Submitted:

31 August 2023

Posted:

01 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

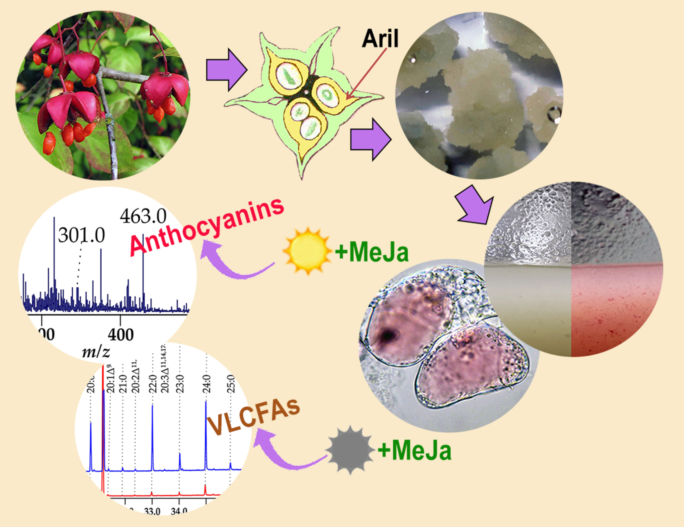

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

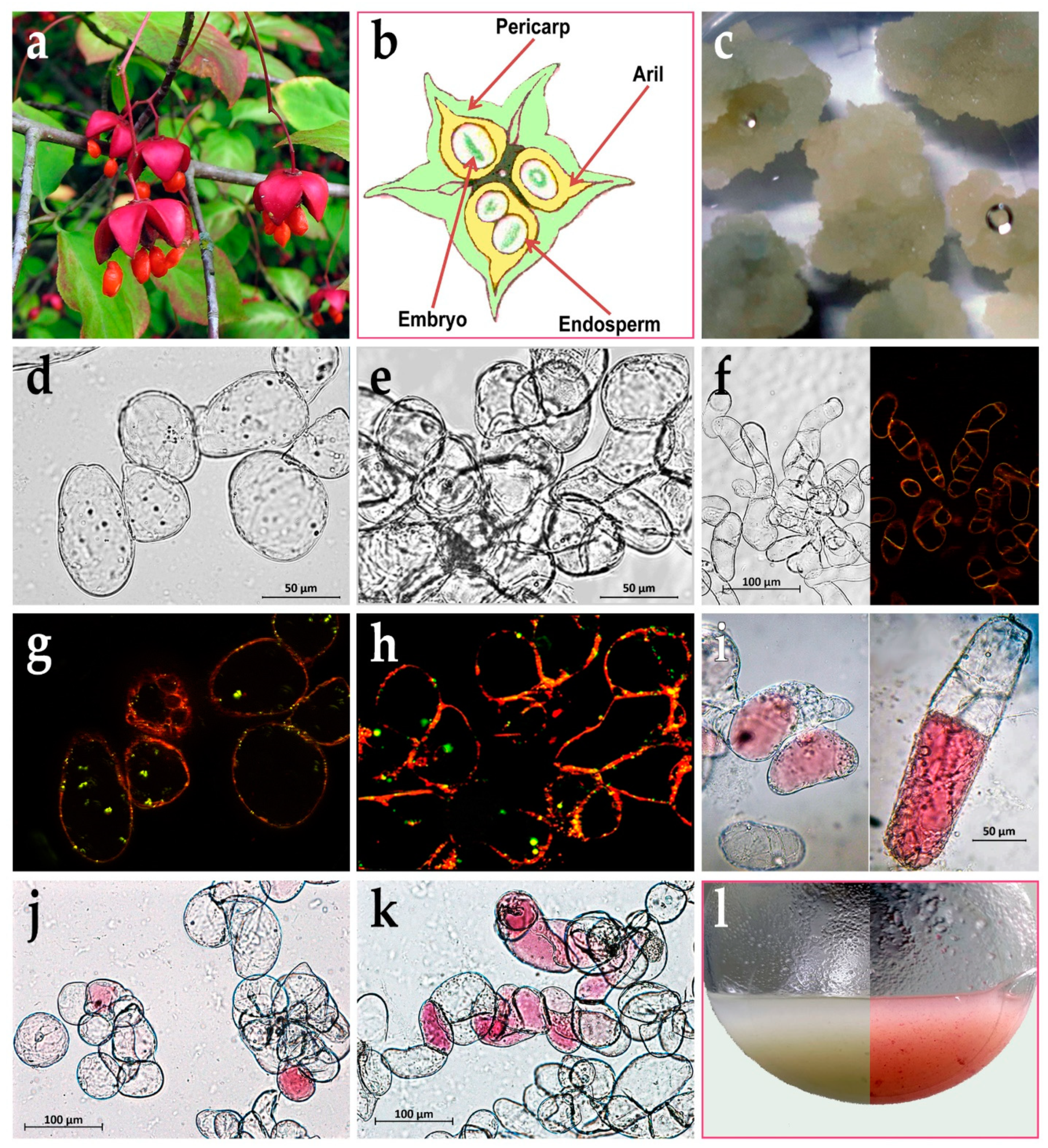

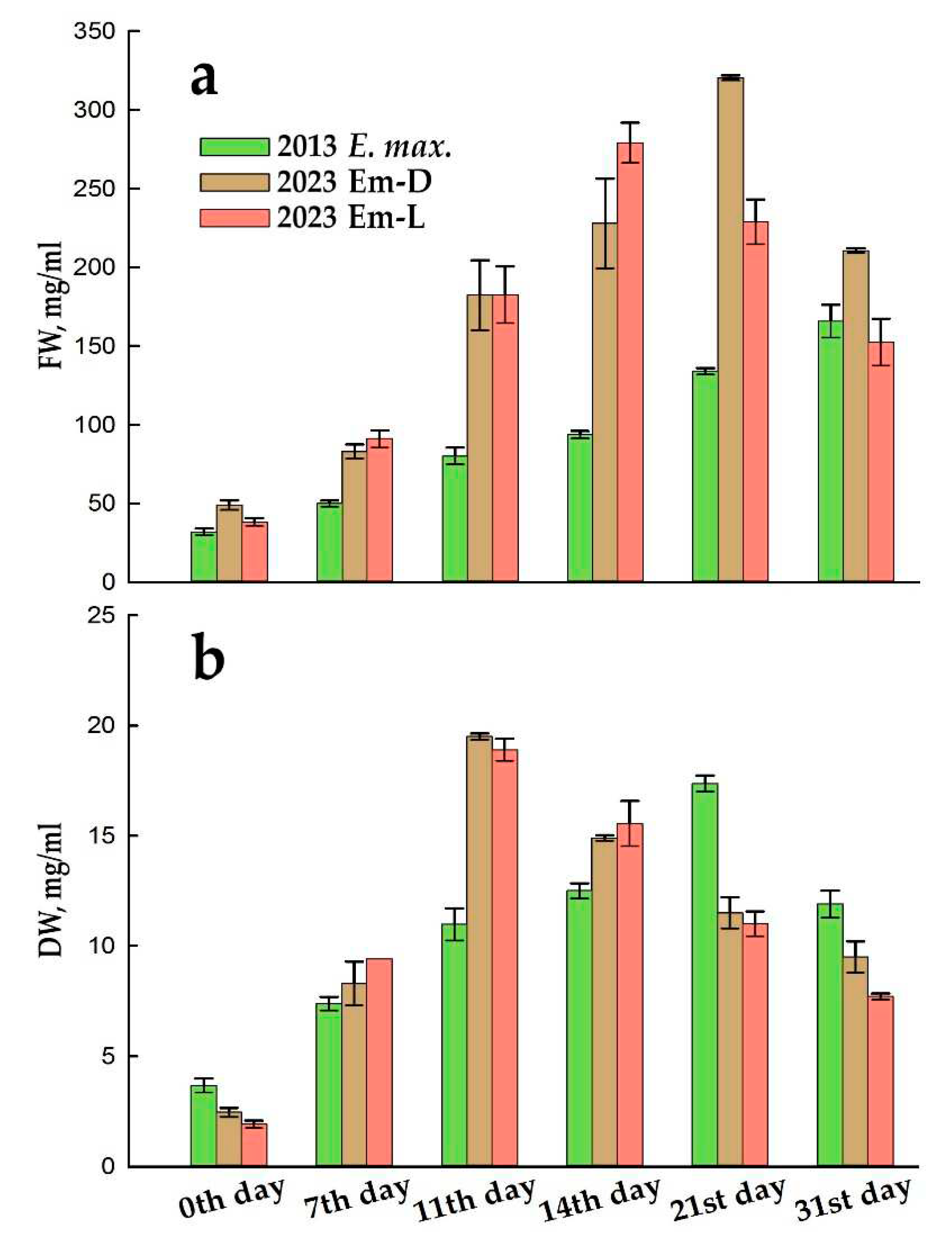

