Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

07 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biomarkers in Neurological Diseases

2.1. Biomarkers for diagnosis

2.2. Biomarkers for disease progression

2.3. Biomarkers for treatment response

2.4. Predictive biomarkers

2.5. Prognostic biomarkers

3. Application of Imaging Biomarkers (IB) in Specific Neurological Diseases

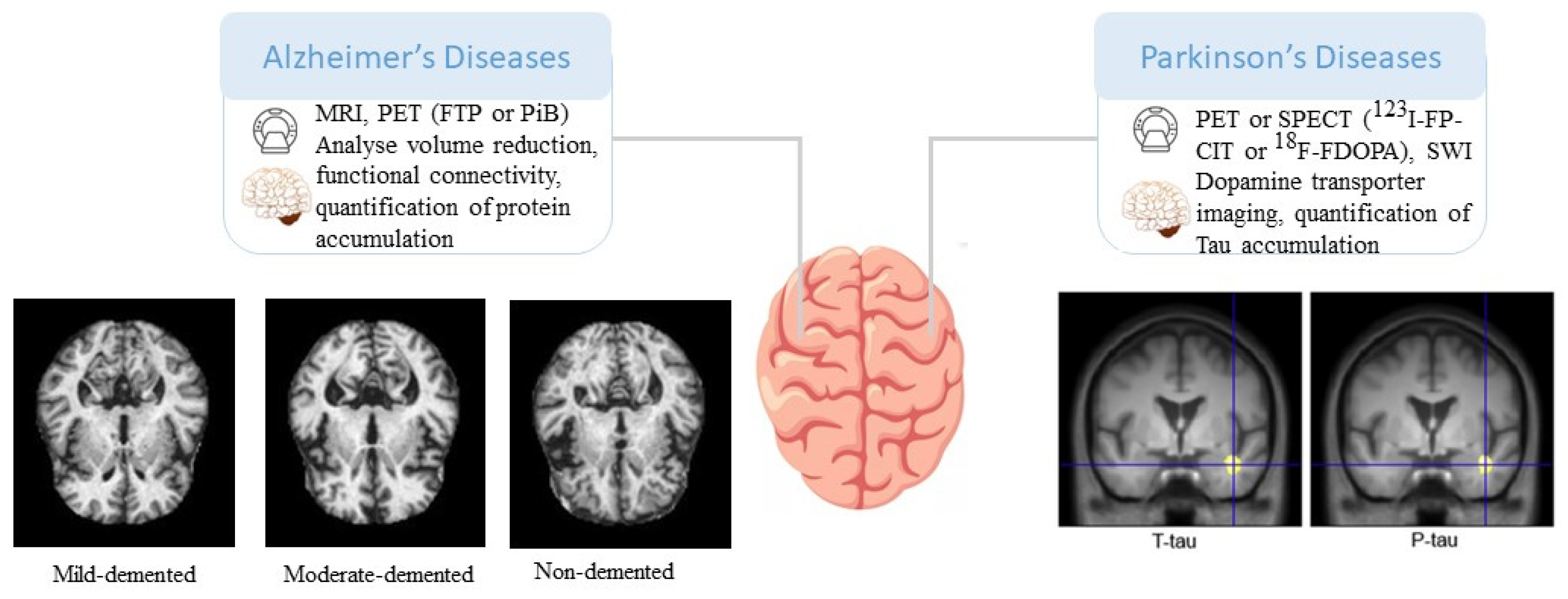

3.1. AD and other dementias

3.2. Parkinson's disease

3.3. Neuropsychiatric disorders

3.3.1. Major Depressive Disorder (MDD):

3.3.2. Schizophrenia:

3.3.3. Bipolar Disorder:

3.3.4. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD):

3.4. Epilepsy

3.5. Multiple sclerosis

3.6. Stroke

4. Challenges and Limitations

4.1. Technical limitations

4.2. Standardization and reproducibility

5. Future Directions and Potential Impact

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Korolev, I.O.; Symonds, L.L.; Bozoki, A.C. Predicting Progression from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Dementia Using Clinical, MRI, and Plasma Biomarkers via Probabilistic Pattern Classification. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0138866. [CrossRef]

- Vrenken, H.; Jenkinson, M.; Horsfield, M.A.; Battaglini, M.; van Schijndel, R.A.; Rostrup, E.; Geurts, J.J.G.; Fisher, E.; Zijdenbos, A.; Ashburner, J.; et al. Recommendations to Improve Imaging and Analysis of Brain Lesion Load and Atrophy in Longitudinal Studies of Multiple Sclerosis. J Neurol 2013, 260, 2458–2471. [CrossRef]

- Enzinger, C.; Barkhof, F.; Ciccarelli, O.; Filippi, M.; Kappos, L.; Rocca, M.A.; Ropele, S.; Rovira, À.; Schneider, T.; de Stefano, N.; et al. Nonconventional MRI and Microstructural Cerebral Changes in Multiple Sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2015, 11, 676–686. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, H.; de Sitter, A.; Bendfeldt, K.; Battaglini, M.; Gandini Wheeler-Kingshott, C.A.M.; Calabrese, M.; Geurts, J.J.G.; Rocca, M.A.; Sastre-Garriga, J.; Enzinger, C.; et al. Urgent Challenges in Quantification and Interpretation of Brain Grey Matter Atrophy in Individual MS Patients Using MRI. Neuroimage Clin 2018, 19, 466–475. [CrossRef]

- Jo, T.; Nho, K.; Saykin, A.J. Deep Learning in Alzheimer’s Disease: Diagnostic Classification and Prognostic Prediction Using Neuroimaging Data. Front Aging Neurosci 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, R.J.; Mourão-Miranda, J.; Schnack, H.G. Making Individual Prognoses in Psychiatry Using Neuroimaging and Machine Learning. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 798–808. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Hwang, Y. A Brief Review of Non-Invasive Brain Imaging Technologies and the near-Infrared Optical Bioimaging. Appl Microsc 2021, 51, 9. [CrossRef]

- Meijboom, R.; Wiseman, S.J.; York, E.N.; Bastin, M.E.; Valdés Hernández, M. del C.; Thrippleton, M.J.; Mollison, D.; White, N.; Kampaite, A.; Ng Kee Kwong, K.; et al. Rationale and Design of the Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol for FutureMS: A Longitudinal Multi-Centre Study of Newly Diagnosed Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis in Scotland. Wellcome Open Res 2022, 7, 94. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, F.-Y.; Yen, Y. Imaging Biomarkers for Clinical Applications in Neuro-Oncology: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Biomark Res 2023, 11, 35. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.T.S. Clinical Applications of Imaging Biomarkers. Part 1. The Neuroradiologist’s Perspective. Br J Radiol 2011, 84, S196–S204. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, T.; Sheelakumari, R.; James, J.S.; Mathuranath, P. A Review of Neuroimaging Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol Asia 2013, 18, 239–248, doi:25431627.

