Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide. According to Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) 2020 data, approximately 600,000 new CC cases and 350,000 deaths per year are predicted (1). Although the mechanism of entry of HPV into the cell has not been conclusively determined, the first step involves the attachment of the major L1 capsid protein of HPV to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) found within the plasma membrane of keratinocytes (2). In subsequent processes, the cleavage of the minor capsid protein L2 by furin is a sine qua non for HPV infection. The cleavage of viral particles by furin provide endosomal escape and a bypass mechanism for the first step of entry (3,4).

Furin participates in critical steps of the immune response by regulating T-cell and macrophage functions via TGFβ1 synthesis and modulating immune checkpoint signaling via programmed death-1 (PD-1) synthesis. Intriguingly, furin regulates the cancer microenvironment in favor of cancer cells by providing immune escape for cancer cells via accelerating the depletion of cytotoxic T cells. Although the mechanisms underlying its diverse functions have not been elucidated in depth yet, furin plays a crucial role in tumor immune microenvironment via regulating functions of myeloid and lymphoid cells and their regulatory molecules (5-9).

Currently, the tumor microenvironment (TME) has been subjected to comprehensive studies, and it has been proven that inflammatory cells such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, and platelets, are critical components of the immune response to cancer (5-10). The number of circulating inflammatory cells and platelets and their indices are the most prominent indicators of immune response to cancer (9). Even if the role of neutrophils in cancer is ambiguous, a high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is related to the poorer prognosis of various cancers, such as breast cancer, colorectal cancer, malignant melanoma, and gynecological cancer (11,12). Likewise, a high monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) and a high platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) are also considered valuable prognostic markers in multiple cancers, such as head and neck, gastric, colorectal, and brain metastasis (13-16). Recently, the systemic immune inflammation index (SII), which takes into account the equation of platelet count, has been regarded as a superior prognostic factor for solid tumors, such as, esophageal, gynecological, and triple-negative breast cancer, and predicts the response to immunotherapy (17-19).

Circulating inflammatory cells and platelets are the most salient indicators of immune response to cancer and indirectly reflect the tumor immune microenvironment status. On the other hand, furin impresses the cancer microenvironment in favor of cancer cells by providing immune escape. Therefore, we hypothesized that both of these could interact with each other in the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia to cancer. We aimed to elucidate the relationship of furin with inflammation in the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia to cervical cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional study recruited 81 women admitted to the Gynecology Department of the Balıkesir University School of Medicine between January 2018 and 2023. Women aged 30-65 who needed colposcopic examination based on abnormal PAP smear (Thin-prep) screening results or HR-HPV DNA (Rotor-Gene Q, Qiagen) positivity participated in the study. The participants were managed according to the current American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) guidelines (20). Participants either followed-up or underwent surgery consistent with the colposcopic biopsy results.

The study groups were formed based on the pathological results as follows. Women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1 biopsy results (Group I, n=30) were regularly followed; however, those with CIN 2 and 3 (Group II, n=28) underwent a conization operation. Women with squamous CC (Group III, n=23) underwent either simple or radical hysterectomy in conformity with their stage (

Table 1). Routine blood samples were retrieved within one week before biopsy, conization, or surgery.

Women with acute infection and chronic inflammatory diseases, diabetes, a history of cancer, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy, receiving anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive agents, vaginitis, cervicitis, and other sexually transmitted infections were excluded from the study. STROBE (The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed (21).

Immunohistochemistry & Evaluation

Standardized tissue preparation protocols were followed during the histopathological examination of cervical tissues as previously described (22). Subsequently, 1:100 diluted anti-furin antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX), 1:100 diluted anti-ki-67 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX), and 1:50 diluted anti-p16 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX) antibodies were applied. All slides were examined and scored concurrently by two experienced pathologists who were blinded to the clinical diagnoses. Using an image capture system, the furin expression in the study groups was randomly compared based on immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining density.

