Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Key highlights of TBI |

|

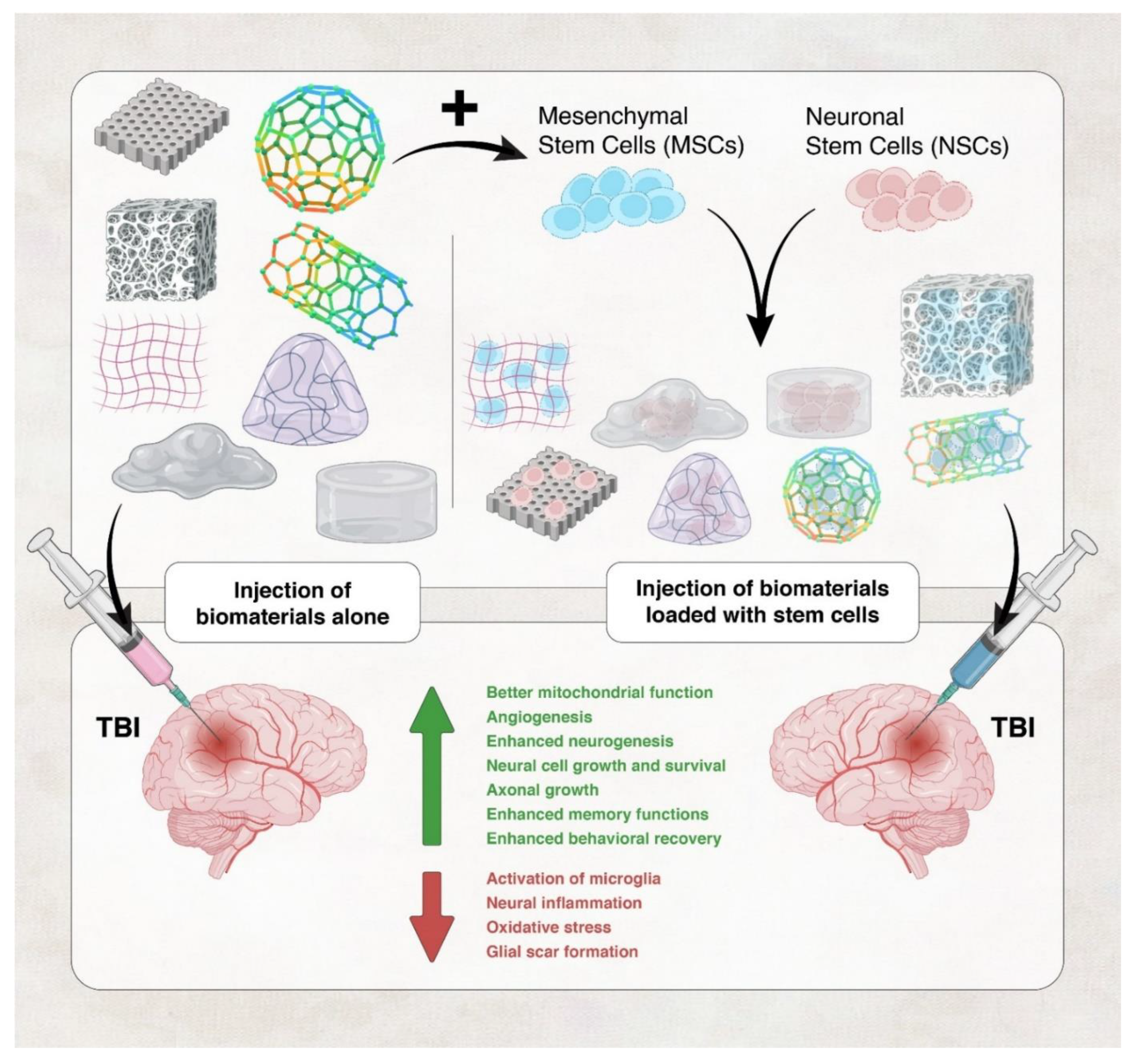

2. Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials in TBI

2.1. Mechanisms of repair by tissue engineering and biomaterials in TBI

2.2. Biomaterials used in TBI therapy

| Aspect | Synthetic | Natural |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Artificially synthesized | Biological sources |

| Biodegradability | Variable, controllable | Naturally degradable |

| Immunogenicity | Generally low | Potential immune response |

| Mechanical Properties | Customizable for specific needs | Variable |

| Biocompatibility | Reduced, can be optimized | Good biocompatibility |

| Growth Factors | Controlled release | Potential endogenous release |

| Examples | poly-anhydrides, and poly-orthoesters. | Collagen, chitosan, hyaluronic acid |

2.3. Materials used to make biomaterials for TBI therapy

2.4. Complications with the Use of Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering

| Study | Biomaterial | Species | Outcome | Reference |

| Liu et al. (2023) | Collagen/chitosan/BMExos scaffold | Rat |

|

[174] |

| Li et al. (2021) | Gelatin hydrogel | In vitro & mice |

|

[61] |

| Tang et al. (2020) | aPLGA-LysoGM1 scaffold | In vitro & rat model |

|

[175] |

| Zheng et al. (2020) | gelatin methacrylate hydrogel with polydopamine nanoparticles and hAMSCS | Rat |

|

[54] |

| Mahumane et al. (2020) | N-acetylcysteine (NAC)-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) electrospun nanofiber | In vitro & ex vivo (Rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) and human glioblastoma multiform (A172) cell lines) |