- Bachli, M.B.; Sedeño, L.; Ochab, J.K.; Piguet, O.; Kumfor, F.; Reyes, P.; Torralva, T.; Roca, M.; Cardona, J.F.; Campo, C.G.; et al. Evaluating the Reliability of Neurocognitive Biomarkers of Neurodegenerative Diseases across Countries: A Machine Learning Approach. Neuroimage 2020, 208, 116456. [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Cooper, A.J.; Thida, T.; Shinn, A.K.; Cohen, B.M.; Öngür, D. Myelin and Axon Abnormalities in Schizophrenia Measured with Magnetic Resonance Imaging Techniques. Biol Psychiatry 2013, 74, 451–457. [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Öngür, D. Probing Myelin and Axon Abnormalities Separately in Psychiatric Disorders Using MRI Techniques. Front Integr Neurosci 2013, 7. [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, S.; Wittfeld, K.; Habes, M.; Klinger-König, J.; Bülow, R.; Völzke, H.; Grabe, H.J. A Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Patterns of Regional Brain Atrophy. Front Psychiatry 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kynast, J.; Lampe, L.; Luck, T.; Frisch, S.; Arelin, K.; Hoffmann, K.-T.; Loeffler, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Villringer, A.; Schroeter, M.L. White Matter Hyperintensities Associated with Small Vessel Disease Impair Social Cognition beside Attention and Memory. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2018, 38, 996–1009. [CrossRef]

- Glover, G.H. Overview of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2011, 22, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.L.; Nicholson, T.R.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Bègue, I.; Butler, M.; Carson, A.J.; David, A.S.; Deeley, Q.; Diez, I.; Edwards, M.J.; et al. Neuroimaging in Functional Neurological Disorder: State of the Field and Research Agenda. Neuroimage Clin 2021, 30, 102623. [CrossRef]

- Ayubcha, C.; Revheim, M.-E.; Newberg, A.; Moghbel, M.; Rojulpote, C.; Werner, T.J.; Alavi, A. A Critical Review of Radiotracers in the Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Traumatic Brain Injury: FDG, Tau, and Amyloid Imaging in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021, 48, 623–641. [CrossRef]

- Uzuegbunam, B.C.; Librizzi, D.; Hooshyar Yousefi, B. PET Radiopharmaceuticals for Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis, the Current and Future Landscape. Molecules 2020, 25, 977. [CrossRef]

- Maschio, C.; Ni, R. Amyloid and Tau Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Tauopathies. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Beaurain, M.; Salabert, A.-S.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Arlicot, N.; Damier, P.; Le Jeune, F.; Demonet, J.-F.; Payoux, P. Innovative Molecular Imaging for Clinical Research, Therapeutic Stratification, and Nosography in Neuroscience. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Lavitrano, M.; Salvatore, E.; Combi, R. Molecular and Imaging Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Recent Insights. J Pers Med 2020, 10, 61. [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.-M.; Yuan, Z. PET/SPECT Molecular Imaging in Clinical Neuroscience: Recent Advances in the Investigation of CNS Diseases. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2015, 5, 433–447. [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Xie, F.; Zuo, C.; Guan, Y.; Huang, Y.H. PET Neuroimaging of Alzheimer’s Disease: Radiotracers and Their Utility in Clinical Research. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wallert, E.; Letort, E.; van der Zant, F.; Winogrodzka, A.; Berendse, H.; Beudel, M.; de Bie, R.; Booij, J.; Raijmakers, P.; van de Giessen, E. Comparison of [18F]-FDOPA PET and [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT Acquired in Clinical Practice for Assessing Nigrostriatal Degeneration in Patients with a Clinically Uncertain Parkinsonian Syndrome. EJNMMI Res 2022, 12, 68. [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.C.; Nathan, M.; Waldman, A.D.; Quigley, A.-M.; Schapira, A.H.; Buscombe, J. The Role of Functional Dopamine-Transporter SPECT Imaging in Parkinsonian Syndromes, Part 1. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2015, 36, 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Marner, L.; Korsholm, K.; Anderberg, L.; Lonsdale, M.N.; Jensen, M.R.; Brødsgaard, E.; Denholt, C.L.; Gillings, N.; Law, I.; Friberg, L. [18F]FE-PE2I PET Is a Feasible Alternative to [123I]FP-CIT SPECT for Dopamine Transporter Imaging in Clinically Uncertain Parkinsonism. EJNMMI Res 2022, 12, 56. [CrossRef]

- Palermo, G.; Giannoni, S.; Bellini, G.; Siciliano, G.; Ceravolo, R. Dopamine Transporter Imaging, Current Status of a Potential Biomarker: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11234. [CrossRef]

- Mazón, M.; Vázquez Costa, J.F.; Ten-Esteve, A.; Martí-Bonmatí, L. Imaging Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. The Example of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Neurosci 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jovicich, J.; Barkhof, F.; Babiloni, C.; Herholz, K.; Mulert, C.; Berckel, B.N.M.; Frisoni, G.B. Harmonization of Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Survey in the Imaging Community of Perceived Barriers and Suggested Actions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2019, 11, 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Napoli, E.; Kim, K.; McLennan, Y.; Hagerman, R.; Giulivi, C. Brain Atrophy and White Matter Damage Linked to Peripheral Bioenergetic Deficits in the Neurodegenerative Disease FXTAS. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9171. [CrossRef]

- Marino, S.; Bonanno, L.; Lo Buono, V.; Ciurleo, R.; Corallo, F.; Morabito, R.; Chirico, G.; Marra, A.; Bramanti, P. Longitudinal Analysis of Brain Atrophy in Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. Journal of International Medical Research 2019, 47, 5019–5027. [CrossRef]

- McWhinney, S.R.; Abé, C.; Alda, M.; Benedetti, F.; Bøen, E.; del Mar Bonnin, C.; Borgers, T.; Brosch, K.; Canales-Rodríguez, E.J.; Cannon, D.M.; et al. Association between Body Mass Index and Subcortical Brain Volumes in Bipolar Disorders–ENIGMA Study in 2735 Individuals. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6806–6819. [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, K.M.; Mullin, A.P.; Pustina, D.; Turner, E.C.; Burton, J.; Gordon, M.F.; Scahill, R.I.; Gantman, E.C.; Noble, S.; Romero, K.; et al. Recommendations to Optimize the Use of Volumetric MRI in Huntington’s Disease Clinical Trials. Front Neurol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.H.; Poudel, R.P.K.; Tsagkrasoulis, D.; Caan, M.W.A.; Steves, C.; Spector, T.D.; Montana, G. Predicting Brain Age with Deep Learning from Raw Imaging Data Results in a Reliable and Heritable Biomarker. Neuroimage 2017, 163, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C. V.; Tung, Y.-Y.; Chang, C. A Lifespan MRI Evaluation of Ventricular Enlargement in Normal Aging Mice. Neurobiol Aging 2011, 32, 2299–2307. [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, L.G.; Green, A.E.; Babakchanian, S.; Hwang, K.S.; Chou, Y.-Y.; Toga, A.W.; Thompson, P.M. Hippocampal Atrophy and Ventricular Enlargement in Normal Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012, 26, 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Geriatric Neurology; Nair, A.K., Sabbagh, M.N., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781118730676.

