Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

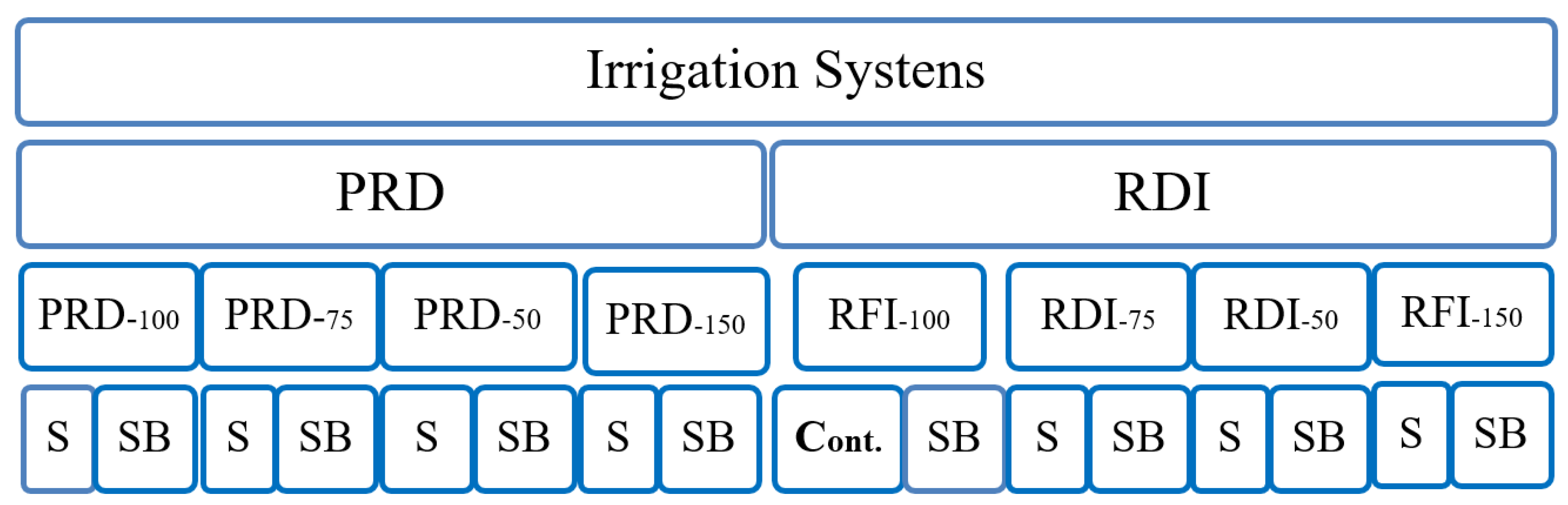

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Climate

2.3. The soil of the experimental sites

2.4. Preparing and processing lysimeters to elicit cucumber crop coefficient

2.6. Cultivation

2.7. Crop fertilization

2.8. Daily readings of plant environment data

2.9. Field measurements and data collected

2.10. Estimation of crop water requirements and crop coefficient

2.10.1. Derivation of the crop coefficient (Kc) for experimental crops using lysimeters

2.10.2. Equations used in estimating water requirements for irrigation

2.11. Water Productivity Function (WPF)

2.12. Yield response factor for deficit irrigation (Ky)

2.13. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) and gross water requirement (GWR)

3.2. Comparison of the average crop coefficient (Kc) of greenhouse cucumber according to the reference crop of alfalfa (ETr)

