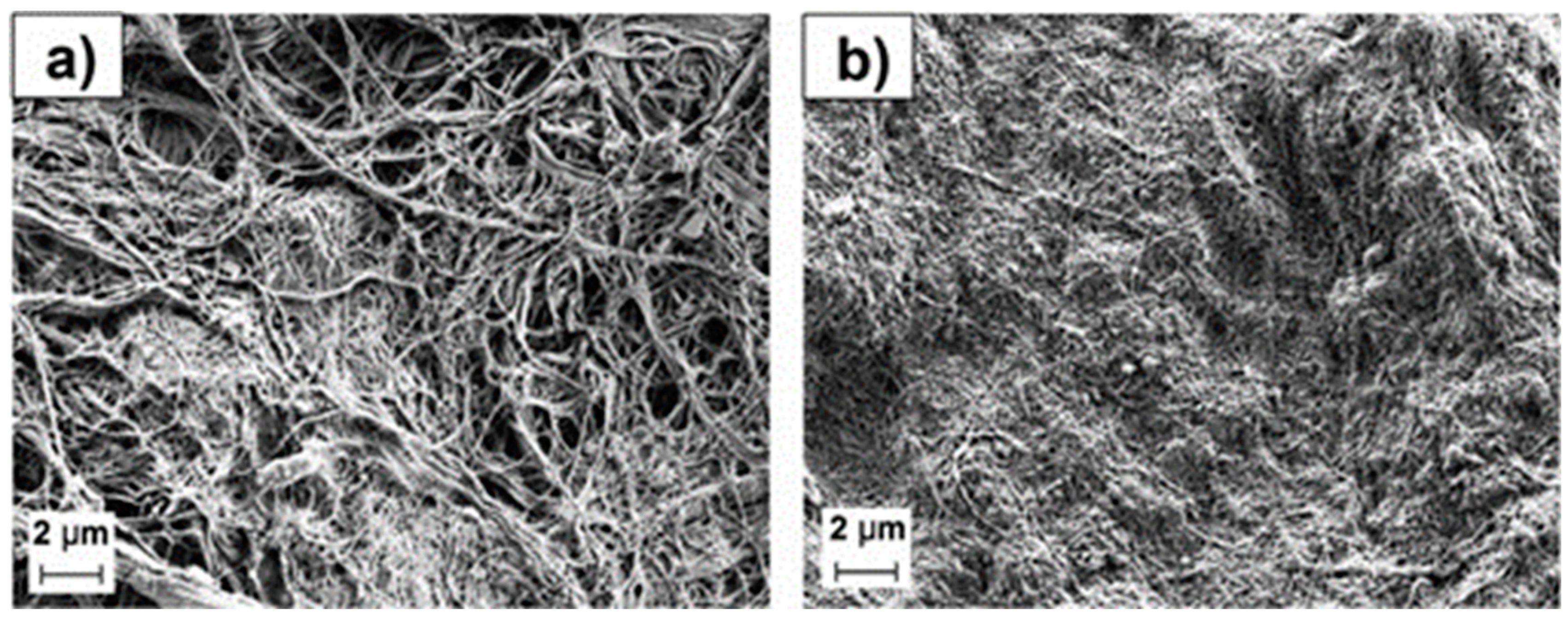

46. They deposited the PPy film on the separator by applying an Fe-based precursor and pyrrole monomer and succeeded in obtaining PPy-modified separator (

Figure 5a,b). Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) observation of the pristine separator revealed abundant nanopores with sizes of 100–200 nm (

Figure 5c). In contrast, slightly smaller nanopores with sizes of 30–50 nm were observed on the PPy-coated separator (

Figure 5d). The thickness and weight of the coated PPy layer were as small as 15–25 nm and ~0.13 mg cm

-2, respectively, which is advantageous for industrial use in terms of energy density per weight (

Figure 5e). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out upon both separators. A new N 1s peak at 399.8 eV appeared after PPy coating (

Figure 5f). The N 1s spectrum (

Figure 4g) suggests the presence of three typical nitrogen species, N

+ (401.7 eV) motifs, –N– (400.7 eV), and –N= (399.6 eV), arising from PPy

47, 48. These nitrogen heteroatoms provide strong chemical adsorption sites for polysulfides and thus prevents their transportation between electrodes

49, 50. The hydrophobic surface of the separator became hydrophilic after PPy modification due to the innate hydrophilicity of PPy. PPy also chemically adsorbed LiPS owing to its special structure and functional group. As a result, Li dendrites formation was suppressed by the enhancement of the homogenous Li ionic flux and Li plating/stripping.

Preparing a physical barrier by introducing some kinds of lithium compound to a separator is an alternative way to reduce the unfavorable reactions between LiPS and lithium metal. This concept is different from using a material that would not react with any LSB component. Based on this concept, the lithium compound, LiF, was applied to a separator. Lewis acid lithium atoms in LiF could relate with 1,2- dimethoxyethane (DME) as Lewis alkali to form DME-LiF clusters. This clusters are viscous sol and form dense layer that would behave as a shield to prevent LiPS shuttle effect. Li et al utilized this method to improve the electrochemical properties of LSBs51.

Cathode facing functional separators also could be effective as anode facing counterparts because they can serve as the first barrier to LiPS, potentially increasing the chance of sulfur utilization as an active material. To date, polymers, metal compounds, ceramics, carbonaceous material, and their composites have been used to alter commercial separators in order to endow them with additional positive properties

52. Separators should be mechanically strong, chemically and electrochemically stable, and light weight in order to avoid negatively impacting the energy density of the final LSB product. In addition, they should possess high ionic conductivity and the ability to suppress the LiPS shuttle effect. The functions of a cathode-facing separator can be generally classified as physical adsorption, chemical adsorption, catalytic conversion, and duel mechanism functions as shown in

Figure 6 31.

2.5. Separator Material: Carbonaceous Materials

Commercial separators are composed primarily of PP and PE and are considered to be purely physical barriers. In light of this, great number of studies have been performed to investigate the effect of applying carbonaceous material to the cathode side of the separator owing to its high electrical conductivity. These carbonaceous materials, including conductive carbon black, carbon nanotube, and graphene, are being studied with an aim to enhance LiPS suppression, cycle stability and capacity of LSBs53,54. The improved electrochemical characteristics of LSB are mainly the result of high electrical conductivity which can confer them to act as a second current collectors to reduce resistance of the battery55. In addition, a sulfur cathode-facing carbon loaded separator would act as a barrier to suppress LiPS shuttle effect.

For example, eight separators coated with conducted carbon of various nano-porosities were investigated by Huang et al. to see how the material characteristics contributed to LSB separator performance56. The LSB with the nonporous carbon loaded separator demonstrated the optimized peak capacity of 1,112 mA·h g-1 at a cycling rate of C/10 and retained a good reversible capacity of 710 mA·h g-1 even after 200 cycles under lean-electrolyte conditions56.

Kim et al. prepared a useful separator modified with carbon nanotubes conjugated with hydroxyl groups. The experimental results and theoretical calculation confirmed that the hydroxyl groups on the surface of carbon nanotube promoted good LiPS capturing effect on the cathode side. Furthermore, the LiPS migration decrease to an anode side conferred the lithium electrode with good stability. In addition, the high conductivity of carbon nanotube with hydroxyl group assisted re-use of adsorbed intermediates for further electrochemical reaction (

Figure 7). Owing to these advantages, the prepared LSB exhibited initial discharge capacity of 1,056 mAh g

-1 with a capacity fading rate of 0.11% per cycle over 400 cycles at a 0.5 C rate

57.

Besides conductive carbon and carbon nanotubes, graphene can be also considered as an attractive functional coated material to improve the separator properties. In general, graphene possess high electrical conductivity, super lightweight, have high chemical stability and ductility and it is mechanically strong. The separator coated with graphene blocks pores in the polyolefin separator which can prevent LiPS dissipation. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) was obtained using Hammer’s method, and it was dispersed in DMF (dimethylformamide) and combined with sodium ligno-sulfonate (SL) and hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) at 140 °C for 4 h under nitrogen flow. SL has abundant hydroxyl, carboxyl, and dendritic groups and they are industrially cheap and available materials. A linear chain compound, HDI, was employed to link rGO and SL via the isocyanates in the HDI to the hydroxyl groups in rGO and SL. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was applied to observe the crosslink reaction between rGO, HDI, and SL. Prior to synthesis, the obvious broad peak at 3,400 cm

-1 is attributed to hydroxyl stretching vibrations, and the weak peaks at 1,634 cm

-1, 1,402 cm

-1, and 1,112 cm

-1 observed for the pristine GO sample and pure SL were referred to carbonyl C=C, –OH, and C–O bonds in GO and SL, respectively

58-60. After reaction with HDI and SL at a high temperature, the –OH bond peak largely disappeared from the spectrum of the GO/SL composite, confirming that GO was reduced to rGO (

Figure 8B). The characteristic C–N and N–O bond peaks were also observed at 1,632 cm

-1, 1,287 cm

-1, and 1,561 cm

-1, indicating that a crosslink reaction occurred between rGO and SL through the HDI hydroxyl group. It was also confirmed that zeta-potential measurements of the rGO/SL composite showed a potential of 75.14 mV, which could produce a strong electrostatic repulsion force to the negatively charged polysulfide ions, significantly reducing the LSB shuttling effect

61,62.

This type of prepared rGO/SL composite solution was applied to a commercial PP separator using a facile vacuum filtration process. Sulfonic groups in the lignin can confer separator with enough negative charge and reduce negatively charged LiPS diffusion. Applying this reduced graphene oxide/sodium ligno-sulfonate/separator achieved a capacity retention of 74% over 1,000 cycles63.