- Mak, E.; Su, L.; Williams, G.B.; Firbank, M.J.; Lawson, R.A.; Yarnall, A.J.; Duncan, G.W.; Mollenhauer, B.; Owen, A.M.; Khoo, T.K.; et al. Longitudinal Whole-Brain Atrophy and Ventricular Enlargement in Nondemented Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2017, 55, 78–90. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Editorial of Special Issue ‘Dissecting Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Diseases: Neurodegeneration and Neuroprotection.’ Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6991. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Fu, Z.; Calhoun, V.D. Classification and Prediction of Brain Disorders Using Functional Connectivity: Promising but Challenging. Front Neurosci 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Spinelli, E.G.; Cividini, C.; Agosta, F. Resting State Dynamic Functional Connectivity in Neurodegenerative Conditions: A Review of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. Front Neurosci 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Shen, G.; Wang, H.; Guan, Y. Brain Functional Connectivity Network Studies of Acupuncture: A Systematic Review on Resting-State FMRI. J Integr Med 2018, 16, 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Jonckers, E.; Van Audekerke, J.; De Visscher, G.; Van der Linden, A.; Verhoye, M. Functional Connectivity FMRI of the Rodent Brain: Comparison of Functional Connectivity Networks in Rat and Mouse. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18876. [CrossRef]

- Jonckers, E.; Van Audekerke, J.; De Visscher, G.; Van der Linden, A.; Verhoye, M. Functional Connectivity FMRI of the Rodent Brain: Comparison of Functional Connectivity Networks in Rat and Mouse. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18876. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, H.; WANG, S.; XING, J.; LIU, B.; MA, Z.; YANG, M.; ZHANG, Z.; TENG, G. Detection of PCC Functional Connectivity Characteristics in Resting-State FMRI in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease. Behavioural Brain Research 2009, 197, 103–108. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Cai, X.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Na, P.; Li, W. Functional Connectivity Markers of Depression in Advanced Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroimage Clin 2020, 25, 102130. [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Song, W.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, K.; Cao, B.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Gong, Q.; et al. Reduced Functional Connectivity in Early-Stage Drug-Naive Parkinson’s Disease: A Resting-State FMRI Study. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 431–441. [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, P.-J.; Perlbarg, V.; Bellec, P.; Desarnaud, S.; Lacomblez, L.; Doyon, J.; Habert, M.-O.; Benali, H. Resting State FDG-PET Functional Connectivity as an Early Biomarker of Alzheimer’s Disease Using Conjoint Univariate and Independent Component Analyses. Neuroimage 2012, 63, 936–946. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zheng, C.; Cui, B.; Qi, Z.; Zhao, Z.; An, Y.; Qiao, L.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, J. Multiparametric Imaging Hippocampal Neurodegeneration and Functional Connectivity with Simultaneous PET/MRI in Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2020, 47, 2440–2452. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, W.; Hu, J.; Li, B.; Ye, G.; Meng, H.; Huang, X.; et al. Disrupted Coupling between Salience Network Segregation and Glucose Metabolism Is Associated with Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease – A Simultaneous Resting-State FDG-PET/FMRI Study. Neuroimage Clin 2022, 34, 102977. [CrossRef]

- Pysz, M.A.; Gambhir, S.S.; Willmann, J.K. Molecular Imaging: Current Status and Emerging Strategies. Clin Radiol 2010, 65, 500–516. [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.-M.; Yuan, Z. PET/SPECT Molecular Imaging in Clinical Neuroscience: Recent Advances in the Investigation of CNS Diseases. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2015, 5, 433–447. [CrossRef]

- Okamura, N.; Harada, R.; Furumoto, S.; Arai, H.; Yanai, K.; Kudo, Y. Tau PET Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2014, 14, 500. [CrossRef]

- Leuzy, A.; Cicognola, C.; Chiotis, K.; Saint-Aubert, L.; Lemoine, L.; Andreasen, N.; Zetterberg, H.; Ye, K.; Blennow, K.; Höglund, K.; et al. Longitudinal Tau and Metabolic PET Imaging in Relation to Novel CSF Tau Measures in Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019, 46, 1152–1163. [CrossRef]

- Valli, M.; Mihaescu, A.; Strafella, A.P. Imaging Behavioural Complications of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Imaging Behav 2019, 13, 323–332. [CrossRef]

- Xian, W.; Shi, X.; Luo, G.; Yi, C.; Zhang, X.; Pei, Z. Co-Registration Analysis of Fluorodopa and Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography for Differentiating Multiple System Atrophy Parkinsonism Type From Parkinson’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hemond, C.C.; Glanz, B.I.; Bakshi, R.; Chitnis, T.; Healy, B.C. The Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratios Are Independently Associated with Neurological Disability and Brain Atrophy in Multiple Sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2019, 19, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; Tian, F.; Zhao, X.; Pu, X.-P.; Sun, G.-B.; Sun, X.-B. Anti-Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Effects of Notoginsenoside R1 on Small Molecule Metabolism in Rat Brain after Ischemic Stroke as Visualized by MALDI–MS Imaging. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 129, 110470. [CrossRef]

- Thomalla, G.; Rossbach, P.; Rosenkranz, M.; Siemonsen, S.; Krützelmann, A.; Fiehler, J.; Gerloff, C. Negative Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery Imaging Identifies Acute Ischemic Stroke at 3 Hours or Less. Ann Neurol 2009, 65, 724–732. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. The National Institute on Aging—Alzheimer’s Association Framework on Alzheimer’s Disease: Application to Clinical Trials. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2019, 15, 172–178. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.C.; Huston, J.; Jack, C.R.; Glaser, K.J.; Manduca, A.; Felmlee, J.P.; Ehman, R.L. Decreased Brain Stiffness in Alzheimer’s Disease Determined by Magnetic Resonance Elastography. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2011, 34, 494–498. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-D.; Yang, R.; Yan, C.-G.; Chen, X.; Bai, T.-J.; Bo, Q.-J.; Chen, G.-M.; Chen, N.-X.; Chen, T.-L.; Chen, W.; et al. Disrupted Hemispheric Connectivity Specialization in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: Evidence from the REST-Meta-MDD Project. J Affect Disord 2021, 284, 217–228. [CrossRef]

