Submitted:

01 September 2023

Posted:

04 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

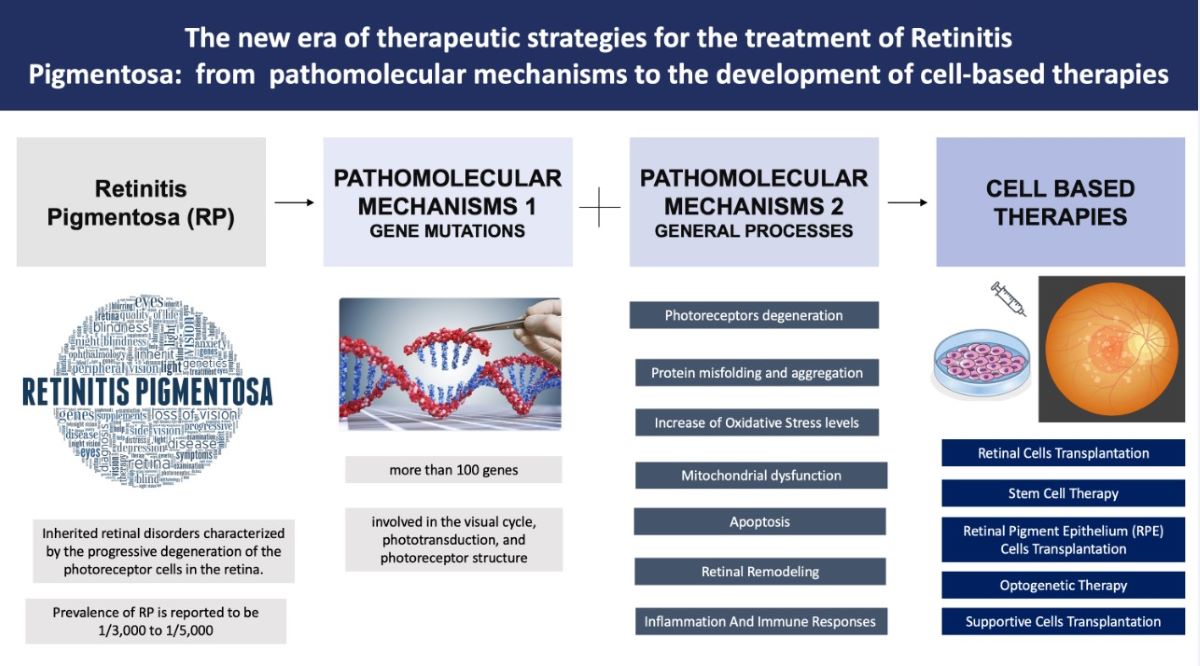

1. Introduction

2. Pathomolecular Mechanisms of Retinitis Pigmentosa

2.1.1. Main genes involved in RP

- Rhodopsin (RHO): mutations in the RHO gene are a common cause of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP) (15) Rhodopsin is a protein found in the rod photoreceptor cells of the retina, and it plays a critical role in the phototransduction pathway, which converts light signals into electrical signals that can be interpreted by the brain. Many kinds of RHO gene mutations damage the structure or function of rhodopsin, leading to the disruption and degeneration of rod photoreceptor cells. Over 150 types of mutations of the RHO gene have been described (16) (17). Most cases present point mutations that determine the substitution of an amino acid with consequent alteration of the protein’s structure or function. In addition to these mutations others involving abnormalities in the protein’s folding or trafficking were also described. Mutations in the rhodopsin gene which lead to the development of autosomal dominant forms of retinitis pigmentosa are divided into three different classes (18), distinguished by the dysfunction of rhodopsin and the nature of its accumulation in cell culture. In class 1 mutations, the photopigment remains functional, and its bond with 11-cis-retinal remains intact, while the accumulation of protein in embryonic cell culture happens specifically on the cytoplasmic membrane. Class 2 mutations cause damage to the composition of the photopigment and the buildup of faulty protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Class 3 encompasses mutations that result in the production of hyperphosphorylated rhodopsin, which exhibits a strong association with arrestin. The consequent rhodopsin-arrestin complex disturbs the structure of the endosomal compartment and impairs endocyte function. All these mutations have a strong impact on rhodopsin function as they can impair the light-sensitive ability of the protein or disrupt its signalling cascade within the photoreceptor cells (19) . These abnormalities can lead to defects in phototransduction, reduced sensitivity to light, and eventually, the death of rod photoreceptor cells.

- Peripherin/RDS (PRPH2): Mutations in the PRPH2 gene can cause autosomal dominant RP. The peripherin/RDS protein is involved in the structural integrity and function of photoreceptor outer segments. Specifically, PRPH2 is a transmembrane protein that is mainly expressed in rod and cone photoreceptor cells. It plays a crucial role in the structural integrity and organization of the photoreceptor outer segments, which are responsible for capturing and processing light signals. Mutations occurring in the PRPH2 gene can give rise to diverse structural anomalies in the peripherin 2 protein (20) . These abnormalities can impact crucial aspects such as protein folding, stability, and interactions with other proteins. The resultant disruption in the peripherin 2 function can hinder the formation of photoreceptor outer segments, consequently compromising the normal functionality of the photoreceptor cells. One common type of mutation in PRPH2 is the missense mutation which can affect the protein's folding, stability, and ability to interact with other proteins in the photoreceptor cells (21). Another type of common mutation is the frameshift mutation, mainly associated with anomalies in the protein's structure and function (20). Frameshift mutations often result in a truncated or non-functional Peripherin/RDS protein. Defective Peripherin/RDS protein can lead to mislocalization (22), aggregation, or degradation of the protein, affecting the integrity and function of the outer segments. This disruption ultimately results in the progressive degeneration of the photoreceptor cells and the characteristic symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa, such as night blindness, peripheral vision loss, and eventually central vision impairment.

- Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated (CNG) Channels. Mutations in genes encoding the CNG channels, such as CNGA1 and CNGB1, are associated with autosomal recessive RP (23). These channels are located in the outer segment of rod and cone photoreceptor cells and they are involved in the regulation of ion influx in response to light stimulation. They are responsible for the regulation of intracellular calcium and sodium ions, which are essential for phototransduction (the process by which light signals are converted into electrical signals in the retina thanks to hyperpolarization/depolarization phenomena). Mutations in genes encoding CNG channels can impair the normal function of these channels, disrupting the phototransduction process and leading to RP (24). Mutations in the CNGB1 and CNGA1 genes, which encode subunits of the CNG channels, have been associated with autosomal recessive RP (25). Mutations in the GNAT2 gene, which encodes the transducin alpha-subunit involved in CNG channel regulation, have also been linked to autosomal dominant RP. Impaired CNG channel function leads to abnormalities in the phototransduction process, where the conversion of light stimuli into electrical signals is disrupted (26). This alteration can result in reduced sensitivity to light, decreased visual acuity, and progressive vision loss, which are characteristic symptoms of RP. Additionally, dysfunctional CNG channels can lead to cellular stress, and oxidative damage, and ultimately trigger photoreceptor cell death (27). The loss of photoreceptor cells further contributes to the degeneration of the retina and the progression of RP.

