Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

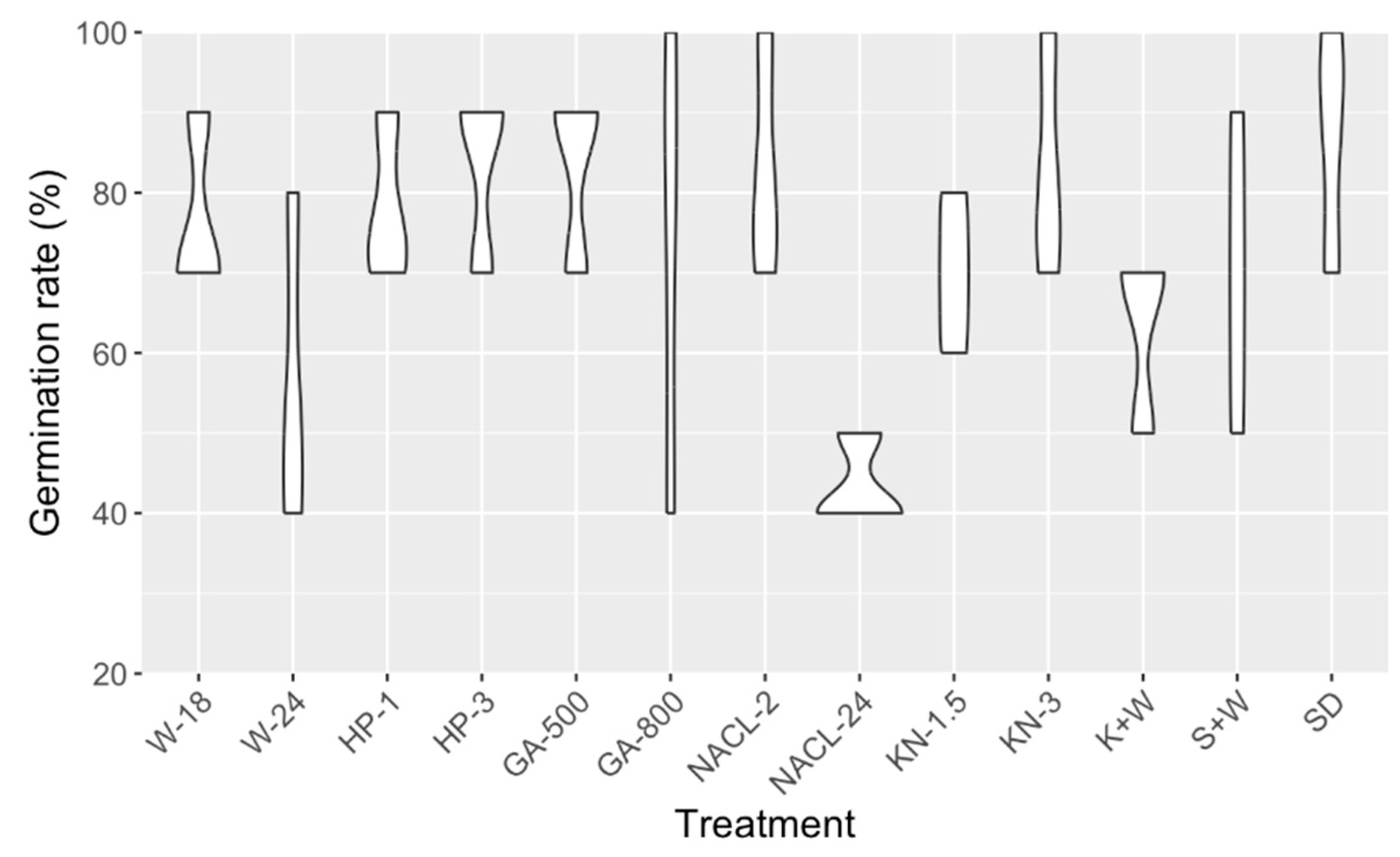

2.1. Germination test

2.2. Characterization of the agronomic traits

2.3. Characterization of the morphological traits

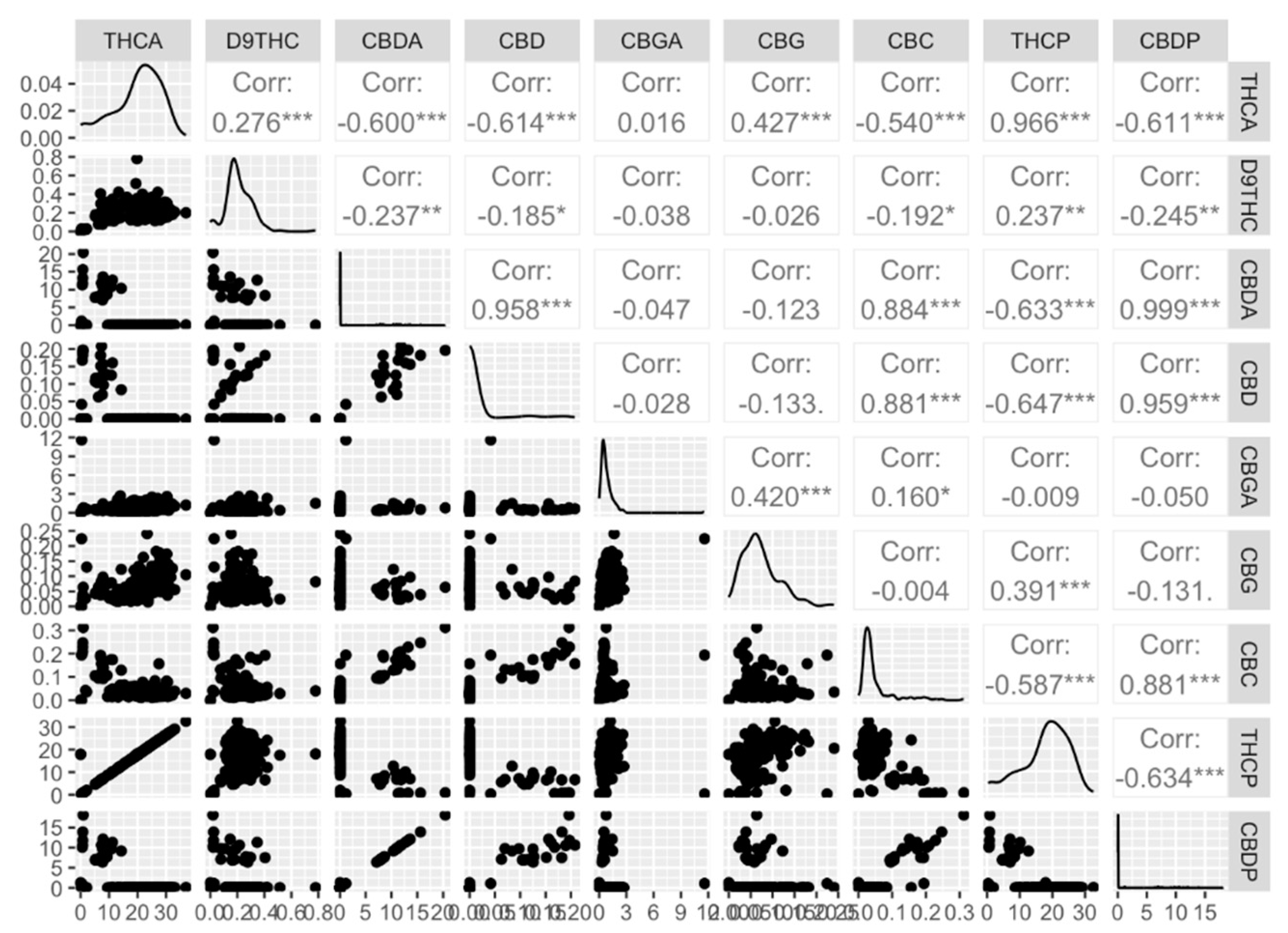

2.4. Characterization of the biochemical traits

2.5. Influence of agronomic and morphological characteristics on major cannabinoids

2.6. Impact of the origin of the cannabis on agronomic, morphological, and biochemical traits

2.6.1. Regular female vs. feminized seeds

2.6.2. Cuttings vs. seeds

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Germination test

4.2. Plant materials

4.3. Growing conditions

4.4. DNA extraction and sex determination

4.4.1. Sample collection and preparation

4.4.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Sex Determination

4.5. Phenotype characterization

4.5.1. Agronomic and morphological traits

4.5.2 Chemical analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lapierre, É.; Monthony, A.S.; Torkamaneh, D. Genomics-Based Taxonomy to Clarify Cannabis Classification. Genome 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonini, S.A.; Premoli, M.; Tambaro, S.; Kumar, A.; Maccarinelli, G.; Memo, M.; Mastinu, A. Cannabis Sativa: A Comprehensive Ethnopharmacological Review of a Medicinal Plant with a Long History. J Ethnopharmacol 2018, 227, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frère Marie Victorin. Flore Laurentienne, 3rd ed.; Gaëtan, Morin, Ed.; Montréal, 1935; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Small, E. Cannabis 2017.

