Submitted:

13 September 2023

Posted:

14 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

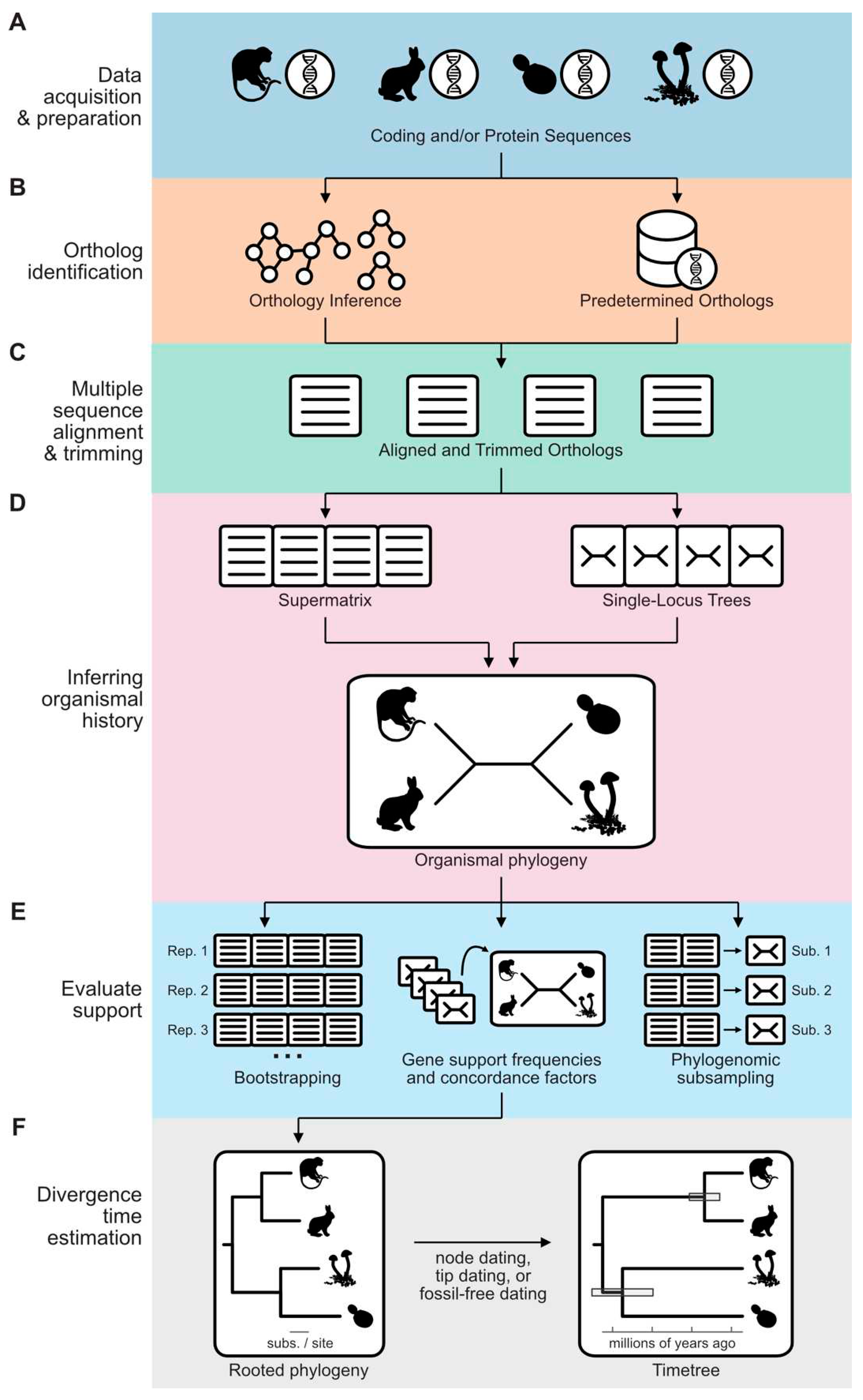

A Workflow for Robust Phylogenomic Inference

Data Acquisition and Preparation

Gene Orthology Determination

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Trimming

Model Selection

Gene Alignment Concatenation or Coalescence-based Methods for Inferring Organismal History