|

[176] |

| Zhou et al. (2018) | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) scaffold | In vitro & in vivo Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and neurons |

|

[177] |

| Álvarez et al. (2014) | poly-l/dl lactic acid (PLA70/30) nanofibers | Mice |

|

[178] |

| Sulejczak et al. (2014) | Electrospun nanofiber/ L-lactide-caprolactone copolymer nanofiber net | Rat |

|

[162] |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | Vepoloxamer | Rats |

|

[179] |

| Macks et al. (2022) | poly(ethylene) glycol-bis-(acryloyloxy acetate) (PEG-bis-AA) with dexamethasone (DX)-conjugated hyaluronic acid (HA-DXM) | Rats |

|

[180] |

| Latchoumane et al. (2021) | Engineered Chondroitin sulfate (eCS) | Rats |

|

[78] |

| Liu et al. (2022) | secretome/collagen/heparan sulfate scaffold | Rats |

|

[181] |

| Sahab Negah et al. (2019) | Self- assembling peptide hMgSCs + R-GSIK | Rats |

|

[149] |

| Liu et al. (2023) | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BME) + hyaluronan-collagen hydrogel (DHC-BME) | Rats |

|

[182] |

| Tanikawa et al. (2023) | Electrically charged hydrogels (C1A1) + VEGF | Mice |

|

[183] |

| Hu et al. (2023) | Self-healing hydrogel (HA-PBA/Gel-Dopa) | Mice |

|

[184] |

| Moisenovich et al. (2019) | Silk fibroin scaffold | Rats |

|

[185] |

| Chen et al (2022) | hydrogen sulfide(H2S)-releasing silk fibroin (SF) hydrogel (H2S@SF) | Mice |

|

[186] |

| Jiang et al (2021) | Collagen/Silk Fibroin (SF) scaffold | Canine |

|

[187] |

| Qian et al (2021) | TM/PC hydrogel (Tri-glycerol monostearate, propylene sulfide and curcumin) |

Mice |

|

[188] |

| Zhang et al. (2022) | HT/HGA hydrogel (hyaluronic acid-tyramine + antioxidant gallic acid-grafted hyaluronic acid) | Mice |

|

[64] |

| Chen et al (2023) | gelatin methacrylate and sodium alginate hydrogel (GelMA/Alg) | Rat |

|

[189] |

| Ma et al (2020) | self-assembling peptide-based hydrogel | Rat |

|

[190] |

| Biomaterial | Characteristic | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

| Natural Hydrogels | cross-linked macromolecular networks | - no mechanical/spatial restrictions compared to synthetic polymer scaffolds - mesh size and porosity of hydrogels can be modified -Biocompatible -Injectable -Porous |

-heterogeneity between batches -May carry natural pathogen -difficulty in precise modification of the material |

[54,64] |

| Synthetic hydrogels | Can be modified according to need | -Biologically inert -Chemically stable -Easier to control important perimeters |

- Premade, require invasive implantation surgery -Cause more inflammatory response than natural hydrogels |

[191,192,193] |

| Self-assembling peptides SAPNS | composed of repeating units of amino acids and characterized by the formation of double-β- sheet structures | -high porosity -increased cell signaling from bioactive peptides that are presented in high density at the damaged site -Highly biocompatible -Allow minimally invasive treatments |

-Lack of understanding on their degradability -Lack of data on long-term electroactivity of the scaffold |

[140,194,195] |

| Electrospun nanofibers | A nonwoven mat of micro- and nanofibers is created when fluid filament is stretched in a powerful electric field. | - Aligned nanofibers can resemble the topographical characteristics of the extracellular matrix in the brain. - Due to large surface-to-volume ratio electrospun fibers improve cell adhesion, mass transfer characteristics, and drug loading. |

-pH difference, local enzymes may degrade the fibers | [196,197] |

3. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dewan, M.C., et al., Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurosurgery, 2018. 130(4): p. 1080-1097. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W., et al., Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in Europe. Acta neurochirurgica, 2015. 157(10): p. 1683-1696. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S. and D. Woessner, Sports-related traumatic brain injury. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 2015. 42(2): p. 243-248.

- Wojcik, B.E., et al., Traumatic brain injury hospitalizations of US army soldiers deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. American journal of preventive medicine, 2010. 38(1): p. S108-S116. [CrossRef]

- Theadom, A., et al., Incidence of sports-related traumatic brain injury of all severities: a systematic review. 2020. 54(2): p. 192-199. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.E., J.G. Berry, and L.M. Jamieson, Head and traumatic brain injuries among Australian youth and young adults, July 2000–June 2006. Brain injury, 2012. 26(7-8): p. 996-1004. [CrossRef]

- Peplow, P.V., B. Martinez, and T.A.J.N.D.B.T.T.R.t.C.P. Gennarelli, Prevalence, needs, strategies, and risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases. 2022: p. 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Norup, A., et al., Socioeconomic consequences of traumatic brain injury: a danish nationwide register-based study. Journal of neurotrauma, 2020. 37(24): p. 2694-2702. [CrossRef]

- Howlett, J.R., L.D. Nelson, and M.B. Stein, Mental Health Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. Biol Psychiatry, 2022. 91(5): p. 413-420. [CrossRef]

- DeKosky, S.T., et al., Acute and chronic traumatic encephalopathies: pathogenesis and biomarkers. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2013. 9(4): p. 192-200. [CrossRef]