- Köhler-Forsberg, K.; Jorgensen, A.; Dam, V.H.; Stenbæk, D.S.; Fisher, P.M.; Ip, C.-T.; Ganz, M.; Poulsen, H.E.; Giraldi, A.; Ozenne, B.; et al. Predicting Treatment Outcome in Major Depressive Disorder Using Serotonin 4 Receptor PET Brain Imaging, Functional MRI, Cognitive-, EEG-Based, and Peripheral Biomarkers: A NeuroPharm Open Label Clinical Trial Protocol. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, P.B.; Srithiran, A.; Benitez, J.; Daskalakis, Z.Z.; Oxley, T.J.; Kulkarni, J.; Egan, G.F. An FMRI Study of Prefrontal Brain Activation during Multiple Tasks in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 2008, 29, 490–501. [CrossRef]

- Paloyelis, Y.; Mehta, M.A.; Kuntsi, J.; Asherson, P. Functional MRI in ADHD: A Systematic Literature Review. Expert Rev Neurother 2007, 7, 1337–1356. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.-Z.; Zang, Y.-F.; Cao, Q.-J.; Yan, C.-G.; He, Y.; Jiang, T.-Z.; Sui, M.-Q.; Wang, Y.-F. Fisher Discriminative Analysis of Resting-State Brain Function for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuroimage 2008, 40, 110–120. [CrossRef]

- Amen, D.G.; Henderson, T.A.; Newberg, A. SPECT Functional Neuroimaging Distinguishes Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder From Healthy Controls in Big Data Imaging Cohorts. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Stojanovski, S.; Felsky, D.; Viviano, J.D.; Shahab, S.; Bangali, R.; Burton, C.L.; Devenyi, G.A.; O’Donnell, L.J.; Szatmari, P.; Chakravarty, M.M.; et al. Polygenic Risk and Neural Substrates of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms in Youths With a History of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Biol Psychiatry 2019, 85, 408–416. [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.; Wu, J. Case Report: Neuroimaging Analysis of Pediatric ADHD-Related Symptoms Secondary to Hypoxic Brain Injury. Brain Inj 2019, 33, 1402–1407. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, C.C.; Bourgeat, P.; Ellis, K.A.; Brown, B.; Lim, Y.Y.; Mulligan, R.; Jones, G.; Maruff, P.; Woodward, M.; Price, R.; et al. Predicting Alzheimer Disease with Β-amyloid Imaging: Results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyle Study of Ageing. Ann Neurol 2013, 74, 905–913. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, H.; Risacher, S.L.; Kim, S.; Inlow, M.; Moore, J.H.; Saykin, A.J.; Shen, L. Network-Guided Sparse Learning for Predicting Cognitive Outcomes from MRI Measures. In; 2013; pp. 202–210. [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, V.; Ciolac, D.; Gonzalez-Escamilla, G.; Grothe, M.; Strauss, S.; Molina Galindo, L.S.; Radetz, A.; Salmen, A.; Lukas, C.; Klotz, L.; et al. Subcortical Volumes as Early Predictors of Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2022, 91, 192–202. [CrossRef]

- Young, P.N.E.; Estarellas, M.; Coomans, E.; Srikrishna, M.; Beaumont, H.; Maass, A.; Venkataraman, A. V.; Lissaman, R.; Jiménez, D.; Betts, M.J.; et al. Imaging Biomarkers in Neurodegeneration: Current and Future Practices. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020, 12, 49. [CrossRef]

- Bottani, M.; Banfi, G.; Lombardi, G. The Clinical Potential of Circulating MiRNAs as Biomarkers: Present and Future Applications for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Age-Associated Bone Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 589. [CrossRef]

- Kamagata, K.; Andica, C.; Kato, A.; Saito, Y.; Uchida, W.; Hatano, T.; Lukies, M.; Ogawa, T.; Takeshige-Amano, H.; Akashi, T.; et al. Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5216. [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.K.; Alexander, R.C.; Welsh-Bohmer, K.A.; Culp, M.; Chiang, C.; O’Neil, J.; Evans, R.M.; Harrigan, P.; Plassman, B.L.; Burke, J.R.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Pioglitazone for the Delay of Cognitive Impairment in People at Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease (TOMMORROW): A Prognostic Biomarker Study and a Phase 3, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 537–547. [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, R.; Damian, A. Brain SPECT as a Biomarker of Neurodegeneration in Dementia in the Era of Molecular Imaging: Still a Valid Option? Front Neurol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sasabayashi, D.; Koike, S.; Nakajima, S.; Hirano, Y. Editorial: Prognostic Imaging Biomarkers in Psychotic Disorders. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Sutphen, C.L.; Fagan, A.M.; Holtzman, D.M. Progress Update: Fluid and Imaging Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol Psychiatry 2014, 75, 520–526. [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.; Atassi, N. Positron Emission Tomography Molecular Imaging Biomarkers for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Neurol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, R.; Giorgio, A.; Severa, G.; De Stefano, N. MRI Prognostic Factors in Multiple Sclerosis, Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder, and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Antibody Disease. Front Neurol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Melhem, E.R. MR Imaging Biomarkers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Acad Radiol 2017, 24, 1185–1186. [CrossRef]

- Kotian, R.P.; Koteshwar, P. FA Characteristics as Imaging Biomarkers Among the Indian Population in Early Parkinson’s Disease. In Diffusion Tensor Imaging and Fractional Anisotropy; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 131–153. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, N.; Pettemeridou, E.; Stamatakis, E.A.; Seimenis, I.; Constantinidou, F. Altered Resting Functional Connectivity Is Related to Cognitive Outcome in Males With Moderate-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurol 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, M.; Aswendt, M. Structure–Function Relationship of Cerebral Networks in Experimental Neuroscience: Contribution of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Exp Neurol 2013, 242, 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Zaragori, T.; Filosa, R.; Ovdiichuk, O.; Beaumont, M.; Collet, C.; Roeder, E.; Martin, B.; Maskali, F.; Barberi-Heyob, M.; et al. Multi-Tracer and Multiparametric PET Imaging to Detect the IDH Mutation in Glioma: A Preclinical Translational in Vitro, in Vivo, and Ex Vivo Study. Cancer Imaging 2022, 22, 16. [CrossRef]

- Stafstrom, C.E.; Carmant, L. Seizures and Epilepsy: An Overview for Neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Wu, R.; Yuan, J.; He, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; et al. Automatic Brain Structure Segmentation for 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Images via Deep Learning. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023, 13, 4447–4462. [CrossRef]

- Flores, S.; Chen, C.D.; Su, Y.; Dincer, A.; Keefe, S.J.; Perez-Carrillo, G.G.; Hornbeck, R.C.; Goyal, M.S.; Vlassenko, A.G.; Schwarz, S.; et al. Characteristics and Quantitative Impact of Off-target Skull Binding in Tau PET Studies of Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2022, 18. [CrossRef]