Examining Bipartition Support

Time-calibration of inferred phylogenetic divergences

Detecting Reticulate Evolution

Hybridization/introgression

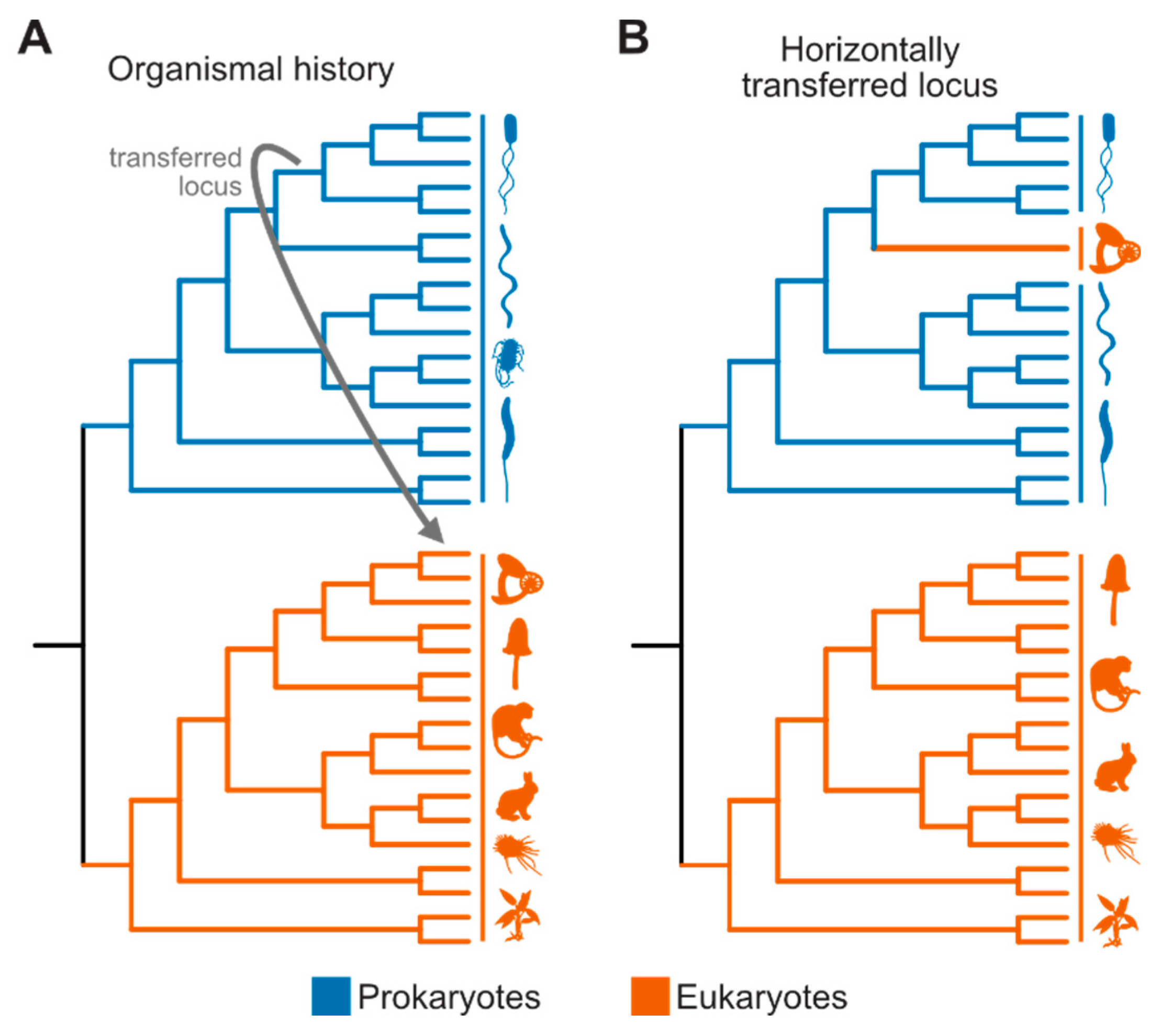

Horizontal gene transfer

Phylogenetic Networks

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Abadi, S.; Azouri, D.; Pupko, T.; Mayrose, I. Model selection may not be a mandatory step for phylogeny reconstruction. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, R.; Albach, D.; Ansell, S.; Arntzen, J. W.; Baird, S. J. E.; Bierne, N.; Boughman, J.; Brelsford, A.; Buerkle, C. A.; Buggs, R.; Butlin, R. K.; Dieckmann, U.; Eroukhmanoff, F.; Grill, A.; Cahan, S. H.; Hermansen, J. S.; Hewitt, G.; Hudson, A. G.; Jiggins, C.; Jones, J.; Keller, B.; Marczewski, T.; Mallet, J.; Martinez-Rodriguez, P.; Möst, M.; Mullen, S.; Nichols, R.; Nolte, A. W.; Parisod, C.; Pfennig, K.; Rice, A. M.; Ritchie, M. G.; Seifert, B.; Smadja, C. M.; Stelkens, R.; Szymura, J. M.; Väinölä, R.; Wolf, J. B. W.; Zinner, D. Hybridization and speciation. J. Evol. Biol 2013, 26, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adavoudi, R.; Pilot, M. Consequences of Hybridization in Mammals: A Systematic Review. Genes 2021, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, W. G.; Wisecaver, J. H.; Rokas, A.; Hittinger, C. T. Horizontally acquired genes in early-diverging pathogenic fungi enable the use of host nucleosides and nucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2016, 113, 4116–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R. H.; Bogusz, M.; Whelan, S. Identifying Clusters of High Confidence Homologies in Multiple Sequence Alignments. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2019, 36, 2340–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.; Ryan, H.; Davis, B. W.; King, C.; Frantz, L.; Irving-Pease, E.; Barnett, R.; Linderholm, A.; Loog, L.; Haile, J.; Lebrasseur, O.; White, M.; Kitchener, A. C.; Murphy, W. J.; Larson, G. A mitochondrial genetic divergence proxy predicts the reproductive compatibility of mammalian hybrids. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20200690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Carretero, S.; Kapli, P.; Yang, Z. Beginner’s Guide on the Use of PAML to Detect Positive Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andréoletti, J.; Zwaans, A.; Warnock, R. C. M.; Aguirre-Fernández, G.; Barido-Sottani, J.; Gupta, A.; Stadler, T.; Manceau, M. The Occurrence Birth–Death Process for Combined-Evidence Analysis in Macroevolution and Epidemiology. Systematic Biology 2022, 71, 1440–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B. J.; Huang, I.-T.; Hanage, W. P. Horizontal gene transfer and adaptive evolution in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazy, H.; Sela, I.; Karin, E. Levy; Landan, G.; Pupko, T. Multiple Sequence Alignment Averaging Improves Phylogeny Reconstruction. Systematic Biology 2019, 68, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, D. L.; Cummings, M. P.; Baele, G.; Darling, A. E.; Lewis, P. O.; Swofford, D. L.; Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Lemey, P.; Rambaut, A.; Suchard, M. A. BEAGLE 3: Improved Performance, Scaling, and Usability for a High-Performance Computing Library for Statistical Phylogenetics. Systematic Biology 2019, 68, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ba#xF1os, H.; Susko, E.; Roger, A. J. Is Over-parameterization a Problem for Profile Mixture Models? Evolutionary Biology 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Montoya, J.; Reis, M. Dos; Yang, Z. Comparison of different strategies for using fossil calibrations to generate the time prior in Bayesian molecular clock dating. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2017, 114, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barley, A. J.; Brown, J. M.; Thomson, R. C. Impact of Model Violations on the Inference of Species Boundaries Under the Multispecies Coalescent. Systematic Biology 2018, 67, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, C.; Marsit, S.; Landry, C. R. Interspecific hybrids show a reduced adaptive potential under DNA damaging conditions. Evol Appl 2021, 14, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancur-R., R.; Arcila, D.; Vari, R. P.; Hughes, L. C.; Oliveira, C.; Sabaj, M. H.; Ortí, G. Phylogenomic incongruence, hypothesis testing, and taxonomic sampling. Evolution 2019, 73, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Ané, C. Phylogenetic Trees and Networks Can Serve as Powerful and Complementary Approaches for Analysis of Genomic Data. Systematic Biology 2020, 69, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, M.; Archibald, J. M.; Childers, A. K.; Coddington, J. A.; Crandall, K. A.; Palma, F. Di; Durbin, R.; Edwards, S. V.; Graves, J. A. M.; Hackett, K. J.; Hall, N.; Jarvis, E. D.; Johnson, R. N.; Karlsson, E. K.; Kress, W. J.; Kuraku, S.; Lawniczak, M. K. N.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Lopez, J. V.; Moran, N. A.; Robinson, G. E.; Ryder, O. A.; Shapiro, B.; Soltis, P. S.; Warnow, T.; Zhang, G.; Lewin, H. A. Why sequence all eukaryotes? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2022, 119, e2115636118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blischak, P. D.; Chifman, J.; Wolfe, A. D.; Kubatko, L. S. HyDe: a Python package for genome-scale hybridization detection. Systematic Biology 2018, 67, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A. M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R. R. DensiTree: making sense of sets of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1372–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouckaert, R.; Vaughan, T. G.; Barido-Sottani, J.; Duchêne, S.; Fourment, M.; Gavryushkina, A.; Heled, J.; Jones, G.; Kühnert, D.; Maio, N. De; Matschiner, M.; Mendes, F. K.; Müller, N. F.; Ogilvie, H. A.; Plessis, L. du; Popinga, A.; Rambaut, A.; Rasmussen, D.; Siveroni, I.; Suchard, M. A.; Wu, C.-H.; Xie, D.; Zhang, C.; Stadler, T.; Drummond, A. J. BEAST 2. 5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 2019, 15, e1006650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bringloe, T. T.; Zaparenkov, D.; Starko, S.; Grant, W. S.; Vieira, C.; Kawai, H.; Hanyuda, T.; Filbee-Dexter, K.; Klimova, A.; Klochkova, T. A.; Krause-Jensen, D.; Olesen, B.; Verbruggen, H. Whole-genome sequencing reveals forgotten lineages and recurrent hybridizations within the kelp genus Alaria (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol 2021, 57, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brohée, S.; Helden, J. Van. Evaluation of clustering algorithms for protein-protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brůna, T.; Hoff, K. J.; Lomsadze, A.; Stanke, M.; Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Ashkenazy, H.; Reuter, K.; Kennedy, J. A.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive clustering of protein sequences at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND DeepClust. Genomics 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, R.; Vecchyo, D. Ortega-Del; Gehring, C.; Michelson, R.; Flores-Rentería, D.; Klein, B.; Whipple, A. V.; Flores-Rentería, L. Sequential hybridization may have facilitated ecological transitions in the Southwestern pinyon pine syngameon. New Phytologist 2023, 237, 2435–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T. L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Li, M.; Ogilvie, H. A.; Nakhleh, L. The Impact of Model Misspecification on Phylogenetic Network Inference. Evolutionary Biology 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Gabaldón, T. Phylogenomics supports microsporidia as the earliest diverging clade of sequenced fungi. BMC Biol 2012, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, T.; Scotland, R. W. Uncertainty in Divergence Time Estimation. Systematic Biology 2021, 70, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenci, U.; Sibbald, S. J.; Curtis, B. A.; Kamikawa, R.; Eme, L.; Moog, D.; Henrissat, B.; Maréchal, E.; Chabi, M.; Djemiel, C.; Roger, A. J.; Kim, E.; Archibald, J. M. Nuclear genome sequence of the plastid-lacking cryptomonad Goniomonas avonlea provides insights into the evolution of secondary plastids. BMC Biol 2018, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chain, F. J.; Dushoff, J.; Evans, B. J. The odds of duplicate gene persistence after polyploidization. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charpentier, C. P.; Wright, A. M. Revticulate: An R framework for interaction with RevBayes. Methods Ecol Evol 2022, 13, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.; Xu, P. Research advances and future perspectives of genomics and genetic improvement in allotetraploid common carp. Reviews in Aquaculture 2022, 14, 957–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, S.; Zhang, J.; Park, C. Is Phylotranscriptomics as Reliable as Phylogenomics? Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chifman, J.; Kubatko, L. Quartet Inference from SNP Data Under the Coalescent Model. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3317–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikina, M.; Robinson, J. D.; Clark, N. L. Hundreds of Genes Experienced Convergent Shifts in Selective Pressure in Marine Mammals. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33, 2182–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. W.; Donoghue, P. C. J. Whole-Genome Duplication and Plant Macroevolution. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 23, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M. A.; Gonçalves, C.; Sampaio, J. P.; Gonçalves, P. Extensive Intra-Kingdom Horizontal Gene Transfer Converging on a Fungal Fructose Transporter Gene. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, G. A.; Davín, A. A.; Mahendrarajah, T. A.; Szánthó, L. L.; Spang, A.; Hugenholtz, P.; Szöllősi, G. J.; Williams, T. A. A rooted phylogeny resolves early bacterial evolution. Science 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criscuolo, A.; Gribaldo, S. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol Biol 2010, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannemann, M.; Kelso, J. The Contribution of Neanderthals to Phenotypic Variation in Modern Humans. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2017, 101, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannemann, M.; Prüfer, K.; Kelso, J. Functional implications of Neandertal introgression in modern humans. Genome Biol 2017, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darriba, D.; Posada, D.; Kozlov, A. M.; Stamatakis, A.; Morel, B.; Flouri, T. ModelTest-NG: A New and Scalable Tool for the Selection of DNA and Protein Evolutionary Models. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G. L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 772–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnan, J. H.; Rosenberg, N. A. Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2009, 24, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Depotter, J. R.; Seidl, M. F.; Wood, T. A.; Thomma, B. P. Interspecific hybridization impacts host range and pathogenicity of filamentous microbes. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2016, 32, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Tapia, P.; Maggs, C. A.; West, J. A.; Verbruggen, H. Analysis of chloroplast genomes and a supermatrix inform reclassification of the Rhodomelaceae (Rhodophyta). J. Phycol 2017, 53, 920–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobzhansky, T. Genetics and the Origin of Species; Columbia university press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell, R. G.; Gile, G.; McCallum, G.; Méheust, R.; Bapteste, E. P.; Klinger, C. M.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Freeman, K. D.; Richter, D. J.; Bowler, C. Chimeric origins of ochrophytes and haptophytes revealed through an ancient plastid proteome. eLife 2017, 6, e23717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorrell, R. G.; Kuo, A.; Füssy, Z.; Richardson, E. H.; Salamov, A.; Zarevski, N.; Freyria, N. J.; Ibarbalz, F. M.; Jenkins, J.; Karlusich, J. J. Pierella; Steindorff, A. Stecca; Edgar, R. E.; Handley, L.; Lail, K.; Lipzen, A.; Lombard, V.; McFarlane, J.; Nef, C.; Vanclová, A. M. Novák; Peng, Y.; Plott, C.; Potvin, M.; Vieira, F. R. J.; Barry, K.; Vargas, C. De; Henrissat, B.; Pelletier, E.; Schmutz, J.; Wincker, P.; Dacks, J. B.; Bowler, C.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Lovejoy, C. Convergent evolution and horizontal gene transfer in Arctic Ocean microalgae. Life Sci. Alliance 2023, 6, e202201833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Reis, M.; Donoghue, P. C. J.; Yang, Z. Bayesian molecular clock dating of species divergences in the genomics era. Nat Rev Genet 2016, 17, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Reis, M.; Gunnell, G. F.; Barba-Montoya, J.; Wilkins, A.; Yang, Z.; Yoder, A. D. Using Phylogenomic Data to Explore the Effects of Relaxed Clocks and Calibration Strategies on Divergence Time Estimation: Primates as a Test Case. Systematic Biology 2018, 67, 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.; Jiménez-Silva, C. L.; Bouckaert, R. StarBeast3: Adaptive Parallelized Bayesian Inference under the Multispecies Coalescent. Systematic Biology 2022, 71, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, A. P.; O’Brien, C. E.; Offei, B.; Coughlan, A. Y.; Ortiz-Merino, R. A.; Butler, G.; Byrne, K. P.; Wolfe, K. H. Coverage-Versus-Length Plots, a Simple Quality Control Step for de Novo Yeast Genome Sequence Assemblies. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics 2019, 9, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A. J.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Phillips, M. J.; Rambaut, A. Relaxed Phylogenetics and Dating with Confidence. PLoS Biol 2006, 4, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C. W.; Hejnol, A.; Matus, D. Q.; Pang, K.; Browne, W. E.; Smith, S. A.; Seaver, E.; Rouse, G. W.; Obst, M.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Sørensen, M. V.; Haddock, S. H. D.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A.; Okusu, A.; Kristensen, R. M.; Wheeler, W. C.; Martindale, M. Q.; Giribet, G. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature 2008, 452, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D. A. R.; Ree, R. H. Inferring Phylogeny and Introgression using RADseq Data: An Example from Flowering Plants (Pedicularis: Orobanchaceae). Systematic Biology 2013, 62, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S. R. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput Biol 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, N. B.; Frandsen, P. B.; Miyagi, M.; Clavijo, B.; Davey, J.; Dikow, R. B.; García-Accinelli, G.; Belleghem, S. M. Van; Patterson, N.; Neafsey, D. E.; Challis, R.; Kumar, S.; Moreira, G. R. P.; Salazar, C.; Chouteau, M.; Counterman, B. A.; Papa, R.; Blaxter, M.; Reed, R. D.; Dasmahapatra, K. K.; Kronforst, M.; Joron, M.; Jiggins, C. D.; McMillan, W. O.; Palma, F. Di; Blumberg, A. J.; Wakeley, J.; Jaffe, D.; Mallet, J. Genomic architecture and introgression shape a butterfly radiation. Science 2019, 366, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edger, P. P.; Poorten, T. J.; VanBuren, R.; Hardigan, M. A.; Colle, M.; McKain, M. R.; Smith, R. D.; Teresi, S. J.; Nelson, A. D. L.; Wai, C. M.; Alger, E. I.; Bird, K. A.; Yocca, A. E.; Pumplin, N.; Ou, S.; Ben-Zvi, G.; Brodt, A.; Baruch, K.; Swale, T.; Shiue, L.; Acharya, C. B.; Cole, G. S.; Mower, J. P.; Childs, K. L.; Jiang, N.; Lyons, E.; Freeling, M.; Puzey, J. R.; Knapp, S. J. Origin and evolution of the octoploid strawberry genome. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, S. V. Phylogenomic subsampling: a brief review. Zool Scr 2016, 45, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D. M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D. M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol 2015, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D. M.; Kelly, S. STAG: Species Tree Inference from All Genes. Evolutionary Biology 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feijó, A.; Ge, D.; Wen, Z.; Cheng, J.; Xia, L.; Patterson, B. D.; Yang, Q. Mammalian diversification bursts and biotic turnovers are synchronous with Cenozoic geoclimatic events in Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2022, 119, e2207845119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.-F.; Doolittle, R. F. Progressive sequence alignment as a prerequisite to correct phylogenetic trees. J. Mol. Evol 1987, 25, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.; Gabaldón, T. Gene gain and loss across the metazoan tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol 2020, 4, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, R.; Gabaldón, T.; Dessimoz, C. Orthology: definitions, inference, and impact on species phylogeny inference. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, W.; Yang, Z. INDELible: A Flexible Simulator of Biological Sequence Evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2009, 26, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flouri, T.; Huang, J.; Jiao, X.; Kapli, P.; Rannala, B.; Yang, Z. Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference using Relaxed-clocks and the Multispecies Coalescent. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flouri, T.; Jiao, X.; Rannala, B.; Yang, Z. Species Tree Inference with BPP Using Genomic Sequences and the Multispecies Coalescent. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 2585–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, R.; Ely, B. Codon Usage Methods for Horizontal Gene Transfer Detection Generate an Abundance of False Positive and False Negative Results. Curr Microbiol 2012, 65, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldón, T.; Koonin, E. V. Functional and evolutionary implications of gene orthology. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, L. J.; López-García, P.; Torruella, G.; Karpov, S.; Moreira, D. Phylogenomics of a new fungal phylum reveals multiple waves of reductive evolution across Holomycota. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtier, N. A Model of Horizontal Gene Transfer and the Bacterial Phylogeny Problem. Systematic Biology 2007, 56, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtier, N.; Gouy, M. Inferring phylogenies from DNA sequences of unequal base compositions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1995, 92, 11317–11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatesy, J.; Meredith, R. W.; Janecka, J. E.; Simmons, M. P.; Murphy, W. J.; Springer, M. S. Resolution of a concatenation/coalescence kerfuffle: partitioned coalescence support and a robust family-level tree for Mammalia. Cladistics 2017, 33, 295–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawryluk, R. M. R.; Tikhonenkov, D. V.; Hehenberger, E.; Husnik, F.; Mylnikov, A. P.; Keeling, P. J. Non-photosynthetic predators are sister to red algae. Nature 2019, 572, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladyshev, E. A.; Meselson, M.; Arkhipova, I. R. Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers. Science 2008, 320, 1210–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, C.; Gonçalves, P. Multilayered horizontal operon transfers from bacteria reconstruct a thiamine salvage pathway in yeasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2019, 116, 22219–22228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Wisecaver, J. H.; Kominek, J.; Oom, M. S.; Leandro, M. J.; Shen, X.-X.; Opulente, D. A.; Zhou, X.; Peris, D.; Kurtzman, C. P.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A.; Gonçalves, P. Evidence for loss and reacquisition of alcoholic fermentation in a fructophilic yeast lineage. eLife 2018, 7, e33034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, P.; Gonçalves, C. Horizontal gene transfer in yeasts. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2022, 76, 101950. [Google Scholar]