- Retinal Pigment Epithelium-Specific 65 kDa Protein (RPE65). Mutations in the RPE65 gene are associated with autosomal recessive RP forms (28). The RPE65 gene encodes a protein called retinoid isomerohydrolase, which is primarily expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells. RPE65 is involved in the visual cycle, a process that regenerates the visual pigment rhodopsin in photoreceptor cells. It plays a crucial role in converting all-trans-retinol to 11-cis-retinal, which is essential for the proper functioning of photoreceptor cells. Mutations in the RPE65 gene result in a loss or dysfunction of the RPE65 protein, disrupting the visual cycle and impairing the regeneration of 11-cis-retinal (29). As a consequence, there is a decreased availability of 11-cis-retinal, leading to compromised phototransduction and eventual degeneration of photoreceptor cells (30) (31). Mutations in the RPE65 gene are also associated with a severe form of retinitis pigmentosa known as Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) or severe early childhood-onset retinal dystrophy (SECORD).

- Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator (RPGR). Mutations in the RPGR gene are a major cause of X-linked RP (XLRP), which primarily affects males as the RPGR gene is located on the X chromosome and it is involved in the structure and function of the photoreceptor connecting cilium (32) (33). The RPGR protein is indeed predominantly localized in the connecting cilium and outer segment of photoreceptor cells in the retina. These cellular structures play critical roles in the phototransduction cascade and the maintenance of normal vision. Mutations in the RPGR gene can affect the normal function of the RPGR protein, leading to retinal degeneration in XLRP (34). The specific pathogenic mechanisms underlying RPGR-related retinal degeneration are not fully understood. However, it is believed that the mutations result in impaired ciliary transport, altered protein-protein interactions, or disrupted signalling pathways, ultimately leading to photoreceptor cell death and vision loss (32) (35).

- Cone-Rod Homeobox Protein (CRX): Mutations in the CRX gene are associated with autosomal dominant RP form (36). The Cone-Rod Homeobox Protein is a transcription factor that plays a crucial role in the development and function of photoreceptor cells in the retina. CRX is primarily expressed in cone and rod photoreceptor cells of the retina where it regulates the expression of genes involved in photoreceptor development, differentiation, and maintenance. CRX is essential for the proper formation and function of these specialized cells, which are responsible for capturing and processing light signals (37). CRX regulates the expression of genes encoding various photoreceptor-specific proteins, including opsins (light-sensitive pigments), transducin, and other important components of the phototransduction pathway. It helps establish the unique characteristics and functions of cone and rod photoreceptor cells, ensuring their proper light-sensitive abilities (38). Mutations in the CRX gene can disrupt the normal function of the CRX protein, leading to impaired development and function of photoreceptor cells (37). This can result in the degeneration of cones and rods with different specific effects depending on the kind of CRX mutation, resulting in isolated cone dysfunction to more generalized cone-rod dystrophy (39).

- Usher Syndrome Genes. It has been demonstrated that some forms of RP are associated with Usher syndrome (40), which involves both hearing loss and vision impairment. Genes associated with Usher syndrome, such as USH2A, MYO7A, CLRN1 and CDH23, can cause RP in addition to other symptoms. It is a heterogeneous condition with several genes implicated in its development. The most commonly associated genes with Usher syndrome and RP include: Mutations in the MYO7A gene account for the majority of Usher syndrome type 1(USH1) cases (41). MYO7A encodes the protein myosin VIIA, which is involved in the structure and function of hair cells in the inner ear and the development and maintenance of photoreceptor cells in the retina. It plays an important role in the renewal of the outer photoreceptor discs, in the distribution and migration of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) melanosomes and phagosomes and the regulation of opsin transport in retinal photoreceptors. Mutations in the USH1C gene are also associated with Usher syndrome type 1. The USH1C gene encodes harmony, a scaffolding protein involved in the organization of hair cell stereocilia and the synaptic connections in the retina (41). Mutations in the USH2A gene are the most common cause of Usher syndrome type 2 (USH2). The USH2A gene encodes usherin, a protein involved in the maintenance of the structure and function of the photoreceptor cells and the hair cells of the inner ear (42) Mutations in the GPR98 gene, also known as ADGRV1 (Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor V1) are associated with Usher syndrome type 2. The GPR98 gene encodes the protein G protein-coupled receptor 98, which is involved in the development and function of sensory cells in the inner ear and the retina. Mutations in the CLRN1 gene are associated with Usher syndrome type 3. The CLRN1 gene encodes clarin-1, a protein found in the hair cells of the inner ear and the photoreceptor cells of the retina (43) which seems to play an important role in the development and homeostasis as a regulatory element for the synapses within the retina.

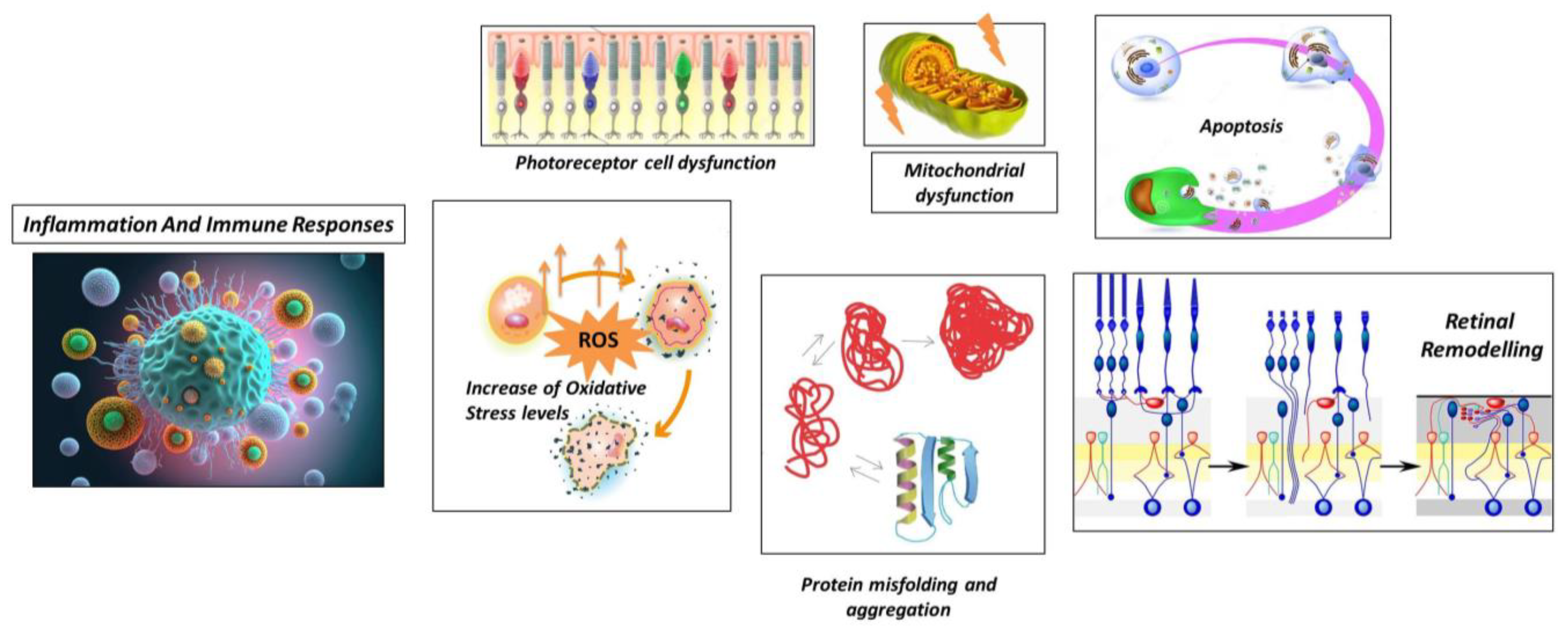

2.1.2. Mechanisms involved in RP

- Neuronal Rearrangement. As photoreceptor cells degenerate, there is a reorganization of the remaining retinal neurons, including bipolar cells, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells. These neurons undergo structural changes and establish new connections with each other to compensate for the loss of photoreceptor input (65).