- Veitch, D.P.; Weiner, M.W.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; DeCarli, C.; Green, R.C.; Harvey, D.; Jack, C.R.; Jagust, W.; Landau, S.M.; et al. Using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative to Improve Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2022, 18, 824–857. [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.; Sabbagh, M. Amyloid Imaging: Poised for Integration into Medical Practice. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.T.; Herholz, K. Amyloid Imaging for Dementia in Clinical Practice. BMC Med 2015, 13, 163. [CrossRef]

- Lois, C.; Gonzalez, I.; Johnson, K.A.; Price, J.C. PET Imaging of Tau Protein Targets: A Methodology Perspective. Brain Imaging Behav 2019, 13, 333–344. [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, S.; Frings, L.; Bormann, T.; Vach, W.; Buchert, R.; Meyer, P.T. Amyloid Imaging for Differential Diagnosis of Dementia: Incremental Value Compared to Clinical Diagnosis and [18F]FDG PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019, 46, 312–323. [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, R.; Nelissen, N.; Salmon, E.; Ivanoiu, A.; Hasselbalch, S.; Andersen, A.; Korner, A.; Minthon, L.; Brooks, D.J.; Van Laere, K.; et al. Binary Classification of 18F-Flutemetamol PET Using Machine Learning: Comparison with Visual Reads and Structural MRI. Neuroimage 2013, 64, 517–525. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Chen, T.-F.; Chiu, M.-J.; Yen, R.-F.; Shih, M.-C.; Lin, C.-H. Integrated 18F-T807 Tau PET, Structural MRI, and Plasma Tau in Tauopathy Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Cimini, A.; Camedda, R.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Schillaci, O. Tau Biomarkers in Dementia: Positron Emission Tomography Radiopharmaceuticals in Tauopathy Assessment and Future Perspective. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13002. [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.; Mak, E.; Cervenka, S.; Aigbirhio, F.I.; Rowe, J.B.; O’Brien, J.T. In Vivo Tau PET Imaging in Dementia: Pathophysiology, Radiotracer Quantification, and a Systematic Review of Clinical Findings. Ageing Res Rev 2017, 36, 50–63. [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, S.H.; Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Babajani-Feremi, A. Identification of the Early Stage of Alzheimer’s Disease Using Structural MRI and Resting-State FMRI. Front Neurol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Farina, F.R.; Emek-Savaş, D.D.; Rueda-Delgado, L.; Boyle, R.; Kiiski, H.; Yener, G.; Whelan, R. A Comparison of Resting State EEG and Structural MRI for Classifying Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neuroimage 2020, 215, 116795. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, F.; Yan, H.; Wang, K.; Ma, Y.; Shen, L.; Xu, M. A Multi-Model Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Automatic Hippocampus Segmentation and Classification in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroimage 2020, 208, 116459. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, L.; Igel, C.; Liv Hansen, N.; Osler, M.; Lauritzen, M.; Rostrup, E.; Nielsen, M. Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease Using M <scp>RI</Scp> Hippocampal Texture. Hum Brain Mapp 2016, 37, 1148–1161. [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Fox, N.C.; Jack, C.R.; Scheltens, P.; Thompson, P.M. The Clinical Use of Structural MRI in Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2010, 6, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, R.; Fleisher, A.S.; Reiman, E.M.; Guan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Yao, L. Altered Default Mode Network Connectivity in Alzheimer’s Disease-A Resting Functional MRI and Bayesian Network Study. Hum Brain Mapp 2011, 32, 1868–1881. [CrossRef]

- Eyler, L.T.; Elman, J.A.; Hatton, S.N.; Gough, S.; Mischel, A.K.; Hagler, D.J.; Franz, C.E.; Docherty, A.; Fennema-Notestine, C.; Gillespie, N.; et al. Resting State Abnormalities of the Default Mode Network in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2019, 70, 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Wallert, E.; Letort, E.; van der Zant, F.; Winogrodzka, A.; Berendse, H.; Beudel, M.; de Bie, R.; Booij, J.; Raijmakers, P.; van de Giessen, E. Comparison of [18F]-FDOPA PET and [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT Acquired in Clinical Practice for Assessing Nigrostriatal Degeneration in Patients with a Clinically Uncertain Parkinsonian Syndrome. EJNMMI Res 2022, 12, 68. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lao-Kaim, N.P.; Roussakis, A.-A.; Martín-Bastida, A.; Valle-Guzman, N.; Paul, G.; Soreq, E.; Daws, R.E.; Foltynie, T.; Barker, R.A.; et al. Longitudinal Functional Connectivity Changes Related to Dopaminergic Decline in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroimage Clin 2020, 28, 102409. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, K.; Chan, P. Changes of Functional Connectivity of the Motor Network in the Resting State in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci Lett 2009, 460, 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Shine, J.M.; Muller, A.J.; O’Callaghan, C.; Hornberger, M.; Halliday, G.M.; Lewis, S.J. Abnormal Connectivity between the Default Mode and the Visual System Underlies the Manifestation of Visual Hallucinations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Task-Based FMRI Study. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2015, 1, 15003. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Ren, L.; Li, T.; Pu, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Song, C.; Liang, Z. The Impact of Anxiety on the Cognitive Function of Informal Parkinson’s Disease Caregiver: Evidence from Task-Based and Resting-State FNIRS. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.B.; Miller-Patterson, C. PD and DLB: Brain Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. In; 2019; pp. 167–185. [CrossRef]

- Cerasa, A.; Pugliese, P.; Messina, D.; Morelli, M.; Cecilia Gioia, M.; Salsone, M.; Novellino, F.; Nicoletti, G.; Arabia, G.; Quattrone, A. Prefrontal Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease with Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia during FMRI Motor Task. Movement Disorders 2012, 27, 364–371. [CrossRef]

- Troisi Lopez, E.; Minino, R.; Liparoti, M.; Polverino, A.; Romano, A.; De Micco, R.; Lucidi, F.; Tessitore, A.; Amico, E.; Sorrentino, G.; et al. Fading of Brain Network Fingerprint in Parkinson’s Disease Predicts Motor Clinical Impairment. Hum Brain Mapp 2023, 44, 1239–1250. [CrossRef]

- Herz, D.M.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Løkkegaard, A.; Siebner, H.R. Functional Neuroimaging of Motor Control in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 2014, 35, 3227–3237. [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.; Badoud, S.; Nguyen, D.; Barnaure, I.; Montandon, M.-L.; Lovblad, K.-O.; Burkhard, P. Differentiation between Parkinson Disease and Other Forms of Parkinsonism Using Support Vector Machine Analysis of Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI): Initial Results. Eur Radiol 2013, 23, 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, E.; Mueller, C.; Pinter, B.; Krismer, F.; Scherfler, C.; Esterhammer, R.; Kremser, C.; Schocke, M.; Wenning, G.K.; Poewe, W.; et al. Dorsolateral Nigral Hyperintensity on 3.0T Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging in Neurodegenerative Parkinsonism. Movement Disorders 2015, 30, 1068–1076. [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.J.; Song, Y.S.; Choi, B.S.; Kim, J.-M.; Nam, Y.; Kim, J.H. Comparison of Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging and Susceptibility Map-Weighted Imaging for the Diagnosis of Parkinsonism with Nigral Hyperintensity. Eur J Radiol 2021, 134, 109398. [CrossRef]

