Submitted:

16 September 2023

Posted:

18 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- At very low shear rates, their shear viscosity is constant (and slightly larger than that of the solvent), but more importantly, they are characterised by a single stress relaxation time (unlike some polymer solutions that exhibit a spectrum of relaxation times), yielding a near-Maxwell behaviour [18]. The response of these entangled solutions of wormlike surfactant solutions to unsteady shear-flows can be described with the standard Maxwell model.

- At higher shear rates, the entanglements may begin to break, so in order to model this kind of complex fluid, it is necessary to account for the reversible assembly and disassembly of the entangled wormlike-chain solution, which is usually modelled using a kinetic equation that could describe the level of internal structure of the fluid. Apart from viscoelasticity, these solutions can show thixotropy (defined as a time dependent property of structured fluids that exhibit a decrease in viscosity under flow, but there is a subsequent structural recovery once that the flow has been stopped) [19], yield-stress [20] and shear-banding [21,22].

2. Thixotropic Models

- Spontaneous Viscosity Build-Up (or Structural Reformation): This first process initiates when the structural parameter surpasses its minimum threshold, indicating a fully structured state. Importantly, the reformation is presumed to be independent of the rate at which shear work is exerted on the material. Instead, it relies on a material-specific characteristic time, which determines the pace of structural recovery for viscosity.

- Viscosity Breakdown (or Structural Destruction): In contrast to reformation, the breakdown of viscosity (second process) is directly influenced by the amount of shear work applied to the material. This process occurs when the structural parameter falls below its maximum value, signifying a completely unstructured state.

- the first one is the reformation process (build up of viscosity or breakdown of fluidity), where is known as the structural relaxation time (units of ) and is the inverse of the zero-shear-rate viscosity, the fluidity plateau, and represents the fully structured state of the microstructure;

- the second term is the destruction process (breakdown of viscosity or build up of fluidity), where is a parameter related to structure breaking down (units of ), the term is the rate of energy dissipation of the fluid and is the experimentally observed fluidity at high shear rates, and represents the completely unstructured state of the fluid.

3. Governing Equations and Numerical Method

3.1. Numerical method

3.2. The exponential-PTT model

3.3. The RheoTool software

3.4. Overview of the numerical method

- Initialise the fields for pressure p, velocity , fluidity (for the EPTT mode, ), log-conformation and polymeric stress tensors at time and set boundary conditions.

-

Enter the time loop ().

- (a)

-

Enter the inner iterations loop ().

- Compute the conformation tensor (Equation (19)) and their respective eigenvalues and eigenvectors and apply the log-conformation transformation approach to obtain the tensor .

- Solve the evolution of the log-conformation tensor Equation (24) to obtain .

- Solve the momentum equations for the velocity field that does not satisfy the continuity equation.

- Solve the Poisson equation for the pressure field and calculate the corrected velocity field ( and ).

- Increment the inner iteration index () and return to step i until the predefined number of inner iterations is reached.

- Update all the fields to be used in the next time loop: .

- (b)

- Increment the time and return to step 2 until the final time is reached.

- Stop the simulation and exit.

