Submitted:

06 September 2023

Posted:

07 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

“A comparison of the different gene arrangements in the same chromosome may, in certain cases, throw light on the historical relationships of these structures, and consequently on the history of the species as a whole.” Dobzhansky & Sturtevant, 1938, Genetics [1].

A (very) brief history of phylogenetics

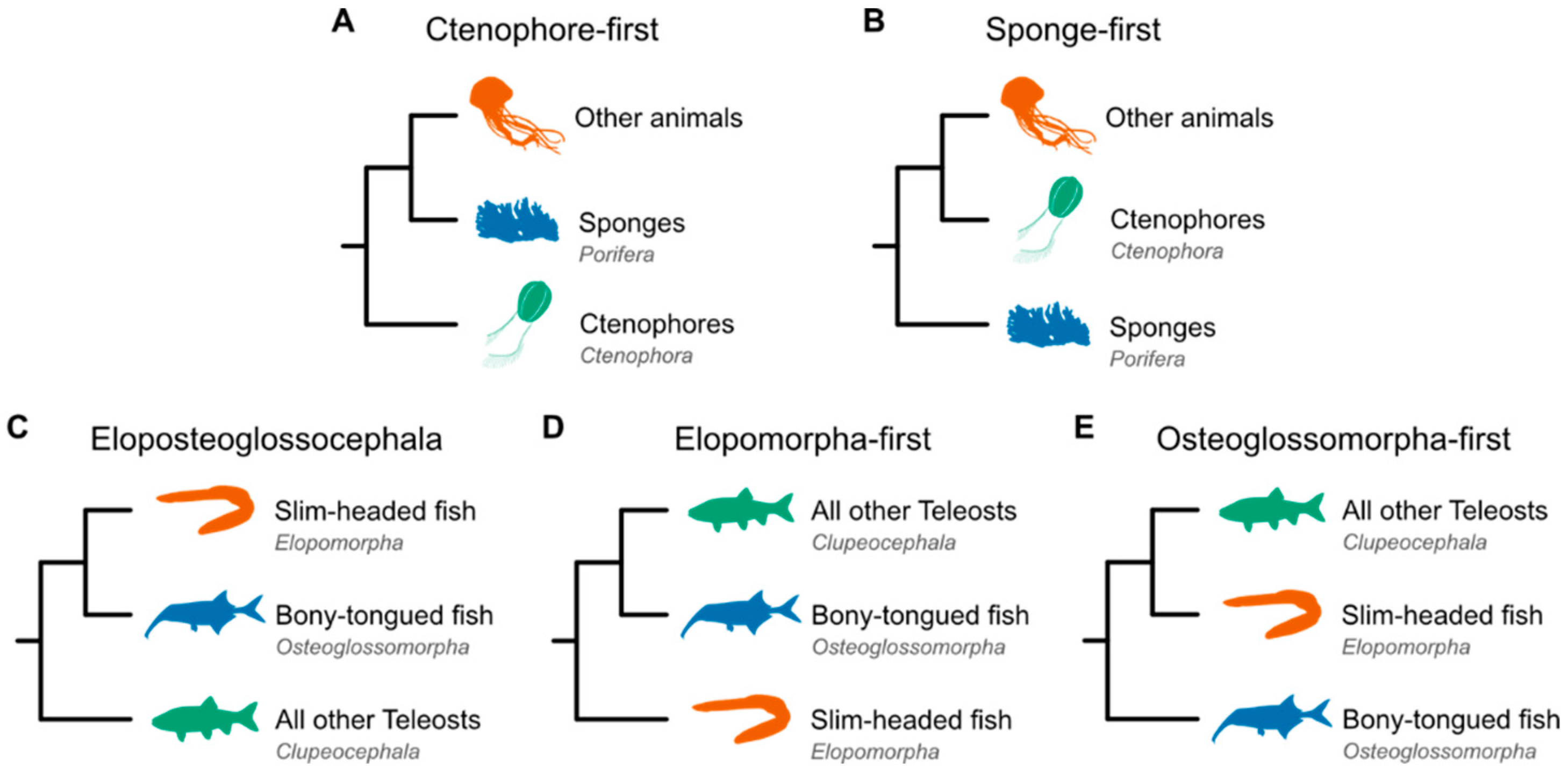

Current approaches fail to resolve certain branches in the Tree of Life

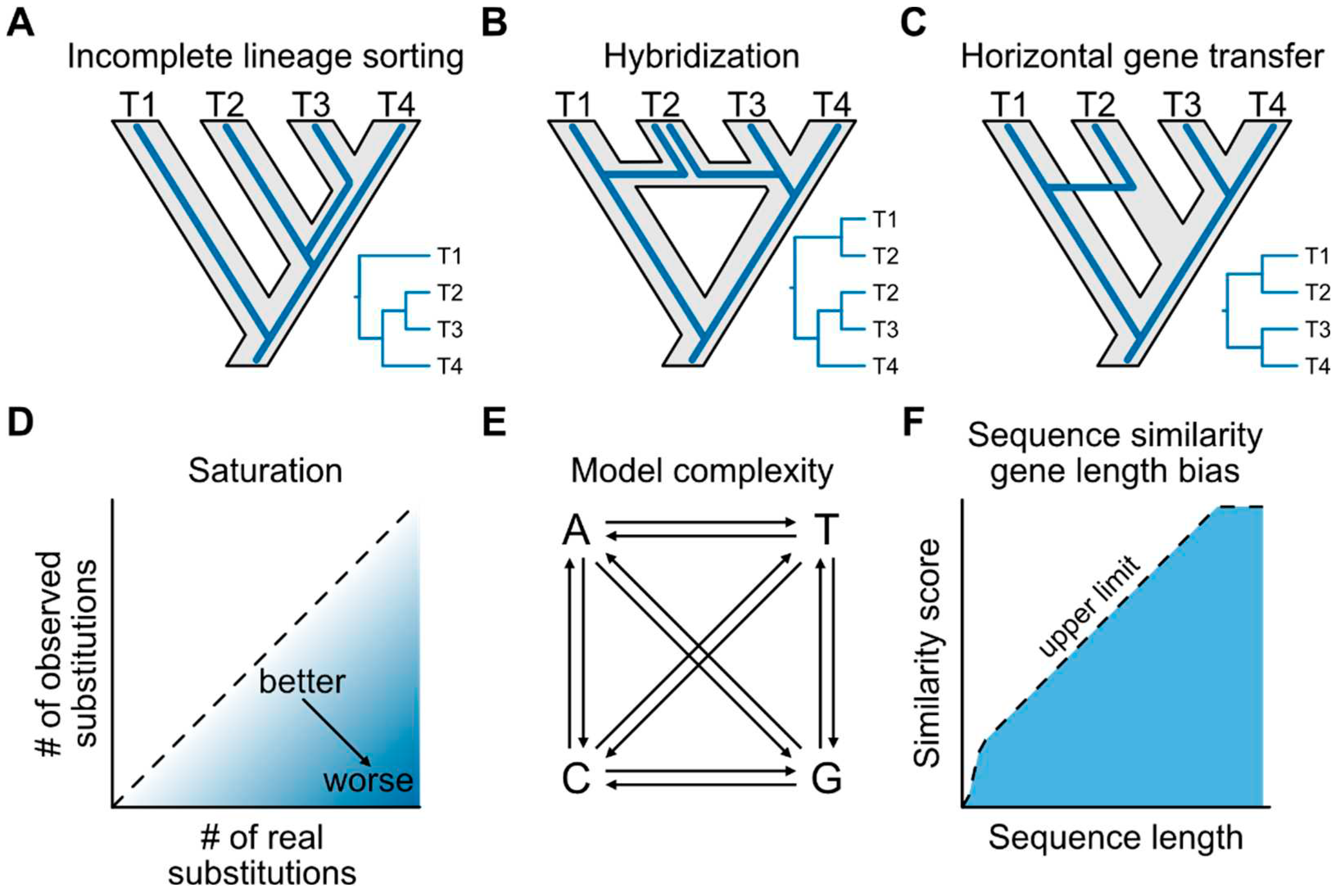

Drivers of incongruence in phylogenetic analyses

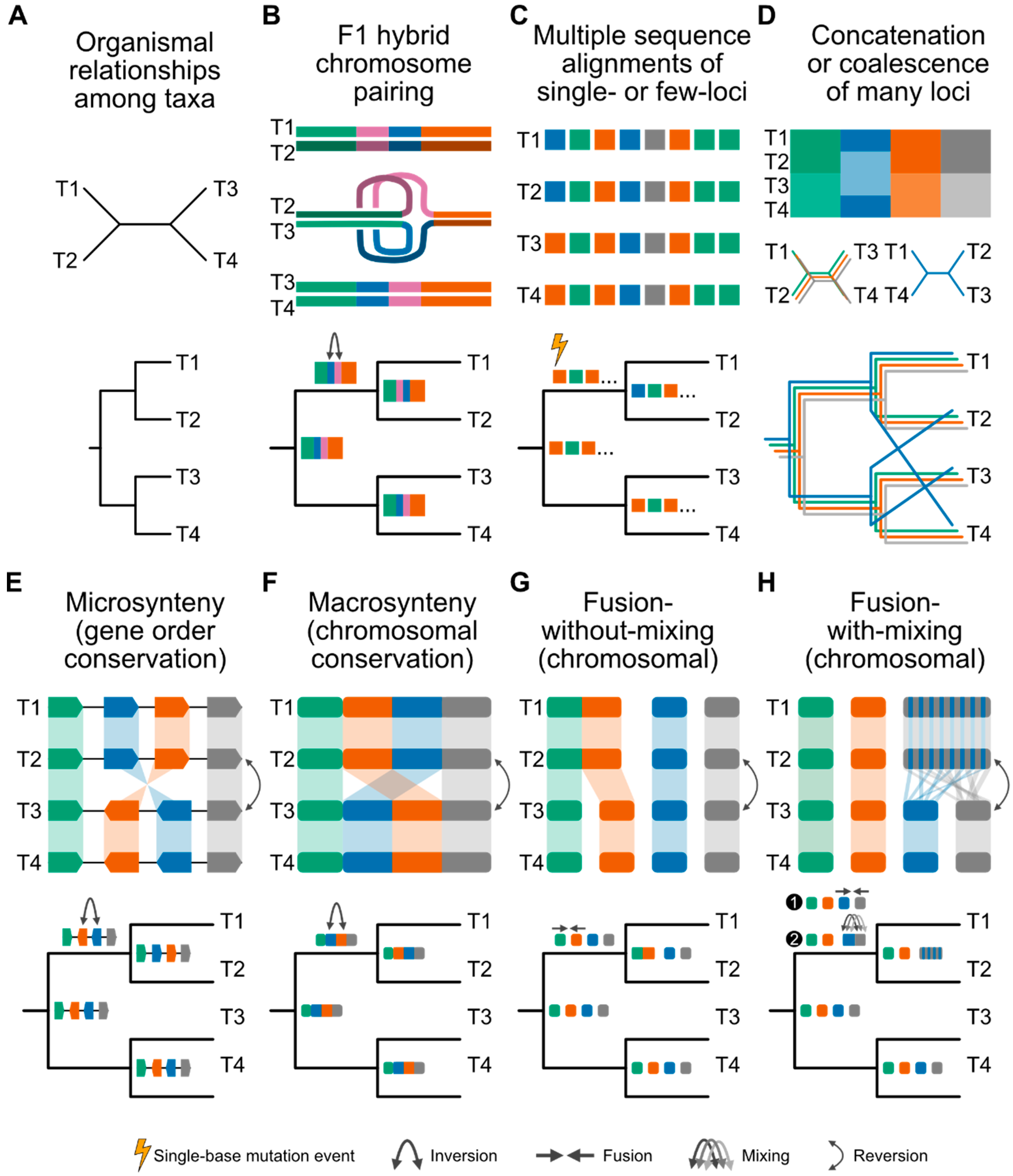

Rare genomic changes as phylogenomic markers

Synteny emerges in the phylogenomic era

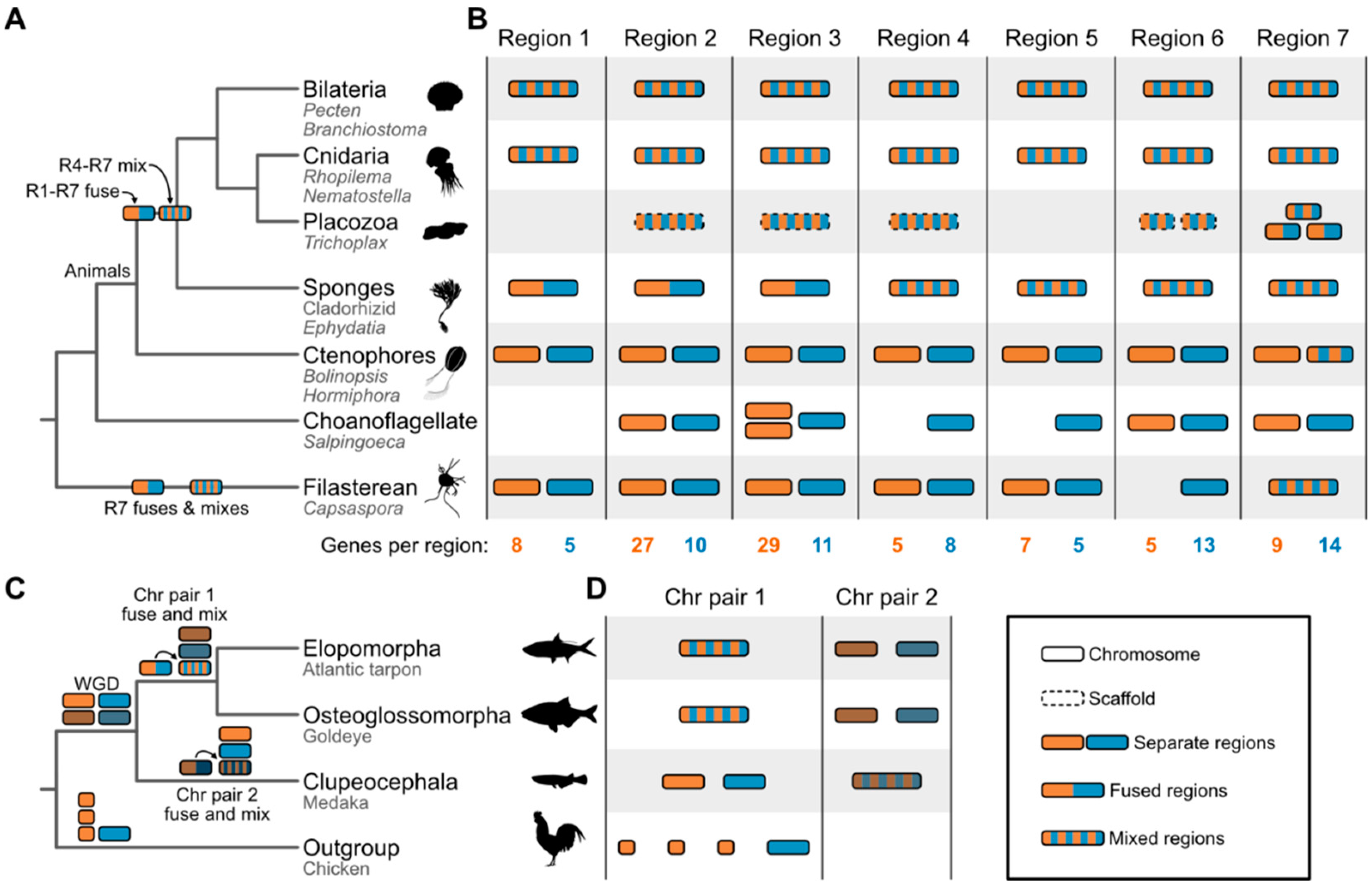

Synteny brings fresh perspectives to Tree of Life debates

Challenges and opportunities for synteny-based Tree of Life constructions

When should different types of syntenic markers be used?

What makes a good syntenic marker?

How do biological and analytical factors drive incongruence in synteny data?

How can evolutionary processes of synteny be modeled?

How do we weigh synteny evidence against other sources of data?

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Dobzhansky T, Sturtevant AH. INVERSIONS IN THE CHROMOSOMES OF DROSOPHILA PSEUDOOBSCURA. Genetics. 1938;23: 28–64. doi:10.1093/genetics/23.1.28. [CrossRef]