In addition to just physically blocking LiPS, chemical bonding between polar substances is an alternative procedure to suppress LiPS diffusion. To capture polar polysulfide, polar materials are superior to hydrophobic carbon materials. Carbonaceous materials doped with various kinds of elements (e.g., N, B, S, P, F, O, Cl, Co, Ni, Fe) tend to possess polarity and have greater ability to capture LiPS

64. A CoS

2 and NiS

2-modified nitrogen doped reduced graphene oxide composite material was prepared by hydrothermal method

65.

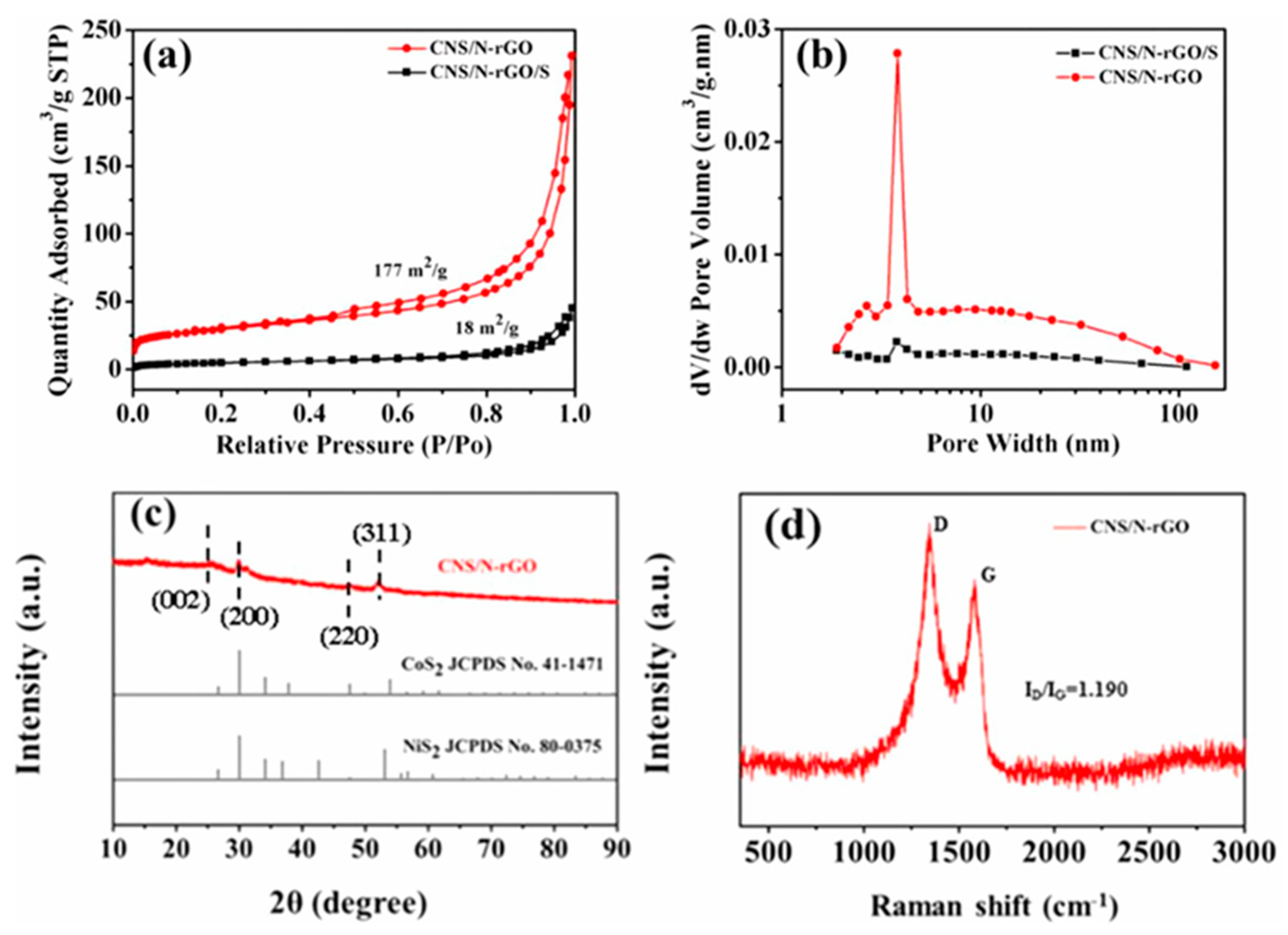

Figure 9a shows the N

2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and the pore size distribution of the pristine cobalt nickel sulfur/nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide (CNS/N-rGO) composite and the composite mixed with elemental sulfur, respectively. It is clear that the CNS/N-rGO isotherm has a typical hysteresis loop. The calculated Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area of CNS/N-rGO was 177 m

2/g, and the cumulative pore volume was 0.416 cm

3/g. The pore-size distribution obtained by analyzing the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) desorption isotherm is shown in

Figure 9b. It is confirmed that a strong peak is located at ~4 nm for the CNS/N-rGO composite, indicating the porous structure of the sample. The porous structure can promote lithium ion transportion and help adsorb the LiPS, thus improving the LSB electrochemical performance

66,67. After mixing with the elemental sulfur, the surface area and pore volume was reduced to 18 m

2 g

-1 and 0.09 cm

3 g

-1, respectively, and the peak of the BJH pore-size distribution curve at a pore width of 4 nm was largely reduced. These results suggest that the sulfur was immersed in the CNS/N-rGO. The X Ray Diffraction (XRD) pattern of the CNS/N-rGO composite is shown in

Figure 9c. A broad peak at 26° is attributed to the (002) facet of the graphite. The characteristic peaks at 32.01°, 49.03°, and 53.04° correspond to the (200), (220), and (311) CoS

2 facets, respectively

68. As seen in

Figure 9d, the Raman spectrum with a characteristic peak at 1350 cm

-1 (D band) and a peak at 1580 cm

-1 (G band) originated from the structural defect and the stretching mode of the C–C bond of graphene, respectively. The ID/IG (Intensities of D and G band) ratio of CNS/N-rGO is ~1.190, arising from the multilayer structure of the rGO

69. Wu et al. coated this type of composite material onto the surface of a separator and used it in an LSB

68. Owing to its morphological advantages and LiPS affinity, the LSB exhibited 1st discharge capacity of 1,524 mAh g

-1 and 610 mAh g

-1 at 0.1 C and 8 C, respectively. It exhibited good long-term stability, with capacity as high as 700 mAh g

-1 even after 350 cycles under 1 C. It was deduced that the N-dopants and decorated and doped cobalt, nickel, and sulfur nanoparticles in the composite could provide a favorable electrochemical structure and active sites for capturing soluble LiPS and promote LiPS conversion in redox reactions, thus preventing the shuttle effect

68.

Díez et al. applied sulfur and nitrogen co-doped carbon nanoparticles as the separator material for LSBs. They were coated onto the separator surface to make a thin packed layer to suppress LiPS diffusion. It was found that the nitrogen, sulfur co-doped carbon nanoparticles improved both capacity and cycle characteristics. The capacity was 841 mAh g-1 at 0.2C even after 100 cycles with a 99.3% of coulombic efficiency70.

Song et al. used a lightweight, functional layer composed of porous iron and nitrogen co-doped carbon nanofiber materials, to modify a PP separator for LSB. Fe-N co-doped carbon provide high conductivity and LiPS adsorption capability to the separator which was effective in preventing LiPS diffusion while keeping good lithium ion transportation. Prepared separator behaved as the conductive current collector to reuse the active sulfur based compounds as well. The LSBs with this Fe-N co-doped carbon modified separator demonstrated high electrochemical performance, with a capacity of 847.9 mAh g-1 at 2 C and a low degradation rate of 0.053% per cycle over 500 cycles at 0.5 C71.

2.6. Separator Material: Metal Oxide

Metal oxides have been studied for application as LSB separators as they can generate different bonds for LiPS. Metals lose their electrons in certain conditions and become metal ions, which can generate chemical bonds to capture LiPS to prevent shuttle effect. In addition, the metal oxides in nanostructure states, would be easier to combine with polymers to become functional separator. It has been shown that LiPS diffusion can be suppressed with Al2O3 coated layer on separator cathode side as a physical block layer for LiPS. The 1 st discharge capacity of LSB prepared with an Al2O3-coated separator was 967 mAh g-1 at the rate of 0.2 C and deteriorated to 593.4 mAh g-1 after 50 cycles. The electrode charge transfer resistance was reduced due to porous structure of Al2O3 coated layer, which acted as an ion-conducting scaffold for capturing dissolved sulfur-containing active materials72.

Han et al. created a PP separator with TiO2/carbon coated layer and applied for LiPS capturing barrier for LSB73. The highly conductive carbon with its porous structure endowed separator to adsorb LiPS while acting as second electrical current collector. On the other hand, TiO2 on the porous carbon surface chemically captured LiPS. Owing to these properties of the TiO2/porous carbon composite coating layer, an initial discharge capacity of 926 mAh g-1 at 0.1 C was observed, maintaining 75% capacity even after 150 cycles73.

Gao et al. also prepared a functional separator composed of a TiO2/surface-modified carbon nanotube composite coated onto a PP separator. The LSB assembled with this type of separator having strongly polar TiO2 and highly conductive carbon nanotubes demonstrated enhanced battery performance. The capacity was1,104 mAh g-1 initially and was still as high as 848 mAh g-1 even after 200 cycles at 0.5 C, demonstrating a capacity decay of only 0.066% per cycle over 900 cycles74.

A SiO2 nanoparticle-modified PP separator was made by Li et al. by dipping PP separator in a sol gel TEOS solution and Tween-8075. This kind of separator have high good electrolyte wettability, high thermal stability and the resulting LSB showed considerable improvement in its cyclic stability and rate capability. The capacity decay of the LSB prepared with this SiO2–PP separator was 64% after 200 cycles at 0.2 C, which was superior than the one made with PP separator (45%). In addition, the rate capacity of LSB with SiO2–PP separator achieved 956.3, 691.5, 621, and 567.6 mAh g-1 at a current density of 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 C, respectively.75.