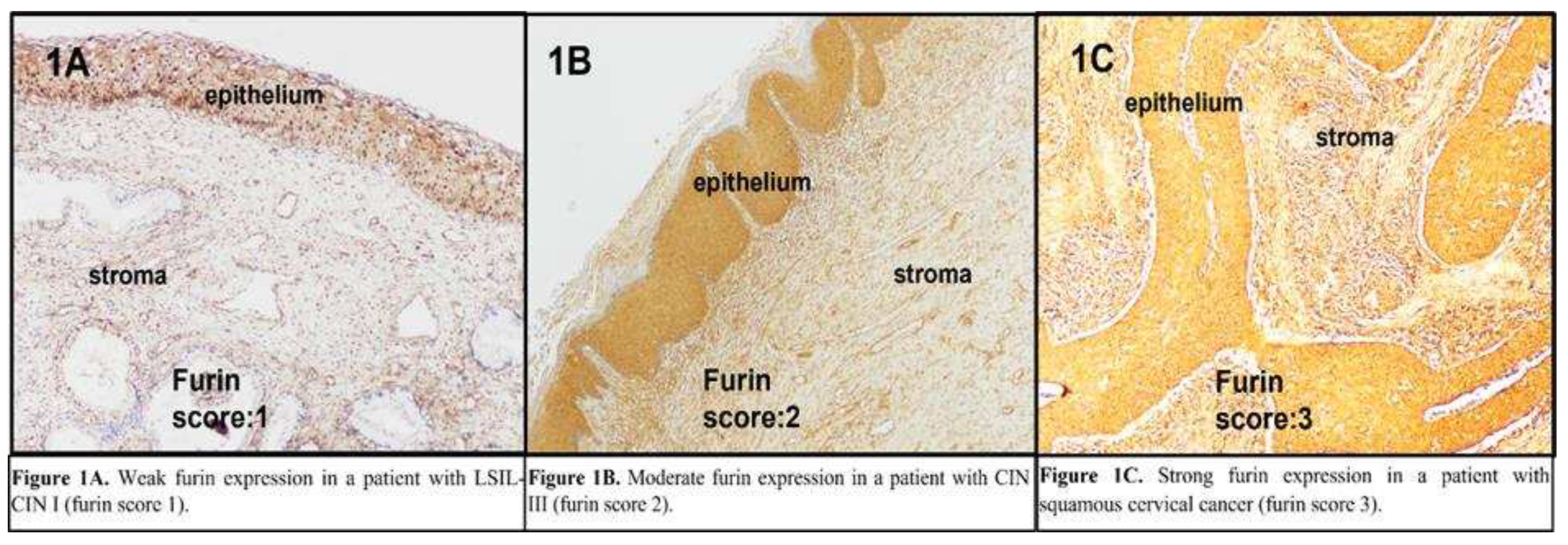

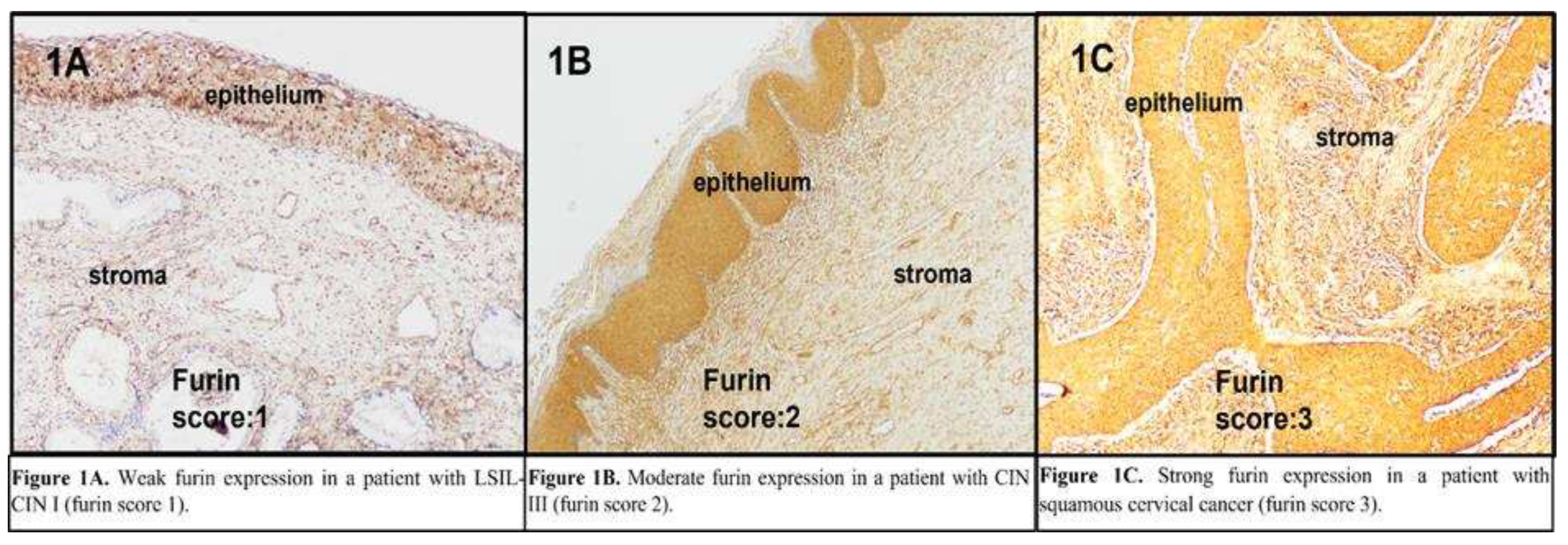

The IHC staining intensity of furin, ki-67, and p-16 was evaluated using a scoring system based on the staining ratio of the cervical cells. The furin scores were as follows: 10-40 staining 1(+); 41-70% staining 2(+); and >71% staining 3(+) (

Figure 1A, 1B, and 1C, respectively). For ki-67, the intensity score was graded as follows: 10-30% staining 1(+); 31-50% staining 2(+); 51–70%, 3(+); and ≥ 71%, 4(+). For p16, block-positive staining was scored 1(+); on the other hand, equivocal or negative staining was scored 0.

Indices

NLR, PLR, and MLR were calculated as follows: the absolute number of neutrophils, platelets, and monocytes was divided by the absolute number of lymphocytes. SII was calculated using the following formula: SII = platelet count × neutrophil count/lymphocyte count.

Statistics

Statistical and power analyses were performed using open-source Jamovi statistical software (version 2.3.21) and G* Power software (version 3.1.9.7). According to the literature, the minimum sample size was calculated as twenty-two per group based on an α error of 0.01, and power of 0.80. The distribution and homogeneity of the groups were evaluated by skewness, kurtosis, Levene’s test, and Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test.

The Kruskal‒Wallis test was applied to nonparametric group variables, and pairwise comparisons were made using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner test. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc tests were applied to the parametric group variables. Partial correlation analyses were performed using either Pearson or Spearman coefficients, according to variables with normal and abnormal distributions. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to denote the performance of inflammatory indices in discriminating the CC from cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

