Submitted:

06 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Flow fields

2.1.1. Metal foam

2.1.2. Serpentine channel and housing plate

2.2. PEFC experiment

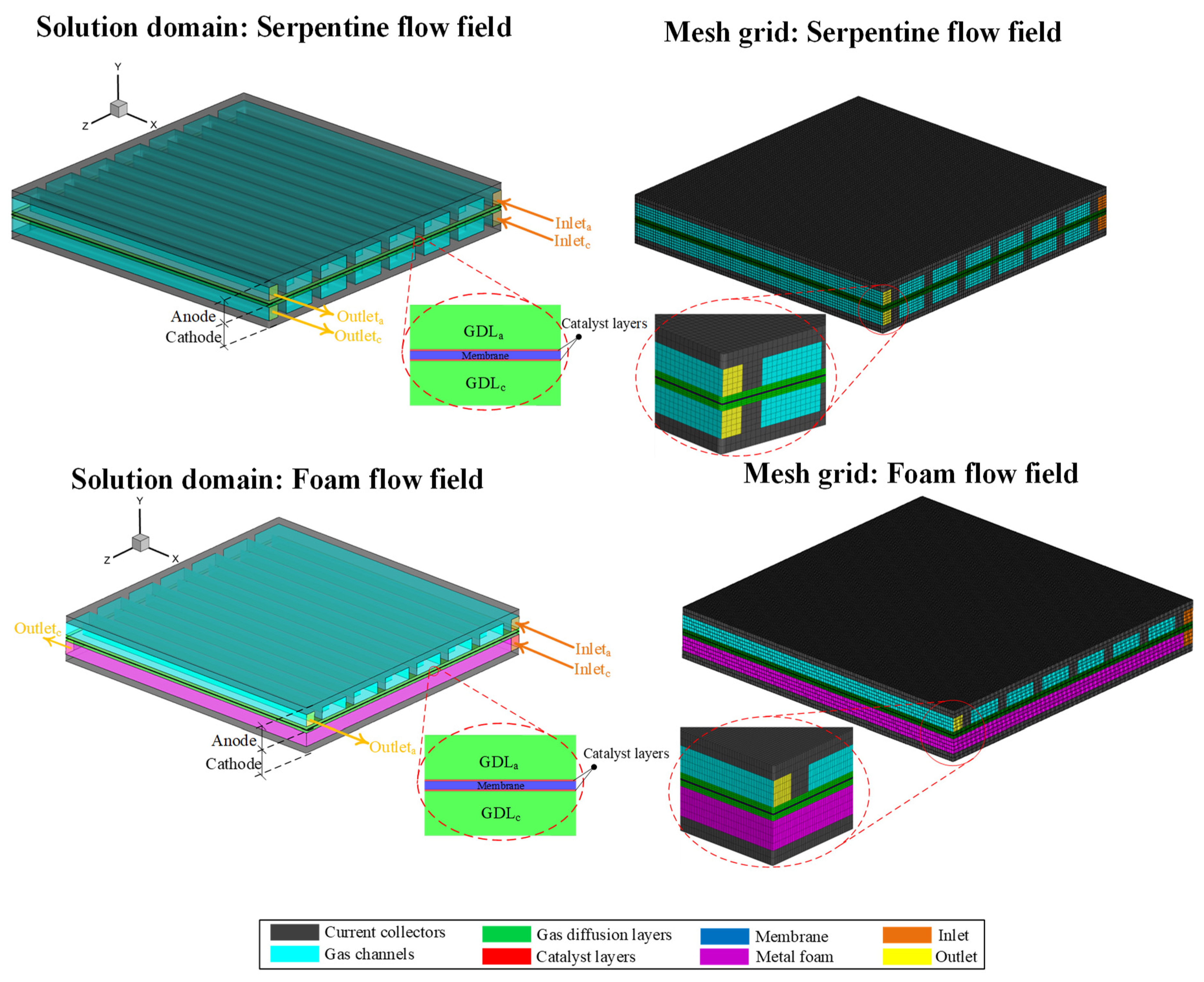

3. CFD-Model descriptions

- (i)

- The PEFC operates under steady-state conditions.

- (ii)

- The gas reactants are considered to be as ideal gas.

- (iii)

- The gravity effect is negligible.

- (iv)

- The GDLs are isotropic porous media from carbon fiber, and the pressure drop is modeled by a linear relation with fluid velocity, Darcy law.

- (v)

- The foams are isotropic porous media from Cu/Ni, and the pressure drop is modeled by quadratic relation with fluid velocity, Forchheimer law.

- (vi)

- Mist flow is considered for the serpentine channel, which means that the velocity of the liquid droplets is equivalent to the gas, and they are carried by high gas speed and disappear as entering into the channels.

- (vii)

- The membrane is impermeable to gases and transfers the protons and dissolved water.

- (viii)

- ACL and CCL are porous media that have triple phase zones (TPZ), including Pt/C particles for electron transferring, ionomer for proton transferring, and void pores for reactant gases transferring.

