Submitted:

11 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

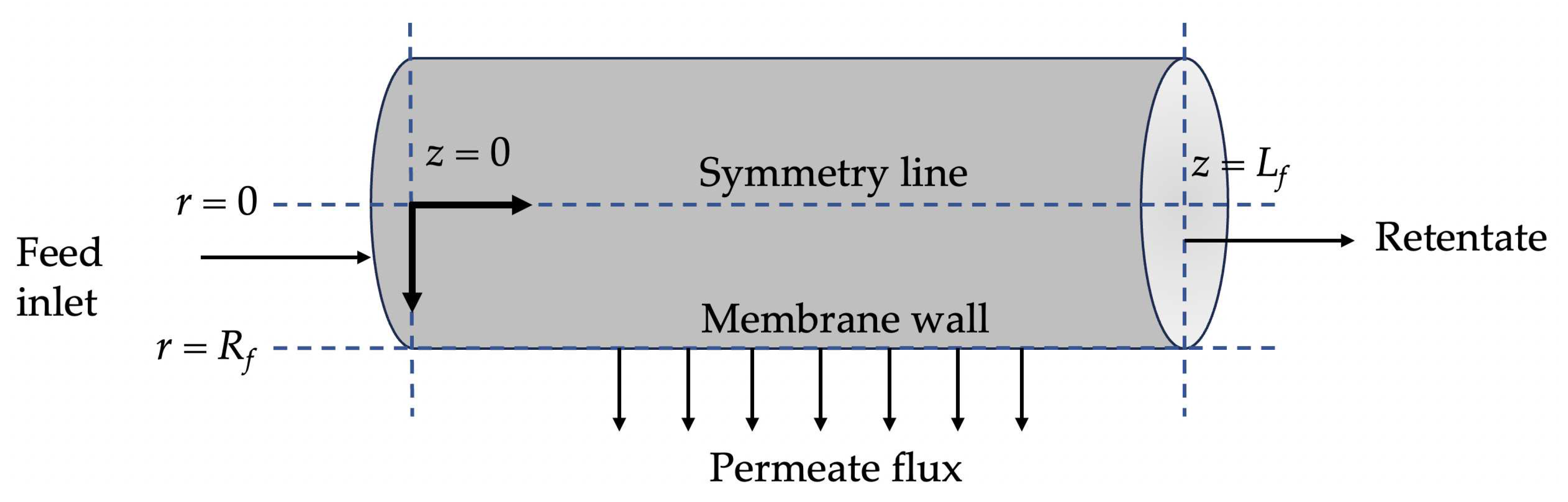

2.1. Governing equations

2.2. Resistance parameters

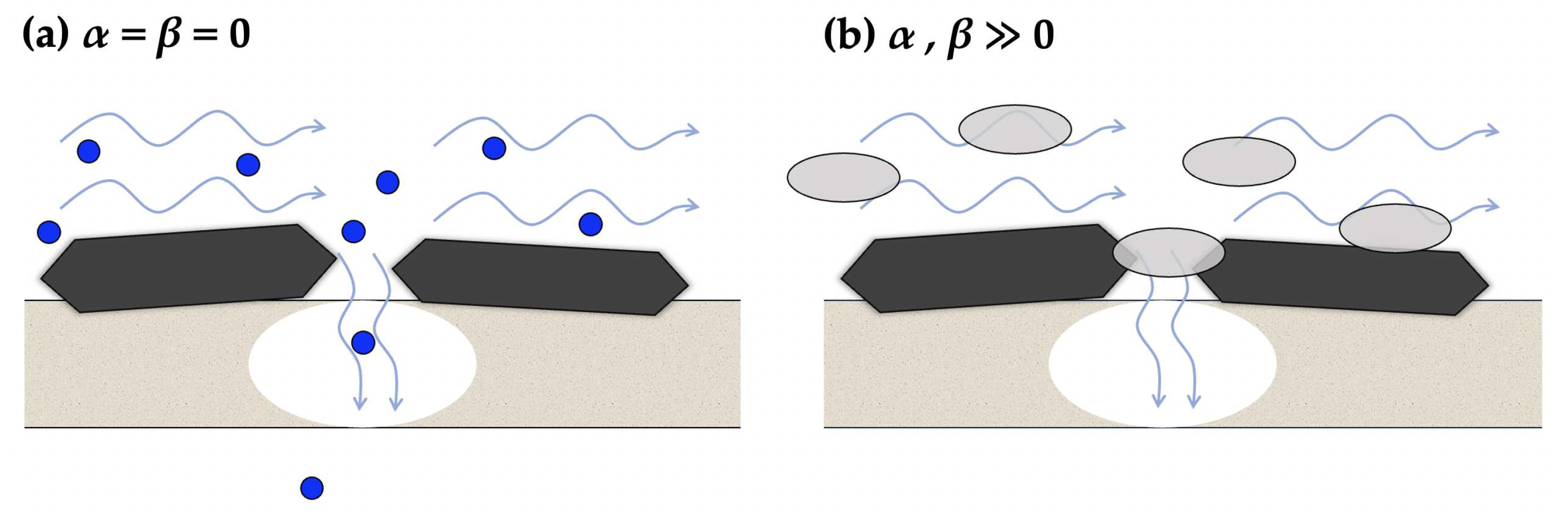

2.3. Permeate flux concentration

3. Results

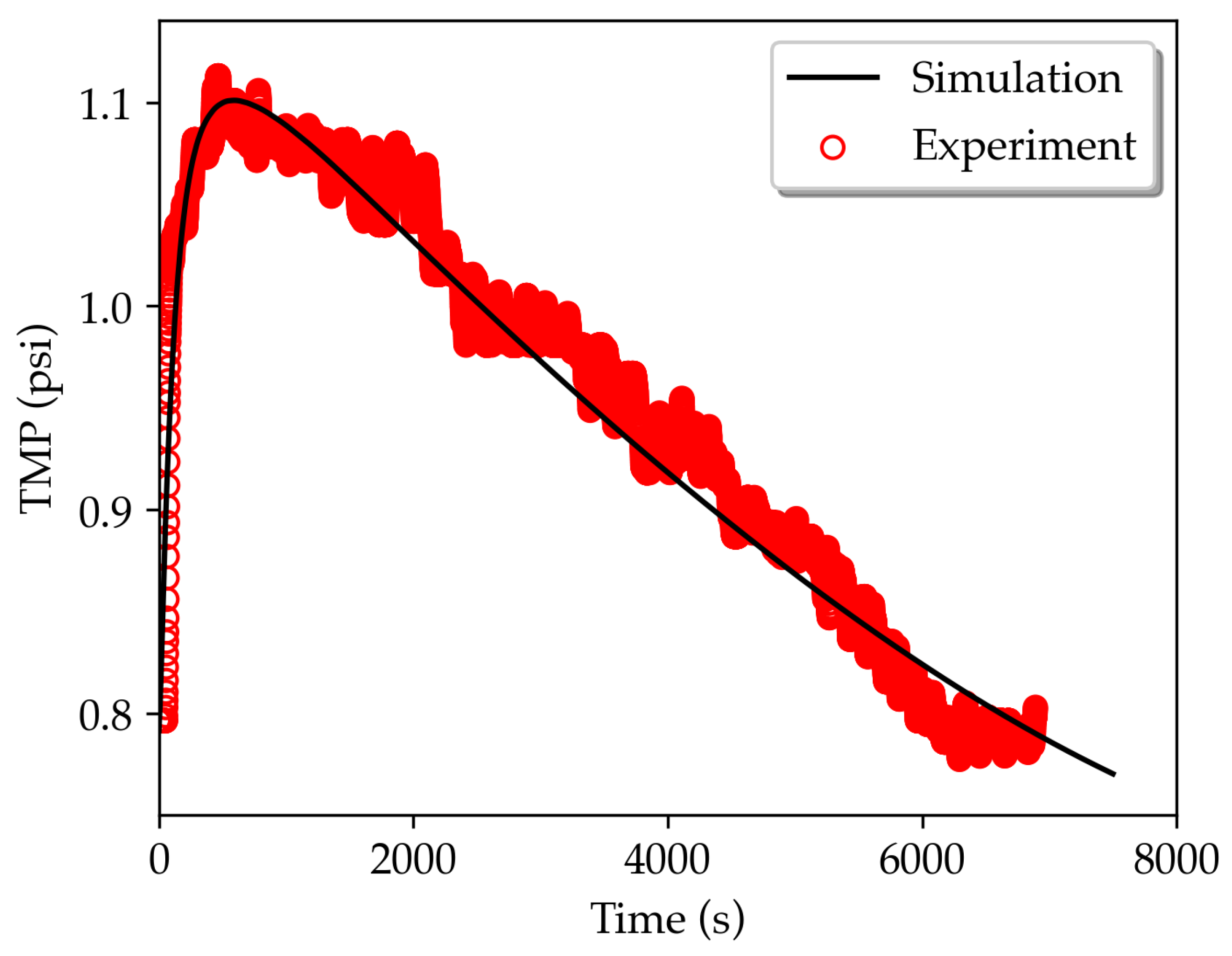

3.1. TMP dynamics

3.2. Permeating particle dynamics

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhao, S.; Zou, L.; Tang, C.Y.; Mulcahy, D. Recent developments in forward osmosis: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Membrane Science 2012, 396, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chung, T.S. Recent advances in membrane distillation processes: Membrane development, configuration design and application exploring. Journal of Membrane Science 2015, 474, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.P.; Godhaniya, M.; Kothari, C. Emerging and advanced membrane technology for wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2022, 62, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasseuguette, E.; Comesaña-Gándara, B. Polymer Membranes for Gas Separation. Membranes 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Niu, Z.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Mu, P.; Li, J. A review on the recent advances in composite membranes for CO2 capture processes. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Khan, K.; Maan, A.; Zia, R.; Giorno, L.; Schroën, K. Membrane separation technology for the recovery of nutraceuticals from food industrial streams. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2019, 86, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conidi, C.; Castro-Muñoz, R.; Cassano, A. Membrane-based operations in the fruit juice processing industry: A review. Beverages 2020, 6, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M.; Vecino, X.; Cortina, J.L. Use of membrane technologies in dairy industry: An overview. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyar, S.; Yoshikawa, H.N.; Mirbod, P. The impact of imposed Couette flow on the stability of pressure-driven flows over porous surfaces. Journal of Engineering Mathematics 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Gao, W.; Meng, F.; Liao, B.Q.; Leung, K.T.; Zhao, L.; Chen, J.; Hong, H. Membrane bioreactors for industrial wastewater treatment: A critical review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2012, 42, 677–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, J.; Ormerod, D.; Theys, G.; Gool, D.V.; Camp, B.V.; Darvishmanesh, S.; der Bruggen, B.V. Towards high resolution membrane-based pharmaceutical separations. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2013, 88, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.P.; Godhaniya, M.; Kothari, C. Emerging and advanced membrane technology for wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2022, 62, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, D.; Matsuura, T. Surface modifications for antifouling membranes. Chemical Reviews 2010, 110, 2448–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.N.; Tang, C.Y. Nanofiltration membrane fouling by oppositely charged macromolecules: Investigation on flux behavior, foulant mass deposition, and solute rejection. Environmental Science and Technology 2011, 45, 8941–8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nthunya, L.N.; Bopape, M.F.; Mahlangu, O.T.; Mamba, B.B.; der Bruggen, B.V.; Quist-Jensen, C.A.; Richards, H. Fouling, performance and cost analysis of membrane-based water desalination technologies: A critical review. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, D.J.; Li, Z.; Baetz, B.W.; Hong, Y.; Donnaz, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, P.; Ding, H.; Dong, Q. Membrane fouling prediction and uncertainty analysis using machine learning: A wastewater treatment plant case study. Journal of Membrane Science 2022, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, M.N.; Mishu, M.R.; Stylios, G.K.; Hasan, S.W.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zarra, T.; Belgiorno, V.; Naddeo, V. Sustainable treatment of food industry wastewater using membrane technology: A short review. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, N.K.; Rohani, R.; Mohammad, A.W.; Isloor, A.M.; Jahim, J.M. Investigation of succinic acid recovery from aqueous solution and fermentation broth using polyimide nanofiltration membrane. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bagley, D.M.; Leung, K.T.; Liss, S.N.; Liao, B.Q. Recent advances in membrane technologies for biorefining and bioenergy production. Biotechnology Advances 2012, 30, 817–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, J.R.; Diaz-Arauzo, S.; Chaney, L.E.; Tsai, D.; Hui, J.; Seo, J.W.T.; Cohen, D.R.; Dango, M.; Zhang, J.; Williams, N.X.; Qian, J.H.; Dunn, J.B.; Hersam, M.C. Centrifuge-Free Separation of Solution-Exfoliated 2D Nanosheets via Cross-Flow Filtration. Advanced Materials 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh, A.R. Membrane Fouling During Hollow Fiber Ultrafiltration of Protein Solutions: Computational Fluid Modeling and Physicochemical Properties 2010.

