Submitted:

12 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Cells

2.2. DNA Isolation

2.3. Droplet Digital PCR

2.3. Spleen and Liver Tissues

2.4. Tests for PERV-C

2.5. Tests for Additional Porcine Viruses

3. Results

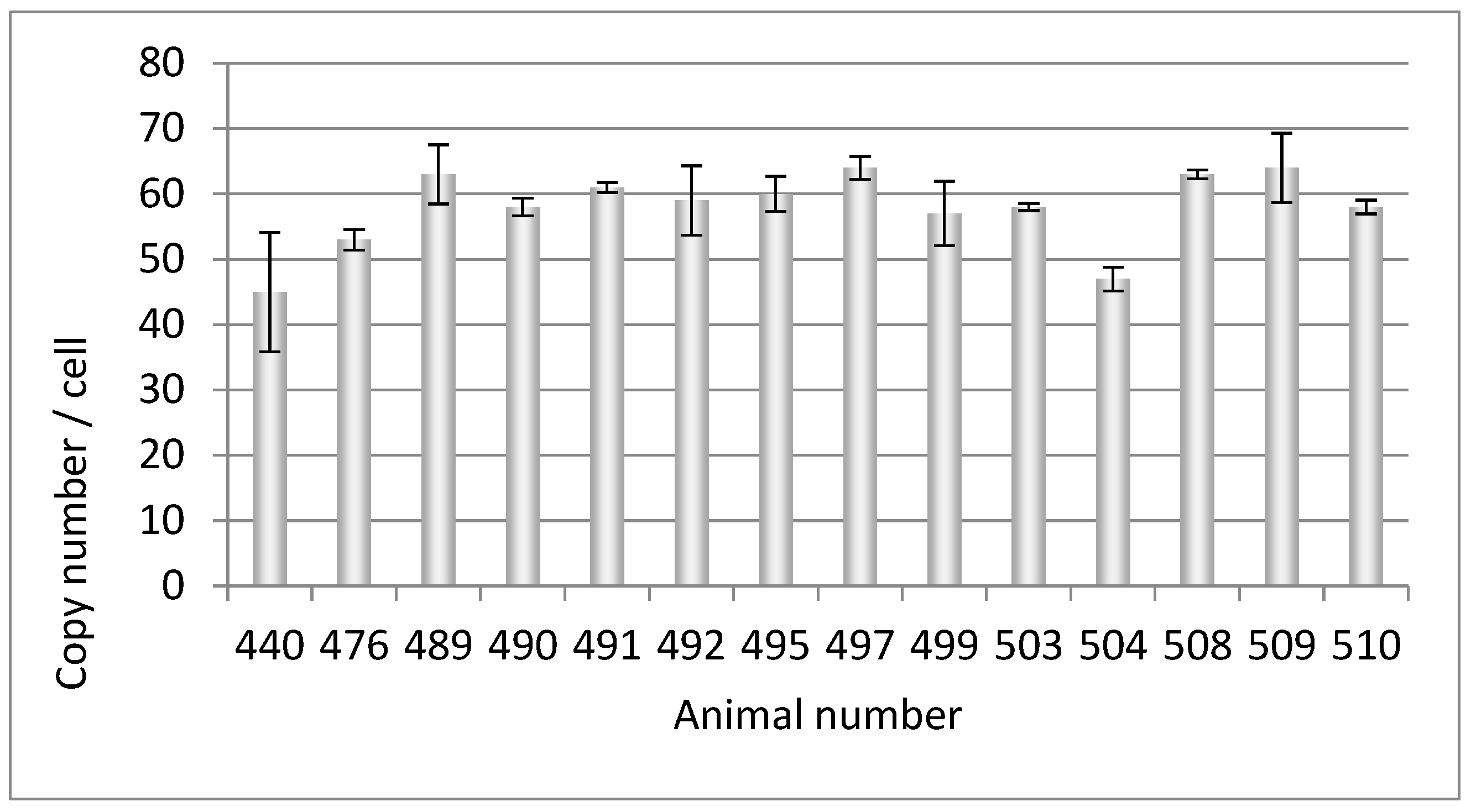

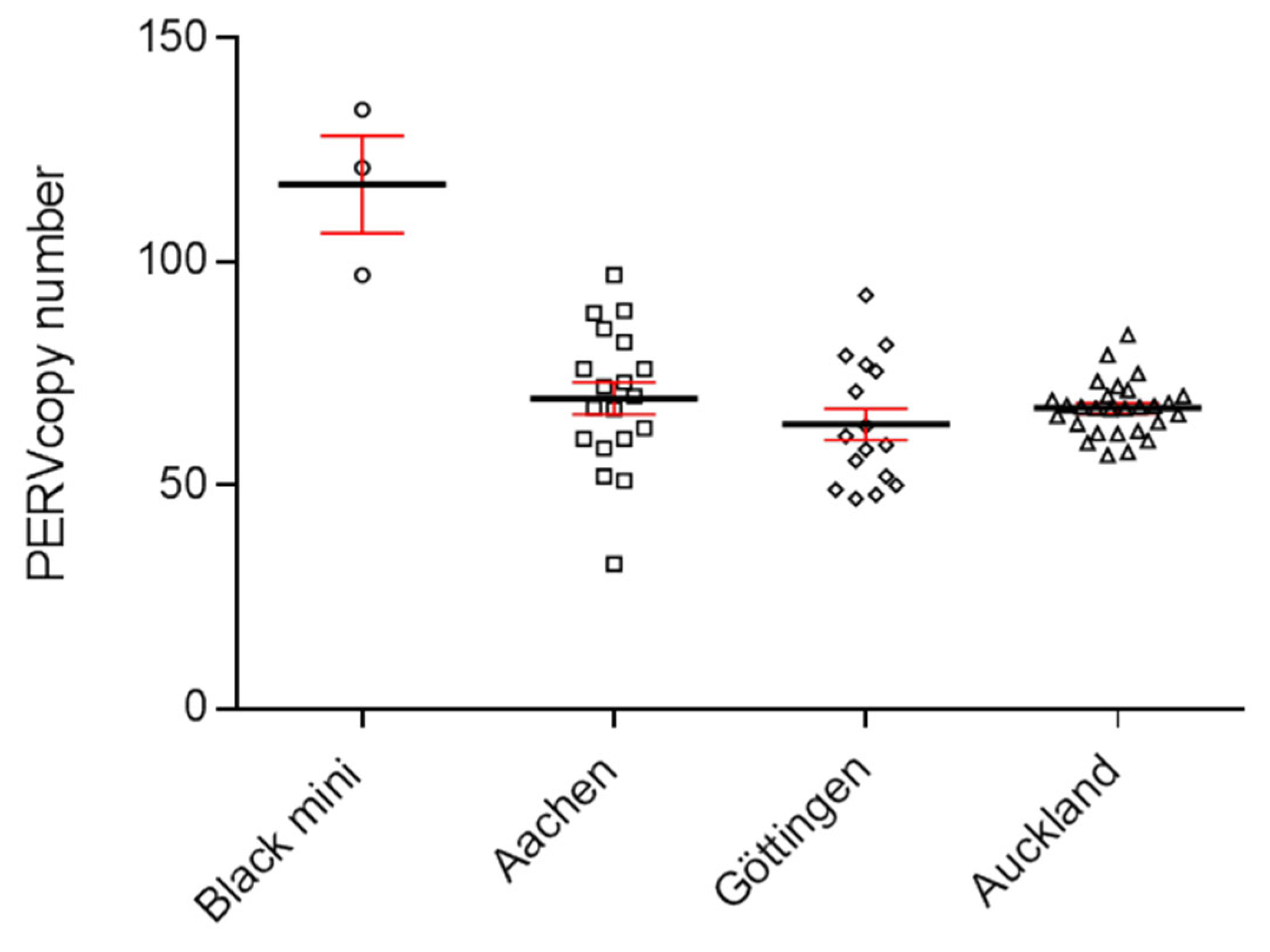

3.1. PERV Copy Number in the Genome of Adult Auckland Island Pigs

3.2. Selection of PERV-C Negative Animals

| Pig | PERV copy number |

PERV-C | PCMV | HEV | HEV | HEV | PCV1/2 | PCV3 | PLHV-1/2 | PLHV-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | PCR | PCR | WB | ELISA | PCR | PCR | PCR | PCR | ||

| 440 | 69 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 476 | 64 | - | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | + |

| 489 | 68 | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 490 | 75 | + | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | - |

| 491 | 68 | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 492 | 62 | + | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | - |

| 494 | 73 | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 495 | 66 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 497 | 69 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 499 | 62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 503 | 62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 504 | 57 | - | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | - |

