1. Introduction

The global water resource limitation crisis has attracted interest in increasing the efficiency of using and rationalizing these limited water resources, especially the water used in agricultural irrigation, in order to increase production and achieve and provide many crops in drought-prone and densely populated areas. Agricultural sectors are under intense pressure to rationalize and reduce the use of freshwater intended for irrigation and use it for farming in other areas [

1,

2]. Water scarcity is a very serious problem and is considered a challenge to food production in dry areas. It is crucial to cut back on water use and conserve irrigation water by modernizing and developing all sustainable and innovative technologies [

3]. Increasing crop productivity from a unit of irrigation water is a major and necessary objective to increase the demand and the increasing need for food at a rate parallel to the turbulent rise in the population growth rate [

4,

5]. The adoption and application of all techniques of modern irrigation methods systems and other related complementary techniques are very important that must be followed and applied in order to supply a significant portion of irrigation water in arid and semi-arid areas that can be used in the cultivation of another area and to obtain additional agricultural production to participate in the dam The required nutritional gap[

1].

The issue of drought is one of the most important and dangerous climatic issues that are sure to have a negative impact on agricultural production. For high and successful production in dry climates, many agricultural crops need additional irrigation and huge amounts of irrigation water [

6]. Therefore, adapting, developing and optimizing new irrigation technologies is absolutely necessary for the accurate and efficient use of irrigation water in light of combating water scarcity scenarios with current and future climate change [

7].

A cutting-edge technique for trace irrigation, partial root-zone drying (PRD) divides the crop's root zone into two sections. Basically, this method entails irrigating about half of the plant or tree's root zone while leaving the other half to dry. Then, after a set amount of time, the dry half of the root zone is watered, and the previously irrigated half is allowed to dry [

8]. In order to prevent a scarcity of water and preserve the state of the plant water in the plant buds, the irrigated half simultaneously distributes water to the buds [

9]. An irrigation technique known as PRD involves periodically moistening and drying plant roots or trees in order to maintain increased plant growth naturally and with less water[

8]. Through osmotic modulation, inadequate irrigation techniques and methods, such as PRD, promote plant drought tolerance. Previous studies have demonstrated that PRD is superior to standard insufficient irrigation when the same amount of water is used in both treatments. It has been shown that the production of antioxidants and osmotic modification in the framework of PRD increase crops' tolerance and drought tolerance and yield [

10]. To increase water productivity (WP), irrigation technologies that utilise less water are used. Important irrigation water-saving techniques like DI and PRD lower crops' irrigation needs without dramatically lowering yield.

In order to simultaneously maintain the plant's water condition with maximum water potential and manage the vegetative growth of certain areas of the seasonal cycle of plant development, the PRD technique is used to alternately irrigate two parts of the plant's root system [

11]. In addition, PRD is one of the most important environmentally friendly irrigation strategies through which it can reduce the leakage of pollutants into the environment in the future [

12]. Plants and crops that use half-root drying systems typically interchange portions of the plant root system that are permitted to dry out in response to biochemical signals and physiological reactions. In this method, the dry half emits hormones, which are then carried to the plant's buds through the xylem arteries and cause the stomata to close partially, reducing the transpiration rate [

13]. Higher CO

2 concentrations in combination with water scarcity will be an additional challenge for PRD in practice as PRD can be used in different ways depending on the crops grown and/or soil and environmental conditions, irrigation method, and future predictions in climate change scenarios that have included an increase in greenhouse gas volume.

Recent testing of the precision of PRD irrigation with numerous agricultural crops worldwide revealed savings of 30–50% of irrigation water with the application of PRD technique without a significant decrease in crop yield compared to the traditional full irrigation method (FI). In addition, many studies and research have been conducted, which indicate and confirm the benefits of PRD technology for fruit trees on oranges[

2,

14], pear [

15], apple [

16], olive [

17], citrus[

18]; [

19], pear [

15] and pomegranate [

20,

21,

22]. Additionally, he discovered a dearth of studies examining the impact of PRD on mango productivity and quality [

23]. Agriculture water supplies are being depleted and used due to global climate change and pollution. Yet, cultivated plants have developed specialised defence mechanisms that boost their tolerance to harsh environments[

24]. The best and easiest way to manage water use on the farm is the combination of two economical techniques (coverage and PRD) that can be a better way and method to combat drought stress [

25].

Mulch is a versatile application material that serves a variety of purposes for soil and plants, including increasing soil infiltration, lowering water runoff, lowering evaporation losses, and inhibiting weed growth[

25]. The organic cover is more beneficial compared to the black plastic cover[

26]. Mulching enhances plant growth when water is lacking by preserving the leaf's water balance and turning on antioxidant enzymes [

27]. By minimising evaporation and transpiration (by controlling weeds), covering increases water intrusion while decreasing water loss. The selection and use of appropriate mulch is one of the good methods for soil moisture conservation and sustainable crop production that must be investigated more and more in order to determine the impacts of mulch on cultivated land throughout the short and long term [

28].

Due to its vibrant colour, distinct flavour, and nutritional content, mango is a highly prized fruit worldwide. The fruiting characteristics (number of fruits, weight of fruits, etc.), which were considerably impacted by irrigation levels, show that the harvested mango yield was higher utilising the drip irrigation technology [

29].

Few researchers have examined the use of OM application and PRD irrigation technology together for mango production in arid environments. Therefore, the research must investigate the combined effects of PRD with the use of organic mulching to mango production in order to give farmers and agricultural stakeholders the knowledge needed to adapt strategies for water productivity effectively. Consequently, this study aimed to pinpoint the most effective irrigation techniques using sustainable materials (organic mulch) that would increase yield and water productivity of mango fruits and increase the soil organic matter content in arid environmental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Climate of the Experimental Site

Field experiments were carried out on mango trees for a private farm for two years, 2020/2021 to 2021/2022 under Areas with sandy soils with hot summers, cold winters, and rainy winters. Regarding the central areas, their winters are cold and dry, and their summers are torrid. The chosen area experiences chilly winters and scorching, dry summers due to its dry climate, and the average air temperatures were 22.74 and 23.8, with average air relative humidity of 65.3 and 67.9%, for two seasons 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively.

Aspects of soil's physical and chemical makeup and irrigation water: The water source for irrigation was a groundwater well that passed across the experimental area and had an average pH of 7.6 and an electrical conductivity (EC) of 2.55 dS m

-1. At the start of the experiment, the soil's significant physical and chemical characteristics were identified, as given in

Table 1 on-site and in a lab. Soil samples had been taken from depths (0-40, 40-80 and 80-120 cm) at the start of the experiment, and analyzed for physical and chemical properties.