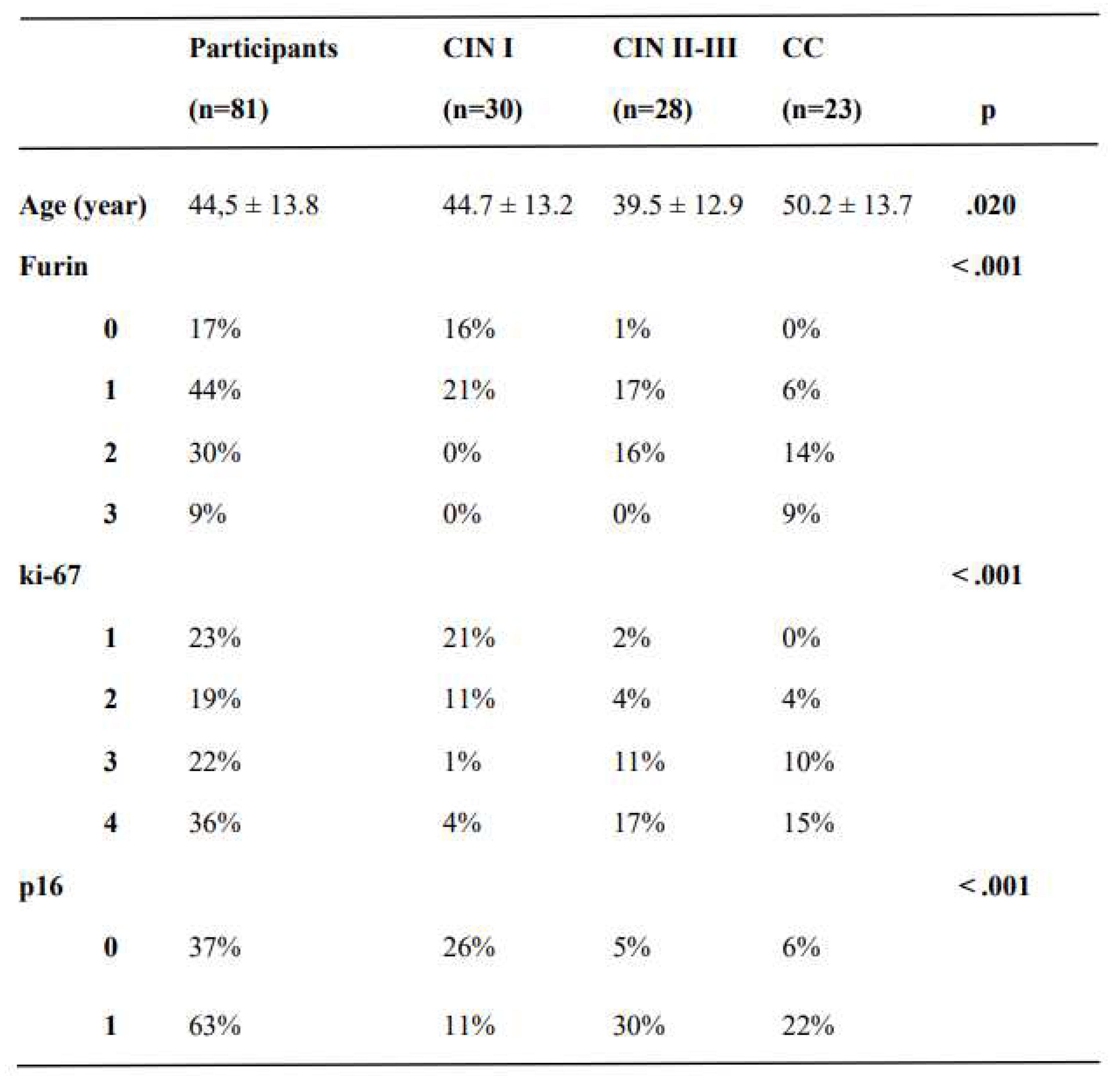

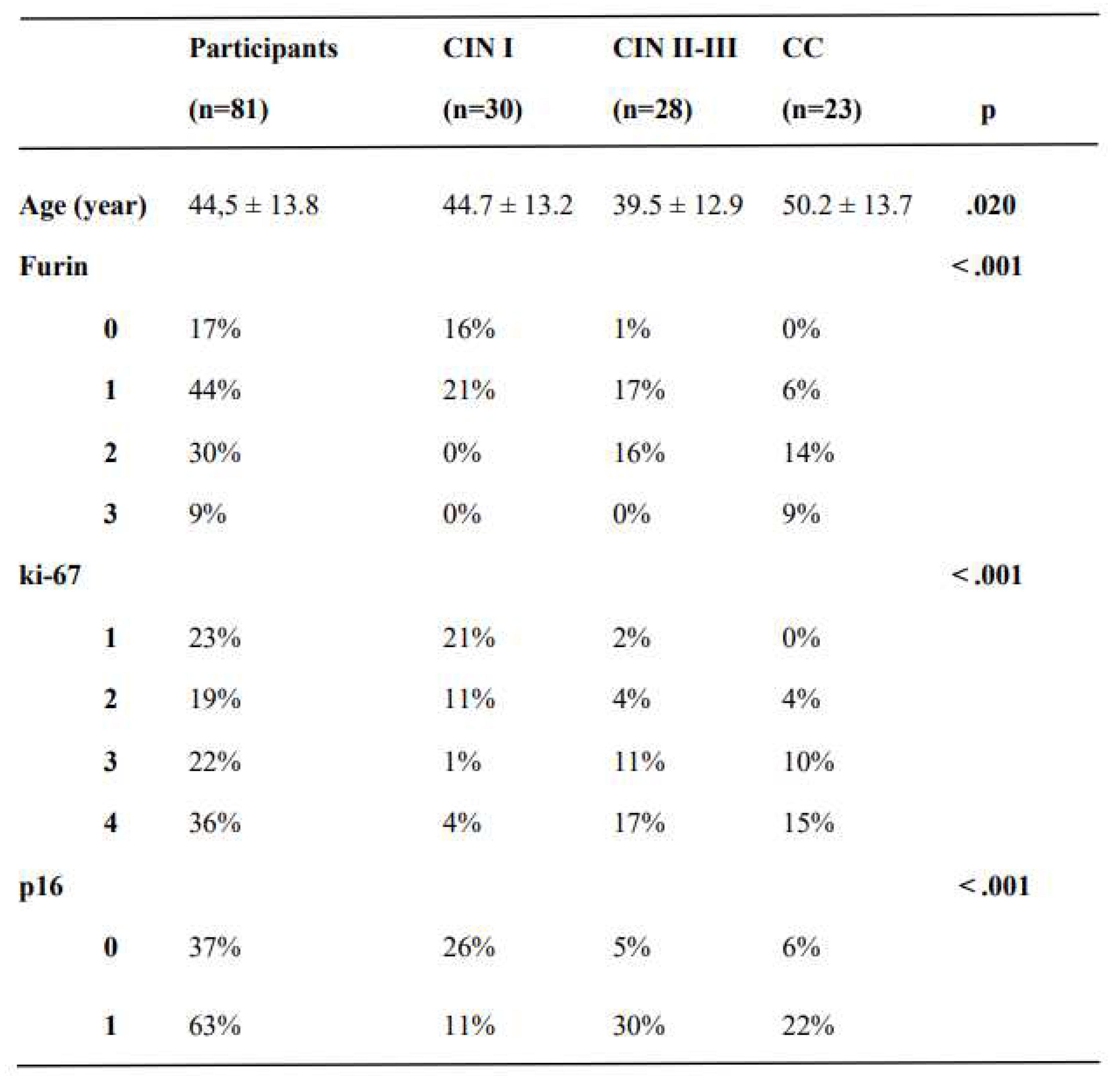

This cross-sectional study reviewed the cervical pathology and laboratory results of 81 women. The mean age of the groups was 44.5 ± 13.7 years. There was a statistically significant difference between CIN II-III and CC groups in the context of age (39.5 ± 12.9 years vs. 50.2 ± 13.7 years, respectively, p <.05); otherwise, the mean ages were similar between groups (

Table 1).

Furin expression gradually increased from CIN I to CIN II-III and from CIN II-III to CC, respectively (p < .001, p = .005). ki-67 and p16 expression differed significantly between the study groups (p < .001), except for CIN II-III and CC (p =.817 and p =.771, respectively) (

Table 1). The pathological results of the participants are summarized in

Table 1.