- Bipolar Cell Dystrophy: Bipolar cells, the second-order neurons in the visual pathway, also undergo structural and functional changes in RP. They may exhibit abnormal dendritic sprouting or retraction, leading to the formation of ectopic synapses. These changes can result in altered signal processing and contribute to visual abnormalities in RP (66).

- Müller Cell Gliosis: Müller cells are the major glial cells in the retina and play a crucial role in maintaining retinal homeostasis. In response to photoreceptor cell degeneration, Müller cells undergo gliotic changes, becoming activated and hypertrophic (67). This gliosis involves changes in gene expression, increased production of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and alterations in their structural morphology. Müller cell gliosis can have both protective and detrimental effects on retinal function and can influence the survival and function of remaining retinal neurons (68).

- Synaptic Remodeling: In RP, there is a reorganization of synaptic connections in the retina. As photoreceptor cells degenerate, the synaptic contacts between photoreceptor cells and downstream neurons, such as bipolar cells and horizontal cells, change. New synaptic connections may form between bipolar cells and surviving cones or between bipolar cells and other retinal neurons. This synaptic remodelling can lead to altered signal processing and contribute to the rewiring of the retinal circuitry (69).

- 5.

- Microglial Activation: Microglia, the resident immune cells of the retina, become activated in response to photoreceptor cell death and degeneration. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species. While microglial activation initially aims to clear debris and promote tissue repair, chronic or excessive activation can lead to neuroinflammation and further damage to the retina (72).

- 6.

- Infiltration of Immune Cells In some cases of RP, immune cells from the bloodstream can infiltrate the retina, further contributing to the inflammatory response. These immune cells, including macrophages and T cells, release inflammatory mediators that can exacerbate retinal damage (73).

- 7.

- Cytokine Imbalance In RP, there is evidence of an imbalance in cytokine signalling in the retina. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), are upregulated, while anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), are downregulated. This imbalance can perpetuate the inflammatory response and contribute to the degeneration of photoreceptor cells (74) (75).

- 8.

- Complement System Activation: Activation of the complement system can lead to the deposition of complement proteins on photoreceptor cells and subsequent immune-mediated damage (73).

- 9.

- Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: Oxidative stress, resulting from the imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant defence mechanisms, can further contribute to inflammation in RP. ROS can activate various intracellular signalling pathways involved in inflammatory responses, amplifying the inflammatory cascade and exacerbating retinal damage (76).

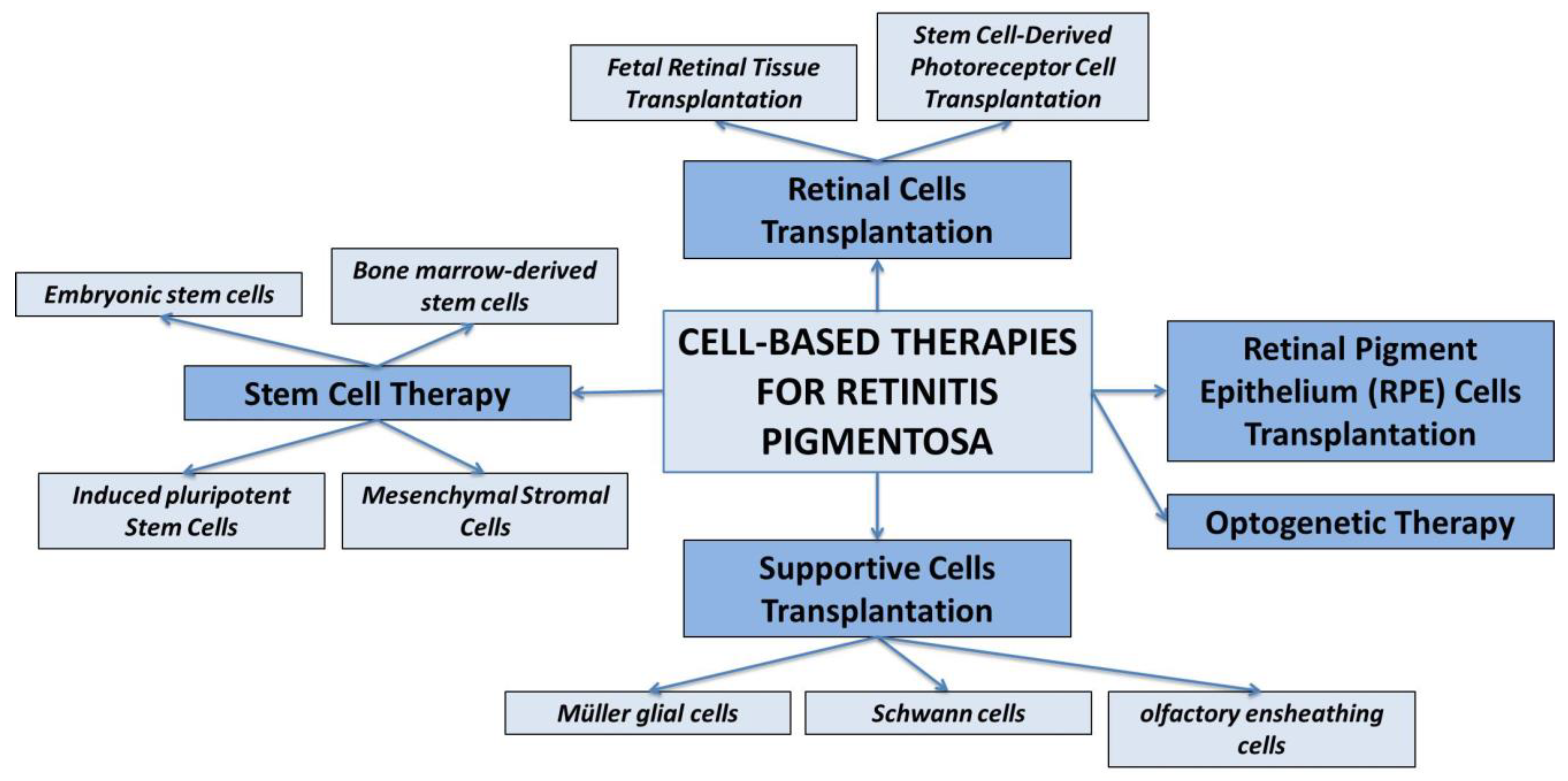

3. Cell-Based Therapies for Retinitis Pigmentosa

- Fetal Retinal Tissue Transplantation. Fetal retinal tissue, obtained from donor fetuses, can be transplanted into the subretinal space of RP patients. The transplanted cells can integrate into the host retina and potentially improve visual function. However, the availability of fetal tissue is limited, and immunological compatibility needs to be considered (80).