2.1. Callus Induction, Suspension Cell Cultures Derivation and its Growth Characteristics

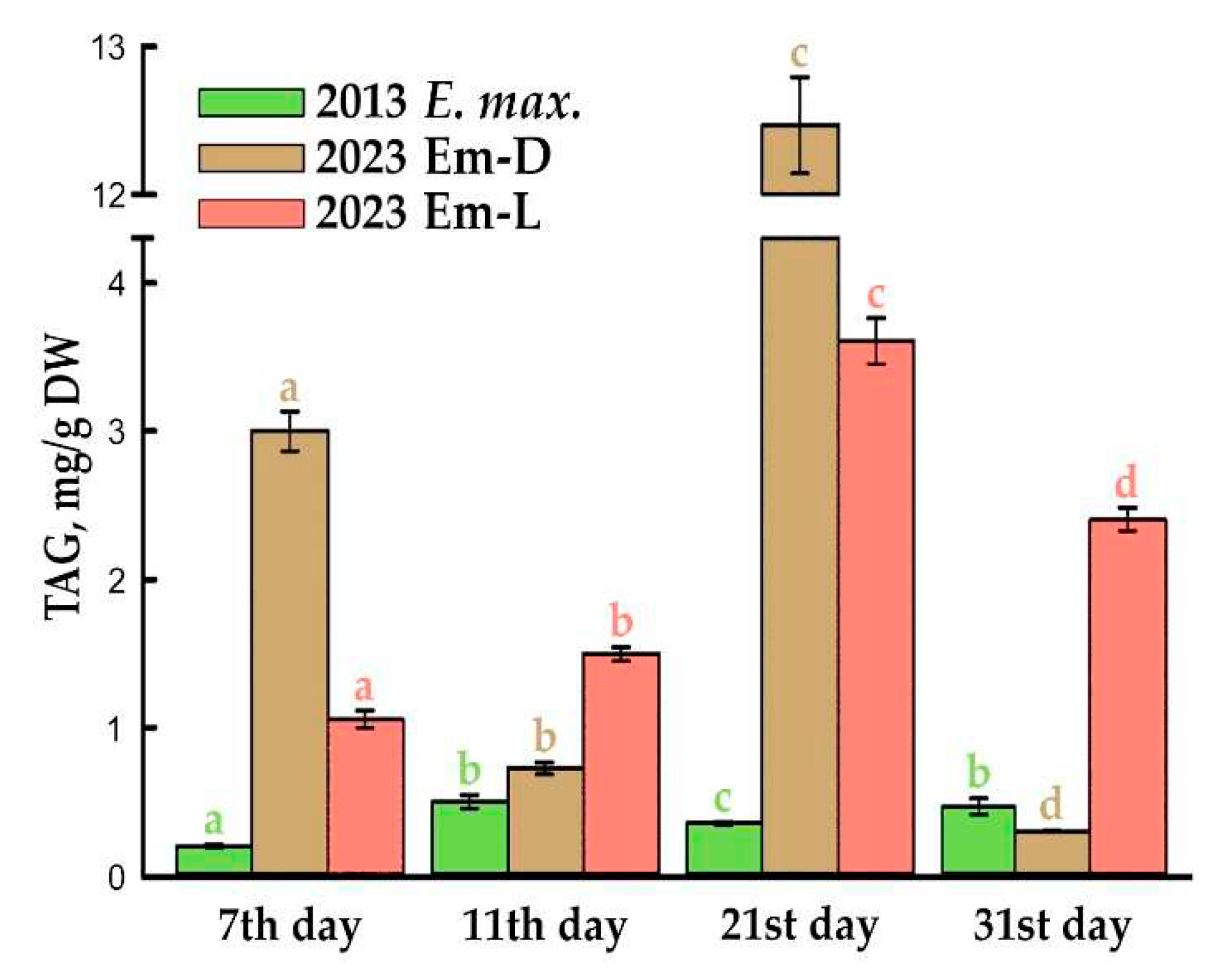

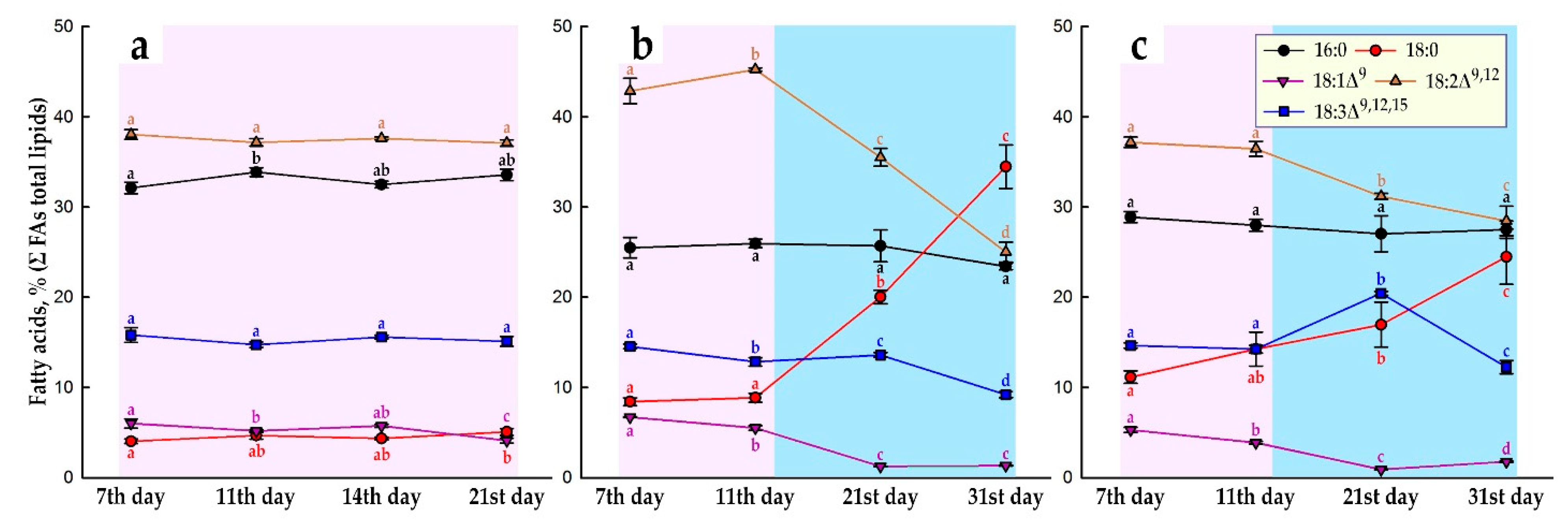

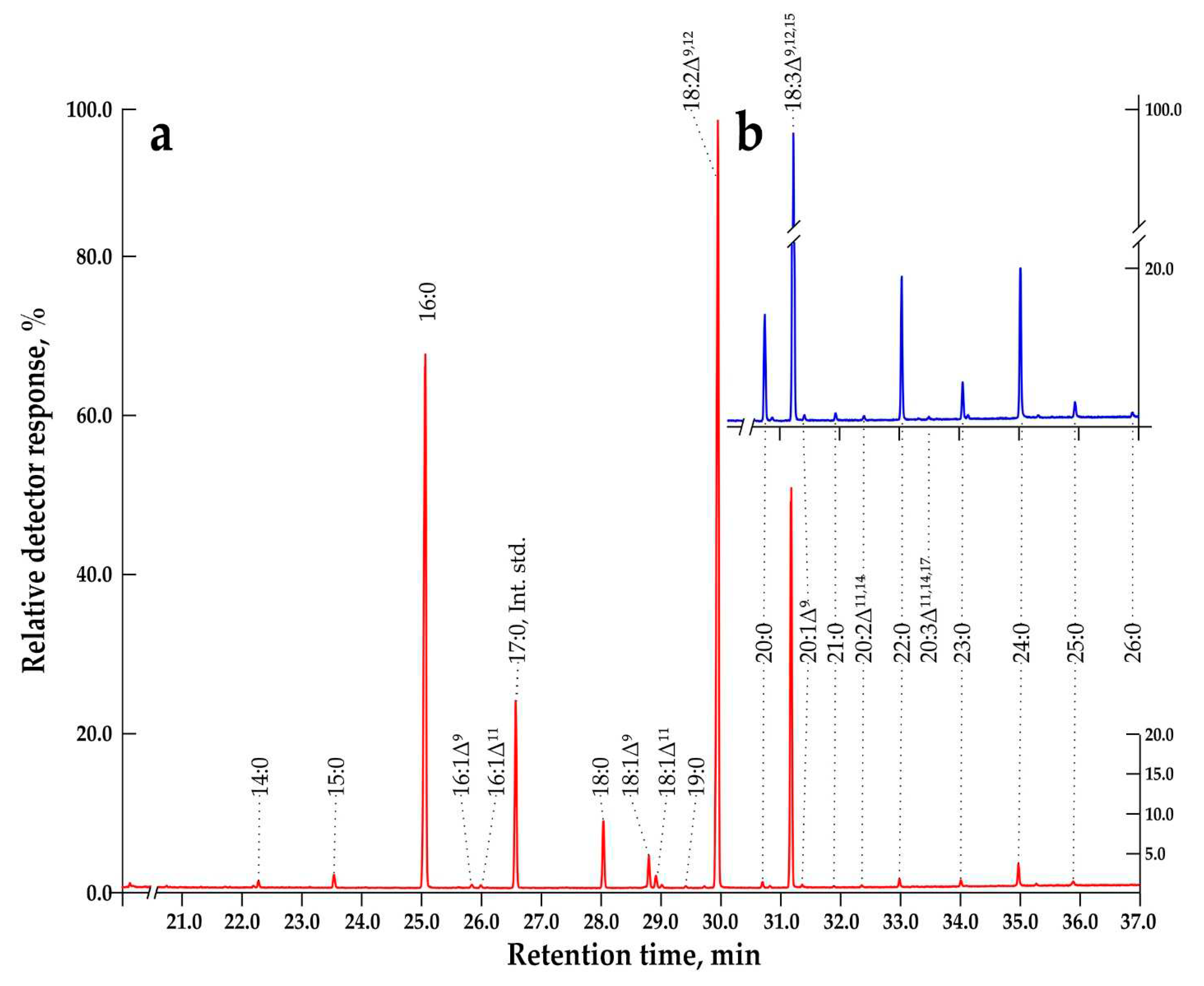

2.2. TAG Content and Fatty Acid Composition of Total Lipids during Subcultivation of E. max. Suspension Cell Cultures