- Hesami, M.; Pepe, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Rakei, A.; Baiton, A.; Maxwell, A.; Jones, P. Recent Advances in Cannabis Biotechnology. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Handbook of Cannabis Production in Controlled Environments. Handbook of Cannabis Production in Controlled Environments 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.C.; Merlin, M.D. Cannabis. Evolution and Ethnobotany, University of Cali 2013.

- Monthony, A.S.; Ronne, M. de; Torkamaneh, D. Exploring Ethylene-Related Genes in Cannabis Sativa: Implications for Sexual Plasticity. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.04.28.538750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Cronquist, A. A PRACTICAL AND NATURAL TAXONOMY FOR CANNABIS. Taxon 1976, 25, 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.; Salentijn, E.M.J.; Paulo, M.J.; Thouminot, C.; van Dinter, B.J.; Magagnini, G.; Gusovius, H.J.; Tang, K.; Amaducci, S.; Wang, S.; et al. Genetic Variability of Morphological, Flowering, and Biomass Quality Traits in Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.). Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 497381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monthony, A.; Page, S.; Hesami, M.; Jones, A. The Past, Present and Future of Cannabis Sativa Tissue Culture; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hesami, M.; Baiton, A.; Alizadeh, M.; Pepe, M.; Torkamaneh, D.; Jones, A.M.P. Advances and Perspectives in Tissue Culture and Genetic Engineering of Cannabis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, Vol. 22, Page 5671 2021, 22, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartland, J.M.; Clarke, R.C.; Watson, D.P. Hemp Diseases and Pests. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2000, 11, 276. [Google Scholar]

- Zlas, J.; Stark, H.; Seligman, J.; Levy, R.; Werker, E.; Breuer, A.; Mechoulam, R. Early Medical Use of Cannabis. Nature 1993, 363, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamaneh, D.; Jones, A.M.P. Cannabis, the Multibillion Dollar Plant That No Genebank Wanted. Genome 2021, 65, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crépault, J.F. Cannabis Legalization in Canada: Reflections on Public Health and the Governance of Legal Psychoactive Substances. Front Public Health 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannabis - Worldwide | Statista Market Forecast. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/hmo/cannabis/worldwide (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Martínez, V.; Iriondo De-Hond, A.; Borrelli, F.; Capasso, R.; Del Castillo, M.D.; Abalo, R. Cannabidiol and Other Non-Psychoactive Cannabinoids for Prevention and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Disorders: Useful Nutraceuticals? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, Vol. 21, Page 3067 2020, 21, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.; Goodman, S. Knowledge of Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol Levels Among Cannabis Consumers in the United States and Canada. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2022, 7, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudge, E.M.; Murch, S.J.; Brown, P.N. Chemometric Analysis of Cannabinoids: Chemotaxonomy and Domestication Syndrome. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 13090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.B. Taming THC: Potential Cannabis Synergy and Phytocannabinoid-Terpenoid Entourage Effects. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 163, 1344–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholey, A.; Kennedy, D.; Wesnes, K.; Persson, J.; Bringlov, E.; Nilsson, L.G.; Nyberg, L.; Solomon, P. The Psychopharmacology of Herbal Extracts: Issues and Challenges (Multiple Letters). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005, 179, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via, S.; Lande, R. GENOTYPE-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTION AND THE EVOLUTION OF PHENOTYPIC PLASTICITY. Evolution (N Y) 1985, 39, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, C.D. THE EVOLUTION OF PHENOTYPIC PLASTICITY IN PLANTS. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 2003, 17, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcaccia, G.; Palumbo, F.; Scariolo, F.; Vannozzi, A.; Borin, M.; Bona, S. Potentials and Challenges of Genomics for Breeding Cannabis Cultivars. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Il; Kim, J.Y. New Era of Precision Plant Breeding Using Genome Editing. Plant Biotechnol Rep 2019, 13, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J. The Pot Book : A Complete Guide to Cannabis : Its Role in Medicine, Politics, Science, and Culture. 2010, 551.

