Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Study Approval

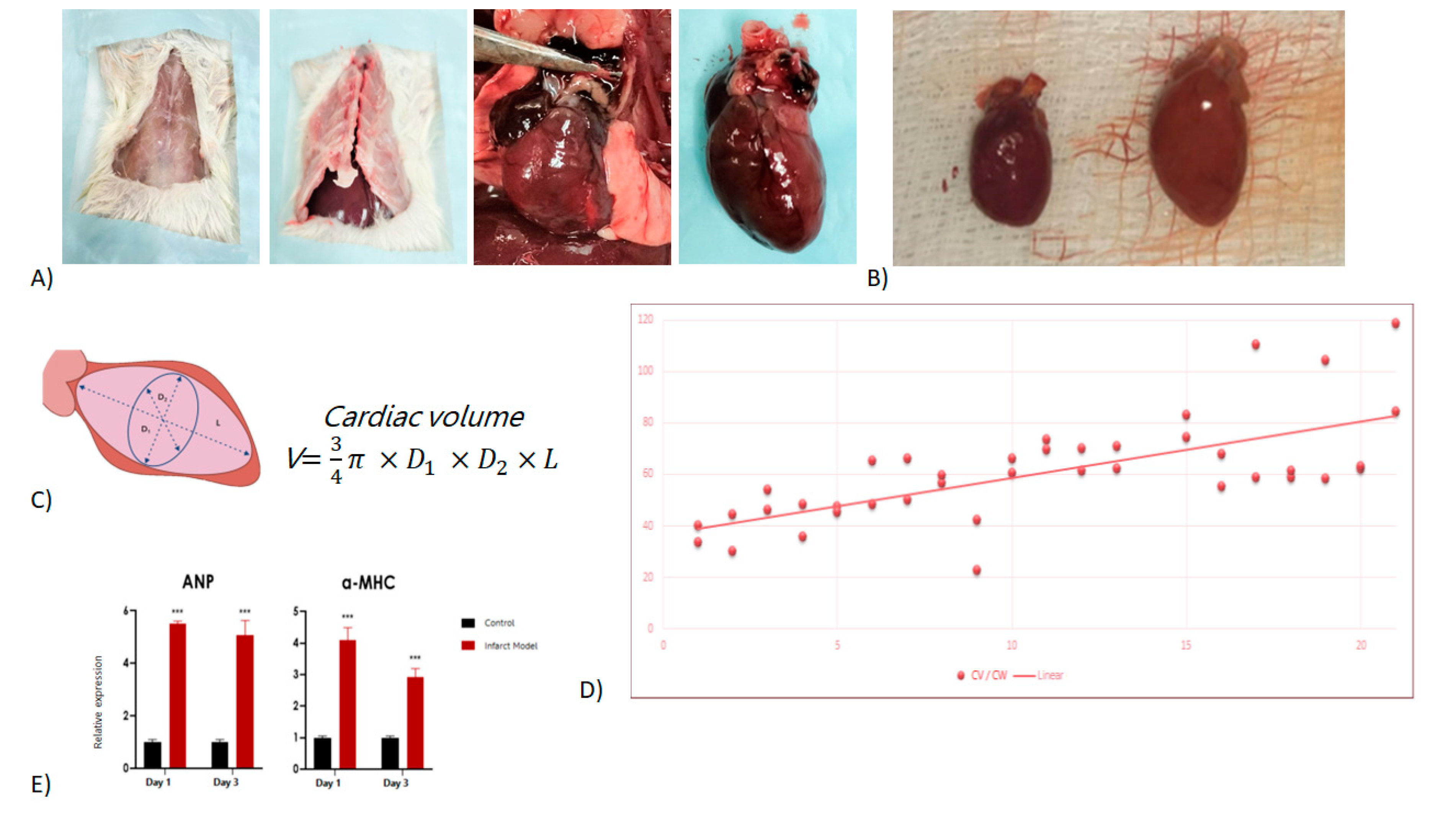

2.2. Rat model and cardiotomy

2.3. Cardiac morphometry and heart volume calculation

2.3. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

2.4. Statistical analysis

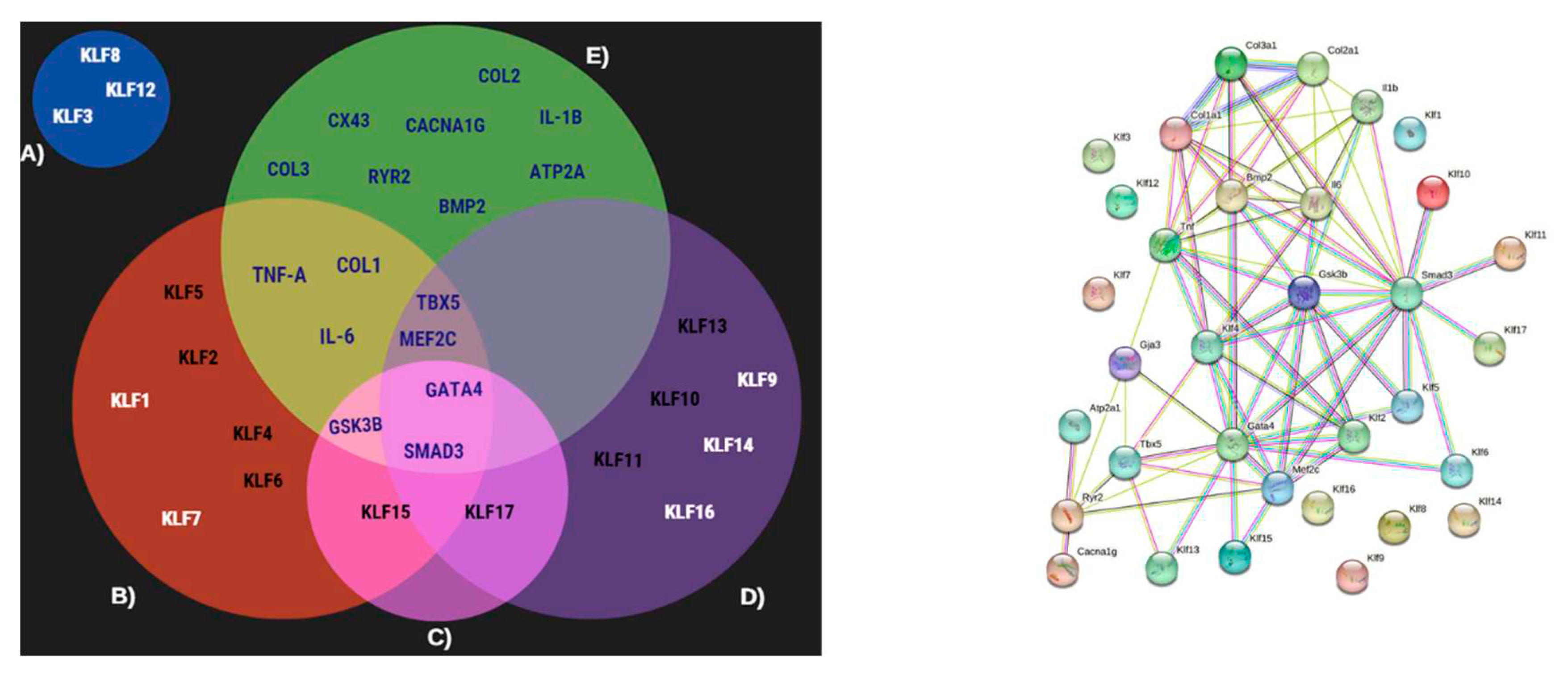

2.5. STRING

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO The Top 10 Causes of Death Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Gaziano, T.; Reddy, S.; Paccaud, F.; Horton, S. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. In ; Jamison, D., Berman, J., Measham, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Washington.

- Mechanic, O.J.; Gavin, M.; Grossman, S.A.; Ziegler, K. Acute Myocardial Infarction (Nursing). 2022.