3.1. Governing equations

3.2. Model input parameters

3.3. Solution procedures

4. Results and discussions

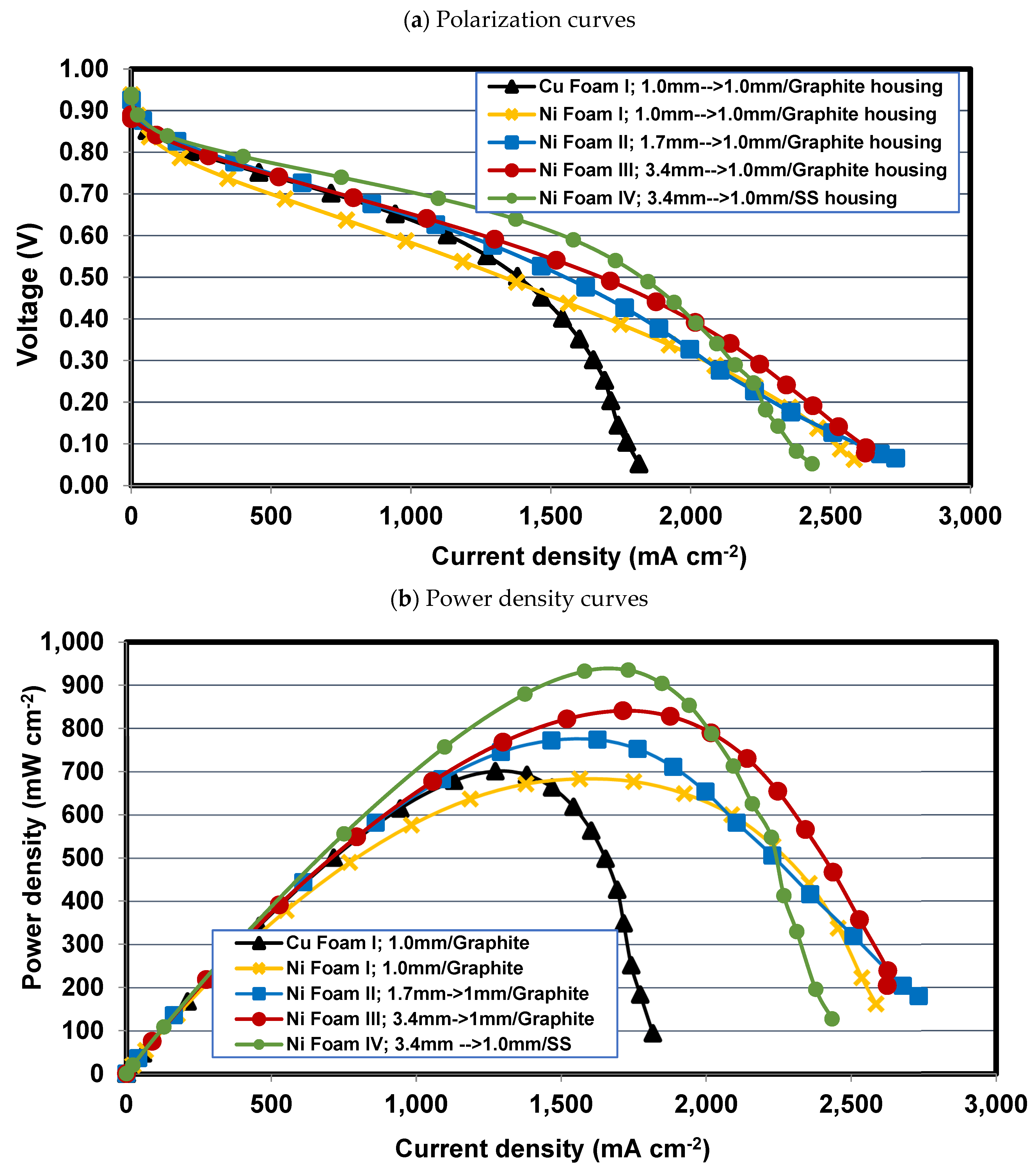

4.1. Comparing Foam I-Cu and Foam I-Ni

4.2. Effect of compression ratio in Foams I-Ni, II-Ni, and III-Ni

4.3. Effect of housing material for Foams III-Ni and IV-Ni

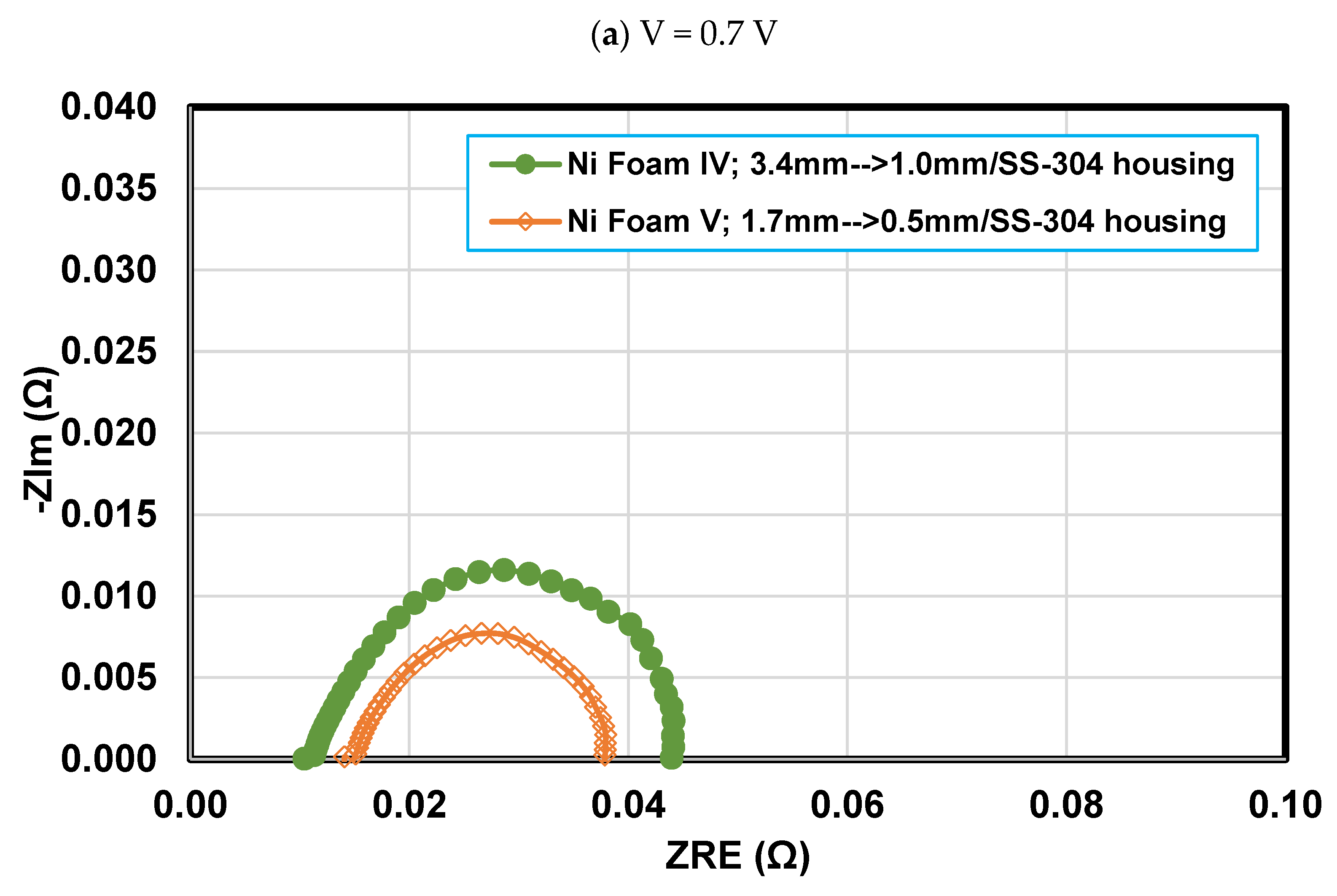

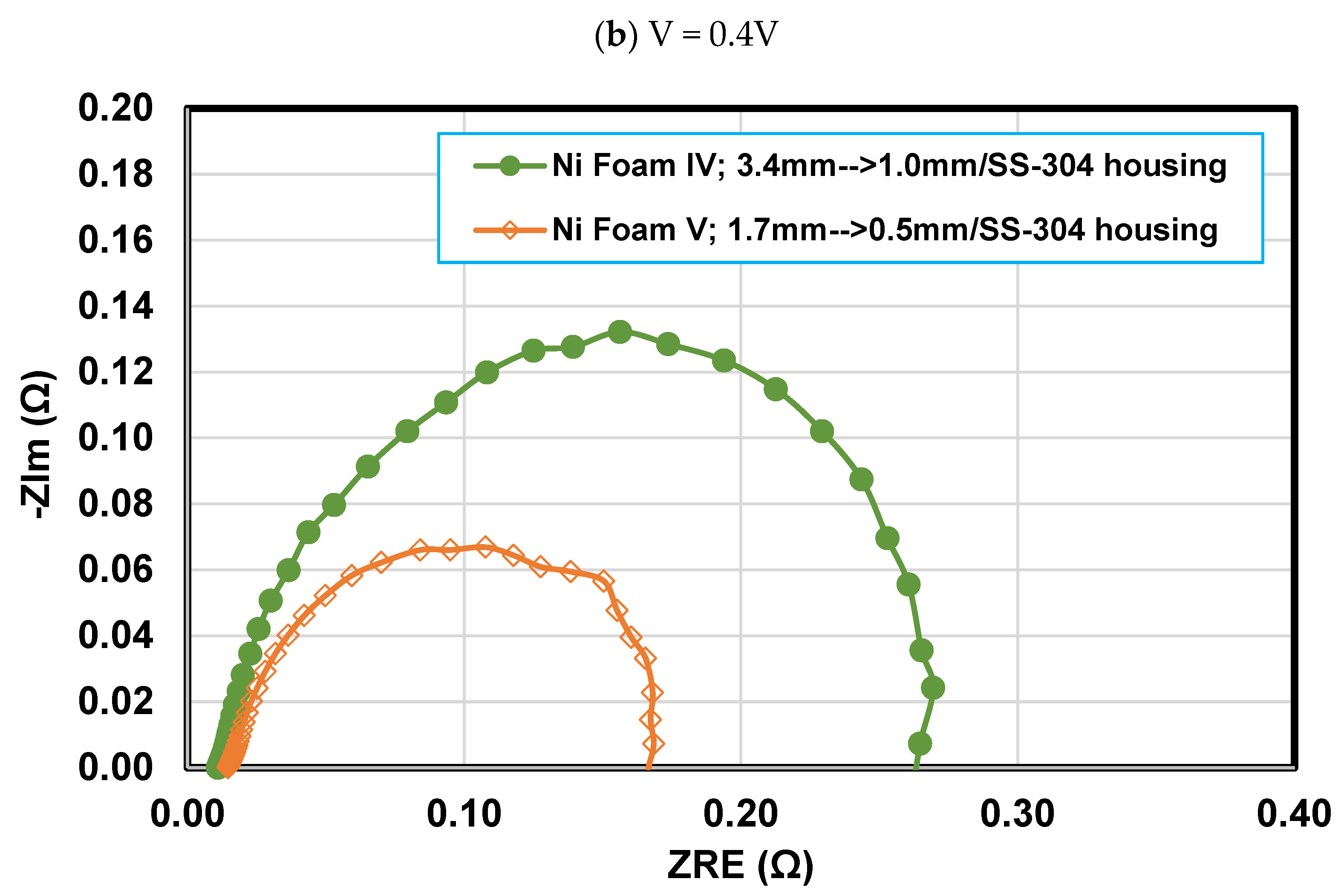

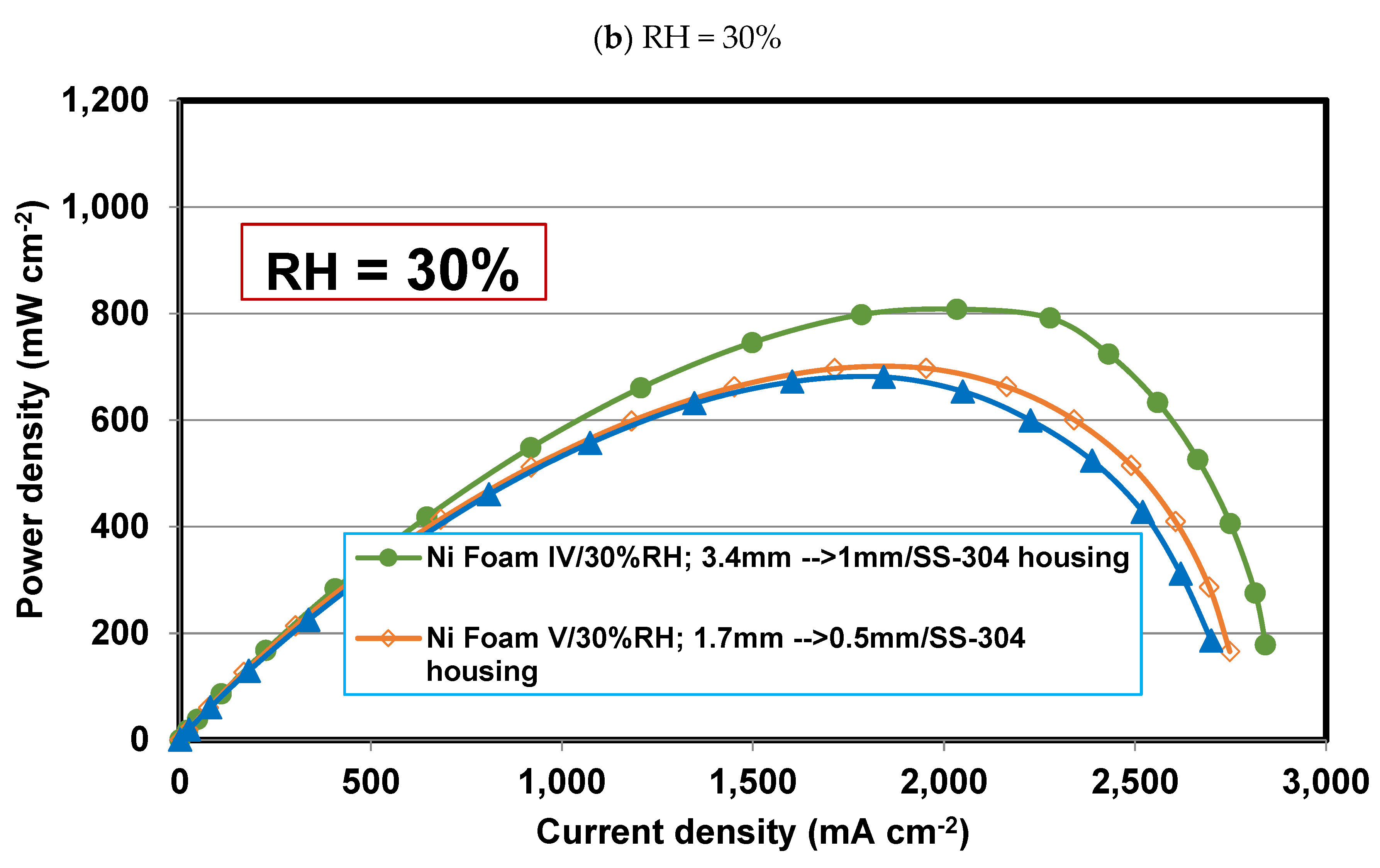

4.4. Effect of final thickness for Foams IV-Ni and V-Ni

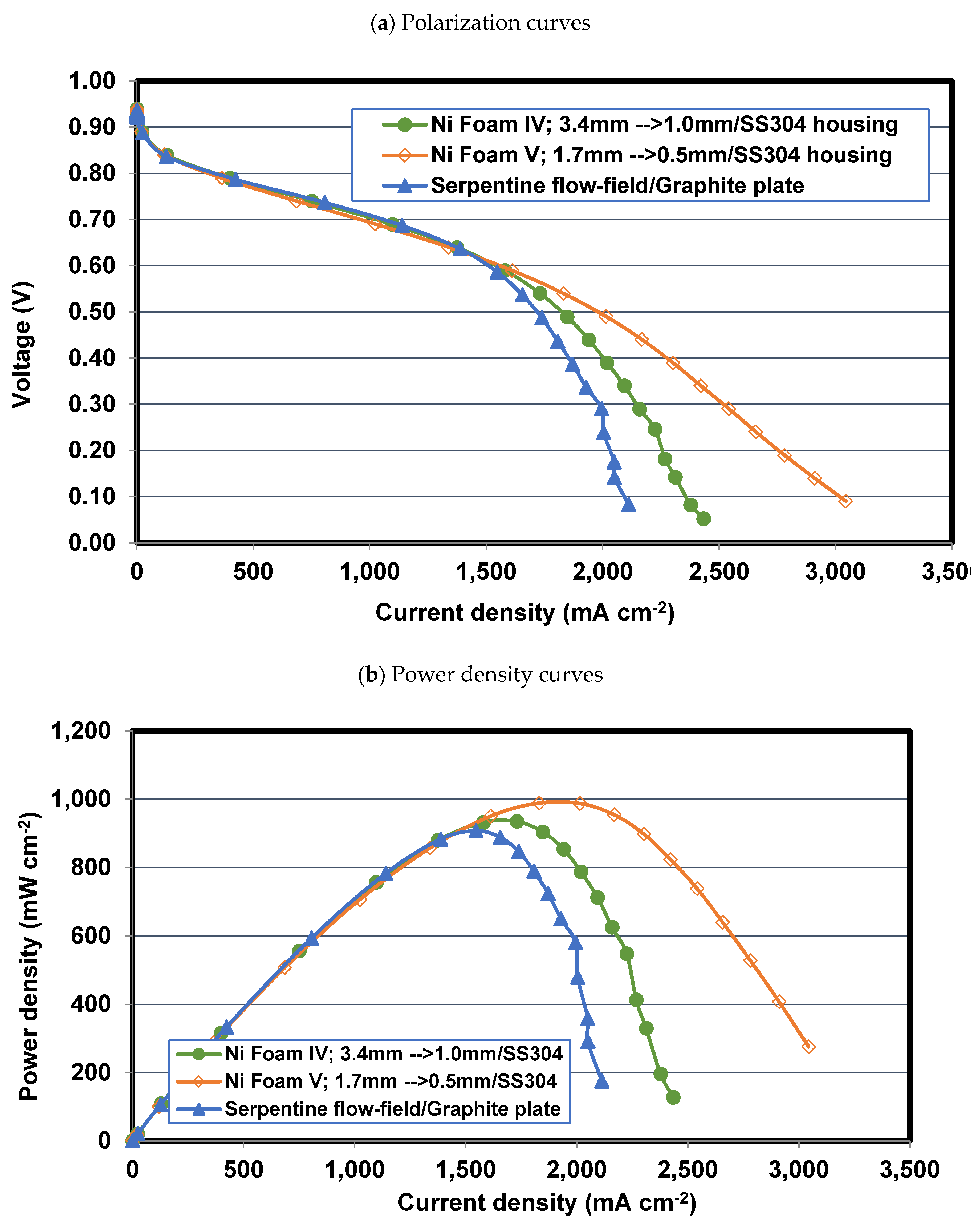

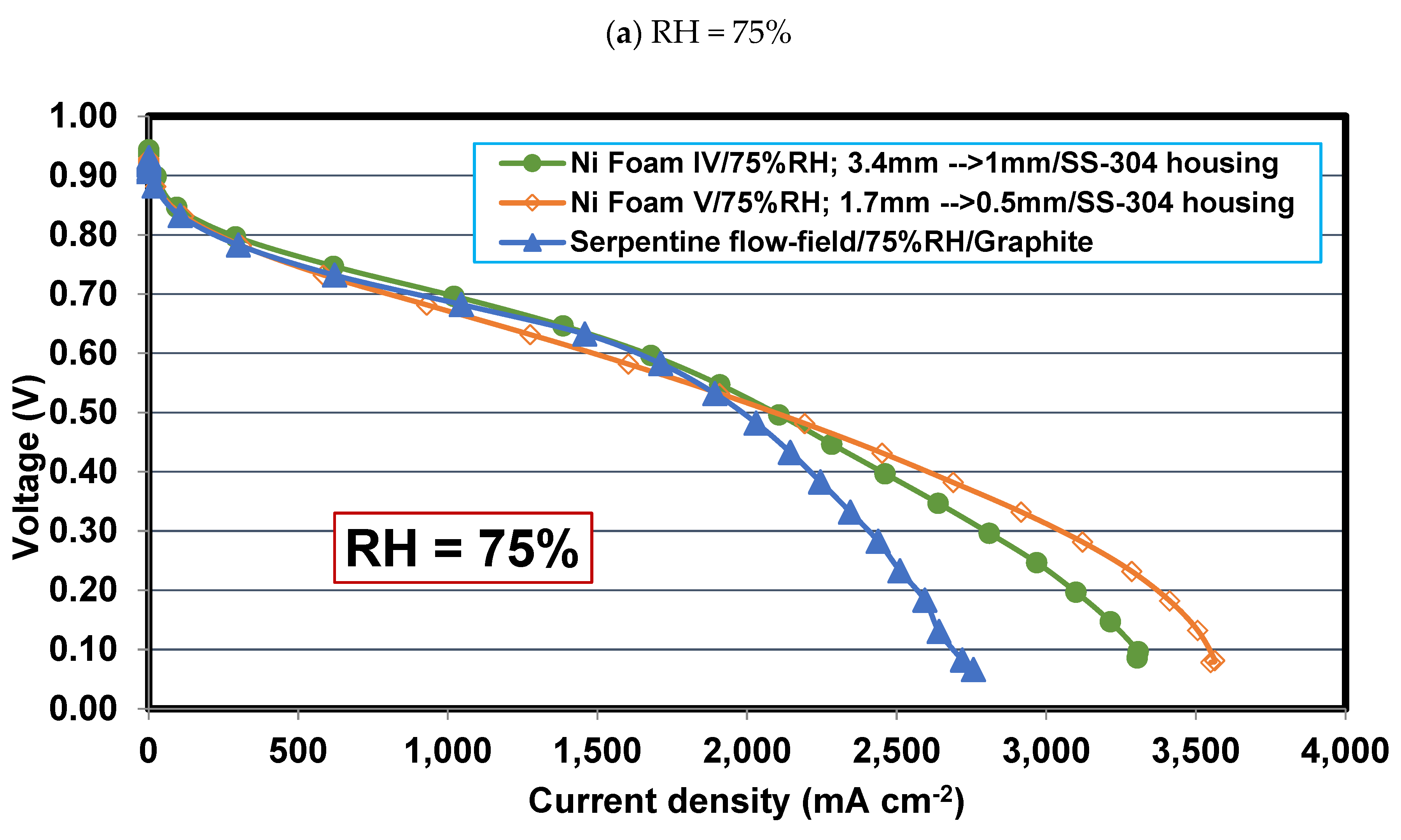

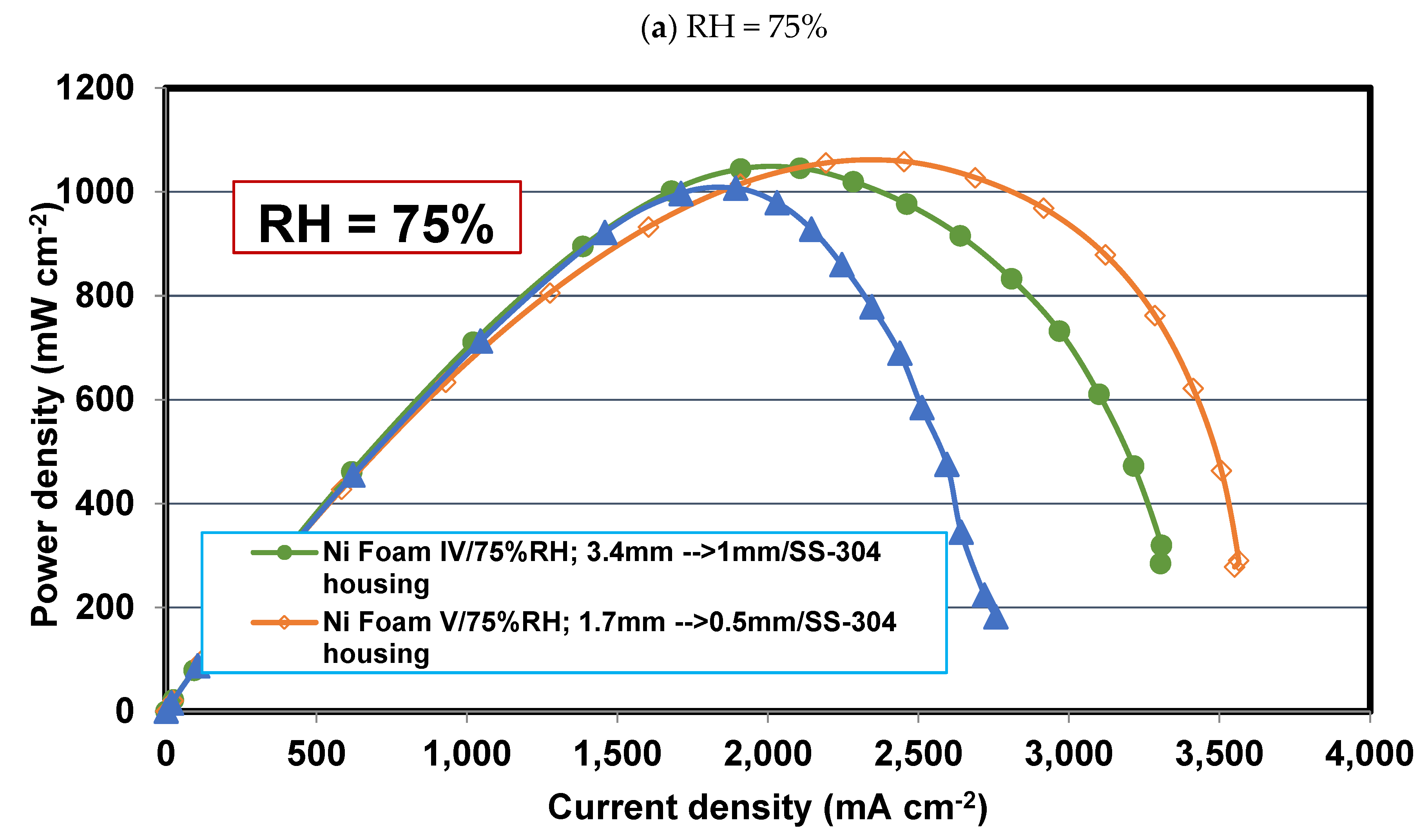

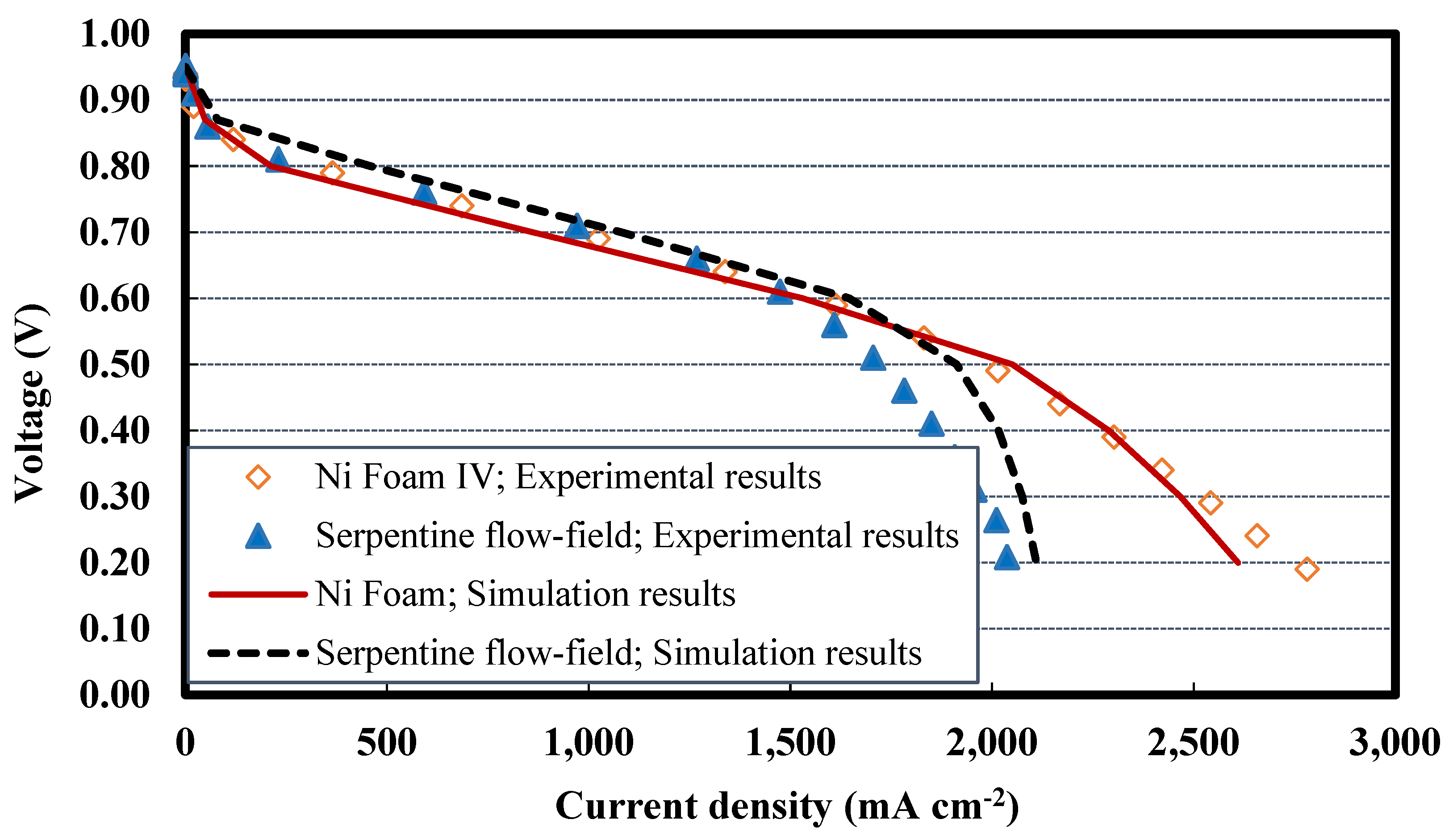

4.5. Comparing Foam V-Ni and serpentine flow fields