- Crane, P.K., et al., Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic Findings. JAMA Neurol, 2016. 73(9): p. 1062-9. [CrossRef]

- Vespa, P.M., Hormonal dysfunction in neurocritical patients. Current opinion in critical care, 2013. 19(2): p. 107-112. [CrossRef]

- Foreman, B., et al., Seizures and Cognitive Outcome After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Post Hoc Analysis. Neurocrit Care, 2022. 36(1): p. 130-138. [CrossRef]

- Monsour, M., D. Ebedes, and C.V. Borlongan, A review of the pathology and treatment of TBI and PTSD. Exp Neurol, 2022. 351: p. 114009. [CrossRef]

- Alouani, A.T. and T. Elfouly, Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Detection: Past, Present, and Future. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Brett, B.L., et al., Traumatic Brain Injury and Risk of Neurodegenerative Disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 2022. 91(5): p. 498-507. [CrossRef]

- Haidar, M.A., et al., Mitoquinone Helps Combat the Neurological, Cognitive, and Molecular Consequences of Open Head Traumatic Brain Injury at Chronic Time Point. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(2): p. 250. [CrossRef]

- Control, C.f.D. and Prevention, national center for injury prevention and control: report to congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: steps to prevent a serious public health problem. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003.

- Dikmen, S., et al., Rates of symptom reporting following traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2010. 16(3): p. 401-11. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, K.J., Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am, 2017. 28(2): p. 215-225. [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C. and D.H. Daneshvar, The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handbook of clinical neurology, 2015. 127: p. 45-66. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P. and S. Sharma, Recent advances in pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Current neuropharmacology, 2018. 16(8): p. 1224-1238. [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.-C., et al., A potent inhibition of oxidative stress induced gene expression in neural cells by sustained ferulic acid release from chitosan based hydrogel. 2015. 49: p. 691-699. [CrossRef]

- Stirling, D.P., et al., Axoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release causes secondary degeneration of spinal axons. Annals of neurology, 2014. 75(2): p. 220-229. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J., et al., Calcium signaling is implicated in the diffuse axonal injury of brain stem. 2015. 8(5): p. 4388.

- Arciniegas, D.B. and J.M. Silver, Pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic cognitive impairments. Behavioural neurology, 2006. 17(1): p. 25-42. [CrossRef]

- Weil, Z.M., K.R. Gaier, and K. Karelina, Injury timing alters metabolic, inflammatory and functional outcomes following repeated mild traumatic brain injury. Neurobiology of disease, 2014. 70: p. 108-116. [CrossRef]

- Fehily, B. and M. Fitzgerald, Repeated mild traumatic brain injury: potential mechanisms of damage. Cell transplantation, 2017. 26(7): p. 1131-1155.

- Mustafa, A.G., et al., Pharmacological inhibition of lipid peroxidation attenuates calpain-mediated cytoskeletal degradation after traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurochemistry, 2011. 117(3): p. 579-588. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Muneer, P., N. Chandra, and J. Haorah, Interactions of oxidative stress and neurovascular inflammation in the pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury. Molecular neurobiology, 2015. 51(3): p. 966-979. [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.L., Blood–brain barrier and traumatic brain injury. Journal of neuroscience research, 2014. 92(2): p. 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Shlosberg, D., et al., Blood–brain barrier breakdown as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2010. 6(7): p. 393-403. [CrossRef]

- Llorens-Bobadilla, E., et al., A latent lineage potential in resident neural stem cells enables spinal cord repair. 2020. 370(6512): p. eabb8795. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., et al., Soft conducting polymer hydrogels cross-linked and doped by tannic acid for spinal cord injury repair. 2018. 12(11): p. 10957-10967. [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.Y. and A.Y.W. Lee, Traumatic Brain Injuries: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front Cell Neurosci, 2019. 13: p. 528. [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.J., et al., Enhanced astrocytic d-serine underlies synaptic damage after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Invest, 2017. 127(8): p. 3114-3125. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. and R.A. Swanson, Astrocytes and brain injury. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 2003. 23(2): p. 137-149.

- Al-Haj, N., et al., Phytochemicals as Micronutrients: What Is their Therapeutic Promise in the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury?, in Role of Micronutrients in Brain Health. 2022, Springer. p. 245-276.

- Xiong, B., et al., Strategies for structural modification of small molecules to improve blood–brain barrier penetration: A recent perspective. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2021. 64(18): p. 13152-13173. [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.A., Nanotechnology approaches for the regeneration and neuroprotection of the central nervous system. Surgical Neurology, 2005. 63(4): p. 301-306. [CrossRef]

- Han, L. and C. Jiang, Evolution of blood-brain barrier in brain diseases and related systemic nanoscale brain-targeting drug delivery strategies. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2021. 11(8): p. 2306-2325. [CrossRef]

- Cash, A. and M.H. Theus, Mechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(9). [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, P.M., et al., Operation brain trauma therapy: 2016 update. Military medicine, 2018. 183(suppl_1): p. 303-312.

- Francis, N.L., et al., Self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffolds for 3-D reprogramming and transplantation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons. ACS biomaterials science & engineering, 2016. 2(6): p. 1030-1038. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, F., et al., Stabilization, rolling, and addition of other extracellular matrix proteins to collagen hydrogels improve regeneration in chitosan guides for long peripheral nerve gaps in rats. Neurosurgery, 2017. 80(3): p. 465-474. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., et al., PTMAc-PEG-PTMAc hydrogel modified by RGDC and hyaluronic acid promotes neural stem cells' survival and differentiation in vitro. RSC advances, 2017. 7(65): p. 41098-41104. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., et al., Enhancement of neurite adhesion, alignment and elongation on conductive polypyrrole-poly (lactide acid) fibers with cell-derived extracellular matrix. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2017. 149: p. 217-225.