4. Results

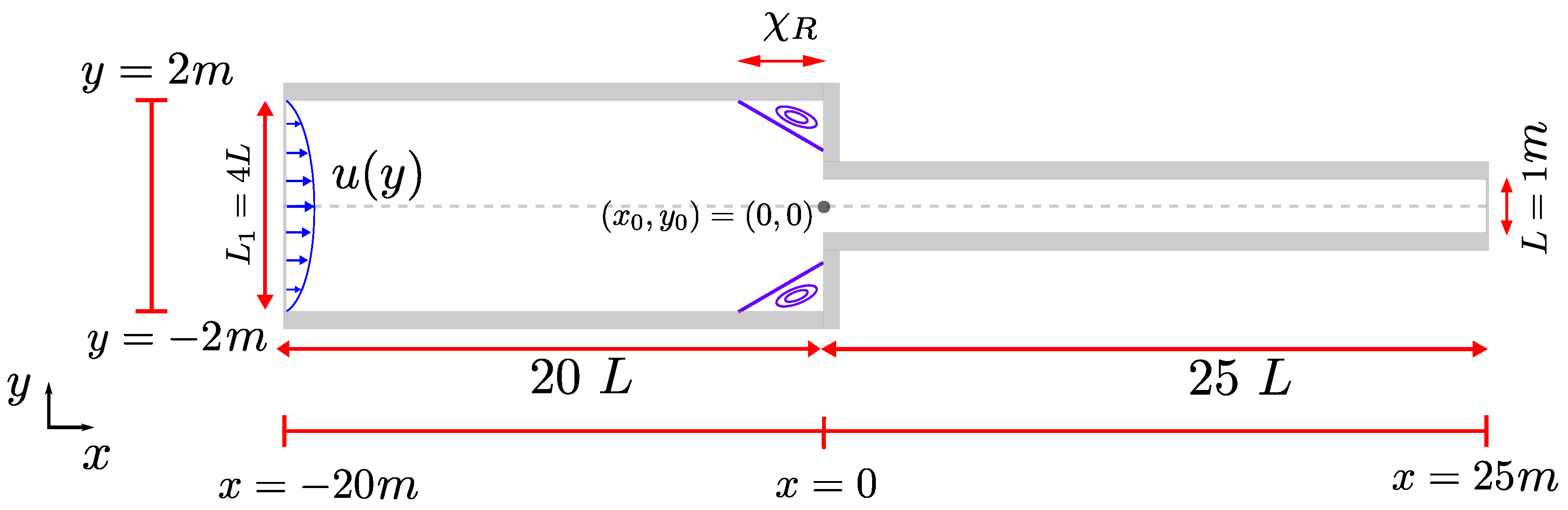

4.1. The planar 4:1 contraction flow

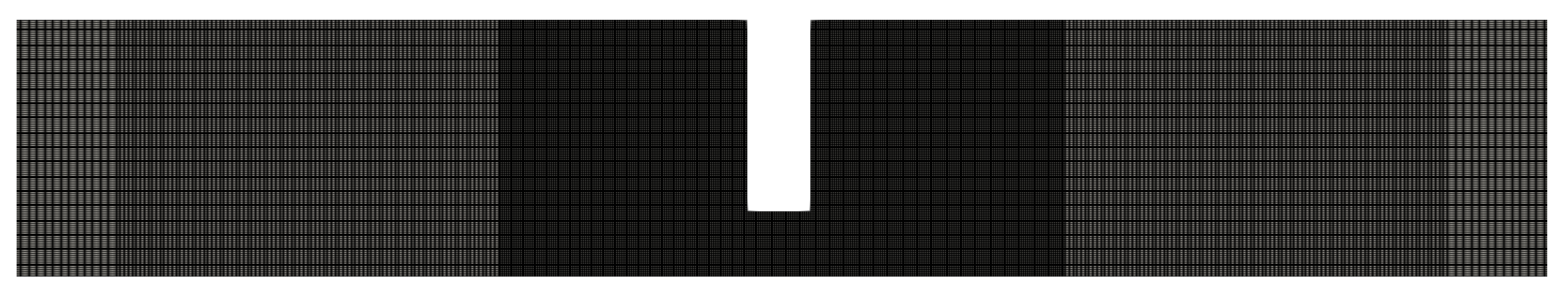

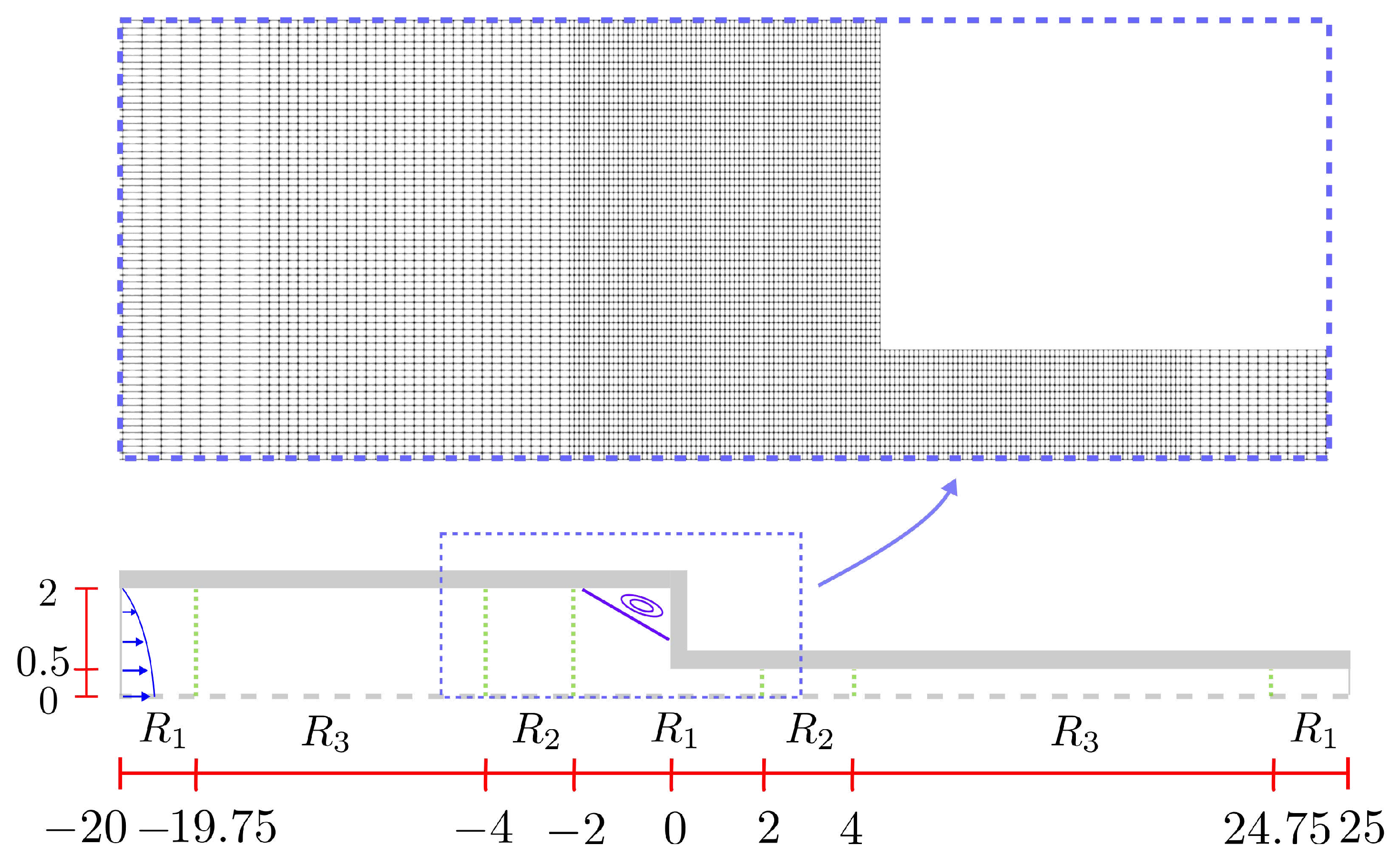

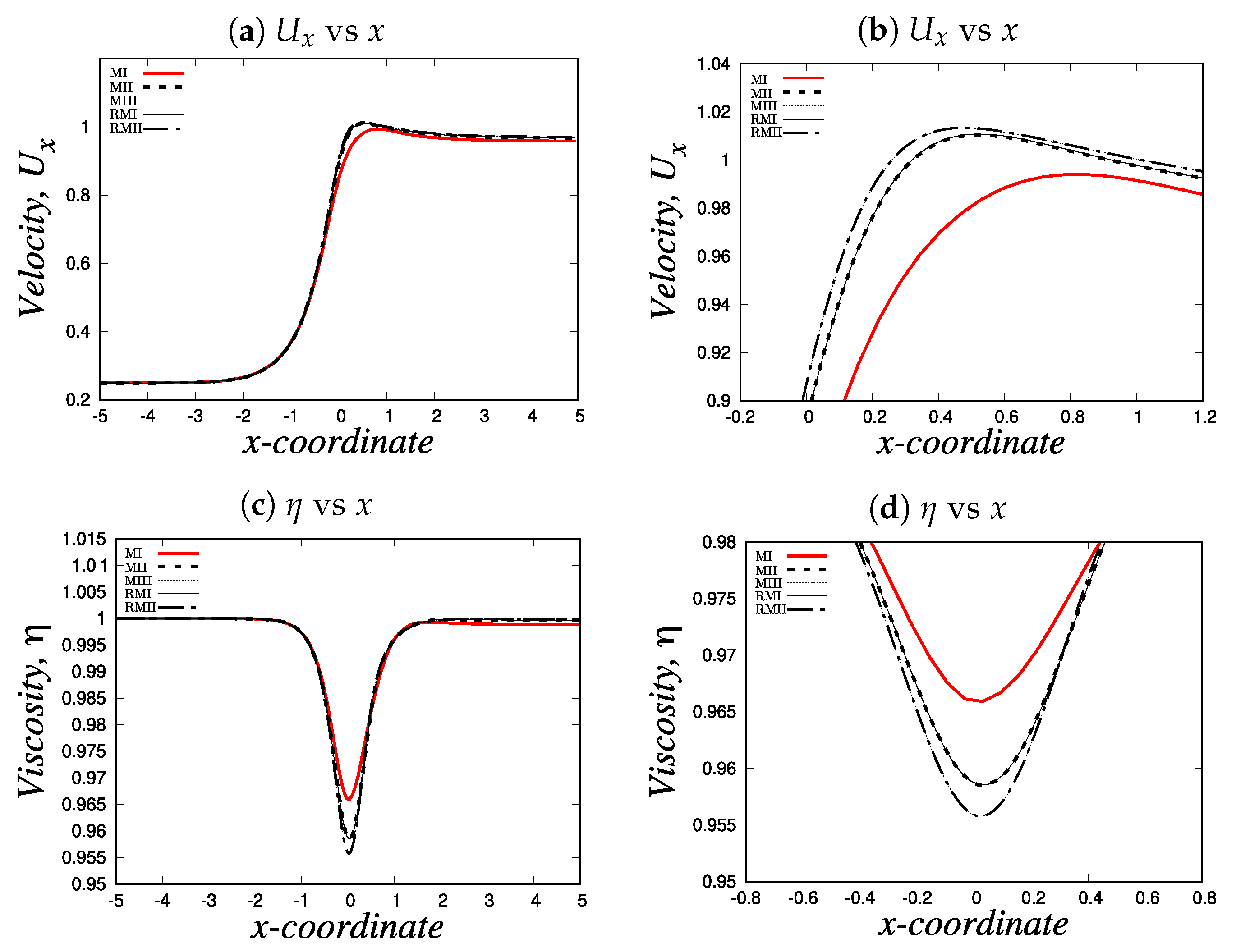

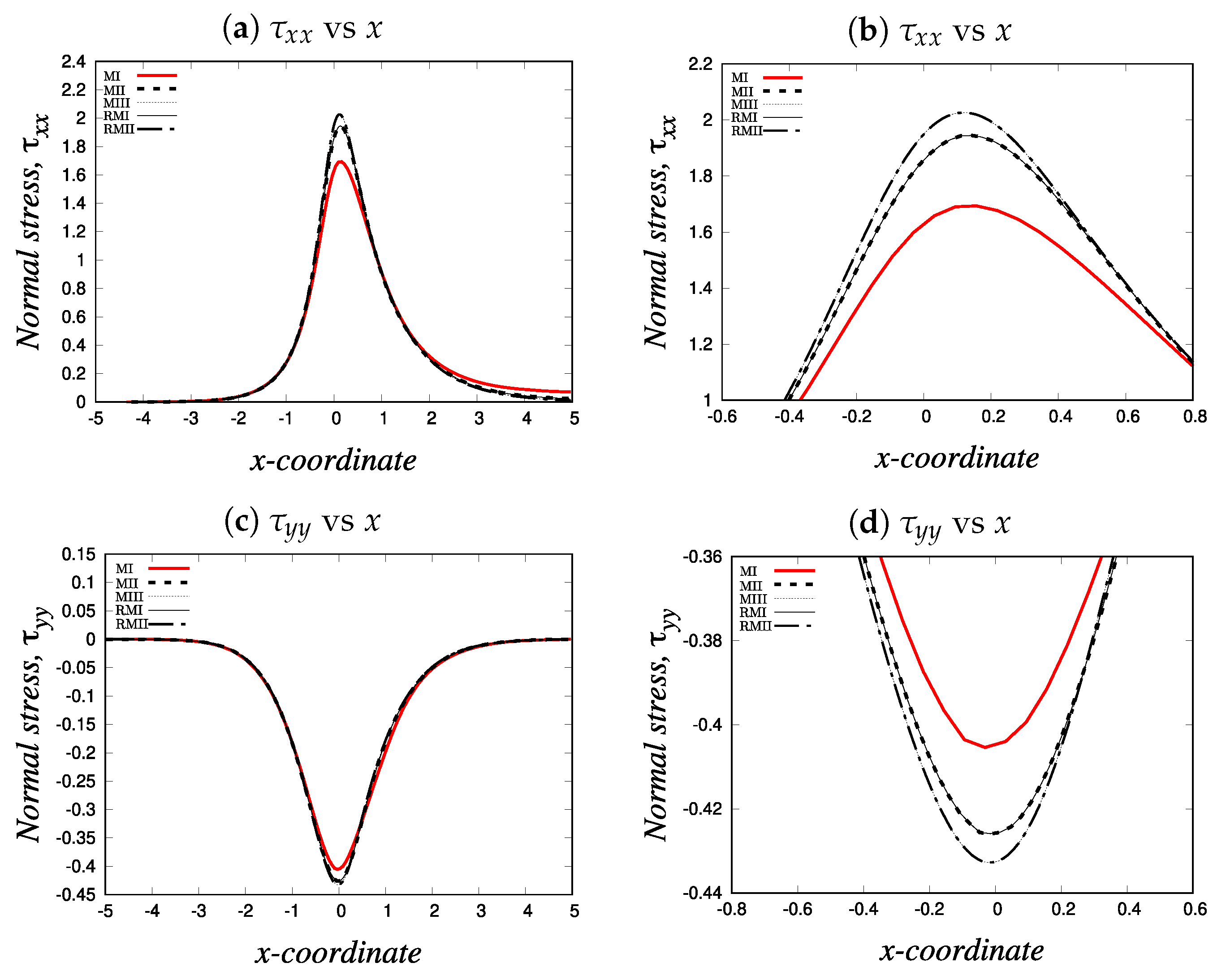

4.1.1. Mesh convergence analysis

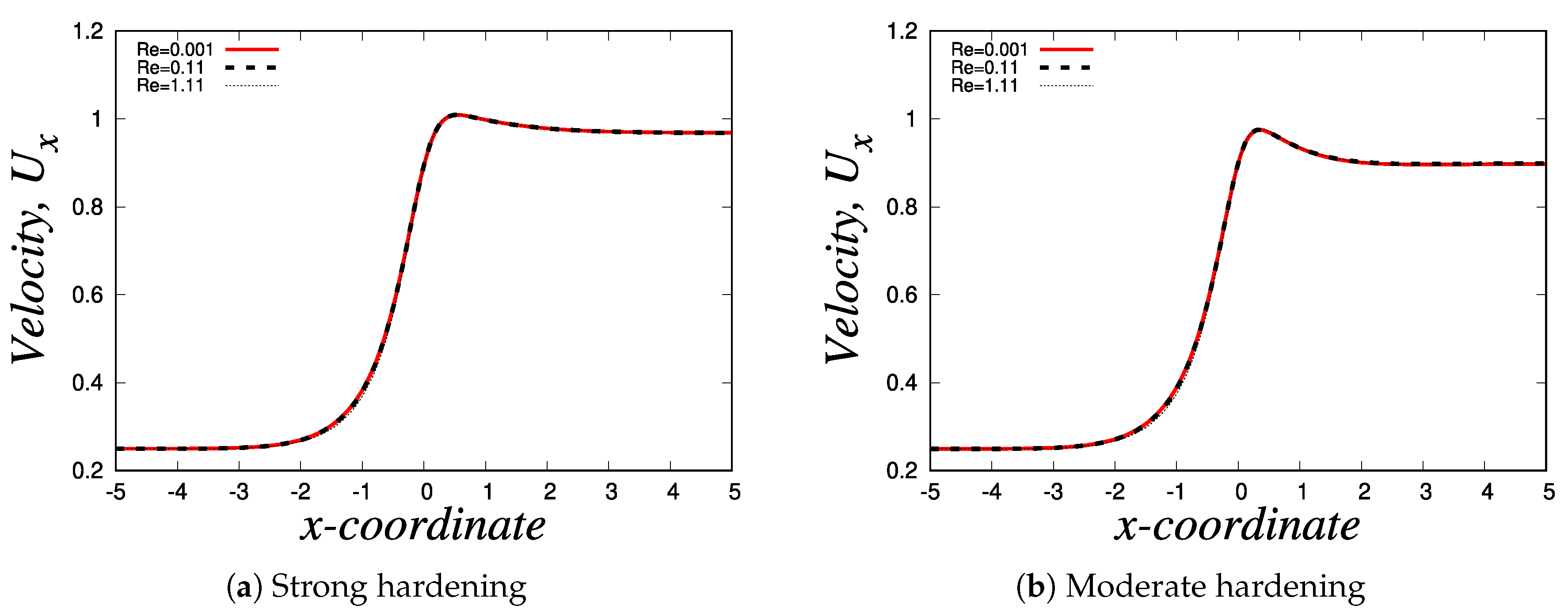

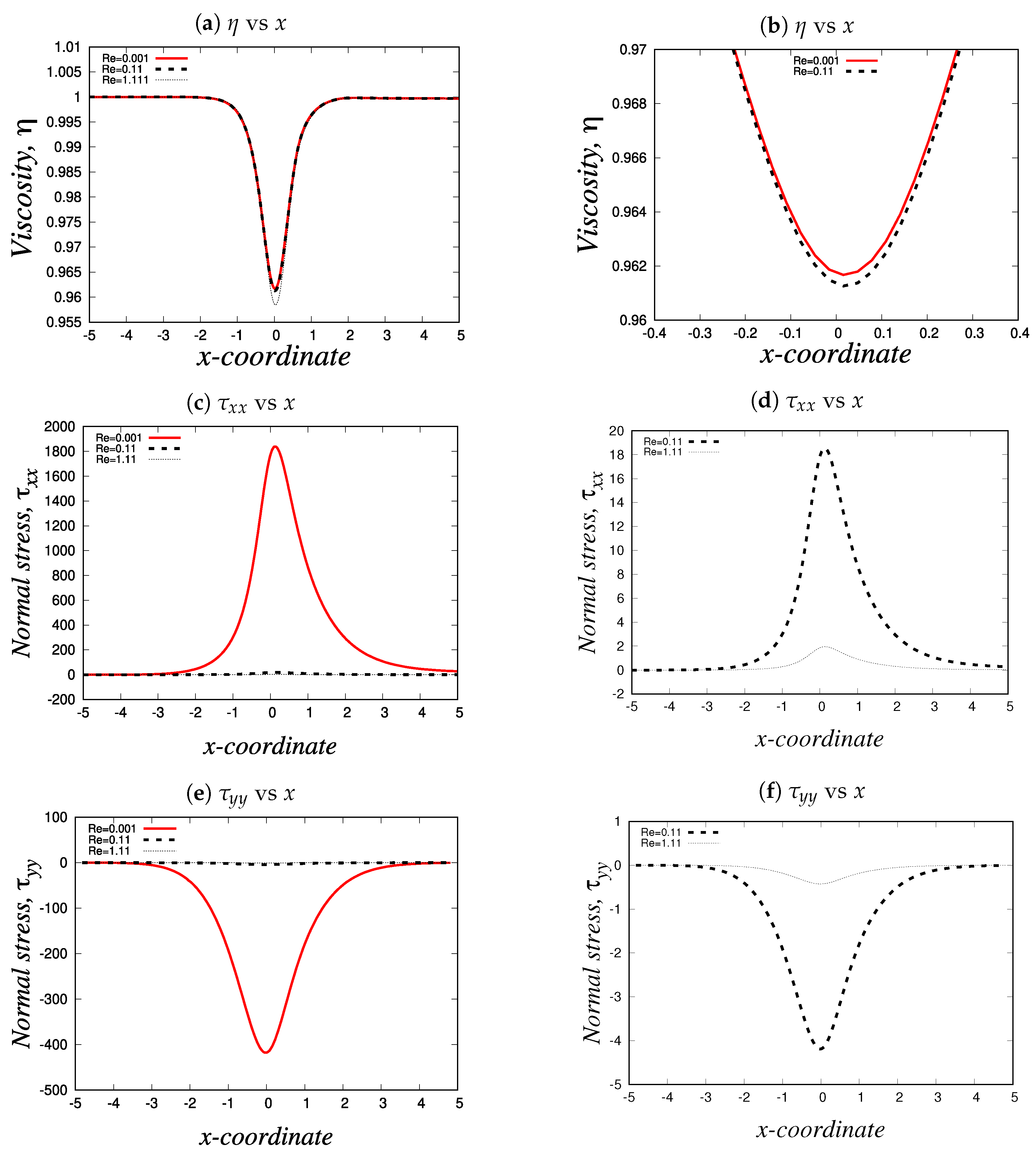

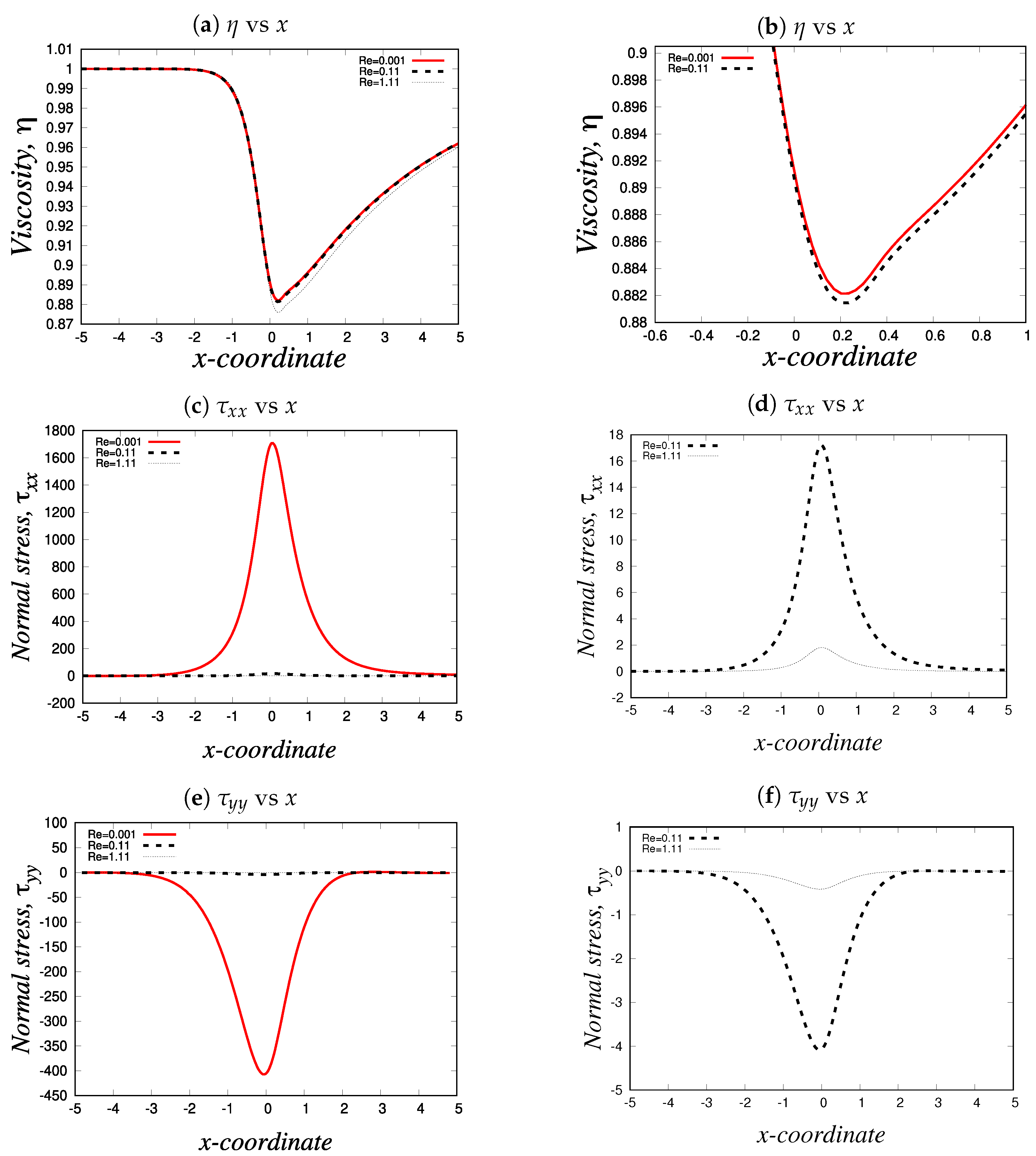

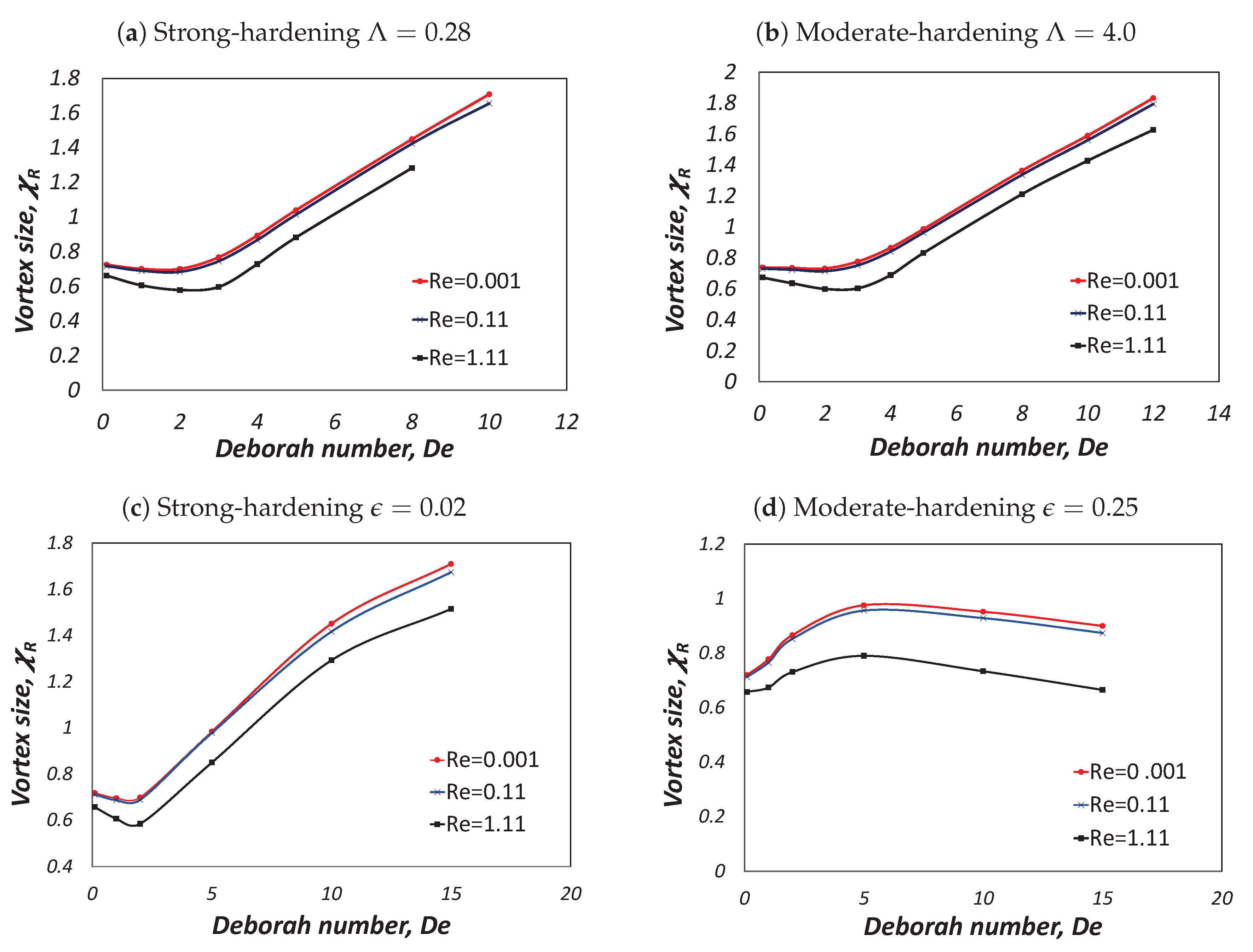

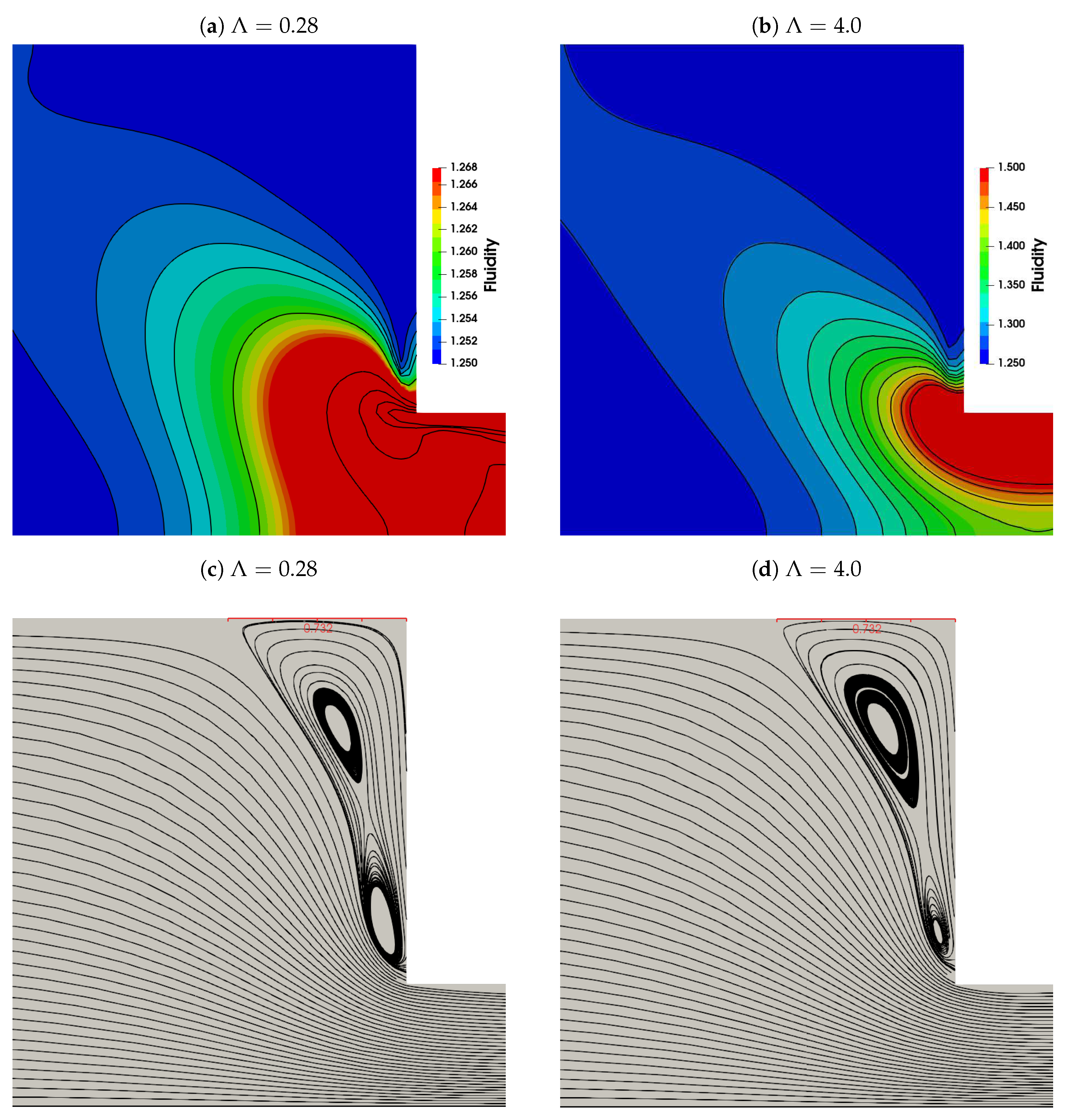

4.1.2. Strong-hardening and moderate-hardening behaviour

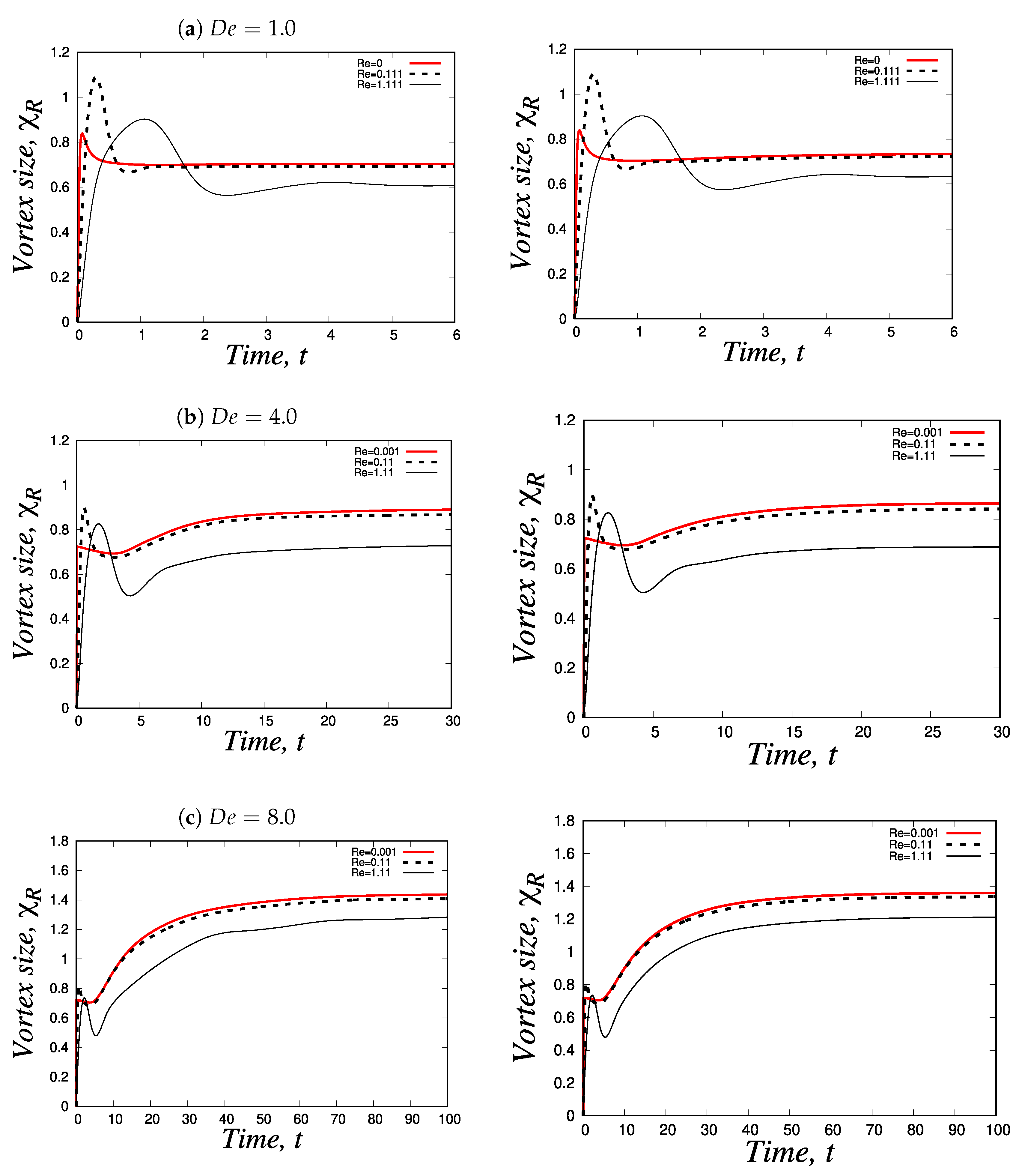

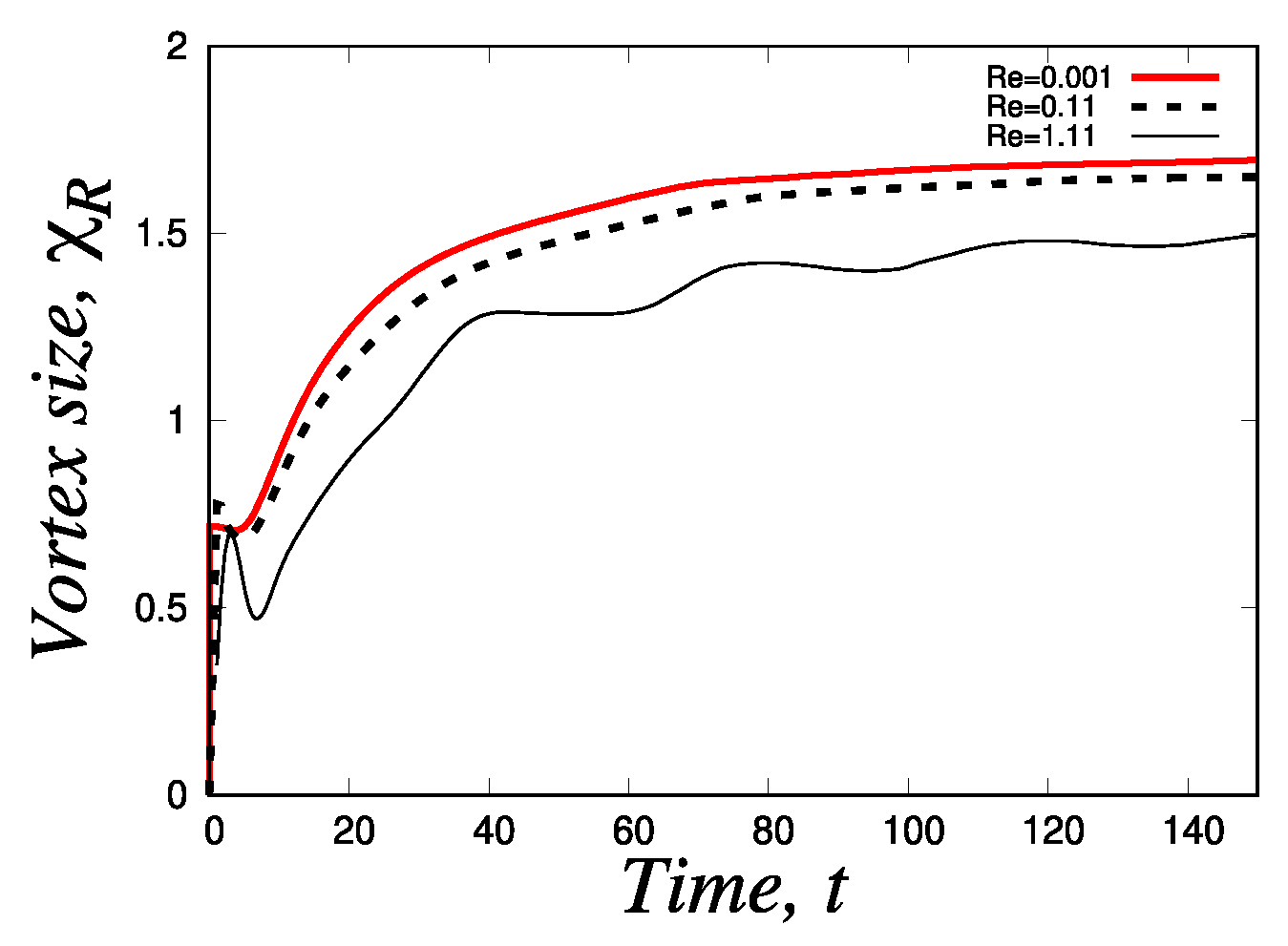

4.1.3. Corner vortex: transient and steady-state behaviour

4.1.4. Corner vortex size as a function of Mach, elasticity and thixoelastic numbers

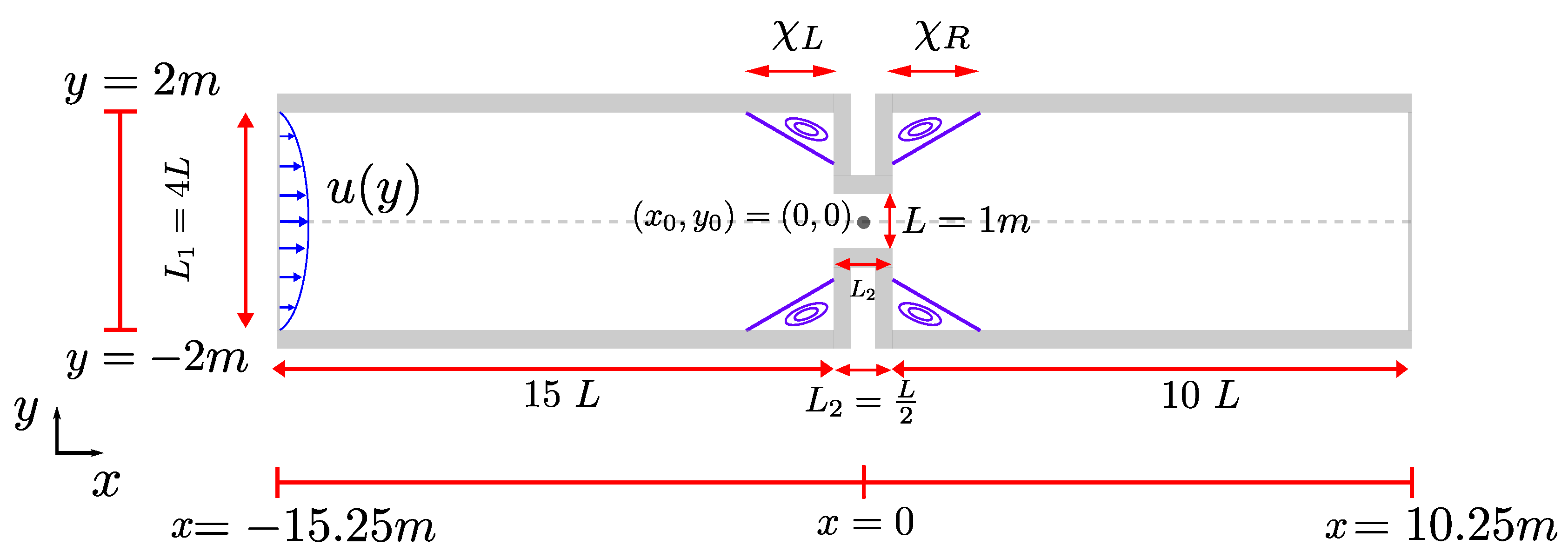

4.2. The planar 4:1:4 contraction-expansion flow

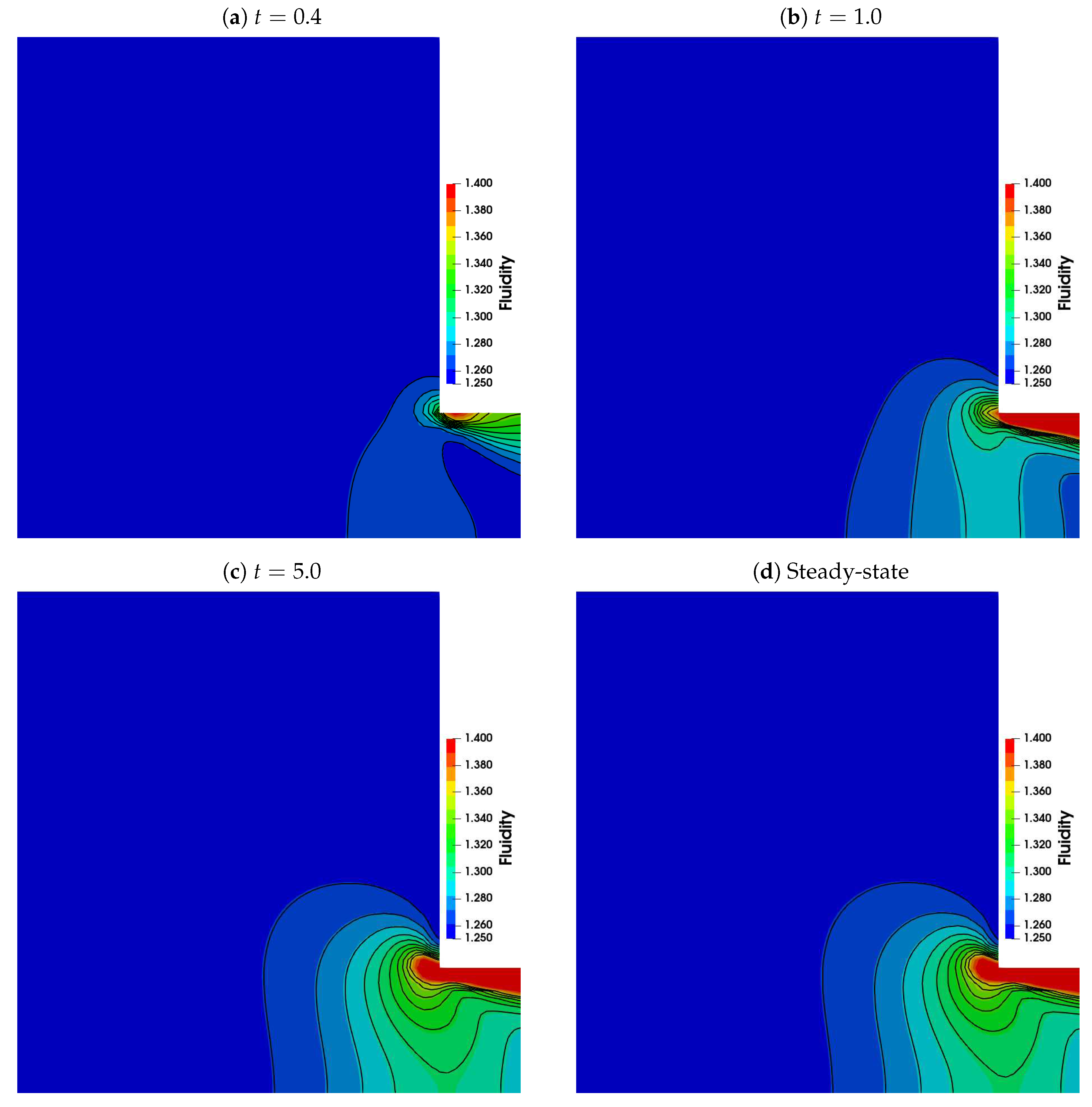

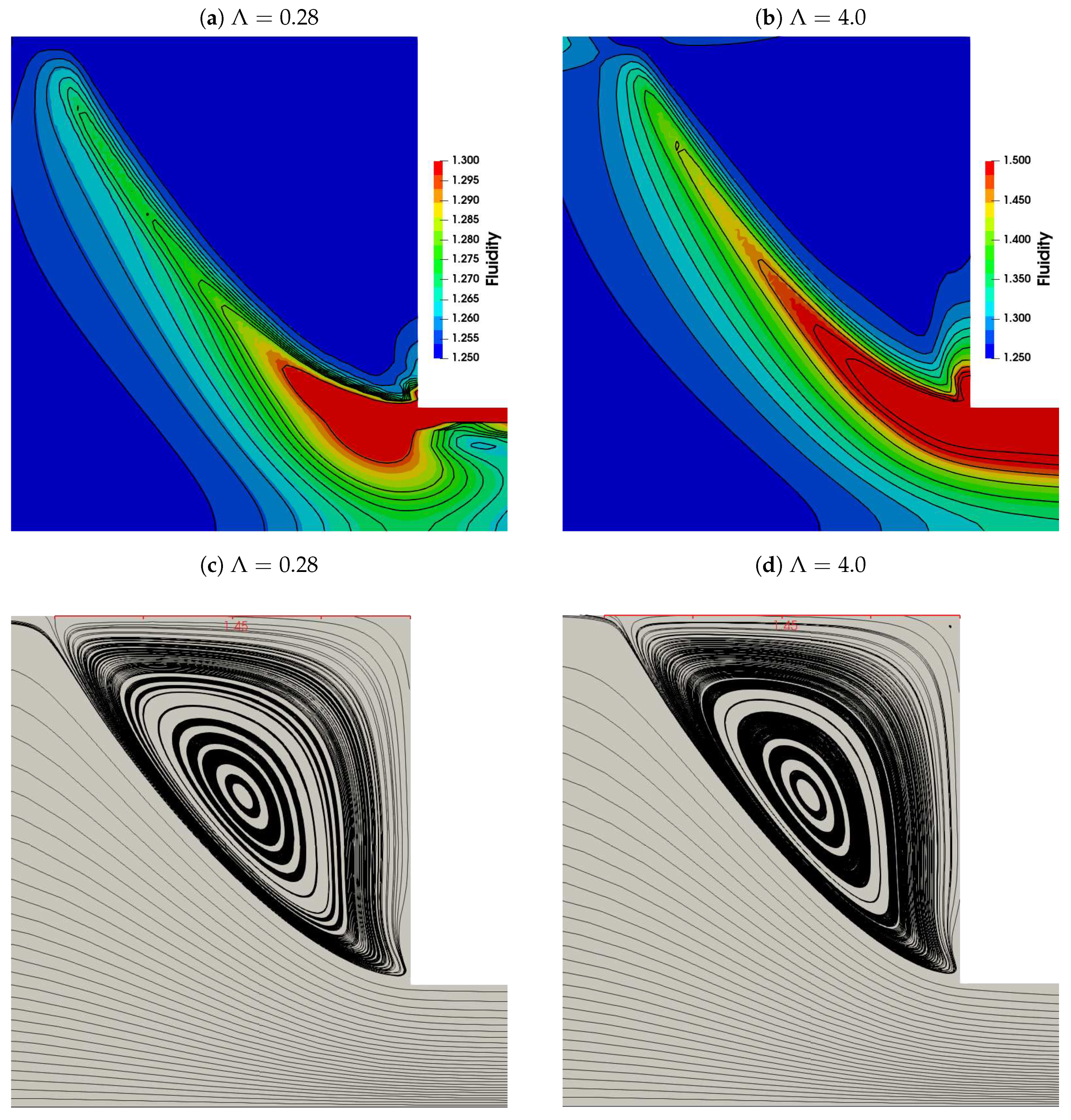

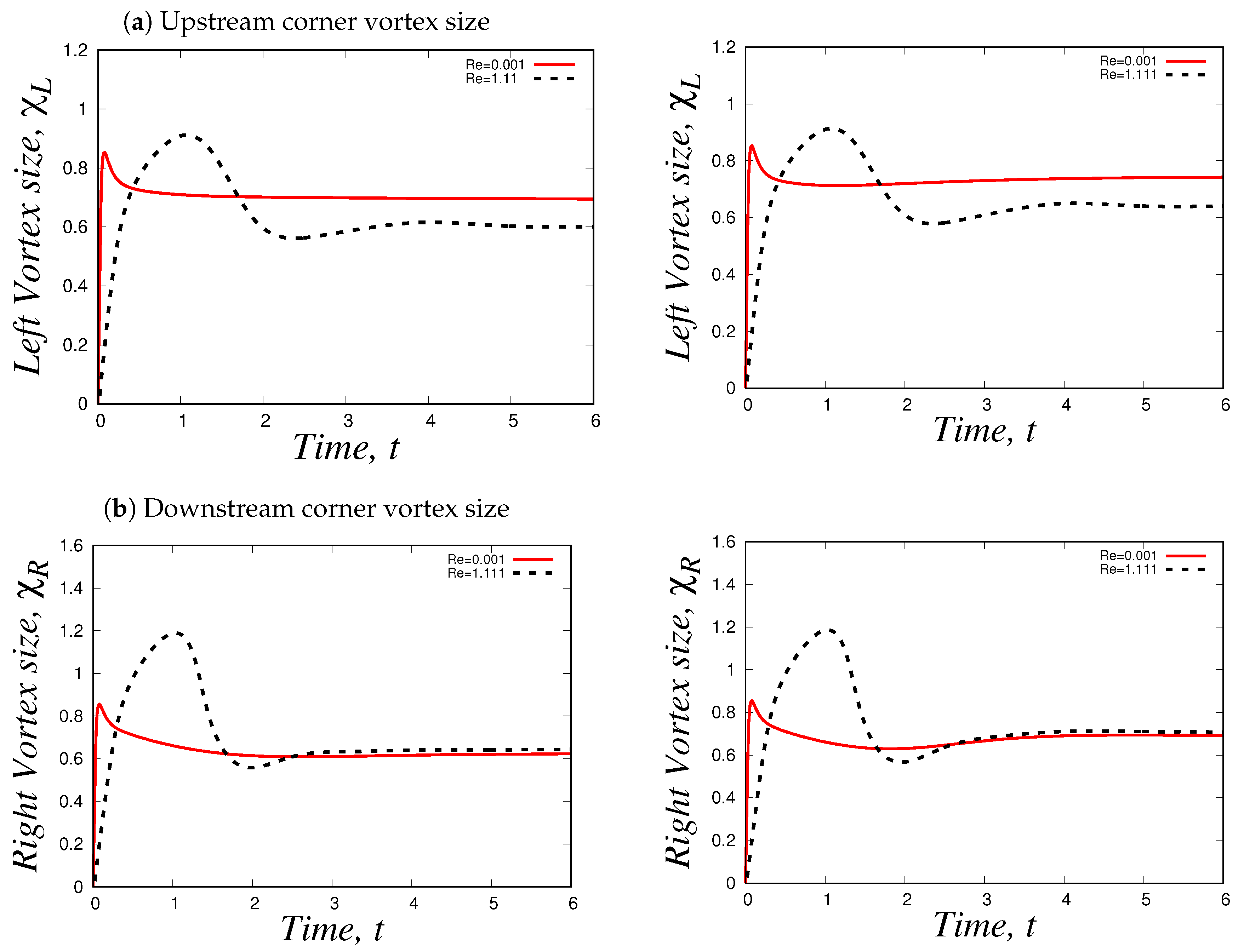

4.2.1. Vortex dynamics: transient and steady-state behaviour

5. Conclusions

- Strong-Hardening Case: This involves a fluid that exhibits rapid structural recovery, characterized by and a swift restoration of viscosity.

- Moderate-Hardening Case: In this case, we dealt with a fluid exhibiting slightly slower structural recovery, with .

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBM | Modified-Bautista-Manero |

| BMP | Bautista-Manero Puig |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| PTT | Phan-Tien-Tanner |

| EPTT | Exponential Phan-Tien-Tanner |

| UCM | Upper-Convected-Maxwell |

| GNF | Generalized Newtonian Fluids |

| FVM | Finite-Volume-Method |

| BSD | Both-sides-diffusion |

| iBSD | Improved Both-sides-diffusion |