4.6. Effect of relative humidity

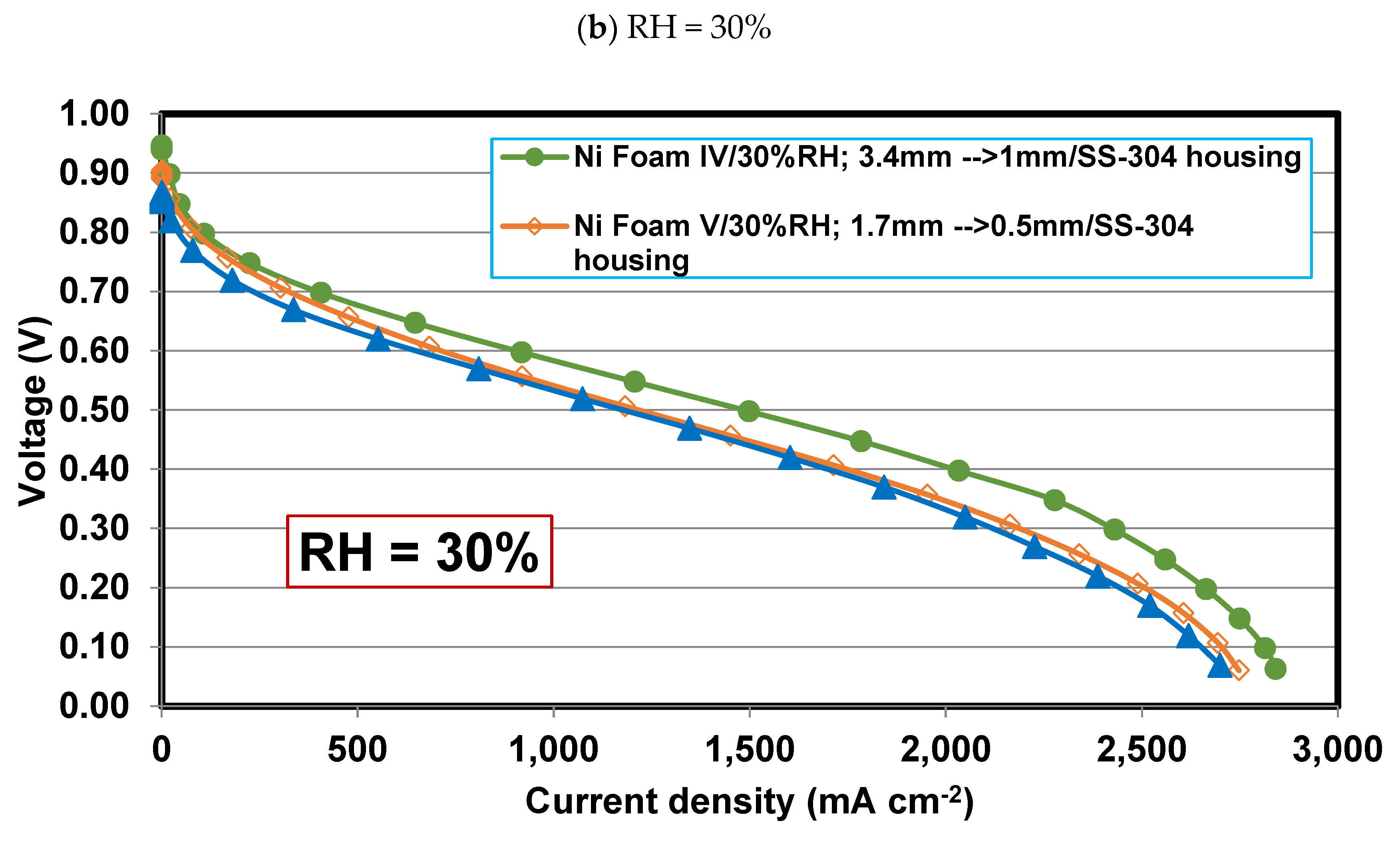

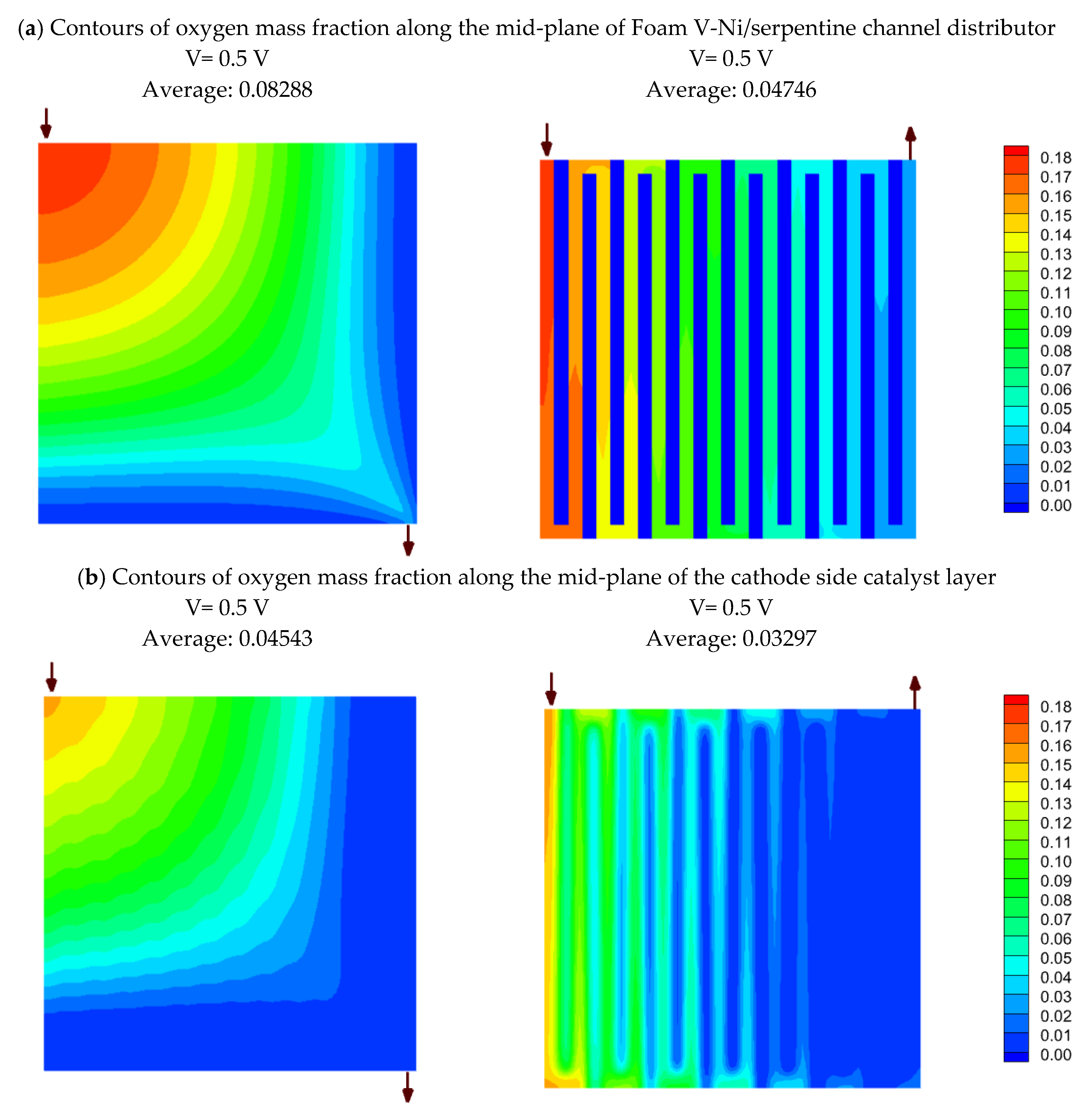

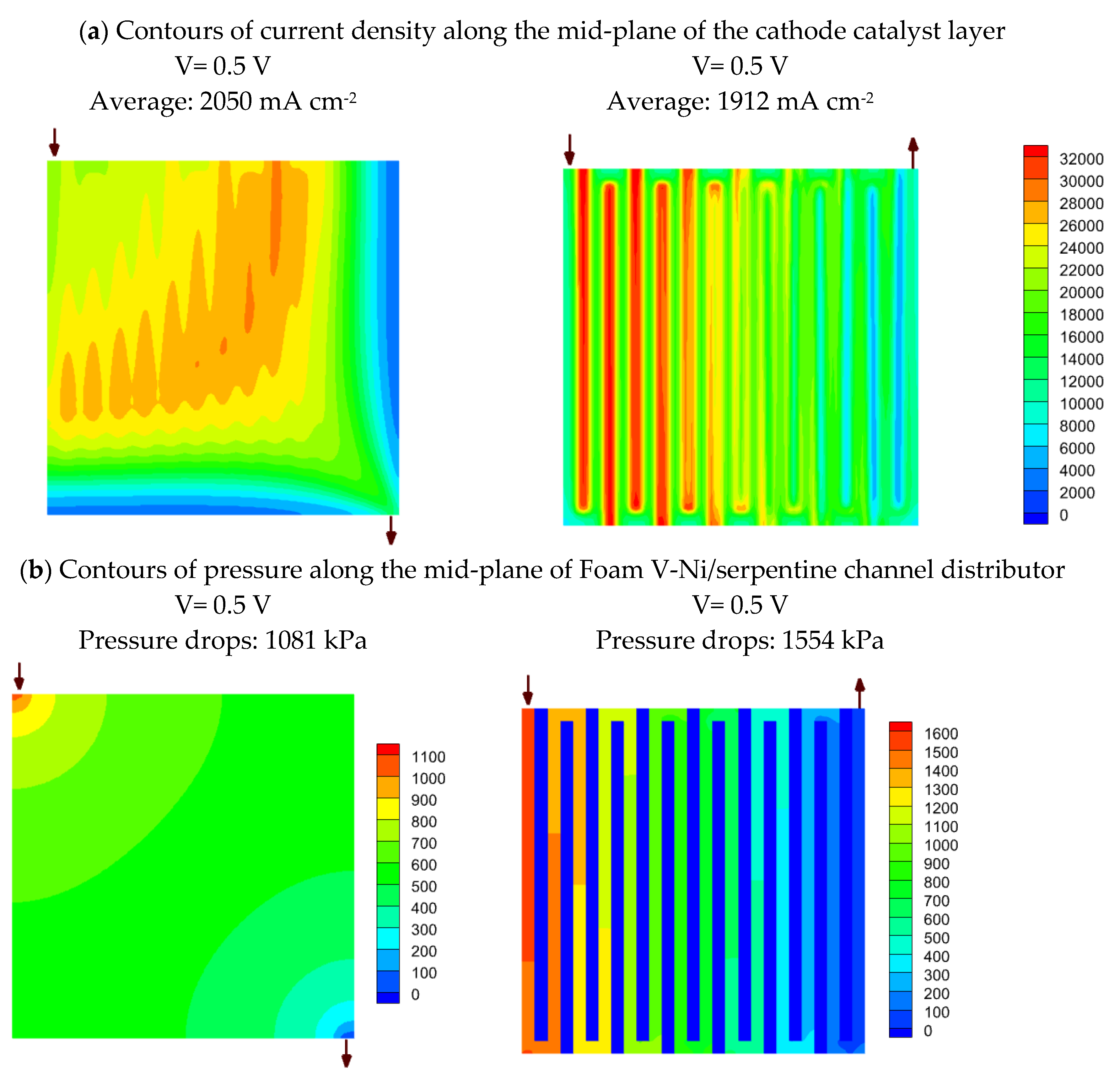

4.7. Simulation results on comparing nickel Foam V and serpentine flow fields

5. Concluding remarks

- The PEFC with Foam I-Cu with no compression, mean pore size of 450 μm, area density 1000 g cm-2 shows 43% higher current density at high voltage range (ohmic range) compared to PEFC with Foam I-Ni with no compression, mean pore size of 250 μm, area density 750 g cm-2. While it has a 30% lower limiting current density compared to that of PEFC with Foam I-Ni at a low voltage range, on the contrary.