- Xue, C., et al., Electrospun silk fibroin-based neural scaffold for bridging a long sciatic nerve gap in dogs. Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, 2018. 12(2): p. e1143-e1153. [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M., Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2012. 32(11): p. 1959-72. [CrossRef]

- Skolnick, B.E., et al., A Clinical Trial of Progesterone for Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. New England Journal of Medicine, 2014. 371(26): p. 2467-2476. [CrossRef]

- Ikada, Y., Challenges in tissue engineering. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2006. 3(10): p. 589-601.

- Babensee, J.E., L.V. McIntire, and A.G. Mikos, Growth factor delivery for tissue engineering. Pharmaceutical research, 2000. 17(5): p. 497-504. [CrossRef]

- Yao, M., et al., A dual-enzymatically cross-linked injectable gelatin hydrogel loaded with BMSC improves neurological function recovery of traumatic brain injury in rats. 2019. 7(10): p. 4088-4098. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., et al., Neuro-regenerative imidazole-functionalized GelMA hydrogel loaded with hAMSC and SDF-1α promote stem cell differentiation and repair focal brain injury. Bioact Mater, 2021. 6(3): p. 627-637. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., Semi-interpenetrating polymer network of hyaluronan and chitosan self-healing hydrogels for central nervous system repair. 2020. 12(36): p. 40108-40120. [CrossRef]

- Yao, M., et al., Chitosan-based thermosensitive composite hydrogel enhances the therapeutic efficacy of human umbilical cord MSC in TBI rat model. 2019. 14: p. 100192. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.U., et al., Hydrogel-mediated local delivery of dexamethasone reduces neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Biomed Mater, 2021. 16(3). [CrossRef]

- Kuan, C.-Y., et al., The preparation of oxidized methylcellulose crosslinked by adipic acid dihydrazide loaded with vitamin C for traumatic brain injury. 2019. 7(29): p. 4499-4508. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., et al., Synergistic effects of dual-presenting VEGF-and BDNF-mimetic peptide epitopes from self-assembling peptide hydrogels on peripheral nerve regeneration. 2019. 11(42): p. 19943-19958. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.Z., et al., Neuroinflammation Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Take It Seriously or Not. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 855701. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Dual-enzymatically cross-linked gelatin hydrogel promotes neural differentiation and neurotrophin secretion of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of moderate traumatic brain injury. Int J Biol Macromol, 2021. 187: p. 200-213. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., L. He, and W. Wu, Self-assembling peptide nanofibrous hydrogel as a promising strategy in nerve repair after traumatic injury in the nervous system. Neural Regen Res, 2016. 11(5): p. 717-8. [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, F.J. and W. Cerpa, Regulation of Phosphorylated State of NMDA Receptor by STEP(61) Phosphatase after Mild-Traumatic Brain Injury: Role of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel), 2021. 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., et al., In situ forming and biocompatible hyaluronic acid hydrogel with reactive oxygen species-scavenging activity to improve traumatic brain injury repair by suppressing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Mater Today Bio, 2022. 15: p. 100278. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.X., et al., The use of bioactive matrices in regenerative therapies for traumatic brain injury. 2020. 102: p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Zhen Xu, S.L., Min Liang, Haoyi Yang, Chunqi Chang, Biomaterials Based Growth Factor Delivery for Brain Regeneration After Injury. Smart Materials in Medicine, 2022. 3: p. 352-360. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N., A. Adak, and S.J.S.M. Ghosh, Recent trends in the development of peptide and protein-based hydrogel therapeutics for the healing of CNS injury. 2020. 16(44): p. 10046-10064. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., et al., Sodium alginate/collagen/stromal cell-derived factor-1 neural scaffold loaded with BMSCs promotes neurological function recovery after traumatic brain injury. Acta Biomater, 2021. 131: p. 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W., et al., Transplantation of RADA16-BDNF peptide scaffold with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells forced with CXCR4 and activated astrocytes for repair of traumatic brain injury. Acta Biomater, 2016. 45: p. 247-261. [CrossRef]

- Tabet, M., et al., Evaluation of Evidence: Stem Cells as a Treatment Option for Traumatic Brain Injury, in eLS. p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-Y., et al., Neural stem cells encapsulated in a functionalized self-assembling peptide hydrogel for brain tissue engineering. Biomaterials, 2013. 34(8): p. 2005-2016. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., et al., A conductive supramolecular hydrogel creates ideal endogenous niches to promote spinal cord injury repair. Bioact Mater, 2022. 15: p. 103-119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Hydrogel oxygen reservoirs increase functional integration of neural stem cell grafts by meeting metabolic demands. 2023. 14(1): p. 457. [CrossRef]

- Keimpema, E., et al., Early transient presence of implanted bone marrow stem cells reduces lesion size after cerebral ischaemia in adult rats. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 2009. 35(1): p. 89-102. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, E.D., et al., Strands of embryonic mesencephalic tissue show greater dopamine neuron survival and better behavioral improvement than cell suspensions after transplantation in parkinsonian rats. Brain Res, 1998. 806(1): p. 60-8. [CrossRef]