Increasing the ratio of sulfur utilization would increase LSB capacity. Thus, it is necessary to not only capture LiPS but also to reactivate sulfur76. Certain types of separators with adsorption abilities cannot satisfy this requirement. Therefore, it is necessary to look for the material which can play a role for LiPS re-utilization. In addition, the material with catalytic ability is also important.

During LSB charging process, fast reaction kinetics is achieved only when the energy which is higher than activation energy of solid Li2S2/Li2S conversion to polysulfide, is applied77. Fast battery reaction rate can be accelerated when activation energy is lowered so that one needs good catalyst to lower the activation energy. This concept differs from the LiPS adsorption materials which we have been described above. This kind of catalytic material can accelerate oxidation reduction rate so that reaction of polysulfides conversion reaction to Li2S2/Li2S can be enhanced. This is also a highly efficient way to prevent LiPS shuttle problem besides using LiPS adsorption materials. Electrons on the catalytic material can transport to S – S bond of LiPS to become Li2S2/Li2S. In addition, catalyst can reduce the overpotential of sulfur species, which would enhance the sulfur electrochemical reactions 78. Therefore, finding appropriate catalytic material that can accelerate LiPS conversion into Li2S2/Li2S, is highly recommended.

In this regard, La2O3 with hollow spherical structure was prepared by spray dryer method and coated onto a commercial PP separator in order to adsorb LiPS and accelerate redox reactions at the same time79. Charge/discharge measurements demonstrated that the resulting LSB showed an 966 mA hg−1 capacity on 1st cycle at 1 C and capacity became 720 mA hg−1 after 200 cycles. It was suggested that the enhanced electrochemical properties were due to LiPS capturing effect of La2O3 as well as being chemical catalyst to promote the electrochemical reaction by lowering the activation energy79.

2.7. Separator Material: Metal Sulfide

Some metal sulfides are known to adsorb LiPS owing to their polar nature and thus have been studied for use as a separator material. Tan et al. prepared a reduced graphene oxide/MoS2 (rGO/MoS2) layer on cathode side of commercial separator. The rGO behave as physical barrier for LiPS diffusion and an extra current collector, while MoS2 can capture LiPS. The prepared LSB demonstrated a high reversible capacity of 1,122 mAh g-1 at 0.2 C, a low capacity fading rate of 0.116% for 500 cycles at 1 C, and excellent rate performance of 615 mAh g-1 at 2 C80.

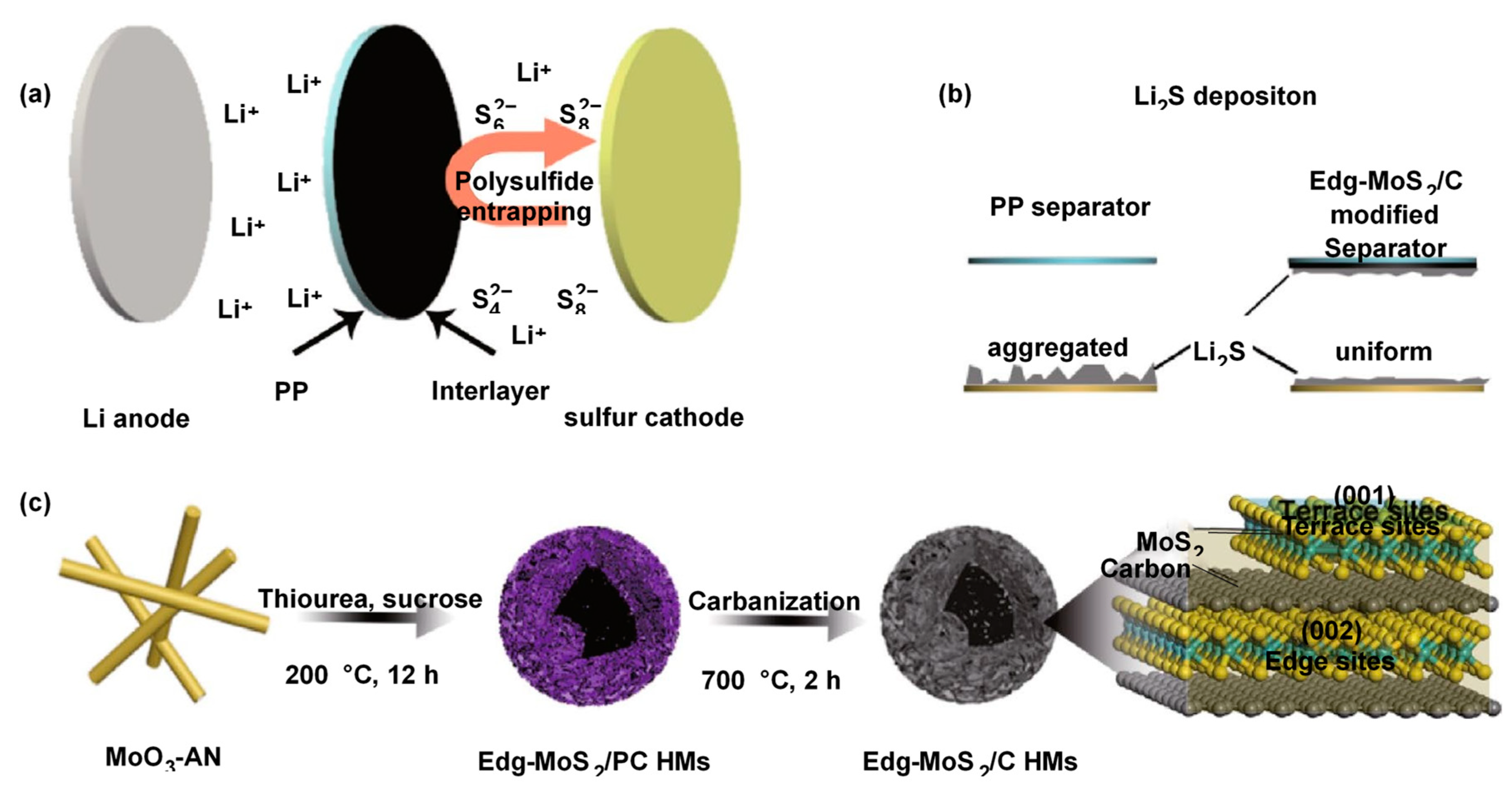

Another study demonstrated the potential use of edge-rich MoS

2/C hollow microspheres as LSB separators. The MoS

2/C hollow microspheres were prepared by hydrothermal synthesis with MoO

3, aniline, thiourea and sucrose and subsequent carbonization process

81. Carbonization was carried out in order to enhance graphitization degree of the carbon in MoS

2/C hollow microspheres (

Figure 10). The prepared MoS

2/C hollow microspheres carry a high chemical absorption property and a high density of LiPS capturing sites, resulting in showing excellent LiPS diffusion prevention. In addition, phase conversion reversibility of active sulfur species could be regulated in a stable matter with this MoS

2/C composite material particularly at high C-rates and sulfur loading. Thus, LSB arranged with MoS

2/C separator exhibited a discharge capacity of 935 mAh g

-1 at initial cycle at 1.0 C and it was 494 mAh

-1 even after 1000 cycles with a sulfur loading of 1.7 mg cm

-2.

82

Functional separators using two-dimensional exfoliation nanosheets could efficiently contain LiPS for long-life LSBs. Mao et al. fabricated new two-dimensional ZnS exfoliation nanosheets using the microwave-assist exfoliation method, and then combined it with graphene to modify a commercial separator. The nanosheet dispersion was mixed with graphene and filtered on the separator to form ZnS exfoliation nanosheets/graphite/Celgard separators. An LSB assembled with this type of separator exhibited an 1165.9 mA h g-1 as initial capacity and became 685.3 mA h g-1 after 100 cycles. Capacity retention was 58.8% at 0.1 C and 0.036% of capacity decay per cycle when cycled was carried out for 1000 times at 0.5 C83.

Yao et al. combined the high conductivity and absorption ability of SnS, and the strong catalytic property of ZnS, to prepare a ZnS–SnS heterojunction84. A polydopamine-derived nitrogen-doped carbon shell was coated onto this ZnS–SnS composite material and compared with its single-component counterparts (ZnS/N-doped carbon shell and a SnS/N-doped carbon shell). When coated onto the separator, the ZnS–SnS/N-doped carbon-based LSB demonstrated a high reversibility of 1,149 mAh g-1 capacity for 300 cycles at 0.2 C, and a high rate performance of 661 mAh g-1 at 10 C, and capacity decay rate was 0.0126% each cycle after 2000 cycles at 4 C84.

In addition, it was reported that a WS2/prussian blue (PB)–PPy composite material-modified separator could inhibit the back and forth of LiPS movement and the formation of inactive sulfur-related substances. Lithium ions, however, could still be transferred homogeneously inside the battery. When compared with LSB with ordinary commercial PP separators, the capacity and cycle properties of this modified LSB were remarkably ameliorated and showed high capacity (1,050 mAh g-1) and improved capacity retention (650 mAh g-1 after 300 cycles) with a coulombic efficiency greater than 99.5% and a capacity retention rate that reached 62%. This study also showed that a three porous layer as ions sieve structure indeed prevents the transfer of LiPS through the electrolyte to the anode while allowing lithium ions to pass through the separator85.

2.8. Separator Material: Metal Carbide

Among various kinds of metal carbides, titanium carbide (TiC) is regarded as a representative non-oxide ceramic material owing to its high electrical and thermal conductivity, high melting point (about 3,200°C), strong hardness, high Young’s modulus, low density (4.93 g/ml), and high chemical stability 86. In a recent topic, TiC is considered for application in energy storage purpose due to these excellent characteristics. Especially for LSBs, TiC can be applied to improve the cycling performance by its high polar bond interactions with sulfur species and its ability to reduce LiPS shuttle effect87. In addition, high electrical conductivity of TiC is the additional good reason to be an ideal sulfur scaffold material.