- Compressed nickel foam with a compression ratio of 70% increases the contact area by compacting the in-plane pores, while the through-plane pores remain almost intact to pass the reactant flow and form a more uniform distribution. As a result, the compression ratio of 70% for the nickel foam flow field leads to an increase in the fuel cell performance at the ohmic region (e.g., 23% improvement in maximum power density) compared to the case with no compression; meanwhile, it does not affect considerably on the limiting current density.

- The housing plate material is also an influential factor on foam-based fuel cell performance, so that, for the same foam flow field, the PEFC with SS-304 housing plate has a lower ohmic resistance and consequently delivers a maximum power density of 935 mW cm-2, which is 10% higher than that of PEFC with graphite housing plate. However, due to the greater hydrophilicity of SS-304 than graphite, the limiting current density for PEFC with SS-304 is restricted to 2430 ma cm-2, which is 7.2% lower than that of 2620 mA cm-2 for the PEFC with graphite.

- Reducing the final thickness of nickel foam while the compression ratio is constant leads to an increase in flow velocity, pressure drop, and liquid water removal rate and consequently alleviating mass transport resistance. So that the PEFC performance with nickel foam with a final thickness of 0.5 mm experiences a 5.8% improvement in maximum power density and a 28% enhancement in limiting current density, compared to a similar case but with a 1 mm final thickness.

- Operating relative humidity plays a crucial role in the foam flow field performance. So that, at high relative humidities, say 75-100%, Foam V-Ni with a thinner final thickness of 0.5 mm is more successful in discharging the liquid water and distributing the reactant more evenly, which represents higher limiting current density and maximum power density. Meanwhile, at low relative humidity, say 30%, Foam IV-Ni with a thicker final thickness of 1 mm is more efficacious in keeping liquid water and preventing membrane dehydration.