| 508 | 64 | + | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | - |

| 509 | 67 | + | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | - |

| 510 | 60 | + | - | - | - | n.t. | - | - | - | |

| f1 | 21 | - | - | n.t. | n.a. | n.a. | n.t. | - | n.t. | n.t. |

| f2 | 20 | - | - | n.t. | n.a. | n.a. | n.t. | - | n.t. | n.t. |

| m1 | 20 | - | - | n.t. | n.a. | n.a. | n.t. | - | n.t. | n.t. |

| m2 | 22 | - | - | n.t. | n.a. | n.a. | n.t. | - | n.t. | n.t. |

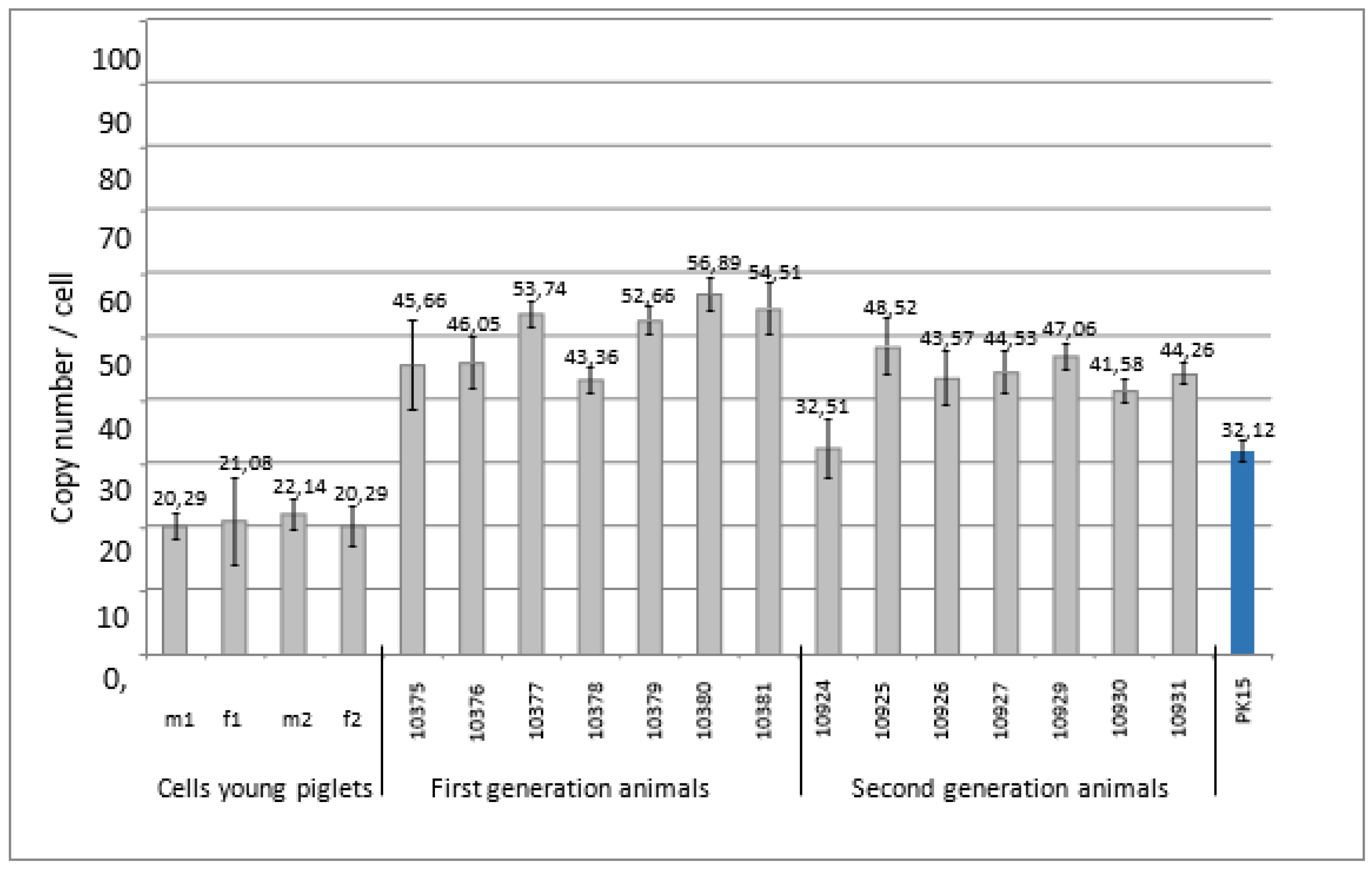

3.3. PERV Copy Number in the Genome of Cell Lines from Very Young Piglets

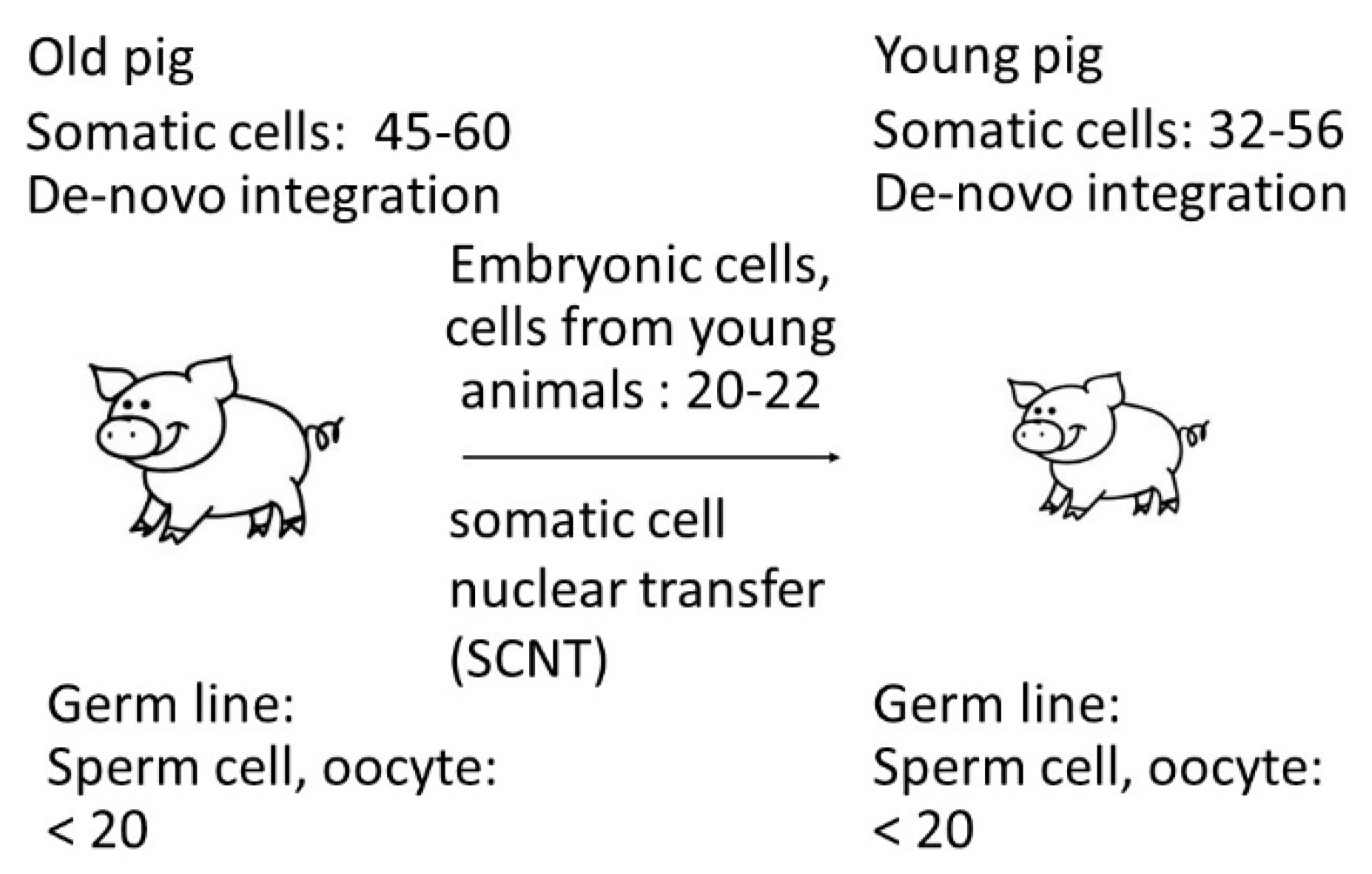

3.4. PERV Copy Number in the Genome of Auckland Island Pigs Obtained by SCNT

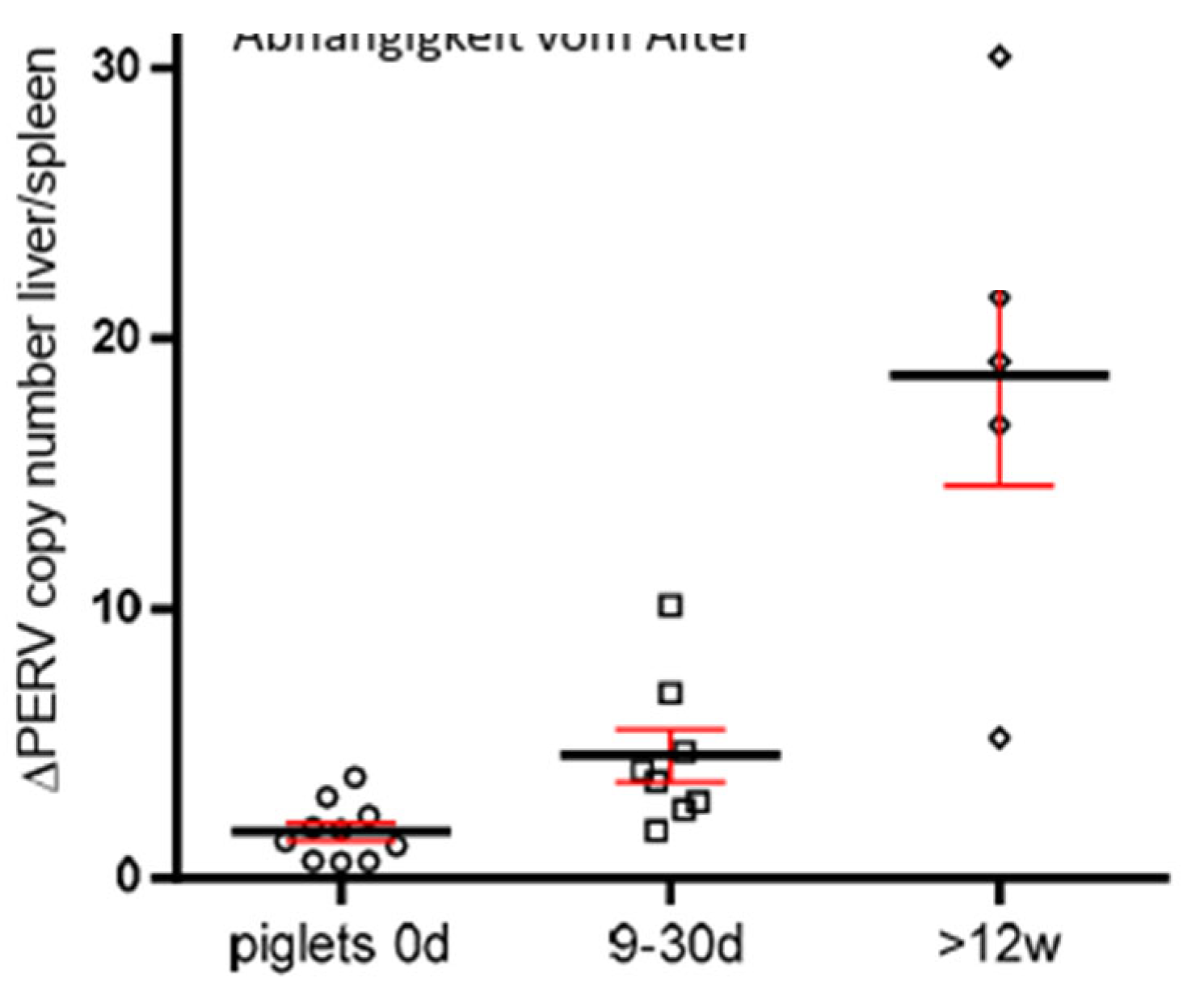

3.5. Increase of the PERV Copy Number with Age

3.6. Further Characterization of the Auckland Island Pigs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gongora J, Garkavenko, O, Moran C. Origins of Kune Kune and Auckland Island pigs in New Zealand. 7th World Congress on Genetic Applied to Livestock Production, August 19-23, 2002, Montpellier, France. 19 August 2002; -23.