- Tassy P, Fischer MS. “Cladus” and clade: a taxonomic odyssey. Theory Biosci. 2021;140: 77–85. doi:10.1007/s12064-020-00326-2. [CrossRef]

- Benton MJ. Classification and phylogeny of the diapsid reptiles. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1985;84: 97–164. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1985.tb01796.x. [CrossRef]

- Hickey LJ, Wolfe JA. The Bases of Angiosperm Phylogeny: Vegetative Morphology. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1975;62: 538–589. doi:10.2307/2395267. [CrossRef]

- Fell HB. ECHINODERM EMBRYOLOGY AND THE ORIGIN OF CHORDATES. Biological Reviews. 1948;23: 81–107. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1948.tb00458.x. [CrossRef]

- Nuttall GHF, Graham-Smith GS (George S, Pigg-Strangeways TStrangeways. Blood immunity and blood relationship; a demonstration of certain blood-relationships amongst animals by means of the precipitin test for blood. Cambridge: University press; 1904. Available: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/62820.

- Reichert ET 1855-1931 (viaf)118171449, Brown AP 1864-1917 (viaf)49611474. The differentiation and specificity of corresponding proteins and other vital substances in relation to biological classification and organic evolution : the crystallography of hemoglobins. Washington; 1909. Available: http://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:001807402.

- Bridges CB. Non-Disjunction as Proof of the Chromosome Theory of Heredity (Concluded). Genetics. 1916;1: 107–163. doi:10.1093/genetics/1.2.107. [CrossRef]

- Simpson GG. The principles of classification and a classification of mammals. American Museum of Natural History; 1945.

- Sturtevant AH, Dobzhansky Th. Inversions in the Third Chromosome of Wild Races of Drosophila Pseudoobscura, and Their Use in the Study of the History of the Species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1936;22: 448–450. doi:10.1073/pnas.22.7.448. [CrossRef]

- Fitch WM, Margoliash E. Construction of Phylogenetic Trees: A method based on mutation distances as estimated from cytochrome c sequences is of general applicability. Science. 1967;155: 279–284. doi:10.1126/science.155.3760.279. [CrossRef]

- Woese CR, Fox GE. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74: 5088–5090. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088. [CrossRef]

- Fitch WM. Distinguishing Homologous from Analogous Proteins. Systematic Zoology. 1970;19: 99. doi:10.2307/2412448. [CrossRef]

- Baldauf SL, Palmer JD. Animals and fungi are each other’s closest relatives: congruent evidence from multiple proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90: 11558–11562.