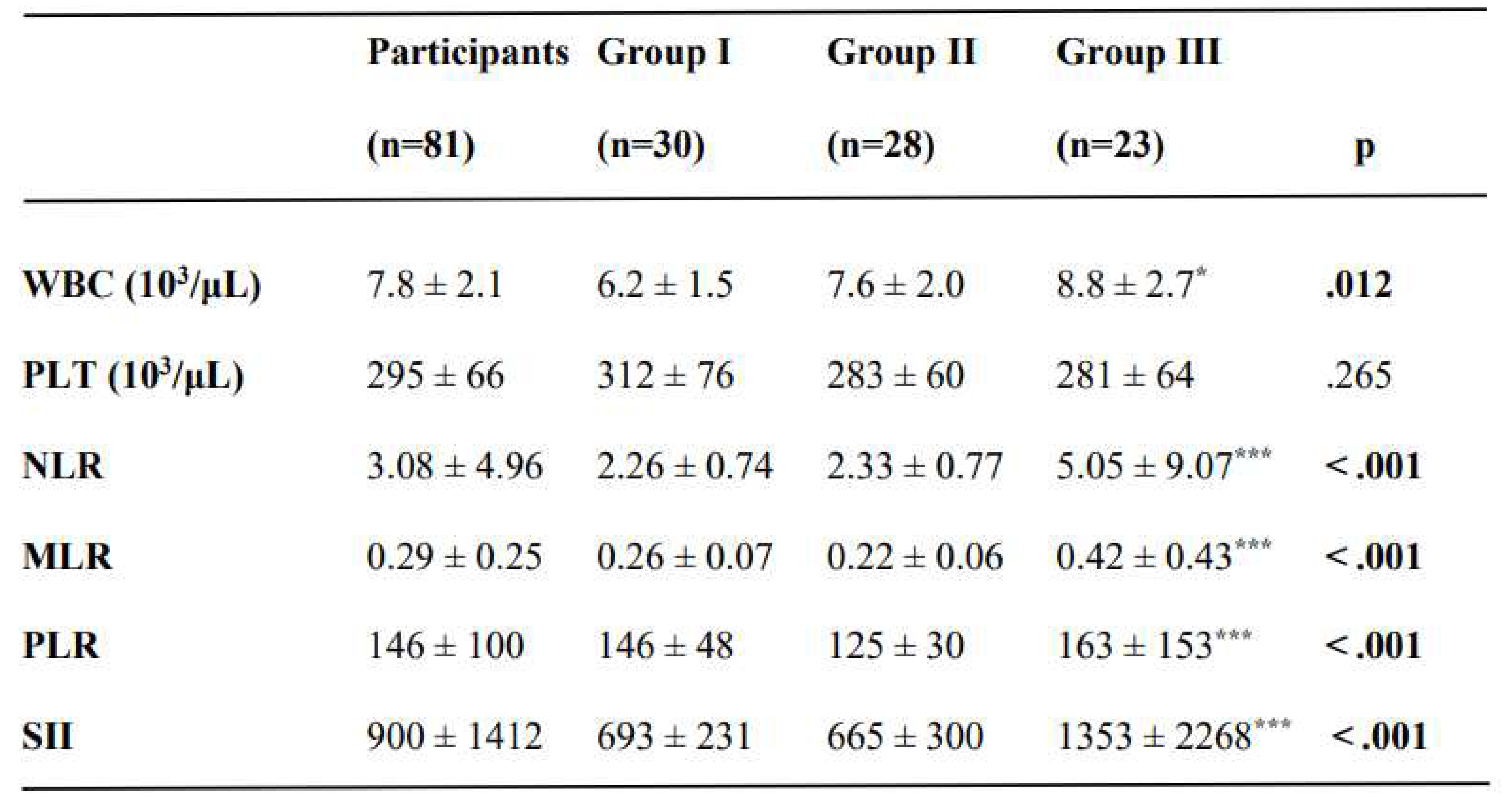

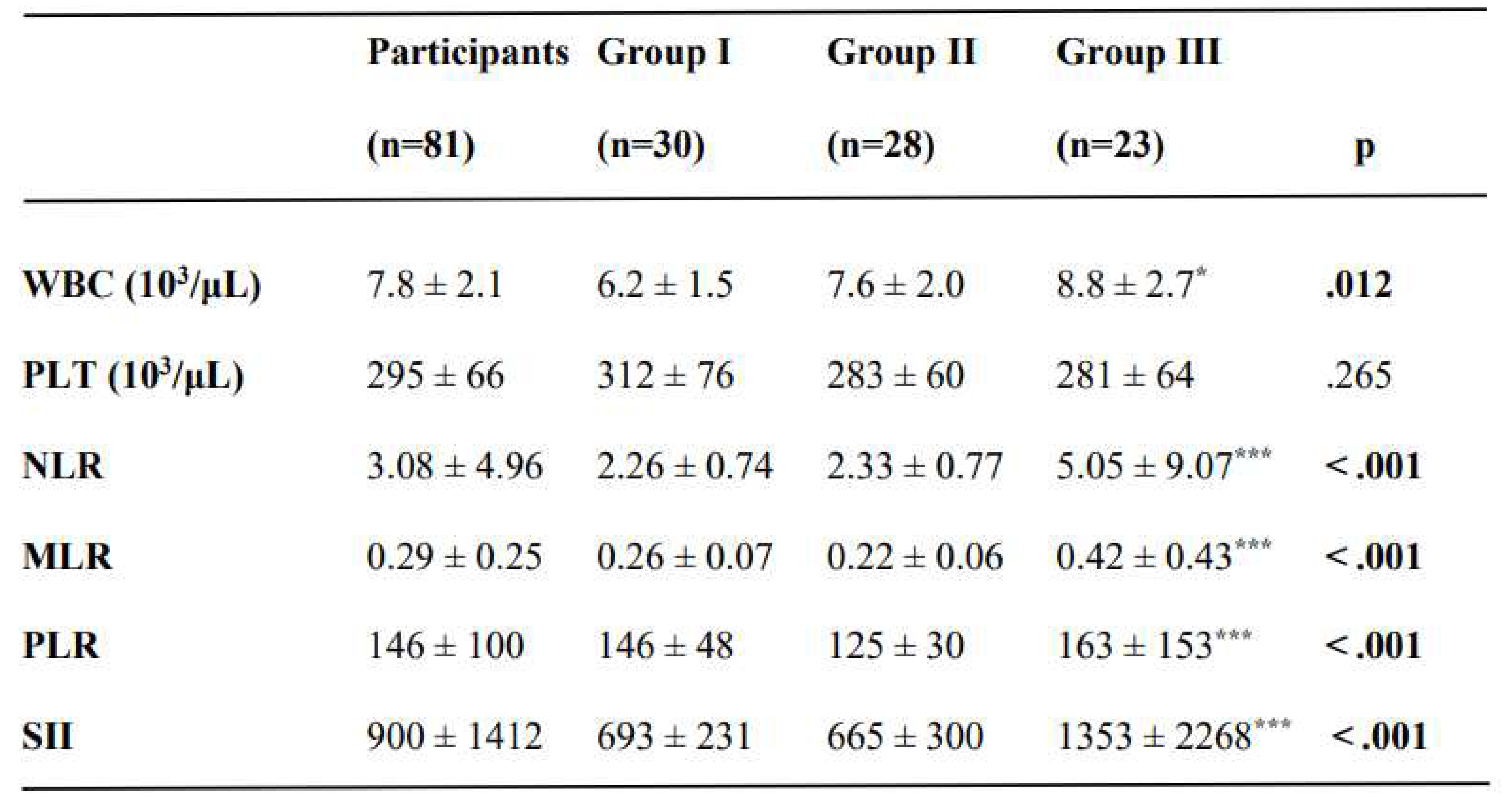

There was a slightly higher WBC count in CC group than in the CIN I group (p =.012) (

Table 2). The NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII were significantly higher in the CC group (p < .001). However, these were similar between CIN I and CIN II-III groups (

Table 2). The laboratory results of the participants are summarized in

Table 2.