- Ferrini, A.; Stevens, M.M.; Sattler, S.; Rosenthal, N. Toward Regeneration of the Heart: Bioengineering Strategies for Immunomodulation. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I. Krüppel-like Factors in Metabolic Homeostasis and Cardiometabolic Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2018, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosdocimo, D.A.; Sabeh, M.K.; Jain, M.K. Kruppel-like Factors in Muscle Health and Disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2015, 25, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, B.B.; Yang, V.W. Mammalian Krüppel-like Factors in Health and Diseases. Physiol Rev 2010, 90, 1337–1381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tetreault, M.-P.; Yang, Y.; Katz, J.P. Krüppel-like Factors in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2013, 13, 701–713. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, R.A.; Fledderus, J.O.; Volger, O.L.; Van Wanrooij, E.J.A.; Pardali, E.; Weesie, F.; Kuiper, J.; Pannekoek, H.; Ten Dijke, P.; Horrevoets, A.J.G. KLF2 Suppresses TGF-β Signaling in Endothelium through Induction of Smad7 and Inhibition of AP-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Zhuang, T.; Tomlinson, B. Endothelial Klf2-Foxp1-TGFβ Signal Mediates the Inhibitory Effects of Simvastatin on Maladaptive Cardiac Remodeling. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, I.D.; Hoffman, M.; Gaignebet, L.; Lucchese, A.M.; Markopoulou, E.; Palioura, D.; Wang, C.; Bannister, T.D.; Christofidou-Solomidou, M.; Oka, S. KLF5 Is Induced by FOXO1 and Causes Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 2021, 128, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.; Palioura, D.; Kyriazis, I.D.; Cimini, M.; Badolia, R.; Rajan, S.; Gao, E.; Nikolaidis, N.; Schulze, P.C.; Goldberg, I.J. Cardiomyocyte Krüppel-like Factor 5 Promotes de Novo Ceramide Biosynthesis and Contributes to Eccentric Remodeling in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2021, 143, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, T.; Manabe, I.; Fukushima, Y.; Tobe, K.; Aizawa, K.; Miyamoto, S.; Kawai-Kowase, K.; Moriyama, N.; Imai, Y.; Kawakami, H. Krüppel-like Zinc-Finger Transcription Factor KLF5/BTEB2 Is a Target for Angiotensin II Signaling and an Essential Regulator of Cardiovascular Remodeling. Nat Med 2002, 8, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, R.; Suzuki, T.; Aizawa, K.; Shindo, T.; Manabe, I. Significance of the Transcription Factor KLF5 in Cardiovascular Remodeling. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2005, 3, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grimm, D. Development of Heart Failure Following Isoproterenol Administration in the Rat: Role of the Renin–Angiotensin System. Cardiovasc Res 1998, 37, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; Rajabian, A.; Sobhanifar, M.-A.; Alavi, M.S.; Taghipour, Z.; Hasanpour, M.; Iranshahi, M.; Boroumand-Noughabi, S.; Banach, M.; Sahebkar, A. Attenuation of Isoprenaline-Induced Myocardial Infarction by Rheum Turkestanicum. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 148, 112775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jia, H.; Chang, X.; Ding, G.; Zhang, H.; Zou, Z.-M. The Metabolic Disturbances of Isoproterenol Induced Myocardial Infarction in Rats Based on a Tissue Targeted Metabonomics. Mol Biosyst 2013, 9, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrini, A.; Stevens, M.M.; Sattler, S.; Rosenthal, N. Toward Regeneration of the Heart: Bioengineering Strategies for Immunomodulation. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, H.; Hanna, A.; Humeres, C.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Properties and Functions of Fibroblasts and Myofibroblasts in Myocardial Infarction. Cells 2022, 11, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardali, E.; Sanchez-Duffhues, G.; Gomez-Puerto, M.C.; Dijke, P. TGF- β -Induced Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Fibrotic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, N.; Qi, Y.; Du, J. Krüppel-Like Factor 4 Transcriptionally Regulates TGF-Β1 and Contributes to Cardiac Myofibroblast Differentiation. PLoS One 2013, 8, 0–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, S.; Gray, S.; Heymans, S.; Haldar, S.M.; Wang, B.; Pfister, O.; Cui, L.; Kumar, A.; Lin, Z.; Sen-Banerjee, S.; et al. Kruppel-like Factor 15 Is a Regulator of Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 7074–7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islas, J.; Moreno-Cuevas, J. A MicroRNA Perspective on Cardiovascular Development and Diseases: An Update. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Mares-Montemayor, J.D.; Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Delgado-Gallegos, J.L.; Quiroz-Reyes, A.G.; Roacho-Perez, J.A.; Benitez-Chao, D.F.; Garza-Ocañas, L.; Arevalo-Martinez, G.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; et al. The Involvement of Krüppel-like Factors in Cardiovascular Diseases. Life 2023, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarre-Álvarez, D.; Cabrera-Jardines, R Rodríguez-Weber, F. Enfermedad Cardiovascular Aterosclerótica. Revisión de Las Escalas de Riesgo y Edad Cardiovascular. Med Int Mex 2018, 6, 910–923. [Google Scholar]