- Giribet G, Edgecombe GD, Wheeler WC. Arthropod phylogeny based on eight molecular loci and morphology. Nature. 2001;413: 157–161.

- Hwang UW, Friedrich M, Tautz D, Park CJ, Kim W. Mitochondrial protein phylogeny joins myriapods with chelicerates. Nature. 2001;413: 154–157.

- Löytynoja A, Milinkovitch MC. Molecular phylogenetic analyses of the mitochondrial ADP-ATP carriers: the Plantae/Fungi/Metazoa trichotomy revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98: 10202–10207.

- Kopp A, True JR. Phylogeny of the Oriental Drosophila melanogaster species group: a multilocus reconstruction. Systematic biology. 2002;51: 786–805.

- Rokas A, King N, Finnerty J, Carroll SB. Conflicting phylogenetic signals at the base of the metazoan tree. Evolution & development. 2003;5: 346–359.

- Sanderson MJ, McMahon MM, Steel M. Terraces in Phylogenetic Tree Space. Science. 2011;333: 448–450. doi:10.1126/science.1206357. [CrossRef]

- Rokas A, Williams BL, King N, Carroll SB. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature. 2003;425: 798–804. doi:10.1038/nature02053. [CrossRef]

- Kapli P, Yang Z, Telford MJ. Phylogenetic tree building in the genomic age. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21: 428–444. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0233-0. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Li Y, Zhou X, Shen X-X, Rokas A. Incongruence in the phylogenomics era. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2023. doi:10.1038/s41576-023-00620-x. [CrossRef]

- Edwards SV. IS A NEW AND GENERAL THEORY OF MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS EMERGING? Evolution. 2009;63: 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00549.x. [CrossRef]

- Crotty SM, Minh BQ, Bean NG, Holland BR, Tuke J, Jermiin LS, et al. GHOST: Recovering Historical Signal from Heterotachously Evolved Sequence Alignments. Smith S, editor. Systematic Biology. 2019; syz051. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz051. [CrossRef]

- Williams TA, Cox CJ, Foster PG, Szöllősi GJ, Embley TM. Phylogenomics provides robust support for a two-domains tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol. 2019;4: 138–147. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-1040-x. [CrossRef]

- King N, Rokas A. Embracing Uncertainty in Reconstructing Early Animal Evolution. Current Biology. 2017;27: R1081–R1088. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.054. [CrossRef]

- Whelan NV, Kocot KM, Moroz TP, Mukherjee K, Williams P, Paulay G, et al. Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1: 1737–1746. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0331-3. [CrossRef]

- Simion P, Philippe H, Baurain D, Jager M, Richter DJ, Di Franco A, et al. A Large and Consistent Phylogenomic Dataset Supports Sponges as the Sister Group to All Other Animals. Current Biology. 2017;27: 958–967. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.031. [CrossRef]

- Wainright PO, Hinkle G, Sogin ML, Stickel SK. Monophyletic Origins of the Metazoa: an Evolutionary Link with Fungi. Science. 1993;260: 340–342. doi:10.1126/science.8469985. [CrossRef]

- Brusca RC, Brusca GJ. Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates Incorporated; 2002.

- Dunn CW, Leys SP, Haddock SHD. The hidden biology of sponges and ctenophores. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2015;30: 282–291. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2015.03.003. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen C. Early animal evolution: a morphologist’s view. R Soc open sci. 2019;6: 190638. doi:10.1098/rsos.190638. [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt P, Colgren J, Medhus A, Digel L, Naumann B, Soto-Angel JJ, et al. Syncytial nerve net in a ctenophore adds insights on the evolution of nervous systems. Science. 2023;380: 293–297. doi:10.1126/science.ade5645. [CrossRef]

- Leys SP, Hill A. The Physiology and Molecular Biology of Sponge Tissues. Advances in Marine Biology. Elsevier; 2012. pp. 1–56. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394283-8.00001-1. [CrossRef]

- Ying C, Ying W, Jing Z, Na W. Potential dietary influence on the stable isotopes and fatty acid compositions of jellyfishes in the Yellow Sea. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 2012;92: 1325–1333. doi:10.1017/S0025315412000082. [CrossRef]

- Moroz LL. Convergent evolution of neural systems in ctenophores. Anderson PAV, editor. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2015;218: 598–611. doi:10.1242/jeb.110692. [CrossRef]

- Collins AG. Evaluating multiple alternative hypotheses for the origin of Bilateria: An analysis of 18S rRNA molecular evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95: 15458–15463. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15458. [CrossRef]

- Medina M, Collins AG, Silberman JD, Sogin ML. Evaluating hypotheses of basal animal phylogeny using complete sequences of large and small subunit rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98: 9707–9712. doi:10.1073/pnas.171316998. [CrossRef]

- Podar M, Haddock SHD, Sogin ML, Harbison GR. A Molecular Phylogenetic Framework for the Phylum Ctenophora Using 18S rRNA Genes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2001;21: 218–230. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.1036. [CrossRef]

- Dunn CW, Hejnol A, Matus DQ, Pang K, Browne WE, Smith SA, et al. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452: 745–749. doi:10.1038/nature06614. [CrossRef]

- Philippe H, Derelle R, Lopez P, Pick K, Borchiellini C, Boury-Esnault N, et al. Phylogenomics Revives Traditional Views on Deep Animal Relationships. Current Biology. 2009;19: 706–712. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.052. [CrossRef]

- Shen X-X, Hittinger CT, Rokas A. Contentious relationships in phylogenomic studies can be driven by a handful of genes. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1: 0126. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0126. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Shen X-X, Evans B, Dunn CW, Rokas A. Rooting the Animal Tree of Life. Tamura K, editor. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021;38: 4322–4333. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab170. [CrossRef]

- Whelan NV, Halanych KM. Available data do not rule out Ctenophora as the sister group to all other Metazoa. Nat Commun. 2023;14: 711. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36151-6. [CrossRef]

- Patterson C. The contribution of paleontology to teleostean phylogeny. Major patterns in vertebrate evolution. 1977; 579–643.