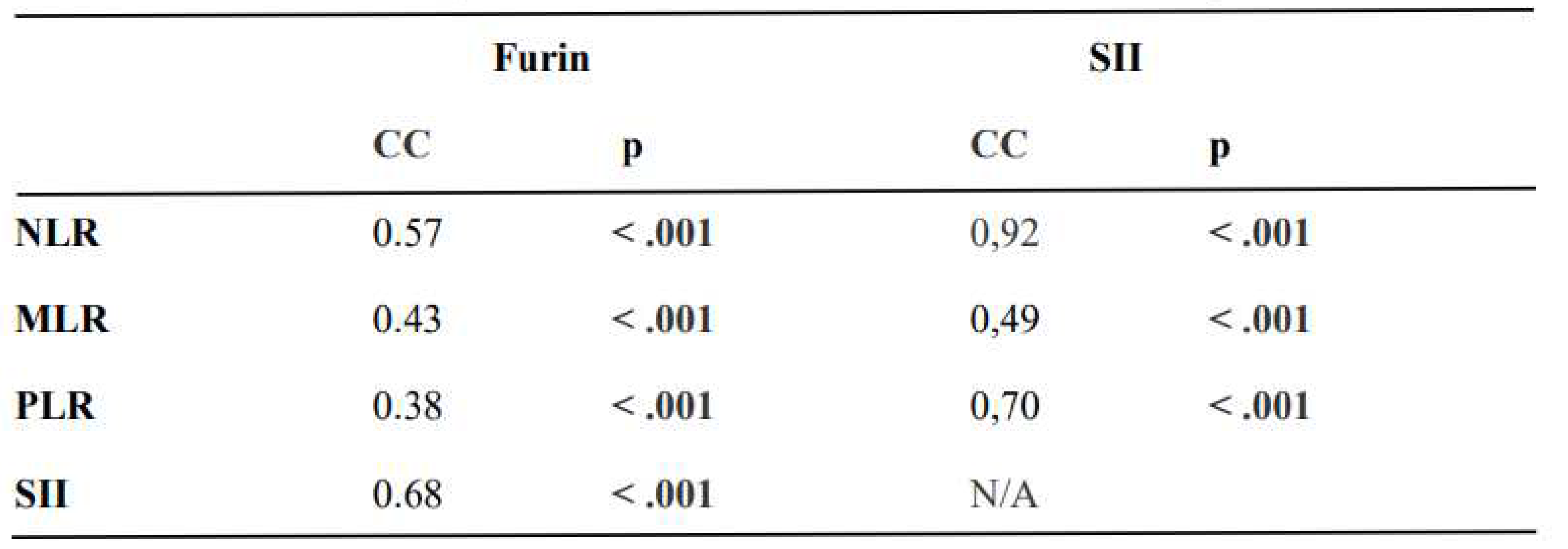

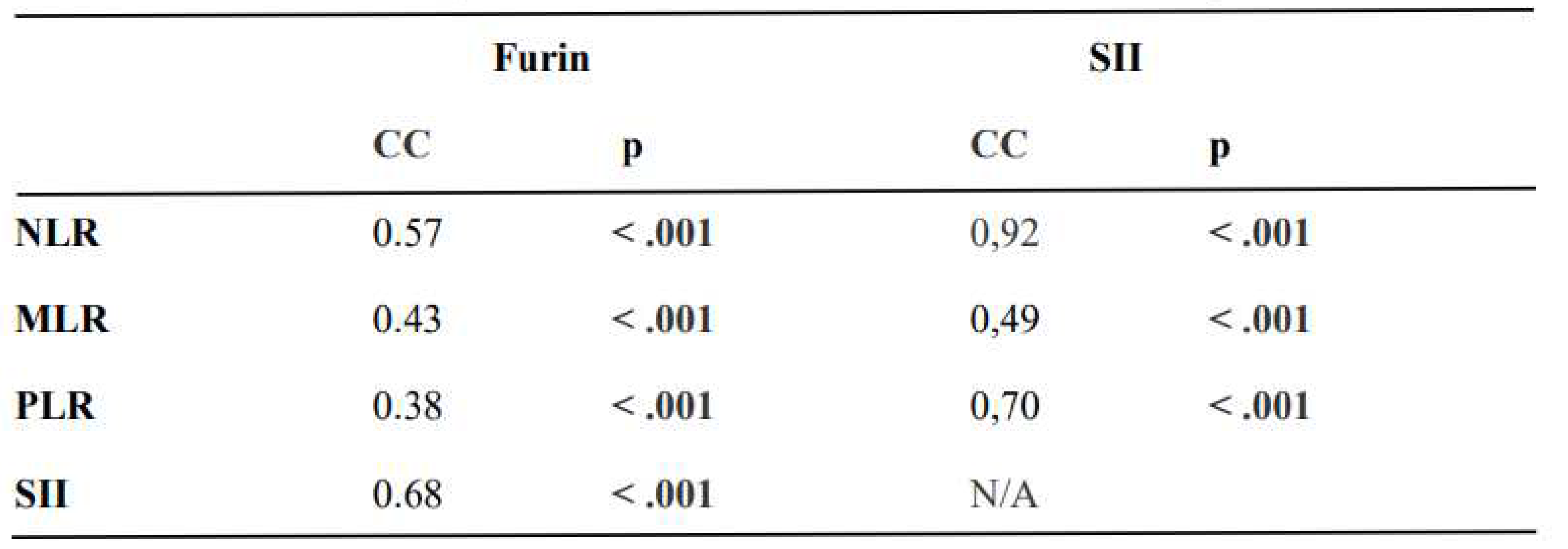

The expression of furin was moderately correlated with the NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII (rho: 0.57 p <.001; rho: 0.43 p <.001; rho: 0.38 p <.001; rho: 0.68 p <.001; respectively), and the SII was strongly correlated with the NLR and PLR (rho: 0.92 p <.001; rho: 0.70 p <.001; respectively) (

Table 3).

Table 3 summarizes the correlation analysis of furin and SII with the inflammatory indices.