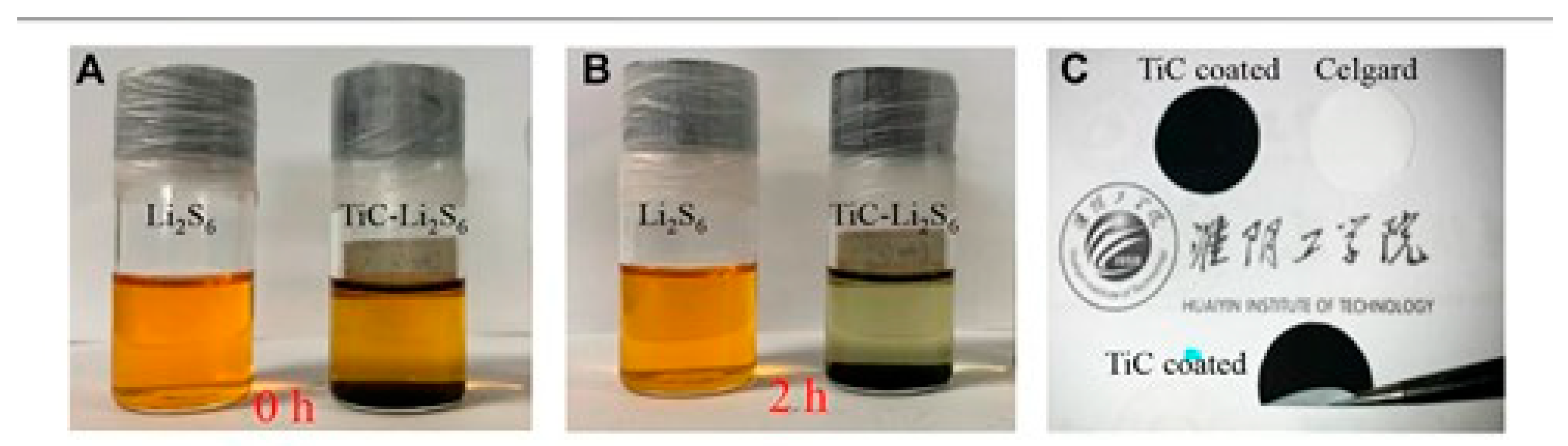

Liu et al. synthesized TiC nanoparticles from waste polytetrafluoroethylene as a carbon source at 500°C, that is lower than general TiC synthesis temperature. They used this TiC as a coating material for an LSB separator and successfully mitigated the shuttling problem. The visual influence was investigated by dispersing prepared TiC nanoparticles in a five mmol L

-1 LiPS solution. As presented in

Figure 11A,B, the color of the bottle named with TiC–Li

2S

6 changed from dark yellow to become almost transparent after two hours of adsorption, whereas the bottle without TiC remained unchanged. These results clearly imply that waste polytetrafluoroethylene derived TiC nanoparticles have high potential in reducing LiPS shuttle effect in LSBs

88. The visual images of the separators coated with prepared TiC nanoparticles and intact separator are shown in

Figure 11c. The bending test also assured a strong TiC adhesion to the separator. One can easily visualize that the dissolved LiPS shuttle effect could be suppressed with this separator. The resulting LSB delivered a high capacity of 1,242 mAh g

-1 at initial cycle and the capacity remained at 736 mAh g

-1 even after 100 cycles at 0.2 C, which are superior results compared to an LSB with a commercial separator (respectively 827 and 373 mAh g

-1). They also proved that the improved electrochemical properties and high electronic conductivity of the TiC nanoparticles resulted in low capacity decay during rate performance

89. Zhao et al. also fabricated a novel TiC-modified PP separator and applied as LBS separator. Compared to the pristine PP separator, the TiC-modified PP separator exhibited superior wettability and adsorption ability for LiPS. As a result, LSB with TiC-modified PP separator displayed higher specific capacity and more stable cycling performance

90.

An LSB assembled with a separator that contained mesoporous tungsten carbide (meso-WC) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) was arranged by Moon et al. 91 The battery exhibited good performance: ~950 mAh g-1 at 1 C after 100 cycles. It was found that even at a high sulfur loading of 3.0 mg cm-2, the LSB maintained high level performance, with a capacity of ~737 mAhg-1 and a retention of 83% after 300 cycles. It was deduced that the enhanced performance was due to the shuttle effect reduction due to high adsorption of LiPS, effective reutilization of active materials, and acceleration of the conversion reaction91.

A Co3W3C/C composite was prepared by Zhao et al. 92 using a simple pyrolysis procedure and implemented as a modification layer on the commercial separator. The arranged modified separator not only reduce the shuttle effect but also acted as a catalytic membrane by accelerating the redox reaction of sulfur species. By utilizing the coated separator, initial capacity was 1,345 mAh g-1 at 0.1 A g-1. Rate performance was also good by achieving high capacity of 670 mAh g-1 even at 7 A g-1. Cycle performance was also excellent since the decay rate was as low as 0.06% per cycle and an average coulombic efficiency of 99.3% within 500 cycles at 1 A g-1. These results indicate that this material utilize Co–W bimetallic carbide advantage in mitigating the shuttle effect and promote the redox kinetics to gain high performance LSB92.

A nanocrystalline niobium carbide was synthesized by practical scalable autoclave technology and used as the interlayer material for an LSB by Cai et al. 93 The prepared nanocrystalline niobium carbide exhibited high electrical conductivity and a strong ability to anchor LiPS species, which were highly effective in improving cycling performance and rate capabilities. The conductive niobium carbide interlayer not only acted as a shield to confine LiPS within the cathodic side, thereby keeping the lithium anode from passivation and alleviating battery self-discharging behavior, but also acted as an additional current collector to reuse the trapped active material and significantly enhance sulfur utilization. Because of these superior characteristics, the LSB assembled with this type of separator showed outstanding cycle stability with a negligible capacity fading rate of 0.037% per cycle and high areal capacity of 3.6 mAh cm-2.93

2.9. Separator Material: Nitride

Transition metal nitrides are widely adopted as a catalyst for sensing and electroanalysis applications because of their superior conductivity, reactivity, and chemical robustness94. For example, in contrast to their oxide (1.0 × 10-3 Sm-1) and sulfide (9.7 × 10-2 - 103 Sm-1) counterparts, molybdenum nitrides possess high electrical conductivity95. Chen et al. coated molybdenum nitride nanosheets, which were obtained through a salt template method, on a Celgard separator and the capacity of assembled LSB was 566 mAh g-1 after 500 cycles at 0.5 C, corresponding to 68.1% retention96.

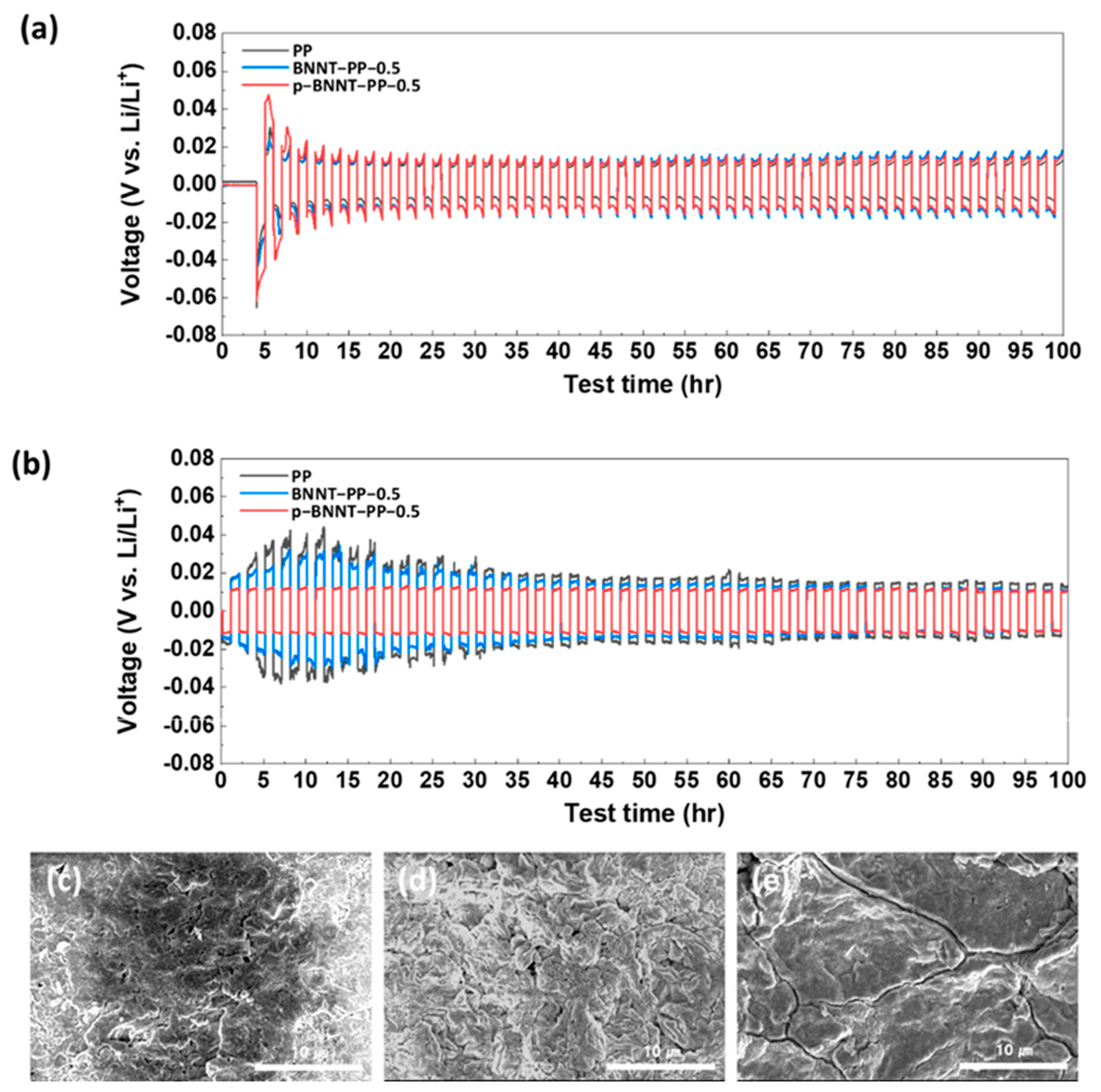

Kim et al. prepared a boron nitride nanotube (BNNT) based separator for the cathode side. The BNNTs were originally provided by a research institute but contained impurities such as amorphous boron, hexagonal boron nitride (h−BN), and amorphous boron nitride (BN) particles. Therefore, a purification process was performed to obtain purified BNNTs (p-BNNTs). This purification process was important to see the true effect of BNNTs without the addition of amorphous and hexagonal boron nitride. Lithium stripping/plating analysis was conducted to evaluate the lithium metal’s stability by measuring the overpotential that occurred during repeated stripping and plating of lithium under a constant charge/discharge current. When stripping/plating of lithium was conducted at 0.35 mA/cm