- Hilton EJ. Comparative osteology and phylogenetic systematics of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes (Actinopterygii, Teleostei, Osteoglossomorpha). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2003;137: 1–100.

- Diogo R, Doadrio I, Vandewalle P. Teleostean phylogeny based on osteological and myological characters [Filogenia de teleosteos basada en características osteológicas y miológicas]. International Journal of Morphology. 2008;26.

- Patterson C, Rosen DE. Review of ichthyodectiform and other Mesozoic teleost fishes, and the theory and practice of classifying fossils. Bulletin of the AMNH; v. 158, article 2. 1977.

- Arratia G. Basal Teleosts and Teleostean Phylogeny: Response to C. Patterson. Copeia. 1998;1998: 1109. doi:10.2307/1447369. [CrossRef]

- Le HLV, Lecointre G, Perasso R. A 28S rRNA-Based Phylogeny of the Gnathostomes: First Steps in the Analysis of Conflict and Congruence with Morphologically Based Cladograms. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1993;2: 31–51. doi:10.1006/mpev.1993.1005. [CrossRef]

- Hurley IA, Mueller RL, Dunn KA, Schmidt EJ, Friedman M, Ho RK, et al. A new time-scale for ray-finned fish evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274: 489–498.

- Nelson JS, Schultze H-P, Wilson MV. Origin and phylogenetic interrelationships of teleosts. New York. 2010.

- Chen M-Y, Liang D, Zhang P. Selecting Question-Specific Genes to Reduce Incongruence in Phylogenomics: A Case Study of Jawed Vertebrate Backbone Phylogeny. Syst Biol. 2015;64: 1104–1120. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syv059. [CrossRef]

- Bian C, Hu Y, Ravi V, Kuznetsova IS, Shen X, Mu X, et al. The Asian arowana (Scleropages formosus) genome provides new insights into the evolution of an early lineage of teleosts. Sci Rep. 2016;6: 24501. doi:10.1038/srep24501. [CrossRef]

- Vialle RA, de Souza JES, Lopes K de P, Teixeira DG, Alves Sobrinho P de A, Ribeiro-dos-Santos AM, et al. Whole genome sequencing of the pirarucu (Arapaima gigas) supports independent emergence of major teleost clades. Genome biology and evolution. 2018;10: 2366–2379.

- Hughes LC, Ortí G, Huang Y, Sun Y, Baldwin CC, Thompson AW, et al. Comprehensive phylogeny of ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) based on transcriptomic and genomic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115: 6249–6254. doi:10.1073/pnas.1719358115. [CrossRef]

- Musilova Z, Cortesi F, Matschiner M, Davies WI, Patel JS, Stieb SM, et al. Vision using multiple distinct rod opsins in deep-sea fishes. Science. 2019;364: 588–592.

- Betancur-R R, Wiley EO, Arratia G, Acero A, Bailly N, Miya M, et al. Phylogenetic classification of bony fishes. BMC evolutionary biology. 2017;17: 1–40.

- Dornburg A, Near TJ. The emerging phylogenetic perspective on the evolution of actinopterygian fishes. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2021;52: 427–452.

- Takezaki N. Resolving the Early Divergence Pattern of Teleost Fish Using Genome-Scale Data. Venkatesh B, editor. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2021;13: evab052. doi:10.1093/gbe/evab052. [CrossRef]

- Faircloth BC, Sorenson L, Santini F, Alfaro ME. A Phylogenomic Perspective on the Radiation of Ray-Finned Fishes Based upon Targeted Sequencing of Ultraconserved Elements (UCEs). Moreau CS, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e65923. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065923. [CrossRef]

- Galtier N. A Model of Horizontal Gene Transfer and the Bacterial Phylogeny Problem. Steel M, editor. Systematic Biology. 2007;56: 633–642. doi:10.1080/10635150701546231. [CrossRef]

- Lapierre P, Lasek-Nesselquist E, Gogarten JP. The impact of HGT on phylogenomic reconstruction methods. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2014;15: 79–90. doi:10.1093/bib/bbs050. [CrossRef]

- Edelman NB, Frandsen PB, Miyagi M, Clavijo B, Davey J, Dikow RB, et al. Genomic architecture and introgression shape a butterfly radiation. Science. 2019;366: 594–599. doi:10.1126/science.aaw2090. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Lind AL, Ries LNA, dos Reis TF, Silva LP, Almeida F, et al. Pathogenic Allodiploid Hybrids of Aspergillus Fungi. Current Biology. 2020;30: 2495-2507.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.071. [CrossRef]

- Mao Y, Catacchio CR, Hillier LW, Porubsky D, Li R, Sulovari A, et al. A high-quality bonobo genome refines the analysis of hominid evolution. Nature. 2021;594: 77–81. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03519-x. [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale AP, Weaver TD, Atkinson EG, Hoal EG, Möller M, Henn BM, et al. A weakly structured stem for human origins in Africa. Nature. 2023;617: 755–763. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06055-y. [CrossRef]

- Avise JC, Robinson TJ. Hemiplasy: A New Term in the Lexicon of Phylogenetics. Kubatko L, editor. Systematic Biology. 2008;57: 503–507. doi:10.1080/10635150802164587. [CrossRef]

- Degnan JH, Rosenberg NA. Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2009;24: 332–340. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.009. [CrossRef]

- Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldón T. Beyond the Whole-Genome Duplication: Phylogenetic Evidence for an Ancient Interspecies Hybridization in the Baker’s Yeast Lineage. Hurst LD, editor. PLoS Biol. 2015;13: e1002220. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002220. [CrossRef]

- Husnik F, McCutcheon JP. Functional horizontal gene transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2018;16: 67–79.