- Tuite, P. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as a Potential Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Brain Sci 2017, 7, 68. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-H.D.; Chiu, S.-C.; Lu, C.-S.; Yen, T.-C.; Weng, Y.-H. Fully Automated Quantification of the Striatal Uptake Ratio of [ 99m Tc]-TRODAT with SPECT Imaging: Evaluation of the Diagnostic Performance in Parkinson’s Disease and the Temporal Regression of Striatal Tracer Uptake. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Capotosti, F.; Vokali, E.; Molette, J.; Ravache, M.; Delgado, C.; Kocher, J.; Pittet, L.; Dimitrakopoulos, I.K.; Di-Bonaventura, I.; Touilloux, T.; et al. The Development of [ 18 F]ACI-12589, a High Affinity and Selective Alpha-synuclein Radiotracer, as a Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease and Other Synucleinopathies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2021, 17. [CrossRef]

- Kotzbauer, P.T.; Tu, Z.; Mach, R.H. Current Status of the Development of PET Radiotracers for Imaging Alpha Synuclein Aggregates in Lewy Bodies and Lewy Neurites. Clin Transl Imaging 2017, 5, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Sachin, K.; Sourabh, S. Alzheimer MRI Preprocessed Dataset. Data set. Kaggle 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mak, E.; Su, L.; Williams, G.B.; Firbank, M.J.; Lawson, R.A.; Yarnall, A.J.; Duncan, G.W.; Mollenhauer, B.; Owen, A.M.; Khoo, T.K.; et al. Longitudinal Whole-Brain Atrophy and Ventricular Enlargement in Nondemented Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2017, 55, 78–90. [CrossRef]

- Javaheripour, N.; Li, M.; Chand, T.; Krug, A.; Kircher, T.; Dannlowski, U.; Nenadić, I.; Hamilton, J.P.; Sacchet, M.D.; Gotlib, I.H.; et al. Altered Resting-State Functional Connectome in Major Depressive Disorder: A Mega-Analysis from the PsyMRI Consortium. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 511. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; She, S.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Hu, H.; Zheng, W.; Huang, R.; Wu, H. Multi-Modal MRI Measures Reveal Sensory Abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder Patients: A Surface-Based Study. Neuroimage Clin 2023, 39, 103468. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, D.; Yan, G.; Hou, K. Association between Fasting Blood Glucose and Thyroid Stimulating Hormones and Suicidal Tendency and Disease Severity in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2022, 22, 635–642. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Guan, M.; Ren, X.; Li, D.; Yin, K.; Zhou, P.; Li, B.; Wang, H. Increased Thalamic Gray Matter Volume Induced by Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Treatment in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Karlsgodt, K.H.; Sun, D.; Cannon, T.D. Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Schizophrenia. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2010, 19, 226–231. [CrossRef]

- Cetin-Karayumak, S.; Di Biase, M.A.; Chunga, N.; Reid, B.; Somes, N.; Lyall, A.E.; Kelly, S.; Solgun, B.; Pasternak, O.; Vangel, M.; et al. White Matter Abnormalities across the Lifespan of Schizophrenia: A Harmonized Multi-Site Diffusion MRI Study. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 3208–3219. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ke, P.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Xiong, D.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Ning, Y.; Duan, X.; et al. Multimodal Magnetic Resonance Imaging Reveals Aberrant Brain Age Trajectory During Youth in Schizophrenia Patients. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hu, N.; Zhang, W.; Tao, B.; Dai, J.; Gong, Y.; Tan, Y.; Cai, D.; Lui, S. Dysconnectivity of Multiple Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis of Resting-State Functional Connectivity. Front Psychiatry 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Podwalski, P.; Szczygieł, K.; Tyburski, E.; Sagan, L.; Misiak, B.; Samochowiec, J. Magnetic Resonance Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Psychiatry: A Narrative Review of Its Potential Role in Diagnosis. Pharmacological Reports 2021, 73, 43–56. [CrossRef]

- Chitty, K.M.; Lagopoulos, J.; Lee, R.S.C.; Hickie, I.B.; Hermens, D.F. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Mismatch Negativity in Bipolar Disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 23, 1348–1363. [CrossRef]

- Lagopoulos, J.; Hermens, D.F.; Hatton, S.N.; Tobias-Webb, J.; Griffiths, K.; Naismith, S.L.; Scott, E.M.; Hickie, I.B. Microstructural White Matter Changes in the Corpus Callosum of Young People with Bipolar Disorder: A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59108. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.J.; Johnson, C.P.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Christensen, G.E.; Wemmie, J.A.; Magnotta, V.A. Impaired Sensory Processing Measured by Functional MRI in Bipolar Disorder Manic and Depressed Mood States. Brain Imaging Behav 2018, 12, 837–847. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-F.; Forrest, L.N.; Kuykendall, M.D.; Prescot, A.P.; Sung, Y.-H.; Huber, R.S.; Hellem, T.L.; Jeong, E.-K.; Renshaw, P.F.; Kondo, D.G. Anterior Cingulate Cortex Choline Levels in Female Adolescents with Unipolar versus Bipolar Depression: A Potential New Tool for Diagnosis. J Affect Disord 2014, 167, 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Magnotta, V.A.; Xu, J.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Williams, A.; Shaffer, J.; Christensen, G.; Long, J.D.; Taylor, E.; Sathyaputri, L.; Richards, J.G.; et al. Metabolic Abnormalities in the Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum in Bipolar Disorder: A Multi-Modal MR Study. J Affect Disord 2022, 301, 390–399. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hua, M.; Qin, J.; Tang, Q.; Han, Y.; Tian, H.; Lian, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; et al. Disrupted Pathways from Frontal-Parietal Cortex to Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum in Patients with Unmedicated Obsessive Compulsive Disorder as Observed by Whole-Brain Resting-State Effective Connectivity Analysis – a Small Sample Pilot Study. Brain Imaging Behav 2021, 15, 1344–1354. [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A.; Sarkar, S. Neuroimaging Studies in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Narrative Review. Indian J Psychol Med 2016, 38, 386–394. [CrossRef]