- Goradel, N.H.; Hour, F.G.; Negahdari, B.; Malekshahi, Z.V.; Hashemzehi, M.; Masoudifar, A.; Mirzaei, H. Stem Cell Therapy: A New Therapeutic Option for Cardiovascular Diseases. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Kalmykov, V.A.; Grechko, A. V.; Shakhpazyan, N.K.; Orekhov, A.N. The Role of KLF2 in the Regulation of Atherosclerosis Development and Potential Use of KLF2-Targeted Therapy. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinjamur, D.S.; Wade, K.J.; Mohamad, S.F.; Haar, J.L.; Sawyer, S.T.; Lloyd, J.A. Krüppel-like Transcription Factors KLF1 and KLF2 Have Unique and Coordinate Roles in Regulating Embryonic Erythroid Precursor Maturation. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankman, L.S.; Gomez, D.; Cherepanova, O.A.; Salmon, M.; Alencar, G.F.; Haskins, R.M.; Swiatlowska, P.; Newman, A.A.C.; Greene, E.S.; Straub, A.C.; et al. KLF4-Dependent Phenotypic Modulation of Smooth Muscle Cells Has a Key Role in Atherosclerotic Plaque Pathogenesis. Nat Med 2015, 21, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabona, J.M.P.; Zeng, Z.; Simmen, F.A.; Simmen, R.C.M. Functional Differentiation of Uterine Stromal Cells Involves Cross-Regulation between Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 and Krüppel-like Factor (KLF) Family Members KLF9 and KLF13. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3396–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, J.J.; Wijnen, W.J.; van der Made, I.; Hiller, M.; Swinnen, M.; Vandendriessche, T.; Chuah, M.; Pinto, Y.M.; Creemers, E.E. Repression of Cardiac Hypertrophy by KLF15: Underlying Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. PLoS One 2012, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Pritchard, D.M.; Yang, X.; Bennett, E.; Liu, G.; Liu, C.; Ai, W. KLF4 Gene Expression Is Inhibited by the Notch Signaling Pathway That Controls Goblet Cell Differentiation in Mouse Gastrointestinal Tract. AJP: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2009, 296, G490–G498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xi, X.; Zhao, B.; Su, Z.; Wang, Z. KLF4 Protects Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells from Ischemic Stroke Induced Apoptosis by Transcriptionally Activating MALAT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 495, 2376–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.P.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Ting, K.K.; Foley, M.; Cogger, V.; Yang, Z.; Liu, F.; et al. Ponatinib (AP24534) Inhibits MEKK3-KLF Signaling and Prevents Formation and Progression of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Sci Adv 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, D.; Tangutur, A.D.; Khatua, T.N.; Saxena, P.; Banerjee, S.K.; Bhadra, M.P. A Proteomic View of Isoproterenol Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy: Prohibitin Identified as a Potential Biomarker in Rats. J Transl Med 2013, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilatovskaya, D. V.; Levchenko, V.; Winsor, K.; Blass, G.R.; Spires, D.R.; Sarsenova, E.; Polina, I.; Zietara, A.; Paterson, M.; Kriegel, A.J.; et al. Effects of Elevation of ANP and Its Deficiency on Cardiorenal Function. JCI Insight 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NISHIKIMI, T.; MAEDA, N.; MATSUOKA, H. The Role of Natriuretic Peptides in Cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 2006, 69, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhunen, O.; Sármán, B.; Kerkelä, R.; Szokodi, I.; Papp, L.; Tóth, M.; Ruskoaho, H. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases P38 and ERK 1/2 Mediate the Wall Stress-Induced Activation of GATA-4 Binding in Adult Heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 24852–24860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; De Windt, L.J.; Witt, S.A.; Kimball, T.R.; Markham, B.E.; Molkentin, J.D. The Transcription Factors GATA4 and GATA6 Regulate Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy in Vitro and in Vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 30245–30253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-H.; Chen, D.-Q.; Wang, Y.-N.; Feng, Y.-L.; Cao, G.; Vaziri, N.D.; Zhao, Y.-Y. New Insights into TGF-β/Smad Signaling in Tissue Fibrosis. Chem Biol Interact 2018, 292, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, J.J.; Wijnen, W.J.; Hiller, M.; Van Der Made, I.; Lentink, V.; Van Leeuwen, R.E.W.; Herias, V.; Pokharel, S.; Heymans, S.; De Windt, L.J.; et al. Regulation of Cardiac Gene Expression by KLF15, a Repressor of Myocardin Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 27449–27456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenying, L.; Lu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Eitzman, D.; Chen, E.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, J. KLF11 Protects against Venous Thrombosis via Suppressing Tissue Factor Expression. Thromb Haemost 2021, 122, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, C.S.L.; Yung, M.M.H.; Hui, L.M.N.; Leung, L.L.; Liang, R.; Chen, K.; Liu, S.S.; Qin, Y.; Leung, T.H.Y.; Lee, K.-F.; et al. MicroRNA-141 Enhances Anoikis Resistance in Metastatic Progression of Ovarian Cancer through Targeting KLF12/Sp1/Survivin Axis. Mol Cancer 2017, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, A.S.; Park, K.; Wang, Y.; Teoh, J.; Aonuma, T.; Tang, Y.; Su, H.; Weintraub, N.L.; Kim, I. A Carvedilol-Responsive MicroRNA, MiR-125b-5p Protects the Heart from Acute Myocardial Infarction by Repressing pro-Apoptotic Bak1 and Klf13 in Cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2018, 114, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Herring, B.P. Mechanisms Responsible for the Promoter-Specific Effects of Myocardin. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 10861–10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoforou, N.; Chellappan, M.; Adler, A.F.; Kirkton, R.D.; Wu, T.; Addis, R.C.; Bursac, N.; Leong, K.W. Transcription Factors MYOCD, SRF, Mesp1 and SMARCD3 Enhance the Cardio-Inducing Effect of GATA4, TBX5, and MEF2C during Direct Cellular Reprogramming. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Earlier and Broader Roles of Mesp1 in Cardiovascular Development. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017, 74, 1969–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Diaz, A.D.; Benham, A.; Xu, X.; Wijaya, C.S.; Fa’Ak, F.; Luo, W.; Soibam, B.; Azares, A.; et al. Mesp1 Marked Cardiac Progenitor Cells Repair Infarcted Mouse Hearts. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, E.; Da Costa Martins, P.A.; De Windt, L.J. Regulation of Fetal Gene Expression in Heart Failure ☆. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y.; Ye, Y.; Jing, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiong, M.; Yang, K.; et al. Single-Nucleus Transcriptomics Reveals a Gatekeeper Role for FOXP1 in Primate Cardiac Aging. Protein Cell 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