- Sautter, J., et al., Implants of polymer-encapsulated genetically modified cells releasing glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor improve survival, growth, and function of fetal dopaminergic grafts. Experimental neurology, 1998. 149(1): p. 230-236. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F., et al., Collagen-chitosan scaffold impregnated with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of traumatic brain injury. 2019. 14(10): p. 1780. [CrossRef]

- Latchoumane, C.V., et al., Engineered glycomaterial implants orchestrate large-scale functional repair of brain tissue chronically after severe traumatic brain injury. Sci Adv, 2021. 7(10). [CrossRef]

- Donaghue, I.E., et al., Cell and Biomolecule Delivery for Tissue Repair and Regeneration in the Central Nervous System. Journal of Controlled Release, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-M. and X.J.P.i.p.s. Liu, Advancing biomaterials of human origin for tissue engineering. 2016. 53: p. 86-168.

- Davim, J.P., Biomedical composites: materials, manufacturing and engineering. Vol. 2. 2013: Walter de Gruyter.

- Feng, C., et al., 3D Printing of Lotus Root-Like Biomimetic Materials for Cell Delivery and Tissue Regeneration. Adv Sci (Weinh), 2017. 4(12): p. 1700401. [CrossRef]

- Kyburz, K.A. and K.S. Anseth, Synthetic mimics of the extracellular matrix: how simple is complex enough? Ann Biomed Eng, 2015. 43(3): p. 489-500. [CrossRef]

- Ventre, M. and P.A. Netti, Engineering Cell Instructive Materials To Control Cell Fate and Functions through Material Cues and Surface Patterning. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2016. 8(24): p. 14896-908. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.-X., et al., Biomaterials for endogenous regenerative medicine: coaxing stem cell homing and beyond. 2018. 11: p. 144-165. [CrossRef]

- Yu-Shuan Chen, H.-J.H., Tzyy-Wen Chiou, The Role of Biomaterials in Implantation for Central Nervous System Injury. Cell Transplant, 2018. 27(3): p. 407-422. [CrossRef]

- Pettikiriarachchi, J.T.S., et al., Biomaterials for Brain Tissue Engineering. Australian Journal of Chemistry, 2010. 63(8): p. 1143-1154. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., et al., Structurally dynamic hydrogels for biomedical applications: pursuing a fine balance between macroscopic stability and microscopic dynamics. 2021. 121(18): p. 11149-11193. [CrossRef]

- He, J., et al., Scaffolds for central nervous system tissue engineering. 2012. 6: p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., et al., In vivo conversion of astrocytes to neurons in the injured adult spinal cord. 2014. 5(1): p. 3338. [CrossRef]

- Tamariz, E. and A.J.F.i.n. Varela-Echavarría, The discovery of the growth cone and its influence on the study of axon guidance. 2015. 9: p. 51.

- Musah, S., et al., Glycosaminoglycan-binding hydrogels enable mechanical control of human pluripotent stem cell self-renewal. ACS Nano, 2012. 6(11): p. 10168-77. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al., Applications and Mechanisms of Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels in Traumatic Brain Injury. Gels, 2022. 8(8). [CrossRef]

- Jurga, M., et al., The performance of laminin-containing cryogel scaffolds in neural tissue regeneration. 2011. 32(13): p. 3423-3434. [CrossRef]

- Cholas, R.H., H.-P. Hsu, and M.J.B. Spector, The reparative response to cross-linked collagen-based scaffolds in a rat spinal cord gap model. 2012. 33(7): p. 2050-2059. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ramos, C., et al., Neural tissue regeneration in experimental brain injury model with channeled scaffolds of acrylate copolymers. 2015. 598: p. 96-101. [CrossRef]

- Kretlow, J.D., L. Klouda, and A.G.J.A.d.d.r. Mikos, Injectable matrices and scaffolds for drug delivery in tissue engineering. 2007. 59(4-5): p. 263-273. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. and D.J.J.N.R.M. Mooney, Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. 2016. 1(12): p. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A. and A.S. Hoffman, Hydrogels, in Biomaterials science. 2020, Elsevier. p. 153-166.

- Gradinaru, V., et al., Hydrogel-tissue chemistry: principles and applications. 2018. 47: p. 355-376. [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbiny, I.M., M.H.J.G.C.S. Yacoub, and Practice, Hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering: Progress and challenges. 2013. 2013(3): p. 38. [CrossRef]

- Martin, N. and G.J.J.o.t.m.b.o.b.m. Youssef, Dynamic properties of hydrogels and fiber-reinforced hydrogels. 2018. 85: p. 194-200.

- Che, L., et al., A 3D printable and bioactive hydrogel scaffold to treat traumatic brain injury. 2019. 29(39): p. 1904450. [CrossRef]

- Saracino, G.A., et al., Nanomaterials design and tests for neural tissue engineering. Chem Soc Rev, 2013. 42(1): p. 225-62. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.N. and C. Birkinshaw, Hyaluronic acid based scaffolds for tissue engineering--a review. Carbohydr Polym, 2013. 92(2): p. 1262-79. [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S., et al., Bioactive polymeric scaffolds for tissue engineering. Bioact Mater, 2016. 1(2): p. 93-108. [CrossRef]

- Patenaude, M., N.M. Smeets, and T. Hoare, Designing injectable, covalently cross-linked hydrogels for biomedical applications. Macromol Rapid Commun, 2014. 35(6): p. 598-617. [CrossRef]