- Jones, M.; Monthony, A.S. Cannabis Propagation. Handbook of Cannabis Production in Controlled Environments 2022, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, K.; Jones, A.M.P.; Torkamaneh, D. Accumulation of Somatic Mutations Leads to Genetic Mosaicism in Cannabis. Plant Genome 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Singh, D.; Singh, U.; Chauhan, N.; Eftekhari, M.; Sadh, R.K. Somaclonal Variations and Their Applications in Horticultural Crops Improvement. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvick, D.N. Biotechnology in the 1930s: The Development of Hybrid Maize. Nature Reviews Genetics 2001 2:1 2001, 2, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, H.A. Hybrid Seeds in History and Historiography. Isis 2022, 113, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breseghello, F. Traditional and Modern Plant Breeding Methods with Examples in Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Alexandre Siqueira Guedes Coelho. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, J.N.; DeClerck, G.; Greenberg, A.; Clark, R.; McCouch, S. Next-Generation Phenotyping: Requirements and Strategies for Enhancing Our Understanding of Genotype–Phenotype Relationships and Its Relevance to Crop Improvement. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2013 126:4 2013, 126, 867–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshan, P.M. PLANT BREEDING: Classical to Modern. Plant Breeding: Classical to Modern 2019, 1–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, P.J. Effects of Stratification, Germination Temperature, and Pretreatment with Gibberellic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide on Germination of ‘Fry’ Muscadine (Vitis Rotundifolia) Seed. HortScience 2008, 43, 853–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, D.; Nikolic, Z.; Sikora, V.; Tamindžic, G.; Petrovic, G.; Ignjatov, M.; Miloševic, D. Comparison of Methods for Germination Testing of Cannabis Sativa Seed. Ratarstvo i povrtarstvo 2019, 56, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.H.; Cha, Y.L.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, K.S.; Kwon, D.E.; Kang, Y.K. Investigation of Suitable Seed Sizes, Segregation of Ripe Seeds, and Improved Germination Rate for the Commercial Production of Hemp Sprouts (Cannabis Sativa L.). J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 2819–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruttanaruangboworn, A.; Chanprasert, W.; Tobunluepop, P.; Onwimol, D. Effect of Seed Priming with Different Concentrations of Potassium Nitrate on the Pattern of Seed Imbibition and Germination of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.). J Integr Agric 2017, 16, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A.; Singh Yadav, N.; Gaudet, D.; Kovalchuk, I. Development and Standardization of Rapid and Efficient Seed Germination Protocol for Cannabis Sativa. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.; Sehar, S.; Perveen, M.; Gelani, S.; Basra, S.M.A.; Farooq, M. Seed Pretreatment with Hydrogen Peroxide Improves Heat Tolerance in Maize at Germination and Seedling Growth Stages. Seed Science and Technology 2008, 36, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Rengel, Z.; Storer, P.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Solaiman, Z.M. Industrial Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) Varieties and Seed Pre-Treatments Affect Seed Germination and Early Growth of Seedlings. Agronomy 2022, Vol. 12, Page 6 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grain Cultivars - UniSeeds Inc. Available online: https://www.uniseeds.ca/en/varieties/grain-cultivars/ (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Törjék, O.; Bucherna, N.; Kiss, E.; Homoki, H.; Finta-Korpelová, Z.; Bócsa, I.; Nagy, I.; Heszky, L.E. Novel Male-Specific Molecular Markers (MADC5, MADC6) in Hemp. Euphytica 2002, 127, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, M.; Palumbo, F.; Vannozzi, A.; Scariolo, F.; Sacilotto, G.B.; Gazzola, M.; Barcaccia, G. Developing and Testing Molecular Markers in Cannabis Sativa (Hemp) for Their Use in Variety and Dioecy Assessments. Plants 2021, 10, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Vicente-Gonzalez, L.; Luis, J.; Maintainer, V.-V. Package “PERMANOVA” Type Package Title Multivariate Analysis of Variance Based on Distances and Permutations Version 0. 2.0. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B.G.“Zenith” and S.J.M.; Carl, P.; Boudt, K.,; Bennett, R.; Ulrich, J.; Zivot, E.; Cornilly, D.; Hung, E.; Lestel, M.; Balkissoon, K.; et al. Econometric Tools for 45 Performance and Risk Analysis. Available online: https://github.com/braverock/PerformanceAnalytics (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J. Visualization of a Correlation Matrix [R Package Corrplot Version 0.92]. 2021.