2, a similar overpotential profile was observed for LSBs composed of all separator types; however, when stripping/plating was conducted at 1 mA/cm

2, the overpotentials of the commercial PP separator and the BNNT separator were much more obvious than those of the p-BNNT (

Figure 12a,b). This occurred because of dendrite formation and detachment caused by non-uniform lithium stripping/plating. In contrast, the higher ionic conductivity of the p-BNNT separator demonstrated the good stability of the lithium anode (

Figure 12c–e). The p-BNNT also showed a homogeneous pore structure because of random stacking and the partial charge on the surface, a result of the electronegativity difference between B and N. Thus, compared to the conventional PP separator, the p-BNNT-loaded PP separator prevents dendrite formation on the Li metal anode, facilitates ion transfer through the separator, and alleviates LiPS diffusion. Owing to these characteristics, the capacity of the p-BNNT-loaded PP separators based LSB was 1,429 mAh/g and exhibited long-term stability over 200 cycles

97.

Chen et al. also prepared high-quality boron nitride nanosheets using a scalable exfoliation process and used them as a separator material98. They implemented the sonication-assisted liquid-phase exfoliation scalable process and investigated the effects of a spectrum of exfoliation factors (e.g., ultrasonic conditions and solvent and bulk material feeding) on the boron nitride nanosheet yield. A high yield of 72.5% could be achieved while maintaining the boron nitride nanosheets to a few layers and defect free. Owing to the Lewis acid sites of the boron atoms, the boron nitride nanosheets could interact with the polysulfide anions in the liquid electrolyte and facilitate uniform lithium deposition, with the end result being an LSB with a long life98.

Carbon nitride was used as an LSB separator material by Luo et al. 99 Co-doped g-C3N4 nanosheets were synthesized with calcination process. Capacity of LSB prepared with Co–g-C3N4-modified separator was 1,121 mAh g-1 at 0.2 C with a high rate performance up to 3 C. The Co–g-C3N4-modified separator installed LSB also indicated excellent stability (640 mAh g-1 after 250 cycles) with a high coulombic efficiency of over 98%. The improved performance was due to the effective restriction of LiPS diffution owing to the high adsorption and high efficiency of LiPS catalytic conversion induced by the Co–g-C3N4 nanosheet implemented separator99.

2.10. Separator Material: Phosphide

Transition metal phosphides generally have good electrical performance, adequate chemical adsorption ability, and significantly high catalytic capability for LiPS, which makes them an interesting choice as a separator modifier for LSBs100.

Chen et al. designed multi-shelled CoP nanospheres as a separator coating material for LSBs. 101 It was found that the conductive CoP could efficiently anchor LiPS because of polar nature and partial surface oxidation state (as confirmed by the XPS analysis), which induce Co sites to chemically capture LiPS with strong Co–S bonding. In addition, the specific multi-shelled structure could capture LiPS and reduce the shuttle effect. Owing to these characteristics, this LSB exhibited high cycling stability with a capacity decay of 0.078% per cycle over 500 cycles at1 C and excellent rate performance (725 mAh g-1 at 5 C)101.

Lin et al. also investigated the possibility of CoP as a separator coating material. 102 They modified a PP membrane with nano-cubic CoP/C by vacuum filtration method. CoP/C deposited separator not only efficiently adsorbed LiPS by its strong chemical affinity but also promoted the conversion of the soluble intermediates due to the fast redox transfer. Because of these positive features, the LSB arranged with CoP/C-deposited separator presented a minimum capacity decay as low as 0.08% per cycle over 500 cycles at 1 C with 938 mAh g-1 capacity as initial cycle. Rate performance was 594 mAh g-1 at 4 C102.

Another transitional metal phosphide was also studied by Zhao et al., who prepared FeP/spongy carbon composites with multiple adsorptions and catalytic sites as a modified material for an LSB separator103. The spongy carbon was shown to possess suitable structural stability and long ion/electron transmission channels. The addition of the FeP-endowed spongy carbon reacted with the LiPS to block shuttling and catalyze the conversion of sulfur. It was found that the FeP/spongy carbon-modified separator could reduce the flammability of the completed LSB. Benefiting from these features, the prepared LSB exhibited high cycling stability (526 mAh g-1 over 400 cycles at 1 C), and with a high areal sulfur loading of 4 mg cm-2, the LSB could retain a capacity of 618 mAh g-1 after 150 cycles103.

A heterostructured Ni/Ni2P-embedded mesoporous carbon nanosphere composite (Ni/Ni2P–MCN) was developed to accelerate polysulfide catalytic conversion in LSBs.

Figure 13a presents the cyclic voltammetry curves of LSBs with various separators, from which the redox reactions can be explored. Compared with the Ni–MCN/PP, MCN/PP, and pristine PP cells, the Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP LSB showed two cathodic peaks (corresponding to the sulfur transition to soluble polysulfides and soluble polysulfides to solid-state Li

2S

2/Li

2S), indicating they have the efficient polysulfide conversion kinetics

104. In the following anodic process, a typical peak of approximately 2.4 V was observed. Clearly, the Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP cell had an anodic peak with a lower potential and larger area than the Ni–MCN/PP, MCN/PP, and pristine PP cells, revealing that it experienced accelerated dissolution and oxidation reaction of Li

2S

2/Li

2S

105, 106.

A polarization potential between the anodic peak and lower potential cathodic peak was also utilized to estimate the enhanced redox kinetics of the sulfur species, whereby the Ni/Ni2P–MCN/PP LSB demonstrated the lowest polarization potential (70 mV) compared to the other LSBs (Ni–MCN/PP cell: 97 mV; MCN/PP cell: 100 mV; and pristine PP cell: 131 mV)107. Therefore, it was concluded that Ni/Ni2P–MCN/PP, having abundant heterostructure interfaces, can enhance the catalytic conversion and redox kinetics of LiPS and decrease the electrochemical polarization.

The Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP LSB also presented the highest specific capacity at each current density among all the cells (

Figure 13b). The charge–discharge curves are shown in

Figure 13c; the Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP LSB showed a weak degree of polarization, a typical discharge plateau, indicating its relatively high utilization of sulfur. As shown in

Figure 13d, the Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP LSB delivered an initial discharge capacity of 1,315 mA h g

−1 at 0.2 C and retained a capacity of 1,086 mA h g

−1 after 125 cycles. When applied current was increased to 0.5 C (

Figure 13e), a discharge capacity was still 916 mA h g

−1 and a high capacity retention was remained to keep approximately 87.9% even after 275 cycles. In contrast, the pristine PP-based LSB had the lowest initial capacity and worst capacity decay, evidencing its weak conductivity and near-zero LiPS shuttle effect reduction.

The Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP LSB indicated an enhanced discharge capacity of more than 815 mA h g

−1 (approximately 3.5 mA h cm

−2) after 120 cycles at 0.2 C (

Figure 13f). An extended cycling performance test was conducted and the Ni/Ni

2P–MCN/PP LSB presented a discharge capacity of approximately 953 mA h g

−1 at 1 C (

Figure 13g). It had an excellent discharge capacity of approximately 518 mA h g

−1 with a high coulombic efficiency (~ 99%) even after 1,500 cycles, implying that the average capacity decay could be as low as 0.031%. Thus, we can say that Ni/Ni

2P-mesoporous carbon nanosphere composite-deposited separator not only suppressed the LiPS diffusion by its abundant chemical adsorptive sites but also demonstrated high catalytic abilities for the conversion of polysulfides. In addition, the conductive carbon matrix with an exposed mesoporous structure could serve as an effective physical barrier to accommodate insoluble deposited Li

2S.

2.11. Separator Material: Metal Organic Framework-based Materials

Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) are the class of porous materials composed of metal ions and organic ligands. One of MOF application can be molecular sieves and selective gas separation on a molecular scale108-110. MOF and MOF based composite materials have been investigated as porous host materials for LSB cathodes to retain sulfur due to their large specific surface area and catalytic effect for LiPS111. A porous material with optimally regulated pore sizes can work as a sieve to separate desirable ions from an ionic solution such as LiPS, thus resulting in reducing their shuttle effect. In this regards, MOF and MOF based materials are good candidate material for LSB separator owing to their tunable pore size and specific surface area.

Songyan et al. prepared an MOF-based LSB separator to investigate its effectiveness in mitigating the LiPS shuttling issue112. The separator behaved as an ionic sieve for LSB and successfully sieved Li+ ions while mitigating LiPS migration to lithium metal anode side.