- Bakarich, S.E., et al., Recovery from applied strain in interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels with ionic and covalent cross-links. Soft Matter, 2012. 8(39): p. 9985-9988. [CrossRef]

- Führmann, T., et al., Click-crosslinked injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel is safe and biocompatible in the intrathecal space for ultimate use in regenerative strategies of the injured spinal cord. Methods, 2015. 84: p. 60-9. [CrossRef]

- Koh, L.-D., et al., Structures, mechanical properties and applications of silk fibroin materials. Progress in Polymer Science, 2015. 46: p. 86-110. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, G.S., et al., Antibiotic-loaded silica nanoparticle–collagen composite hydrogels with prolonged antimicrobial activity for wound infection prevention. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2014. 2(29): p. 4660-4670. [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.M., et al., Versatile click alginate hydrogels crosslinked via tetrazine–norbornene chemistry. Biomaterials, 2015. 50: p. 30-37. [CrossRef]

- Zamproni, L.N., et al., Neurorepair and regeneration of the brain: a decade of bioscaffolds and engineered microtissue. 2021. 9: p. 649891.

- Nih, L.R., et al., Dual-function injectable angiogenic biomaterial for the repair of brain tissue following stroke. 2018. 17(7): p. 642-651. [CrossRef]

- Thiele, J., et al., 25th anniversary article: Designer hydrogels for cell cultures: a materials selection guide. Adv Mater, 2014. 26(1): p. 125-47. [CrossRef]

- Namba, R., et al., Development of porous PEG hydrogels that enable efficient, uniform cell-seeding and permit early neural process extension. Acta Biomaterialia, 2009. 5(6): p. 1884-1897. [CrossRef]

- Trombino, S., et al., Strategies for Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogel Design in Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics, 2019. 11(8). [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.J., et al., Hydrogel-delivered brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes tissue repair and recovery after stroke. 2017. 37(3): p. 1030-1045.

- Jensen, G., J.L. Holloway, and S.E. Stabenfeldt, Hyaluronic Acid Biomaterials for Central Nervous System Regenerative Medicine. Cells, 2020. 9(9). [CrossRef]

- Ucar, B. and C. Humpel, Collagen for brain repair: therapeutic perspectives. Neural Regen Res, 2018. 13(4): p. 595-598. [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A., H.J. Moynihan, and L.M. Lucht, The structure of highly crosslinked poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res, 1985. 19(4): p. 397-411. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.B. and M.B. Huglin, DSC studies on states of water in crosslinked poly (methyl methacrylate-co-n-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) hydrogels. Polymer international, 1994. 33(3): p. 273-277. [CrossRef]

- Almany, L. and D. Seliktar, Biosynthetic hydrogel scaffolds made from fibrinogen and polyethylene glycol for 3D cell cultures. Biomaterials, 2005. 26(15): p. 2467-77. [CrossRef]

- Woerly, S., et al., Development of a sialic acid-containing hydrogel of poly [N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide]: characterization and implantation study. Biomacromolecules, 2008. 9(9): p. 2329-2337. [CrossRef]

- Woerly, S., et al., Neural tissue formation within porous hydrogels implanted in brain and spinal cord lesions: ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and diffusion studies. Tissue engineering, 1999. 5(5): p. 467-488. [CrossRef]

- Lesný, P., et al., Polymer hydrogels usable for nervous tissue repair. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy, 2002. 23(4): p. 243-247.

- Zhong, Y. and R.V. Bellamkonda, Biomaterials for the central nervous system. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2008. 5(26): p. 957-975. [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.C., et al., Increasing the pore sizes of bone-mimetic electrospun scaffolds comprised of polycaprolactone, collagen I and hydroxyapatite to enhance cell infiltration. Biomaterials, 2012. 33(2): p. 524-34. [CrossRef]

- Paşcu, E.I., J. Stokes, and G.B. McGuinness, Electrospun composites of PHBV, silk fibroin and nano-hydroxyapatite for bone tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl, 2013. 33(8): p. 4905-16. [CrossRef]

- Croisier, F. and C. Jérôme, Chitosan-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. European polymer journal, 2013. 49(4): p. 780-792. [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, B.L., et al., Dermal fibroblast infiltration of poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffolds fabricated by melt electrospinning in a direct writing mode. Biofabrication, 2013. 5(2): p. 025001. [CrossRef]

- Izal, I., et al., Culture of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on of poly(L-lactic acid) scaffolds: potential application for the tissue engineering of cartilage. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2013. 21(8): p. 1737-50. [CrossRef]

- Grad, S., et al., The use of biodegradable polyurethane scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering: potential and limitations. Biomaterials, 2003. 24(28): p. 5163-71. [CrossRef]

- Bini, T., et al., Electrospun poly (L-lactide-co-glycolide) biodegradable polymer nanofibre tubes for peripheral nerve regeneration. Nanotechnology, 2004. 15(11): p. 1459. [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.Y., et al., Aligned Protein-Polymer Composite Fibers Enhance Nerve Regeneration: A Potential Tissue-Engineering Platform. Adv Funct Mater, 2007. 17(8): p. 1288-1296. [CrossRef]

- Kartha, K.K., et al., Attogram sensing of trinitrotoluene with a self-assembled molecular gelator. J Am Chem Soc, 2012. 134(10): p. 4834-41. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinkhani, H., P.D. Hong, and D.S. Yu, Self-assembled proteins and peptides for regenerative medicine. Chem Rev, 2013. 113(7): p. 4837-61. [CrossRef]

- Chassenieux, C. and C. Tsitsilianis, Recent trends in pH/thermo-responsive self-assembling hydrogels: from polyions to peptide-based polymeric gelators. Soft Matter, 2016. 12(5): p. 1344-59. [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.H., Modular self-assembling biomaterials for directing cellular responses. Soft Matter, 2008. 4(12): p. 2310-2315. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., et al., Self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold promotes the reconstruction of acutely injured brain. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine, 2009. 5(3): p. 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Ellis-Behnke, R., K.-F. So, and S. Zhang, Molecular repair of the brain using self-assembling peptides. Chimica oggi, 2006. 24(4): p. 42-45.