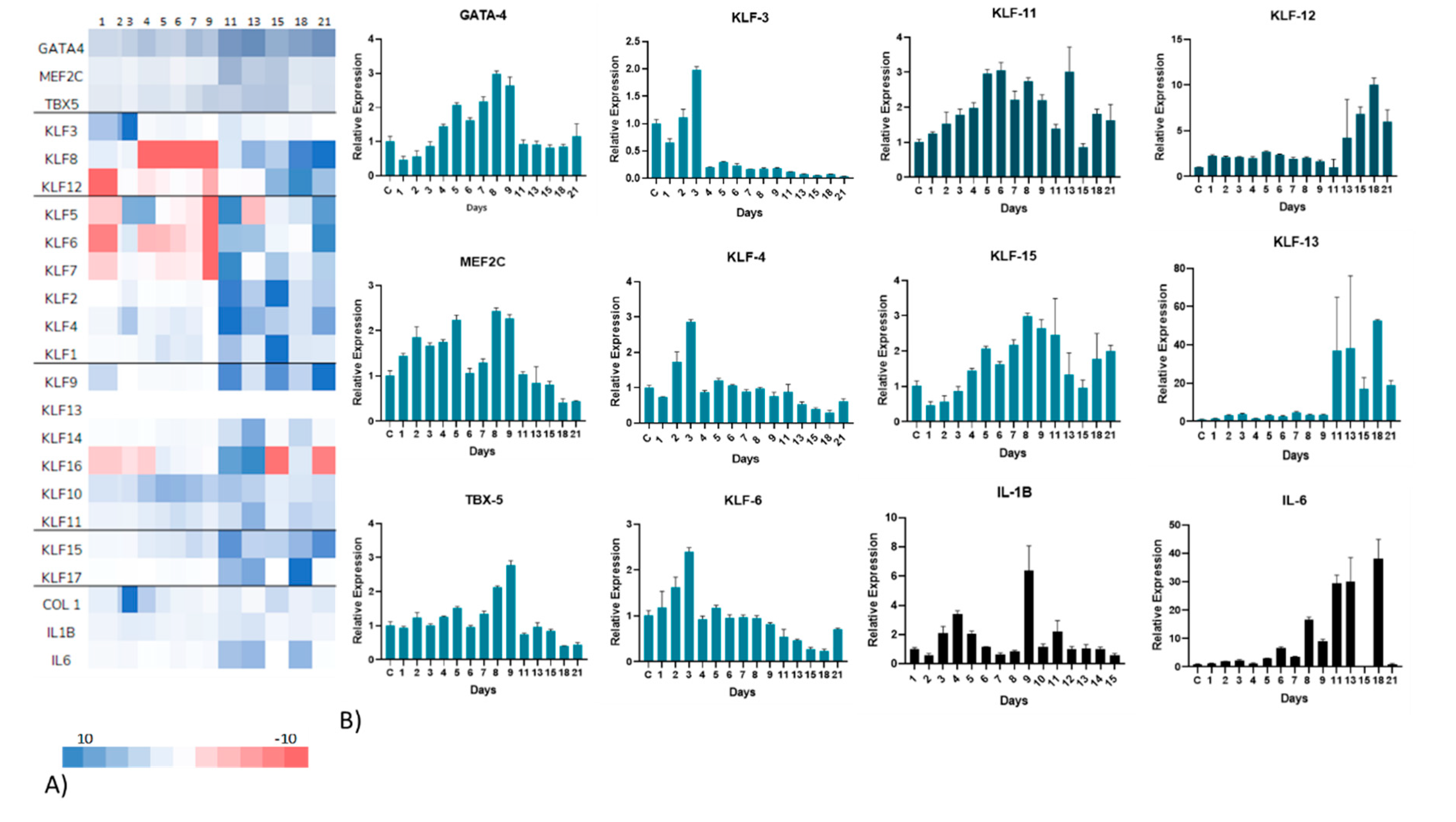

| Gene | Regulation over time | Max Expression Day | Relative Expression | Potential Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