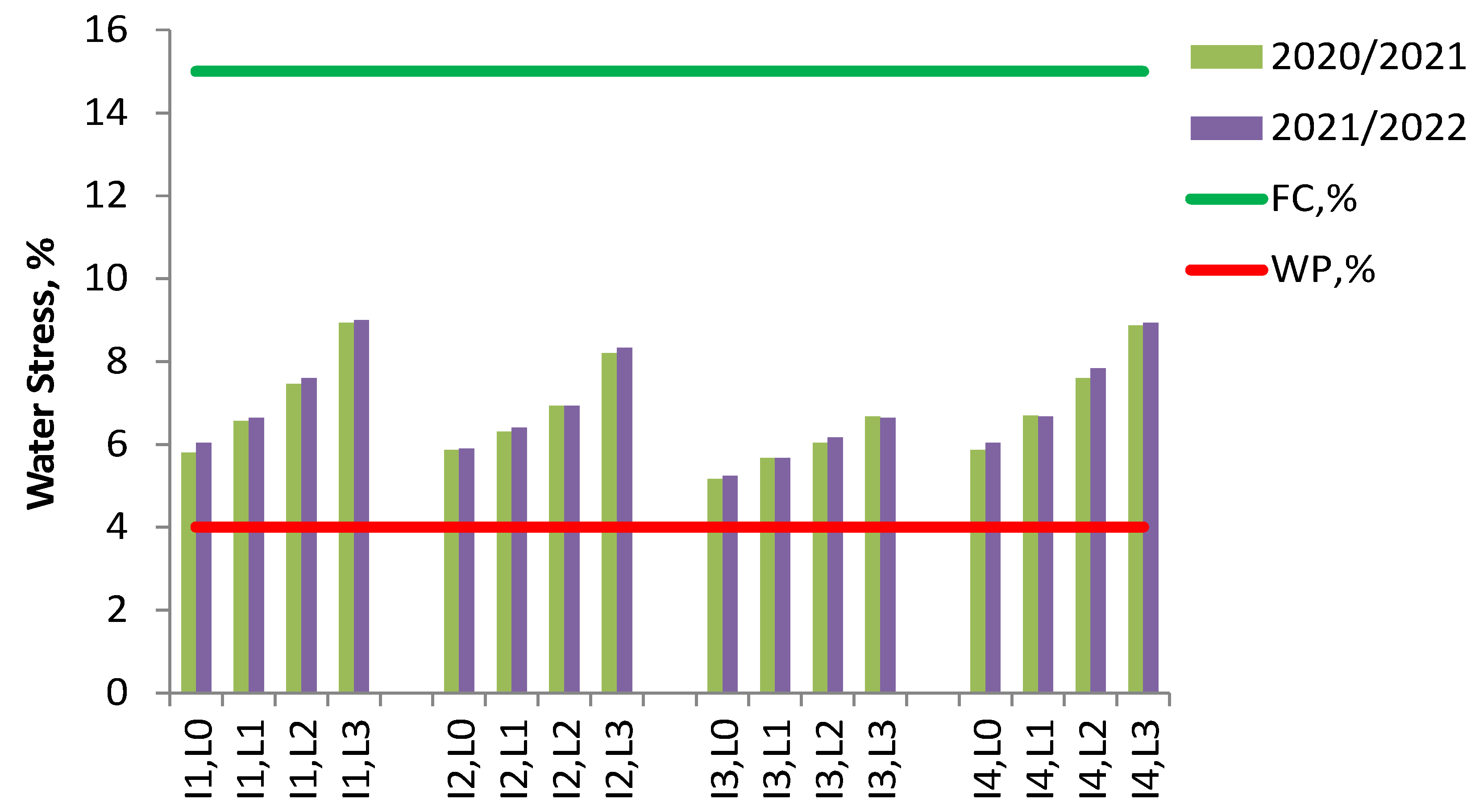

Experimental design: Three replicates were used in the split-plot design for the experimental setup. Four irrigation strategies [I1(100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 ( PRD (50% FI)] were assigned as main plots. Each main plot was then divided into sub main plots subjected to four cases for soil organic mulch as a sustainable material [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch)]. One layer of shredded agricultural waste which was equivalent to 6.7 t ha

-1 was used. The means of these two trees were employed for statistical analysis, and each treatment was reproduced three times with two trees per replicate, as shown in

Figure 1.

Irrigation system description: Pumping, a filtration unit, and a control head made up the irrigation system. It is made up of an electrically powered submersible pump with a 45 m3/h discharge, control valves, a screen filter, a flow metre, pressure gauges, a pressure regulator, and a backflow prevention system. Through a 2" control valve and discharge gauge, manifold lines with a diameter of 63 mm were formed of polyethylene pipes and connected to the laterals. Emitters were constructed in the laterals and had a diameter of 16 mm and a length of 60 m. At an operating pressure of 1.0 bar, the emitter discharge was 6 litres per hour.

Irrigation requirements for mango: Equation (1) was used for measuring daily irrigation water and for 100% full irrigation "FI" during seasons 2020–2021 and 2021–2022, the seasonal irrigation water was 10080 and 10,000 m3/ha./season, respectively., using drip irrigation system. Because the volume of rainfall was so small and the duration was only a few minutes, there was no rainfall that was included across the two seasons. For the irrigation period, FI got the necessary irrigation volume to satisfy the crops' evapotranspiration needs.

where IRg represents the daily gross irrigation needs (mm); Evapotranspiration reference (mm/day); Kc stands for "FAO-56" crop factor, Kr for "ground cover reduction factor," and Ei for "irrigation efficiency (%)." R is the quantity of water a plant receives from sources other than irrigation (in millimetres), such as rainfall, and LR (leaching requirements) is the amount of water required for salt leaching (in millimetres).

Mango trees: Regardless of the experimental treatments, all experimental plots were treated by the normal and recommended mango growing requirements (Cucumis sativus L.) as recommended by the instructions of the official agricultural bulletins. Mango trees that were 10 years old and spaced at 3 x 5 m, with an average of 600 trees per hectare, were used in the study. All fieldwork was completed per local recommendations, using the same fertilisation (240 kg N, 71 kg P2O5, and 212 kg K2O) and standard cultivation methods for disease and pest management. Fertigation was attributed to the application of nutrient solution via irrigation water. All field practices were done as usually recommended for mango cultivation in the sandy soils.

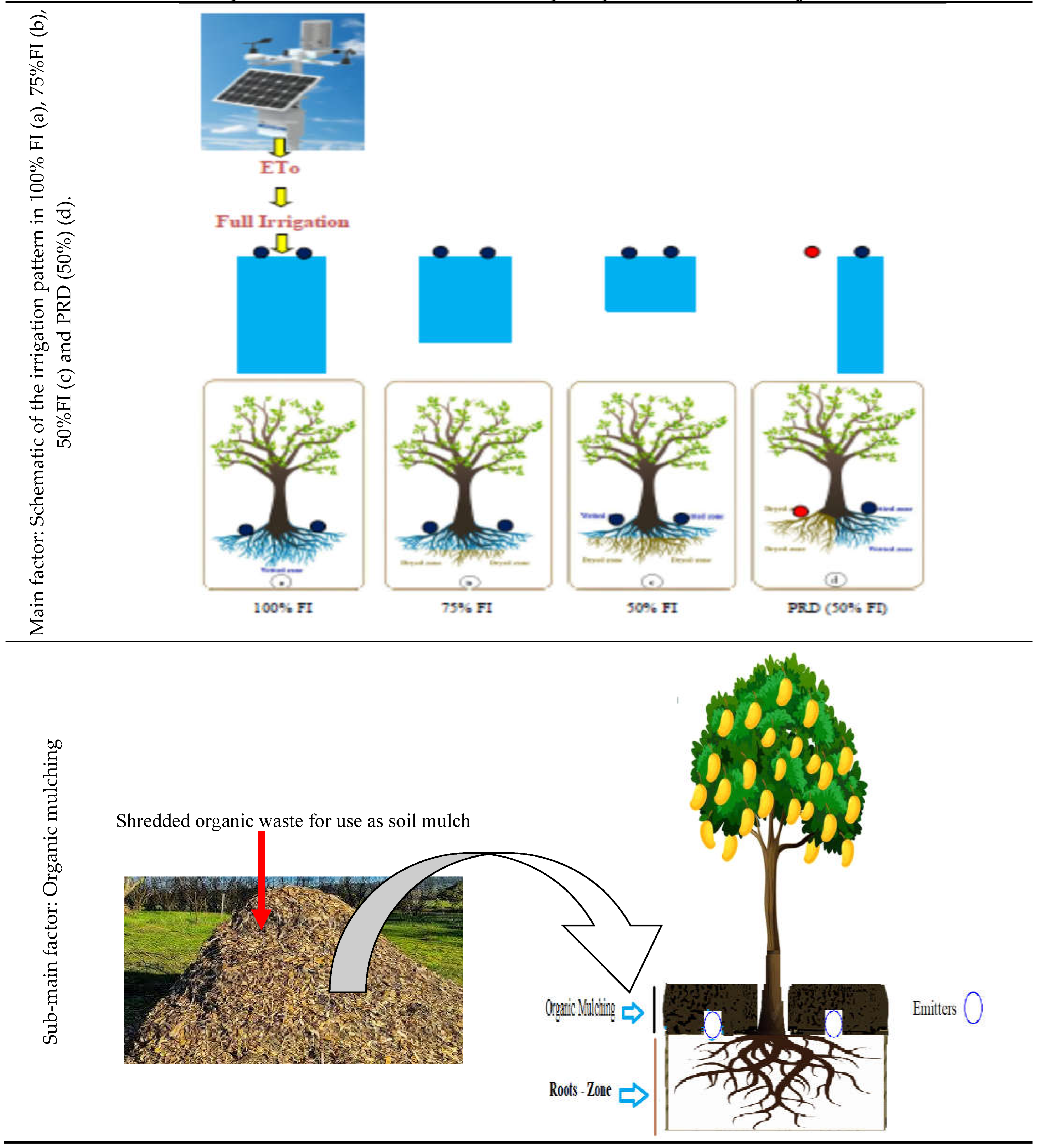

Water stress inside root-zone: Prior to watering, the effective roots zone's soil moisture content was measured. According to Abdelraouf et al., field capacity and wilting point were taken into account as evaluation metrics for the exposure range of plants to water stress. [

2]. Using a profile probe equipment, soil moisture content measurements were determined. Field capacity (FC) water contents were 15%, and permanent wilting point (PWP) water contents were 4%.