- Ellis-Behnke, R., et al., Using nanotechnology to design potential therapies for CNS regeneration. Current pharmaceutical design, 2007. 13(24): p. 2519-2528. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., et al., A self-assembly peptide nanofibrous scaffold reduces inflammatory response and promotes functional recovery in a mouse model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Nanomedicine, 2016. 12(5): p. 1205-17. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B., et al., In vivo neuroprotective effect of a self-assembled peptide hydrogel. 2021. 408: p. 127295. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., Self-complementary oligopeptide matrices support mammalian cell attachment. 1995. 16(18): p. 1385-1393. [CrossRef]

- Leung, G.K.K., Y.C. Wang, and W.J.M.i.E. Wu, Peptide nanofiber scaffold for brain tissue reconstruction. 2012. 508: p. 177-190.

- Ellis-Behnke, R.G., et al., Nano neuro knitting: peptide nanofiber scaffold for brain repair and axon regeneration with functional return of vision. 2006. 103(13): p. 5054-5059. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y., et al., Amphiphilic peptide-tagged N-cadherin forms radial glial-like fibers that enhance neuronal migration in injured brain and promote sensorimotor recovery. Biomaterials, 2023. 294: p. 122003. [CrossRef]

- Sahab Negah, S., et al., Transplantation of human meningioma stem cells loaded on a self-assembling peptide nanoscaffold containing IKVAV improves traumatic brain injury in rats. Acta Biomater, 2019. 92: p. 132-144. [CrossRef]

- Teo, W., A Review on Electrospinning Design and Nanofibre Assemblies. Nanotechnology, 2006. 17: p. R89-R106. [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, J., et al., Interaction of cells and nanofiber scaffolds in tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 2008. 84(1): p. 34-48.

- Smith, L. and P. Ma, Nano-fibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Colloids and surfaces B: biointerfaces, 2004. 39(3): p. 125-131. [CrossRef]

- Kumbar, S., et al., Electrospun nanofiber scaffolds: engineering soft tissues. Biomedical materials, 2008. 3(3): p. 034002. [CrossRef]

- Alhosseini, S.N., et al., Synthesis and characterization of electrospun polyvinyl alcohol nanofibrous scaffolds modified by blending with chitosan for neural tissue engineering. Int J Nanomedicine, 2012. 7: p. 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., et al., From nano to micro to macro: Electrospun hierarchically structured polymeric fibers for biomedical applications. 2018. 81: p. 80-113. [CrossRef]

- Zech, J., et al., Electrospun Nimodipine-loaded fibers for nerve regeneration: Development and in vitro performance. 2020. 151: p. 116-126. [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, R.S., et al., Biomedical applications of electrospun nanofibers: Drug and nanoparticle delivery. 2018. 11(1): p. 5. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., et al., Electrospun polymer micro/nanofibers as pharmaceutical repositories for healthcare. 2019. 302: p. 19-41. [CrossRef]

- Gommans, H., et al., Electro-Optical Study of Subphthalocyanine in a Bilayer Organic Solar Cell. Advanced functional materials, 2007. 17(15): p. 2653-2658. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., et al., Electrospun nanofibers immobilized with collagen for neural stem cells culture. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, 2008. 19(2): p. 847-854. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J., et al., Functionalization strategies of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for nerve tissue engineering. 2021. 2: p. 260-279. [CrossRef]

- Sulejczak, D., et al., Electrospun nanofiber mat as a protector against the consequences of brain injury. Folia Neuropathol, 2014. 52(1): p. 56-69. [CrossRef]

- Maclean, F.L., et al., Galactose-functionalised PCL nanofibre scaffolds to attenuate inflammatory action of astrocytes in vitro and in vivo. J Mater Chem B, 2017. 5(22): p. 4073-4083. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D., Benefit and risk in tissue engineering. Materials Today, 2004. 7(5): p. 24-29. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H., et al., Towards a medically approved technology for alginate-based microcapsules allowing long-term immunoisolated transplantation. Journal of materials science: Materials in Medicine, 2005. 16(6): p. 491-501. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.M. and M.L. Oyen, Hydrogel composite materials for tissue engineering scaffolds. Jom, 2013. 65(4): p. 505-516. [CrossRef]

- Gunatillake, P.A., R. Adhikari, and N. Gadegaard, Biodegradable synthetic polymers for tissue engineering. Eur Cell Mater, 2003. 5(1): p. 1-16.