- Picó-Pérez, M.; Moreira, P.S.; de Melo Ferreira, V.; Radua, J.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Sousa, N.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Morgado, P. Modality-Specific Overlaps in Brain Structure and Function in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Multimodal Meta-Analysis of Case-Control MRI Studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, 112, 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Boedhoe, P.S.W.; Heymans, M.W.; Schmaal, L.; Abe, Y.; Alonso, P.; Ameis, S.H.; Anticevic, A.; Arnold, P.D.; Batistuzzo, M.C.; Benedetti, F.; et al. An Empirical Comparison of Meta- and Mega-Analysis With Data From the ENIGMA Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Working Group. Front Neuroinform 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Sharp, W.; Sudre, G.; Wharton, A.; Greenstein, D.; Raznahan, A.; Evans, A.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Lerch, J.P.; Rapoport, J. Subcortical and Cortical Morphological Anomalies as an Endophenotype in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 224–231. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, Q.; Chen, R.; Manssuer, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; et al. Mechanisms Underlying Capsulotomy for Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Neural Correlates of Negative Affect Processing Overlap with Deep Brain Stimulation Targets. Mol Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cendes, F.; Theodore, W.H.; Brinkmann, B.H.; Sulc, V.; Cascino, G.D. Neuroimaging of Epilepsy. In; 2016; pp. 985–1014.

- Álvarez-Linera Prado, J. Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Epilepsy. Radiología (English Edition) 2012, 54, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Sone, D.; Beheshti, I.; Maikusa, N.; Ota, M.; Kimura, Y.; Sato, N.; Koepp, M.; Matsuda, H. Neuroimaging-Based Brain-Age Prediction in Diverse Forms of Epilepsy: A Signature of Psychosis and Beyond. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 825–834. [CrossRef]

- Memarian, N.; Thompson, P.M.; Engel, J.; Staba, R.J. Quantitative Analysis of Structural Neuroimaging of Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Imaging Med 2013, 5. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, H.S.; Aarabi, M.H.; Mehvari-Habibabadi, J.; Sharifpour, R.; Mohajer, B.; Mohammadi-Mobarakeh, N.; Hashemi-Fesharaki, S.S.; Elisevich, K.; Nazem-Zadeh, M.-R. Distinct Patterns of Hippocampal Subfield Volume Loss in Left and Right Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Neurological Sciences 2021, 42, 1411–1421. [CrossRef]

- van Graan, L.A.; Lemieux, L.; Chaudhary, U.J. Methods and Utility of EEG-FMRI in Epilepsy. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2015, 5, 300–312. [CrossRef]

- Centeno, M.; Carmichael, D.W. Network Connectivity in Epilepsy: Resting State FMRI and EEG–fMRI Contributions. Front Neurol 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Shams, M.; Rahimpour Jounghani, A.; Fayaz, F.; Mirbagheri, M.; Hakimi, N.; Rajabion, L.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Localizing Confined Epileptic Foci in Patients with an Unclear Focus or Presumed Multifocality Using a Component-Based EEG-FMRI Method. Cogn Neurodyn 2021, 15, 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, S.M.; Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Shams, M.; Seraji, M.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Localization of Epileptic Foci Based on Simultaneous EEG–FMRI Data. Front Neurol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Saharkhiz, S.; Rajabion, L.; Oskouei, H.B.; Seraji, M.; Fayaz, F.; Saliminia, S.; Sadjadi, S.M.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Simultaneous Electroencephalography-Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Assessment of Human Brain Function. Front Syst Neurosci 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Scheid, B.H.; Bernabei, J.M.; Khambhati, A.N.; Mouchtaris, S.; Jeschke, J.; Bassett, D.S.; Becker, D.; Davis, K.A.; Lucas, T.; Doyle, W.; et al. Intracranial Electroencephalographic Biomarker Predicts Effective Responsive Neurostimulation for Epilepsy Prior to Treatment. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 652–662. [CrossRef]

- Sparacia, G.; Parla, G.; Lo Re, V.; Cannella, R.; Mamone, G.; Carollo, V.; Midiri, M.; Grasso, G. Resting-State Functional Connectome in Patients with Brain Tumors Before and After Surgical Resection. World Neurosurg 2020, 141, e182–e194. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Guo, X.; Liao, W.; Tang, Y.-L.; Chen, H. Abnormal Dynamics of Functional Connectivity Density in Children with Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes. Brain Imaging Behav 2019, 13, 985–994. [CrossRef]

- Juhász, C.; Mittal, S. Molecular Imaging of Brain Tumor-Associated Epilepsy. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 1049. [CrossRef]

- Marcille, M.; Hurtado Rúa, S.; Tyshkov, C.; Jaywant, A.; Comunale, J.; Kaunzner, U.W.; Nealon, N.; Perumal, J.S.; Zexter, L.; Zinger, N.; et al. Disease Correlates of Rim Lesions on Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping in Multiple Sclerosis. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4411. [CrossRef]

- Kaunzner, U.W.; Kang, Y.; Monohan, E.; Kothari, P.J.; Nealon, N.; Perumal, J.; Vartanian, T.; Kuceyeski, A.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Mozley, P.D.; et al. Reduction of PK11195 Uptake Observed in Multiple Sclerosis Lesions after Natalizumab Initiation. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017, 15, 27–33. [CrossRef]

- Hemond, C.C.; Bakshi, R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, N.; Boffa, G.; Inglese, M. Ultra-High-Field 7-T MRI in Multiple Sclerosis and Other Demyelinating Diseases: From Pathology to Clinical Practice. Eur Radiol Exp 2020, 4, 59. [CrossRef]

- Lorefice, L.; Fenu, G.; Pitzalis, R.; Scalas, G.; Frau, J.; Coghe, G.; Musu, L.; Sechi, V.; Barracciu, M.A.; Marrosu, M.G.; et al. Autoimmune Comorbidities in Multiple Sclerosis: What Is the Influence on Brain Volumes? A Case–Control MRI Study. J Neurol 2018, 265, 1096–1101. [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Tu, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Li, J. Diffusion Tensor Imaging Revealed Microstructural Changes in Normal-Appearing White Matter Regions in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Front Neurosci 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Mustafi, S.M.; Harezlak, J.; Kodiweera, C.; Randolph, J.S.; Ford, J.C.; Wishart, H.A.; Wu, Y.-C. Detecting White Matter Alterations in Multiple Sclerosis Using Advanced Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neural Regen Res 2019, 14, 114–123. [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, J.; Uryu, K.; Fujihara, K.; Wattjes, M.P.; Suzuki, C.; Nakashima, I. Measurements of the Corpus Callosum Index and Fractional Anisotropy of the Corpus Callosum and Their Cutoff Values Are Useful to Assess Global Brain Volume Loss in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 45, 102388. [CrossRef]

- Naismith, R.T.; Xu, J.; Tutlam, N.T.; Scully, P.T.; Trinkaus, K.; Snyder, A.Z.; Song, S.K.; Cross, A.H. Increased Diffusivity in Acute Multiple Sclerosis Lesions Predicts Risk of Black Hole. Neurology 2010, 74, 1694–1701. [CrossRef]