- Gophna, U.; Altman-Price, N. Horizontal Gene Transfer in Archaea—From Mechanisms to Genome Evolution. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 2022, 76, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R. E.; Krause, J.; Briggs, A. W.; Maricic, T.; Stenzel, U.; Kircher, M.; Patterson, N.; Li, H.; Zhai, W.; Fritz, M. H.-Y. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. science 2010, 328, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, H.; Gardner, E. M.; Viruel, J.; Pokorny, L.; Johnson, M. G. Strategies for reducing per-sample costs in target capture sequencing for phylogenomics and population genomics in plants. Appl Plant Sci 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, J. A. P.; Hibbins, M. S.; Moyle, L. C. Assessing biological factors affecting postspeciation introgression. Evolution Letters 2020, 4, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M. G.; Bravo, G. A.; Claramunt, S.; Cuervo, A. M.; Derryberry, G. E.; Battilana, J.; Seeholzer, G. F.; McKay, J. S.; O’Meara, B. C.; Faircloth, B. C.; Edwards, S. V.; Pérez-Emán, J.; Moyle, R. G.; Sheldon, F. H.; Aleixo, A.; Smith, B. T.; Chesser, R. T.; Silveira, L. F.; Cracraft, J.; Brumfield, R. T.; Derryberry, E. P. The evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Science 2020, 370, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, T. A.; Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Stadler, T. The fossilized birth–death process for coherent calibration of divergence-time estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbins, M. S.; Hahn, M. W. Phylogenomic approaches to detecting and characterizing introgression. Genetics 2022, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S. Y. M. Calibrating molecular estimates of substitution rates and divergence times in birds. J Avian Biology 2007, 38, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. Y. W.; Duchêne, S. Molecular-clock methods for estimating evolutionary rates and timescales. Mol Ecol 2014, 23, 5947–5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S. Y. W.; Phillips, M. J. Accounting for Calibration Uncertainty in Phylogenetic Estimation of Evolutionary Divergence Times. Systematic Biology 2009, 58, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, D. T.; Chernomor, O.; Haeseler, A. von; Minh, B. Q.; Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H#xF6hna, S.; Landis, M. J.; Heath, T. A. Phylogenetic Inference Using RevBayes. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 2017, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Höhna, S.; Landis, M. J.; Heath, T. A.; Boussau, B.; Lartillot, N.; Moore, B. R.; Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Ronquist, F. RevBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference Using Graphical Models and an Interactive Model-Specification Language. Syst Biol 2016, 65, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnik, F.; McCutcheon, J. P. Functional horizontal gene transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huson, D. H. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huson, D. H.; Kl#xF6pper, T.; Lockhart, P. J.; Steel, M. A. Reconstruction of Reticulate Networks from Gene Trees. Pp. 233–249 in S. Miyano, J. Mesirov, S. Kasif, S. Istrail, P. A. Pevzner, and M. Waterman, eds. Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, N. A. T.; Pittis, A. A.; Richards, T. A.; Keeling, P. J. Systematic evaluation of horizontal gene transfer between eukaryotes and viruses. Nat Microbiol 2021, 7, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, A.; Carruthers, M.; Eckmann, R.; Yohannes, E.; Adams, C. E.; Behrmann-Godel, J.; Elmer, K. R. Rapid niche expansion by selection on functional genomic variation after ecosystem recovery. Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 3, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, V. D. A.; Sukno, S. A.; Thon, M. R. Identification of horizontally transferred genes in the genus Colletotrichum reveals a steady tempo of bacterial to fungal gene transfer. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Flouri, T.; Yang, Z. Multispecies coalescent and its applications to infer species phylogenies and cross-species gene flow. National Science Review 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kainer, D.; Lanfear, R. The Effects of Partitioning on Phylogenetic Inference. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2015, 32, 1611–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B. Q.; Wong, T. K. F.; Haeseler, A. Von; Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapli, P.; Yang, Z.; Telford, M. J. Phylogenetic tree building in the genomic age. Nat Rev Genet 2020, 21, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.; Rokas, A. Embracing Uncertainty in Reconstructing Early Animal Evolution. Current Biology 2017, 27, R1081–R1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishino, H.; Hasegawa, M. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in hominoidea. J Mol Evol 1989, 29, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobert, K.; Salichos, L.; Rokas, A.; Stamatakis, A. Computing the Internode Certainty and Related Measures from Partial Gene Trees. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocot, K. M.; Citarella, M. R.; Moroz, L. L.; Halanych, K. M. PhyloTreePruner: A Phylogenetic Tree-Based Approach for selection of Orthologous sequences for phylogenomics. Evol Bioinform Online 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kominek, J.; Doering, D. T.; Opulente, D. A.; Shen, X.-X.; Zhou, X.; DeVirgilio, J.; Hulfachor, A. B.; Groenewald, M.; Mcgee, M. A.; Karlen, S. D.; Kurtzman, C. P.; Rokas, A.; Hittinger, C. T. Eukaryotic Acquisition of a Bacterial Operon. Cell 2019, 176, 1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsovoulos, G. D.; Noriot, S. Granjeon; Bailly-Bechet, M.; Danchin, E. G. J.; Rancurel, C. AvP: A software package for automatic phylogenetic detection of candidate horizontal gene transfers. PLoS Comput Biol 2022, 18, e1010686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Meyer, W. K.; Partha, R.; Mao, W.; Clark, N. L.; Chikina, M. RERconverge: an R package for associating evolutionary rates with convergent traits. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4815–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, A. M.; Darriba, D.; Flouri, T.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriventseva, E. V.; Kuznetsov, D.; Tegenfeldt, F.; Manni, M.; Dias, R.; Simão, F. A.; Zdobnov, E. M. OrthoDB v10: sampling the diversity of animal, plant, fungal, protist, bacterial and viral genomes for evolutionary and functional annotations of orthologs. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, D807–D811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kück, P.; Longo, G. C. FASconCAT-G: extensive functions for multiple sequence alignment preparations concerning phylogenetic studies. Front Zool 2014, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Embracing Green Computing in Molecular Phylogenetics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartillot, N. PhyloBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Site-heterogeneous Models. P. 1.5:1--1.5:16 in C. Scornavacca, F. Delsuc, and N. Galtier, eds. Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era. No commercial publisher | Authors open access book. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot, N.; Brinkmann, H.; Philippe, H. Suppression of long-branch attraction artefacts in the animal phylogeny using a site-heterogeneous model. BMC Evol Biol 2007, 7, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, F.; Entfellner, J.-B. Domelevo; Wilkinson, E.; Correia, D.; Felipe, M. Dávila; Oliveira, T. De; Gascuel, O. Renewing Felsenstein’s phylogenetic bootstrap in the era of big data. Nature 2018, 556, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepage, T.; Bryant, D.; Philippe, H.; Lartillot, N. A General Comparison of Relaxed Molecular Clock Models. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2007, 24, 2669–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Stoeckert, C. J.; Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: Identification of Ortholog Groups for Eukaryotic Genomes. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; David, K. T.; Shen, X.-X.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Halanych, K. M.; Rokas, A. Feature frequency profile-based phylogenies are inaccurate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2020, 117, 31580–31581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Steenwyk, J. L.; LaBella, A. L.; Harrison, M.-C.; Groenewald, M.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X.-X.; Zhao, T.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Contrasting modes of macro and microsynteny evolution in a eukaryotic subphylum. Current Biology 2022a, S0960982222016700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Shi, Z.; Pang, L.