| DILU | Simplified Diagonal-based Incomplete LU preconditioner |

| PETSc | Portable, Extensible Toolkik for Scientific Computation |

| PCG | Conjugated Preconditioned Gradients |

| Bi-CGSTAB | Bi-Conjugate Gradient Stabilized |

| DIC | Diagonal-based Incomplete Cholesky |

| CUBISTA | Convergent and Universally Bounded Interpolation Scheme for the Treatment of Advection |

References

- White, J.L.; Metzner, A.B. Development of constitutive equations for polymeric melts and solutions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 1963, 7, 1867–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldroyd, J.G.; Wilson, A.H. On the formulation of rheological equations of state. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1950, 200, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, N.P.; Tanner, R.I. A new constitutive equation derived from network theory. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 1977, 2, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesekus, H. Die Elastizität von Flüssigkeiten. Rheologica Acta 1966, 5, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Volume 1: Fluid Mechanics; Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Wiley, 1987.

- Alves, M.; Oliveira, P.; Pinho, F. Numerical Methods for Viscoelastic Fluid Flows. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2021, 53, 509–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilata, B.; Clasen, C.; McKinley, G. Nonlinear shear and extensional flow dynamics of wormlike surfactant solutions. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2006, 133, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Faroughi, S.A.; Carneiro, O.S.; Nóbrega, J.M.; McKinley, G.H. Fully-resolved simulations of particle-laden viscoelastic fluids using an immersed boundary method. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2019, 266, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Faroughi, S.A.; Ribeiro, R.; Isabel, A.; McKinley, G.H. Finite volume simulations of particle-laden viscoelastic fluid flows: application to hydraulic fracture processes. Engineering with Computers 2022, 38, 5395–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Miyauchi, T.E.; Firoozabadi, A.; Fuller, G.G. Nonmonotonic Elasticity of the Crude Oil–Brine Interface in Relation to Improved Oil Recovery. Langmuir 2016, 32, 2192–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodoushan, E.J.; Yi, T.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, N. Wormlike Micellar Solutions, Beyond the Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery Restrictions. Fluids 2019, 4, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigaard, I.A.; Paso, K.G.; de Souza Mendes, P.R. Bingham’s model in the oil and gas industry. Rheologica Acta 2017, 56, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J. Water-based chemicals and technology for drilling, completion, and workover fluids; Gulf Professional Publishing, 2015.

- Spagnolie, S.E. Complex fluids in biological systems: experiment, theory, and computation; Vol. 6, Springer, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.; Calderas, F.; Sanchez-Olivares, G.; Medina-Torres, L.; Sanchez-Solis, A.; Manero, O. Effect of cholesterol and triglycerides levels on the rheological behavior of human blood. Korea-Australia Rheology Journal 2015, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, C.; Franco, J.M. Rheology of food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 1999, 4, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, R.R. Applied rheology in the protective and decorative coatings industry. Rheology Reviews 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.G. The structure and rheology of complex fluids; Topics in Chemical Engineering, Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Bautista, F.; De Santos, J.M.; Puig, J.E.; Manero, O. Understanding thixotropic and antithixotropic behavior of viscoelastic micellar solutions and liquid crystalline dispersions. I. The model. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 1999, 80, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderas, F.; Herrera-Valencia, E.E.; Sanchez-Solis, A.; Manero, O.; Medina-Torres, L.; Renteria, A.; Sanchez-Olivares, G. On the yield stress of complex materials. Korea-Australia Rheology Journal 2013, 25, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, F.; Soltero, J.F.A.; Pérez-López, J.H.; Puig, J.E.; Manero, O. On the shear banding flow of elongated micellar solutions. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2000, 94, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, P.A.; McKinley, G.H.; Cook, L.P. A network scission model for wormlike micellar solutions: I. Model formulation and viscometric flow predictions. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2007, 144, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boek, E.S.; Padding, J.T.; Anderson, V.J.; Tardy, P.M.J.; Crawshaw, J.P.; Pearson, J.R.A. Constitutive equations for extensional flow of wormlike micelles: stability analysis of the Bautista–Manero model. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2005, 126, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, F.; Alves, M.A. RheoTool. https://github.com/fppimenta/rheoTool, 2017.