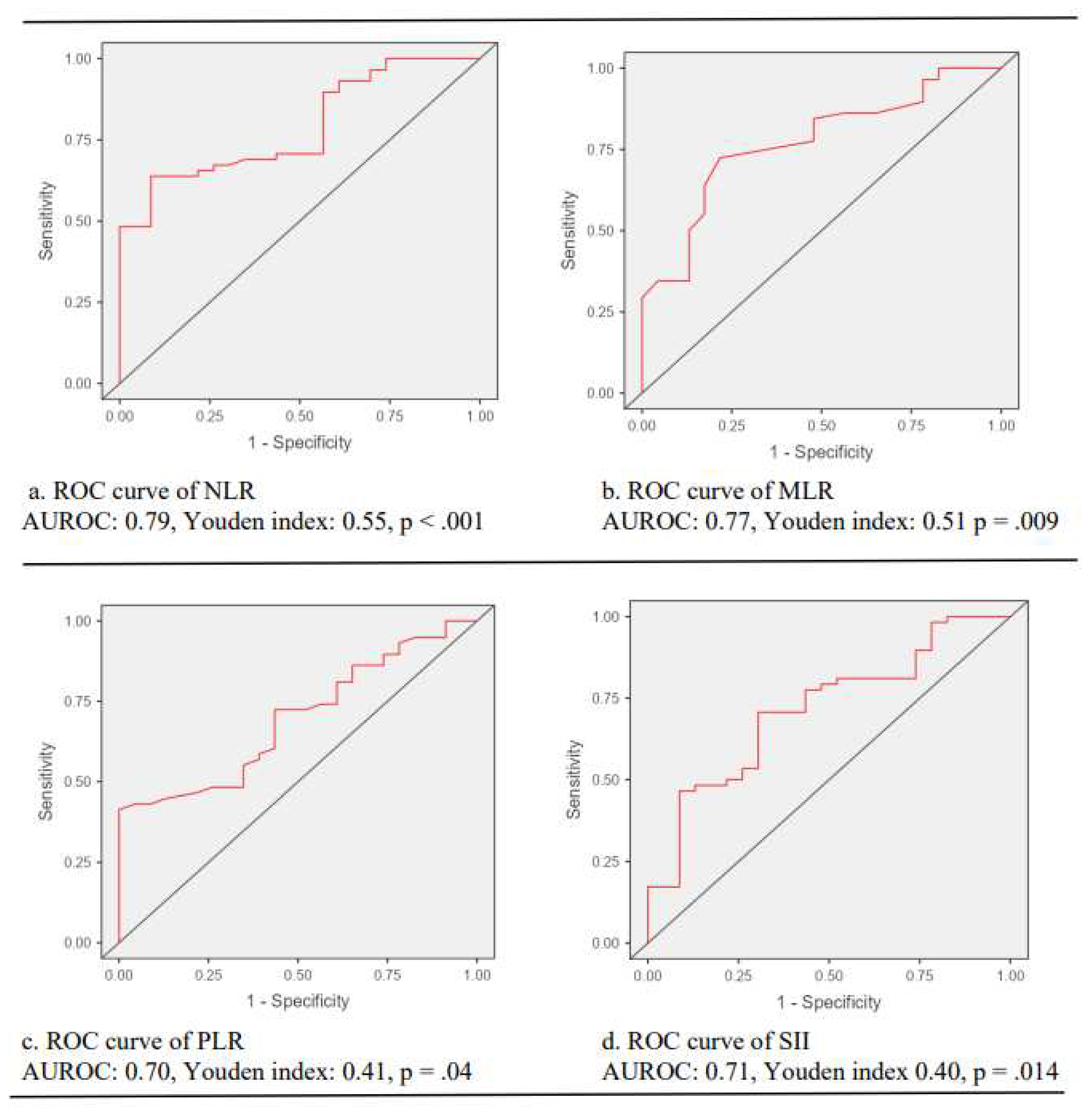

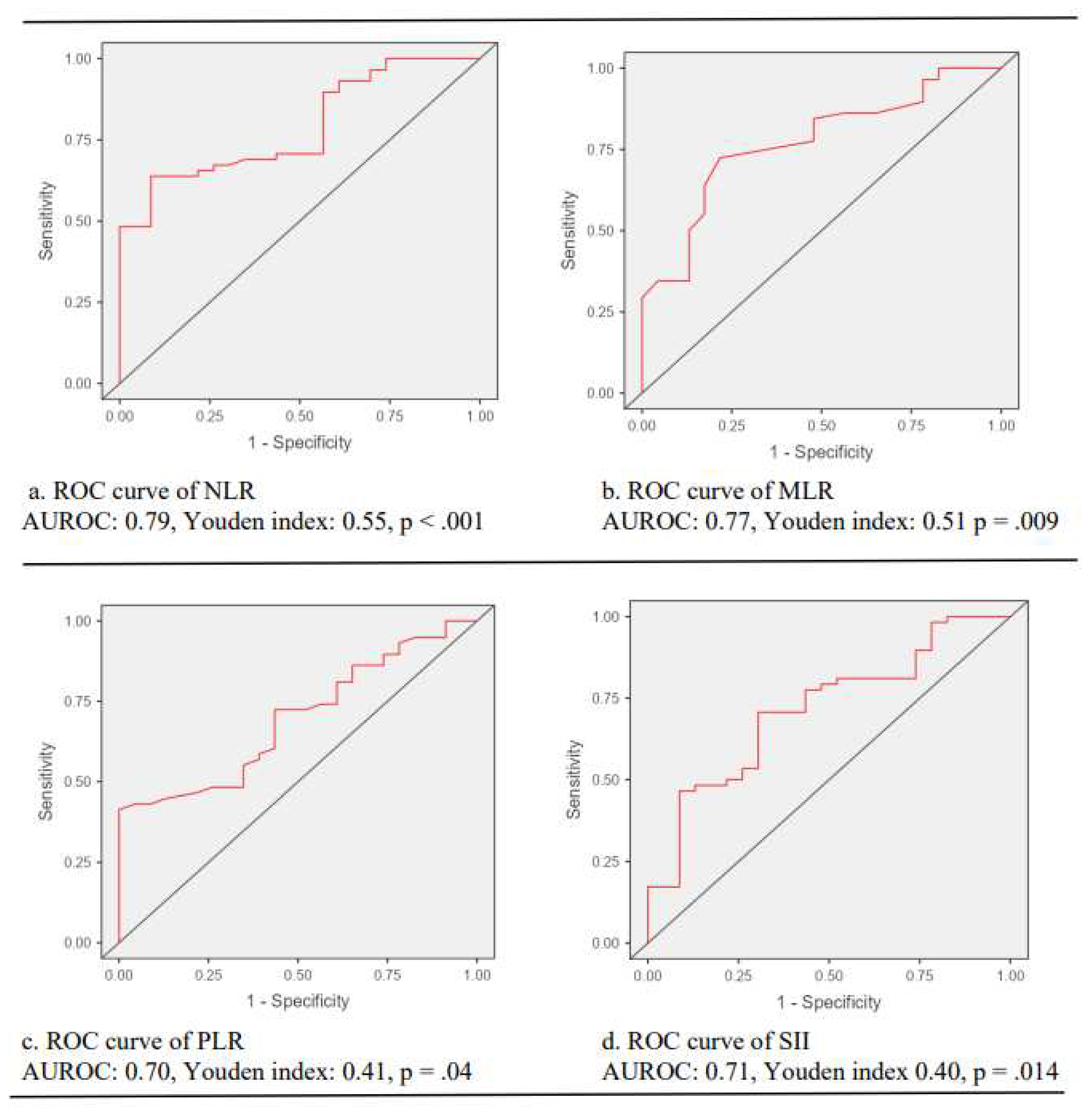

ROC curve analysis unveiled that NLR, MLR, PLR and SII predicted the presence of CC with a cutoff value of 2.39 for NLR (sensitivity: 91.3%, specificity: 63.8%, AUROC: 0.79, Youden index: 0.55, p < .001); a cutoff value of 0.27 for MLR (sensitivity: 78.3%, specificity: 72.4%, AUROC: 0.77, Youden index: 0.51, p = .009); a cutoff value of 123 for PLR (sensitivity: 100%, specificity: 41.4%, AUROC: 0.70, Youden index: 0.41, p = .04); and a cutoff value of 747 for SII (sensitivity: 69.6%, specificity: 90.7%, AUROC: 0.71, Youden index: 0.40, p = .014) (

Figure 2).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study evaluated the pathological and inflammatory markers of women with cervical epithelial neoplasia and cancer to elucidate the relationship of furin with inflammation while the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia progresses to cancer. The expression of furin increased stepwise along with the advancement of cervical dysplasia to cervical cancer, similar to p16 and ki-67. On the other hand, inflammatory indices were elevated only in women with cervical cancer but not in cervical dysplasia. Also, the inflammatory indices displayed good performance for discriminating the CC from cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

This study unveiled that the expression of furin was elevated in cervical cancer. Similarly, amplified furin expression has been revealed in gynecologic malignancies, especially in cervical and breast cancer, based on the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) studies. It is considered either a poor prognostic marker or a proto-oncogene (23-25).

Nonetheless, we could not find any paper in the literature that has argued for the importance of furin in preinvasive conditions; this study elucidated that a gradual increase in furin correlated with the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia to cervical cancer. It could be considered a new pathologic biomarker that signifies developing cervical cancer and denotes the severity of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; however, it needs to be supported by the following studies (26). Additionally, the current study confirmed the role of p16/ki-67 staining in the neoplastic progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, similar to that reported in the literature (27).