One of example is applying MOF – graphene oxide composite as separator material. The preparation procedure is exhibited in

Figure 14a. The MOF layer was grown initially. Desirable amount of graphene oxide (GO) solution which was obtained by filtration was applied onto uniformly dispersed crystalline MOF particles. It was confirmed that the MOF and GO layers were strongly adhered onto the membrane. This procedure was repeated several times to assure the quality of the preparation process. The MOF nanoparticles filled void space tightly near the grain boundaries. A self-standing separator can be obtained by peeling off this type of material from the filter. The XRD patterns proved that these MOF particles were consistent with HKUST-1 aligned along the oriented (001) directions. It was found that the structural scaffold of the MOF remained intact even after over 200 times of electrochemical cycles. (

Figure 14c). The morphological observation of the MOF/GO separator is presented in the SEM image (

Figure 14d,e). When this type of MOF based separator was implemented as a separator, the resulting LSB exhibited decay rate as low as 0.019% per cycle over 1,500 cycles. Almost no capacity fade was observed at the initial 100 cycles

112.

Dang et al. prepared a composite membrane separator composed of cerium based UiO-67 (MOF) and a glass fiber. Prepared Ce-UiO-67 efficiently adsorbed LiPS and catalyzed their conversion, thus suppressing the associated shuttle effects. In addition, this type of MOF theoretically provides rich lithium-philic functional groups to attain rapid Li+ ion transportation, leading to achieve stable Li plating and stripping. The resulting LSB delivered 919 mAh g−1 at initial cycle and a small decay rate of 0.04% per cycle for 500 cycles at 1 C 113.

Su et al. also prepared a cerium-based MOF separator and used Ce-UiO-66-NH2 as the MOF material. Strong interaction between LiPS and the metal sites in UiO-66-NH2, as well as being the physical barrier for LiPS enabled this type of separator to inhibit the shuttle effect. The assembled LSB offered high capacity of 1,366 mAh g−1 initially with stable cycling property at 0.2 C. In addition, capacity decay was only 0.09% per cycle at 300 cycles at 1 C. 114

A conductive carbon (Ketjenblack) and zeolite imidazole framework-8 (ZIF-8)/polypropylene composite separator was prepared by Ma et al. 115 ZIF-8 and Ketjenblack were mixed with 1 : 4 mass ratio in ethanol for 24 h, and then ultrasonically dispersed for 20 min. After that, the homogeneous solution was coated onto a commercial separator via vacuum filtration and followed by vacuum drying at 60 °C for 24 h. The resulting separator comprised Ketjenblack, ZIF-8, and PP with a low coating load of 0.06 mg cm-2. Ketjenblack/ZIF-8/PP can efficiently absorb LiPS due to Lewis acid–base interaction between ZIF-8 and LiPS. This interaction could decrease the dissolution of LiPS as well as the shuttle effect, thereby enhancing the electrochemical properties of the assembled LSB. When 0.1 C of current density was applied, the assembled LSB exhibited low polarization, a capacity of 1235.6 mAh/g initially, and good capacity retention rate of 59.27% after 100 cycles115.

2.12. Separator Material: Quantum Dot

Quantum dots (QDs) are generally super small crystalline particles with the size range of 1.0–10 nm. Recently, QDs have gained much attention for being interesting materials for electrochemical energy storage due to their large specific surface area, tunable size, short ion/electron transportation path, adjustable photoluminescence, and feasible surface functionalization116,117. In addition, it was reported that QD can modify separators to suppress the shuttle effect owing to their effective interaction with LiPS118.

Atomic layer deposition method was applied to prepare a TiO

2 quantum dot modified multiwalled carbon nanotube as deposition material for LSB separator and succeeded in preventing the LiPS shuttling effect and improving the coulomb efficiency and cycle stability (

Figure 15a)

119. It was suggested that these positive effects were achieved due to interaction between TiO

2 quantum dots and LiPS that could adsorb soluble polysulfide compounds, leading to suppressing the shuttle effect. The interlayer also had abundant spacing and excellent conductivity because of the multiwalled carbon nanotube. The assembled LSB showed 1083 mAh g

-1 as initial capacity and kept a cycle capacity of 610 mAh g

-1 after 600 cycles at a rate of 838 mA g

-1. Capacity decay rate was only 0.072% per cycle (

Figure 15b)

119.

A superlight PP-coated film with multiwalled carbon nanotubes/nitrogen doped carbon quantum dots (MWCNTs/NCQDs) was synthesized by Pang et al. (

Figure 15c)

120. The weight of the MWCNT/NCQD coating per area was as low as 0.15 mg cm

-2 (

Figure 15d).

It was found to have superior capacity retention and self-discharge suppression compared to the LSB made by Chung et al. with an MWCNT-modified separator

121. The synergistic influence of the MWCNTs and NCQDs was ultimately positive, resulting in 1,331 mAh g

-1 as an initial capacity and presented stable cycling performance. The capacity decay was as low as 0.05% per cycle at 0.5 C, over 1,000 cycles (

Figure 15e).

Yu et al. developed a Mo

2C quantum dot (MQD) anchored nitrogen doped graphene deposited separator (MQD/NG)

122.

Figure 15f are the optical and TEM pictures of the separator with MQD/NG/PP surface after 200 cycles. Polar Mo

2C QDS offer an uniform lithium deposition and good chemical adsorption of LiPS. The LSB operated more than 1,600 hours with dendrite free lithium deposition at current density of 10 mA cm

-2. The capacity of 1,230 mAh g

-1 was observed under stable cycle performance after 100 cycles at 0.2C without obvious capacity decay (

Figure 15g).

Liu et al. developed a zinc sulfide quantum dots/reduced graphene aerogel modified separator123. The ZnS quantum dots were effective as LiPS-anchoring and catalytic sites, which could promote the redox reaction of sulfur and mitigate the shuttle effect. The 3D porous reduced graphene aerogel assisted in physically blocking the migration of LiPS. As a consequence, 1211 mAhg-1 at initial capacity was observed at 0.1 C and presented stable cycling performance over 500 cycles at 1C123.

Zhang et al. applied MoP quantum dot and nitrogen, phosphorous co-doped polypyrrole (PPy) composite material to commercial separator for LSBs124. The MoP quantum dots exhibited strong chemisorption and catalytic conversion performance for LiPS capture and conversion. In addition, N,P co-doped PPy substrates offered flexible pathways for Li+/electron transportation and also behaved as a physical barrier to mitigate the shuttle effect. The capacity of 739 mAh g-1 at 3 C was observed with stable cycle performance (600 mAh g-1 at 1 C after 600 cycles, 0.052% decay per cycle). Density functional theory calculations elucidated that the MoP quantum dots possess an enough adsorption energy for S8 and Li2Sn, which could lower the initial nucleation energy barrier of Li2S that might be helpful to accelerate Li2S reaction kinetics.

Cobalt aluminum layered double hydroxide quantum dots (LDH-QDs) was combined with nitrogen doped graphene (NG) as a coated material for LSB separator125. XPS, Li2S nucleation tests and electrokinetic analyses clarified that the porous LDH-QDs/NG owned rich active hydroxyl groups and Co2+ sites, that was effective in catching LiPS by strong chemical interactions and promote the conversion reaction kinetics. Average thickness of the prepared LDH-QDs/NG coated separator was approximately 17 μm and had high ionic conductivity of 2.67 mS cm–1. LSB assembled with this separator presented1,228 mAh g–1 capacity at 0.1 C with 0.041% capacity decay per cycle over 1,200 cycles at 1.0 C125.

2.13. Separator Material: Mxenes

Two dimensional transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides in the form of a material known as “MXenes” gained an increasing amount of attention due to their high conductivity, rich surface functionality, and exclusive 2D morphologies, especially for energy storage devices126,127.

Gogotsi's group first prepared Ti3C2 by removing Al atoms selectively from layered hexagonal ternary carbide (space group P63/mmc) in 2011, Ti3AlC2, with hydrofluoric acid (HF) treatment in water128. This study focused Ti3C2 as a typical MXene material and stimulated more researchers to investigate its physical and electrochemical properties129,130. In general, MXenes (such as Ti3C2Tx and V2CTx) are two dimentinal layered materials which can obtain from transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides (denoted as the MAX/Mn+1AXn phase)131. These interesting materials can be acquired by selectively etching SP elements layers from their corresponding 3D MAX phases. MAX phases indicates layered ternary metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides, with a formula of Mn + 1AXn (n = 1, 2, 3), in which M, A, and X express early d-block transition metals, main group SP elements (predominantly IIIA or IVA), and either or both C and N atoms, respectively. So far, more than 70 MAX phases have been reported132. Typical MXene are Ti3C2133, Ti2C134, (Ti0.5, Nb0.5)2C, (V0.5, Cr0.5)3C2, Ti3CN135, Ta4C3, Nb2C, V2C, and Nb4C3 etc... Additional interesting properties of Mxene is that the surfaces of the exfoliated layers are terminated with F, OH, and/or O groups in general. Therefore, these terminated MXene species will be regarded as Mn + 1XnTx, in which T indicates the surface groups (F, OH, and/or O) and “x” is the number of terminations136. These surface groups can also assist in capturing LiPS diffusion.

Glass fiber and Ti

3C

2 composite separator was prepared by Lin et al. by vacuum filtration process

137. As displayed in

Figure 16a, a few layers of conductive Ti

3C

2 nanosheet with an average 1 – 4 nm thickness, was deposited on a glass fiber separator. This type of separator can offer strong LiPS adsorbing sites due to their high porosity, and LiPSs shuttle effect was successfully reduced when compared to a glass fiber separator without Mxene. LSB assembled with Mxene/glass fiber composite separator offered a capacity of 820 mAh g

-1 at initial cycle and it was 721 mAh g

-1 after 100 cycles at 0.5 A g

-1, that is approximately 15 times stronger than LSBs with commercial separator. (Figure16b). High performance was achieved due to conductive property and strong interaction of Ti

3C

2 towards LiPS.