3.3. Shoot measurements during the growth period

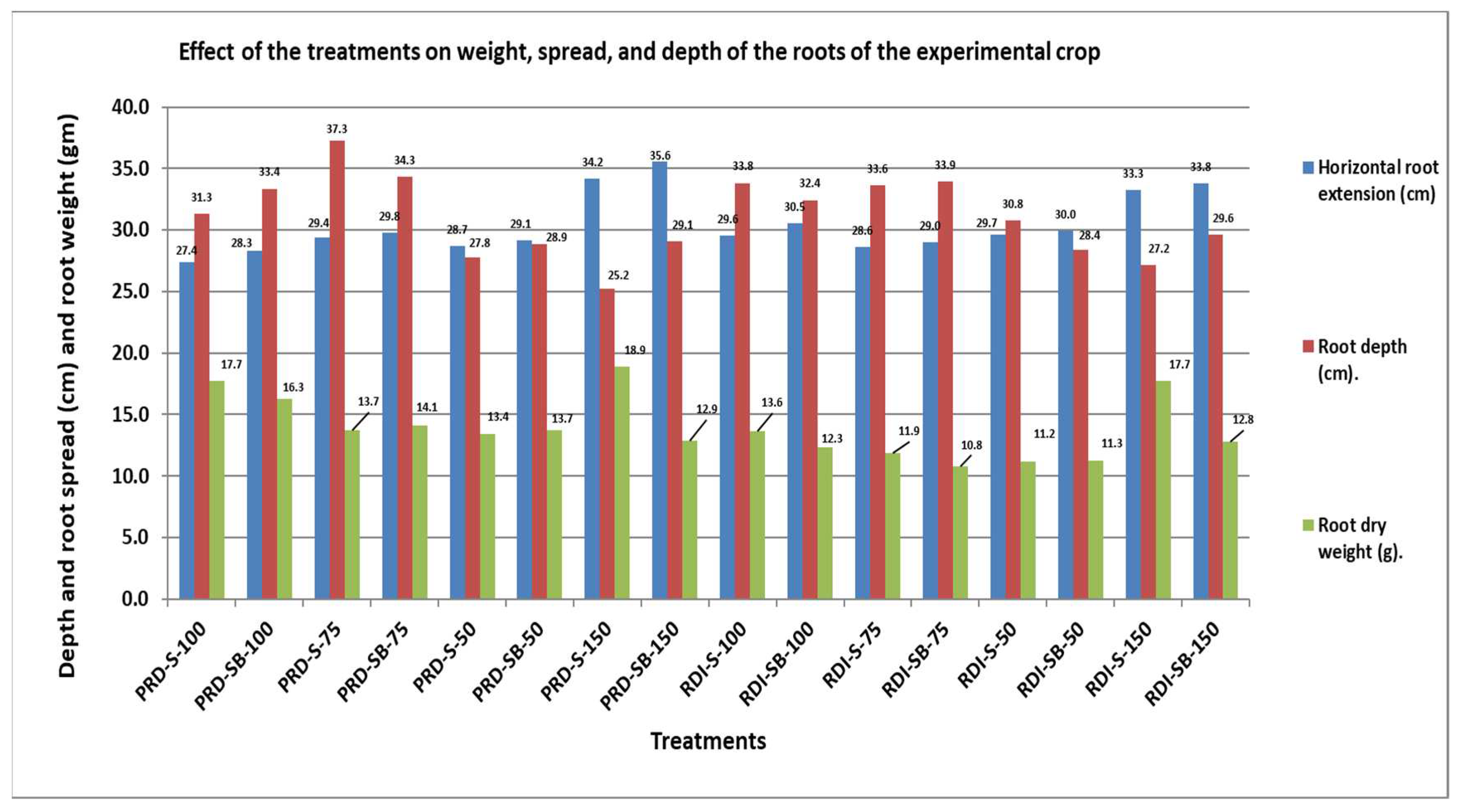

3.4. Effect of irrigation system PRD and RDI on root depth, spread, and root size of greenhouse cucumber

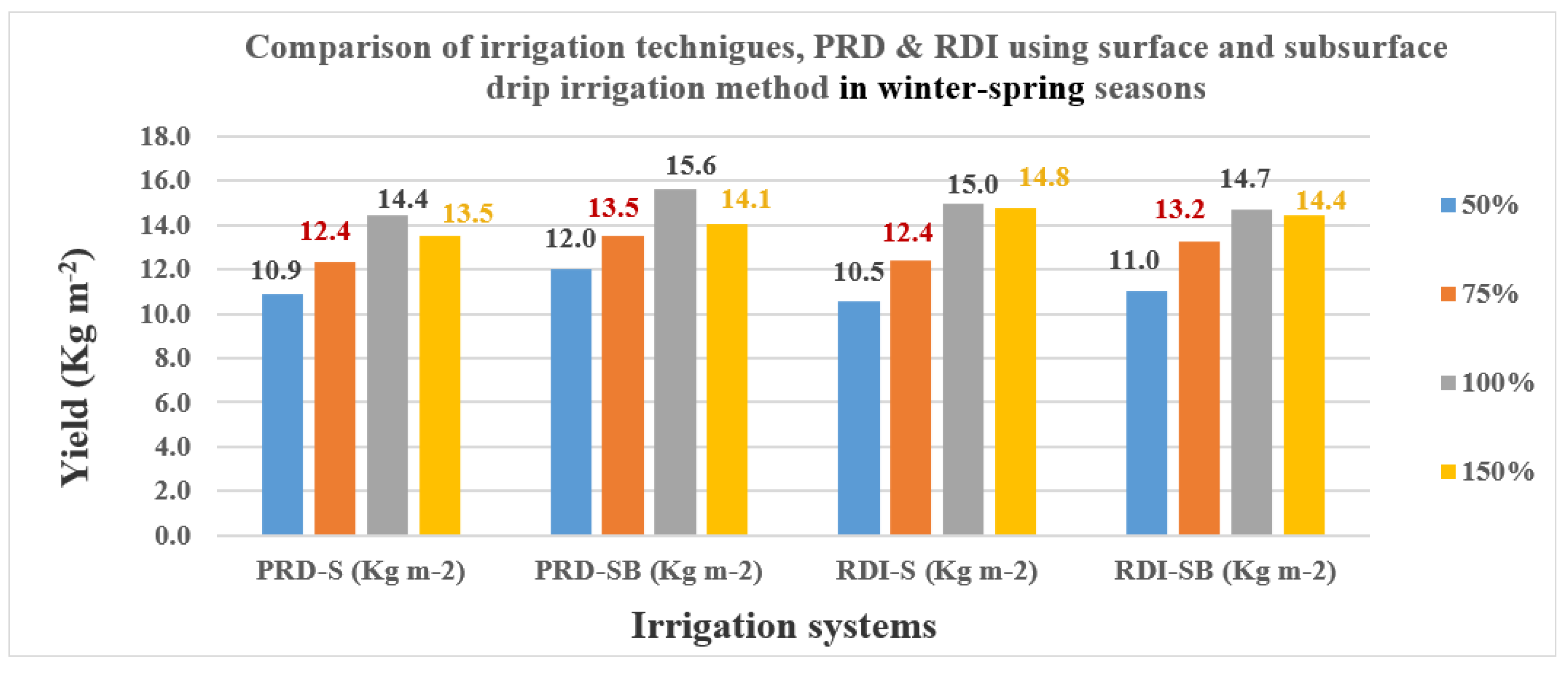

3.5. Effect of (PRD-S, PRD-SB, RDI-S, and RDI-SB) in the winter-spring seasons

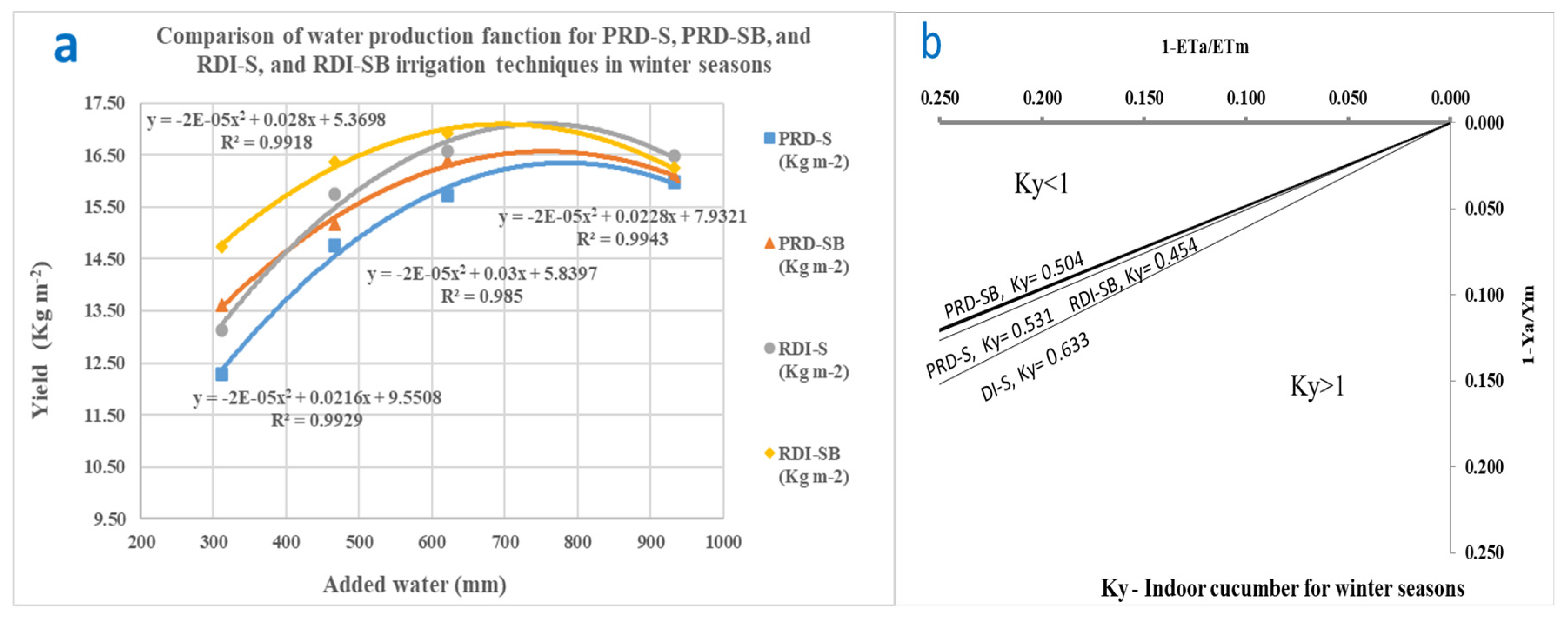

3.6. Comparison of water productivity functions (WPF) and yield response factors (Ky) in the winter and spring seasons

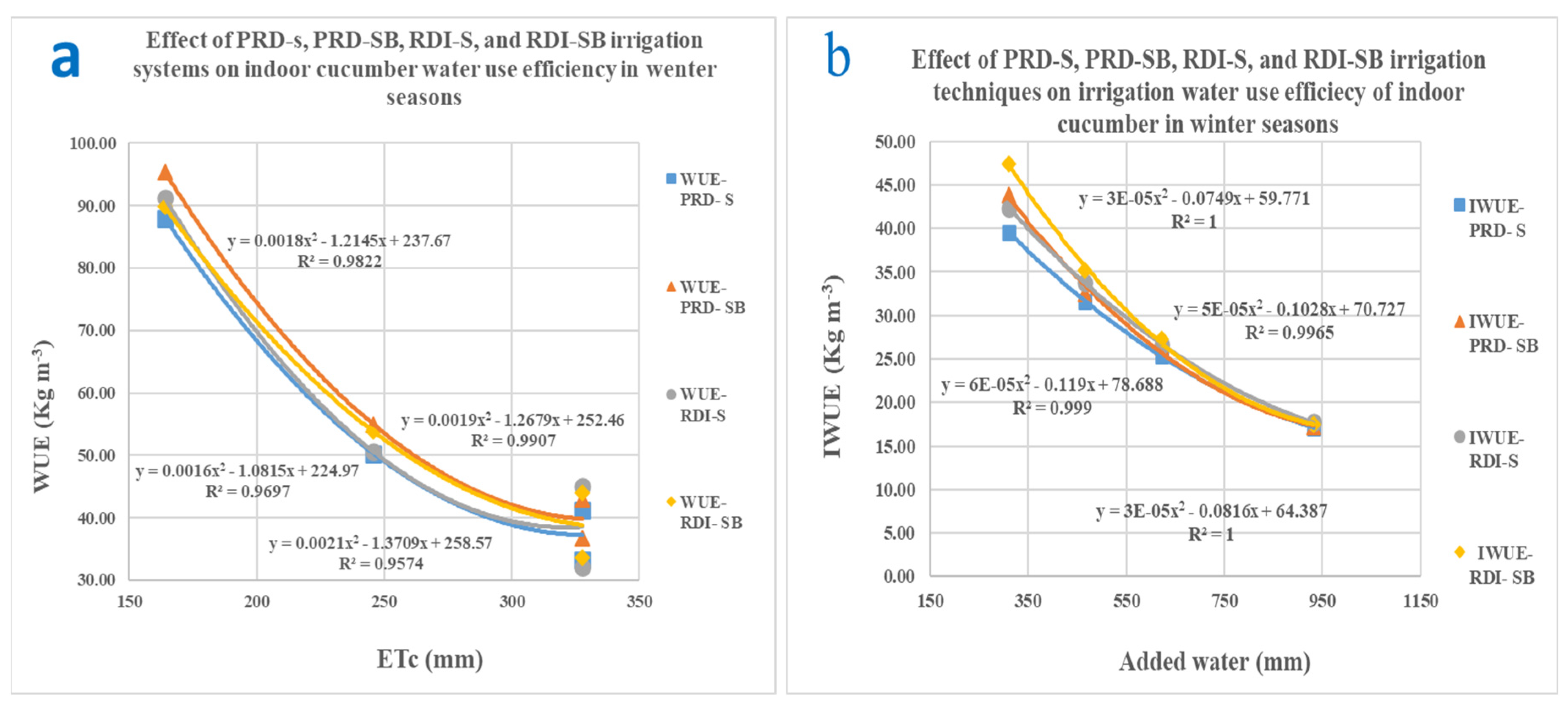

3.7. Effect of PRD-S, PRD-SB, RDI-S, and RDI-SB on irrigation efficiencies in the winter-spring seasons

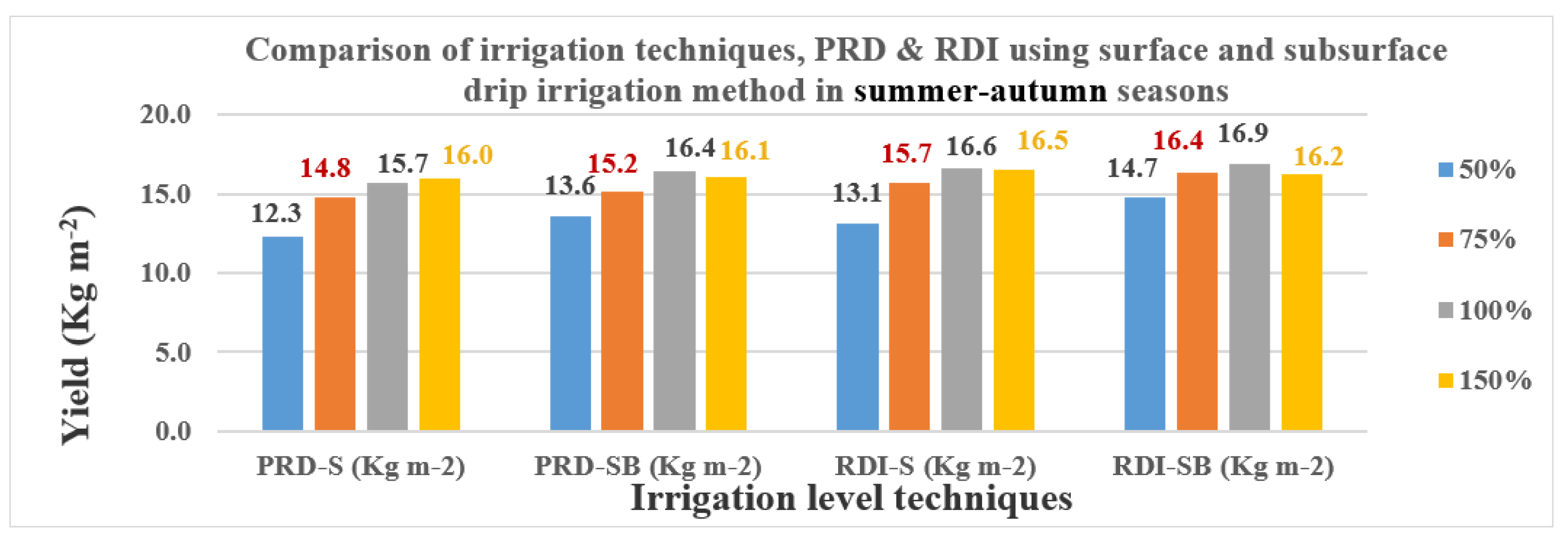