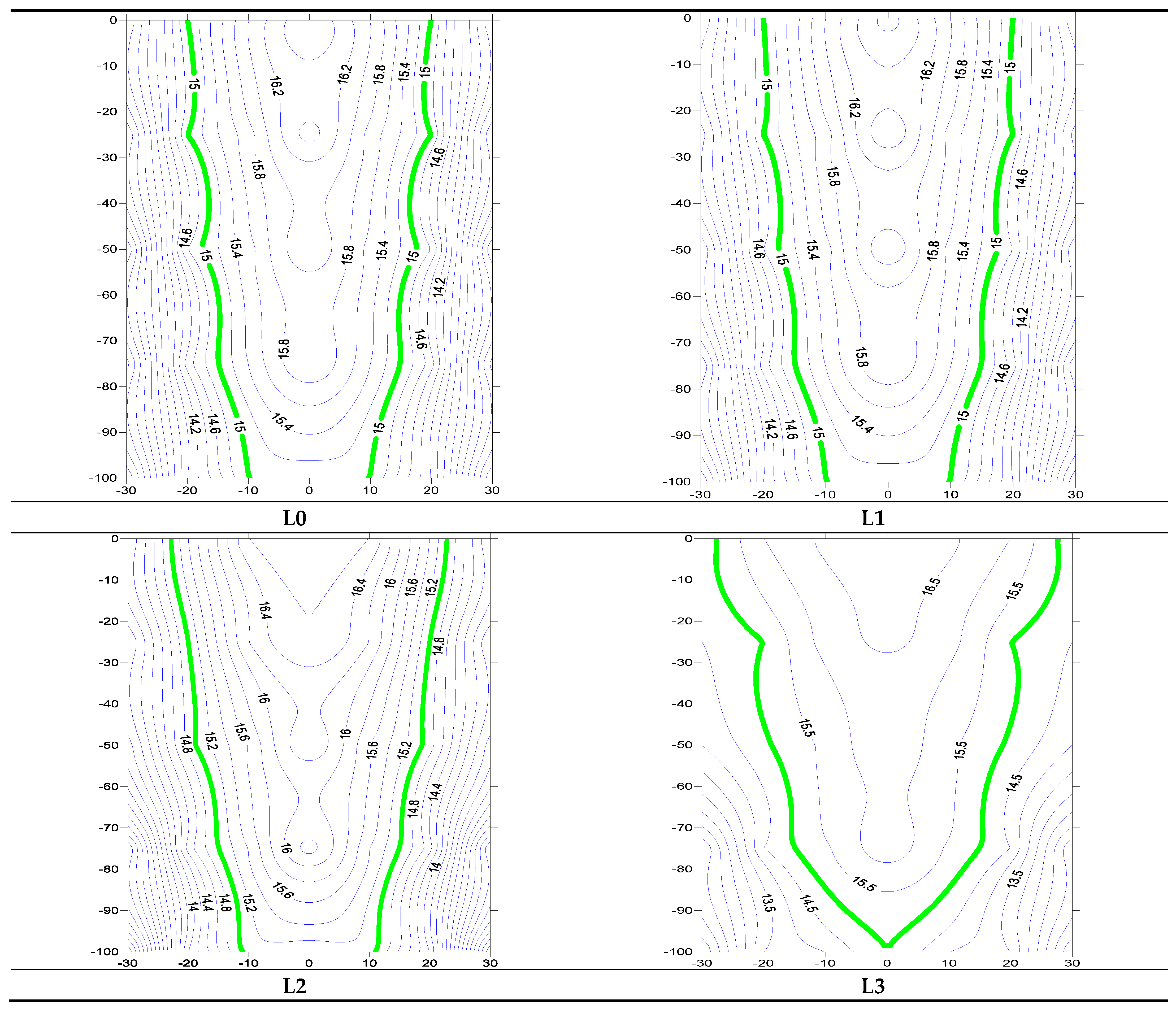

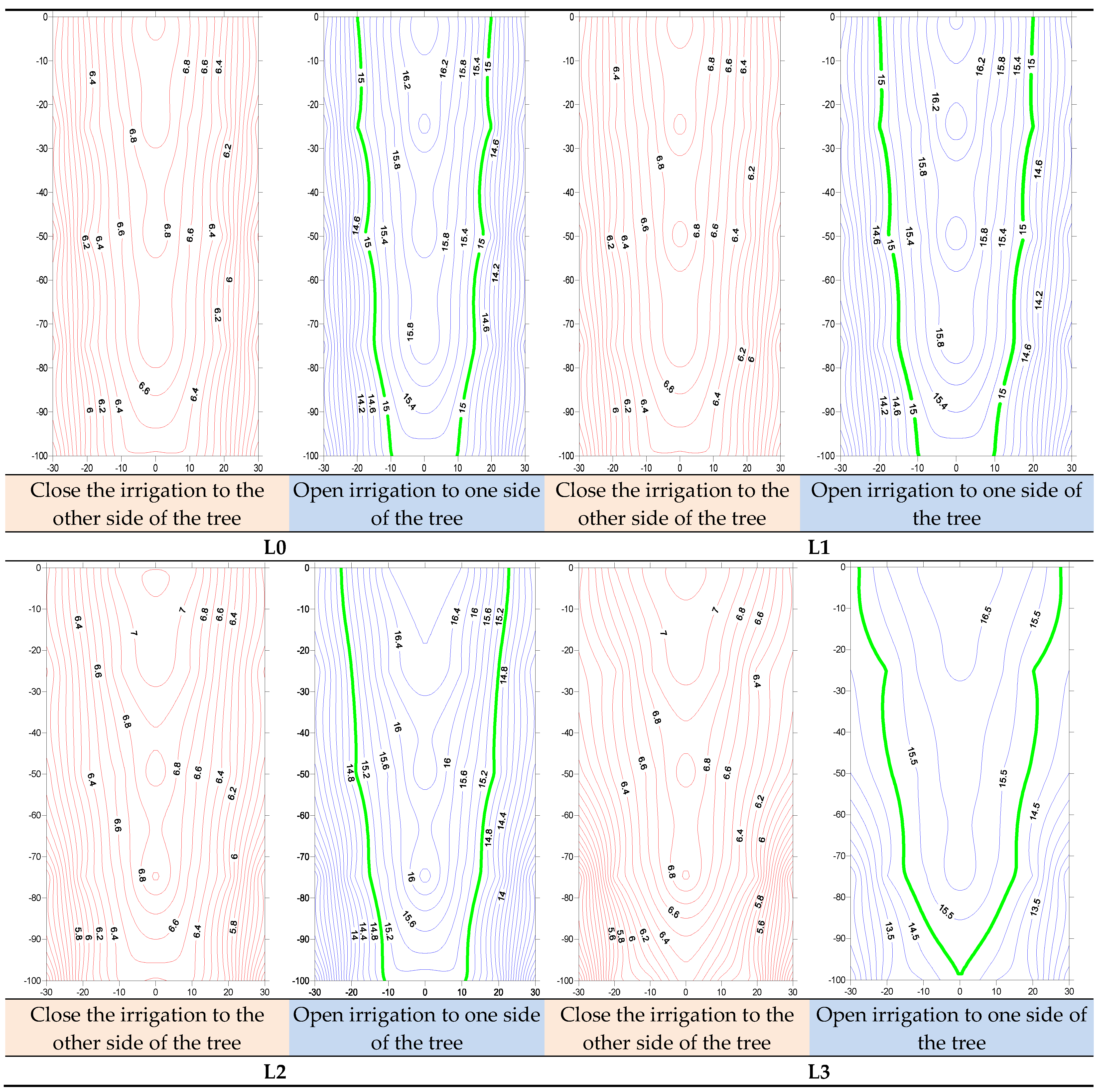

Soil moisture distribution: By monitoring soil moisture content using a profile probe device at maximum actual water demand, two hours after irrigation, and at various sites, the distribution of soil moisture was identified. Locations were obtained at 0, 10, 20, and 30 centimetres on the X-axis and at 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100 centimetres on the Z-axis (in the direction of the depth of the dirt down). The contouring map for various soil moisture levels with the depths for all treatments can be obtained using the Surfer 13 Golden software programme, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Salt accumulation in root-zone: In the effective roots zone, the concentration of soil salts was determined both at the start and after the end of the season.

Soil organic matter content: Measuring the soil organic matter content in the root zone in response to the various sustainable materials (organic mulch) under irrigation strategies were investigated as an indicator of nutritional status for mango trees.

Yield of mango: At harvest time in August, numbers of fruits per tree (tree load) Fruit yield was determined as kg per tree for each treatment after the samples were gathered, weighed, and counted. After conversion, the total yield in tonnes per hectare was calculated.

Water productivity of mango "WPmango": According to James (1988), WP

mango was determined by Equation (2) as follows:

where, WP

mango is water productivity of the mango crop (kg

mango/m

3water); Ey is economical yield (kg/ha.); and Ir is applied volume of the irrigation water (m

3water /ha./season).

Mango fruit quality: In order to measure some of the quality parameters of mango fruits, such as the total soluble solids, T.S.S., using a Carl Zeiss hand refractometer in accordance with Singh (1988), the total Acidity of fruit juice estimated as g citric acid/100 ml juice, and Vitamin C (mg/100 ml juice), determined in accordance with A.O.A.C., representative samples of mango were randomly selected from each treatment. [

30].

Energy consumption: Energy consumption was determined for the tested variables by the following equation:

BP stands for brake power (kW), Q for discharge (m3/sec), etc. Total dynamic head (m), or TDH; Pump effectiveness (%) in EP; YW: (9.81 kN/m3) Water specific weight; Efficiency of electric engines (%), or Ei.