This study uncovered that even if inflammatory indices (NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII) were raised in women with cervical cancer, those stayed in the normal range in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Also, the inflammatory indices in this study displayed good discrimination performance for discriminating the CC from cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. The literature indicated that those could be independently used to distinguish the preinvasive lesions of larynx, cervix, and endometrium from invasive counterparts (28-30). Additionally, NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII could be used to predict certain cancer prognoses (11-19).

Although this study parallels the literature in differentiating preinvasive and malignant conditions, it opposes Xu and colleagues' study because they claimed that inflammatory indices could predict the severity of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (28-31). The laudable study of Li and colleagues disclosed the mystery of cervical TME in which HSIL tissue displayed amplified infiltration by lymphocytes and M1-like macrophages (32). Due to this reason, it could be speculated that the inflammatory indices are expected to be low in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. In addition, it was denoted that furin orchestrates myriad pathways in cancer and inflammatory cells that can ultimately hamper immune cell infiltration into the TME (33).

Conclusion

The current study revealed that furin expression increases gradually in parallel to the severity of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. The inflammatory indices (NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII) were higher in women with cervical cancer but similar in dysplasia groups. Inflammatory indices denoted good discrimination ability for the prediction of cervical cancer.

The limitations of the study

In addition to its retrospective nature, inflammatory indices are influenced by age, diet, activity level, and menstrual status. The limitations of this study include the absence of TILs, PD-L1, and furin mRNA expression in inflammatory and cervical cells in the study groups, which would make it easier to conclude the relationship between inflammation and cancer. As previously mentioned, little research has been conducted on the relationship between furin and preinvasive cervical disease; as a result, it could be assumed that the backlash of this study to conclude.

Figure 1.

The expression levels of furin in the cervical epithelium (x200). A. Weak furin expression in a woman with LSIL-CIN I (furin score 1). B. Moderate furin expression in a woman with CIN III (furin score 2). C. Strong furin expression in a woman with squamous cervical cancer (furin score 3).

Figure 1.