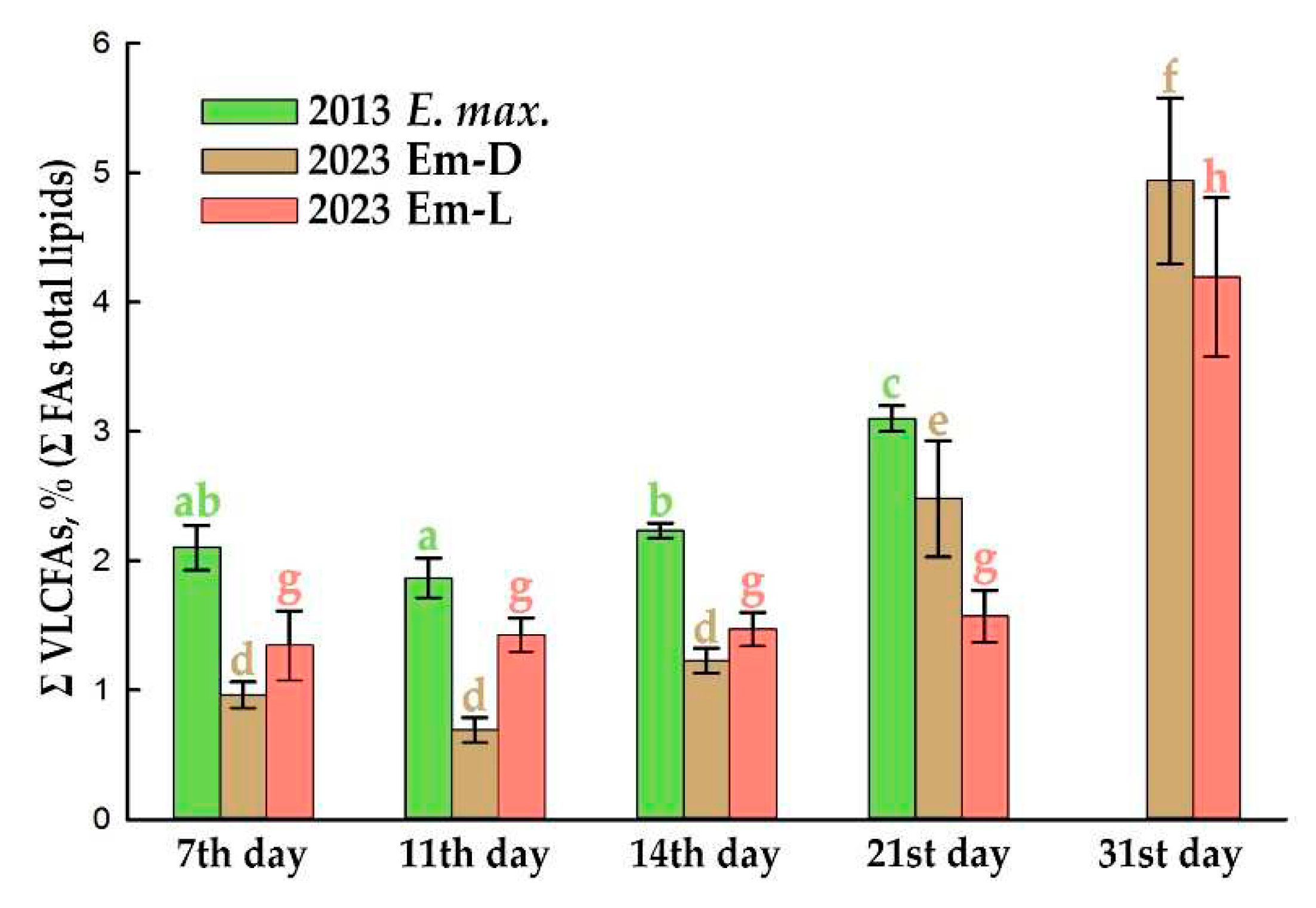

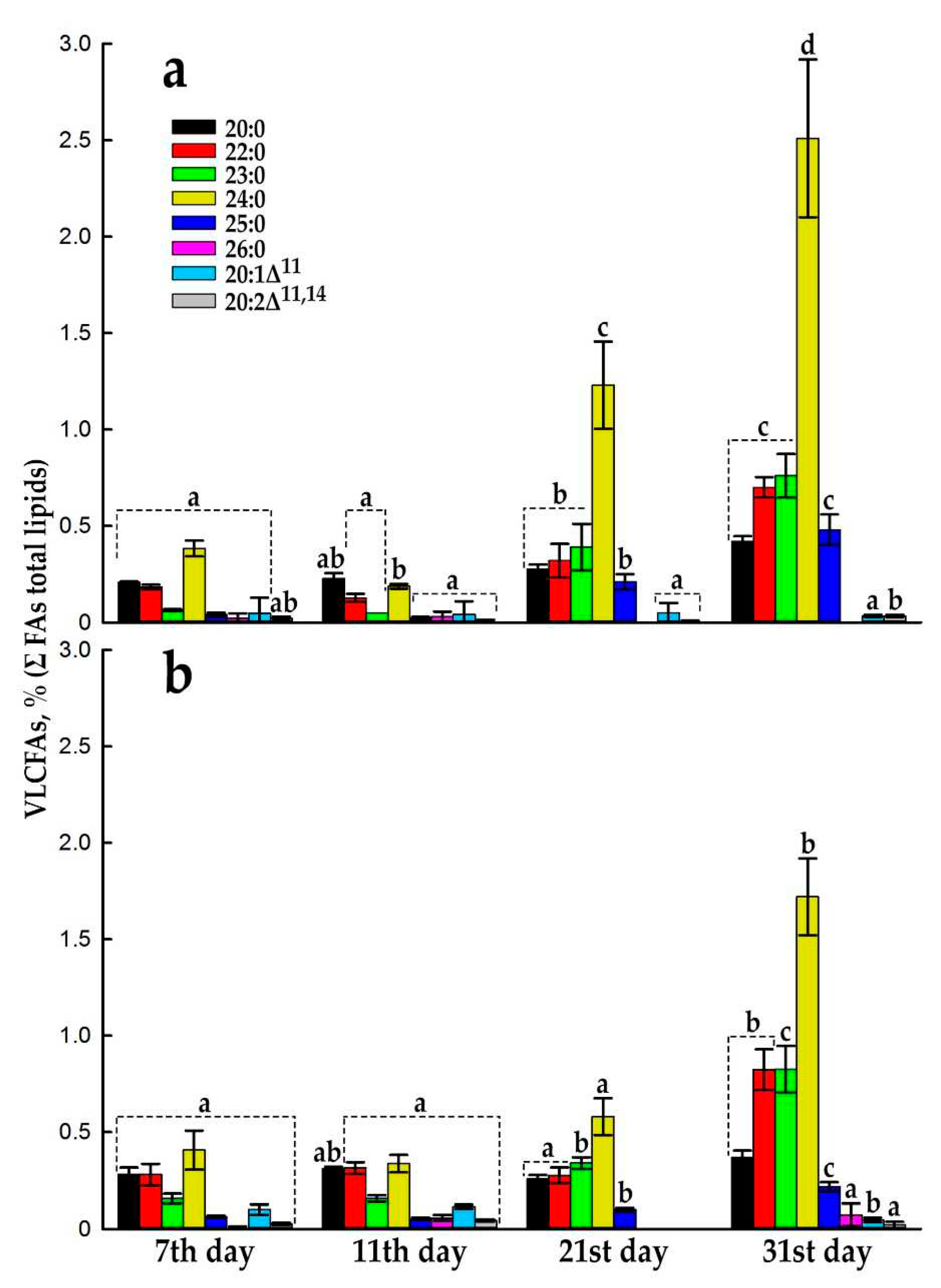

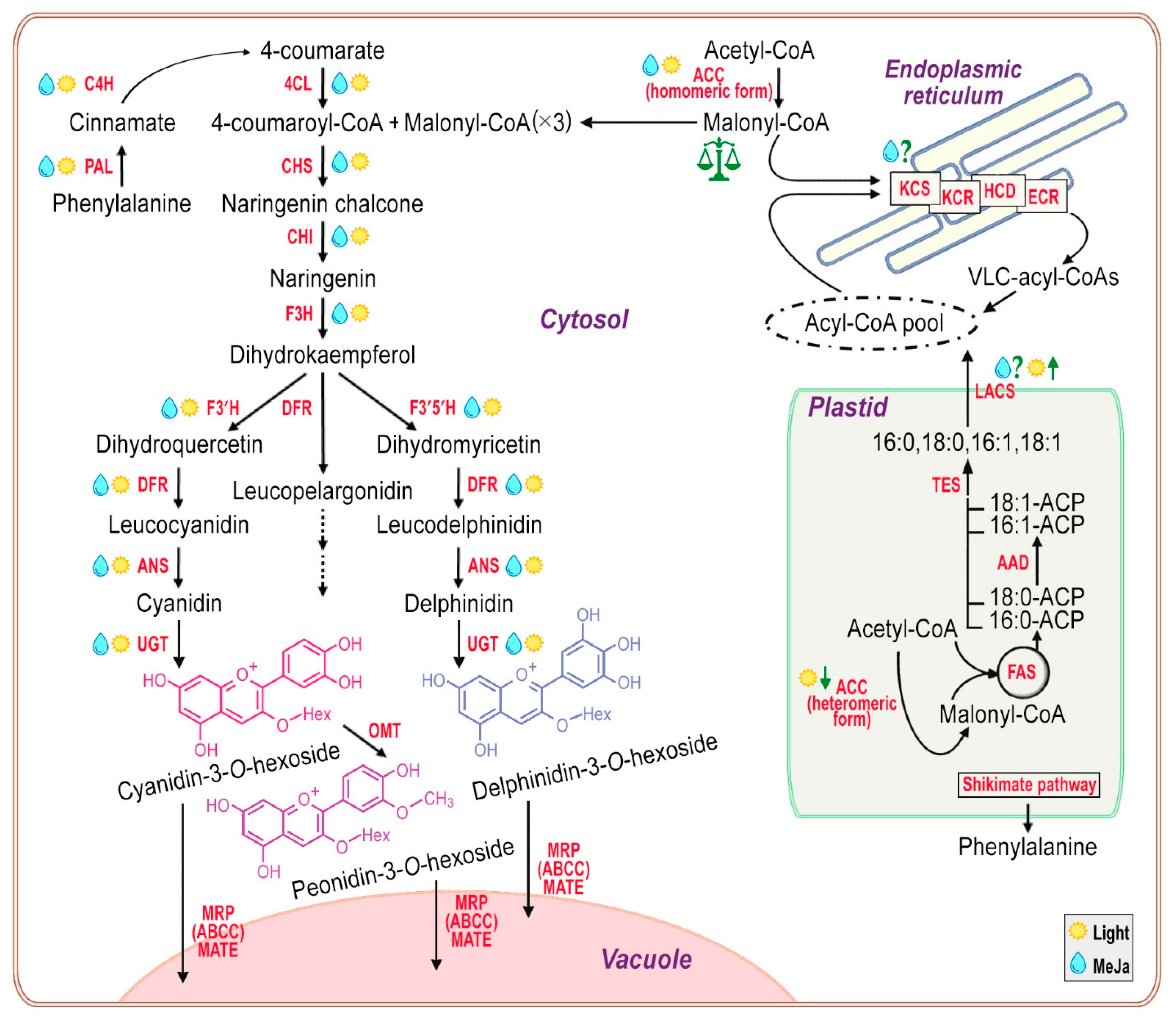

2.3. Very-Long-Chain FAs Proportion and Composition during Subcultivation of E. max. Suspension Cell Cultures

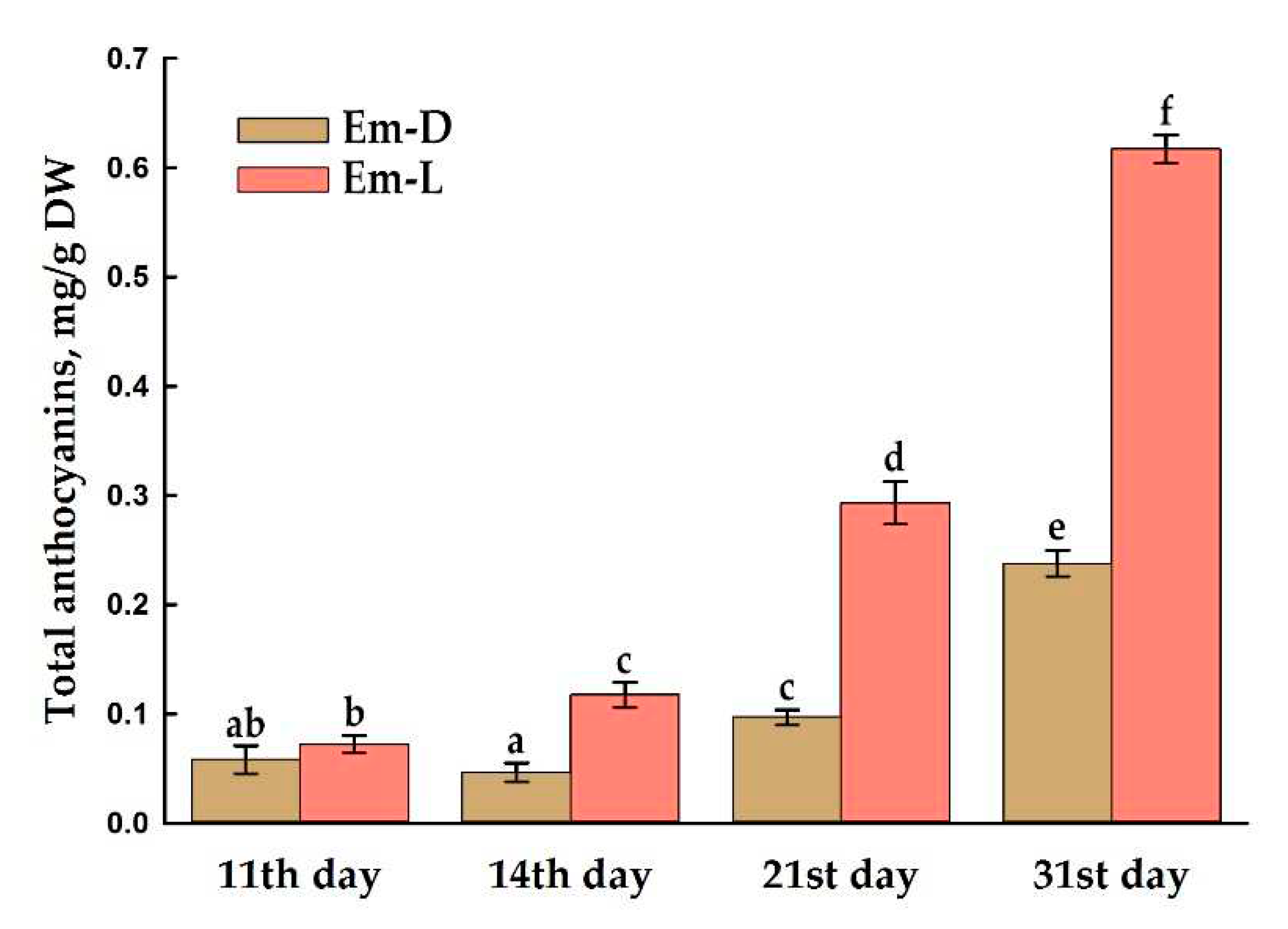

2.4. Anthocyanin Production in Em-D and Em-L Cell Cultures during Subcultivation