3.8. Effect of PRD-S, PRD-SB, RDI-S, and RDI-SB in the summer-autumn seasons

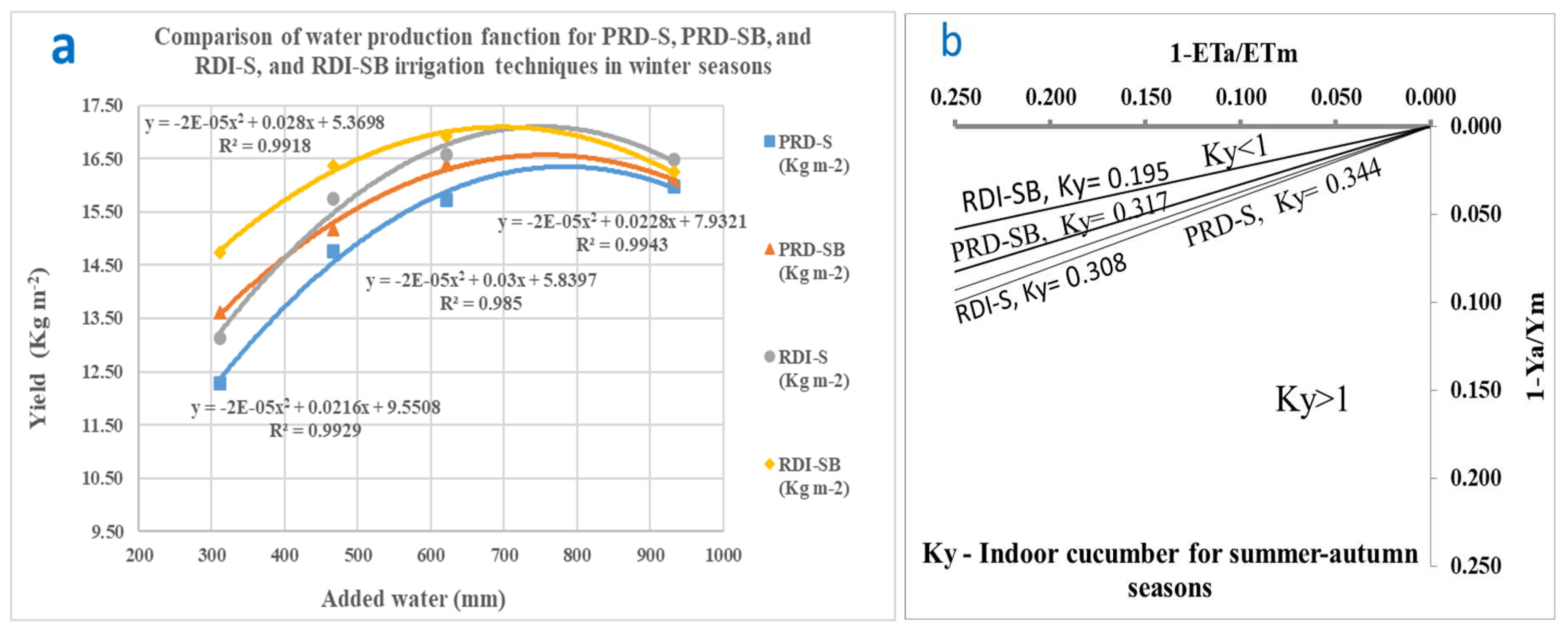

3.9. Comparison of water productivity functions (WPF) and yield response factor (Ky) summer-autumn seasons

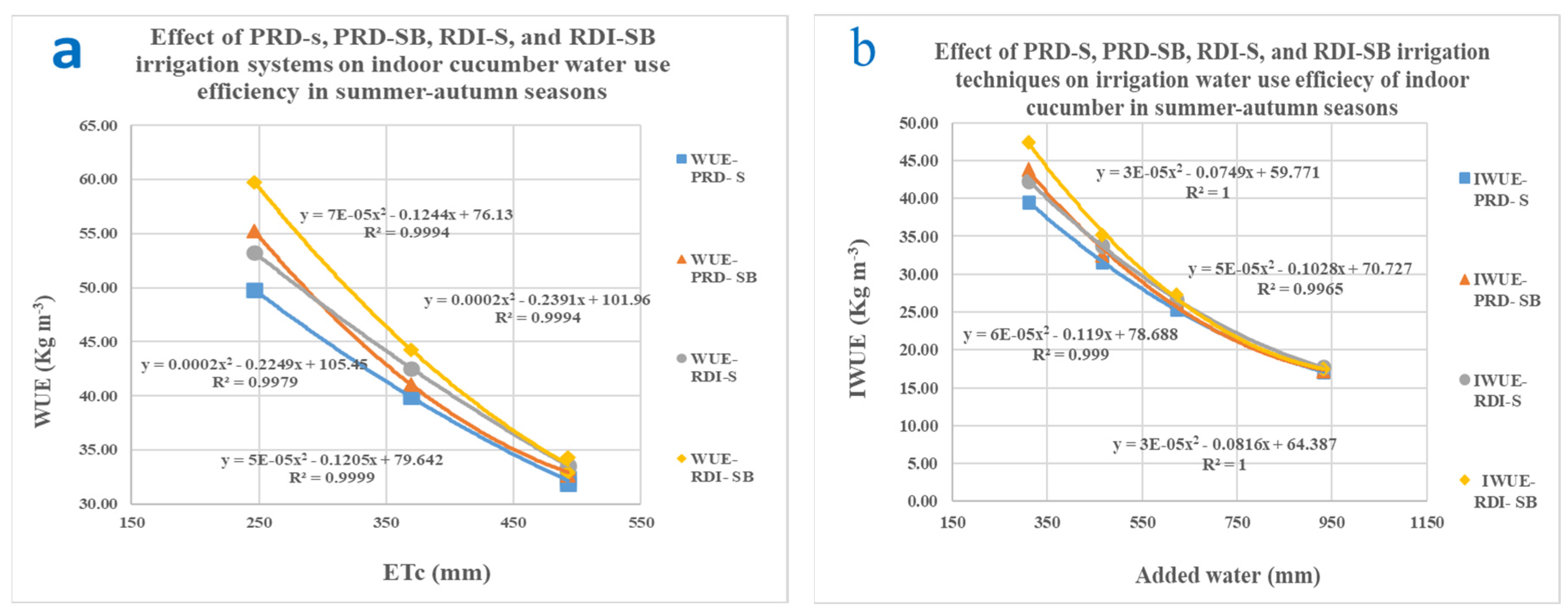

3.10. Effect of PRD-S, PRD-SB, RDI-S, and RDI-SB on irrigation efficiencies in the summer and autumn seasons

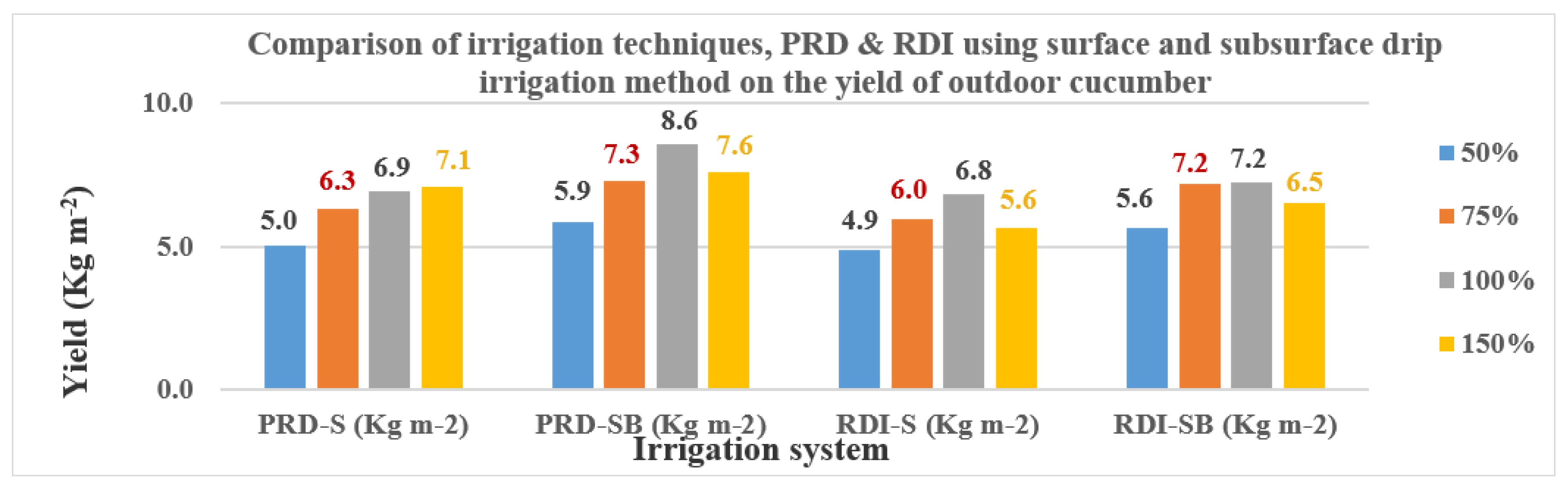

3.11. Effect of (PRD-S, PRD-SB, RDI-S, and RDI-SB) on open field cucumber yield

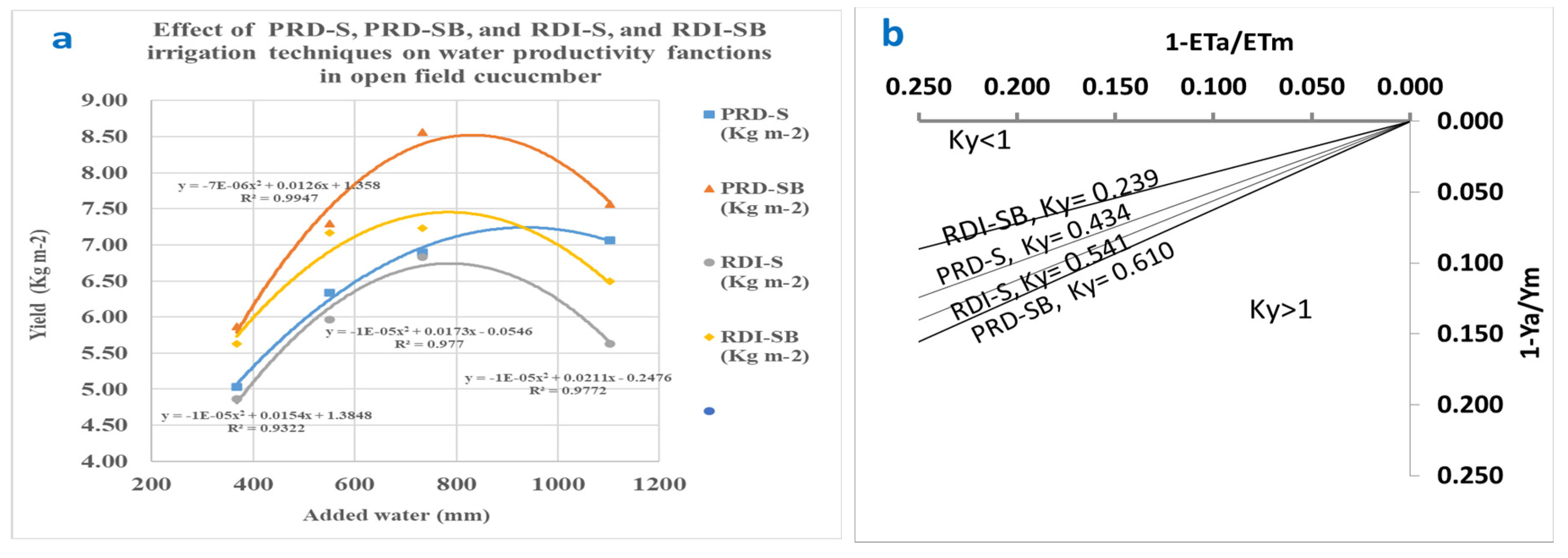

3.12. Effect of the irrigation technique on water productivity function (WPF) and yield response factor (Ky) for cucumber in an open field