- Irisarri I, Singh P, Koblmüller S, Torres-Dowdall J, Henning F, Franchini P, et al. Phylogenomics uncovers early hybridization and adaptive loci shaping the radiation of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes. Nat Commun. 2018;9: 3159. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05479-9. [CrossRef]

- Suvorov A, Kim BY, Wang J, Armstrong EE, Peede D, D’Agostino ERR, et al. Widespread introgression across a phylogeny of 155 Drosophila genomes. Current Biology. 2022;32: 111-123.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.052. [CrossRef]

- Arnold BJ, Huang I-T, Hanage WP. Horizontal gene transfer and adaptive evolution in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20: 206–218. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00650-4. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves P, Gonçalves C. Horizontal gene transfer in yeasts. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2022;76: 101950. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2022.101950. [CrossRef]

- Yuan L, Lu H, Li F, Nielsen J, Kerkhoven EJ. HGTphyloDetect: facilitating the identification and phylogenetic analysis of horizontal gene transfer. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2023;24: bbad035. doi:10.1093/bib/bbad035. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, Kosoy M, Dittmar K. HGTector: an automated method facilitating genome-wide discovery of putative horizontal gene transfers. BMC Genomics. 2014;15: 717. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-717. [CrossRef]

- Hahn MW, Hibbins MS. A Three-Sample Test for Introgression. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2019;36: 2878–2882. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz178. [CrossRef]

- Hibbins MS, Hahn MW. Phylogenomic approaches to detecting and characterizing introgression. Turelli M, editor. Genetics. 2022;220: iyab173. doi:10.1093/genetics/iyab173. [CrossRef]

- Morel B, Schade P, Lutteropp S, Williams TA, Szöllősi GJ, Stamatakis A. SpeciesRax: A Tool for Maximum Likelihood Species Tree Inference from Gene Family Trees under Duplication, Transfer, and Loss. Pupko T, editor. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2022;39: msab365. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab365. [CrossRef]

- Szöllősi GJ, Boussau B, Abby SS, Tannier E, Daubin V. Phylogenetic modeling of lateral gene transfer reconstructs the pattern and relative timing of speciations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109: 17513–17518. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202997109. [CrossRef]

- Stolzer M, Lai H, Xu M, Sathaye D, Vernot B, Durand D. Inferring duplications, losses, transfers and incomplete lineage sorting with nonbinary species trees. Bioinformatics. 2012;28: i409–i415. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts386. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Buida TJ, Labella AL, Li Y, Shen X-X, Rokas A. PhyKIT: a broadly applicable UNIX shell toolkit for processing and analyzing phylogenomic data. Schwartz R, editor. Bioinformatics. 2021;37: 2325–2331. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btab096. [CrossRef]

- Philippe H, Brinkmann H, Lavrov DV, Littlewood DTJ, Manuel M, Wörheide G, et al. Resolving Difficult Phylogenetic Questions: Why More Sequences Are Not Enough. Penny D, editor. PLoS Biol. 2011;9: e1000602. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000602. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez AM, Ryan JF. Six-State Amino Acid Recoding is not an Effective Strategy to Offset Compositional Heterogeneity and Saturation in Phylogenetic Analyses. Uyeda J, editor. Systematic Biology. 2021;70: 1200–1212. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syab027. [CrossRef]

- Foster PG, Schrempf D, Szöllősi GJ, Williams TA, Cox CJ, Embley TM. Recoding Amino Acids to a Reduced Alphabet may Increase or Decrease Phylogenetic Accuracy. Friedman M, editor. Systematic Biology. 2022; syac042. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syac042. [CrossRef]

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. Evolution of Protein Molecules. Mammalian Protein Metabolism. Elsevier; 1969. pp. 21–132. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4832-3211-9.50009-7. [CrossRef]

- Lartillot N, Brinkmann H, Philippe H. Suppression of long-branch attraction artefacts in the animal phylogeny using a site-heterogeneous model. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7: S4. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-S1-S4. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Durán JM, Ryan JF, Vellutini BC, Pang K, Hejnol A. Increased taxon sampling reveals thousands of hidden orthologs in flatworms. Genome Res. 2017;27: 1263–1272. doi:10.1101/gr.216226.116. [CrossRef]

- Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16: 157. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [CrossRef]

- Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20: 238. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [CrossRef]

- Chen F, Mackey AJ, Vermunt JK, Roos DS. Assessing Performance of Orthology Detection Strategies Applied to Eukaryotic Genomes. Fairhead C, editor. PLoS ONE. 2007;2: e383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000383. [CrossRef]

- Natsidis P, Kapli P, Schiffer PH, Telford MJ. Systematic errors in orthology inference and their effects on evolutionary analyses. iScience. 2021;24: 102110. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102110. [CrossRef]

- Wickett NJ, Mirarab S, Nguyen N, Warnow T, Carpenter E, Matasci N, et al. Phylotranscriptomic analysis of the origin and early diversification of land plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323926111. [CrossRef]

- Shen X-X, Zhou X, Kominek J, Kurtzman CP, Hittinger CT, Rokas A. Reconstructing the Backbone of the Saccharomycotina Yeast Phylogeny Using Genome-Scale Data. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2016;6: 3927–3939. doi:10.1534/g3.116.034744. [CrossRef]

- Shen X-X, Opulente DA, Kominek J, Zhou X, Steenwyk JL, Buh KV, et al. Tempo and Mode of Genome Evolution in the Budding Yeast Subphylum. Cell. 2018;175: 1533-1545.e20. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.023. [CrossRef]

- Cheng S, Xian W, Fu Y, Marin B, Keller J, Wu T, et al. Genomes of Subaerial Zygnematophyceae Provide Insights into Land Plant Evolution. Cell. 2019;179: 1057-1067.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.019. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Goltz DC, Buida TJ, Li Y, Shen X-X, Rokas A. OrthoSNAP: A tree splitting and pruning algorithm for retrieving single-copy orthologs from gene family trees. Hejnol A, editor. PLoS Biol. 2022;20: e3001827. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001827. [CrossRef]

- Willson J, Roddur MS, Liu B, Zaharias P, Warnow T. DISCO: Species Tree Inference using Multicopy Gene Family Tree Decomposition. Hahn M, editor. Systematic Biology. 2022;71: 610–629. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syab070. [CrossRef]

- Kocot KM, Citarella MR, Moroz LL, Halanych KM. PhyloTreePruner: A Phylogenetic Tree-Based Approach for selection of Orthologous sequences for phylogenomics. Evol Bioinform Online. 2013;9: EBO.S12813. doi:10.4137/EBO.S12813. [CrossRef]