- Tamaddon Jahromi, H.R.; Webster, M.F.; Aguayo, J.P.; Manero, O. Numerical investigation of transient contraction flows for worm-like micellar systems using Bautista–Manero models. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2011, 166, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Aguilar, J.E.; Webster, M.F.; Tamaddon-Jahromi, H.R.; Manero, O. A new constitutive model for worm-like micellar systems – Numerical simulation of confined contraction–expansion flows. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2014, 204, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Aguilar, J.E.; Webster, M.F.; Tamaddon-Jahromi, H.R.; Manero, O. High-Weissenberg predictions for micellar fluids in contraction–expansion flows. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2015, 222, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Sánchez, H.A.; Bertoco, J.; de Araújo, M.S.; Castelo, A. Numerical simulation of thixotropic–viscoelastic models for structured fluids in hierarchical grids. Computers & Fluids 2023, 266, 106045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, A.; Afonso, A.M.; De Souza Bezerra, W. A Hierarchical Grid Solver for Simulation of Flows of Complex Fluids. Polymers 2021, 13, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.S.; Lages, C.F.; Ansoni, J.L.; Castelo, A.; Simao, A. A finite difference method with meshless interpolation for incompressible flows in non-graded tree-based grids. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 396, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, A.G. A model for the thixotropy of suspensions. AIChe Journal 1970, 16, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, H.A.; Wilson, H.J. Elastic instabilities in pressure-driven channel flow of thixotropic-viscoelasto-plastic fluids. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2018, 261, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, F.; Alves, M.A. Stabilization of an open-source finite-volume solver for viscoelastic fluid flows. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2017, 239, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattal, R.; Kupferman, R. Constitutive laws for the matrix-logarithm of the conformation tensor. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2004, 123, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.; Oliveira, P.J.; Pinho, F.T.; Alves, M.A. The log-conformation tensor approach in the finite-volume method framework. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2009, 157, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrás, L.L.; Morgado, M.L.; Rebelo, M.; McKinley, G.H.; Afonso, A. A generalised Phan–Thien—Tanner model. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2019, 269, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Thien, N. A Nonlinear Network Viscoelastic Model. Journal of Rheology 1978, 22, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhie, C.M.; Chow, W.L. Numerical study of turbulent flow past an isolated airfol with trailing edge separation. AIAA Journal 1983, 21, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Araújo, M.S.B.; Ferrás, L.L.; Miguel Nóbrega, J. Improved both sides diffusion (iBSD): A new and straightforward stabilization approach for viscoelastic fluid flows. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2017, 249, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PETSc. Portable, Extensible Toolkit for Scientific Computation, 1991. https://petsc.org/release/.