The expression levels of furin in the cervical epithelium (x200). A. Weak furin expression in a woman with LSIL-CIN I (furin score 1). B. Moderate furin expression in a woman with CIN III (furin score 2). C. Strong furin expression in a woman with squamous cervical cancer (furin score 3).

Figure 2.

The predictive performance of inflammatory indices on cervical cancer. Note. ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; AUROC, the area under the curve of receiver operating characteristic curve; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic immune inflammation index.

Figure 2.

The predictive performance of inflammatory indices on cervical cancer. Note. ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; AUROC, the area under the curve of receiver operating characteristic curve; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic immune inflammation index.

Table 1.

The pathological results of participants in the study groups.

Table 1.

The pathological results of participants in the study groups.

Table 2.

The laboratory results and inflammatory indices of women in the study groups.

Table 2.

The laboratory results and inflammatory indices of women in the study groups.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis of furin and SII with other biochemical parameters.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis of furin and SII with other biochemical parameters.

Author Contributions

Author 1: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, supervision Author 2: methodology, investigation, supervision Author 3: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing-review, and editing Author 4: visualization, validation, writing-review, and editing Author 5: validation, visualization, writing-review, and editing Author 6: conceptualization, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, supervision.

Funding

This study was funded by the Interdisciplinary Oncology Society (Izmir, Turkey).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This cross-sectional study was conducted in conformity with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki after ethical approval by the local ethical committee (94025189-050.03-40925).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, Eslahi M, Ginsburg O, Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health. 2023, 11, e197–e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kines RC, Schiller JT. Harnessing Human Papillomavirus' Natural Tropism to Target Tumors. Viruses. 2022, 14, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz L, Biryukov J, Conway MJ, Meyers C. Cleavage of the HPV16 Minor Capsid Protein L2 during Virion Morphogenesis Ablates the Requirement for Cellular Furin during De Novo Infection. Viruses. 2015, 7, 5813–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang JW, Roden RB. L2, the minor capsid protein of papillomavirus. Virology. 2013, 445, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck R, Turley SJ, Akhurst RJ. TGFβ biology in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021, 18, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé M, Pappalardo A, Soulet F, López JJ, Olaizola J, Leger Y, et al. Inactivation of proprotein convertases in T cells Inhibits PD-1 expression and creates a favorable immune microenvironment in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5008–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo DG, Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose M, Duhamel M, Rodet F, Salzet M. The role of proprotein convertases in the regulation of the function of immune cells in the oncoimmune response. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova ZM, Grönholm A, Kytölä V, Taverniti V, Hämäläinen S, Aittomäki S, et al. Myeloid cell-expressed proprotein convertase furin attenuates inflammation. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 54392–54404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Liu Q, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Lu X, Wu Y, Liu L. Prognostic Value of Preoperative Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Patients with Cervical Cancer. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong S, Dong L, Cheng L. Neutrophils in cancer carcinogenesis and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2021, 14, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupp MA, Cariolou M, Tzoulaki I, Aune D, Evangelou E, Berlanga-Taylor AJ. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cancer prognosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 360. [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasamy C, Tiwary V, Sunil K, Suresh D, Shetty S, Muthukaliannan GK, et al. Prognostic Utility of Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratio, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio and Monocyte-Lymphocyte Ratio in Head and Neck Cancers: A Detailed PRISMA Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Kaji S, Hayashi H, Sasaki Y, Kawakami K, et al. Novel inflammation-combined prognostic index to predict survival outcomes in patients with gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2023, 14, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi S, Basso M, Strippoli A, Schinzari G, D'Argento E, Larocca M, et al. Are Markers of Systemic Inflammation Good Prognostic Indicators in Colorectal Cancer? Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017, 16, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picarelli H, Yamaki VN, Solla DJF, Neville IS, Santos AGD, Freitas BSAG, et al. The preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predictive value for survival in patients with brain metastasis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022, 80, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li X, Zhang S, Lu J, Li C, Li N. The prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in surgical esophageal cancer patients: An updated meta-analysis. Front Surg. 2022, 9, 922595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji Y, Wang H. Prognostic prediction of systemic immune-inflammation index for patients with gynecological and breast cancers: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020, 18, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian BW, Yang YF, Yang CC, Yan LJ, Ding ZN, Liu H, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of cancer immunotherapy: systemic review and meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2022, 14, 1481–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, Chelmow D, Einstein MH, Garcia F, et al. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines Committee. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 102–131. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancakli Usta C, Altun E, Afsar S, Bulbul CB, Usta A, Adalı E. Overexpression of programmed cell death ligand 1 in patients with CIN and its correlation with human papillomavirus infection and CIN persistence. Infect Agent Cancer. 2020, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017, 23, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo X, Zhou X, Peng P, Yu M, Zhang Y, Yang J, et al. Identification of a six-gene signature for predicting the overall survival of cervical cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Chu J, Li J, Feng W, Yang F, Wang Y, et al. Cancer/testis antigen-Plac1 promotes invasion and metastasis of breast cancer through Furin/NICD/PTEN signaling pathway. Mol Oncol. 2018, 12, 1233–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López de Cicco R, Watson JC, Bassi DE, Litwin S, Klein-Szanto AJ. Simultaneous expression of furin and vascular endothelial growth factor in human oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 4480–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal R, Ghosh I, Banerjee D, Mittal S, Muwonge R, Roy C, et al. Correlation Between p16/Ki-67 Expression and the Grade of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasias. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2020, 39, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas M, Yavuz A, Ak M, Ozcelik B. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Discriminating Precancerous Pathologies from Cervical Cancer. J Oncol. 2019, 2019, 2476082. [Google Scholar]

- Kara A, Guven M, Demir D, Yilmaz MS, Gundogan ME, Genc S. Are calculated ratios and red blood cell and platelet distribution width really important for laryngeal cancer and precancerous larynx lesions? Niger J Clin Pract. 2019, 22, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acmaz G, Aksoy H, Unal D, Ozyurt S, Cingillioglu B, et al. Are neutrophil/lymphocyte and platelet/lymphocyte ratios associated with endometrial precancerous and cancerous lesions in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Song J. Elevated neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio can be a biomarker for predicting the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021, 100, e26335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li C, Hua K. Dissecting the Single-Cell Transcriptome Network of Immune Environment Underlying Cervical Premalignant Lesion, Cervical Cancer and Metastatic Lymph Nodes. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 897366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He Z, Khatib AM, Creemers JWM. The proprotein convertase furin in cancer: more than an oncogene. Oncogene. 2022, 41, 1252–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).