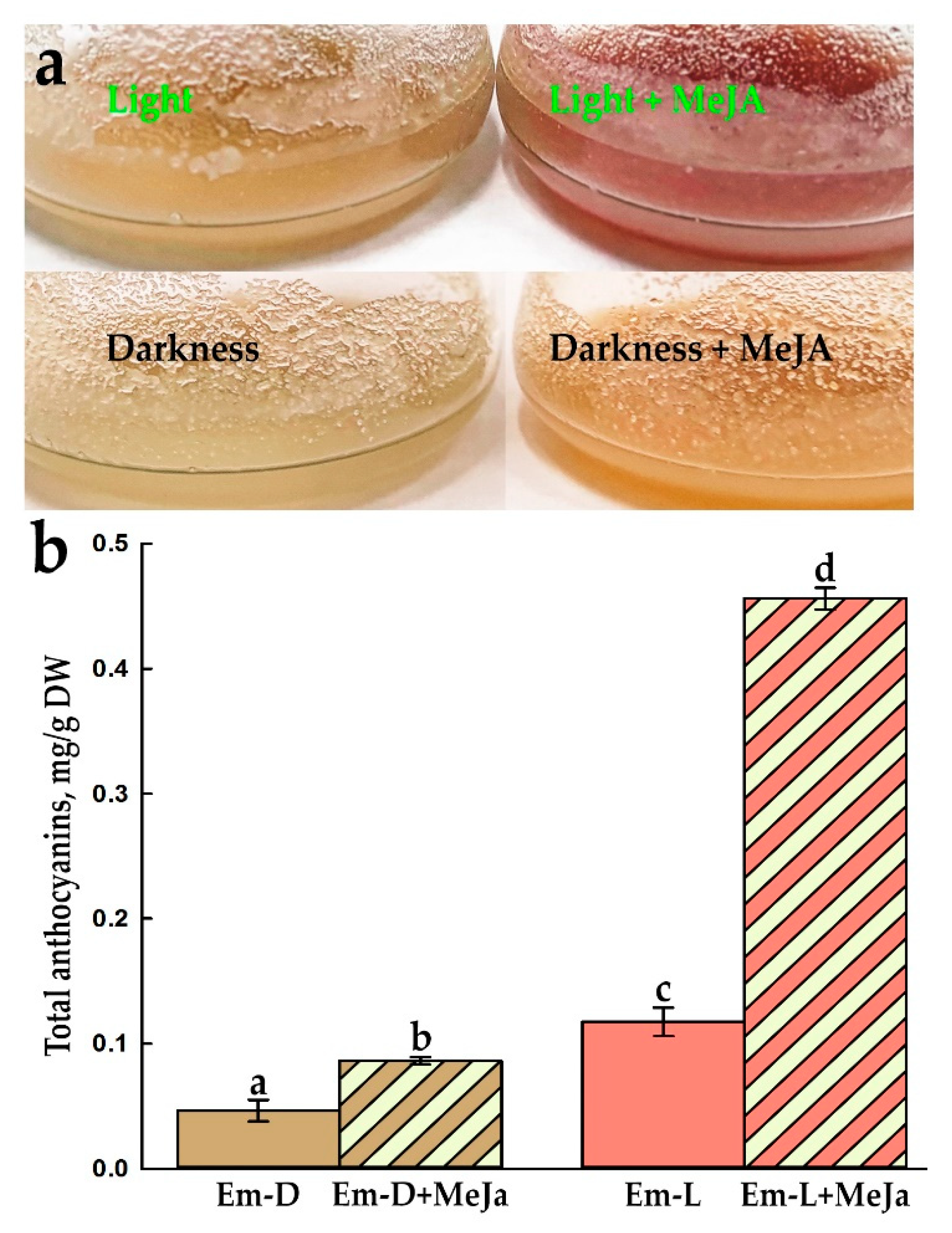

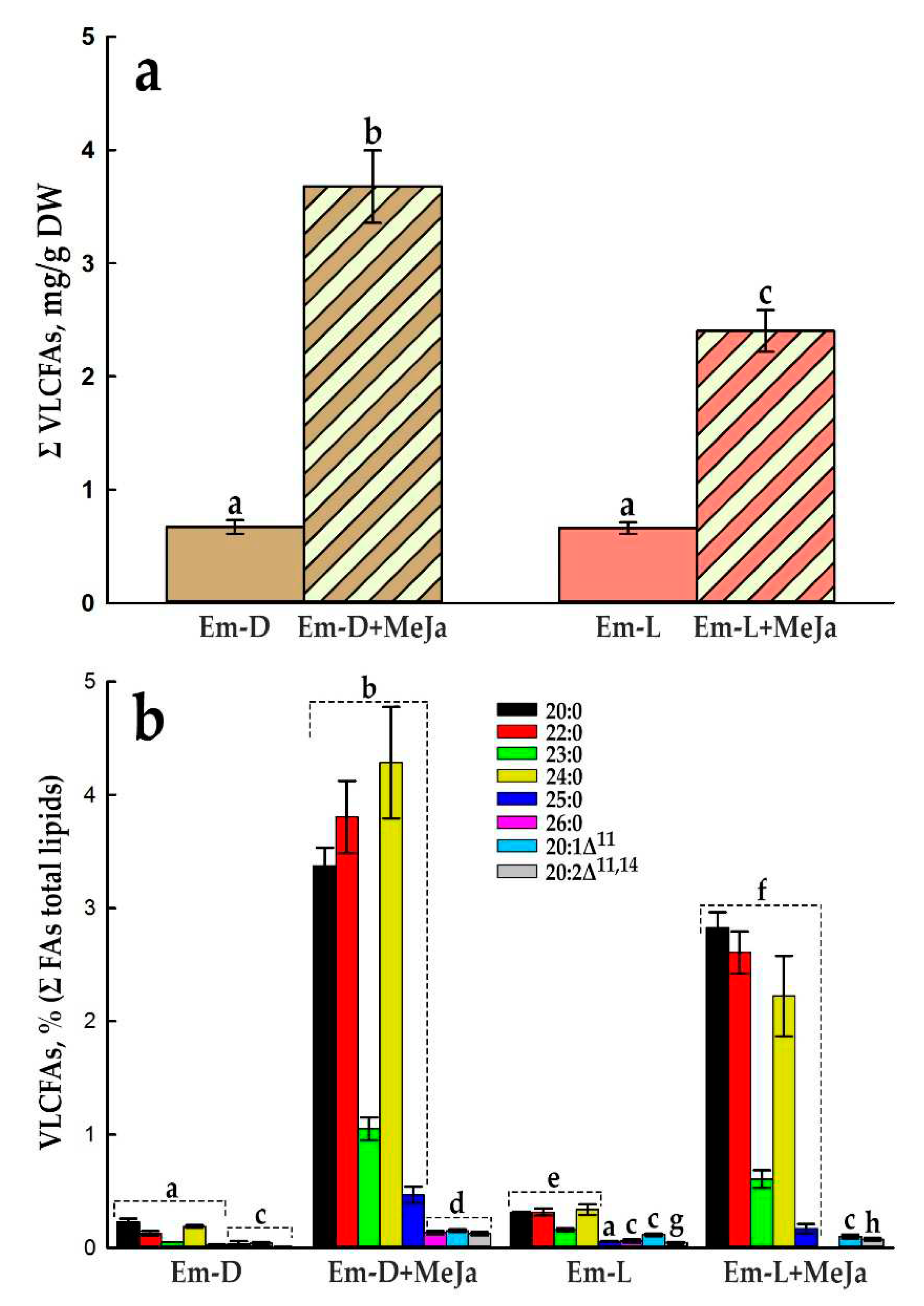

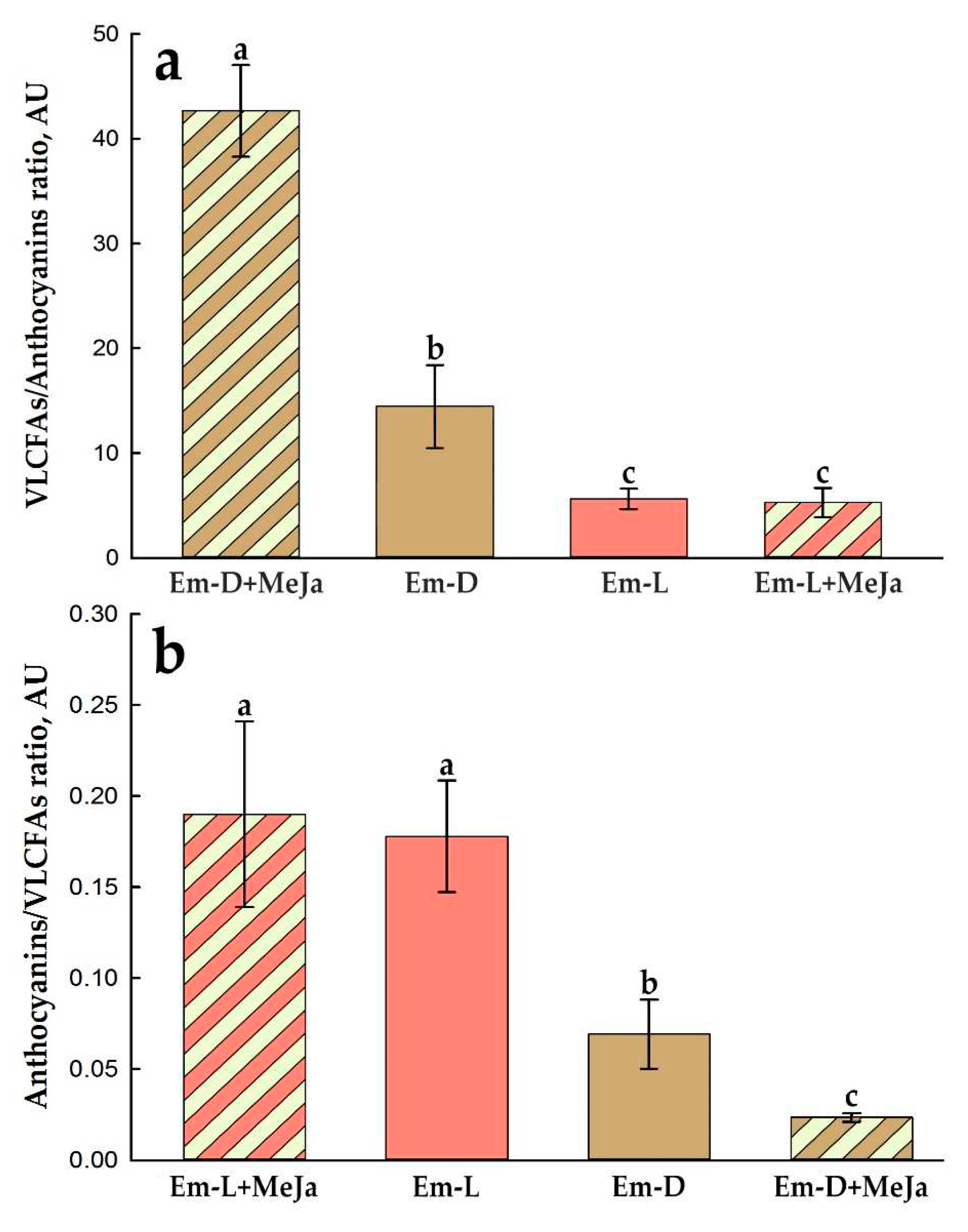

2.5. Influence of Methyl Jasmonate on the Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins and VLCFAs in the Em-D and Em-L Cell Cultures