- Quezada, C.; Estay, H.; Cassano, A.; Troncoso, E.; Ruby-Figueroa, R. Prediction of permeate flux in ultrafiltration processes: A review of modeling approaches. Membranes 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.S.K.; Yea, M.K.; Cheryan, M. Ultrafiltration of soy protein concentrate: Performance and modelling of spiral and tubular polymeric modules. Journal of Membrane Science 2004, 244, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, B.; Moresoli, C.; Skorepova, J.; Vaughan, B. CFD modeling of a transient hollow fiber ultrafiltration system for protein concentration. Journal of Membrane Science 2009, 337, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Bhattacharjee, C. Recovery of Whey Proteins and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lactose Derived from Casein Whey Using a Tangential Flow Ultrafiltration Module. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series E 2013, 94, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; De, S. Purification of Polyphenols from Green Tea Leaves and Performance Prediction Using the Blend Hollow Fiber Ultrafiltration Membrane. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.K.; Liu, L.; Hosseini, P.K.; Lee, K.; Miao, J. Performance evaluation of a pilot-scale membrane filtration system for oily wastewater treatment: CFD modeling and scale-up design. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 52, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.W.; Wu, D.; Howell, J.A.; Gupta, B.B. Critical flux concept for microfiltration fouling. Journal of Membrane Science 1995, 100, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.C.; Zydney, A.L. Transmembrane pressure profiles during constant flux microfiltration of bovine serum albumin. Journal of Membrane Science 2002, 209, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.W.; Pearce, G.K. Critical, sustainable and threshold fluxes for membrane filtration with water industry applications. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2011, 164, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, A.Y.; Cheng, Y.H.; Paul, D.R.; Field, R.W.; Freeman, B.D. Fouling mechanisms in constant flux crossflow ultrafiltration. Journal of Membrane Science 2019, 574, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hube, S.; Hauser, F.; Burkhardt, M.; Brynjólfsson, S.; Wu, B. Ultrasonication-assisted fouling control during ceramic membrane filtration of primary wastewater under gravity-driven and constant flux conditions. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, A.P.; Bergsman, D.S.; Getachew, B.A.; Leahy, L.M.; Patil, J.J.; Ferralis, N.; Grossman, J.C. Highly Conductive and Permeable Nanocomposite Ultrafiltration Membranes Using Laser-Reduced Graphene Oxide. Nano Letters 2021, 21, 2429–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, A.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Bai, L.; Wang, B.; Cheng, X. Evaluations of holey graphene oxide modified ultrafiltration membrane and the performance for water purification. Chemosphere 2021, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sreedhar, N.; Thomas, N.; Mavukkandy, M.; Ismail, R.A.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Arafat, H.A. Polydopamine-coated graphene oxide nanosheets embedded in sulfonated poly(ether sulfone) hybrid UF membranes with superior antifouling properties for water treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhi, F.H.; Singh, M.; Chavan, S.V.; Cao, T.; Shanbedi, M.; Karim, A. Effects of Film Confinement on Dielectric and Electrical Properties of Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Polymer Nanocomposites: Implications for Energy Storage. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Choi, J.; Bang, J.; Lee, J.H. Layer-by-layer assembly of graphene oxide nanosheets on polyamide membranes for durable reverse-osmosis applications. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 2013, 5, 12510–12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chae, H.R.; Won, Y.J.; Lee, K.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, H.H.; Kim, I.C.; min Lee, J. Graphene oxide nanoplatelets composite membrane with hydrophilic and antifouling properties for wastewater treatment. Journal of Membrane Science 2013, 448, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Li, Z.K.; Yan, X.; Guo, Y.J.; Lang, W.Z. Improved ultrafiltration performance and chlorine resistance of PVDF hollow fiber membranes via doping with sulfonated graphene oxide. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 317, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, M.; Allan, N.L.; Cosgrove, T.; George, N. Wetting of water and water/ethanol droplets on a non-polar surface: A molecular dynamics study. Langmuir 2002, 18, 10462–10466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metya, A.K.; Khan, S.; Singh, J.K. Wetting transition of the ethanol-water droplet on smooth and textured surfaces. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2014, 118, 4113–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.H.; Shi, X. Pore fouling of microfiltration membranes by activated sludge. Journal of Membrane Science 2005, 264, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Zhu, L.P.; Xu, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.F.; Ma, X.T.; Zhu, B.K. Polysulfone-based amphiphilic polymer for hydrophilicity and fouling-resistant modification of polyethersulfone membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2010, 365, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; He, B.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H. Experimental investigation of local flux distribution and fouling behavior in double-end and dead-end submerged hollow fiber membrane modules. Journal of Membrane Science 2014, 453, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonalves, F.A.; Trindade, A.R.; Costa, C.S.; Bernardo, J.C.; Johnson, I.; Fonseca, I.M.; Ferreira, A.G. PVT, viscosity, and surface tension of ethanol: New measurements and literature data evaluation. Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2010, 42, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System parameters | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane properties | (mm) | 0.75 |