- An Industry Makes Its Mark | Deloitte Canada. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/ca/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/an-industry-makes-its-mark.html (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Pepe, M.; Hesami, M.; Jones, A.M.P. Machine Learning-Mediated Development and Optimization of Disinfection Protocol and Scarification Method for Improved In Vitro Germination of Cannabis Seeds. Plants 2021, Vol. 10, Page 2397 2021, 10, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.H.; Stack, G.M.; Jiang, Y.; Taşklran, B.; Cala, A.R.; Toth, J.A.; Philippe, G.; Rose, J.K.C.; Smart, C.D.; Smart, L.B. Morphometric Relationships and Their Contribution to Biomass and Cannabinoid Yield in Hybrids of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa). J Exp Bot 2021, 72, 7694–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backer, R.; Schwinghamer, T.; Rosenbaum, P.; McCarty, V.; Eichhorn Bilodeau, S.; Lyu, D.; Ahmed, M.B.; Robinson, G.; Lefsrud, M.; Wilkins, O.; et al. Closing the Yield Gap for Cannabis: A Meta-Analysis of Factors Determining Cannabis Yield. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 434233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim-Feil, E.; Pembleton, L.W.; Spooner, L.E.; Malthouse, A.L.; Miner, A.; Quinn, M.; Polotnianka, R.M.; Baillie, R.C.; Spangenberg, G.C.; Cogan, N.O.I. The Characterization of Key Physiological Traits of Medicinal Cannabis (Cannabis Sativa L.) as a Tool for Precision Breeding. BMC Plant Biol 2021, 21, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Q. Contrasting Strategies of Alfalfa Stem Elongation in Response to Fall Dormancy in Early Growth Stage: The Tradeoff between Internode Length and Internode Number. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0135934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, D.; Feathers, C.; Huscher, E.L.; Holmes, B.; Haas, J.A.; Kane, N.C. Widely Assumed Phenotypic Associations in Cannabis Sativa Lack a Shared Genetic Basis. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, J.; Bernstein, N. Chemical and Physical Elicitation for Enhanced Cannabinoid Production in Cannabis. Cannabis sativa L. - Botany and Biotechnology 2017, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Hausman, J.F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis Sativa: The Plant of the Thousand and One Molecules. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 174167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazekamp, A.; Fischedick, J.T. Cannabis - from Cultivar to Chemovar. Drug Test Anal 2012, 4, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bakel, H.; Stout, J.M.; Cote, A.G.; Tallon, C.M.; Sharpe, A.G.; Hughes, T.R.; Page, J.E. The Draft Genome and Transcriptome of Cannabis Sativa. Genome Biol 2011, 12, R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim-Feil, E.; Elkins, A.C.; Malmberg, M.M.; Ram, D.; Tran, J.; Spangenberg, G.C.; Rochfort, S.J.; Cogan, N.O.I. The Cannabis Plant as a Complex System: Interrelationships between Cannabinoid Compositions, Morphological, Physiological and Phenological Traits. Plants 2023, 12, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverty, K.U.; Stout, J.M.; Sullivan, M.J.; Shah, H.; Gill, N.; Holbrook, L.; Deikus, G.; Sebra, R.; Hughes, T.R.; Page, J.E.; et al. A Physical and Genetic Map of Cannabis Sativa Identifies Extensive Rearrangements at the THC/CBD Acid Synthase Loci. Genome Res 2019, 29, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Choi, P.; Park, Y.T.; Kim, T.; Ham, J.; Kim, J.C. The Cannabinoids, CBDA and THCA, Rescue Memory Deficits and Reduce Amyloid-Beta and Tau Pathology in an Alzheimer’s Disease-like Mouse Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 6827 2023, 24, 6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizpurua-Olaizola, O.; Soydaner, U.; Öztürk, E.; Schibano, D.; Simsir, Y.; Navarro, P.; Etxebarria, N.; Usobiaga, A. Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis Sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes. J Nat Prod 2016, 79, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, G.M.; Toth, J.A.; Carlson, C.H.; Cala, A.R.; Marrero-González, M.I.; Wilk, R.L.; Gentner, D.R.; Crawford, J.L.; Philippe, G.; Rose, J.K.C.; et al. Season-Long Characterization of High-Cannabinoid Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) Reveals Variation in Cannabinoid Accumulation, Flowering Time, and Disease Resistance. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, C.B.; Gentner, W.A. Greenhouse Propagation of Cannabis Sativa L. by Vegetative Cuttings. Econ Bot 1979, 33, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).