Statistical Analysis: According to Snedecor and Cochran, all the data collected during the two research seasons were statistically analysed using the conventional analysis of variance procedure (ANOVA) of split plot design with three replications [

31]. The statistical programme CoStat (Version 6.303, CoHort, USA, 1998-2004) was used to process all the data. Using least significant differences (LSD) tests to compare treatment means of the measured parameters, differences were deemed significant at p 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

Water stress in the root-zone

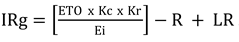

Considering data related to water stress in root-zone for both treatments of irrigation strategies and sustainable materials (organic mulch) for the two seasons presented in

Figure 2. It shows general reduction in water stress within the root zone area using organic mulch under all irrigation strategies treatments, and this was inferred by the approximate moisture content of field capacity and spacing from the permanent wilt point. The lowest water stress value was reported in I1 and PRD (I4) strategy with using OM (L3) while the highest value was at I3+L0 for the two seasons. Mulches reflect sunlight, reduce evaporation losses, and improve soil moisture content compared to bare soil, reducing water stress reactions [

13]. Water stress typically lowers a plant's ability for photosynthesis, which affects the rate of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance as well as the creation of matter and plant yield [

32]. These findings concur with those of Abdelraouf et al.[

2], [

4].

Figure 3.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the water stress in root-zone [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD :50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 3.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the water stress in root-zone [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD :50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Soil moisture distribution

The measurement of soil moisture distribution under the drip system on both sides of the mango tree is one of the most important measurements that highlight and clarify the importance of using organic mulching with the partial root–zone drying technique as one of the most important techniques for sustainable management of irrigation deficit and shortage of water resources.

Figure 4 indicates the soil moisture distribution under 100% full irrigation with different layers of organic soil mulch. It has been observed that by increasing the number of layers of soil organic mulch, the horizontal movement of water increased compared to the vertical movement, which led to an increase in the volume of water stored in the root-zone spread and a decrease in water stress in the area of root spread. This might be due to the slower rate of water evaporation from the wet soil's surface caused by adding more layers of organic mulch.

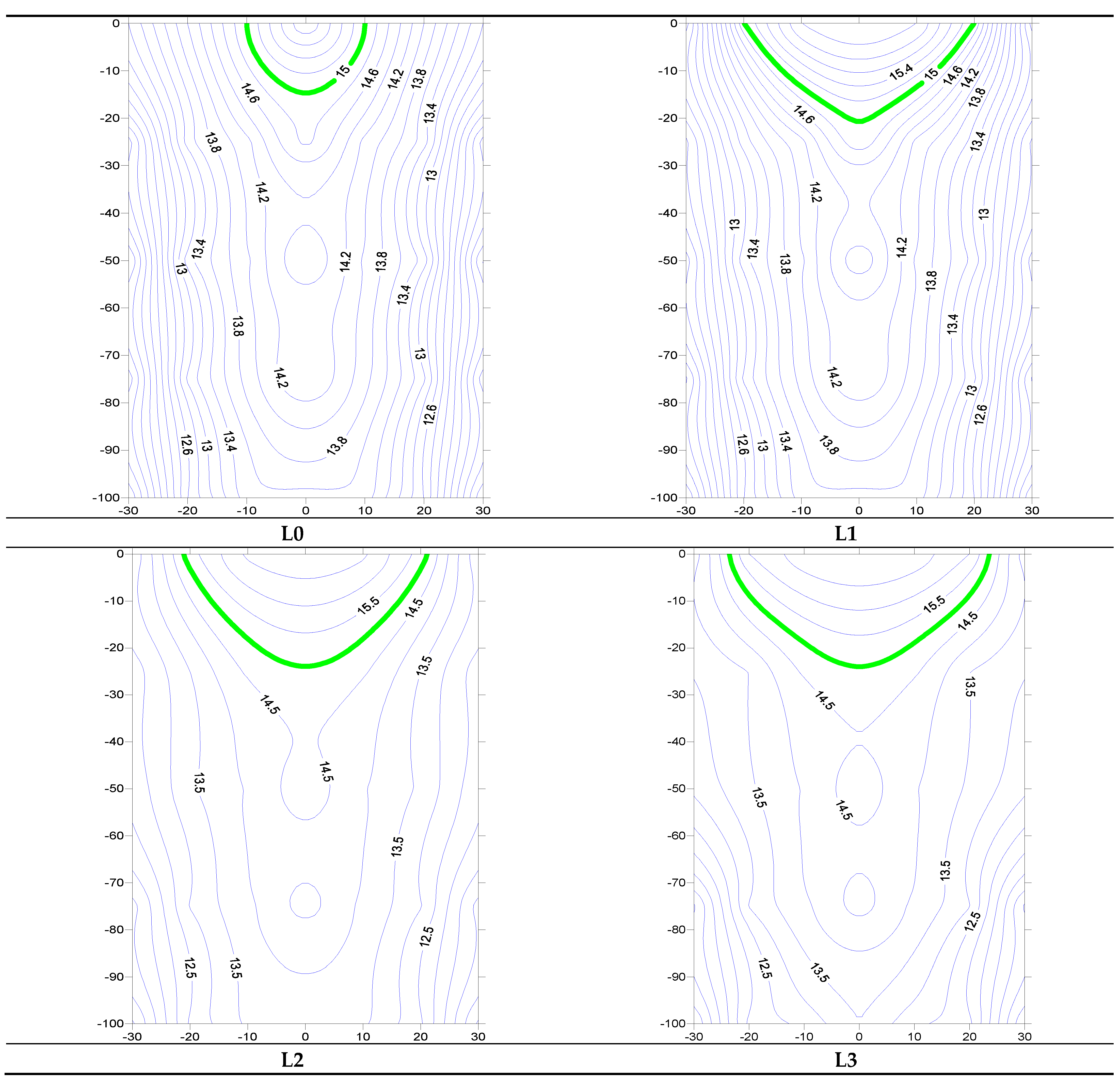

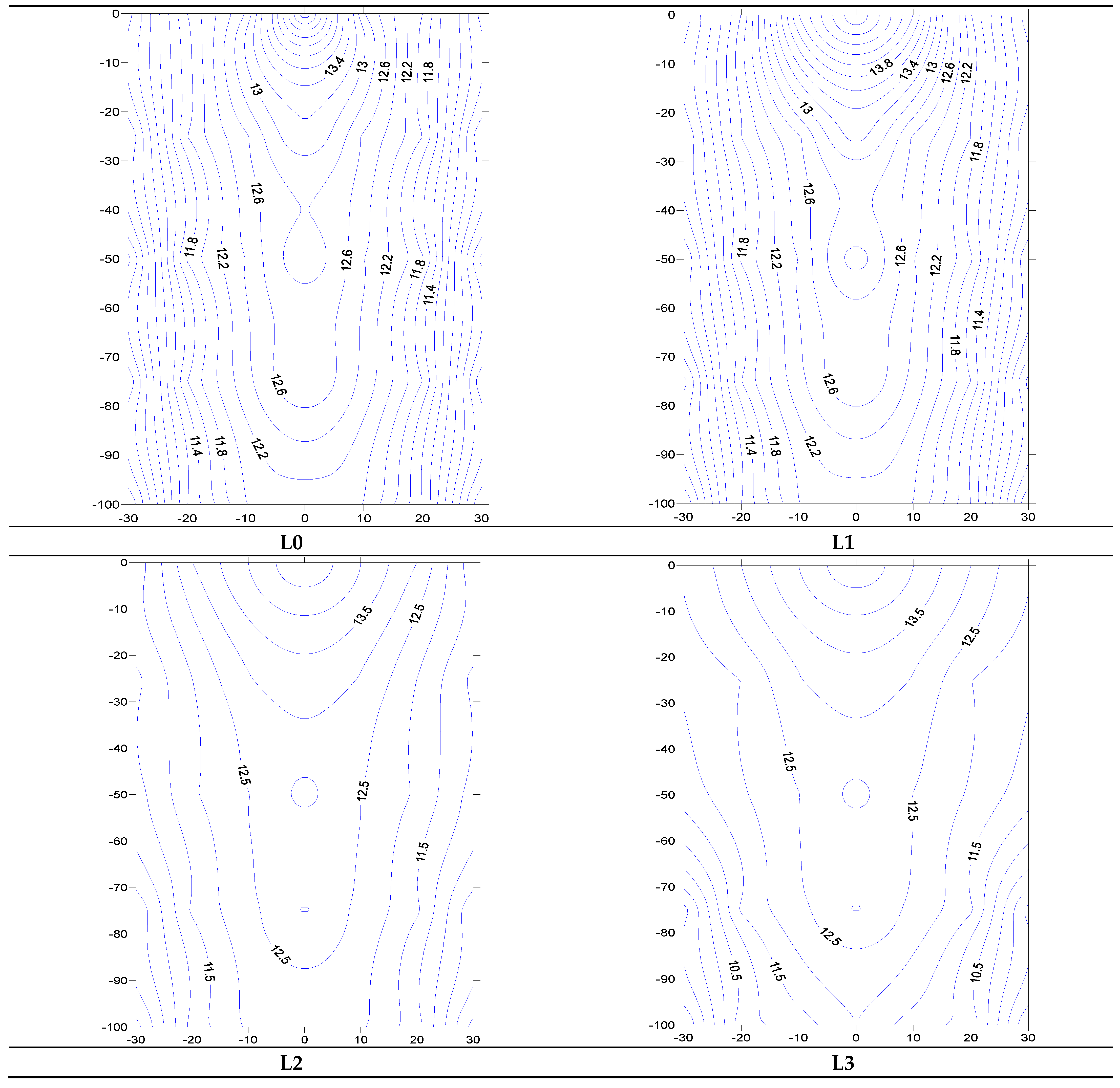

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 confirm that there is a noticeable effect of the organic mulching and its increase in relieving soil moisture stress within the root spread area of mango trees, where the soil moisture distribution improved with an increase in the number of organic mulching compared to no mulching.