- Stem Cell-Derived Photoreceptor Cell Transplantation. Pluripotent stem cells, such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), can be differentiated into photoreceptor-like cells in vitro (81) (82). These cells can then be transplanted into the retina to replace the degenerated photoreceptor cells.

- Channelrhodopsin-based therapy: Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) is a light-sensitive protein derived from algae. In optogenetic therapy for RP, ChR2 is introduced into retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) or bipolar cells. When activated by light of specific wavelengths, ChR2 can depolarize the cells and initiate electrical signals, mimicking the function of photoreceptor cells. This approach aims to restore light sensitivity and enable visual information to be transmitted to the brain (116).

- Halorhodopsin-based therapy: Halorhodopsin (NpHR) is a light-sensitive protein that responds to yellow or amber light. In optogenetic therapy, NpHR can be introduced into bipolar cells or RGCs to allow the cells to be inhibited in response to light stimulation. By selectively inhibiting specific cell types, such as ON or OFF bipolar cells, the retinal circuitry can be modulated to enhance visual processing and restore functional vision (117) (118).

- Red-shifted opsin-based therapy: In addition to ChR2 and NpHR, other light-sensitive proteins with red-shifted absorption spectra are being explored for optogenetic therapy in RP. These proteins, such as ReaChR or ChrimsonR, can be activated by longer wavelengths of light, including red or near-infrared light. By utilizing these red-shifted opsins, optogenetic therapy can potentially penetrate deeper into the retina and improve light sensitivity in RP patients (119).

Strategies for Promoting the Survival and Function of Existing Retinal Cells

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamel, C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2006, 1, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbakel, S.K.; van Huet, R.A.C.; Boon, C.J.F.; den Hollander, A.I.; Collin, R.W.J.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Hoyng, C.B.; Roepman, R.; Klevering, B.J. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 66, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, G.A.; Anderson, R.J.; Lourenco, P. Prevalence of posterior subcapsular lens opacities in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1985, 69, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Ogata, K.; Sugawara, T.; Hiramatsu, A.; Shibata, M.; Mitamura, Y. Macular abnormalities in patients with retinitis pigmentosa: prevalence on OCT examination and outcomes of vitreoretinal surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011, 89, e122–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, N.; Moore, A.T.; Weleber, R.G.; Michaelides, M. Leber congenital amaurosis/early-onset severe retinal dystrophy: clinical features, molecular genetics and therapeutic interventions. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.Y.; Kulbay, M.; Toameh, D.; Xu, A.Q.; Kalevar, A.; Tran, S.D. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Novel Therapeutic Targets and Drug Development. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, A.M.; High, K.A.; Auricchio, A.; Wright, J.F.; Pierce, E.A.; Testa, F.; Mingozzi, F.; Bennicelli, J.L.; Ying, G.-S.; Rossi, S.; et al. Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber’s congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, J.W.; Smith, A.J.; Barker, S.S.; Robbie, S.; Henderson, R.; Balaggan, K.; Viswanathan, A.; Holder, G.E.; Stockman, A.; Tyler, N.; et al. Effect of Gene Therapy on Visual Function in Leber's Congenital Amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodi, A.; Banfi, S.; Testa, F.; Della Corte, M.; Passerini, I.; Pelo, E.; Rossi, S.; Simonelli, F. ; Italian IRD Working Group RPE65-associated inherited retinal diseases: consensus recommendations for eligibility to gene therapy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acland, G.M.; Aguirre, G.D.; Ray, J.; Zhang, Q.; Aleman, T.S.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Pearce-Kelling, S.E.; Anand, V.; Zeng, Y.; Maguire, A.M.; et al. Gene therapy restores vision in a canine model of childhood blindness. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, E.A.; Bennett, J. The Status ofRPE65Gene Therapy Trials: Safety and Efficacy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a017285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, X.; Pang, J.-J.; Zhang, H.; Mansfield, D. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Disease Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Therapies. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 2015, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, S.; Di Iorio, E.; Barbaro, V.; Ponzin, D.; Sorrentino, F.S.; Parmeggiani, F. Retinitis pigmentosa: Genes and disease mechanisms. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiger, S.P.; Sullivan, L.S.; Bowne, S.J. Genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Clin. Genet. 2013, 84, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, D.; Aguila, M.; Bellingham, J.; Li, W.; McCulley, C.; Reeves, P.J.; Cheetham, M.E. The molecular and cellular basis of rhodopsin retinitis pigmentosa reveals potential strategies for therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 62, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, D.; Aguila, M.; Bellingham, J.; Li, W.; McCulley, C.; Reeves, P.J.; Cheetham, M.E. The molecular and cellular basis of rhodopsin retinitis pigmentosa reveals potential strategies for therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 62, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, A.S.; Rossmiller, B.; Mao, H. Gene Augmentation for adRP Mutations in RHO. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a017400–a017400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J.-Z.; Vega, C.; Jun, W.; Sung, C.-H. Structural and functional impairment of endocytic pathways by retinitis pigmentosa mutant rhodopsin-arrestin complexes. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, B.; Vats, A.; Tang, H.; Seibel, W.; Swaroop, M.; Tawa, G.; Zheng, W.; Byrne, L.; Schurdak, M.; et al. Pharmacological clearance of misfolded rhodopsin for the treatment of RHO -associated retinitis pigmentosa. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 10146–10167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.H.; Khan, M.; Rooijakkers, A.A.; Mulders, T.; Haer-Wigman, L.; Boon, C.J.; Klaver, C.C.; van den Born, L.I.; Hoyng, C.B.; Cremers, F.P.; et al. PRPH2 mutation update: In silico assessment of 245 reported and 7 novel variants in patients with retinal disease. Hum. Mutat. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco-Martin, R.M.; Sanchez-Tocino, H.T.; Desco, C.; Usategui-Martín, R.; Tellería, J.J. PRPH2-Related Retinal Diseases: Broadening the Clinical Spectrum and Describing a New Mutation. Genes 2020, 11, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuck, M.W.; Conley, S.M.; Naash, M.I. PRPH2/RDS and ROM-1: Historical context, current views and future considerations. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 52, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, M.J.; Priglinger, S.G.; Biel, M.; Michalakis, S. Biology, Pathobiology and Gene Therapy of CNG Channel-Related Retinopathies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalakis, S.; Becirovic, E.; Biel, M. Retinal Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Channels: From Pathophysiology to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, M.J.; Petersen-Jones, S.M.; Michalakis, S. CNG channel-related retinitis pigmentosa. Vis. Res. 2023, 208, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, M.J.; Priglinger, S.G.; Biel, M.; Michalakis, S. Biology, Pathobiology and Gene Therapy of CNG Channel-Related Retinopathies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duricka, D.L.; Brown, R.L.; Varnum, M.D. Defective trafficking of cone photoreceptor CNG channels induces the unfolded protein response and ER-stress-associated cell death. Biochem. J. 2011, 441, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Bender, S.F.; Widmer, F.; van der Heijden, MGA. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. PNAS 2014, 111, 5266–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallum, J.M.F.; Kaur, V.P.; Shaikh, J.; Banhazi, J.; Spera, C.; Aouadj, C.; Viriato, D.; Fischer, M.D. Epidemiology of Mutations in the 65-kDa Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE65) Gene-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophies: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 1179–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallum, J.M.F.; Kaur, V.P.; Shaikh, J.; Banhazi, J.; Spera, C.; Aouadj, C.; Viriato, D.; Fischer, M.D. Epidemiology of Mutations in the 65-kDa Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE65) Gene-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophies: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 1179–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.A.; Gyürüs, P.; Fleischer, L.L.; Bingham, E.L.; McHenry, C.L.; Apfelstedt-Sylla, E.; Zrenner, E.; Lorenz, B.; Richards, J.E.; Jacobson, S.G.; et al. Genetics and phenotypes of RPE65 mutations in inherited retinal degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 4293–4299. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Parapuram, S.K.; Hurd, T.W.; Behnam, B.; Margolis, B.; Swaroop, A.; Khanna, H. Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator (RPGR) protein isoforms in mammalian retina: Insights into X-linked Retinitis Pigmentosa and associated ciliopathies. Vis. Res. 2008, 48, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinikoor-Imler, L.C.; Simpson, C.; Narayanan, D.; Abbasi, S.; Lally, C. Prevalence of RPGR-mutated X-linked retinitis pigmentosa among males. Ophthalmic Genet. 2022, 43, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga-Zamalloa, C.A.; Atkins, S.J.; Peranen, J.; Swaroop, A.; Khanna, H. Interaction of retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) with RAB8A GTPase: implications for cilia dysfunction and photoreceptor degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 3591–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga-Zamalloa, C.; Swaroop, A.; Khanna, H. Multiprotein Complexes of Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator (RPGR), a Ciliary Protein Mutated in X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa (XLRP). 664. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, S. Gene Augmentation for Autosomal Dominant CRX-Associated Retinopathies. 1415. [CrossRef]