TiO

2-MXene heterostructures were prepared by Jiao et al. via the partial oxidation of Ti

3C

2T

x nanosheets

138. It was shown that this crafted structure had a large surface area, strong ability to catch LiPSs, and high conductivity and electrocatalytic activity.

Figure 16c depicts how TiO

2 uniformly distributed over MXene sheets can offer numbers of effective adsorbing sites to catch LiPS, while its hetero-structure interface assures the rapid diffusion of LiPS to MXene, leading to its high catalytic activity for rapid LiPS conversion. The discharge capacity of LSB assembled with this TiO

2-MXene deposited separator was 662 mAh g

-1 after 200 cycles at 0.5 C, which indicates 93% of capacity retention, proves its high sulfur utilization efficiency (

Figure 16d).

MXene sulfation has also been studied. Yao et al. developed a flexible, conductive MXene (Ti3C2Tx) sandwich structured layer and the hetero-structure surface of TiS2/TiO2 was created by vulcanization139. The TiO2 nanoparticles worked as an adsorbent to catch LiPSs and the TiS2 functioned as a catalyst to accelerate the long-chain LiPSs conversion to short-chain Li2S2/Li2S with the help of high conductivity of Ti3C2Tx. It was found that the prepared layer protected the lithium anode by suppressing LiPS depositing on its surface. As a result, high electrochemical performance long term stability was achieved (capacity decay rate was 0.048% per cycle up to 500 cycles at 1 C).

Mxene has been combined with other functional materials to create even more desirable separators. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) obtained with guanidinium salts have been gaining high attention as they possess strong covalent bonds and rich pore channels. It was suggested that guanidinium salts could capture LiPS owing to their electrostatic interaction nature. Li et al. prepared ionic covalent organic nanosheets with guanidinium salts to prevent Ti3C2 restacking and capturing LiPS. This material was uniformly applied to polymer separator with simple vacuum filtration process. The charge transfer resistance of LSB assembled with this type of separator was low and a capacity decay was 0.006% per cycle at 2,000 cycles at a current rate of 2 C140.

Combining Mxene with functional polymers can be useful way to facilitate Li+ transport. Wang et al. prepared a laminar Nafion – MXene composite141. Interestingly, Nafion worked as a surfactant, or dispersant, which results in obtaining an ordered layer-by-layer structured MXene sheets by filtration. By comparing this composite layer to each Nafion and MXene material, physical resistance of MXene and electrostatic repulsion of Nafion interacted synergistically to reduce the shuttle effect. LSB made with this functional separator exhibited good cycling stability and capacity decay was as low as 0.03% per cycle over 1,000 cycles at 1C. It was also found that the MXene promoted the re-utilization of polysulfides owing to its high electrical conduction, and effective Li+ transport was achieved by Nafion.

2.14. Other Functional Separator Materials

There are some additional functional materials that are being researched for use as LSB separators that either demonstrate the ability to capture LiPS to suppress the shuttle effect or provide catalytic sites to promote the redox reaction of sulfur related species.

He et al. developed vanadyl phosphate (VOPO4) sheets for such a purpose142. Specifically, two dimensional VOPO4 sheets with rich active sites were designed to adsorb LiPS by V–S bond forming. Due to the intrinsic electrical repulsion between the polysulfide anions, advanced time/space-resolved operando Raman analysis revealed that polysulfides rich surface could further evolved to a “polysulfide-phobic” interface. By implementing these “polysulfide-phobic” sites in the separator, the LSB would have superior long-term cycling stability.

Pure Nafion, i.e., without Mxene, was coated onto a commercial separator by Huang et al. 143 in order to create ion selectivity. SO3− groups in sulfonate-ended perfluoroalkyl ether groups in separator, allowed Li+ as positively charged species hopping but did not allow the hopping of negative ions, such as polysulfide anions (Sn2−) due to coulombic interactions. This cation selective membrane worked as an effective electrostatic shield for polysulfide anions and succeeded in confining the LiPS to the cathode side1.

Some nature-derived materials have also been studied. A lignin nanoparticle-coated commercial separator was prepared by Zhang et al. 144 The lignin-coated separator had abundant electron-donating groups and was expected to result in the chemical binding of LiPS to reduce the shuttle effect. With a LSB with cathode composed of sulfur and commercially available acetylene black (approximately 73.8 wt% sulfur content) was assembled, and showed improved cycling stability compared to a commercial separator for over 500 cycles at a current density of 1 C.

Cellulose is another abundant and environmentally friendly organic resource and can be obtained from plant biomass. Nano-fibrillated cellulose (NFC) has been used to prepare porous natural separator membranes with a process learned from the paper industry. A separator composed of NFC was investigated regarding its porosity, thickness, wettability, electrochemical stability and its electrochemical performance as a functional separator for an LSB was evaluated. Interestingly, the mass of the commercial separator and the thinnest separator prepared in their study were very similar, although the cellulose-based separator was thicker. Top-down views of the NFC_20PO (the separator prepared by adding paraffin oil and polyethylene glycol hexadecyl ether as a surfactant) and NFC_20 (the separator prepared without any additive in water dispersion) are shown in

Figure 16. The NFC_20PO (

Figure 17a) separator has an open-pore structure with interconnected pores of diameters between 100 nm and 1 μm. The addition of PO and surfactant enabled the formation of pores, however, some parts remained partially closed, which implies that the preparation procedure is still not fully optimized. In contrast, the separator prepared without additives showed a much more closed, densely packed surface without any visible macro pore structure (

Figure 17b). It was suggested that the NFC fibers tend to compactly collapse from capillary action during the evaporation of water and are fixed with strong hydrogen bonds of cellulose chains, thus yielding dense-structured membranes

145. It was also demonstrated that the electrochemical performance of the NFC separator was superior to the conventional polyolefin separator

146.