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Consumables

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Callus Induction

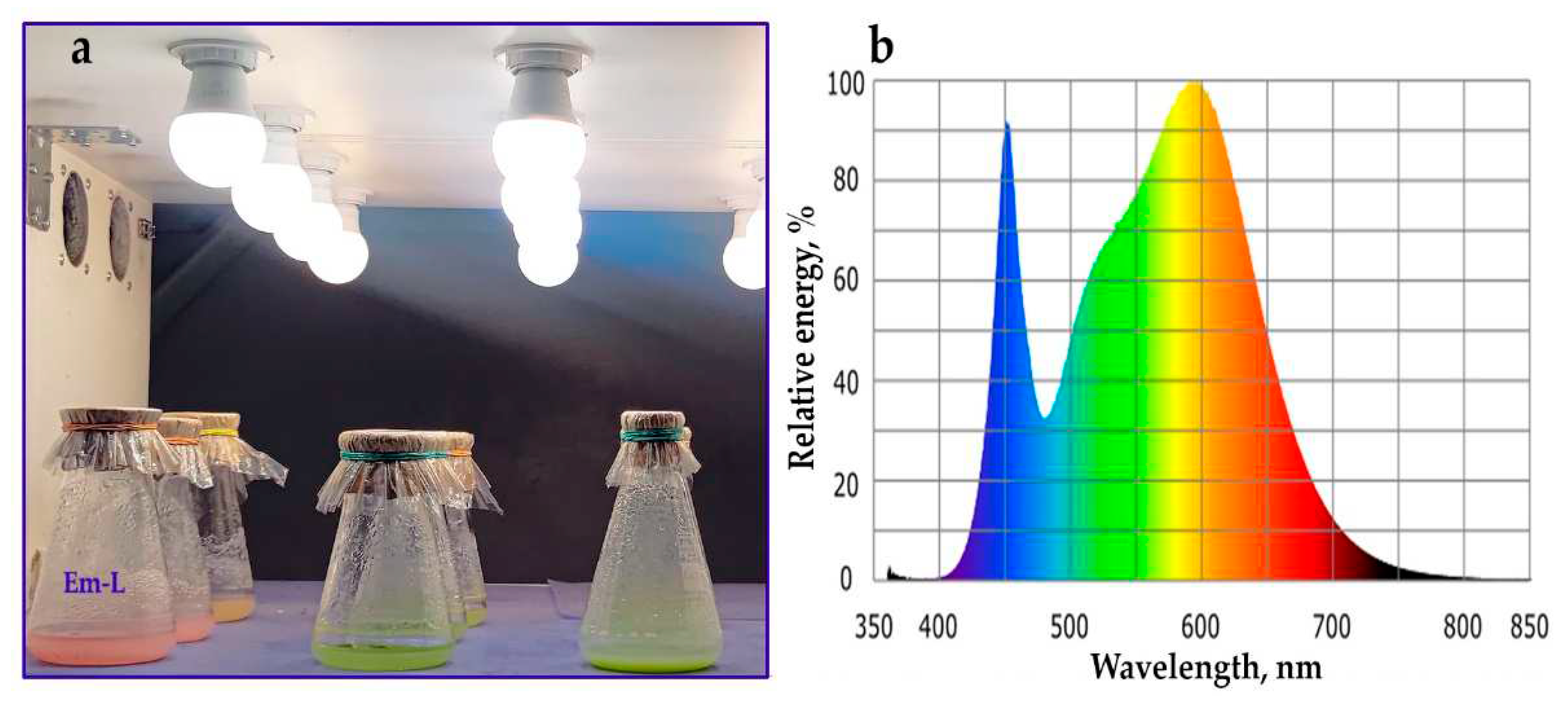

3.4. Derivation of Suspension Cell Cultures

3.5. Light Microscopy and Photography

3.6. Determination of Growth Characteristics and Sampling

3.7. Treatment of Cell Suspension Cultures with Methyl Jasmonate

3.8. Extraction of Total Anthocyanins and their Quantification by pH-Differential Spectrophotometrical Method

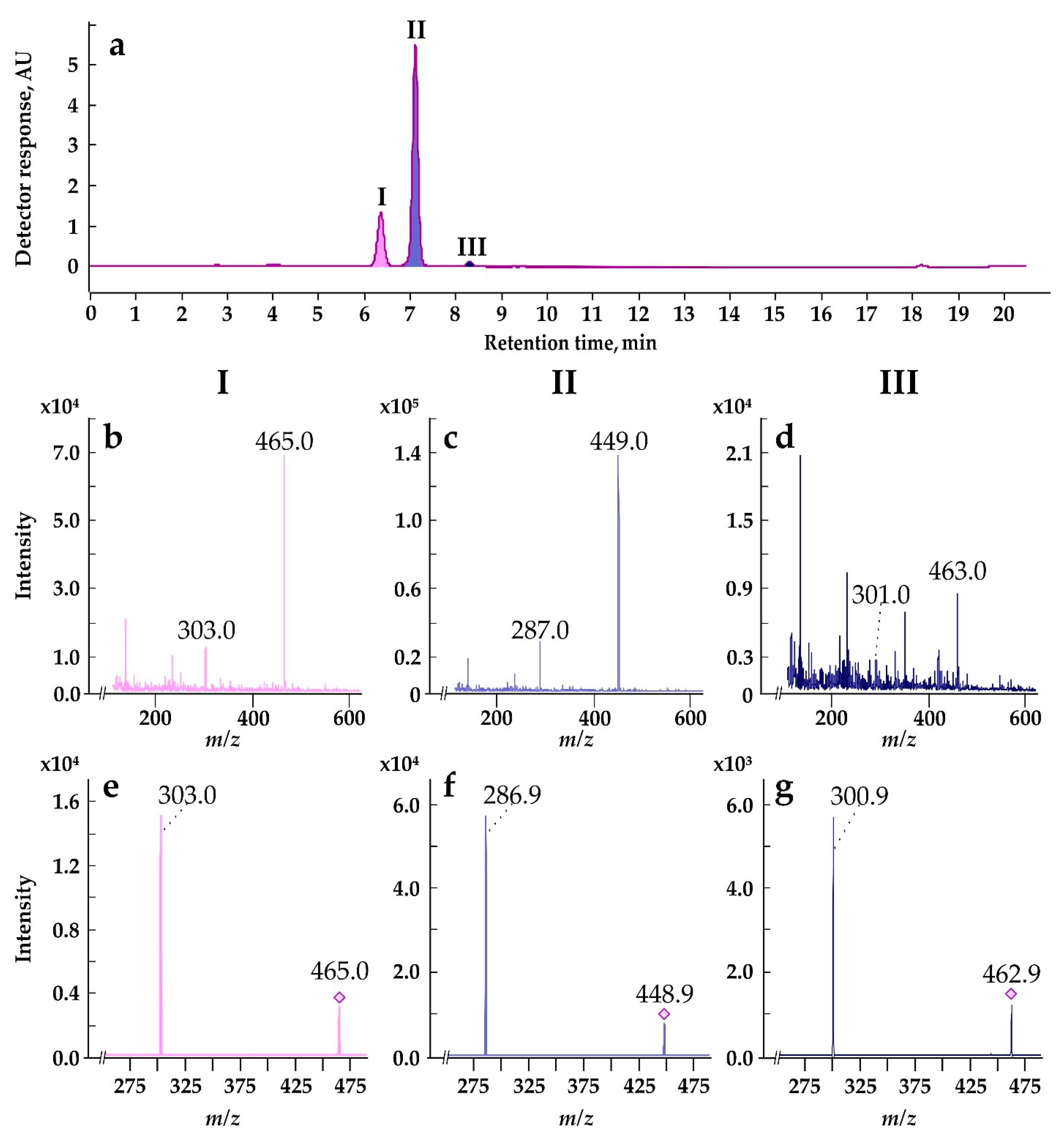

3.9. Anthocyanin Identification by HPLC-DAD and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS

3.10. Qualitative and Quantitative Composition of Fatty Acids in the Total Lipids

3.11. Quantification of Triacylglycerols

3.12. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Mabberley, D.J. Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of Plants, Their Classification and Uses; 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 2017; ISBN 9781316335581. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.S. A Revision of Euonymus (Celastraceae). Thaiszia J. Bot. 2001, 11, 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-X.; Qin, J.-J.; Chang, R.-J.; Zeng, Q.; Cheng, X.-R.; Zhang, F.; Jin, H.-Z.; Zhang, W.-D. Chemical Constituents of Plants from the Genus Euonymus. Chem. Biodivers. 2012, 9, 1055–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarenga, N.; Ferro, E.A. Bioactive Triterpenes and Related Compounds from Celastraceae. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2006, 33, 239–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, P.; Shrestha, R.; Lim, J.; Thapa Magar, T.B.; Kim, H.-H.; Kim, Y.-W. Euonymus Alatus Twig Extract Protects against Scopolamine-Induced Changes in Brain and Brain-Derived Cells via Cholinergic and BDNF Pathways. Nutrients 2022, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantry, M.A.; Khuroo, M.A.; Shawl, A.S.; Najar, M.H.; Khan, I.A. Dihydro-β-Agarofuran Sesquiterpene Pyridine Alkaloids from the Seeds of Euonymus Hamiltonianus. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2016, 20, S323–S327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, J.; Li, C.-J.; Yang, J.-Z.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.-G.; Zhang, D.-M. Bioactive Isopimarane Diterpenoids from the Stems of Euonymus Oblongifolius. Phytochemistry 2017, 135, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.; Baek, S.C.; Jo, M.S.; Kang, K.S.; Kim, K.H. (3β,16α)-3,16-Dihydroxypregn-5-En-20-One from the Twigs of Euonymus Alatus (Thunb.) Sieb. Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects in LPS-Stimulated RAW-264.7 Macrophages. Molecules 2019, 24, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, R.A.; Trusov, N.A.; Zhukov, A.V.; Pchelkin, V.P.; Vereshchagin, A.G.; Tsydendambaev, V.D. Accumulation of Neutral Acylglycerols during the Formation of Morphologo-Anatomical Structure of Euonymus Fruits. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 60, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, R.A.; Zhukov, A.V.; Pchelkin, V.P.; Vereshchagin, A.G.; Tsydendambaev, V.D. Content and Fatty Acid Composition of Neutral Acylglycerols in Euonymus Fruits. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blehová, A.; Murín, M.; Nemeček, P.; Gajdoš, P.; Čertík, M.; Kraic, J.; Matušíková, I. Alterations in Allocation and Composition of Lipid Classes in Euonymus Fruits and Seeds. Protoplasma 2021, 258, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusov, N.A. Arils of Dried Fruits and Their Relationship with Dissemination. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2021, 14, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, A.; Manayi, A.; Rezakazemi, M.; Eftekhari, M.; Khanavi, M.; Akbarzadeh, T.; Saeedi, M. Phytochemical Analysis and Anticholinesterase Activity of Aril of Myristica Fragrans Houtt. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokkumar, K.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Murugan, M.; Dhanya, M.K.; Pandian, A. Nutmeg (Myristica Fragrans Houtt.) Essential Oil: A Review on Its Composition, Biological, and Pharmacological Activities. Phyther. Res. 2022, 36, 2839–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubola, J.; Siriamornpun, S. Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Activity of Different Fruit Fractions (Peel, Pulp, Aril and Seed) of Thai Gac (Momordica Cochinchinensis Spreng). Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitraş, D.-A.; Bunea, A.; Vodnar, D.C.; Hanganu, D.; Pall, E.; Cenariu, M.; Gal, A.F.; Andrei, S. Phytochemical Characterization of Taxus Baccata L. Aril with Emphasis on Evaluation of the Antiproliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Activity of Rhodoxanthin. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquaert, E.; Van Damme, E.J.M. Promiscuity of the Euonymus Carbohydrate-Binding Domain. Biomolecules 2012, 2, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.R.; Dornelas, M.C.; Martinelli, A.P. Perspectives for a Framework to Understand Aril Initiation and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jopling, C.; Boue, S.; Belmonte, J.C.I. Dedifferentiation, Transdifferentiation and Reprogramming: Three Routes to Regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, R.U.; Hildebrandt, A.C. Medium and Techniques for Induction and Growth of Monocotyledonous and Dicotyledonous Plant Cell Cultures. Can. J. Bot. 1972, 50, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, G.V.; Mur, L.A.J.; Nosov, A. V.; Fomenkov, A.A.; Mironov, K.S.; Mamaeva, A.S.; Shilov, E.S.; Rakitin, V.Y.; Hall, M.A. Nitric Oxide Has a Concentration-Dependent Effect on the Cell Cycle Acting via EIN2 in Arabidopsis Thaliana Cultured Cells. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosov, A.V.; Titova, M. V.; Fomenkov, A.A.; Kochkin, D. V.; Galishev, B.A.; Sidorov, R.A.; Medentsova, A.A.; Kotenkova, E.A.; Popova, E. V.; Nosov, A.M. Callus and Suspension Cell Cultures of Sutherlandia Frutescens and Preliminary Screening of Their Phytochemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2023, 45, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, T.; Nemoto, Y.; Hasezawa, S. Tobacco BY-2 Cell Line as the “HeLa” Cell in the Cell Biology of Higher Plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992, 132, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenkov, A.A.; Nosov, A.V.; Rakitin, V.Y.; Sukhanova, E.S.; Mamaeva, A.S.; Sobol’kova, G.I.; Nosov, A.M.; Novikova, G. V. Ethylene in the Proliferation of Cultured Plant Cells: Regulating or Just Going Along? Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 62, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosov, A.M. Application of Cell Technologies for Production of Plant-Derived Bioactive Substances of Plant Origin. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2012, 48, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titova, M.V.; Popova, E.V.; Konstantinova, S.V.; Kochkin, D.V.; Ivanov, I.M.; Klyushin, A.G.; Titova, E.G.; Nebera, E.A.; Vasilevskaya, E.R.; Tolmacheva, G.S.; et al. Suspension Cell Culture of Dioscorea Deltoidea — A Renewable Source of Biomass and Furostanol Glycosides for Food and Pharmaceutical Industry. Agronomy 2021, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glagoleva, E.S.; Konstantinova, S.V.; Kochkin, D.V.; Ossipov, V.; Titova, M.V.; Popova, E.V.; Nosov, A.M.; Paek, K.-Y. Predominance of Oleanane-Type Ginsenoside R0 and Malonyl Esters of Protopanaxadiol-Type Ginsenosides in the 20-Year-Old Suspension Cell Culture of Panax Japonicus C.A. Meyer. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 177, 114417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochkin, D.V.; Demidova, E. V.; Globa, E.B.; Nosov, A.M. Profiling of Taxoid Compounds in Plant Cell Cultures of Different Species of Yew (Taxus Spp.). Molecules 2023, 28, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmrich, A.R.; Schraudolf, H. Fatty Acid Composition of Lipids from Differentiated Tissues and Cell Cultures of Euonymus Europaeus. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1980, 26, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, L.; Beranger-Novat, N.; Monin, J. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration in a Woody Species: The European Spindle Tree (Euonymus Europaeus L.). Plant Cell Rep. 1994, 13, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.-A.; Ku, S.S.; Jie, E.Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.-S.; Cho, H.S.; Jeong, W.-J.; Park, S.U.; Min, S.R.; Kim, S.W. Efficient Plant Regeneration from Embryogenic Cell Suspension Cultures of Euonymus Alatus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fett-Neto, A.G.; DiCosmo, F.; Reynolds, W.F.; Sakata, K. Cell Culture of Taxus as a Source of the Antineoplastic Drug Taxol and Related Taxanes. Nat. Biotechnol. 1992, 10, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklaszewska, M.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Inchana, P.; Zienkiewicz, A. Lipid Metabolism and Accumulation in Oilseed Crops. OCL 2021, 28, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N.; Taylor, D.C. Biosynthesis of Triacylglycerols in Plant Cell and Embryo Cultures Their Significance in the Breeding of Oil Plants. In Progress in Plant Cellular and Molecular Biology. Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture; Nijkamp, H.J.J., Van Der Plas, L.H.W., Van Aartrijk, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1990; pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Radetzky, R.; Langheinrich, U. Induction of Accumulation and Degradation of the 18.4-KDa Oleosin in a Triacylglycerol-Storing Cell Culture of Anise (Pimpinella Anisum L.). Planta 1994, 194, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselake, R.J.; Byers, S.D.; Davoren, J.M.; Laroche, A.; Hodges, D.M.; Pomeroy, M.K.; Furukawa-Stoffer, T.L. Triacylglycerol Biosynthesis and Gene Expression in Microspore-Derived Cell Suspension Cultures of Oilseed Rape. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchev, A.; Georgiev, M. Plant Cell Bioprocesses. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Larroche, C., Sanromán, M.Á., Du, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2017; pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Leeggangers, H.A.C.F.; Rodriguez-Granados, N.Y.; Macias-Honti, M.G.; Sasidharan, R. A Helping Hand When Drowning: The Versatile Role of Ethylene in Root Flooding Resilience. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 213, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, H.; Castro, P.H.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Lino-Neto, T.; Tavares, R.M. Impact of Carbon and Phosphate Starvation on Growth and Programmed Cell Death of Maritime Pine Suspension Cells. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Plant 2014, 50, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, M.; Cerana, R. Plant Cell Cultures as a Tool to Study Programmed Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebeille, F.; Bligny, R.; Douce, R. Role de l’oxygene et de La Temperature Sur La Composition En Acides Gras Des Cellules Isolees d’Erable (Acer Pseudoplatanus L.). Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Lipids Lipid Metab. 1980, 620, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.J.; Beevers, H. Fatty Acids of Rice Coleoptiles in Air and Anoxia. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkenberg, J.; Faist, H.; Saupe, S.; Lambertz, S.; Krischke, M.; Stingl, N.; Fekete, A.; Mueller, M.J.; Feussner, I.; Hedrich, R.; et al. Two Fatty Acid Desaturases, STEAROYL-ACYL CARRIER PROTEIN Δ 9 -DESATURASE6 and FATTY ACID DESATURASE3, Are Involved in Drought and Hypoxia Stress Signaling in Arabidopsis Crown Galls. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.-J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.-F.; Xiao, S. New Insights into the Role of Lipids in Plant Hypoxia Responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 81, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titova, M.V.; Kochkin, D. V.; Sobolkova, G.I.; Fomenkov, A.A.; Sidorov, R.A.; Nosov, A.M. Obtainment and Characterization of Alhagi Persarum Boiss. et Buhse Callus Cell Cultures That Produce Isoflavonoids. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjellström, H.; Yang, Z.; Allen, D.K.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Rapid Kinetic Labeling of Arabidopsis Cell Suspension Cultures: Implications for Models of Lipid Export from Plastids. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meï, C.; Michaud, M.; Cussac, M.; Albrieux, C.; Gros, V.; Maréchal, E.; Block, M.A.; Jouhet, J.; Rébeillé, F. Levels of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Correlate with Growth Rate in Plant Cell Cultures. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batsale, M.; Bahammou, D.; Fouillen, L.; Mongrand, S.; Joubès, J.; Domergue, F. Biosynthesis and Functions of Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acids in the Responses of Plants to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Cells 2021, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, A.; Popov, V. Synthesis of C20–38 Fatty Acids in Plant Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsale, M.; Alonso, M.; Pascal, S.; Thoraval, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Beaudoin, F.; Domergue, F.; Joubès, J. Tackling Functional Redundancy of Arabidopsis Fatty Acid Elongase Complexes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Huang, B.; Lu, X.; Sheteiwy, M.S.A.; Kuang, S.; Shao, H. Oil Crop Genetic Modification for Producing Added Value Lipids. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wu, R.; Ma, X.; Su, E. The Advancements and Prospects of Nervonic Acid Production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 12772–12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Rowland, O.; Kunst, L. Disruptions of the Arabidopsis Enoyl-CoA Reductase Gene Reveal an Essential Role for Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acid Synthesis in Cell Expansion during Plant Morphogenesis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobusawa, T.; Okushima, Y.; Nagata, N.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Umeda, M. Synthesis of Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acids in the Epidermis Controls Plant Organ Growth by Restricting Cell Proliferation. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, J.; Castillo, M.C.; Gayubas, B. The Hypoxia–Reoxygenation Stress in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5841–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, G.; Jia, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Wang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, X.; Li, W. Acyl Chain Length of Phosphatidylserine Is Correlated with Plant Lifespan. PLoS One 2014, 9, e103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breygina, M.; Voronkov, A.; Ivanova, T.; Babushkina, K. Fatty Acid Composition of Dry and Germinating Pollen of Gymnosperm and Angiosperm Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Singh, G.; Jeandet, P.; Pandey, A.; Giri, L.; Ramola, S.; Bhatt, I.D.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Georgiev, M.I.; Clément, C.; et al. Anthocyanins, Multi-Functional Natural Products of Industrial Relevance: Recent Biotechnological Advances. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, H. Anthocyanins in Plant Food: Current Status, Genetic Modification, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Wang, L. Anthocyanins: Modified New Technologies and Challenges. Foods 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFountain, A.M.; Yuan, Y. Repressors of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araguirang, G.E.; Richter, A.S. Activation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in High Light – What Is the Initial Signal? New Phytol. 2022, 236, 2037–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, R.-N.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, T.-C.; Lee, S.-K. Anatomical Observations of Anthocyanin Rich Cells in Apple Skins. HortScience 2006, 41, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Toyama-Kato, Y.; Kameda, K.; Kondo, T. Sepal Color Variation of Hydrangea Macrophylla and Vacuolar PH Measured with a Proton-Selective Microelectrode. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poobathy, R.; Zakaria, R.; Murugaiyah, V.; Subramaniam, S. Autofluorescence Study and Selected Cyanidin Quantification in the Jewel Orchids Anoectochilus Sp. and Ludisia Discolor. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0195642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.D.; Yeoman, M.M. Temporal and Spatial Heterogeneity in the Accumulation of Anthocyanins in Cell Cultures of Catharanthus Roseus (L.) G.Don. J. Exp. Bot. 1986, 37, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanaga, K.; Seki, M.; Furusaki, S. Quantitative Determination of Cultured Strawberry-Cell Heterogeneity by Image Analysis: Effects of Medium Modification on Anthocyanin Accumulation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2000, 5, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões-Gurgel, C.; Cordeiro, L.d.S.; de Castro, T.C.; Callado, C.H.; Albarello, N.; Mansur, E. Establishment of Anthocyanin-Producing Cell Suspension Cultures of Cleome Rosea Vahl Ex DC. (Capparaceae). Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. 2011, 106, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezek, M.; Allan, A.C.; Jones, J.J.; Geilfus, C. Why Do Plants Blush When They Are Hungry? New Phytol. 2023, 239, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saw, N.M.M.T.; Riedel, H.; Cai, Z.; Kütük, O.; Smetanska, I. Stimulation of Anthocyanin Synthesis in Grape (Vitis Vinifera) Cell Cultures by Pulsed Electric Fields and Ethephon. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 108, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Feng, S.; Chen, X. Synergistic Effects of Light and Temperature on Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Callus Cultures of Red-Fleshed Apple (Malus Sieversii f. Niedzwetzkyana). Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. 2016, 127, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avula, B.; Katragunta, K.; Osman, A.G.; Ali, Z.; John Adams, S.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Khan, I.A. Advances in the Chemistry, Analysis and Adulteration of Anthocyanin Rich-Berries and Fruits: 2000–2022. Molecules 2023, 28, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Seki, T.; Kinoshita, S.; Yoshida, T. Effect of Light Irradiation on Anthocyanin Production by Suspended Culture of Perilla Frutescens. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1991, 38, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikura, N. Anthocyanin Pattern in the Genera Ilex and Euonymus. Phytochemistry 1971, 10, 2513–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikura, N. A Further Survey of Anthocyanins and Other Phenolics in Ilex and Euonymus. Phytochemistry 1975, 14, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, M.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Plant Secondary Metabolites as Defenses, Regulators, and Primary Metabolites: The Blurred Functional Trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Hussain, I.; Niharika, K.; Yadav, V.; Bano, C.; Yadav, R.K.; Amist, N. Plant Secondary Metabolites Synthesis and Their Regulations under Biotic and Abiotic Constraints. J. Plant Biol. 2020, 63, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.-I.; Pandian, S.; Rakkammal, K.; Largia, M.J.V.; Thamilarasan, S.K.; Balaji, S.; Zoclanclounon, Y.A.B.; Shilpha, J.; Ramesh, M. Jasmonates in Plant Growth and Development and Elicitation of Secondary Metabolites: An Updated Overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świa̧tek, A.; Lenjou, M.; Van Bockstaele, D.; Inzé, D.; Van Onckelen, H. Differential Effect of Jasmonic Acid and Abscisic Acid on Cell Cycle Progression in Tobacco BY-2 Cells. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, M. Role and Activity of Jasmonates in Plants under in Vitro Conditions. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. 2021, 146, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Takeuchi, Y.; Miyanaga, K.; Seki, M.; Furusaki, S. High Anthocyanin Accumulation in the Dark by Strawberry (Fragaria Ananassa) Callus. Biotechnol. Lett. 1999, 21, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennayake, C.K.; Takagi, S.; Nishimura, K.; Kanechi, M.; Uno, Y.; Inagaki, N. Differential Expression of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Genes in Suspension Culture Cells of Rosa Hybrida Cv. Charleston. Plant Biotechnol. 2006, 23, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, C.; Zhang, W.; Franco, C. Manipulating Anthocyanin Composition in Vitis Vinifera Suspension Cultures by Elicitation with Jasmonic Acid and Light Irradiation. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003, 25, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaele, S.; Vailleau, F.; Léger, A.; Joubès, J.; Miersch, O.; Huard, C.; Blée, E.; Mongrand, S.; Domergue, F.; Roby, D. A MYB Transcription Factor Regulates Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acid Biosynthesis for Activation of the Hypersensitive Cell Death Response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhaber-Pasillas, G.; Mustafa, N.; Verpoorte, R. Jasmonic Acid Effect on the Fatty Acid and Terpenoid Indole Alkaloid Accumulation in Cell Suspension Cultures of Catharanthus Roseus. Molecules 2014, 19, 10242–10260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, Y. Analysis of Phospholipids, Sterols, and Fatty Acids in Taxus Chinensis Var. Mairei Cells in Response to Shear Stress. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2009, 54, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucker, B.; Selmar, D. Biochemistry and Molecular Basis of Intracellular Flavonoid Transport in Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Suh, M.C. Arabidopsis Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Is Negatively Regulated by the DEWAX Gene Encoding an AP2/ERF-Type Transcription Factor. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kosma, D.K.; Lü, S. Functional Role of Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetases in Plant Development and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Nikovics, K.; To, A.; Lepiniec, L.; Fedosejevs, E.T.; Van Doren, S.R.; Baud, S.; Thelen, J.J. Docking of Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase to the Plastid Envelope Membrane Attenuates Fatty Acid Production in Plants. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, A.A.; Wrischer, M.; Kunst, L. Accumulation of Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acids in Membrane Glycerolipids Is Associated with Dramatic Alterations in Plant Morphology. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1889–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Nagano, Y. Plant Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase: Structure, Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Gene Manipulation for Plant Breeding. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Balderas, R.E.; García-Ponce, B.; Rocha-Sosa, M. Hormonal and Stress Induction of the Gene Encoding Common Bean Acetyl-Coenzyme A Carboxylase. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Nakabayashi, R.; Higashi, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Tohge, T.; Fernie, A.R. The Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathway in Arabidopsis: Structural and Genetic Diversity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, X.; Wu, W.; Zhou, B. Light Induced Regulation Pathway of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, N.; Lin, H. Contribution of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism to Plant Development and Plant–Environment Interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.S.; Funston, A.M. Celastraceae, Euonymus. In Flora of China, (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae); Wu, Z.Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.Y., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China and Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, USA, 2008; pp. 440–463. [Google Scholar]