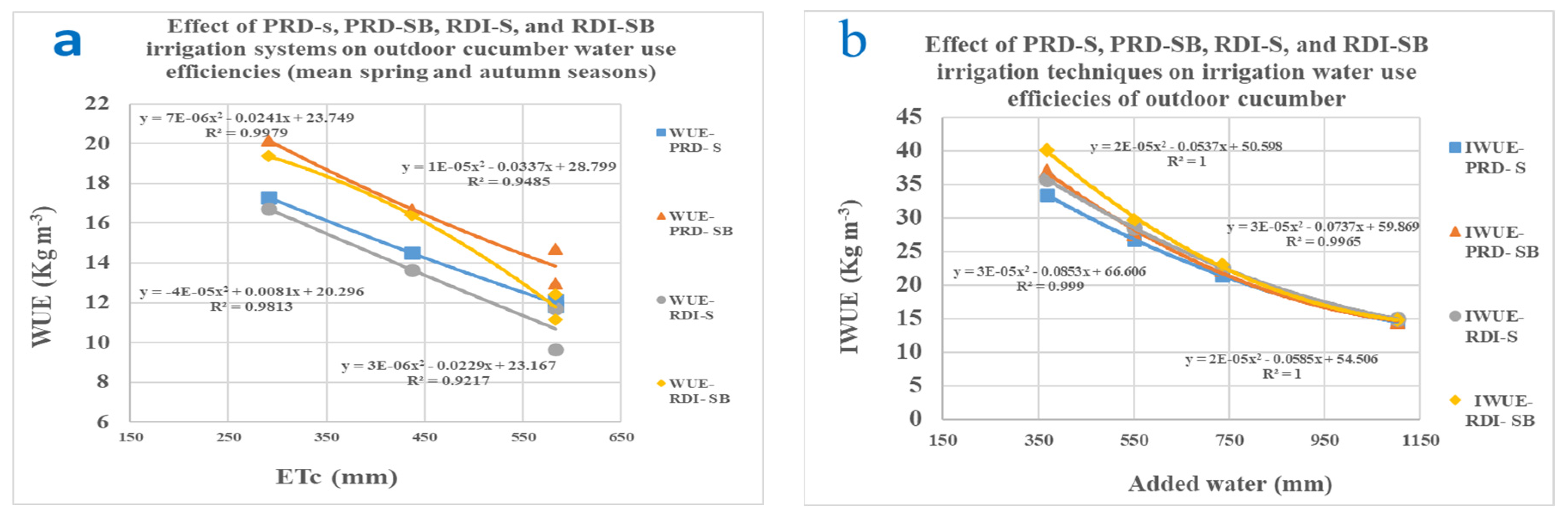

3.13. Effect of the irrigation technique on irrigation efficiencies for cucumber in an open field

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bates, B.C.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Wu, S.; Palutikof, J.P. Climate Change and Water; IPCC Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elhani, S.; Haddadi, M.; Csákvári, E.; Zantar, S.; Hamim, A.; Villányi, V.; Douaik, A.; Bánfalvi, Z. Effects of partial root-zone drying and deficit irrigation on yield, irrigation water-use efficiency, and some quality traits of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) under glasshouse conditions. Agricultural Water Management 2019, 224, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Hussain, T.; Jiang Ahmad, A.; Yao, J.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Min, L.; Shen, Y. Water-Saving Potential of Subsurface Drip Irrigation for Winter Wheat. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du TKang SZhang, J.; Davies, W.J. The Journal of Experimental Botany. 2015, 66, 2253–2269. [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic Z and Stikic R. 2018. Partial Root-Zone Drying Technique: from Water Saving to the Improvement of a Fruit Quality. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 1:3. [CrossRef]