- Using nickel foam as the cathode flow field with a compression ratio of 70% and thinner final thickness, say 0.5 mm, which is placed in an SS304 housing plate instead of graphite, is the best case with the highest cell performance. The PEFC with Foam V-Ni produces a maximum power of 989 mW cm-2 and delivers a limiting current density of 3110 mA cm-2, which shows 10% and 45% improvement, respectively, compared to the PEFC with the conventional serpentine channels.

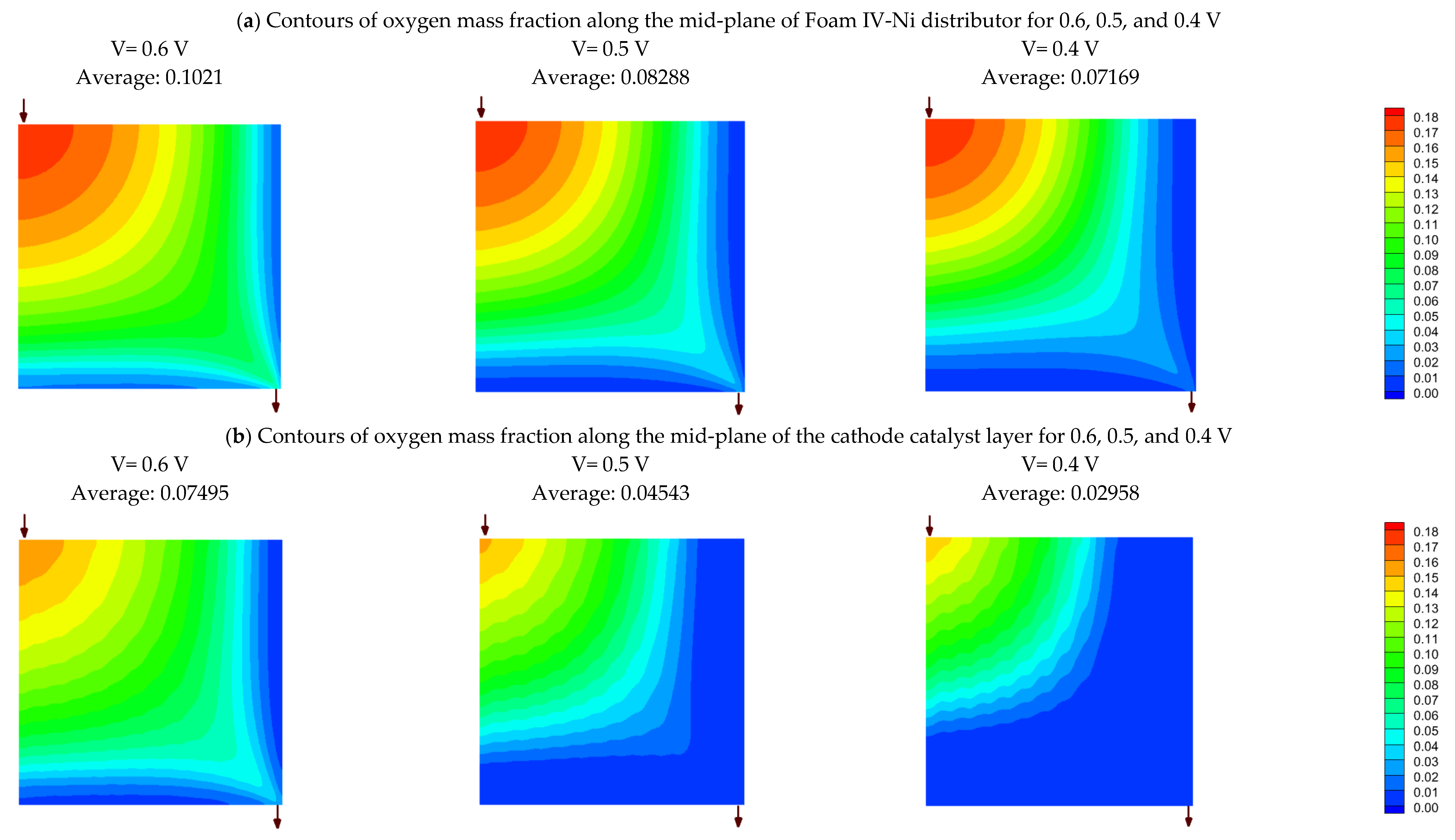

- Simulation results reveal that oxygen mass fraction is distributed more uniformly through the nickel foam than the serpentine channels, so that its average is greater than the single serpentine channel by 75% and 38% at the mid-planes of the flow field and catalyst layer, respectively. This issue leads to a 7.2% enhancement in current density at 0.5 V, which will be increased to a 24% improvement at the lower voltage.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hazar, H.; Yilmaz, M.; Sevinc, H. The effects of different flow field patterns on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 248, 114818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Tu, Z.; Chan, S.H. Evaluation criterion of different flow field patterns in a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 213, 112841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, W.; Tan, J.; An, Y.; Cheng, L. Numerical analysis of parallel flow fields improved by micro-distributor in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 176, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Modeling, design, materials and fabrication of bipolar plates for proton exchange membrane fuel cell: A review. Appl. Energy 2021, 301, 117443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Niu, Z.; Jiao, K. Gas distribution and droplet removal of metal foam flow field for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 116011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Tang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wan, Z. Porous metal materials for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells – A review. Appl. Energy 2012, 94, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Lim, J.; Kim, S.; Choi, I.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Hwang, W.; Lim, M.S.; Cho, Y.-H.; Sung, Y.-E. Enhancement of mass transport in fuel cells using three-dimensional graphene foam as flow field. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 265, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, M.; Sun, K.; Chen, R.; Che, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Li, Q.; Tao, X.; Wang, T. Oxygen transport in proton exchange membrane fuel cells with metal foam flow fields. J. Power Sources 2022, 521, 230937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wan, Z.; Kong, X.; Tu, Z.; Wang, X. Water management and structure optimization study of nickel metal foam as flow distributors in proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Appl. Energy 2022, 309, 118448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awin, Y.; Dukhan, N. Experimental performance assessment of metal-foam flow fields for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Appl. Energy 2019, 252, 113458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, L.; Jiao, K.; Tian, P.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Optimization of porous media flow field for proton exchange membrane fuel cell using a data-driven surrogate model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 226, 113513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Shi, W.; Wang, R.; Lu, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, K.; Hou, Z. Elucidating the operating behavior of PEM fuel cell with nickel foam as cathode flow field. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 64, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Lim, J.; Lim, M.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, O.-H.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, Y.-H.; Sung, Y.-E. Gas diffusion layer/flow-field unified membrane-electrode assembly in fuel cell using graphene foam. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 323, 134808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.; Ju, H. Numerical study on applicability of metal foam as flow distributor in polymer electrolyte fuel cells (PEFCs). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 14012–14026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cho, J.; Whiteley, M.; Rasha, L.; Neville, T.; Ziesche, R.; Xu, R.; Owen, R.; Kulkarni, N.; Hack, J.; et al. Characterization of water management in metal foam flow-field based polymer electrolyte fuel cells using in-operando neutron radiography. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 2195–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Vaz, N.; Lee, J.; Ju, H. Advantages and disadvantages of various cathode flow field designs for a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 163, 120497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atyabi, S.A.; Afshari, E.; Zohravi, E.; Udemu, C.M. Three-dimensional simulation of different flow fields of proton exchange membrane fuel cell using a multi-phase coupled model with cooling channel. Energy 2021, 234, 121247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klages, M.; Enz, S.; Markötter, H.; Manke, I.; Kardjilov, N.; Scholta, J. Investigations on dynamic water transport characteristics in flow field channels using neutron imaging techniques. J. Power Sources 2013, 239, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cunningham, N. Development of porous carbon foam polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 2291–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhou, W.; Li, S.; Li, F.; Ling, W. Performance improvement of proton exchange membrane fuel cells with compressed nickel foam as flow field structure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 17833–17843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.; Rahman, A.; Mojica, F.; Mehrazi, S.; Kort-Kamp, W.J.; Chuang, P.-Y.A. Experimental and computational study of the microporous layer and hydrophobic treatment in the gas diffusion layer of a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2021, 509, 230350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, C.; Sohn, Y. Application of Metal Foam as a Flow Field for PEM Fuel Cell Stack. Fuel Cells 2018, 18, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, N.; Sánchez-Molina, M.; Sevilla, G.; Amores, E.; Almandoz, E.; Esparza, J.; Vivas, M.R.C.; Colominas, C. Coated stainless steels evaluation for bipolar plates in PEM water electrolysis conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 25929–25943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Lei, H.; Hu, G. Enhanced corrosion resistance of Ni/Sn nano-electrodeposited metal foam for flow field application in simulated PEMFC cathode environment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35412–35422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, S. Graphene against corrosion. Nat Nanotechnol 2014, 9, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Bao, Z.; Xie, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, K. Three-dimensional multi-phase simulation of PEM fuel cell considering the full morphology of metal foam flow field. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 2978–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fly, A.; Meyer, Q.; Whiteley, M.; Iacoviello, F.; Neville, T.; Shearing, P.; Brett, D.; Kim, C.; Chen, R. X-ray tomography and modelling study on the mechanical behaviour and performance of metal foam flow-fields for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7583–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Hwang, W.; Lim, M.S.; Kim, S.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Kim, O.-H.; Shim, J.-G.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, Y.-H.; et al. Achieving breakthrough performance caused by optimized metal foam flow field in fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 22074–22084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, H.; Kermani, M.J.; Dabir, B. Influences of bipolar plate channel blockages on PEM fuel cell performances. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 124, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein-Jahromi, M.; Kermani, M. Three-dimensional multiphase simulation and multi-objective optimization of PEM fuel cells degradation under automotive cyclic loads. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 231, 113837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charde, N. Microstructure and Fatigue Properties of Dissimilar Spot Welds Joints of AISI 304 and AISI 1008. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2013, 7, 882–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sharma, R.K. Assessing the effects of different dielectrics on environmentally conscious powder-mixed EDM of difficult-to-machine material (WC-Co). Front. Mech. Eng. 2016, 11, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atapour, M.; Rajaei, V.; Trasatti, S.; Casaletto, M.P.; Chiarello, G.L. Thin Niobium and Niobium Nitride PVD Coatings on AISI 304 Stainless Steel as Bipolar Plates for PEMFCs. Coatings 2020, 10, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavese, M.; Musso, S.; Bianco, S.; Giorcelli, M.; Pugno, N. An analysis of carbon nanotube structure wettability before and after oxidation treatment. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 474206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozbial, A.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Gong, X.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Li, L. Understanding the intrinsic water wettability of graphite. Carbon 2014, 74, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Foam type | Material | Housing plate material | Initial thickness (mm) | Final thickness (mm) | CR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foam I-Cu | Copper | Graphite | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Foam I-Ni | Nickel | Graphite | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Foam II-Ni | Nickel | Graphite | 1.7 | 1 | 40 |