- Bergsma, J.E., et al., In vivo degradation and biocompatibility study of in vitro pre-degraded as-polymerized polylactide particles. Biomaterials, 1995. 16(4): p. 267-274. [CrossRef]

- Boontheekul, T., H.-J. Kong, and D.J. Mooney, Controlling alginate gel degradation utilizing partial oxidation and bimodal molecular weight distribution. Biomaterials, 2005. 26(15): p. 2455-2465. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K. and H. Tsuji, Effects of molecular weight and small amounts of d-lactide units on hydrolytic degradation of poly (l-lactic acid) s. Polymer degradation and stability, 2006. 91(8): p. 1665-1673. [CrossRef]

- Makadia, H.K. and S.J. Siegel, Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers, 2011. 3(3): p. 1377-1397. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H., A. Mizuno, and Y. Ikada, Properties and morphology of poly (L-lactide). III. Effects of initial crystallinity on long-term in vitro hydrolysis of high molecular weight poly (L-lactide) film in phosphate-buffered solution. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2000. 77(7): p. 1452-1464.

- Suzui, M., et al., Multiwalled carbon nanotubes intratracheally instilled into the rat lung induce development of pleural malignant mesothelioma and lung tumors. Cancer Sci, 2016. 107(7): p. 924-35. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al., Integrated printed BDNF-stimulated HUCMSCs-derived exosomes/collagen/chitosan biological scaffolds with 3D printing technology promoted the remodelling of neural networks after traumatic brain injury. Regen Biomater, 2023. 10: p. rbac085. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W., et al., Aligned Biofunctional Electrospun PLGA-LysoGM1 Scaffold for Traumatic Brain Injury Repair. ACS Biomater Sci Eng, 2020. 6(4): p. 2209-2218. [CrossRef]

- Mahumane, G.D., et al., Repositioning N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): NAC-Loaded Electrospun Drug Delivery Scaffolding for Potential Neural Tissue Engineering Application. Pharmaceutics, 2020. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., et al., Combining PLGA Scaffold and MSCs for Brain Tissue Engineering: A Potential Tool for Treatment of Brain Injury. Stem Cells Int, 2018. 2018: p. 5024175. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, Z., et al., Neurogenesis and vascularization of the damaged brain using a lactate-releasing biomimetic scaffold. Biomaterials, 2014. 35(17): p. 4769-81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury with Vepoloxamer (Purified Poloxamer 188). J Neurotrauma, 2018. 35(4): p. 661-670. [CrossRef]

- Macks, C., et al., Dexamethasone-Loaded Hydrogels Improve Motor and Cognitive Functions in a Rat Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Model. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(19). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y., et al., 3D printing of injury-preconditioned secretome/collagen/heparan sulfate scaffolds for neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2022. 13(1): p. 525. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al., Hyaluronan-based hydrogel integrating exosomes for traumatic brain injury repair by promoting angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Carbohydr Polym, 2023. 306: p. 120578. [CrossRef]

- Tanikawa, S., et al., Engineering of an electrically charged hydrogel implanted into a traumatic brain injury model for stepwise neuronal tissue reconstruction. Sci Rep, 2023. 13(1): p. 2233. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., et al., An ECM-Mimicking, Injectable, Viscoelastic Hydrogel for Treatment of Brain Lesions. Adv Healthc Mater, 2023. 12(1): p. e2201594. [CrossRef]

- Moisenovich, M.M., et al., Effect of Silk Fibroin on Neuroregeneration After Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurochem Res, 2019. 44(10): p. 2261-2272. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., et al., Surface-fill H2S-releasing silk fibroin hydrogel for brain repair through the repression of neuronal pyroptosis. 2022. 154: p. 259-274. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., et al., Implantation of regenerative complexes in traumatic brain injury canine models enhances the reconstruction of neural networks and motor function recovery. Theranostics, 2021. 11(2): p. 768-788. [CrossRef]

- Qian, F., et al., In Situ implantable, post-trauma microenvironment-responsive, ROS Depletion Hydrogels for the treatment of Traumatic brain injury. Biomaterials, 2021. 270: p. 120675. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., et al., Loading neural stem cells on hydrogel scaffold improves cell retention rate and promotes functional recovery in traumatic brain injury. Mater Today Bio, 2023. 19: p. 100606. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., et al., Angiogenic peptide hydrogels for treatment of traumatic brain injury. Bioact Mater, 2020. 5(1): p. 124-132. [CrossRef]

- Hackelbusch, S., et al., Hybrid microgels with thermo-tunable elasticity for controllable cell confinement. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2015. 4(12): p. 1841-1848. [CrossRef]

- Bjugstad, K., et al., Biocompatibility of poly (ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels in the brain: An analysis of the glial response across space and time. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2010. 95(1): p. 79-91. [CrossRef]

- Tamariz, E., et al., Delivery of chemotropic proteins and improvement of dopaminergic neuron outgrowth through a thixotropic hybrid nano-gel. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, 2011. 22(9): p. 2097-2109. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A., et al., Magnetic dehydrodipeptide-based self-assembled hydrogels for theragnostic applications. Nanomaterials, 2019. 9(4): p. 541. [CrossRef]

- Koss, K. and L. Unsworth, Neural tissue engineering: Bioresponsive nanoscaffolds using engineered self-assembling peptides. Acta biomaterialia, 2016. 44: p. 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Cui, W., Y. Zhou, and J. Chang, Electrospun nanofibrous materials for tissue engineering and drug delivery. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials, 2010. 11(1): p. 014108. [CrossRef]

- Sulejczak, D., et al., Original articleElectrospun nanofiber mat as a protector against the consequences of brain injury. Folia Neuropathologica, 2014. 52(1): p. 56-69. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).