- Robins, J.H.; Matisoo-Smith, E.; Ross, H.A. The origins of the feral pigs on the Auckland Islands. J. Royal Society of New Zealand 2003, 33, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Gongora, J.; Chen, Y.; Garkavenko, O.; Li, K.; Moran, C. Population genetic variability and origin of Auckland Island feral pigs. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2005, 35, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garkavenko, O.; Muzina, M.; Muzina, Z.; Powels, K.; Elliott, R.B.; Croxson, M.C. Monitoring for potentially xenozoonotic viruses in New Zealand pigs. J. Med Virol. 2003, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garkavenko, O.; Wynyard, S.; Nathu, D.; Simond, D.; Muzina, M.; Muzina, Z.; Scobie, L.; Hector, R.D.; Croxson, M.C.; Tan, P.; et al. Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus (PERV) and its Transmission Characteristics: A Study of the New Zealand Designated Pathogen-Free Herd. Cell Transplant. 2008, 17, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garkavenko, O.; Dieckhoff, B.; Wynyard, S.; Denner, J.; Elliott, R.B.; Tan, P.L.; Croxson, M.C. Absence of transmission of potentially xenotic viruses in a prospective pig to primate islet xenotransplantation study. J. Med Virol. 2008, 80, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynyard, S.; Nathu, D.; Garkavenko, O.; Denner, J.; Elliott, R. Microbiological safety of the first clinical pig islet xenotransplantation trial in New Zealand. Xenotransplantation 2014, 21, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, V.A.; Wynyard, S.; Matsumoto, S.; Abalovich, A.; Denner, J.; Elliott, R. No PERV transmission during a clinical trial of pig islet cell transplantation. Virus Res. 2017, 227, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Längin, M.; Reichart, B.; Krüger, L.; Fiebig, U.; Mokelke, M.; Radan, J.; Mayr, T.; Milusev, A.; Luther, F.; et al. Impact of porcine cytomegalovirus on long-term orthotopic cardiac xenotransplant survival. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Tasaki, M.; Sekijima, M.; Wilkinson, R.A.; Villani, V.; Moran, S.G.; Cormack, T.A.; Hanekamp, I.M.; Arn, J.S.; Fishman, J.A.; et al. Porcine Cytomegalovirus Infection Is Associated With Early Rejection of Kidney Grafts in a Pig to Baboon Xenotransplantation Model. Transplantation 2014, 98, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekijima, M.; Waki, S.; Sahara, H.; Tasaki, M.; Wilkinson, R.A.; Villani, V.; Shimatsu, Y.; Nakano, K.; Matsunari, H.; Nagashima, H.; et al. Results of Life-Supporting Galactosyltransferase Knockout Kidneys in Cynomolgus Monkeys Using Two Different Sources of Galactosyltransferase Knockout Swine. Transplantation 2014, 98, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Reduction of the survival time of pig xenotransplants by porcine cytomegalovirus. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, B.P.; Goerlich, C.E.; Singh, A.K.; Rothblatt, M.; Lau, C.L.; Shah, A.; Lorber, M.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.K.; Hong, S.N.; et al. Genetically Modified Porcine-to-Human Cardiac Xenotransplantation. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiuddin, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Scobie, L.; E Goerlich, C.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.; Crossan, C.; Burke, A.; Drachenberg, C.; Oguz, C.; et al. Graft dysfunction in compassionate use of genetically engineered pig-to-human cardiac xenotransplantation: a case report. Lancet 2023, 402, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Specke, V.; Thiesen, U.; Karlas, A.; Kurth, R. Genetic alterations of the long terminal repeat of an ecotropic porcine endogenous retrovirus during passage in human cells. Virology 2003, 314, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlas, A.; Irgang, M.; Votteler, J.; Specke, V.; Ozel, M.; Kurth, R.; Denner, J. Characterisation of a human cell-adapted porcine endogenous retrovirus PERV-A/C. Ann Transplant. 2010, 15, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrison, I.; Takeuchi, Y.; Bartosch, B.; Stoye, J.P. Determinants of High Titer in Recombinant Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13871–13879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A.; Wong, S.; Muller, J.; Davidson, C.E.; Rose, T.M.; Burd, P. Type C Retrovirus Released from Porcine Primary Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Infects Human Cells. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3082–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Schuurmann, K.J. High prevalence of recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV-A/Cs) in minipigs: a review on origin and presence. Viruses 2021, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, L.; Kristiansen, Y.; Reuber, E.; Möller, L.; Laue, M.; Reimer, C.; Denner, J. A Comprehensive Strategy for Screening for Xenotransplantation-Relevant Viruses in a Second Isolated Population of Göttingen Minipigs. Viruses 2019, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halecker, S.; Krabben, L.; Kristiansen, Y.; Krüger, L.; Möller, L.; Becher, D.; Laue, M.; Kaufer, B.; Reimer, C.; Denner, J. Rare isolation of human-tropic recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses PERV-A/C from Göttingen minipigs. Virol J. 2022, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Baker, R.; Schalk, S.; Scobie, L.; Tucker, A.W.; Opriessnig, T. Detection of Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus (PERV) Viremia in Diseased Versus Healthy US Pigs by Qualitative and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011, 58, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Güell, M.; Niu, D.; George, H.; Lesha, E.; Grishin, D.; Aach, J.; Shrock, E.; Xu, W.; Poci, J.; et al. Genome-wide inactivation of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs). Science 2015, 350, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, L.; Stillfried, M.; Prinz, C.; Schröder, V.; Neubert, L.K.; Denner, J. Copy Number and Prevalence of Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses (PERVs) in German Wild Boars. Viruses 2020, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Patience, C.; Magre, S.; Weiss, R.A.; Banerjee, P.T.; Le Tissier, P.; Stoye, J.P. Host range and interference studies of three classes of pig endogenous retrovirus. J Virol 1998, 72, 9986–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaulitz, D.; Mihica, D.; Adlhoch, C.; Semaan, M.; Denner, J. Improved pig donor screening including newly identified variants of porcine endogenous retrovirus-C (PERV-C). Arch. Virol. 