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Pan, R.; Zhou, W.; Chen, X.; Rokas, A.; Huang, J.; Shen, X.-X. HGT is widespread in insects and contributes to male courtship in lepidopterans. Cell 2022b, 185, 2975–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; James, T. Y.; Stajich, J. E.; Spatafora, J. W.; Groenewald, M.; Dunn, C. W.; Hittinger, C. T.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. A genome-scale phylogeny of the kingdom Fungi. Current Biology 2021, 31, 1653–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Torre, A. R. De La; Sterck, L.; Cánovas, F. M.; Avila, C.; Merino, I.; Cabezas, J. A.; Cervera, M. T.; Ingvarsson, P. K.; Peer, Y. Van De. Single-Copy Genes as Molecular Markers for Phylogenomic Studies in Seed Plants. Genome Biology and Evolution 2017, 9, 1130–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Patel, S.; Litvintseva, A. P.; Floyd, A.; Mitchell, T. G.; Heitman, J. Diploids in the Cryptococcus neoformans Serotype A Population Homozygous for the α Mating Type Originate via Unisexual Mating. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5, e1000283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Pearl, D. K.; Brumfield, R. T.; Edwards, S. V. Estimating species trees using multiple-allele DNA sequence data. Evolution 2008, 62, 2080–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yu, L.; Kubatko, L.; Pearl, D. K.; Edwards, S. V. Coalescent methods for estimating phylogenetic trees. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2009a, 53, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yu, L.; Pearl, D. K.; Edwards, S. V. Estimating Species Phylogenies Using Coalescence Times among Sequences. Systematic Biology 2009b, 58, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löytynoja, A.; Goldman, N. An algorithm for progressive multiple alignment of sequences with insertions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 10557–10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutteropp, S.; Scornavacca, C.; Kozlov, A. M.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. NetRAX: accurate and fast maximum likelihood phylogenetic network inference. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 3725–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. Hybridization as an invasion of the genome. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Mallet, J. Hybridization, ecological races and the nature of species: empirical evidence for the ease of speciation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2008, 363, 2971–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcet-Houben, M.; Gabaldón, T. Beyond the Whole-Genome Duplication: Phylogenetic Evidence for an Ancient Interspecies Hybridization in the Baker’s Yeast Lineage. PLoS Biol 2015, 13, e1002220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. H.; Davey, J. W.; Jiggins, C. D. Evaluating the use of ABBA–BABA statistics to locate introgressed loci. Molecular biology and evolution 2015, 32, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Durán, J. M.; Ryan, J. F.; Vellutini, B. C.; Pang, K.; Hejnol, A. Increased taxon sampling reveals thousands of hidden orthologs in flatworms. Genome Res 2017, 27, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Estrada, V.; Graña-Miraglia, L.; López-Leal, G.; Castillo-Ramírez, S. Phylogenomics Reveals Clear Cases of Misclassification and Genus-Wide Phylogenetic Markers for Acinetobacter. Genome Biology and Evolution 2019, 11, 2531–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, C. G. P.; Mulhair, P. O.; Siu-Ting, K.; Creevey, C. J.; O’Connell, M. J. Improving Orthologous Signal and Model Fit in Datasets Addressing the Root of the Animal Phylogeny. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minge, M. A.; Shalchian-Tabrizi, K.; Tørresen, O. K.; Takishita, K.; Probert, I.; Inagaki, Y.; Klaveness, D.; Jakobsen, K. S. A phylogenetic mosaic plastid proteome and unusual plastid-targeting signals in the green-colored dinoflagellate Lepidodinium chlorophorum. BMC Evol Biol 2010, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B. Q.; Dang, C. C.; Vinh, L. S.; Lanfear, R. QMaker: Fast and Accurate Method to Estimate Empirical Models of Protein Evolution. Systematic Biology 2021, 70, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B. Q.; Hahn, M. W.; Lanfear, R. New Methods to Calculate Concordance Factors for Phylogenomic Datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020a, 37, 2727–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B. Q.; Schmidt, H. A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M. D.; Haeseler, A. von; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020b, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misof, B.; Liu, S.; Meusemann, K.; Peters, R. S.; Donath, A.; Mayer, C.; Frandsen, P. B.; Ware, J.; Flouri, T.; Beutel, R. G.; Niehuis, O.; Petersen, M.; Izquierdo-Carrasco, F.; Wappler, T.; Rust, J.; Aberer, A. J.; Aspöck, U.; Aspöck, H.; Bartel, D.; Blanke, A.; Berger, S.; Böhm, A.; Buckley, T. R.; Calcott, B.; Chen, J.; Friedrich, F.; Fukui, M.; Fujita, M.; Greve, C.; Grobe, P.; Gu, S.; Huang, Y.; Jermiin, L. S.; Kawahara, A. Y.; Krogmann, L.; Kubiak, M.; Lanfear, R.; Letsch, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, H.; Machida, R.; Mashimo, Y.; Kapli, P.; McKenna, D. D.; Meng, G.; Nakagaki, Y.; Navarrete-Heredia, J. L.; Ott, M.; Ou, Y.; Pass, G.; Podsiadlowski, L.; Pohl, H.; Reumont, B. M. Von; Schütte, K.; Sekiya, K.; Shimizu, S.; Slipinski, A.; Stamatakis, A.; Song, W.; Su, X.; Szucsich, N. U.; Tan, M.; Tan, X.; Tang, M.; Tang, J.; Timelthaler, G.; Tomizuka, S.; Trautwein, M.; Tong, X.; Uchifune, T.; Walzl, M. G.; Wiegmann, B. M.; Wilbrandt, J.; Wipfler, B.; Wong, T. K. F.; Wu, Q.; Wu, G.; Xie, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, Q.; Yeates, D. K.; Yoshizawa, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, L.; Ziesmann, T.; Zou, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Kjer, K. M.; Zhou, X. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 2014, 346, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixão, V.; Gabaldón, T. Genomic evidence for a hybrid origin of the yeast opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. BMC Biol 2020, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongiardino Koch, N. Phylogenomic Subsampling and the Search for Phylogenetically Reliable Loci. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 4025–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, B. M.; Payne, C.; Langdon, Q.; Powell, D. L.; Brandvain, Y.; Schumer, M. The genomic consequences of hybridization. eLife 2021, 10, e69016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A. A.; Galachyants, Y. P. Diatom genes originating from red and green algae: Implications for the secondary endosymbiosis models. Marine Genomics 2019, 45, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Gómez, S. A.; Mejía-Franco, F. G.; Durnin, K.; Colp, M.; Grisdale, C. J.; Archibald, J. M.; Slamovits, C. H. The New Red Algal Subphylum Proteorhodophytina Comprises the Largest and Most Divergent Plastid Genomes Known. Current Biology 2017, 27, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neafsey, D. E.; Barker, B. M.; Sharpton, T. J.; Stajich, J. E.; Park, D. J.; Whiston, E.; Hung, C.-Y.; McMahan, C.; White, J.; Sykes, S.; Heiman, D.; Young, S.; Zeng, Q.; Abouelleil, A.; Aftuck, L.; Bessette, D.; Brown, A.; FitzGerald, M.; Lui, A.; Macdonald, J. P.; Priest, M.; Orbach, M. J.; Galgiani, J. N.; Kirkland, T. N.; Cole, G. T.; Birren, B. W.; Henn, M. R.; Taylor, J. W.; Rounsley, S. D. Population genomic sequencing of Coccidioides fungi reveals recent hybridization and transposon control. Genome Res 2010, 20, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelsen, M. P.; Moreau, C. S.; Boyce, C. Kevin; Ree, R. H. Macroecological diversification of ants is linked to angiosperm evolution. Evolution Letters 2023, 7, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveros, C. H.; Field, D. J.; Ksepka, D. T.; Barker, F. K.; Aleixo, A.; Andersen, M. J.; Alström, P.; Benz, B. W.; Braun, E. L.; Braun, M. J.; Bravo, G. A.; Brumfield, R. T.; Chesser, R. T.; Claramunt, S.; Cracraft, J.; Cuervo, A. M.; Derryberry, E. P.; Glenn, T. C.; Harvey, M. G.; Hosner, P. A.; Joseph, L.; Kimball, R. T.; Mack, A. L.; Miskelly, C. M.; Peterson, A. T.; Robbins, M. B.; Sheldon, F. H.; Silveira, L. F.; Smith, B. T.; White, N. D.; Moyle, R. G.; Faircloth, B. C. Earth history and the passerine superradiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2019, 116, 7916–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative. 2019. One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants. Nature 574, 679–685.