- Al-Omran, A.M.; Louki1, I.I.; Aly, A.A.; Nadeem, M.E. Impact of Deficit Irrigation on Soil Salinity and Cucumber Yield under Greenhouse Condition in an Arid Environment. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2013, 15, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaouadi, L. , H. Besser, N. kharbout, , A. Al-Omran, F. Wassar, M. Wahba, K. Yaohu, Y. Hamed . 2021. Irrigation Water Management for sustainable cultivation of date palm. Applied water Science. 11, 171 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Abolpour, B. Realistic evaluation of crop water productivity for sustainable farming of wheat in Kamin Region, Fars province, Iran. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 195, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashimi, A., Abdulkreem, A., Hashem, M. H., Bakr, B. M., Fekry, W. M., F., H., Hamdy, A. E., Abdelraouf, R. E., & Fathy, M. (2023). Using Deficit Irrigation Strategies and Organic Mulches for Improving Yield and Water Productivity of Mango under Dry Environment Conditions. Agriculture, 13(7), 1415. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., Fu, P., Lu, J. et al. Regulated deficit irrigation: an effective way to solve the shortage of agricultural water for horticulture. Stress Biology 2, 28 (2022). [CrossRef]

- English, M.J. 1990. Deficit irrigation. I: Analytical framework. J. Am. Soc. Civil Eng. USA.

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D. Deficit irrigation as on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas. Agricultural Water Management 2009, 96, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omran, A.M.; Louki, I.I.; Aly, A.A.; Al-Harbi, A.R.; Nadeem, M.E. Cucumber yield response to deficit irrigation at open field experiments on Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Egyption Journal of Soil Science. 2012, 52, 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, M., Castellanos, M., Romojaro, F., Martínez-Madrid, C., & Ribas, F. (2009). Yield and quality of melon grown under different irrigation and nitrogen rates. Agricultural Water Management, 96(5), 866-874. [CrossRef]

- Geerts, S., & Raes, D. (2009). Deficit irrigation as an on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas. Agricultural Water Management, 96(9), 1275-1284. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M., Toyosumi, I., Lopes, W., Camillo, L., Ferreira, L., Rocha Junior, D., Filho, W., Gesteira, A. Costa. M, & Filho, M. (2021) Partial rootzone drying and regulated deficit irrigation can be used as water-saving strategies without compromising fruit yield and quality in tropically grown sweet orange, The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 96:5, 663-672. [CrossRef]

- Al-Omran, A.M, I.I. Louki. and A. Alkhasha. 2023. Deficit Irrigation and Partial Root-Zone Drying Irrigation System in Arid Area. In Handbook of Irrigation Hydrology and Management (Eds. Eslamian and Eslamian). Pp 337-361. Wiley. New York. USA. [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.S.; El-Abedin, T.Z.; Al-Ghobari, H.M. Assessing effects of deficit irrigation techniques on water productivity of tomato for subsurface drip irrigation system. Int J Agric & Biol Eng 2018, 11, 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J., Ramírez, D. A., Xie, K., Li, W., Yactayo, W., Jin, L., R., Quiroz. 2018. Is Partial Root-Zone Drying More Appropriate than Drip Irrigation to Save Water in China? A Preliminary Comparative Analysis for Potato Cultivation. Potato Research. Volume 61, Issue 4, pp 391–406. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.H.; Agharezaee, M.; Kamgar-Haghighi, A.A.; Sepaskhah, R. Effects of dynamic and static deficit and partial root zone drying irrigation strategies on yield, tuber sizes distribution, and water productivity of two field grown potato cultivars. Agricultural Water Management 2014, 134, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playán, E.; Mateos, L. Modernization and optimization of irrigation systems to increase water productivity. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 80, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S., Gichuki, F., Turral, H. 2006. Water productivity: Estimation at plot, farm, and basin scale. Basin Focal Project Working Paper No. 2. Challenge Program on Water and Food, Colombo, SirLanka.

- Stewart, J.I., Cu, R.H., Pruitt, W.O., Hagan, R.M. & Tosso, J. 1977. Determination and utilization of water production functions for principal california crops. W-67 California Contributing Project Report. Davis, United States of America, University of California.

- FAO-66. 2012. Crop response factor, Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, Italy.

- Moutonnet, P. 2000. Yield Response to Field Crops to Deficit Irrigation In Deficit irrigation practices. C. Kirda, P. Moutonnet, C. Hera and D.R. Nielsen (eds). Water Report #22 FAO, Rome.

- Giuliani, M.M., Nardella, E., Gagliardi, A., Gatta. G. 2017. Deficit Irrigation and Partial Root-Zone Drying Techniques in Processing Tomato Cultivated under Mediterranean Climate Conditions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2197. [CrossRef]

- General presidency of Meteorology. 2018. Statistical report.

- Al-Omran, A.M.; Al-Ghobari, H.; Alazba, A. Determination of evapotranspiration of tomato and squash using lysimeters in central Saudi Arabia. International Agricultural Engineering Journal 2004, 13, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Louki, I.I.; Al-Omran, A.M. Calibration of Soil Moisture Sensors (ECH2O-5TE) in Hot and Saline Soils with New Empirical Equation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louki, I.I., A.M. Al-Omran, A.A. Aly and A.R. Alharbi. 2019. Sensors Effectiveness for Soil Water Content Measurements under Normal and Extreme Conditions. Irrigation and Drainage Journal. 68:979-992. [CrossRef]

- Qu, F., Zhang, Q., Jiang, Z., Zhang, C., Zhang, Z., & Hu, X. (2022). Optimizing irrigation and fertilization frequency for greenhouse cucumber grown at different air temperatures using a comprehensive evaluation model. Agricultural Water Management, 273, 107876. (. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G., L. S. Pereira, D. Raes and M. Smith. 1998. Crop evapotranspiration guidelines for computing crop water requirements. FAO Irrigation and Drainage paper #56.

- Cuenca, R. 1989. Irrigation System Design: An Engineering Approach. Prentice Hall, New jersey, USA.

- Steel, R. G. and J. H. Torrie. 1982. “Principles and Procedures of Statistics”. 2nd Ed., McGraw Hill Book Company, New York, USA.