- Savinov, I.A.; Trusov, N.A. Far Eastern Species of Euonymus L. (Celastraceae): Additional Data on Diagnostic Characters and Distribution. Bot. Pacifica 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, P.; Mayer, E.P.; Fowler, S.D. Nile Red: A Selective Fluorescent Stain for Intracellular Lipid Droplets. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 100, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escorcia, W.; Ruter, D.L.; Nhan, J.; Curran, S.P. Quantification of Lipid Abundance and Evaluation of Lipid Distribution in Caenorhabditis Elegans by Nile Red and Oil Red O Staining. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 133, e57352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E.; Eisele, T.; Giusti, M.M.; Hach, J.; Hofsommer, H.; Koswig, S.; Krueger, D.A.; Kupina; , S. ; et al. Determination of Total Monomeric Anthocyanin Pigment Content of Fruit Juices, Beverages, Natural Colorants, and Wines by the PH Differential Method: Collaborative Study. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Prior, R.L. Systematic Identification and Characterization of Anthocyanins by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in Common Foods in the United States: Fruits and Berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | 2013 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. max.* | Em-D* | Em-L** | |

| Maximum growth index, IFW | 5.18 ± 0.64 a | 6.54 ± 0.43 b | 7.31 ± 0.8 b |

| Maximum growth index, IDW | 4.75 ± 0.51 a | 7.96 ± 0.71 b | 9.89 ± 1.14 c |

| Specific growth rate, μFW (day–1) | 0.119 ± 0.01 a | 0.197 ± 0.03 b | 0.174 ± 0.03 b |

| Specific growth rate, μDW (day–1) | 0.099 ± 0.01 a | 0.214 ± 0.02 b | 0.175 ± 0.01 c |

| Doubling time, τFW (day) | 5.82 | 3.52 | 3.98 |

| Doubling time, τDW (day) | 7.00 | 3.24 | 3.96 |

| Maximum DW accumulation, g/L | 17.37 ± 0.36 a | 19.50 ± 0.14 b | 18.90 ± 0.5 b |

| Water content on the 7th, 11th, 14th, and 21st day, % | 85, 86, 86, 87 | 90, 89, 95, 96 | 90, 90, 94, 95 |

| Average viability in subculture, % | 84 ± 7 a | 87 ± 6 a | 83 ± 8 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).