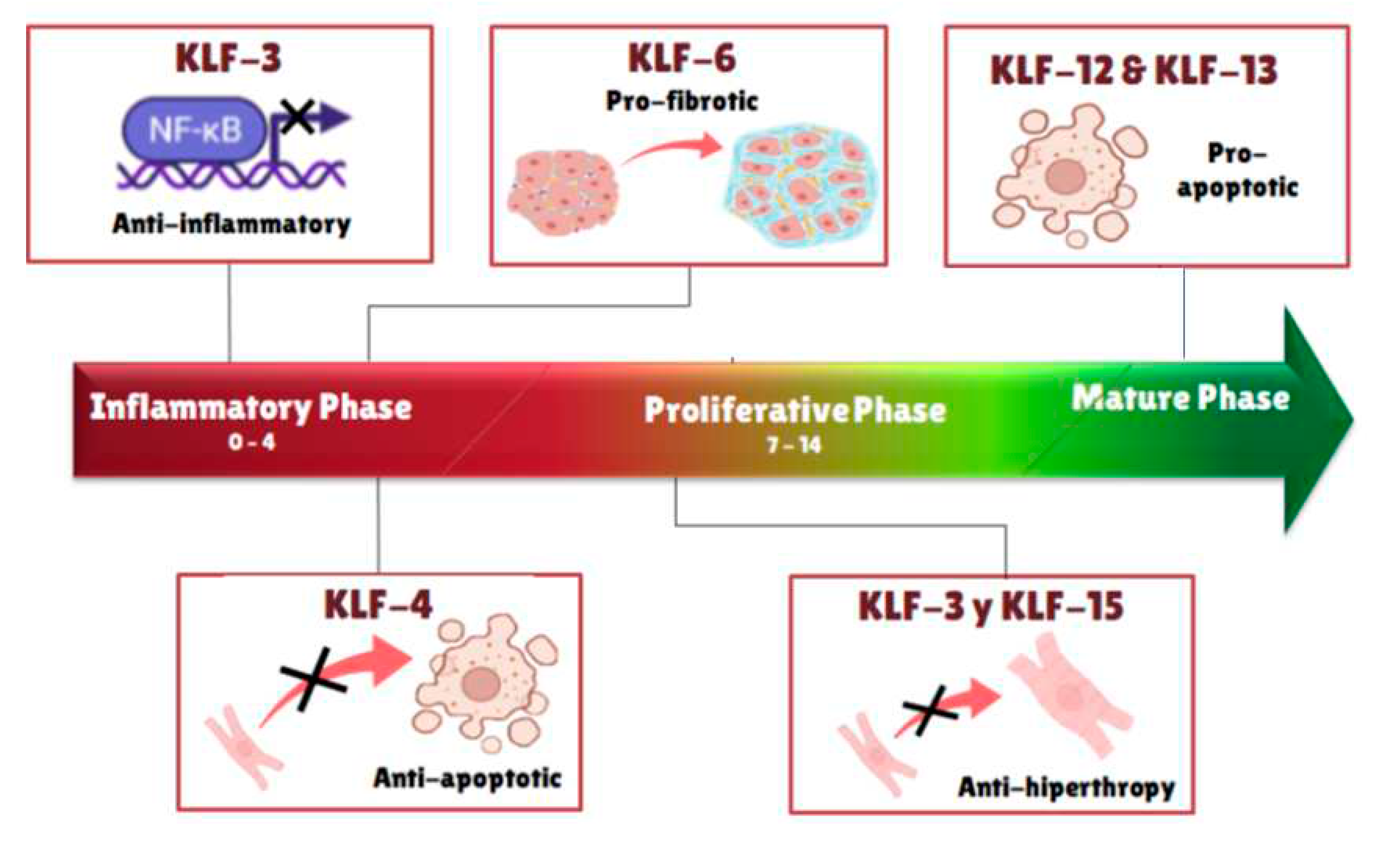

| KLF-3 | Downregulated | 3 | 1.98x | Hypertrophy repressor |

| KLF-4 | Downregulated | 2 | 1.7x | Antiapoptotic |

| 3 | 2.8x | |||

| KLF-6 | Upregulated | 3 | 2.4 | Profibrotic |

| KLF-11 | Upregulated | 5 | 2.96x | Unknown |

| 6 | 3.05x | |||

| 13 | 3x | |||

| KLF-12 | Upregulated | 16 | 7.2x | Proapoptotic |

| 18 | 9.7x | |||

| KLF-13 | Upregulated | 18 | 53x | Proapoptotic / Anti-inflammatory |

| KLF-15 | Upregulated | 8 | 3x | Hypertrophy modulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).