- Loague, K.; Green, R.E. Statistical and graphical methods for evaluating solute transport models: Overview and application. J. Contam. Hydrol. 1991, 7, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotovic, M.; Nedic, V.; Despotovic, D.; Cvetanovic, S. Evaluation of empirical models for predicting monthly mean horizontal diffuse solar radiation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 56, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louki, I. I.. 2011. Effect of Deficit Irrigation on Cucumber Yield in Greenhouses and Open Field in Thadiq Governorate, Riyadh Region. Master of Science Thesis from the Department of Soil Sciences - College of Food and Agricultural Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- Nikolaou, G. , Neocleous, D. , Katsoulas, N., and Kittas C. 2019. Irrigation of Greenhouse Crops. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Hakkim, V.M. and Jisha Chand, A.R. 2014. Effect of Drip Irrigation Levels on Yield of Salad Cucumber under Naturally Ventilated Polyhouse. IOSR Journal of Engineering (IOSRJEN), ISSN (e): 2250-3021, ISSN (p): 2278-8719 Vol. 04, Issue 04 (April. 2014), ||V5|| PP 18-21.

- Gadge, S.B.; Gorantiwar, S.D. Yield Response of Drip Irrigated Cucumber to Mulch and Irrigation Regimes under Different Shading Net. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2017, 6 162-167, ISSN: 2319-7706.

- Loveys, B.R. Abscisic acid transport and metabolism in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). New Phytologist 1984, 98, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dry, P. R, Loveys, B.R.; Düring, H. Partial drying of the root-zone of grape. 2. Changes in the pattern of root development. Vitis 2000, 39, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, M.; Loveys, B.; Dry, P. Hormonal changes induced by partial root zone drying of irrigated grapevine. Oxford Journals Life Sciences Journal of Experimental Botany 2000, 51, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar]

| № | Months | Temperature °C | Relative Humidity % | Wind speed at 2 m | Evaporation | vapor pressure mean | Soil Temperature | Radiation | Hour of sunshine | Rainfall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max. | Min | Mean | Max. | Min | Mean | m s−1 | mm | h.pa | °C | Langley day−1 | h day−1 | mm | ||

| 1 | January | 7.4 | 19.8 | 13.9 | 28 | 67 | 48 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 14.9 | 236 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

| 2 | February | 9.8 | 23.2 | 16.8 | 26 | 57 | 39 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 16.8 | 318 | 7.4 | 13.1 |

| 3 | March | 14.4 | 29.3 | 21.2 | 18 | 46 | 34 | 3.3 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 20.3 | 358 | 7.4 | 6.6 |

| 4 | April | 19.7 | 34.6 | 26.5 | 17 | 46 | 31 | 3.5 | 10.6 | 9.2 | 26.0 | 399 | 7.7 | 12.9 |

| 5 | May | 24.9 | 40.1 | 31.6 | 13 | 31 | 21 | 3.4 | 13.6 | 8.0 | 30.4 | 429 | 8.5 | 2.2 |

| 6 | June | 26.7 | 43.0 | 34.1 | 10 | 22 | 15 | 3.3 | 15.1 | 5.9 | 32.5 | 473 | 10.1 | 0.0 |

| 7 | July | 28.1 | 44.0 | 35.4 | 10 | 21 | 14 | 3.3 | 15.2 | 7.2 | 34.2 | 457 | 9.9 | 0.0 |

| 8 | August | 27.8 | 44.3 | 35.1 | 11 | 25 | 17 | 2.9 | 14.3 | 7.4 | 34.7 | 442 | 10.2 | 0.0 |

| 9 | September | 24.3 | 40.9 | 31.7 | 12 | 28 | 19 | 2.5 | 11.7 | 7.1 | 32.6 | 401 | 9.6 | 0.0 |

| 10 | October | 19.0 | 35.6 | 27.0 | 16 | 38 | 25 | 2.2 | 9.0 | 7.5 | 27.1 | 354 | 8.6 | 0.5 |

| 11 | November | 13.8 | 27.8 | 20.8 | 27 | 61 | 40 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 9.2 | 20.0 | 284 | 6.9 | 11.3 |

| 12 | December | 8.3 | 22.4 | 15.7 | 25 | 64 | 47 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 7.7 | 15.6 | 237 | 6.4 | 7.6 |

| (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sample Site № | Bulk Density g.cm−3 | CaCO3 % | O.M% | Sand% | Silt% | Clay% | Soil Texture | (PS%) Soil Saturation P. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1.59 | 17.15 | 0.30 | 89.10 | 5.00 | 5.90 | Loamy Sand | 23.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 1.55 | 17.65 | 0.65 | 81.40 | 11.25 | 7.35 | Loamy Sand | 25.9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 1.57 | 19.40 | 0.75 | 83.20 | 8.75 | 8.05 | Loamy Sand | 25.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (b) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sample Site № | pH | EC (dS m−1) | Cations (meq L−1) | Anions (meq L−1) | SAR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na+1 | K+1 | Ca+2 | Mg+2 | HCO3−1 | Cl−1 | SO4−2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 7.9 | 2.9 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 12.7 | 8.3 | 3.1 | 11.5 | 15.5 | 2.9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 10.0 | 1.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 11.2 | 1.8 | 16.0 | 12.0 | 3.5 | 18.0 | 18.5 | 3.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (c) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sample Site № | N (mg kg−1) | P (mg kg-1) | K (mg kg−1) | Fe (mg kg−1) | Zn (mg kg−1) | Mn (mg kg−1) | Cu (mg kg−1) | Mo (mg kg−1) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 5.5 | 3.2 | 17.3 | 3.689 | 0.582 | 0.845 | 0.189 | 0.409 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 16.3 | 94.0 | 103.0 | 13.440 | 6.348 | 3.299 | 0.951 | 0.475 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 17.3 | 28.5 | 167.5 | 9.588 | 4.532 | 2.942 | 1.370 | 0.421 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (d) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sample Site № | pH | EC (dS m−1) | TDS (ppm) | Cations (meq L−1) | Anions (meq L−1) | NO3-N (ppm) | SAR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na+1 | K+1 | Ca+2 | Mg+2 | HCO3−1 | Cl−1 | SO4−2 | SAR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 7.6 | 1.6 | 1024 | 4.33 | 0.17 | 6.55 | 5 | 3.49 | 5.46 | 6.21 | 19.74 | 1.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 7.67 | 1.5 | 960 | 3.89 | 0.17 | 6.65 | 4.5 | 3.49 | 5.46 | 6.2 | 12.05 | 1.65 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calculation method | greenhouse cucumber seasons | open cucumber seasons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter seasons | Spring seasons | Summar-Autumn seasons | Spring seasons | Autumn seasons | |

| Calculated by evaporation pan method ETc (mm) | 328 | 369 | 493 | 583 | 360 |

| Calculated by penman-monteith equ. ETc (mm) | 417 | 567 | 409 | 625 | 305 |

| Winter seasons | The reference method of calculating evapotranspiration | Automn seasons | The reference method of calculating evapotranspiration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growing Stage | Plant age | Kc (by Epan) | Kc (by PM) | Kc (by Alfalfa R.) | Growing Stage | Plant age | Kc (by Epan) | Kc (by PM) | Kc (by Alfalfa R.) |

| Kc ini. (start) | 1 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.74 | Kc ini. (start) | 1 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.74 |

| Kc ini. (end) | 20 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.74 | Kc ini. (end) | 25 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.74 |

| Kc dev. (start) | 20 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.74 | Kc dev. (start) | 25 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.74 |

| Kc dev. (end) | 50 | 1.67 | 1.65 | 0.98 | Kc dev. (end) | 61 | 1.27 | 1.11 | 1.14 |