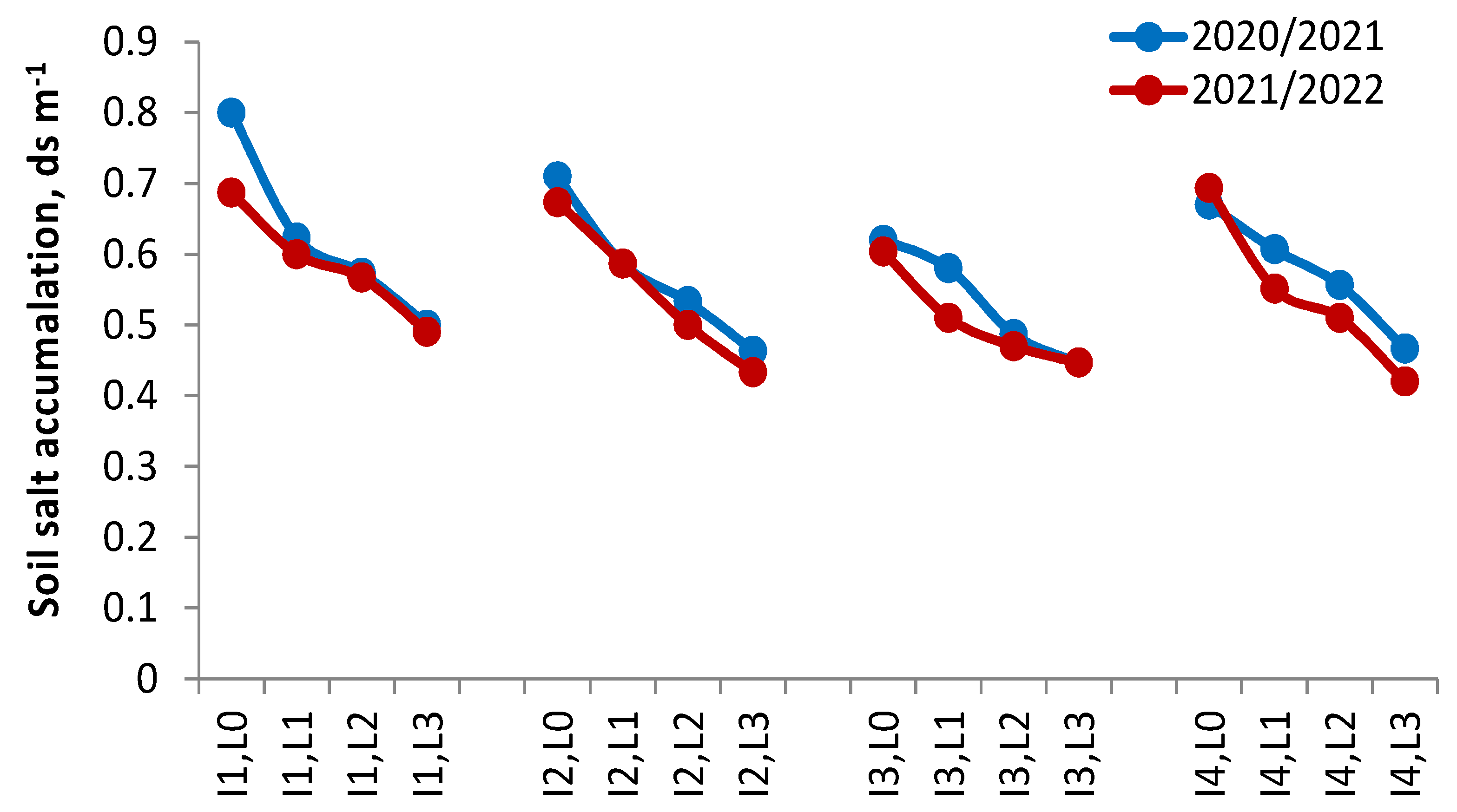

Salt accumulation

Figure 3 illustrates how organic mulching and watering techniques affect salt buildup in the root zone.

Figure 8 illustrates how covering the soil's surface with organic mulch can help to reduce the accumulation of salt in the area of root spreading under all irrigation strategies treatments for the two seasons. The largest amount of soil salts accumulation was in the soil at L0 and when adding I1, while the lowest amount of soil salts accumulation was when using L3 under PRD technique for the two seasons. This might be as a result of the organic mulch layers' ability to slow the rate of evaporation, which in turn prevents salt from building up in the root zone. The fundamental reason for higher salt concentrations in stressful situations is the breakdown of bigger molecules into smaller ones, which causes the osmotic potential to reach its maximum value. [

10].

These observations support those made by Abdelraouf and Ragab [

4], who demonstrated through field and modelling results that salinity was lower for 100% FI, 75% IF, and 50% IF treatments than when applying PRD. However, under the same treatments with mulch, the observed and simulated soil salinity was lower than those without mulch. To save fresh water and lower salt concentration in the root zone of plants, they also suggested employing PRD under a localised drip system while applying organic mulch as a smart irrigation management practise. The same conclusions were put out by [

33], who reported that salt concentration was higher under conditions of extreme water stress than it was during full irrigation.

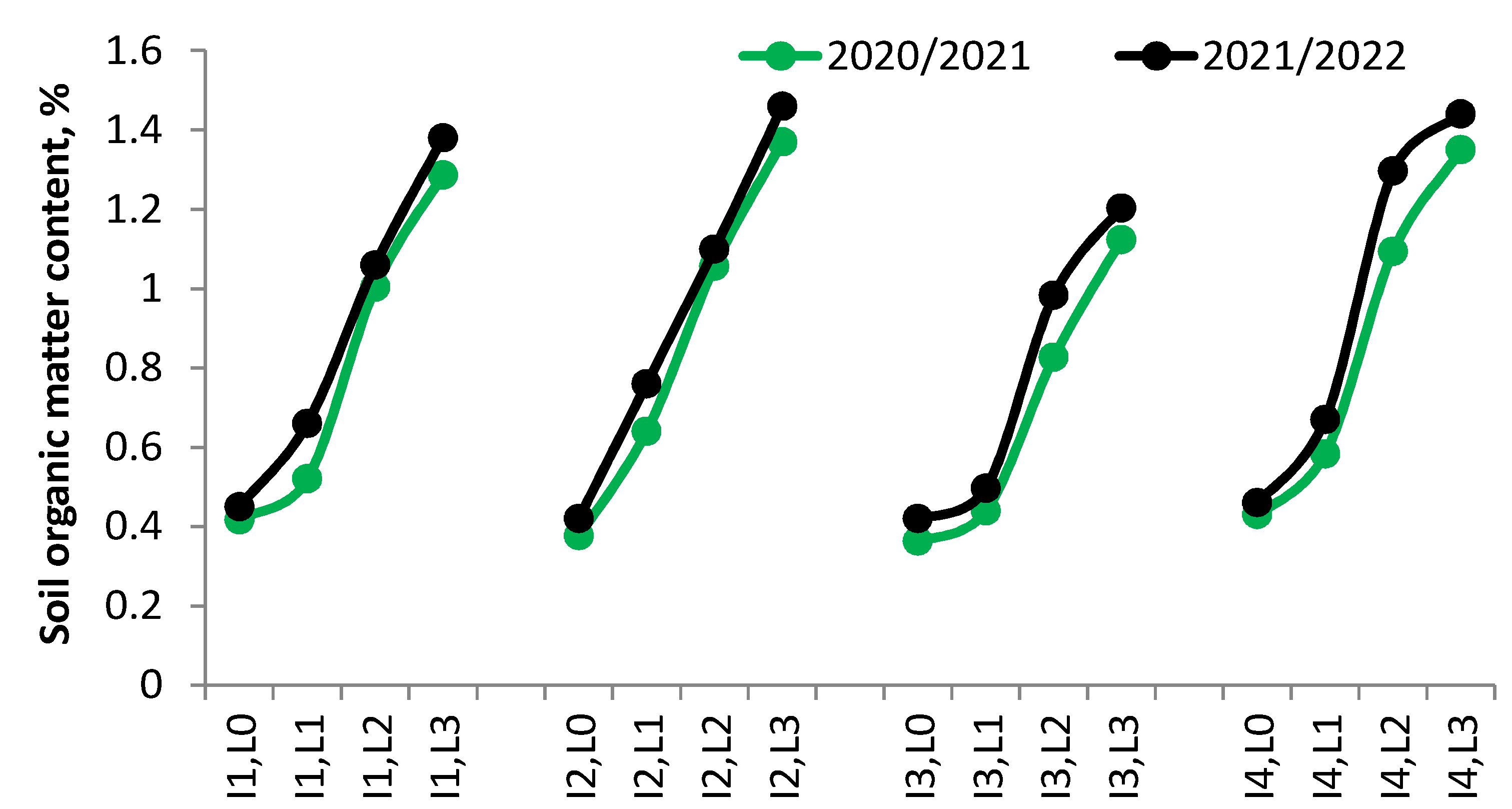

Soil organic matter content

The nutritional status of the soil was tested by measuring the soil organic matter content for all treatments under study during the two seasons.