| Foam III-Ni | Nickel | Graphite | 3.4 | 1 | 70 |

| Foam IV-Ni | Nickel | SS-304 | 3.4 | 1 | 70 |

| Foam V-Ni | Nickel | SS-304 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 70 |

| Mass | (1) | |

| Momentum |

where, the Forchheimer coefficient, , is only considered for metal foam and is vanished for all other porous layers. The effective porosity and permeability in porous layers are calculated as follows: |

(2) |

| Species |

where, the effective diffusivity is calculated as: |

(3) |

| Energy |

that, the effective thermal conductivity is calculated as: , where kl is the thermal conductivity of liquid water, and kg is the thermal conductivity of gas mixture which is calculated by the ideal-gas-mixing-law. |

(4) |

| electric charges | (5) | |

| Protonic charges |

where, the volumetric electrochemical reaction rate is considered by the Butler-Volmer relation: |

(6) |

| Liquid water |

where, the water saturation diffusivity (capillary diffusivity) is calculated by: , , in which is capillary pressure computed by the Leverett function: , where is liquid-gas surface tension, |

(7) |

| Dissolved-water |

where, the dissolved water diffusion coefficient is calculated by: |

(8) |

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometrical | |||

| Active area | A | mm2 | |

| Flow-field configuration | a) Control sample: single serpentine channel for both anode and cathode electrodes b) Intervention group: single serpentine channel for anode and metal foam for cathode electrodes |

||

| Channel width | mm | 0.8 | |

| Channel height | mm | 1 | |

| Rib width | mm | 0.8 | |

| GDL thickness | µm | 200 | |

| Metal foam thickness | mm | 1 | |

| Catalyst layers (CL) thickness | µm | 15 | |

| Membrane thickness | µm | 25 | |

| Current collector thickness | mm | 0.5 | |

| Electrochemical | |||

| Open circuit voltage | V | 0.945 | |

| Active surface-to-volume ratio | m2 m-3 | 200,000 | |

| Anode ref. current density, | A m-2 | 500,000 | |

| Cathode ref. current density, | A m-2 | 5000 | |

| Anode concentration exponent | - | 0.5 | |

| Cathode concentration exponent | - | 1 | |

| Hydrogen ref. concentration, | kmol m-3 | 1 | |

| Oxygen ref. concentration, | kmol m-3 | 1 | |

| Anode exchange coefficient, | , | - | 0.85 |

| Cathode exchange coefficient, | , | - | 0.85 |

| Faraday constant | F | C mol-1 | 96,485.3 |

| Material/structural | |||

| Density of GDL, solid part of Foam, CL, Mem, CC |

, , , , |

kg m-3 | 2719 Cu: 8978/ Ni: 8900 2719 1980 2719 |

| Density of liquid water | kg m-3 | 998.2 | |

| Specific heat of GDL, solid part of Foam, CL, Mem, CC |

, , , , |

J kg-1 K-1 | 871 Cu: 381/ Ni:460.6 871 2000 871 |

| Equivalent weight of the membrane | EW | kg (kmol)-1 | 2100 |

| Porosity of GDL, Foam, CL |

, , |

- | 0.8 0.85 0.47 |

| Viscous resistance (inverse of permeability) of GDL, Foam, CL |

|

m-2 |

|

| Contact angle of GDL, Foam, CL (for water droplet) |

, , |

O | 92 145 92 |

| Inertial resistance of Foam | m-1 | 2100 | |

| Molar volume of water | m 3 mol -1 | ||

| Molar volume of membrane | m 3 mol -1 | ||

| Transport properties | |||

| Reference hydrogen diffusivity | m2 s-1 | ||

| Reference oxygen diffusivity | m2 s-1 | ||

| Reference vapor diffusivity | m2 s-1 | ||

| Hydrogen thermal conductivity | W m-1 K-1 | 0.1672 | |

| Oxygen thermal conductivity | W m-1 K-1 | 0.0246 | |

| Vapor thermal conductivity | W m-1 K-1 | 0.0261 | |

| Hydrogen viscosity | kg m-1 s-1 | ||

| Oxygen viscosity | kg m-1 s-1 | ||

| Vapor viscosity | kg m-1 s-1 | ||

| Liquid water viscosity | kg m-1 s-1 | ||

| Thermal conductivity of GDL, Foam, CL, Mem, CC, |

, , , |

W m-1 K-1 | 10 Cu: 387.6/ Ni: 91.74 10 2 100 |

| Electrical conductivity of GDL, Foam, CL, Mem, CC |

, , , , |

S m-1 | 5000 Cu: / Ni: 5000 |

| Operating Conditions | |||

| Relative humidity at anode/cathode inlets | , | % | 100 |

| Operating temperature | , | oC | 80 |

| Operating pressure | P | bar | 1 |

| Stoichiometry coefficient at anode/cathode inlets | , | 1.3, 1.5 |

| Flow field type | Limiting current density | Maximum power density | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value mA cm-2 |

Improve rate | Value mW cm-2 |

Improve rate | |

| Serpentine channels | 2140 | 1.00 | 901 | 1.00 |

| Foam I-Cu | 1820 | 0.85 | 701 | 0.78 |

| Foam I-Ni | 2580 | 1.21 | 684 | 0.76 |

| Foam II-Ni | 2710 | 1.27 | 774 | 0.86 |

| Foam III-Ni | 2620 | 1.22 | 841 | 0.93 |

| Foam IV-Ni | 2430 | 1.13 | 935 | 1.04 |

| Foam V-Ni | 3110 | 1.45 | 989 | 1.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).