- Tan G, Muffato M, Ledergerber C, Herrero J, Goldman N, Gil M, et al. Current Methods for Automated Filtering of Multiple Sequence Alignments Frequently Worsen Single-Gene Phylogenetic Inference. Syst Biol. 2015;64: 778–791. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syv033. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Buida TJ, Li Y, Shen X-X, Rokas A. ClipKIT: A multiple sequence alignment trimming software for accurate phylogenomic inference. Hejnol A, editor. PLoS Biol. 2020;18: e3001007. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001007. [CrossRef]

- Redmond AK, McLysaght A. Evidence for sponges as sister to all other animals from partitioned phylogenomics with mixture models and recoding. Nat Commun. 2021;12: 1783. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22074-7. [CrossRef]

- Whelan NV, Halanych KM. Who Let the CAT Out of the Bag? Accurately Dealing with Substitutional Heterogeneity in Phylogenomic Analyses. Syst Biol. 2016; syw084. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syw084. [CrossRef]

- Rokas A, Holland PWH. Rare genomic changes as a tool for phylogenetics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2000;15: 454–459. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01967-4. [CrossRef]

- Castresana J, Feldmaier-Fuchs G, Yokobori S, Satoh N, Pääbo S. The Mitochondrial Genome of the Hemichordate Balanoglossus carnosus and the Evolution of Deuterostome Mitochondria. Genetics. 1998;150: 1115–1123. doi:10.1093/genetics/150.3.1115. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh B, Ning Y, Brenner S. Late changes in spliceosomal introns define clades in vertebrate evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96: 10267–10271. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.18.10267. [CrossRef]

- Rokas A, Kathirithamby J, Holland PWH. Intron insertion as a phylogenetic character: the engrailed homeobox of Strepsiptera does not indicate affinity with Diptera. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8: 527–530. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.00149.x. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Opulente DA, Kominek J, Shen X-X, Zhou X, Labella AL, et al. Extensive loss of cell-cycle and DNA repair genes in an ancient lineage of bipolar budding yeasts. Kamoun S, editor. PLoS Biol. 2019;17: e3000255. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000255. [CrossRef]

- Krassowski T, Coughlan AY, Shen X-X, Zhou X, Kominek J, Opulente DA, et al. Evolutionary instability of CUG-Leu in the genetic code of budding yeasts. Nat Commun. 2018;9: 1887. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04374-7. [CrossRef]

- Dellaporta SL, Xu A, Sagasser S, Jakob W, Moreno MA, Buss LW, et al. Mitochondrial genome of Trichoplax adhaerens supports Placozoa as the basal lower metazoan phylum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103: 8751–8756. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602076103. [CrossRef]

- Whelan NV, Kocot KM, Moroz LL, Halanych KM. Error, signal, and the placement of Ctenophora sister to all other animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112: 5773–5778. doi:10.1073/pnas.1503453112. [CrossRef]

- Sudmant PH, Rausch T, Gardner EJ, Handsaker RE, Abyzov A, Huddleston J, et al. An integrated map of structural variation in 2,504 human genomes. Nature. 2015;526: 75–81. doi:10.1038/nature15394. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Soghigian JS, Perfect JR, Gibbons JG. Copy number variation contributes to cryptic genetic variation in outbreak lineages of Cryptococcus gattii from the North American Pacific Northwest. BMC Genomics. 2016;17: 700. doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3044-0. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y-L, Bosse M, Mullaart E, Groenen MAM, Veerkamp RF, Bouwman AC. Functional and population genetic features of copy number variations in two dairy cattle populations. BMC Genomics. 2020;21: 89. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-6496-1. [CrossRef]

- Brown KH, Dobrinski KP, Lee AS, Gokcumen O, Mills RE, Shi X, et al. Extensive genetic diversity and substructuring among zebrafish strains revealed through copy number variant analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109: 529–534. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112163109. [CrossRef]

- Fortna A, Kim Y, MacLaren E, Marshall K, Hahn G, Meltesen L, et al. Lineage-Specific Gene Duplication and Loss in Human and Great Ape Evolution. Chris Tyler-Smith, editor. PLoS Biol. 2004;2: e207. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020207. [CrossRef]

- Mühlhausen S, Schmitt HD, Pan K-T, Plessmann U, Urlaub H, Hurst LD, et al. Endogenous Stochastic Decoding of the CUG Codon by Competing Ser- and Leu-tRNAs in Ascoidea asiatica. Current Biology. 2018;28: 2046-2057.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.085. [CrossRef]

- Haas BJ, Delcher AL, Wortman JR, Salzberg SL. DAGchainer: a tool for mining segmental genome duplications and synteny. Bioinformatics. 2004;20: 3643–3646.

- Proost S, Fostier J, De Witte D, Dhoedt B, Demeester P, Van de Peer Y, et al. i-ADHoRe 3.0—fast and sensitive detection of genomic homology in extremely large data sets. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40: e11–e11.

- Wang Y, Tang H, Debarry JD, Tan X, Li J, Wang X, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40: e49–e49.

- Drillon G, Carbone A, Fischer G. SynChro: a fast and easy tool to reconstruct and visualize synteny blocks along eukaryotic chromosomes. PloS one. 2014;9: e92621.

- Hane JK, Rouxel T, Howlett BJ, Kema GH, Goodwin SB, Oliver RP. A novel mode of chromosomal evolution peculiar to filamentous Ascomycete fungi. Genome Biol. 2011;12: R45. doi:10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-r45. [CrossRef]

- Robberecht C, Voet T, Esteki MZ, Nowakowska BA, Vermeesch JR. Nonallelic homologous recombination between retrotransposable elements is a driver of de novo unbalanced translocations. Genome Res. 2013;23: 411–418. doi:10.1101/gr.145631.112. [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Bennetzen JL. Recombination, rearrangement, reshuffling, and divergence in a centromeric region of rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103: 383–388. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509810102. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Lacaria M, Zhang F, Withers M, Hastings PJ, Lupski JR. Frequency of Nonallelic Homologous Recombination Is Correlated with Length of Homology: Evidence that Ectopic Synapsis Precedes Ectopic Crossing-Over. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;89: 580–588. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.009. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson S, Jones A, Murray K, Schwessinger B, Borevitz JO. Interspecies genome divergence is predominantly due to frequent small scale rearrangements in Eucalyptus. Molecular Ecology. 2023;32: 1271–1287. doi:10.1111/mec.16608. [CrossRef]