- Swain, P.K.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.-L.; Affatigato, L.M.; Coats, C.L.; Brady, K.D.; A Fishman, G.; Jacobson, S.G.; Swaroop, A.; Stone, E.; et al. Mutations in the Cone-Rod Homeobox Gene Are Associated with the Cone-Rod Dystrophy Photoreceptor Degeneration. Neuron 1997, 19, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, C.L.; Gregory-Evans, C.Y.; Furukawa, T.; Papaioannou, M.; Looser, J.; Ploder, L.; Bellingham, J.; Ng, D.; Herbrick, J.-A.S.; Duncan, A.; et al. Cone-Rod Dystrophy Due to Mutations in a Novel Photoreceptor-Specific Homeobox Gene () Essential for Maintenance of the Photoreceptor. Cell 1997, 91, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Q.-L.; Xu, S.; Liu, I.; Li, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zack, D.J. Functional analysis of cone-rod homeobox (CRX) mutations associated with retinal dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster-García, C.; García-Bohórquez, B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Aller, E.; Jaijo, T.; Millán, J.M.; García-García, G. Usher Syndrome: Genetics of a Human Ciliopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenassi, E.; Saihan, Z.; Cipriani, V.; Stabej, P.L.Q.; Moore, A.T.; Luxon, L.M.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.; Webster, A.R. Natural History and Retinal Structure in Patients with Usher Syndrome Type 1 Owing to MYO7A Mutation. Ophthalmology 2013, 121, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; Fadl, B.R.; Becker, M.M.; A Wunderlich, K.; Schäfer, J.; Sturm, D.; Fritze, J.; Gür, B.; Kaplan, L.; Andreani, T.; et al. Expression and subcellular localization ofUSH1C/harmonin in human retina provides insights into pathomechanisms and therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022, 32, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnam, K.; Västinsalo, H.; Roorda, A.; Sankila, E.-M.K.; Duncan, J.L. Cone Structure in Patients With Usher Syndrome Type III and Mutations in the Clarin 1 Gene. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013, 131, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Li, P.; Yao, K. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Progress in Molecular Pathology and Biotherapeutical Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, A.; Meshkat, B.I.; Jablonski, M.M.; Hollingsworth, T. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis Underlying Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H.; LaVail, M.M. Misfolded Proteins and Retinal Dystrophies. 664. [CrossRef]

- Tzekov, R.; Stein, L.; Kaushal, S. Protein Misfolding and Retinal Degeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a007492–a007492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingolo, E.M.; Casillo, L.; Contento, L.; Toja, F.; Florido, A. Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP): The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Degenerative Process Progression. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallenga, C.E.; Lonardi, M.; Pacetti, S.; Violanti, S.S.; Tassinari, P.; Di Virgilio, F.; Tognon, M.; Perri, P. Molecular Mechanisms Related to Oxidative Stress in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, E.B.; Marfany, G. The Relevance of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Retinal Dystrophies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeima, K.; Rogers, B.S.; Lu, L.; Campochiaro, P.A. Antioxidants reduce cone cell death in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 11300–11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Léveillard, T. Modulating antioxidant systems as a therapeutic approach to retinal degeneration. Redox Biol. 2022, 57, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevere, E.; Toft-Kehler, A.K.; Vohra, R.; Kolko, M.; Moons, L.; Van Hove, I. Mitochondrial dysfunction underlying outer retinal diseases. Mitochondrion 2017, 36, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barot, M.; Gokulgandhi, M.R.; Mitra, A.K. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Retinal Diseases. Curr. Eye Res. 2011, 36, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Chen, X.; A, L.; Gao, H.; Zhao, M.; Ge, L.; Li, M.; Yang, C.; Gong, Y.; Gu, Z.; et al. Alleviation of Photoreceptor Degeneration Based on Fullerenols in rd1 Mice by Reversing Mitochondrial Dysfunction via Modulation of Mitochondrial DNA Transcription and Leakage. Small 2023, e2205998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- others, Dafni Vlachantoni and. Evidence of severe mitochondrial oxidative stress and a protective effect of low oxygen in mouse models of inherited photoreceptor degeneration, Human Molecular Genetics, Volume 20, Issue 2, , Pages 322–335, ht. 15 January.

- Valeria Marigo, Meltem Kutluer, Li Huang, Antonella Comitato, Davide Schiroli, Frank Schwede, Andreas Rentsch, Per A R Ekstrom, Francois Paquet-Durand. Decrease of intracellular calcium to restrain rod cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019;60(9):4866.

- Das, S.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J.; Christensen, G.; Belhadj, S.; Tolone, A.; Paquet-Durand, F. The role of cGMP-signalling and calcium-signalling in photoreceptor cell death: perspectives for therapy development. 473, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, M.; Geng, Z.; Khattak, S.; Ji, X.; Wu, D.; Dang, Y. Role of Oxidative Stress in Retinal Disease and the Early Intervention Strategies: A Review. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Milam, A.H. Apoptosis in Retinitis Pigmentosa. 1995; 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. Apoptosis, retinitis pigmentosa, and degeneration. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1994, 72, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, F.; Megaw, R. Mechanisms of Photoreceptor Death in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Genes 2020, 11, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.W.; Kondo, M.; Terasaki, H.; Lin, Y.; McCall, M.; Marc, R.E. Retinal remodeling. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 56, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.W.; Pfeiffer, R.L.; Ferrell, W.D.; Watt, C.B.; Marmor, M.; Marc, R.E. Retinal remodeling in human retinitis pigmentosa. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 150, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, R.E.; Jones, B.W.; Watt, C.B.; Strettoi, E. Neural remodeling in retinal degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2003, 22, 607–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gil, N.; Maneu, V.; Kutsyr, O.; Fernández-Sánchez, L.; Sánchez-Sáez, X.; Sánchez-Castillo, C.; Campello, L.; Lax, P.; Pinilla, I.; Cuenca, N. Cellular and molecular alterations in neurons and glial cells in inherited retinal degeneration. Front. Neuroanat. 2022, 16, 984052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Huang, X.; He, J.; Zou, T.; Chen, X.; Xu, H. The roles of microglia in neural remodeling during retinal degeneration. . 2021, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, C. Gordon, Eric J. Knott, Kristopher G. Sheets, Cornelius E. Regan, Jr., Nicolas G. Bazan. Müller Cell Reactive Gliosis Contributes To Retinal Degeneration In Ccl2-/-/Cx3cr1-/- Mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52(14):1375.