- Opulente, D. A.; LaBella, A. L.; Harrison, M.-C.; Wolters, J. F.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Kominek, J.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Stoneman, H. R.; VanDenAvond, J.; Miller, C. R.; Langdon, Q. K.; Silva, M.; Gon#xE7alves, C.; Ubbelohde, E. J.; Li, Y.; Buh, K. V.; Jarzyna, M.; Haase, M. A. B.; Rosa, C. A.; #x10Cadež, N.; Libkind, D.; DeVirgilio, J. H.; Hulfachor, A. B.; Kurtzman, C. P.; Sampaio, J. P.; Gon#xE7alves, P.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X.-X.; Groenewald, M.; Rokas, A.; Hittinger, C. T. 2023. Genomic and ecological factors shaping specialism and generalism across an entire subphylum. Evolutionary Biology.

- Ortiz-Merino, R. A.; Kuanyshev, N.; Braun-Galleani, S.; Byrne, K. P.; Porro, D.; Branduardi, P.; Wolfe, K. H. Evolutionary restoration of fertility in an interspecies hybrid yeast, by whole-genome duplication after a failed mating-type switch. PLoS Biol 2017, 15, e2002128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanski, A. B.; Paulat, N. S.; Korstian, J.; Grimshaw, J. R.; Halsey, M.; Sullivan, K. A. M.; Moreno-Santillán, D. D.; Crookshanks, C.; Roberts, J.; Garcia, C.; Johnson, M. G.; Densmore, L. D.; Stevens, R. D.; Consortium†, Zoonomia; Rosen, J.; Storer, J. M.; Hubley, R.; Smit, A. F. A.; Dávalos, L. M.; Karlsson, E. K.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Ray, D. A.; Andrews, G.; Armstrong, J. C.; Bianchi, M.; Birren, B. W.; Bredemeyer, K. R.; Breit, A. M.; Christmas, M. J.; Clawson, H.; Damas, J.; Palma, F. Di; Diekhans, M.; Dong, M. X.; Eizirik, E.; Fan, K.; Fanter, C.; Foley, N. M.; Forsberg-Nilsson, K.; Garcia, C. J.; Gatesy, J.; Gazal, S.; Genereux, D. P.; Goodman, L.; Grimshaw, J.; Halsey, M. K.; Harris, A. J.; Hickey, G.; Hiller, M.; Hindle, A. G.; Hubley, R. M.; Hughes, G. M.; Johnson, J.; Juan, D.; Kaplow, I. M.; Karlsson, E. K.; Keough, K. C.; Kirilenko, B.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Korstian, J. M.; Kowalczyk, A.; Kozyrev, S. V.; Lawler, A. J.; Lawless, C.; Lehmann, T.; Levesque, D. L.; Lewin, H. A.; Li, X.; Lind, A.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Mackay-Smith, A.; Marinescu, V. D.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Mason, V. C.; Meadows, J. R. S.; Meyer, W. K.; Moore, J. E.; Moreira, L. R.; Moreno-Santillan, D. D.; Morrill, K. M.; Muntané, G.; Murphy, W. J.; Navarro, A.; Nweeia, M.; Ortmann, S.; Osmanski, A.; Paten, B.; Paulat, N. S.; Pfenning, A. R.; Phan, B. N.; Pollard, K. S.; Pratt, H. E.; Ray, D. A.; Reilly, S. K.; Rosen, J. R.; Ruf, I.; Ryan, L.; Ryder, O. A.; Sabeti, P. C.; Schäffer, D. E.; Serres, A.; Shapiro, B.; Smit, A. F. A.; Springer, M.; Srinivasan, C.; Steiner, C.; Storer, J. M.; Sullivan, K. A. M.; Sullivan, P. F.; Sundström, E.; Supple, M. A.; Swofford, R.; Talbot, J.-E.; Teeling, E.; Turner-Maier, J.; Valenzuela, A.; Wagner, F.; Wallerman, O.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Weng, Z.; Wilder, A. P.; Wirthlin, M. E.; Xue, J. R.; Zhang, X. Insights into mammalian TE diversity through the curation of 248 genome assemblies. Science 2023, 380, eabn1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, O.; Suhre, K.; Abergel, C.; Higgins, D. G.; Notredame, C. 3DCoffee: combining protein sequences and structures within multiple sequence alignments. Journal of molecular biology 2004, 340, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, H.; Levy, A. A.; Feldman, M. Allopolyploidy-Induced Rapid Genome Evolution in the Wheat ( Aegilops – Triticum ) Group. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parey, E.; Louis, A.; Montfort, J.; Bouchez, O.; Roques, C.; Iampietro, C.; Lluch, J.; Castinel, A.; Donnadieu, C.; Desvignes, T.; Bucao, C. Floi; Jouanno, E.; Wen, M.; Mejri, S.; Dirks, R.; Jansen, H.; Henkel, C.; Chen, W.-J.; Zahm, M.; Cabau, C.; Klopp, C.; Thompson, A. W.; Robinson-Rechavi, M.; Braasch, I.; Lecointre, G.; Bobe, J.; Postlethwait, J. H.; Berthelot, C.; Crollius, H. R.; Guiguen, Y. Genome structures resolve the early diversification of teleost fishes. Science 2023, 379, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parham, J. F.; Donoghue, P. C. J.; Bell, C. J.; Calway, T. D.; Head, J. J.; Holroyd, P. A.; Inoue, J. G.; Irmis, R. B.; Joyce, W. G.; Ksepka, D. T.; Patané, J. S. L.; Smith, N. D.; Tarver, J. E.; Tuinen, M. Van; Yang, Z.; Angielczyk, K. D.; Greenwood, J. M.; Hipsley, C. A.; Jacobs, L.; Makovicky, P. J.; Müller, J.; Smith, K. T.; Theodor, J. M.; Warnock, R. C. M.; Benton, M. J. Best Practices for Justifying Fossil Calibrations. Systematic Biology 2012, 61, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D. H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D. W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pease, J. B.; Hahn, M. W. Detection and Polarization of Introgression in a Five-Taxon Phylogeny. Systematic Biology 2015, 64, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B. K.; Weber, J. N.; Kay, E. H.; Fisher, H. S.; Hoekstra, H. E. Double Digest RADseq: An Inexpensive Method for De Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping in Model and Non-Model Species. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. A.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. Examination of Gene Loss in the DNA Mismatch Repair Pathway and Its Mutational Consequences in a Fungal Phylum. Genome Biology and Evolution 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. J.; Penny, D. The root of the mammalian tree inferred from whole mitochondrial genomes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2003, 28, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipes, L.; Wang, H.; Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Nielsen, R. Assessing Uncertainty in the Rooting of the SARS-CoV-2 Phylogeny. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D. D.; Zwickl, D. J.; McGuire, J. A.; Hillis, D. M. Increased Taxon Sampling Is Advantageous for Phylogenetic Inference. Systematic Biology 2002, 51, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Toledo, R. I.; Moreira, D.; López-García, P.; Deschamps, P. Secondary Plastids of Euglenids and Chlorarachniophytes Function with a Mix of Genes of Red and Green Algal Ancestry. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 2198–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q. Q. Genetic admixture accelerates invasion via provisioning rapid adaptive evolution. Mol Ecol 2019, 28, 4012–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racimo, F.; Sankararaman, S.; Nielsen, R.; Huerta-Sánchez, E. Evidence for archaic adaptive introgression in humans. Nature Reviews Genetics 2015, 16, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghava, G.; Searle, S. M.; Audley, P. C.; Barber, J. D.; Barton, G. J. OXBench: A benchmark for evaluation of protein multiple sequence alignment accuracy. BMC Bioinformatics 2003, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranwez, V.; Douzery, E. J. P.; Cambon, C.; Chantret, N.; Delsuc, F. MACSE v2: Toolkit for the Alignment of Coding Sequences Accounting for Frameshifts and Stop Codons. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 2582–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, A. K.; Casey, D.; Gundappa, M. K.; Macqueen, D. J.; McLysaght, A. Independent rediploidization masks shared whole genome duplication in the sturgeon-paddlefish ancestor. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, D.; Patterson, N.; Campbell, D.; Tandon, A.; Mazieres, S.; Ray, N.; Parra, M. V.; Rojas, W.; Duque, C.; Mesa, N. Reconstructing native American population history. Nature 2012, 488, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieseberg, L. H.; Kim, S.-C.; Randell, R. A.; Whitney, K. D.; Gross, B. L.; Lexer, C.; Clay, K. Hybridization and the colonization of novel habitats by annual sunflowers. Genetica 2007, 129, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N.; Brinkmann, H.; Roure, B.; Lartillot, N.; Lang, B. F.; Philippe, H. Detecting and overcoming systematic errors in genome-scale phylogenies. Systematic biology 2007, 56, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokas, A.; Holland, P. W. H. Rare genomic changes as a tool for phylogenetics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2000, 15, 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- Rokas, A.; Williams, B. L.; King, N.; Carroll, S. B. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature 2003, 425, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Mark, P. Van Der; Ayres, D. L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M. A.; Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Systematic Biology 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropars, J.; Vega, R. C. Rodríguez de la; López-Villavicencio, M.; Gouzy, J.; Sallet, E.; Dumas, É; Lacoste, S.; Debuchy, R.; Dupont, J.; Branca, A.; Giraud, T. Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology 2015, 25, 2562–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Meseguer, A.; Condamine, F. L. Ancient tropical extinctions at high latitudes contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient*. Evolution 2020, 74, 1966–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina Pankey, M.; Plachetzki, D. C.; Macartney, K. J.; Gastaldi, M.; Slattery, M.; Gochfeld, D. J.; Lesser, M. P. Cophylogeny and convergence shape holobiont evolution in sponge–microbe symbioses. Nat Ecol Evol 2022, 6, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salichos, L.; Rokas, A. Inferring ancient divergences requires genes with strong phylogenetic signals. Nature 2013, 497, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salichos, L.; Stamatakis, A.; Rokas, A. Novel Information Theory-Based Measures for Quantifying Incongruence among Phylogenetic Trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2014, 31, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, M. J. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararaman, S.; Mallick, S.; Patterson, N.; Reich, D. The combined landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Current Biology 2016, 26, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyari, E.; Mirarab, S. Testing for Polytomies in Phylogenetic Species Trees Using Quartet Frequencies. Genes 2018, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, D. R.; Byrne, K. P.; Gordon, J. L.; Wong, S.; Wolfe, K. H. Multiple rounds of speciation associated with reciprocal gene loss in polyploid yeasts. Nature 2006, 440, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, J. J. Consequences of Secondary Calibrations on Divergence Time Estimates. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmieder, R.; Edwards, R. Fast Identification and Removal of Sequence Contamination from Genomic and Metagenomic Datasets. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönknecht, G.; Chen, W.-H.; Ternes, C. M.; Barbier, G. G.; Shrestha, R. P.; Stanke, M.; Bräutigam, A.; Baker, B. J.; Banfield, J. F.; Garavito, R. M.; Carr, K.; Wilkerson, C.; Rensing, S. A.; Gagneul, D.; Dickenson, N. E.; Oesterhelt, C.; Lercher, M. J.; Weber, A. P. M. Gene Transfer from Bacteria and Archaea Facilitated Evolution of an Extremophilic Eukaryote. Science 2013, 339, 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, M.; Marcussen, T.; Meseguer, A. S.; Fjellheim, S. The grass subfamily Pooideae: Cretaceous–Palaeocene origin and climate-driven Cenozoic diversification. Global Ecol Biogeogr 2019, geb.12923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D. T.; Haddock, S. H. D.; Bredeson, J. V.; Green, R. E.; Simakov, O.; Rokhsar, D. S. Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals. Nature 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Session, A. M.; Rokhsar, D. S. Transposon signatures of allopolyploid genome evolution. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Session, A. M.; Uno, Y.; Kwon, T.; Chapman, J. A.; Toyoda, A.; Takahashi, S.; Fukui, A.; Hikosaka, A.; Suzuki, A.; Kondo, M.; Heeringen, S. J. Van; Quigley, I.; Heinz, S.; Ogino, H.; Ochi, H.; Hellsten, U.; Lyons, J. B.; Simakov, O.; Putnam, N.; Stites, J.; Kuroki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Michiue, T.; Watanabe, M.; Bogdanovic, O.; Lister, R.; Georgiou, G.; Paranjpe, S. S.; Kruijsbergen, I. Van; Shu, S.; Carlson, J.; Kinoshita, T.; Ohta, Y.; Mawaribuchi, S.; Jenkins, J.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Mitros, T.; Mozaffari, S. V.; Suzuki, Y.; Haramoto, Y.; Yamamoto, T. S.; Takagi, C.; Heald, R.; Miller, K.; Haudenschild, C.; Kitzman, J.; Nakayama, T.; Izutsu, Y.; Robert, J.; Fortriede, J.; Burns, K.; Lotay, V.; Karimi, K.; Yasuoka, Y.; Dichmann, D. S.; Flajnik, M. F.; Houston, D. W.; Shendure, J.; DuPasquier, L.; Vize, P. D.; Zorn, A. M.; Ito, M.; Marcotte, E. M.; Wallingford, J. B.; Ito, Y.; Asashima, M.; Ueno, N.; Matsuda, Y.; Veenstra, G. J. C.; Fujiyama, A.; Harland, R. M.; Taira, M.; Rokhsar, D. S. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature 2016, 538, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, S. Fast and accurate bootstrap confidence limits on genome-scale phylogenies using little bootstraps. Nat Comput Sci 2021, 1, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, S.; Graur, D. Playing chicken ( Gallus gallus ): methodological inconsistencies of molecular divergence date estimates due to secondary calibration points. Gene 2002, 300, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.-X.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Contentious relationships in phylogenomic studies can be driven by a handful of genes. Nat Ecol Evol 2017, 1, 0126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.-X.; Opulente, D. A.; Kominek, J.; Zhou, X.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Buh, K. V.; Haase, M. A. B.; Wisecaver, J. H.; Wang, M.; Doering, D. T.; Boudouris, J. T.; Schneider, R. M.; Langdon, Q. K.; Ohkuma, M.; Endoh, R.; Takashima, M.; Manabe, R.; Čadež, N.; Libkind, D.; Rosa, C. A.; DeVirgilio, J.; Hulfachor, A. B.; Groenewald, M.; Kurtzman, C. P.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Tempo and Mode of Genome Evolution in the Budding Yeast Subphylum. Cell 2018, 175, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.-X.; Salichos, L.; Rokas, A. A Genome-Scale Investigation of How Sequence, Function, and Tree-Based Gene Properties Influence Phylogenetic Inference. Genome Biol Evol 2016, 8, 2565–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.-X.; Steenwyk, J. L.; LaBella, A. L.; Opulente, D. A.; Zhou, X.; Kominek, J.; Li, Y.; Groenewald, M.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Genome-scale phylogeny and contrasting modes of genome evolution in the fungal phylum Ascomycota. Sci. Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.-X.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Rokas, A. Dissecting Incongruence between Concatenation- and Quartet-Based Approaches in Phylogenomic Data. Systematic Biology 2021, 70, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimodaira, H.; Hasegawa, M. Multiple Comparisons of Log-Likelihoods with Applications to Phylogenetic Inference. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1999, 16, 1114–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si Quang, L.; Gascuel, O.; Lartillot, N. Empirical profile mixture models for phylogenetic reconstruction. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2317–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbald, S. J.; Archibald, J. M. Genomic Insights into Plastid Evolution. Genome Biology and Evolution 2020, 12, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbald, S. J.; Eme, L.; Archibald, J. M.; Roger, A. J. Lateral Gene Transfer Mechanisms and Pan-genomes in Eukaryotes. Trends in Parasitology 2020, 36, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Patev, S.; Min, B.; Naranjo-Ortiz, M.; Looney, B.; Konkel, Z.; Slot, J. C.; Sakamoto, Y.; Steenwyk, J. L.; Rokas, A.; Carro, J.; Camarero, S.; Ferreira, P.; Molpeceres, G.; Ruiz-Dueñas, F. J.; Serrano, A.; Henrissat, B.; Drula, E.; Hughes, K. W.; Mata, J. L.; Ishikawa, N. K.; Vargas-Isla, R.; Ushijima, S.; Smith, C. A.; Donoghue, J.; Ahrendt, S.; Andreopoulos, W.; He, G.; LaButti, K.; Lipzen, A.; Ng, V.; Riley, R.; Sandor, L.; Barry, K.; Martínez, A. T.; Xiao, Y.; Gibbons, J. G.; Terashima, K.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Hibbett, D. A global phylogenomic analysis of the shiitake genus Lentinula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2023, 120, e2214076120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D. G. QuanTest2: benchmarking multiple sequence alignments using secondary structure prediction. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simion, P.; Philippe, H.; Baurain, D.; Jager, M.; Richter, D. J.; Franco, A. Di; Roure, B.; Satoh, N.; Quéinnec, É; Ereskovsky, A.; Lapébie, P.; Corre, E.; Delsuc, F.; King, N.; Wörheide, G.; Manuel, M. A Large and Consistent Phylogenomic Dataset Supports Sponges as the Sister Group to All Other Animals. Current Biology 2017, 27, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonti, C. N.; Vernot, B.; Bastarache, L.; Bottinger, E.; Carrell, D. S.; Chisholm, R. L.; Crosslin, D. R.; Hebbring, S. J.; Jarvik, G. P.; Kullo, I. J.; Li, R.; Pathak, J.; Ritchie, M. D.; Roden, D. M.; Verma, S. S.; Tromp, G.; Prato, J. D.; Bush, W. S.; Akey, J. M.; Denny, J. C.; Capra, J. A. The phenotypic legacy of admixture between modern humans and Neandertals. Science 2016, 351, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M. L.; Vanderpool, D.; Hahn, M. W. Using all Gene Families Vastly Expands Data Available for Phylogenomic Inference. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. A.; O’Meara, B. C. treePL: divergence time estimation using penalized likelihood for large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2689–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.; Neiva, J.; Martins, N.; Jacinto, R.; Anderson, L.; Raimondi, P. T.; Serrão, E. A.; Pearson, G. A. Increased evolutionary rates and conserved transcriptional response following allopolyploidization in brown algae: GENOME EVOLUTION IN ALLOPOLYPLOID ALGAE. Evolution 2019, 73, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, T.; Pybus, O. G.; Stumpf, M. P. H. Phylodynamics for cell biologists. Science 2021, 371, eaah6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, T.; Yang, Z. Dating Phylogenies with Sequentially Sampled Tips. Systematic Biology 2013, 62, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A.; Hoover, P.; Rougemont, J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Systematic Biology 2008, 57, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, M.; Keller, O.; Gunduz, I.; Hayes, A.; Waack, S.; Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34, W435–W439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J.; King, N. From Genes to Genomes: Opportunities and Challenges for Synteny-based Phylogenies. Preprints; 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Balamurugan, C.; Raja, H. A.; Gon#xE7alves, C.; Li, N.; Martin, F.; Berman, J.; Oberlies, N. H.; Gibbons, J. G.; Goldman, G. H.; Geiser, D. M.; Hibbett, D. S.; Rokas, A. Phylogenomics reveals extensive misidentification of fungal strains from the genus Aspergillus. Evolutionary Biology 2022a. [Google Scholar]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Buida, T. J.; Gonçalves, C.; Goltz, D. C.; Morales, G.; Mead, M. E.; LaBella, A. L.; Chavez, C. M.; Schmitz, J. E.; Hadjifrangiskou, M.; Li, Y.; Rokas, A. BioKIT: a versatile toolkit for processing and analyzing diverse types of sequence data. Genetics 2022b, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Buida, T. J.; Labella, A. L.; Li, Y.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. PhyKIT: a broadly applicable UNIX shell toolkit for processing and analyzing phylogenomic data. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2325–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Buida, T. J.; Li, Y.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. ClipKIT: A multiple sequence alignment trimming software for accurate phylogenomic inference. PLoS Biol 2020a, 18, e3001007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Goltz, D. C.; Buida, T. J.; Li, Y.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. OrthoSNAP: A tree splitting and pruning algorithm for retrieving single-copy orthologs from gene family trees. PLoS Biol 2022c, 20, e3001827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Knowles, S. L.; Bastos, R.; Balamurugan, C.; Rinker, D.; Mead, M. E.; Roberts, C. D.; Raja, H. A.; Li, Y.; Colabardini, A. C.; Castro, P. A.; Reis, T. F.; Canovas, D.; Sanchez, R. L.; Lagrou, K.; Torrado, E.; Rodrigues, F.; Oberlies, N. H.; Zhou, X.; Goldman, G.; Rokas, A. Evolutionary origin, population diversity, and diagnostics for a cryptic hybrid pathogen. Evolutionary Biology 2023a. [Google Scholar]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. Incongruence in the phylogenomics era. Nature Reviews Genetics 2023b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Lind, A. L.; Ries, L. N. A.; Reis, T. F. dos; Silva, L. P.; Almeida, F.; Bastos, R. W.; Silva, T. F. de C. Fraga da; Bonato, V. L. D.; Pessoni, A. M.; Rodrigues, F.; Raja, H. A.; Knowles, S. L.; Oberlies, N. H.; Lagrou, K.; Goldman, G. H.; Rokas, A. Pathogenic Allodiploid Hybrids of Aspergillus Fungi. Current Biology 2020b, 30, 2495–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Opulente, D. A.; Kominek, J.; Shen, X.-X.; Zhou, X.; Labella, A. L.; Bradley, N. P.; Eichman, B. F.; Čadež, N.; Libkind, D.; DeVirgilio, J.; Hulfachor, A. B.; Kurtzman, C. P.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Extensive loss of cell-cycle and DNA repair genes in an ancient lineage of bipolar budding yeasts. PLoS Biol 2019a, 17, e3000255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Phillips, M. A.; Yang, F.; Date, S. S.; Graham, T. R.; Berman, J.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. An orthologous gene coevolution network provides insight into eukaryotic cellular and genomic structure and function. Sci. Adv 2022d, 8, eabn0105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Rokas, A. orthofisher: a broadly applicable tool for automated gene identification and retrieval. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics 2021, 11, jkab250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Rokas, A. The dawn of relaxed phylogenetics. PLoS Biol 2023, 21, e3001998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; Shen, X.-X.; Lind, A. L.; Goldman, G. H.; Rokas, A. A Robust Phylogenomic Time Tree for Biotechnologically and Medically Important Fungi in the Genera Aspergillus and Penicillium. mBio 2019b, 10, e00925–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, J. W.; Schreiber, J.; Yue, J.; Guo, H.; Ding, Q.; Huang, J. The evolution of photosynthesis in chromist algae through serial endosymbioses. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strassert, J. F. H.; Irisarri, I.; Williams, T. A.; Burki, F. A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukenbrock, E. H. The Role of Hybridization in the Evolution and Emergence of New Fungal Plant Pathogens. Phytopathology® 2016, 106, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, A.; Kim, B. Y.; Wang, J.; Armstrong, E. E.; Peede, D.; D’Agostino, E. R. R.; Price, D. K.; Waddell, P. J.; Lang, M.; Courtier-Orgogozo, V.; David, J. R.; Petrov, D.; Matute, D. R.; Schrider, D. R.; Comeault, A. A. Widespread introgression across a phylogeny of 155 Drosophila genomes. Current Biology 2022, 32, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahon, G.; Geesink, P.; Ettema, T. J. G. Expanding Archaeal Diversity and Phylogeny: Past, Present, and Future. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 2021, 75, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, G.; Castresana, J. Improvement of Phylogenies after Removing Divergent and Ambiguously Aligned Blocks from Protein Sequence Alignments. Systematic Biology 2007, 56, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Muffato, M.; Ledergerber, C.; Herrero, J.; Goldman, N.; Gil, M.; Dessimoz, C. Current Methods for Automated Filtering of Multiple Sequence Alignments Frequently Worsen Single-Gene Phylogenetic Inference. Syst Biol 2015, 64, 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Q.; Tamura, K.; Kumar, S. Efficient Methods for Dating Evolutionary Divergences. Pp. 197–219 in S. Y. W. Ho, ed. The Molecular Evolutionary Clock. Springer International Publishing, Cham. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D.; Plewniak, F.; Poch, O. BAliBASE: a benchmark alignment database for the evaluation of multiple alignment programs. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 1999, 15, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiley, G. P.; Flouri, T.; Jiao, X.; Poelstra, J. W.; Xu, B.; Zhu, T.; Rannala, B.; Yoder, A. D.; Yang, Z. Estimation of species divergence times in presence of cross-species gene flow. Systematic Biology 2023, 72, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiley, G. P.; Poelstra, J. W.; Reis, M. Dos; Yang, Z.; Yoder, A. D. Molecular Clocks without Rocks: New Solutions for Old Problems. Trends in Genetics 2020, 36, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upham, N. S.; Esselstyn, J. A.; Jetz, W. Inferring the mammal tree: Species-level sets of phylogenies for questions in ecology, evolution, and conservation. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upham, N. S.; Esselstyn, J. A.; Jetz, W. Molecules and fossils tell distinct yet complementary stories of mammal diversification. Current Biology 2021, 31, 4195–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D. J.; Meier, R. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, S. Graph Clustering Via a Discrete Uncoupling Process. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. & Appl 2008, 30, 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten, J.; Bhattacharya, D. Horizontal Gene Transfer in Eukaryotes: Not if, but How Much? Trends in Genetics 2020, 36, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, E. M.; Koelle, K.; Bedford, T. Viral Phylodynamics. PLoS Comput Biol 2013, 9, e1002947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Minh, B. Q.; Susko, E.; Roger, A. J. Modeling Site Heterogeneity with Posterior Mean Site Frequency Profiles Accelerates Accurate Phylogenomic Estimation. Systematic Biology 2018a, 67, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-S.; Murray, G. G. R.; Mann, D.; Groves, P.; Vershinina, A. O.; Supple, M. A.; Kapp, J. D.; Corbett-Detig, R.; Crump, S. E.; Stirling, I.; Laidre, K. L.; Kunz, M.; Dalén, L.; Green, R. E.; Shapiro, B. A polar bear paleogenome reveals extensive ancient gene flow from polar bears into brown bears. Nat Ecol Evol 2022, 6, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Cai, Y. A benchmark study of sequence alignment methods for protein clustering. BMC Bioinformatics 2018b, 19, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, R. M.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F. A.; Manni, M.; Ioannidis, P.; Klioutchnikov, G.; Kriventseva, E. V.; Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO Applications from Quality Assessments to Gene Prediction and Phylogenomics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, C. M.; Murray, A. W.; Eddy, S. R. Many, but not all, lineage-specific genes can be explained by homology detection failure. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickett, N. J.; Mirarab, S.; Nguyen, N.; Warnow, T.; Carpenter, E.; Matasci, N.; Ayyampalayam, S.; Barker, M. S.; Burleigh, J. G.; Gitzendanner, M. A.; Ruhfel, B. R.; Wafula, E.; Der, J. P.; Graham, S. W.; Mathews, S.; Melkonian, M.; Soltis, D. E.; Soltis, P. S.; Miles, N. W.; Rothfels, C. J.; Pokorny, L.; Shaw, A. J.; DeGironimo, L.; Stevenson, D. W.; Surek, B.; Villarreal, J. C.; Roure, B.; Philippe, H.; dePamphilis, C. W.; Chen, T.; Deyholos, M. K.; Baucom, R. S.; Kutchan, T. M.; Augustin, M. M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Yan, Z.; Wu, X.; Sun, X.; Wong, G. K.-S.; Leebens-Mack, J. Phylotranscriptomic analysis of the origin and early diversification of land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J. J.; Tiu, J. Highly Incomplete Taxa Can Rescue Phylogenetic Analyses from the Negative Impacts of Limited Taxon Sampling. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. A.; Cox, C. J.; Foster, P. G.; Szöllősi, G. J.; Embley, T. M. Phylogenomics provides robust support for a two-domains tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol 2019, 4, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, J.; Roddur, M. S.; Liu, B.; Zaharias, P.; Warnow, T. DISCO: Species Tree Inference using Multicopy Gene Family Tree Decomposition. Systematic Biology 2022, 71, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worobey, M.; Watts, T. D.; McKay, R. A.; Suchard, M. A.; Granade, T.; Teuwen, D. E.; Koblin, B. A.; Heneine, W.; Lemey, P.; Jaffe, H. W. 1970s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America. Nature 2016, 539, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Rannala, B. Bayesian species delimitation using multilocus sequence data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 9264–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Barnett, R. M.; Nakhleh, L. Parsimonious Inference of Hybridization in the Presence of Incomplete Lineage Sorting. Systematic Biology 2013, 62, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Lu, H.; Li, F.; Nielsen, J.; Kerkhoven, E. J. HGTphyloDetect: facilitating the identification and phylogenetic analysis of horizontal gene transfer. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24, bbad035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Hu, X.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J. Widespread impact of horizontal gene transfer on plant colonization of land. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanewich, K. P.; Pearce, D. W.; Rood, S. B. Heterosis in poplar involves phenotypic stability: cottonwood hybrids outperform their parental species at suboptimal temperatures. Tree Physiology 2018, 38, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeberg, H.; Pääbo, S. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. Nature 2020, 587, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Rabiee, M.; Sayyari, E.; Mirarab, S. ASTRAL-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Scornavacca, C.; Molloy, E. K.; Mirarab, S. ASTRAL-Pro: Quartet-Based Species-Tree Inference despite Paralogy. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37, 3292–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Braun, E. L.; Mirarab, S. TAPER: Pinpointing errors in multiple sequence alignments despite varying rates of evolution. Methods Ecol Evol 2021, 12, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Li, B.; Larkin, D. M.; Lee, C.; Storz, J. F.; Antunes, A.; Greenwold, M. J.; Meredith, R. W.; Ödeen, A.; Cui, J.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, L.; Pan, H.; Wang, Z.; Jin, L.; Zhang, P.; Hu, H.; Yang, W.; Hu, J.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Yu, H.; Lian, J.; Wen, P.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Z.; An, N.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Fonseca, R. R. Da; Alfaro-Núñez, A.; Schubert, M.; Orlando, L.; Mourier, T.; Howard, J. T.; Ganapathy, G.; Pfenning, A.; Whitney, O.; Rivas, M. V.; Hara, E.; Smith, J.; Farré, M.; Narayan, J.; Slavov, G.; Romanov, M. N.; Borges, R.; Machado, J. P.; Khan, I.; Springer, M. S.; Gatesy, J.; Hoffmann, F. G.; Opazo, J. C.; Håstad, O.; Sawyer, R. H.; Kim, H.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, H. J.; Cho, S.; Li, N.; Huang, Y.; Bruford, M. W.; Zhan, X.; Dixon, A.; Bertelsen, M. F.; Derryberry, E.; Warren, W.; Wilson, R. K.; Li, S.; Ray, D. A.; Green, R. E.; O’Brien, S. J.; Griffin, D.; Johnson, W. E.; Haussler, D.; Ryder, O. A.; Willerslev, E.; Graves, G. R.; Alström, P.; Fjeldså, J.; Mindell, D. P.; Edwards, S. V.; Braun, E. L.; Rahbek, C.; Burt, D. W.; Houde, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Consortium, Avian Genome; Jarvis, E. D.; Gilbert, M. T. P.; Wang, J.; Ye, C.; Liang, S.; Yan, Z.; Zepeda, M. L.; Campos, P. F.; Velazquez, A. M. V.; Samaniego, J. A.; Avila-Arcos, M.; Martin, M. D.; Barnett, R.; Ribeiro, A. M.; Mello, C. V.; Lovell, P. V.; Almeida, D.; Maldonado, E.; Pereira, J.; Sunagar, K.; Philip, S.; Dominguez-Bello, M. G.; Bunce, M.; Lambert, D.; Brumfield, R. T.; Sheldon, F. H.; Holmes, E. C.; Gardner, P. P.; Steeves, T. E.; Stadler, P. F.; Burge, S. W.; Lyons, E.; Smith, J.; McCarthy, F.; Pitel, F.; Rhoads, D.; Froman, D. P. Comparative genomics reveals insights into avian genome evolution and adaptation. Science 2014a, 346, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ou, H.-Y.; Gao, F.; Luo, H. Identification of Horizontally-transferred Genomic Islands and Genome Segmentation Points by Using the GC Profile Method. CG 2014b, 15, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Janke, A. Gene flow analysis method, the D-statistic, is robust in a wide parameter space. BMC bioinformatics 2018, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Lutteropp, S.; Czech, L.; Stamatakis, A.; Looz, M. V.; Rokas, A. Quartet-Based Computations of Internode Certainty Provide Robust Measures of Phylogenetic Incongruence. Systematic Biology 2020, 69, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Rokas, A. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of high-throughput sequencing data pathologies. Mol Ecol 2014, 23, 1679–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shen, X.-X.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Evaluating Fast Maximum Likelihood-Based Phylogenetic Programs Using Empirical Phylogenomic Data Sets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Kosoy, M.; Dittmar, K. HGTector: an automated method facilitating genome-wide discovery of putative horizontal gene transfers. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Mai, U.; Pfeiffer, W.; Janssen, S.; Asnicar, F.; Sanders, J. G.; Belda-Ferre, P.; Al-Ghalith, G. A.; Kopylova, E.; McDonald, D.; Kosciolek, T.; Yin, J. B.; Huang, S.; Salam, N.; Jiao, J.-Y.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Z. Z.; Cantrell, K.; Yang, Y.; Sayyari, E.; Rabiee, M.; Morton, J. T.; Podell, S.; Knights, D.; Li, W.-J.; Huttenhower, C.; Segata, N.; Smarr, L.; Mirarab, S.; Knight, R. Phylogenomics of 10,575 genomes reveals evolutionary proximity between domains Bacteria and Archaea. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).