Figure 9 illustrates the importance of organic mulching under all irrigation strategies for increasing soil organic matter content. Organic matter content was increased by increasing the number of organic mulching. This may be due to two reasons. The first is because of the organic coverage and with the increase in the number of its layers, where the rate of decomposition of the organic matter in the area of root spread decreased as a result of the decrease in soil temperatures with the increase in the moisture content. The second is to chop the organic covers and mix them with sandy soil after the end of the harvest season, which led to an increase in the addition of organic content within the sandy soil. Mulch improves soil organic matter and moisture levels for healthy root development, increasing the soil's capacity to store water [

34]. This investigation was carried out on roselle plants (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) at the Experimental Farm of the Faculty of Agriculture in May throughout the two seasons of 2008 and 2009. The goal was to determine how the application of amino acids, humic acids, and microelements affected the vegetative growth, yield characteristics, and antioxidant activity of plants grown in various organic and inorganic media conditions. The findings revealed a high degree of resemblance, which had been observed with the bulk of the characters studied in both seasons. In comparison to the other treatments, the plants that were grown in soil that contained compost or magnetic iron and was humic acid-sprayed produced the highest values for plant height, number of branches per plant, stem diameter, fresh and dry weights of leaves and branches per plant, number of days until flowering, number of fruits per plant, fresh and dry weights of sepals per plant, and seed yield per plant. It may be concluded that the values of the previous characters were higher with the first treatment than with the second in both seasons when compost plus humic acid was applied compared to magnetic iron plus humic acid. Although these values were still greater than those of the compost or a single magnetic iron or those of the control treatments in both seasons, the lowest character values were consistently seen with the mixture of compost or magnetic iron with amino acids or with microelements. Plants treated with compost and humic acid showed the best DPPH radical scavenging activity, which was associated with the overall anthocyanin content. [

30]. The highest soil organic matter content was indicated in PRD+L3, while the lowest content was under I3+L0 for the two seasons.

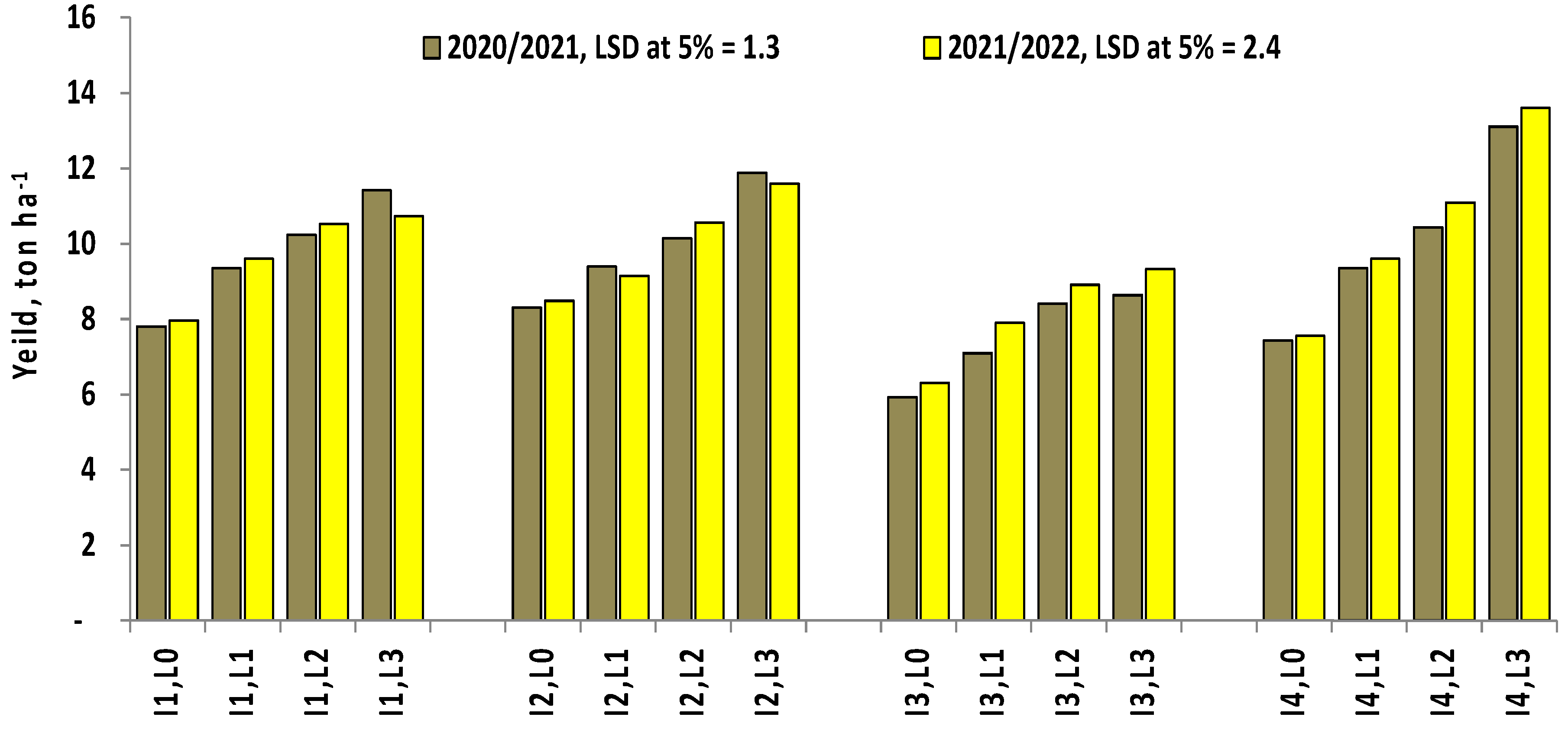

Mango Yield

When analyzing the factors separately, the first factor (irrigation strategies) had a positive and significant effect on mango yield, which was also significantly affected by the second factor (sustainable materials "organic mulch t") for the two seasons as represented in

Table 3. The highest yield values for the irrigation strategies treatments were under I4 (PRD), followed by I2 and then I1, while the lowest yield values were under I3 for the two seasons. Using I4 (PRD), the greatest mango yields for 2020–2021 and 2021–2022, respectively, were 10.080 and 10.466 tonnes per hectare and there are no-significant deference between using I4 (PRD), I2 and I1 on mango yield. But there are significant difference between using I3 and other treatments, while the lowest values of mango yield were 9.705 and 9.706 ton ha

-1 occurred by using I3 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. The rationale was that under PRD, the soil water in the root system's moist portion would evaporate earlier due to increasing atmospheric demand. With the same amount of water applied, some field experiments contrasted PRD and DI and found that PRD vines significantly increased crop production. According to Shahabian et al. (2012), DI treatments decreased fruit yields for orange trees by 30% when compared to I1. However PRD treatments had no effect on fruit yields. Furthermore, Hutton and Loveys [

19] demonstrated that PRD had no impact on citrus plants' fruit yields. For sustainable materials (organic mulch) treatments, more mango yield were recorded by increasing the number of organic mulching layers, and there are significant difference between using OM and other treatments. While the minimum yield (7.369 and 7.577 ton ha

-1) were recorded in L0 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. Due to increased growth, faster photosynthetic rates, improved soil moisture retention, and overall higher yield characteristics compared to other treatments, the OM treatment produced more mango yield. Raza et al. [

10] made similar observations and discovered that mulching improved stomatal conductance in plants as a result of increased soil moisture availability and preservation of leaf turgor, which keeps the stomata open.

As shown in

Figure 10 and

Table 2, the interaction between the two parameters also had a statistically significant impact on mango yield for the two seasons. The highest values of mango yield were 13.103 and 13.612 ton ha

-1 occurred under applying PRD with using L3 during 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. There are no-significant deference between applying PRD+L3 and I3+L3, but there are significant difference between using these conditions and other treatments, while the lowest values of mango yield were 5.9 and 6.3 ton ha

-1 occurred by applying I3 under L0 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. Observing a good effect of PRD with OM while observing a negative impact on the yield when irrigation water is reduced under deficit irrigation may be attributable to three factors: First, let's talk about the positive effects of the PRD strategy. PRD involves alternately watering both sides of a plant's root system, and this strategy causes a mild water stress in the plant, which causes some stomata to partially close and reduce transpiration losses without significantly affecting photosynthesis or yield. Additionally, organic mulching was crucial in lowering the rate of evaporation, which increased the amount of water available to roots and decreased salt content. These observations are following the findings of Ahmad et al. [

35] and Abdelraouf et al. [

2], who indicated that a combination of two economic techniques (mulching and PRD) could be a better way to combat drought stress and increase the yield.