- Soto, F.; Kerschensteiner, D. Synaptic remodeling of neuronal circuits in early retinal degeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, R.L.; Jones, B.W. Current perspective on retinal remodeling: Implications for therapeutics. Front. Neuroanat. 2022, 16, 1099348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noailles, A.; Maneu, V.; Campello, L.; Gómez-Vicente, V.; Lax, P.; Cuenca, N. Persistent inflammatory state after photoreceptor loss in an animal model of retinal degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, K.; So, K.-F.; Tipoe, G.L.; Lin, B. Suppression of Microglial Activation Is Neuroprotective in a Mouse Model of Human Retinitis Pigmentosa. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 8139–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.V.; Mishra, A.; Muniyasamy, A.; Sinha, P.; Sahu, P.; Kesarwani, A.; Jain, K.; Nagarajan, P.; Scaria, V.; Agarwal, M.; et al. Immunological consequences of compromised ocular immune privilege accelerate retinal degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-González, L.; Velasco, S.; Campillo, I.; Rodrigo, R. Retinal Inflammation, Cell Death and Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okita, A.; Murakami, Y.; Shimokawa, S.; Funatsu, J.; Fujiwara, K.; Nakatake, S.; Koyanagi, Y.; Akiyama, M.; Takeda, A.; Hisatomi, T.; et al. Changes of Serum Inflammatory Molecules and Their Relationships with Visual Function in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 30–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Sonoda, K.-H. Oxidative Stress and Microglial Response in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hou, C.; Yan, N. Neuroinflammation in retinitis pigmentosa: Therapies targeting the innate immune system. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1059947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, J.W.; Mahmoudzadeh, R.; Kuriyan, A.E. Cell-based therapies for retinal diseases: a review of clinical trials and direct to consumer “cell therapy” clinics. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, T.; Ruff, A. Retinal cell transplantation in retinitis pigmentosa. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 11, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, R.; Pearson, R.; MacNeil, A.; Douglas, R.H.; Salt, T.E.; Akimoto, M.; Swaroop, A.; Sowden, J.; Ali, R. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature 2006, 444, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, A.; Laver, C.; Joe, A.W.; Gregory-Evans, K. Efficient Production of Photoreceptor Precursor Cells from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. 1307. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Hsu, C.-W.; Erol, D.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.-H.; Davis, R.J.; Egli, D.; Tsang, S.H. Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPS) Grafts in a Preclinical Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.Z.; Utheim, T.P.; Eidet, J.R. Retinal Pigment Epithelium Transplantation: Past, Present, and Future. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2022, 17, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Thomson, H.A.J.; Luff, A.J.; Lotery, A.J. Retinal pigment epithelium transplantation: concepts, challenges, and future prospects. Eye 2015, 29, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heravi, M.; Rasoulinejad, S.A. Potential of Müller Glial Cells in Regeneration of Retina; Clinical and Molecular Approach., 13, 50–59.