- Zhao T, Schranz ME. Network-based microsynteny analysis identifies major differences and genomic outliers in mammalian and angiosperm genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116: 2165–2174. doi:10.1073/pnas.1801757116. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Liu H, Steenwyk JL, LaBella AL, Harrison M-C, Groenewald M, et al. Contrasting modes of macro and microsynteny evolution in a eukaryotic subphylum. Current Biology. 2022; S0960982222016700. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.10.025. [CrossRef]

- Delsuc F, Brinkmann H, Philippe H. Phylogenomics and the reconstruction of the tree of life. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6: 361–375. doi:10.1038/nrg1603. [CrossRef]

- Drillon G, Champeimont R, Oteri F, Fischer G, Carbone A. Phylogenetic Reconstruction Based on Synteny Block and Gene Adjacencies. Battistuzzi FU, editor. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2020;37: 2747–2762. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa114. [CrossRef]

- Zhao T, Zwaenepoel A, Xue J-Y, Kao S-M, Li Z, Schranz ME, et al. Whole-genome microsynteny-based phylogeny of angiosperms. Nat Commun. 2021;12: 3498. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23665-0. [CrossRef]

- Schultz DT, Haddock SHD, Bredeson JV, Green RE, Simakov O, Rokhsar DS. Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals. Nature. 2023 [cited 21 May 2023]. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05936-6. [CrossRef]

- Fairclough SR, Chen Z, Kramer E, Zeng Q, Young S, Robertson HM, et al. Premetazoan genome evolution and the regulation of cell differentiation in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Genome Biol. 2013;14: R15. doi:10.1186/gb-2013-14-2-r15. [CrossRef]

- King N, Westbrook MJ, Young SL, Kuo A, Abedin M, Chapman J, et al. The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans. Nature. 2008;451: 783–788. doi:10.1038/nature06617. [CrossRef]

- Richter DJ, Fozouni P, Eisen MB, King N. Gene family innovation, conservation and loss on the animal stem lineage. eLife. 2018;7: e34226. doi:10.7554/eLife.34226. [CrossRef]

- Sperling EA, Pisani D, Peterson KJ. Poriferan paraphyly and its implications for Precambrian palaeobiology. SP. 2007;286: 355–368. doi:10.1144/SP286.25. [CrossRef]

- Borchiellini C, Manuel M, Alivon E, Boury-Esnault N, Vacelet J, Le Parco Y. Sponge paraphyly and the origin of Metazoa: Sponge paraphyly. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2001;14: 171–179. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00244.x. [CrossRef]

- Kenny NJ, Francis WR, Rivera-Vicéns RE, Juravel K, De Mendoza A, Díez-Vives C, et al. Tracing animal genomic evolution with the chromosomal-level assembly of the freshwater sponge Ephydatia muelleri. Nat Commun. 2020;11: 3676. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17397-w. [CrossRef]

- Parey E, Louis A, Montfort J, Bouchez O, Roques C, Iampietro C, et al. Genome structures resolve the early diversification of teleost fishes. Science. 2023;379: 572–575. doi:10.1126/science.abq4257. [CrossRef]

- Pollock DD, Zwickl DJ, McGuire JA, Hillis DM. Increased Taxon Sampling Is Advantageous for Phylogenetic Inference. Crandall K, editor. Systematic Biology. 2002;51: 664–671. doi:10.1080/10635150290102357. [CrossRef]

- Aberer AJ, Krompass D, Stamatakis A. Pruning Rogue Taxa Improves Phylogenetic Accuracy: An Efficient Algorithm and Webservice. Systematic Biology. 2013;62: 162–166. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys078. [CrossRef]

- Riley R, Haridas S, Wolfe KH, Lopes MR, Hittinger CT, Göker M, et al. Comparative genomics of biotechnologically important yeasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113: 9882–9887. doi:10.1073/pnas.1603941113. [CrossRef]

- Scannell DR, Byrne KP, Gordon JL, Wong S, Wolfe KH. Multiple rounds of speciation associated with reciprocal gene loss in polyploid yeasts. Nature. 2006;440: 341–345. doi:10.1038/nature04562. [CrossRef]

- Shen X-X, Salichos L, Rokas A. A Genome-Scale Investigation of How Sequence, Function, and Tree-Based Gene Properties Influence Phylogenetic Inference. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8: 2565–2580. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw179. [CrossRef]

- Mongiardino Koch N. Phylogenomic Subsampling and the Search for Phylogenetically Reliable Loci. Satta Y, editor. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021;38: 4025–4038. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab151. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk JL, Shen X-X, Lind AL, Goldman GH, Rokas A. A Robust Phylogenomic Time Tree for Biotechnologically and Medically Important Fungi in the Genera Aspergillus and Penicillium. Boyle JP, editor. mBio. 2019;10: e00925-19. doi:10.1128/mBio.00925-19. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Zhang J, Rheindt FE, Lei F, Qu Y, Wang Y, et al. Genomic evidence reveals a radiation of placental mammals uninterrupted by the KPg boundary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114. doi:10.1073/pnas.1616744114. [CrossRef]

- Smith SA, Brown JW, Walker JF. So many genes, so little time: A practical approach to divergence-time estimation in the genomic era. Escriva H, editor. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0197433. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197433. [CrossRef]

- Steenwyk J, Rokas A. Extensive Copy Number Variation in Fermentation-Related Genes Among Saccharomyces cerevisiae Wine Strains. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2017;7: 1475–1485. doi:10.1534/g3.117.040105. [CrossRef]

- Saint-Leandre B, Levine MT. The Telomere Paradox: Stable Genome Preservation with Rapidly Evolving Proteins. Trends in Genetics. 2020;36: 232–242. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2020.01.007. [CrossRef]

- Baird DM. Telomeres and genomic evolution. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2018;373: 20160437. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0437. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22: 160–174. doi:10.1007/BF02101694. [CrossRef]

- Tavaré S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect Math Life Sci (Am Math Soc). 1986;17: 57–86.

- Yang Z, Nielsen R, Hasegawa M. Models of amino acid substitution and applications to mitochondrial protein evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1998;15: 1600–1611. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025888. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).