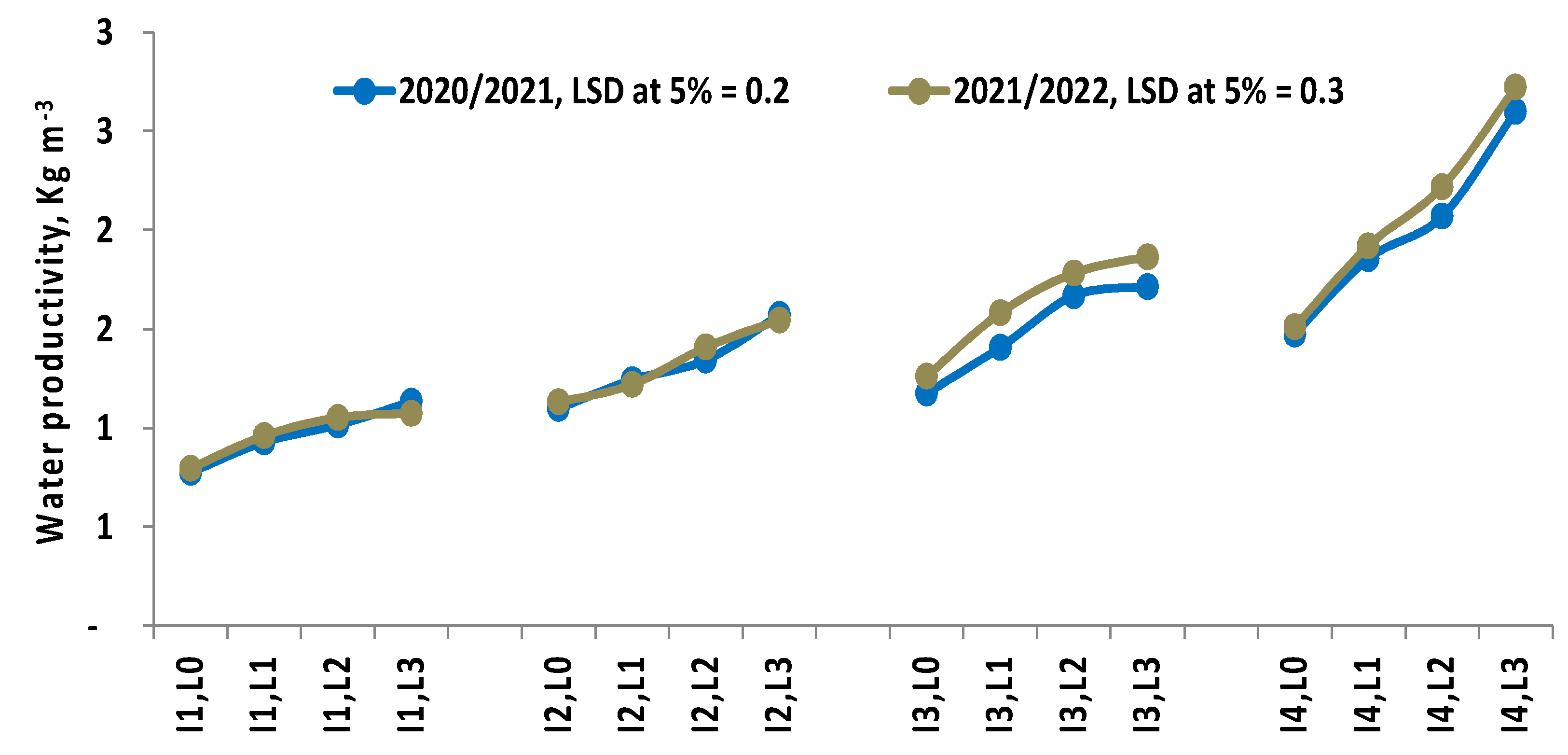

Water productivity

Both factors [irrigation strategies and organic mulching] had a statistically significant effect on water productivity (WP) for the two seasons, as indicated in

Table 2. The first factor (irrigation strategies) positively and significantly affected WP. The highest WP values were under PRD followed by I3 and then I2, while the lowest values were under I1 for the two seasons. The highest values of WP were 2 and 2.093 kg m

-3 occurred by using I4 (PRD) for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively, and PRD and other treatments differ significantly.

The second factor (organic mulch) also significantly affected WP. More WP was recorded in OM, while the lowest values of WP were under L0 for the two seasons. The highest values of WP were 1.754 and 1.801 kg m

-3 occurred by using L3 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively, and there are significant difference between using L3 and other treatments, while the lowest values of water productivity were 1.131 and 1.175 kg m

-3 occurred under L0 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. Fewer evaporation losses and more water conservation in the L3 treatment as compared to other treatments led to a higher value of WP. Due to its influence on soil conditioning, L3 may help improve the soil's ability to retain water and raise the WP. The effect of L3 on increasing the quantity of fruits and, as a result, the yield and WP, is probably connected to the maximum WP. Abdelraouf et al. (2021) proposed the same conclusions. In one of these investigations, Shahabian et al. [

14] in orange trees was in agreement with our finding. According to

Figure 11 and

Table 2, the interaction between the two parameters also had a statistically significant impact on WP for the two seasons.. The highest values of WP were 5.6 and 5.4 kg m-3 occurred using (I4) PRD+L3 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively, and there are significant difference between using these conditions and other treatments, while the lowest values of WP were 2.8 and 2.7 kg m-3 occurred under I1+L0 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. It has been noted that using L3 in conjunction with PRD irrigation improved WP without having much of an effect on crop production. Abdelraouf et al. also noted comparable results [

2,

4].

Quality of mango fruit

Among the irrigation strategies treatments, the highest total soluble solids (T.S.S.), total Acidity, and vitamin C content of mango fruits values were under I4 (PRD), followed by I2 and then I1, while the lowest values were under I3 for the two seasons. The highest values of total soluble solids (T.S.S.), total Acidity, and vitamin C content of mango fruits occurred by using I4 (PRD) and there are no-significant deference between using I4 (PRD), I2 and I1, but there are significant difference between using I3 and other treatments. More total soluble solids (T.S.S.), total acidity, and vitamin C content of mango fruits were recorded by increasing the number of organic mulching layers and there are significant difference between using OM and other treatments, while the minimum values were recorded in L0 for 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, respectively. Improving the mango quality occurred in OM treatment under due to more moisture retention in soil, improved growth, more photosynthetic rate, and ultimately the higher values attributes about other treatments. Similar findings were noted by Raza et al. [

10] who found that mulching increased the stomatal conductance in plants due to higher availability of soil moisture and maintenance of leaf turgor, which keeps the stomata open. All of the above helped increase the absorption of water and nutrients and decrease the water and nutritional stress while increasing the layers of organic mulches.

Table 3.

Effect of deficit irrigation strategies and soil organic mulch on some quality traits of mango

Table 3.

Effect of deficit irrigation strategies and soil organic mulch on some quality traits of mango