- Eastlake, K.; Lamb, W.; Luis, J.; Khaw, P.; Jayaram, H.; Limb, G. Prospects for the application of Müller glia and their derivatives in retinal regenerative therapies. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 85, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gu, P. Stem/progenitor cell-based transplantation for retinal degeneration: a review of clinical trials. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, R.C. Stem cell therapy for retinal diseases: update. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2011, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.Y.-H.; Poon, M.-W.; Pang, R.T.-W.; Lian, Q.; Wong, D. Promises of stem cell therapy for retinal degenerative diseases. Graefe's Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2011, 249, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ghazaryan, E.; Li, Y.; Xie, J.; Su, G. Recent Advances of Stem Cell Therapy for Retinitis Pigmentosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 14456–14474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.-B.; Okamoto, S.; Xiang, P.; Takahashi, M. Integration-Free Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Derived from Retinitis Pigmentosa Patient for Disease Modeling. STEM CELLS Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idelson, M.; Alper, R.; Obolensky, A.; Ben-Shushan, E.; Hemo, I.; Yachimovich-Cohen, N.; Khaner, H.; Smith, Y.; Wiser, O.; Gropp, M.; et al. Directed Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells into Functional Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 5, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vugler, A.; Lawrence, J.; Walsh, J.; Carr, A.; Gias, C.; Semo, M.; Ahmado, A.; da Cruz, L.; Andrews, P.; Coffey, P. Embryonic stem cells and retinal repair. Mech. Dev. 2007, 124, 807–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.-K.; Tosi, J.; Kasanuki, J.M.; Chou, C.L.; Kong, J.; Parmalee, N.; Wert, K.J.; Allikmets, R.; Lai, C.-C.; Chien, C.-L.; et al. Transplantation of Reprogrammed Embryonic Stem Cells Improves Visual Function in a Mouse Model for Retinitis Pigmentosa. Transplantation 2010, 89, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, P.; Robey, P.G.; Simmons, P.J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Revisiting History, Concepts, and Assays. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 2, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.; Russo, C.; Longo, A.; Anfuso, C.D.; Lupo, G.; Furno, D.L.; Giuffrida, R.; Giurdanella, G. Potential therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of eye diseases. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, S.; Magdalene, D.; Deshmukh, S.; Das, D.; Jaganathan, B.G. A Review on Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 1154–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Based Strategies for Retinal Diseases. Genes 2022, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holan, V.; Palacka, K.; Hermankova, B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Experimental Models and Clinical Trials. Cells 2021, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboussin. ; Buffault, J.; Brignole-Baudouin, F.; Goazigo, A.R.-L.; Riancho, L.; Olmiere, C.; Sahel, J.-A.; Parsadaniantz, S.M.; Baudouin, C. Evaluation of neuroprotective and immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells in an ex vivo retinal explant model. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavely, R.; Nurgali, K. The emerging antioxidant paradigm of mesenchymal stem cell therapy. STEM CELLS Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, C.; Gatti, M.; Prata, C.; Hrelia, S.; Maraldi, T. Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Counteracting Oxidative Stress—Related Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.L.S.; Kumar, S.; Mok, P.L. Cellular Reparative Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Retinal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holan, V.; Palacka, K.; Hermankova, B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Experimental Models and Clinical Trials. Cells 2021, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruitenberg, M.J.; Vukovic, J.; Sarich, J.; Busfield, S.J.; Plant, G.W.; Yang, H.; He, B.-R.; Hao, D.-J.; Su, Z.; He, C.; et al. Olfactory Ensheathing Cells: Characteristics, Genetic Engineering, and Therapeutic Potential. J. Neurotrauma 2006, 23, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, S.J.; Li, Y.C.; Xie, J.; Li, Y.; Raisman, G.; Zeng, Y.X.; He, J.R.; Weng, C.H.; Yin, Z.Q. Transplanted Olfactory Ensheathing Cells Reduce Retinal Degeneration in Royal College of Surgeons Rats. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, P.; Robey, P.G.; Simmons, P.J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Revisiting History, Concepts, and Assays. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 2, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.; Russo, C.; Longo, A.; Anfuso, C.D.; Lupo, G.; Furno, D.L.; Giuffrida, R.; Giurdanella, G. Potential therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of eye diseases. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, S.; Magdalene, D.; Deshmukh, S.; Das, D.; Jaganathan, B.G. A Review on Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 1154–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Based Strategies for Retinal Diseases. Genes 2022, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holan, V.; Palacka, K.; Hermankova, B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Experimental Models and Clinical Trials. Cells 2021, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboussin. ; Buffault, J.; Brignole-Baudouin, F.; Goazigo, A.R.-L.; Riancho, L.; Olmiere, C.; Sahel, J.-A.; Parsadaniantz, S.M.; Baudouin, C. Evaluation of neuroprotective and immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells in an ex vivo retinal explant model. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavely, R.; Nurgali, K. The emerging antioxidant paradigm of mesenchymal stem cell therapy. STEM CELLS Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, C.; Gatti, M.; Prata, C.; Hrelia, S.; Maraldi, T. Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Counteracting Oxidative Stress—Related Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.L.S.; Kumar, S.; Mok, P.L. Cellular Reparative Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Retinal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holan, V.; Palacka, K.; Hermankova, B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Experimental Models and Clinical Trials. Cells 2021, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruitenberg, M.J.; Vukovic, J.; Sarich, J.; Busfield, S.J.; Plant, G.W.; Yang, H.; He, B.-R.; Hao, D.-J.; Su, Z.; He, C.; et al. Olfactory Ensheathing Cells: Characteristics, Genetic Engineering, and Therapeutic Potential. J. Neurotrauma 2006, 23, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, S.J.; Li, Y.C.; Xie, J.; Li, Y.; Raisman, G.; Zeng, Y.X.; He, J.R.; Weng, C.H.; Yin, Z.Q. Transplanted Olfactory Ensheathing Cells Reduce Retinal Degeneration in Royal College of Surgeons Rats. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ghazaryan, E.; Li, Y.; Xie, J.; Su, G. Recent Advances of Stem Cell Therapy for Retinitis Pigmentosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 14456–14474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, H.J.; Ng, T.F.; Kurimoto, Y.; Kirov, I.; Shatos, M.; Coffey, P.; Young, M.J. Multipotent Retinal Progenitors Express Developmental Markers, Differentiate into Retinal Neurons, and Preserve Light-Mediated Behavior. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 4167–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Klassen, H.; Zhang, X.; Young, M. Laser injury promotes migration and integration of retinal progenitor cells into host retina. Mol. Vis. 2010, 16, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- West, E.; Pearson, R.; Tschernutter, M.; Sowden, J.; MacLaren, R.; Ali, R. Pharmacological disruption of the outer limiting membrane leads to increased retinal integration of transplanted photoreceptor precursors. Exp. Eye Res. 2008, 86, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahel, J.-A.; Boulanger-Scemama, E.; Pagot, C.; Arleo, A.; Galluppi, F.; Martel, J.N.; Degli Esposti, S.; Delaux, A.; de Saint Aubert, J.-B.; de Montleau, C.; et al. Partial recovery of visual function in a blind patient after optogenetic therapy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busskamp, V.; Picaud, S.; Sahel, J.A.; Roska, B. Optogenetic therapy for retinitis pigmentosa. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.R.; Moore, A.T. Optogenetic approaches to therapy for inherited retinal degenerations. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 4623–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busskamp, V.; Duebel, J.; Balya, D.; Fradot, M.; Viney, T.J.; Siegert, S.; Groner, A.C.; Cabuy, E.; Forster, V.; Seeliger, M.; et al. Genetic Reactivation of Cone Photoreceptors Restores Visual Responses in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Science 2010, 329, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, D.; Tomita, H.; Maeda, A. Optogenetic Therapy for Visual Restoration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseev, A.; Gordeliy, V.; Bamberg, E. Rhodopsin-Based Optogenetics: Basics and Applications. 2501. [CrossRef]

- Chow, B.Y.; Han, X.; Dobry, A.S.; Qian, X.; Chuong, A.S.; Li, M.; Henninger, M.A.; Belfort, G.M.; Lin, Y.; Monahan, P.E.; et al. High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature 2010, 463, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, S.; Flossmann, T.; Gao, S.; Witte, O.W.; Nagel, G.; Holthoff, K.; Kirmse, K. Optimized photo-stimulation of halorhodopsin for long-term neuronal inhibition. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Campbell, R.E.; Côté, D.C.; Paquet, M.-E. Challenges for Therapeutic Applications of Opsin-Based Optogenetic Tools in Humans. Front. Neural Circuits 2020, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; He, T.; Chen, R.; Cui, H.; Li, G. Impact of neurotrophic factors combination therapy on retinitis pigmentosa. J. Int. Med Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsini, B.; Iarossi, G.; Chiaretti, A.; Ruggiero, A.; Manni, L.; Galli-Resta, L.; Corbo, G.; Abed, E. NGF eye-drops topical administration in patients with retinitis pigmentosa, a pilot study. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieving, P.A.; Caruso, R.C.; Tao, W.; Coleman, H.R.; Thompson, D.J.S.; Fullmer, K.R.; Bush, R.A. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) for human retinal degeneration: Phase I trial of CNTF delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3896–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.Y.; Kulbay, M.; Toameh, D.; Xu, A.Q.; Kalevar, A.; Tran, S.D. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Novel Therapeutic Targets and Drug Development. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.T.; Jastrzebska, B. Neuroinflammation as a Therapeutic Target in Retinitis Pigmentosa and Quercetin as Its Potential Modulator. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeima, K.; Rogers, B.S.; Campochiaro, P.A. Antioxidants slow photoreceptor cell death in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 213, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Usui, S.; Zafar, A.-B.; Oveson, B.C.; Jo, Y.-J.; Lu, L.; Masoudi, S.; Campochiaro, P.A. N-acetylcysteine promotes long-term survival of cones in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 226, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jaganathan, B.G. Stem Cell Therapy for Retinal Degeneration: The Evidence to Date. Biol. Targets Ther. 2021, ume 15, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, J.W.; Mahmoudzadeh, R.; Kuriyan, A.E. Cell-based therapies for retinal diseases: a review of clinical trials and direct to consumer “cell therapy” clinics. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GENE/PROTEIN | FUNCTION | EFFECTS OF MUTATIONS | EFFECTS ON RETINA’S STRUCTURE |

| Rhodopsin (RHO) | found in rod cells, plays a central role in phototransduction and rod photoreceptor cell health | alteration of the protein’s structure/function, abnormalities in the protein’s folding or trafficking | disruption and degeneration of rod photoreceptor cells, defects in phototransduction, reduced sensitivity to light |

| Peripherin/RDS (PRPH2) | found in the rod and cone cells plays a crucial role in the structural integrity and organization of the photoreceptor outer segments (essential for disk morphogenesis) | alteration of protein folding, stability, and interactions with other proteins. | Alteration of integrity and function of the outer segments, progressive degeneration of the photoreceptor associated with peripheral vision loss, and central vision impairment. |

| Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated (CNG) Channels | Non selective cation channels located in the outer segment of rod and cone photoreceptor cells are involved in the regulation of ion influx in response to light stimulation | impair the normal function of these channels | abnormalities in the phototransduction process, reduced sensitivity to light, decreased visual acuity, and progressive vision loss. Dysfunctional CNG channels can lead to cellular stress, oxidative damage |

| Retinal Pigment Epithelium-Specific 65 kDa Protein (RPE65) | component of the vitamin A visual cycle of the retina which supplies the 11-cis retinal chromophore of the photoreceptors opsin visual pigments | loss or dysfunction of the RPE65 protein, disrupting the visual cycle and impairing the regeneration of 11-cis-retinal | progressive loss of photoreceptors reduced sensitivity to light, decreased visual acuity |

| Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator (RPGR) | predominantly localized in the connecting cilium and outer segment of photoreceptor cells in the retina, plays critical roles in the phototransduction cascade | impair the normal function | impaired ciliary transport, altered protein-protein interactions, or disrupted signaling pathways, leading to photoreceptor cell death and vision loss |

| Cone-Rod Homeobox Protein (CRX) | photoreceptor-specific transcription factor which plays a role in the differentiation of photoreceptor cells. This homeodomain protein is necessary for the maintenance of normal cone and rod function. | disrupt the normal function | impaired development and function of photoreceptor cells associated with degeneration of cones and rods |

|

Usher Syndrome Genes (MYO7A, USH1C, USH2A, GPR98, CLRN1) |

MYO7A encodes the protein myosin VIIA, involved in the development and maintenance of photoreceptor cells | impair the normal function | impaired development and function of photoreceptor cells associated with degeneration |

| USH1C encodes a scaffold protein involved in the organization of hair cell stereocilia and the synaptic connections in the retina | |||

| USH2A encodes a protein that contains laminin EGF motifs involved in the maintenance of the structure and function of the photoreceptor cells (maintenance of periciliary membrane complex) | |||

| GPR98 encodes the protein ADGRV1 involved into the development of photoreceptors ( maintenance of periciliary membrane complex) | |||

| CLRN1 encodes the protein Clarin 1 which play important role in development and homeostasis of the photoreceptor cells ( regulatory element for the synapses within the retina)an |

| ID | NAME | PHASE | AIM | METHODS |

| NCT02320812 | A Prospective, Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm Study of the Safety and Tolerability of a Single, Intravitreal Injection of Human Retinal Progenitor Cells (jCell) in Adult Subjects With Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) | 1/2 | Test the safety,tolerability and efficacy (impact on visual status) of the administration of a single dose of jCell | single intravitreal injection of 0.5 - 3.0x106 human retinal progenitor cells (hRPC- jCell) |

| NCT04925687 | Phase 1 Study of Intravitreal Autologous CD34+ Stem Cell Therapy for Retinitis Pigmentosa (BMSCRP1) | 1 | Determine safety and feasibility of injection of autologous CD34+ stem cells harvested from bone marrow. | Intravitreal injection of autologous CD34+ cells harvested from bone marrow under GMP conditions |

| NCT04763369 | Investigation of Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety of UMSCs for the Management of Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) | 1/2 | Investigate the safety and therapeutic efficacy of UMSC (umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells) injection employing two different routes (sub-tenon injection versus suprachoroidal injection) | sub-tenon and suprachoroidal injection of UMSCs |

| NCT05909488 | Role of UC-MSC and CM to Inhibit Vision Loss in Retinitis Pigmentosa Phase I/II | 2/3 | Investigate the safety and therapeutic efficacy of peribulbar injection of Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell (UC-MSC) with Conditioned Medium (CM) | Peribulbar injection of 1.5- 5 x 106UC-MSC + CM |

| NCT03944239 | Safety and Efficacy of Subretinal Transplantation of Clinical Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Retinal Pigment Epitheliums in Treatment of Retinitis Pigmentosa | 1/2 | Test the safety and therapeutic efficacy of clinical level human embryonic stem cells derived retinal pigment epithelium transplantation | Subretinal transplantation of clinical human embryonic stem cell derived retinal pigment epitheliums |

| NCT01531348 | Intravitreal Injection of MSCs in Retinitis Pigmentosa | 1 | Determine feasibility and safety of Adult Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BM-MSC) by Intravitreal Injection | Intravitreal Injection of 1x 106 BM-MSC in balanced salt solution |

| NCT03073733 | Safety and Efficacy of Intravitreal Injection of Human Retinal Progenitor Cells in Adults With Retinitis Pigmentosa | 2 | Evaluation of safety and efficacy of intravitreal injection of human retinal progenitor (hRPC) | Intravitreal injection of 3.0-6.0x 106 of human retinal progenitor cells (hRPC) suspended in clinical grade medium |

| NCT04284293 | CNS10-NPC for the Treatment of RP | 1 | Assess the safety and tolerability of two escalating doses of clinical grade human fetal cortical-derived neural progenitor cells (CNS10-NPC).Determine if CNS10-NPC can engraft and survive long-term in the retina of transiently immunosuppressed subjects.Obtain evidence that subretinal injection of CNS10-NPC can favorably impact the progression of vision loss in subjects with moderate RP. | human neural progenitor cells (CNS10-NPC) sub retinal space implantation |

| NCT02709876 | Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived CD34+, CD133+, and CD271+ Stem Cell Transplantation for Retinitis Pigmentosa | 1/2 | Assess the safety and efficacy of purified adult autologous bone marrow derived CD34+, CD133+, and CD271+ stem cells through a 48 month follow-up period. The combination of these three cell types was based on their diverse potentialities to differentiate into specific functional cell types to regenerate damaged retinal tissue | Intravitreal injection of Bone marrow-derived CD34+, CD133+, CD271+ stem cells in 1.0 ml normal saline |

| NCT03963154 | Interventional Study of Implantation of hESC-derived RPE in Patients With RP Due to Monogenic Mutation | 1/2 | Study the safety, tolerability and preliminary efficacy of implantation into one eye of hESC-derived RPE (Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE)) | Implantation into one eye of hESC-derived RPE (Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE)) |

| NCT03566147 | Treatment of RP and LCA by Primary RPE Transplantation | Early 1 | Study the Safety and Preliminary Efficacy of Human primary Retinal Pigment Epithelial (HuRPE) Cells Subretinal Transplantation | subretinal space transplantation of 0.3- 1 x106 HuRPE cells through a standard surgical approach. |

| NCT03772938 | Stem Cells Therapy in Degenerative Diseases of the Retina | 1 | Investigation of the safety and efficacy of intravitreal injection of autologous bone marrow-isolated stem/progenitor cells with different selected phenotypes. Especially, this clinical trial is designated to test the therapeutic (pro-regenerative and neuro-protective) functions of different stem/progenitor cell populations able to secrete bioactive neurotrophic factors. | intravitreal injection of Human autologous bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cell |

| NCT05147701 | Safety of Cultured Allogeneic Adult Umbilical Cord Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Eye Diseases | 1 | Study the safety and efficacy of intravenous and sub-tenon delivery of cultured allogeneic adult umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs) | intravenous and sub-tenon injection of 1 x106 allogeneic adult umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).