| Kc mid. (start) | 50 | 1.67 | 1.65 | 0.98 | Kc mid. (start) | 61 | 1.27 | 1.11 | 1.14 |

| Kc mid. (end) | 80 | 1.67 | 1.65 | 0.98 | Kc mid. (end) | 110 | 1.27 | 1.11 | 1.14 |

| Kc end | 95 | 1.4 | 1.38 | 0.85 | Kc end | 150 | 1.05 | 1.11 | 0.81 |

| RMSE | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0 | RMSE | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0 | ||

| RRMSE | 59 | 59 | 0 | RRMSE | 19 | 14 | 0 | ||

| CRM | -0.54 | -0.55 | 0 | CRM | -0.14 | -0.03 | 0 | ||

| Season | Irrigation level | Final plant length (m) | Final plant height (m) | Cumulative number of leaves | Total leaves | Leaves area (m2) | LAI (2plt/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | 100% | 3.84 | 2.65 | 54 | 54 | 3 | 6 |

| Summer | 75% | 3.77 | 2.65 | 54 | 54 | 2.6 | 5.1 |

| Summer | 50% | 3.19 | 2.65 | 50 | 50 | 1.9 | 3.9 |

| winter | 100% | 4.2 | 2.65 | 59 | 59 | 2.3 | 4.5 |

| winter | 75% | 3.704 | 2.65 | 55 | 55 | 2.1 | 4.2 |

| winter | 50% | 3.704 | 2.65 | 52 | 52 | 1.8 | 3.6 |

| Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) | Added Ware (AW) | Irrigation percentage | PRD with Surface drip Irrigation (PRD-S) | PRD with Subsurface drip Irrigation (PRD-SB) | RDI with Surface drip Irrigation (RDI-S) | RDI with Subsurface drip Irrigation (RDI-SB) | CRM PRD-S | CRM PRD-SB | CRM RDI-S | CRM RDI-SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 328 | 413 | 100% | 14 | 15.5 | 15 | 15.1 | 0.07 | -0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| 328 | 413 | 14.1 | 15.5 | 15.6 | 14.8 | 0.06 | -0.03 | -0.04 | 0.02 | |

| 328 | 413 | 15.2 | 16 | 14.3 | 14.3 | -0.01 | -0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| Mean | 14.4 | 15.6 | 15 | 14.7 | 0.04 | -0.04* | 0 | 0.02 | ||

| 246 | 310 | 75% | 12.6 | 13.6 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.2 | 0.14 |

| 246 | 310 | 12.6 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.13 | |

| 246 | 310 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 13.7 | 0.2 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.09 | |

| Mean | 12.4 | 13.5 | 12.4 | 13.2 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.12 | ||

| 164 | 207 | 50% | 10.8 | 12.5 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.27 |

| 164 | 207 | 10.7 | 11.8 | 10.3 | 11 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.27 | |

| 164 | 207 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 11.1 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.3 | 0.26 | |

| Mean | 10.9 | 12 | 10.5 | 11 | 0.27 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.27 | ||

| 328 | 620 | 150% | 13.4 | 13.9 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 328 | 620 | 13.7 | 14.2 | 14.7 | 14.5 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| 328 | 620 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 15 | 14.5 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.03 | |

| Mean | 13.5 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 14.4 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) | Added Ware (AW) | Irrigation percentage | PRD with Surface drip Irrigation (PRD-S) | PRD with Subsurface drip Irrigation (PRD-SB) | RDI with Surface drip Irrigation (RDI-S) | RDI with Subsurface drip Irrigation (RDI-SB) | CRM PRD-S | CRM PRD-SB | CRM RDI-S | CRM RDI-SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 493 | 621 | 100% | 15.8 | 16.2 | 16.94 | 17.2 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0 | -0.02 |

| 493 | 621 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 16.57 | 16.9 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0 | -0.02 | |

| 493 | 621 | 15.5 | 16.7 | 16.19 | 16.6 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0 | -0.03 | |

| Mean | 15.7 | 16.4 | 16.57 | 16.9 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0 | -0.02* | ||

| 370 | 466 | 75% | 15.4 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 16.7 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| 370 | 466 | 14.7 | 15.5 | 15.7 | 16.2 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |

| 370 | 466 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.02 | -0.01 | |

| Mean | 14.8 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 16.4 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | ||

| 247 | 311 | 50% | 13 | 14 | 13.2 | 14.8 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

| 247 | 311 | 12 | 13.7 | 13 | 14.6 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.12 | |

| 247 | 311 | 11.9 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 14.7 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.09 | |

| Mean | 12.3 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 14.7 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.11 | ||

| 493 | 932 | 150% | 15.3 | 16 | 16.5 | 16.2 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| 493 | 932 | 16.9 | 16.8 | 16.3 | 16.4 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| 493 | 932 | 15.7 | 15.5 | 16.6 | 16.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0 | |

| Mean | 16.0 | 16.1 | 16.5 | 16.2 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) | Added Ware (AW) | Irrigation percentage | PRD with Surface drip Irrigation (PRD-S) | PRD with Subsurface drip Irrigation (PRD-SB) | RDI with Surface drip Irrigation (RDI-S) | RDI with Subsurface drip Irrigation (RDI-SB) | CRM PRD-S | CRM PRD-SB | CRM RDI-S | CRM RDI-SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 583 | 734 | 100% | 7.20 | 8.70 | 7.20 | 7.40 | 0.00 | -0.21 | 0.00 | -0.03 |

| 583 | 734 | 6.80 | 8.80 | 6.70 | 7.30 | -0.01 | -0.31 | 0.00 | -0.09 | |

| 583 | 734 | 6.70 | 8.20 | 6.60 | 7.00 | -0.02 | -0.24 | 0.00 | -0.06 | |

| Mean | 6.90 | 8.57 | 6.83 | 7.23 | -0.01 | -0.25 | 0.00 | -0.06 | ||

| 437 | 551 | 75% | 6.50 | 7.40 | 6.30 | 7.20 | 0.10 | -0.03 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| 437 | 551 | 6.30 | 7.30 | 5.80 | 6.90 | 0.06 | -0.09 | 0.13 | -0.03 | |

| 437 | 551 | 6.20 | 7.20 | 5.80 | 7.40 | 0.06 | -0.09 | 0.12 | -0.12 | |

| Mean | 6.33 | 7.30 | 5.97 | 7.17 | 0.07 | -0.07 | 0.13 | -0.05 | ||

| 291 | 367 | 50% | 5.10 | 5.30 | 5.00 | 5.40 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| 291 | 367 | 5.30 | 5.80 | 5.00 | 5.50 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.18 | |

| 291 | 367 | 4.70 | 6.50 | 4.60 | 6.00 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.09 | |

| Mean | 5.03 | 5.87 | 4.87 | 5.63 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.18 | ||

| 583 | 1102 | 150% | 7.10 | 6.70 | 5.10 | 6.60 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.08 |

| 583 | 1102 | 7.10 | 6.80 | 5.10 | 6.10 | -0.06 | -0.01 | 0.24 | 0.09 | |

| 583 | 1102 | 7.00 | 9.20 | 6.70 | 6.80 | -0.06 | -0.39 | -0.02 | -0.03 | |

| Mean | 7.07 | 7.57 | 5.63 | 6.50 | -0.03 | -0.11 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).