- Alves, M.A.; Oliveira, P.J.; Pinho, F.T. A convergent and universally bounded interpolation scheme for the treatment of advection. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2003, 41, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFOAM Foundation, OpenFOAM v8 User Guide, 2020. https://cfd.direct/openfoam/user-guide.

- van der Vorst, H.A. Bi-CGSTAB: A Fast and Smoothly Converging Variant of Bi-CG for the Simulation of Nonsymmetric Linear Systems. SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing 1992, 13, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D. Preconditioned conjugate gradient methods for solving systems of algebraic equations. Technical Report RD/L/N193/80, Central Electricity Research Laboratories, 1980.

- Owens, R.G.; Phillips, T.N. Computational rheology; World Scientific, 2002.

- Choi, H.C.; Song, J.H.; Yoo, J.Y. Numerical simulation of the planar contraction flow of a Giesekus fluid. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 1988, 29, 347–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Aguilar, J.E.; Webster, M.F.; Tamaddon-Jahromi, H.R.; Manero, O. Convoluted models and high-Weissenberg predictions for micellar thixotropic fluids in contraction–expansion flows. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2016, 232, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MI | |||

| MII | |||

| RMI | |||

| RMII |

| Parameters | Strong-hardening | Moderate hardening |

|---|---|---|

| (m/s) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| L (m) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| (s) | 0.28 | 4.0 |

| 0.11 | 0.11 | |

| 0.28 | 4.0 | |

| 0.1125 | 0.1125 |

| Vortex size | M | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.28 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.7243 | 0.0105 | 90.0901 | 0.3571 |

| 1.0 | 0.7009 | 0.0333 | 900.9001 | 3.5714 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.7007 | 0.0471 | 1801.8018 | 7.1428 | ||

| 3.0 | 0.7676 | 0.0577 | 2702.7027 | 10.7143 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.8930 | 0.0666 | 3603.6036 | 14.2857 | ||

| 5.0 | 1.0392 | 0.0745 | 4504.5045 | 17.8571 | ||

| 8.0 | 1.4487 | 0.0942 | 7207.2072 | 28.5714 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.7085 | 0.1054 | 9009.0090 | 35.7143 | ||

| 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.7176 | 0.1053 | 0.9009 | 0.3571 | |

| 1.0 | 0.6902 | 0.3332 | 9.0090 | 3.5714 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.6839 | 0.4712 | 18.0180 | 7.1428 | ||

| 3.0 | 0.7472 | 0.5771 | 27.0270 | 10.7143 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.8673 | 0.6663 | 36.0360 | 14.2857 | ||

| 5.0 | 1.0132 | 0.7450 | 45.0450 | 17.8571 | ||

| 8.0 | 1.4106 | 0.9423 | 72.0720 | 28.5714 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.6553 | 1.0534 | 90.0900 | 35.7143 | ||

| 1.11 | 0.1 | 0.6621 | 0.3333 | 0.0901 | 0.3571 | |

| 1.0 | 0.6060 | 1.0540 | 0.9001 | 3.5714 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.5790 | 1.4906 | 1.8002 | 7.1428 | ||

| 3.0 | 0.5963 | 1.8256 | 2.7003 | 10.7143 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.7281 | 2.1081 | 3.6003 | 14.2857 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.8818 | 2.3569 | 4.5045 | 17.8571 | ||

| 8.0 | 1.2827 | 2.9813 | 7.2007 | 28.5714 | ||

| 10.0 | (1.4871) | 3.3332 | 9.0009 | 35.7143 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.7383 | 0.0105 | 90.0901 | 0.025 |

| 1.0 | 0.7352 | 0.0333 | 900.9009 | 0.25 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.7317 | 0.0471 | 1801.8018 | 0.5 | ||

| 3.0 | 0.7760 | 0.0577 | 2702.7027 | 0.75 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.8650 | 0.0666 | 3603.6036 | 1.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.9860 | 0.07450 | 4504.5045 | 1.25 | ||

| 8.0 | 1.3632 | 0.09423 | 7207.2072 | 2.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.5899 | 0.1054 | 9009.0090 | 2.5 | ||

| 12.0 | 1.8324 | 0.1154 | 10810.8108 | 3.0 | ||

| 14.0 | 2.0537 | 0.1247 | 12612.61 | 3.5 | ||

| 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.7309 | 0.1054 | 0.9009 | 0.025 | |

| 1.0 | 0.7239 | 0.3317 | 9.0090 | 0.25 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.7142 | 0.4712 | 18.0180 | 0.5 | ||

| 3.0 | 0.7521 | 0.5771 | 27.0270 | 0.75 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.8415 | 0.6663 | 36.0360 | 1.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.9634 | 0.7450 | 45.0450 | 1.25 | ||

| 8.0 | 1.3364 | 0.9423 | 72.0720 | 2.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.5582 | 1.0536 | 90.0901 | 2.5 | ||

| 12.0 | 1.7812 | 1.1541 | 108.1081 | 3.0 | ||

| 1.11 | 0.1 | 0.6730 | 0.3333 | 0.0901 | 0.025 | |

| 1.0 | 0.6363 | 1.0540 | 0.9001 | 0.25 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.5997 | 1.4906 | 1.8002 | 0.5 | ||

| 3.0 | 0.6033 | 1.8257 | 2.7002 | 0.75 | ||

| 4.0 | 0.6887 | 2.1081 | 3.6004 | 1.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.8314 | 2.3569 | 4.5045 | 1.25 | ||

| 8.0 | 1.2116 | 2.9813 | 7.2007 | 2.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.4278 | 3.3332 | 9.0009 | 2.5 | ||

| 12.0 | 1.6274 | 3.6513 | 10.8010 | 3.0 |

| Vortex size | M | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.7172 | 0.0105 | 90.0901 | 5.0 |

| 1.0 | 0.6955 | 0.0333 | 900.9009 | 50.0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.6984 | 0.0471 | 1801.8018 | 100.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.9919 | 0.0745 | 4504.5045 | 250.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.4520 | 0.1054 | 9009.0090 | 500.0 | ||

| 15.0 | 1.7112 | 0.1290 | 13513.5135 | 750.0 | ||

| 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.7105 | 0.1053 | 0.9009 | 5.0 | |

| 1.0 | 0.6859 | 0.3332 | 9.0090 | 50.0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.6876 | 0.4712 | 18.0180 | 100.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.9777 | 0.7450 | 45.0450 | 250.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.4165 | 1.0536 | 90.0900 | 500.0 | ||

| 15.0 | 1.6740 | 1.2903 | 135.1351 | 750.0 | ||

| 1.11 | 0.1 | 0.6558 | 0.3333 | 0.0901 | 5.0 | |

| 1.0 | 0.6063 | 1.0540 | 0.9001 | 50.0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.5838 | 1.4906 | 1.8002 | 100.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.8493 | 2.3569 | 4.5045 | 250.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.2921 | 3.3331 | 9.0009 | 500.0 | ||

| 15.0 | 1.5145 | 4.0823 | 13.5014 | 750.0 | ||

| 0.25 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.7191 | 0.0105 | 90.0901 | 0.4 |

| 1.0 | 0.7771 | 0.0333 | 900.9009 | 4.0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.8657 | 0.0471 | 1801.8018 | 8.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.9757 | 0.0745 | 4504.5045 | 20.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 0.9517 | 0.1054 | 9009.0090 | 40.0 | ||

| 15.0 | 0.8997 | 0.1290 | 13513.5135 | 60.0 | ||

| 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.7124 | 0.1054 | 0.9009 | 0.4 | |

| 1.0 | 0.7655 | 0.3317 | 9.0090 | 4.0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.8523 | 0.4712 | 18.0180 | 8.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.9560 | 0.7450 | 45.0450 | 20.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 0.9282 | 1.0536 | 90.0900 | 40.0 | ||

| 15.0 | 0.8739 | 1.2903 | 135.1351 | 60.0 | ||

| 1.11 | 0.1 | 0.6574 | 0.3333 | 0.0901 | 0.4 | |

| 1.0 | 0.6736 | 1.0540 | 0.9001 | 4.0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.7304 | 1.4906 | 1.8002 | 8.0 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.7899 | 2.3569 | 4.5045 | 20.0 | ||

| 10.0 | 0.7332 | 3.3331 | 9.0009 | 40.0 | ||

| 15.0 | 0.6648 | 4.0823 | 13.5014 | 60.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).