2012, 158, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, V.A.; Plotzki, E.; Rotem, A.; Barkai, U.; Denner, J. Extended microbiological characterization of Göttingen minipigs: porcine cytomegalovirus and other viruses. Xenotransplantation 2016, 23, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, V.A.; Morozov, A.V.; Denner, J. New PCR diagnostic systems for the detection and quantification of porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV). Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, J.; Plotzki, E.; Denner, J. Virus Safety of Xenotransplantation: Prevalence of Porcine Cicrovirus 2 (PCV2) in Pigs. Ann. Virol. Res. 2016, 2, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, C.; Stillfried, M.; Neubert, L.K.; Denner, J. Detection of PCV3 in German wild boars. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, V.A.; Morozov, A.V.; Rotem, A.; Barkai, U.; Bornstein, S.; Denner, J. Extended Microbiological Characterization of Göttingen Minipigs in the Context of Xenotransplantation: Detection and Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis E Virus. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0139893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, U.; Fischer, K.; Bähr, A.; Runge, C.; Schnieke, A.; Wolf, E.; Denner, J. Porcine endogenous retroviruses: Quantification of the copy number in cell lines, pig breeds, and organs. Xenotransplantation 2018, 25, e12445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. How Active Are Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses (PERVs)? Viruses 2016, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynyard, S.; Garkavenko, O.; Elliot, R. Multiplex high resolution melting assay for estimation of Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus (PERV) relative gene dosage in pigs and detection of PERV infection in xenograft recipients. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 175, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, N.I.; Crossan, C.; Cruikshank, V.; Scobie, L.; Gianello, P. Characterization of porcine endogenous retrovirus expression in neonatal and adult pig pancreatic islets. Xenotransplantation 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacke, S.J.; Specke, V.; Denner, J. Differences in Release and Determination of Subtype of Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses Produced by Stimulated Normal Pig Blood Cells. Intervirology 2003, 46, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartosch, B.; Stefanidis, D.; Myers, R.; Weiss, R.; Patience, C.; Takeuchi, Y. Evidence and Consequence of Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus Recombination. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13880–13890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Q.; Zhang, M.-P.; Tong, X.-K.; Li, J.-Q.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, F.; Du, H.-P.; Zhou, M.; Ai, H.-S.; Huang, L.-S. Scan of the endogenous retrovirus sequences across the swine genome and survey of their copy number variation and sequence diversity among various Chinese and Western pig breeds. Zool. Res. 2022, 43, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tissier, P.; Stoye, J.P.; Takeuchi, Y.; Patience, C.; Weiss, R.A. Two sets of human-tropic pig retrovirus. Nature 1997, 389, 681–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patience, C.; Takeuchi, Y.; Weiss, R.A. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patience, C.; Switzer, W.M.; Takeuchi, Y.; Griffiths, D.J.; Goward, M.E.; Heneine, W.; Stoye, J.P.; Weiss, R.A. Multiple Groups of Novel Retroviral Genomes in Pigs and Related Species. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2771–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, Z.; Pan, M.; Ge, M.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y. Genetic Prevalence of Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus in Chinese Experimental Miniature Pigs. Transplant. Proc. 2011, 43, 2762–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Lee, J.; Yoon, J.-K.; Kim, N.Y.; Kim, G.-W.; Park, C.; Oh, Y.-K.; Kim, Y.B. Rapid Determination of Perv Copy Number From Porcine Genomic DNA by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Anim. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.; Cho, Y.; Gwon, Y.; Jang, Y.; Kim, S.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Distribution of Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus in Different Organs of the Hybrid of a Landrace and a Jeju Domestic Pig in Korea. Transplant. Proc. 2015, 47, 2067–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yu, P.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Bu, H. An effective method for the quantitative detection of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pig tissues. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Anim. 2010, 46, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quereda, J.J.; Herrero-Medrano, J.M.; Abellaneda, J.M.; García-Nicolás, O.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Pallarés, F.J.; Ramírez, P.; Muñoz, A.; Ramis, G. Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus Copy Number in Different Pig Breeds is not Related to Genetic Diversity. Zoonoses Public Heal. 2012, 59, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mang, R.; Maas, J.; Chen, X.; Goudsmit, J.; van der Kuyl, A.C. Identification of a novel type C porcine endogenous retrovirus: evidence that copy number of endogenous retroviruses increases during host inbreeding. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Webb, G.C.; Allen, R.D.; Moran, C. Characterizing and mapping porcine endogenous retrovirusesin Westran pigs. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5548–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenen, M.A.M.; Archibald, A.L.; Uenishi, H.; Tuggle, C.K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Rothschild, M.F.; Rogel-Gaillard, C.; Park, C.; Milan, D.; Megens, H.-J.; et al. Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 2012, 491, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.B.; Coleman, V.A.; Hindson, C.M.; Herrmann, J.; Hindson, B.J.; Bhat, S.; Emslie, K.R. Evaluation ofa droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, K.-C.; Choi, B.-S.; Oh, Y.-K.; Kim, Y.B. Repression of porcine endogenous retrovirus infection by human APOBEC3 proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 407, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specke, V.; Rubant, S.; Denner, J. Productive Infection of Human Primary Cells and Cell Lines with Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses. Virology 2001, 285, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, U.; Winkler, M.E.; Id, M.; Radeke, H.; Arseniev, L.; Takeuchi, Y.; Simon, A.R.; Patience, C.; Haverich, A.; Steinhoff, G. Productive infection of primary human endothelial cells by pig endogenous retrovirus (PERV). Xenotransplantation 2000, 7, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. Porcine endogenous retrovirus infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Xenotransplantation 2014, 22, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. What does the PERV copy number tell us? Xenotransplantation. 2022, 2, e12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, R.P.; Wildschutte, J.H.; Russo, C.; Coffin, J.M. Identification, characterization, and comparative genomic distribution of the HERV-K (HML-2) group of human endogenous retroviruses. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 90–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Galindo, R.; Kaplan, M.H.; He, S.; Contreras-Galindo, A.C.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, M.J.; Kappes, F.; Dube, D.; Chan, S.M.; Robinson, D.; Meng, F.; et al. HIV infection reveals widespread expansion of novel centromeric human endogenous retroviruses. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV-A/C): a new risk for xenotransplantation? Adv. Virol. 2008, 153, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, I.; Takeuchi, Y.; Bartosch, B.; Stoye, J.P. Determinants of High Titer in Recombinant Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13871–13879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Specke, V.; Thiesen, U.; Karlas, A.; Kurth, R. Genetic alterations of the long terminal repeat of an ecotropic porcine endogenous retrovirus during passage in human cells. Virology 2003, 314, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A.; Wong, S.; VanBrocklin, M.; Federspiel, M.J. Extended Analysis of the In Vitro Tropism of Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, L.; Kristiansen, Y.; Reuber, E.; Möller, L.; Laue, M.; Reimer, C.; Denner, J. A Comprehensive Strategy for Screening for Xenotransplantation-Relevant Viruses in a Second Isolated Population of Göttingen Minipigs. Viruses 2019, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieckhoff, B.; Puhlmann, J.; Büscher, K.; Hafner-Marx, A.; Herbach, N.; Bannert, N.; Büttner, M.; Wanke, R.; Kurth, R.; Denner, J. Expression of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) in melanomas of Munich miniature swine (MMS) Troll. Veter- Microbiol. 2007, 123, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittmann, I.; Mihica, D.; Plesker, R.; Denner, J. Expression of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV) in different organs of a pig. Virology 2012, 433, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scobie, L.; Taylor, S.; Wood, J.C.; Suling, K.M.; Quinn, G.; Meikle, S.; Patience, C.; Schuurman, H.-J.; Onions, D.E. Absence of Replication-Competent Human-Tropic Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses in the Germ Line DNA of Inbred Miniature Swine. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2502–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.C.; Quinn, G.; Suling, K.M.; Oldmixon, B.A.; Van Tine, B.A.; Cina, R.; Arn, S.; Huang, C.A.; Scobie, L.; Onions, D.E.; et al. Identification of Exogenous Forms of Human-Tropic Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus in Miniature Swine. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2494–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.I.; Wilkinson, R.; Fishman, J.A. Genomic presence of recombinant porcine endogenous retrovirus in transmitting miniature swine. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Sequence | Location (nucleotid number) | Accession number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERV pol1-forward | CGACTGCCCCAAGGGTTCAA | 3568-3587 | HM159246 | Yang et al., 2015 [23] |

| PERV pol2-reverse | TCTCTCCTGCAAATCTGGGCC | 3803-3783 | ||

| PERV pol probe | /56FAM/CACGTACTGGAGGAGGGTCACCTG | 3678-3655 | ||

| Pig actin forward | TAACCGATCCTTTCAAGCATTT | Krüger et al., 2020 [24] | ||

| Pig actin reverse | TGGTTTCAAAGCTTGCATCATA | |||

| Pig actin probe | /5HEX/CGTGGGGATGCTTCCTGAGAAAG | |||

| Pig GAPDH forward Pig GAPDH reverse |

TTCACTCCGACCTTCACCAT CCGCGATCTAATGTTCTCTTTC |

3951-3970 4022-4001 |

NC_010447.5 (396823) | Krüger et al., 2020 [24] |

| Pig GAPDH probe | /5HEX/CAGCCGCGTCCCTGAGACAC | 3991-3972 | ||

| PERV-C forward PERV-C reverse |

CTGACCTGGATTAGAACTGG ATGTTAGAGGATGGTCCTGG |

6606-6625 6867-6886 |

AM229312 | Takeuchi et al. [25,26] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).