- Storelli, L.; Azzimonti, M.; Gueye, M.; Vizzino, C.; Preziosa, P.; Tedeschi, G.; De Stefano, N.; Pantano, P.; Filippi, M.; Rocca, M.A. A Deep Learning Approach to Predicting Disease Progression in Multiple Sclerosis Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest Radiol 2022, 57, 423–432. [CrossRef]

- Airas, L.; Rissanen, E.; Rinne, J.O. Imaging Neuroinflammation in Multiple Sclerosis Using TSPO-PET. Clin Transl Imaging 2015, 3, 461–473. [CrossRef]

- Morbelli, S.; Bauckneht, M.; Capitanio, S.; Pardini, M.; Roccatagliata, L.; Nobili, F. A New Frontier for Amyloid PET Imaging: Multiple Sclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019, 46, 276–279. [CrossRef]

- Birenbaum, D.; Bancroft, L.W.; Felsberg, G.J. Imaging in Acute Stroke. West J Emerg Med 2011, 12, 67–76, doi:Birenbaum et al., 2011.

- Potter, C.A.; Vagal, A.S.; Goyal, M.; Nunez, D.B.; Leslie-Mazwi, T.M.; Lev, M.H. CT for Treatment Selection in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Code Stroke Primer. RadioGraphics 2019, 39, 1717–1738. [CrossRef]

- Muir, K.W. Imaging of Acute Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005, 76, iii19–iii28. [CrossRef]

- Saba, L.; Anzidei, M.; Marincola, B.C.; Piga, M.; Raz, E.; Bassareo, P.P.; Napoli, A.; Mannelli, L.; Catalano, C.; Wintermark, M. Imaging of the Carotid Artery Vulnerable Plaque. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2014, 37, 572–585. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Yoon, H.Y.; Jang, H.J.; Song, S.; Kim, W.; Park, J.; Lee, K.E.; Jeon, S.; Lee, S.; Lim, D.-K.; et al. Dual-Modal Imaging-Guided Precise Tracking of Bioorthogonally Labeled Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Mouse Brain Stroke. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 10991–11007. [CrossRef]

- Sodaei, F.; Shahmaei, V. Identification of Penumbra in Acute Ischemic Stroke Using Multimodal MR Imaging Analysis: A Case Report Study. Radiol Case Rep 2020, 15, 2041–2046. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kang, H.; Yoon, H.J.; Chung, B.M.; Shin, N.-Y. Deep Learning–Based Image Reconstruction for Brain CT: Improved Image Quality Compared with Adaptive Statistical Iterative Reconstruction-Veo (ASIR-V). Neuroradiology 2021, 63, 905–912. [CrossRef]

- Degnan, A.J.; Gallagher, G.; Teng, Z.; Lu, J.; Liu, Q.; Gillard, J.H. MR Angiography and Imaging for the Evaluation of Middle Cerebral Artery Atherosclerotic Disease. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2012, 33, 1427–1435. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.C. V; Ma, H.; Ringleb, P.A.; Parsons, M.W.; Churilov, L.; Bendszus, M.; Levi, C.R.; Hsu, C.; Kleinig, T.J.; Fatar, M.; et al. Extending Thrombolysis to 4·5–9 h and Wake-up Stroke Using Perfusion Imaging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. The Lancet 2019, 394, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Aeschbacher, S.; Blum, S.; Meyre, P.B.; Coslovsky, M.; Vischer, A.S.; Sinnecker, T.; Rodondi, N.; Beer, J.H.; Moschovitis, G.; Moutzouri, E.; et al. Blood Pressure and Brain Lesions in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Hypertension 2021, 77, 662–671. [CrossRef]

- Demeestere, J.; Wouters, A.; Christensen, S.; Lemmens, R.; Lansberg, M.G. Review of Perfusion Imaging in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 1017–1024. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.K.; Shin, W.; Parikh, V.S.; Ragin, A.; Mouannes, J.; Bernstein, R.A.; Walker, M.T.; Bhatt, H.; Carroll, T.J. Quantitative Cerebral MR Perfusion Imaging: Preliminary Results in Stroke. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2010, 32, 796–802. [CrossRef]

- Tarpley, J.; Franc, D.; Tansy, A.P.; Liebeskind, D.S. Use of Perfusion Imaging and Other Imaging Techniques to Assess Risks/Benefits of Acute Stroke Interventions. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2013, 15, 336. [CrossRef]

- Scalzo, F.; Nour, M.; Liebeskind, D.S. Data Science of Stroke Imaging and Enlightenment of the Penumbra. Front Neurol 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

| Neurological Disorders | Imaging-based Biomarkers |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer's disease | Amyloid PET imaging, Tau PET imaging, Hippocampal volume, Cortical thickness, Functional connectivity disruption, FDG-PET hypometabolism |

| Parkinson's disease | DaTscan SPECT imaging, Dopamine transporter imaging, Substantia nigra hyperechogenicity, Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) alterations, Functional connectivity changes |

| Depression | Prefrontal cortex alterations, Hippocampal volume reduction, Amygdala hyperactivity, Default mode network dysfunction, Serotonin transporter imaging |

| Epilepsy | Hippocampal sclerosis on MRI, Cortical dysplasia on MRI, Epileptic network characterization using functional connectivity, PET/SPECT imaging for seizure focus localization |

| Multiple Sclerosis | Corticospinal tract degeneration on DTI, Whole-brain atrophy, Motor cortex hyperexcitability on fMRI, Hypometabolism on FDG-PET, Functional connectivity alterations |

| Stroke | Infarct volume and location on MRI, Perfusion imaging for assessment of ischemic penumbra, Collateral circulation evaluation, Functional connectivity changes, Vascular imaging (CTA/MRA) for stenosis/occlusion detection |

| Imaging Technique | Role |

|---|---|

| Non-contrast CT | Rapidly detects acute ischemic changes and differentiates between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Provides information about the location and extent of early ischemic changes. |

| CT Angiography (CTA) | Visualizes blood vessels in the brain and identifies occlusions or stenosis. Helps determine the underlying cause of stroke. |

| MRI | Provides detailed information about brain structure and differentiates between stroke subtypes |

| Diffusion-Weighted Imaging | Detects acute ischemic lesions within minutes of stroke onset. Provides information about affected brain tissue and helps determine tissue viability. |

| Perfusion-Weighted Imaging | Assesses cerebral blood flow and identifies areas of hypoperfusion or ischemia. Aids in estimating the extent of the penumbra |

| Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) | Provides detailed images of blood vessels. Helps visualize vessel occlusion or stenosis and determine treatment approach. |

| Perfusion Imaging (CT or MRI) | Provides quantitative measures of cerebral blood flow. Assists in assessing tissue viability and determining the extent of the ischemic penumbra. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).