| Deficit irrigation strategies |

Soil organic mulch |

T.S.S., (%) |

Total Acidity, (%) |

vitamin C,(mg/100 ml juice) |

| 2020/2021 |

2021/2022 |

2020/2021 |

2021/2022 |

2020/2021 |

2021/2022 |

| I1 |

|

10.0 |

10.8 |

0.84 |

0.86 |

34.7 |

37.0 |

| I2 |

|

10.4 |

11.0 |

0.86 |

0.89 |

36.2 |

38.6 |

| I3 |

|

8.2 |

8.73 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

33.5 |

36.4 |

| I4 |

|

10.7 |

11.3 |

0.84 |

0.91 |

35.3 |

38.0 |

| |

L0 |

8.5 |

9.3 |

0.74 |

0.79 |

28.6 |

31.3 |

| L1 |

9.2 |

9.7 |

0.81 |

0.84 |

31.3 |

33.9 |

| L2 |

9.9 |

10.6 |

0.88 |

0.90 |

36.8 |

39.0 |

| L3 |

11.7 |

12.3 |

0.97 |

1.02 |

43.0 |

46.0 |

| I1 |

L0 |

8.4 |

10.2 |

0.70 |

0.76 |

26.6 |

29.0 |

| L1 |

9.6 |

10.1 |

0.77 |

0.83 |

28.8 |

31.4 |

| L2 |

9.9 |

10.8 |

0.85 |

0.85 |

38.0 |

40.1 |

| L3 |

11.9 |

12.1 |

1.02 |

1.03 |

45.2 |

47.5 |

| I2 |

L0 |

9.2 |

9.6 |

0.81 |

0.84 |

31.7 |

33.8 |

| L1 |

9.7 |

10.4 |

0.83 |

0.85 |

34.2 |

36.4 |

| L2 |

10.8 |

11.3 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

36.5 |

38.9 |

| L3 |

11.8 |

12.7 |

0.97 |

1.01 |

42.7 |

45.4 |

| I3 |

L0 |

6.9 |

7.4 |

0.77 |

0.79 |

29.4 |

32.4 |

| L1 |

7.6 |

8.0 |

0.81 |

0.83 |

32.4 |

35.2 |

| L2 |

8.8 |

9.3 |

0.90 |

0.93 |

34.1 |

36.2 |

| L3 |

9.7 |

10.4 |

0.93 |

0.99 |

38.1 |

41.7 |

| I4 |

L0 |

9.6 |

10.1 |

0.68 |

0.78 |

26.9 |

29.8 |

| L1 |

9.9 |

10.4 |

0.83 |

0.88 |

29.8 |

32.4 |

| L2 |

9.9 |

11.1 |

0.90 |

0.93 |

39.0 |

40.8 |

| L3 |

13.1 |

14.1 |

0.98 |

1.06 |

45.7 |

49.3 |

Saving energy

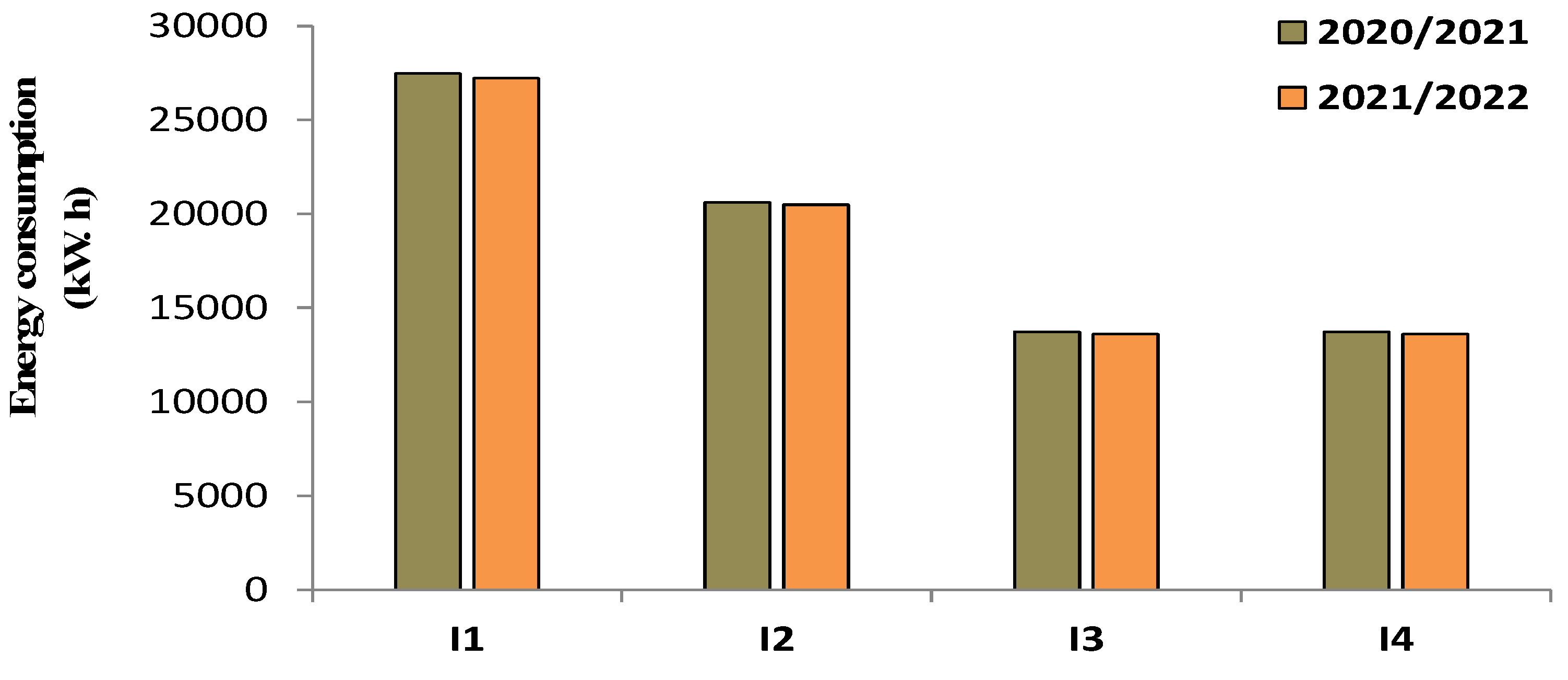

Figure 12 and

Table 4 show the amount of energy savings consumed with the different strategies for scheduling under-irrigation, as it was confirmed that the least energy consumption was achieved with the root drying technique, with which the highest values of crop productivity were achieved, especially when organically covered with three layers of organic coverings of the soil. 50% energy savings have been saved with root drying technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F.; methodology, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F, A.R, M.F.; software, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F.; validation, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F; formal analysis, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F.; investigation, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F writing—original draft preparation, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F writing—review and editing, A.A, A.A.A, M.H,B.B, W.F, H.F, A.H, A.R, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Distribution of main and sub-main factors according to experimental design.

Figure 1.

Distribution of main and sub-main factors according to experimental design.

Figure 2.

Contouring map for different moisture levels with depths for all treatments under study.

Figure 2.

Contouring map for different moisture levels with depths for all treatments under study.

Figure 4.

Soil moisture distribution under 100% Full irrigation and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 4.

Soil moisture distribution under 100% Full irrigation and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 5.

Soil moisture distribution under 75% Full irrigation and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 5.

Soil moisture distribution under 75% Full irrigation and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 6.

Soil moisture distribution under 50% Full irrigation and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 6.

Soil moisture distribution under 50% Full irrigation and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 7.

Soil moisture distribution under partial root-zone drying “PRD” (50% Full irrigation) and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 7.

Soil moisture distribution under partial root-zone drying “PRD” (50% Full irrigation) and soil organic mulch in the root-zone [L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch) and (green line represent field capacity)].

Figure 8.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on salt accumulation in root-zone [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 8.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on salt accumulation in root-zone [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 9.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the soil organic matter content [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50 % FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 9.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the soil organic matter content [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50 % FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 10.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the yield of mango [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 10.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the yield of mango [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 11.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the water productivity of mango [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 11.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the water productivity of mango [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI) and L0 (Zero layer organic soil mulch ”control”), L1 (Single layer organic soil mulch), L2 (Two layers of organic soil mulch), and L3 (Three layers of organic soil mulch), PWP (permanent wilt point) and FC (field capacity)].

Figure 12.

Energy consumed with scheduling deficit of irrigation. [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI)]

Figure 12.

Energy consumed with scheduling deficit of irrigation. [I1 (100% of full irrigation “FI”), I2 (75% FI), I3 (50%FI), and I4 (PRD:50% FI)]

Table 1.

The soil's physical and chemical characteristics in the testing area.

Table 1.

The soil's physical and chemical characteristics in the testing area.

| Soil properties |

Soil depths (cm) |

| 0–40 |

40-80 |

80-120 |

| Soil texture |

Sandy |

Sandy |

Sandy |

| Course sand (%) |

48.00 |

55.22 |

44.72 |

| Fine sand (%) |

49.43 |

41.60 |

51.54 |

| Silt + clay (%) |

2.57 |

3.18 |

3.74 |

| Bulk density (g cm-3) |

1.68 |

1.69 |

1.71 |

| Organic matter (%) |

0.45 |

0.32 |

0.23 |

| EC (dS m-1) |

0.67 |

0.55 |

0.51 |

| pH (1:2.5) |

8.6 |

8.3 |

8.4 |

| Total CaCO3 (%) |

7.25 |

2.43 |

4.66 |

Table 2.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the yield and water productivity of mango.

Table 2.

The performance of partial root-zone drying technique and soil organic mulch on the yield and water productivity of mango.

| Deficit irrigation strategies |

Soil organic mulch |

Yield of fruits, (ton ha-1) |

Water productivity, (kgmango m-3water) |

| 2020/2021 |

2021/2022 |

2020/2021 |

2021/2022 |

| I1 |

|

9.7 |

9.7 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| I2 |

|

9.9 |

10.0 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

| I3 |

|

7.5 |

8.1 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

| I4 |

|

10.1 |

10.5 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

| LSD at 5% |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| |

L0 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

| |

L1 |

8.8 |

9.1 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

| |

L2 |

9.8 |

10.3 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

| |

L3 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

| LSD at 5% |

0.7 |

1.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

| I1 |

L0 |

7.8 |

8.0 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

| L1 |

9.4 |

9.6 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

| L2 |

10.2 |

10.5 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

| L3 |

11.4 |

10.7 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

| I2 |

L0 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

| L1 |

9.4 |

9.1 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

| L2 |

10.2 |

10.6 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

| L3 |

11.9 |

11.6 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

| I3 |

L0 |

5.9 |

6.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

| L1 |

7.1 |

7.9 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

| L2 |

8.4 |

8.9 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

| L3 |

8.6 |

9.3 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

| I4 |

L0 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| L1 |

9.4 |

9.6 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

| L2 |

10.4 |

11.1 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

| L3 |

13.1 |

13.6 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

| LSD at 5% |

1.3 |

2.4 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

Table 4.

Energy consumed with scheduling deficit of irrigation.

Table 4.

Energy consumed with scheduling deficit of irrigation.

| |

BP: Brake power (kW) |

Operating hours of irrigation, (hr) |

Energy consumption(kW. h) |

%, Saving energy |

| |

Q, m3/sec |

TDH, (m) |

YW, kN/m3

|

Ei, % |

EP, % |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

| I1 |

45 |

200 |

9.81 |

90 |

80 |

224 |

222 |

27468 |

27223 |

0 |

0 |

| I2 |

168 |

167 |

20601 |

20478 |

25 |

24.8 |

| I3 |

112 |

111 |

13734 |

13611 |

50 |

50 |

| I4 |

112 |

111 |

13734 |

13611 |

50 |

50 |