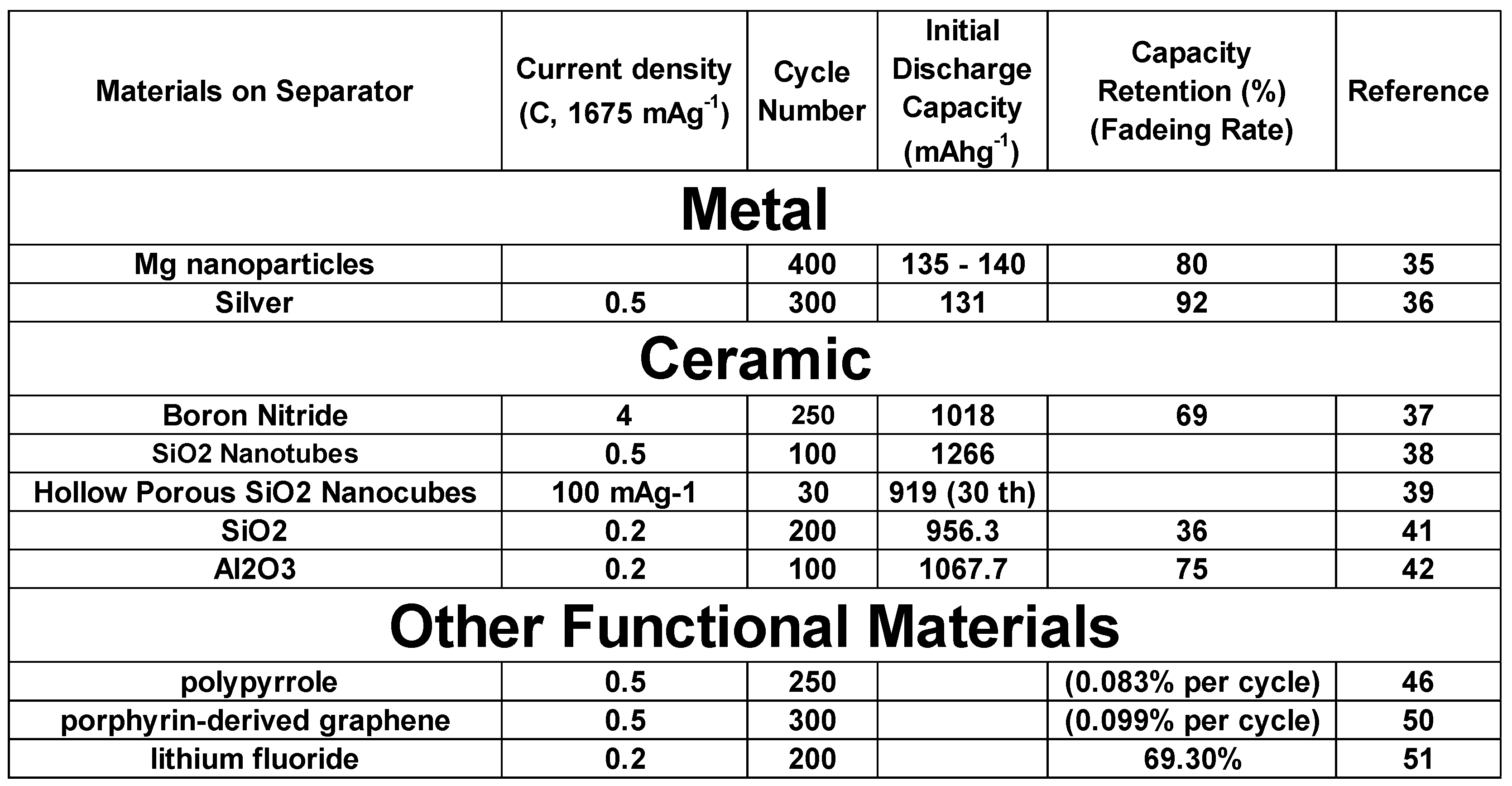

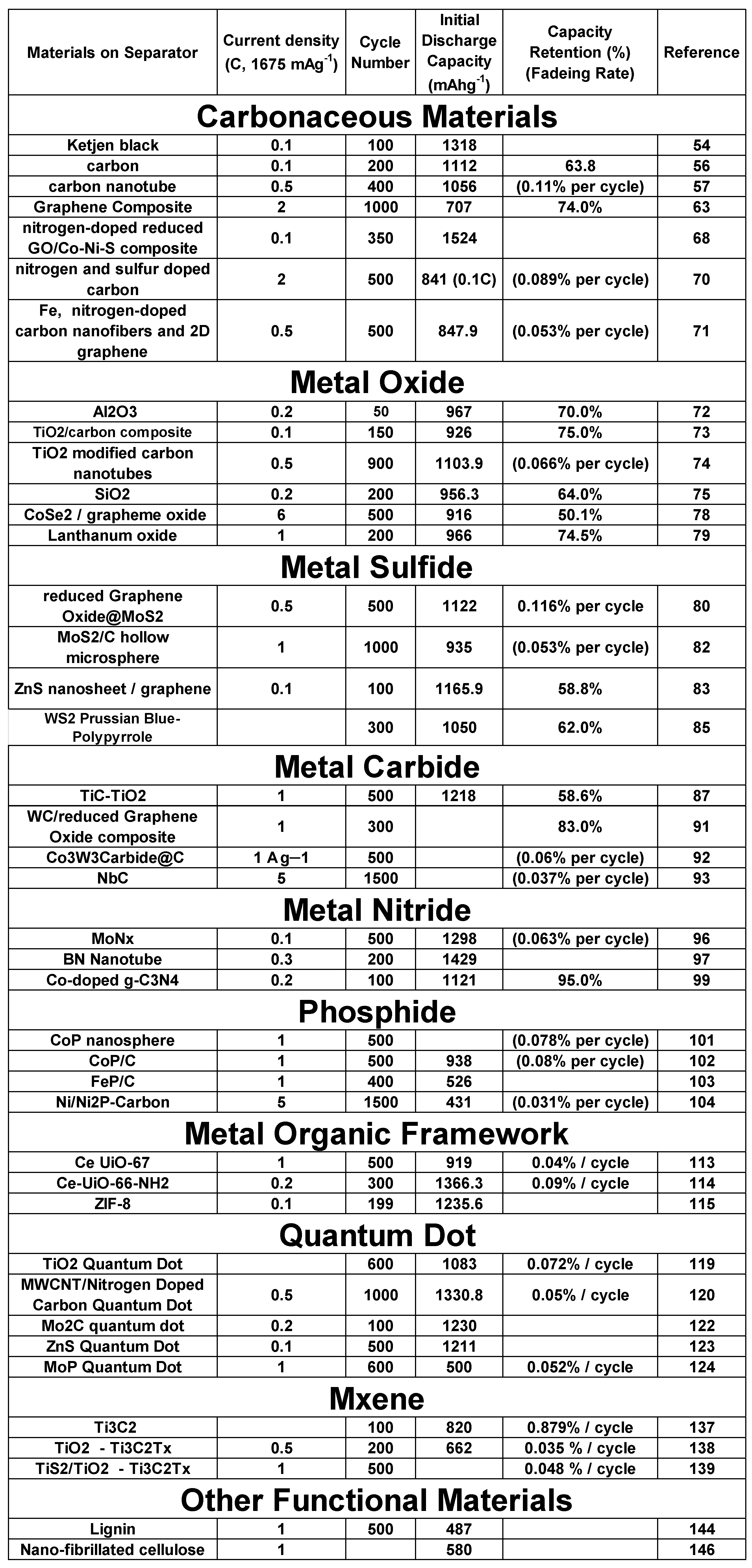

As we have explained above, various type of materials were applied to LSB separators and those are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, depending upon whether they are on anode or cathode side. The one of major role for those separator materials were to capture LiPS in order to suppress shuttle effect. Each materials have advantage and disadvantage. In addition, for future study, combining these materials and creating composite materials could be also another strategy to gain even better performance.

3. Necessary Properties for LSB Separators

We have explained what actual materials have been attempted to be applied for LSB separators so far. Now we would like to mention more about necessary properties for LSB separators.

In general, electronic resistance and ion conductivity needs to be high for LSB separators. Ionic conductivity is related to separator structure including porosity and tortuosity. Porosity is necessary to store enough electrolytes to keep high ionic transference. Tortuosity is also an importance factor. Tortuosity is a quantity to describe the morphology. As tortuosity becomes smaller, conductivity will be higher. Furthermore, wettability is also a key factor to determine an ionic conductivity. Obviously, higher electrolyte permeation could serve a fluent route for lithium ion transference. It should also be noted that the pore size and tortuosity should be uniform in order to obtain stable current density. Furthermore, separators should shrink or deform under acute temperature rise or drop during cell operation, which is significantly necessary characteristic for rechargeable battery stability 147.

3.1. Thickness, Porosity and Pore Size

In general, separator with smaller thickness should exhibit lower ionic resistance which would result in gaining higher energy density. So far, separator thickness ranges 20 - 50 µm whereas that of commercial separator thickness are 20 - 25 µm148. Thinner separator tends to cause more puncture formation during battery manufacturing which would be the reasons for battery short circuits and explosions. The thickness uniformity and equality is critical because non uniform separator could cause electrodes dendrites formation which would cause disaster during battery operation.

Regarding separator porosity, it is defined by the ratio of the sum of the volumes of the pores and liquids to the apparent pore volume149.

Porosity can be calculated by following equation

Where ρ𝑚 is the apparent density and ρ𝑝 is the density of the separator material.

In general, the porosity is calculated by the weight difference before and after the separator is soaked in a liquid, as shown in equation

In which 𝑊 is the weight of void separator and 𝑊0 the weight of the separator soaked in the liquid, ρ𝐿 and 𝑉0 represent the density of the liquid and the geometric volume of the separator, respectively.

Porosity needs to be optimized to make sure enough electrolytes are filled in the pores to assure ion conductivity. For example, if the porosity is too high, the separator itself would be fragile. If the porosity is too small, ion conductivity would not be high enough to ensure good electrochemical performance. Optimized porosity of separator for commercial lithium ion battery is known to possess approximately 40 % and that of lithium sulfur battery is still controversial since there is not much commercialized lithium sulfur battery. Good separator should have a pore size that is large enough for the lithium ions to pass through while small enough so that all the active components and dendrite growths in the electrode can be cut off to avoid short circuits150.

3.2. Tortuosity and Permeability

Tortuosity is the fraction of the mean distance traveled to the direct distance. For separators, tortuosity is a factor describing the effect of the geometric shape of the separator on the ionic conductivity

151, and it can be expressed by following equation.

where ε is the porosity, 𝑅𝑠 and 𝑅0 are the separator resistance before and after soaked in liquid electrolyte.

Geometric effective transport coefficient is a measure of effective ionic transport of separators’ morphology, and can be calculated as 𝛿 = ε/τ. For example, with a 45 % porosity and a tortuosity of 2.5, the effective transport coefficient would be 0.18. The transport coefficient value of 0.18 means that the morphology change will reduce the ionic conductivity by 18% compared to the pure electrolyte.

The permeability is similar to tortuosity. Geometric structure can influence the ionic conductivity by pressure difference and the permeability can be applied in this respect.

Darcy’s law can be used to define the fluid rate through a porous surface, which can be calculated by following equation

η is the viscosity, ∇𝑃 is the applied pressure gradient, 𝑢 is the average velocity of the fluid when penetrating the porous surface.

Moreover, the Gurley value, G, that is correlated with the permeability, is often more used instead

152. It is the value of the time necessary for air to penetrate into a certain area of separator, which can be defined as

In which the κ is permeability, ∆P is the pressure difference, A represents the area, 𝑉 refers to air volume, 𝐿 is the separator thickness and η𝑎𝑖𝑟 is the air viscosity

3.2. Wettability

Wettability is also a one of critical factor for separators because they can absorb and retain electrolytes. When wettability is high, one can say that the separators can possess a smaller internal resistance, which would be beneficial for the battery performance153. It is also known that wettability is related to porosity, pore size, morphology and characteristics of different separators.

3.3. Mechanical Properties and Thermal Behavior

Mechanical strength is necessary for separators to prevent the battery from dendrite forming, short circuit and accidental break. Tensile strength and puncture strength are the most important mechanical properties. Especially, high tensile strength is necessary in the stretched directions for separators. Whereas the puncture strength is the weight which is necessary for a needle to make a puncture on the separator153. Puncture strength has been applied to determine how hard separators can bear short circuit during battery assembly, manufacture and electrochemical reactions. Sufficient puncture strength is necessary to confirm that separators do not break otherwise a short circuit will happen which is the critical damage for the battery. The separator should not deform or shrink because of temperature rise. Moreover, separators must have a shut-down function to prevent a short circuit or overheating and following possible conflagration.

In summary, even there were many strategies and candidate materials for separators which may improve the LSB electrochemical performance, above characteristics such as separator thickness, porosity (pore size), tortuosity, electrolyte wettability and permeability needs to be carefully considered for selecting materials. Not to mention mechanical strength of separator is also important. In brief, one has to choose good separator materials and also they need to be optimized to gain high LSB performance.

The author group also enhanced the capacity and cyclic stability of an LSB by optimizing the cathode structure, electrolyte composition, and separator. The separator was coated with a metal organic framework-derived ink to enhance its LiPS capturing ability111, 154-157. Details will be described in a forthcoming paper.

Figure 1.

Structure image of LSBs with liquid electrolyte8.

Figure 1.

Structure image of LSBs with liquid electrolyte8.

Figure 2.

A ordinary charge/discharge profile curves for LSBs9.

Figure 2.

A ordinary charge/discharge profile curves for LSBs9.

Figure 3.

36SEM photograph of the surface of.(a) bare lithium (b) Ag co-deposited lithium. Cross-sectional SEM images of (c) bare lithium (d) Ag co-deposited lithium. Symmetric LSBs are discharged at a current density of 2.5 mA cm-2.

Figure 3.