| (cm) | 33.7 | |

| 20 | ||

| Operating conditions | (mL/min) | 343 |

| (mL/min) | 5 | |

| (m/s) | 0.65 | |

| (m/s) | 5.5×10 | |

| Solute and Solvent properties | (g/L) | 0.3 |

| (Pa·s) | 2 × 10 | |

| (kg/m) | 789 | |

| Resistance parameters | ||

| (s g/L) | 1000 | |

| (s g/L) | ||

| (s) | 2825 | |

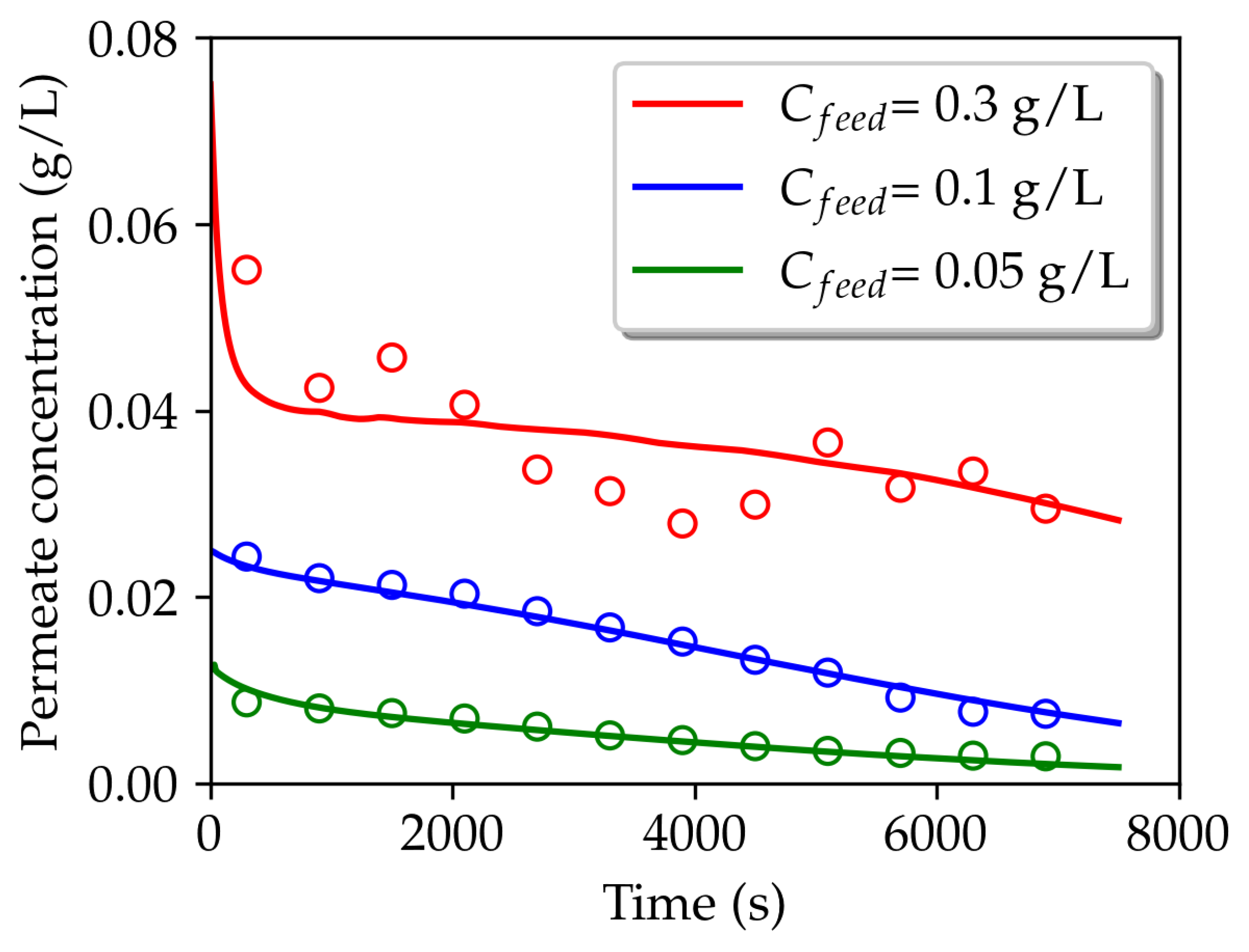

| (g/L) | Total permeate concentration (g/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation | Experiment [20] | |||

| 0.05 | 6 | 400 | 0.0050 | 0.0053 |

| 0.1 | 1 | 250 | 0.0151 | 0.0156 |

| 0.3 | 9 | 70 | 0.0363 | 0.0360 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).